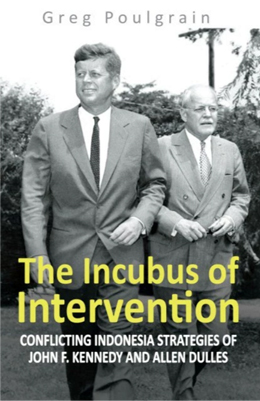

Kennedy’s Planned Trip to Jakarta

In the Foreword to my book on Malaysian Confrontation, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, one of Indonesia’s leading writers, commented on President Kennedy’s anticipated visit to Jakarta in early 1964:

Kennedy’s plans to meet Sukarno in Indonesia never came to pass: that we all know, for he was murdered….

Pramoedya drew attention to the planned visit without elaborating, apart from saying that Kennedy, and Indonesia’s President Sukarno, had to disappear from the stage of history. Half a century has elapsed since these two leaders ‘disappeared’ and with them the political positivity of the now forgotten plan to visit Jakarta. Instead, in the mid-1960s, a proliferation of violence and military mentality suffused the nation. Indonesia still bears the scars. This outcome was in stark contrast to the ‘Indonesia strategy’ Kennedy was planning in 1963. Working in conjunction with Sukarno whose perennial aim was to unify his nation, JFK’s intended visit was lost in the turgid history of that time.

Kennedy’s proposed visit to Jakarta ‘in April or May of 1964’ according to the long serving US ambassador in Indonesia, Howard Jones, was a strategy to end Malaysian Confrontation. This period of hostility between Indonesia and Malaysia, involving armed skirmishes and provocative political posturing, fell short of war. It started in early 1963 as Indonesian ‘protest’ against the British format of decolonisation which was simply lumping together its disparate colonial possessions in Southeast Asia to ensure the numbers of Chinese overall were in the minority. The reaction in Washington to Confrontation resulted in US aid to Indonesia being reduced to a trickle. Reopening these aid channels was part of Kennedy’s rationale in making the trip because Indonesia was a vital component of his larger strategy in Southeast Asia. Planning the visit to Jakarta involved several months of negotiation before Kennedy and Sukarno reached an agreement; then on November 20th the visit was formally announced. Because of the tragedy in Dallas a few days later, the visit did not occur. ‘The assassin’s bullet put an end to our plans and disposed of the immediate prospects for settlement of the Malaysia dispute,’ wrote Jones.1 Confrontation continued up to 1965/6 when President Sukarno was ousted by General Suharto.

As shown in my book The Genesis of Konfrontasi, from archival evidence and interviews, Sukarno was not the instigator of Malaysian Confrontation. Instead, the principal Indonesian player was the Foreign Minister, Subandrio, who ran the largest intelligence service in Indonesia and fully expected to be the next president. As well, Confrontation did not start without various covert actions by persons linked to both British intelligence (MI6) and American intelligence (CIA), centered in Singapore and operating outside the aegis of government.

President Sukarno’s role in Confrontation underwent a change after Kennedy’s assassination. Initially, when Indonesia became embroiled in the conflict not of his doing, Sukarno’s public statements were designed to steer a course through dangerous political currents beyond his control, whereas after November 1963 he was attempting to regain leadership of this anti-British, anti-colonial campaign. This change in Sukarno was reflected in the expression ‘Ganjang Malaysia’, popularised in Western media as ‘Crush Malaysia’. Earlier, Sukarno had disagreed with this interpretation, and actually performed for the media to demonstrate his meaning. ‘Ganjang’, he explained, was like nibbling food in your mouth to check it for taste – as would a politician, checking for any disagreeable taste of colonialism – then spitting it out! Territorial acquisition was not on the menu in Malaysian Confrontation. Nevertheless critics of Indonesia2 readily depicted Confrontation as expansionism because it came hard on the heels of Sukarno’s sovereignty dispute over Netherlands New Guinea, a dispute in which President Kennedy’s role had proved crucial. Sukarno commanded great respect as the founding father of Indonesian independence, but he himself was unable to halt Confrontation because it was driven by domestic political rivalry.

Having ousted the Dutch from New Guinea, Indonesia in 1963 was still seething with anti- colonial venom. There were three rival streams of Indonesian opposition to Malaysia – one linked with Subandrio, another with the Indonesian communist party (PKI) and another with the Indonesian army. These three disparate groups were involved in the initial border skirmishes with Sarawak in east ‘Malaysia’ being defended by British troops, in the throes of decolonisation. The intermittent conflict drew criticism from Washington through the US ambassador in Jakarta who explained that the US government agreed that ‘Malaysia’ was the best format for decolonisation. Then, in September 1963, after the burning of the British Embassy in Jakarta, bilateral relations with USA were strained to the point where aid for Indonesia was reduced to a minimum. Kennedy’s efforts to ensure his aid program would not falter now attracted criticism from British officials who ‘told the White House with increasing frequency that UK and US interests regarding Indonesia were beginning fundamentally to diverge.’3 Republican Congressman William S. Broomfield claimed that Indonesia was misusing US assistance. Support to cut US aid came from a clique of other Congressmen including Mathias, Gross and Findley.

Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon then endorsed the ‘Broomfield amendment’, demanding that Indonesia be dropped from the list of recipients of US aid. ’I say we should wipe it off the aid program’, he declared.4

Kennedy’s planned visit to Jakarta was a radical move to re-open all funding as this was a vital part of the ‘follow-up strategy’ he had set in place after intervening in 1962 in the anti-colonial dispute with the Dutch. In Indonesia, Kennedy’s intervention had stirred popular euphoria in his favour, and this continued into 1963, such was the young American president’s charisma. The Bay of Pigs, the Congo, Berlin, Laos, Vietnam, the Cuban missile crisis – the Cold War crises confronting him were making global headlines which for Indonesian readers kept ‘JFK news’ current, well past the highpoint of the New York Agreement in August 1962. In terms of implementing his ‘follow-up strategy’ to the sovereignty crisis, the ideal time to exploit pro-JFK sentiment was in 1963, yet the proposed date for the visit to Jakarta in early 1964 would still benefit from the kudos surrounding President John F. Kennedy. His ‘footprint of fame’ had been greatly enhanced by intervening in the New Guinea dispute: unresolved since independence in 1949, it had created its own anti-colonial niche in Indonesia’s collective psyche.

Malaysian Confrontation in 1963 had caused the delay and then the Bloomfield Amendment, cutting the funding for his Indonesia strategy, left JFK no alternative. Only then did he resolve to make the Jakarta visit and employ his charisma as the last political weapon at his disposal. Success for Kennedy’s visit to Jakarta depended upon the response of the Indonesian populace; and this (in late 1963) was still very positive. So it seemed a forgone conclusion that he would have achieved his goal because of the degree of veneration for JFK in Indonesia, combined with the eloquence of Indonesia’s President Sukarno for whom there was still widespread adulation. The politics of personality was the only weapon at the disposal of both Kennedy and Sukarno to bring Confrontation to a stop, and it was their intention to employ it jointly, and to the full, once the US president was in Jakarta. During his three years in office, Kennedy’s image and reputation had acquired a very positive aura throughout Asia and Africa far surpassing his predecessor, President Eisenhower. The 43-year old president was seen as pro-Indonesian – his new political stance and willingness to act decisively, capped off by his intervention in the sovereignty dispute, was in stark contrast to the blatant political interference of his 70-year old predecessor.

Indonesians and especially Sukarno, whose oratorical skill was well-honed over four decades, welcomed the new style, the new era, as heralded in the inaugural address.

…Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans – born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace….

JFK’s political opponents ensconced in Washington throughout the 1950s were unaccustomed to a president asserting such personal control. It was his forte, especially in foreign policy. ‘Kennedy’s instinctive style which was one of personal and intimate command’5 took on unprecedented importance and became a threat to the political strategy of his opponent because it meant he was highly likely to implement the aims of his Jakarta trip.

Kennedy was aiming for a seismic shift of Cold War alignment in Southeast Asia – bringing Indonesia ‘on side’. As Bradley Simpson stated (in 2008):

One would never know from reading the voluminous recent literature on the Kennedy and Johnson administrations and Southeast Asia, for example, that until the mid-1960s most officials [in the US] still considered Indonesia of far greater importance than Vietnam and Laos.6

Kennedy wanted to ensure that Indonesia was secure before implementing any policy decision regarding the US presence in Vietnam. The two interrelated parts of his action plan after the New Guinea sovereignty dispute involved utilising the predominantly pro-US Indonesian army, and large-scale US aid for development projects in Indonesia. Both Kennedy and his opponents in Washington pursued a paradigm of modernisation which had emerged in the late 1950s using the military as the most cohesively organised group in undeveloped countries. Simpson has outlined how the ‘US government’s embrace of military modernization’ in the early 1960s followed on from the March 1959 Draper Committee Report which called for using the armed forces of underdeveloped countries ‘as a major transmission belt of socio-economic reform and development’.

Admiral Arleigh Burke and CIA director Allen Dulles argued at a June 18 NSC meeting [1959] that the United States ought to expand military training programs in Asia to include a wide range of civilian responsibilities and to encourage Military Assistance Advisory Groups (MAAGs) to ‘develop useful and appropriate relationships with the rising military leaders and factions in the underdeveloped countries to which they were assigned’. A few months later the semi-governmental RAND Corporation held a conference at which Lucian Pye, Guy Pauker, Edward Shils, and other scholars expanded on these ideas.7

Admiral Arleigh Burke, Dulles and Pauker were ‘promoting the Indonesian armed forces as a modernizing force’ (a strategy linked to Dulles’ role in the 1958 Outer Islands Rebellion – see Chapter 4) and, continues Simpson:

the army simultaneously pursued a counterinsurgency strategy against internal opponents while greatly expanding its political and economic power following the 1957 declaration of martial law and the takeover of Dutch enterprises.

By the time Kennedy came to office, much of Southeast Asia-related US policy was infused with military modernisation theory. Civic action programs figured highly in Kennedy’s strategy in Indonesia, utilising the army but also the police, designed to counterbalance the attraction the PKI had for impoverished farmers – like moths to a light in the hope of salvation. The infrastructure and poverty reduction programs were tied to US funding and framed around the assessment made by Tufts University Professor Donald Humphrey. He recommended that US aid to Indonesia starting in 1963 should be in the order of US$325–390 million. Europe and Japan were to have contributed almost half of this, but Kennedy’s aid program soon encountered difficulties in the Congress.

While still acutely wary of policy interference as occurred with the Bay of Pigs like an inaugural ‘wake-up call’, Kennedy had no way of ascertaining how his Indonesia strategy actually threatened the Indonesia strategy of his opponents. Nevertheless, the fact that JFK insisted on denying the CIA any part in his own negotiations with Sukarno is an indication of the serious distrust he held by 1963. Earlier in 1961, when Dulles was at the height of his power and JFK had been in office only a few months, he had requested a Briefing Paper from the CIA, prior to President Sukarno’s visit in April 1961. The advice given President Kennedy was that ‘we should not now entertain any major increases in the scale of economic or military aid to Indonesia’. Mindful of Allen Dulles and Guy Pauker as the mouthpiece of military modernisation, Kennedy must have interpreted such advice as hypocritical. Similarly, the CIA advice on whether or not Kennedy should support Sukarno’s quest to oust the Dutch from New Guinea lacked not so much insight as vision; it offered only a bleak prospect, saying that whichever way the President moved it would not alter the inexorable rise to power of the PKI.

It would be gratifying to be able to propose an alternative course of action by the United States which would stand a good chance of turning the course of events in Indonesia in a constructive direction. Unfortunately, this is a situation in which the influence that the United States can exert, at least in the short run, is extremely limited, if (as must be assumed) crude and violent intervention is excluded.8

Kennedy chose to support Sukarno’s claim to the Dutch territory and follow through with precisely the opposite to what the CIA had advised – an economic aid program to counter the PKI by addressing poverty through civic aid and development projects. When the funding restrictions imposed by Congress brought JFK’s follow-up plan to a standstill and he resolved to make an historic visit to Jakarta to restart the US aid project, the threat to Dulles’ strategy left no option. In the same way that Dulles had offered Kennedy no option in the 1961 Briefing Paper, in 1963 Kennedy’s decision to visit Jakarta left no option for Dulles (whom JFK had already ushered to the political sidelines). We can surmise how the exit of Dulles in 1961 may have seemed a positive move for Kennedy and one that should have helped him in 1963 implement the Indonesia policy he wanted. While Dulles’ removal from office did little to diminish his influence, it could only have exacerbated the threat created by Kennedy’s plan to visit Jakarta. Dulles simply had no answer to counter Kennedy’s dramatic personal initiative to visit Jakarta: or to re-contextualise the same comment from the 1961 Briefing Paper given Kennedy, Dulles had no answer in 1963 ‘if (as must be assumed) crude and violent intervention is excluded’.

In two crucial aspects, Kennedy’s plan clashed with the ongoing strategy of ‘regime change’ which DCI Dulles had set in motion six years earlier. Firstly, JFK intended to utilise the Indonesian army as ‘servants of the state’ of Indonesia, not for the army to assume power. And secondly, Kennedy’s intention was to maintain the presidency of Sukarno. Unbeknown to Kennedy, his plan to use the army was in effect commandeering the same asset intended by Dulles to implement regime change. Not only was JFK usurping the benefits of the transformation occurring as a result of US training of Indonesian army officers – a process which David Ransome labelled with the pithy description, a ‘creeping coup d’etat’9 – but ensuring Sukarno remained president would prevent the full military option. Kennedy would not simply have overruled his opponent but, in addition, keeping Sukarno as president would have prevented gaining untrammelled access to natural resources, a project which had been many years in the planning. We may surmise Kennedy was partially aware that his overall plan was making use of a military option still in its preparatory stage, simply from the large number of Indonesian army officers being trained in the US. Their common ground was ‘the ideological focus of US officials on the military as a modernizing force’, but where Kennedy was starkly at odds with his Washington opponents was his determination to retain Sukarno as President of Indonesia.

The visit to Jakarta was premised on an understanding between Kennedy and Sukarno to bring Malaysian Confrontation to an end, while JFK was in Jakarta. Howard Jones, US Ambassador in Jakarta from 1958, was well acquainted with Sukarno and fully aware that the key to achieving this important political change was Kennedy’s charisma, combined with the adulation and respect he commanded. Together, Kennedy and Sukarno could bring about a cessation of Malaysian Confrontation but, as Jones observes in his book Indonesia: the Possible Dream, ‘Sukarno could not initiate a settlement of the dispute himself ’.10

JFK’s Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, in personal correspondence with me (January 8, 1992)11 wrote: ‘President Kennedy made it clear that confrontation between Indonesia and Malaysia should be stopped….’ Only after several months of negotiation with the Indonesian President did Kennedy agree to the proposed visit, after three requests by Sukarno. The one precondition set by Kennedy was his insistence on achieving a ‘successful outcome’. Rusk confirmed in writing the arrangement with Sukarno: ‘President Kennedy made it clear that confrontation between Indonesia and Malaysia should be stopped, not merely for the duration of Kennedy’s visit but on a permanent basis’. However, it was not confrontation that was stopped but rather, the visit by Kennedy himself.

For Sukarno, Kennedy’s precondition meant declaring a permanent cessation of hostilities during the actual visit of the American president; while for JFK himself, a ‘successful visit’ meant ending the hostilities which were jeopardising the Indonesia strategy he had initiated in 1962 and which Malaysian Confrontation in 1963 was threatening to turn into just another ‘Cold War fatality’.

As part of a wider Southeast Asian tour, the visit was described by JFK as one that would provide a much needed boost to his chances for re- election. This tongue-in-cheek explanation understated the real political significance which the visit held for Kennedy himself. Now with a half- century of hindsight, the adverse repercussions of not making that trip to Jakarta are more clearly delineated in terms of the tragedy that befell Indonesia in 1965. In Cold War terms, Kennedy’s Indonesia strategy held every chance of success – indeed, the very likelihood of success compelled the decision to prevent the trip. For Dulles’ Indonesia strategy, Kennedy’s intention to support and prolong the Sukarno presidency was political anathema.

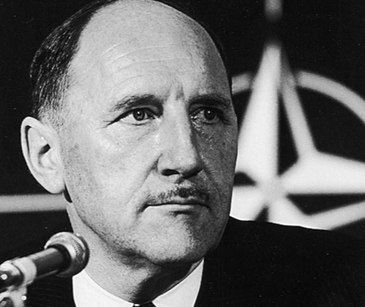

Why Kennedy Retained Allen Dulles

Between election and inauguration, John Kennedy had 72 days to survey the tumult of domestic and international issues soon to be encountered as the 35th President. Some of these, among other issues, included political unrest in the Congo, Laos, Vietnam and Berlin. Two such issues actually ballooned into potential crises during his time as President-elect. One of these involved Cuba, the other Indonesia and both involved Allen Dulles as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI). President Kennedy for various reasons had retained Dulles from the Eisenhower administration, a fateful inheritance from the ailing incumbent.

When Kennedy began organising his administration as President- elect, the first press announcement he made was that Allen Dulles would remain as DCI. In finding ‘the best person for the job’ to meet the multifarious demands of staffing the new administration, staff which finally included fifteen Rhodes scholars, Kennedy often adopted a bipartisan approach. Surely, choosing Dulles indicated that Kennedy did not regard him as being among the ‘opponents in Washington’? Yet within the first three months of the Kennedy presidency, Dulles had inflicted so much political damage this question does not bear answering, but simply prompts another: why, then, did Kennedy retain Dulles as DCI? Dulles was an icon of US intelligence. Since 1916 – before John Fitzgerald Kennedy was even born – Dulles had served in that specialised field under every US president since Woodrow Wilson.

Another reason for retaining Dulles was linked to the narrow victory over Republican presidential contender, Richard Nixon. The winning mar- gin of votes – only 120,000 out of a total of 69 million12 – was attributed to Kennedy’s success in the televised debates. Theodore Sorensen, Kennedy’s speechwriter and special counsel throughout most of his political career, from Congressman to Senator and then President, described the debates as ‘the primary factor in Kennedy’s ultimate victory’.13 The televised debates in October 1960 were the first time such an event was held although nowadays televised debates between presidential candidates are the norm. For Kennedy and Nixon, there were four debates, four unprecedented opportunities to reach millions of Americans, and the first (which was on domestic policy) had an audience of 70 million. The second and third debates were questions and answers, while the fourth debate was on foreign policy, and this was where Allen Dulles played his hand. Castro and Cuba ‘only 90 miles from our shore’ had been much in the news during the year of presidential campaigning and claimed an important part of the fourth debate. Nixon already knew that the CIA was planning an invasion of Cuba, but of course could not mention this during the debate; but Dulles had provided Kennedy a strategically timed briefing on Cuba shortly before the debate. Dulles did not divulge information about the invasion – that would come at Palm Beach when he was President-elect and during his first week of office – but at this stage Dulles gave Kennedy the edge with other intelligence which proved crucial during the debate. And crucial too, it seems, when the time came for Kennedy to decide whether or not to retain Dulles as DCI. Dulles’ briefing must have seemed like a godsend when Kennedy was analysing the votes that won him the presidency.

There was still another reason for Dulles being included in the President-elect’s first announcement. After winning the Democratic nomination, Kennedy had requested two persons to prepare separate reports on the anticipated transition from Republican to Democratic administration. These two persons were Columbia professor Richard Neustadt and Clark Clifford whom Sorensen described as ‘a Washington attorney’. His former experience, however, included special counsel to President Truman during the 1948 presidential campaign against Thomas E. Dewey. Special counsel for Dewey was Allen Dulles who was also ‘the confidential link on foreign policy matters between the Truman administration and the Dewey campaign’.14 So in 1960, bipartisanship in relation to Allen Dulles was revisiting Clifford’s earlier contact with Dulles. In both reports, Kennedy was advised to retain Dulles as DCI (and J. Edgar Hoover as director of the FBI).15 Ironically, in May 1961 after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, Kennedy invited Clifford into the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board to ensure the accuracy and unbiased nature of the intelligence being supplied to the President. Neustadt had recommended the directors of five ‘sensitive positions’ remain unchanged, but of these only Dulles and Hoover were retained. Sorensen quipped that, of the five, ‘Kennedy kept only the first two, whom the dinner guests the previous evening had reportedly suggested be the first to be ousted’.16

The intelligence on Cuba, which Dulles provided to Kennedy before the crucial debate with Nixon, gave the Democratic candidate a clear advantage over his Republican rival. More than just highlighting Dulles’ familiarity with Cuba, this showed Dulles was investing in the possibility of Kennedy winning the presidency. Perhaps even more than this, it showed Dulles (who through family and social connections knew ‘Jack’ Kennedy, his wife and the extended family) already had his measure of the man. Dulles knew that Kennedy would not leave this debt unpaid. As it turned out, the narrower the margin of winning votes, the greater seemed the debt, and if Dulles’ briefing before the historic debates could be described as a pre-election psychological strategy, it worked perfectly. Kennedy’s perceived familiarity with the issue of Cuba may have proved crucial in winning the debate, but Dulles’ duplicity soon became apparent. In Kennedy’s first week in office, it was his unfamiliarity with the issue of Cuba, or rather, the CIA’s half-baked invasion of Cuba, that proved to be an international embarrassment for the new president. Sorensen commented: ‘The Bay of Pigs had been – and would be – the worst defeat of his career’.17

Fidel Castro’s Cuba, not Indonesian Papua, became the bête noir of US foreign policy after the CIA invasion force foundered in the Bay of Pigs on April 18, 1961. Castro’s declaration of a socialist state and the importing of Soviet missiles led to a nuclear standoff. While Kennedy negotiated with Khrushchev, the world, collectively, held its breath. Cuba, however, had not become the touchstone of Cold War tension without the initial input from Allen Dulles.

Apart from the generational difference, JFK and Dulles both were in office alongside their siblings, JFK’s younger brother Robert as Attorney General and DCI Dulles’ elder brother John Foster Dulles was Eisenhower’s Secretary of State. The depth of experience in the two Dulles brothers was unprecedented, starting from the Versailles Treaty with John Foster drawing up the reparations agreement and Allen in the intelligence section. Between them was always a fierce sense of rivalry to achieve results in international affairs, continuing the sibling rivalry that had persisted throughout their childhood. John Foster was firstborn and favourite whereas Allen, born seven years later with a clubfoot, was always trying to prove he was as good as Foster, if not better. It was Allen, not Foster, who had always wanted to be Secretary of State. There had already been two family members in that office – an uncle in the Wilson presidency and their maternal grandfather, in the Harrison presidency – yet it was John Foster not Allen who achieved that goal when Eisenhower became president in 1953.

If there was any similar in-family rivalry in the Kennedy clan, it disappeared after the deaths of the eldest son during the war and the eldest daughter soon after the war. In the case of John and Robert Kennedy when JFK was president, the two brothers were intensely reliant on each other’s abilities and tended to act as one unit, as in Robert’s negotiations with President Sukarno and Dutch Foreign Minister Luns in the New Guinea sovereignty dispute. In Kennedy’s various elections starting in 1952, culminating in the presidency, Robert was his trusted campaign manager. In the first Eisenhower administration, the link between John Foster as Secretary of State and Allen as Director of Central Intelligence, on both official and family levels, was seen by the media as beneficial to the national interest. The Dulles brothers were perceived as having created their own legend even before serving together under Eisenhower. While acting together, however, they were not one unit as the Kennedys were in the 1960s. The media reaction to this was often expressed in religious terms, JFK being the first Catholic to reach the office of president. John Foster followed his father in the Presbyterian faith, attending church every Sunday, whereas Allen had adulterous affairs for most of his working life without jeopardising his lifelong role in intelligence.

Similar indiscretion by John Kennedy may have led to the political pressure referred to by Frederick Kempe18 for retaining Allen Dulles and J. Edgar Hoover. Allen revelled in intelligence whereas John Foster ‘often chose to adopt the State Department mentality of knowing as little as possible about sordid operational details of intelligence’. Grose expounds this point further, saying that Allen always claimed his duty was intelligence, and policymaking was John Foster’s responsibility but ‘Allen was ever imaginative in devising intelligence operations that by their very nature determined the shape of national policy’.19

When John Foster Dulles passed away in April 1959, after two years of failing health because of colon cancer, Allen’s covert intelligence operations entered an even more radical stage. Allen began taking bigger risks. John Foster had not wanted Allen to succeed him as Secretary of State and bluntly told him so, closing the door on that lifelong ambition. He recommended that his successor be Christian Herter who was reliant on crutches because of osteoarthritis. Christian Herter and Allen Dulles were not close friends, despite being acquainted since the First World War. With a new Secretary of State for the remaining twenty-one months of the Eisenhower administration, the change in dynamic in the upper echelon of power influenced Allen’s mode of operations. As well, John Foster’s death no doubt served as a reminder to Allen of his own mortality. He was, after all, almost 67 years old when retained by Kennedy as Director of Central Intelligence. He was reaching the end of his career and the culmination of a major project centred on the Indonesian archipelago which had first caught his attention years earlier. The CIA- assisted ‘covert operation’ in Indonesia, the Outer Islands rebellion (otherwise known as the PRRI-Permesta rebellion which is examined in Chapter 4) was but one part of this major project. Allen Dulles has been openly linked with this rebellion which started in February 1958. It ended almost immediately, although for the next few years he maintained a supply of weapons for the rebels because continuing conflict ensured the officially declared ‘state of emergency’ also continued. This effectively delayed the holding of elections in Java and precluded the possibility of the Indonesian communist party attaining any increased representation or political power through the ballot box.

As a result of his vast experience in diplomacy, oil, intelligence and state affairs, Allen Dulles had at his disposal a network of contacts which he used in his Indonesia project. Ultimately, he was aiming for regime change, the essential ingredient of which was a central army command. Aware of the immense potential of natural resources in Netherlands New Guinea since pre-war days, Dulles wanted the Dutch territory to become part of Indonesia. While this was achieved on Sukarno’s watch, it was done only because the central army command was already amassing in the corridors of power awaiting regime change.

When Kennedy officially ended Dulles’ role as Director of Central Intelligence on November 29, 1961, Allen’s network of contacts was like an intelligence tsunami held in abeyance. The president described the departing DCI in prophetic terms:

I know of no other American in the history of this country who has served in seven administrations of seven Presidents – varying from party to party, from point of view to point of view, from problem to problem, and yet at the end of each administration each President of the United States has paid tribute to his service – and also has counted Allen Dulles as their friend. This is an extraordinary record, and I know that all of you who have worked with him understand why this record has been made. I regard Allen Dulles as an almost unique figure in our country.

Yet Dulles still commanded enormous influence. The newly appointed director, John McCone, with legions of staff moved into the new building at Langley. Ironically, in the design and construction of the new head- quarters, Dulles had played a prominent role, but he never occupied the new building. He still kept his former office and, as well, took up another with Sullivan and Cromwell, the legal firm in which he had worked with John Foster in the 1930s, representing Rockefeller oil interests and the myriad of subsidiaries. Allen had not actually married into the Rockefeller family as John Foster had done, but nevertheless his lifelong association with Standard Oil made him an essential member of the extended family. In the years between the First and Second World Wars, there was no legal restriction on someone like Allen Dulles sharing his expertise between private enterprise and the State Department as mentioned by John D. Rockefeller, at 98 years of age, openly expressing his thanks in his pre-Second World War publication, Random Reminiscences of Men and Events:20

We did not ruthlessly go after the trade of our competitors and attempt to ruin it by cutting prices or instituting a spy system…. One of our greatest helpers has been the State Department in Washington…. I think I can speak thus frankly and enthusiastically because the working out of many of these great plans has developed largely since I retired from the business fourteen years ago.

Rockefeller’s reputation as ‘the richest man in history’ was not achieved without the acumen of Dulles gaining entry into oil rich regions, from the ‘Near East’ to the ‘Far East’, when European colonial power was still dominant. The important mining and oil exploration conducted in Netherlands New Guinea shortly before the Second World War (as revealed by Jean Jacques Dozy in Chapter 1) was an important part of the ‘oil-intelligence project’ which focused on Indonesia in its entirety. Ensuring West New Guinea changed hands, from Dutch to Indonesian control, became an integral part of Allen Dulles’ political strategy which then proceeded with the already advanced plan for ‘regime change’ in Indonesia. The problem was: for Dulles’ strategy, JFK’s notion of visiting Jakarta to support Sukarno, ensuring he would remain president, was political anathema.

Pre-war development in the New Guinea territory was meagre – with half a dozen small colonial settlements, scattered around the far-flung coastline. These had begun as a cluster of army encampments at the turn of the century in response to the US gaining control of the nearby Philippines. Within a few years, the giant US company, Standard Oil, which then was inseparable from the name Rockefeller, had initiated a takeover bid for Dutch oil interests in the Indies. The Dutch responded by joining forces with the British in 1907 to form Royal Dutch Shell. This started decades of pressure from Rockefeller oil interests to gain exploration rights in the vast, unmapped Dutch territory of New Guinea. Ultimately, in May 1935, with the formation of the Netherlands New Guinea Petroleum Company21 which had 60% controlling US interest, Standard Oil was successful, but only with the help of their top European- based lawyer, Allen Dulles. NNGPM, as the company was called, was formed with the approval of Sir Henri Deterding, general manager of the Royal Dutch Shell group of companies since 1900. Deterding and Rockefeller, in former days, had been fierce opponents in the global oil business. When Allen joined his brother John Foster Dulles in Sullivan and Cromwell, the top Wall Street legal firm, his first big case in 1928 brought him face to face with Deterding. Despite the silver hair and penetrating black eyes which helped to create a Napoleonic presence, Deterding backed down and Allen Dulles won. Yet by the mid-1930s, when NNGPM was formed, Dulles and Deterding shared a common interest in the new leader of Germany, Adolf Hitler. Dulles had wasted no time in arranging to speak with Hitler personally, soon after he came to power in 1933, and Deterding’s friendship with Hitler led to million dollar donations. However, the key element which swayed Dutch opinion in the formation of NNGPM was the evidence that Japanese units were secretly conducting oil exploration in New Guinea territory. Without American assistance the Dutch could do little to assert colonial control and Dulles used the political tension generated by the Japanese incursion of colonial sovereignty to push through the 60% US controlling interest in NNGPM.

Leading up to the Second World War in the Pacific, the Japanese Navy formulated a grand theory of expansion, not merely as an answer to the problems the Japanese army was facing in its program of expansion in China, but as a grand theory of new development. It was called ‘the march to the South’ or Nanshin-ron. Here lay the wealth of the Netherlands East Indies; here there was oil, and in populous Java a market for the Japanese product. For natural resources, the eyes of the Japanese Navy turned to New Guinea. They envisaged this vast island (more than twice the total area of all the islands of Nippon) becoming the source of raw materials for a new imperial Japan. Nanshin-ron took shape with industrial speed in the upper echelons of Japanese Naval Intelligence which used a vanguard of fishing ships estimated by Dutch Intelligence to number as many as 500. Admiral Suetsugu, Commander of combined Japanese fleets and later Minister of Home Affairs, described these ‘fishermen’ as an integral part of the ‘March South’. Japanese anthropologists were dispatched to collect information on the tribespeople of New Guinea. The concern about Japanese intrusion as expressed by Jean Jacques Dozy (in the interview in Chapter 1) was part of this pre-war expansion utilised by Allen Dulles to gain the 60% US controlling interest in NNGPM.

After the Pacific War, geologists attached to General Douglas Mac- Arthur’s forces remained in the Dutch territory for most of the next decade conducting exploration. Only some of their findings were released, such as nickel on Gag Island, which (as mentioned above) was 10% of world nickel reserves. There was no mention of Dozy’s gold discovery. During the 1950s, neither Dulles nor the Dutch political hierarchy was willing to admit that the real issue at the centre of the sovereignty dispute, which so loudly proclaimed the territory had no natural resources, was how to gain control over the gold, copper and oil that lay waiting to be discovered. During the 1950s, using the Cold War to his advantage, Allen Dulles’ strategy took shape.

At the same time as the Bay of Pigs another crisis was occurring in Indonesia, lesser known but with the same potential for superpower conflict. This dispute between Indonesia and the Netherlands, over sovereignty of the western half of New Guinea, pitted the US-Dutch NATO alliance against Soviet support for Indonesia. Kennedy’s settlement of this crisis and his follow-up strategy to bring Indonesia ‘on side’ in the Cold War came under threat with Malaysian Confrontation – hence the planned visit to Jakarta.

Introducing Indonesia

Before looking at Kennedy’s role in the sovereignty crisis, let me re-introduce Indonesia which after China, India and USA now has the fourth largest population in the world. Indonesia had emerged from the ‘colonial era’ only a decade before Kennedy’s involvement. When he expressed criticism of colonial rule (as he did at the UN General Assembly, September 25, 1961, upon the death of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld) he chose his words carefully to apply not only to the colonised peoples of Africa generally but also to Indonesia specifically.

He spoke of the exploitation and subjugation of the weak by the powerful, of the many by the few, of the governed who have given no consent to be governed, whatever their continent, their class, or their color.22

European dominance in navigation, military technology and trade ensured the peoples of the Indonesian archipelago for centuries remained at the beck and call of colonial powers. As described by George Kahin, one of America’s most prominent Indonesia specialists, it was ‘probably the world’s richest colony … (or) ranked just after India in the wealth it brought to a colonial power’.23

It is our collective unfamiliarity with this vast country which has led to our failure to ascertain how closely intertwined it was with the fate of President Kennedy. He very early recognised the significance of Indonesia not only in the political destiny of Southeast Asia but also in the outcome of the Cold War.

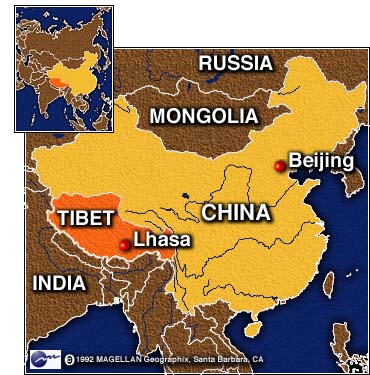

Indonesia is by far the largest country in Southeast Asia, both in population and in area. Forty-eight degrees of longitude on the equator, Indonesia covers almost one-seventh of the circumference of the globe and has long been prized for its abundant natural resources. Over a timeframe of three and a half centuries, the archipelago gradually came under Dutch colonial control, region by region. As a reflection of Dutch colonial wealth, the 17,000 islands were once described as a ‘belt of emeralds’ slung around the equator. Sulawesi, Kalimantan and Sumatra – three of the five main islands – are intersected by the equator but the other two, Java and Papua, are entirely in the southern hemisphere.

Not until the 20th century did Bali become part of the Dutch Realm and, after thirty years of war in the western extremity of the archipelago, so too did Aceh. In the eastern extremity, the territory of Netherlands New Guinea was twenty-three percent of the total area of the Indies and virtually untouched – a wilderness with jungle and precipice (in one location 3000m of sheer cliff) rising to cloud-forest, snow-capped mountains and glaciers, just below the equator – yet on international maps ‘Dutch’ since Napoleonic times. Colonial administration in Netherlands New Guinea, according to the official Dutch historian on the eve of World War Two (WW2) when the Japanese Imperial Army occupied the Indies, covered only five percent of the territory. So on August 17, 1945 when Sukarno declared independence, and General Douglas MacArthur’s troops had already re-occupied Netherlands New Guinea, we can say approximately 95% of the territory was occupied by the indigenous Papuan people. It was still ‘the land of the Papuas’24 as named by the Portuguese when they had unsuccessfully attempted to colonise the territory in the early 16th century.

During the four years after Sukarno proclaimed independence, Indonesians (mainly in Java and parts of Sumatra) desperately opposed all attempts to recolonise. On December 27, 1949, the Dutch relinquished sovereignty of the Netherlands East Indies but retained the territory of New Guinea, announcing a plan to develop it further and bring the indigenous people to independence. However, a campaign to oust the remnant colonial Dutch presence from New Guinea began in the early 1950s. Indonesia claimed the rightful extent of its territory was from Sabang Island, the western extremity of the Indonesian archipelago, to Merauke in the east, a distance of 5390 kilometres (3350 miles).

Ironically the anti-colonial campaign was focused on the continuing Dutch presence in New Guinea rather than the continuing Dutch presence in Indonesia, as pointed out by Herbert Feith.25 In newly independent Indonesia, he explained, referring to Indonesia at the start of the 1950s, ‘the largest chunks of economic power’ were still mainly in Dutch hands – ‘estate agriculture, the oil industry, stevedoring, shipping, aviation, modern-type banking … internal distribution, trade, manufacturing and insurance’ as well as exporting and, to a lesser degree, importing. It was no wonder that Sukarno often declared that the struggle for indepen- dence was ongoing, his ‘revolution’ not yet finished. Nevertheless, former Foreign Minister Sunario26 pointed out that, in the late 1950s, ‘US sources’ were providing covert funding for the Indonesian army to promote the anti-colonial campaign against the Dutch in New Guinea. Even though Sunario did not confirm the identity of the ‘US sources’, it should be pointed out that the Indonesian army by 1959 had benefitted immensely from Sukarno’s seizure of Dutch assets in Indonesia, as part of the New Guinea campaign. (Consequently, the Dutch companies pressured the Dutch government to relinquish sovereignty in New Guinea, so they could resume business as before in Indonesia.) The money from ‘US sources’ was not simply to assist the army as an investment against the PKI, but was explicitly for the anti-Dutch campaign to ensure it was not unduly influenced by the effusive campaign mounted by the PKI, even though these two anti-colonial streams ran in parallel. Sunario’s information was in the same vein as the concern expressed at that same time in the late 1950s by a prominent Australian politician, Dr Evatt, Leader of the Opposition in the Australian parliament and former President of the UN General Assembly. Evatt pointed to the possible involvement of US oil interests in the Indonesian quest to oust the Dutch from New Guinea, when he declared on November 14, 195727: ‘Surely we are not going to have an argument as to who should have the sovereignty of Dutch New Guinea unless the exploitation of that territory by certain interests is involved’.

After losing the Indies temporarily to Japan in 1942 and then losing the Indies permanently to Indonesia in 1949, it was not until the 1950s that the Dutch attempted to impose their stamp of colonial rule on the New Guinea territory. This brief period has been recalled in a positive light by many elderly Papuans in the coastal, urban areas because they enjoyed a vast improvement in health and education, but as the Dutch presence increased so did the anti-colonial cry of Indonesia. The claim that the territory should not have been excluded from being part of Indonesia in 1949 only grew louder. The dispute reached crisis level when Indonesia had acquired a centralised army command and arms from the Soviet Union, two of the three things that led to a settlement of the dispute. The third was US intervention.

A centralised command was an historic step forward for the Indonesian army. Prior to the CIA-assisted 1958 rebellion, the Indonesian army command system across the archipelago was a fractured patchwork of regional commanders fending for their troops. Sukarno himself was in part responsible for creating this disjointed army command in response to an attempted coup in 1952. With little financial support from Jakarta, the head of the army General Nasution had less control over his far- flung battalions than the respective colonels in the Outer Islands, and the CIA exploited this ‘tyranny of distance’. The dramatic change in army command structure, which was brought about by the PRRI/Permesta or Outer Islands Rebellion was engineered on a grand scale by Allen Dulles during the second Eisenhower administration.

Yet the end result of CIA interference in Indonesian internal affairs via the 1958 Rebellion was depicted as failure at the time, and has consistently been depicted as failure since that time. This holds true only if the stated goal of the CIA was the same as the actual goal. Even more than five decades later, media analysis of the goal of the Outer Island rebels is still portrayed as secession, as covert US support for ‘rebels in the Outer Islands that wished to secede from the central government in Jakarta’.28 The actual goal of Allen Dulles had more to do with achieving a centralised army command in such a way as to appear that the CIA backing for the rebels failed. Dulles was able to deceive, or was capable of deceiving, friend and foe alike, all those who were monitoring the ‘covert operation’ with secession in mind as the stated goal. In the opinion of Howard Jones written more than a decade after he was the US Ambassador in Jakarta in 1958: ‘To the outside world, the conflict was pictured as anti-Communist rebels against a pro-Communist government in Jakarta. In fact, it was a much more complex affair, involving anti-Communists on both sides’.29 In reality, Dulles’ aim was the formation of a central army command from the very start of the rebellion, while the perception of failure served as a lure to his Cold War opponents in Moscow. From the Cold War perspective, the perceived failure of the CIA operation offered Moscow an opportunity to increase its influence, which it did through an arms deal so large that it forced a conclusion to the Netherlands New Guinea sovereignty dispute.

The chief intelligence officer for the rebels was Colonel Zulkifli Lubis and the army commander under Sukarno was General Nasution. My extended interviews with both Lubis and Nasution (which began in Jakarta in 1983) have led to this completely different explanation for the so-called ‘CIA defeat’ in 1958. (As mentioned above) when Lubis declared ‘the Americans tricked us’, he was referring to the executive branch of government, not those in Sumatra. Nearly all the Americans who were involved onsite in Indonesia, genuinely helping the rebels, did not realise the rebellion was only the first stage of a larger intelligence scenario and their perception that the rebellion failed became an integral part of Dulles stratagem. In short, this 1958 operation (which is more fully explained in a later chapter) was an example of Dulles’ genius in intelligence. Another example was when Soviet penetration was suspected in the intelligence service of the British in the 1950s. It was Allen Dulles who first doubted the allegiance of Kim Philby before he finally defected to Moscow in 1963, an insight that may have helped generate Dulles’ failsafe stratagem in the Indonesian Outer Islands.

The combination of John Foster as Secretary of State and Allen as DCI during the Eisenhower presidency brought the surname ‘Dulles’ into the public limelight in the early post-war years, so much so that Allen Dulles became the face of US intelligence. This official appointment was acknowledgement of Allen’s known achievements and brought into play his vast underlying experience. There was implicit trust that his private networks and host of contacts (not only from the Second World War but also as far back as the First World War) would somehow be used in the service of the nation. This was not to be the case. Allen Dulles, the Cold War warrior par excellence, used these ‘unknown capabilities’ to achieve his own ends, which ultimately for the nation was a disservice. Many of his friends from the wartime Office of Strategic Services (OSS) utilised their skills when re-employed under DCI Dulles in the 1950s and 1960s. Earlier, with the Cold War looming when Dulles was OSS station chief in Berlin, working alongside him was a young Henry Kissinger.30 Allen had already acquired a legendary status as OSS station chief in Berne during the Second World War, and (as I mentioned in the Introduction) it was Allen Dulles whom the Japanese approached with the first indication of surrender. Perhaps the highest accolade, however, came from Sir Kenneth W.D. Strong who ‘dominated Britain’s spy services for twenty-five years’ and who was the top British representative in the surrender of German forces in Italy after initial negotiations conducted by Dulles. Strong declared Allen Dulles was the ‘greatest intelligence officer who ever lived’.31

Allen Dulles – Accused

From the First World War to the Warren Commission, Allen Dulles’ life was immersed in the world of intelligence, dealing with issues that ranged from empire to armaments, national security to regime change, oil, military and many other matters. In Berne during the Second World War, the assistance he provided the Allied war effort from contacts within Germany and his own expertise was nothing less than extraordinary; so much so that in the following decade, Dulles was regarded as an icon of US intelligence and any accusation to the contrary was readily dismissed. However, six years after his death in 1969, a US investigation chaired by Senator Frank Church produced a different profile of Allen Dulles. As part of fourteen reports on US intelligence activities, the Church Committee revealed that some of the activities former DCI Allen Dulles engaged in were nefarious in the extreme and these included the assassination of foreign leaders.

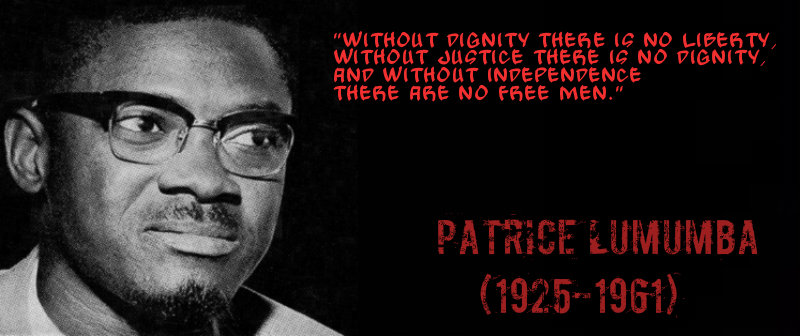

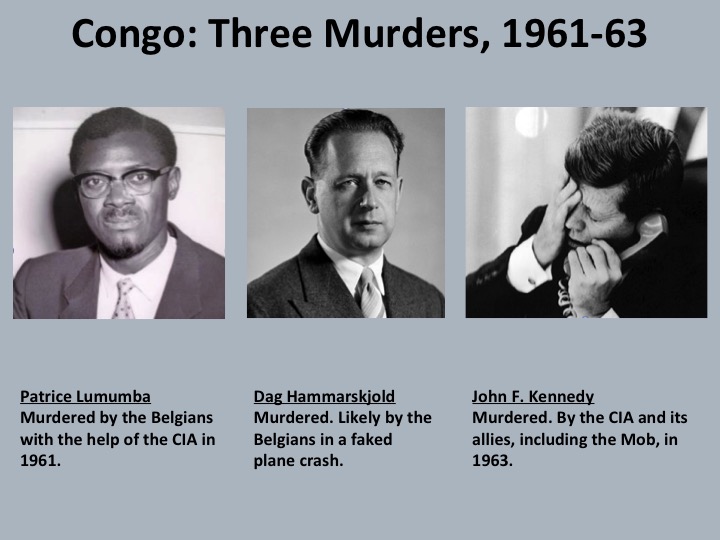

The Church Committee found that the political assassination of Patrice Lu- mumba in the Congo, which occurred three days before Kennedy’s inauguration, was directly instigated by Dulles. In arranging for an agent to kill Lumumba, Dulles had left a paper trail revealing his role in the form of a telegram to Leopoldville, September 24, 1960:

We wish [to] give every possible support in eliminating Lumumba from any possibility resuming governmental position….

The Church investigation found that

two days later the Congo CIA station

officer (Hedgman) contacted a CIA go-between named Joseph Scheider (alias Joseph Braun) who did not himself kill Lumumba but was responsible for the group of persons who did. Answering a Church Committee question, Hedgman replied:

It is my recollection that he (Dulles) advised me, or my instructions were, to eliminate Lumumba.

By eliminate, do you mean assassinate?

Hedgman: Yes.32

The killing of Lumumba, before he had served three months as the first Prime Minister of the Congo, involved much brutality and torture. This was public knowledge at the time; later, when added to the heinous role of Dulles as outlined in the findings of the Church Committee, it shocked the nation, indeed, shocked the world.

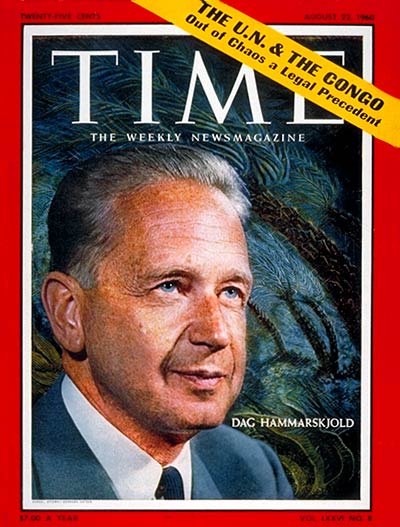

Political instability, created by the mineral rich province of Katanga wanting to break away from newly independent Congo, was fuelled by the killing of Lumumba. In September 1961, in the wake of the violence that erupted after Lumumba’s death, the UN Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjöld, became involved in mediation between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Katanga. A few minutes after midnight on Sunday, September 17, 1961, as the UN plane carrying the Secretary- General and 15 others was approaching the Ndola airstrip in Northern Rhodesia (today Zambia), it crashed, killing all.

Two Rhodesian enquiries in early 1962 concluded ‘pilot error – a misreading of the altimeters’ – had brought down the DC6, known as the ‘Albertina’. However, in March 1962, an investigation by the United Nations did not rule out sabotage although it fell short of stating officially that assassination was suspected. The Church Committee in 1975 did not make any links between Dulles and Hammarskjöld, and a 1993 investigation by the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs concluded the pilot had made an error in judging altitude. Persistent investigation by George Ivan Smith, who was the Secretary-General’s spokesman and close friend, unearthed a disturbingly vital clue that the plane was forced down as a result of interference by hostile aircraft. Whether this caused the crash remained inconclusive. In 1997, more documentary evidence on the death of Dag Hammarskjöld emerged – whether accidentally or deliberately, we may never know – attached to another document, but otherwise unrelated to the widespread investigation carried out by the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). This chance discovery provided the impetus for a new enquiry which was started in 2012 by the Hammarskjöld Commission. It acknowledged the TRC and examined the documents and letters in some detail to decide if any new evidence justified re-opening another investigation into the death of the Secretary-General. The report of the Hammarskjöld Commission was published in September 2013, fifteen years after the TRC documents had first emerged, and a Report tabled in the UN.33

In August 1998, the TRC Chairman, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, had called a press conference and released eight documents.34 These papers and letters were additional material discovered in a folder from the National Intelligence Agency. A member of the TRC had requested the folder, seeking information on a 1993 assassination in South Africa, and the additional material happened to be in that same folder the TRC received. The additional sheets of paper referred to an ‘Operation Celeste’ – a plan to assassinate Dag Hammarskjöld – and the letters showed Allen Dulles was involved. Details were included about a small bomb to disable the outside steering mechanism on the underside of the plane carrying the UN Secretary-General in September 1961. The documents bore the letterhead of the South African Institute for Maritime Research (SAIMR) and the name of Allen Dulles was specifically mentioned.

UNO [United Nations Organisation] is becoming troublesome and it is felt that Hammarskjöld should be removed. Allen Dulles agrees and has promised full cooperation from his people….35

Information from Dulles included the type of plane the UN Secretary- General would use and the date he would arrive. More importantly, even though the letter was signed by a person at SAIMR, it was directly conveying the words of DCI Dulles. As mentioned above, when Dulles initiated the killing of Lumumba, the evidence brought before the Church Committee was written by Dulles: ‘We wish [to] give every possible support….’

The wording here seems relatively innocuous but in the context of the Church Committee investigation, the sinister import in Dulles’ euphemism acquires a meaning far more significant. It is the order to kill – but not read as such without the explanation from the CIA station chief in the Congo that Dulles requested him to kill Patrice Lumumba. Otherwise the euphemistic expression ‘give every possible support’ might well have been interpreted as if Dulles had played a secondary role when, in fact, he initiated the action that led to the assassination of Patrice Lumumba. In the case of Hammarskjöld, the TRC document states that Dulles promised ‘full cooperation’ but this was written by a ‘commander’ of SAIMR, the intelligence organisation mentioned in the documents. The same commander then states:

I want his [Hammarskjöld’s] removal to be handled more efficiently than was Patrice.

This sentence also links SAIMR with Dulles, whom we know already initiated the killing of Patrice Lumumba. Up until the Church Committee proved otherwise, Lumumba’s death had been regarded as the tragic outcome of violence initiated by local tribespeople. But the order to kill Lumumba was given by Dulles, to be carried out by SAIMR, and local people were involved only in the final act. Using the similar euphemistic term of ‘promising full cooperation’, an equivalent scenario for Operation Celeste would have Dulles (from his office in Washington) initiating the killing of the UN Secretary-General, and for the operators, SAIMR (as revealed in the TRC documents) to carry out the assassination using lo- cally based European mercenaries including a pilot or two in the final act.

The ‘Operation Celeste’ documents were examined in 2011 by Susan Williams in her book Who Killed Hammarskjöld with extensive research into SAIMR. She concluded that it was involved in covert action over many years, and that its structure was in ‘cells’ which operated independently. This raises the possibility that ‘Operation Celeste’ involved SAIMR cells for three separate actions against Hammarskjöld’s plane involving hostile aircraft, a 6kg bomb to disable the steering mechanism and the altimeters.

There is a strong possibility that the altimeters were sabotaged as one way of bringing about a crash. The 2013 Commission presented reliable evidence that incorrect barometric readings (QNH) were given to the Albertina by Ndola air traffic control. Attention was drawn to the fact that the voice recordings of the air traffic controller at Ndola were turned off, possibly deliberately. As well, before the Albertina (Hammarskjöld’s plane) departed for Ndola, where it crashed, there was a four-hour period when the plane was left unattended. If altimeters in the cockpit of the Albertina were sabotaged, how was it possible sabotage was not detected in subsequent testing of the altimeters? In the ‘Comments from the United Nations’ (attached to the 1962 crash report) it was stated there could have been a ‘misreading of the altimeters’36 as the DC6, just after midnight descended to 5000ft and was doing a procedural turn in preparation to land when it clipped trees and crashed at 4357ft. The action of a small fighter plane, which began to harass the DC6 in the final few minutes of descent, made the advice coming from Ndola air traffic control vitally important because the pilot at that moment would have been relying entirely on air traffic control and his own reading of the altimeters.

Immediately after the crash in September 1961, one of the first actions was removal of the altimeters. There were two CIA planes waiting at Ndola airport, ready to offer assistance. The altimeters were checked in the USA and the all clear was given by J. Edgar Hoover whose FBI intelligence network often overlapped with Dulles’ CIA. The 2013 Commission findings do not seem to have even considered the possibility that the ‘official check’ on the altimeters might have been fraudulent.

Although it has been suggested that a false QNH was given to the Albertina on its approach to Ndola, all three altimeters were found after the crash to be correctly calibrated.37

The Commission tended to dismiss reliable evidence that the Albertina was given a false QNH on its approach simply because they did not consider the possibility that J. Edgar Hoover’s check on the altimeters might have been fraudulent. J. Edgar Hoover’s affiliation with Dulles needs no explanation (other than to say Kennedy re-appointed them both together). Because the Celeste documents refer to Allen Dulles in the plot to assassinate the UN Secretary-General, the reliability of the check on the altimeters must be seriously questioned.

In the United Kingdom in 1983, I interviewed two UN officers, Conor Cruise O’Brien who was in the Congo at the same time as Hammarskjöld, and George Ivan Smith who was there soon after the crash. Both UN officials expressed their belief that the Secretary-General was assassinated, despite the inconclusive evidence of the official investigations. Three times I visited George Ivan Smith38 who lived at Stroud in Gloucestershire.

He had at first worked also alongside Hammarskjöld’s predecessor, Trygve Lie, a Norwegian. The first Secretary-General of the United Nations resigned in 1953, making way for Dag Hammarskjöld from Sweden. He and George Ivan Smith worked together over a period of eight years, becoming close friends. Ivan Smith was a trusted associate of Hammarskjöld, at times taking on a dual role as spokesman and confidant. It was in this role, Ivan Smith explained to me, discussing hopes and aspirations, the Secretary-General referred to an impending UN announcement which Hammarskjöld had been formulating in the preceding months of 1961. He fully intended to implement his plans upon his return from the Congo, but he never did and the announcement died with him! The Secretary-General arrived in Leopoldville on September 13, 1961, a few days before the fatal flight to Ndola where the plane crashed shortly after midnight on September 17/18th.

Before Dag Hammarskjöld departed on the mission of mediation which claimed his life, George Ivan Smith noted that the Secretary- General was very much focused on the plan he intended to launch at the UN General Assembly after dealing with the unrest in the Congo. Hammarskjöld had been conducting private talks with President Kennedy about the long running dispute between Indonesia and the Netherlands over sovereignty of West New Guinea. Leading up to the General Assembly meeting in 1961, these talks had crystallised into new UN policy. At the same time, Kennedy had also engaged in confidential discussion on this and other issues with former president, Harry S. Truman (who one year earlier had doubted whether the youthful JFK had the foreign policy experience that was needed in the White House.) During his first year in office, Kennedy and his wife, Jacqueline, so much won the approval of Mr and Mrs Truman that they were known to stay overnight with the Kennedy family in the White House.

In terms of wending one’s way through Cold War issues, Kennedy’s understanding with Hammarskjöld over the proposal to resolve the New Guinea sovereignty dispute, which now held the potential for conflict with Moscow, no doubt had Truman’s support. Hammarskjöld’s resolve to implement a policy of ‘Papua for the Papuans’ was in effect a countermeasure to rising Cold War tension, an example of his Swedish- style ‘third way’ proposing a form of ‘muscular pacifism’.39 His plan was to annul all claims to sovereignty other than the indigenous inhabitants and to announce this at the UN General Assembly in October/November 1961, but his death occurred in September.

Surprisingly, Harry S. Truman, expressing his opinion on the tragic news to reporters of the New York Times on September 20, 1961, commented enigmatically:

Dag Hammarskjöld was on the point of getting something done when they killed him. Notice that I said ‘When they killed him’.

The report in the New York Times continued:

Pressed to explain his statement, Mr Truman said, ‘That’s all I’ve got to say on the matter. Draw your own conclusions’.

The Hammarskjöld Commission in 2013 commented on the statement to the press made by Harry S. Truman:

There is no reason to doubt the accuracy of the New York Times’ report. What we consider important is to know what the ex-President, speaking (it should be noted) one day after the disaster, was basing himself on. He is known to have been a confidant of the incumbent President, John F. Kennedy, and it is unlikely in the extreme that he was simply expressing a subjective or idiosyncratic opinion. It seems likely that he had received some form of briefing.40

The UN Secretary-General had Kennedy’s support in formulating a plan to make the UN a central player in the sovereignty dispute over Netherlands New Guinea. From Kennedy’s perspective, Hammarskjöld was proposing a welcome initiative because it would preclude the inevitable criticism of the alternative decision Kennedy himself would be forced to make: that is, if the UN did not assume full responsibility for the Papuan people in the disputed territory of West New Guinea, then Kennedy would be forced to choose between Indonesia and the Netherlands. Hammarskjöld no doubt was aware there would be opposition to his planned intervention in the Dutch-Indonesian sovereignty dispute, not only from the two principal disputants, the Netherlands and Indonesia, but also from both the Soviet Union and China, both of whom supported Indonesia’s quest to expel Dutch colonial power from New Guinea. While it cannot be said that the UN Secretary-General or President Kennedy were oblivious to the personal and political risk they were taking in pursuing this approach to the New Guinea sovereignty issue, neither of them seemed fully aware of how high the stakes were; or rather, how high the stakes were for others who were involved – such as Allen Dulles. The battle for sovereignty of Netherlands New Guinea, from Dulles’ perspective, involved far more than the plight of the indigenous inhabitants: it had become a key issue in the struggle to ‘win’ Indonesia and so (by virtue of Indonesia’s internal politics centred on the PKI, and the offer of Soviet arms to oust Dutch colonial power) also an issue in the Sino-Soviet dispute. Papua, the PKI and Indonesia itself was all part of the ‘wedge between Moscow and Beijing’. Hammarskjöld’s radical initiative to reclaim Papua from past and future colonial rule – upgrading in the process the status of the UN to protect indigenous peoples – would have totally disrupted the Indonesia strategy of Allen Dulles.

In terms of the totality of the disruption, both the UN Secretary- General and the US President were mostly oblivious to Dulles’ geopolitical machinations. The effect of Hammarskjöld’s plan bears a striking similarity to the effect which JFK’s planned visit to Jakarta would have had on Dulles’ Indonesia strategy. Because of this similarity, Dulles’ alleged involvement in the death of Hammarskjöld (through ‘Operation Celeste’) can be seen as a precedent for Dulles’ involvement in the death of Kennedy.

OPEX

Hammarskjöld’s planned intervention to settle the New Guinea dispute peacefully was following ‘unchartered UN guidelines’ but generally came within the ambit of the 1960 UN Declaration. This was a call for ‘the speedy and unconditional granting to all colonial peoples of the right of self-determination’. There were still 88 territories under colonialist administration waiting to become independent national states. Had the UN Secretary-General succeeded in bringing even half of these countries to independence, he would have transformed the UN into a significant world power and created a body of nations so large as to be a counterweight to those embroiled in the Cold War. Cameroon, for example, with a land area the same as West New Guinea, had formerly been under French and English administrations. In March 1961, the people of Cameroon conducted voting under the auspices of the United Nations Plebiscite Commissioner for Cameroons. The people of the Northern Cameroons decided to achieve independence by joining the independent Federation of Nigeria, whereas the people of the Southern Cameroons similarly decided to achieve independence by joining the independent Republic of Cameroon.

Hammarskjöld was especially concerned about indigenous tribes- people. In the case of West New Guinea, Hammarskjöld’s intention was to declare both the Dutch and the Indonesian claims to sovereignty of the territory as invalid. He proposed to assist the Papuan people by declaring a role for the United Nations alongside an independent Papuan state, using UN officers to advise the main government departments. A United Nations Special Fund had been established, as he explained in an address to the Economic Club of New York on March 8, 1960, where he outlined this revolutionary approach already being implemented in some former colonial territories in Africa:

We have recently initiated a scheme under the title of OPEX – an abbreviation of ‘operational and executive’ – whereby the UN provides experienced officers to underdeveloped countries, at their request, not as advisers, and not reporting to the UN, but as officials of the governments to which they have been assigned and with the full duties of loyal and confidential service to those governments. OPEX officials have already been requested by, and assigned to, several newly-independent countries, and I hope that we may be able to use the scheme much more widely in the years to come.

As Williams has noted: ‘The activities of the UN in New York were vigorously scrutinised by the CIA’.41 Applying OPEX in West New Guinea, Hammarskjöld was threatening to take the territory and its natural resources out of the hands of all aspiring colonial powers and out of the hands of Rockefeller Oil which had first staked its claim before the Second World War. This solution to the sovereignty dispute was the antithesis of what Dulles had planned, using the Cold War to his advantage, by encouraging Jakarta to purchase Soviet armaments for the Indonesian Navy and Air Force. Hammarskjöld was constructing a solution for the Papuan people capable of withstanding Cold War pressure because he had Kennedy’s support.

Criticism of Hammarskjöld came from both Cold War blocs. In the ensuing turmoil, both East and West seemed to have their own motives to ‘remove Hammarskjöld’. The CIA was working conjointly with British intelligence, according to the Celeste documents, a precursor of the joint force used to spark Malaysian Confrontation. Given the political situation in mineral rich Katanga, there was no shortage of mercenaries but the overriding motive was that ultimate responsibility for the (Irish) UN troops who were pitted against Katanga lay with the UN Secretary- General (rather than Conor Cruise O’Brien). The killing of Lumumba had already displayed a willingness to resort to murder and mayhem, and no doubt the radicalised mercenary element was capable of taking the life of the UN Secretary-General. Two mercenaries (according to the 2013 Commission Report) were at the Ndola airport in the group awaiting the arrival of Hammarskjöld on the night of the crash.

However, the primary motive for Dulles’ participation was not the same as other participants in this tragic episode. His involvement in the assassination seemed driven by Cold War issues whereas the Belgian and British interests were more directly tied to the Katanga dispute. In the eyes of some, this may have added credibility to the secondary position Dulles seemed to adopt in ‘Operation Celeste’ – offering ‘…every possible support…’ but in reality Dulles’ motive to eliminate Hammarskjöld for interfering in the New Guinea dispute was far greater than any apparent motive Dulles may have had in the Congo. He was so far ahead of his contemporaries they did not suspect him of pushing a button, or causing a death, on one side of the world to benefit a covert strategy of his on the other side of the world.

When I spoke with George Ivan Smith, he raised two important points which (in the context of ‘Operation Celeste’) now link Dulles to Ndola. The first (as mentioned above) was that Hammarskjöld was going to announce at the General Assembly in New York his solution to the West New Guinea sovereignty dispute; and secondly, there was a CIA plane full of communication equipment, its engines operating but stationary on the Ndola airstrip, the same night that Hammarskjöld’s plane was due to land. Two such planes had just arrived at Ndola but only one of these was operating on the night, its engines running to provide power for the communications equipment that the CIA personnel were using inside the plane. The Commission Report drew attention to the CIA communication planes:

Also on the tarmac at Ndola on the night of 17 September were two USAF aircraft. Sir Brian Unwin’s recollection, in his evidence to the Commission, was that one had come in from Pretoria and one from Leopoldville, where they were under the command of the respective US defence or air attachés. Of these aircraft he said: ‘Those planes we understood had high powered communication equipment and it did occur to us to wonder later, whether there had been any contact between one or other of the two United States planes with Hammarskjöld’s aircraft, as they had, we understood, the capability to communicate with Hammarskjöld’s plane. …I do recall that when we saw these two planes on the ground we were … saying ‘Wonder what they’re up to’.

One of the conclusions of the Commission Report was to seek the voice transmissions from the cockpit of the Albertina in the minute or so before the fatal crash. The CIA communications plane on Ndola airstrip, as shown above, had the capacity to communicate with the Albertina and may well have made a record of the final words coming from the Albertina. But given the level of involvement of Allen Dulles, it is highly unlikely that self-incriminating evidence would ever be made available.

The Commission Report has drawn attention to several possible causes of the fatal crash – the presence of another plane that fired at Hammarskjöld’s DC6, the altimeters and a small explosive device to render the Albertina’s steering mechanism inoperable. It is possible (as mentioned above) that SAIMR tried to utilise all three. The Commission alluded to the possibility of igniting the explosive device by radio control, but it remained unclear whether this could have been done from another plane flying near the Albertina or from the Ndola airstrip.

Earlier in his eight-year span as UN Secretary-General, during the McCarthy era, Hammarskjöld had forcefully evicted Hoover’s FBI men from the UN building, but in September 1961 the tables had turned and Hammarskjöld was ousted – by assassination.

As a senator, Kennedy had first met UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld several years earlier, and as President-elect they met again to discuss the more urgent problems of the world. During 1961, Hammarskjöld’s proposed intervention in the New Guinea sovereignty dispute was the solution JFK preferred to solve an unwanted dilemma. OPEX implemented for the Papuan people meant Kennedy would not be forced to decide between supporting the colonial administration of a NATO ally or supporting the Indonesian administration over the Papuan people against the wishes of a NATO ally. With Hammarskjöld’s death, the pro-Papua plan was abandoned.42 So the Papuan people in the western half of New Guinea, who were on the verge of becoming an independent state under the auspices of the United Nations, were left hanging in history. Hammarskjöld’s death left Kennedy one of two options, the Dutch or the Indonesian, but Dulles’ preparation ensured Kennedy chose the latter.

Hammarskjöld positioned himself (and the role of the UN) between or above the Cold War blocs. He intended implementing OPEX to resolve the New Guinea sovereignty dispute but did not take into account the extent of covert involvement by Standard Oil and Allen Dulles. At the funeral of Dag Hammarskjöld, September 29, Kennedy described him as ‘the greatest statesman of the 20th century’.

Notes

- Howard Palfrey Jones, Indonesia: The Possible Dream, Gunung Agung, Singapore, 1980, p. 298. (First ed. 1971, Hoover Institution Publications).

- Nor were critics simply along East-West lines in the Cold War conflict, as Beijing fully supported Confrontation but Moscow did not. Continued hostilities delayed Indonesian elections which Moscow wanted in order to open the door to government for the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). Moscow’s disapproval of Confrontation was strong but subdued to avoid Sino-Soviet rivalry which – as the PKI were already involved in Confrontation – would advantage only Beijing.

- Bradley R. Simpson, Economists with Guns, p. 98.

- Baskara T. Wardaya, SJ, Cold War Shadow – United States Policy toward Indonesia, 1953–1963, Galang Press, Yogyakarta. 2007, p. 377.

- Thomas Preston, The President and His Inner Circle Leadership Style and the Advisory Process in Foreign Policy Making, Columbia University Press, 2001, pp. 113–114.

- Bradley R. Simpson, Economists with Guns, Stanford University Press, 2008, p. 5.

- Simpson (p. 69) has incorporated quotations from the Memorandum of Discussion at the 410th Meeting of the NSC, Washington. FRUS, 1958–59, Vol. XVI, pp. 97–103.

- FRUS, Vol. XXIII, Southeast Asia, Doc. 155. ‘Memorandum from the Deputy Director for Plans, Central Intelligence Agency (Bissell) to the President’s Special Assistant for National Security Affairs (Bundy)’. Attachment ‘Indonesia Perspectives’, see paragraphs 9 & 10. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/ frus1961-63v23/d155

- David Ransome, ‘The Berkeley Mafia and the Indonesian Massacre’, Ramparts 9, 1970, pp. 26-49.

- Howard Palfrey Jones, Indonesia: The Possible Dream, Gunung Agung, Singapore, 1971, p. 296.