View the video here.

Tag: MIDDLE EAST

-

Jefferson Morley, The Ghost: The Secret Life of CIA Spymaster James Jesus Angleton

Was there ever a person who was so hidden from public view in 1963, yet ended up being such a key character in the JFK case than James Angleton? Offhand, the only other character in the saga I can think of to rival him is David Phillips. Which puts Angleton in some rather select company. But what makes the Angelton instance even odder is that, unlike with Phillips, there have been at least three other books based upon Angleton’s career. To my knowledge there has been no biography of Phillips yet published.

The veil around Jim Angleton began to be dropped in December of 1974. At this time, CIA Director William Colby had decided that Angleton had to go. Since Angleton had been handed carte blanche powers first by CIA Director Allen Dulles, and then by Richard Helms, he was not willing to leave quietly. So Colby had to force him out. He first gave a speech about certain CIA abuses before the Council on Foreign Relations. He then directly leaked details about Angleton’s role in Operation MH Chaos to New York Times reporter Sy Hersh. MH Chaos was a massive program that spied on the political left in the United States for a number of years. Combined with the FBI’s COINTELPRO operations, they composed a lethal one two punch to dissident groups on issues like civil rights and anti-Vietnam war demonstrations.

Colby’s leaks to Hersh did the trick and Angleton was forced to resign at the end of 1974. That timing coincided with what some have called the “Season of Inquiry”. This refers to the series of investigations of the CIA, the FBI and the JFK assassination that took place after the exposures of the Watergate scandal. Specifically, these were the Rockefeller Commission, the Church Committee, and the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA). The author of the book under discussion, Jefferson Morley, goes through these to show how Angleton became a star attraction for some public inquiries. Angleton did not handle these proceedings very well, with consequences for his own reputation. As we will see, in the wake of his exposure he made one enigmatic comment that would haunt the literature on the JFK case forever.

It was these appearances that likely led to the beginning of the literature on the legendary chief of counter-intelligence. Wilderness of Mirrors was a dual biography of both Angleton and William Harvey by newspaper reporter David Martin, published in 1980. Considering the problems with classification, it was a candid and acute portrait for that time period.

Several years later, two books on Angleton were published in rapid succession. In 1991, Tom Mangold published Cold Warrior. Mangold’s book was a milestone in the field and remains a valuable contribution not just on Angleton but on CIA studies to this day. Somehow, Mangold got several Agency insiders to cooperate with him in a devastating expose of the damage Angleton had wreaked on the Agency and its allies. This was done through his almost pathological allegiance to a man named Anatoliy Golitsyn. Golitsyn was a Russian KGB operative who had been working as a vice counsel in the Helsinki embassy when he decided to defect at Christmas, 1961. He warned that any other defectors who followed would be sent by the KGB to discredit him. He prophesied about the presence of a high-level mole in the American government. He then demanded audiences with the FBI, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, the president of the United States and intelligence chiefs of foreign countries; most of which he got.

In two ways, Golitsyn’s overall concept played into the nightmare fears of Western intelligence: first, as to the existence of high-level double agents in their midst; and secondly, regarding Western leaders who were already compromised, e.g., Prime Minister Harold Wilson of the Untied Kingdom. Due to the largesse of Angleton and British MI6, Golitsyn became a millionaire. As for the accuracy of his knowledge of Soviet affairs, he said the Sino-Soviet split was a mirage, that the coming of Gorbachev was really a deception strategy to isolate the USA, and that the whole Perestroika revolution was also a KGB phantasm. He forecast the last two in his books, New Lies for Old (1984) and The Perestroika Deception (1995). Needless to add, in order to buy Golitsyn one had to accept that the rise of Gorbachev, the collapse of the USSR, and Boris Yeltsin’s use of American economic advisors to administer Milton Friedman economic “shock doctrine” to decimate the Russian economy back to conditions worse than the Great Depression—all of this was somehow a colossal KGB Potemkin Village designed to deceive the West. The question being: Into believing what? That somehow the USSR had not really collapsed? This is how ultimately bereft Golitsyn was, and this was how craven our intelligence chiefs were. They did not just believe him, they made him into a wealthy retiree. Mangold’s book revealed almost all of this. It was shocking to behold.

A year after Mangold, David Wise published his book Molehunt. The Wise book was kind of a reverse imprint of Mangold. Wise did scores of interviews with the victims of what the folie à deux of Golitsyn/Angleton had done. That is, the careers that were ruined, the reputations that were sullied, the promotions that never came. It got so bad that Congress had to pass a bill to compensate certain victims for the damage done to their careers. In 2008, author Michael Holzman wrote another biography. James Jesus Angleton, the CIA and the Craft of Intelligence was a rather sympathetic look at the man and his career. And it attempted to rehabilitate both Angleton and Golitsyn, while trying to contravene William Colby’s dictum about Angleton that, to his knowledge, he had never caught a spy.

II

Holzman’s book was published about a decade after the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB) had officially closed its doors, which makes it surprising how little information the author used concerning Angleton, the JFK case and Lee Harvey Oswald. After all, John Newman had published his milestone book on that subject, Oswald and the CIA, in 1995. He reissued that volume the same year that Holzman published his. Because he had been an intelligence analyst, Newman understood how to read and then blend together documents into a mural that made previously uncertain events understandable. He did this with the help of the releases of the ARRB.

There were two areas of Newman’s work that one would think any biographer of Angleton would find of the utmost interest. The first would be how the information on Oswald was entered into CIA files after his defection. The second would be the extraordinary work that was made possible about Oswald in Mexico City after the release of the HSCA’s legendary Lopez Report. Taking up where Holzman dropped the baton, the strength of Jefferson Morley’s book is that it does have a featured focus on this aspect: the Oswald file at CIA and its relation to Angleton. And this is the most valuable part of the book.

As Morley notes, James Angleton had suzerainty over the Oswald file at CIA for four years. (p. 86. All references are to the Kindle version) Contrary to what the late David Belin said on national television, the contents of that file were never fully revealed to the Warren Commission. And they were obfuscated for the HSCA. The file itself was personally handled by Birch O’Neal, one of the most trusted and most mysterious of the two hundred men and women who worked for Angleton in Counter Intelligence. From day one, O’Neal began to lie about what was in the Oswald file. He told the Bureau that there was nothing there that did not originate with the FBI and State Department. As Morley has noted on his website and in this book, that is simply not true. But further, the ARRB files on O’Neal have been released in heavily redacted form, and three are completely redacted.

As Morley further explains, the rule inside the Agency was that if three reports came in, a 201 file should be opened on the subject. Yet this rule was not followed with the Oswald file. This exception to protocol allowed the file to be limited in access when it was opened in December of 1959. (Morley, p. 88) It was only when Otto Otepka of the State Department sent the CIA a request on the recent wave of American defectors to the Soviet Union that a 201 file was opened on Oswald.

If the Warren Commission would actually have had full access to the file, the obvious question would have been: If Otepka had not sent the request, would a 201 file have been opened at all? Otepka’s request was about information on whether the defectors were real or ersatz. When Director of Plans Richard Bissell received it, he sent it to Angleton’s office. These circumstances strongly suggest that there was a false defector program being run by CIA, and that Angleton had a role in it.

To his credit, Morley also uses some information that was first introduced in the Lopez Report. This was the fact that there were two differing cables sent out of Angleton’s office once CIA got word of Oswald meeting with a man named Valeri Kostikov in Mexico City. One was sent to the Navy, State, and FBI. It had information about Oswald but a wrong physical description of him. The other cable was sent to Mexico City and had a correct description, but it did not include the most recent information that the CIA had on Oswald concerning his activities in New Orleans—for example, that he had been arrested, detained, tried and fined for his pro Castro activities there. (pp. 136-37) This clearly would have been important in evaluating whether or not he posed a potential threat. In other words, if Oswald had been meeting with a Russian diplomat in a nearby third country, and prior to that he had been protesting on the streets of a southern city in favor of Fidel Castro, and was trying to get an in-transit visa through Cuba to Russia, that would seem to be significant information one should pass to the FBI.

But this cable did not provide the correct description of the man. When the CIA sent up its request, it contained a picture of a man who was not Oswald. He has come to be known as the Mystery Man, although the Lopez Report identifies him as a Russian KGB agent under diplomatic cover. Consequently, that cable described Lee Oswald as a 35 year old with an athletic build and six feet tall. What makes this even more puzzling is that the CIA had accurate info on Oswald as being 24 and 5’ 9”. The other cable was sent to Mexico City and although it was allowed to be disseminated to the FBI there, it did not include the information on Oswald’s return to the USA or his New Orleans hijinks. The Warren Commission only saw one of these two cables and the HSCA only mentioned them in redacted form. (See “Two Misleading CIA Cables about Lee Harvey Oswald”)

As mentioned by the author, neither Jane Roman nor Bill Hood of the CIA could explain this paradox. (p. 137) As Morley offers: if what Oswald was doing in New Orleans—setting up an FPCC chapter with him as the only member, raising his profile via street theater— was part of an operation, then Mexico City station chief Winston Scott would not need to know about that. (p. 137)

One week before Kennedy’s murder, on November 15th, Angleton’s office received a full report from Warren DeBrueys of the New Orleans FBI office about Oswald’s activities there. As Morley writes, “If Angleton scanned the first page, he learned that Oswald had gone back to Texas after contacting the Cubans and Soviets in Mexico City. Angleton knew Oswald was in Dallas.” (p. 140) In other words, all the information that an intelligence officer needed in order to place Oswald on the Secret Service Security Index was available to Jim Angleton at that time. He did nothing with it.

III

But it is actually worse than that. As Morley notes,

Angleton always sought to give the impression that he knew very little about Oswald before November 22, 1963. … His staff had monitored Oswald’s movements for four years. As the former Marine moved from Moscow to Minsk to Fort Worth to New Orleans to Mexico City to Dallas, the Special Investigations Group received reports on him everywhere he went. (p. 140)

As Newman originally noted, Oswald’s files from Moscow and Minsk should not have gone into the Special Investigation Group (SIG). They should have gone into a file at the Soviet Russia division. (Newman, p. 27) The cumulative effect of Morley’s book is that it makes the case that the idea that Oswald was some kind of sociopath who no one knew anything about in Washington is simply not tenable today. The CIA has hidden its monitoring of Oswald for decades. And it took the JFK Act and its forcible declassification process to reveal its extent.

Morley quickly moves to some interesting developments that took place within just hours of the assassination. Oswald’s street theater antics in New Orleans now got played up in the media. Ed Butler turned over a tape of Oswald defending the FPCC on a local radio station. The CIA-backed Cuban exile organization, the DRE, were calling reporters to inform them of Oswald’s FPCC activities in the Crescent City. They even published a broadsheet saying Oswald and Castro were the presumed killers of Kennedy. (Morley, p. 145) Of course, Butler and the DRE’s intelligence connections were not exposed at this time, nor did the Warren Commission explore them. To accompany this there is a mysterious message that Richard Helms’ assistant Tom Karamessines wrote to Winston Scott in Mexico City. He told the station chief not to take any action that “could prejudice Cuban responsibility.” (Morley, p. 146)

Morley has an interesting observation about Kostikov and AM/LASH. Hoover asked Angleton in May of 1963 if Kostikov was part of Department 13, responsible for terrorist activities and murders in the Western Hemisphere. The reply was negative. (Morley, p. 149) Yet this would change six months later. (Newman, p. 419) It would change again, when Angleton testified to the Church Committee. There he said he was not sure. But Morley further reveals that Rolando Cubela, a prospective assassin tasked by the CIA to kill Castro, was also in touch with Kostikov. This was done through Des Fitzgerald who was in charge of Cuban operations in 1963. Fitzgerald probably thought that Cubela may have told Kostikov about the CIA using him. Kostikov then told the Cubans, and Castro may have decided to strike first, using Oswald as a pawn. This may be why Fitzgerald wept when Jack Ruby shot Oswald on television. He reportedly said, “Now, we’ll never know.” (Morley, p. 150)

The first liaison between the CIA and the Warren Commission was a man named John Whitten. But he was rather quickly moved out by Richard Helms and replaced with Angleton. The CIA now adapted a stance of waiting out the Commission. (p. 155) Here, Morley passed up a fine way to exemplify this fact. When Commission lawyer Burt Griffin testified before the HSCA, he revealed that he had sent a request to CIA to send him all the files they had on Jack Ruby and several related persons, like Barney Baker. Two months later, in May of 1964, they still had no reply. So they sent a reminder. They finally got their negative reply in mid-September, when the Commission volumes were in galley proofs. (HSCA Volume XI, p. 286) You can’t wait out a committee any better (or worse) than that can you?

Continuing with the JFK case, Morley makes a brief mention of the formation of the CIA’s Garrison Group. (p. 192) And he also adds that one of Angleton’s assistants, Raymond Rocca, was a key member. Rocca proclaimed at its first meeting that it appeared that Jim Garrison would be able to convict his indicted suspect Clay Shaw. I wish Morley had made more of this body, because as is evidenced from the declassified files of the ARRB, the CIA itself began to take offensive measures against Garrison at around this time. The convening of this intra-agency group was ordered by Richard Helms. Helms wanted the group to consider the possible implications of the Garrison case before, during, and after the trial of Clay Shaw. (James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed, Second Edition, p. 270) Which they did. For instance, Angleton ran name traces on the possible jurors in the Shaw trial. (p. 293)

As Morley noted in his previous book, Our Man in Mexico, when Winston Scott passed away in 1971, Angleton immediately hightailed it to Mexico City to confront the widow of the CIA station chief. (Morley, p. 213) By using some not so subtle threats about Scott’s death benefits, he essentially emptied the contents of Scott’s safe, which amounted to 3 large cartons and 4 suitcases full of materials. This included a manuscript Scott was laboring on at the time of his death. By all indications, this cache included at least one tape of Oswald in Mexico City.

The last time Angleton’s proximity to the JFK case came up was near the end of his career. Senator Howard Baker had been on Sam Ervin’s committee investigating Watergate. His minority counsel, Fred Thompson, had uncovered a lot of material about the CIA’s hidden role in that scandal. (See Thompson’s book, At That Point in Time.) This, along with the exposure of MH Chaos in the New York Times, provided much of the impetus for first the Rockefeller Commission, then the Senate Church Committee, and the Pike Committee in the House of Representatives.

Morley leaves an important point out when he introduces this crucial historical episode, about which there are still documents being withheld from the public. As Daniel Schorr noted, at a closed press briefing in Washington, President Ford was asked why he had stacked the Rockefeller Commission with such conservative stalwarts—e.g., General Lyman Lemnitzer and Governor Ronald Reagan—and appointed Warren Commission lawyer David Belin as chief counsel. Ford replied that there might be some dangerous discoveries ahead. Someone asked him, “Like what?” Ford blurted out, “Like assassinations!” There was no discussion of what assassinations were referred to. However, since the NY Times article was about domestic CIA spying, and both Ford and Belin served on the Warren Commission, Schorr assumed it was about domestic assassinations. But when Schorr went to Bill Colby at CIA, the director did a beautiful bit of ballet on the issue, one that has never been properly appreciated. He told Schorr that Ford must have been talking about foreign plots. (The Assassinations, edited by James DiEugenio and Lisa Pease, p. 194)

This was a masterful stroke by Colby. It was now the CIA plots against Patrice Lumumba, Rafael Trujillo, Achmed Sukarno, and first and foremost Fidel Castro, which took center stage. Because many felt the Rockefeller Commission would be a fig leaf, it was superseded by Senator Frank Church’s and Congressman Otis Pike’s now near-legendary efforts. (For anyone interested in reading up on this fascinating subject, this reviewer recommends Schorr’s Clearing the Air. Schorr ended up being fired by CBS due to the influence of then CIA Director George H. W. Bush.)

As Morley notes, Angleton made some rather startling comments both in the witness chair and to reporters outside. Some of them follow:

- “It is inconceivable that a secret intelligence arm of the government has to comply with all the overt orders of government.”

- “When I look at the map today and the weakness of this country, that is what shocks me.”

- “Certain individual rights have to be sacrificed for the national security.” (All quotations from p. 254)

And, as alluded to above, there was the granddaddy of all Angleton quotes. In reply to a query about the JFK case, Angleton said, “A mansion has many rooms, I was not privy to who struck John.” (p. 249) That particular quote has sent many writers scurrying to understand what on earth Angleton meant by it. Perhaps the best effort in that regard was by Lisa Pease in her two-part essay on the spy chief. Her work benefits from the use of an episode that, for whatever reason, Morley ignored. This was the legal dispute between a periodical called The Spotlight and Howard Hunt, which was chronicled in Mark Lane’s book Plausible Denial. As Pease notes, Angleton did all he could to dodge questions about this incriminating episode. It originated over an article in Spotlight about a memo to Richard Helms. Angleton’s memo stated that they had to create an alibi for Howard Hunt being in Dallas on the day of the assassination. (Lane, p. 145)

Hunt denied that any such thing happened. And he won a lawsuit against Spotlight. But on appeal, that decision was reversed. In his book, Lane shows that, in fact, the CIA had tried to help Hunt in constructing his alibi. And contrary to skeptics, it turned out that Angleton himself had actually shown the memo to journalist Joe Trento. (DiEugenio and Pease, p. 195) What is remarkable about this is that the Trento meeting happened in 1978, while the HSCA was ongoing. And Angleton had called Trento to specifically show him the document. As Lisa Pease wrote, the HSCA—through researcher Betsy Wolf—was closing in on Angleton’s association with Oswald through CI/SIG. In her opinion, this memo was meant to send a warning shot across the bow of his cohorts: If I go down, you are coming with me.

IV

To his credit, Morley spends quite a few pages on Angleton’s governance of the Israeli desk at CIA. There is little doubt that Angleton was a staunch Zionist who was not at all objective about the Arab-Israeli dispute. (Morley, p. 74) For instance, Angleton did not disseminate the information on the suspected construction of the Israeli atomic reactor at Dimona for U2 over-flights. (p. 92) Angleton leaned even further toward Israel because he suspected a growing alliance between Cairo and Moscow. Morley concluded this section with a good summary of how the Israelis betrayed America by stealing highly enriched uranium for their first bombs from a nuclear plant they purchased as a front near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. (See “How Israel Stole the Bomb”)

My complaint about this section is that Morley does not sketch in how Angleton’s near rabid devotion to Israel was in opposition to President Kennedy’s policy in the Middle East. There were two specific aspects he could have highlighted in this regard. First, once he became president, JFK did all he could to forge an alliance with Gamel Abdel Nasser of Egypt in order to reach out to the moderate Arab states. (Philip Muelhenbeck, Betting on the Africans, pp. 125-27) And he was doing this simply because he felt that what Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and President Eisenhower had done previously—asking Nasser to join the Baghdad Pact, and cutting off funds for the Aswan Dam—had helped usher Nasser into a relationship with Moscow. An extreme cold warrior like Angleton would not appreciate this kind of diplomatic strophe. The other point that is missing here is that, as Roger Mattson noted in his book Stealing the Atom Bomb, Kennedy was adamant about there being no atomic weapons in the Middle East. (Mattson, pp. 38-40, 256) This was an integral part of his overall policy there in which he tried to be fair and objective to both sides. It would thus appear that Angleton and Kennedy held differing views on this issue. And after Kennedy’s murder, Angleton’s views won out first under President Johnson and then further with Nixon.

That point branches off into President Kennedy’s foreign policy toward Cuba and the USSR at the time of his death. Morley does some work on Angleton’s influence on Cuba policy as late as May of 1963. But he does not sketch in Kennedy’s policy shift toward Castro that came after the Missile Crisis; nor his attempt at a rapprochement with Khrushchev at that time. Today, all of this seems important in light of the attempts by certain suspect characters—some he has mentioned—to blame the assassination on either Cuba or Russia.

Also relevant in this regard is the production of the Edward Epstein authored book Legend: The Secret World of Lee Harvey Oswald, which Morley deals with rather lightly. That book had one of the largest advances for any book ever in the JFK field. Today, in inflation-adjusted dollars, it would be well over a million, closer to two million. According to more than one source, including Carl Oglesby and Jerry Policoff, Angleton was a chief consultant on that project. Released during the proceedings of the HSCA, Epstein ignored all the evidence that showed Oswald was some kind of American intelligence operative. Instead, the book did all it could to insinuate that Oswald was really some kind of Russian agent, perhaps controlled by George DeMohrenschildt, and that Oswald did what he did for either the KGB or Cuban G-2. As Jim Marrs later discovered, Epstein employed a team of researchers. They were instructed to only look at any possible communist associations they could find. As Lisa Pease later discovered, in Epstein’s first edition of his previous book on the JFK case, Inquest, he acknowledged a Mr. R. Rocca, Who she suspected to be Ray Rocca, one of Angleton’s important assistants specializing on the JFK case.

To me, this area would seem at least as interesting and important as Mary Meyer, which Morley spends about ten pages on. To put it mildly, after doing a lot of research on this issue, I disagree with just about every tenet of his discussion of the matter. And I was more than a bit surprised when Morley even brought in the Tim Leary aspect of this mythology. As I showed, Leary manufactured his relationship with Meyer after the fact in order to sell his book Flashbacks. And if one reads the current scholarship on Kennedy’s foreign policy by authors like Phil Muehlenbeck and Robert Rakove, the idea that Kennedy needed Meyer to advise him on this is risible. (See my review of Mary’s Mosaic for the details)

Also disturbing in this respect is his use of Mimi Alford and her ludicrous, “Better red than dead” quote she attributed to JFK during the Missile Crisis. Greg Parker did a very nice exposé of Alford and the man who first surfaced her, Robert Dallek, back in 2012 that unfortunately is not online today. It showed just how dubious she was. But suffice it to say, anyone who reads, for example, The Armageddon Letters—the direct communications between the three leaders—can see how fast and hard Kennedy drew the line. (See the letter on pp. 72-73) The missiles, the bombers and submarines were all leaving and they would be checked as they left. In fact, as Parker pointed out, Kennedy had criticized the “better Red than dead school” less than a year before the crisis during a speech at the University of Washington. But he also criticized those who refuse to negotiate. Kennedy was not going to let the atomic armada stay in Cuba for one simple reason: he suspected that the Russians had done this to barter an exchange for West Berlin. Kennedy resisted that because he saw it as unraveling the Atlantic Alliance. Anyone who has read, for example, The Kennedy Tapes, will understand that. (See, for example, p. 518, where Kennedy himself makes the association.) What Kennedy conceded ultimately was very little, if anything. He made a pledge not to invade Cuba, which he was not going to do anyway; and he silently pulled missiles out of Turkey, which he thought were gone already. They were supposed to have been replaced by Polaris missiles, which they later were. So in his actions here, unlike with the Mimi Alford mythology, Kennedy simply lived up to his 1961 speech. Either Morley has little interest in Kennedy’s foreign policy or he has little knowledge of it.

The strength of the book lies in the tracing of the Oswald files through the CIA under Angleton’s dominion. No book on Angleton has done this before. And that is certainly a commendable achievement. Hopefully, this will become a staple of future Angleton scholarship, which I think the book is designed to do.

-

Jim DiEugenio at the VMI Seminar

Alan Dale:

He’s one of the most knowledgeable and tenacious researchers and writers on the political assassinations of the 1960s. He’s the author of 1992’s Destiny Betrayed, which details the New Orleans district attorney, Jim Garrison’s, investigation in the trial of Clay Shaw, which was greatly expanded for a revised edition issued in 2012. Also, Reclaiming Parkland, published in 2013, but reissued and expanded in 2016. He’s also the co-author and editor of The Assassinations: Probe magazine on JFK, MLK, RFK, and Malcolm X. He co-edited the acclaimed Probe Magazine from 1993 until 2000, and was a guest commentator on the anniversary issue of the film JFK, re-released by Warner Brothers in 2013. His website, kennedysandking.com, is one of the best and most reliable online resources for students and scholars of American political assassinations of the 60s. Please welcome Jim DiEugenio.

Jim DiEugenio:

First of all, I’d like to thank Lee Shepherd for doing this. These things are never easy to put together. And I’d like to be gracious about sharing the program with two great guys like Bill Davy and John Newman, who I’ve both known for about 25 years. I’ve worked with them for about that long also, and their books, in my opinion, would rank in any top 15 listing of the best of the JFK Library. Considering there’s 1,000 books in that library, that’s saying something.

I want to introduce what I’m going to talk about tonight by stating that my last book, Reclaiming Parkland, largely about the state of the evidence, as it was in 2013 in the JFK case, is what we call in the trade, something called a micro-study. As one reviewer said, it was really a kind of an updating of Sylvia Meagher’s classic book, Accessories After the Fact, which I thought was a very kind complement indeed.

After publishing that book, I came to the conclusion, after months on end of study of all the detailed evidence, like the bullet shells, CE399, the medical evidence, etc., that there really was no case against Oswald today, that Oswald was not the victim of a miscarriage of justice. The simple problem was that there was no justice at all. You had a rogue prosecution, led by the FBI, and the Warren Commission acted essentially as a kangaroo court. But once that evidence presented was minutely examined, the case against Oswald simply did not exist. They were allowed to get away with this because, of course, Oswald had no legal defense and there were no legal restrictions to protect his rights. After going through all this, I have no problem today saying that, to say Oswald was guilty is the legal and moral equivalent of being a Holocaust denier.

So after I disposed of that, I began to concentrate more on why was Kennedy assassinated. And I began to look more and more at Kennedy’s foreign policy. And the more I looked, the more I began to search outside of the JFK Library of books, simply because if you stay aligned with that particular lexicon, you’re probably going get like 90% Cuba/Vietnam, as if this was all Kennedy did for three years. And I found out that really was not the case, not by a long shot.

And I also discovered something else. As much as I liked Jim Douglass’ book, JFK and the Unspeakable—and I would recommend that book to anybody who hasn’t read it—I disagree with the sales slogan that was used to sell the book. This was something like “A Cold Warrior Turns”, meaning that after 1962 and the missile crisis, that JFK stopped being a cold warrior and tried to work with Khrushchev and Castro for detente.

The way I looked at this, and the discoveries I was making, is that Kennedy’s foreign policy was pretty much set once he entered the White House. There’s three key events that we have to question in order to understand who Kennedy was, once he entered the White House. These are number 1) Why did Kennedy not send in the Navy to bail out the Bay of Pigs invasion? That would’ve been easy enough. Arleigh Burke, the admiral, was there trying to get him to do that the first night of the invasion.

2.) Why, in the fall of 1961, did Kennedy not send combat troops into South Vietnam? And, by the way, I have to say, in reading Gordon Goldstein’s book, Lessons in Disaster, which is a biography of McGeorge Bundy, that culminating debate in November of 1961 was preceded by eight previous requests for JFK to send troops into Vietnam. So this is nine times in that one year that Kennedy was determined to turn down sending the military into Vietnam.

And the third question is: Why did Kennedy not bomb the missile silos during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962? Again, almost everybody in the room was asking him to take some kind of military action. And by the end of the 13 days, even McNamara, who had proposed the blockade in the first place, was leaning in that direction. But Kennedy didn’t do it. He stuck with his back channel between RFK and the Russian ambassador in Washington.

So my question is, all these books mention them, but nobody tries to explain why he did not do those things. And if Kennedy was really a Cold Warrior, he would have done all three of those things, or at least two out of the three. For instance, we know that LBJ wanted to send troops into Vietnam in 1961. In fact, we have him on tape in 1964, telling McNamara how frustrated he was, watching McNamara and Kennedy arrange this withdrawal plan. We know that Nixon would have sent in the Navy at the Bay of Pigs, because that’s what he told Kennedy to do. When Kennedy called him, either the second or third night of the crisis, he asked him “What should I do?” Nixon said “declare a beachhead and send in the Navy”, but he didn’t do that. He was willing to accept defeat in April of 1961, at the Bay of Pigs, and he was willing to withdraw, leading to an inevitable defeat, in Vietnam. So the question is: Why?

And so, I began to study this phenomenon and I began to consult books outside the Kennedy assassination lexicon and I discovered that the key to understanding this is a man who’s name was in no book up until Jim Douglass’ book. His name’s not mentioned anywhere that I could find, and his name is Edmund Gullion. Gullion worked in the State Department when Kennedy was a congressman and that’s when they first met. Kennedy needed some advice on a speech, so he went over to the State Department and Gullion gave him a consultation. In 1951, Gullion, because he spoke fluent French, had been transferred to South Vietnam.

In that same year, Kennedy was preparing to run against Henry Cabot Lodge for the senatorial seat from his home state of Massachusetts. So he flies into Saigon, because he wants to become more well versed in foreign policy, which is what senators spent a lot of their time on. He decides to ditch the French emissaries that had been sent to meet him at the airport, and he starts knocking on doors of people who have good reputations in the media, there were a couple back then, and in the State Department. One of the guys he meets with is Edmund Gullion.

So they have dinner at a roof top restaurant in Saigon, and Kennedy asks him flat out: We’re allied with the French in this thing, we’re actually bankrolling this effort, are the French going to win? Gullion says something like: There is no way in Hades that France is going win this war. Kennedy, of course, asks him: Well, how come? And he says: It’s rather simple. Ho Chi Minh has fired up the general population, to a point that you’ve got tens of thousands of these young Viet Minh who’d rather die than go back under the yoke of colonialism. France will never win a long, drawn out, prolonged, bloody war of attrition, because the home front simply will not accept it. And that’s how it’s going to end.

To say that conversation had a rather deep impact on JFK is a large understatement. When he got back to Massachusetts, he began writing letters, making speeches and doing radio addresses; criticizing both the Republican foreign policy establishment and the Democratic foreign policy establishment and, most of all, the State Department for not understanding the real plight of colonized people in the Third World. In his new way of thinking, this was not a battle between Communism and Capitalism, but it was one between independence and colonialism. And colonialism, according to Kennedy, was going to lose.

Allen & John Foster Dulles This manifests itself, on a national level, in 1954 during Operation Vulture. Vulture was John Foster Dulles—the Secretary of State at that time—it was his plan to bail out the doomed French effort in Vietnam. This was a huge air armada of about 210 planes, 3 of them were carrying atomic bombs, and this was going to bail out the French effort at the battle of Dien Bien Phu. Well, Nixon, who is the Vice President at that time, is the liaison between Congress and the White House on this whole issue. Kennedy gets wind of this, of what’s going to happen, and he begins to rail against Dulles and Eisenhower. He wants them to come down here and explain to us how nuclear weapons are going win a guerrilla war. And he then added, no amount of weaponry could defeat an enemy which was everywhere and nowhere, and had the support of the people.

And by the way, that’s a very important passage there, because one of the things historians are supposed to do is to find origins and patterns in a man’s foreign policy. And that phrase that he said, about being everywhere and nowhere and having the people’s support, that’s the argument he’s going to use in 1961; when everybody wanted to commit troops to Vietnam. Nobody had an answer to it then. I call that Kennedy’s first defining moment; his first face off against the Dulles brothers, Nixon and Eisenhower.

Three years later, there’s another one, except it’s much more public. The second one is in 1957, when Kennedy takes the floor of the Senate and he begins to attack, very specifically, Dulles, Nixon and Eisenhower again. This time it’s over their continued alliance with French colonialism, except this time it’s off the north coast of Africa, in Algeria, where France is now involved in another civil war to maintain the French colony of Algeria. Five hundred thousand troops devolved into a war of horrible atrocities. Kennedy attacked the White House again for allying itself with the hopeless struggle of a European country to maintain an overseas empire in the Third World. And he predicted that this would turn out just like what happened three years previous in Vietnam, with another French defeat. What we needed to do, he said, was to convince Paris to negotiate, in order not to destroy the country of France in a futile war against brother and sister over this horrible dispute in Algeria. But, as important, if not more important, we had to begin to free the colonized nations of Africa.

That was his second defining moment. And what was surprising about this speech, and by the way, I would say that speech is very much worth reading, even today. It’s an incredible speech for a young man to be making on the floor of the Senate, considering the makeup of the Senate and the White House at that time.

This time, Kennedy was attacked, not just by Nixon and John Foster Dulles. But by people in his own party, like Dean Acheson and Adlai Stevenson. It was a very controversial speech. It made headlines in a lot of newspapers. There were 163 editorial comments. Over two thirds of them were negative. Kennedy really thought that he made a mistake and he called up his father and asked him what he thought. His father said he hadn’t made a mistake: You watch what’s going to happen. This situation in Algeria is going to get even worse. In two years, everybody will realize that you were right. And by the way, that’s exactly what happened. Eric Sevareid made an editorial comment on CBS TV in 1959, saying: Well, John Kennedy looks like a prophet these days, doesn’t he?

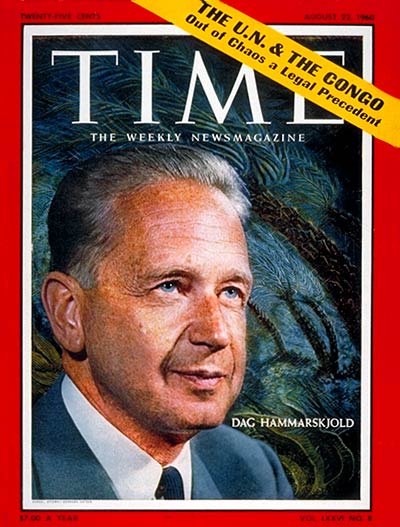

Dag Hammarskjöld But that Algeria speech actually did something else. It made him a hero to the colonized people of Africa. He now became a kind of unofficial ambassador to visiting African dignitaries. And that appeal began to spread to other Third World areas. So Kennedy now became a great admirer of the Chairman of the UN, Dag Hammarskjöld, who wanted the United Nations to be a kind of international forum that would give voice to the powerless nations coming out of colonialism and provide a lectern to express themselves. They began to make a secret alliance over the areas of Indonesia and Africa.

By 1960, Kennedy is very conscious that he’s on the edge with his foreign policy. So, on the eve of the 1960 convention, he told one of his advisors, Harris Wofford: We have to win this thing. Because if Johnson wins or Symington wins, its just going to be more of John Foster Dulles all over again. And, by the way, I have to say that, with what LBJ did once Kennedy took over, from ’64 to ’68, I think Kennedy was actually right about that.

Kennedy addresses

the U.N. General AssemblyOnce Kennedy is in office, he immediately begins to alter the Dulles brothers’ policies. For example, in the Congo, where he supported Hammarskjöld’s policy to stop the country from being partitioned or recolonized by Belgium. And he began to work with Hammarskjöld, reversing American policy in Indonesia. The Dulles brothers had tried to overthrow Sukarno the Nationalist leader of Indonesia in 1958 and 59. Kennedy decided that that was going to be reversed. That he was going to support Sukarno, both politically and economically.

Kennedy & Sukarno Now what’s really remarkable about just those two instances, those alterations of the Dulles brothers’ foreign policy is this: That Kennedy continued those two policies after Hammarskjöld was murdered in the fall of 1961. And, by the way, I have no problem using the word “murdered”. Because all you have to do is read Susan Williams’ book, “Who Killed Dag Hammarskjöld?” You will see that that was not an accident, that airplane crash was not an accident. In other words, with Hammarskjöld dead, Kennedy was carrying this burden by himself. And, in fact, he had to go to New York to convince the United Nations, after Hammarskjöld’s death, not to give up their mission in Congo. He actually did that twice. And then he planned a State visit to Indonesia in the summer of 1964, which Sukarno was very much looking forward to.

Now I can mention other places where this occurs, that is when Kennedy comes in, he reverses the Dulles/Eisenhower foreign policy. For example, he wanted a negotiated settlement in Laos. Very important and, again, very overlooked, is that in the Middle East, the Dulles brothers had isolated Nasser and were beginning to favor Saudi Arabia.

Lee Shepherd:

Nasser, the head of Egypt.

Jim DiEugenio:

Gamal Abdel Nasser Yes, Nasser was the president of Egypt. And Kennedy reversed that, also. He began to favor Nasser and isolating Saudi Arabia. Now the reason he did that was because he thought, because Nasser was a Socialist and a secularist, that he could begin to mold the foreign policy in the Middle East away from the fundamentalism and the monarchy of places like Saudi Arabia and Iran.

And, by the way, he even mentioned that issue in 1957. Because there was a big Moslem population in Algeria. He refused to meet with David Rockefeller because he did not want to initiate a coup in Brazil, which is what Rockefeller wanted to meet him about, and he moved to isolate the military regime that had deposed the Dominican Republic’s President Juan Bosch.

Now every one of those policies, without exception, began to change at a slow rate and then at a rapid rate, under the pressure of Johnson and the CIA, in a period of about 18 months after Kennedy is assassinated. In each case, the end result was a calamity for the people living in those areas. A very good example being the CIA sponsored coup in Indonesia that took place in 1965 and which killed well over 500,000 citizens; and led to the looting of the nation by Suharto and his corporate cronies. What Kennedy wanted to do there, he was actually arranging deals for Sukarno to nationalize the industries on a very good split, the majority of the profits going to Indonesia. And Sukarno was going to use that money to start doing things like building hospitals and an infrastructure and schools, etc. He wanted those benefits of those natural resources to go to the people.

Now let me conclude with, what I think, is a very important aspect of this whole Dulles vs. Kennedy foreign policy dispute. As most people understand today, Kennedy was never going to commit the military into Vietnam. In fact, he was withdrawing the advisory force from that area at the time of his assassination. The Assassinations Records Review Board released some really important documents on this in 1997 and that, in addition to several books, including John’s book, JFK and Vietnam, for me sealed the deal on that issue.

Truman reacts to the assassination Within a month of Kennedy’s assassination, I think on December 20th, 1963, former president Harry Truman published a column in the Washington Post, in which he assailed how the CIA had strayed so far from the mission he had envisioned for them when he was putting that agency together. To the point where he really kind of didn’t recognize what it had become. From his notes, it’s clear that Truman began writing that column eight days after Kennedy’s death.

“Harry Truman Writes” In the spring of 1964, while he was sitting on the Warren Commission, Allen Dulles visited Truman at his home in Missouri. This was not a social visit. He was there for one reason. He wanted Truman to retract the column. That attempt by Dulles failed. Truman never did retract what he wrote and, in fact, about a year later, in Look magazine, he repeated those same thoughts.

But a very curious exchange occurred as Dulles was leaving. As he got to the door to join his waiting escorts, he turned to Truman and said words to the effect: You know, Kennedy denied those stories about how the CIA was clashing with him in Vietnam. Which is a really startling thing to say. Because Dulles’ visit was supposed to be about Truman’s article. And Truman never mentioned Kennedy or Vietnam in the article.

Further, the two newspaper pieces Dulles referred to are likely one by Arthur Krock and one by Richard Starnes, both published in October of 1963. They both discussed the CIA’s growing influence over foreign policy and they both conclude that, if there was ever an overthrow of the US government, unlike Seven Days in May, the novel that had been made into a film around that time, it would be sponsored by the Agency and not the Pentagon. Again, Truman never went that far in his article. This whole angle was imputed to him and initiated by Allen Dulles. I think it’s pretty clear, from that conversation, that Dulles made the visit because he thought Truman wrote the column because the former president believed the CIA had a role in killing Kennedy over the Vietnam issue.

What makes this even more remarkable are these two aspects. Number one, at that time, in the spring of 1964, nobody had connected those dots: That is, the CIA, Kennedy, Vietnam and Kennedy’s assassination. No one. The first time it’s going be done is four years later by Jim Garrison.

Number two, Truman had already said to the press in 1961 that Hammarskjöld had been murdered over his Congo policy. And Dulles was aware of that. In my opinion, he saw what had happened with Hammarskjöld, and he did not want Truman to get more explicit in the Kennedy case. So in the language of prosecutors, specifically the late Vincent Bugliosi, he would have said something like this—if he had been on our side: What Dulles was doing here was showing something called consciousness of guilt, while he was sitting on the Warren Commission. Which is one more reason that the commission is really a joke.

After four years of study, 2013 to 2017, I’ve concluded that the cover up about Kennedy’s foreign policy, and how reformist it was, has been more deliberate, more strenuous, more systematic, than the cover up about the circumstances of his death. The reason being that it gives a clear and understandable motive for the Power Elite to hatch a plot against him. There were literally tens of billions of dollars on the table in the Third World, especially Indonesia. And that’s the kind of money that these people commit very serious crimes about.

This is why, at the time of his death, people like Nasser in Egypt fell into a month long depression. And he ordered Kennedy’s funeral to be shown four times on national television. It’s why Sukarno openly wept and asked “Why did they kill Kennedy?” It’s why Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, when the American Ambassador gave him a copy of the Warren report, he returned it to him. He pointed out the name of Allen Dulles on the title page and said one word: “Whitewash.” The people about to be victimized understood what had happened. Because of our lousy media in the United States, it’s taken the American public quite a bit longer to understand.

Okay, thank you, I’ll conclude with that.

Lee Shepherd:

James, can I ask you one question.

Jim DiEugenio:

Sure.

Lee Shepherd:

You’re mentioning Dulles quite a bit.

Jim DiEugenio:

Right.

Lee Shepherd:

Who do you think is behind this whole thing?

Jim DiEugenio:

Well, I gave David Talbot’s book a very good review: The Devil’s Chessboard. And I think he makes a pretty good case, that Dulles, if I had to categorize it, I think Dulles was the outside guy and I think James Angleton was the inside guy.

Lee Shepherd:

So the assignment was given to Angleton?

Jim DiEugenio:

I think Angleton was the inside guy.

Lee Shepherd:

Okay.

Jim DiEugenio:

He was the guy working in the, what we would call, the infrastructure. And I think Dulles was the outside guy, arranging it with the people he knew had to back him.

Lee Shepherd:

But Dulles was fired.

Jim DiEugenio:

Dulles was what?

Lee Shepherd:

Dulles was fired by that stage, by John Kennedy.

Jim DiEugenio:

Yeah, he was fired. But if you read Talbot’s book, he was only fired symbolically. Because he kept on having meetings over at his townhouse in Georgetown. And he actually wrote about those meetings in his diary and anybody could read who he was meeting with, people like Angleton, people like Des FitzGerald, etc. And then on the day of the assassination, he ends up at the Farm,—

Lee Shepherd:

Yes.

Jim DiEugenio:

—which is the CIA headquarters.

Lee Shepherd:

Is that Camp Parry? Camp Parry, Virginia?

Jim DiEugenio:

Yes.

Lee Shepherd:

Secondary command post of the CIA?

Jim DiEugenio:

Right.

Lee Shepherd:

Okay, good, thank you.

Jim DiEugenio:

So he was figuratively separated from the CIA. But as Talbot says in his book, he was really more like leading a kind of like in-country junta against Kennedy.

Lee Shepherd:

Okay, James. Thank you so much.

This transcript was edited for grammar and flow.

-

Hillary Clinton vs JFK: An Addendum

Dr. Jeffrey Sachs has once again written a generally sound piece of criticism on this issue. And once again, he is to be saluted for it. It is indeed encouraging that he gets such pieces into the new MSM, represented by The Huffington Post.

But even if this editorial is actually better than the first, it still seemed to me fitting to remind our readers of what I originally posted back in November, when “Hillary Clinton and the ISIS mess” appeared. So CTKA has decided to repost it.

Like his book on Kennedy’s sponsorship of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban, it does not go quite far enough. (See our review)

He is correct about the CIA beginning its sponsorship of the mujahedeen in 1979 to battle the Soviets in Afghanistan. But he fails to add that one of the Moslem volunteers who went to Afghanistan to fight the Russians was Osama Bin Laden. And most commentators trace the beginning of the Al Qaeda movement from Bin Laden’s experience there. (See the sterling documentary on this subject, The Power of Nightmares.)

But beyond that, 1979 was the year of the first explosion of Islamic fundamentalism in the Middle East. It took place in Iran. It was fueled by the brutal regime the CIA and Allen Dulles installed there when they overthrew the nationalist leader Mossadegh. Every American president — save one — coddled up to the Shah of Iran. All the way until the Islamic Revolution.

The man who paved the way for Sharia Law to take hold in Iran was none other than Warren Commissioner John McCloy. As Kai Bird noes in his book, The Chairman, President Jimmy Carter resisted letting the Shah into the country for medical purposes. When he did, David Rockefeller started a lobbying campaign, which was spearheaded by attorney John McCloy. McCloy knew he could not convert Carter. So, one by one, he picked off his advisors. Until finally, Carter was alone and cornered. But before he caved, he turned and asked: I wonder what you guys are going to advise me to do if they invade our embassy and take our employees hostage?

Therefore, it was McCloy who directly caused the Islamic Revolution to begin in the Middle East. And it was he who greatly influenced the coming to power of Ronald Reagan.

As noted above, there was one president who did not toady up to the Shah. As James Bill chronicles in his book, The Eagle and the Lion, the Kennedy administration actually commissioned a State Department paper on the costs and liabilities of returning Mossadegh to power in Iran. The Shah took this seriously and started the White Revolution in order to make his administration more progressive and egalitarian. Once Kennedy died, this did not continue. President Johnson was quite friendly with the Rockefeller brothers, and Henry Kissinger, Richard Nixon’s National Security Adviser, owed his career to Nelson Rockefeller. Unlike these other presidents, Kennedy understood the dangers of an explosion of Islamic Fundamentalism. In fact, he had warned about it since 1957, and his famous speech encouraging the French to abandon their colonial empire in Algeria.

But there was one other element to this story of Carter changing his mind. During the revolution, before Carter allowed the Shah entry, he was in Los Angeles for a speaking engagement. Both the Secret Service and LAPD detected an assassination plot against him. One of the alleged plotters’ was named Raymond Lee Harvey. Raymond said an accomplice was named Osvaldo Espinoza Ortiz. No one as smart as Carter could have missed the significance of that. (See this Wikipedia article)

There is another point about the Sachs’ article and the Clinton agenda that needs to be elucidated. That is America’s growing coziness with Saudi Arabia. As scholar Philip Muehlenbeck noted, President Kennedy had little time or use for the monarchy of Saudi Arabia. He disdained its disregard of civil liberties, democracy and women’s rights. When King Saud flew to a Boston area hospital in 1961, Kennedy was urged to visit him by his State Department advisors. Not only did he not visit him, he avoided going to Boston and instead went to his vacation home in Palm Beach Florida. When the monarch was released and went to a convalescent home nearby, Kennedy finally relented. But on the way there, he muttered: Why am I seeing this guy? (Muehlenbeck, Betting on the Africans, p. 133)

Kennedy favored the country that DCI Allen Dulles and his brother, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, decided to abandon – Egypt – because its socialist leader, Nasser, would not toe the line on Red China during the Cold War. During the civil war in Yemen, where Saud backed the monarchy and Nasser backed the revolutionaries, Kennedy decided to back Nasser, at great political expense to himself — including the enmity of Israel’s foreign secretary Golda Meir. (See Muehlenbeck, pp. 132-37)

When John Kennedy was killed two things happened in the Middle East to create the mess that exists today. First, there was a tilt away from Egypt and pan Arabism; second, a bias toward Saudi Arabia and Israel began. As Stanford professor Robert Rakove notes in Kennedy, Johnson and the Nonaligned World, Nasser immediately understood what was happening. On November 23, 1963, Nasser declared a state of mourning. He then ordered Kennedy’s funeral to be shown on Egyptian television four times. One diplomat said Cairo was “overcome by a sense of universal tragedy.” Nasser eventually broke relations with the USA in 1967. (Rakove, pp. xvii ff)

Although Sachs’ article is good, the record of John Kennedy is even better. And, in fact, a piece like this one would probably not get past the moderators, especially in light of their decision to publish an utterly ignorant and repugnant article by Peter Dreier at around the same time. Arrogantly entitled “I Don’t Care who Killed JFK”, it did not mention one word about any of the history chronicled above. It did not mention any of the books I referenced. It did not refer to Nasser, the Iranian coup, John McCloy and the assassination attempt on Carter, or Kennedy’s disdain for Saudi Arabia. And since it did not mention any of those, it could not list the reversals that occurred in the Middle East afterwards.

Peter Dreier should stick to urban planning. His article on JFK proves that underneath arrogance there is always a whiff of stupidity.

(Originally posted November 23, 2015 Reposted February 15, 2016)

-

Introduction to JFK’s Foreign Policy: A Motive for Murder

In a little over a year [2013-2014], I have spoken at four conferences. These were, in order: Cyril Wecht’s Passing the Torch conference in Pittsburgh in October of 2013; JFK Lancer’s 50th Anniversary conference on the death of JFK, in Dallas in November of 2013; Jim Lesar’s AARC conference in Washington on the 50th Anniversary of the Warren Commission in September of 2014; and Lancer’s Dallas conference on the 50th anniversary of the Commission in November of 2014.

At all four of these meetings, I decided to address an issue that was new and original. Yet, it should not have been so, not by a long shot. The subject I chose was President Kennedy’s foreign policy outside of Vietnam and Cuba. I noted that, up until now, most Kennedy assassination books treat Kennedy’s foreign policy as if it consisted of only discussions and reviews of Cuba and Vietnam. In fact, I myself was guilty of this in the first edition of Destiny Betrayed. My only plea is ignorance due to a then incomplete database of information. I have now come to conclude that this view of Kennedy is solipsistic. It is artificially foreshortened by the narrow viewpoint of those in the research community. And that is bad.

Why? Because this is not the way Kennedy himself viewed his foreign policy, at least judging by the time spent on various issues—and there were many different topics he addressed—or how important he considered diverse areas of the globe. Kennedy had initiated significant and revolutionary policy forays in disparate parts of the world from 1961 to 1963. It’s just that we have not discovered them.

Note that I have written “from 1961 to 1963”. Like many others, I have long admired Jim Douglass’ book JFK and the Unspeakable. But in the paperback edition of the book, it features as its selling tag, “A Cold Warrior Turns.” Today, I also think that this is a myth. John Kennedy’s unorthodox and pioneering foreign policy was pretty much formed before he entered the White House. And it goes back to Saigon in 1951 and his meeting with State Department official Edmund Gullion. Incredibly, no author in the JFK assassination field ever mentioned Gullion’s name until Douglass did. Yet, after viewing these presentations, the reader will see that perhaps no other single person had the influence Gullion did on Kennedy’s foreign policy. In a very real sense, one can argue today that it was the impact of Gullion’s ideas on young Kennedy that ultimately caused his assassination.

These presentations are both empirically based. That is, they are not tainted or colored by hero worship or nostalgia. They are grounded in new facts that have been covered up for much too long. In fact, after doing this research, I came to the conclusion that there were two cover-ups enacted upon Kennedy’s death. The first was about the circumstances of his murder. That one, as Vince Salandria noted, was designed to fall apart, leaving us with a phony debate played out between the Establishment and a small, informed minority. The second cover-up was about who Kennedy actually was. This cover-up was supposed to hold forever. And, as it happens, it held for about fifty years. But recent research by authors like Robert Rakove and Philip Muehlenbeck, taking their cue from Richard Mahoney’s landmark book, JFK: Ordeal in Africa, have shown that Kennedy was not a moderate liberal in the world of foreign policy. Far from it. When studied in its context—that is, what preceded it and what followed it—Kennedy’s foreign policy was clearly the most farsighted, visionary, and progressive since Franklin Roosevelt. And in the seventy years since FDR’s death, there is no one even in a close second place.

This is why the cover-up in this area had to be so tightly held, to the point it was institutionalized. So history became nothing but politics. Authors like Robert Dallek, Richard Reeves, and Herbert Parmet, among others, were doing the bidding of the Establishment. Which is why their deliberately censored versions of Kennedy were promoted in the press and why they got interviewed on TV. It also explains why the whole School of Scandal industry, led by people like David Heymann, prospered. It was all deliberate camouflage. As the generals, in that fine film Z, said about the liberal leader they had just murdered, Let us knock the halo off his head.

But there had to be a reason for such a monstrous exercise to take hold. And indeed there was. I try to present here the reasons behind its almost maniacal practice. An area I have singled out for special attention was the Middle East. Many liberal bystanders ask: Why is the JFK case relevant today? Well, because the mess in the Middle East now dominates both our foreign policy and the headlines, much as the Cold War did several decades ago. And the roots of the current situation lie in Kennedy’s death, whereupon President Johnson began the long process which reversed his predecessor’s policy there. I demonstrate how and why this was done, and why it was kept such a secret.

It is a literal shame this story is only coming to light today. John Kennedy was not just a good president. Nor was he just a promising president. He had all the perceptions and instincts to be a truly great president.

That is why, in my view, he was murdered. And why the dual cover-ups ensued. There is little doubt, considering all this new evidence, that the world would be a much different and better place today had he lived. Moreover, by only chasing Vietnam and Cuba, to the neglect of everything else, we have missed the bigger picture. For Kennedy’s approach in those two areas of conflict is only an extension of a larger gestalt view of the world, one that had been formed many years prior to his becoming president.

That we all missed so much for so long shows just how thoroughly and deliberately it had been concealed.

{aridoc engine=”google” width=”400″ height=”300″}images/ppt/JimDFP-Wecht2013.pptx{/aridoc}

{aridoc engine=”google” width=”400″ height=”300″}images/ppt/JimDFP-Lancer2014.pptx{/aridoc}

Version given at November in Dallas, November 18, 2016

{aridoc engine=”google” width=”400″ height=”300″}images/ppt/JimDFP-Lancer2016.pptx{/aridoc}

Revision, presented on March 3, 2018, in San Francisco

{aridoc engine=”google” width=”400″ height=”300″}images/ppt/JimD-JFK-FP-2018.pptx{/aridoc}

-

Who Murdered Yitzhak Rabin?

From the July-August 1999 issue (Vol. 6 No. 5) of Probe

It took almost two years for the American public to suspect a conspiracy was involved in the Kennedy assassination. It took less than two weeks before suspicions arose among many Israelis that Rabin was not murdered by a lone gunman.

The first to propose the possibility, on November 11, one week following the assassination, was Professor Michael Hersiger, a Tel Aviv University historian. He told the Israeli press, “There is no rational explanation for the Rabin assassination. There is no explaining the breakdown. In my opinion there was a conspiracy involving the Shabak. It turns out the murderer was in the Shabak when he went to Riga. He was given documents that permitted him to buy a gun. He was still connected to the Shabak at the time of the murder.”

Hersiger’s instincts were right, but he believed the conspirators were from a right wing rogue group in the Shabak. It wasn’t long before suspicions switched to the left. On the 16th of November, a territorial leader and today Knesset Member Benny Eilon called a press conference during which he announced, “There is a strong suspicion that Eyal and Avishai Raviv not only were connected loosely to the Shabak but worked directly for the Shabak. This group incited the murder. I insist that not only did the Shabak know about Eyal, it founded and funded the group.”

The public reaction was basically, “Utter nonsense.” Yet Eilon turned out to be right on the money. How did he know ahead of everyone else?

Film director Merav Ktorza and her cameraman Alon Eilat interviewed Eilon in January, 1996. Off camera he told them, “Yitzhak Shamir called me into his office a month before the assassination and told me, ‘They’re planning to do another Arlosorov on us. Last time they did it, we didn’t get into power for fifty years. I want you to identify anyone you hear of threatening to murder Rabin and stop him.’” In 1933, a left wing leader Chaim Arlosorov was murdered in Tel Aviv and the right wing Revisionists were blamed for it. This was Israel’s first political murder and its repercussions were far stronger than those of the Rabin assassination which saw the new Likud Revisionists assume power within a year.

Shamir was the former head of the Mossad’s European desk and had extensive intelligence ties. He was informed of the impending assassination in October. Two witnesses heard Eilon make this remarkable claim but he would not go on camera with it or any other statement. Shortly after his famous press conference and testimony to the Shamgar Commission, Eilon stopped talking publicly about the assassination.

There are two theories about his sudden shyness. Shmuel Cytryn, the Hebron resident who was jailed without charge for first identifying Raviv as a Shabak agent, has hinted that Eilon played some role in the Raviv affair and he was covering his tracks at the press conference.

Many others believe that pressure was applied on Eilon using legal threats against his niece Margalit Har Shefi. Because of her acquaintanceship with Amir, she was charged as an accessory to the assassination. To back up their threats, the Shabak had Amir write a rambling, incriminating letter to her from prison. The fear of his niece spending a decade in jail would surely have been enough to put a clamp down on Eilon.

Utter nonsense turned into utter reality the next night when journalist Amnon Abramovitch announced on national television that the leader of Eyal, Yigal Amir’s good friend Avishai Raviv, was a Shabak agent codenamed “Champagne” for the bubbles of incitement he raised.

The announcement caused a national uproar. One example from the media reaction sums up the shock. The newspaper Maariv wrote: “Amnon Abramovitch dropped a bombshell last night, announcing that Avishai Raviv was a Shabak agent codenamed ‘Champagne.’ Now we ask the question, why didn’t he [Avishai Raviv] report Yigal Amir’s plan to murder Rabin to his superiors..? In conversations with security officials, the following picture emerged. Eyal was under close supervision of the Shabak. They supported it monetarily for the past two years. The Shabak knew the names of all Eyal members, including Yigal Amir.”

That same day, November 16, 1995, the newspaper Yediot Ahronot reported details of a conspiracy that will not go away. “There is a version of the Rabin assassination that includes a deep conspiracy within the Shabak. The Raviv affair is a cornerstone of the conspiracy plan.

“Yesterday, a story spread among the settlers that Amir was supposed to fire a blank bullet but he knew he was being set up so he replaced the blanks with real bullets. The story explains why after the shooting, the bodyguards shouted that ‘the bullets were blanks.’ The story sounds fantastic but the Shabak’s silence is fueling it.”

Without the ‘Champagne’ leak, this book would likely not be written. Despite all the conflicting testimony at the Shamgar Commission, the book would have been closed on Yigal Amir and the conspiracy would have been a success. But Abramovitch’s scoop established a direct sinister connection between the murderer and the people protecting the prime minister.

So who was responsible for the leak? There are two candidates who were deeply involved in the protection of Eyal but probably knew nothing of its plans to murder Rabin. They are then-Police Minister Moshe Shahal and then-Attorney General Michael Ben Yair.

Shahal was asked for his reaction to the Abramovitch annoucement. He said simply, “Amnon Abramovitch is a very reliable journalist.” In short, he immediately verified the Champagne story.

Not that he didn’t know the truth, as revealed in the Israeli press:

Maariv, November 24, 1995

The police issued numerous warrants against Avishai Raviv but he was never arrested. There was never a search of his home.

Kol Ha Ir, January, 1996

Nati Levy: “It occurs to me in retrospect that I was arrested on numerous occasions but Raviv, not once. There was a youth from Shiloh who was arrested for burning a car. He told the police that he did it on Raviv’s orders. Raviv was held and released the same day.”

Yediot Ahronot, December 5, 1995

When they aren’t involved in swearing-in ceremonies, Eyal members relax in a Kiryat Araba apartment near the home of Baruch Goldstein’s family. The police have been unsuccessfully searching for the apartment for some time.

Everyone in the media knew about the apartment, as did everyone in Kiryat Arba. It was in the same building as the apartment of Baruch Goldstein, the murderer of 29 Arabs in the Hebron massacre of March ’94. The police left it alone because Raviv used it for surveillance.

He was also immune to arrest for such minor crimes as arson and threatening to kill Jews and Arabs in televised swearing-in ceremonies. But police inaction was inexcusable in two well-publicized incidents.

Yerushalayim, November 10, 1995

Eyal activists have been meeting with Hamas and Islamic Jihad members to plan joint operations.

This item was reported throughout the country, but Avishai Raviv was not arrested for treason, terrorism and cavorting with the enemy. Less explainable yet was the police reaction to Raviv taking responsibility, credit as he called it, for the murder of three Palestinians in the town of Halhoul.

On December 11, 1993, three Arabs were killed by men wearing Israeli army uniforms. Eyal called the media the next day claiming the slaughter was its work. But Moshe Shahal did not order the arrest of Eyal members. He knew Eyal wasn’t rsponsible. He knew they only took responsibility to blacken the name of West Bank settlers. His only action, according to Globes, December 13, 1993, was to tell “… the cabinet that heightened action was being taken to find the killers and to withdraw the legal rights of the guilty organization.”

After a week of international condemnation of the settlers, the army arrested the real murderers, four Arabs from the town.

At that point Shahal should have had Raviv arrested for issuing the false proclamation on behalf of Eyal. But Shahal did not because he was ordered not to interfere with this Shabak operation. As was Attorney-General Michael Ben Yair, who was so terrified of what could be revealed at the Shamgar Commission that he sat in on every session on behalf of the government and later approved, along with Prime Minister Peres, the sections to be hidden from the public.

After the assassination, it emerged that two left wing Knesset members had previously submitted complaints against Eyal to Ben Yair. On March 5, 1995 Dedi Tzuker asked Ben Yair to investigate Eyal after it distributed inciteful literature at a Jerusalem high school. And on September 24, 1995, Yael Dayan requested that Ben Yair open an investigation of Eyal in the wake of its televised vow to spill the blood of Jews and Arabs who stood in the way of their goals. He ignored both petitions, later explaining, “Those requests should have been submitted to the army or the Defence Minister,” who happened to be Yitzhak Rabin.

Both Shahal and Ben Yair were, probably unwittingly, ordered to cover up Eyal’s incitements. But when one incitement turned out to be the murder of Rabin, one of them panicked and decided to place all the blame on the Shabak.

Which one?

According to Abramovitch, “I have a legal background so my source was a high ranking legal official.” It sounds like the winner is Ben Yair, which hardly exonerates him or Shahal for supplying Eyal with immunity from arrest or prosecution, without which the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin would not have been possible. However, Ben Yair opened a police complaint against the leaker, and as late as June of ’96, reporter Abramovich was summoned to give evidence. The leak thus came from a “traitor” in Ben Yair’s office. And because there are Israelis who know the truth and are willing to secretly part with it, this book could be written.

The Testimony Of Chief Lieutenant Baruch Gladstein: Amir Didn’t Shoot Rabin

Everyone who saw the “amateur” film of the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin witnessed the alleged murderer Yigal Amir shoot the Prime Minister from a good two feet behind him. The Shamgar Commission determined that Amir first shot Rabin from about 50 cm. distance. Then bodyguard Yoran Rubin jumped on Rabin, pushing him to the ground. Amir was simultaneously accosted by two policemen who held both his arms. Yet somehow Amir managed to step forward and shoot downward, first hitting Rubin in the elbow and then Rabin in the waist from about 30-40 cm. distance.

The amateur film of the assassination disputes the whole conclusion. After the first shot, Rabin keeps walking, there is a cut in the film and Rabin reappears standing all alone. Rubin did not jump on him and Amir has disappeared from the screen. He did not move closer nor get off two shots at the prone Rubin or Rabin.

And there is indisputable scientific proof to back what the camera recorded.

What if the shots that killed Rabin were from both point blank range and 25 cm. distance? Obviously, if so, Amir couldn’t have shot them.

Now consider the testimony of Chief Lieutenant Baruch Gladstein of Israel Police’s Materials and Fibers Laboratory, given at the trial of Yigal Amir on January 28, 1996:

I serve in the Israel Police Fibers and Materials Laboratory. I presented my professional findings in a summation registered as Report 39/T after being asked to test the clothing of Yitzhak Rabin and his bodyguard Yoram Rubin with the aim of determining the range of the shots.

I would like to say a few words of explanation before presenting my findings. We reach our conclusions after testing materials microscopically, photographically and through sensitive chemical and technical procedures. After being shot, particles from the cartridge are expelled through the barrel. They include remains of burnt carbon, lead, copper and other metals…

The greater the distance of the shot, the less the concentration of the particles and the more they are spread out. At point blank range, there is another phenomenon, a characteristic tearing of the clothing and abundance of gunpowder caused by the gases of the cartridge having nowhere to escape. Even if the shot is from a centimeter, two or three you won’t see the tearing and abundance of gunpowder. These are evident only from point blank shots.

To further estimate range, we shoot the same bullets, from the suspected weapon under the same circumstances. On November 5, 1996, I received the Prime Minister’s jacket, shirt and undershirt as well as the clothes of the bodyguard Yoram Rubin including his jacket, shirt and undershirt. In the upper section of the Prime Minister’s jacket I found a bullet hole to the right of the seam, which according to my testing of the spread of gunpowder was caused by a shot from less than 25 cm. range. The same conclusion was reached after testing the shirt and undershirt.

The second bullet hole was found on the bottom left hand side of the jacket. It was characterized by a massed abundance of gunpowder, a large quantity of lead and a 6 cm. tear, all the characteristics of a point blank shot.”

The author rudely interrupts lest anyone miss the significance of the testimony. Chief Lieutenant Gladstein testifies that the gun which killed Rabin was shot first from less than 25 cm. range and then the barrel was placed on his skin. In fact, according to a witness at the trial, Nat an Gefen, Gladstein said 10 cm and such was originally typed into the court protocols. The number 25 was crudely written atop the original 10. If the assassination film is to be believed, Amir never had a 25 cm. or 10 cm. shot at Rabin or even close to one. As dramatic a conclusion as this is, Officer Gladstein isn’t through. Far from it.

As to the lower bullet hole, according to the powder and lead formations and the fact that a secondary hole was found atop the main entry hole, it is highly likely that the Prime Minister was shot while bending over. The angle was from above to below. I have photographs to illustrate my conclusions.”

The court was now shown photographs of Rabin’s clothing. We add, according to the Shamgar Commission findings, Rabin was shot first standing up and again while prone on the ground covered by Yoram Rubin’s body. Nowhere else but in Gladstein’s expert testimony is there so much as a hint that he was shot while in a bent-over position.