Neil Sheehan passed away on January 7th. His death would have attracted more attention if it had not occurred the day after the Trump/Giuliani inspired insurrection at the Capitol in Washington DC. We will give his death more than passing notice because, in a real way, the Establishment-honored Sheehan represented much of what was wrong with the New York Times, and big book publishing in general. So if our readers are looking for an adulatory or commemorative eulogy for Sheehan, they should go over to the NY Times. It won’t be found here.

Sheehan was born of Irish parents in Holyoke Massachusetts and graduated from Harvard in 1958. After his military service he went to work for UPI in Tokyo. He spent two years as UPI’s chief correspondent covering the Vietnam War. It was at this time––1962-64––that he became collegial and friendly with the Times’ David Halberstam. And he was then employed by the Grey Lady.

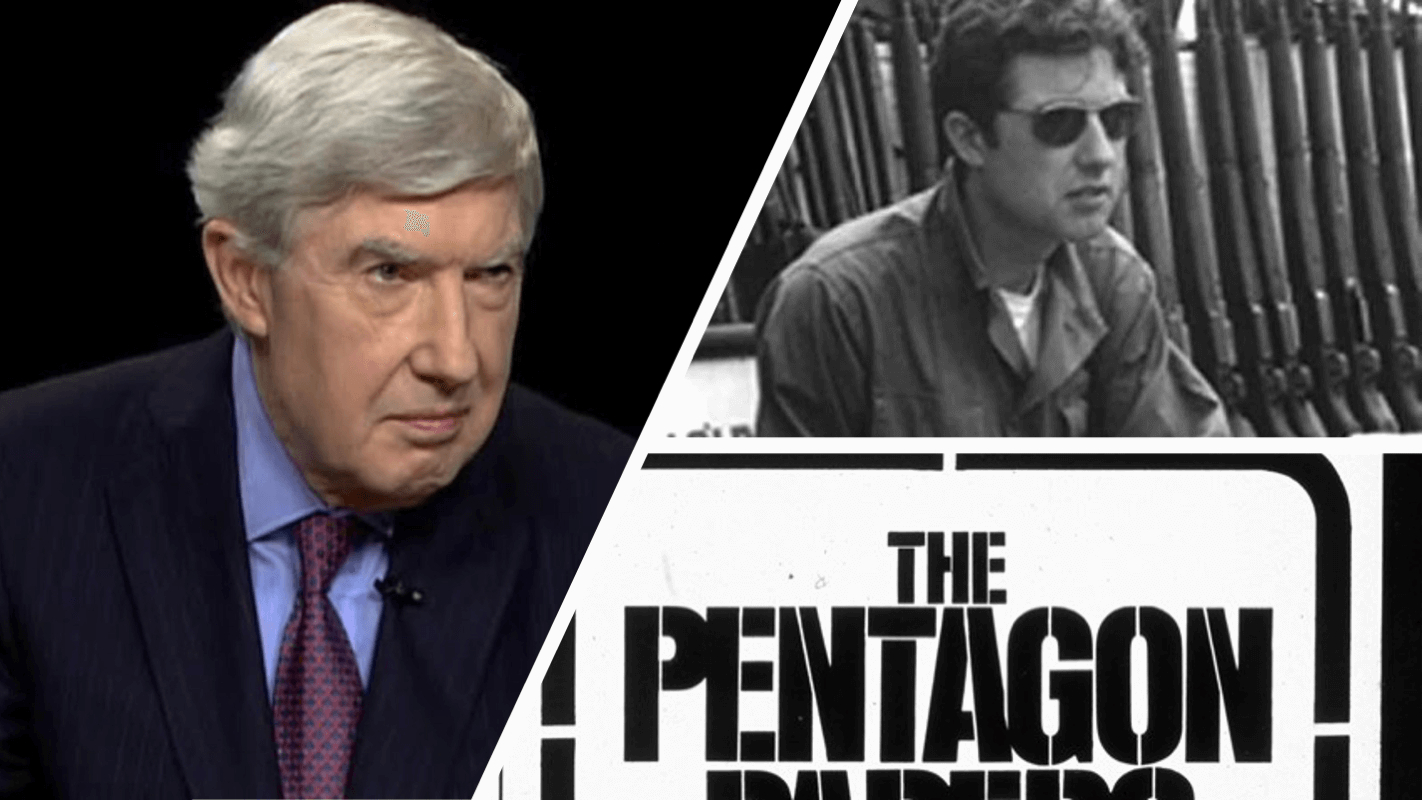

As the reader can see from the picture above, Sheehan and Halberstam rode in helicopters with the military to cover the war. From the looks on their faces, they appear to have enjoyed the assignment. In fact, in the Ken Burns/Lynn Novick documentary series The Vietnam War, Sheehan said he found these helicopter sorties exciting to be involved with.

The commander in Vietnam at that time was General Paul Harkins. Since those two reporters were intimately involved with the actual military operations, they knew things were not going well. Yet Harkins insisted they were going fine. As author John Newman wrote in his milestone book JFK and Vietnam, this rosy outlook was an illusion perpetrated by both military intelligence and the CIA. It was carried out by Colonel James Winterbottom with the cognizance of Harkins. (Newman, 1992 edition, pp. 195-97). In a 2007 interview that Sheehan did, he said that he and Halberstam had a conflict with Harkins over this issue of whether or not Saigon and the army of South Vietnam (the ARVN) was actually making progress against the opposing forces in the south, namely the Viet Cong. He said that their impression was that Saigon was losing the war. Their soldiers were reluctant to fight, the entire military hierarchy was corrupt, and as a result, the Viet Cong forces in the south were getting stronger and not weaker.

There is one other element that needs to be addressed before we move further. It is something that David Halberstam did his best to forget about in his 1972 best-seller The Best and the Brightest, but Sheehan was more open about in his 2007 interview. The smiles in the picture above were genuine because Sheehan and Halberstam truly believed in winning the Vietnam War. At any and all costs. As Sheehan further explicated about the duo:

… we believed it was the right thing to do. We believed all those shibboleths of the Cold War, all of which turned out to be mirages : the “domino theory” that if South Vietnam fell, the rest of––Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia––they were all going to fall one by one. We believed the Vietnamese Communists were pawns of the Chinese and the Russians, they were taking their orders from Moscow and Bejing. It was rubbish. They were independent people who had their own objectives, and they were the true nationalists in the country. We didn’t know any of this really, but we did know we were losing the war.

I was quite fortunate to find this interview. Because I had never seen Sheehan or Halberstam be so utterly explicit about who they were and what they were about at that time. In his entire 700 page book, The Best and the Brightest, and later in his career, I never detected such a confessional moment from Halberstam. The simple truth was that Sheehan and Halberstam were classic Cold Warriors who wanted to kick commie butt all the way back to China. They saw what America was doing as some kind of noble cause. They felt that we and they––that is, all good Americans––were standing up for democracy, liberty and freedom. As far as political sophistication went, they might as well have been actors performing in John Wayne’s propaganda movie, The Green Berets. They wanted a Saigon victory with big brother America’s help. Which is the message of the last scene of Wayne’s picture. And they didn’t think Harkins was up to the task. In fact, they did not even know what Harkins was up to with his attitudinizing about America winning the war.

II

Neither Harkins nor Winterbottom was unaware of the true situation on the ground. In fact, as Newman shows in his book, Winterbottom would simply create Viet Cong fatalities out of assumptions he made. Harkins understood this and went along with it. (Newman, p. 224) The idea was to control the intelligence out of Saigon in order to bamboozle Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. (Newman, p. 225) There were honest records kept. But throughout that year of 1962, whenever McNamara would report back to President Kennedy after one of his SecDef Meetings––a conference in the Pacific of all American agency and division chiefs in Saigon––he would deliver to the president the same rosy message he had just heard. And that message was false in two senses: the number of Viet Cong casualties was exaggerated, and the number of ARVN casualties was being reduced. (Newman, p. 231)

This intelligence deception was happening in the spring of 1962. In November of 1961, with his signing of NSAM 111, Kennedy had agreed to raise the number of American advisors and ship more equipment to Saigon. Therefore, the true results on the battlefield in the spring of 1962 would denote that this was not really helping the war effort. As Newman wrote, the Viet Cong “had been quick to alter their tactics to counter the effectiveness of the helicopter: quick strikes followed by withdrawal in fifteen minutes to avoid rapid reaction … .” (p. 233)

At about this time, in April of 1962, President Kennedy sent John Kenneth Galbraith to visit Robert McNamara in Washington. He told Galbraith to give him a report that JFK had requested the ambassador to India write about the American situation in Vietnam. Kennedy knew that Galbraith was opposed to increased American involvement in Indochina, since he had voiced those doubts to the president before. As James Galbraith, the ambassador’s son, said to me, Kennedy fully understood that what Galbraith would write would counter the hawks in his cabinet. (phone interview of July, 2019) Kennedy wanted the report to go to McNamara since the Defense Secretary could then begin to withdraw the (failed) American military mission. Galbraith did so and he then told JFK that McNamara got the message. (see this article)

One month later, McNamara had a SecDef meeting in Saigon. After that meeting, he instructed Harkins––and a few others military higher ups––to stick around for a few minutes. He told them, “It is not the job of the U.S. to assume responsibility for the war but to develop the South Vietnamese capability to do so.” (James Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable, p. 120) He then asked them to complete the ARVN training mission and to submit plans for a dismantling of the American military structure in South Vietnam. He concluded by telling Harkins:

… to devise a plan for turning full responsibility over to South Vietnam and reducing the size of our military command, and to submit this plan at the next conference. (Douglass, p. 120)

To me, and to any objective person, this has to be considered quite important information. First, the message is quite clear and unambiguous: McNamara is saying we can only train the ARVN. Once that is done, we are leaving; we cannot fight the war for them. Second, it is multi-sourced: from both Galbraith, and the people at the SecDef meeting in Saigon. In addition, when word got out that Kennedy had sent the memo to McNamara, a mini war broke out in Washington over what was happening. (Newman, pp. 236-37). Then in May of 1963, the withdrawal schedules were delivered to McNamara at another SecDef meeting. (James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed, second edition, p. 366)

Now, here is my plaint to the reader: try to find this step by step by step milestone in Halberstam’s book. That is, from:

- Galbraith visiting Kennedy, to

- Galbraith seeing McNamara, to

- McNamara ordering Harkins to begin the dismantling of the American mission, to

- The withdrawal schedules being presented to McNamara.

If you can find it, let me know. Because even though I read the book twice, I could not locate any of it. Also, try to find it in any of the many interviews that Sheehan did that are online. On the contrary, both men always spoke of the “inevitability” of the Vietnam War. You can only maintain such a stance if you do not reveal the above information. In fact, it can be fairly stated that, in 700 pages, Halberstam essentially gives the back of his hand to the influence of Galbraith on Kennedy. And he also completely reverses the roles of McNamara with Kennedy in Vietnam. Halberstam wrote that it was McNamara who went to Kennedy, “because he felt the President needed his help.” (Halberstam, p. 214) He then says, on the next page, that McNamara had no different ideas on the war than Kennedy did.

Let us be frank: This is a falsification of the record. It was Kennedy who, through Galbraith, went to McNamara. And it was not for the purpose of promoting the ideas of the Pentagon on the war. Now, if the alleged 500 interviews Halberstam did were not enough to garner this information, there was another source available to him: the Pentagon Papers––which Halberstam says he read. Moreover, he says they confirmed the direction he was going in. (Halberstam, p. 669)

Either Halberstam lied about reading the Pentagon Papers, or he deliberately concealed what was in them. Because in Volume 2, Chapter 3, of the Gravel Edition of those papers, the authors note that because progress had been made, McNamara directed a program for the ARVN to take over the war and American involvement to be phased out. That phasing out would end in 1965. Is it possible for Halberstam to have missed this? The information appears in the chapter explicitly headed, “Phased Withdrawal of US Forces, 1962-64.” That chapter is forty pages long. (see pp. 160-200)

III

At that time period when the two reporters were in Vietnam, not only did they both want to urge America and Saigon to victory. They thought they found the man to do it. That was Colonel John Paul Vann. In fact, before he wrote The Best and the Brightest, Halberstam wrote another book on Vietnam, called The Making of a Quagmire. It is a book that he wished everyone would forget. Unfortunately for the deceased Halberstam, it’s still in libraries. In that book, Halberstam criticized every aspect of the Saigon regime as led by America’s installed leader, Ngo Dinh Diem. Halberstam writes toward the end that “Bombers and helicopters and napalm are a help but they are not enough.” (p. 321) He then adds, “The lesson to be learned from Vietnam is that we must get in earlier, be shrewder, and force the other side to practice self-deception.” (p. 322) In other words, at that time, Halberstam and Sheehan wanted direct American intervention; as did Colonel Vann.

What this reveals is something important about the trio: They had no reservations about the war America had involved itself in. America got in by its backing of France. When France was defeated, the USA took its place. America then violated the Geneva Accords peace treaty that ended the war. The USA would not hold free elections in order to unify the country. America created a new country called South Vietnam, one that did not exist before. And they installed their own handpicked leader, Ngo Dinh Diem, to rule over it. Diem’s early regime was stage-managed by General Edward Lansdale. According to the first chapter of Sheehan’s book about Vann, A Bright Shining Lie, Lansdale was Vann’s hero.

Both Sheehan and Halberstam fell in love with Vann. They were completely unaware of what was happening in Washington, how Kennedy had decided to take Galbraith’s advice and begin to remove all American advisors. They wanted to win, and they both felt it was only through Vann that the war could be won. They both maintained that he was the smartest man for Harkins’ position.

There was a serious problem with the approach of these three men in 1965. None of them ever raised the fundamental question of what America was doing in Vietnam, or how we got there. Lansdale was not building a democracy. He was building a kleptocracy. He also rigged elections so Diem could win by huge margins. (Seth Jacobs, Cold War Mandarin, p. 85) He was constructing the illusion of a republic when, in fact, none existed. Diem was soon to become a dictator. (Jacobs, p. 84) For Vann to make Lansdale his role model is a troubling aspect of the man.

One of the reasons Kennedy decided to get out is simple: he did not think Saigon could win the war without the use of American combat troops. Or as he told Arthur Schlesinger:

The war in Vietnam could be won only so long as it was their war. If it were converted into a white man’s war, we would lose as the French had lost a decade earlier.” (Gordon Goldstein, Lessons in Disaster, p. 63)

Kennedy said the same thing to NSC aide Michael Forrestal: America had about a one-in-a-hundred chance of winning. The president said this on the eve of his going to Dallas in 1963. He then added that upon his return there would be a general review of the whole Vietnam situation, how we got there, what we thought we were doing, and if we should be there at all. (James Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable, p. 183)

The point about it becoming a white man’s war and the whole French experience echoes back to Kennedy visiting Saigon in 1951. There he met with American diplomat Ed Gullion who told him France would never win the war, and the age of colonialism was coming to an end. (Douglass, p. 93) That visit and the meeting with Gullion had a profound effect on Kennedy’s world view. He now saw nationalism as the main factor in these wars in former European colonies. He also thought that anti-communism was not enough to constitute an American foreign policy. America had to stand for something more than that. (For the best short discussion of this, see James Norwood’s essay on the subject.)

And there was a further difference between JFK and the Establishment on Third World nationalism. Kennedy did not see the world as a Manichean, John Foster Dulles split image. Unlike President Eisenhower, he did not buy into the domino theory. It was no one less than National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy who said this about Kennedy in an oral interview he did in 1964. (Goldstein, p. 230) This is why, as Gordon Goldstein wrote in his book about Bundy, Kennedy turned aside at least nine attempts by his advisors to commit combat troops into Vietnam during 1961.

IV

It’s very clear from the interviews that Sheehan did later in his life that, like Halberstam, he had a problem with admitting Kennedy was right, and he, Halberstam and John Paul Vann were wrong about Vietnam. To fully understand Sheehan, one has to refer to the first chapter of A Bright Shining Lie, his book about Vann. That chapter is called “The Funeral”. It describes the ceremony preceding Vann’s burial. Consider this assertion about 1961:

The previous December, President John F. Kennedy had committed the arms of the United States to the task of suppressing a Communist-led rebellion and preserving South Vietnam as a separate state governed by an American sponsored regime in Saigon.

If Kennedy had thus committed himself, then why had he told McNamara in 1962 that he was to start a withdrawal program? And it’s no use saying that ignorance is an excuse for Sheehan. Peter Dale Scott understood such was not the case when he wrote about Kennedy and Vietnam originally back in 1971. Kennedy simply did not see South Vietnam as a place the USA should pull out all the stops for. John Paul Vann did see it as such. So did Halberstam and Sheehan.

Sheehan also describes Ted Kennedy arriving late at the funeral and sitting in a back pew. He writes that Ted had turned against the war that his brother, “John had set the nation to fight.” Nothing here about President Eisenhower creating this new nation of South Vietnam that did not exist before. He then adds that John Kennedy wanted to extend the New Frontier beyond America’s shores. And the price of doing that had been the war in Vietnam.

I think we should ask a question right here: Why not mention Bobby Kennedy’s antagonism against the war in Vietnam, which was clearly manifest during Lyndon Johnson’s presidency? In fact, as author John Bohrer has written, Robert Kennedy had warned President Johnson against escalation as early as 1964. (The Revolution of Robert Kennedy, p. 70). Kennedy had told Arthur Schlesinger that, by listening to Eisenhower, Johnson would escalate the war in spite of his advice. (Bohrer, p. 152)

When Halberstam heard about this, he now began to criticize RFK. How dare Bobby imagine that he was smarter than Johnson and Ike on the war. What did Robert Kennedy think? You could win the war without dropping tons of bombs and using overwhelming force? Again, this exchange exposes who Halberstam and Sheehan really were in 1965. If I had been that wrong, I would have excised it also.

As per extending the New Frontier beyond its borders, this is contrary to what Kennedy’s foreign policy had become after his meeting with Gullion. JFK was trying for a neutralist foreign policy, one that broke with Eisenhower’s, and tried to get back to Franklin Roosevelt’s. And as anyone who reads this site knows, this is amply indicated by his policy in places like Congo and the Dominican Republic.

What Sheehan is doing here is pretty obvious. He is transferring his guilt about who he was, and what he did while under Vann’s spell, onto Kennedy. In fact, Kennedy was opposed to what both Halberstam was writing and what Vann was advocating for about Vietnam. As proven above, JFK did not want America to take control of the war––to the point that President Kennedy tried to get Halberstam rotated out of Vietnam. (David Kaiser, American Tragedy, p. 261) I also think this is the reason that Sheehan never acknowledged that Kennedy was withdrawing from Indochina in any interview I read with him. And considering some of these interviews were done after the controversy over Oliver Stone’s film JFK, that is really saying something.

V

There are two other highlights to Sheehan’s journalistic career with the Times. One concerned his association with Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers. Ellsberg had been in Vietnam on a voluntary tour under Ed Lansdale from 1965-67. He went there from the Defense Department in order to see what the Vietnam War was really like. He spent six weeks being shown around Saigon by Vann. (Steve Sheinkin, Most Dangerous, p. 77) As he notes in his fine book Secrets, Ellsberg came back a different man. He could not believe how badly the war was going, even though President Johnson had done what Kennedy refused to do: insert combat troops. By 1967 there were well over 400,000 of them in theater. This certified what President Kennedy had told Schlesinger about making it an American war and ending up like the French.

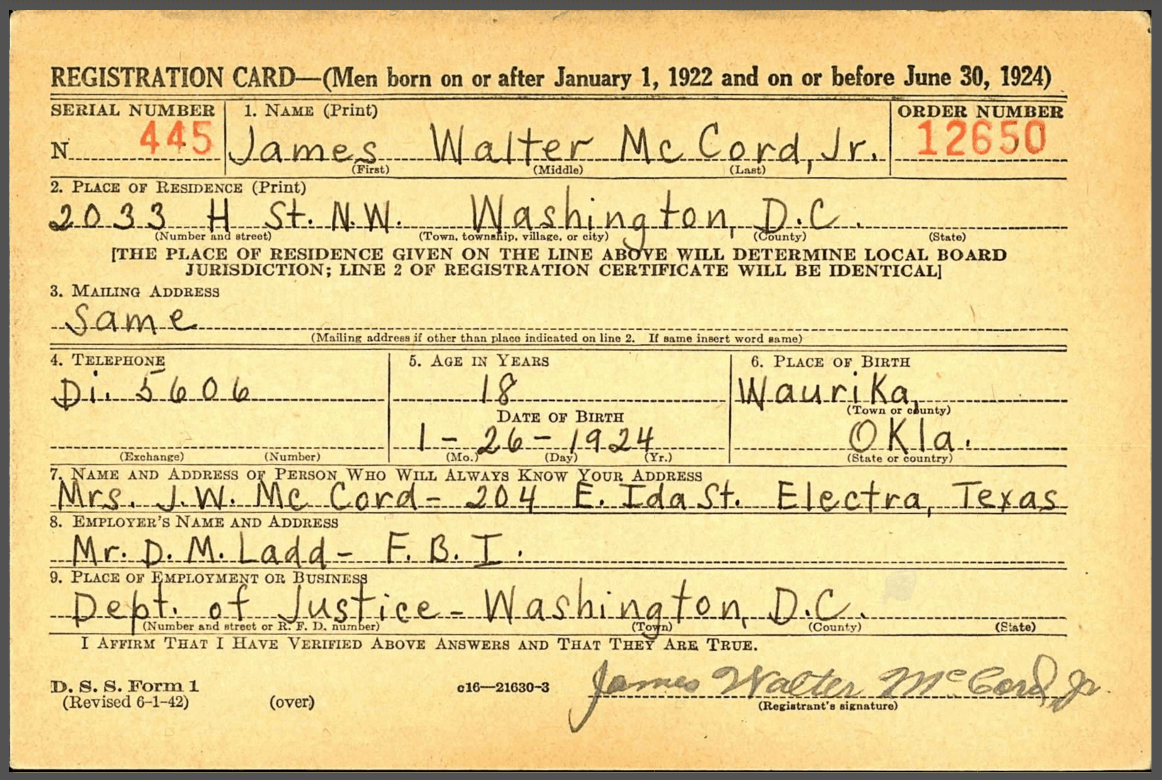

When Ellsberg returned, he went to work at Rand Corporation. This was a research and development company in Santa Monica. Robert McNamara was getting ready to leave office. One of his very last acts was to commission the secret study called the Pentagon Papers. Since Ellsberg had worked in the Pentagon, he was asked to work on the study. He then decided that the Pentagon Papers were so powerful in exposing the lies behind the war, he needed to get them into the public record. So he and his friend Anthony Russo decided to copy the study and make it public.

Since the Pentagon Papers were classified, Ellsberg and Russo faced legal problems if they themselves gave the documents to a newspaper or magazine for publication. Therefore, Ellsberg approached four elected officials to try and get them entered into the congressional record. That would have protected them legally since representatives and senators have immunity while speaking from the floor. The problem was that for one reason or another, all four refused to accept the documents. (Ellsberg, Secrets, pp. 323-30, 356-66)

Ellsberg got in contact with Sheehan, whom he had met in Vietnam in 1965. Ellsberg had a teaching fellowship at MIT at this time. So Sheehan drove up from New York to Cambridge in March of 1971. Ellsberg made a deal with Sheehan: he could take notes on the documents and copy a few pages. He could then show those notes to his editors and they could make up their minds if they would publish the actual papers. Ellsberg left Sheehan a key to the apartment where he had them stored. Without telling his source, Sheehan ended up copying the documents with his wife and taking them to New York. (Ellsberg, p. 175)

The Times did publish three days of stories from the papers before they were halted by a court order. What is interesting about this Times version of the Pentagon Papers––which was later issued as a book––is that it differs from the later edition previously mentioned. For Senator Mike Gravel did read from a portion of the documents on the senate floor. In his version, later published by Beacon Press, as noted above, there is an entire 40 page chapter entitled “Phased Withdrawal 1962-64”. In the Times version of the papers, the section dealing with the Kennedy administration goes on over 200 pages. (The Pentagon Papers, New York Times Company, 1971, pp. 132-344) There is, however, no section on the phased withdrawal, and the transition from John Kennedy to Lyndon Johnson concludes with the declaration that somehow, Johnson had affirmed Kennedy’s policy and continued with it. I cannot say that this was purposeful, since the Gravel edition of the papers is longer than the one the Times had. But whatever the reason, today that statement looks utterly ludicrous.

Everyone who reads this site is aware of the My Lai Massacre, which occurred in March of 1968. An army regiment slaughtered hundreds of innocent women and children at the small hamlet of My Lai. The incident was covered up within the military by many high level officers, including Colin Powell. But it finally broke into the press in 1969. It was an indication that the US military was disintegrating under the pressure of a war that could not be won.

The exposure of My Lai caused many other veterans to come forward and tell stories about other atrocities. In 1971, Mark Lane helped stage what was called the Winter Soldier Investigation. This was a three day event held in Detroit and broadcast by Pacifica Radio. There, many others told similar stories about what had really happened in Vietnam.

The Nixon administration was not at all pleased with the event. White House advisor Charles Colson, with the help of the FBI, went to work on discrediting the witnesses. (Mark Lane, Citizen Lane, p. 218) Since Lane helped with the event, he knew many of the men and interviewed them. He turned the interviews into a book called Conversations with Americans. Some of the veterans expressed fear of reprisal for what they told the author. So in the introduction, Lane explained that some names had been altered to protect the witnesses from the military. (Lane, p. 17) Lane then placed the actual transcripts with the real names at an attorney’s office in New York; a man who had worked for the Justice Department. (Citizen Lane, p. 219)

Six weeks after the book was released, the New York Times reviewed it. The reviewer was Sheehan. In cooperation with the Pentagon, Sheehan now said that a number of the witnesses were not genuine and Lane had somehow fabricated the interviews. (Citizen Lane, p. 220) Sheehan did this without calling the lawyer in New York who had the original depositions with the real names. It is hard to believe, but Sheehan did a publicity tour for his article. Yet he refused to take any of Lane’s personal calls or answer any of his letters. When Lane finally got to confront Sheehan on the radio, Sheehan said that in three years of covering the war in Vietnam he had never found any evidence of any such atrocities. When Lane asked him about My Lai, Sheehan said these were just rumors. (Citizen Lane, p. 221) Recall, this was very late in 1970 and in early 1971. The story had broken wide open in late 1969, including photos of the victims in Life magazine and the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

In his 2007 interview, Sheehan said he became disenchanted with the war in 1967. But as the reader can see from the above, he was still covering up for the military in 1971. One of the worst parts of the 2007 interview is when Sheehan talks about his tour in Indonesia in 1965 before returning to Vietnam. He says that this was an enlightening experience for him. Why? Because he says the communists had tried to take over the government, but they got no aid from Moscow or Bejing. He then adds that this showed him that communism was not a monolithic movement, and the domino theory was not really applicable.

What can one say about that statement? Besides him learning in 1965 what Kennedy knew in 1951, there is this: There was no communist insurrection in Jakarta in 1965. And any reporter worth his salt would have known that––certainly by 2007. General Suharto used that excuse to slaughter over 500,000 innocent civilians. But in keeping with this, A Bright Shining Lie was an establishment project. Peter Breastrup supplied the funds through the Woodrow Wilson Institute to finish the book. Breastrup worked for the Washington Post; he was Ben Bradlee’s reporter on Vietnam for years, and he always insisted that the Tet Offensive was really misinterpreted and blown out of proportion by the media. The book was edited by the infamous Bob Loomis at Random House. Loomis was the man who approached Gerald Posner to write Case Closed, a horrendous cover-up of President Kennedy’s assassination.

Since the war had turned out so badly, Sheehan could not really make Vann the hero he and Halberstam had in 1963-65. So they dirtied him up. His mother was a part-time prostitute, he cheated on his wife, and he was a womanizer in Vietnam who impregnated a young girl. This was supposed to be part of the lie about Vietnam. But Sheehan really never got over Vann, because in later interviews he said that it was really Vann who, at the Battle of Kontum, stopped the Easter Offensive. Which is a really incomprehensible statement. The tank/infantry assault on Saigon by Hanoi in 1972 lasted six months and was a three-pronged attack. It was finally stopped by Nixon’s Operation Linebacker, which was perhaps the heaviest bombing campaign in Vietnam until the Christmas bombing of 1972.

What Sheehan did––with his so-called inevitability of the war, disguising of Kennedy, his promotion of Vann, his misrepresentation of Mark Lane––is he helped promote a Lost Cause theory of Vietnam. This was later fully expressed by authors like Guenther Lewy in America in Vietnam, Norman Podhoretz in Why We Were in Vietnam, and more recently, Max Boot’s The Road Not Taken. The last pretty much states that Lansdale, Vann’s hero, should have been placed in charge. If so America likely would have won.

So excuse me if I will not be part of the commemoration of Sheehan’s career. In many ways, both he and Halberstam represented the worst aspects of the MSM. After being part of an epic tragedy, they then did all they could to promote a man who very few people would have ever heard of without them. At the same time, they did all they could to denigrate the president who was trying to avoid that epic tragedy.

That is not journalism. It is CYA. And it is CYA that conveniently fits in with an MSM agenda.

Listen to Jim DiEugenio being interviewed on this subject The Late Neil Sheehan, The New York Times, Vietnam, and Daniel Ellsberg Pt. 1 w/ Jim DiEugenio.

Listen to Jim Naureckas being interviewed on this subject The Late Neil Sheehan, The New York Times, Vietnam, and Daniel Ellsberg Pt. 2 w/ Jim Naureckas.

Jim Naureckas writes ACTION ALERT: What Can ‘Now Be Told’ by NYT About Pentagon Papers Isn’t Actually True.