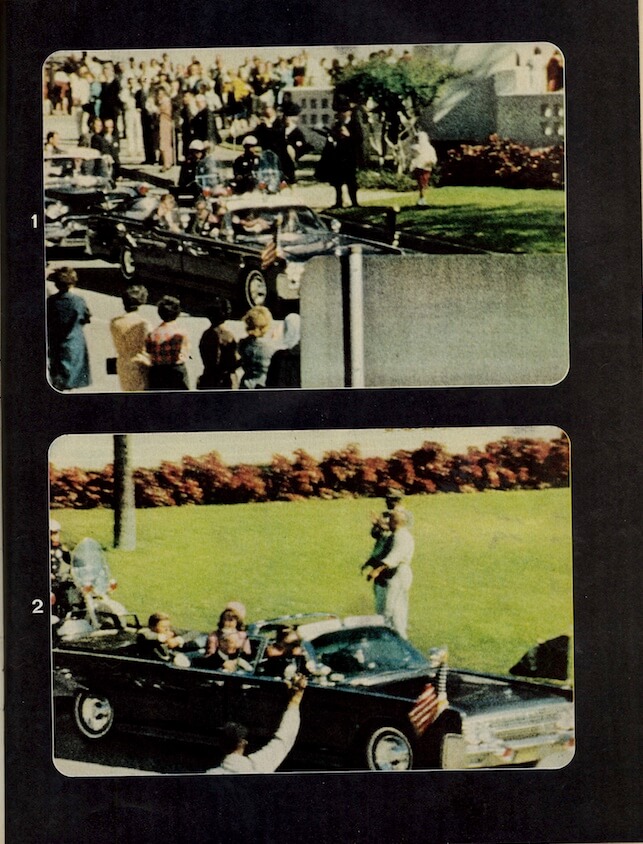

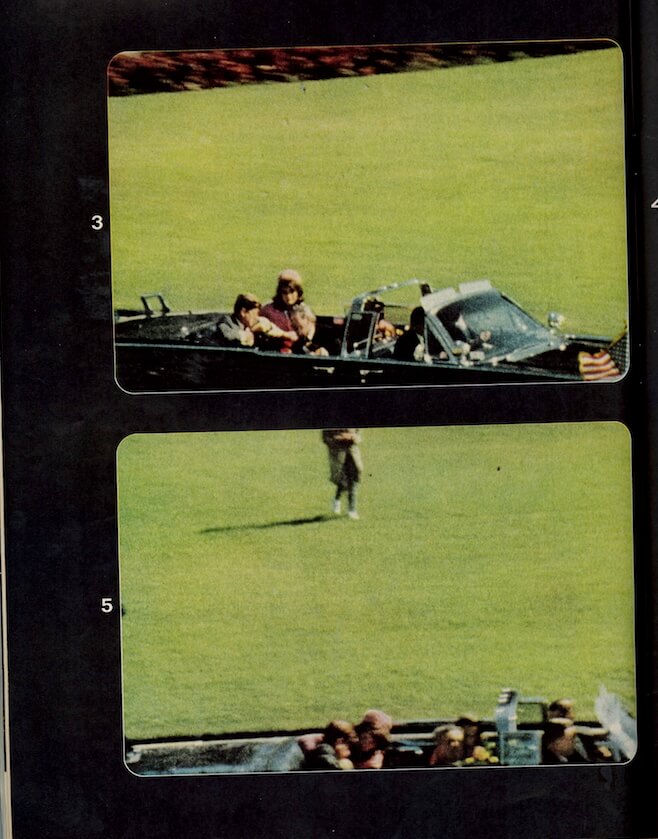

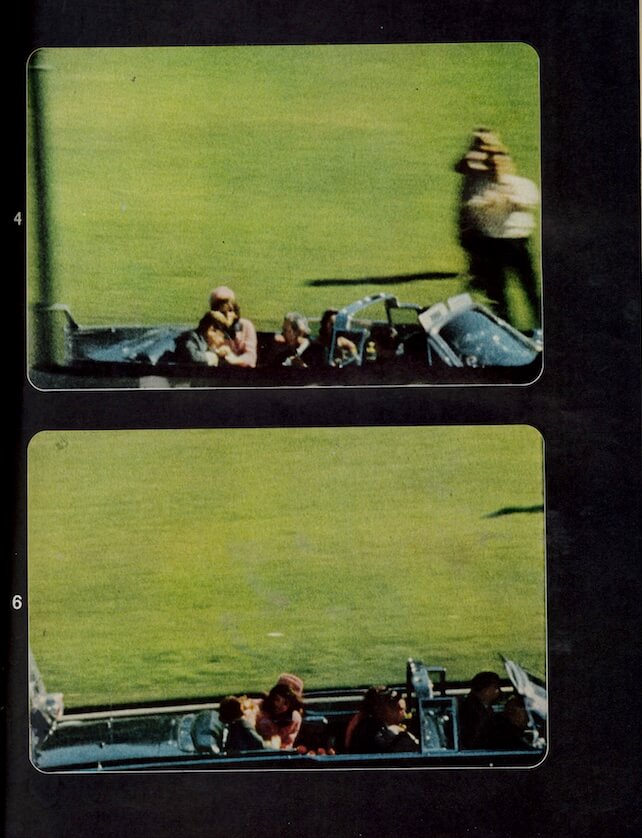

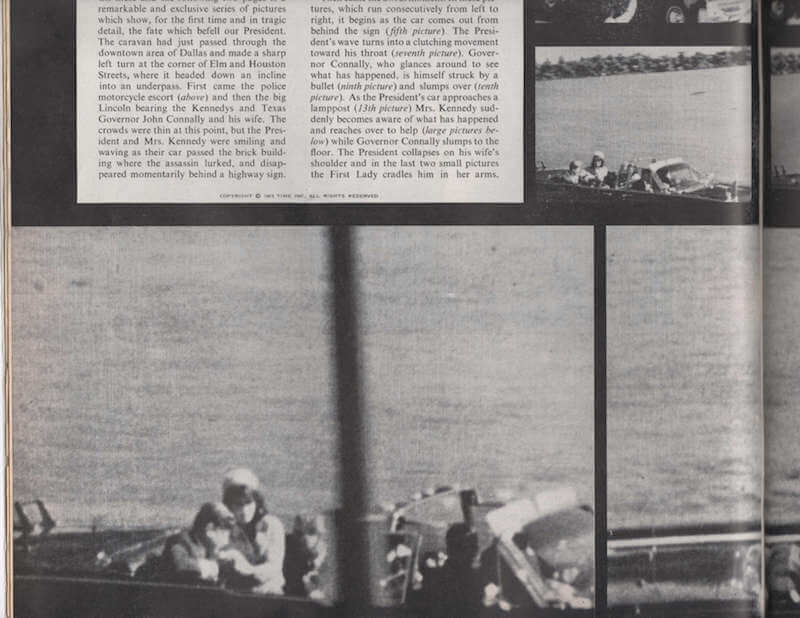

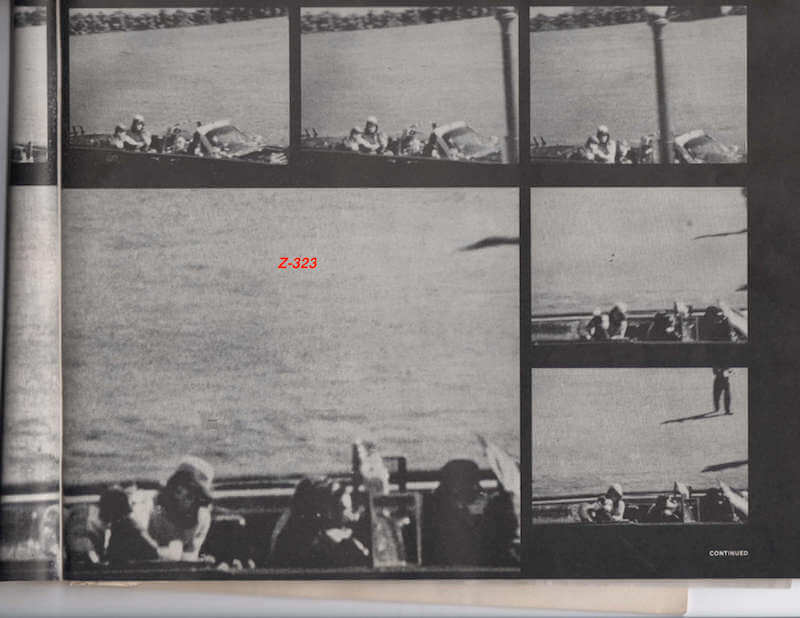

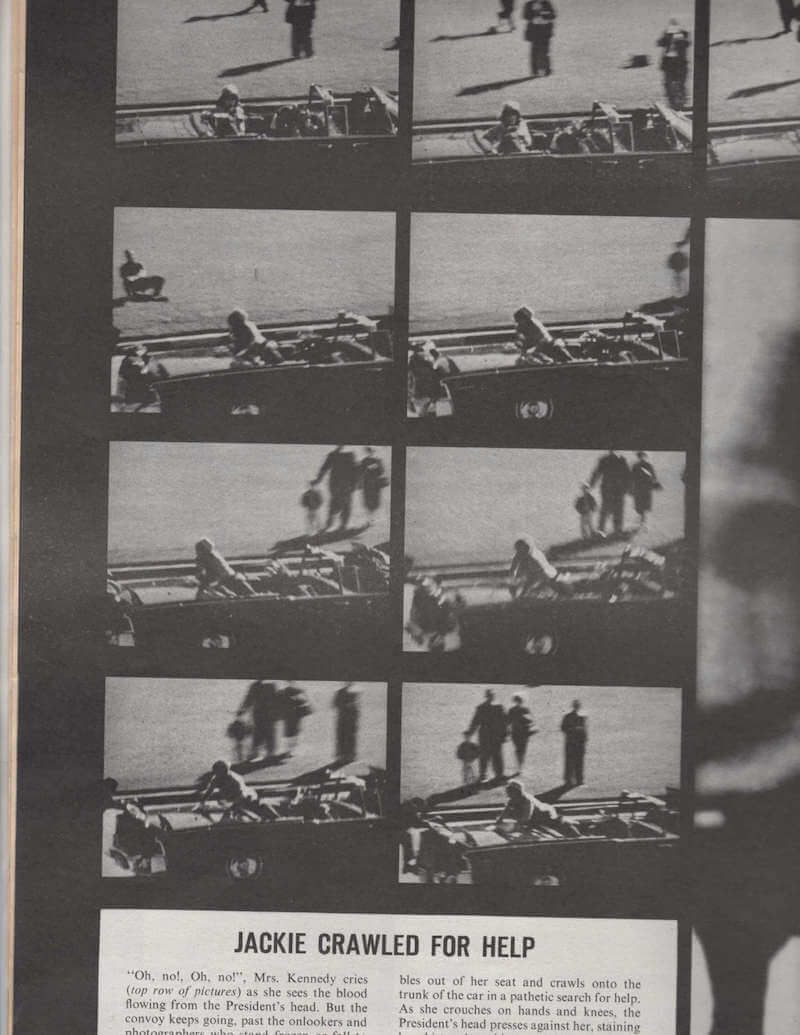

The first time I saw the Zapruder Film in its entirety was late 2010. Surfing the net in my flat in Istanbul, site of the 8-mile “Kennedy Avenue” running out to Atatürk Airport, I came across the video on YouTube. Immediately I felt I must have seen excerpts or stills before but never the whole thing, not even the 1975 Geraldo Rivera broadcast. There I was in a foreign land, watching a momentous event as a “newbie” in my mid-forties, gripped with shock-horror at the vision of a dashing US head of state publicly executed on a downtown American street. I stayed up long into the night hunting for assassination material, arriving weary at the law office in the morning.

Yet the primary emotion I felt on watching the Zapruder Film back then, much greater than shock or horror, was sadness. The vision of the President slammed backward and to his left like flotsam as his distraught wife attempts to retrieve debris from his shattered head is still among the saddest things I’ve ever seen. Of all the dehumanizing visions from history captured on film, somehow the moment of this man’s fatal wounding stands out even among tragedies encompassing many more victims at once. It resonates like a warning to all humanity never to get our hopes up too much.

*********

It was in the summer of 1999 that I made the acquaintance of Howard P. Willens, long before I knew who he was. Having recently received the news that I’d passed the bar exam, I needed a job for a couple of months, and as many have long done in Washington, I turned to a legal staffing agency, the name of which I now forget. One of the principals in this small, boutique firm said it would require me to work at the home of a senior, distinguished attorney and his wife, also a lawyer, helping them to finish research on a book they were jointly authoring.

The interviewer cautioned me diplomatically that, while this client was highly accomplished and respected, he could be “difficult at times,” or words to that effect. The substance of it was that Mr. Willens tended to be overly exacting in his demands, exhibiting impatience that might disconcert some. No problem, I said. I was confident any of this gentleman’s idiosyncrasies would roll off my cocky shoulders with ease. Besides, I reasoned, it was only for a few weeks.

That the next two months were among the most unpleasant of my professional life was not something I would normally have linked at the time to anything more than over-the-top fussiness on the part of the person I was trying – haplessly – to please. It was not a dull assignment overall, but Mr. Willens’ peculiar habit of becoming red-faced instantaneously, adopting a contemptuous tone of voice without ever raising it, was so effective in sending me into spirals of depression and disconsolation that eventually I couldn’t help but take it personally. No one, I thought, could be this disagreeable unless he had taken a serious, specific dislike to the person he was addressing.

Since I almost never sensed any satisfaction on his part, I became desperate for days spent alone at the Library of Congress, locating precise content for footnotes and citations. Howard Willens struck me as unambiguously unhappy, and once I discovered who he was, fourteen years later, I would link his unhappiness inextricably to the sadness wrought in my mind by the Zapruder Film.

I

The two books that Howard Willens and Deanne Siemer (his wife) produced, and on which I worked in their final stages, are serious-looking academic histories. National Security and Self-Determination: United States Policy in Micronesia (1961-72) (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2000) and An Honorable Accord: The Covenant Between the Northern Mariana Islands and the United States (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2002) tell an intricate story of law and diplomacy, how Washington handled Pacific territories that wound up under American control after World War Two.

Even within the confines of “authorized history,” the authors are not unsuccessful in recounting a tale of twentieth-century American manifest destiny with a “happy ending.” Years of negotiations and interim agreements are related in impressive detail, and, it could be argued, as authoritatively as anyone could. Willens and Siemer were personally instrumental in many of the processes they describe. Mindful that some observers might perceive the formal attachment of the islands to the US as just another form of imperialism – or annexation – their main purpose, as perhaps expected with any authorized history, is to demonstrate that this was never the case.

The authors cite National Security Action Memorandum 145, issued by President Kennedy in 1962, as encapsulating the guiding American principles for the political future of the Micronesian islands that ended up as a “Trust Territory” of the United Nations, with the US as “trustee.” JFK, sensitive to any colonialism on the part of the United States (or any other country for that matter), reflected that sensitivity in NSAM 145. As the authors note:

[President Kennedy] identified education as the first priority and directed his cabinet secretaries to create a task force chaired by [the Department of the] Interior, that would develop and implement programs to improve education in the Trust Territory and to address the serious shortcomings in public services and economic development. [An Honorable Accord, p. 10]

With NSAM 145, JFK transferred responsibility for the Northern Marianas to the Department of the Interior. Prior to 1962, all of the Trust Territory except Rota had been administered by the Department of the Navy, which wanted to maintain strict security controls, limiting outside access to the islands in a typically furtive military atmosphere. Kennedy opened the islands up to outside travel and trade, in his words, to “foster responsible political development, stimulate new economic activity, and enable the people of the Islands to participate fully in the world of today.” [Ibid.]

Disillusioned with the task force’s slow pace in implementing NSAM 145, JFK appointed an outside expert, Anthony Solomon, to lead a mission investigating prospects for accelerated economic and social development. The mission predictably advised greater US investment but also reported on a lack of political consciousness among the native inhabitants. In the Northern Marianas, they “found no serious opposition to permanent affiliation with the United States” and recommended a plebiscite for 1967 or 1968, offering voters two choices: independence or US sovereignty. [Ibid, p. 11] JFK knew that the islanders had already experienced three colonial regimes – Spanish, German, and Japanese – and he wanted US administration to represent genuine emancipation.

Balancing the goals of self-determination and non-fragmentation became a serious initial challenge for Washington in determining Micronesia’s destiny. The governments of Guam and the Caroline Islands, for example, initially rejected any arrangement that would make their people US citizens, while the Northern Marianas favored association with the US. The US government thus negotiated separately with the de facto indigenous authorities of the Northern Marianas to achieve a separate status for them. Guam would eventually become a US territory as well, and Guamanians US citizens.

The authors touch on how, in the aftermath of JFK’s assassination, the culture of official secrecy and the national-security state took over the process of establishing the island chain’s political status:

[T]here no longer was the level of presidential interest that demanded the attention of the National Security Council staff and the secretaries of interior, defense, and state. In December 1963 the National Security Council, at the request of State (without any consultation with Solomon), classified as Secret the first volume of the report dealing with its political findings and recommendations; it remained undisclosed officially for many years. [Ibid. p. 12-13]

II

In 1972, the Marianas Political Status Commission (MPSC) retained Willens as counsel, by which point the Pentagon had become more assertive about how much of the islands would be retained for basing and other military purposes. The Nixon administration began planning a vast increase in defense sector involvement, including acquisition of 27,000 acres and the entire island of Tinian. Washington became alarmed when a popular referendum was organized in the Northern Marianas on the issue of relocating a whole village to accommodate a new US military base. The US government informed the Northern Marianas authorities that it would not be bound by the results of such a poll, and it was reassured that the referendum’s results would not be dispositive.

It took until the mid-1970s, with former Warren Commission member Gerald Ford as US president, for the Northern Marianas to finally formalize the status its representatives said they wanted. This was the “Covenant.” One can argue over how rosy and bucolic the US-administered Northern Marianas became as a result of a process involving the national-security state, but I never had too much trouble believing association with the United States was a more genuinely popular alternative at the time than independence, a scenario that may well have seemed highly daunting. Protection from “Big Brother” America may have been too enticing for a tiny island population to pass up.

The history of the political status of Micronesia is a unique tale, intriguing for anyone interested in international law. While subject to sanitization in the volumes of Willens and Siemer, there are occasional human touches (in one anecdote, an American lawyer and economist for the MPSC drunkenly assaults a US Air Force colonel who has insulted him in a hotel bar). That said, An Honorable Accord and National Security and Self-Determination are conservative histories.

A “progressive” analysis of the legacy of covenants between the US and Micronesia might focus on factors such as economic exploitation, corruption, clan-based patrimonialism, and a poor defense of workers’ rights, in addition to the adverse role and influence of the US national-security state in engineering political outcomes desired by Washington (the publisher of the first volume, Praeger, has a long history of CIA-commissioned works). Also, while the Northern Marianas and Guam are part of the United States, their residents have no voting representation in the US Congress, a dubious status shared with compatriots in American Samoa, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and the District of Columbia. No official US history is likely to highlight such concerns at great length.

As recently as 2019, Ms. Magazine published an update to Rebecca Clarren’s 2006 article entitled “Paradise Lost,” highlighting social degradation in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) since the accord with the United States. The purpose of republication was, apparently, to double down on her central points in the face of a Saipan Tribune piece, “Article ignores the great strides we’ve made,” attacking Clarren’s analysis. As Clarren noted:

[In 1975] the islands’ indigenous population of subsistence farmers and fishermen voted to become a commonwealth of the United States – a legal designation that made them U.S. citizens and subject to most U.S. laws. There were two critical exceptions, however: The U.S. agreed to exempt the islands from the minimum-wage requirements of the Fair Labor Standards Act (allowing the islands to set their own lower minimum wage, currently $3.05, compared to $5.15 in the U.S.) and from most provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act. This has allowed garment manufacturers to import thousands of foreign contract guest workers who, ironically, stitch onto the garments they make the labels “Made in Saipan (USA),” “Made in Northern Marianas (USA)” or simply “Made in USA.”

Former heavyweight DC lobbyist Jack Abramoff, prior to his conviction and imprisonment for fraud, bribery, and tax evasion, served as a lobbyist for the CNMI and blocked bipartisan reforms advanced by Congress to improve labor conditions and immigration abuses. As Clarren pointed out:

In January 2005, the GATT treaty, which had regulated all global trade in textiles and apparel since 1974, expired, eliminating quotas on textile exports to the U.S. The Northern Marianas had been attractive to garment makers because of its exemption from such quotas and from tariffs on goods shipped to the U.S. marketplace. Without those advantages, manufacturers are increasingly moving to such places as China, Vietnam and Cambodia, where they can pay even lower wages. Since the treaty’s expiration, seven factories have closed in Saipan, reducing the value of garment exports to half its 1999 peak and putting thousands of guest workers out of jobs. Some observers expect almost all factories to close by 2008, when a temporary restriction on Chinese apparel exports to the U.S. ends.

Given their alternatives, the people of the Northern Marianas could very well have legitimately voted decades ago to become a part of the US, a choice President Kennedy’s NSAM 145 extended to them and – as the authors tell it – the option favored by JFK. One might argue that such grim social developments are ever-present in any process of this kind, that the plunge into social tragedy was inevitable. It’s just that one can’t help but suspect that the Kennedy administration, had it lived, might have put the vulnerable people of Micronesia on a superior social and economic footing.

III

Though I never had any contact with Howard Willens or Deanne Siemer again, I hoped they felt I had made a reputable contribution to their authoritative history, that their acknowledgment was more than just politeness. On my last day, I remember sitting next to Willens outside – near the pool behind his attractive, fully detached home in a leafy neighborhood off the Rock Creek Parkway. I seem to recall his small grandchildren were visiting, playing in the background, and it was the first time I felt any sense of relaxation around him. Maybe he was looking forward to me leaving, or maybe he was simply “exhaling” after the laborious, nerve-wracking process of dotting all the i’s and crossing all the t’s in his upcoming tomes. But he was a significantly (if slightly) changed man, and at that point, finally, I no longer took his unfriendliness personally. (As I am duly mentioned in the acknowledgments among seven other research assistants, it occurred to me that others may have quit). He was around family, congenial, talking to me about what I wanted to do.

As it happened, I was due to travel to the Caucasus region of the ex-USSR in a matter of days. Earlier in the year, my British colleagues and I had monitored an election in Armenia in which the US-sponsored political party – “Unity” – won big. We had found the “Unity” victory deeply flawed, and when the leaders of this new ruling faction were massacred in the parliament chamber in late October by nationalist gunmen claiming they only wanted the “people” to “live well,” US Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott squirmed in public while expressing outrage at the slaughter of the Armenian politicians whom he and his Washington superiors had so enthusiastically backed. “Unity” had been amenable to compromise on the disputed, Armenian-controlled territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, something Washington desperately wanted settled to allow oil to flow more smoothly to the west from Azerbaijan, which claimed Nagorno-Karabakh as its own.

In neighboring Georgia, President Eduard Shevardnadze – long a favorite of the US foreign policy establishment and winner of the “Enron Prize” in 1999 – was facing a stiff challenge from a regional leader in parliamentary elections at the end of October. In the pre-election period, Shevardnadze would bring out US-supplied helicopters to fly low over the capital, Tbilisi, in a deafening alert to his subjects that a “coup attempt” was under way. The putsch, declared Shevardnadze, was being orchestrated by the Russia-friendly head of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, Aslan Abashidze, whom Western media consistently labeled a “warlord.” The US staunchly backed Shevardnadze in his electoral showdown with Abashidze, whose bloc was polling high.

Within three years, Washington would turn against Shevardnadze after a poor evaluation of local elections in 2002, and by November 2003 the US would call for his ouster in the “Rose Revolution.” Abashidze would flee to Moscow within six months of the “revolution,” and top US officials like Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld would celebrate a new generation of Georgian leaders as the US-led war in Iraq ramped up. By 2008, around the time of the five-day war with Russia over the separatist enclave of South Ossetia, Sen. John McCain would dance a “Georgian jig” on camera with US-backed strongman President Mikheil Saakashvili, a Shevardnadze protégé now transformed into the great hope for change in place of the stagnant old ways of the ex-Soviet Politburo member.

All of this seemed far more exciting to me at the time than the history of Micronesia. Anticipating my impending mission on behalf of democracy and human rights, as I understood them then, I might have been distracted from my assignment. If so, I apologize herewith to the authors. I did try to be precise in my source-checking. In any case, in September 1999, Howard Willens and Deanne Siemer bid me semi-cheerful farewell and good luck as I drove out of their company forever.

IV

It was not until the year of the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination that I became aware I had once worked for a former member of the Warren Commission’s legal staff. Howard Willens had just published a book, History Will Prove Us Right (New York: The Overlook Press, 2013), to uphold and defend the Warren Report’s conclusions, and he and other surviving legal counsel appeared in panels to promote and celebrate the Warren Commission’s achievement in securing truth and justice for the people of the United States. By then convinced that the Commission had done nothing of the sort, I found it a dreadful spectacle to watch.

What I felt most when watching Willens in 2013 was the old, familiar sense of his discontent. In a speech at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, he was animated, occasionally agitated in his broad-shouldered suit, clutching the lectern like a commissar laying down the law. But the stuttering “uhs” and “ahs” sounded symptomatic of over-rehearsal. Explaining the Single Bullet Theory as if it were fact, he looked to me not only despondent but also somewhat worried or under duress.

At the 27:43 mark in the C-SPAN video, Willens can be seen and heard reciting the following:

“So Single Bullet Theory of course has gone through the ages as a much, uh, uh, maligned, uh… uh, uh, uh, uh, lil’ shorthand for, uh, the Commission’s, uh, conclusion, which of course, it became a conclusion of fact, uh, uh, not… a theory, uh, because after a, a reenactment in-in Dallas in May of 1964, it seemed very evident that the bodies of the President and the Governor were, uh, positioned in the car in such a way… uh, that, that the bullet after it exited from the President… would, would hit the [sic] Connally and cause… the nature of the wounds… in-in his back, his-his-his wrist, and his thigh… that was uh, uh, uh, what he suffered. So it was… and furthermore, what people tend to forget is that the… uh… the… uh, uh, pathologists… and the Commission were not the only people that reached, uh, this view, that this particular conclusion was reviewed in 1968, experts in 1975, experts in 1976, and again in 1978. And out of twenty experts… twenty… let’s be precise… twenty-one… pathologists… experts… in such matters examined the autopsy, uh… photographs and x-rays… they all, they all, all concluded, uh, the course of the bullet… and, uh, twenty out of twenty-one… concluded as did the Commission… that a single bullet… created the back, throat wounds of the President and the wounds suffered by Governor Connally. The dissenting pathologist, who will be in town two weeks from now featured at a conference, when asked what happened to the bullet, when it exited the President’s… throat, he said: ‘I don’t know.’ [Pause, feint audience titters] ‘I didn’t conduct the investigation.’ And unless one has a rational explanation… that, that can rival in terms consistent with the law of physics, and with the physical evidence available… I think there’s not a rational discussion that can be had… on the question of the Single Bullet uck-uck-uck conclusion.”

The “dissenting pathologist” was, of course, Dr. Cyril H. Wecht, M.D., a member of the House Select Committee on Assassinations forensic panel and a distinguished university professor, who also had a law degree. Having listened to both men speak, I had little doubt which of the two I would prefer to represent me in a jury trial or testify as a witness. Of course, since there was never any genuine trial of Lee Harvey Oswald, the point was moot, but how dispiriting to see a fellow attorney such as Howard Willens – even as he referred to overwhelming majorities of “experts” in the 1960s and 1970s – nonchalantly cast aside the fact that the only “majority” that mattered when determining truth under US criminal law was a majority of jurors.

In History Will Prove Us Right, Willens fleshes out Dr. Wecht’s “I don’t know” quotation by noting its setting: the mock trial of Lee Harvey Oswald in London in 1984, with Vincent Bugliosi as mock prosecutor. (Unsurprisingly, Bugliosi’s is the top review on the back of the book’s dustjacket.) But what makes the entire issue of the fate of the “Magic Bullet” so remarkable as a subject of Willens’ ridicule of Wecht is that both Willens and Bugliosi ignored the broken evidentiary chain. The same was true for President Kennedy’s body and limousine. Both were removed from Texas illegally, since the crime scene investigation and autopsy should have taken place in Dallas in accordance with prevailing law, and in a bit of forensic negligence best described as outrageous, Kennedy’s wounds were never even dissected. The presidential car was taken from Andrews Air Force Base to the White House garage, where even FBI investigators were denied access to it until after midnight.

In short, whisking both corpse and vehicle out of sight of the duly constituted law enforcement authorities destroyed due process. Yet it is Dr. Wecht who is mocked? It is Willens and Bugliosi who should be derided as attorneys. Not only was Wecht speaking the truth, but it was precisely that truth – the “I don’t know” – that made bunk out of all Willens’ and Bugliosi’s so-called “evidence.” It is inconceivable that an attorney of Willens’ stature could accept this state of affairs as evidentiarily sound. It is insulting that he could expect the rest of us to do so.

Again, Willens’ swagger in 2013 could not negate the deep-seated sense of dissatisfaction I had perceived in him in 1999, and it wasn’t just the stutter. Something still wasn’t right with the world, and as I watched I became aware of a strange “camaraderie” among the ex-Warren Commission lawyers, a “brotherhood” – not so much of joy as “circumstance.” It was as if someone (or something) had dragged these octogenarians out of retirement to go on a tiresome “national tour.” It was like a tedious exercise in going through the motions, but, hey, at least they had each other.

At the 29:42 mark, Willens can be seen and heard reciting the following:

Uh, we, we did have the problem, as you know, of dealing with, uh, conspiracy, uh… and the problem that sure you’ll hear about more from my colleagues, but the over… uh… whelming problem from the outset was that it is always impossible, analytically, to prove a negative. And here the task was to prove there was no conspiracy.

The “task” was to prove there was no conspiracy? Since when did that become the duty of a diligent lawyer or investigator serious about his job? What happened to the truth?

He continues:

Now, the Commission was aware then… of all the possible, uh, interests, here in Texas, and nationally and internationally, who might have an interest in assassinating the President. But in order to prove a conspiracy, you have to prove there’s some rel… some relationship between the alleged conspirators and the people who actually… did the deed, whether it’s Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby. And the Commission staff and the members of the Commission conducted… a widespread investigation looking at the associations of both these individuals, intensely and comprehensively, and could not find any evidence that either of them had been aided in any way by one of the alleged, uh, suspects… [unintelligible]. And so, ah, ah, that, of course is a conclusion that one can never be… absolutely certain about, and what the Commission did in its findings was say, was to say, ‘We have found no credible evidence… of a conspiracy.’ They did not say there was no conspiracy. And they fully understood that with the decades to come, there might be additional evidence that would, uh, uh, persuade, uh, uh, impartial, knowledgeable people that there was a conspiracy. It’s been forty-nine years, and that evidence still has not materialized. And if I had had the courage of my convictions, the book would be entitled, ‘History Has Proved Us Right’ rather than ‘History Will… uh, uh, uh… Prove Us Right.’”

Howard Willens has seen the inside of a courtroom many more times than I, and he no doubt received a much higher grade in evidence to boot. But to point out to your audience that, on the one hand, the Commission used the term “no credible evidence” as a way of qualifying the veracity of its findings, and then, on the other, say that no evidence had materialized in the previous half-century to undermine the Commission’s conclusion beggars belief. It’s akin to arguing with non-lawyer Warrenites online and being bombarded with: “You have no evidence!” You’re left with the option of either cutting the discussion off abruptly or trying to calmly reason with them that, indeed, there is a ton of “evidence.” It’s just a matter of whether one interprets it as “credible” or not.

At the risk of digression, for example, Helen Markham stated in a sworn affidavit that she arrived at the intersection of East 10th Street and North Patton Avenue in Dallas at 1:06 PM on November 22, 1963, and immediately caught sight of Officer J. D. Tippit’s killer. A sworn affidavit is evidence, as any lawyer worth his or her salt will tell you. In a court of law, you can be certain any diligent defense attorney would not only have entered it into evidence but also held onto it like a pit bull with a fresh bone. Markham’s route to the bus stop was part of her daily routine, making her affidavit more credible than anything else she said. It rendered the accused killer’s arrival at the scene of Tippit’s slaying impossible, and a court of law would have taken due note of that. But the Warren Commission was not a court of law, so it ignored the evidentiary weight of the affidavit. It never proved anything because it didn’t have to. In 2013, Willens blurred the definition of “evidence” as a way of bolstering the hackneyed Warrenite stance.

The phrase “courage of my convictions” also stands out as curious. If Willens had been brave enough to do the right thing, he would have called his book something else? One has to wonder whether such a statement betrays a sinister truth. Suppose, for instance, that Willens believed the Commission was “right,” as in the book’s title, but not “true.” What if leading Commissioners knew they were perpetrating a massive falsehood for the “right” reasons, because the American public didn’t need to know the truth, or worse (to paraphrase Jack Nicholson’s caricatured Marine colonel in A Few Good Men), couldn’t “handle the truth”? Personally, I suspect certain Commission insiders beyond Allen Dulles (including a few legal staffers) knew some terrible – even unspeakable – secret but set about constructing a fairy-tale narrative to “tranquilize the people.” This is how Senator Richard Schweiker of the Church Committee referred to the Commission. Could Willens have been one of them? Surely not, I hoped as I watched him in 2013.

History Will Prove Us Right has been ably reviewed on this website, and I don’t feel a need to elaborate on that analysis. But I do think Willens’ Micronesia works qualify as “serious” (if formalistic) academic history, whatever one’s personal perspective on the fate of the Trust Territories. History Will Prove Us Right does not, and no serious scholar would say otherwise. One might speculate Willens was happier writing the Micronesian volumes than he was writing History Will Prove Us Right, but with the benefit of hindsight, I sadly cannot shake the impression that Willens, as he wrote his Micronesia works, was still carrying something abominable around with him decades after serving as a Warren Commission attorney. That is, the unhappiness endured then, as it may still.

The manner of Howard P. Willens, Esq., struck me as severely unnatural not only in 1999, but forever thereafter in my mind’s eye. Something, I believe now, was desperately bothering him thirty-five years after the publication of the Warren Report, and the unpleasantness of that late summer in Washington was, I still feel, a consequence of that something. The enduring sadness of the assassination was described by John Newman in his seminal work, Oswald and the CIA, as an “unhealed wound.” That was the first place I saw it thus described, and that is still the most eloquent phrase I’ve heard as metaphor for that horrific event. But if the wound remains unhealed for a nation, how must it feel for any single individual still harboring some terrible truth about it?

Again, as the title of his book indicates, Howard Willens may have convinced himself that posterity would honor the men of the Warren Commission and its staff. He may have rationalized somehow that, in the event this truth became public in their lifetime, the public would understand that he and his colleagues were only trying to be upstanding, to prevent a widespread loss of faith in our institutions of government, with potential resultant chaos and collapse. While this makes some sense, it is at the same time unthinkable to me that anyone could carry something as profoundly awful as that around with them to the end of his life. Yet countless others surely already have.

The single sentence in History Will Prove Us Right about a phone call that Willens’ former Warren Commission colleague David Slawson received from James Jesus Angleton, ex-chief of the CIA’s Counterintelligence Staff, in 1975 (Angleton was no longer even a CIA employee) reads as follows:

When CIA Counterintelligence chief James Angleton called David Slawson to check his reactions to the Church Committee’s disclosures, Slawson frankly told Angleton how disappointed he was with his agency’s failure to disclose this vital information, but assured him that Slawson would honor his commitment to preserve the confidentiality of other CIA secrets. [p. 317]

This is a level of sanitization unequaled even in the Micronesian works. One wonders what Slawson himself thought of it. As the incident is recounted by David Talbot in The Devil’s Chessboard,

In a frank interview with The New York Times in February 1975, Slawson suggested that the CIA had withheld important information from the Warren Commission, and he endorsed the growing campaign to reopen the Kennedy investigation. Slawson was the first Warren Commission attorney to publicly question whether the panel had been misled by the CIA and FBI (he would later be joined by Rankin himself) – and the new story caused a stir in Washington. Several days after the article ran, Slawson – who by then was teaching law at the University of Southern California – got a disturbing phone call from James Angleton. After some initial pleasantries, the spook got around to business. He wanted Slawson to know that he was friendly with the president of USC, and he wanted to make sure that Slawson was going to “remain a friend” of the CIA. [Talbot, 580-81]

In the 1990s, Slawson infamously refused to answer an Assassination Records Review Board member who asked him whether he had listened to a tape recording supposedly made of Lee Harvey Oswald in Mexico City (Willens incidentally accompanied him on the trip to Mexico in 1964), remarking defiantly that he was “not at liberty to discuss that.” A federal statute passed unanimously by Congress in 1992 was supposed to afford Slawson just such a “liberty,” of course, but maybe the Ghost of Jim Angleton was still staring at him from somewhere in the room as he spoke.

President Trump reportedly told Judge Andrew Napolitano over the phone that he had seen something in the remaining JFK files that Napolitano, had he also viewed them, would have understood required continued concealment. If Trump was speaking the truth (not a given), then perhaps there is a small community of Americans prepared to walk around harboring some unspeakably atrocious fact about our government and history, and they are fine with just continuing to carry on that way until the end of their days. I don’t get it, but then I’m not one of them.

Recent breakthroughs in JFK research, including the watershed work of Jefferson Morley and the Mary Ferrell Foundation in pursuing still-concealed government files related to the assassination, offer hope that an era of great sadness and anguish in American history and life might finally come to an end. Looking back at the period of the Warren Commission and the ensuing several decades, one gains an unmistakable impression of widespread blackmail and intimidation holding sway over public officials, including those staffing official investigative panels. We know for instance, through Hale Boggs’ son Tommy, that J. Edgar Hoover maintained files on the Warren Commissioners. Well-meaning investigators operating in that milieu nearly sixty years ago no doubt experienced acute discomfort.

The political culture of Angleton and J. Edgar Hoover endured long after their deaths, so that honorable men such as Cyril Wecht found themselves alone in opposing something as grotesquely insulting to human intelligence as the Single Bullet Theory. Unseen pressure and intimidation on those seeking the truth must have been very real, and a recent two-volume set, One Nation Under Blackmail: The sordid union between Intelligence and Organized Crime that gave rise to Jeffrey Epstein by Whitney Webb (Walterville, OR: Trine Day, 2022), while lamentably neglecting to touch on the potential for blackmail in steering the course of investigations into JFK’s murder, has made waves for publicizing what many have long felt but were no doubt afraid to say. The truth is slowly coming into view, whatever those protecting an old secret may still hope to hide. The nation is progressing into light.

I cannot assume Howard Willens is among those hiding ghastly secrets about the nature of the assassination. It is of course possible that he genuinely believes in the Warren Report’s conclusions. After all, the notion that something was “possible” – however implausible – remains the primary debating stance of Warrenites in defending their bible today. But in the event Willens or any other living American encountered the sort of gangster-like tactics employed by Angleton against Slawson (or by Hoover against innumerable others), they would honor history and nation by unburdening themselves of that cloud of sorrow now. They should let America know of any torment experienced or learned of at the hands of the long dead “wise men” of America’s Cold War intelligence and security agencies. Real US “national security” demands freedom from that miserable past.