Copyright August 2000 (Probe, Vol 7 No 6, September-October 2000) (original .pdf)

“Scary” is the word attorney Dr. William Pepper uses to describe the Justice Department’s official report about the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Issued in June 2000 by US Attorney Barry Kowalski, the King Report [1], which was initiated in 1998 at the request of the King family and Dr. Pepper, completely absolves the federal government of any involvement in a conspiracy to kill the Noble Prize-winning Civil Rights leader and anti-war activist. According to the King Report, James Earl Ray was the lone assassin – and anyone who says otherwise is crazy, a liar, or just out for the money.

This is a scary message, especially if you are an outspoken witness with a different point of view, a member of the King family, or a skeptic conducting research into the King assassination.

“I mean “scary” in a very serious way,” Pepper emphasizes. “The extent to which they papered-over and denied the facts is seriously scary.”

Pepper – who is compiling a list of fifty relevant facts that Kowalski deliberately overlooked in his attempt to rewrite history – should know. For years he has represented the King family in its flawed quest to discover the federal government’s actual role in Dr. King’s assassination. Pepper also is the object of much of the King Report’s artless innuendo, for while Kowalski’s stated purpose is to determine the truth, his true intention is to frighten anyone and everyone, but especially Pepper and the King family, from ever again disputing the official story.

Read the King Report from cover to cover and the message it sends is perfectly clear: no matter what the truth is, if you even suggests that the government was part of a conspiracy to kill Dr. King, the government has the power to twist what you say and destroy your reputation – and there’s not a damn thing you can do about it.

What’s It All About, Kowalski?

In making its intimidating point, the King Report focuses on four general subjects:

- the allegations of Loyd Jowers, a Memphis businessman who claimed to be one of the people who planned King’s assassination;

- the allegations of Donald Wilson, a former FBI agent who claims that in 1968 he discovered papers that contained references to Raoul in James Earl Ray’s car. (Sometimes referred to as Raul, Raoul was the mystery man whom Ray, over a period of thirty years, steadfastly maintained had managed his movements and ultimately framed him in the assassination);

- Raoul and his role in the assassination, if any; and

- the evidence and witnesses that prompted a Memphis jury to conclude, in December 1999, that the federal government was somehow involved in the assassination.

Kowalski tackles the first two subjects first, and in two separate sections of the King Report he systematically destroys the allegations, and reputations, of Jowers (whose numerous contradictory statements are recounted in dissembled detail) and Wilson (who is portrayed as unstable and unreliable). The primary, unscrupulous tactic Kowalski uses in achieving this result is the sweeping distortion and selective presentation of evidence and facts.

For example, on Page 3 of Part 2 of the King Report, Kowalski makes two assertions. The first is the straightforward statement that Jowers “refused to cooperate with our investigation.” This is a charge that will be repeated over and over again when Kowalski seeks to defame a particular individual. In this case, Kowalski is asserting that Jowers refused to accept an offer of immunity.

The second assertion is a vague generalization that relies heavily on innuendo. Kowalski states that, “In 1993, Jowers and a small circle of friends, [2] all represented by the same attorney, sought to gain legitimacy for the conspiracy allegations by presenting them first to the state prosecutor, then to the media. Other of Jowers’ friends and acquaintances, some of whom had close contact with each other and sought financial compensation, joined the promotional effort over the next several years. For example, one cab driver contacted Jowers’ attorney in 1998 and offered to be of assistance. Thereafter, he heard Jowers’ conspiracy allegations, then repeated them for television and during King v Jowers. Telephone records demonstrate that, over a period of several months, the cab driver made over 75 telephone calls to Jowers’ attorney and another 75 calls to another cab driver friend of Jowers who has sought compensation for information supporting Jowers’ claims.”

The transparent implication of this second assertion is that Jowers’ unnamed attorney concocted a scam to package and sell the contrived conspiracy theory of a small group of hustlers. As proof of this “conspiracy,” Kowalski cites 75 phone calls from an unnamed cab driver to the attorney. We are supposed to believe that all of this is true, because Kowalski is a decent chap who does not name the conniving attorney.

But was Kowalski really trying to protect the reputation of the attorney, while issuing this backhanded slap in the face? The attorney, Lewis Garrison, does not think so. Garrison believes that Kowalski is playing with words and toying with the truth, and he adamantly disputes both of Kowalski’s assertions.

Regarding the first assertion, that Jowers refused to cooperate with Kowalski’s investigation:

“Please be assured,” Garrison stresses, “that Kowalski never, repeat never offered immunity to Mr. Jowers. When Kowalski first contacted me, he indicated that he could obtain immunity from the United States Government, but was advised that the US Government could not provide immunity because the Statute of Limitations prevented it. Kowalski then indicated that he could obtain an agreement for immunity from the local District Attorney. But that was never done. Kowalski may have gotten an agreement for immunity from the State of Tennessee, as he asserts in his Report, but he never communicated that fact to me.”

Barely three pages into Part Two of the King Report, and already Kowalski stands accused of lying about Jowers’ refusal to cooperate, and of dissembling information about the immunity agreement Jowers was allegedly offered by the State of Tennessee.

Garrison notes that within two days of Kowalski’s promise to obtain immunity from the State of Tennessee, the local District Attorney, John Pierrotti (who was later forced to resign his post for misappropriating funds), made an announcement through the local newspaper that he did not believe Jowers, and would never grant immunity to him.

Once the DA had made public his intentions not to grant immunity to Jowers, why would Garrison believe that Kowalski could obtain it? And knowing that Kowalski was dangling a false promise, why on earth would Garrison want to cooperate with him?

Kowalski also distorted the facts when he stated that Jowers would have been immune from prosecution if, in lieu of a proffer, he had submitted a videotape of his October 1997 meeting with Dexter King, son of the slain Dr. King. Kowalski cites Jowers’ refusal to submit the videotape as proof that he was being untruthful. But, as Bill Pepper is careful to point out, Kowalski was only offering “use” immunity in regard to statements Jowers made on the videotape; Kowalski could not promise that the State of Tennessee would not prosecute Jowers in regard to anything else he said.

According to Garrison, “Kowalski was advised that if he could obtain a grant of immunity from Tennessee, Mr. Jowers would meet with him and answer every question he wanted to ask. We offered videotapes and transcripts of interviews with Jowers and Ray in exchange for immunity. But Kowalski never wanted to interview Jowers. His intention was to attack his credibility along with that of former FBI agent, Wilson.”

Kowalski’s second assertion – that Garrison was the mastermind of a conspiracy of petty crooks – is proof that his unstated intention was to falsely destroy the credibility of everyone associated with Jowers and Garrison. Kowalski himself raises the best example of this dubious tactic when he refers to James Milner, the cab driver who ostensibly made 75 phone calls to Garrison. Kowalski’s implication is that Milner made those 75 calls directly to Garrison, but that implication is not a fact.

“Milner, who knew nothing at all about the assassination, may have called my office 75 times,” Garrison sighs in dismay, “but we never talked 75 times. Five times maybe, but not 75.”

When asked why a US Attorney would stoop so low as to misrepresent the actions of a non-entity, and then elevate those distorted actions to monumental proportions, Garrison suggests that Kowalski had professional help. “There is very little difference between the Report Kowalski submitted and the book written by Gerald Posner,” he says. Garrison adds that Posner, whom he describes as “deceptive,” misquoted him in his FDA-approved, conspiracy-debunking book, Killing The Dream.

Curiously, Kowalski credits Posner as a major contributor to the King Report. But apart from informing every aspect of the King Report with his methodology, which is to ignore any evidence that contradicts his premise, Posner’s qualifications and motives are suspect. Posner’s only interest in the King assassination is pecuniary. He never spoke to James Earl Ray, Loyd Jowers, or any members of the King family, and he never attended the King versus Jowers trial.

But for that matter, Kowalski was never at the trial either.

“Kowalski is deceptive too,” Garrison concludes. “He was fully aware that the judgment from the Circuit Court in Shelby County was against Jowers, the City of Memphis, the State of Tennessee, and the United States Government. He knew this before the King versus Jowers trial. He knew the US Government had been named as a defendant, but he never took any action to defend it.

“On the other hand, although we were advised that his Report was completed several months ago, it is interesting that Kowalski waited until the death of Mr. Jowers (on 20 May 2000) before releasing it.”

The Motive In His Madness

Nowhere is Kowalski’s adopted methodology of distortion and selective presentation of facts and evidence more evident than in his cursory investigation of Raoul. To the exclusion of all other evidence, Kowalski focuses solely on the theory that Raoul is a Portuguese man living in New York City. Granted, he makes an airtight case that this particular Raoul was not involved in the assassination. But he never searched for any other Raouls, and he disingenuously assumed that because the New York City Raoul had an alibi, Raoul was a figment of James Earl Ray’s criminal imagination.

Some of us are not convinced. However, time and space do not permit an in-depth examination of this aspect of the King Report, or of the section dealing with Donald Wilson, who is composing his own rebuttal. Instead, this article will focus on the weakest part of the King Report: Kowalski’s assertions that there is no evidence of the federal government’s involvement in the King assassination, and that a jury in Memphis was wrong in concluding that there was.

It is important to understand that Kowalski makes his case more through style than substance, by disparaging, discrediting, or simply ignoring anyone or any evidence that in any way casts doubt on the official story that James Earl Ray was the lone assassin of Dr. King. The rampaging US Attorney takes no prisoners in effecting this scorched-earth policy. But while he succeeds, superficially, in discrediting Jowers, Wilson, and notions of Raoul, his argument fails when it attempts to dismiss the evidence and witnesses that convinced the Memphis jury that the federal government was involved in a complex conspiracy to kill Dr. King.

The basic flaw in Kowalski’s argument is his failure to address the overwhelming question: Was institutionalized, government-sanctioned racism one of the reasons Dr. King was assassinated?

You bet it was; and institutionalized, government-sanctioned racism, as represented by the King Report, is one of the main reasons why the federal government will never acknowledge its role in the conspiracy to kill Dr. King.

In order to understand the subtext of the insidious King Report, which is so laden with racial bias that one feels contaminated simply by touching it, one must understand the racial situation as its existed and exists in Memphis, Tennessee, where, according to Lewis Garrison, 80% the people prosecuted by the current DA are black, while 80% of the DA’s staff are white.

Unfortunately for Garrison, the people he often represented, and the people who often were the most convincing witnesses at the King versus Jowers trial, are poor and black. And unfortunately for the King family and the American public, the fact that Garrison was surrounded by poor blacks provided Kowalski with the pretext for a strategy of character assassination, as the basis of a continuing cover-up.

Betty Spates, for example, was a young black woman working as a waitress for Loyd Jowers at his tavern, Jim’s Grill, on 4 April 1968. Jim’s Grill was located on the ground floor of the rooming house from which James Earl Ray allegedly shot Dr. King. Spates in April 1968 was having an affair with Jowers, and in a March 1994 affidavit (taken by William Pepper) she claimed to have seen Jowers pass through the grill with the murder weapon in his hands, moments after King was killed. She is the only person to corroborate this aspect of Jowers’ story, but she is summarily dismissed by Kowalski as “not credible.”

Referred to as “the alleged corroborating witness,” Spates is “not credible” because, Kowalski argues, she stayed in touch with Jowers, was represented by Garrison, and “refused to cooperate” with his investigation. She also is named by Kowalski as one of the money-hungry hustlers in Garrison’s conspiracy of petty crooks. But Spates’ biggest sin is having contradicted herself in a January 1994 statement to the local District Attorney. In that statement she said she was not at the grill at the time King was killed, and that she did not see Jowers with a rifle. Since then she has become “confused” and cannot reconcile her contradictory statements.

Kowalski offers no reason why Betty Spates contradicted herself, or why she became confused, but he does grudgingly acknowledge that on 3 February 1969, she told two bail bondsmen that her “boss man” (Jowers) had killed Dr. King. This February 1969 statement came within a year of the King assassination and should have represented a major breakthrough in the case. It was made long before her association with Garrison as well, and no one offered her money to make it. But, as Kowalski is careful to note, when confronted by police about her allegation, Spates retracted her statement nine days later.

Kowalski says, “Spates’ conduct in 1994 duplicates what she appears to have done in 1969. At both times she made a critical allegation about the assassination but, when confronted by law enforcement officials, denied ever making the allegation and refuted it truth.”[3]

Kowalski chooses to interpret this recurring phenomenon as proof of Spates’ unreliability. But people who actually know her have another interpretation, one that offers a more comprehensive explanation as to why, ever since 4 April 1968, certain witnesses have been hesitant to come forward, why these witnesses have contradicted themselves when confronted by local, state, and federal law enforcement officials, and why crucial evidence has mysteriously vanished or been overlooked.

Racism and Plausibility

Coby Smith was a black revolutionary in Memphis at the time of the assassination of Dr. King. A founder and leader of the Memphis-based Invaders (patterned on the more famous Black Panthers and Blackstone Rangers), Smith says that Betty Spates was “compromised because she was having fun.” In other words, Spates used drugs and engaged in prostitution, and thus the Memphis police held a very heavy hammer over her head. An unwed mother with a bad reputation, she is a typical victim of a racially biased judicial system that sometimes seems to have been established by our Founding Fathers specifically to provide the ruling white class with the on-going pretext it needs to avoid prosecution for its crimes against poor blacks.

The King Report exemplifies this exercise in cognitive dissonance. Kowalski’s main consultant, Gerald Posner, has made a tens of thousands of dollars by exploiting the King assassination story, but his lily-white motives are never questioned. Spates and her cabal of poor black co-conspirators, on the other hand, are considered unreliable because, according to Kowalski, they sought compensation for their telling their stories.

Kowalski applies this same double standard to Olivia Catling, and for the same reasons. At the King versus Jowers trial, Catling testified that on the evening of 4 April 1968, she heard a gunshot that came from the vicinity of the Lorraine Motel. Located at 450 Mulberry Street, the Lorraine is less than one hundred yards from Catling’s house on the corner of Mulberry and Huling Streets. Upon hearing the shot, Catling ran outside with her two children and saw “a man in a checkered shirt come running out of the alley beside a building across from the Lorraine. The man jumped into a green l965 Chevrolet just as a police car drove up behind him.” The man sped around the corner up Mulberry past her house, but the police ignored the man and blocked off the street, leaving his car free to go the opposite way.[4]

Eyewitness Catling testified that the man she saw was not James Earl Ray. She also testified that she could see a fireman standing across from the motel when the police drove up. She heard the fireman say to the police, “The shot came from that clump of bushes,” indicating a brushy area behind Jim’s Grill, opposite the Lorraine and near the neighborhood fire station.[5]

“The police,” Catling told reporter Jim Douglas, “asked not one neighbor [around the Lorraine], ‘What did you see?’ Thirty-one years went by. Nobody came and asked one question. I often thought about that. I even had nightmares over that, because they never said anything. How did they let him get away?”[6]

If one is poor and black and living in Memphis, it takes courage to accuse the local authorities of complicity in the King assassination. But this reality never factors into Kowalski’s equation. It doesn’t matter that no one is offering Olivia Catling movie deals or money for her story; it is solely because she is black and poor that he dismisses her as “inconsistent, and contradicted by several key witnesses.”

Would it surprise you to learn that the “key witnesses” who contradicted Catling are Memphis policemen? Kowalski asked the cops if Catling’s allegations were true, and they said “No.” They would have remembered if someone had run their blockade, or if the firemen had called to them.[7]

Kowalski also cites the fact that Catling waited twenty-five years before stepping forward with her story, and he uses that to imply that she is just another hustler out to make a fast buck.

Former Invader Coby Smith has a more plausible explanation. Smith says that Catling, like so many of her ilk, was unwilling to come forward until 1993 because she was afraid of the police.

One begins to see a pattern developing here, a pattern that indicates either a conspiracy by poor black hustlers under the guidance of a greedy lawyer, as Kowalski contends, or a pattern of obstruction of justice by law enforcement officials, as this writer contends. One makes ones choice depending on ones prejudices. But in making your choice, consider this: just as Olivia Catling did not step forward for twenty-five years, it is equally true that no one from law enforcement sought her testimony on 4 April 1968, when it would have had real significance. Indeed, many leads in the King assassination could have been developed through a house-to-house search and interviews of the many eyewitnesses in the predominantly black neighborhood. But none of that was done. The responsibility for doing those things belonged to law enforcement officials, but according to Kowalski’s skewed way of thinking, people like Betty Spates and Olivia Catling are to blame for not coming forward.

While understanding of white policemen, and willing to give them the benefit of the doubt in every instance, Kowalski invariably derides and stigmatizes lower class blacks, thus personifying the sort of insidious racism that replaced legal segregation and now permeates American society, and which defines and undermines the King Report.

Fear and Loathing in Memphis

One of the biggest threats to the government (in its local, state, and federal manifestations) in its efforts to cover-up its involvement in the King assassination, was and is the possibility that black revolutionaries with insights into the King assassination might step forward.[8] In particular, members of the Invaders had to be intimidated, and so the authorities designed a different method of silencing them.

Enter the FBI and its infamous COINTELPRO Program, which was created to neutralize black power groups through extra-legal methods, including infiltrators, agent provocateurs, planting of false evidence and rumors, and by any other means necessary. Dr. King himself was a primary target of the COINTELPRO Program and at one point, on orders of J. Edna Hoover, FBI agents wrote a letter to King suggesting that he kill himself. “There is only one way out for you,” the message read. “You better take it before your filthy, abnormal, fraudulent self is bared to the nation.”

The historical record is clear that the FBI and the military aggressively investigated King as an enemy of the state. His movements were monitored; his phones were tapped; his rooms were bugged; derogatory information about his personal life was leaked to discredit him; and he was blackmailed about his extramarital affairs. Thus it is hard to believe that the FBI was not involved in his assassination.

But Kowalski does not discuss the malice aforethought represented by Hoover’s COINTELPRO Program, nor does he mention that the COINTELPRO Program was directed against the Invaders, whom Hoover called “one of the most violent black nationalist extremist groups”.[9]

Nowhere in the King Report does one learn that in July 1967, at the direction of the FBI (and with the assistance of the CIA), the Memphis Police Department (MPD) formed a four-man Domestic Intelligence Unit (DIU) specifically to infiltrate and undermine the Invaders. Nor does Kowalski explain, in this regard, the significance of the January 1968 appointment of Frank Holloman, a 25-year veterans of the FBI, as Chief of Public Safety in Memphis. As Chief of Public Safety, Holloman managed the city’s police and fire departments. Holloman served much of his FBI career in the South, including a tour in Memphis and seven years as inspector in charge of J. Edna Hoover’s Washington office. It also is important to know that the DIU, under Lieutenant Eli Arkin, was Holloman’s top priority.

Assisting the FBI and the MPD DIU was a special detachment of the 111th Military Intelligence Group (MIG), headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia. Commanded by Major Jimmie Locke, this twenty-member special detachment was assigned to Memphis on 28 March 1968 as part of a Civil Disorder Operation code-named Lantern Strike (under USAINTC OPLAN 100-68). LanternStrike was a training exercise designed to facilitate the working relationship between the 111th MIG, the MPD, the Tennessee National Guard, and the FBI, in their common effort to monitor and, if possible, disrupt any civil disorder that might arise in Memphis as a result of a Sanitation Workers strike..

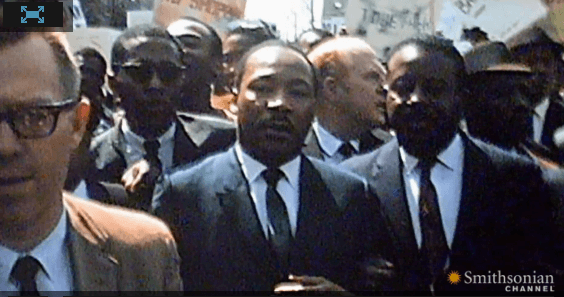

And civil disorder there was. Dr. King arrived in Memphis on 28 March to lead a march organized by the predominantly black Sanitation Workers, who had been on strike for several weeks. The march began at eleven o’clock and within minutes rioting broke out. Governor Buford Ellington called out the Tennessee National Guard at 12:30 pm. and at 2:00 pm, sixteen year old Larry Payne, a black high school student, was shot and killed by Memphis cops. The policemen claimed that Payne was attempting to loot a service station on South 3rd Street, and that he attacked them with a butcher knife.

The situation degenerated further and by the time the smoke had cleared, Dr. King’s reputation as a proponent of non-violent protest was severely damaged. Wide rifts in Memphis were opened between blacks and whites, and between various segments of the black community itself. There were rumors that an FBI informant, who was also an undercover police spy in the Invaders, had incited the 28 March riot that ended in Payne’s death, and for all these reasons Dr. King was forced to return to Memphis to reclaim his status as an advocate of peaceful civil disobedience.

Kowalski ignores the importance of these events in the assassination of Dr. King. It is irrelevant to him that King and the Invaders formed an alliance in support of the Sanitation Workers, or that ninety percent of the garbage collectors were black. He never mentions the fact that the MPD was composed of 850 officers, of whom a mere 100 were recently appointed blacks; that tension between the white and black policemen was visceral; or that Arkin’s DIU was given the job of infiltrating and monitoring the Sanitation Workers union, King’s entourage, and the Invaders. The few black officers in the DIU who received this unenviable assignment were well known to other members of the black community, and came under intense criticism. For example, DIU undercover officer Edward Redditt, who met Dr. King’s party when it arrived in Memphis on 3 April 1968, was allegedly threatened with his life if he did not decease and desist. The situation was that explosive.

Prelude To An Assassination

Although Kowalski in the King Report seems unaware of the danger in Memphis, the various federal agencies that were monitoring Dr. King and the Invaders were not. Information on the most intimate details of the Sanitation Workers strike, and of the supporting role of Dr. King and the Invaders, was shared freely among them. But the most crucial information was invariably withheld from the subjects of their surveillance. For example, on 1 April 1968, the American Airlines office in Atlanta received a threat from anonymous white caller saying: “Your airline brought Martin Luther King to Memphis and when he comes again a bomb will go off and he will be assassinated.”[10]

The FBI, in what amounted to criminal negligence, notified every law enforcement agency, plus the 111th MIG, but not Dr. King. According to author Gerald McKnight, the orders to keep King in the dark emanated directly from Hoover. Members of the MPD DIU were aware of the threat as well, but they too declined to tell Dr. King.[11]

These issues bring us to one of the most provocative subjects of the Kowalski Report: the role of MPD DIU undercover agent Marrell McCullough in the assassination of Dr. King. For according to Loyd Jowers, McCullough was one of four people, along with MPD Homicide Chief N. E. Zachary, MPD Lieutenant Earl Clark, and Clark’s unnamed deceased partner, who plotted King’s assassination at Jim’s Grill. As fate would have it, McCullough also was the first person to reach Dr. King’s side after he was shot on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. Thus he deserves special attention.

Marrell McCullough

Described as “short, stocky, and dark,” Marrell McCollough was born in Tunica, Mississippi in 1944, and after earning a general equivalency high school degree, he enlisted in the US Army, serving “mostly” as a Military Policeman. According to what may or may not be accurate military records, McCullough was discharged in February 1967 and then fell off the radar screen for six months, until he entered the MPD police academy in September 1967. In February 1968 he became a full-fledged policeman and was assigned as an undercover officer in Eli Arkin’s DIU. His code name was “Max” and his job was to infiltrate the Invaders, which he did. Because he owned a VW hatchback, and because he claimed to be a Vietnam veteran, McCullough was made Minister of Transportation by Coby Smith.

McCullough’s FBI reports are still available in FBI archives, but most of his police reports were destroyed by the MPD in 1976, after the American Civil Liberties Union filed suit against City of Memphis. The files that survive indicate that McCullough liked to smoke pot with the Invaders, with whom he consorted for over a year, until he set up a drug bust in which many top Invaders leaders were entrapped. After that McCullough stayed in the MPD in other roles until he joined the CIA in 1974.[12]

Along with the missing reports, there are several reasons to consider McCullough as a suspect in the King assassination. To begin with, he misrepresented himself to the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA). McCullough was called to testify before the HSCA because he had attended a meeting with the Invaders and King on the night before the assassination, and because he was still on the premises of the Lorraine Motel when King was shot on 4 April 1968 – even though the Invaders has been ordered to leave by Reverend Jesse Jackson and Memphis-based Reverend Billy Kyles. In fact, McCullough was the first person to reach King. As he explained to the HSCA, “I ran to (King) to offer assistance, to try to save his life.” McCullough said he pulled a towel from a nearby laundry basket and tried to stop the bleeding.[13]

Also testifying before the HSCA was FBI agent William Lawrence. Now deceased, Lawrence was serving in Memphis in April 1968, but testified that he did not know McCollough. However, another FBI agent who was serving in Memphis in April 1968, Howell S. Lowe, told reporter Marc Perrusquia that, “Lawrence recruited McCollough well before King’s murder,” and that the FBI “used McCollough to report on campus radicals at Memphis State University, now the University of Memphis.”[14]

Supporting Lowe’s claim was DIU chief Eli Arkin, who told Perrusquia that he had selected McCullough “at Lawrence’s recommendation.” According to Perrusquia, “the FBI arranged McCullough’s placement in MPD Intelligence Squad.”[15]

Not only did FBI agent Lawrence lie to the HSCA, so did McCullough. He identified himself to the Committee as a “Police Officer” from Memphis, Tennessee, not as a CIA officer. When the HSCA asked McCollough if he had any relationship with CIA in April 1968, he said “no”. He also said “no” when asked, “Did you have any relationship with any other intelligence agency?”[16]

McCullough lied to Congress about his affiliation with the CIA and the FBI for one reason and one reason alone: the HSCA had reason to believe that McCullough was the FBI informant and MPD undercover agent who provoked the 28 March 1968 riot that resulted in the death of Larry Payne, and forced King to return to Memphis for his rendezvous with death.

In the absence of evidence to the contrary, however, McCullough was exonerated by the HSCA. But in view of his perjury, the question looms larger than ever. As Perrusquia notes, “The thoroughness of HSCA’s investigation now is open to question. Has McCollough told all he knows, or is he hiding something?”[17]

McCullough & The Plot At Jim’s Grill

Barry Kowalski ignores McCullough’s history of perjury in the King Report, but he is forced to confront the serious allegation Loyd Jowers made against McCullough. Kowalski deals with these allegations in characteristic style. According to Kowalski, Jowers was “suspiciously vague” when he said that he (Jowers) had met at Jim’s Grill with McCullough, Homicide Chief Zacharay, police Lieutenant Clark, and Clark’s deceased partner, to plot the assassination of Dr. King.

Of course Kowalski found no evidence to support the allegation. He talked to Zacharay, who “fully cooperated” and denied the allegation. Zachary said he “may have been” at Jim’s Grill later on the evening of 4 April, but his confusion was understandable and Zachary was believed. Clark’s wife said her husband was at home when King was killed, and she was believed too.[18] Clark’s deceased partner was unavailable for comment, leaving only Marrell McCullough.

At the time of his interview with Kowalski, McCullough was employed by the Central Intelligence Agency. Considering that fact, and the fact that the CIA has been implicated in the King assassination by members of the Jowers-Garrison-Spates cabal, Kowalski asked McCullough to take a polygraph exam. McCullough “cooperated” and agreed to take the test, which was administered by the Secret Service. In Kowalski’s own words, McCullough was found to be “not deceptive” when he denied plotting to harm Dr. King. “However, the polygraph was “inconclusive” as to his denial that he ever met with other police officers at Jim’s Gill.” [19]

“Not deceptive” implies something less than truthfulness, and to someone other than Kowalski, “inconclusive” polygraph results would certainly raise some doubts. But McCullough, like Zachary and the other Memphis cops, “cooperated” and therefore was believed, despite his inconsistencies. But only by using this double standard is Kowalski able to dismiss the provocative claim made by Jowers that McCullough played the crucial role of ”liaison” between the various elements of the assassination cabal.

The Continuing Cover-Up

Just as Kowalski is careful not to mention that FBI agent Lawrence and CIA agent Marrell McCullough lied to the HSCA, so too is the devious US Attorney willing to avoid other incriminating evidence that links the MPD, FBI, and 111th MIG to the assassination of Dr. King.

For example, Kowalski notes that, “Years prior to Jowers’ vague allegation, speculation focused on: (1) the withdrawal of the security detail assigned to Dr. King on April 3; (2) the supposed withdrawal of tactical units from the immediate area of the Lorraine; (3) the removal of two African American detectives from the surveillance post of Fire Station No. 2 on April 4; and (4) the removal of to African American firemen from the same firehouse on April 3.[20]

Without explaining that the HSCA was given a heavy dose of disinformation, as he is well aware, Kowalski says the Committee extensively examined the charges and found nothing untoward.

According to Kowalski, the police security detail, headed by MPD officer Don Smith, was withdrawn at Smith’s request because the King party was (here’s that word again) “uncooperative.” King’s party refused to provide King’s itinerary to Smith because they didn’t trust the cops, whom they felt had over-reacted the week before during the rioting. But Kowalski, using innuendos Posner probably contrived, characterizes this as an example of irrational black paranoia.

Then he proceeds, without any resolution or explanation, to contradict his own assertion. “The HSCA,” Kowalski notes, “never conclusively resolved whether it was the chief of police or another top official who actually approved Smith’s request.”

Does it matter if former FBI agent Holloman (who was close to Hoover and was in liaison with FBI agent Lawrence, who lied to Congress about knowing McCullough), removed the security detail? Of course it does! Especially if Holloman was relaying orders from Hoover. The HSCA ruled the security detail was improperly withdrawn, as Kowalski admits, but he doesn’t spend a moment trying to find out why. Kowalski’s indifference is absolutely amazing, but it is also an essential ingredient in his attempt to shift blame the assassination on Dr. King himself. [21]

Kowalski says, “In an affidavit to HSCA, TACT Unit Commander William O. Crumby stated that on 3 April he received a request from the King party to withdraw police patrols from within sight of the Lorraine.” The request, claims Kowalski, was “honored,” as if to imply it was honorable, but he then admits that the man who allegedly asked Crumby to withdraw the TACT units, Inspector Sam Evans, denied making the request. Again Kowalski sees no purpose in resolving this contradiction among cops, nor does he use that contradiction to impugn their reliability or consider the possibility that the security details were withdrawn, perhaps at the request of the FBI or CIA, in order to facilitate the assassination. Perish that thought.[22]

Likewise, when considering the removal of police officer Redditt from his surveillance post at Fire Station No. 2, a mere two hours prior to assassination, Kowalski again sees nothing sinister – despite the fact that Redditt was removed at the insistence of Philip R. Manuel, a staff member of the US Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, who “informed the Memphis Police Department of a threat to kill “a Negro lieutenant” in Memphis.” [23] Kowalski offers no explanation as to what Manuel was doing in Memphis, or by what authority he was able to direct the MPD, nor does he acknowledge that before joining the Senate staff as an investigator, Manuel spent his entire military career with the 902nd MIG, which William Pepper implicates in the assassination of Dr. King. Pepper also implicates Senator James O. Eastland (D-MS), who in 1968 was one of Manuel’s bosses. When asked by this writer why he failed to properly identify Manuel, Kowalski said that he could not discuss the subject, because Manuel’s testimony was “sealed.”

The Military & Martin Luther King

Using Gerald Posner’s strategy of disregarding anything that contradicts the case he wants to make, US Attorney Barry Kowalski refuses to address any issues that might suggest that King was killed by a cabal of lynch-mob mentality segregationists in the halls of Congress, the clean-cut FBI, the patriotic CIA, and the equal opportunity army. James Earl Ray is the only racist, according to Kowalski, who acted on his desire to kill Dr. King.

But what if these powerful Establishment forces did join together, under cover of Operation Lantern Strike, to create a situation in which someone like Ray could kill King and get away with it? Ironically, the best clues that such a conspiracy existed are to found within the context of institutionalized racism and government arrogance as represented by the King Report.

The first hints of this conspiracy were made public in The Phoenix Program, a book that detailed a secret CIA “assassination” operation in South Vietnam. Published in October 1990, the book reported a rumor that members of the 111th MIG had taken photographs of King and his murderer.

In an article published in November 1993 by The Memphis Commercial Appeal, reporter Stephen G. Tompkins expanded on this rumor. Citing unnamed sources, Tompkins said the 111th MIG “shadowed” King in Memphis, using “a sedan crammed with electronic equipment.”

Tompkins then went on to become an investigator for William Pepper, who further expanded upon this rumor in his 1995 book, Orders To Kill. Based on Tompkins’ sources, Pepper claimed that two unnamed members of the 902nd MIG were on the roof of Fire Station No. 2, and that they photographed King’s assassination and assassin. Based on information provided by Tompkins, Pepper also claimed that two members of the 20th Special Forces (code-named Warren and Murphy), attached to the Alabama National Guard, were on the roof of the Illinois Central Railroad Building overlooking the Lorraine Motel as part of an eight-man sniper squad that was in Memphis. Their assignment was to shoot the leaders, including King, if rioting broke out.

Foppish celebrity Gerald Posner in turn debunked Pepper’s theory in his book, Killing The Dream, in part by falsely claiming that the author of The Phoenix Program had fed Pepper the names Warren and Murphy.

Eventually, rumors about the presence of the 111th MIG in Memphis were finally substantiated by reporter Marc Perrisquia in a series of articles that appeared in The Memphis Commercial Appeal in late 1997. Perrisquia interviewed several members of the 111th MIG, including retired Col. Edward McBride, who oversaw the 111th’s Memphis mission from Fort McPherson in Atlanta. Perrusquia quotes McBridge as saying “We were never given any mission to keep King under surveillance. Never.”[24]

Perrusquia also interviewed retired Lieutenant Colonel Jimmie Locke, who in March and April 1968 commanded the 111th MIG’s special detachment in Memphis. In an apparent oversight, Perrusquia, however, neglected to ask Locke if he had sent anyone onto the roof of Fire Station No. 2. But Locke had – and in trying to dismiss that action as insignificant, the King Report descends into pulp fiction.

In signed affidavits prepared by William Pepper and dated September and November 1995, Stephen Tompkins states that he met with two members of an Army Special Forces team that was deployed to Memphis on the day of King’s assassination. These men, whom Pepper refers to as Warren and Murphy, claimed they were positioned on the roof of the Illinois Central Railroad Building overlooking the Lorraine Motel on 4 April 1968. According to Tompkins, Warren provided information linking the 902nd MIG to the Mafia crime family of Carlos Marcello, mystery man Raoul, and the assassination of Dr. King.

In his September affidavit,Tompkins states, “I have closely read the section of Dr. Pepper’s book concerning the military and I find it to be true and accurate to the best of my knowledge and belief.”[25] In the next paragraph Tompkins adds, “I can unequivocally state that everything he has written in the book about what I had done at his request and what I have said and reported to him and the process we followed is true and accurate. So far as I am concerned, his credibility and integrity in the pursuit of truth and justice in this case are unimpeachable.”

Likewise, Perrusquia, in a 4 May 1997 article for The Memphis Commercial Appeal, quotes Tompkins (then press secretary to Georgia Governor Zell Miller) as saying that Pepper had accurately characterized his investigation. Tompkins told Perrusquia, “I really respect the work that he (Pepper) does.”

However, when confronted by Kowalski, Tompkins disavowed Warren and Murphy. Tompkins allegedly told Kowalski, “that he never found anything to corroborate the Alabama National Guardsman and his observer and no longer believes them.”

Likewise, when confronted by Kowalski, Tompkins allegedly asserted that he did not believe his source from the 902nd MIG. Tompkins had reported to Pepper that this source, identified as Jacob Brenner in the King Report, was positioned on the roof of Fire Station No. 2 on the day of the assassination. As described in Orders To Kill, based on information provided by Tompkins, Brenner’s partner took photos of the assassination and of King’s assassin, who had fired the fatal shot from behind Jim’s Grill.

But Tompkins told Kowalski that Brenner was “a slimeball” whose story was no different that numerous false stories he had heard from conspiracy buffs asking for money, and that he would have said so if called as a witness at the King versus Jowers trial. [26]

Tompkins told Kowalski that he “found no evidence to substantiate that the 902nd MIG ever conducted a surveillance of Dr. King or was in Memphis. Rather, he determined that the 902nd MIG’s mission did not include domestic intelligence work..”

Kowalski claims The Department of Defense “confirmed Tompkins’ understanding that the 902nd MIG did not conduct domestic intelligence work.”

But that is totally untrue. A lie. This writer interviewed retired Colonel Alfred W. Bagot, who commanded the 902nd MIG from June 1968 until November 1968. When asked if the 902nd MIG conducted domestic intelligence operations, Bagot said, “Yes! Of course it did. The 902nd MIG was the principle source (of domestic intelligence) for the US Army Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence.”[27]

Why did Tompkins change his tune? What hammer did Kowalski hold over his head? Was it the allegation, raised by Perrusquia, that Tompkins was fired from a reporting job in Tulsa, Oklahoma, for forging a document? Did Tompkins forge documents in order to defraud Pepper? Was Tompkins working for military intelligence all along, as a disinformation specialist whose mission was to mislead Dr. Pepper?

Up On The Roof

“Notwithstanding Tompkins’ assessment of Brenner’s credibility and story,” Kowalski said, “we investigated whether military personnel from the 902nd MIG or from some other unit were on the roof of Fire Station No. 2, observed the assassination, or photographed a man with a rifle after the shooting.”[28]

A search of military documents uncovered no such evidence, and Kowalski was advised by Jimmie Locke that neither Locke nor anyone else from the 111th MIG “had firsthand knowledge that any military personnel were in the vicinity of the Lorraine on the day of the assassination or that military personnel conducted surveillance of Dr. King.” However, former 111th MIG sergeant Steve McCall did remember “somehow hearing that agents from his unit were being dispatched to the Lorraine on the day of the assassination,” but he could not recall the source of this information or any other details, so he was dismissed as being mistaken.[29]

One witness from the 111th MIG also admitted to being on the roof of Fire Station 2. James Green, then a Sergeant and investigator with the 111th MIG, recalled “going to the fire station on the day that King’s advance party arrived in Memphis, perhaps March 31st. He claims he went with another agent from his unit, whom he could not now recall (italic added), to scout for locations to take photographs of persons visiting the King party at the Lorraine Motel at a later time, if necessary. According to Green, someone from the fire station may have shown them to the roof, where he and the other agent remained for 30 to 45 minutes before determining it was too exposed a location from which to take photographs.”[30]

Although Kowalski ignores them, there are problems with Green’s inability to recall the name of his partner, as well as his description of the fire station roof. Jimmie Locke told this writer that,

“The 112th MIG (headquartered in San Antonio, Texas) sent a photographer to Memphis to get a picture of one of King’s lieutenants. I’ve forgotten the reason for wanting this, but one of the men assigned to me, James Green, took him up to the fire station roof to see if that would be an adequate spot from which to photograph. It wasn’t. They were on the roof less than five minutes and only that one time.” [31]

Locke doesn’t remember what day this was, but it certainly contradicts Green’s statement that he was on the roof with another member of the 111th MIG. This discrepancy raises the $64,000 question, never addressed by Kowalski, as to the identity of the second man on the roof. Was he perhaps a CIA agent with a rifle? If he didn’t find the fire station roof suitable, did he go elsewhere?

As to the roof being unsuitable for clandestine photography, Christopher Pyle, an expert on military surveillance, describes it as “perfect.” Pyle explains that the agents would have erected a tripod in the middle of the roof, so that only the camera lens would be visible over the parapet. The men would not have been seen looking over the rampart, nor would they have been visible to onlookers, as Kowalski contends.

The third problem is the testimony of Carthel Weeden, a former captain with the Memphis Fire Departmentwho was in charge of Fire Station No. 2 on the day King was killed. At the King versus Jowers trial, Weeden testified that on the afternoon of April 4, 1968, two men appeared at Fire Station No. 2 across from the Loraine Motel. They were carrying briefcases (which may have contained cameras and a tripod, and perhaps even weapons) and presented credentials identifying themselves as Army officers. They asked for permission to go to the roof. Weeden escorted them to the roof and watched while they positioned themselves behind a parapet approximately 18 inches high.

Their position gave them a clear view of the Lorraine Motel, the rooming house window from which Ray allegedly fired the shot that killed King, and the area behind Jim’s Grill. If the reader will recall, Jowers claimed the fatal shot was fired from behind his grill and that the assassin escaped down an alley, while Jowers brought the murder weapon into his diner.

Kowalski does not dig deeply into the military’s actions.[32] He doesn’t search for documents, and when it comes to contradictions, he does he apply the same standard to soldiers as he does to poor blacks. And when faced with the disturbing testimony of credible witnesses like Weeden, he relies on Posner’s strategy of dissembling.

According to Kowalski, Weeden was not sure they were military men, and he “acknowledged that his memory of an event 30 years ago might be inexact, and thus, it was possible that he took the military personnel to the roof sometime before – not the day of – the assassination. (Weeden) added that he had never spoken with anyone about his recollection until Dr. Pepper interviewed him…in 1995. Accordingly, Green’s recollection that military personnel went to the roof on a different day than the assassination appears accurate.”[33]

Weeden, who was never questioned by local or federal authorities about the presence of federal agents on the fire station’s roof, insists that he wasn’t even on duty the day before the assassination. A simple check of the fire stations would resolve this question, but Kowalski prefers to leave the innuendo dangling. Because innuendo is the best weapon he’s got.

Contradictions

Among the evidence that Kowalski ignores is a report, in the possession of Marc Perrusquia, which was passed to Memphis police, indicating that the 112th MIG warned the 111th MIG that four men, including one from Memphis, had purchased ammunition in Oklahoma on April 3rd and two rifles on April 4th.

Is this the message from the 112th MIG that prompted Jimmie Locke to send James Green to the roof of Fire Station No.2. If so, Green had to have been on the fire station roof with someone from the 112th MIG on the afternoon of April 4th, as Weeden says.

Kowalski also has no interest in the identity of a white man in a suit looking out a window of a room in the Lorraine Motel at the crowd of people standing around the body of Dr. King. Reporter Perrusquia believes this individual was with the 111th MIG or the FBI. Perhaps he was with the CIA? Perrusquia, who supports Posner’s theories and cooperated with Kowalski, believes there was closer FBI surveillance than previously acknowledged.

Perrusquia also believes there was a greater military involvement. He reported that “Senate hearings in 1971 explored abuses in an Army surveillance program established under President Lyndon B. Johnson after riots in Los Angeles in 1965 and Newark, N.J., and Detroit in 1967. At times, Senate investigators charged, the Army exceeded its authority, crossing into improper political surveillance that included filming demonstrators in Chicago and keeping dossiers on civilians. When caught in such direct surveillance, the Army often denied it (italic added), saying it got information from sources such as the FBI, which had jurisdiction for most domestic intelligence and kept intense watch on King.”[34]

If Perrusquia can admit that the military covered-up its illegal activities in other cities, why can’t Kowalski strive to resolve the contradictions of government officials, and uncover what was really going on in Memphis? Why does the King Report ignore the FBI and military’s belief that the black movement was led by Communists, and that King, whom they hated, was dangerous to the well being of the nation?

More than James Earl Ray, the FBI, CIA, and military had the motive, means, and opportunity to kill Dr. King. And that’s a fact.

Kowalski says the HSCA dismissed the idea that Marrell McCullough was the agent provocateur who incited the riot that prompted King to return to Memphis and a rendezvous with death. In fact, Kowalski only cites conclusions reached by the HSCA that support his own. [35]

Consistent with his methodology, nowhere in the King Report does he cite the testimony of former US Representative Walter Fauntroy at the King versus Jowers trial. Fauntroy, who chaired the HSCA sub-committee that investigated the King assassination, complained that his committee might have proven there was more than just a low-level conspiracy, if the FBI and military been forthcoming in 1977.

But the FBI and military lied, and according to Fauntroy, “it was apparent that we were dealing with very sophisticated forces.” Fauntroy’s phone and television set were bugged, and when his investigator, Richard Sprague, requested files from the intelligence agencies he was forced to resign. The records were not sought by Sprague’s replacement, and the investigation failed to uncover any hint of government involvement in the King assassination.[36]

However, Fauntroy has since come to believe that James Earl Ray did not fire the shot that killed King, and was part of a larger conspiracy that possibly involved federal law enforcement agencies. Upon leaving Congress in 1991, Fauntroy “read through his files on the King assassination, including raw materials that he’d never seen before. Among them was information from J. Edgar Hoover’s logs. There he learned that in the three weeks before King’s murder the FBI chief held a series of meetings with “persons involved with the CIA and military intelligence in the Phoenix operation in Southeast Asia.

Fauntroy also discovered there had been Green Berets and military intelligence agents in Memphis when King was killed. “What were they doing there?” he asked researcher James W. Douglas.[37]

If he did nothing else to arrive at the truth, Kowalski should have demanded that the HSCA records, which are sealed until 2029, should be opened. But Kowalski’s only concern is perpetuating the cover-up, which is why he sweeps over the testimony of Maynard Stiles, a senior official in the Memphis Sanitation Department who claimed at the King versus Jowers trial that he and his crew cut down the bushes behind Jim’s Grill on the day after Dr. King was assassinated. Stiles received his instructions from MPD Inspector Sam. In other words, ‘within hours of King’s assassination, the crime scene that witnesses were identifying to the Memphis police as a cover for the shooter had been sanitized by orders of the police.”[38]

Kowalski also ignores the Mafia’s role in the assassination, for one simple reason. The Invaders knew the Mafia was peddling drugs to blacks, with police protection. And to investigate the Mafia would necessarily result in uncovering its modus vivendi with law enforcement.

Cody Smith reminds us of what happened to the Blackstone Rasgers in Chicago. “When the Rangers went after the Italian drug wholesalers, the FBI wiped them out,” he observes.”

Not wanting to suffer the same fate, the Invaders scattered after the assassination and many, till this day, live in fear of being killed. Which is why one of them will not testify about his having seen Marrell McCollough at Jim’s Grill.

Kowalski in the King Report conveys no understanding of the racial situation in Memphis, or why Betty Spates would be confused by events beyond her comprehension. Instead, he cynically plays her eye-witness word against the theoretical word of Gerald Posner, the fancy celebrity who has dinner and drinks with Dan Rather, and helped Kowalski write his report.

Regarding the rift in the black community, Kowalski is definitely on the side of those blacks, like Marrell McCullough, Jesse Jackson, and the Reverend Billy Kyles, who religiously cooperated with law enforcement. As Reverend Fauntroy is happy to point out, Reverend Jackson since the assassination has regularly cooperated with the CIA.

Thus Kowalski dismisses the allegations that Jesse Jackson ordered the Invaders to leave the Lorraine Motel, and that Reverend Kyles lured Dr. King onto the balcony, as part of the conspiracy.

As outlandish as those allegations may be, Kowalski’s sins of omission indicate consciousness of guilt, and thus it is still impossible to determine the truth.

The Smear Campaign

In the absence of any “truth”, Kowalski and the federal government have initiated a smear campaign, of which the King Report is part and parcel, in order to silence the King family and prevent any further investigations into the King Assassination.

The smear campaign began with Gerald Posner‘s book, Killing The Dream, and was advanced immediately after the King versus Jowers trail, when leading newspapers across the country immediately denounced the verdict as a one-sided presentation of a mad conspiracy theory. The Washington Post even lumped the conspiracy proponents in with those who insist that Hitler was unfairly accused of genocide.

Since the trial, Kowalski and Posner have gathered support among those members of the black community who resent the position adopted by Corretta King and her sons. For example, on 27 March 2000, Time Magazine columnist Jack E. White, in an article titled “They Have A Scheme”, described the King family’s conspiracy theory as “lurid fantasies” that “sprang from the fertile imagination of Ray’s former lawyer, William Pepper.”

According to columnist White (to whom Kowalski leaked an early version of the King Report) , Pepper cast a “bambozzling spell” over the King family, and “(t)he real mystery is why King’s heirs, who more than anyone else should want the truth, prefer to believe a lie.”

But perhaps, as indicated by the information provided in this article, the Kings know something that Mr. White, the Establishment press, and the Justice Department aren’t telling the American public? Indeed, if government agencies were involved in the conspiracy from the beginning, why would the Justice Department now want to reveal the truth?

To date, James Earl Ray stands as the lone assassin, possibly as part of a low-level conspiracy of a few white racists who despised King for his role in ending segregation. But for three decades, Ray declared his innocence. And researchers now, as in the case of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, must nibble away at the myths, and dig deep for new material evidence.

The Next Step

The next step in uncovering new evidence in the King assassination case is being taken by attorney Daniel Alcorn, who obtained, through the Freedom of Information Act, the After Action Report of the Civil Disorder Operation: LANTERN SPIKE, 28 March – 12 April 1968. Written by members of the 111th MIG, the Report casts light on the activities of the military on the day Dr. King was killed.

However, when Alcorn asked the Pentagon for copies of the daily reports of the 111th MIG and the 902nd MIG, the military claimed to have lost the records somewhere between the National Archives and the Center For Military History. In March 2000 a federal judge supported the military’s claim that it was not responsible for locating the documents, and Alcorn filed an appeal.

Let it be known that the military is lying when it says it cannot find the records. The records exist and some of them were provided in 1997 to Marc Perrisquia by the chief of Public Affairs at the Pentagon, Colonel John Smith. Perrisquia provided copies of these documents to Barry Kowalski, who is aware of Alcorn’s lawsuit and appeal, but has failed to notify him or the judge of their existence.

Thus the venal cover-up continues at all levels, casting further shame on the federal government. Just as the MPD destroyed its files on Marrell McCullough, the 111th MIG and other Army intelligence units are in the process of destroying any records that might implicate the military, the CIA, or the FBI in Dr. King’s assassination.

This only confirms the sad truth that the government knew the plotters were out there. The intelligence agencies feared the up-coming Poor People’s march in Washington, and they feared Dr. King’s anti-War rhetoric, and if they didn’t actually do the job themsleves, they let it go down.

As evident in the King Report, Barry Kowaklski’s job was to maintain the cover-up. Kowalski selected and interpreted, and ruth to Americans is what supports their prejudices and biases

NOTES

[1] The King Report’s full title is United States Department of Justice Investigation of Recent Allegations Regarding the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

[2]According to Kowalski the motley crew of disreputable hustlers included James McCraw, Willie Akins, Betty Spates, Nathan Whitlock, Louis Ward, William Hamblin, James Isabel, and James Milner, several of whom connected the Mafia to the assassination through the CIA. Kowalski found no Mafia of CIA involvement.

[3] King Report, Part 3, Page 15.

[4] Douglas, James W., Probe Magazine, May-June 2000.

[5]Fire Station No. 2 occupies the space on Butler Street between Mulberry Street and South Main. The rear of Fire Station No. 2 overlooks the Lorraine Motel on Mulberry, and the entrance to the Fire Station, on South Main (an area now gentrified and filled with art galleries) is just down the street from Jim’s Grill and the flop house above it, from which Ray allegedly shot King.

[6] Douglas, James W., Probe Magazine, May-June 2000.

[7] King Report, Part 3, Page

[8]Invader Charlie Cabbage had information that James Earl Ray was at the Lorraine Motel the night before King was shot. Invader Coby Smith is certain that someone other than Ray or Clark fired the fatal shot from behind Jim’s Grill.

[9]McKnight, Gerald, The Last Crusade: Martin Luther King, Jr., the FBI, and the Poor People’s campaign. Westview Press, 1998, Boulder, Colorado. P 142,

[12]Perrusquia, Marc, The Memphis Commercial Appeal, 2 August 1998.

[13]Perusquia, Marc, Memphis Commercial Appeal, 2 August 1998.

[18]DIU agent Redditt is on record as having said that Clark might have been involved in the assassination because he was an expert shot and a racist, but Redditt’s opinion was dismissed. Clark’s widow said he was friends with a mobster named Liberto, but Kowalski decided it was another Liberto, not Frank Liberto, whom Jowers claimed was the man who organized the assassination.

[19] King Report, Part 3, Page .

[20] ibid, Part 3, Page 33.

[21] King Report, Part 3, Page 34.

[23] Military surveillance expert Christopher Pyle contends that Manuel would never have had the authority to make such a request.

[24] Perrusquia, Marc, 30 November 1997, The Memphis Commercial Appeal.

[25](Which is not surprising, as Pepper based those passages on Tompkins’ research.).

[26] King Report, Part 6, Page 7.

[27]Bagot succeeded Colonel John W. Downie, who commanded the 902nd MIG from February 1967 until June 1968, and was its commander when King was killed. Locke describes the 902d MIG as “an odd-ball unit, stationed at the Pentagon, not assigned to an Army area. We called them the “Black Shirts” as they often got tasks beyond the normal level of sensitivity.”

[28] King Report, Part 6, Page 7.

[29] King Report, Part 6, Page 8.

[31] Reporter Perrusquia has a copy of a telex from the 112th MIG in San Antonio, to the 111th MIG, reporting that people at Oklahoma State had purchased 306 rifles and were on their way to Memphis. Notably, the weapon that killed Dr, King was a 306 rifle. (Perrusquia, 2 August 1998, The Memphis Commercial Appeal.)

[32] In 111th Reports leading up to 4 April, there is no mention of Green at all. Who is Green?

[33] King Report, Part 6, Page

[34] Perrusquia, Marc, date, The Memphis Commercial Appeal

[35] It is rumored that McCollough was an undercover agent with the 111th MIG.

[36] Douglas, James W. Probe Magazine, May-June 2000.