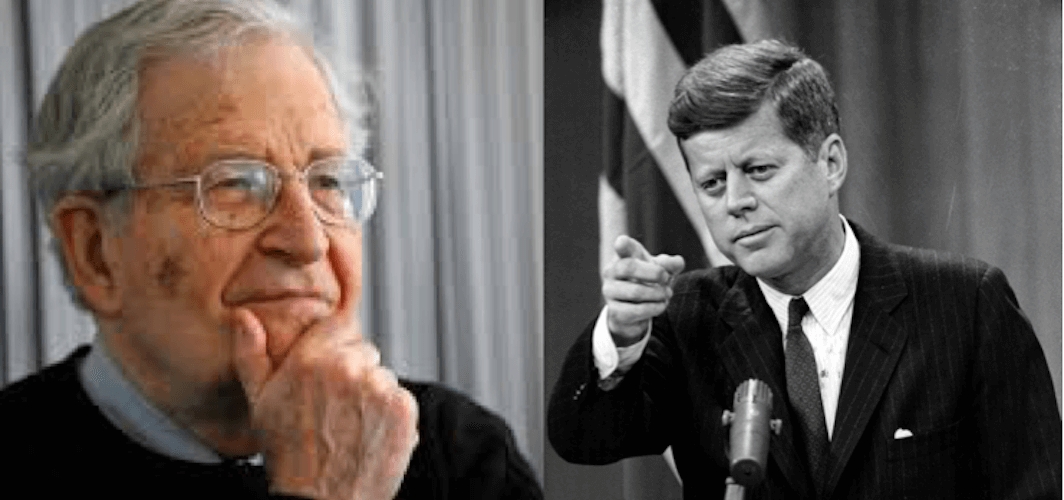

One of the most telling moments in John Barbour’s new film, The American Media and the Second Assassination of John F. Kennedy, is his presentation of Noam Chomsky briefly discussing the JFK case. It’s a scene I will return to later. But along with Barbour’s depictions of Dan Rather and Bill O’Reilly, I thought these formed the most potent scenes in his film. I am glad Barbour depicted Chomsky because it reminds us just how bad the so-called American Left was and is on both the Kennedy assassination and his presidency. I once wrote an essay on this general subject based upon the work of Martin Schotz and Ray Marcus. (Click here for that essay) Like the Chomsky scene in the Barbour film, we will later return to Marcus’ revealing work on Chomsky.

As many of us will recall, at the time of the release of Oliver Stone’s film JFK, Chomsky, along with his deceased cohort Alexander Cockburn, went on a jihad against almost everything depicted in the movie. Their critiques were as bad, in some ways worse, than those of the MSM. Their campaign was two-pronged. The first angle was to promote the idea that the Warren Commission was correct; that is, Oswald alone shot President Kennedy. In this regard, Cockburn obsequiously interviewed Warren Commission counsel Wesley Liebeler in the pages of The Nation. That interview amounted to a pattycake session, as Cockburn served up softball after softball to his performing seal Liebeler. Their second line of argument stemmed from the first: There was no high level plot because President Kennedy was no different than Dwight Eisenhower who preceded him, or Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon who followed him. So, with both polemicists, there was no political difference between, say, Kennedy and Nixon, Kennedy and Eisenhower, or Kennedy and Johnson. Even back in 1991, this was a difficult dual thesis to uphold. With the releases of the Assassination Records Review Board, it is well-nigh impossible to defend today. And later we will see how new evidence has forced Chomsky to modify his position. (For my discussion of Cockburn click here)

There were so many crevices—actually Florida-sized sinkholes—in their arguments that it became apparent that both men were arguing from a preconceived position.

That position, of course, is the approach to history common to the intellectual or academic Left. One might characterize the general tendency of such Marxist-influenced (or Neo-marxist) sociological analysis as ‘structural’ or ‘system-oriented’, in the sense that it views the actions of individuals as having little import or consequence, that the subject is merely an agent of larger cultural forces that impinge upon it. When applied specifically to the realm of politics, it leads to positing that institutions of power seek to protect and perpetuate themselves in a manner which is nearly blind to the choice or consciousness of the participants, that indeed the very status of the acting subject is suspect as a category of analysis. In its most extreme application, this theoretical perspective leaves no room for flexibility, for the notion that biography—personal background and characteristics—can make a difference, or that innovation from within the system can occur that can benefit many rather than a few. This concept differs somewhat from the “deep state” thesis, as advocates of the latter will allow for exceptions. But they will then note that the Deep State will correct the exception. In President Kennedy’s case, it was a correction by assassination. The former view is more rigid and zealous in its ideology insofar as it denies that there can be any political exceptions. As with extreme upholders of all theories, its proponents must work to erase the evidence that there ever were any exceptions. And as with any kind of inductive reasoning based upon dubious premises, this leads to the making of some thunderous—and pretentious—truisms.

II

Before we address some of Chomsky’s pronouncements on the Kennedy case, it is important to address some of his intellectual background, because it is very hard to adhere to such a system of thought without it leading to some thorny practical problems with specifics. This is simply because theories sometimes do not explain all that happens in the real world. Therefore their practitioners are forced to bend and mold facts and events in order to shape them to fit their doctrine. In the political field, this practice usually leads to questions of how ideology influences analysis. In other words it brings up questions of bias and balance. Chomsky’s career gives us prior illustrations of these characteristics. It is startling to note how Chomsky’s acolytes ignore them.

The first is the fact that Chomsky has been known to butcher quotations for political advantage. A famous example being a quote by Harry Truman which Chomsky altered in his early book American Power and the New Mandarins. This was later exposed by Arthur Schlesinger in a letter to Commentary in December of 1969. Another example would be the misconstruing of the words of Harvard professor Samuel Huntington. Chomsky wrote that the professor said that he advocated demolishing in toto North Vietnamese society. Huntington corrected the record in the New York Review of Books (See 2/26/70)

There are parallels to these kinds of ersatz presentations with Chomsky and the Kennedy case. With Kennedy, Chomsky has tried to insinuate that somehow JFK was involved with the assassination of Patrice Lumumba of the Congo. This wasn’t possible for the simple reason that Kennedy had not been inaugurated at the time Lumumba was killed. But further, as some have noted, Allen Dulles and the CIA most likely hastened their assassination plots against the African leader for the precise reason that Dulles knew Kennedy would not support them. (John M. Blum, Years of Discord, p. 23) In fact, there is a famous picture of President Kennedy getting the news of Lumumba’s death which shows just how pained he was by Lumumba’s passing.

In and of itself, this photograph nullifies the Chomsky thesis that there was no difference between Eisenhower, LBJ, Nixon and Kennedy. For we can safely say that none of those other men would have reacted like this upon hearing of Lumumba’s death. According to the Church Committee, Eisenhower and Allen Dulles ordered the murder of Lumumba. (The Assassinations, edited by James DiEugenio and Lisa Pease, p. 326) Lyndon Johnson reversed Kennedy’s policies in the Congo. He ended up using Cuban exile pilots to wipe out the last followers of Lumumba, helping to destroy the first attempt at a democracy in post-colonial Africa, and allying the USA with the former colonizer Belgium to back Josef Mobutu. Mobutu became a dictator who enriched himself and his backers, and allowed his country to be utilized by outside imperial interests. (James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed, Second Edition, pp. 372-73) Nixon was Vice President under Eisenhower, and in National Security Council meetings spoke derisively and patronizingly of African leaders trying to break out of colonialism. He once said these leaders had only been out of the trees for fifty years. (Muehlenbeck, p. 6) Kennedy’s attitude on this subject, and Lumumba, was contrary to all these men. I cannot do better than to refer the reader to Richard Mahoney’s landmark book JFK: Ordeal in Africa, and the equally fine volume Betting on the Africans by Philip Muehlenbeck. (Click here for a review)

To show just how pernicious Chomsky’s influence on some Left luminaries is on this subject, consider David Talbot’s last appearance on Democracy Now hosted by Amy Goodman. In discussing his book on Allen Dulles, The Devil’s Chessboard, he mentioned the differing views of Lumumba by Eisenhower and Kennedy. Incredibly, Goodman challenged him on this point. Talbot referred to the aforementioned picture of Kennedy as evidence of JFK’s feelings on the subject. But further, as Mahoney’s book demonstrates, the first foreign policy reversal of Eisenhower that Kennedy made once in office was on the Congo. And when Dag Hammarksjold was killed (likely murdered) in a plane crash, Kennedy decided to carry on the UN Chairman’s campaign for a free and independent Congo. (Click here) That any informed person could suggest otherwise shows both a massive ignorance and a massive bias on the subject. Yet, Goodman has hosted Chomsky many times. She reportedly vetoed an appearance by Jim Douglass.

Chomsky has also tried to say that Kennedy approved the action plan to overthrow President Goulart of Brazil. (E-mail communication with Steve Jones, July 20, 2017) Yet, this plan did not occur until over four months after Kennedy was dead. Consider the information in A. J. Langguth’s Hidden Terrors. Although it is true that Kennedy wanted Goulart to broaden the political spectrum of his government, Langguth makes it clear that the actual Brazil overthrow was similar to the action against Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954. A group of wealthy and powerful businessmen petitioned the White House for help in getting rid of a man they feared would endanger their investments. Langguth describes this group in detail. It was led by David Rockefeller. (p. 104) The author notes that Rockefeller’s coalition had not been accepted at the White House previous to January of 1964. But they were welcomed by President Johnson. And this made the difference. This demarcation is also noted by Kai Bird in his book, The Chairman. For it was John McCloy, the subject of Bird’s book, who was sent by Rockefeller’s group to make a deal with Goulart in February of 1964. When McCloy’s presence in Brazil was detected, it polarized forces of the left and right. (Bird, pp. 550-53) And this triggered the coup operation, codenamed Operation Brother Sam, which McCloy acquiesced in after causing. As Bird notes, Johnson’s willingness to cooperate with Rockefeller and McCloy ended Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress plan: “The Johnson administration had made clear its willingness to use its muscle to support any regime whose anti-communist credentials were in good order.” (ibid, p. 553) Further, anyone who has read Donald Gibson’s Battling Wall Street would understand the antipathy between President Kennedy and Rockefeller and why such a meeting was unlikely under Kennedy.

III

These two examples are good background for even worse gymnastics by Chomsky. And it brings us closer to Vietnam. In June of 1977, Chomsky co-wrote (with Edward Herman) a now infamous article in The Nation. It was titled “Distortions at Fourth Hand.” There is no other way to describe this essay except as an apologia for the staggering crimes of the collectivist Pol Pot regime that took place in Cambodia after the fall of both Prince Sihanouk and Lon Nol. At that time a book had been published called Cambodia Year Zero by François Ponchaud. It was the first serious look at the terrors that Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge had unleashed in Cambodia. Chomsky and Herman criticized this pioneering work by saying that it played “fast and loose with quotes and numbers” and that since it relied largely on refugee reports, it had to be second hand. They then added that the book had an “anti-communist bias and message.” In retrospect, those two comments are startling, and again show a remarkable selectivity in an effort to discredit sources. In this same article, the two authors praised a book by George Hildebrand and Gareth Porter entitled Cambodia: Starvation and Revolution. They wrote that this book presented “a carefully documented study of the destructive American impact on Cambodia and the success of the Cambodian revolutionaries in overcoming it, giving a very favorable picture of their programs and policies, based on a wide range of sources.”

In other words, not only were the authors attempting to discredit information that turned out to be true; at the same time, they were crediting information that turned out to be—to put it mildly—inaccurate. The net effect of this propaganda was to distort and conceal the efforts of a murderous regime in killing off well over one million of its citizens in an attempt to recreate a Maoist society overnight. Pol Pot’s was one of the greatest genocides per capita in modern history.

What makes Chomsky’s performance here even worse is that two years later he and Herman were still discounting and distorting the Khmer Rouge in their book After the Cataclysm. They refer to what Pol Pot did as “allegations of genocide” (p. xi, italics added). On the same page they tried to imply that Western media created the mass executions and deaths. They later added that evidence was faked and reporting was unreliable. (pp. 166-77) They again attacked Ponchaud’s book by saying “Ponchaud’s ’s own conclusions, it is by now clear, cannot be taken very seriously because he is simply too careless and untrustworthy.” (p. 274) Later, more credible and responsible authors, like William Shawcross, demonstrated Chomsky’s pronouncements to be astonishingly wrong. They were so bad that Chomsky has never let up trying to minimize what he did. In fact, his whole emphasis on the Indonesian invasion of East Timor has been to try and demonstrate that that slaughter was really worse than what happened in Cambodia! The implication being that if that were true it would then somehow minimize his previous giant faux pas. And even in that he has lowballed the fatalities in Cambodia to do so. (For a complete and thorough expose of this subject, click here)

Why is this important? Besides demonstrating what a poor scholar and historian Chomsky is, it shows that, contrary to his claim of being an anarchist, he went to near ludicrous extremes to soften the shocking crimes of a Maoist totalitarian regime. In any evaluation of Chomsky, this episode is of prime importance. For the simple reason that it clearly suggests that—as Ted Koppel recently said of Sean Hannity—ideology is more important to him than facts.

A second notable aspect of Chomsky’s work is his association with the notorious Holocaust denier Professor Robert Faurisson. When Faurisson’s writing on this subject became public, he was suspended from his position at the University of Lyon. Chomsky then signed a petition in support of Faurisson’s reinstatement. He followed that up in 1980 with a brief introduction to a book by Faurisson. Chomsky later tried to say that he was personally unacquainted with Faurisson and was only speaking out for academic freedom. But, unfortunately for Chomsky and his acolytes, this was contradicted by Faurisson himself. For the Frenchman had written a letter to the New Statesman in 1979. It began with: “Noam Chomsky … is aware of the research work I do on what I call the ‘gas chambers and genocide hoax’. He informed me that Gitta Sereny had mentioned my name in an article in your journal. He told me I had been referred to ‘in an extraordinarily unfair way’.” (This unpublished letter was quoted in the October, 1981 issue of the Australian journal Quadrant.)

Consequently, Chomsky’s later public qualifications about his reasons for signing the petition and writing the introduction ring hollow. He did know Faurisson. He was in contact with him personally, and apparently was encouraging him to defend his work.

When he found this out, author and professor W. D. Rubinstein had a correspondence with Chomsky, which seemed to certify the worst fears about the noted linguist and Faurisson. Chomsky wrote the following: “Someone might well believe that there were no gas chambers but there was a Holocaust … ” (ibid) In defending Faurisson’s writings Chomsky then wrote that anyone who found them lacking in common sense or accepted the established history, was exhibiting “an interesting reflection of the totalitarian mentality, or more properly in this case, the mentality of the religious fanatic.” (Ibid) Rubinstein replied that to hold that there were no gas chambers but there was a Holocaust was an absurd tenet. Chomsky went ballistic. He wrote back that the respondent was lacking in elementary logical reasoning, and he was falsifying documentary evidence. He then said that the Nazis may have worked these Jews to death and then shoveled their bodies into crematoria without gas chambers. He concluded his blast with this: “If you cannot comprehend this, I suggest that you begin your education again at the kindergarten level.” (Click here for this remarkable article)

As Werner Cohn has shown, Chomsky has tried to conceal his friendly relations with a Holocaust Denial group in France. This group included Serge Thion, Faurisson and Pierre Guillame. He seems to have gotten in contact with this group through Thion, another leftist critic of the idea of calling what Pol Pot did in Cambodia a genocide. This group ran a publishing house called La Vieille Taupe, which featured prints of Holocaust Denial literature. The petition that Chomsky signed contained the following sentence about Faurisson: “Since 1974 he has been conducting extensive independent historical research into the ‘holocaust’ question.” The framing of the last two words in that statement should jar anyone’s senses. (For an overview of Chomsky’s association with this group click here; for a specific example of his attempt to cover it up, click here.)

As with his resistance to the Khmer Rouge genocide, Chomsky’s defense and association with Faurisson is startling to any objective person. Which again excludes his acolytes. Today, the low estimate for the fatalities caused by the crimes of the Khmer Rouge is 1.7 million. (see this NYT article from 2017) The idea that there were no mass gassings and crematoria at the Nazi death camps was thoroughly debunked at the trial of David Irving. Irving was a friend and colleague of Faurisson. That court action was instigated by Irving himself. There has been a very good web site constructed from the materials devoted to that trial. I strongly recommend reading the reports given to the court by Robert Jan van Pelt, Christopher Browning, and Richard Evans. They seem to me to be models of what scholarly research should be about.

IV

Before centering on the issues of Kennedy’s assassination and his presidency, it is important to discuss briefly the general issue of the Cold War, if only to place those subjects in historical context. As with many leftist polemicists, Chomsky usually does not do this. And when he does, he almost exclusively centers on what western powers did to cause the Cold War and continue it.

Yet it would seem to most people to be important to review objectively these matters in any historical discussion of American foreign policy from 1945-1991—the obvious reason being that it was the most powerful influence on American foreign policy and world events in that time period. Every president from Harry Truman to George H.W. Bush was strongly influenced by it, to the point that almost every major foreign policy issue was colored by it. Therefore, if one is writing the history of this period, or a part of it, one has to factor this into the discussion. If not, then one can be accused of ignoring, or discounting, the historical backdrop.

For to deprive these events of their context is to sap them of some of their meaning. Related to this, another problem with Chomsky—as noted above—is imbalance. The policy of aiding foreign countries in their resistance to communism was spelled out way back in 1947 with the Truman Doctrine. This was then endorsed by Congress, and legislation was passed to carry out the policy. One can argue whether or not the Cold War was exaggerated, whether it was too covert, even whether or not it was justified. But one cannot act as if it did not exist. Or that the communist side had no provocations to it, or had no atrocities done in its name. For how else can one explain the Korean War, Hungary in 1956, or the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968? We can continue in this vein with the Chinese usurpation of Tibet or the crimes of Fidel Castro, or those of Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong, the latter of which are both mind-boggling.

But as with Pol Pot in Cambodia, these things are minimized, discounted or ignored by people like Chomsky, and the late Alexander Cockburn. Almost all of the critical analysis was and is of the USA. But if things like balance and historical context are left out, then what is this kind of writing really worth?

Which is another way of saying the following: A theoretical approach is only as good as the person who uses it. If that writer is too biased one way or the other, the result will suffer greatly. To make a point of comparison: Michael Parenti is also an advocate of the aforementioned style of analysis we have called “structural” or “systemic”. Yet he understands that there are men and women who occasionally manage to rise above the system and do some good for a great number of people. And Parenti also understands that political conspiracies do exist, and have been proven to exist. To use just one example, the heist of the 2000 election in Florida by Jeb Bush and Katherine Harris.

Even though this crime was done in broad daylight—what with roadblocks set up to hinder people from voting—no person was even interviewed by any law enforcement arm, let alone indicted. The political result of this was horrendous: George W. Bush created a totally unjustified war in Iraq. A war that Al Gore would not have started. Not only do political conspiracies exist, if not addressed, prosecuted, and stopped, they can have terrible results for hundreds of thousands, even millions, of people. So to deny they occur is to deny reality. And as Parenti has said, reality is sometimes radical.

A second problem with using this system-oriented approach is that—as we have seen with Cambodia—it tends to sweep all contrary facts or evidence into an ideological whirlpool. That is, facts get discounted, data gets warped, and key events are sometimes omitted. What is important is keeping the model of that oppressive structure intact. If facts or data collide with that model, it’s the facts or data that get discarded or discounted. The theoretical underpinnings of Chomsky and Edward Herman’s writings on Cambodia were to show that American and western media was distorting a communist revolution. Therefore, they repeatedly used phrases like “the alleged genocide in Cambodia”, or they wrote that “executions have numbered at most in the thousands”. (See this article) This last comment was written in 1979, when the Khmer Rouge regime had fallen and some reporters had visited the country to actually see the horrible devastation with their own eyes. At times Chomsky and Herman used Khmer Rouge sources and endorsed books that extensively sourced footnotes to Pol Pot’s government releases. This approach is a serious problem for people who actually care about things like accuracy, fairness, and completeness.

In the wake of Oliver Stone’s JFK, what was so odd about the Chomsky/Cockburn allegiance to a point of view which privileges the critique of institutions as systems is that it disappeared upon their inquiry into Kennedy’s murder. That is, in both men’s comments on the Warren Commission and its presentation of evidence, you will nowhere find any discussion of the lives and careers of the persons who controlled that investigative body. Men like Allen Dulles, John McCloy, Gerald Ford, and J. Edgar Hoover. Yet, those four men dominated the Commission proceedings. (See Walt Brown’s book, The Warren Omission, especially pp. 84-87).

This is odd—in two respects. First, it was these men, not Kennedy, who had played large parts in being ‘Present at the Creation’—that is, in forming and then supporting the Eastern Establishment, which was responsible for setting up and maintaining the structure of American government in the 20th century. Any critic of the way institutions of power function would surely be concerned with this detail, because in presenting that particular case, one does not have to juggle, manipulate, and distort the evidence. There are books on these men in which tons of evidence exist to make that demonstration. These four were clearly responsible for some of the worst American crimes of the 20th century. (See James DiEugenio, Reclaiming Parkland, second edition, pp. 234-40, 321-40.)

Secondly, to somehow suppose that those four would not manipulate the evidence in a murder case is simply to ignore the reality of who they were. Yet this is the concept that both Chomsky and Cockburn supported. For instance, as mentioned earlier, Cockburn actually interviewed a junior counsel for the Warren Commission in the pages of The Nation. He never asked him one challenging question. Which is incredible considering the record of that Commission.

Regarding Chomsky, consider an incident from 1994. Two subscribers to Probe Magazine, Steve Jones and Bob Dean, went to a meeting of the Democratic Socialist Club of Reading, Pennsylvania. Chomsky was the guest speaker. Both Jones and Dean were surprised when Chomsky seemed to veer off topic to go into a tirade against President Kennedy. When Jones and Dean tried to approach and talk to Chomsky about Kennedy afterwards, he became “very defensive and dismissive of us, brushing us off by saying that he’d seen all of the evidence.” Apparently, this meant the declassified record, and therefore there was nothing to address. (e-mail communication with Jones, 6/19/2017)

Again, this tells us much about Chomsky’s respect—or lack of—for scholarly practice. Because, at that time, the Assassination Records Review Board had just begun declassifying two million pages of records that had previously been kept secret from the public on the JFK case. Hence no one had seen them prior to this time. Including Chomsky. So what was he talking about? The evidence the ARRB declassified concerning the actual circumstances of Kennedy’s murder make the case against Oswald pretty much insupportable. And in just about every way: concerning Oswald, Kennedy’s autopsy, the ballistics evidence, and Oswald’s alibi. (For the last, see Barry Ernest’s book, The Girl on the Stairs.)

Further, neither Cockburn nor Chomsky seemed to be aware of the transcript of the final executive session of the Warren Commission. Sen. Richard Russell, Representative Hale Boggs, and Senator John Sherman Cooper—who I have previously called the Southern Wing—had planned on expressing their reservations at this meeting about the Single Bullet Theory. The idea that one bullet, CE 399, had gone through both Kennedy and Governor John Connally, smashing two bones, making seven wounds, emerging almost entirely unscathed, and losing almost no volume from its mass. Russell, especially, wanted his objections expressed in the record of this final meeting. Today, we have the record of that meeting. There is no trace of his, or anyone else’s, reservations about the Single Bullet Theory. For the simple reason that there was no stenographic record of that final meeting. (Gerald McKnight, Breach of Trust, p. 284) In other words, the Eastern Establishment figures—Dulles, McCloy, and Ford, likely coopted Chief Justice Earl Warren and chief counsel J. Lee Rankin into tricking the other members into believing there would be such a record. In fact, a woman was there masquerading as a stenographer. But the Commission’s contract with the stenographic company had expired three days prior. (ibid, p. 295) As Gerald McKnight writes about this matter, the obvious reason for this charade was to keep the strenuous objections of the Southern Wing out of the transcribed record, and thereby maintain the illusion that the Commission had been unanimous in its verdict on the case. In other words, here was an almost textbook case of the way institutions tend to ensure the survival of belief in the status quo, one made to order for critics on the Left.

But in an unexplained inconsistency, both Chomsky and Cockburn dropped the structural approach in their analysis of the Commission. Even though it would seem to be perfectly suited for that type of analysis. Why? Because if one did explain who these men were and what they did with the evidence, then one could conclude that they covered up the true circumstances of Kennedy’s death, for the simple reason he was not a member of their club. Which is a direction they do not want to go in.

Yet, David Talbot demonstrates this at length in his analysis of the conflicts between President Kennedy and Allen Dulles during 1961. These were centered on Kennedy’s Congo policy, Dulles’ backing of the revolt of the Algerian generals against French President Charles DeGaulle, and ultimately how Dulles lied to Kennedy about the Bay of Pigs operation. (Talbot, pp. 382-417) In other words, in just one year, the CIA Director had come into conflict with Kennedy over three important areas and events. Finally, Kennedy felt he had to terminate Dulles, along with both his Deputy Director Charles Cabell, and Director of Plans Richard Bissell. The first and only time in 70 years that has been done at the CIA. As Talbot also points out, after Kennedy was killed, Dulles lobbied for a position on the Warren Commission (ibid, pp. 573-74)—something that no one else did. As previously referred to, Walt Brown has shown that Dulles then became the single most active member of the Warren Commission. During a meeting with Commission critic David Lifton at UCLA in 1965, Dulles showed utter disdain for any of the evidence that the Commission had ignored or misrepresented to the public, e.g., the Zapruder film frames. (Talbot, p. 591)

Let us use just one other example. Robert Kennedy was the first Attorney General who actually exercised some degree of control over FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. The enmity between the two has been well chronicled by more than one author. After JFK was killed, Hoover had Bobby Kennedy’s private line to his office removed. (Anthony Summers, Official and Confidential, p. 315) The Warren Report itself says that Hoover and the FBI were responsible for the vast majority of the investigation. (See, p. xii) Therefore, why would such men—Dulles and Hoover—who clearly had no love for JFK, bend over backwards to find out the truth about his death? The fact is they did not. For example, the day after the murder, Hoover was so concerned about who killed President Kennedy that he was at the racetrack. (Summers, op. cit.) To leave out things like this, and much more, is not writing history. And it is not honest scholarship. It is depriving the reader of important information.

V

Chomsky operates his views of both Kennedy and his murder via inductive, closed-system reasoning. It is both banal and simplistic: since the USA operates in a sick political and economic system, no one can rise above it. Therefore, Kennedy was really no different than Nixon, Johnson, and Eisenhower. The underlying problem—as writers like Donald Gibson and Richard Mahoney have demonstrated—is that when one actually studies the record, Kennedy was not part of the Power Elite, and did not aspire to be part of it. This is why, as Donald Gibson has shown, Kennedy and David Rockefeller—the acknowledged leader of the Eastern Establishment at the time—had no time or sympathy for each other. (See Gibson’s Battling Wall Street throughout, but especially pp. 73-76) The reason Kennedy made his historic 1957 Senate speech on the impending doom of French colonialism in Algeria was because he had been in Vietnam when the French empire there was collapsing. He understood that the Vietnam conflict had not really been about communism, but about nationalism. And he said this many times, and took considerable heat for it. (See Mahoney, JFK: Ordeal In Africa, pp. 14-23)

When Oliver Stone’s JFK came out, Chomsky made numerous statements questioning Stone’s thesis about Kennedy’s intent to withdraw from Vietnam. He eventually wrote an essay in Z Magazine on the topic. In essence, he denied all the withdrawal evidence as outlined by Fletcher Prouty and John Newman, who advised Stone on that subject. The problem for Chomsky today is that other scholars decided that Prouty and Newman were on to something. After all, Prouty actually worked on Kennedy’s withdrawal plan in September of 1963. John Newman was writing a revolutionary book on the subject entitled JFK and Vietnam, which was published in January of 1992.

Seriously considering that evidence, these scholars then went to work. And today, a small shelf of books exists on the subject. These authors agree with the Stone/Prouty/Newman withdrawal thesis, e.g., David Kaiser’s American Tragedy, James Blight’s Virtual JFK, Gordon Goldstein’s Lessons in Disaster. One reason these new books are there is that the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB) declassified many pages of documents that support the withdrawal thesis. This declassification process occurred in 1997. Any serious scholar has to consider new evidence when it is declassified. Chomsky did not. In 2000, in a book called Hopes and Prospects, in relation to this issue, he wrote: “On these matters see my Rethinking Camelot … . Much more material has appeared since, but while adding some interesting nuances, it leaves the basic picture intact.” (pp. 123, 295)

In other words, the scores of pages of new ARRB documents released on the subject, the recorded tapes in the White House, and the new essays and books published, these amount to “nuances.” The “nuances” include President Johnson confessing in February of 1964 that he himself knows he is breaking with Kennedy’s policy. They include the transcripts of the May 1963 Sec/Def meeting in Hawaii where McNamara is actually executing that withdrawal plan—with no reference to a contingency upon victory. (These and other documents are included in this presentation)

In 1997, that last piece of evidence convinced some MSM outlets, like The New York Times, that Kennedy was planning on withdrawing from Vietnam at the time of his assassination. We can go on and on. But the point is made. To any objective person, these are not “nuances”. They are integral.

To show Chomsky’s bizarreness on this point, let us use two other instances of just how intent he is to disguise the facts and evidence of Kennedy’s withdrawal plan. One of his older excuses was to say that Kennedy’s advisors fabricated the withdrawal plan after the Tet offensive. (Z Magazine, September, 1992) Even for Chomsky, this is ridiculous. What is he saying? That Kennedy’s advisors falsified the then classified record while it was in the National Archives? That they also managed to get a voice impressionist to impersonate Johnson, McGeorge Bundy and McNamara discussing this withdrawal plan?

Chomsky’s latest position is a sort of rear action retreat. He now admits that Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara offered up a withdrawal plan. In other words, it was McNamara’s plan, not Kennedy’s. Not so, and let us illustrate why.

In November of 1961, a two-week long debate took place in the White House. The subject was whether or not to commit combat troops into Vietnam. Advisors Max Taylor and Walt Rostow had returned from Vietnam and made that recommendation. From all the accounts we have, Kennedy was virtually the only person arguing against that proposal. (James Blight, Virtual JFK, pp. 275-83) At its conclusion he signed off on NSAM 111 which sent 15,000 more advisors instead.

Kennedy was disturbed that he had to carry the argument virtually alone. So he decided to ask someone who he knew agreed with him to write his own report on the subject. This was Ambassador to India, John Kenneth Galbraith. Galbraith did visit Saigon, and he did write a report recommending no combat troops in theater and a gradual American distancing. (Cable of November 20, 1961, which was followed by a longer report; Blight, p. 72, see also David Kaiser, American Tragedy, pp. 131-32) Kennedy later had this report forwarded to Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara in April of 1962. This was the beginning of the withdrawal plan. We know this because on his trip to Vietnam in May, McNamara told General Paul Harkins to begin a training program for the army of South Vietnam so America could begin reducing its forces there. Harkins was the supreme military commander in Saigon. (Kaiser, pp. 132-34) Also, McNamara’s deputy Roswell Gilpatric revealed in an oral history that his boss had told him that he had instructions from Kennedy to begin to wind down the war. (Blight, p. 371) This culminated with the aforementioned declassified Sec/Def conference in Hawaii in May of 1963. At this meeting, McNamara requested from all departments—State, Pentagon, CIA—specific schedules beginning a withdrawal in December of 1963 and ending in the early fall of 1965. (James Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable, p. 126)

The idea that this plan was McNamara’s is another fanciful Chomsky invention. In addition to the evidence stated above—cables, oral history—there is another undeniable fact. In the November, 1961 debates described above, McNamara was asking for the insertion of combat troops into Vietnam. In fact, his proposal was the largest request of all. He told Kennedy to commit upward of six divisions, or about 205,000 men. And he framed the request in pure Cold War terms. If this was not done, it would lead to communist control over all of Indochina and also Indonesia. (Blight, pp. 276-77) The idea that afterwards McNamara had a personal epiphany and reversed himself on his own is simply not credible. Especially when combined with the above evidence. Plus the fact that it was Kennedy alone who was holding out against combat troops in November. And as with Kennedy, there is no mention by McNamara on any tape or any of the Sec/Def documents, or in NSAM 263, that the withdrawal plan would only be completed as the circumstances on the battlefield improve. Chomsky’s arguments against Kennedy’s withdrawal plan exist in a vacuum created by him and his acolytes.

VI

In Barbour’s film, Chomsky is shown at a seminar saying words to the effect that no one should care if Kennedy died as a result of a conspiracy. The problem with this statement is that, at the time of Kennedy’s death, it’s the people who Chomsky tries to stand up for—residents of the Third World—that felt a sharp pang of loss at JFK’s passing. And very few of them felt that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone assassin. The president of Egypt, Gamel Abdul Nasser, fell into a deep depression and had the films of Kennedy’s funeral shown four times on national television. (Philip Muehlenbeck, Betting on the Africans, p. 228) Ben Bella, the premier of Algeria, phoned the American ambassador in Algiers and said, “I can’t believe it. Believe me, I’d rather it happen to me than him.” He then called in a comment to the state radio station saying that Kennedy had been a victim of “racialist and police-organized machinations”. (ibid, p. 227) When asked about Kennedy’s assassination in 1964, Achmed Sukarno of Indonesia began perspiring. He then said that he loved the man because Kennedy understood him. He ended the reverie by saying, “Tell me, why did they kill Kennedy?” (James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed, Second Edition, p. 374) Nehru of India called Kennedy’s murder a crime against humanity. He then said that Kennedy was “a man of ideals, vision, and courage, who sought to serve his own people as well as the larger causes of the world.” (Muehlenbeck, p. 231) Two weeks after Kennedy’s death, economist Barbara Ward visited the office of Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. The president had a photo of John and Jackie Kennedy on his desk. With tears in his eyes he said, “I have written her, and I have prayed for them both. Nothing shocked me so deeply as this.” Months later, when the American ambassador presented him with a copy of the Warren Report, Nkrumah turned to the title page. He pointed to the name of Allen Dulles, and returned it to the ambassador with the one word comment, “Whitewash”. (Muehlenbeck, p. 229; Richard Mahoney, JFK: Ordeal in Africa, p. 235)

But it wasn’t just the leaders of the Third World who were shaken and saddened by Kennedy’s passing. It was also its citizenry. As an editorial in West Africa magazine stated, “Not even the death of Dag Hammarskjold dismayed Africans as much as did the death of John Kennedy.” (Muehlenbeck, p. 229) In Nairobi, Kenya, six thousand people packed into a cathedral for a memorial service. A Kenyan politician said that never in his career had he seen this kind of grief registered over the death of a foreigner. (Muehlenbeck, p. 226) In the Ivory Coast, the American ambassador woke early the day after the assassination. There was someone waiting for him at his office. The man said he ran a small business about 25 miles away. He said he didn’t really know why he was there. But he tried to explain anyway: “I came here this morning simply to say that I never knew President Kennedy, I never saw President Kennedy, but he was my friend.” (Ibid, p. 228) According to author Thurston Clarke, upon learning of his passing, the peasants of the Yucatan Peninsula immediately started planting a Kennedy Memorial Garden.

Were all these people wrong?

But there is one person we can add to this list. His name is Noam Chomsky.

In the time period following Kennedy’s murder, writer/researcher Ray Marcus tried to enlist several prominent academics to take up the cause of exposing the plot that killed President Kennedy. In 1966 he wrote I. F. Stone on the subject. In 1967, he approached Arthur Schlesinger about it. They both declined to take up the cause. In 1969, he was in the Boston area on an extended business function. He therefore arranged a discussion with Chomsky. Chomsky had initially agreed to a one-hour meeting in his office. Ray brought only 3-4 pieces of evidence, including his work on CE 399, the Magic Bullet, and a series of stills from the Zapruder film. Which had not been shown nationally yet.

Soon after the discussion began, Chomsky told “his secretary to cancel the remaining appointments for the day. The scheduled one-hour meeting stretched to 3-4 hours. Chomsky showed great interest in the material. We mutually agreed to a follow-up session later in the week. Then I met with Gar Alperovitz. At the end of our one-hour meeting, he said he would take an active part in the effort if Chomsky would lead it.” (Probe, Vol. 4 No. 2, p. 25) Ray did have a second meeting with Chomsky which lasted much of the afternoon. And “the discussion ranged beyond evidentiary items to other aspects of the case. I told Chomsky of Alperovitz’ offer to assist him if he decided to lead an effort to reopen. Chomsky indicated he was very interested, but would not decide before giving the matter much careful consideration.” (ibid) A professional colleague of Chomsky’s, Professor Selwyn Bromberger, was also at the second meeting. He drove Ray home. As he dropped him off he said, “If they are strong enough to kill the president, and strong enough to cover it up, then they are too strong to confront directly … if they feel sufficiently threatened, they may move to open totalitarian rule.” (ibid)

It is important to reflect on Bromberger’s words as Ray related what happened next. He returned to California and again asked Chomsky to take up the cause. In April of 1969, Chomsky wrote back saying he now had to delay his decision until after a trip to England in June. He said he would get in touch with Ray then. Needless to say, he never did. He ended up being a prominent critic of the Vietnam War and this ended up making his name in both leftist and intellectual circles. Reflecting on Bromberger’s words to Marcus, one could conclude that Bromberger and Chomsky decided that the protest against Vietnam, which was becoming both vocal and widespread, and almost mainstream at the time, afforded a path of less resistance than the JFK case did. After all, look at what had happened to Jim Garrison.

But if this is correct, it would qualify as a politically motivated decision. One not made on the evidence. As Marcus writes, it was with Chomsky, “not the question of whether or not there was a conspiracy—that he had given every indication of having already decided in the affirmative … ” Marcus’ revelations on this subject are informative and relevant in evaluating Chomsky, both then and now. For purposes of our argument, it is important to know what Chomsky actually thought of the evidence when he was first exposed to it. This would seem to be a much more candid and open response than what he wrote decades later, when his writings on the subject were just as categorical, except the other way. In other words, Chomsky did a 180-degree flip on the issue of whether President Kennedy was killed by a conspiracy. And that first conviction lasted at least until 1976. Because in that year, he signed a petition to form the House Select Committee on Assassinations. That is very likely the reason that, in 1971, as co-editor of the Senator Mike Gravel edition of the Pentagon Papers, he allowed Peter Scott to write an essay addressing the question of Johnson’s alteration of Kennedy’s de-escalation plan in Vietnam.

Try and find an interview or essay in which Chomsky admits how close he was to being the chief advocate for a public campaign to find out who really killed Kennedy. Yet, it is a fact. Maybe Chomsky changed his mind. But if that was the case, he has no right to be so smug and snide about others who came to the same conclusion he once did. Or perhaps, as Bromberger let out, he and Alperovitz and Chomsky decided that Vietnam offered an easier path to prominence. Which, undoubtedly, it did. If that was the case, then it was a practical choice, not an intellectual or moral one. And evidently, Chomsky and his friends did not realize that they could have combined the two.

As we have seen, Chomsky’s recurrent posing as a scholar who has assimilated the entire declassified record on the JFK case, and on the Kennedy/Johnson Vietnam policies, is simply an empty pose. And this is part of a persona that, as we have seen in the case of Faurisson and Cambodia, substitutes an extreme and ingrained bias for what is supposed to be scholarly analysis. If there is any hope of reconstituting this nation around a viable set of values and principles, then the issue of the hijacking of America in the sixties through assassinations will have to be honestly confronted. As we have seen, Noam Chomsky refuses to do that—in fact he deliberately avoids it. He then adopts certain disguises and deceptions to conceal the way he once felt about the subject. Which is, in large part, why he is part of the problem, not the solution.