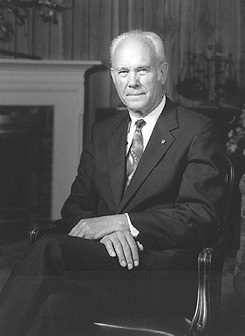

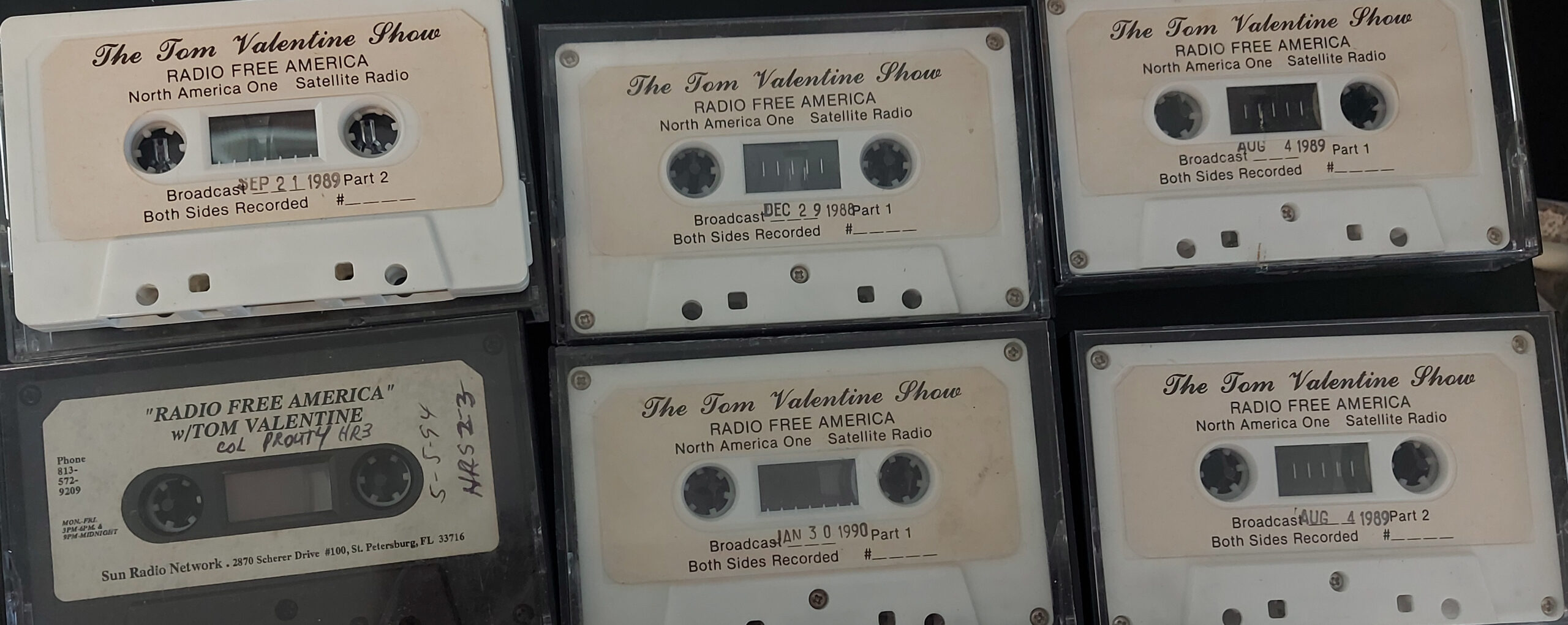

“This was the most important fallout of working on this movie JFK for me personally. As soon as we put into the movie the fact of history that John F. Kennedy had signed a White House paper, (a) National Security Action the highest most formal paper the executive branch could publish, number 263, it was dated 11 October 1963, in the month before he died. And that paper clearly said he was not going to put Americans into Vietnam. It went even further, in so many words it said that all American personnel were going to be out of Vietnam by the end of 1965. And the minute we put that into the script of the movie, even before the movie was made and put in the theaters, the newspapers and other pseudo-historians began to say ‘there’s no such thing. Prouty and Oliver Stone are wrong’.” (Col. Fletcher Prouty, May 5, 1994)

Prior to the release of Oliver Stone’s blockbuster film JFK, few people were aware of the implications contained within two policy directives generated about seven weeks apart in the autumn of 1963. These directives concerned American involvement in Vietnam, specifically crucial decisions regarding whether to expand or decrease the U.S. military’s role in the country’s future. The eventual decision to expand – massively – became one of the most polarizing events in American history–with consequential effect continuing to reverberate at the time of the release of Stone’s film in late 1991. The George H.W. Bush administration, for example, had been celebrating the supposed vanquishing of the “Vietnam Syndrome”, which had been lamented as a brake on the use of the military as a means of enforcing US foreign policies. With a presidential election looming in 1992, and the generation most directly affected by the Vietnam war fully coming into positions of influence, the dominant Cold War establishment, focused on global hegemony, was not interested in critical reassessments which might reveal cold calculation rather than tragic “mistakes”.

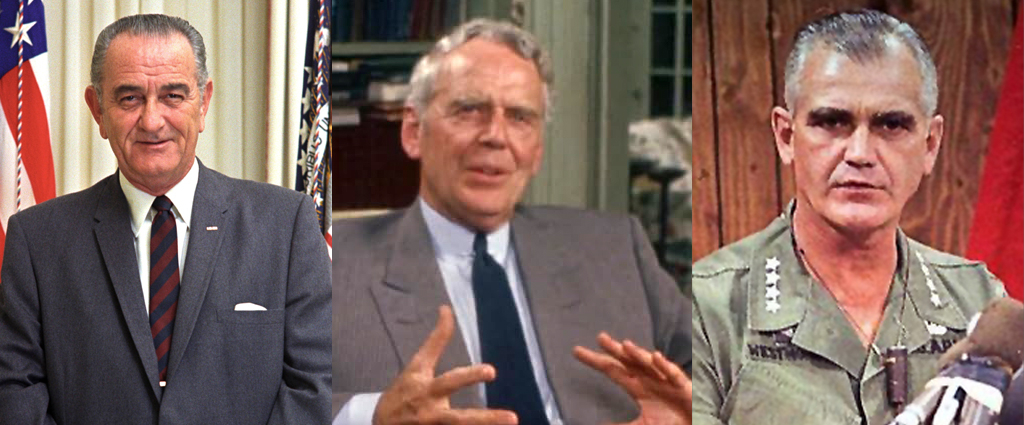

Retired Air Force Colonel L. Fletcher Prouty served as an advisor for Oliver Stone as the script for JFK was developed. Prouty was the key initial source influencing the insertion of information regarding the policy directive known as NSAM 263 into the film. While active in the Pentagon in 1963, Prouty had directly witnessed the development of the policy while serving under his boss, General Victor Krulak. Prouty’s later descriptive work on this subject, as it appeared across numerous essays and interviews, remains insightful, through its combination of personal experience with close readings of the documentary record.

Sixty years after the fact, the texts for NSAM 263 and 273 remain a controversial point of contention. Sharp differences regarding their actual meaning continue to influence the understanding of the historical record of the Vietnam war and both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations’ conduct of the war. On the occasion of Prouty’s birthday, and the 60th anniversary of JFK’s murder, it is useful to re-examine these policy initiatives through the work of Fletcher Prouty.

NSAM 263

Expressed interest in reducing U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, on behalf of the Kennedy administration, dates back at least as early as the spring of 1963. In a memorandum of discussions between Secretary of Defense McNamara and the Joint Chiefs held on April 29, 1963, McNamara is said to be “particularly interested in the projected phasing of US personnel strength” in Vietnam and the “feasibility of bringing back 1000 troops by the end of this year.”[1] McNamara specifically noted two aspects for consideration: “a) phased withdrawal of US forces, and b) a phased plan for South Vietnamese forces to take over functions now carried out by US forces.” Shortly thereafter, a high-level military meeting in Honolulu featured discussion along the same lines, and indicated that South Vietnam President Diem had already been advised of withdrawal plans.[2] McNamara at this time emphasized a withdrawal plan was necessary for purposes domestic and foreign “to give evidence that conditions are in fact improving”.[3] Both the withdrawal of 1000 troops by year’s end and a lengthier phased withdrawal based on training South Vietnamese to replace US personnel, were key elements of National Security Action Memorandum 263, which was certified as official policy little more than five months later.

For the Kennedy administration, Vietnam was an inherited problem. The partition of the country, the installation of Diem, the Viet Cong insurgency, and a growing U.S. “advisor” population was attributable to the influence of the Dwight Eisenhower era’s Dulles brothers combination at CIA (Allen) and the State Department (John Foster). In 1961 and 1962, crises in Berlin, Laos and Cuba were more immediately acute. However, in the summer of 1963, internal divisions and protests, exacerbated by South Vietnam President Diem’s harsh treatment of political dissenters and the huge Buddhist crisis, these called into question the near-term stability of his government. An American backed coup was contemplated in August, and then walked back, leaving unresolved divisions of power to percolate in an atmosphere intensified by the imposition of Diem’s approval of martial law.

At noon on August 26, 1963, with President Kennedy in attendance, a meeting was held at the White House to discuss pressing issues regarding Vietnam. At least fourteen such meetings were held from this date through October 11, when NSAM 263 was made official policy.[4] As head of the Pentagon’s Office for Counterinsurgency and Special Activities, General Krulak was assigned to attend most of those meetings. From his position in Krulak’s office, Prouty observed: “…such a full schedule in the White House, and with the President among other high officials in such a concentrated period is most unusual. It shows clearly Kennedy made an analysis of the Vietnam situation his problem, and it relates precisely the ideas he brought to the attention of his key staff on the subject.”[5]

The initial meetings dealt with the immediate political crisis in South Vietnam, and were concerned with the implications of a potential coup against Diem. It was hoped that a well-chosen approach or negotiation with Diem could isolate Ngo Dinh Nhu – the headstrong Diem brother deemed responsible for the current troubles, whose removal became the minimum requirement derived from these meetings. By September 6, the topics under discussion expanded to hard talk on the political realities in South Vietnam, whether the counter-insurgency programs could be successful with Diem remaining in power, and what should otherwise be done.[6] It was generally agreed a “reassessment” of Vietnam was necessary, and it was recommended that Krulak be sent to Vietnam to gather informed opinions at ground level.

Krulak left immediately and returned from Vietnam in time to appear at a White House meeting convened September 10.[7] Krulak reported the counter-insurgency effort was not too badly effected by the political crisis, and that the war against the Viet Cong “will be won if the current U.S. military and sociological programs are pursued.” Others disagreed, claiming success would not be possible short of a change in government. Kennedy called for another meeting the following day, and asked that “meeting papers should be prepared describing the specific steps that we might take in a gradual and selective cut of aid.” At that meeting, frank views across a spectrum of options were expressed. A following gathering, on September 12, continued to hone in on a precise description of “objectives and actions”, and the “pressures to be used to achieve these objectives.”[8]

Other than the unanimous resolve that Diem brother Nhu should be separated from the South Vietnamese government, the expression of opinions during this process could vary in emphasis and focus dependent on who the receiving party was. For example, in a draft letter to Diem at this time, Kennedy emphasized the need for frank discussion, while acknowledging “it remains the central purpose of the United States in its friendly relation with South Vietnam to defeat the aggressive designs of the Communists.”[9]Five days later, Kennedy would express in a memorandum to Robert McNamara: “The events in South Vietnam since May 1963 have now raised serious questions both about the present prospects for success against the Viet Cong and still more about the future effectiveness of this effort unless there can be important political improvement in the country.”[10] McNamara, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Maxwell Taylor, were about to be dispatched to Vietnam for an “on the spot appraisal of the military and paramilitary effort”.

McNamara and Taylor met with the President on the morning of September 23, just ahead of their departure. This was an unusual meeting on the Vietnam topic due to the small number of participants: four plus the President (previous meetings over the past month had featured at least a dozen, and upwards to twenty, partakers).[11] After Kennedy expressed his opinions on the most appropriate means of convincing Diem to heed to advice from American officials, Taylor referred to a “time schedule” for direct U.S. support of South Vietnam, similar to the theme expressed in late April / May by McNamara:

General Taylor thought it would be useful to work out a time schedule within which we expect to get this job done and to say plainly to Diem that we were which we expect to get this job done and to say plainly to Diem that we were not going to be able to stay beyond such and such a time with such and such forces, and the war must be won in this time period. The President did not say yes or no to this proposal.

The McNamara-Taylor trip to Vietnam occurred September 23rd to October 2nd, 1963. During this time, information pertaining to Vietnam generated by the White House meetings of the past month were being collated in Krulak’s office. According to Prouty, this was the work which appeared in a thick bound volume known as the McNamara-Taylor Trip Report, presented to Kennedy in the Oval Office on the officials’ return. Prouty maintained the contents reflected “precisely what President Kennedy and his top aides and officials were actually planning, and doing, by the end of 1963. This was precisely how Kennedy planned to ‘wind down’ the war.“[12] These “plans” appeared in the McNamara-Taylor Trip Report Memorandum, generated from the October 2 meeting with Kennedy, as specific recommendations to withdraw 1000 troops by year’s end, and to wind up direct U.S. involvement by end of 1965. Previously, in a missive to Diem dated October 1, Taylor had written: “… the primary purpose of these visits was to determine the rate of progress being made by our common effort toward victory over the insurgency. I would define victory in this context as being the reduction of the insurgency to proportions manageable by the National Security Forces normally available to your Government.”[13]

At a meeting of the National Security Council followed at 6PM on October 2, President Kennedy opened the meeting by summarizing what he considered the points of agreement on Vietnam policy going forward, as derived from the past weeks of concentration. “We are agreed to try to find effective means of changing the political atmosphere in Saigon. We are agreed that we should not cut off all U.S. aid to Vietnam, but are agreed on the necessity of trying to improve the situation in Vietnam by bringing about changes there.”[14]McNamara emphasized the “value” of the language on withdrawal of U.S. personnel as it answered domestic political criticism of being “bogged down” in Vietnam by revealing there was in fact a “withdrawal plan.” As well, “it commits us to emphasize the training of Vietnamese, which is something we must do in order to replace U.S. personnel with Vietnamese.” A Record of Action resulting from this NSC meeting noted, echoing Taylor’s words to Diem, “major U.S. assistance” was needed only until the insurgency had been either suppressed or until the national security forces of South Vietnam are capable of suppressing it.”[15]

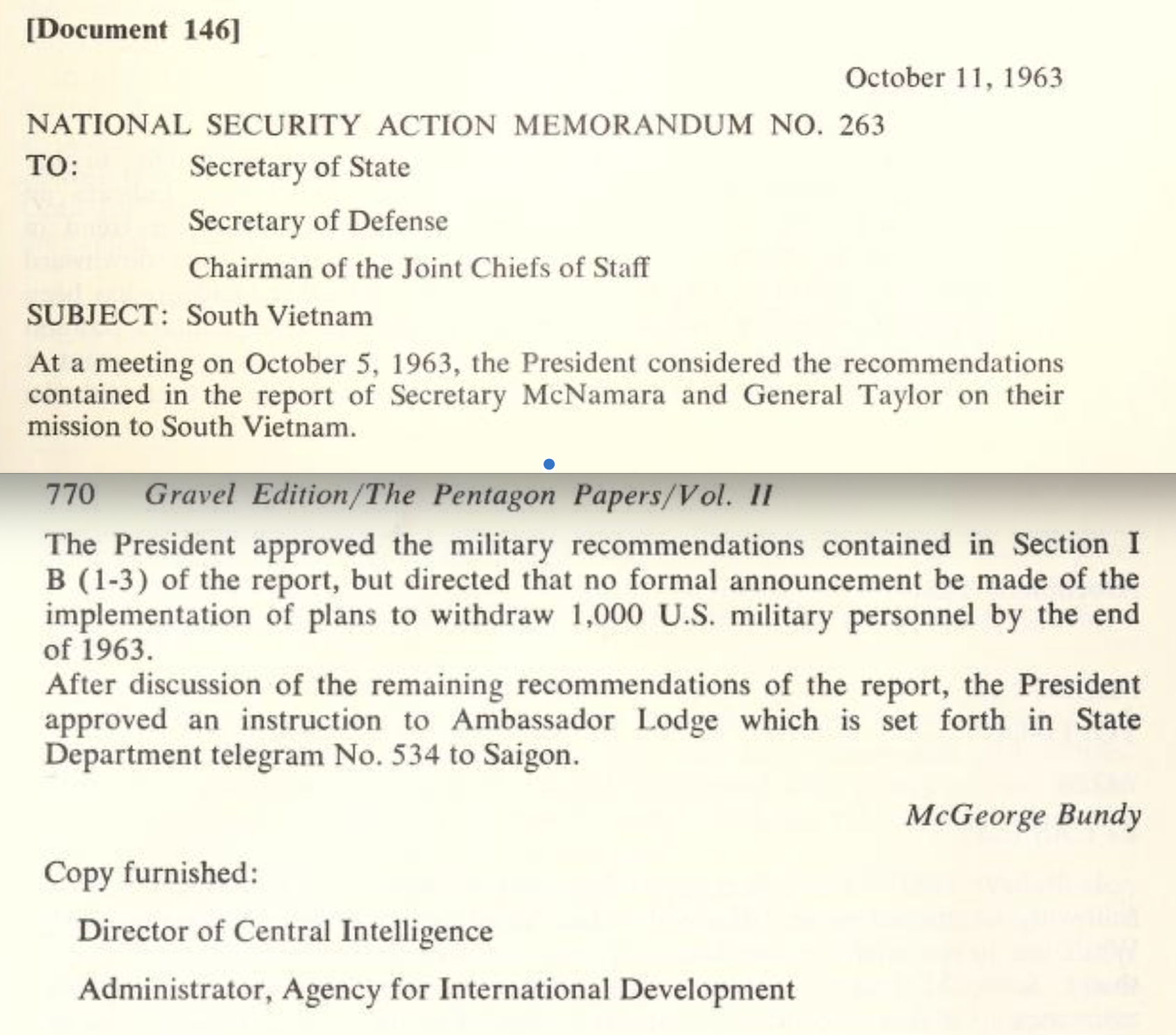

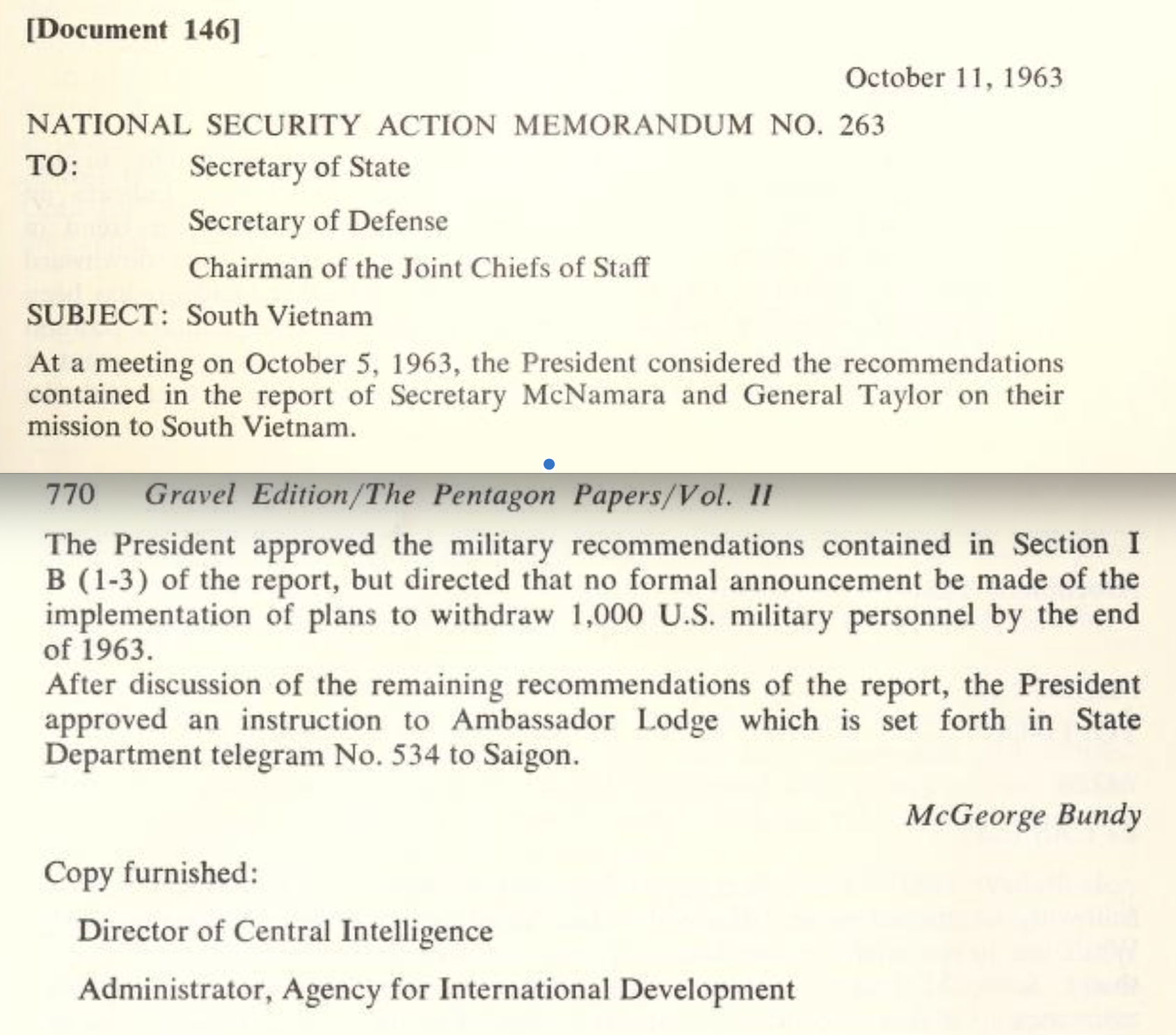

The official statement of U.S. national policy, National Security Action Memorandum No. 263, is dated October 11, l963.[16] It was typed on White House stationary and signed by Special Assistant to the President McGeorge Bundy. It records that President Kennedy approved “the military recommendations contained in Section 1 B (1-3) of the (Taylor McNamara) Report.”[17] The specified recommendations are:

- General Harkins review with Diem the military changes necessary to complete the military campaign in the Northern and Central areas by the end of 1964, and in the Delta by the end of 1965…

- A program be established to train Vietnamese so that essential functions now performed by U.S. military personnel can be carried out by Vietnamese by the end of 1965. It should be possible to withdraw the bulk of U.S. personnel by that time.

- In accordance with the program to train progressively Vietnamese to take over military functions, the Defense Department should announce in the very near future presently prepared plans to withdraw 1000 U.S. military personnel by the end of 1963. This action should be explained in low key as an initial step in a long-term program to replace U.S. personnel with trained Vietnamese without impairment of the war effort.

Antecedent and Context

In several of his essays, Prouty emphasized two important antecedents to the Kennedy administration’s Vietnam policies which culminated in October 1963 with NSAM 263. Both antecedents were related to operational programs run by the CIA, and both featured an expansion of scale during the period between Kennedy’s election and his inauguration.

The first involved the introduction of helicopter squadrons in response to “the worsening of internal security conditions in Viet Nam.” Described as an “emergency measure”, an initial total of eleven H-34 Sikorsky helicopters were requested December 1,1963.[18] As Prouty described:

“In December 1960 just after Kennedy’s election, Eisenhower’s National Security Council did direct the Defense Dept. to send a fleet of helicopters to Saigon under the operational control of the CIA …This was the situation Kennedy inherited by the time of his inaugural. It all happened between the election in Nov 1960 and the inaugural of Jan 1961.”[19]

The provision of the helicopters would require additional resources, as acknowledged by the JCS as they recommended the plan, including personnel attached to “ground support equipment” and “helicopter maintenance capability.”[20] In this way, the U.S. effort was bound to expand. Prouty:

“On Oct 30, 1963, there were 16,730 U.S. military personnel in Vietnam. A study performed at that time at the request of the senior military commander, General Harkins, revealed that barely 1,000 of them were in what might be called combatant roles.The rest were in such logistics tasks as helicopter maintenance, supply and training functions for the newly formed and unskilled Vietnamese armed forces.”[21](Ed. Note, by “might be called combatant roles” Prouty means Special Forces and combat advisors, since elsewhere he stated there was not one more combat troop in Vietnam when Kennedy died than when he took office.)

A few months after Kennedy’s inauguration, the Bay of Pigs invasion/uprising directed at Fidel Castro’s Cuba failed ignominiously. This CIA project had also notably expanded in scope during the lame duck period after Kennedy’s election. The fallout from this failure was magnified by the scale the project had accumulated, leaving a large number of persons directly affected and embittered. During the event, Kennedy had faced enormous pressure to escalate using US military assets directly, and a source of this pressure came from the clandestine milieu assembled by CIA’s regime-change program. Kennedy responded by creating a Cuban Study Group,[22] which was given two formal tasks:

a) to study our governmental practices and programs in the area of military and paramilitary, guerrilla and anti-guerrilla activity which fell short of outright war with a view to strengthening our work in this area.

b) and to direct special attention to lessons which can be learned from the recent events in Cuba.

The first task – to study clandestine “practices and programs” with the aim of “strengthening our work in this area” – resulted in two National Security Action Memoranda which foreshadowed some of the policy directives later applied to Vietnam. These policies would represent a direct challenge to the CIA’s control over covert activity, as established by Allen Dulles during the Eisenhower administration. Prouty identified a moment during the Study Group’s May 10, 1961 interview with Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, Dulles’ immediate predecessor as Director of Central Intelligence, as articulating the need for a new direction. Prouty:

“This meeting with General Smith emphasized the direction that President Kennedy and his closest advisors were taking on the two related subjects: the future of the CIA and of the warfare in Vietnam. Both were going to be put under control, and ended…at least as they had been administered up to that time.”[23]

Question: Should we have intelligence gathering in the same place that you have operations?

General Smith: I think so much publicity has been given to CIA that the covert work might have to be put under another roof.

Question: Do you think you should take the covert operations from CIA?

General Smith: It’s time we take the bucket of slop and put another cover over it.

Taylor submitted an 81-page report on the Bay of Pigs to Kennedy on June 13, 1961. Two weeks later, on June 28, NSAM 55 was signed and disseminated. Its subject was “Relations of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to the President in Cold War Operations” ( Prouty identified the phrase “Cold War Operations” as a reference to Clandestine Operations).[24]As delivered directly to the Chairman of the JCS Lyman Lemnitzer, the document began:

a) I regard the Joint Chiefs of Staff as my principal military advisor responsible both for initiating advice to me and for responding to requests for advice. I expect their advice to come to me direct and unfiltered.

b) The Joint Chiefs of Staff have a responsibility for the defense of the nation in the Cold War similar to that which they have in conventional hostilities…”.

Kennedy clearly felt that the Pentagon had let him down in their advice on the Bay of Pigs operation and that the CIA had lied to him. Because this was a distinct change in direction from the Eisenhower administration’s National Security Council directive 5412 (1954), which designated responsibility for clandestine or covert operations (Cold War Operations) to the CIA. Kennedy was redirecting this responsibility to the Department of Defense.[25]A subsequent memorandum, NSAM 57, was drafted with the subject heading: “Responsibility for Paramilitary Operations”. This document outlined a more detailed breakdown of responsibilities:

Where such an operation (clandestine) is to be wholly covert or disavowable, it may be assigned to CIA, provided that it is within the normal capability of the agency.

Any large paramilitary operation wholly or partly covert which requires significant numbers of militarily trained personnel, amounts of military equipment which exceed normal CIA-controlled stocks and/or military experience of a kind and level peculiar to the Armed Services is properly the primary responsibility of the Department of Defense with the CIA in a supporting role.

Examples of “large paramilitary” operations run by the CIA would, from the vantage of the summer of 1961, include the inconclusive Indonesia campaign from 1958 and the disastrous Bay of Pigs a few months before. However, this description would also apply to the CIA’s ongoing operations in Vietnam, which were then expanding, beginning with the infusion of the helicopters. In his discussions of this policy statement, Prouty made note of specific differentiating language appearing in NSAM 263, identifying separately “U.S. military personnel” followed by “U.S. personnel”. Prouty averred this distinction was deliberate, that the term “U.S. personnel” referenced in particular the ongoing CIA programs operational in Vietnam. In this way, NSAM 263 had continuity with the earlier policy developed after the Bay of Pigs, intended to shift responsibilities for covert paramilitary operations from the CIA to the Defense Department, and to reduce their scope.

NSAM 273

On November 6, 1963 Kennedy sent an Eyes Only telegram to Ambassador Lodge, referring to “a new Government which we are about to recognize.” South Vietnam’s President Diem had suffered a coup, resulting in his, and his brother’s, death, a few days before. While the coup had been tacitly accepted in advance (although not anticipating loss of life), there were attendant loose ends and adjustments requiring attention as Kennedy referred: “I am sure that much good will come from the comprehensive review of the situation which is now planned for Honolulu, and I look forward to your own visit to Washington so that you and I can review the whole situation together and face to face.”[26]

On November 13, the upcoming meeting in Honolulu was discussed at the daily White House staff meeting.[27] Kennedy’s Special Assistant for National Security McGeorge Bundy, who would attend the meeting, was briefed on what to expect by his assistant Michael Forrestal: “From what I can gather, the Honolulu meeting is shaping up into a replica of its predecessors, i.e. an eight-hour briefing conducted in the usual military manner. In the past this has meant about 100 people in the CINCPAC Conference Room, who are treated to a dazzling display of maps and charts, punctuated with some impressive intellectual fireworks from Bob McNamara.”[28] The Record of Discussion also notes: “When someone asks Bundy why he was going, he replied that he had been instructed.”[29]

The autumn Honolulu Conference was held on November 19-20. The summary of discussion which begins the official Memorandum expresses optimism: “Ambassador Lodge described the outlook for the immediate future of Vietnam as hopeful. The Generals appear to be united and determined to step up the war effort. They profess to be keenly aware that the struggle with the Viet Cong is not only a military program, but also political and psychological. They attach great importance to a social and economic program as an aid to winning the war.”[30]

This optimism carries over to the summary’s concluding views, which reflect the policy articulated in NSAM 263:

“Finally, as regards all U.S. programs – military, economic, psychological – we should continue to keep before us the goal of setting dates for phasing out U.S. activities and turning them over to the Vietnamese; and these dates, too, should be looked at again in the light of the new political situation. The date mentioned in the McNamara-Taylor statement on October 2 on U.S. military withdrawal had and is still having – a tonic effect. We should set dates for USOM and USUS programs, too. We can always grant last-minute extensions if we think it wise to do so.”[31]

The New York Times published a briefing on the Honolulu Conference on November 21, 1963 (datelined November 20). Titled “U.S. Aides Report Gain, 1,000 Troops to Return”, and said to be reflecting “assessments” from the “first full-scale review of the Vietnamese situation since the military coup”, the brief report “reaffirmed the United States plan to bring home about 1,000 of its 16,500 troops from South Vietnam by Jan 1.”

The decision to remove these troops was made in October after a mission to South Vietnam by Secretary McNamara and Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who also attended today’s conference. Officials indicated that although there were no basic changes in United States policies and commitments to South Vietnam, the conference would probably recommend some modifications in American aid programs in an effort to intensify the campaign against the Vietcong guerrillas.” [32]

McGeorge Bundy attended sessions of the Honolulu Conference on November 19 and 20, and then boarded a plane headed back to Washington either very late on the evening of November 20 or very early on November 21. Defense Secretary McNamara was on the same flight, which landed in D.C. after Kennedy’s Presidential party had already left for Texas. Briefings scheduled for President Kennedy regarding discussions in Honolulu were to be held after his return from Texas. Bundy authored the first draft of National Security Action Memorandum 273 on November 21, perhaps on the plane. Kennedy, of course, was killed the following day. There is no indication that Kennedy received any direct reports on the discussions in Honolulu, although he may have seen the New York Times article. Regardless, the draft penned by Bundy on November 21 anticipates a result:

The President has reviewed the discussions of South Vietnam which occurred in Honolulu, and has discussed the matter further with Ambassador Lodge. He directs that the following guidance be issued to all concerned:

1. It remains the central object of the United States in South Vietnam to assist the people and Government of that country to win their contest against the externally directed and supported Communist conspiracy. The test of all decisions and U.S. actions in this area should be the effectiveness of their contribution to this purpose.

2. The objectives of the United States with respect to the withdrawal of U.S. military personnel remain as stated in the White House statement of October 2, 1963…”[33]

The difference within this draft, as compared to the language of NSAM 263, is alluded in these first two sections. The second section, for example, affirms the “withdrawal of U.S. military personnel” (1,000 by the end of the year) will remain policy (emphasis added), while the absence of reference to the corresponding withdrawal of the “bulk of U.S. personnel” by 1965 infers, by its omission, that this facet of the withdrawal plan does not, as a policy, remain. This omission is also relevant to the first section, which differs from NSAM 263 by situating US Vietnam policy as primarily concerned with assisting South Vietnam “win their contest” versus the North (and therefore primarily focused on the “effectiveness” of the U.S. effort to do so), whereas NSAM 263’s primary concern was transferring the “essential functions” of the war effort to South Vietnam in the interests of removing U.S. personnel altogether. This revision is also misrepresented as the continuation of previous policy, as the opening words assert “it remains the central object…” (emphasis added)

This crucial difference, moreover, does not find articulation in the official Memorandum on the Honolulu Conference, which instead notes that deadlines for turning U.S. activities over to the Vietnamese were exhibiting a “tonic effect”. It is neither mentioned in the New York Times article dated November 20, based on an official briefing, which flatly states there were “no basic changes in United States policies and commitments to South Vietnam.”

Prouty, having worked under Krulak throughout September 1963 assembling the information apprising the Taylor-McNamara Trip Report, working from direction they understood as Kennedy’s himself, was skeptical of NSAM 273’s provenance:

Strangely, this NSAM #273, which began the change in Kennedy’s policy toward Vietnam, was drafted on Nov 21, 1963…the day before Kennedy died. It was not Kennedy’s policy. He would not have requested it, and would not have signed it. Why would it have been drafted for his signature on the day before he died; and why would it have been given to Johnson so quickly after Kennedy died? Johnson had not asked for it. On Nov 21, 1963 Johnson had no expectation whatsoever of being President…”[34]

“We have the full record of the development of Kennedy’s Vietnam policy in the Foreign Relations of the United States series, 1961-1963 Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963. There can no question of that policy as formally approved on Oct 11, 1963, and that the draft of NSAM #273 was the beginning of a change of that policy, and of the enormous military escalation in Vietnam much to the satisfaction of the military industry complex…Who could have known, before Kennedy died, that he intended to begin an escalation of the warfare in Vietnam contrary to his decision of Oct. 11th? Someone wanted to make it appear that he did. Thus this National Security Action Memorandum with its origin before his death. Or should the question be, ‘Did those connected with the creation of this document know – ahead of time – that Kennedy was scheduled to die?’ This is a measure of the pressures of that time.”[35]

Prouty believed, based on having seen numerous copies of the November 21 draft, that it was relatively widely distributed across the senior layers of the national security apparatus. A cover note attached to a copy distributed to Bundy’s brother William, a deputy within the Defense Department, asks him to review and also consult on the draft with McNamara.[36] The draft also appears to have been distributed on November 23 to newly appointed President Johnson, ahead of a meeting with Ambassador Lodge scheduled for the following day which, in an instance of macabre irony, had already been anticipated in the draft’s opening sentence: “the President…has discussed the matter further with Ambassador Lodge”.[37] A State Department Briefing Paper put together for Johnson ahead of the same meeting refers to a “draft National Security Action Memorandum emerging from the Honolulu meeting, which Mr. Bundy has initiated.” (Emphasis added).[38]

Prouty believed, based on having seen numerous copies of the November 21 draft, that it was relatively widely distributed across the senior layers of the national security apparatus. A cover note attached to a copy distributed to Bundy’s brother William, a deputy within the Defense Department, asks him to review and also consult on the draft with McNamara.[36] The draft also appears to have been distributed on November 23 to newly appointed President Johnson, ahead of a meeting with Ambassador Lodge scheduled for the following day which, in an instance of macabre irony, had already been anticipated in the draft’s opening sentence: “the President…has discussed the matter further with Ambassador Lodge”.[37] A State Department Briefing Paper put together for Johnson ahead of the same meeting refers to a “draft National Security Action Memorandum emerging from the Honolulu meeting, which Mr. Bundy has initiated.” (Emphasis added).[38]

A second draft of the proposed NSAM 273 was composed on November 24. Changes in the draft were notable in paragraph 7, which originally discussed “the development of additional Government of Vietnam resources” to be used for “action against North Vietnam.” The revision appeared to address kinetic activity generated directly by U.S. forces, in accord with established covert protocols (i.e. the “plausibility of denial”).[39]

A second draft of the proposed NSAM 273 was composed on November 24. Changes in the draft were notable in paragraph 7, which originally discussed “the development of additional Government of Vietnam resources” to be used for “action against North Vietnam.” The revision appeared to address kinetic activity generated directly by U.S. forces, in accord with established covert protocols (i.e. the “plausibility of denial”).[39]

That same day, the anticipated meeting to discuss the South Vietnam situation was held, with LBJ, Rusk, McNamara, Ball, Lodge, McCone and Bundy in attendance.[40] This briefing for the President, focused on recommendations and updates, it represents – other than the one thousand man withdrawal slated for year-end – the internment of Kennedy’s Vietnam policies as developed in NSAM 263. Ambassador Lodge, for example, suggested that talk of a 1965 withdrawal – or “indication” thereof – was merely a negotiating ploy: “Lodge stated that we were not involved in the coup, though we put pressures on the South Vietnamese government to change its course and those pressures, most particularly on indications of withdrawal by 1965, encouraged the coup.” If ever there was a piece of high level CYA, this was it for, as James Douglass shows, Lodge was actually guiding the Diem brothers to their deaths.

CIA Director John McCone, contradicting the conclusions delivered in Honolulu to the press, said the situation was “serious” and the paucity of optimism regarding the future of South Vietnam was evidenced by large increases in Viet Cong attacks and their advanced preparations for more. For his part, LBJ expressed misgivings with poor handling of controversial situations in the country, exacerbated by internal bickering. He rejected the idea that “we had to reform every Asian in our own image” in reference to political and economic strategies discussed in Honolulu. “(Johnson) was anxious to get along, win the war – he didn’t want as much effort placed on so-called social reforms…”

“The meeting was followed by a statement to the press which was given out by Bundy to the effect we would pursue the policies agreed to in Honolulu adopted by the late President Kennedy.” This statement was given prominence in a New York Times report published November 25, 1963 (datelined Nov 24) entitled “Johnson Affirms Aims in Vietnam, Retains Kennedy’s Policy of Aiding War on Reds”. The opening sentence, presumably echoing Bundy: “President Johnson reaffirmed today the policy objectives of his predecessor regarding South Vietnam.” This reporting features the first three paragraphs of what would be published as NSAM 273 two days later, including the iteration that the “central point of U.S. policy on South Vietnam remains; namely, to assist the new government there in winning the war against the Communist Vietcong insurgents.” There is also a discussion of the political and economic measures advocated at Honolulu, but downplayed by Johnson shortly before (which is not mentioned), as well as the need for unity within the U.S. bureaucracy assigned in support South Vietnam.[41]

On November 26, 1963, National Security Action Memorandum No. 273 was signed by McGeorge Bundy and updated NSAM 263 in United States official policy for South Vietnam.[42] Kennedy’s policy of effecting the removal of all “U.S. personnel” (i.e. military and CIA) from South Vietnam by the end of 1965, clearly referenced during conversations held at the Honolulu Conference, had been essentially erased from memory, even as NSAM 273 and its components were being described as a continuation of, or consistent with, Kennedy’s policies. The intent is now to win the war. Prouty:

On November 26, 1963, National Security Action Memorandum No. 273 was signed by McGeorge Bundy and updated NSAM 263 in United States official policy for South Vietnam.[42] Kennedy’s policy of effecting the removal of all “U.S. personnel” (i.e. military and CIA) from South Vietnam by the end of 1965, clearly referenced during conversations held at the Honolulu Conference, had been essentially erased from memory, even as NSAM 273 and its components were being described as a continuation of, or consistent with, Kennedy’s policies. The intent is now to win the war. Prouty:

“Two months later, January 22,1964, one of the same authors of NSAM #263, General Maxwell Taylor, wrote to the Secretary of Defense, McNamara: ‘The Joint Chiefs of Staff consider that the United States must: (i) commit additional U.S. forces, as in support of the combat action within South Vietnam, and (j) commit U.S. forces as necessary in direct actions against North Vietnam.’

These were the same two top level officials who under JFK had gone along with the Kennedy plan for the withdrawal of U.S. men. Then, less than 3 months later, under LBJ, they made totally different recommendations. The only difference was that President Kennedy was against escalation and wanted the men home, and Kennedy had never approved at any time the introduction of combat soldiers under U.S. military commanders for combat purposes in Vietnam. President Johnson, with George Ball in a top position, was doing just the opposite.”[43]

That was how fast Johnson’s militant position infected Kennedy’s advisors.

What many consider the true milestone on the road to an American war, NSAM 288, was approved in March, based on recommendations generated from yet another review of South Vietnam’s national security situation, presented by McNamara (working from an initial draft written by Bundy). Among the recommendations: a pledge to “furnish assistance and support to South Vietnam for as long as it takes to bring the insurgency under control”; to put South Vietnam on a “war footing”; to increase and upgrade Air Force, Army, and Naval heavy equipment; to prepare “hot pursuit”, “Border Control”, “Retaliatory Actions”, and “Graduated Overt Military Pressure” against North Vietnam.[44] By August, the increased tempo of activities supported by U.S. military assistance had created the Tonkin Gulf incident, and the inevitable slide to a shooting war. Prouty:

“By March 1964 the U.S. approach to the situation in Vietnam had changed 180 degrees from the Kennedy policy of NSAM #263 and on March 17, 1964, President Johnson signed NSAM #288 which broadly expanded U.S. policy. About one year later, March 8, 1965, the first U.S. Marines operating under Marine commanders invaded South Vietnam at Da Nang. This was the true beginning of military action in Vietnam.”[45]

What Kennedy had not done in three years, Johnson had done in three months.

Obfuscation of NSAM 263

On January 6, 1992, the New York Times published an opinion piece by Leslie Gelb titled “Kennedy and Vietnam”. Gelb could be described as the consummate Washington insider, with a c.v. laden with high-profile appointments across government, think tanks, and the media, specializing in foreign affairs. In the late 1960s, Gelb served as the director of the so-called Pentagon Papers project, leading the team of analysts in setting down an extensive history of the Vietnam War. Gelb’s authority to criticize premises expressed in Oliver Stone’s then current blockbuster film JFK ensured his opinions would hold some influence in the culture at large.

In the piece, Gelb angrily accuses Stone (and by extension Prouty) of distorting the record of NSAM 263 and making “swaggering assertions about mighty unknowns.” Gelb claims of NSAM 263 that “some officials took the directive at face value”, but “most” saw it as a “bureaucratic scheme” to fudge the numbers of in-country personnel. He argues that “whatever JFK’s precise intentions” or “underlying thinking”, it was best to understand them as malleable and subject to changing circumstances and complications. Gelb ends his piece with an appeal to recognize the burden of the Presidency, particularly as involved Vietnam: the “private soul-searching” of Eisenhower, the “documented dilemmas ” and “torments” of Johnson and Nixon, matched by the “murky” musings represented by Kennedy’s occasional contradictory public statements. Stone (and Prouty) are therefore attacked for their “foolish” confidence over “decisions J.F.K. would have made in circumstances he never had to face.”[46] Prouty responded:

“It is almost beyond belief that (Gelb)… in 1992, finds it easier to say that this was a decision ‘he never had to face’ instead of telling it as it is – the reason ‘he never had to face’ that decision was because he had been assassinated.”[47]

The one specific reference Gelb uses to respond to the supposed misrepresentations which had him so vexed, is itself distorted with some lawyerly spin: “Most officials also viewed the withdrawal memo as part of a White House ploy to scare President Diem of South Vietnam into making political reforms…That is precisely how the State Department instructed the U.S. Embassy in Saigon to understand NSAM 263.” What Gelb is referring to (and this became a talking point for other critics as well), is a State Department telegram to Lodge’s Vietnam embassy dated October 5, 1963.[48] While this communication is cited within the body of NSAM 263, it appears as an item of business separate from the primary matters, namely the planned withdrawal of “1000 U.S. military personnel” and the intention of withdrawing “the bulk of U.S. personnel” by the end of 1965.[49]

The one specific reference Gelb uses to respond to the supposed misrepresentations which had him so vexed, is itself distorted with some lawyerly spin: “Most officials also viewed the withdrawal memo as part of a White House ploy to scare President Diem of South Vietnam into making political reforms…That is precisely how the State Department instructed the U.S. Embassy in Saigon to understand NSAM 263.” What Gelb is referring to (and this became a talking point for other critics as well), is a State Department telegram to Lodge’s Vietnam embassy dated October 5, 1963.[48] While this communication is cited within the body of NSAM 263, it appears as an item of business separate from the primary matters, namely the planned withdrawal of “1000 U.S. military personnel” and the intention of withdrawing “the bulk of U.S. personnel” by the end of 1965.[49]

Prouty’s issues with Gelb extended beyond the latter’s simplistic denial that Kennedy was just “going to abandon South Vietnam to a communist takeover.” Gelb’s previous role as director of the “Pentagon Papers” project could not be overlooked. Prouty:

Prouty’s issues with Gelb extended beyond the latter’s simplistic denial that Kennedy was just “going to abandon South Vietnam to a communist takeover.” Gelb’s previous role as director of the “Pentagon Papers” project could not be overlooked. Prouty:

“However it was in the ‘Pentagon Papers’ that the intrigue to distort and misrepresent major episodes of the Kennedy era began. Pre-eminent among these distortions is the Pentagon Papers presentation of the NSAM #263 record. What was done was quite simple, and effective. The title, ‘National Security Action Memorandum No. 263’ appears as Document #146 on page 769 in Volume II of the Gravel Edition, i.e. Congressional Record. But, this is published as only three, single-sentence paragraphs of non-substantive material with no cross referencing. This is like publishing the envelope; but not the letter.”[50]

This is a good point. While NSAM No. 263, as it appears on pp 769-770 of the Gravel Edition (Vol.II), is accurately transcribed from the original, the presentation, lacking cross reference, is opaque.[51] Since McGeorge Bundy’s original wording is not precise, in that it dates the discussion of the crucial McNamara-Taylor report (October 5, 1963) but doesn’t attribute identifiers to the report itself (dated October 2, 1963), the reader is either left to their own devices to put the pieces together, or must remember to consult a lengthy Chronology which appears some 550 pages previous. Prouty:

Those few who already know what a true-copy of NSAM #263 looked like will find that the ‘Memorandum For The President’ that is the McNamara-Taylor Trip Report of Oct. 2, 1963 appears as Document 142 on page 751 through 766 with no reference to NSAM #263 whatsoever. This may be why so many ‘historians’ and other writers remain unaware of this most important policy statement.[52]

The Chronology in Vol. II of the Pentagon Papers begins May 8, 1963 and concludes on November 23, 1963.[53] The Report of the McNamara-Taylor mission appears as a listing for October 2, 1963 (p216). In the brief description, the withdrawal of “1,000 American troops by year’s end” is noted, but there is no mention of the recommendation to withdraw “the bulk of U.S. personnel” by the end of 1965. The publication of NSAM 263 as an official document, October 11, 1963, is not listed.

The Chronology in Vol. II of the Pentagon Papers begins May 8, 1963 and concludes on November 23, 1963.[53] The Report of the McNamara-Taylor mission appears as a listing for October 2, 1963 (p216). In the brief description, the withdrawal of “1,000 American troops by year’s end” is noted, but there is no mention of the recommendation to withdraw “the bulk of U.S. personnel” by the end of 1965. The publication of NSAM 263 as an official document, October 11, 1963, is not listed.

The Chronology’s concluding three items feature a description of the Honolulu Conference (20 November 1963), which observes a press release “gives few details but does reiterate the U.S. intention to withdraw 1,000 troops by the end of the year.” That the press release also indicated “no basic changes to U.S. policies” is not mentioned. Then, incongruously, the Chronology concludes:

22 Nov 1963: Lodge confers with the President Having flown to Washington the day after the Conference, Lodge meets with the President and presumably continues the kind of report given in Honolulu.

23 Nov 1963: NSAM 273

Drawing together the results of the Honolulu Conference and Lodge’s meeting with the President, NSAM 273 reaffirms the U.S. commitment to defeat the VC in Vietnam

Neither of these final two items actually occurred as described. Lodge did not meet with either President Kennedy or newly sworn-in President Johnson on November 22, the day on which President Kennedy was assassinated. NSAM 273 was not made official on November 23, and the specific meeting pertaining to the document was not held until the following day. Prouty:

Neither of these final two items actually occurred as described. Lodge did not meet with either President Kennedy or newly sworn-in President Johnson on November 22, the day on which President Kennedy was assassinated. NSAM 273 was not made official on November 23, and the specific meeting pertaining to the document was not held until the following day. Prouty:

“NSAM 273 was signed by President Johnson on Nov. 26, 1963. It must be noted, that until an NSAM is approved and signed it does not have a formal number; therefore the subject matter that Lodge and Johnson conferred about could not have been designated NSAM #273 on the 23rd of Nov. 1963.”[54]

Conclusion

A separate attack on Oliver Stone’s JFK movie, published by the New York Times during the film’s initial release, was written by Tom Wicker.[55] Prouty’s response to this piece provides a good summary of his position:

(Tom Wicker) also attacked Stone’s use of Kennedy’s Vietnam policy statement, NSAM #263, with the comment, ‘I know of no reputable historian who has documented Kennedy’s intentions.’ NSAM #263 is the official and complete documentation of Kennedy’s intentions. It was derived from a series of White House conferences and from the McNamara-Taylor Vietnam Trip Report, and it stated the views of the President and of his closest advisers as is made clear in the U.S. government publication Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-1963, Vol. IV, ‘Vietnam: August-December 1963’. That source is reliable history. Wicker’s December 15, 1991, Times article was a lengthy and unnecessarily demeaning diatribe against Stone and his movie…

The inclusion of this little-known NSAM #263 in the film became the principal point of attack of the big guns that were leveled at Stone, Garrison, and myself. It really is amazing that the most vitriolic attacks were those that attempted to inform the public that there was no such directive. The furor over that one item, NSAM #263, was evidence that Stone had hit his target. This alone uncovered the ‘Why?’ of the assassination.[56]

Prouty’s insights pertaining to National Security Action Memorandums numbers 263 and 273 remain vitally important to understanding the development of Kennedy’s Vietnam policy. It is clear that the recommendations described in NSAM 263 were the result of a period of concentrated attention directed by the President. It is much less clear what motivated McGeorge Bundy to draft what became NSAM 273, and how it was that the changes to the earlier document initiated by 273 were long described as representing continuity with Kennedy’s policies. Clearing the web of obfuscation over these directives, as begun in Stone’s JFK, provides clarity to the historical record.

The Vietnam War, with its intensive U.S. military commitments, proved a massive disaster for the people of Southeast Asia and the American public, although it remains often officially portrayed as a “tragic” event borne of circumstance and not design. As well, the missed opportunity to rein in the CIA’s operational capabilities opened the door to ever larger corrupt cynical undertakings such as Iran-Contra and Timber Sycamore, with the clandestine services’ lack of accountability ever more entrenched. The documented record strongly infers that Kennedy’s potential re-election in 1964, as a “what-if?”, would have been consequential.

Bibliography:

L. Fletcher Prouty, Collected Works. CD-ROM

www.prouty.org

Notes

[1] JCS – Sec Def Discussions April 29, 1963 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=144

[2] JCS Official File. May 6, 1963. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=122#relPageId=47

[3] ibid https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=122#relPageId=115

[4] The concentrated interest in Vietnam policy during these months is recorded in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1963, vol 3 Vietnam: January-August 1963 & vol. 4 Vietnam: August-December 1963, assembled by the Department of State and published by the U.S. Government Printing Office, 1991 https://www.maryferrell.org/php/showlist.php?docset=1036

[5] Prouty, JFK: New Preface, 1996. Collected Works

[6] FRUS Vol. 4, p117. 66. Memorandum of a Conference with the President, White House, September 6, 1963 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=143

[7] FRUS Vol. 4, p 161. 83. Memorandum of a Conversation, White House, September 10, 1963 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=187

[8] FRUS Vol. 4, p199, Memorandum for the Record of a Meeting, White House, September 12, 1963 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=225

[9] FRUS Vol. 4, p231, Draft Letter from President Kennedy to President Diem, September 16, 1963. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=257

[10] This document would also be described as “draft instructions” from the President for McNamara to guide his upcoming trip to Vietnam with General Taylor. FRUS Vol. 4, p 278. 142. Memorandum from the President to the Secretary of Defence (McNamara) September 21,1963. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=304)

[11] FRUS Vol. 4, p 280. Memorandum for the Record of a Meeting, White House, September 23, 1963. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=306

[12] Prouty, The Highly Significant Role Played By Two Major Presidential Policy Directives, 1997. Collected Works. Prouty does make the point that neither McNamara or Taylor would have had the time or resources to compose let alone print the volume seen in photographs from October 2.

[13] Taylor also wrote: “I am convinced that the Viet Congress insurgency in the north and center can be reduced to little more than sporadic incidents by the end of 1964. The Delta will take longer but should be completed by the end of 1965.” FRUS Vol. 4, p 328. Letter From the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Taylor) To President Diem, October 1, 1963. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=354

[14] FRUS Vol. 4, p 350. 169. Summary Record of the 519th Meeting of the National Security Council, White House, October 2, 1963. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=376

[15] FRUS Vol. 4, p 353. 170. Record of Action No 2472, Taken at the 519th Meeting of the National Security Council, October 2, 1963. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=379

[16] Item 194 Foreign Relations of the United States 1961-1963 Vol. IV p395 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=421)

[17] Item 167 Memorandum from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Taylor) and the Secretary of Defense (McNamara) to the President, October 2, 1963 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=362)

[18] Foreign Relations of the United States 1958-1960, Vietnam Vol 1. p705 Item 255. Special Staff Note Prepared by Department of Defense.

[19] Prouty, The Hidden Role of Conspiracy, 1993. Collected Works “(Kennedy) inherited it and revisionist historians have saddled him with the ‘Vietnam build-up’ and the ‘creation of the Special Forces’ ever since.”

[20] Foreign Relations of the United States 1958-1960, Vietnam Vol 1. P703 Item 254. Memorandum From the Joint Chiefs of Staff to the Secretary of Defense (Gates)

[21] Prouty, 30th Anniversary of Coup, 1994. Collected Works

[22] The members of this Group were General Maxwell Taylor, Admiral Arleigh Burke, CIA director Allen Dulles, and Robert Kennedy representing the Executive

[23] Prouty, 30th Anniversary of the Coup, 1994, Collected Works

[24] copies of NSAM 55-57 as saved in Prouty’s own files can be found at https://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/USO/appE.html

[25] “When I read to (Chiefs of Staff) President Kennedy’s statement from NSAM #55…you could have heard a pin drop in the ‘Gold Room’. They had never been included in the special policy channel which Allen Dulles had perfected over the past decade, that ran from the National Security Council (NSC) to the CIA for all clandestine operations.” Prouty The Highly Significant Role Played By Two Major Presidential Policy Directives 1997. Collected Works

[26] Item 304 Telegram from the Department of State to the Embassy in Vietnam November 6, 1963. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=605

[27] Item 312 Memorandum for the Record of Discussion at the Daily White House Staff Meeting, Washington, November 13, 1963 8 a.m. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=619

[28] Memorandum to Mr Bundy https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=146534#relPageId=6

[29] That might infer he was instructed specifically by President Kennedy, but his reply as recorded does not actually clarify who had so instructed. Since Bundy was the author of NSAM 273, such instruction might explain the how’s and why’s of the original draft, dated November 21, which Bundy later described as drafted “for the President”. The record, however, nowhere indicates any instruction or dialogue involving Kennedy seeking revision to NSAM 263, which had been drafted only weeks previously.

[30] FRUS Vol. 4, p 608 Item 321 Memorandum of Discussion at the Special Meeting on Vietnam, Honolulu November 20, 1963 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=634

[31] FRUS Vol. 4, p 610 Item 321 Memorandum of Discussion at the Special Meeting on Vietnam, Honolulu November 20, 1963 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=636

[32] U.S. Aides Report Gain,1,000 Troops to Return New York Times November 21, 1963, p8

[33] a copy of the draft, along with John Newman’s discussion of it can be found here: https://jfkjmn.com/new-page-77/

[34] Prouty, Hidden Role of Conspiracy,1993, Collected Works

[35] Prouty The Highly Significant Role Played by Two Major Presidential Policy Directives 1997. Collected Works

[36] “I have other copies of this draft document that were done on various typewriters and they certainly indicate that this draft document had to have been quickly circulated through all of the highest governmental levels…on the 21st. On these draft copies there are some notes, and line outs.” Also: “in this original draft that he circulated among many of the top echelons of the Government, with personal “Cover Letters” to the Director of Central Intelligence, John McCone and to his brother William in McNamara’s office…” Prouty The Highly Significant Role Played By Two Major Presidential Policy Directives 1997. Collected Works

[37] Item 324. Memorandum From the Secretary of Defense (McNamara) to the President https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=653

[38] Item 326 Briefing Paper Prepared in the Department of State for the President, November 23, 1963 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=657

[39] The first draft of NSAM 273, and a brief discussion of it, can be accessed on scholar John Newman’s site https://jfkjmn.com/new-page-77/. In an interview, McGeorge Bundy explained to Newman his first draft approach to paragraph 7: “he tried to bring these recommendations ‘in line with the words Kennedy might want to say.’” Which, considering the change in responsibility for activity from Government of Vietnam to U.S. forces from first to second draft, is a back-handed way of admitting the difference in policy, not just of words.

[40] Item 330 Memorandum for the Record of a Meeting, Executive Office Building, Washington, November 24, 1963, 3 p.m. Subject. South Vietnam Situation https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=661

[41] The concept of “unity” informs one of the paragraphs from the first draft of NSAM 273, which Prouty discussed at some length in a few of his essays. In Bundy’s draft, Paragraph Four reads: “It is of the highest importance that the United States Government avoid either the appearance or the reality of public recrimination from one part of it against another, and the President expects that all senior officers of the Government will take energetic steps to insure that they and their subordinates go out of their way to maintain and to defend the unity of the United States Government both here and in the field.” As published, reference to unity is clarified as “support for established U.S. policy in South Vietnam” – which produces a different reading than the potentially ominous warning written on the eve of the presidential assassination. It could be fairly argued, however, even lacking the precise term “South Vietnam”, that the paragraph in the first draft was referring to policies thereof, as there had been a lot of concern in the period between the Diem coup and the Honolulu Conference with perceived divisions, stoked in part by an article written by David Halberstram. These concerns are reflected in the documents published in Foreign Relations of the United States Aug-Dec 1963 from those weeks in November. That said, Prouty’s alert reading has a context, and it should not be overlooked that McGeorge Bundy was responsible for, among other things: a) called off the flight meant to destroy Castro’s last T33, ensuring failure of the Bay of Pigs b) wrote first draft of NSAM 273 c) believed to have contacted Air Force One from White House Situation Room Nov 22/63 to report lone gunman responsible for JFK assassination d) wrote first draft of NSAM 288.

[42] Item 331 National Security Action Memorandum No. 273 November 26, 1963 https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=663

[43] Prouty, Kennedy and the Vietnam Commitment, Collected Works

[44] Memorandum From the Secretary of Defense (McNamara) to the President, March 16, 1964. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v01/d84

[45] Prouty, Hidden Role of Conspiracy, 1993, Collected Works

[46] Leslie Gelb, Foreign Affairs; Kennedy and Vietnam, Section A Page 17, New York Times, January 6, 1992

[47] Prouty, Vietnam Daze With McNamara, Collected Works

[48] Item 181 Telegram from the Department of State to the Embassy in Vietnam October 5, 1963. https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=945#relPageId=397

[49] The Memorandum states: “After discussion of the remaining recommendations of the report” – that is, recommendations other than those involving the planned withdrawals – “the President approved an instruction to Ambassador Lodge which is set forth in State Department telegram No. 534 to Saigon.” This telegram’s featured “instruction” refers specifically to a series of proposed Actions to guide approaches to Diem, none of which refer to troop withdrawals. The attempt to tie the matters together is strained, but notably had also found expression by Lodge during the meeting with LBJ on November 24, 1963 (i.e. talk of withdrawal simply a negotiating ploy)

[50] Prouty, Vietnam Daze with McNamara, Collected Works

[51] In contrast, the presentation of NSAM No. 263 in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1963, vol. 4 Vietnam: August-December 1963, published in 1991, is properly cross-referenced.

[52] Prouty, Vietnam Daze with McNamara, Collected Works

[53] Chronology, Pentagon Papers Gravel Edition Vol II, Beacon Press pp 207-223

[54] Prouty, Vietnam Daze with McNamara, Collected Works

[55] Tom Wicker, Does JFK Conspire Against Reason?, New York Times, December 15, 1991

[56] Prouty, Stone’s JFK and the Conspiracy, 1996, Collected Works

Prouty believed, based on having seen numerous copies of the November 21 draft, that it was relatively widely distributed across the senior layers of the national security apparatus. A cover note attached to a copy distributed to Bundy’s brother William, a deputy within the Defense Department, asks him to review and also consult on the draft with McNamara.

Prouty believed, based on having seen numerous copies of the November 21 draft, that it was relatively widely distributed across the senior layers of the national security apparatus. A cover note attached to a copy distributed to Bundy’s brother William, a deputy within the Defense Department, asks him to review and also consult on the draft with McNamara. A second draft of the proposed NSAM 273 was composed on November 24. Changes in the draft were notable in paragraph 7, which originally discussed “the development of additional Government of Vietnam resources” to be used for “action against North Vietnam.” The revision appeared to address kinetic activity generated directly by U.S. forces, in accord with established covert protocols (i.e. the “plausibility of denial”).

A second draft of the proposed NSAM 273 was composed on November 24. Changes in the draft were notable in paragraph 7, which originally discussed “the development of additional Government of Vietnam resources” to be used for “action against North Vietnam.” The revision appeared to address kinetic activity generated directly by U.S. forces, in accord with established covert protocols (i.e. the “plausibility of denial”). On November 26, 1963, National Security Action Memorandum No. 273 was signed by McGeorge Bundy and updated NSAM 263 in United States official policy for South Vietnam.

On November 26, 1963, National Security Action Memorandum No. 273 was signed by McGeorge Bundy and updated NSAM 263 in United States official policy for South Vietnam. The one specific reference Gelb uses to respond to the supposed misrepresentations which had him so vexed, is itself distorted with some lawyerly spin: “Most officials also viewed the withdrawal memo as part of a White House ploy to scare President Diem of South Vietnam into making political reforms…That is precisely how the State Department instructed the U.S. Embassy in Saigon to understand NSAM 263.” What Gelb is referring to (and this became a talking point for other critics as well), is a State Department telegram to Lodge’s Vietnam embassy dated October 5, 1963.

The one specific reference Gelb uses to respond to the supposed misrepresentations which had him so vexed, is itself distorted with some lawyerly spin: “Most officials also viewed the withdrawal memo as part of a White House ploy to scare President Diem of South Vietnam into making political reforms…That is precisely how the State Department instructed the U.S. Embassy in Saigon to understand NSAM 263.” What Gelb is referring to (and this became a talking point for other critics as well), is a State Department telegram to Lodge’s Vietnam embassy dated October 5, 1963. Prouty’s issues with Gelb extended beyond the latter’s simplistic denial that Kennedy was just “going to abandon South Vietnam to a communist takeover.” Gelb’s previous role as director of the “Pentagon Papers” project could not be overlooked. Prouty:

Prouty’s issues with Gelb extended beyond the latter’s simplistic denial that Kennedy was just “going to abandon South Vietnam to a communist takeover.” Gelb’s previous role as director of the “Pentagon Papers” project could not be overlooked. Prouty: The Chronology in Vol. II of the Pentagon Papers begins May 8, 1963 and concludes on November 23, 1963.

The Chronology in Vol. II of the Pentagon Papers begins May 8, 1963 and concludes on November 23, 1963. Neither of these final two items actually occurred as described. Lodge did not meet with either President Kennedy or newly sworn-in President Johnson on November 22, the day on which President Kennedy was assassinated. NSAM 273 was not made official on November 23, and the specific meeting pertaining to the document was not held until the following day. Prouty:

Neither of these final two items actually occurred as described. Lodge did not meet with either President Kennedy or newly sworn-in President Johnson on November 22, the day on which President Kennedy was assassinated. NSAM 273 was not made official on November 23, and the specific meeting pertaining to the document was not held until the following day. Prouty: