Part 4: Assaulting the Ghetto: LBJ vs. the Kennedys

As I have tried to show in this series, the gestalt message contained in the books under discussion—that President Kennedy had no vision of what he wanted to do in regards to civil rights—is not supported by the record. (For an expression of that idea, see Bryant, pp. 471-73) John F. Kennedy did have a vision. It was articulated as far back as 1956, when he stated in a New York City speech that Harry Truman must be given credit for trying to pass a civil rights bill and added that Democrats must not waver on the issue. (NY Times, 2/8/56) It was reiterated when he voted for Title III of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. He advocated for that part of the bill because it would have given the attorney general expansive powers to file lawsuits on both voting rights and school integration issues. (Golden, pp. 94-95) In 1960, he told his civil rights advisory team that they could use information garnered by the Civil Rights Commission to break the back of voter discrimination in the South. (Golden, p. 139)

That goal was also contained in Harris Wofford’s memo, which was delivered to JFK in late December of 1960. (Nick Bryant writes that this was a thousand word memo; Wofford says it was 30 pages long, a rather significant difference. Since Wofford wrote it, I think we can trust him. See Bryant, p. 225; Wofford, p. 130) That memo advised he do as much as possible with executive orders and the judiciary, with the idea that this pressure would eventually cause something to break in the legislature. As we have seen, that is what President Kennedy did. When he placed an omnibus civil rights bill before Congress in February of 1963, he stated he felt he had gone as far as he could with executive orders; it was now time for the legislature to do its part. (Risen, p. 36) Contrary to what Bryant implies, the president then conducted one of the longest and most comprehensive lobbying actions ever in order to get the bill passed. (Bryant, p. 410; Risen, pp. 62-63) Based upon the actions of Bull Connor in Birmingham, and the president’s conversation with Dick Gregory, the February 1963 bill was revised and fortified. Again, contrary to what Bryant writes, the president did not lose interest in the bill that fall. (Bryant, pp. 450-52) He directly intervened in the legislative process in October. (Thurston Clarke, JFK’s Last Hundred Days, p. 249) He also told Philip Randolph, “I know this whole thing could cost me the election but I have no intention of turning back, now or ever.” (Golden, p. 98)

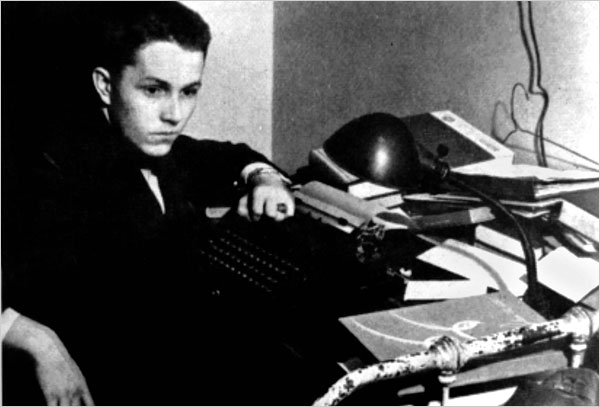

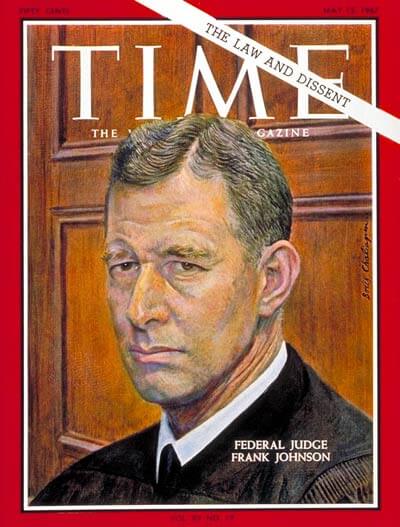

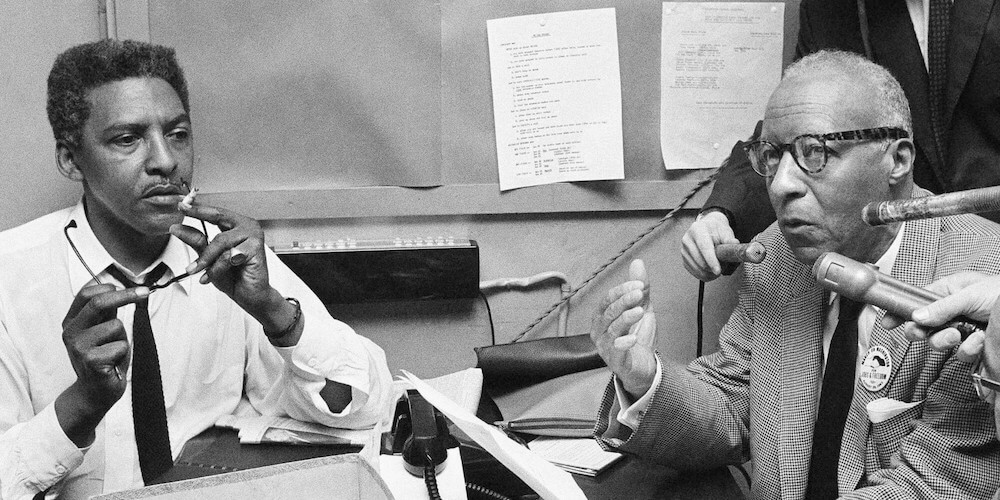

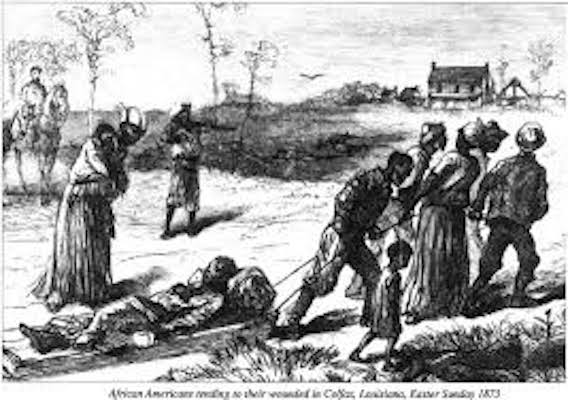

|

| Michael Harrington |

At this point in the discussion, we should pay particular attention to the last part of that statement, as it is one more indication that Kennedy did have a vision. And he and his brother were ahead of almost everyone—as we shall see, most certainly James Baldwin and Jerome Smith. For as his bill was moving through Congress, he was already thinking beyond its parameters. In June of 1963, Kennedy told a group of labor leaders that something would have to be done for the Negro. He continued by saying that we all owed them a debt of gratitude for being “in the streets” and calling our attention to the American Dream. (Golden, p. 131) What did JFK mean by this?

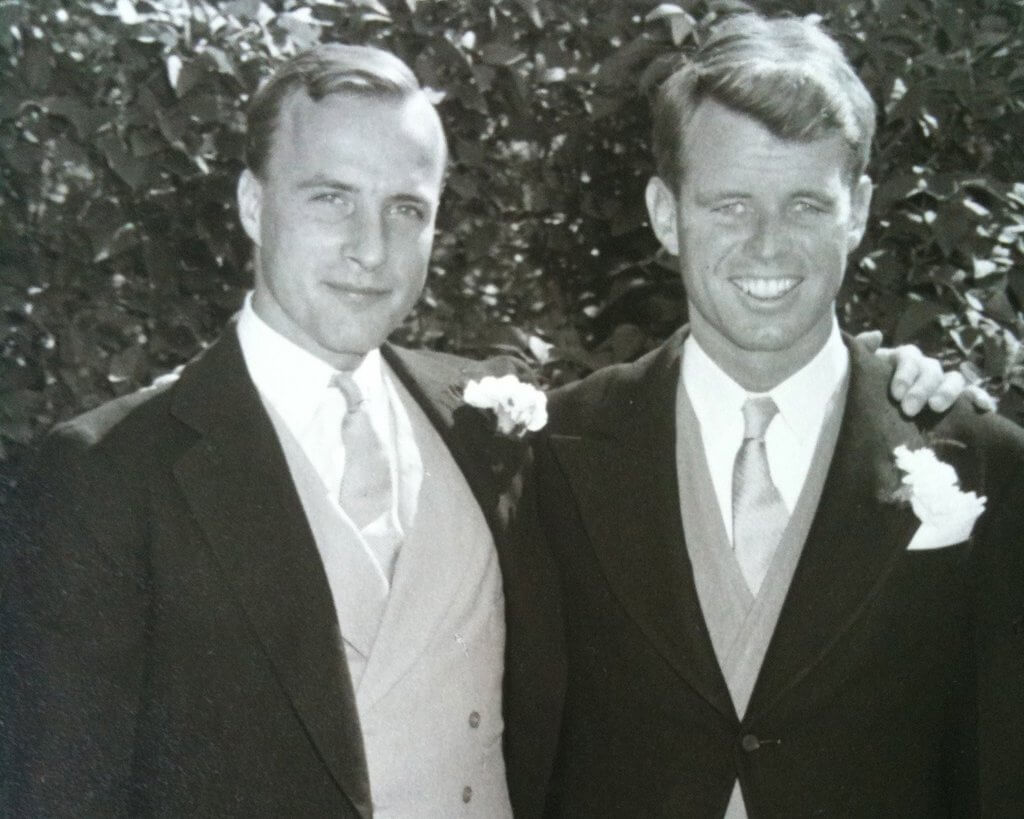

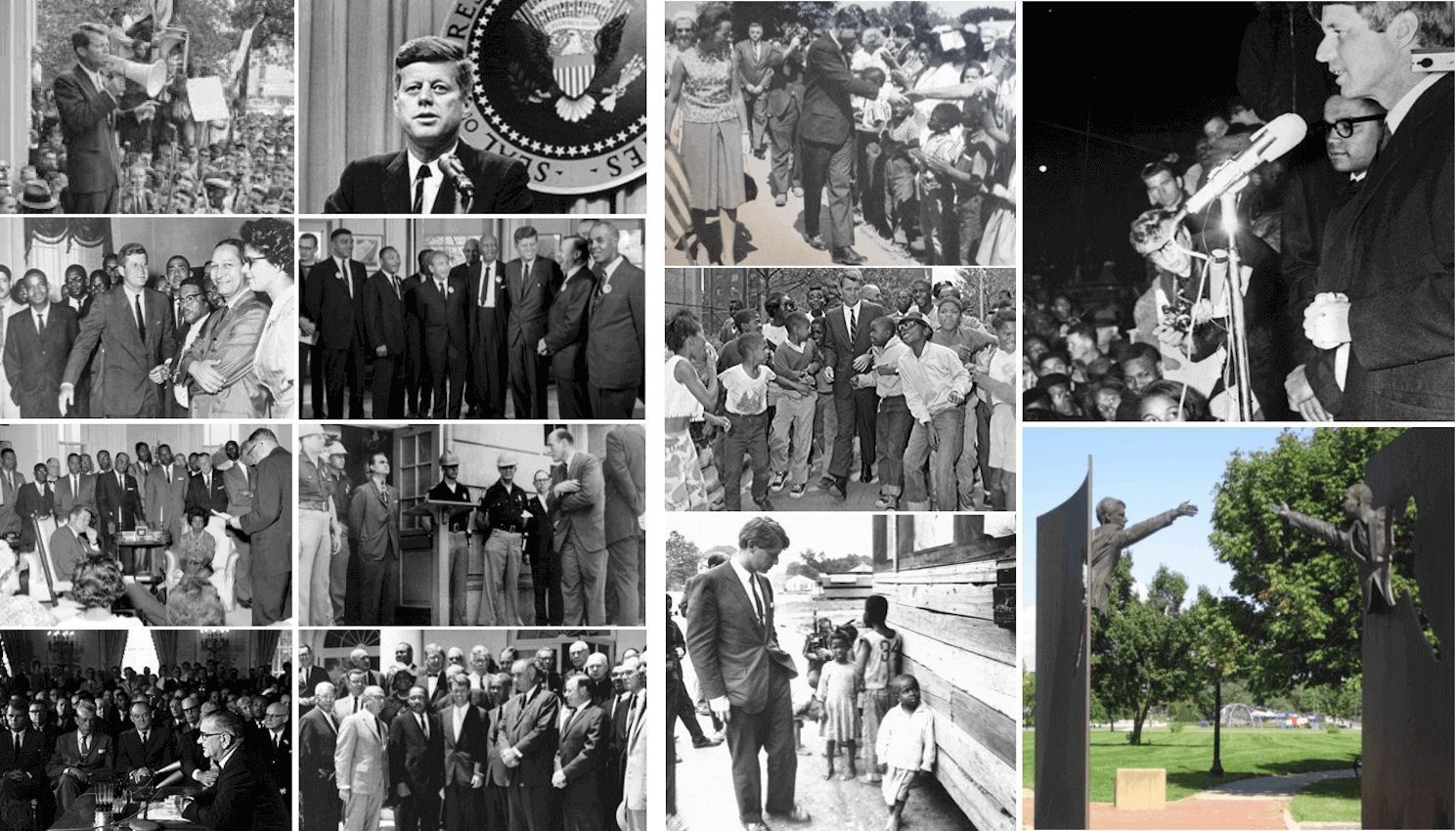

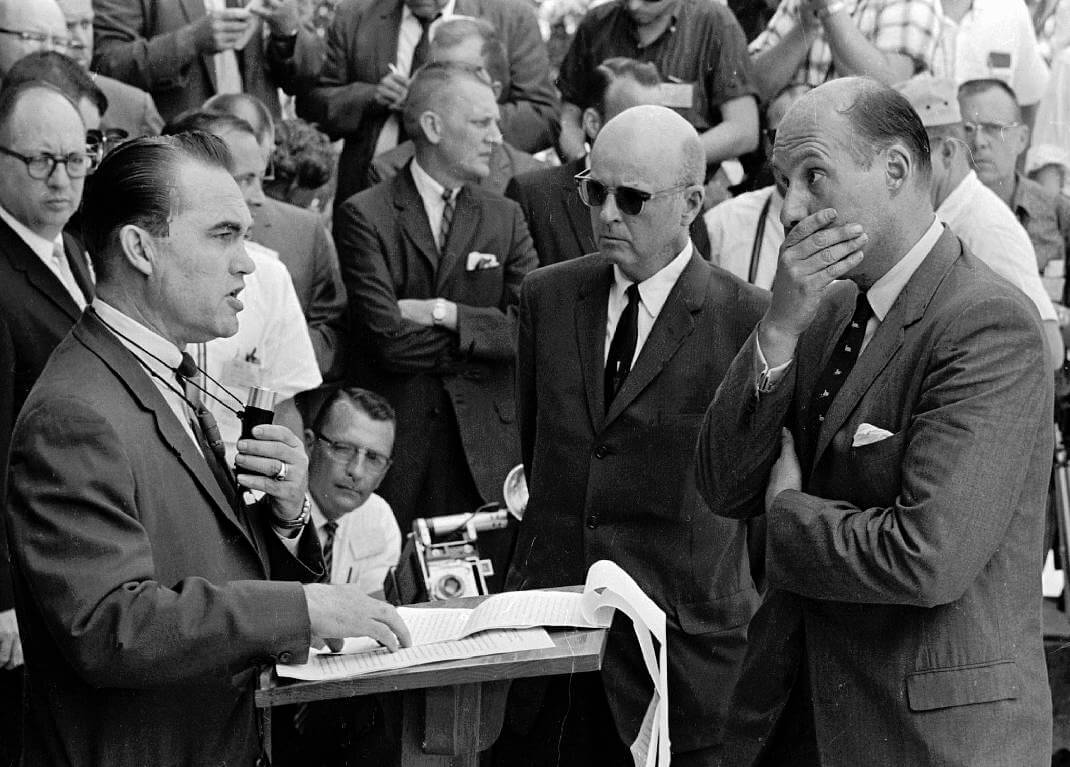

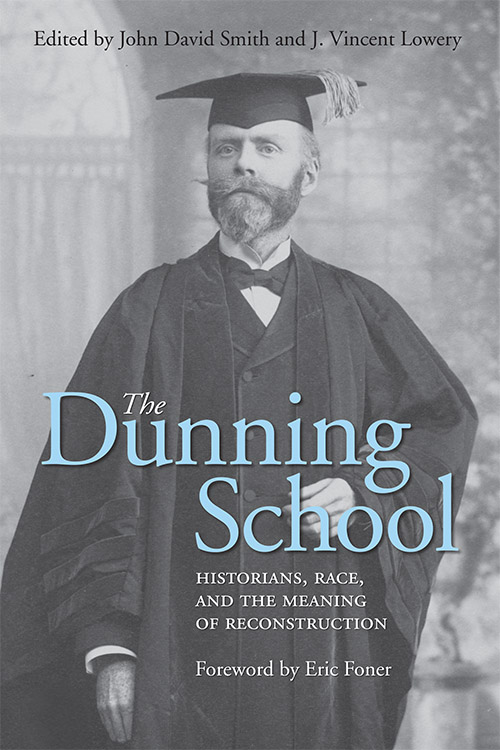

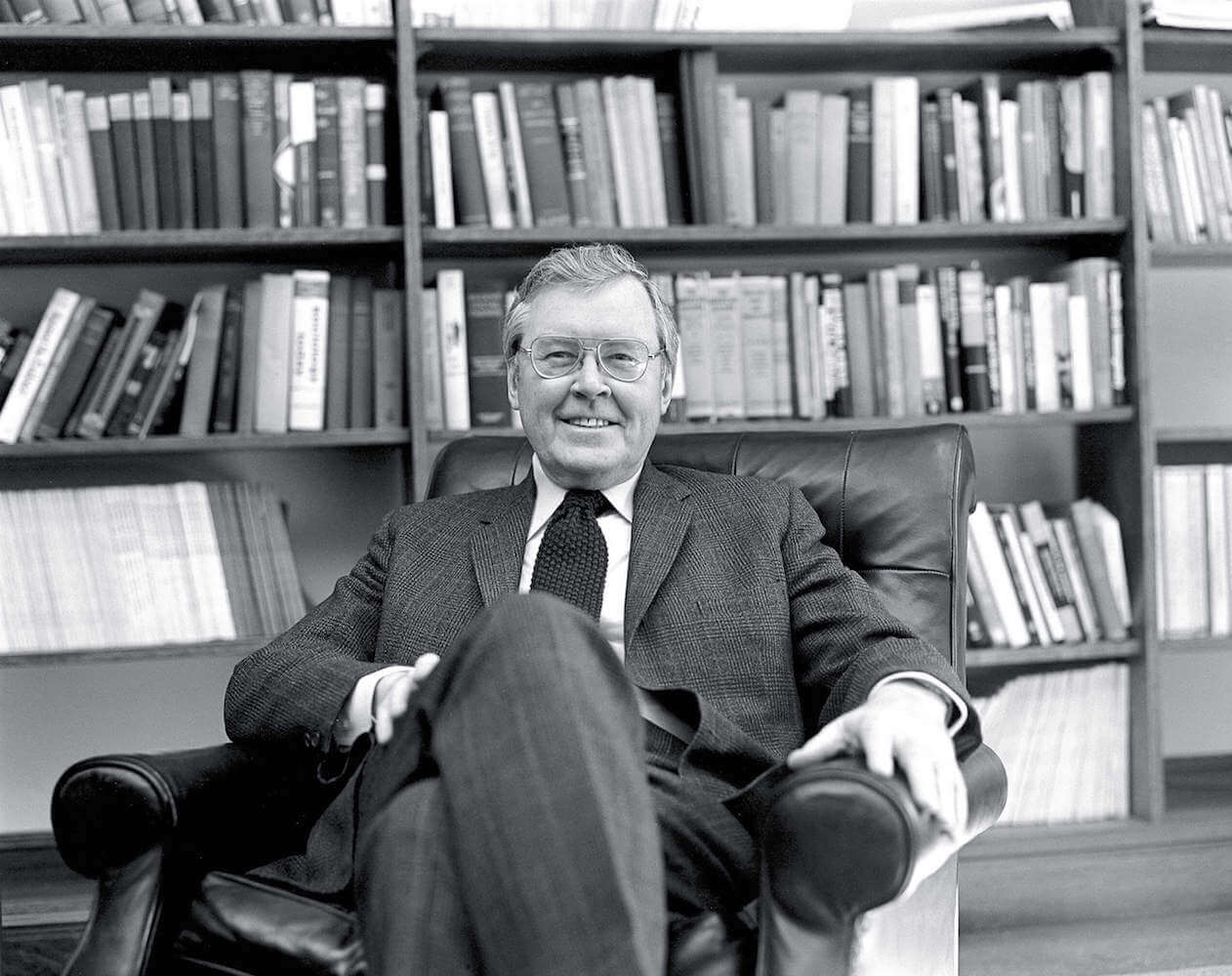

|

| Walter Heller & JFK |

As several authors have written, earlier in the year, the president had read Dwight MacDonald’s 13,000-word review of Michael Harrington’s book about the poor, The Other America. It left an indelible impression on him. In October of 1963, Homer Bigart had written a long article in The New York Times about pockets of poverty in Kentucky. The impact of those two articles caused a series of discussions between the president and his chief economic advisor, Walter Heller. (Clarke, pp. 242-43) Heller had written him a memo well before the Bigart article appeared. In it he stated that although the economy was expanding overall, there were pockets of poverty that were resistant to growth. Over months of discussion, the staunch Keynesian economist had to admit that in those pockets, people were “caught in a web of illiteracy, lack of skills, poor health and squalor.” After giving the president some statistics on the matter, Heller suggested what he called an “attack on poverty”. Kennedy told Heller that he was going to make this an election issue and he would visit some blighted areas in order to enter it onto the national stage.

In other words, the “War on Poverty”, or as some call it, the “Second Reconstruction”, was not President Johnson’s idea. But beyond that, there is something else lurking here as a back-story. Something that Thurston Clarke did not touch upon. And, in fact, few authors have ever discussed it. This back-story concerns the figure of David Hackett.

II

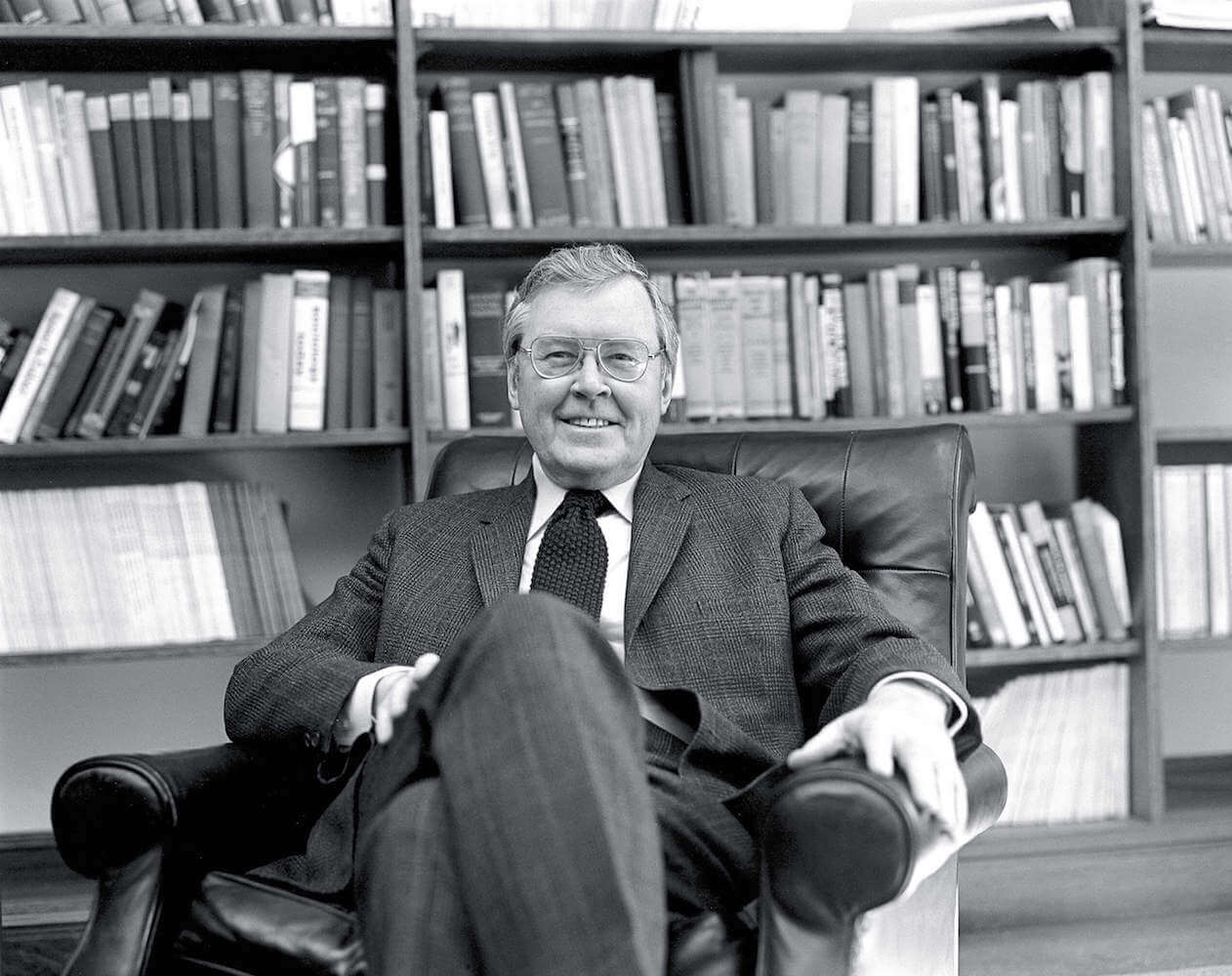

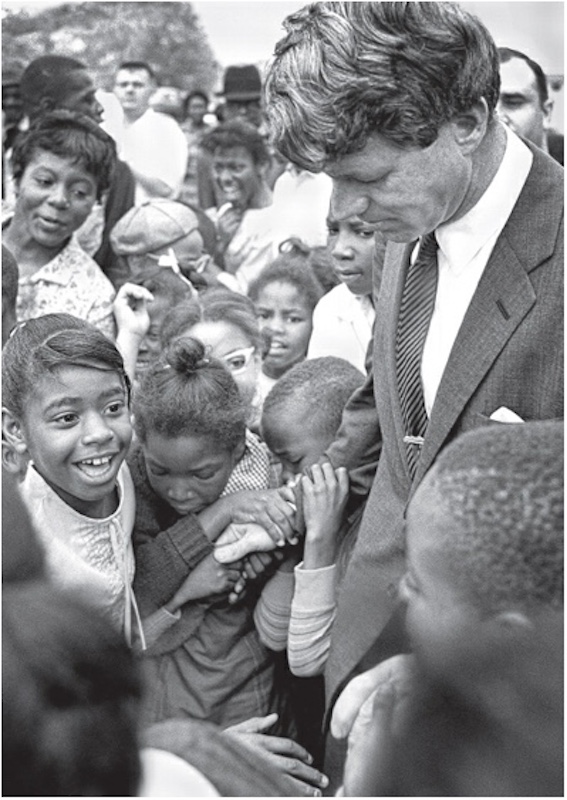

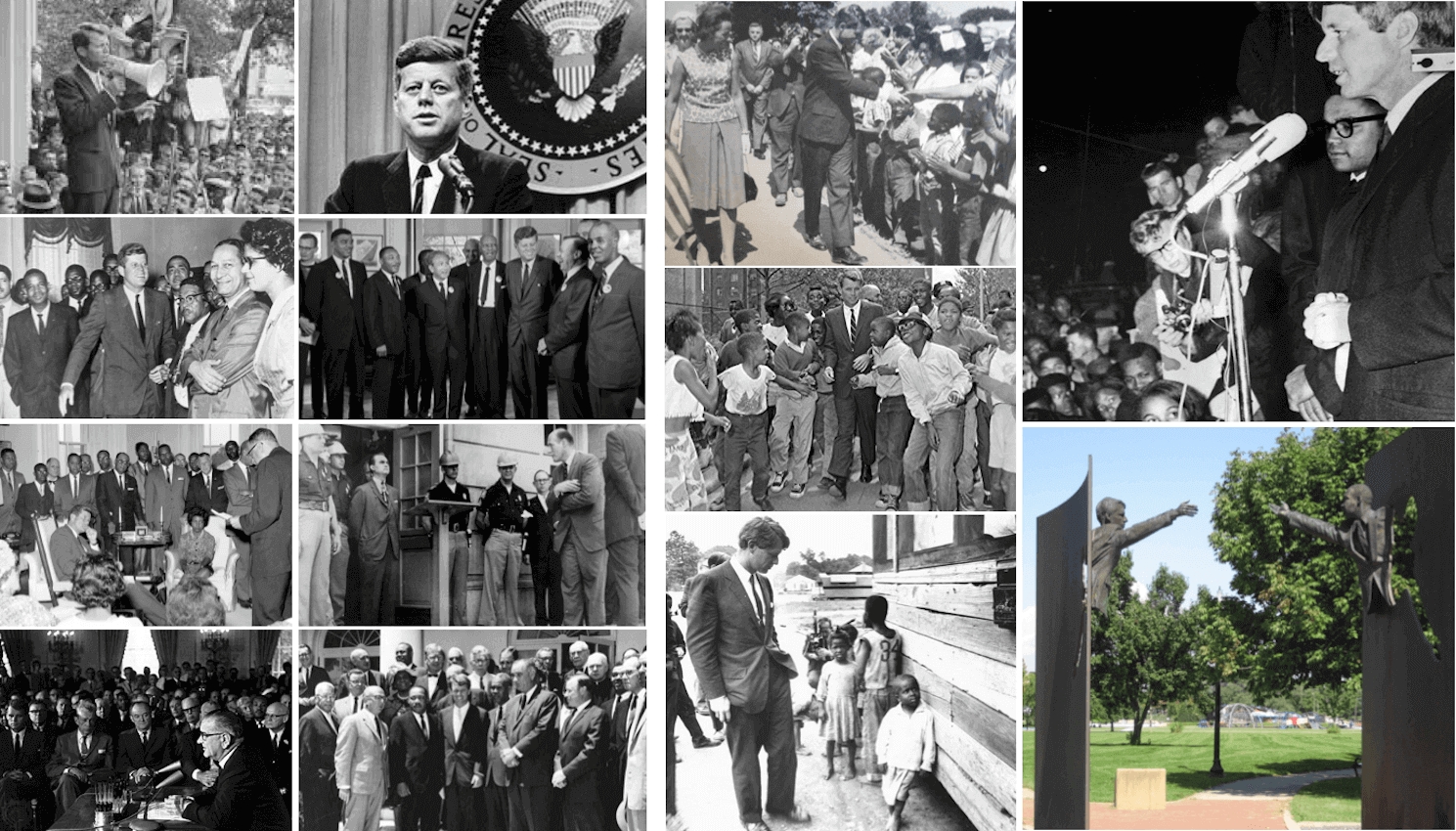

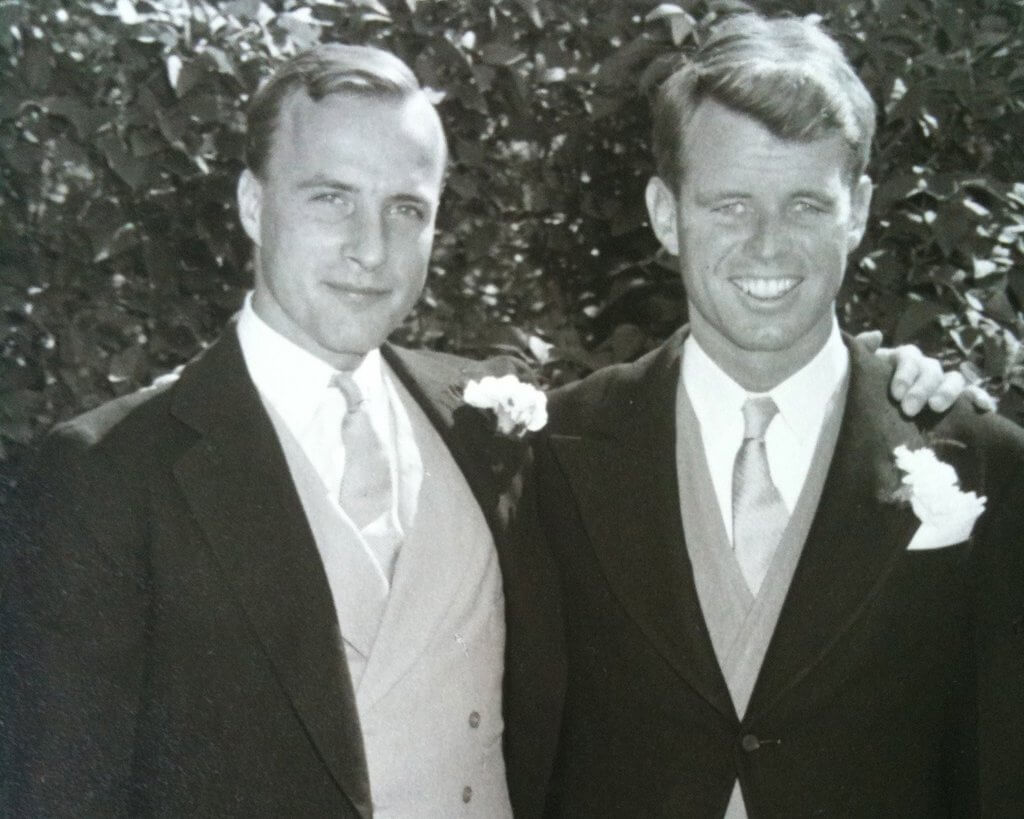

|

| David Hackett & RFK |

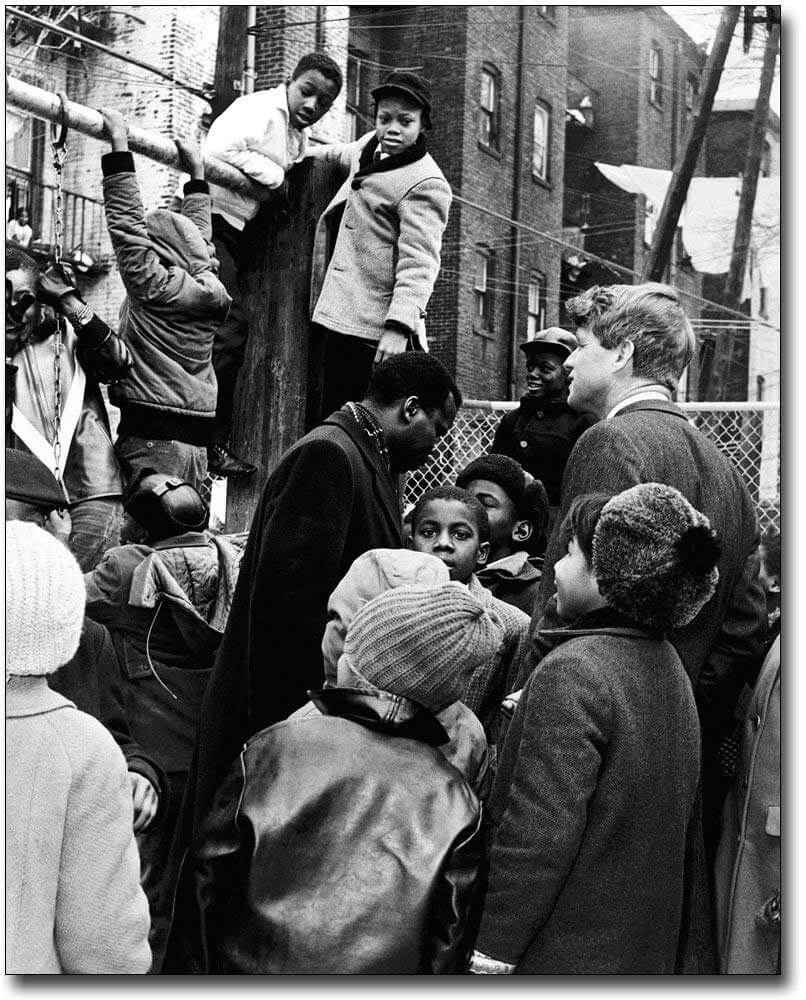

Like William Vanden Heuvel with the Prince Edward Schools crisis, Hackett was a friend of the Kennedy family. Specifically, he attended prep school with Robert Kennedy. He was such a good athlete that novelist John Knowles modeled the charismatic figure of Phineas in A Separate Peace on him. (See this bio)

Influenced by the work of his sister Eunice Shriver, one of the first things Robert Kennedy did as attorney general was to take a dual interest in the rights of the poor to have attorneys and also the problems and causes of juvenile delinquency. (Edward R. Schmitt, President of the Other America, p. 68) The siblings convinced President Kennedy to issue an executive order creating the President’s Committee on Juvenile Delinquency. The committee had a three-year life span and JFK made Hackett the executive director. Hackett had a wide mandate. The attorney general wanted his friend to explore the issue in all of its dimensions and manifestations. Which he did. Sometimes he and RFK would just take a stroll through Harlem or the slum areas of Washington DC. Hackett would then introduce Kennedy to someone he knew, preferably a gang member, and the three would talk. Other times, Hackett would show RFK the shabby conditions of schools or recreation areas. The attorney general was moved by these and so he invited celebrities—Cary Grant, Chuck Connors, Edward R. Murrow—to come into those blighted neighborhoods to give talks to the kids who lived there. (Schmitt, pp. 69-70) The attorney general would also attain appropriations to repair some of these facilities.

The question that Hackett eventually began to hone in on was this: What caused the problem of delinquency? In doing so, he first reviewed the literature. He then interviewed some of the authorities in the field: for instance, sociologist Lloyd Ohlin and psychiatrist Lawrence Kumrie. He then traveled outside the east coast to the Watts ghetto and East LA barrio. (Schmitt, pp. 71-72)

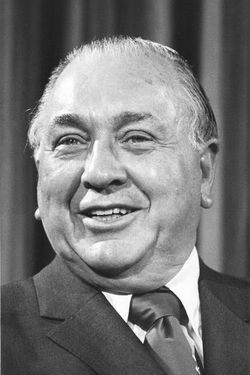

|

| Lloyd Ohlin |

After doing this research and field investigation, Hackett formulated two broad conclusions. First, he agreed with Ohlin and his approach to the subject. Ohlin co-wrote a book called Delinquency and Opportunity. That volume challenged the accepted paradigm that the problem was one of individual adjustment. It made the case that the real underlying problem was the poverty of the slum area and how that constricted opportunities for youth. To remedy the situation, one therefore had to supply more and better opportunities for youth in blighted areas. The second conclusion that Hackett came to was that this was not a simple phenomenon. What made it worse was the paucity of past efforts in the field, rendering it difficult to ensure that new programs would work. After all, Ohlin’s book had just been published in 1960. It was thus unlikely a solution could be found by the traditional remedy of starting up a series of FDR/New Deal-type programs. (Schmitt, p. 72)

|

| Leonard Cottrell |

In the latter part of 1961, President Kennedy proposed a bill that would create 16 demonstration projects funded at 30 million dollars and provide Hackett a staff of 12 full-time employees. (Allen Matusow, The Unraveling of America, pp. 111-112) A year later, when Harrington’s book came out, Eunice Shriver recommended forming a domestic version of the Peace Corps. (When Johnson enacted his War on Poverty this ended up being called VISTA.) But there was one point that Hackett disagreed with Ohlin about. The sociologist suggested a top-down schedule of opportunities that those in the community could choose to participate in, e.g., jobs for teenagers, legal services, day care centers, or local centers offering government services. Hackett brought in a new expert, Leonard Cottrell of the Sage Foundation. They decided that the choice of options should not originate from the top down, but from the bottom up. In other words, the poor should choose what they wanted to pick from. Hackett called this “the competent community”. (Matusow, p. 117)

With respect to this proposal, there are two points the reader should keep in mind. First, after doing his study, Hackett understood that there was no established meme via which to frame the problem—let alone cure it. Until the day he died, he always insisted that there needed to be continual assessment as to what was working and what was not. (Schmitt, p. 92) Related to this, Hackett wanted to expand the number of demonstration projects. He reasoned that it was necessary to test what would work with differing ethnic groups; that is, what worked in East LA might not work in South Central. After he expanded his focus from delinquency to the circumstances of poverty, he knew there was more work to be done. (Matusow, p. 121) Second, he also insisted that a pure influx of funds would not solve the problem. There needed to be research and planning behind it. He convinced Bobby Kennedy on that point. (Schmitt, p. 84)

Both men understood the urgency of the problem. From what they had read and seen, America was sitting on a ticking time-bomb. This is not after-the-fact revisionism. While everyone was concentrating on the South, Hackett and Bobby Kennedy were examining sociological predicaments elsewhere that could not be solved by an accommodations bill or a voting rights act. In these places, the problems were not simple and the remedy was not as direct. In fact, RFK predicted that riots would erupt soon if nothing was done. (Schmitt, p. 86) He told a Senate committee in February of 1963 that America was “racing the clock against disaster … We must give the members of this new lost generation some real hope in order to prevent a shattering explosion of social problems in the years to come.”

Two and a half years later, when Martin Luther King visited Watts after the riots, that was the message he had for President Johnson. (See the film King in the Wilderness) As we saw in Part 2, this was the subject—northern race relations—that Bobby Kennedy wanted to discuss with James Baldwin and his friends at their meeting in New York in May of 1963. Through the work of Hackett, the attorney general understood that the problems of discrimination in the northern ghetto were not the same as segregation laws in the South. After the riot at Ole Miss, in the fall of 1962, he told Arthur Schlesinger words to the effect: if you think this is bad, wait till you see what we are headed for up north. (Ellen B. Meacham, Delta Epiphany, chapter 3) Because the circumstances were so different, he and Hackett knew that creative ideas were needed. That is what he wanted from people like Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry and Lena Horne. He and Burke Marshall were lawyers; they did not need any advice on whether or not they could arrest the likes of Bull Connor. But they were now about to set sail on uncharted waters and they wanted some input. The fact that authors like Larry Tye and Michael Eric Dyson completely miss the hidden epic tragedy of that wasted opportunity demonstrates the kind of writers they really are. The real truth of Dyson’s pitiful book could be illustrated with an aerial picture of the Watts riots on the front cover with RFK’s words of warning on the back. That, Mr. Dyson, is what truth really sounds like.

III

Needless to say, no other administration had ever gone this far in this specific field. As author David Farber has noted, Harrington’s book—which eventually sold over a million copies—surprised America. This is one of Harrington’s most quoted passages:

The other America … is populated by failures, by those driven from the land and bewildered by the city, by old people suddenly confronted with the torments of loneliness and poverty, and by minorities facing a wall of prejudice. (The Age of Great Dreams, p. 18)

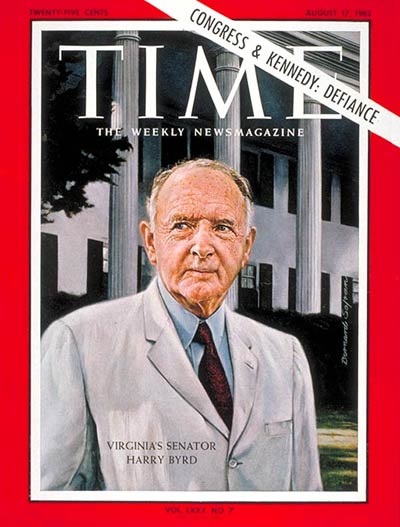

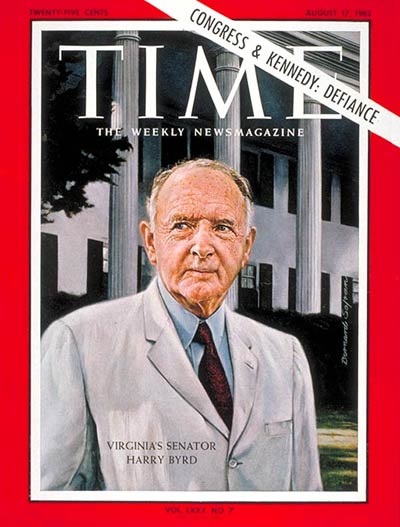

As Farber observed, the reason the book had such an impact was that during the forties, fifties and early sixties, the topic of poverty was pretty much non-existent. But in 1943, the mechanical cotton-picker displaced tens of thousands of workers, mostly African Americans, in the south. The problem was that since these laid-off workers had little skill and less education, there was no real future for them in the north. This may have been what Richard Russell had in mind when he told his colleague Senator Harry Byrd that what he feared if John Kennedy got elected was that he would go beyond even the Democratic platform. (Brauer, p. 53) The insight may have originated from Russell’s personal exposure to Kennedy while they were in the Senate. And indeed, as we have seen, that is what the president was doing at the time of his death, before his civil rights bill passed.

To crystallize how the Kennedys conceived the dilemma they would eventually face, let me quote Robert Kennedy:

You could pass a law to permit a Negro to eat at Howard Johnson’s restaurant or stay at the Hilton Hotel. But you can’t pass a law that gives him enough money to permit him to eat at that restaurant or stay at that hotel. I think that’s basically the problem of the Negro in the North. (Guthman & Shulman, p. 158)

That was not the entire problem of course. But the basic idea was that the matter was more complex and insidious once you got out of the South. As the president told Heller at their last meeting on the topic, “Yes, Walter, I am definitely going to have something in the line of an attack on poverty … I don’t know what yet.” (Schmitt, p. 93) To show how interested he was, at his final meeting with his cabinet, President Kennedy mentioned the word “poverty” six times. After his death, Jackie Kennedy took the notes of that meeting to Bobby Kennedy. The attorney general had them framed and put up on his wall. (Schmitt, pp. 92, 96)

As with many of President Kennedy’s policies, once it was assumed by Lyndon Johnson, it was changed. One of the underlying traps was what Hackett warned the Kennedys about. This problem could not be solved by constructing a New Deal program and blindly throwing money at it. As intimated above, the reason for this was that an unambiguous or certain remedy for it had not been identified. Hackett was still managing and evaluating his experimental projects, and JFK was not ready to commit to a specific program either. He wanted to do something, but he was not sure what it was.

|

| FDR & LBJ |

A significant difference in the backgrounds of Lyndon Johnson and John Kennedy is that Kennedy did not arrive in Congress until after Franklin Roosevelt’s death, while Johnson was there in the thirties. He prided himself on being a New Dealer. He ran the National Youth Administration in Texas, which meant he supervised 20,000 youths. One of his proudest moments occurred during FDR’s visit to Galveston, when Johnson had all of his boys lined up for the president’s visit. (Nancy Colbert, Great Society, pp. 36-38) Unlike what Ohlin and Harrington were writing about—and what Heller was describing to the president—Roosevelt was not facing peculiar pockets of poverty amid a generally thriving economy. FDR was confronted with a massive, nationwide economic blowout that covered almost the whole country. He was facing a macroeconomic problem: how can I revive the entire economy by using Keynesian solutions? In the meantime, he had to provide aid to literally millions of people who were unemployed. And those people crisscrossed all kinds of economic, ethnic and racial boundaries. FDR’s New Deal was like a combination giant fire engine, ambulance corps, and cafeteria truck dropping supplies and services throughout the country in an attempt to stimulate the economy, give people jobs, and provide relief programs so they would not starve.

As Hackett told RFK, this was not the situation America faced in 1962. It was much more localized and much more complicated. As we have seen, Kennedy was going to run on it in 1964 in order to transform it into a national issue. He did not plan on starting his program until after the 1964 election. (Bruce J. Schulman, Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism, p. 71) What happened after his death shows how important one man can be in determining the currents of history.

Walter Heller met with Johnson the day after Kennedy’s murder. The economist told the new president about the ideas he and JFK had reviewed for relieving poverty. Johnson told him that it sounded like his kind of program and he wanted to go full tilt on it. He then added that John Kennedy was a bit too conservative for his taste. (Schmitt, p. 96) When Heller got back to him with the demonstration projects that were running under Hackett, Johnson almost eliminated the entire program. In his eyes, such a project had to be big and bold in order to win congressional approval and make a rhetorical impact with the public. (Schulman, p. 71; Matusow, p. 123)

But there was another aspect to why LBJ trotted the program out before it was ready. The new president understood that the civil rights act making its slow way through Congress was really Kennedy’s. As I have noted, Clay Risen’s book, The Bill of the Century, proves that point. But Kennedy’s poverty program had not been formally announced or written up. Therefore, Johnson could present it as his own. (Evans and Novak, pp. 431-33) Also, like a star athlete in sports, LBJ wanted to set records in getting bills passed. (Farber, p. 106) He ended up doing both.

Just six weeks after he met with Heller, Johnson now appeared before the nation in an evening version of the State of the Union address. He announced to that nationwide audience that:

This administration, today, here and now, declares unconditional war on poverty in America … It will not be a short or easy struggle, no single weapon or strategy will suffice, but we shall not rest until that war is won. The richest nation on earth can afford to win it. We cannot afford to lose it.

This kind of rhetoric about a program whose specific points had not even been worked out yet! A bit over four months later, Johnson would announce the Great Society. Most analysts have differentiated the Great Society from the War on Poverty. The main agency for the latter was called the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). In five years, from 1965-70, OEO was granted 1.5% of the budget for all of its programs. Had that money been instead sent to each person living in poverty in America, the total would have come to about seventy dollars a year. (Maurice Isserman & Michael Kazin, America Divided, p. 192) How can you lift someone out of poverty spending that small sum? As many have said, the latter got lost and distracted by the former.

The greater expenditure on the Great Society was of particular consequence in this regard, because programs like Medicare, highway beautification, the National Endowment for the Arts, the creation of the Department of Transportation, and public broadcasting generally favored the middle class. Programs like air and water purification, and consumer protection, these favored almost all citizens. The problem with this panoply of programs was that when Johnson announced the Great Society at the University of Michigan on May 22, 1964, he did it with the same, if not more, extravagant language that he did his War on Poverty. In retrospect, what makes that even more shocking is this: Johnson had not run for president yet! For that matter, he had not even been formally nominated as the candidate of his party in the 1964 election. That would not occur for three more months, in August at Atlantic City.

In Johnson’s almost manic attempt to differentiate himself from his predecessor, what Hackett warned against was now going to happen. Johnson was going to play the New Dealer. He was going to create and pass an anti-poverty program well before the 1964 election. Yet before that was even passed, he was going to announce something even bigger: the Great Society. Needless to say, all this hubbub necessitated that the cautious Hackett be retired to the sidelines. Which he was. While Johnson was putting together his package, David Hackett—the man who ran the program for three years, who knew more about it than anyone—was now working on Bobby Kennedy’s senatorial campaign in New York. RFK tried to intervene. In January of 1964, he wrote the president a memo: “In my opinion, the anti-poverty program could actually retard the solution of these problems” unless Hackett’s basic approach was used. (Matusow, p. 123) At the time he was shunted aside, Hackett was working on something he called “competence and knowledge”. Using Ohlin’s opportunity approach, he wanted the people in these affected areas to have a complete knowledge of the opportunities at their disposal. And he wanted them to be able to designate their own leaders who could then competently use those opportunities in order to improve the lives of those they represented. It is safe to say that this was a continuation of Hackett’s dispute with Ohlin and his siding with Cottrell. Hackett wanted what he called his “community action experiments” to resemble something like a socialist democratic laboratory.

It didn’t end up that way.

IV

|

| Sargent Shriver & LBJ |

With unwise alacrity, Johnson sent his program to Congress in March of 1964. (Matusow, p. 125) As Harris Wofford notes in his book, the choice Johnson made to replace Hackett with as supervisor of his War on Poverty surprised many people. On February 1, 1964, he appointed Sargent Shriver to lead it. (Wofford, p. 286) As Wofford further writes, what was so surprising about this was that Shriver already had a position in the administration. He was running what many saw as a great success: JFK’s Peace Corps. Why have him running two programs? Why not make directing the War on Poverty a full-time job? With someone like, say, Bill Moyers running it?

Later in the year, Heller would also leave the White House. What made that decision worse was that Heller wanted to preserve much of what Hackett had done, whereas Shriver did not believe in the community action program, which was Hackett’s central idea. Shriver memorably said, “It will never fly.” (Wofford, p. 292) But he couldn’t kill it, since Robert Kennedy was still attorney general. Instead, he added other elements to it: a job training program, a summer jobs program, a work-study program, assistance to small farms and small business, and the aforementioned VISTA program. This brought in other parts of the administration, like the Department of Agriculture and the U. S. Office of Education. Bobby Kennedy had targeted help for pre-school children that would bypass the regular school system. This is how Head Start and Upward Bound entered into the overall program. (Schmitt, p. 114) These were probably the two best parts of the entire OEO schedule.

But what quickly became one of the problems with the overall program was a lack of administrative oversight. When Johnson turned it over to Shriver, he said, “You just make this thing work. I don’t give a damn about the details.” (Isserman & Kazin, p. 109) As Bruce J. Schulman noted in his book about Johnson, the president did not speak very much or spend any amount on the oversight or administration of the Great Society or the War on Poverty. (Schulman, p. 95) He argues that Johnson understood that the sooner underlying problems were exposed, the sooner Congress would cut back on them. So, in essence, he tried to ignore them. The other problem was the visible and vocal disagreement about Hackett’s ideas for community action.

As almost every commentator on the subject has observed, what came to be called the Community Action Program (CAP) fell prey to forces on the right and left. Hackett always said that he was not done fully defining what the program should be at the time he left. But he and Bobby Kennedy did agree on a stricture called “maximum feasible participation.” (MFP) This was their way of keeping the CAP democratic and also out of the hands of the local and state bureaucracies that had already failed their citizens in these areas. Another reason Kennedy tried to push MFP was that he knew that veteran local politicians would see the OEO money as simply a bounty they could get to and then spend on their own favorite programs, which did not benefit the people he and Hackett wanted to help.

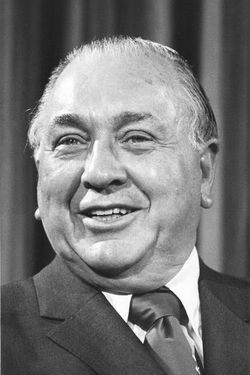

|

| Richard Daley |

He was correct. Mayor Richard Daley said, “We think the local officials should have control of this program.” (Matusow, p. 125) Another city official said, “You can’t go to a street corner with a pad and pencil and tell the poor to write you a program. They don’t know how.” (Farber, p. 107) That last comment was nonsense. Hackett did not envision the citizenry writing the programs. He wanted the local poor to be able to vote on what kind of opportunities they should have through their community action grant. But it showed why Hackett and Kennedy feared that CAP would be taken over by already standing local agencies.

When RFK arrived in the Senate, he had the opportunity to debate one of Daley’s cronies on this issue. Like Daley, the Chicago schools superintendent argued that the education programs of OEO should be taken over by his school district. Senator Kennedy then asked, if that occurred, what would safeguard the targeted children’s rights to get the benefits of the grants? The superintendent’s answer was that it would be the school community in the form of local groups of parents. From his experience in walking the streets of Harlem with Dave Hackett, the senator replied thusly:

Many of them do not have parents. They do not have two parents anyway. They might have one parent, and maybe they have a group in the community that is going to come down and make their protest known; but a lot of times that is very difficult. They are working for seven or eight dollars a day and making forty or fifty dollars a week. It is difficult to take off and go down and protest … I think we have a special responsibility to those people who are less fortunate then we are, to make sure that the money that is being expended is going to be used so that the next generation will not have to have these kinds of hearings. (Schmitt, pp. 115-16)

Later, RFK continued in this vein by saying:

The institutions which affect the poor—education, welfare, recreation, business, labor—are huge, complex structures, operating outside their control. They plan programs for the poor, not with them. Part of the sense of helplessness and futility comes from the feeling of powerlessness to affect the operation of these organizations. (Matusow, p. 126)

What Kennedy and Hackett were saying was rather simple: How can we trust the same people who allowed these inequities in the first place with the millions meant to cure them? (Schulman, p. 94) Author Schulman then listed a few examples that proved the Hackett/Kennedy warning. To cite one: a Camden New Jersey physical education program was subsidized with OEO money, yet it was a class for middle class students. I can also state from my own experience that such was the state of affairs. At the high schools I worked at which were entitled to what is called Title 1 funds, the administration tries to get the faculty behind a program that will benefit the majority of the students. As I recall, there was never any consideration given to targeting the students that Hackett and Kennedy wanted to single out and help. Many commentators concluded that this problem stemmed from the lack of oversight Johnson built into the program. (Schulman, p. 95)

|

| Kenneth Clark |

The other problem was something that was not foreseen by Hackett and Kennedy. In some cities, the CAP was taken over by, let us say, some persons on the left who also did not understand its original aims. In Harlem, respected sociologist Kenneth Clark was forced out and Livingston Wingate spent a lot of money producing the street plays of Leroi Jones. When the board argued about these productions, Wingate brought in some thugs to intimidate them. (Matusow, pp. 257-59) Wingate paid himself 25 grand a year, close to two hundred thousand today. When Kenneth Marshall, a civil rights worker who worked with Clark, examined the program records, he said he simply did not think that many of the offerings were useful. And most of the 20 million disappeared without a trace left behind. (Matusow, p. 260)

V

This is not to say that the whole thing was a boondoggle, as, for reasons of agitprop, some on the right have claimed. As noted, there were some good programs designed for the poor and underprivileged: Head Start, Upward Bound, and Legal Services, for example. And in some places, the CAP concept did succeed as it was designed. For instance, in Ellen Meacham’s book Delta Epiphany, she describes a community action center she was familiar with. It was in Mississippi and it was called Coahoma Opportunities. It offered what Hackett had envisioned. It maintained an array of services that would aid those who needed them: tutors who could help young children learn to read, Legal Services as a way to claim Social Security benefits, help with emergency food aid, placing a child in Head Start, a guide to gaining a summer job, job training that paid while you were learning, and help in finding a credit union. The reason it worked was because it had fine leadership. Aaron Henry was the head of the state branch of the NAACP, and his partner was a local white businessman who saw the program benefiting the business community and contributing to racial harmony. (Meacham, chapter 8) That is what Hackett wanted the CAP to be. The problem, as I have tried to state, was not so much the concept as its execution.

Eventually the administration gave in to the local and business leaders on CAP. By 1967, Johnson had folded his cards on community action. He allowed them to be taken over by the local entities Hackett feared. Shriver left to become ambassador to France. In the end, LBJ had lost all faith in it and said it was being run by “kooks and sociologists”. (Matusow, p. 270)

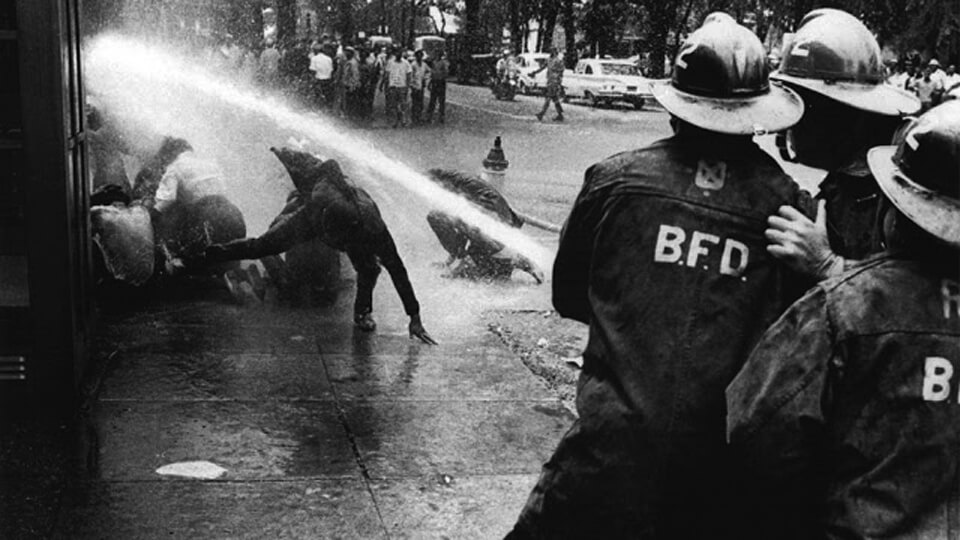

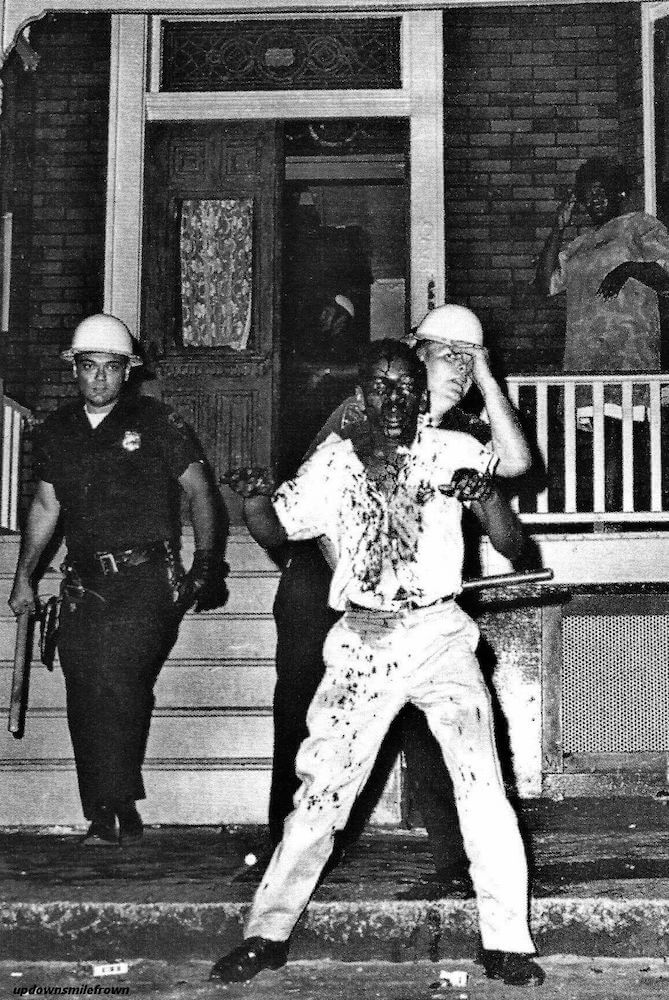

The beginning of Johnson losing faith started in Watts in the late summer of 1965. To his credit, I have never read anything that states that Bobby Kennedy had his “I told you so” moment at this time, even though, as we have seen, he did predict it. On August 11, 1965, a slightly drunken motorist, Marquette Frye, who was on parole for robbery, was stopped and pulled over by a highway patrolman, Lee Minikus. Frye resisted arrest. As he did, a crowd began to gather at the intersection of Avalon and 116th Street. It quickly swelled to a thousand. The police had to call in reinforcements. The crowd began hurling rocks and bottles. They then began to shout the chant that became the chorus to the hundreds of riots that would soon follow: “Burn, baby, burn.” (Matusow, p. 360)

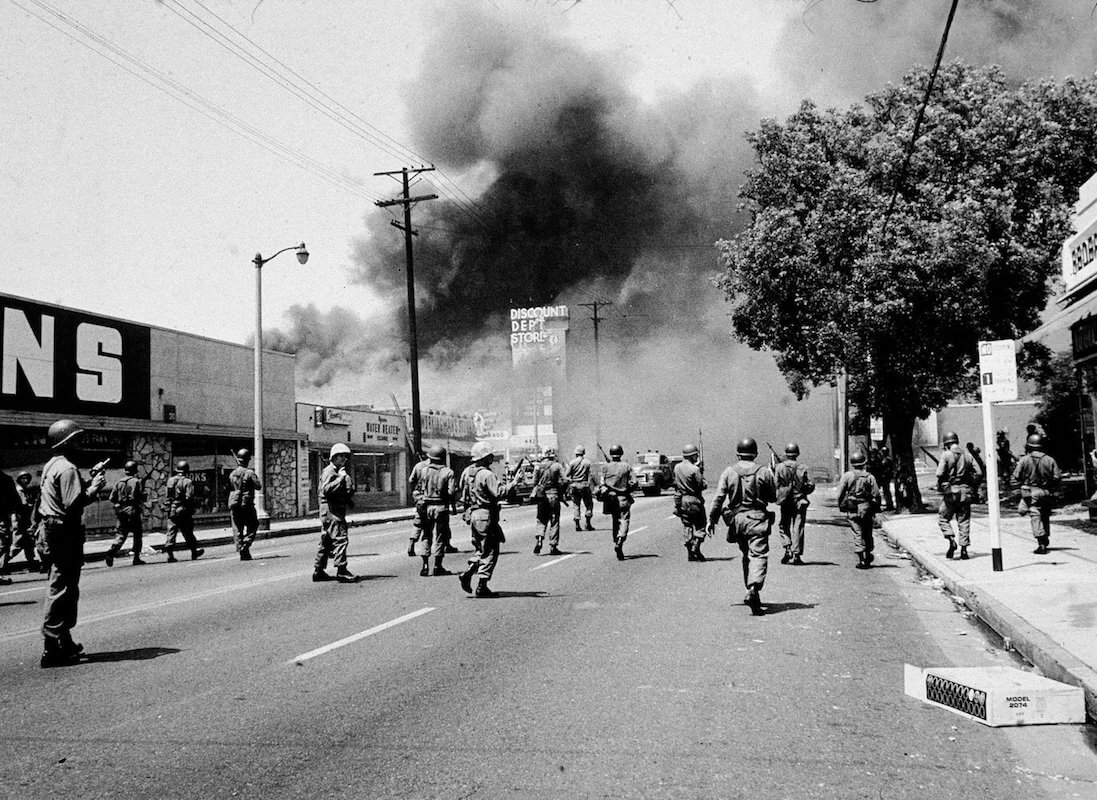

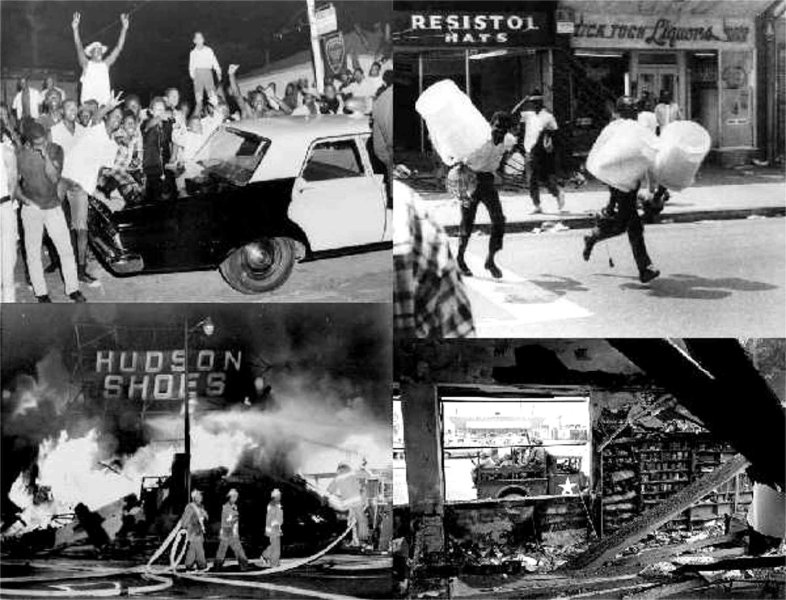

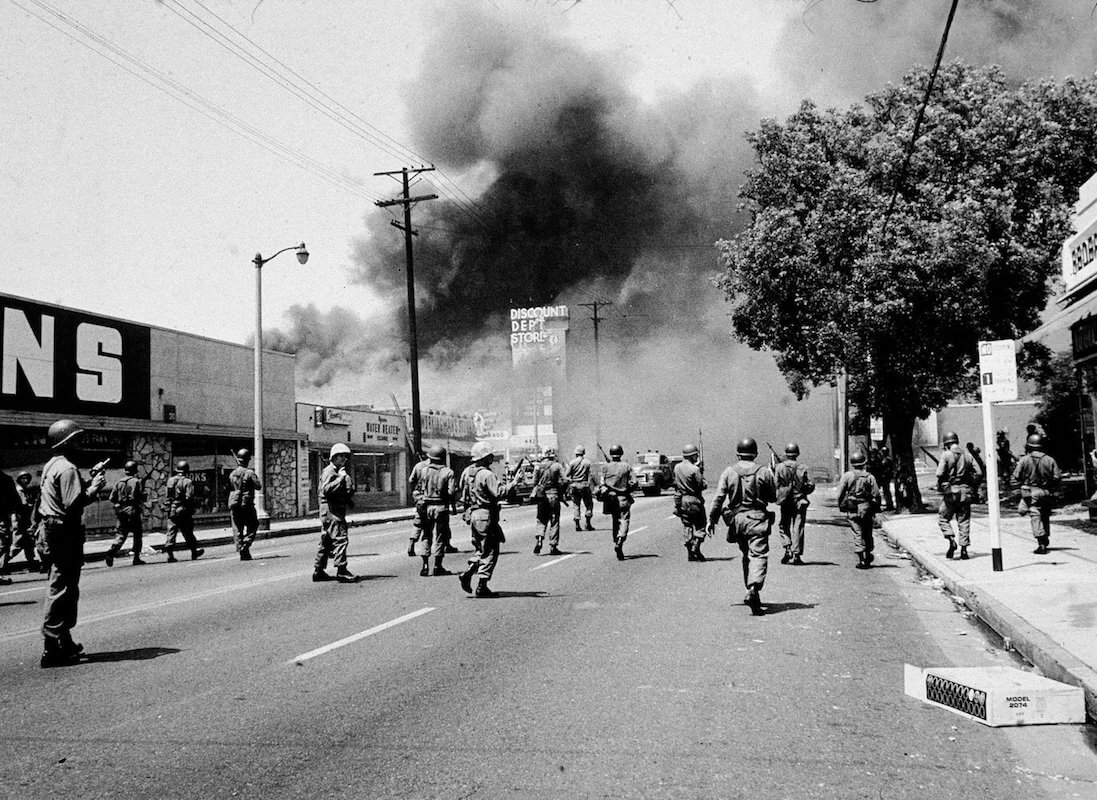

|

| Watts 1965 |

During the next six days, a 46-square-mile section of Los Angeles turned into a battle zone. The conflagration raged for the better part of this period. At one time or other, nearly 30,000 residents participated in the looting, sniping and torching. A crowd estimated at 60,000 cheered them on. The local authorities called in 2,300 National Guardsmen. They were sent in on the fourth day and this started to bring things under control. (Matusow, p. 361) They joined a force of about 1,700 local and state police. When it was all over, there were 34 dead, 1,072 injured, 977 buildings damaged, and nearly 4,000 arrests.

Johnson was stunned by Watts. It exploded just one week after he had signed into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It was King’s Selma demonstration that had made that act possible. But both men had cooperated in the process. According to his chief domestic aide, Joe Califano, after Watts, LBJ refused to take King’s calls for a period of 24 hours: “He just wouldn’t accept it. He refused to look at the cables from Los Angeles describing the situation.” (Schulman, p. 112) When he came out of it, Johnson asked, “How is it possible, after all we’ve accomplished? How could it be?” (Schmitt, p. 120) Politically, the riots handcuffed the president. He had to issue a statement condemning the looting and lawlessness, but he also understood that if he went too far, a backlash would now ensue against the War on Poverty.

Why did Watts explode? To its residents, the arrest of Frye seemed to symbolize what the white community of Los Angeles thought of the neighborhood. Nearly 2/3 of Watts high school students had flunked at least one grade; almost that many had dropped out. Forty per cent of its residents had no cars, which in a commuter city made it tough to find a job. African American unemployment was three times that of whites. (Farber, p. 113) Bobby Kennedy commented on this police symbolism when he said the law did not protect those in the ghetto from paying too much for inferior goods; from having their furniture repossessed, or “from having to keep lights turned on the feet of children at night to keep them from being gnawed on by rats.” (Schmitt, p. 120)

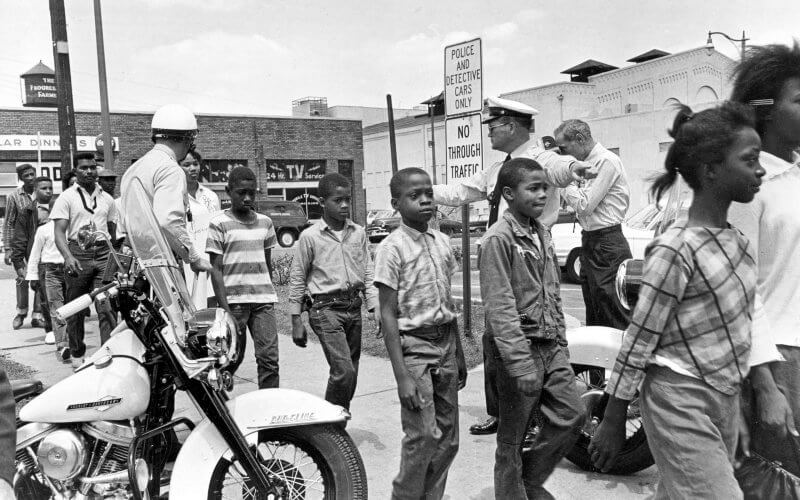

|

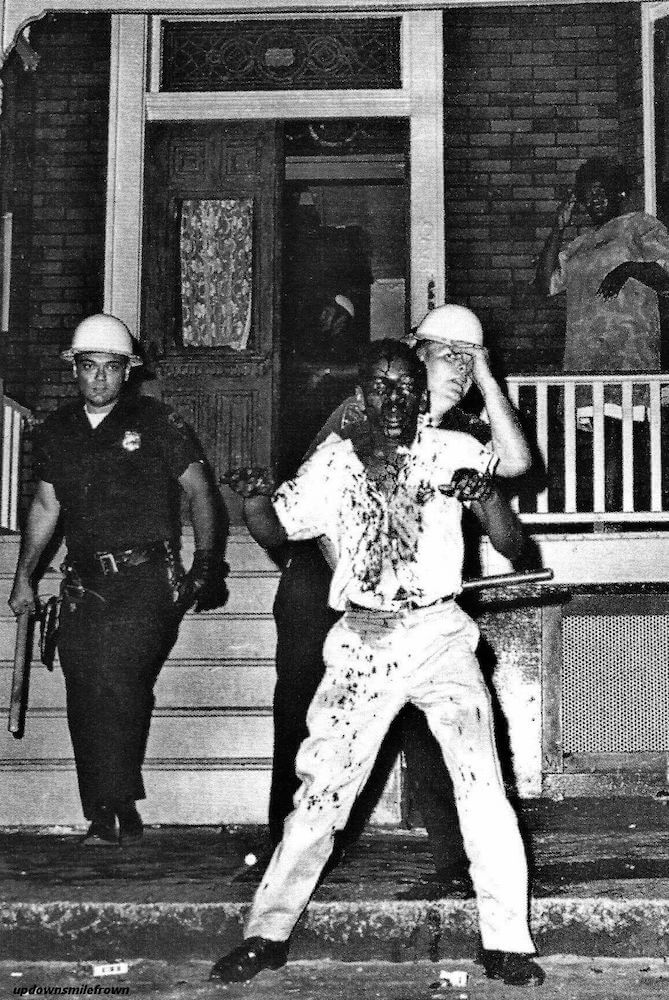

| Detroit 1967 |

The volcanic eruption in Watts initiated an annual series of rolling explosions of summer riots, most of them in the north. In 1966, 43 urban ghettoes went up in flames, in 1967 there were 167 incinerations, in 1968, there were over 125. (Farber, p. 115; “The Legacy of the 1968 Riots,” The Guardian, April 4, 2008) In 1967, eight American cities were occupied by the National Guard. (Matusow, p. 362)

|

| Newark 1967 |

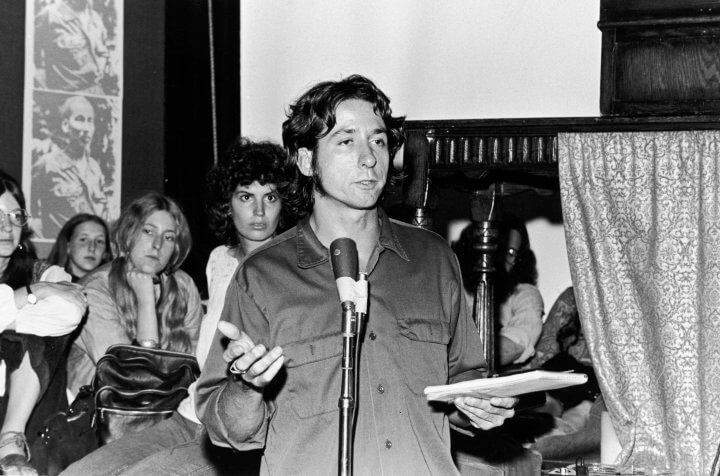

The 1967 Newark and Detroit riots actually surpassed Watts in their ferocity. In Newark, the violence resulted in a maelstrom: the Guardsmen were firing on police and the police returned fire. The Guardsmen then fired into a housing project, killing three women. The governor called in SDS leader Tom Hayden, who had done a study of inner-city Newark. Hayden told him to withdraw the Guard. A few hours later, things calmed down. (Matusow, pp. 362-63) One week later, on July 23, 1967, the worst riot in a century broke out in Detroit. Governor George Romney had to request the White House send in the army to quell the insurrection. It ended with 43 dead, 7000 arrested, 1,300 buildings burned down and 2,700 businesses looted. (Matusow, p. 363)

|

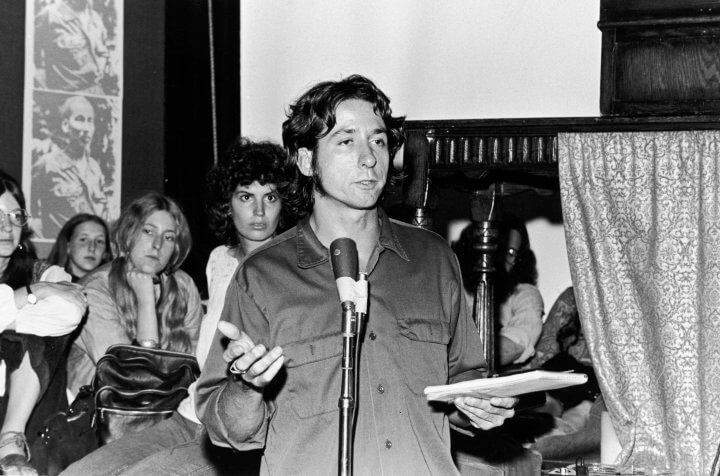

| Tom Hayden |

By 1966, both King and longtime civil rights lawyer Joe Rauh had split with Johnson. (Randall Woods, LBJ: Architect of American Ambition, p. 699) One reason for this was that Johnson—with America going up in flames—continued to escalate in Vietnam, thereby contributing to student unrest and devoting a huge amount of money to a senseless war that neither Rauh nor King could understand. A war that, at that time, was killing or wounding an inordinate number of men of color. King later decided to memorialize the War on Poverty:

A few years [ago] there was a shining moment, as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor. Then came the build-up in Vietnam, and I watched the program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war … So I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such. (Isserman & Kazin, p. 192)

But Johnson insisted that he could still do all three; that is, wipe out poverty, build his Great Society and fight a large land war in Indochina—and win all of them. He said as much in his January 12, 1966 State of the Union address. This contributed to his growing credibility gap—for the simple reason that very few people saw it that way, especially with more and more cities being incinerated while more and more troops were coming home in body bags. All of this caused another sociological and historical milestone to manifest itself.

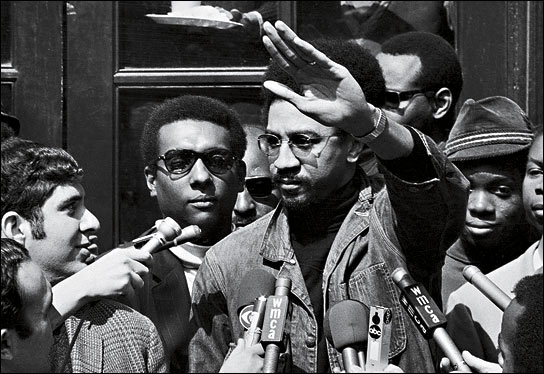

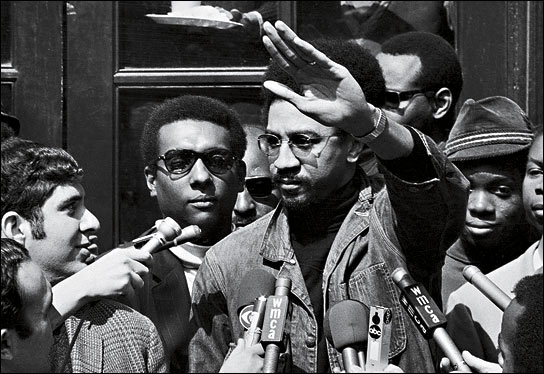

|

| Stokely Carmichael & H. Rap Brown |

As the country seemed to be spinning out of control, not only did this contribute to the rise of rightwing backlash and demagoguery (e.g., Alabama Governor George Wallace entering the national scene); it also contributed to the rise of a leftwing militancy, both in the civil rights movement and the student protest movement. We thus witnessed the appearance on the scene of people like Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown in the former and Bernardine Dohrn and the Weathermen group in the latter. In 1966, Carmichael directly confronted King on a march in Mississippi with his new slogan, “Black Power”. He later said that integration was a “subterfuge for the maintenance of white supremacy.” He then added that people of color would not be beaten up anymore: “Black people should and must fight back.” (Matusow, p. 355) Carmichael, and later Brown, meant this to be their version of the militancy and separatism of the late Malcolm X. First Carmichael and then Brown used this extremism to take over the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. (Isserman & Kazin, pp. 174-75) Apparently, few members noticed that this approach contradicted what their acronym stood for. Carmichael—who wanted to start an “anti-imperialist guerilla war in the ghetto to free the Afro-American colony”—was directly responsible for inciting riots after speaking engagements. (Matusow, p. 365)

Johnson responded to this by going first to the CIA and starting up Operation MH/CHAOS. When he did not like the results he got there, he went to the FBI, and reactivated COINTELPRO. These were illegal spying programs on these two groups, which also utilized subversive operations to destabilize them. (Schulman, p. 146) Coupled with this, in the fall of 1967, he also made an appearance in Kansas City for the International Association of Chiefs of Police. (Matusow, p. 215)

Bobby Kennedy was not taking that path. In early 1967, he met with SDS founder Tom Hayden for an exchange of ideas. Hayden later said that Kennedy wanted to get the networks to run documentaries on what life was really like in the ghettoes. He also wanted them to broadcast what the real poverty statistics there were. (Schmitt, p. 175) Six months later, when Detroit erupted, Kennedy predicted this would be the death knell of the Great Society. When Senator Kennedy tried to propose a new package of bills, the White House refused to back it. (Schmitt, p. 190)

The White House also failed to back its own proposals. In the wake of Newark and Detroit, Johnson had appointed what he called the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. This was helmed by Illinois governor Otto Kerner and was therefore referred to as the Kerner Commission. It was composed of some visionary personages, for example Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts and Congressman Jim Corman of California. On February 29, 1968, they handed in their remarkable report. Its most quoted passage asserted that America was becoming “two societies, one black and one white—separate and unequal.” (Joseph A Palermo, In His Own Right, p. 161) One of its recommendations was to adopt ideas similar to RFK’s: a triangular union of private business, government grants and community leadership to rebuild impoverished communities. Both Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King were disappointed that Johnson pretty much ignored the report and its guidelines. (Palermo, pp. 161-62)

As many have commented, it was this splitting of the Democratic/liberal coalition over the issues of Vietnam and urban rioting which gave the GOP/conservative coalition their golden opportunity to break it asunder. Conservative strategists like Kevin Phillips and Pat Buchanan began to write up plans to do so. (Isserman & Kazin, pp. 216-17, 272-73) In 1967-68, the promise of 1963-64 became a distant memory. Politicians like Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon now went to work on their “law and order” themes in the shadows and smoke of Watts, Detroit and Newark while the Living Room War raged each night on TV and the police clubbed SDS protestors in the streets. What caused it all to be even more made-to-order for the right wing is reflected in a comment by Johnson to Bill Moyers after he signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The president remarked, “I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for my lifetime and yours.” (Schulman, p. 76)

Inspired by the example of George Wallace, Republicans like Nixon and Reagan strove to siphon off the racist vote in the South. This resulted in Nixon’s infamous Southern Strategy, and Reagan’s equally infamous appearance at the Neshoba County Fair in Mississippi in 1980 to kick-start his campaign. The location of that fair was just seven miles from the site where the bodies of three murdered civil rights workers had been found sixteen years prior (Read further about this here). This technique has been a standby for the GOP ever since, and has been amplified to new levels by Donald Trump.

VI

We will oppose … with every facility at our command, and with every ounce of our energy, the attempt being made to mix the white and Negro races in our classrooms. Let there be no misunderstanding, no weasel words, on this point: we dedicate our every capacity to preserve segregation in the schools.

~Virginia Governor James L. Almond Jr.

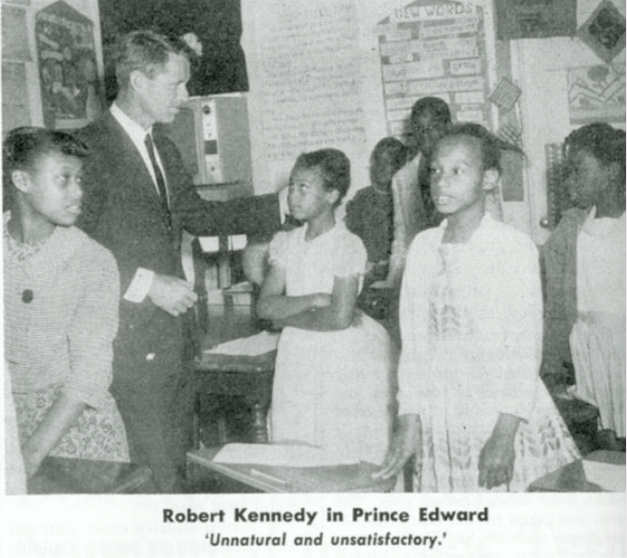

I would like to close this series by discussing two fascinating and important projects that get little detailed attention, either by the MSM or even in academia. The first deals with a topic that we discussed in passing in Part 3: the Prince Edward County Schools crisis. The second is a subject not addressed yet: Robert Kennedy’s Bedford Stuyvesant restoration.

As I, and many others, have shown, President Eisenhower and Vice-President Nixon did next to nothing to support or enforce the Brown decision. This holds true when it was first announced in 1954, and when it was restated in 1955. The decision made by the Republican administration was unfortunate, since without any enforcement, the Brown case now became a rallying cry for the rightwing establishment in the South. What is worse, as we have also shown: when Eisenhower and Nixon did mention it, it was with disdain.

In Virginia, the state legislature mounted a policy of “massive resistance”. In 1958, following the Orval Faubus example in Arkansas, schools were closed rather than allow African American students to register. When this policy was overturned by the courts, Prince Edward County officials defied the decision. The County Board of Supervisors decided to cut off funding to the Prince Edward Schools altogether. Private academies for white students now opened which excluded pupils of color. This policy was upheld by Richmond newspaper columnist James Kilpatrick and his good friend William F. Buckley.

As a result, Prince Edward’s African American students had no schools to attend. In other words, rather than integrate and obey the law, the power brokers in Virginia, egged on by Kilpatrick, resurrected the claims of John C Calhoun: interposition can override the central government. What made this all the worse was that, as Nancy Mclean notes in her book Democracy in Chains, it was a 1951 walk-out protesting segregated schools that caused Prince Edward to be included in the Brown v Board filing. (Mclean, p. 6)

|

| Harry F. Byrd |

Consequently, students of color decided to cross over into North Carolina, or find relatives elsewhere who would let them move in, to continue their education. (Lee, p. 2) At this time, Senator Harry Byrd was one of the dominant forces in Virginia and he vigorously opposed the Brown decision. Along with Governor Almond, this made Virginia—even though it was in the upper South—quite reactionary. As analyst V. O. Key wrote at the time, “Compared to Virginia, Mississippi is a hotbed of democracy”. (Lee, p. 14) Local liberal leaders appealed to the White House to enter the fray in some way. Eisenhower actually encouraged the creation of the white private schools. (Lee, pp. 49-50)

The Byrd/Almond nexus was quite powerful. Religious ministers did not speak out for fear of being transferred. When an education administrator complained, he was forced to resign. When Almond tried to sell the former schools, which were now empty, half the school board resigned. (Lee, pp. 68-74) Professors who wrote against these decisions were spied upon, harassed and sometimes fired. (Lee, p. 78) But that still was not enough. With the likes of Kilpatrick leading the way, laws were now passed to outlaw the NAACP in the state. And the agency was now forced to turn over its membership rolls. (Lee, p. 79) In 1960, when a 13-year-old who had been out of school for a year wrote the White House, the reply was he should express his feelings to the local officials. (Lee, p. 90)

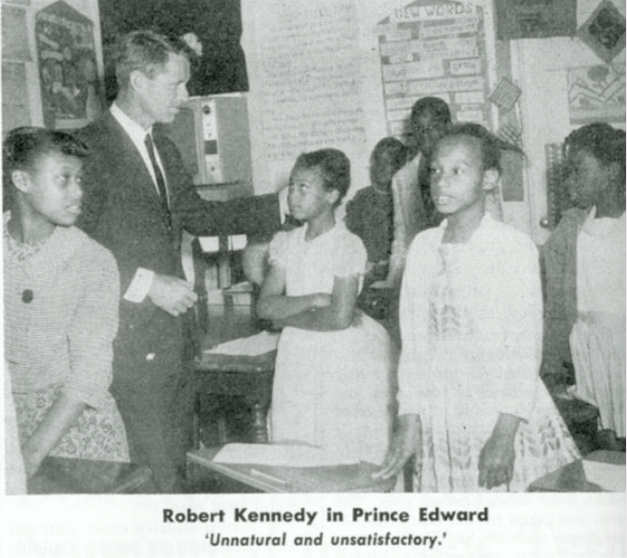

Two months after President Kennedy’s inauguration, Robert Kennedy called the Virginia attorney general to Washington for a meeting. When that did not get very far, a month later RFK and Burke Marshall filed a suit to join the legal action. As one commentator has written, the filing of the Kennedy/Marshall lawsuit all but stopped the Byrd/Almond movement to close down all public schools. (Lee, p. 156) The problem was that the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals was not as law-abiding as the Fifth Circuit in the Deep South, so the progress in gaining favorable decisions was much slower, at least until President Kennedy was allowed to appoint two of his choices to that court. (Lee, p. 100)

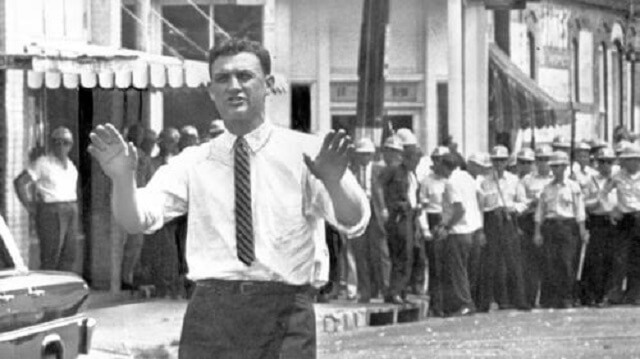

|

While all this stalling was going on, the Kennedys decided to make a bold, unprecedented move. JFK had told Burke Marshall he wanted to make Prince Edward a high priority. (Lee, p. 258) In February of 1963, after President Kennedy mentioned the Prince Edward case in his civil rights speech, the Kennedys decided to erect a new school system in Prince Edward, from grade school through high school. (Lee, pp. 33-34) As he did with Dave Hackett, Bobby Kennedy recruited a friend, William Vanden Heuvel, and gave him the assignment of creating the Free Schools system out of nothing in Prince Edward. (Lee, p. 292) By this time, four years had gone by. Some students did not even know how to hold a pencil. (Lee, pp. 314-15)

|

| William Vanden Heuvel |

Vanden Heuvel, with Bobby Kennedy and the president backing him all the way, did the seemingly impossible. He secured 1.2 million in grants and hired an integrated school faculty and staff with Dr. Neil Sullivan as his superintendent. Sullivan got threatening phone calls, and his car was shot at. Some children were afraid to come to school since they had no shoes or proper attire. Vanden Heuvel got them the clothes. There was a remarkable class ratio of 12-1 in the high school. The system opened on September 16, 1963 with nearly 1,600 students, including four whites. The Free Schools were an oasis in the desert. It showed what could be done in the face of complete adversity.

|

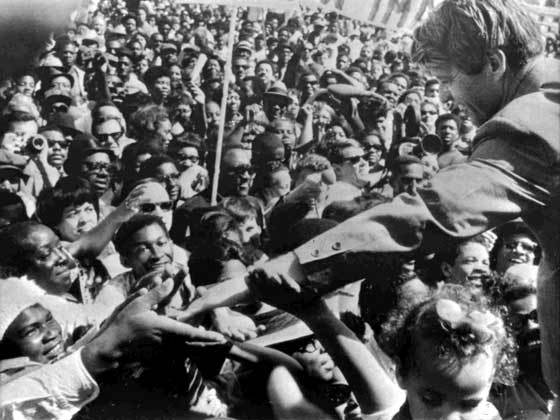

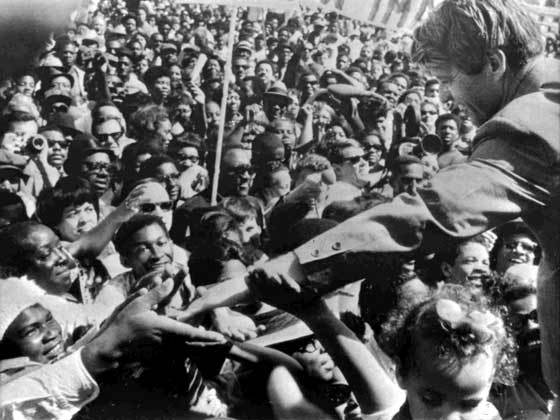

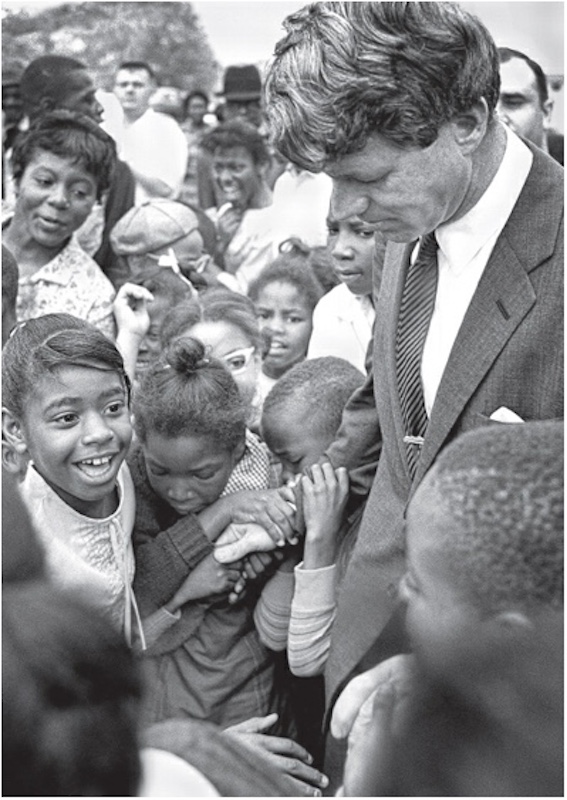

| RFK in Watts |

RFK visited Watts in November of 1965. When he returned, he told a couple of his staffers, Ed Edelman and Adam Walinsky, to continue with Hackett’s research, but to take it a step further. He wanted ideas on how to address the entire phenomenon of the urban ghetto and how to structurally transform it. They did so, and in January of 1966, the senator gave three speeches on the subject of race and poverty. (John Bohrer, The Revolution of Robert Kennedy, pp. 255-61) Those speeches marked the birth of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration project. It was RFK’s answer to Lyndon Johnson and the New Deal.

Bedford Stuyvesant was a ghetto in the Brooklyn area of New York. It had a population of 400,000. This made it the second largest ghetto in America outside the south side of Chicago. It covered 9 square miles. There was no hospital, college or local newspaper. After he gave his speeches, the senator asked Walinsky and Edelman to start fashioning a project for Bedford Stuyvesant that would put those ideas into action. Bobby Kennedy’s idea was to form a tripartite partnership between the federal government, businesses and foundations, and the residents, to transform the area and revive it.

|

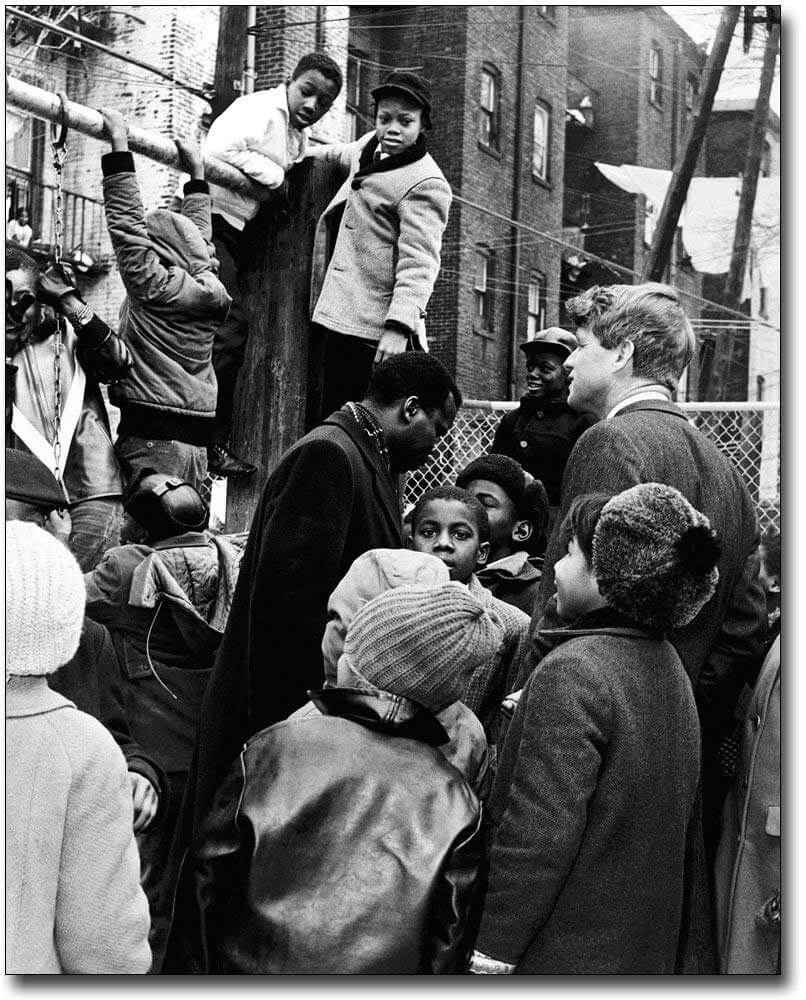

| RFK in Bedford Stuyvesant |

He first got the business community to chip in by going to people like financier Andre Meyer and IBM chairman Tom Watson. He also secured foundation grants. (Schmitt, p. 151) He used that money to hire the local unemployed to do restoration for the fronts of local homes, a program that ended up being exceedingly popular. (Schmitt, p. 162) The plan’s next step was to push for tax incentives in order to get businesses to move there. He also attained a mortgage pool of money that allowed residents to secure low down payment FHA loans to finance real estate deals. He brought in a Dodge car lot. He got Watson to locate a factory there. He even convinced the City University of New York to open a branch, which was later named Medgar Evers College. (Schmitt, p. 165) John Doar became the chief executive officer of the restoration.

|

Restoration Plaza

The Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation

was established in 1967 as one of the first community

development corporations in the United States. |

He announced the formation of what he called the community development corporation on December 10, 1966 at Public School 305 in Bedford Stuyvesant. He said that he was now going beyond community action in order to gain the power to act with “the power to command resources of money, mind and skill.” (Schmitt, p. 155)

The Bed-Stuy project was a qualified success, not a total success as the Prince Edward School District was. The reason it did not attain that instant stature was that Bobby Kennedy got involved in the 1968 race for the presidency. Yet, apart from whatever may currently be occurring there, no less than Michael Harrington once stated concerning this project, “It is extremely satisfying to witness a social idea that works.” (Schmitt, p. 166) The CDC idea was in fact widely imitated. Today there are over 4000 of them, and companies that specialize in that field. Bobby Kennedy and Dave Hackett made a formidable reply to Johnson’s New Deal. One that has echoed down through the decades.

VII

Whatever the ambitions of these four authors were, as the reader can see, their efforts to belittle what the Kennedys did for civil rights do not stand up to scrutiny. Instead, upon actual inspection, they simply reveal their own poverty. (Again, I would make a mild exception in this regard for David Margolick.)

As Harrington said of RFK, “As I look back on the sixties, he was the man who actually could have changed the course of American history.” (Wofford, p. 420)

Journalist Pete Hammill wrote RFK before the presidential race of 1968:

I wanted to remind you that in Watts, I didn’t see pictures of Malcolm X or Ron Karenga on the walls. I saw pictures of JFK. That is your capital in the most cynical sense. It is your obligation in another, the obligation of staying true to whatever it was that put those pictures on those walls. (Schmitt, p. 221)

As Brenda Luckett, one of the young African Americans Bobby Kennedy saw in the impoverished Mississippi delta in 1967, said after his death, “We felt like Kennedy was purged. He should have gotten out. It’s like we knew they were going to kill him for helping black people.” (Meacham, chapter 12)

Charles Evers, brother of the murdered Medgar, said of him, “Mr. Kennedy did more to help us get our rights as first class citizens than all of the other US attorney generals put together.” (Arthur Schlesinger, A Thousand Days, p. 976)

But this sentiment had been previewed several years earlier. During the Freedom Riders’ episode, when King arrived in Montgomery, the citizens rallied to him and realized that something new was afoot. One youth said, “President Kennedy is on our side.” A woman said, “Bless God! We now have a president who’s going to make sure we can go anywhere we want like the white folks in this country.” (Brauer, p. 103)

Unfortunately, it did not last very long. One is left to imagine what America would be like today if President Kennedy had lived, and Bobby Kennedy and Dave Hackett had run the War on Poverty. Without Vietnam, and those men in charge, it is even possible that America would not have burned.

A Summary of Major Points Made by this Essay

- Reconstruction ended up as a failure for the liberated slaves of the South. And due to several odd and adverse Supreme Court decisions afterwards, the Reconstruction laws and amendments were neutralized. (Part 1, section 1)

- From 1876 to 1932, no president did anything to alleviate what had occurred in the South thanks to the rise of the Redeemer movement. In fact, some of them clearly sided with that movement. (Part 1, section 2)

- Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, respectively, passed the FEPC law and integrated the military under pressure from the prominent civil rights leader Philip Randolph. But they were constricted from doing much else by the southern bloc in Congress and the threat of a filibuster. (Part 1, section 3)

- Charles Hamilton Houston began the modern civil rights movement by initiating a systematic challenge to the Supreme Court decision in Plessy v Ferguson. This ended in the epochal Brown v Board decision. (Part 1, section 3)

- Because of the Brown decision, Dwight Eisenhower had an opportunity to move in a major way on the issue, since he won two resounding victories in 1952 and 1956. For political purposes, he and Richard Nixon largely avoided the issue. (Part 1, section 3)

- Senator John Kennedy was not enthralled by southern interests on the race issue. This is shown by his 1956 public statement of support for Truman’s civil rights bill; his speech declaring his support for the Brown decision in 1957; his vote for Title III of the civil rights bill, also in 1957, and his reference to the issue in several speeches in the 1960 campaign. (Part 2, section 1)

- Senator Kennedy addressed the issue during the 1960 campaign several times, accentuating its moral dimension. He spent several moments criticizing the Eisenhower administration on their performance during his second debate with Richard Nixon. (Go to the 13:45 mark here)

- President Kennedy did not delay in addressing the problem once he got into office. In fact, he got to work on it his first day, originating an affirmative action program that would eventually spread across the entire expanse of the federal government. (Part 2, section 3)

- It was not possible to pass an omnibus civil rights bill in 1961. The evidence in support of that conclusion is overwhelming. (Part 2, section 1)

- It was also not possible to alter the filibuster rules in 1961. The Democrats had tried to do this prior to Kennedy, and they tried to do it several times after Kennedy’s death. It was not achieved until 1975. (See pages 6 and 7 of this paper)

- Attorney General Robert Kennedy took on school desegregation within weeks of entering office and did things in that regard in New Orleans and Prince Edward County, Virginia that Eisenhower had never done. (Part 3, section 1)

- The Kennedys worked closely with the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in order to ensure voting rights, integrate colleges and enforce the Brown decision. Again, this had not been done prior to 1961. (Part 3, sections 2 & 5)

- JFK extended fair hiring practices to contracting companies who did work for the federal government and private colleges which got research grants from Washington. This helped integrate business and higher education in the South. (Part 3, section 3)

- The Kennedy administration did more to advance civil rights in three years than the prior 18 did in nearly a century. This is simply a matter of record. (See the chart at the end of Part 3.)

- Kennedy tried to get a civil rights bill on voting rights in 1962 but he could not defeat the filibuster. (Part 3, section 3)

- In February of 1963, Kennedy announced he had gone as far as he could through executive orders and the judiciary, and that he was submitting an omnibus civil rights bill to Congress. (Part 3, section 6)

- The implications of the encounter between RFK and James Baldwin in May of 1963 have been wildly distorted and pulled out of context. The discussion Kennedy wanted to have with those attending that meeting concerned what he had been working on with David Hackett: ways to approach racism and discrimination in the north. Baldwin and Jerome Smith hijacked the agenda and thereby wasted a golden opportunity. The danger of an eruption of inner-city violence, which Kennedy predicted and wished to talk about, was confirmed 27 months later with the Watts riots. (Part 2, section 3; Part 3, section 4; Part 4, section 2)

- Due to Fred Shuttlesworth’s highly publicized demonstrations in Birmingham, JFK’s confrontation with George Wallace in Tuscaloosa, and his televised speech on the subject, the February 1963 bill was redrawn and strengthened. It eventually passed in 1964 due to the efforts of RFK, Hubert Humphrey and Thomas Kuchel, not LBJ. This eliminated Jim Crow. (Part 3, sections 5 & 6)

- John Kennedy was working on an attack on poverty before his civil rights bill was sent to Congress. This effort had begun in 1961 with the research of David Hackett on the issues of poverty and delinquency. (Part 4, sections 1 & 2)

- LBJ appropriated that program as his own, and retired Hackett. He started it up before the research was completed. It ended up being taken over by interests who did not center it on the people it was designed for. The mishandling of this program, it could be argued, exacerbated the issue, and, as Bobby Kennedy predicted, America descended into a nightmare of riots and killings for four straight summers, 1965-68. (Part 4, section 5)

- Republican strategists Kevin Phillips and Pat Buchanan advised candidates on how to use this violence to manipulate white backlash and break up the Democratic Party coalition. Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan did so, and this strategy, which has been used ever since, has risen to new heights under Donald Trump. (Part 4, section 5)

A Selected Bibliography

- Jack Bass, Unlikely Heroes. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981.

- Patrick Henry Bass, Like a Mighty Stream. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2002.

- Michael Berman, The Politics of Civil Rights in the Truman Administration. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1970.

- Irving Bernstein, Promises Kept. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- John Bohrer, The Revolution of Robert Kennedy: From Power to Protest after JFK. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2017.

- Herb Boyd, Baldwin’s Harlem. New York: Atria Books, 2008.

- Carl M. Brauer, John F. Kennedy and the Second Reconstruction. New York: Columbia University Press, 1977.

- Thurston Clarke, JFK’s Last Hundred Days. New York: Penguin Press, 2013.

- Andrew Cohen, Two Days in June. Toronto: Signal, 2014.

- Nancy A. Colbert, Great Society. Greensboro, NC: Morgan Reynolds, 2002.

- Charles Euchner, Nobody Turn Me Around. Boston: Beacon Press, 2011.

- Rowland Evans & Robert Novak, Lyndon B. Johnson: The Exercise of Power. New York: New American Library, 1966.

- David Farber, The Age of Great Dreams. New York: Hill & Wang, 1994.

- Eric Foner, with Joshua Brown, Forever Free. New York: Knopf, 2005.

- Harry Golden, Mr. Kennedy and the Negroes. Greenwich, CT: Fawcett, 1964.

- Lawrence Goldstone, Inherently Unequal. New York: Walker and Company, 2011.

- Edwin Guthman & Jeffrey Shulman, Robert Kennedy in His Own Words. Toronto: Bantam, 1988.

- Maurice Isserman & Michael Kazin, America Divided. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- William P. Jones, The March on Washington. New York: W. W. Norton, 2013.

- John F. Kennedy, Profiles in Courage. New York: Avon, 1956.

- Brian E. Lee, A Matter of National Concern. Unpublished Ph. D. thesis. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 2015.

- David Leeming, James Baldwin: A Biography. New York: Knopf, 1994.

- Nicolas Lemann, Redemption. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2005.

- Nancy MacLean, Democracy in Chains. New York: Viking, 2017.

- Allen J. Matusow, The Unraveling of America. New York: Harper & Row, 1984.

- Ellen B. Meacham, Delta Epiphany. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2018.

- Diane McWhorter, Carry Me Home. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001.

- Joseph Palermo, In His Own Right. New York: Columbia University, 2001.

- Clay Risen, The Bill of the Century. London: Bloomsbury Press, 2014.

- Arthur Schlesinger, Robert Kennedy and His Times. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1978.

- Arthur Schlesinger, A Thousand Days. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

- Edward R. Schmitt, President of the Other America. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2010.

- Bruce J. Schulman, Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism. Boston: Bedford Books, 1995.

- Frank Sikora, The Judge. Montgomery, AL: River City Publishing, 1992.

- Theodore Sorenson, Kennedy. New York: Harper and Row, 1965.

- Harris Wofford, Of Kennedys and Kings. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1980.

- Randall Woods, LBJ: Architect of America Ambition. New York: Free Press, 2006.