Last year at the JFK Lancer Conference in Dallas, Bart Kamp was awarded the New Frontier award. The citation stated that his work in reexamining the second floor encounter of Oswald with Texas School Book Depository foreman Roy Truly and motorcycle officer Marrion Baker utilized “a broad array of new data, including documents and statements of the participants and a variety of TSBD witnesses.” We agreed with this award and the description of the achievement. The second floor lunch encounter is a thread-worn shibboleth of the Warren Report that – like Oswald’s mail order rifle – the first generation of critics simply passed on; the notable exception being Harold Weisberg in his book Whitewash II. In Reclaiming Parkland, I began to question it, largely based on Marrion Baker’s first day affidavit, where the officer does not even mention the episode – or Oswald or Truly. Even though, as he wrote the affidavit, Oswald was sitting across from him in the rather small witness room. In other words, after he had just stuck a gun in his stomach, Baker didn’t recognize him.

But Bart Kamp goes much further than that in his analysis. We are presenting a small part of that long essay here, with a link to the longer version at the admirable group Dealey Plaza UK. The new revised version of the essay, from which this part is adapted, will be posted there soon and we will link to it then. This is the kind of work, daring and original, questioning accepted paradigms with new and provocative evidence, that KennedysandKing.com stands for.

~ Jim DiEugenio

The current, updated version of the full essay can be read here.

If the 2nd-floor lunchroom encounter did not happen,

then was Oswald encountered somewhere else?

Some researchers think Oswald walked up the stairs inside the first floor vestibule, went through the corridor on the second floor, passed the door, moving from right to left, and got his coke. This is possible, but the news reports and statements, which come in various guises, show Oswald was encountered on the first floor instead, while trying to leave the building. It is even possible that Baker never saw Oswald until he was brought in while Baker was giving the affidavit taken by Marvin Johnson.

Bob Considine of the Hearst Press, for example, was told that Oswald had been questioned inside the building “almost before the smoke from the assassin’s gun had disappeared.” That hardly sounds like an encounter on the second floor does it? It points more to an altercation on the first floor, just where Oswald had claimed to be. Various newspapers made reference to this so-called first floor encounter instead of the second floor lunch room encounter.

Roy Truly was overheard by Kent Biffle, who reported in the November 23 edition of the Dallas Morning News:

“In a storage room on the first floor, the officer, gun drawn, spotted Oswald. ‘Does this man work here?’, the officer reportedly asked Truly. Truly, who said he had interviewed and had hired Oswald a couple of months earlier reportedly told the policeman that Oswald was a worker.”

Biffle mentions overhearing Truly again in the Dallas Morning News, edition from November 21, 2000:

“Hours dragged by. The building superintendent showed up with some papers in his hand. I listened as he told detectives about Lee Oswald failing to show up at a roll call. My impression is there was an earlier roll call but it was inconclusive inasmuch as several employees were missing. This time, however, all were accounted for but Oswald. I jotted down all the Oswald information. The description and address came from company records already examined by the superintendent. The superintendent would recall later that he and a policeman met Oswald as they charged into the building after the shots were fired.”

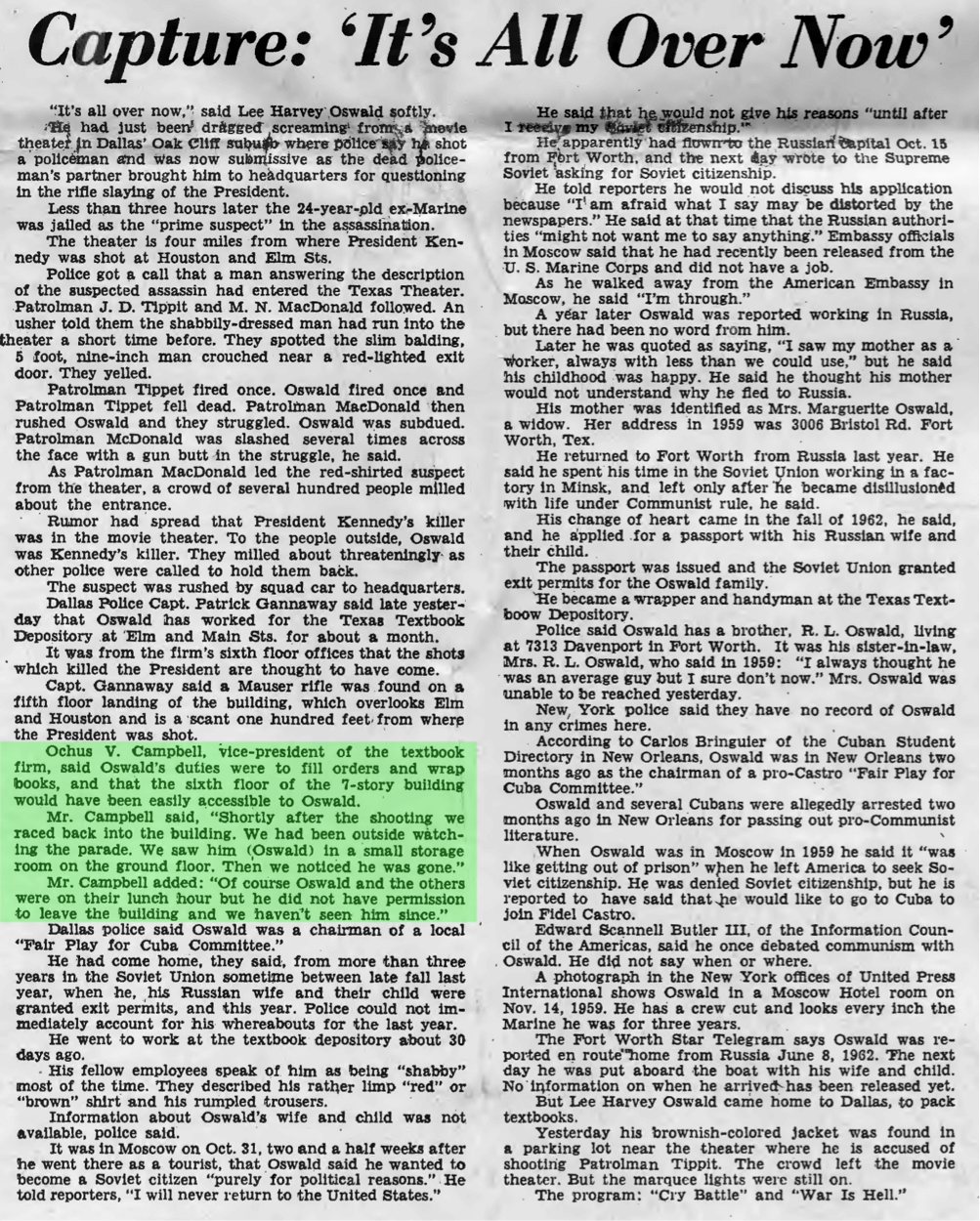

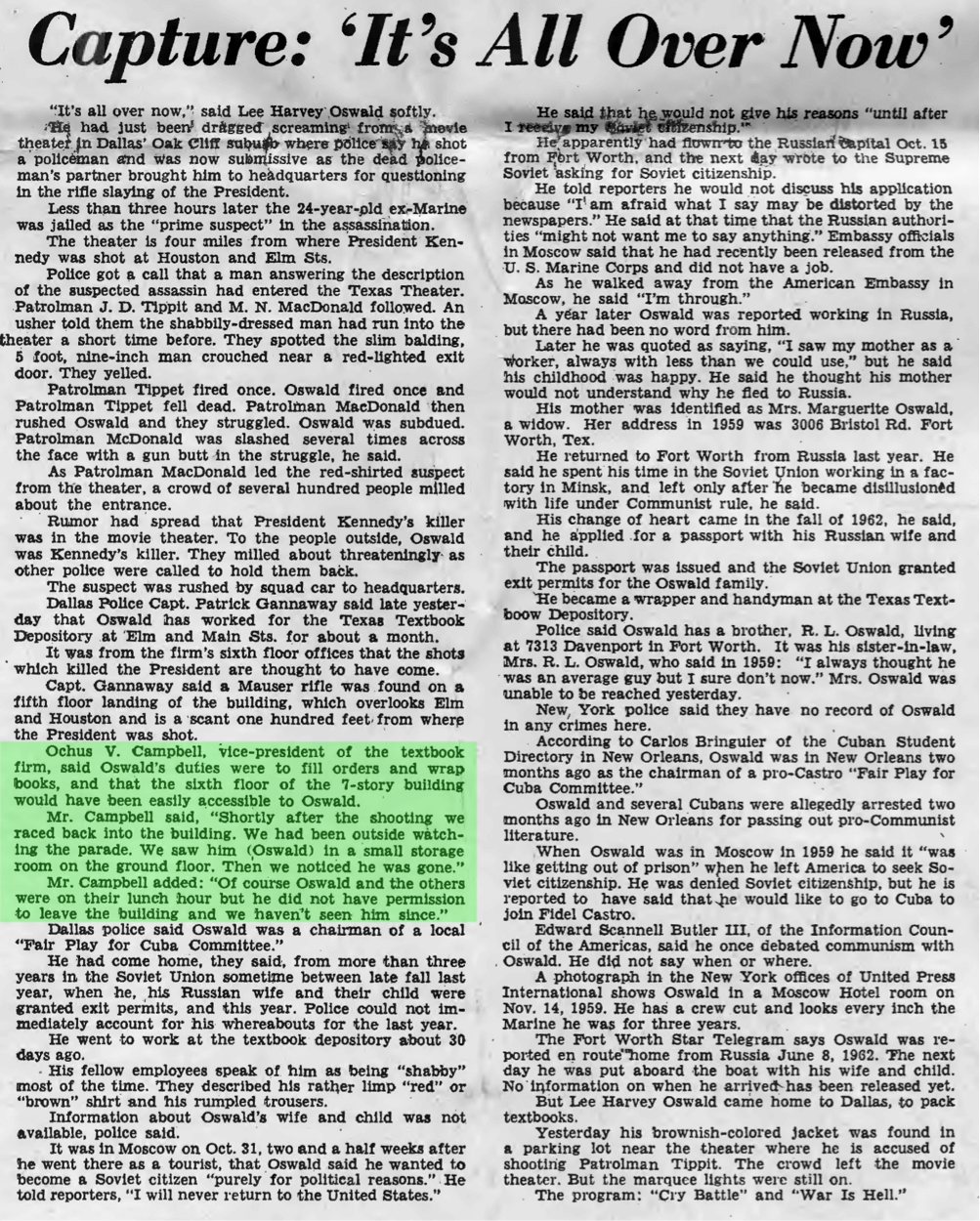

Ochus Campbell, the vice president of the TSBD, stated in the New York Herald Tribune on November 22:

“Shortly after the shooting we raced back into the building. We had been outside watching the parade. We saw him (Oswald) in a small storage room on the ground floor. Then we noticed he was gone.” Mr. Campbell added: “Of course he and the others were on their lunch hour but he did not have permission to leave the building and we haven’t seen him since.”

Detective Ed Hicks is quoted in the London Free Press on November 23, and in various other newspapers, saying:

As the Presidential limousine sped to the hospital the police dragnet went into action. Hicks said at just about that time, Oswald came out of the front door of the red bricked warehouse. A policeman asked him where he was going. He said he wanted to see what all the excitement was all about.

In addition, from Jack White’s archive at Baylor in a document called “Escape”, city detective Ed Hicks, after intensive investigation of the slaying, drew this picture of the hour surrounding the tragedy:

“As Oswald left the building, he was stopped by Dallas police, Oswald told them he worked in the building and was going down to see what was going on.” [AP, 1:45 a.m. CST]

In the Washington Post of November 23, Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry is quoted:

“As an officer rushed into the building Oswald rushed out. The policeman permitted him to pass after the building manager told the policeman that Oswald was an employee.”

The first officer to reach the six-story building, Lieutenant Curry said, found Oswald among other persons in a lunchroom. New York Times, Nov 24thDallas, [11/23], Donald Jansen (from Jack White’s archive at Baylor in a document called “Escape”)

The Sydney Morning Herald of November 24 reports:

Police said that a man who was identified as Oswald walked through the door of the warehouse and was stopped by a policeman. Oswald told the policeman “I work here” and when another employee confirmed that he did, the policeman let Oswald walk away, they said.

Henry Wade, during a press conference, which by the looks of it was published unedited in the New York Times on November 26, states:

“A police officer, immediately after the assassination, ran in the building and saw this man in a corner and tried to arrest him; but the manager of the building said he was an employee and it was all right. Every other employee was located but this defendant of the company. A description and name of him went out to police to look for him.”

J. Edgar Hoover, in a telephone conversation with LBJ, states:

“at the entrance of the building he was stopped by police officers, well he is alright, he works here, you needn’t hold him. They let him go.”

In Gary Savage’s book, First Day Evidence, Baker states:

“Shortly after I entered the building I confronted Oswald. The man who said he was the building superintendent said that Oswald was all right, that he was an employee there. We left Oswald there, and the supervisor showed me the way upstairs.”

{youtube}9tjgH8o4Adw{/youtube}

Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry’s press conference of November 23, 1963

Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry gave a press conference on November 23, 1963, during which he stated a few things that are very interesting:

At 5:25:

Reporter: Could you detail for us what lead you to Oswald?

Chief Curry: Not exactly except uh in the building we uh, when we uh went to the building, why, he was observed in the building at the time but the manager told us that he worked there and the officers passed him on up then because the manager said he was an employee…”

At 6:41:

Reporter: Did you say chief that a policeman had seen him in the building?

Chief Curry: Yes

Reporter: After the shot was fired?

Chief Curry: Yes

Reporter: uh why didn’t he uh arrest him then?

Chief Curry: Because the manager of the place told us that he was an employee, ‘said he’s alright he’s an employee.”

Reporter: Did he look suspicious to the policeman at this point?

Chief Curry: I imagine the policeman was checking everyone he saw as he went into the building.

At 10:42:

Reporter: And you have the witness who places him there after the time of the shooting.

Chief Curry: My police officer can place him there after the shooting.

Reporter: Your officer wanted to stop him and then was told by the manager that he worked there.

Chief Curry: Yes.

So let’s get this straight: Truly and Campbell, TSBD employees, are recorded by the newspapers while at the TSBD. Various ranking officers of the Dallas police are quoted in the corridors of the DPD. And even Hoover and LBJ discuss it!

Oswald’s alibi given just before and just after the shooting

In the second part of this study I will focus exclusively on the interrogation of Lee Oswald; here I will review the parts relating to the second floor lunch room encounter. These are the notes and reports by Robbery and Homicide Captain Will Fritz, FBI agents James Hosty and James Bookhout, Postal Inspector Harry Dean Holmes (who was an informant for the FBI), and Thomas Kelley of the Secret Service. These people were all present during the interrogations either Friday, Saturday and/or Sunday morning.

Captain Will Fritz interrogated Lee Oswald for roughly a dozen hours. Fritz claimed he took no notes, but in fact there were some (probably kept as a souvenir…); these were submitted anonymously in the mid-90’s to the ARRB after Fritz had died. These notes had been ‘buried’ for more than 33 years; until they appeared, researchers had to make do with Fritz’s statement from November 22 and his Warren Commission testimony.

Captain Will Fritz interrogated Lee Oswald for roughly a dozen hours. Fritz claimed he took no notes, but in fact there were some (probably kept as a souvenir…); these were submitted anonymously in the mid-90’s to the ARRB after Fritz had died. These notes had been ‘buried’ for more than 33 years; until they appeared, researchers had to make do with Fritz’s statement from November 22 and his Warren Commission testimony.

Fritz’s interrogation notes contain a few gems when it comes to Lee’s location just before, during and just after the assassination:

On page 1 is found:

claims 2nd floor Coke when

off came in

Oswald had a coke from the 2nd floor when the officer came in. Came in where? 1st? 2nd?

to first floor had lunch

Oswald had lunch on the 1st floor.

out with Bill Shelley

in front

Oswald knew Shelley was standing in front of the building. And that is before the shooting, not after! As Shelley had departed almost immediately after the shooting from the TSBD steps.

|

| Page 1 of Captain Fritz’s Notes |

On page 3 of the same set of Fritz’s interrogation notes:

says two negro came in

one Jr + short negro – ask? for lunch says cheese

sandwiches + apple

Oswald saw Jarman and possibly Norman come into the Domino Room while he was having his lunch.

Lunch consisted of a cheese sandwich and an apple.

|

| Page 3 of Captain Fritz’s Notes |

Looking at both these pages, one thing becomes evident: a new sentence does not always start on a new line, but midway as well. This leaves his notes open to interpretation.

In his report to Chief Curry from November 23, 1963, Fritz says:

“We also found that this man had been stopped by Officer M.L. Baker while coming down the stairs. Mr. Baker says that he stopped this man on the third or the fourth floor on the stairway, but as Mr. Truly identified him as one of the employees he was released.”

The undated draft of Fritz’s report states:

“I asked him what part of the building he was in when the president was shot, and he said that he was having his lunch about that time on the first floor. Mr. Truly had told me that one of the police officers had stopped this man immediately after the shooting near the back stairway, so I asked Oswald where he was when the police officer stopped him. He said he was on the second floor drinking a coca cola when the officer came in.”

Fritz’s Warren Commission testimony:

Mr. BALL. Did you ask him what happened that day; where he had been?

Mr. FRITZ. Yes, sir.

Mr. BALL. What did he say?

Mr. FRITZ. Well he told me that he was eating lunch with some of the employees when this happened, and that he saw all the excitement and he didn’t think, I also asked him why he left the building. He said there was so much excitement there then that “I didn’t think there would be any work done that afternoon and we don’t punch a clock and they don’t keep very close time on our work and I just left.”

Mr. BALL. At that time didn’t you know that one of your officers, Baker, had seen Oswald on the second floor?

Mr. FRITZ. They told me about that down at the bookstore; I believe Mr. Truly or someone told me about it, told me they had met him, I think he told me, person who told me about, I believe told me that they met him on the stairway, but our investigation shows that he actually saw him in a lunch room, a little lunch room where they were eating, and he held his gun on this man and Mr. Truly told him that he worked there, and the officer let him go.

Mr. BALL. Did you question Oswald about that?

Mr. FRITZ. Yes, sir; I asked him about that and he knew that the officer stopped him all right.

Mr. BALL. Did you ask him what he was doing in the lunch room?

Mr. FRITZ. He said he was having his lunch. He had a cheese sandwich and a Coca-Cola.

Mr. BALL. Did he tell you he was up there to get a Coca-Cola?

Mr. FRITZ. He said he had a Coca-Cola.

Although he learned from a conversation with Roy Truly at the “bookstore” [sic] that they met Oswald on the stairway, his own investigation shows it was inside the second floor lunch room instead! It has also only recently come to light that Martha Joe Stroud corresponded with the Warren Commission, relating that Fritz was not happy with his statement and that he wanted it changed. So there seem to be two versions of his statement. I would love to see the difference between the two! (This was recently posted by Robin Unger.)

James Hosty and James Bookhout of the FBI state in their joint November 23 report:

“OSWALD stated that he went to lunch at approximately noon and he claimed he ate his lunch on the first floor in the lunchroom; however he went to the second floor where the Coca-Cola machine was located and obtained a bottle of Coca-Cola ‘for his lunch. OSWALD claimed to’ be on the first floor when President JOHN F. KENNEDY passed by his building.”

This report does not mention the specific location of Oswald on the first floor at the time of the assassination, nor does it mention any encounter involving Oswald, a police officer and Truly.

In the solo report by James Bookhout (dated November 24, after Oswald was dead), things are turned around a bit, but not for the better.

“Oswald stated that on November 22 1963, at the time of the search of the Texas School Book Depository building by Dallas police officers, he was on the second floor of said building, having just purchased a Coca-Cola from the soft-drink machine, at which time a police officer came into the room with pistol drawn and asked him if he worked there.

Mr. Truly was present and verified that he was an employee and the police officer thereafter left the room and continued through the building. Oswald stated that he took this Coke down to the first floor and stood around and had lunch in the employee’s lunch room. He thereafter went outside and stood around for five or ten minutes with foreman Bill Shelley.”

First, he mentions “officers”, when Baker was the only police officer in that building for a fair amount of time (5 to 10 minutes is a reasonable assumption); everyone else on the force was busy in the railroad yard. Or is this an indication that Oswald was in the building much later than he has been credited for?

Second, Oswald had purchased a coke, which from a timing perspective makes it already “interesting” (getting the correct change out, putting it in the machine and waiting for the bottle to appear and to take the cap off). But what is more important is that neither Truly nor Baker saw anything in his hands.

Third, Oswald stood around and had lunch after the shooting, and even stood outside with Bill Shelley for 5 to 10 minutes after having had his lunch. So how long was he in that building? According to this second report, for quite some time, which makes one wonder how the bus-to-cab ride transpired, how he changed his clothes, ‘grabbed his gun’ and walked towards 10th and Patton to blow Tippit away. This is impossible from the timing perspective described by James Bookhout! Plus Shelley left immediately after the shooting and did not come back until at least 5 minutes after leaving.

Hosty writes in Assignment Oswald about an exchange he had with Oswald during his questioning while in police custody. No second floor lunch room encounter whatsoever.

Okay now, Lee, you work at the Texas School Book Depository, isn’t that right?

Yeah, that’s right.

When did you start working there?

About October fifteenth.

What did you do down there?

I was just a common laborer.

Now, did you have access to all floors of the building?

Of course.

Tell me what was on each of those floors.

The first and second floors have offices. The third and fourth floor are storage. So are the fifth and sixth.

And you were working there today, is that right?

Yep.

Were you there when the president’s motorcade went by?

Yeah.

Where were you when the president went by the book depository?

I was eating my lunch in the first floor lunchroom.

What time was that?

About noon.

Were you ever on the second floor around the time the president was shot?

Well, yeah. I went up there to get a bottle of Coca-Cola from the machine for my lunch.

But where were you when the president actually passed your building?

On the first floor in the lunchroom.

And you left the depository, isn’t that right?

Yeah.

When did you leave?

Well, I figured with all the confusion there wouldn’t be any more work to do that day.

Hosty tried to pin Oswald’s location down decades after the fact, based on memory and also probably the interrogation report signed by him and James Bookhout, since it coincides neatly with the so-called recollection above. Oswald has gone for lunch and stayed in the Domino Room after he had gotten his coke from the second floor. Many must have seen him, since the ladies from the office all started to have their lunch at 12:00 upstairs in the second floor lunchroom. Some people will claim that this pins Oswald on the first floor, and that he went upstairs via the front of the building and ended up passing the window in the door leading to the small area in front of the lunchroom, thus being spotted by Baker. But why would he do that? The Domino Room was in the back at the east end, where the infamous back stairs were perhaps a little closer, affording more direct access.

The Secret Service was present too. Forrest Sorrels and Thomas J. Kelley were there during some of Lee Oswald’s interrogations.

Thomas J. Kelley is the only one who supplies an interrogation report that actually goes so far as to claim that Oswald explicitly admitted to not having watched the motorcade. In his First interview with LHO, he states:

“I asked him if he viewed the parade and he said he had not. I then asked him if he had shot the President and he said he had not. I asked him if he has shot governor Connally and he said he had not.”

None of the notes or reports – by Fritz, Bookhout, Hosty or even Harry Dean Holmes, who was actually present during that final interrogation of Oswald alongside Kelley – back up the statement highlighted above.

According to Vince Palamara, Kelley perjured himself during the HSCA hearings.

Finally, Postal Inspector and FBI informant Harry Dean Holmes, on page 4 of his report dated December 17, 1963:

“the commotion surrounding the assassination took place and when he went downstairs, a policeman questioned him as to his identification and his boss stated ‘he is one of our employees’, whereupon the policeman had him step aside momentarily”.

In his statement and his testimony (see below), Oswald is being asked to step aside.

Holmes’ Warren Commission testimony:

Mr. BELIN. By the way, where did this policeman stop him when he was coming down the stairs at the Book Depository on the day of the shooting?

Mr. HOLMES. He said it was in the vestibule.

Mr. BELIN. He said he was in the vestibule?

Mr. HOLMES. Or approaching the door to the vestibule. He was just coming, apparently, and I have never been in there myself. Apparently there is two sets of doors, and he had come out to this front part.

Mr. BELIN. Did he state it was on what floor?

Mr. HOLMES. First floor. The front entrance to the first floor.

And later on during the very same testimony:

Mr. BELIN. Now, Mr. Holmes, I wonder if you could try and think if there is anything else that you remember Oswald saying about where he was during the period prior or shortly prior to, and then at the time of the assassination?

Mr. HOLMES. Nothing more than I have already said. If you want me to repeat that?

Mr. BELIN. Go ahead and repeat it.

Mr. HOLMES. See if I say it the same way?

Mr. BELIN. Yes.

Mr. HOLMES. He said when lunchtime came he was working in one of the upper floors with a Negro. The Negro said, “Come on and let’s eat lunch together.” Apparently both of them having a sack lunch. And he said, “You go ahead, send the elevator back up to me and I will come down just as soon as I am finished.” And he didn’t say what he was doing. There was a commotion outside, which he later rushed downstairs to go out to see what was going on. He didn’t say whether he took the stairs down. He didn’t say whether he took the elevator down.

But he went downstairs, and as he went out the front, it seems as though he did have a coke with him, or he stopped at the coke machine, or somebody else was trying to get a coke, but there was a coke involved. He mentioned something about a coke. But a police officer asked him who he was, and just as he started to identify himself, his superintendent came up and said, “He is one of our men.” And the policeman said, “Well, you step aside for a little bit. Then I just went on out in the crowd to see what it was all about.”

Step aside, which does not point to a second floor encounter, as Baker and Truly did a 180-degree turn after this alleged “lunch date”.

Lee Oswald did not lie when he claimed he was on the first floor when the president passed by the TSBD. Not only did Holmes relay this; so did Fritz in his interrogation notes, as did Bookhout and Hosty in their joint report.

James ‘Junior’ Jarman told the HSCA that Billy Lovelady told him that he had personally witnessed Oswald being allowed out of the front entrance by a policeman shortly after the assassination, and that Truly had said he was alright. (See HERE and HERE.)

This is, of course, hearsay – just as Pauline Sanders’ support for Mrs. Reid’s encounter with Oswald in his t-shirt is equally hearsay. But it is worth mentioning. What also needs to be taken into consideration is that Lovelady left for the railroad yard almost straight after the shooting had stopped, and said he went back in through the side entrance and ended taking police officers up in the elevator. Yet Lovelady is filmed standing outside on the TSBD steps afterwards by John Martin and Robert Hughes at about 12:50. And it looks like he is waiting to get in. Danny Garcia is there, as is Bonnie Ray Williams. Did Lovelady see Oswald leave then? Which would mean he left much later than has been acknowledged. Lovelady was extremely economical with the truth during his Warren Commission testimony as I already pointed out earlier.

{youtube}_vIbHH8CYMk{/youtube}

James Earl Jarman and Harold Norman saw Howard Brennan talking to a police officer. This by itself shows how quickly they made their way down from the fifth floor.

According to Harold Norman’s HSCA testimony, he states that after starting their descent from the fifth floor, they stopped on the fourth floor for a couple of minutes, because they saw the ladies looking through the windows at the railroad yard activity shortly after the shooting.

This is during the same interval in which Dorothy Garner stayed behind, after “following” Victoria Adams and Sandra Styles, when they started their descent; Garner was then joined by other women from those fourth floor offices. Norman’s HSCA testimony strengthens Dorothy Garner’s statements and also shows that the three African American men, Williams, Jarman and Norman, did not encounter anyone, not even Truly and Baker while they made their descent. Or did they wait much longer? Baker states in his HSCA testimony that he was spotted by them while they hid behind boxes on the 5th floor. Norman had no recollection of this during his testimony, and couldn’t attest to when he saw Truly after coming down to the first floor.

{youtube}Jk0toNwH7rc{/youtube}

Captain Will Fritz interrogated Lee Oswald for roughly a dozen hours. Fritz claimed he took no notes, but in fact there were some (probably kept as a souvenir…); these were submitted anonymously in the mid-90’s to the ARRB after Fritz had died. These notes had been ‘buried’ for more than 33 years; until they appeared, researchers had to make do with Fritz’s statement from November 22 and his Warren Commission testimony.

Captain Will Fritz interrogated Lee Oswald for roughly a dozen hours. Fritz claimed he took no notes, but in fact there were some (probably kept as a souvenir…); these were submitted anonymously in the mid-90’s to the ARRB after Fritz had died. These notes had been ‘buried’ for more than 33 years; until they appeared, researchers had to make do with Fritz’s statement from November 22 and his Warren Commission testimony.