Introduction

In his new book, Last Second in Dallas, Josiah Thompson, Ph.D. (philosophy) reported that Nobel Laureate, Luis Alvarez, committed scientific fraud involving the JFK assassination in a peer-reviewed journal, The American Journal of Physics (AJP). It was an extraordinary charge. But as physicians who have reported on the shoddy, biased work of numerous official, credentialed government-funded JFK assassination investigators,[1] we weren’t particularly surprised. We had long ago grasped that pro-Warren Commission journal articles generally fell into the category of junk science. But it was only from Thompson that we learned that the junkification of science traces all the way back to a Nobel Prize winner writing in 1976.

The AJP may have been the first respected science outlet to publish nonsense related to JFK’s death. It wouldn’t be the last. In the years since, many respected “peer reviewed” outlets have published rubbish churned out by a small band of anti-conspiracy activists. Among the most active during the past 20 years are some of the darlings of the mainstream media and the rapidly dwindling band of Warren Commission loyalists: Mr. Larry Sturdivan, Mr. Lucien Haag, Mr. Michael Haag (father and son), and Ken Rahn, Ph.D. In the past three years, a new star has soared into the JFK-junk science heavens, Nicholas Nalli, Ph.D.

An atmospheric chemist with no prior credentials in the JFK case, Nalli published two allegedly “peer reviewed” papers resuscitating the original, moribund theory that Alvarez had introduced in the AJP.[2] Namely, that it was a “jet effect” from Lee Oswald’s bullet that drove JFK “back and to the left.” He failed in spectacular fashion, not only because he placed his faith in Alvarez’s junk science, but also because he concocted a bit of junk science of his own. Predictably, Nalli’s paper was widely heralded. WhoWhatWhy’s Milicent Cranor, a serious student of the Kennedy case, noted that “It has been promoted in Daily Mail, Newsweek, history.com, Komsomolskaya Pravda, and several other places.”[3]

His efforts were not without value, however, for they served as reminders of the consistency with which Commission loyalists corrupt the peer review process in support of the government. And they demonstrated, yet again, that the Warren Commission’s theory of the assassination is a flop, including the “jet effect.”

THE “Jet Effect” and JFK:

Nobel Laureate Luis Alavarez and Jet Effect

America first saw the Zapruder film on March 6, 1975, when ABC broadcast Geraldo Rivera’s program, Good Night America.[4] Seeing Kennedy being blown back and to the left following the fatal shot at the infamous Zapruder frame 313 had an enormous impact on the public. To the eye, it sure looked like JFK had been struck from the right front. So how could Oswald’s shot from behind have driven JFK’s head back toward the assassin? The “scientific” answer came the following year.

In the September 1976 issue of the AJP, Alvarez announced that, “the answer turned out to be simpler than I had expected. I solved the problem (to my own satisfaction, and in a one-dimensional fashion) (sic) on the back of an envelope.” Although JFK’s head was struck from behind, he claimed it was the jettisoning of cranial contents out of the right front side of his skull that drove it back and to the left. The ejecta, he wrote, carried “forward more momentum than was brought in by the (impact of the) bullet…as a rocket recoils when its jet fuel is ejected.”[5]

To satisfy skeptics, including Mark Lane and Josiah Thompson who he named in the AJP, Alvarez ran experiments, and took a turn into the dark side: he shot at light weight, soft-skinned melons, not at all like bony human skulls, and he used the wrong kind of gun and the wrong kind of ammo. He declared:

It is important to stress the fact that a taped melon was our a priori best mock-up of a head, and it showed retrograde recoil in the first test…If we had used the ‘Edison Test,’ and shot at a large collection of objects, and finally found one which gave retrograde recoil, then our firing experiments could reasonably be criticized. But as the tests were actually conducted, I believe they show it is most probable that the shot in (Zapruder) 313 came from behind the car.[6]

Alvarez’s inventive hypothesis was subsequently buttressed by more analogous tests. This time shooting a Mannlicher Carcano, urologist John Lattimer, MD demonstrated the “jet effect” phenomenon. In 1995, in the “peer reviewed” Wound Ballistics Review, Lattimer reported that he shot both at melons as well as the backsides of filled human cadaver skulls that he perched atop ladders. Both melons and skulls recoiled back toward the shooter.[7]

Among Warren loyalists, those unexpected results are foundational. Skeptics remain dubious. But in 2018, Alvarez and Lattimer got new, theoretical support in a paper Nalli published in the supposedly “peer-reviewed” scientific journal, Heliyon. Reaffirming “jet effect” via a withering array of complex calculations, Nalli concluded:

It is therefore found that the observed motions of President Kennedy in the film are physically consistent with a high-speed projectile impact from the rear of the motorcade, these resulting from an instantaneous forward impulse force, followed by delayed rearward recoil and neuromuscular forces.[8]

Unfortunately, all of this lofty “peer reviewed” research is bunkum. It, and the JFK “jet effect” theory, are not only junk science, much of it is borderline fraud.

First, is it remotely credible that, as Alvarez claimed, a soft-shelled melon, even a tape-wrapped one, is the “best mock-up” of a bony human skull? A melon weighs about half what a human head does. A bullet would cut through it like a knife through butter. Second, it was no less than Warren loyalist John Lattimer, MD who revealed a key element of Alvarez’s work that the Nobel Laureate never mentioned in his paper. Apparently unable to get the results he wanted firing “slow,” ~2000 ft/second, jacketed Mannlicher Carcano bullets, Alvarez instead shot non-jacketed, soft-nosed .30-06 rounds, but not just any old .30-06 rounds, with their ~2800 ft/second muzzle velocity. Instead, he “hot-loaded” his cartridges to 3000 ft/sec. Only then did his melons exhibit his famous recoil “jet effect.”[9],[10],[11] Worse, Professor Alvarez also withheld other relevant information about his tests.

A few years ago, Josiah Thompson was given access to the photo file of the original shooting tests by one of Alvarez’s former graduate students, Paul Hoch, Ph.D. (physics).[12] As Thompson reported in LSID, Alvarez had, in fact, “shot at a large collection of objects”—coconuts, pineapples, water-filled jugs, etc. The only objects that demonstrated recoil were his “a priori best mock-up of a head,” the dis-analogous melons that were struck not by Oswald’s slower, jacketed bullets, but rather by supercharged, soft-pointed rounds. (Fig. 1)

An honest scientific report would have meticulously recounted the specifics of the testing and all of the experimental results, whether confirming or denying the author’s hypothesis. Readers are invited to scour Dr. Alvarez’s paper, which we’ve linked to, for his mentioning anywhere these other, inconvenient results. He buried them. He then devised a second test using only melons rigged from the outset to produce the “politically acceptable” result he wanted: recoil toward the rifle. (We won’t insult the intelligence of readers by recounting what happened when Alvarez’s team shot targets that were more analogous to skulls: coconuts.)

In his recent review of Thompson’s book, Nicholas Nalli hilariously agreed with the Nobel Laureate and his student Paul Hoch, that a melon is a “reasonable facsimile” of a human head: “Hoch noted that the melons consistently exhibited a ‘retrograde motion’ toward the shooter,” he wrote, “and Alvarez thus was able to demonstrate that a recoil effect is indeed possible.” Possible, indeed, if one shoots the wrong kind of target with the wrong kind of rifle and the wrong kind of ammunition; niggling details Nalli didn’t think worth mentioning.

Nalli also didn’t mention the significant fact that Alvarez had failed to disclose: the professor’s melons exhibited retrograde recoil only when struck by supercharged, soft-pointed hunting rounds, not by Oswald’s slower, jacketed rounds. Nor did he mention that the current authors exposed Alvarez’s chicanery in the AFTE Journal in 2016, noting that, except for the melons, everything he shot at flew away from the rifle, not toward it.[13]

Rather than objecting to Alvarez’s unscientific, selective reporting, Nalli sneered at “CTs (who) had gotten comfortable in rejecting Alvarez as some sort of one-off ‘government shill.’”[14] And he took after Thompson for his “not-so-subtle insinuation that Alvarez had ‘cherry-picked’ his data, a decidedly unethical and unprofessional practice in science. I was dumbfounded when I read this,” Nalli added, “and I can only empathize with how Alvarez might not have taken too kindly to the gall in the accusation.”[15]

Nalli is more upset that Thompson accurately outed Alvarez for cherry-picking than he is that Alvarez had unethically and unprofessionally cherry-picked in the first place. Although Nalli did admit that Alvarez had shot at “different targets,” he forgot to mention what Alvarez also forgot to mention: all targets but the melons fell away from the shooter. Nor does Nalli acknowledge what else Thompson discovered: this wasn’t the only time Alvarez had bent science to the political winds; or, to borrow Dr. Don Thomas’ useful euphemism, in a “socially constructive” direction.[16]

Luis Alvarez – Some Kind of Patriot?

LSID details that Alvarez once claimed that he had “proved” what the U.S. and Israeli government falsely claimed was true: that there had been no South African/Israeli nuclear test in the Indian Ocean—the politically sensitive, so-called “Vela Incident.”[17] But there had been one, a fact Alvarez tried to bury. The Nobel Laureate’s claim was subsequently shredded by private, government, and even military investigators,[18] a fact we also pointed out in the AFTE. So, Alvarez wasn’t a “one off government shill,” he was at least a “two-off government shill.” Predictably, Nalli says nothing about Thompson’s explosive discovery.

Furthermore, Alvarez gave a preposterous, if politically useful, explanation for why Zapruder frame 313 was blurred. He wrote:

[I]n the light of this background material we see that the obvious shot in frame 313 is accompanied immediately by an angular acceleration of the camera, in the proper sense of rotation to have been caused directly by shock-wave pressure on the camera body.[19]

As is well known, “shock waves” from bullet blasts travel at the speed of sound, about 1,100 ft/sec. They expand as a cone behind the nose of the bullet as it slices through air.[20],[21] As discussed below, had Oswald’s bullet struck at 313, the expanding shock wave from that missile would not have reached Zapruder in time to blur 313. (Only a shock wave from a “grassy knoll” shot—~60 feet from Zapruder—would have been close enough to nudge the camera and blur frame 313. See below.) It’s as difficult to believe Alvarez didn’t know that as it is to credit the sincerity of Nalli’s umbrage over Thompson’s critique of Alvarez’s selectively-reported shooting results, his, ahem, cherry-picking.

That comes as no surprise for it turns out that Nalli is himself no slouch when it comes to cherry-picking. One of his cherries of choice is the person who next picked up the “jet effect” baton after Alvarez. The aforementioned, pro-Warren urologist, John Lattimer, MD.

Dr. John Lattimer and Jet Effect

This time, conducting more analogous trials, John Lattimer shot human skulls to test for “jet effect.” Using a Mannlicher Carcano, he fired downward from the rear at filled human skulls that were perched atop ladders. The target skulls recoiled, but apparently not due to any “jet effect.” In his book, Hear No Evil, Donald Thomas, Ph.D. explained the obvious:

Lattimer’s diagrams reveal that the incoming angle of the bullet trajectory sloped downwards relative to the top of the ladder, with the justification that the assassin was shooting from an elevated position…But the downward angle would have had the effect of driving the skulls against the top of the ladder with a predictable result—a rebound.”[22] (A video clip of Dr. Lattimer’s shooting tests shows the ladder rocking forward as the skull is driven against the top of the ladder.[23])

Lattimer’s downward-shooting technique was precisely what longtime Warren loyalist Paul Hoch, Ph.D (physics) had warned against. The target should be fired upon along a horizontal trajectory, Hoch said, not at a downward angle. And the target should either be dangling from a wire or laying on a flat surface. Lattimer’s technique imparted downward and forward momentum to the skulls. That force was transmitted through to the ladder, causing it to move forward while the skull bounced backward. Unlike Dr. Lattimer’s skulls, the base of JFK’s skull and his jaw bone were not resting on a hard, flat surface. (It is also worth mention that the “wounds” sustained by the blasted skulls were not, as Dr. Lattimer reported, “very similar to those of the President.” While Nalli cites Thomas’s “Hear No Evil,” he omits any mention of Thomas’s devastating evisceration of Lattimer.)

But there is more reason than his tendentious skull shooting technique to distrust Lattimer. In a paper published in the medical/scientific literature, he said that he had also shot melons using MCC ammo. “No melon or skull or combination,” he reported, “ever fell away from the shooter in these multiple experiments,”[24] a finding that deserves an honorable place in the Journal of Irreproducible Results.[25] By contrast, Warren loyalist Lucien Haag reported what happened when he fired Carcano bullets at melons: “…the melons (which were free to move) remained in place, and the entry and exits holes were small.”[26] Douglas Desalles, MD and Stanford Linear Accelerator physicist, Arthur Snyder, Ph.D. shot melons with MCC ammo and found the same thing: little movement in the targets, though some did roll slowly away. (Lucien Haag, however, did finally get melons to recoil. But only when he fired after clipping the tips off Carcano rounds to expose the soft lead cores, justifying doing so by arguing that the tip of Oswald’s jacketed bullet would have been breached when it struck JFK’s skull.[27] However, when the U.S. government shot human skulls, no such phenomenon was observed—see below.)

There is a glaring omission that mars all the “peer reviewed” JFK papers by Alvarez, Lattimer, and Nalli. It is requisite, standard practice in medical/scientific publishing to acknowledge and integrate prior published research findings that are relevant to an author’s report. Writers elaborating on newly discovered aspects of the Theory of Gravity, for example, would likely give a tip of the hat to Issac Newton and Albert Einstein. Alvarez, Lattimer, and Nalli have observed this time-honored practice in the breach.

Testing for Jet Effect

For example, the results of Alvarez’s and Lattimer’s tests are in sharp contrast to similar, shooting tests conducted by University of Kansas’s pathology professor, Dr. John Nichols, MD, Ph.D., F.A.C.P.—as well as those performed by the U.S. government. Rather than shooting downward at skulls perched atop a flat surface, Nichols shot MCC ammo at both melons and cadaver material that were suspended by a wire. (As Warren Commission aficionado Paul Hoch, Ph.D. had recommended.) Professor Nichols’ finding? “This study did not demonstrate the jet effect and would lead us to reject the jet effect as the basis for President Kennedy’s backward head movement.”[28]

Nalli and Lattimer have never acknowledged Professor Nichols’ studies. Nor have Alvarez, Nalli, and Lattimer ever acknowledged even the fact that truly analogous skull-shooting experiments were actually conducted for the Warren Commission in 1964 at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds by the Biophysics Lab. Larry Sturdivan, an ardent anti-conspiracist, had intimate familiarity with those studies. He described them in testimony before the House Select Committee on Assassinations. Dried human skulls filled with gelatin were used. Goat skin was placed over the backs of the skulls to simulate Kennedy’s scalp and hair. While testifying, he projected movies of the actual tests, high speed films shot at 2200 frames/second. (Fig. 2)

Sturdivan swore:

As you can see, each of the two skulls that we have observed so far have moved in the direction of the bullet. In other words, both of them have been given some momentum in the direction that the bullet was going. This third one also shows momentum in the direction that the bullet was going, showing that the head of the President would probably go with the bullet…In fact, all 10 of the skulls that we shot did essentially the same thing. They gained a little bit of momentum consistent with one or a little better foot-per-second velocity…[29]

In his book, JFK Facts, Sturdivan reported a substantially higher velocity: “the (test) skull…moves forward at approximately 3 feet/sec, just as it must from the momentum deposited by the bullet.”[30] This higher figure is likely the more accurate, as it was not given off the cuff during testimony, but was written by Sturdivan while he was preparing his manuscript.

While neither Alvarez, Lattimer, nor Nalli mention those results, Sturdivan did, and dismissed their telling significance. His novel explanation was that the government’s shooting tests failed to show recoil from a “jet effect,” because the Biophysics Lab had filled their target skulls with “stiff gelatin,” a claim he made without evidence, and may therefore be dismissed without evidence.[31]

Ironically, although Sturdivan endorses the “jet effect” theory these days, he didn’t always. Sturdivan wrote in 2005:

The question is: Did the gunshot produce enough force in expelling the material from Kennedy’s head to throw his body backward into the limousine? Based on the high-speed movies of the skull shot simulations at the Biophysics Laboratory, the answer is no.[32]

Throwing JFK’s “body backward into the limousine” is code for the other factor besides “jet effect” that supposedly contributed to Kennedy’s rearward lurch: “neuromuscular reaction.” The current pro-government theory, which Nalli endorses, is that “jet effect” nudged JFK’s head backward a bit initially. Then a “neuromuscular reaction” took over, throwing his “body backward into the limousine.”

Neuromuscular Reaction and JFK

That some sort of a neuromuscular phenomenon drove Kennedy’s body backward after the “jet effect” knocked his head back has long been a staple of pro-Warren mythology. As Nalli recently put it, “The Zapruder Film…corroborates that another delayed (5–6 frame) forcing mechanism was at play (in addition to the projectile collision impulse and head cavity recoil – i.e. “jet effect”), and a neuromuscular spasm is the only physically plausible mechanism known to this author.”[33] (emphasis added)

Larry Sturdivan and Neuromuscular Reaction

If “Neuromuscular spasm” is the only physically plausible mechanism that Nalli knows of, it’s likely because he’s “cherry picked” the “expertise” of untrained, inexpert anti-conspiracy crusaders such as Mr. Larry Sturdivan, Mr. Lucien Haag, and Mr. Gerald Posner. Were Nalli the least bit serious, or curious, he’d have scoured and cited the work of proper authorities (e.g neurophysiologists, neurologists, perhaps even trauma surgeons). But he doesn’t. His principal “neuromuscular” sources are Sturdivan and Luke Haag who, circularly, sources Sturdivan.

Sturdivan’s “expertise” consists of a B.S. in physics from Oklahoma State University and an M.S. in statistics from the University of Delaware.[34] His lack of training and credentials in neurophysiology, medicine, or even human biology, is evident in the shoddiness of his explications. His shamelessness is evident in his putting himself forward as an authority on a neurophysiological phenomenon he lacks the credentials to discuss.

For example, Sturdivan has variously described Kennedy’s backward lunge as either a “decorticate”[35] or a “decerebrate” type of neuromuscular reaction, as if they were interchangeable. They’re not.[36] Nor are JFK’s motions either, as we will show, and as anyone who google-searches can discover for themselves in mere moments. In fact, we submit, JFK doesn’t exhibit any kind of “neuromuscular reaction.” But whether “neuromuscular,” “decorticate,” or “decerebrate,” some species of neurospasm has been proposed to explain Kennedy’s seemingly paradoxical rearward lunge since at least 1975.

Neuromuscular Reaction and the Rockefeller Commission

That year, former Warren Commissioner President Gerald Ford impaneled the Commission on CIA Activities within the United States. It is commonly referred to as the Rockefeller Commission, since Vice President Nelson Rockefeller was named chair.[37] Its creation was sparked by Seymour Hersh’s explosive revelations in the New York Times that the CIA had engaged in wildly illegal domestic operations against antiwar activists and dissidents during the Nixon years.[38] Its investigation extended into the question of whether there was evidence that JFK was “struck in the head by a bullet fired from the right front.”[39]

Although promoted as an independent probe, there were major conflicts of interest from the beginning, not least being that a former Warren Commissioner had established it;[40] that Nelson Rockefeller was himself deeply involved in some of the CIA’s unsavory history;[41] and that former Warren Commission counsel, and anti-conspiracy activist, David Belin, JD, was named executive director. Belin vowed to absent himself from any JFK-related issues. However, he made an exception. He sat in during the discussions of Rockefeller’s medical consultants, all of whom had similar potential conflicts of interests of their own.[42] The fix was in. Out plopped a flawed study that warmed the heart of the Warren Commissioner in the White House, as well as Commission loyalists.

Rockefeller’s experts made an astonishing number of factual errors (documented elsewhere).[43] Although error tends to be random, predictably the Rockefeller Commission’s all went in a single direction: to conclude that JFK’s backward jolt was not caused by the impact of a bullet coming from the front or right front. Drs. Spitz, Lindenberg, and Hodges said that Kennedy’s motion was caused by a violent straightening and stiffening of the entire body as a result of a seizure-like neuromuscular reaction due to major damage inflicted to nerve centers in the brain (Urologist John Lattimer picked up this theory and put it into the medical literature the following year, in 1976.[44]) Dr. Alfred Olivier, the pro-Warren consultant and Rockefeller expert, concurred. He reported that goat shooting experiments he had performed at Aberdeen Proving Grounds had demonstrated just such spasms, and that “jet effect” had also played a role in the Kennedy case.[45]

Neuromuscular Reaction and the House Select Committee on Assassinations

In 1979, a second group of experts, the Forensics Panel of the HSCA, also endorsed “neuromuscular reaction.” They, too, had significant conflicts of interest and they also made numerous, obvious pro-government errors (detailed elsewhere).[46] They wrote, “The (forensic) panel suggests that the lacerations of a specific portion of the brain—the cerebral peduncles as described in the autopsy report—could be a cause of decerebrate rigidity, which could contribute to the President’s backward motion.”

However, in the next sentence, the Panel added an important caveat that would be familiar to physicians who’ve had experience with head trauma patients (including author Aguilar, who was once the admitting general surgery resident in the emergency room of a major trauma center, UCLA/Harbor General Hospital): “Such decerebrate rigidity as Sherrington described,” the Forensic Panel correctly noted, “usually does not commence for several minutes after separation of the upper brain centers from the brainstem and spinal cord.” (emphasis added)

The panel also reported that “One panel member, Dr. Wecht, suspects that the backward head motion might be explained by a soft-nosed bullet that struck the right side of the President’s head simultaneously with a shot from the rear and disintegrated on impact without exiting the skull on the other side.” But, it added, “The remaining panel members take exception to such speculation…”[47]

The first point worth noting is that, though properly credentialed pathologists, none of the Rockefeller or HSCA experts were neurophysiologists, or neurologists, or neurosurgeons, or even trauma surgeons familiar with what actually happens to living humans who suffer brain trauma. They were forensic pathologists whose work was supplemented by consulting radiologists. They worked on dead people, using X-rays, microscopes and lab data. In other words, when opining on the somewhat obscure neurophysiologic phenomena in the JFK case, they weren’t speaking on the basis of any professional expertise; they were like orthopedists offering their “expert” opinions on a pediatric problem.

The Science of Neuromuscular Reactions

That is made plain by the fact that JFK’s recoil differs from any kind of recognized “neuromuscular” etiology the pathologists had specified, both in timing and manifestation, whether decorticate or decerebrate. Rather, there are multiple, independent avenues of evidence that converge in support of author Wecht’s minority ‘suspicion’ that it was a non-jacketed, soft-pointed shell that struck JFK from the right front, driving him back and to the left.

Decorticate posturing has been well described. The back arches rearwards, the legs extend and the arms flex inward. In decerebrate posturing the back arches and the legs extend, as they do in decorticate posturing. But the arms extend downward, parallel to the body.

If one compares his posture at Zapruder frame 230, or in any frame after the back shot but before the head shot, Kennedy is reacting to the first shot. His elbows are raised and abducted away from his body, and his arms and hands are flexed inward toward his neck.[48] (Fig. 3)

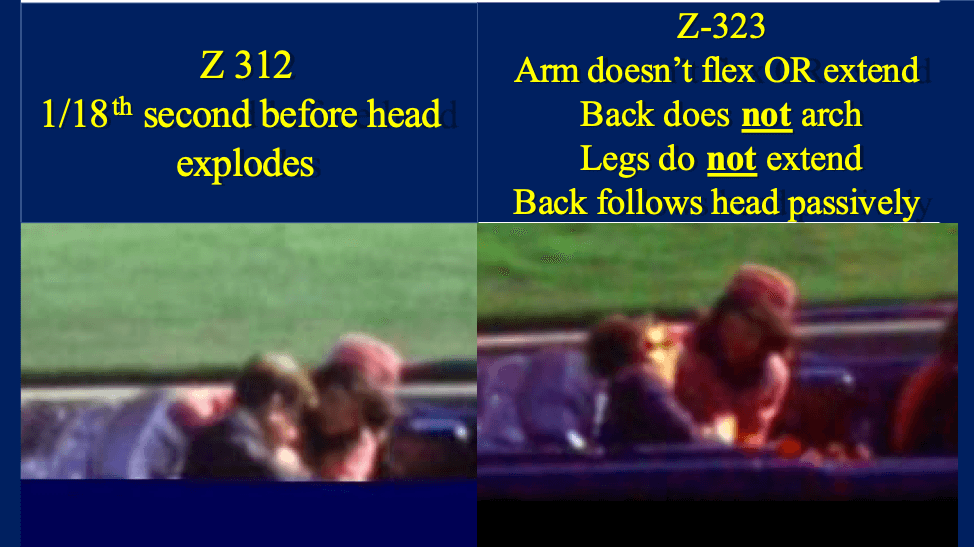

In the frames following the head shot, there is no “violent straightening and stiffening of Kennedy’s entire body,” as Rockefeller’s experts claimed. JFK’s head moves backward, but his back does not arch, nor do his upper arms move toward his body (adduct), but instead fall limply toward his side. And although not visible in the film, there’s no jerking motion of his body to suggest that his legs extend. Nor do his arms flex inward or extend inferiorly. They instead fall limply toward his lap. His upper body, likely paralyzed from the spinal injury caused by the first shot, passively follows his blasted cranium “back and to the left.”[49]

From the web, below are images depicting and contrasting decerebrate and decorticate posturing. JFK assumed neither posture in reaction to the head shot. (Fig. 4)

Decorticate posture results from damage to one or both corticospinal tracks. The upper arms are adducted and the forearms flexed, with the wrists and fingers flexed on the chest. The legs are stiffly extended and internally rotated with planter flexion of the feet.

Decerebrate posture results from damage to the upper brain stem. The upper arms are adducted and the forearms arms are extended, with the wrists pronated and the fingers flexed. The legs are stiffly extended, with plantar flexion of the feet.

But while it is known that decerebrate and decorticate postures do not manifest in split seconds, as Kennedy’s reactions did, there is another, more instantaneous “neurospasm” that has been demonstrated experimentally. Sturdivan described and demonstrated a split-second, neurospastic reaction that he likened to the President’s.[50] His evidence was an Edgewood Arsenal movie that he presented to the HSCA that showed a living goat being shot through the head with a .30 caliber bullet.

As the high-speed film rolled, he described the action: “…the back legs go out under the influence of the powerful muscles of the back legs, the front legs go upward and outward, that back (sic) arches, as the powerful back muscles overcome the those of the abdomen. That’s it.”[51]

Edgewood Arsenal’s chief investigator, veterinarian Alfred Olivier, DVM echoed Sturdivan, with whom he had worked at Edgewood. The goats, he said, “evidenced just such a violent neuromuscular reaction. There was a convulsive stiffening and extension of their legs to front and rear commencing forty milliseconds (1/25 of a second) (sic) after the bullet entered the brain.”[52] (Except for telling it what it wanted to hear, we can think of no reason why Sturdivan, a man with no training, background, or experience, would be the expert chosen by the HSCA to explain that Dealey Plaza offered an example of this complex neurophysiological phenomenon.)

In his book The JFK Myths, Sturdivan reproduced a series of still photographs of the goat-shooting experiment that he said demonstrated the goat’s evanescent, “JFK-like” reaction to being shot in the head. Sturdivan writes, “His (the goat’s) back arches, his head is thrown up and back, and his legs straighten and stiffen for an instant before he collapses back into his previous flaccid state.”[53] (Fig. 5)

Elaborating to the HSCA, Sturdivan drew the Dealey Plaza parallel:

…since all (of JFK’s) motor nerves were stimulated at the same time, then every muscle in the body would be activated at the same time. Now, in an arm, for instance, this would have activated the biceps muscle but it would have also activated the triceps muscle, which being more powerful, would have straightened the arm out. With leg muscles, the large muscles in the back of the leg, are more powerful than those in the front and, therefore, the leg would move backward. The muscles in the back of the trunk are much stronger than the abdominals and, therefore, the body would arch backward.[54]

In essence, the goat-like posture he described as JFK’s was a brief “decerebrate” posture—back arched, arms and legs extended. In a filmed interview, Sturdivan confidently demonstrated the neurological phenomenon, arching his upper body and arms upward and backward.[55] (Fig. 6) Sturdivan’s is a specific posture that JFK never remotely manifested. (Fig. 7) Not only was Sturdivan’s a specific posture one that JFK never remotely manifested, Sturdivan’s arms aren’t ‘straightened out’ as he testified they should have been. (Fig. 6) The “neuromuscular reaction” expert’s dis-analogous posture brought to mind a particularly apt Charles Darwin quip: “Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

Furthermore, were Kennedy’s posture truly a decorticate or decerebrate reaction of some sort, it’s likely he’d have maintained that backward-arched posture. He doesn’t.

In the Zapruder frames following frame 321, 4/9th seconds after the head shot, JFK bounces off the back seat of the limo and starts moving forward. His back then curls forward following his head, though at a slower speed than his head does. After frame 327, the advancing velocity of Kennedy’s head doubles from what it had been between frames 321 and 327, moving ahead at a faster clip than his head had rocketed rearward after the strike at 313. His back follows. Thus, Kennedy’s head and upper back not only “flexed” forward, when they should have been arching backward in decorticate or decerebrate spasm, his head also sped up, perhaps due to what Thompson has recently proposed: an acoustics matching, X-ray matching, second head shot striking JFK from behind at frame 327-8.[56] (see below)

While there is much more that could be said, the point here is that Nalli had no reason but the obvious one to trust Sturdivan, Haag, and Posner on this. None have the requisite training or background. Nor do they grasp the neurophysiological phenomena they’ve invoked to defend the government’s preferred scenario. Moreover, they have no answer to the science-based debunkings that have previously been published. But what they do have is an allegiance to the government’s preferences.

These are things Nalli would have known about “neuromuscular reaction” had he but followed standard scientific protocol and done a proper literature review prior to writing. If he had, he’d have addressed the AFTE piece Wecht and I wrote, the very one he cited in his own footnotes. That piece explored “neurospasm” in detail, with hot-linked footnotes to credible sources.[57] Instead, he ignored the science to stand with his cherry-picked, anti-conspiracy nonexperts. And not only on Kennedy’s reaction to the head shot. He also did so in another scientific area of the Kennedy case: Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA), a sophisticated technology once said to be able to match recovered bullet fragments to the bullets they came from.

Neutron Activation Analysis and JFK

On this issue, Nalli turned yet again to his Zelig—“neurospasm expert” Larry Sturdivan—who was now masquerading as an authority in another area of science in which, at best, he holds the rank of discredited amateur.

In a junky, “peer reviewed” paper published in 2004, Sturdivan touted NAA as the Rosetta Stone: proof that all the bullets and fragments recovered from the assassination traced to but two rounds that had been firearms-matched to Oswald’s rifle.[58] Ergo, no one but Oswald could possibly have done it. That extraordinary, and seemingly dispositive, claim was first made to the House Select Committee on 8 September 1978 by NAA authority, Vincent Guinn, Ph.D.[59]

In his review of Last Second in Dallas, Nalli touts Guinn. He writes:

…that it was ‘highly probable’ that the fragments in Gov. Connally’s wrist were from the ‘stretcher bullet’ (CE399) found at Parkland Hospital and that the fragments from President Kennedy’s head were from the same bullet as the fragments found in the limousine, thereby providing strong evidence that only two bullets caused all the wounds.[60]

Besides Guinn’s testimony and Sturdivan’s paper, there is other “peer reviewed” literature that backs Nalli up on NAA, including a paper written by Kenneth Rahn with Larry Sturdivan as coauthor,[61] as well as “peer reviewed” papers written by Lucien Haag touting NAA and published in the AFTE Journal.[62]

(Nalli ignores that the government’s own evidence, and that of an FBI Agent, Bardwell Odum, have shown that the so-called “stretcher bullet” now in evidence—Warren Commission Exhibit #399—is not the same bullet that was found on a Parkland stretcher on 11/22/63. See “The Magic Bullet: Even More Magical Than We Knew?” by Aguilar and Thompson.[63])

But Nalli did allow that, “There has apparently been some degree of legitimate dispute about the NAA findings of Guinn. However, counterarguments have since been advanced from forensic experts such as Larry Sturdivan (cf. The JFK Myths) (sic) and Luke Haag. Lacking personal expertise, I shall remain, for the time being, agnostic on Guinn’s findings. Sturdivan and Haag are not to be easily dismissed…”

Nalli neither mentions nor alludes to what the “legitimate dispute” is all about, nor even who has disputed Guinn, Sturdivan, and Haag. He has a good, if ‘socially constructive,’ reason not to. It would be difficult to explain why untrained, uncredentialed, anti-conspiracy evangelistic “forensic experts,” Sturdivan and Haag, would also happen to have expertise on NAA that’s on par with their detractors who have, in fact, quite ‘easily dismissed’ Sturdivan and Haag (as well as Kenneth Rahn, Ph.D., Sturdivan’s coauthor).

The ‘legitimate disputants’ Nalli didn’t think worth mentioning include the FBI’s National Laboratory, which abandoned the use of NAA to match bullets and fragments in 2005 because of its serious deficiencies;[64] two “conspiracy agnostic,” nationally recognized NAA authorities from Lawrence Livermore National Lab, Eric Randich, Ph.D. and Pat Grant, Ph.D, who debunked Guinn’s JFK claims in the prestigious Journal of Forensic Sciences[65] (Grant had studied for his Ph.D. under Guinn, among others, at UC Irvine, and bore him no malice.[66]), a distinguished professor of statistics at Texas A&M University, Clifford Spiegelman, Ph.D. and his coauthor, FBI chief lab examiner William Tobin, who, among other things, eviscerated the flawed statistical analysis the non-statistician, Sturdivan, had published supporting NAA,[67] and others.[68]

Furthermore, Nalli had every good reason to know of these inconvenient “alternative” facts. They’ve attracted considerable interest among assassination students, and they are easily found by a google search.[69] Moreover, they were explored in extenso in a piece I wrote with coauthor Wecht that Nalli cites in his footnote #58. That article included a detailed discussion of the collapse of NAA in bullet matching studies, both in the Kennedy case and elsewhere. It also provided the citations found here, with hotlinks to the peer reviewed papers and the source documents themselves.[70]

Moreover, Nalli fails to mention that neither Sturdivan nor Haag have any primary expertise in NAA. They have no applicable training or background, and no credible NAA research, apart from Sturdivan’s debunked statistical analysis that was demolished, without refutation, by the statistics professor at Texas A&M, by the NAA authorities at Lawrence Livermore Lab,[71] and by Stanford Linear Accelerator physicist, Arthur Snyder, Ph.D.[72]

For Nalli to put lightweights Sturdivan and Haag on one side of the NAA scale, and these heavy-weight ‘legitimate disputants’ on the other, and say he sees an even balance is exactly the kind of anti-science, cherry picking that skeptics have learned to expect from pro-Warren “experts.” But the irony doesn’t end there.

Referring to Thompson’s showcasing the work of the internationally recognized acoustics authority, James Barger, Nalli sniffed that “Thompson has no problem ‘appealing to authority’ when it suits him.” Barger, of course, is an actual internationally renowned authority to whom one may perfectly appropriately “appeal.” Nalli’s sources, not so much. He knowingly ignored credentialed, legitimate, published authorities, but had ‘no problem appealing to the authority’ of anti-conspiracy nonexperts who have fed him the discredited “science” he wants. Would that be the worst of Nalli’s problems. It’s not. His preposterous presuppositions are far worse.

Nicholas Nalli’s Calculations Prove JFK Had an Extraordinary Brain

One of Nalli’s sillier affronts to science has to do with the core of his anti-conspiracy case: how he explains physics of Kennedy’s jet recoil. After autopsy, JFK’s brain weighed 1500 grams. (Oddly the brain was not weighed during autopsy.) Nalli calculated that it must have weighed much more when he was struck, 2100 grams in fact. Why? Because his “physics based,” jet effect computations proved that a forward-jetting mass of 600 grams was physically required to give the propulsion necessary to drive Kennedy’s head rearward as fast as we see in the Zapruder film. Pure codswollop.

What Nalli could have easily discovered in a 30-second google search, and what any legitimate “peer reviewer” would have told him, is that human brains simply don’t weigh anywhere near that much. Rather, it’s an unusual complete and undamaged brain at autopsy that even weighs as much as 1500 grams. The average weight being between 1250 grams and 1400 grams.[73] Nalli’s 2,100 gm brain “has been the cause of much merriment among the knowledgeable.” WhoWhatWhy researcher Milicent Cranor quipped, “It’s what publishers call a ‘howler.’”[74] Researcher David Mantik, MD, Ph.D. (physics) emphasized this as but one of Nalli’s myriad “Omissions and Miscalculations.”[75]

Six months after Nalli’s paper came out, he put out a correction. “[I]t has also come to the author’s attention,” he wrote, “that the estimate used for President Kennedy’s ‘intact’ brain mass (2100 g) … was most likely too large, falling well outside of the normal range (probably more than 3σ) for human males; this is not an error per se, but rather simply an oversight.”[76] (our emphasis) “Most likely too large?” Ok. Not an error, “simply an oversight?” Ok again. But it wasn’t only Nalli’s “oversight,” it was also his “peer reviewers’” too. Did no one bother to google for even 30 seconds to check if one of Nalli’s core suppositions—JFK’s premortem brain weight—had any basis in reality?

Unfazed, he reran calculations based on three new, hypothetical premortem brain weights: 1800 gm, 1650 gm, and 1500 gm. To get the requisite rearward thrust with these lower brain weights, Nalli simply upped the exit speeds at which he presumed the escaping brain mass must have jetted. The idea being that if a lower mass escaped at a higher velocity, it’d produce the same “jet effect” as a larger mass exiting at a lower speed. “These corrections,” he wrote, “do not affect any of the conclusions presented in the paper.” Jaw dropping.

First, as previously noted, although not as extreme as 2100 grams, both 1800 grams and 1650 grams are also well beyond the range of a normal, complete adult human brain, both in the medical literature, as well as in the personal experience of coauthor Wecht, a forensic pathologist with over 40,000 autopsies under his belt. They might remotely be possible, but only if Kennedy had a very large cranium. As David Mantik pointed out, JFK’s head wasn’t particularly large; his hat size was average (7 3/8).[77]

So then, how about Nalli’s third supposition, that Kennedy’s premortem brain might have weighed as little as 1500 grams? It was as preposterous as it was unsurprising that Nalli seriously proposed that Kennedy’s brain could still have weighed what it did before it was blasted, before much of it was blown all over the limousine, its occupants, the Secret Service agents, the motorcycle cops to JFK’s left and rear, all over Dealey Plaza, and even after Jackie had handed “a big chunk of the President’s brain” to Parkland’s treating anesthesiologist, Professor Marion T. (“Pepper”) Jenkins, MD.[78] We struggle to think of a clearer example of a “scientist” forcing evidence to fit his pet theory. Science is supposed to work by finding a theory that explains the evidence.

(Outside the scope of this essay is the important question of how Kennedy’s severely blasted brain could turn up at autopsy weighing 1500 grams, which is more than an average, complete human brain. ARRB investigator Douglas Horne has suggested that two different “JFK” brains were examined during two different “supplemental” exams that were done at different times after the original autopsy. Some readers will shy from such a daring, “conspiratorial” assertion. However, can there be any doubt but that what remained of Kennedy’s actual brain didn’t weigh 1500 gms when it was pulled from his cranium? This important and fascinating issue is explored elsewhere.[79],[80])

How Peer Reviewed Medical/Scientific Journalism is Corrupted in the Kennedy Case

That so much pro-government nonsense got through peer review and into a scientific journal will come as no surprise to most Warren skeptics. It’s happened often. The mechanics of how this likely happened in Nalli’s case is an important and fascinating story, one that has clear traces to Nalli’s major source and most lauded collaborator, Larry Sturdivan.

After reading Nalli’s paper in Heliyon, it occurred to us that we might try to publish one in that journal ourselves. We wrote one and put our submission through Heliyon’s required on-line portal, a now-standard process among scientific journals. After uploading it to the site, one of us (GA) followed Heliyon’s prompts to complete the process. Immediately the following asks from Heliyon popped up. GA stared at them in amazement and delight—Heliyon isn’t a real peer reviewed, scientific journal; it’s a pay-to-publish vanity journal!

Prompt #1: Please suggest potential reviewers for this submission and provide specific reasons for your suggestion in the comments box for each person. Please note that the editorial office may not use your suggestions, but your help is appreciated and may speed up the selection of appropriate reviewers. Fill in as much contact information, ideally including a link to their Google Scholar, Scopus or institutional webpage to allow us identify the person correctly. Please avoid suggestions who have a conflict of interest, such as colleagues, collaborators, co-authors (shared publications in the last three years) or people with whom you share funding.

“Current Suggested Reviewers List” Add Suggested Reviewer

Prompt #2: Please identify anyone you would prefer not to review this submission. Fill in as much contact information to allow us to identify the person in our records, and provide specific reasons why each person should not review your submission in their comments box. Please note that we may need to use a reviewer you identify here, but will try to accommodate author’s wishes when we can. If you have additional concerns about this issue please indicate them in your cover letter.

“Currently Opposed Reviewers List”

Prompt #3: Article Publishing Charge. Heliyon is a fully Open Access journal. The journal’s costs are covered solely by author publication charges. There are no subscription fees for our readers, or page and figure charges for our authors. Accordingly, all authors of accepted articles will receive an invoice charging the article publication fee of $1,750 USD (plus VAT and local taxes where applicable).

The journal explained its financial demand: “Heliyon has a small budget for reducing Open Access charges for authors in developing countries and others in genuine financial hardship…”

Since Nalli doesn’t live in a developing country, nor is it likely he faces “genuine financial hardship,” it’s a safe bet that Nalli paid to have his work published, or that someone else paid for him. Given his whopping errors, it’s likely that Heliyon didn’t send it to knowledgeable, independent experts, but that Nalli picked them. And it was probably Nalli who specified whom he didn’t want reviewing it. Heliyon’s requirements prompted us to check Nalli’s acknowledgements.

“First and foremost,” he wrote, “I am grateful to Larry M. Sturdivan (wound ballistics expert for the HSCA) (sic) for very helpful discussions pertaining to his previous work as well as for reviewing my initial drafts and providing expert feedback…I am also grateful for the critical reading and constructive professional feedback of the three anonymous peer-reviewers.” (our emphasis)

“Anonymous peer-reviewers”? Not likely, given that Heliyon explicitly asks authors to suggest the reviewers they want. Nalli’s published rubbish proves precisely why peer review by knowledgeable, independent, anonymous reviewers is so important. Nalli’s reviewers were almost certainly uninformed, incurious, anti-conspiracy advocates. As one of us (GA) pondered this discovery, he had a déjà vu moment.

Nalli’s charade bears a striking resemblance to an analogous episode in 2003 and 2004, in which Sturdivan had played a similar, behind-the-scenes role. In that case, Sturdivan hornswoggled a respected, legitimate “peer review” journal, Neurosurgery, into letting him collaborate with, and “peer review,” error-ridden, pro-Warren Commission work that the hapless journal editors published. It’s a fascinating tale, one that embarrassed both the journal and a respected University of California, San Diego neurosurgery professor who was left holding the bag. It also hints at a pattern: anti-conspiracists publishing under the respected mantle of “peer reviewed” scientific journalism, while violating the principles that have earned the “peer review” process deserved admiration.

see Part 2

[1] Aguilar G. Cunningham, K. “How Five Investigations into JFK’s Medical/Autopsy Evidence Got It Wrong.” May, 2003. Available here.

Cyril Wecht, MD, JD. New York Times, 6/12/1975. “Doctor Says Rockefeller Panel Distorted His View on Kennedy.” Available here.

[2] Alvarez L, “A Physicist Examines the Kennedy Assassination Film,” American Journal of Physics, Vol. 44, No. 9, September, 1976. Available here.

[3] Cranor, M. “Scientist’s Trick ‘Explains’ JFK Backward Movement When Shot.” Available here.

[4] “When was the Zapruder film first shown to the American people?” Available here.

[5] Alvarez L, “A Physicist Examines the Kennedy Assassination Film,” American Journal of Physics, Vol. 44, No. 9, p. 819, September, 1976. Available here.

[6] Alvarez L, “A Physicist Examines the Kennedy Assassination Film,” American Journal of Physics, Vol. 44, No. 9, September, 1976. Available here.

[7] Lattimer JK, Lattimer JK, et al. “Differences in the Wounding Behavior of the Two Bullets that Struck President Kennedy; An Experimental Study,” Wound Ballistics Review, V2(2)361995. Available here.

[8] Nalli, Nicholas. Gunshot-wound dynamics model for John F. Kennedy assassination. Heliyon. Vol. 4, No. 4, e00603, April 01, 2018. Available here.

[9] Lattimer JK, Lattimer J, Lattimer G. “An Experimental Study of the Backward Movement of President Kennedy’s Head,” Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. February, 1976, Vol. 142, pp. 246–254. Available here.

[10] Lattimer, J. Kennedy and Lincoln. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1980, p. 250.

[11] Lattimer JK, Lattimer J, Lattimer G. “An Experimental Study of the Backward Movement of President Kennedy’s Head,” Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. February, 1976, Vol. 142, pp. 246–254. Available here.

[12] Josiah Thompson, Ph.D. gave a public lecture in October, 2013 and projected images from Alvarez’s shooting tests. Wecht Center Symposium on the 50th Anniversary of the Assassination of President Kennedy Available here.

[13] Aguilar G. Wecht CH. AFTE Journal, Vol. 48, No 2, Spring 2016, p. 712. Available here.

[14] Nalli, N. “The Ghost of the Grassy Knoll Gunman and the Futile Search for Signal in Noise,” a review of J. Thompson’s book, “Last Second in Dallas,” 6.3.21. Available here.

[15] Nalli, N R. “The Ghost of the Grassy Knoll Gunman and the Futile Search for Signal in Noise,” a review of J. Thompson’s book “Last Second in Dallas” published on 6/3/21. Available here.

[16] Donald Byron Thomas, Hear No Evil – Social Constructivism & Forensic Evidence in the Kennedy Assassination. Ipswich, MA. Mary Ferrell Foundation Press, 2010

[17] Thompson, Josiah, Last Second in Dallas. Lawrence, Kansas. University Press of Kansas, 2021, pp. 281–284.

[18] * The Vela Incident – Nuclear Test or Meteoroid? National Security Archive. Available here.

* A good summary of government evidence proving a nuclear blast in the Vela Incident is available in: Report on the 1979 Vela Incident. Available here. [“(Investigative journalist Seymour) Hersh reports interviewing several members of the Nuclear Intelligence Panel (NIP), which had conducted their own investigation of the event. Those interviewed included its leader Donald M. Kerr, Jr. and eminent nuclear weapons program veteran Harold M. Agnew. The NIP members concluded unanimously that it was a definite nuclear test. Another member—Louis H. Roddis, Jr.—concluded that ‘the South African-Israeli test had taken place on a barge, or on one of the islands in the South Indian Ocean archipelago.’” [Hersh 1991; pg. 280-281. Available here.] He also cited internal CIA estimates made in 1979 and 1980 which concluded that it had been a nuclear test.

“The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory conducted a comprehensive analysis, including the hydroacoustic data, and issued a 300-page report concluding that there had been a nuclear event near Prince Edward Island or Antarctica [Albright 1994b].”

[19] Alvarez L, “A Physicist Examines the Kennedy Assassination Film, American Journal of Physics Vol. 44, No. 9, p. 817. September, 1976. Available here.

[20] “The speed of sound, known as Mach 1, varies depending on the medium through which a sound wave propagates. In dry, sea level air that is around 25 degrees Celsius, Mach 1 is equal to 340.29 meters per second, or 1,122.96 feet per second.” Available here.

[21] Robert C. Maher. “Summary of Gun Shot Acoustics,” Montana State University 4 April 2006. “A supersonic bullet causes a characteristic shock wave pattern as it moves through the air. The shock wave expands as a cone behind the bullet, with the wave front propagating outward at the speed of sound.” Available here.

[22] Don Thomas. Hear No Evil. Ipswich, MA. Mary Ferrell Foundation Press, 2010, pp. 362–363.

[23] Dr. John Lattimer fired at human skulls from above and behind with a rifle and ammunition identical to those Oswald used. Clicking on the image at right will download a video clip of one of Lattimer’s shooting experiments. Note that the ladder rocks forward after bullet impact, reflecting the forward momentum transfer.

[24] Lattimer JK, Lattimer J, Lattimer G. “An Experimental Study of the Backward Movement of President Kennedy’s Head,” Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. February, 1976, Vol. 142, pp. 246–254. Available here.

[25] The Journal of Irreproducible Results 1980-2003. Available here.

[26] Haag, L. “President Kennedy’s Fatal Head Wound and his Rearward Head ‘Snap,’” AFTE Journal, Vol. 46, No. 4, Fall 2014, p. 283; see Figure 8

[27] Haag, L. President Kennedy’s Fatal Gunshot Wound and the Seemingly Anomalous Behavior of the Fatal Bullet. AFTE Journal, Vol. 46, No. 3, Summer 2014, p. 218ff.

[28] John Nichols, MD shooting experiments, accessed at Baylor University. Available here.

[29] Sturdivan LM. HSCA testimony, Vol.1:404. Available here.

[30] Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. 164.

[31] Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. 164.

[32] Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. 162.

[33] Nalli, Nicholas. Gunshot-wound dynamics model for John F. Kennedy assassination. Heliyon. Vol. 4, No. 4, e00603, April 01, 2018. Available here.

[34] Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. xxiii.

[35] Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. 170.

[36] Sturdivan, L. Letter to the editor. AFTE Journal. 2015 Vol. 47, No. 3, p. 143.

[37] “Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities within the United States,” June, 1975. Available here.

[38] Hersh S M, “Huge C.I.A. Operation Reported in U.S. Against Antiwar Forces, Other Dissidents in Nixon Years,” New York Times, 12.22.74. Available here.

[39] Rockefeller Commission Report, Chapter 19, p. 257 ff. Available here.

[40] George Washington University’s National Security Archive documented that the Rockefeller Commission “ceded its independence to White House political operatives.” Available here.

[41] “Gerald Ford White House Altered Rockefeller Commission Report in 1975; Removed Section on CIA Assassination Plots,” National Security Archive. Available here.

[42] See: Aguilar G, Cunningham K. A detailed discussion and source documents are available on line at: “How Five Investigations into JFK’s Medical/Autopsy Evidence Got It Wrong,” Part IV. The Rockefeller Commission. Available here.

[43] Aguilar G, Cunningham K. “How Five Investigations into JFK’s Medical/Autopsy Evidence Got It Wrong,” Part IV. The Rockefeller Commission, 2003. Available here.

[44] Lattimer JK, Lattimer J, Lattimer G. “An experimental Study of the backward Movement of President Kennedy’s Head,” Surgery, Gynecology & Obstretics, Vol. 142, pp. 246–254. Feb, 1976. Available here.

[45] Rockefeller Commission Report chapter 19, p. 261–263. Available here.

[46] Aguilar G, Cunningham K. “How Five Investigations into JFK’s Medical/Autopsy Evidence Got It Wrong,” Part V. The ‘Last’ Investigation – The House Select Committee on Assassinations, 2003. Available here.

[47] HSCA, Vol. 7, p. 174. Available here.

[48] Zapruder frame 230. Available here.

[49] Zapruder frame 320. Available here.

[50] Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. 170.

[51] Sturdivan L. HSCA testimony, p. 417. Available here.

[52] Rockefeller Commission Report, p. 262. Available here.

[53] Sturdivan, L M., “The JFK Myths: A Scientific Investigation of the Kennedy Assassination,” Paragon House, St. Paul, MD (2005), pp. 164, 166.

[54] Sturdivan L. HSCA testimony. Vol. 1, p. 415. Available here. [Full quote: “Now, the extreme radial velocity imported to the matter in the President’s head, the brain tissue, caused mechanical movement of essentially everything inside the skull, including where the cord went through the foramen magnum, that is, the hole that leads out of the skull down the spinal cord. Motion there, I believe, caused mechanical stimulation of the motor nerves of the President, and since all motor nerves were stimulated at the same time, then every muscle in the body would be activated at the same time. Now, in an arm, for instance, this would have activated the biceps muscle but it would have also activated the triceps muscle, which being more powerful, would have straightened the arm out. With leg muscles, the large muscles in the back of the leg, are more powerful than those in the front and, therefore, the leg would move backward. The muscles in the back of the trunk are much stronger than the abdominals and, therefore, the body would arch backward.”]

[55] “Larry Sturdivan Arched Dramatically Backwards.” Available here.

[56] Thompson J. Last Second in Dallas. Op. Cit.

[57] Nalli, Nicholas. Gunshot-wound dynamics model for John F. Kennedy assassination. Heliyon. V.4(4), e00603, April 01, 2018. Available here. See footnote #58 citing letter by G Aguilar, MD and C. Wecht, MD, JD. The actual letter, as published by the AFTE Journal. Available here.

[58] Sturdivan L, Rahn K. “Neutron Activation and the Kennedy Assassination – Part II, Extended Benefits.” Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, Vol. 262, No. 1 (2004), p. 221.

[59] Testimony of Dr. Vincent P. Guinn, Sept. 8, 1978, I HSCA-JFK hearings, 491ff. Available here.

[60] Nalli, N R. “The Ghost of the Grassy Knoll Gunman,” a review of J. Thompson’s book “Last Second in Dallas” published on-line, 6/3/21. Available here.

[61] * Rahn K, Studivan L. “Neutron activation and the JFK assassination Part I. Data and interpretation.” Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, Vol. 262, No. 1 (2004), pp. 205, 213.

* Sturdivan L, Rahn K. “Neutron Activation and the Kennedy Assassination – Part II, Extended Benefits.” Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, Vol. 262, No. 1 (2004), p. 221.

[62] *Haag L. “Tracking the ‘Magic’ Bullet in the JFK Assassination,” AFTE Journal, Vol. 46, No. 2, Spring 2014.

* Authors Aguilar and Wecht published a rebuttal to Haag’s defense of NAA in the AFTE Journal. Haag doubled down on his defense of NAA in a letter published by the AFTE Journal: Haag. L. “Author’s response to Doctors Aguilar and Wecht.” AFTE Journal, Vol. 47 No. 3 (Summer 2015), p. 139.

[64] “FBI Laboratory Announces Discontinuation of Bullet Lead Examinations,” September 1, 2005. FBI National

Press Office. Available here.

Possley, M., “Study shoots holes in bullet analyses by FBI,” Chicago Tribune, 2.11.2004

[65] * Erik Randich Ph.D., Patrick M. Grant Ph.D., Proper Assessment of the JFK Assassination Bullet Lead Evidence from Metallurgical and Statistical Perspectives. Journal of Forensic Sciences, V.51(4)717 ff.July 2006. Available here.

* Erik Randich 1 , Wayne Duerfeldt, Wade McLendon, William Tobin. A metallurgical review of the interpretation of bullet lead compositional analysis. Forensic Sci Int. 2002 Jul 17; 127(3), pp. 174–91.

[66] Pat Grant, Ph.D. “Commentary on Dr. Ken Rahn’s Work on the JFK Assassination Investigation.” Available here.

[67] Cliff Spiegelman, William A. Tobin, William D. James, Simon J. Sheather, Stuart Wexler and D. Max Roundhill. CHEMICAL AND FORENSIC ANALYSIS OF JFK ASSASSINATION BULLET LOTS: IS A SECOND SHOOTER POSSIBLE?

The Annals of Applied Statistics 2007, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 287–301. Available here.

[68] * Giannelli, Paul, “Comparative Bullet Lead Analysis: A Retrospective,” Case Western Reserve, Sept., 2001. Available here.

* William Tobin. “Comparative Bullet Lead Analysis: A Case Study in Flawed Forensics,” www.nacdl.org The Champion. Available here.

* Charles Pillar. “Report Finds Flaws in FBI Bullet Analysis.” Los Angeles Times, 2/4/2004. Available here.

[69] Cliff Spiegelman, Ph.D. “What new forensic science reveals about JFK assassination.” Salon.com, 12/12/2017. Available here.

See also: Pat Grant, Ph.D. (Lawrence Livermore Laboratory). Commentary on Dr. Ken Rahn’s (NAA) Work on the JFK Assassination Investigation. Available here.

[71] See Pat Grant’s evisceration of NAA defender, Ken Rahn. “Commentary on Dr. Ken Rahn’s Work on the JFK Assassination Investigation.” Available here.

[72] Arthur Snyder, Ph.D. Comments on the Statistical Analysis in Ken Rahn’s Essay: “Neutron-Activation Analysis and the John F. Kennedy Assassination.” Available here.

[73] Brain Facts and Figures. Available here.

[74] Cranor, Milicent. Scientist’s Trick ‘Explains’ JFK Backward Movement When Shot, 05/31/18. Available here.

[75] Mantik, D. The Omissions and Miscalculations of Nicholas Nalli. Available here.

[76] Nalli, N. Corrigendum to “Gunshot-wound dynamics model for John F. Kennedy assassination” [Heliyon 4 (2018) e00603], 10/1/2018. Available here.

[78] “JFK in Trauma Room One: The Missing Piece: Last Moments Before Death.” A YouTube video of Parkland Professor Marion T. Jenkins, MD discussing the assassination. This quote can be heard at and after the 5 minute, 25 second mark. Available here.

[79] Assassinations Records Review Board investigator, Doug Horne. “The Two Brain Memorandum.” Available here.

[80] See Doug Horne, “Questions Regarding Supplementary Brain Examination(s) Following the Autopsy on President John F. Kennedy.” ARRB Memorandum for file, 8/28/1996, revised 6.2.1998. Available here.