The dust jacket for The Plot to Kill King quotes former United States Attorney General Ramsey Clark as stating that “No one has done more than Dr. William F. Pepper to keep alive the quest for truth concerning the violent death of Martin Luther King.” This is unassailably true. Dr. King’s murder has never received anything approaching the level of attention and scrutiny that has been afforded the assassination of President Kennedy but, for nearly three decades, Pepper has worked tirelessly to uncover the truth and bring it to the attention of the American public. As he chronicles in his latest book, Pepper was the last attorney for accused assassin James Earl Ray before his death, and tried every avenue available to him to gain his client the trial he had been denied in 1969 when the state of Tennessee and his own lawyer, Percy Foreman, broke Ray down and coerced him into entering a guilty plea.1 Pepper and his investigators spent many, many hours locating overlooked witnesses, uncovering leads, and assembling a case. Then in 1993 he took part in a televised mock trial that resulted in a “not guilty” verdict for Ray.2 After Ray died in 1998, and any and all possibility of a real criminal trial went with him, Pepper worked with the King family in filing a wrongful death lawsuit against Loyd Jowers and “other unknown co-conspirators” so that the information he had uncovered could still be put before a jury. After 14 days of testimony from over 70 witnesses, the jury found that Jowers and others, “including governmental agencies”, were responsible for the death of Martin Luther King.3

|

| William Pepper |

Yet Pepper is and always has been a controversial figure, even among those who share his disbelief in the official story. For example, Harold Weisberg – who worked as an investigator for Ray’s defense team in the early 1970s and wrote the classic MLK assassination book, Frame Up – referred derisively to Pepper as “a would-be Perry Mason” and described his work as “worse than worthless.”4 On the other hand, the late, great Philip Melanson once described Pepper’s research and investigation as “groundbreaking” when it came to “establishing the presence of Army Intelligence and Army Intelligence snipers” in Memphis on the day of the murder.5 Over the years, this reviewer has adopted something of an agnostic position when it comes to areas of Pepper’s work. Whilst there is undoubtedly great value in what he has uncovered and accomplished, it nonetheless remains true that there a number of legitimate reasons for doubting important elements of Pepper’s research.

|

| Loyd Jowers |

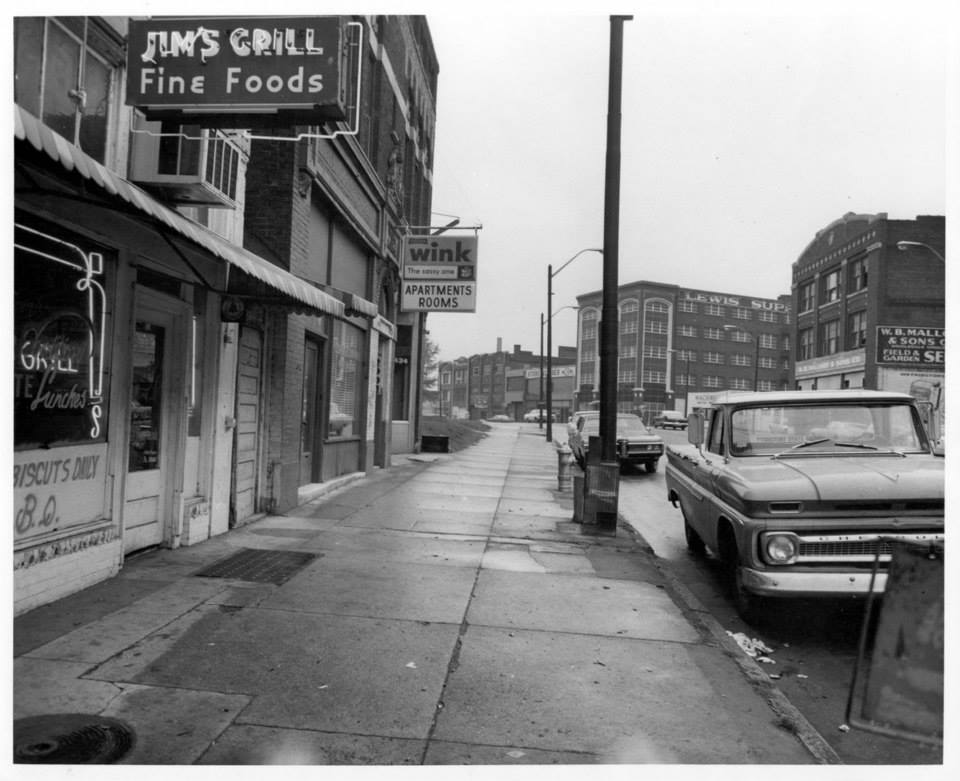

Take for example the man at the very centre of Pepper’s conspiracy narrative, Loyd Jowers. In 1968, Jowers was the proprietor of Jim’s Grill, a restaurant located underneath the rooming house from which the state alleges Ray fired the fatal shot. For many years the only thing Jowers had to say that was of any interest to investigators was that a white Ford Mustang had been parked directly in front of the grill on the afternoon of the assassination; corroborating Ray’s claim of where he had parked his car and helping establish the presence of two white Mustangs on Main Street. But in 1993, Jowers appeared on ABC’s Prime Time Live claiming that Memphis-based produce dealer and alleged Mafia figure, Frank Liberto, had contacted him shortly before the assassination and paid him $100,000 to hire someone to assassinate Dr. King. He was then visited by a man named Raul who handed him a “rifle in a box” and asked him to hold onto it until “we made arrangements, one or the other of us, for the killing.”6

On the face of it, Jowers’ story seems plausible enough. There is no doubt that he was at the scene of the crime and in a position to assist in carrying out the assassination. Additionally, parts of his account were corroborated by two other witnesses: former Jim’s Grill waitress, Betty Spates, and local Memphis cab driver, Jim McCraw. Also, Jowers’ claim that Frank Liberto brought him into the plot recalls the statement of civil rights leader John McFerren that, sometime in the afternoon shortly before Dr. King was shot, he overheard Liberto telling someone on the telephone to “Shoot the son of a bitch when he comes on the balcony.”7 And yet Jowers was, by any definition, a most unreliable witness. By Pepper’s own admission there were numerous different versions of his story. In fact, he contradicted himself on virtually every important detail.

|

| Jim’s Grill |

He initially named black produce-truck unloader Frank Holt as the gunman he had hired but changed his mind after Holt was found alive and well and passed a polygraph test, denying any involvement.8 Jowers then hinted that deceased Memphis Police Lieutenant Earl Clark was the real gunman only to tell Dr. King’s son, Dexter, that he “couldn’t swear” that he was because “All I got was a glance of him.”9 To Dexter, Jowers said that the gunman handed him the still smoking rifle, yet at an earlier time he had claimed to have picked it up after it had been placed on the ground.10 Around this time he also changed his mind about ever having been asked to hire the gunman, saying instead that he had simply been told to be out in the bushes behind Jim’s Grill at 6:00 PM and that he didn’t even know Dr. King was going to be killed.11 In this scenario, Jowers merely held onto the $100,000 until it was collected by a co-conspirator.

Perhaps even more troubling than these inconsistencies – of which there are more – is the fact that Jowers and his friend Willie Akins are known to have contacted Betty Spates in January 1994 saying that they were interested in doing a book or a movie and they needed her to change her story. If she would say that she saw a black man handing the rifle to Jowers immediately after the shooting, they could all make $300,000.12 And if that wasn’t bad enough, in an April 1997 tape-recorded conversation with Shelby County district attorney general’s office investigator, Mark Glankler, Jowers basically disavowed his confession by stating that Ray’s rifle was the real murder weapon and that “there was no second rifle.”13

It may also be seen as significant that Jowers never did repeat his conspiracy allegations under oath. He was not actually present for the King v. Jowers civil trial, apparently owing to ill health. The only time he gave a legal deposition after his appearance on Prime Time Live was during the 1994 Ray v. Jowers lawsuit, at which time he reverted to his 1968 story and insisted that he was in the bar serving drinks when the shot was fired. Jowers had agreed that the transcript of his Prime Time Live appearance could be entered into evidence but, through his attorney Lewis Garrison, stipulated “that the questions were asked and Mr. Jowers gave these answers”.14 Thus he did not swear to the accuracy of his alleged confession, he merely agreed that he had given it.

In The Plot to Kill King, Pepper attributes Jowers’ many contradictory assertions to his fear of being prosecuted and an understandable desire to minimize his own role when talking to members of the King family. Pepper also argues, in spite of Jowers’ attempt to encourage Spates to lie for her share of $300,000, that it is “arrant nonsense” to suggest that he fabricated his story “in anticipation of a book or movie deal.” In fact, he says, “Jowers lost everything. Even his wife left him. There was no book or movie deal, and he was, for the most part, telling the truth.”15 Yet none of these arguments preclude the possibility that Jowers’ confession was invented as part of a money-making scheme that backfired.

That being said, it should be borne in mind that Jowers’ initial Prime Time story did not come completely out of the blue. Suspicion had already been cast on him by statements that Spates and McCraw had given to Pepper, after which Jowers’, through Garrison, had contacted the Shelby County district attorney general offering to tell everything he knew in exchange for immunity from prosecution. Needless to say his proffer went completely ignored without anyone even attempting to speak with him. Assistant district attorney general, John Campbell, would later attempt to justify this total lack of interest by stating that the story looked “bogus” and that if they had given Jowers immunity “it would imply we thought there was some validity to his story, and that would increase the value of what he could sell it for.”16 Precisely how they were able to deduce immediately and without even talking to Jowers that his story was “bogus” is anyone’s guess.

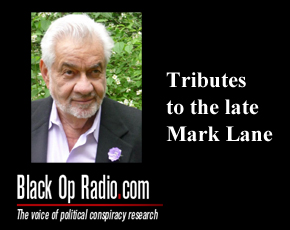

In the end, it will be up to each individual researcher to decide which, if any, of Jowers’ varying accounts to believe. Whilst it is true that the jury in King v. Jowers did find him partly responsible for the assassination, it is also true that his assertions were not thoroughly tested at the trial because neither Pepper nor Garrison were looking to undermine Jowers’ credibility. Legendary attorney, author, and activist, Mark Lane, was critical of the trial for that very reason, telling this reviewer that in his opinion, “It was not a real trial … both sides offered the same position and I have reason to doubt that the position they offered was sound. The jury, having seen no evidence to the contrary, had no choice. In my view, the court system should not be utilized in that fashion.”17

|

| Mark Lane with James Earl Ray |

Lane’s assessment is, in my view, somewhat off the mark in that it suggests a type of collusion between Pepper and Garrison that was likely not the case. In truth, Garrison was in an extremely awkward position. He could not simply deny the existence of a conspiracy without calling his own client a liar, so his strategy was to attempt to minimize Jowers’ role and convince the jury that, as he stated in his closing argument, “Mr. Jowers played a very, very insignificant and minor role in this if he played anything at all. It was much bigger than Mr. Jowers, who owned a little greasy-spoon restaurant there and happened to be at the location he was.”18 In that regard, it worked to Garrison’s advantage to allow Pepper to put on a case for a wide-ranging conspiracy without offering a rigorous challenge. Nevertheless, the result of this strategy, as Lane suggested, was that the jury essentially heard one story from both sides and for that reason the verdict was far from surprising.

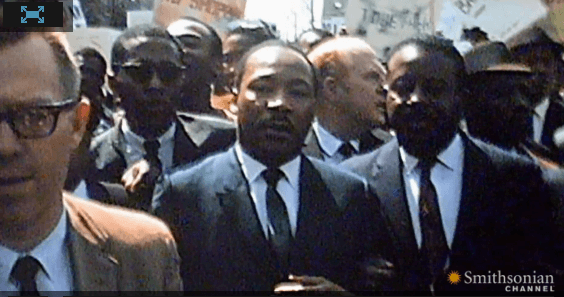

By noting these circumstances, it is not meant in any way to suggest that the civil trial or the jury’s verdict were entirely without merit. On the contrary, as Pepper details in The Plot to Kill King, numerous witnesses gave significant and often startling testimony under oath – many for the first time – and put important evidence on the record. For example, a succession of witnesses provided evidence establishing the manner in which Dr. King was, seemingly intentionally, stripped of all reasonable security, and left entirely vulnerable to a sniper’s bullet. Of particular note is the testimony of Memphis Police Department homicide detective Captain Jerry Williams who had been in charge of organizing a unit of black officers that had previously provided protection for Dr. King on his visits to Memphis. Williams said that he was not asked to form his unit on Dr. King’s final, fatal visit, and was later falsely informed that Dr. King’s organization, the SCLC, had said Dr. King did not want protection.19 Additionally, as University of Massachusetts Professor Philip Melanson testified, MPD Inspector Sam Evans had ordered the emergency services’ TACT 10 unit removed from the vicinity of the Lorraine Motel, claiming this too was done at the request of someone in the SCLC. As Pepper writes, “When pressed as to who actually made the request, he said that it was Reverend [Samuel] Kyles. The fact that Kyles had nothing to do with the SCLC, and no authority to request any such thing, seemed to have eluded Evans.”20

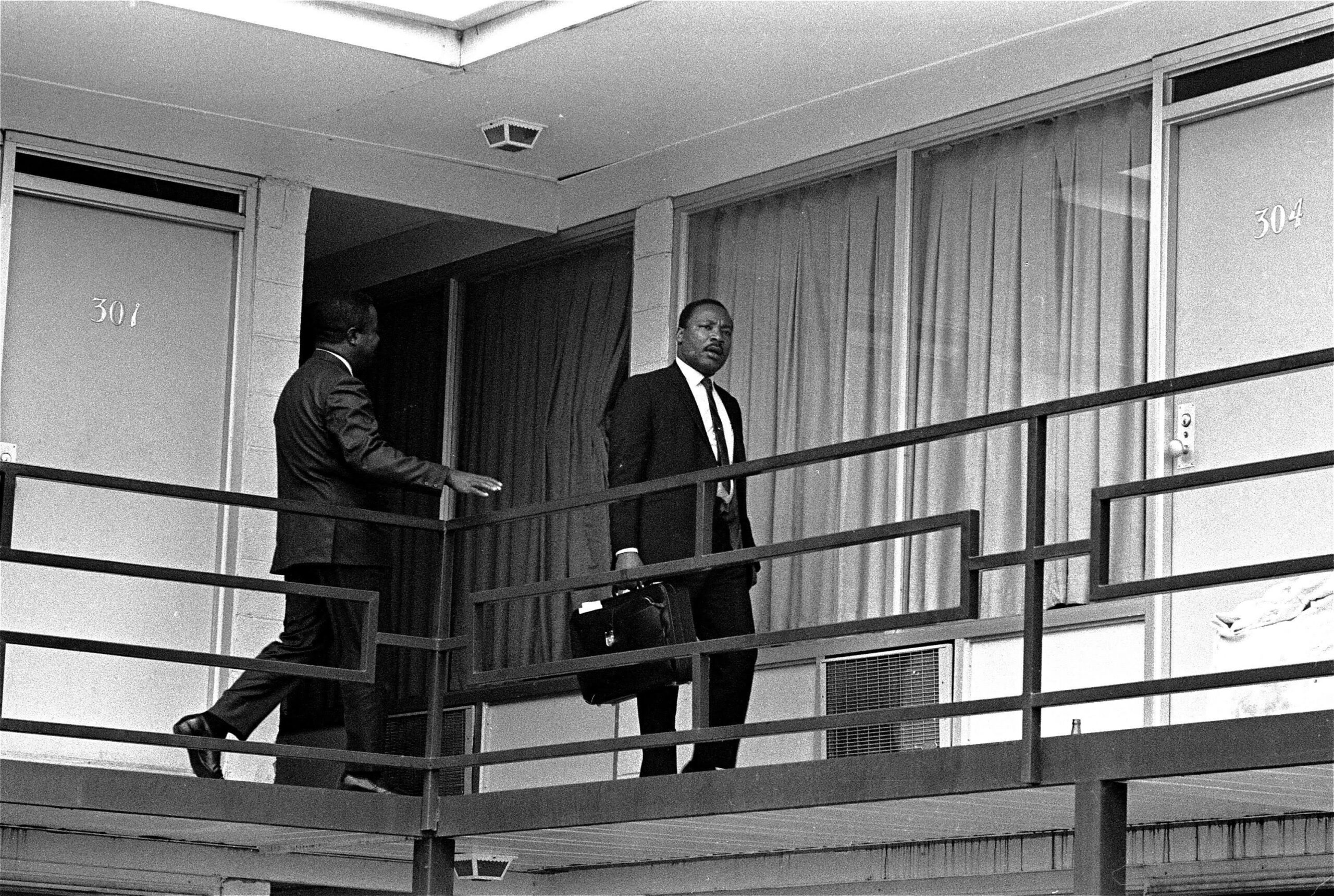

Not only had Dr. King been stripped of protection but a last-minute switching of his motel room had made the assassin’s job all the easier. Former New York City police detective Leon Cohen testified that Lorraine Motel manager Walter Bailey told him on the morning after the assassination that Dr. King had originally been allocated a more secure courtyard room. But on the evening before his arrival, Bailey had received a call from someone claiming to be from the SCLC’s Atlanta office requesting Dr. King be given a balcony room instead. Bailey said he was “adamantly” opposed to the change “because he had provided security by the inner court” but his caller had insisted the rooms be switched anyway.21 Needless to say, no genuine member of the SCLC is known to have made any such request.

|

| King on the Lorraine balcony |

As well as being shown how Dr. King was maneuvered into a vulnerable position, the Memphis jury also heard much evidence helping to establish James Earl Ray’s probable innocence. The state has always maintained that Ray holed himself up in a shared bathroom in the rooming house opposite the Lorraine and waited until Dr. King appeared on the balcony at approximately 6:00 pm. After supposedly firing the fatal shot, he is said to have rushed back to his rented room, put the rifle in its box, placed it amongst a bundle of his belongings, then ran down the stairs to the ground floor. Once outside, he allegedly dumped his bundle in the doorway of Canipe’s Amusement Company, climbed into a white Mustang parked just south of Canipe’s, and quickly sped away.

Pepper provided evidence that successfully countered every step of this most likely false narrative. The notion that Ray had been lying in wait in the bathroom was contradicted by the sworn deposition of James McCraw, who had been in the rooming house only a few minutes before Dr. King was shot. McCraw said that he saw the bathroom door wide open and there was no one inside.22 Raising the possibility that the shot was actually fired from the thick shrubbery below the bathroom window, Pepper read into the record the sworn statement of SCLC member Reverend James Orange who said that he saw what he thought was gun smoke rising from the bushes immediately after he heard the shot.23

Ray’s alleged flight down the rooming house stairs had, according to the state, been witnessed by Charles Stephens, who occupied the room between the bathroom and the room Ray had rented. But his ability to witness anything was called into question by taxi driver McCraw, who had been called to the rooming house specifically to pick Stephens up. McCraw said that he found Stephens lying on his bed, too drunk to even get up.24 McCraw’s account was corroborated by the testimony of MPD homicide detective Tommy Smith who entered the building shortly after the assassination and found Stephens still so intoxicated that he could hardly stand.25 Not mentioned at the trial was the fact that two weeks after the murder, Stephens had been shown a picture of Ray by CBS news correspondent Bill Stout and failed to recognize him. In fact, he said Ray was “definitely not” the man he claimed to have seen fleeing the rooming house.26

|

| Judge Joe Brown with the supposed murder weapon |

Criminal Court Judge Joe Brown, who had presided over Ray’s final appeal, took the stand to testify about a series of ballstics tests that he had ordered be performed on the Remington Gamemaster rifle found in the doorway of Canipe’s. The FBI had never been able to establish that particular rifle as the murder weapon – supposedly because the bullet removed from Dr. King’s body was too mutilated. Judge Brown, himself a ballistics expert, explained that 12 of the 18 bullets fired during his tests had contained a similar flaw – a bump on the surface – that was not present on the death slug. He also said that the rifle had never been sighted in and, as a result, had failed the FBI’s accuracy test. “ … based on the entirety of the record”, Brown said, “and the further ballistics tests I had run, it is my opinion this is not the murder weapon.”27 Brown’s opinion was re-enforced by the testimony of Judge Arthur Hanes, Jr., who, alongside his father, had been Ray’s defense attorney before Ray made the fatal mistake of hiring Percy Foreman. Judge Hanes told the court that Guy Warren Canipe had said to him in 1968 that the bundle containing the rifle had been dumped in the doorway of his store approximately 10 minutes before the assassination and he was prepared to testify to that effect.28

Finally, Pepper showed, through the FBI statements of Ray Hendrix and William Reed, that James Earl Ray had most likely left the scene in his white Mustang shortly before the assassination, not immediately after. Ray always maintained that he parked his car directly in front of Jim’s Grill, not south of Canipe’s, and that he left the area sometime between 5:30 and 6:00 pm to try to get his spare tire fixed. The April 25, 1968, statements of Hendrix and Reed corroborated Ray’s account. The pair told the Bureau that they had left Jim’s Grill at approximately 5:30 pm and noticed a white Mustang parked directly outside. When Hendrix realised he had forgotten his jacket, he went back into the grill to retrieve it whilst Reed stood staring at the car. When Hendrix reappeared the two walked a couple of blocks north on South Main Street until they reached the corner of Main and Vance, at which point what appeared to be the very same Mustang, driven by a lone, dark-haired man, rounded the corner in front of them. This independent confirmation of Ray’s movements, essentially constituting an alibi, was hidden from the defence and the FBI kept the crucial documents from the public for decades.29 Finding these statements and having them entered into evidence, as they should have been in 1969, is one of the many things for which Pepper is to be applauded.

Another is his effort to locate and identify the mysterious figure previously known only as “Raoul” or “Raul”. For those unfamiliar with the King case, Raul was the name of the man whom Ray always claimed had set him up for the assassination. Shortly after his escape from the Missouri State Penitentiary on April 23, 1967, Ray made his way to Montreal, Canada, hoping to obtain the travel documents he needed to flee the country. It was there in a place called the Neptune Bar that he said he met Raul, a dark-skinned man with a Spanish accent, who promised to provide the documents Ray needed if he agreed to smuggle some items across the border. For the next several months, Ray said, he received large sums of money – including $1,900 to buy the Ford Mustang – and followed Raul’s instructions. According to Ray, these instructions ultimately included purchasing the Remington Gamemaster rifle and renting a room at the flophouse opposite the Lorraine Motel.

|

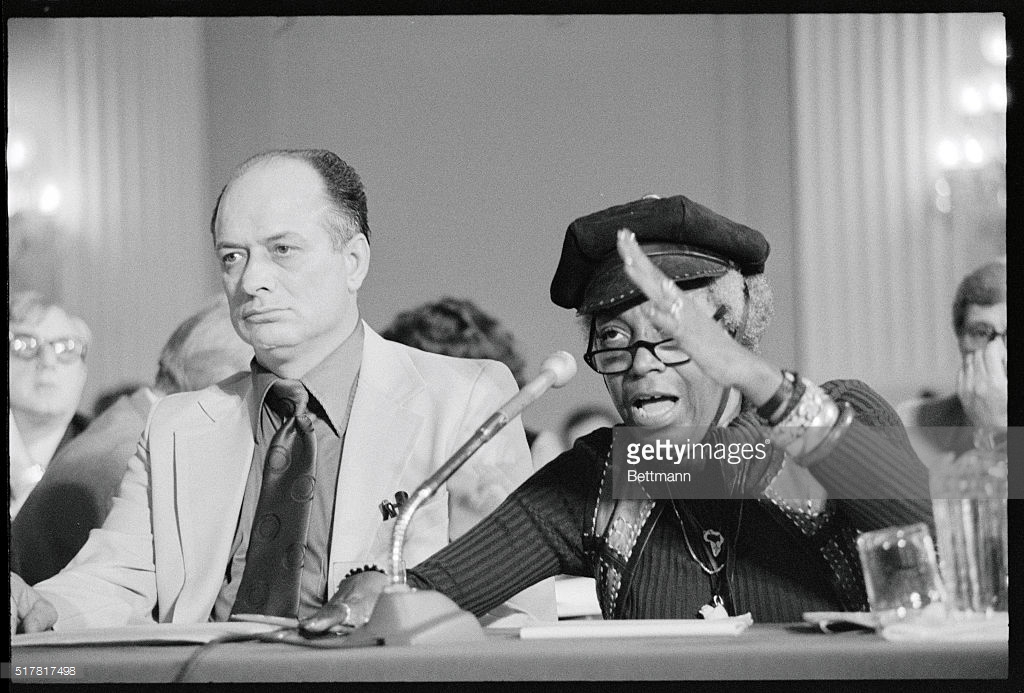

| Jerry Ray before the HSCA |

Needless to say, the state and its defenders have always maintained that Raul did not exist. Yet as Pepper points out, this leaves them with the problem of accounting for the large sums of money Ray was known to have spent whilst having no other known source of income. Desperate to explain this away, the HSCA theorized that Ray and his brothers had robbed a bank in Alton, Illinois. “The problem with this ‘theory’”, Pepper writes, “is that I called the local sheriff and the bank president in Alton. I was advised that they knew James had nothing to do with the robbery. The real culprits were known but there was not enough evidence to charge them.”30 On Pepper’s advice, Ray’s brother Jerry surrendered himself to the Alton police in 1978, offering to waive the statute of limitations so that he could be charged. He was promptly informed that neither he nor his brothers had ever been suspects.31

Because Ray was a largely incompetent crook, and because he was never the violent racist that the media falsely made him out to be, those who spent any length of time with him rarely doubted his claim that he had been set-up by someone. Quite simply, the idea of Ray as a lone nut assassin has never made any sense. As Arthur Hanes Sr. is said to have remarked, “Unless Ray is a complete damn fool I don’t see how he could have made the decision to kill King. Before King was killed, Ray was doing all right. He was free, able to support himself with smuggling and stealing. He was driving a good car all over Canada, the United States and Mexico. He was comfortable, eating well, finding girls, and nobody was looking for him. Why then would he jeopardize his freedom by killing a famous man and setting all the police in the world after him?”32 Indeed, one might ask why Ray, being on the run from prison and desiring little more than to leave the United States for a country with whom the US had no extradition treaty, would have even re-entered the country in the first place after having made it as far as the Montreal docks? It might well be said that Ray’s actions following his prison break only make sense if we accept that someone was manipulating him.

Pepper believed Ray’s story and, soon after agreeing to represent him, set out to find Raul. Eventually Pepper’s investigators came into contact with a rather eccentric witness named Glenda Grabow who told them that in the 1970s she had been involved in gunrunning, among other illegal activities, with a man whose nickname was “Dago” and that he had confessed to her his involvement in the murder of Dr. King. Meanwhile Pepper, who heard a rumour that Raul was living in the northeast, had zeroed in on an individual named Raul Coelho, living in Upstate New York. Investigators John Billings and Ken Herman obtained a picture of this Raul taken in 1961 when he emigrated to the US from Portugal, placed it amongst a spread of six photographs, and showed them to Grabow. According to Herman, “she pointed out Raul with no hesitation. She was sitting at the kitchen table in my house and zeroed right in on the guy.” The spread was then shown to Glenda’s younger brother, Royce Wilburn, who also knew “Dago” and he too identified the picture of the New York Raul.33

Billings then took the obvious next step and showed the spread of photographs to Ray in his cell at Riverbend Prison in Nashville, Tennessee. As Billings later testified, “I told him we had a picture of Raul. And he seemed somewhat surprised. And I asked him if he would choose to attempt to pick out Raul in a photo spread … So we put this before him, and James put on his glasses and very – for a minute or two studied these pictures very carefully.” He then dropped his finger down on the picture of the New York Raul and said “that’s Raul.” Asked if he was positive Ray said, “Yes, I am.”34

The pictures were also shown to British merchant seaman Sid Carthew who had come forward after watching a video tape of the televised mock trial saying that he too had met a man named Raul in the Neptune Bar, Montreal, in 1967. Over the course of two evenings, Raul had offered to sell him some Browning 9mm handguns. “He said to me, how many would you want, and I said four … and he said, four, what do you – four, what do you mean by four. I said four guns. He wanted to sell me four boxes of guns … once he knew that I would have only take – took four, he was very annoyed … it wouldn’t be worth his while to deal in such a small number, and that was the end of the conversation, and he went back to the bar.”35 Carthew selected the same photograph from the spread as Grabow, Royce, and Ray had before him. And according to Pepper, so too did Loyd Jowers.36

In its response to the King v. Jowers trial and verdict, the Department of Justice insisted that the New York Raul had had nothing to do with the assassination and dismissed these photographic identifications as “suspect”. It said that the photo array was “deficient and unfairly suggestive” because the Raul photograph is the only one of the six to have “extremely high black and white contrast and no intermediate gray tones” and thus “stands out markedly from the others.”37 Essentially the DOJ suggested that the contrast of that particular photo causes it to draw the eye and that was why Pepper’s witnesses picked it out. This reviewer recently decided to put that notion to the test by sharing the photo array on a social media site, asking if anyone could pick out a man named “Raoul” (Ray’s original spelling) who “has allegedly been involved in drug smuggling, gun dealing, and murder.” I also hinted at a connection to the assassination of Dr. King. Of the 14 respondents, not a single one picked out the picture of the New York Raul. While this was hardly a perfect experiment, the result nonetheless stood in stark contrast to the DOJ’s suggestion that the picture of Raul Coelho was more likely to be picked over the others because of its high contrast.

Ironically, one of the most frequently cited reasons for doubting the DOJ’s assurances and believing that the man Pepper found may well have been the real Raul is the manner in which he was assisted and protected by the US Government. As Pepper discovered after he made Raul a party defendant in the Ray v. Jowers lawsuit, despite supposedly being nothing more than a retired auto plant worker of modest means, Raul was being represented by two large, prestigious law firms. And when Portuguese journalist Barbara Reis tried to interview him, a member of Raul’s family told her that agents of the US government “are looking over us”, had visited them on at least three occasions and were monitoring their telephone calls.38 As Pepper observed, “Imagine that degree of care and consideration by the government for just a little old retired autoworker.”39

Most of the above, actually most of what is in The Plot to Kill King, will be familiar ground for those who have read Pepper’s first two books, Orders to Kill and Act of State. In fact, the first two thirds of the new book are little more than a retread of the previous two with entire passages actually being lifted word-for-word from Act of State. The final third of the book, which details Pepper’s “continuing investigation”, unfortunately does not do much to elevate matters or add to our understanding. The new information presented therein is, in this reviewer’s estimation, of very dubious reliability.

Pepper makes the absolutely startling claim that, although Dr. King’s gunshot wound would have been fatal anyway, he was intentionally finished off by the emergency room doctors who were supposed to be saving his life. He writes of a story that was related to him by a blind Memphis resident named Johnton Shelby, who claims that his mother, Lula Mae, was a surgical aide at St. Joseph’s Hospital and took part in Dr. King’s emergency treatment. According to Shelby, the morning after the assassination his mother gathered the family together to tell them that the emergency room doctors had been ordered by the head of surgery and a couple of “men in suits” to “Stop working on that nigger and let him die.” They were all then ordered to leave the room immediately. Shelby said that as his mother was leaving, she heard the men sucking saliva into their mouths and spitting so she glanced over her shoulder. She then saw that Dr. King’s breathing tube had been removed and a pillow was being placed over his face so as to suffocate him.40

An extraordinary story like Shelby’s requires extraordinary proof. Yet Pepper seems to swallow the whole thing hook, line, and sinker despite the fact that, by his own admission, he spoke with numerous medical personnel who were known to have been in the emergency room and found absolutely no corroboration for it whatsoever. Shelby named a few people with whom his mother supposedly shared her experience but, needless to say, they were all conveniently dead in 2013 when he first came forward. More importantly, in accepting Shelby’s story, Pepper has to ignore the fact that it is directly contradicted by testimony that he himself put before the jury in King v. Jowers.

At the civil trial Pepper put John Billings on the stand to testify not only about his time investigating Glenda Grabow and Raul Coelho but also about his activities on the day of the assassination. In April 1968, Billings was a junior at Memphis State University and was working as a surgical aide at St. Joseph’s. He walked into Emergency Room 1 just as Dr. King’s treatment was beginning and stood and watched as several doctors were “feverishly working … for 30, 45 minutes or so.” One of the doctors eventually walked up to Billings and told him to “go get someone in charge.” He walked out of the room and found “one or two gentleman wearing suits” who “seemed to be more or less telling everyone what to do.” He led them back into the emergency room “and the doctors informed them of something to the effect of Dr. King is – Dr. King is terminated. We have done everything that we can. We feel there’s nothing left that we can do.”41 Nowhere in Billings’ first hand account was there any reference to emergency room staff being ordered to stop working on Dr. King and leave the room. He specifically recalled that the doctors themselves made the decision to stop when they felt they had done everything they could.

At one point Pepper hints at the idea that the “connections, associations, and personal success” linked to a career practising medicine in Memphis might explain why the numerous doctors who treated Dr. King did not recall the supposed intervention. But he cannot apply any such argument to Billings who did not follow a career in medicine and worked hard as one of Pepper’s investigators to uncover details of the conspiracy to kill Dr. King. It is readily apparent that Billings had absolutely no reason to withhold any details surrounding Dr. King’s emergency treatment. Which is probably why Pepper avoids mentioning his testimony on the issue altogether.

Pepper also buys into a very elaborate yarn spun by one Ronnie Lee Adkins a.k.a. Ron Tyler. Ronnie’s father, Russell, worked for the city of Memphis for 20 years in the “Engineering Division”. Despite his modest means he was, according to Ronnie, both a 32nd Degree Mason and a Klansman who attended “meetings” that involved everyone from Mayor Henry Loeb and Memphis police and fire department director Frank Holloman to Frank Liberto, Carlos Marcello, and J. Edgar Hoover’s deputy in the FBI, Clyde Tolson. Russell was known as a “fixer” and, through Tolson, Hoover would give him money to perform various deeds including “local-area killings.” On one particular occasion in 1967, Tolson gave him money that was to be paid to the warden of Missouri State Prison to arrange for the escape of James Earl Ray. Of course, as any reasonable person would expect, Russell saw no need to shield his young son from his nefarious deeds, so little Ronnie not only got to see the money being handed to his father, he even got to go along to Missouri to see it passed on to the warden. Or so he says.

According to Ronnie, in 1964 his father went on a trip to Southampton, England, with Tolson. When he returned he called a meeting with his eldest son Russell Junior and others to tell them that “The coon has got to go.” From then on “prayer meetings” were held at the Berclair Baptist Church, among other places, which eventually came to focus on how to get the garbage workers “pissed off” as a means of drawing Dr. King to Memphis. Allegedly “the word come down from Hoover” that the assassination was to occur in Memphis so that “daddy and them could handle it.” If the reader is dubious that planning for the assassination would have begun four years before it occurred, they will be even less impressed by the claim that way back in 1956 Tolson had handed Russell a “Personal Prayer List” of his and Hoover’s featuring the names JFK, RFK and MLK. That’s right, Ronnie claims that nearly five years before the Kennedys made it to the White House, and at a time when Dr. King’s activism was just beginning, Hoover had already put their names together on a list and handed it to his Memphis “fixer” for no apparent reason.

When Russell died in 1967, Junior allegedly took over in planning the assassination alongside Holloman. Someone in their camp then supposedly engineered the deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker. For those who are unfamiliar with those names, Cole and Walker were two black sanitation workers who, on February 1, 1968, were tragically crushed to death in the back of a garbage truck where they were trying to hide from the rain. It was this tragic accident, and the paltry assistance the city gave to the families of the victims, that prompted Dr. King to travel to Memphis and join a city-wide march in support of the striking sanitation workers. But in Ronnie’s world, this was no accident, “Somebody pulled the hammer, pulled the lever on the truck and mashed them up in there.”

After Dr. King booked into the Lorraine Motel, Ronnie says, Jesse Jackson – who had supposedly been paid by Russell to keep tabs on Dr King – was instructed to have his room changed to the balcony room 306. Jackson then “went down there and talked to the man and, or his wife Lurlee … and had him move Martin and Ralph up to 306.” The Reverend Billy Kyles, another alleged informant, was given the job of getting Dr. King to come out of his room and onto the balcony at precisely 6:00 pm.

On the day of the assassination, Ronnie claims, he carried the murder weapon into town on the back of his motorbike wrapped in a bedspread and handed it to Junior and Loyd Jowers in the parking lot next to Jim’s Grill. When 6:00 pm came and Dr. King appeared on the balcony, Junior fired the shot then handed the rifle to Earl Clark who, in turn, handed it to Jowers. Junior then ran through the vacant lot between the rooming house and the fire station, climbed into the white Mustang parked outside the grill and drove away.42

The above is but a brief synopsis of Ronnie Lee Adkins’ story. There are many more details for which there is not enough space in this short essay. Nonetheless, from what I have included I believe it is clear that calling Adkins’ story hard to believe would be a vast understatement. In fact it is, in this reviewer’s opinion, so utterly lacking in credibility that it hardly seems worth wasting time on a detailed deconstruction. Not only is there no corroboration for any of it, numerous details are in direct conflict with information Pepper has previously presented. For example, Adkins has Jesse Jackson visiting the Lorraine personally to have Dr. King’s room changed. Yet, as noted earlier, Walter Bailey told Leon Cohen that he received the instruction not in person but over the phone from someone who identified himself as a member of the SCLC’s Atlanta office. Adkins has Ray leaving the scene in the white Mustang parked south of Canipe’s and his brother fleeing in the one parked outside the grill when numerous statements establish that it would have had to have been the other way around. And he has Jowers attending some of the so-called “prayer meetings” and receiving the rifle in a parking lot despite nothing like this appearing in any of Jowers’ own accounts.

In Adkins’ narrative there is no mention of or accounting for Raul and he names some extremely unlikely individuals as part of the plot. He even has MPD officer Tommy Smith – who, you might recall, testified on behalf of the King family that Charlie Stephens was too drunk to identify Ray – waiting in his car on Main Street and then dropping the bundle of evidence in the doorway of Canipe’s. Pepper himself is forced to admit how impossible this is given that “the bundle contained various bits and pieces, including the throw-down gun, which James had left on the bed in his rented room in the rooming house.”43

There are also logical problems aplenty with Adkins’ story. Like why on Earth would Hoover have had the names JFK, RFK and MLK put on a list and handed to Russell Adkins in 1956? Was anyone even referring to them by their initials back then? Once Dr. King’s assassination was decided, why did it take four years for so many presumably intelligent people to formulate a plan? How did they come to decide that “pissing off” the sanitation workers was the best way of getting Dr. King into Memphis? Why was it necessary for 16-year-old Ronnie to carry the rifle to the scene on the back of his motorbike? Who thought that was a good idea? What if he had been stopped by police officers not in on the plot? Why did Junior not just take the rifle with him in the first place? And what exactly was Earl Clark doing in the bushes if he wasn’t the shooter? Would it have been so difficult for Junior to have handed the rifle to Jowers himself? It should be noted that there is no support anywhere in the record for the notion that there were three people hiding in the shrubbery.

At the end of the day, even without these logical and factual inconsistencies, Adkins’ fantastical story is based on nothing more than the uncorroborated word of a man who, by his own account, had to quit school without graduating after he took a pistol into the lunchroom and fired off several shots.44 Accepting this man’s word without verification is, as far as this reviewer is concerned, completely unthinkable.

It is not to Pepper’s credit that he endorses the likes of Shelby and Adkins and I believe that his critics will rightly have a field day with their stories. State apologists like Gerald Posner have delighted in quoting Pepper’s former investigator Ken Herman as stating that “Pepper is the most gullible person I have ever met in my life” and the new information he presents in The Plot to Kill King is doing very little to prove this remark wrong. Unfortunately, he compounds the problem by picking and choosing what he wishes to believe of these troublesome new tales. He rejects one of the central facets of Adkins’ account – that his brother Junior fired the shot – and asserts instead that the real gunman was a former MPD officer named Frank Strausser. Yet his strongest evidence in support of this belief is that Strausser is alleged to have accidentally admitted his involvement to Nathan Whitlock.45 This is the very same Nathan Whitlock who has long claimed that Frank Liberto admitted his own involvement in the assassination to him. Which just leaves this reviewer wondering what exactly it is about Mr. Whitlock that compels people to confess their part in this crime in his presence.

Ultimately, I cannot say that The Plot to Kill King is a book I would recommend. As noted above, most of the book is a recapitulation of Pepper’s first two. Unfortunately, it is not as well written as either of his earlier works and is poorly edited to boot. There are numerous typographical errors – with Loyd Jowers and Marina Oswald being among those whose names are misspelled – as well as unnecessary repetition of information and witness statements being referred to before they’ve even been introduced. If the new information Pepper presented had been more reliable then it may have redeemed matters but unfortunately that was not to be. Pepper’s second book, Act of State, was a much more worthy addition to the literature. It was better written, better organized, and featured worthwhile rebuttals to both Posner and the Department of Justice. Readers are advised to track down a copy of that book instead.

References

1. See here for details: http://mlkmurder.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/why-did-james-earl-ray-plead-guilty.html

2. See Pepper, Orders to Kill, Chapters 24-25.

3. The 13th Juror: The Official Transcript of the Martin Luther King Assassination Conspiracy Trial, p. 752.

4. http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/Weisberg%20Subject%20Index%20Files/P%20Disk/Pepper%20William%20F%20Dr/Item%2002.pdf

5. Who Killed Martin Luther King?, History Channel documentary, 2004.

6. The 13th Juror, p. 458.

7. Pepper, The Plot to Kill King, p. 82

8. Ibid, pgs. 90-93.

9. The 13th Juror, pgs. 177-178.

10. Pepper, Act of State, p. 41.

11. The 13th Juror, p. 178.

12. Orders to Kill, p. 336.

13. United States Department of Justice Investigation of Recent Allegations Regarding the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., June 2000, Part IV, Section C.1.b. https://www.justice.gov/crt/iv-jowers-allegations#analysis

14. Orders to Kill, p. 383.

15. The Plot to Kill King, p. 154.

16. Gerald Posner, Killing the Dream, p. 291.

17. http://educationforum.ipbhost.com/index.php?showtopic=15699&p=250020

18. The 13th Juror, p. 739.

19. The Plot to Kill King, p. 171.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid. p. 298.

23. Ibid. p. 175.

24. Ibid. p. 298.

25. Ibid. p. 174.

26. Orders to Kill, p. 97.

27. The Plot to Kill King, p. 177.

28. Ibid. p. 178.

29. Ibid. p. 184.

30. Ibid. p. 198.

31. The 13th Juror, p. 343.

32. William Bradford Huie, He Slew the Dreamer, p. 177. I say “said to have remarked” because Huie, who attributed those remarks to Hanes, is a self-admitted fabricator. Therefore nothing he wrote should be taken as absolute fact without independent corroboration.

33. Posner, p. 296.

34. The 13th Juror, p. 257.

35. Ibid. pp. 270-277.

36. Act of State, p. 222.

37. Justice Dept. Report, Part VI, Section C.3.b.

38. The 13th Juror, p. 295.

39. Act of State, p. 204.

40. The Plot to Kill King, p. 261.

41. The 13th Juror, p. 249-250.

42. The Plot to Kill King, p. 238-258.

43. Ibid. p. 256.

44. Ibid. p. 239.

45. Ibid. p. 235.