I listened to all 8 parts of Murder on the Towpath. This was Soledad O’Brien’s four hour podcast about the death of Mary Meyer. It was a difficult experience for someone familiar with that case and does not have blinders on about what happened.

O’Brien did something that no independent journalist should do, but which I knew she would do when I read the interviews she was giving to drum up publicity for her project. She decided to turn Mary Meyer into something she was not, that is, an advocate for world peace along with her former husband Cord Meyer during his days as a world federalist movement advocate. To be specific, Cord was president of United World Federalists. In his book, Facing Reality, there is no evidence that Mary shared his interests on the subject. (Cord Meyer, Facing Reality, p. 39) As I noted previously, in that book Cord wrote that his position in the group actually created a distance between him and his family, so he resigned and went to Harvard on a fellowship. (ibid, pp. 56-57) While he was there, Mary did take classes, but in Design rather than in Political Science. This is where she discovered her aptitude for painting. Further, in 1951, when Cord was about to join the CIA, she did not object to this. She encouraged him to do so. (ibid, p. 65) Their divorce was not over the nature of his work, but the fact that he spent too much time on it. (ibid, p. 142)

In the first part of this podcast, none of this is presented. In fact, O’Brien actually tells us the contrary was the case: Mary and Cord came together over the subject of world federalism. The problem is that this deduction is made, not from the evidentiary record, but in spite of it. Not only is there no evidence of Mary’s interest in the subject while she was married, there is no evidence of it before or after. After Harvard and their divorce, Mary got custody of the children. She had an affair with art instructor Ken Noland. She was interested in painting. Before she was married, she did some freelance writing for UPI and Mademoiselle. She wrote on things like sex education and venereal disease. (New Times, July 9, 1976) So where is the evidence for her powerful belief in a world governmental organization, a supranational one, one more powerful than the United Nations? In the more than half century since her death, nothing of any substance or credibility has surfaced to fill in this lacuna. So, the idea of Mary Meyer being some kind of a non-conformist, in either her informed political ideas or some kind of women’s liberation model like Betty Friedan, this simply lacks foundation. Yet, in that first segment, O’Brien does mention Friedan in relation to Mary. To me, this whole opening segment which attempted to aggrandize Mary Meyer was mostly bombast. It served as a warning about what was to come.

In the second segment, the warning lights began flashing red. Here, O’Brien introduced her co-heroine, Dovey Roundtree. Roundtree was the African-American female attorney who chose to defend Ray Crump. Crump was the African-American day laborer who was accused of shooting Mary Meyer on October 14, 1964. As with Mary and Betty Friedan, O’Brien now attempts to aggrandize the Crump case: she mentions it in regards to the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till.

O’Brien actually said this and tried to place the Meyer case in the same context, on the rather simplistic grounds that Crump was African-American and he was accused of killing a Caucasian woman, while Till had allegedly been flirting with a Caucasian woman.

Emmett Till was killed in 1955 on a visit to relatives in Mississippi. He was beaten to the point that his face could not be recognized by his mother, who made the identification by a ring on the corpse’s finger. Even though everyone knew who the two kidnappers and killers were, they were acquitted by an all-white jury in one hour. Till’s mother demanded an open casket funeral at their home in Chicago. In five days over 100,000 people paid their respects. Pictures of the funeral and the corpse were picked up by the magazine Jet. This, plus the fact that the two killers confessed in Look magazine for money, turned the case into a national scandal and a milestone in the civil rights movement. (Click here for more details)

Anyone can see the difference in these two cases. There is and was no question as to who killed Till. They were identified as the kidnappers and they later confessed. There was also no question about the motive: it was simply white supremacy. There was no question about why the killers got away with the crime: it was 1955, Mississippi, and an all-white jury. The Meyer case was ten eventful years later; after the passage of John Kennedy’s epochal civil rights bill in congress, during the era of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. In the Crump case, the murder scene was not deep south Mississippi, but cosmopolitan, upscale Georgetown. Because of all this, the jury in the Crump case was not all white, it was mixed. (New York Times, May 21, 2018, obituary for Roundtree by Margalit Fox)

As the reader can see, by relating Mary Meyer to both idealistic world peace and government advocates, and as an equivalent to Betty Friedan, and doing the same to the case of Ray Crump and the milestone murder of Till, O’Brien is inflating her subject beyond any legitimate boundaries. To me, someone who is familiar with the Meyer case, that inflation is so overdrawn that it amounts to sensationalism.

II

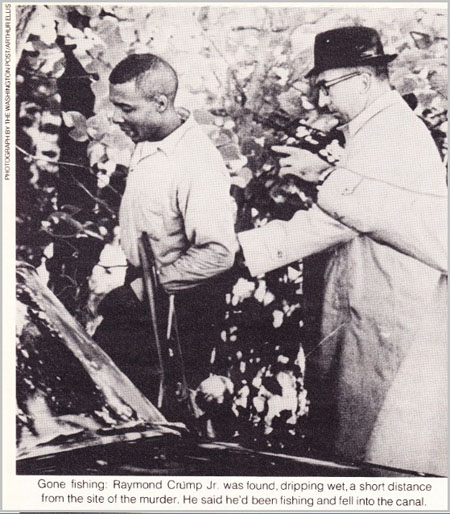

In part 2 of the series, O’Brien got to Roundtree and her advocacy for Crump. On the day of the Meyer murder, the case had been called in by witness Henry Wiggins. The official exits to the crime scene, the C&O towpath and park area, were sealed off within five minutes. Crump was found dripping wet, without his shirt and cap, hiding in the spillway near the canal and the Potomac. He was also covered with grass and twigs. When he pulled out his wallet for identification, that was dripping water also. (op. cit. New Times)

Crump said that he was there because he was fishing. He had fallen asleep on the river bank and woke up when he slid down the bank and into the river. At the scene, while Crump was showing the arresting officer where he was fishing, Wiggins shouted at the officer, “That’s him!” And he pointed at Crump. (ibid)

When the suspect was brought to Detective Crooke, the supervising officer on the scene, he asked him why his fly was open. Crump accused the police of unzipping it. This was enough for Crump to be brought back to the station for questioning. While there, an officer brought in a windbreaker jacket found at the park. It fit Crump perfectly. A witness had seen Crump leave his house that day with no fishing pole, but with a cap and windbreaker. As Lisa Pease has noted, the description of these articles of clothing was similar to what Wiggins said he saw the assailant wearing. And Crump’s fishing bait and pole were later found at his home. (Click here for details) Yet Crump had told his arresting officer that he had not been wearing these articles of clothing. (Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman, p. 234)

O’Brien understands the import of the above, so she skips over some of it and then brings up the subject of “Vivian.” I have dealt with this angle in a previous installment posted last month. Vivian was supposed to be the person who was with Crump at the time of the shooting of Mary Meyer. (Click here for details) I was not surprised that O’Brien brought this whole issue up, simply because of the enormous spin she was putting on the whole story. In its simplest terms, it gives Crump an alibi. But even with a small amount of research, O’Brien’s fact checker could have discovered that the whole Vivian story makes Roundtree look worse, not better. It shows she had overcommitted herself—as lawyers often do—to her client. If one reads the above brief link, the phantasm of Vivian contains so many holes, so many inconsistencies—not just by Crump, but by Roundtree—that it smacks of being a fabrication (e.g. Roundtree couldn’t keep her story straight about if she knew where Vivian lived). Further, as one reads that linked synopsis, there are indications that Roundtree cooperated in the creation of “Vivian”.

In sum, there was no fishing pole or tackle, and in all likelihood, there was no alibi. With the disintegration of the fishing pretext, it made it harder for Crump to explain his bloody hand, which he said he had cut on a fishhook. (Burleigh p. 265) In other words, there was plentiful probable cause to arrest Crump for the crime. The questions become: What was Crump doing there? And why was he lying about it? In fact, when the clothing was produced, Crump started weeping and muttered, “Looks like you got a stacked deck.” (Burleigh, p. 234) O’Brien does not really have to explain much of this because of “Vivian.”

III

In court, Dovey Roundtree did not present an affirmative defense. There was no opening statement and she called only three witnesses in the eight-day trial. She got an acquittal for her client due to three major issues in the case. As Roundtree stressed in her summation, even though there was an extensive search, which included draining the canal, the .38 handgun used in the shooting was never recovered. She asked the jury, “Where is the gun?” (Washington Daily News, July 29, 1965, story by J. T. Maxwell) Secondly, the prosecution presented huge photographs of the park to stress that the killer could not have escaped due to the quick closing off of all the entries and exits. But Roundtree stated that in visiting the park she had found other ways out of the area. Also, when measured by the police, Crump was 5’ 5 ½”. Wiggins said the man he saw attacking Meyer was 5’ 8”.

The prosecutor, Alfred Hantman, tried to counter the last two points in his summation. Concerning the former, he said that in order to escape, the assailant would have had to swim across a sixty foot canal and then scale an eight foot embankment. To counter the second, Hantman produced the shoes Crump was wearing the day of the shooting. They were elevated, meaning they added as much as two inches to his height. He implored the jury during his rebuttal, “Do we quibble over a half inch?” (ibid)

Roundtree had raised a reasonable doubt with the jury. After several hours, they told the judge they were deadlocked. He insisted that they continue to deliberate. After a total of eleven hours, they came in with a verdict of not guilty. (New Times)

O’Brien uses this verdict to go into the whole reputed relationship between Mary Meyer and President John F. Kennedy. Here she grabs onto just about every piece of flotsam and jetsam that has ever been floated in the Meyer case. She even brings up Kennedy’s alleged “affair” with Marilyn Monroe. A notion that Don McGovern has virtually demolished. (Click here for details) And like the ludicrous notion that Monroe was part of some key decisions in JFK’s administration—when McGovern shows she was never at the White House—O’Brien says in segment five that Meyer was a part of the Oval Office furniture.

This is utterly farcical. No cabinet officer or advisor has ever said any such thing in any kind of memoir or essay that I have ever encountered. Why would Kennedy be so stupid as to do such a thing? What would she be there for anyway? Was she doing a portrait? O’Brien actually says that Kennedy wanted her there intellectually. As I have explained previously, there is no way in the world that Kennedy ever needed Mary Meyer to make any kind of serious political decision, especially in the foreign policy area. This is as silly as O’Brien saying that she came across a mash letter that Kennedy sent Meyer. And it was written on White House stationery! I guess JFK just couldn’t help himself. The chain of possession on this note is non-existent. But someone was stupid enough to pay five figures for this at an auction and so O’Brien reads it during the podcast. I guess no one ever told our unsuspecting host about the Lex Cusack forgeries. (Click here for details)

In part five, our hostess continues with her incurable inflation. This time it is about Mary’s paintings. Meyer now becomes a very accomplished painter. What does our hostess base this upon? Largely on Mary’s painting entitled “Half Light”. (Click here for details) To me, this painting is, at best, clever. It’s something that a college junior could think up and then execute. To my knowledge, Meyer only had one showing of her work. Yet, towards the end, in part 8, O’Brien talks about Mary’s “artistic legacy”. Jackson Pollock had an artistic legacy. Edward Hopper had an artistic legacy. Has anyone ever read a book about modern American painting in which the author described Mary Meyer’s artistic legacy? If so, I would like to read it.

IV

Given the above approach to the Meyer case, I waited for O’Brien to bring up the accusations of Timothy Leary and James Truitt. In episode five, she did. As I have previously noted, in his book Flashbacks, Tim Leary wrote that he had supplied Mary Meyer with tabs of LSD. Although Leary never named Kennedy as someone she passed on the acid to, it was pretty obvious that this is what the author was implying. If one can believe it, this allegation was actually accepted and then repeated in some Kennedy biographies. It was also accepted by Paul Hoch and printed in his journal, Echoes of Conspiracy. (No surprise there, since Hoch actually took Tony Summers’ diaphanous book about Marilyn Monroe seriously.)

Flashbacks was published in 1983. The scene that Leary drew in that book between himself and Meyer was both mysterious and indelible. Meyer appears to him and says she and a small circle of friends in Georgetown were turning on. She consulted him about how to conduct such sessions and also how to obtain LSD. She mentioned one other “important person” she wanted to turn on. After Kennedy’s assassination, she appeared to Leary again. She tells Leary that “They couldn’t control him anymore. He was changing too fast. He was learning too much.” Leary said that after he learned about Meyer’s death he put the story together. (The Assassinations, edited by James DiEugenio and Lisa Pease, p. 341)

I have to confess that I actually accepted this story myself, when I first heard about it. Someone sent me the section of Flashbacks dealing with Mary Meyer when it was issued as a magazine reprint. To my present embarrassment, I actually talked about it at a gathering in San Francisco. But the more I learned about Leary—especially from the book Acid Dreams—the more suspicious I became about him. So one day in a large college library, I collected almost all the books Leary had written from 1964 to 1982, which was not easy. Somehow, Leary published about forty books in his life, about 25 of them before Flashbacks. In none of those 25 books—which I eventually all found—was there any mention of Mary Meyer. In other words, from the time of her death in 1964 until 1983—a period of 20 years—Leary passed up over a score of opportunities to mention this episode, which, if it were true, clearly had to be the high point of his drug distribution career. And some of those books, like High Priest, were almost day-to-day diaries.

But, as I have proven elsewhere, the idea that somehow Kennedy was altering his foreign policy views in a basic way in 1962 is simply not accurate. As I have noted elsewhere, JFK’s overall foreign policy was formed by the time he was inaugurated. The only serous alteration in 1962 was through the Missile Crisis. (See Chapters 2 and 3 of Destiny Betrayed, second edition by James DiEugenio.)

What makes the story even more improbable is that Flashbacks was published at the 20th anniversary of Kennedy’s death. Was that a coincidence? I don’t think so. Further, in that book, Leary also said he slept with Marilyn Monroe. In all probability, Leary was using Meyer, Kennedy, and Monroe in an effort at salesmanship. This is the conclusion that biographer Robert Greenfield also came to in his book about Leary. Mark O’Blazney, who we will encounter later, knew both Leary and his colleague Richard Alpert, who worked with the drug guru at Harvard. When Mark asked Alpert if he had ever seen Mary either with Leary or on the grounds, he said no. He then added that Tim had a penchant for pitching malarkey about himself. (O’Blazney interview with author, 8/17/20)

James Truitt was the first person to ever say anything for broad publication about the relationship between Meyer and Kennedy. He did this in 1976 for the National Enquirer He said that in 1962–63 Mary and Kennedy were having an affair. He also added that they smoked weed together in the White House. In fact, Truitt said he rolled the joints they smoked! Further, Kennedy said that she should try cocaine.

As I noted in my review of Peter Janney’s Mary’s Mosaic, when the Enquirer published this story they gave very little background on Truitt. After all, a logical question would be: Why did Truitt wait over ten years to reveal this story? There was a personal reason behind the timing. And the Enquirer was wise not to reveal it.

Ben Bradlee’s second wife, Toni, was Mary Meyer’s sister. Toni was his wife while Kennedy was in the White House. Bradlee was one of the closest contacts JFK had in the media. In addition to that, he was also a personal friend. So, when the Bradlees were invited to the White House for certain social or political functions—which was not infrequent—Mary would come along.

In 1968, Ben Bradlee was promoted to executive editor of the Washington Post. A year later, he fired Truitt. According to author Nina Burleigh, Truitt had a serious alcohol problem at the time. Further, he was showing signs of mental instability and perhaps even a nervous breakdown. (Burleigh, p. 284; Washington Post 2/23/76) Bradlee forced Truitt out with a settlement of $35,000. (Burleigh, p. 299) Truitt’s problems now grew worse. It got so bad that that his wife, Anne Truitt, tried to get a legal conservatorship assigned to him. This was based on a doctor’s declaration that Jim Truitt was suffering from a mental affliction (Burleigh, p. 284) The doctor wrote that Truitt had become incapacitated to a point “such as to impair his judgment and cause him to be irresponsible.” (ibid, italics added.) As a result, in 1971, his wife divorced him. In 1972, the conservator assigned to him also left.

This left Truitt in a forlorn state. He now wrote to Cord Meyer and requested he secure him a position at the CIA. When that did not occur, he moved to Mexico. He remarried and lived with a group of former Americans, many of whom were former CIA agents. And he now began to experiment with psychotropic drugs. (Burleigh, p. 284) If all this was not bad enough, the motive behind the article was for Truitt to revenge himself on Bradlee for firing him. Specifically to show that the reputation that Bradlee had garnered for himself during the Watergate affair was not really warranted. Somehow, Bradlee knew all about these goings on in the White House and not revealed it.

What kind of witnesses are these? I mean a guy doing psychotropic drugs in Mexico in the midst of a bunch of CIA agents? And who is now trying to extract revenge on the guy who fired him almost ten years earlier? Another witness who had two decades and 25 opportunities to tell us he was supplying LSD to Mary Meyer, but never breathed a word of it? But he does on the 20th anniversary of Kennedy’s death? And whose colleague calls him a BS peddler? As the reader can predict, O’Brien did not say anything to her listeners about the problems with Leary and Truitt. Not a word.

V

The worst part of Murder on the Towpath was episode seven. This constituted O’Brien’s attempt to get in all the stuff that Leo Damore and Peter Janney had worked on for years. Damore was the published author researching the Meyer case. When he died by his own hand in 1995, his acquaintance Peter Janney now picked up the work he had done. O’Brien wants to use this, as we shall see, dubious material. But she does not want to be labeled a conspiracy theorist. So what does she do? She places a lot of it in this, her longest episode. But she frames it with an interview with a social scientist who tries to explain why, psychologically, certain people need to believe in conspiracy theories. She also does not actually interview Janney; she plays a brief tape of him speaking. Talk about playing both ends against the middle.

To repeat and update all the problems with the work of Damore and Janney would take a long and coruscating essay in and of itself. I have already referenced Lisa Pease’s review of Janney’s Mary’s Mosaic. If the reader needs more evidence of how seriously flawed that book is, please look at my review also. (Click here for details)

Before turning to what O’Brien actually says in this segment, let me comment on her practice of playing both ends against the middle. There are certain homicide cases of high-profile persons that are provable conspiracies. And this site is dedicated to showing the public that such was the case. We don’t need some kind of counseling by an academic to explain why we think what we do about, for example, the assassination of Robert Kennedy. We can prove, rather easily, why his murder could not have been performed by one man. In the Mary Meyer case, the circumstances do not come close to approaching that level of clarity. For example, there was not an institutional cover up afterwards, the defendant did not have incompetent counsel, there was not another suspect at the scene of the crime, and it was not a case of the suspect not having a sociopathic personality.

To take just the last, Nina Burleigh did an unprecedented inquiry into the life of Ray Crump. After being emotionally appealed to by Crump’s mother, Roundtree tried to present him in court as being a rather innocent waif caught up in a miscarriage of justice. (Justice Older than the Law by Roundtree with Katie McCabe, pp. 190-94) But smartly, she never put Crump on the stand. As Burleigh found out, Crump had an alcohol problem prior to his arrest in the Meyer case. He suffered from severe headaches and even blackouts. His first wife detested his drinking, because, when intoxicated, he would become violent toward the women around him. (Burleigh, p. 243) And there was evidence, by Crump himself, that he had been drinking that day. After his acquittal, this tendency magnified itself exponentially. Crump became a chronic criminal. He was arrested 22 times. The most recurrent charges were arson and assault with a deadly weapon. (ibid, p. 278) His first wife left him during the trial and she fled the Washington area. Meyer biographer Burleigh could not find her in 1998.

Crump remarried. In 1974, he doused his home with gasoline, with his family inside. He then set the dwelling afire. From 1972–79, Crump was charged with assault, grand larceny, and arson. His second wife left him. In 1978, he set fire to an apartment building where his new girlfriend was living. He had previously threatened to kill her. He later raped a 17-year-old girl. He spent four years in prison on the arson charge. (Burleigh, p. 280)

When Crump was released in 1983, he set fire to a neighbor’s car. He was jailed again. When he got out in 1989, he lived in North Carolina. In a dispute with an auto mechanic, he tossed a gasoline bomb into the man’s house. He went back to prison. (Burleigh, p. 280) This long and violent record is probably the reason that, when Burleigh tracked him down, Crump would not agree to an interview. To my knowledge, he never talked to any writer on the Meyer case. Burleigh today is convinced to a 90% certainty that Crump killed Meyer.

As with the curtailment of Burleigh, the many problems with Leo Damore’s credibility are never addressed, even though O’Brien extensively uses Damore as a source in segment seven. Damore said that somehow he found the address of the actual killer of Mary Meyer. He wrote to him. And the killer replied to Damore’s letter! But even more bizarre, Damore said that he met with him. (Janney, pp. 378, 404) Damore said he talked to him extensively on the phone and taped the phone calls. This man confessed to being a CIA hit man and that Meyer’s death was a black operation. This is all very hard to buy into. Damore discovers his Holy Grail; the key to the book he was working on. That guy talks to him for hours on end, on the phone and in person. Yet there is no tape of the call that exists. And none has surfaced in the intervening decades after Damore’s death. As I previously wrote, this smells to high heaven. Any experienced writer would have taped the calls, had them transcribed, and then placed the originals in a safe deposit box. There is no evidence that any of that was done, even though Damore was an experienced writer who had written five books. And according to Damore, he had a time frame of two years to do this in.

Damore also said that Fletcher Prouty revealed to him the name of the assassin. Len Osanic, the keeper of the Prouty files, said Fletcher almost never did this kind of thing (i.e. expose someone’s cover). The only exceptions were when the person under suspicion had a high-level profile (e. g. Alexander Butterfield). But further, Prouty was out of the service at the time of Meyer’s death, so how he could he know about that case?

The most bizarre claim that Damore ever made is actually repeated by O’Brien, namely that Damore found a “diary” that Mary had kept. But what O’Brien does not reveal is this: Damore said he found the diary three times! (Janney, pp. 325, 328, 349) Damore even claimed that the alleged confessed assassin he interviewed had a version of it. But again, somehow, some way, Damore never thought of copying it.

No objective journalist, attorney, or author could or should accept these claims. In the field of non-fiction authorship, there is a famous dictum: Extraordinary claims necessitate extraordinary evidence. What is there to back any of the above up? There is nothing that I can detect except hearsay from Damore, who, on the adduced record, is not the most credible witness. As they say in the trade, the references here are circular: they begin with him and end with him. And there is more she left out.

One of the most surprising things about O’Brien’s podcast is that she never talked to Mark O’Blazney. This is weird, because Mark worked for Damore during the three years up to his death. He was introduced to him by Leary, who told him Damore was writing a book about the Mary Meyer case. At the start of the assignment, Damore promised to pay Mark for his work, and he did.

But as time went on, this changed. Two things happened to upset the relationship and the prospective book that Damore was writing on the Meyer case. Damore and his research assistant visited the National Archives extensively, in order to find something new on the case besides the trial transcript. They came up empty. That was a large disappointment. Secondly, Damore’s wife left him.

According to Mark, Damore never had a book, at least one that was even close to being completed. At one time, he even wailed, “I’m not finishing the book. I don’t have it.” (Question: if he talked to the admitted killer for hours, how could he not have a book?) Though he admittedly had no book, Damore would get angry at Mark for talking to other interested parties, like Deborah Davis, author of Katherine the Great. Damore was also consulting with the likes of the late professional prevaricator David Heymann. (Click here for details)

Towards the end, Damore stopped paying Mark. At the time of his death, he owed his researcher about twelve thousand dollars. He could not afford to pay him, since Damore now had substantial debts of his own. At this time, Damore would phone Mark in a troubled, barely coherent state and ask him for small amounts of money. As Lisa Pease noted, it turned out that Damore had a tumor in his brain.

Several years after Damore’s death, Peter Janney got in contact with Mark. He visited him personally. Janney spent about 3 hours interviewing Mark and paid him five thousand dollars for that and his research materials. What puzzled Mark was that toward the end of their talk, Janney started going on about space aliens. As if this had something to do with the Mary Meyer case. (Author interview with O’Blazney, 8/17/20)

VI

This background on Damore—all left out by O’Brien—brings us to William L. Mitchell. One of Damore’s claims was that the man who replied to his letter to the safehouse, and who he talked to for hours on the phone and then in person, and who also saw the Meyer “diary” was Mitchell. (Janney, p. 407) Mitchell happened to be a witness at Crump’s trial. Mitchell said he was jogging on the towpath the day Mary was killed and saw an African American male in the area. His description was similar to the other witness, Mr. Wiggins.

Janney picked up this lead. In his book, he tried to say that he could not find Mitchell. Even though Damore had talked to him on the phone and in person. Janney then questioned if Mitchell really was, as he stated to the police, a mathematics professor. The impression Janney left was that somehow Mitchell had fallen off the face of the earth a short time after the trial. The implication being he was a black operator who stayed in a safehouse and was now being protected by the CIA. But then something occurred that rocked that scenario. Researcher Tom Scully did find Mitchell. He traced him through several different sources, including academic papers he published. Tom discovered his whole collegiate history, which was pretty distinguished, ending with a Ph.D. in mathematics. This information included the fact that in his registration for certain mathematical societies, he listed his so called “safehouse” address: 1500 Arlington Blvd. Apt. 1022 in Washington DC.

When Tom Scully discovered this allegedly missing information, Janney now said that Mitchell had gone into deep cover and eluded everyone by “changing” his name to Bill Mitchell. Does this mean that if I use the name Jim DiEugenio, instead of James DiEugenio, that I am using an alias and have gone into seclusion? Of course not. But Janney was trying to save face because Scully had found that one of the tenets of the first edition of his book was rather unsound. If you can believe it—and by now you can—O’Brien parrots this silliness about “aliases,” which is further disproven by the fact that, as Scully noted, at times Mitchell did use the proper first name of William. (The Berkeley Engineering Alumni Directors of 1987, p. 225)

But it’s worse than that, because Damore said that, when he met Mitchell back in 1993, the man was 74 years old, which would mean that William Mitchell today would have to be 101. Well, when Scully found Mitchell and Janney attempted to call upon him in early 2013, it turned out he was living in Northern California and was born in 1939. In other words, the man that Damore said he talked to was not the William L. Mitchell that Scully had found for Janney. Yet, Janney admitted that the man Scully found for him was the witness at Crump’s trial. (Click here for details)

All the matters dug up by Scully and revealed by Mark O’Blazney bring up the gravest questions about what on earth Damore was doing towards the end of his life. Just what was the factual basis of his research into the Meyer case? CIA hit men do not return letters to them. They also do not print the address of the “safehouse” they have been assigned to in academic journals. And they surely do not meet with authors and confess about their black operations. If they did so they would not live long. Yet, Damore said these things occurred.

And, apparently, O’Brien believes him, because in segment 7, she even quotes Damore as saying that he talked to Ken O’Donnell. According to the deceased author, O’Donnell said that JFK was losing interest in politics because of his affair with Mary. (Janney p. 230) This is ridiculous. Kennedy was planning his campaign for 1964 in 1963. And he was also mapping out future policies, like a withdrawal from Vietnam, and the passage of his civil rights bill. How does that indicate he was losing interest? But, as Lisa Pease noted, that is not the worst of it. O’Donnell also said that Kennedy was going to leave office, divorce Jackie Kennedy and move in with Mary Meyer! What was the source for this rather shattering information? It was Janney’s interview with Damore. According to O’Blazney, about one third of the interviews that Damore did were with Janney. (Op. Cit, O’Blazney interview)

Need I add: O’Brien does not include any of this important qualifying information about Damore.

VII

O’Brien includes in her segment seven a long section on the so-called diary that Truitt alluded to back in the seventies. To me, this whole issue is almost as much a cul-de-sac as the Marilyn Monroe “diary”. (See Section 6 here for details)

In my essay on the Meyer case, which I originally wrote for Probe Magazine, I examined every version of this diary story that was then existent. I concluded that it was quite odd that none of the participants who searched for it—Ben Bradlee, Toni Bradlee, Anne Truitt, Jim Truitt, Jim Angleton, Cicely Angleton—told a cohesive, consistent story. At times, they actually seemed at odds with each other. (Probe, September/October 1997, pp. 29-34) I concluded that what was found was probably a sketch book with some traces of Mary’s relationship with Kennedy, where he was not mentioned by name. Janney then made this angle all the worse. He wrote that Damore actually found the diary not once, but three times. (Janney, pgs. 325, 328. 349) And even Mitchell had the diary. (How a witness at the trial who did not know Mary Meyer could end up with a copy of her diary was left unexplained by both Damore and Janney.) As I said, this whole diary issue has become so evanescent that it is now a non sequitur. I concluded in 1997 that if it had all the information Truitt said it had—details about the affair and the pot smoking etc.—Angleton, who had some access to it, would have found a way to get it into the press. He never did.

Yet O’Brien is not done stooping. She actually includes the information about Wistar Janney’s phone call to Ben Bradlee. After Wiggins phoned the police, the story of Meyer’s death got out into the local radio. Cicely Angleton heard about it that way and called her husband Jim. (New Times) Lance Morrow, a local reporter, was at the police station when the call came in. He called his newspaper and told them about it. (Smithsonian Magazine, December 2008) Wistar Janney, who was a CIA officer at the time, called Ben Bradlee and told him of the report he had just heard. (Bradlee, A Good Life, p. 266) From the description, Wistar thought it might be Mary. As Peter Janney made clear in his book, the two families knew each other well. Wistar Janney also called Cord Meyer when he heard the report. (Meyer, Facing Reality, p. 143)

O’Brien puts this call together with something that is, again, completely unsubstantiated: Mary was putting together pieces of the JFK assassination puzzle. The implication, borrowed from Janney, is that this is why she was killed. Wistar Janney knew both Cord Meyer and Bradlee, who was married to Mary’s sister. Who better to call than Toni’s husband and Mary’s former husband? If the news was already out, then what was conspiratorial about the call? But secondly, as I noted in my review of Janney’s book, there is nothing in the record that indicates Mary Meyer was investigating the JFK case. How could she if the Warren Report had just been published two weeks earlier? It was 888 pages long with 6,000 footnotes. The testimony and evidence to those footnotes had not been issued at the time of her death, so how could she cross-reference them? O’Brien is so hard up to give some kind of reason d’etre for her debacle of a podcast that she will reach for just about anything. Leaving the information that neuters it unsaid.

In fact, Nina Burleigh, Ron Rosenbaum, Lance Morrow, and lawyer Bob Bennett all think that Crump was guilty. Only Rosenbaum gets to voice that on the podcast. Yet, if one adds up all the time the four are on the air, it’s about a third of the show. Also, if O’Brien would have admitted the mythology about “Vivian” and Mitchell, it would have left her with a real problem: Crump has no alibi and there is no other suspect. But the problem is, that leaves the public with “witnesses” like Jim Truitt, Tim Leary, and Damore, about which she conceals all the serious liabilities they have, while turning Meyer and Roundtree into artistic and legal icons.

In 2008, when O’Brien did her special on the death of Martin Luther King, she took the opposite approach. Like Gerald Posner, she was out to discredit the idea that there was a conspiracy to kill King. (Click here for details) She concluded that people just need to think that a small time burglar like James Earl Ray could kill someone as important as King. Now, she takes the other approach: no matter how dubious the evidence, there likely was some kind of a plot to kill Mary Meyer. In both cases, she chose the expedient path. She was so eager to do so in the latter case she was unaware that she hit a new low in journalism.