I

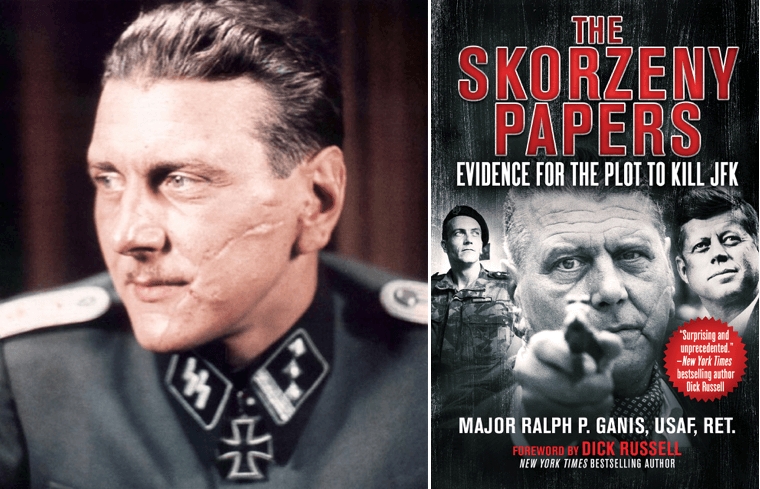

When I heard that a previously undiscovered collection of personal correspondences from SS Colonel Otto Skorzeny had recently surfaced, I was truly interested. Besides his famous exploits in WWII, including the daring mountaintop rescue of Benito Mussolini and the kidnapping of Hungarian regent Miklós Horthy’s son from his Bucharest palace, Skorzeny was infamous for his postwar dealings with a number of intelligence agencies the world over. As a child, my grandfather, Marcel, a French resistance fighter, used to tell me stories of Otto’s exploits during car rides. I thought I was in for a real treat when I found this book. That Skorzeny could have had a hand on the team that killed President Kennedy was also an interesting hook.

The subtitle of this book is “Evidence for the Plot to Kill JFK,” and therein lies its true problem: if by evidence we are referring to clear-cut forensics, incriminating memos, newly declassified documents, newly discovered tapes, or reliable eyewitness testimonies that place Skorzeny either at the scene or in a position directly responsible for the assassination of JFK, then we have little to no “evidence” to justify the book’s subtitle. What the author of the book, Major Ralph Ganis, USAF (retired) seems to suggest is largely tangential to the actionable plot that took Kennedy’s life; that is, Skorzeny, from his position in Madrid as a jack of all trades with ties to postwar Nazis, Texas oil moguls, the Mossad, and French intelligence operatives, could have been a link in a long and winding chain of figures who eventually connected to those who executed the crime of the century. And yet, as we will see, even that supposition is largely based on fantastical leaps of logic, a primary source base that we are never allowed to verify—or see a picture of, or direct reference to—and a conclusion that is not only ridiculous but insulting to the JFK research community.

Dick Russell, who wrote the introduction to The Skorzeny Papers, rightly claims that the book provides a “chronological tracing of the dark alliances that sheds fresh light on how long-suspicious CIA officials like William Harvey and James Angleton wove Otto Skorzeny into their tangled web, or vice versa.” I will give Ganis and Russell that—most of the book is largely this, an extremely dry, almost colorless list of dozens and dozens of figures who were responsible for placing Skorzeny in a secure position from which to run his operations after the war: within only a few pages in chapter seven we have “Enter Major General Lyman L. Lemnitzer and the NATO Link,” “Enter Clifford Forster,” “Enter Don Isaac Levine.” I like to think I have a pretty good memory, but the sheer volume of second- and third-string players in this book is bewildering, with connections seemingly drawn from any and all personnel affiliated with anything remotely clandestine, few of which are ever revisited, and none of which seem truly important given the book’s central thesis, which is that Otto Skorzeny was somehow a key aspect of the Kennedy assassination.

The so-called “Skorzeny Papers,” which Ganis acquired through an American auction house bid in 2012, are alleged correspondences between Skorzeny and some of these underworld and intelligence-based figures, along with letters to his wife, who aided him in his dirty work to some degree. “As the story goes, many of the papers were burned over time, but a fragmentary grouping of documents (the ones used for the research in this book) survived. The archive ranges from 1947 to around the period of Skorzeny’s death.” (xv).

But since we are not allowed to view them or translate them from the German ourselves, we must take the author’s word that they are not mistranslated or even fraudulent.

Ganis begins his book’s preface with a bold proclamation: “Why was President John F. Kennedy killed and who carried it out? All of the investigations, commissions, and academic works have not answered these questions. This book integrated startling new information that does resolve the mystery.” (p. xxi) Let’s unpack that for a moment. Not all commissions are equal. The Warren Commission is not the same as Jim Garrison’s investigation of Clay Shaw, the HSCA, or the later ARRB. The latter three found quite compelling evidence that a domestic intelligence outfit indeed murdered JFK. The former was staffed by Allen Dulles and was essentially a disinformation campaign whose objective was to obfuscate the truth and put the story to bed for the nightly news, which had also been compromised through the Central Intelligence Agency’s media liaisons. As much has been exhaustively detailed in scholarly works, from John Newman’s Oswald and the CIA, to Jim DiEugenio’s Destiny Betrayed, to Jim Douglass’ JFK and the Unspeakable. That we cannot say with certainty who pulled the trigger on the fatal shot so vividly captured in the Zapruder film is ultimately inconsequential; for all intents and purposes, given the time elapsed since that fateful November afternoon fifty-five years ago, we do have a clear picture of the likely suspects behind the plot’s orchestration, along with compelling motives for why JFK was targeted. Bold claims like Ganis’s require even bolder evidence, and to open with a whopper like that, one would presume that Skorzeny’s purported personal papers contain something akin to the map of Dealey Plaza’s sewer system that investigators found in Cuban exile Sergio Arcacha Smith’s apartment, or a handwritten “thank you” note from James Angleton after the Warren Commission had ended for services Skorzeny rendered to the CIA. And yet not only is Otto Skorzeny himself only a tangential part of a book entitled The Skorzeny Papers, but the “evidence for the plot to kill JFK” is awkwardly squeezed into the last two pages of a 346-page work, with a final revelation that made me both angry for investing hours of my life reading the tome, and confused as to how an author with a true breadth of working knowledge about postwar intelligence networks could presume so myopic an assassination motive.

II

Otto Skorzeny was an Austrian by birth who joined the Nazi party somewhat reluctantly, mainly as a way to make a living as the outbreak of the Second World War ramped up in the late 1930s. A mechanic by trade, and a semi-professional fencer, his notorious scar across his face from a missed parry and his 6’4 stature made him something of an icon in the German army. Skorzeny was known for his fearlessness, guile and unconventional approach to commando warfare. As he once said in a postwar interview, “My knowledge of pain, learned with the sabre, taught me not to be afraid. And just as in dueling when you must concentrate on your enemy’s cheek, so, too, in war. You cannot waste time on feinting and sidestepping. You must decide on your target and go in.” (Charles Whiting, Skorzeny, 1972, p. 17) In many ways, his belief that small units could actually move world history in a similar or even greater fashion than regiments and divisions was affirmed after his thirty-man glider-borne SS unit spirited away Mussolini from the Gran Sasso Hotel with not even a single shot fired. Even Winston Churchill heaped praise on him for his bravery in the face of incredible odds.

Rearranging signposts during The Battle of the Bulge, his commandos, who wore captured American uniforms and spoke fluent English with almost no accent, attempted to sow chaos behind Allied lines, seeking to misdirect troops and armored units away from key areas. While the entire Wacht am Rhein [“Watch Along the Rhine”] operation, which was the German code name for Hitler’s last desperate gamble to capture the Belgian port of Antwerp and cut the British and American forces in two, was ultimately a futile dying gasp of an already-defeated Nazi war machine, it proved so devastating to Allied morale (and killed 75,000 Americans) that some planners did reconsider whether the war would be over any time soon. And when a handful of Skorzeny’s men were captured in their false uniforms during that bitterly cold winter of 1945, panic spread throughout SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force), leading to a comical scene in which General Eisenhower frantically argued with his staff who insisted he station twenty guards with sub machine guns around his Paris office at all times in case Skorzeny tried to kill or abduct him. In the middle of the night, the future Director of the CIA, Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s aide-de-camp, ran out with his staff in pajamas and started firing his carbine into the brush just beyond the headquarters’ window.

He and his men later found the dead cat that had been scurrying about in the dark, but the legend of Otto Skorzeny had taken hold.

Dubbed “the most dangerous man in Europe,” Skorzeny finally surrendered to the Allies in occupied Germany, after seeing the futility of carrying out Hitler’s final order for his “werewolves” to continue the war after the end of hostilities. He was summarily booked and processed, and awaited trial for his role as a top Nazi official and a one-time personal bodyguard of Adolf Hitler. He was later approached by OSS officers as he languished in his holding cell at Darmstadt Prison and it is from this first contact that Ganis believes the true exploits of Skorzeny began. While stories differ as to the mechanics of his escape—Skorzeny claimed in his memoirs that he stole away in the trunk of a car and had a German driver unwittingly smuggle him through the checkpoints; while Arnold Silver, his American point of contact and debriefer said he was released on official terms—he nonetheless was a free man by 1948. After relocating to Paris, where he was unofficially used as a conduit through which CIA officials could monitor communist activity in postwar Europe, Skorzeny was quickly identified due to his conspicuous face and looming profile, and was outed by the French press during one of his many strolls down the Champs-Elysée with his wife Ilse.

Relocating to Madrid, it is here that Ganis believes his real work began, work that—Ganis believes—would ultimately find him involved with dark forces that killed JFK a decade later. Set up in a comfortable office that saw Skorzeny ostensibly managing a construction company that also handled imports and exports of mechanical parts to places in Central Africa and elsewhere, he for all outward purposes seems to have lived a quiet life. Writing memoirs, consulting with foreign governments for a variety of clandestine work, and running a low-key commando training school whose members included some of his former comrades from the SS, French OAS soldiers, American special forces officers, and a rogue’s gallery of other unsavory characters, his postwar life had little in common with his daring exploits during WWII.

The bulk of The Skorzeny Papers deals with the nebulous formation of both the CIA and its shell companies from the remains of the OSS, with familiar figures like Frank Wisner, Arnold Silver, Bill Harvey, and William Donovan featured prominently in Ganis’ narrative. The central portion of the book meanders from French anti-communist hit teams and their American handlers, to the also newly-formed Mossad and its eventual use of Skorzeny for the removal of Egyptian nuclear scientists, to a whole host of West German ex-Nazi intelligence personnel and their largely dull exploits passing mostly fabricated evidence of an impending Soviet invasion to Washington in exchange for their freedom and a career on the American payroll. Somewhere in this tangled web, Ganis situates Skorzeny who, because of his extensive contacts and personal daring during the Second World War, seems—in Ganis’ estimation—uniquely positioned to wrangle these disparate forces into something of a rogue network that is totally off the books. Ganis reiterates this throughout the book, seeking to distinguish ostensible layers of the spy world from what he considers its truly dark realm, which he identifies as a series of assassination teams bankrolled through corporate shell organizations like SOFINDUS, which eventually morphed into the World Commerce Corporation (WCC). In The Skorzeny Papers the WCC is akin to SPECTRE from the old James Bond novels; a looming, impenetrable evil menace whose tentacles reach into almost every aspect of Cold War politics and planning, Ganis spends a considerable amount of the book detailing its creation, key operators, possible ties to international Nazi groups and ultimately its potential role as the dark budget from which Skorzeny was able to fund his various international commando operations after the war. In reality, while I’m sure this is all very interesting to someone truly looking for an exhaustive account of postwar dirty money, it has very little to do with Skorzeny, and almost nothing to do with the domestic assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dealey Plaza.

The book then delves into the French OAS, focusing on the enigmatic Captain Jean René Souètre, who of course was allegedly deported from Fort Worth, TX, the afternoon of the JFK assassination. And while I am not denying that Souètre could have indeed been on the ground in Texas in some capacity, Ganis goes to great lengths—even putting him on the book’s cover next to Skorzeny and Kennedy—to implicate him in the plot: “The actual sniper, or team of snipers, was directed by Jean René Souètre, the former OAS officer wanted by French security services for an attempt on the life of President Charles de Gaulle in 1962.” While Souètre was a known paramilitary outlaw who hated the idea of Algerian independence from France—which Kennedy firmly championed from the Senate floor in the mid 1950s—he seems from the available evidence to have been a rogue player who drifted through these turbulent times, training commandos, taking exotic posts with his OAS buddies, and advising the CIA on a handful of ultimately uninteresting developments in the Third World. To suggest, as Ganis does, that he was the lynchpin of the ground operations in and around Dealey Plaza, while ignoring the more probable Cuban exile culprits, seems strained.

The Souètre chapter ends with a few lines that reveal a frustrating and repeated aspect of this book, where the author assumes that one’s proximity to a situation necessarily guarantees association and willing complicity. For example, Ganis argues:

The movements of Skorzeny during this period point to his being in attendance at the Lisbon meeting between Souètre and the CIA. In fact, Skorzeny made several trips to Portugal between March and July 1963 concerning his businesses. With the OAS cause now unsustainable, it appears Souètre left the meeting with a new option for employment, signing on with Skorzeny. Captain Jean René Souètre was now a soldier of fortune working for Otto Skorzeny in one of the most guarded secret organizations in the history of American intelligence.” (p. 248, italics added)

It’s not at all clear that these conclusions can be verified, and as Skorzeny’s whereabouts are only deduced from “the Skorzeny Papers,” which are never directly quoted—here or anywhere in the book to my knowledge—one must once again have faith that Ganis is being honest and accurate.

III

The book then spends a considerable amount of time on the Third World and its myriad decolonization movements, with a quite lengthy digression into Ganis’ analysis of the Congo Crisis, exploring the potential for Skorzeny to have been the mysterious QJ/WIN assassin the CIA hired to kill Patrice Lumumba. Ganis takes a fairly condescending approach to his analysis of Lumumba’s rise to power, claiming “As well-founded as Lumumba’s words may have been, they were politically ill-advised. This tense atmosphere was further compounded by the lack of a plan for the organized transition to power.” (p.279). As I have detailed in my article, “Desperate Measures in the Congo,” the United States destroyed any hope for a free Congo before Lumumba had risen to anything nearing real power. In fact, both Belgium and the CIA had planned on separating Katanga, the Congo’s richest area, from the country before it became independent. Belgium had stolen the country’s gold reserves, brought them to Brussels and refused to return them. President Eisenhower refused to meet with Lumumba after the Belgians had landed thousands of paratroopers inside the country. By the time Lumumba’s plane had landed back in Africa, Allen Dulles and friends all but marked Lumumba for death. For Ganis to say he had no plan for an “organized transition to power” smacks of paternalism: given his eloquence, popular appeal and vision of a new dawn for his recently unshackled nation, Lumumba may well have succeeded if he had not been undermined in advance.

The assassination mission was later aborted when the CIA and Belgian intelligence aided Katangese rebels with Lumumba’s capture after he fled his UN protection in a safe house. While I can see where Ganis is going, and how it could be possible, given that Skorzeny seems to have been in the Congo around this time, to my knowledge it’s been pretty strongly established that QJ/WIN, the CIA digraph of one of two selected assassins for the Congo plot, was actually Jose Marie Andre Mankel. To have sent a person as instantly recognizable as Otto Skorzeny into an unfolding international crisis involving the Soviet Union, Belgian and Congolese troops, U.N. officials from multiple nations, and American station personnel seems, to put it mildly, unwise. Indeed, WI/ROGUE, another CIA-sponsored hit man and agent sent on the assignment, had had plastic surgery and was said to be wearing a toupee during his visit. No matter Skorzeny’s connections to Katanga Province’s mining operations, which were real, he was more likely a visiting business opportunist rather than an actionable agent during the Congo Crisis, if he was present there those critical weeks surrounding Lumumba’s capture and execution at all.

Ganis then details Skorzeny’s one brief interview with a Canadian television program in September 1960, in which he boasts about being in high demand by both the enemies of Fidel Castro and Fidel himself, explaining a plot which he takes credit for being the first to discover. This was Operation Tropical, in which the CIA was allegedly training Skorzeny and his commandos for a kidnapping of the Cuban premier in early 1960. Ganis bases his description on an unnamed newspaper clipping found in the papers he secured in his winning auction bid. Curiously, I happened upon Operation Tropical in a perusal of the CIA’s online reading room months before I’d read this book, and searched in vain for the newspaper they cite as having outlined the plot, which they claim is the Sunday supplement edition of the Peruvian newspaper, La Cronica, dated August 7, 1966. I would be interested to read it if anyone can secure a copy. It would go a long way in verifying the validity of Ganis’ main body of evidence, and would be an interesting find for researchers more broadly. In any case, with the aborted Castro plot and a mainstream boilerplate description of the “failed Bay of Pigs invasion,” which of course Ganis attributes to Kennedy’s refusal to release nearby carrier-based air support (something Kennedy staunchly forbade before the operation was underway, a point which Ganis’ omits), we now enter the final stretch of the book, which looks directly at Skorzeny’s role in the JFK assassination.

Spoiler alert—there is none.

IV

“General American Oil Company,” “Colonel Gordon Simpson,” “Algur Meadows,” “Sir Stafford Sands,” “Colonel Robert Storey,” “Jacques Villeres,” “Permindex,” “Judge Duvall,” “Paul Raigorodsky,” “Thomas Eli Davis III,” “ Robert Ruark,” “Jake Hamon,” and about twenty other sub-headings flash across the first dozen or so pages of the final chapter of The Skorzeny Papers. The organization of the book centers on these disjointed, one-to-two-page sub-chapters which give the reader the disorienting and queasy feeling of reading it through glasses with the wrong prescription. Not only did Ganis miss the opportunity to style the life and times of Nazi Germany’s most infamous commando personality along the lines of a thrilling narrative, with exotic locales and shady deals over drinks and cigars, but he arranged the book in so awkward a fashion that he constantly has to end sentences with “and we will get back to him shortly,” or “and I will show you how this ties in later.” Even if one were to storyboard his entire panoply of tertiary personalities, it would look more like a Jackson Pollock art installation than a coherent plot with a compelling impetus culminating in the JFK assassination as we understand it. A story should be clear enough to draw the reader in with its simple facts, and should sensibly unfold on its own accord so as to prevent the need to constantly handhold during the descent into the labyrinth.

Conspicuously absent in The Skorzeny Papers are any substantial sub-headings detailing Cuban exiles, Allen Dulles, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, or any of the genuine suspects of the JFK assassination, save for meanderings on James Angleton’s and Bill Harvey’s roles in the creation of Staff D, the CIA’s executive action arm. Ruth and Michael Paine are nowhere to be found. Neither is a description of the aborted Chicago plot, or any substantive explanation of how Lee Harvey Oswald was moved into the Texas School Book Depository, or a note about David Phillips’ role in the whole affair from his Mexico City station. While these very real aspects of the actual JFK plot are infrequently touched upon in passing—Ganis cannot ignore the entire body of evidence, despite his best efforts—he insists on crow-barring his newfound “primary source data” into a story that at this point doesn’t permit much unique interpretation. It’s safe to say, in 2018, that President Kennedy was assassinated by a domestic, military-industrial-intelligence apparatus that viewed his foreign policy as anathema to both the “winning” of the Cold War and to their image of the United States’ role in world affairs. That Kennedy was a staunch decolonization advocate, a friend and champion of Third World leaders like Sukarno in Indonesia, Nasser in Egypt, Lumumba in the Congo, and sought diplomatic solutions to prevent the impending nuclear Armageddon with Nikita Khrushchev’s Soviet Union is all but ignored in Ganis’ conclusions as to why JFK was shot in Dallas. None of it is suggested. What ultimately led to the tragedy in Dealey Plaza, according to Ganis, is something much bigger.

V

It all comes down to JFK’s sexual indiscretions, folks. That’s right. Jack Kennedy just couldn’t resist the advances of the hundreds of femme fatales who threw themselves at him, and according to Ganis, the high command had to take him out when he cavorted with the ultimate Cold War honeypot.

I wish I were kidding. But unfortunately I’m not.

The author submits to the reader that the act to assassinate President Kennedy was carried out for reasons that far exceeded concerns over U.S. National security. In particular, they arose out of a pending international crisis of such a grave nature that the very survival of the United States and its NATO partners was at risk. At the source of this threat was breaking scandals that unknown to the public involved President Kennedy. To those around the President (sic) there was also the impact these scandals had on the president’s important duties such as control of the nuclear weapons and response to nuclear attack. It also appears the facts were about to be known. The two scandals at the heart of this high concern were the Profumo Affair and the Bobby Baker Scandal. (p.294)

I will spare anyone reading this a rebuttal of the relevance of this assertion, but suffice it to say, Ganis places the final straw at Kennedy’s—demonstrably disproven—affair with Eastern Bloc seductress Ellen Rometsch. Ganis claims, “Historians are taking a hard look at this information, but preliminary findings indicate Rometsch was perhaps a Soviet agent.” (p.295) He continues, “Her potential as a Soviet agent is explosive since Baker had arranged for multiple secret sexual liaisons between her and President Kennedy.” (p. 295)

He then scrapes together a weird narrative of how Attorney General Robert Kennedy was pleading with J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI to withhold these revelations in a “desperate effort to save his brother and the office of the presidency.” (p.296), He argues that “As President Kennedy was arriving in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963, a very dark cloud of doom was poised over Washington, and the impending storm of information was hanging by a thread.” (p. 296). That’s when Skorzeny—from Madrid—was activated to save the Western world. It seems pointless to add that retired ace archive researcher Peter Vea saw the FBI documents on this case. The agents had concluded there was no such liaison between the president and Rometsch. In other words, to save himself, Baker was trying to spread his racket to the White House. Bobby Kennedy called his bluff.

Ganis pretentiously concludes, “In the end, the assassination network that killed JFK was the unfortunate legacy of General Donovan’s original Secret Paramilitary Group that included as a key adviser from its early inception—Otto Skorzeny. Furthermore, the evidence would seem to indicate Skorzeny organized, planned and carried out the Dallas assassination, however, we may never know what his exact role was.” (p. 342)

Indeed we may never, because there does not seem to be any. Ganis continues, “On November 22, 1963, an assassination network was in place in Dallas; it was constructed of associates of Otto Skorzeny and initiated by his minders in the U.S. Government and clandestine groups within NATO.” Wrapping up, the author reiterates, “The events that led to this killing were triggered by a limited group of highly placed men in the American government. They were convinced that the West was in imminent danger and posed to suffer irreparable damage, and, for some of them, imminent exposure to personal disgrace beckoned. All of this sprang from reckless debauchery in the White House and beyond. With the situation breached by Soviet intelligence and ripe for exploitation, it became untenable for this group. They took action.”

I’ll give you a few minutes now to wipe the tears from your eyes. Okay, good. Are you still with me? Overall, The Skorzeny Papers could, I suppose, serve as something like a compendium or glossary for those who just have to know the minutest details of the inner workings of this or that shell corporation that may or may not have had a hand in some world affair during the Cold War. But there are much better books on that. Ultimately, Ganis’ book is an uncomfortable, freewheeling careen down strange dead-end tracks, with unannounced detours through cold dark streets full of faceless characters, and later, journeys through mirror-filled fun houses of speculation, with a final twist and turn that spits you out right over Niagara Falls, barrel and all.