In the vast collection of JFKA literature and research, some of the simple truths have been buried, including veracities that refute that a lone gunman armed with single-shot rifle could have inflicted all the wounds, or fired as quickly, as seen Nov. 22 in Dallas.

So, let us ponder anew the shirts worn that fateful day in Texas by President John F. Kennedy and Governor John B. Connally and then observations of Connally’s attending surgeon, Dr. Robert Shaw.

And as we review, the tumbling single magic-bullet theory will die.

First, consider the Texas State Libraries and Archives Commission. Though little noticed even in the JFKA community, back in 2013, the commission featured a display of John Connally’s suit and clothes worn on Nov. 22, and prepared an online photo exhibit.

And here is the photo of Connally’s shirt with a bullet hole in the back, described as 3/8ths by 3/8ths of an inch, and possibly torn along the thread lines adjacent to the spot where the bullet entered. More on the thread lines later.

Of course, right away there is a problem—the Mannlicher-Carcano 6.5 rifle fires a large slug, actually 6.77 millimeters in diameter, or a little more than 1/4 inch in diameter and 1 and 1/4 inch in length.

That size of the Mannlicher-Carcano slug, manufactured by Western ammo, means that the resulting hole in Connally’s shirt was but 1/8th of an inch larger than the diameter of the slug, or a mere 1/16th of an inch on all four sides, assuming the slug was centered in the hole.

If the magic bullet that struck Connally was tumbling, that is, hit Connally sideways rather than nose-on, how did it make such a small hole, as in 3/8ths of an inch square? And not a hole 1 and 1/4 inch long?

Yet here is a depiction by researcher John Lattimer, positing the path and yaw of the “tumbling” bullet:

But with the re-introduced evidence of Connally’s long-forgotten shirt, it is plainly impossible that the tumbling magic-bullet struck Connally sideways.

(There are additional complications with Connally’s shirt, but all of which point to an even smaller original hole. The straight edges on the top and bottom of the bullet hole in Connally’s shirt may be the result of fabric removed for testing. Unbelievably, Connally’s shirt and other clothes were sent to a cleaning service directly from Parkland. The FBI indicated it was not able to find metallic traces around the bullet hole, due to the cleaning. It is not clear whether the FBI removed cloth from near the bullet hole, as they did with a hole in JFK’s shirt. In any event, the FBI lab work would have only enlarged the final hole in Connally’s shirt.

Oddly, the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) chose to describe the Connally shirt rear bullet hole as “1.3 centimeters (1/2 inch) in transverse diameter.” Transverse diameter meaning diagonally—and those who remember Pythagoras Theorem can compute that 1/2 inch is a diagonal of a square about 3/8ths by 3/8ths inch. It appears the HSCA was trying to make the Connally shirt hole, already possibly artificially enlarged by the FBI lab, as large as possible, in its report.)

Also, in the evidence of the shirt President John F. Kennedy wore in the motorcade, the single-magic-bullet theorists posit JFK was actually leaning a bit forward when struck from behind, meaning that the shot from sixth-floor of the Texas School Book Depository struck him cleanly and nearly at a right angle to his body.

But here is JFK’s shirt from that day:

We quickly see a puzzle. The bullet hole in JFK’s shirt is about the same size as the hole in Connally’s shirt. Yet, there is also some uncertainty about this hole in JFK’s shirt. As stated, the squarish cuts on the top end of the hole also may have been made by FBI lab technicians removing cloth to be examined for metallic traces.

There is a second image of JFK’s shirt, curiously showing an even larger, seemingly double hole.

There are additional fudge-factors in the Connally shirt, such as possible wrinkles or bunches in material at moment of impact, but all of which would have made the resulting hole larger, rather than smaller.

In any event, the rear hole in Connally’s does not indicate a sideways hit by a 1 and 1/4-inch long tumbling bullet and is similarly sized as the hole in JFK’s shirt.

But there is more.

Dr. Robert Shaw

Dr. Robert Shaw was the surgeon who attended to the injured Connally on Nov. 22 at Parkland Hospital, and the Governor was immensely lucky in that regard.

Not only did Shaw have superb credentials—a veteran practicing physician, a professor at the University of Texas—but during Shaw’s WWII service he had personally worked as a surgeon on more than 900 wartime patients who had suffered bullet and shrapnel wounds.

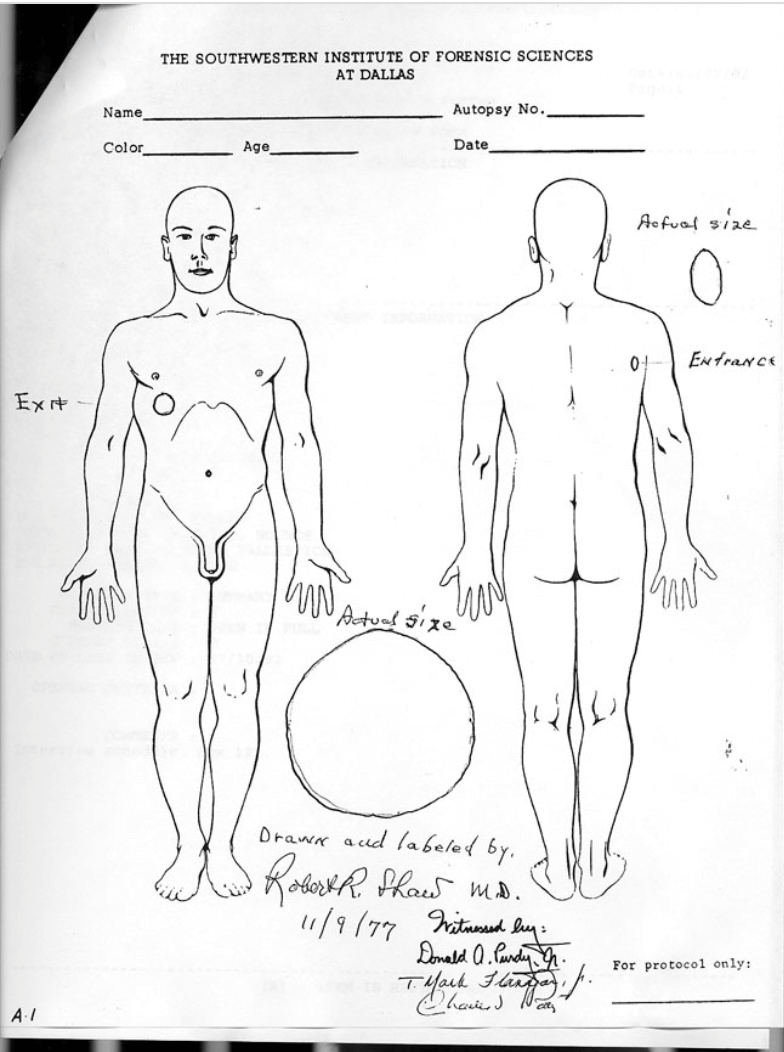

Dr. Shaw, upon viewing Connally, “found that there was a small wound of entrance (in Connally’s back), roughly elliptical in shape, and approximately a centimeter and a half (5/8th of an inch) in its longest diameter.”

Connally’s elliptical or oval wound, below his right shoulder, was 5/8ths of an inch along its vertical axis, that is, aligned with Connally’s body or pointing “north-south,” so to speak.

The vertical elliptical or oval shape of the original wound is a tell, close to conclusive.

From PathoilogyOutlines.com, in an article entirely unrelated to the JFKA: “Oval shape: suggests an acute angle of fire with respect to the skin.”

A clean non-tumbling shot, entering Connally’s back from behind and above, such as from the Texas School Book Depository or the Dal-Tex building roof, would leave a vertical elliptical shape, which is precisely the original wound that Connally had.

The length of ellipse would vary, depending on whether Connally was leaning forward or back at the moment of impact. Connally was almost certainly leaning back, as will be explained later, which would tend to lengthen the resulting elliptical wound.

In contrast, a tumbling slug might make a ragged hole, as when the bullet’s butt-end struck the body sideways. Such a hole could be largely sideways to the body, or at a three-quarter angle, or oddly shaped in 100 different ways.

In his testimony to the Warren Commission (WC), and to the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA), Shaw said he thought the rear entrance wound on Connally likely resulted from an unobstructed shot from above, a conclusion bolstered upon his review of the Zapruder film and discussion with the Governor.

Here is Dr. Shaw’s sketch indicating the vertical, elliptical shape of Connally’s wound—that is, up and down, not horizontal.

There are other indications that Connally was struck by a non-tumbling bullet. For example, Shaw told the HSCA in 1977 that “there was a tunnel made by the missile in passing through (Connally’s) chest wall.”

A “tunnel?” Do tumbling bullets make “tunnels”? Yes they do, but according to Dr. Shaw that is not what happened in this case.

Connally’s Coat

But there is even more and Shaw was almost certainly correct in his assessment of the wound, for we have a photo Connally’s jacket from Nov. 22 featuring the exit hole the bullet made.

And we see a small hole in the front of Connally’s jacket, exactly as if the bullet had cleanly exited. Note the size of the button, for reference.

Thus, the tumbling single-bullet theory just gets deader and deader.

To sum up: the tumbling-magic-bullet theorists posit the bullet struck JFK in the upper back, then exited Kennedy’s neck so straight and cleanly that it left a small hole below Kennedy’s Adam’s apple—a hole so small that attending doctors in Parkland Hospital thought it an entrance wound.

Then (the magic-bullet theorists posit) the bullet tumbled after exiting Kennedy, although it somehow made a small hole in Connally’s shirt, and a small elliptical wound, and then stopped tumbling to tunnel through the Governor. And then the bullet exited exactly nose first, leaving a small hole in Connally’s coat.

At the risk of piling on, there is even more evidence the shot Connally received that day in Dallas was not tumbling.

Blundering Pathologists and Lawyers

Proponents of the single-magic-bullet theory posit the bullet must have tumbled upon leaving President John Kennedy’s neck and then entering Connally. Why?

That tumbling, proof that the magic bullet passed through JFK’s neck, is why the single magic bullet left a large wound on Connally’s back, the reasoning goes.

However, the original wound on Connally’s back was not a large one, as is sometimes erroneously asserted, including, embarrassingly, by not only the HSCA’s top lawyer, but also by its top pathologist!

As stated, Dr. Shaw clearly informed the WC and the HSCA that Connally’s original wound was a small vertical elliptical (or oval shape) injury 5/8ths of an inch long.

Some of this ground has been covered previously in an excellent article by Millicent Cranor, “Trajectory of a Lie,” at History Matters.

As noted by Cranor and in the record, Shaw explained to the WC and the HSCA that in order to clean and debride (cut away devitalized tissue) the wound, he enlarged the injury to twice its original size, to a final 3.0 centimeters long (1 1/4 quarter inch long).

OK, so the final surgically enlarged wound is a one-a-one-quarter inch long, on Connally’s back.

Here is how Michael Baden, who was chairman of the HSCA Forensic Pathology Panel, described Connally’s back wound in a book he authored: “He (Connally) removed his shirt. There it was—a two-inch long sideways entrance scar in his back. He had not been shot by a second shooter, but by the same flattened bullet that went through Kennedy.”

Huh?

So, the original wound, as described by the surgeon Shaw, was a vertical elliptical injury 5/8ths of an inch long.

But the final scar is a “two-inch long sideways entrance scar,” according to the triumphant Baden, and that means the bullet that struck Connally in Dallas had been tumbling?

How can Baden, a medical professional, bungle truth and common sense so badly? Had he never considered the small entrance hole in Connally’s shirt? Did he never read the reports by Dr. Shaw?

And how did a one-and one-quarter-inch final, surgically enlarged wound, as explained by the surgeon Dr. Shaw, become “two-inch long sideways entrance scar” in Baden’s version?

Even worse, Robert Blakey, chief counsel for the HSCA, fell into the same inexcusable misdiagnosis, also asking Connally to remove his shirt, and also describing the size of scar he had witnessed on the Governor’s back as proof of a tumbling bullet, and thus verifying the single-magic-bullet theory.

Were the topic not so grave, Team Inspectors Clouseau comes to mind.

But there is more.

Dr. Shaw also believed the bullet that coursed through Connally could not have struck a body beforehand, or “it would not have had sufficient force to cause the remainder of the Governor’s wounds.” After tunneling through five inches of Connally’s rib, the bullet then struck and shattered Connally’s wrist before burrowing onto Connally’s left leg.

But then, what did Shaw know? He had only worked on 900 bullet- and shrapnel-victims during WWII, and then another couple hundred such victims in Dallas.

Nevertheless, Baden and Blakey would have the final wording of the HSCA report, a type of indelible excrement on the committee’s escutcheon.

What the Connallys Said

But there is even more.

Governor Connally testified resolutely before the WC, and in many other forums (and has been recorded) that there were three shots that day in Dallas: The first shot struck JFK; the second shot struck the Governor in the back and immediately incapacitated him, and the third shot also struck JFK, with awful and fatal result. In other words, three shots, three hits, no tumbling.

(There may have been and likely were more shots that day in Dallas, but the gunfire may not have been audible in the Presidential limousine, variously due to simultaneous fire, silencers, or use of a pneumatic weapon. In addition, non-simultaneous shots can be heard simultaneously if shooters are at different distances from ear witnesses.)

Connally’s wife, at his side in the presidential limo, confirmed her husband’s account of the shot pattern many times. Secret Service agents Clint Hill and Sam Kinney, and presidential aide David Powers, all close at the scene on Nov. 22, also all say there were three separate shots that struck JFK and Connally that day, among many other witnesses.

As Connally stated: “Beyond any question, and I’ll never change my opinion, the first bullet did not hit me. The second bullet did hit me. The third bullet did not hit me.”

But Governor Connally, like Dr. Shaw—what does he know?

Zapruder Film

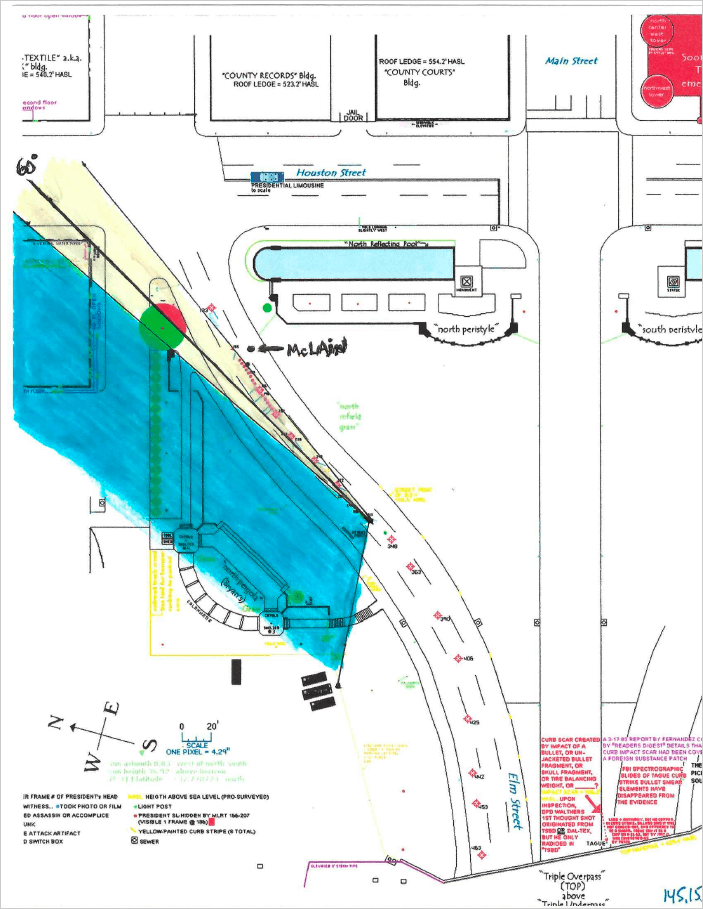

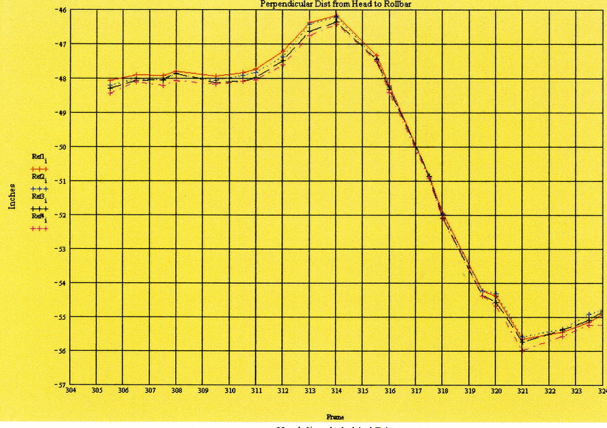

The Zapruder film almost certainly confirms the Connally’s version.

Here is Zapruder film frame 226, as JFK emerges from behind the Stemmons Freeway sign. JFK appears to have been struck, perhaps just before or while he was behind the sign. Jackie Kennedy looks concerned. Connally is blurry, but sitting upright.

Here is Z-film frame 245. Connally is halfway through a turn over his own right shoulder, just as he has recounted to the WC. Note, in order to turn around, Connally is leaning back. (Note: Try this yourself. Try to look over your own right shoulder at someone sitting behind you. Try leaning forward, and then leaning back, to look over your right shoulder.)

In the process of leaning back, Connally exposed his back at a more-acute angle to an elevated gunman, resulting in the original small elliptical wound described by Dr. Shaw.

This is Z-film frame 280. Note Connally has made a near-180-degree turn in his chair. The WC and HSCA and magic-bullet theorists posit this about-face by Connally happened after he has been shot through the chest and suffered a fractured wrist.

Connally and his wife said the Governor was trying to catch a glimpse of JFK, given commotion and gunfire, and this is before Connally has been shot. The Connally version appears to be true, beyond reasonable doubt.

This is Z-film frame 290. Unable to catch a view of JFK, who has slumped out of view, Connally is now returning to face forward.

And then Z-film frame 296. This appears to be when Connally was struck. Unfortunately, we cannot see Connally’s torso, but his face begins to grimace.

And this is Z file frame 300. Connally appears to be in agony.

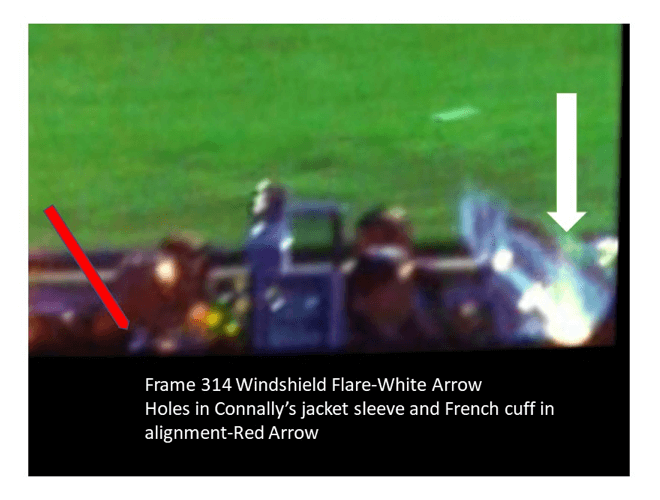

Z-film frame 313 follows, and shows a head shot to JFK.

The elapsed time between frame 296 and frame 313 is less than eight-tenths of one second, and by all accounts, a single-shot bolt action rifle requires a bare minimum of two seconds to even operate between shots, let alone aim and fire.

Conclusion

The reasonable, indeed nearly inevitable and all but certain conclusion is that a bullet did not tumble before striking Connally, and that the timing between shots cannot be explained by a lone gunman operating a single-shot bolt-action rifle.

The tumbling bullet theory was a desperate fiction invented to give support to the idea that single bullet caused all of Governor’s and the President’s neck wounds on Nov. 22. Otherwise there are too many shots to have been accomplished by a lone gunman with a single-shot bolt-action rifle.

But from the too-small hole in the rear of Connally’s shirt, to the small elliptical wound in Connally’s back, to the Connally’s testimony, to the observations of Dr. Shaw, and from a review of the Z-film, it is abundantly clear that the Governor was struck by a clean and separate shot.

Addendum

Recently, in the oft-excellent pages of the Education Forum, the WC testimony of Dallas Sheriff Seymour Weitzman was reprised in an interesting post by John Butler.

The relevant passage, in this context, regarding Nov. 22:

(WC Attorney) Joe Ball: How many shots did you hear?

Seymour Weitzman: Three distinct shots.

Joe Ball: How were they spaced?

Seymour Weitzman: First one, then the second two seemed to be simultaneously.

But like Connally and Dr. Shaw, what did Weitzman Know?

Second Addendum

Interestingly, Dr. Shaw even suggested more than one bullet might have struck Connally. Why?

The entrance wound on Connally’s wrist was on the side that most people wear the wristwatch, that is the non-palm side, also called the dorsal side. The bullet then exited through the palm side of the wrist.

Dr. Shaw wondered how Connally could hold his arm so the bullet would pass through his chest and then through the wristwatch-side (or dorsal side) of his wrist. And indeed, try sitting down, and then try to touch the face of your wristwatch (worn on the right wrist) to your chest. You can’t do it. You can place the palm side of your wrist against your chest easily.

One deduction is another bullet struck Connally’s wrist directly.

And indeed, Connally testified before the WC that bullets were entering the Presidential limousine as if from “automatic” weapon fire.

Yet the WC and HSCA posit the magic bullet passed through Connally’s chest, and then through dorsal, non-palm side of his wrist, a nearly impossible scenario, anatomically speaking.