Martyrs to the Unspeakable – Pt. 2

By James W. Douglass

James Douglass was the only American print journalist in attendance at the entire civil trial in Memphis on the King case in 1999. He was there as a correspondent for Probe Magazine. Court TV was originally going to cover that proceeding, but according to Douglass, they pulled out just a couple of days before. The Memphis Commercial Appeal’s reporter on the King case was not allowed to attend. So he waited each day for Douglass to emerge in order to get the rundown on what happened. The jury in that trial found for the plaintiffs, the King family, against defendant Loyd Jowers. They decided that the King murder was the result of a conspiracy in which local tavern owner Jowers took part. Jim’s report was first published in Probe, and then excerpted in the anthology The Assassinations.

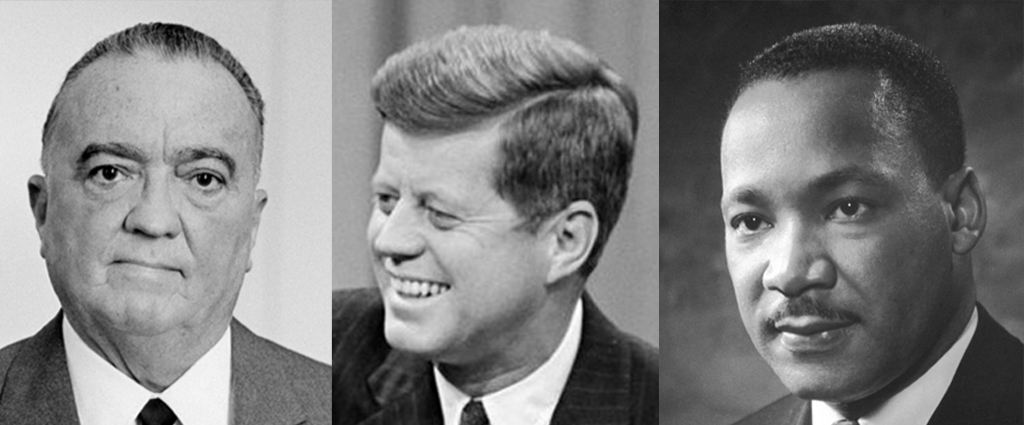

As with Malcolm X, J. Edgar Hoover was obsessed with the so-called rise of a Black Messiah. Therefore, he did everything he could to discredit King. The first charge was that King was really a secret communist who had infiltrators from Moscow amid his entourage. In fact, Stanley Levison was a private businessman who contributed to the CPUSA but had halted his contributions by late 1956. The FBI knew this, and they also knew that his evolving interest was in the civil rights movement. He was now going to turn his fundraising abilities to that cause. So the FBI tried to get him to return to the party as their informant. He turned them down. (p. 141) So Hoover tried another track: Levison was steering the civil rights movement for Moscow.

The other target for Hoover was Jack O’Dell. Again, O’Dell was a former member of the CPUSA who went to work for King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Beginning in 1961, he was an associate editor for Freedomways, an African-American political journal. He was a good office organizer for the SCLC, especially out of New York.

As many commentators–like the late Harris Wofford–have noted, Hoover used these accusations of communist influence to drive a wedge between the Kennedys and King. As Douglass notes, the constant harangue by Hoover to expose King as a pinko with communist influences in his camp was, at least, partly successful. President Kennedy told King that if Hoover could prove he had two communists working for him, “…he won’t hesitate to leak it. He’ll use it to wreck the civil rights bill.” (p. 155). Kennedy had fallen for what was at least partly disinformation on Hoover’s part, and he asked King to jettison both men. The president was very sensitive to what Hoover could do to both himself and King. He said in a private conference, “If they shoot you down, they’ll shoot us down too. So we’re asking you to be careful.” (p. 156) King resisted this request on Levison and left the decision up to him. They decided to keep the relationship on a private basis. In 1963, he asked O’Dell to resign, which he did. But King continued to consult with him occasionally.

What makes this more interesting is that both men fully understood the pressure being brought to bear on all three men: both Kennedys and King. And they understood that whatever they could do for the SCLC, what the Kennedys could do was more important.

II

The problem was that the Kennedys had backed the March on Washington. Which turned out to be a smashing success. (pp. 160-61) This had been preceded by President Kennedy’s June 11, 1963, televised declaration on civil rights, the most powerful statement on the matter by any president since Lincoln. In other words, King’s actions, in tandem with the Kennedys, were becoming very potent on a national level. After a thorough study of the FBI files, writer Kenneth O’Reilly stated that the FBI’s,

…decision to destroy King was not made until the March on Washington demonstrated that the civil rights movement had finally muscled its way onto the nation’s political agenda. (p. 163)

Under even further pressure from Hoover, he got Robert Kennedy to approve a wiretap on the SCLC’s and King’s phones out of Atlanta. Why did RFK agree to do this? The deal was for thirty days. So “If the taps proved King innocent of Communist associations, then the FBI would have to leave him and Kennedy both alone.” (p. 164). The problem was, as RFK’s personal liaison with the FBI, Courtney Evans, noted:

…That the assassination of President Kennedy followed these events reasonably close in point of time, and this disrupted the operation of the Office of the Attorney General. ((p. 165)

If anything, that was an understatement. What happened after JFK’s murder is that Hoover ripped out Bobby Kennedy’s private line to his office. He knew that RFK would not be around very much longer. The rabid racist also knew that his neighbor, Lyndon Johnson, would now allow him much more freedom in his vendetta against King.

On December 23, 1963, a nine-hour meeting was held at FBI HQ to plan an intensive campaign against King. The aim was to use any technique in order to discredit the man. This included planting a good-looking female in his office:

We will at the proper time, when it can be done without embarrassment to the Bureau, expose King as an opportunist who is not a sincere person but is exploiting the racial situation for personal gain…. (p. 165)

The Church Committee adduced testimony that the aim was plain and simple: character assassination. Quite literally, no holds were barred. It was as if King were a dangerous KGB agent. And because Hoover oversaw the Bureau as a monarch, no one dared raise any questions of legality or ethics. It was all made worse when King was named Time magazine’s Man of the Year at the end of 1963. Now, with no one’s permission, the Bureau began to install hidden microphones in the rooms King would stay at on the road. (p. 168). In the spring of 1964, Hoover also got the influential syndicated writer Joseph Alsop to write a communist smear column against King. This was followed a week later by a similar article in the New York Times. (p. 170)

As he had been warned by President Kennedy, who was not around anymore, King immediately suspected Hoover was behind both pieces. At an airport press conference in San Francisco, he pretty much threw down the gauntlet:

It would be encouraging to us if Mr. Hoover and the FBI would be as diligent in apprehending those responsible for bombing churches and killing little children, as they are in seeking out allegedly Communist infiltration in the civil rights movement. (p. 171)

Hoover responded in kind. The tactic now shifted from the Levison/O’Dell angle—which proved to be pretty much a dry well—to the wiretaps and bugs in the hotels. Hoover began this practice at the Willard Hotel in Washington, DC in January of 1964. This campaign was ratcheted up even further when it was announced that King would be given the Nobel Peace Prize for 1964. In other words, one of the highest international honors was being bestowed on Hoover’s beta noire. Hoover retaliated in public against this by calling King “the most notorious liar in the country.” His assistant urged him to qualify that remark as being “off the record”, but Hoover would not. Hoover then doubled down and said King was “one of the lowest characters in the country” and he was being “controlled” by his communist advisors. (p. 173)

III

When King was alerted to this attack, he was on vacation in Bimini, preparing his Nobel Prize address. He replied with:

I cannot conceive of Mr. Hoover making a statement like this without being under extreme pressure. He has apparently faltered under the awesome burden, complexities and responsibilities of his office. (ibid)

That reply initiated the infamous blackmail tape and letter sent to the Atlanta SCLC HQ in late November of 1964. The entire letter was not found until 2014 by Yale historian Beverly Gage, and Douglass prints it in his book. (pp. 174-75) It is six paragraphs long. The letter is clearly complementary to the alleged taping. In the 4th paragraph, it says the following:

No person can overcome facts, not even a fraud like yourself. Lend your sexually psychotic ear to the enclosure. You will find yourself and in all your dirt, filth, evil and moronic talk exposed on the record for all time. I repeat—no person can argue successfully against facts. You are finished. You will find on the record for all time your filthy, dirty, evil companions, male and females giving expression with you to your hideous abnormalities….It is all there on the record, your sexual orgies…This one is but a tiny sample….King you are done. (pp. 174-75)

Toward the end, the letter states: “You are done. There is but one way out for you. You better take it before your filthy, abnormal, fraudulent self is bared to the nation.” (p. 175 ) The FBI mailed it from Miami about five days before Thanksgiving of 1964. But the package sat at the Atlanta headquarters for over a month. It was not opened until after King received his Nobel Prize in Oslo. And it was opened by King’s wife Coretta. She notified her husband, and he and his advisors immediately realized it was from the FBI.

There has been an ongoing debate over two matters in the package. The letter gave King a deadline of 34 days to act. Some believe that, considering when the package was mailed, this would mean Christmas. Others say it was timed for the Nobel Peace Prize honor, which was about two weeks earlier. The second matter was the aim of the package. The SCLC maintained it was for King to take his own life. The FBI, in the person of William Sullivan, who oversaw the composition of the letter, said they wanted King to resign, as they were already grooming his successor, one Samuel Pierce. (p. 169)

Whatever the timing, whatever the goal, King concluded correctly that the FBI was out to break him. Through their surveillance, the FBI knew he knew and told Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach that “King was emotionally distraught and feared public exposure.” (p. 179)

King decided to continue in his efforts, knowing that neither of the Kennedys was now in office and Hoover’s venom was virtually unfettered. He must have felt even more forlorn when Malcolm X was killed the next month. As some have noted, Malcolm was killed just two weeks before President Johnson sent the first combat troops to Vietnam.

IV

Johnson had escalated the war in Vietnam to heights that President Kennedy would have found appalling. By early 1967 there were nearly 400,000 American combat troops in theater. Johnson had activated the air campaign, Operation Rolling Thunder, to complement the combat troops. There ended up being more bomb tonnage dropped in Indochina than had been disposed of during World War II; by a factor of 3-1, the ratio was not even close. The problem was that the bombing campaign inevitably included civilians, since, unlike Germany, Vietnam did not have a highly concentrated industrial base.

In January of 1967, King was looking at a Ramparts magazine photo/essay entitled “The Children of Vietnam”. Many of the pictures showed little children in a hideously burned state. The article was by attorney William Pepper. King then met with him, and Pepper showed him more photos. It moved King to now begin a sustained assault on Johnson’s prosecution of the war. His first speech was in Los Angeles on February 27th, called “The Casualties of the War in Vietnam”. This was followed up by the more famous address at New York’s Riverside Church on April 4, 1967. As Douglass appropriately notes, a year later, King was dead.

There were those—like Ralph Bunche– who advised against King taking on the war. But King thought it was hypocritical to send African-American troops to fight in Vietnam for rights that some did not have at home; and to kill so many innocent civilians along the way.

Another aspect that made King determined to speak out on Indochina was that he had done so in 1965, and then backtracked. At that time, he said that Johnson had a serious problem in this regard because “The war in Vietnam is accomplishing nothing.” (p. 351) About a month and a half later, in April of 1965, he told some journalists in Boston that the United States should end the war. On July 2, 1965, in Petersburg, Virginia, King said that the war must be halted and a negotiated settlement should be achieved. (p. 352). But the SCLC board members did not want King to continue in this vein.

So King instead had a meeting with UN Ambassador Arthur Goldberg in September to voice his concerns and urge Johnson to negotiate a truce. King even suggested that it would be possible to bring the Chinese into the negotiations. Both Goldberg and Senator Thomas Dodd voiced opposition to these types of talks. (pp. 355-57) And Dodd went further by saying King had no knowledge to speak on matters so complex as Indochina, and further, he was undermining Johnson’s foreign policy. King thought Johnson had put Dodd up to this criticism.

As others, Douglass sees King’s decision to return to the Vietnam issue, coupled with the stirrings of the Poor People’s March, as raising his targeting from character assassination to outright elimination. As per the latter, what King ultimately hoped to gain from the Washington demonstrations was the following:

- A full employment program

- Guaranteed Annual Income

- Funding for 500,000 annual units of low-cost housing (p. 310)

King wanted to do in Washington what he did in Birmingham. Through peaceful civil disobedience, he would tie up the city and force its leaders to act on his proposals. But King was going to go even further and unite the two goals:

After we get to DC and stay a few days we’ll call the peace movement in and let them go on the other side of the Potomac and try to close down the Pentagon, if that can he done. (p. 311)

King was now talking about closing down both Congress and the Pentagon. The reader should recall that this is on FBI tapings. As Bernard LaFayette, a coordinator of the Poor People’s Campaign, later said, “You see, the Poor People’s Campaign was clearly economic rights. Now, it’s not low volume; it’s high volume.” (ibid). Or as Vincent Harding, the man who drafted King’s Riverside speech, later said: King was moving in “some radical directions that few of us had been prepared for.” He clearly suggested that this necessitated his assassination. (p. 314)

V

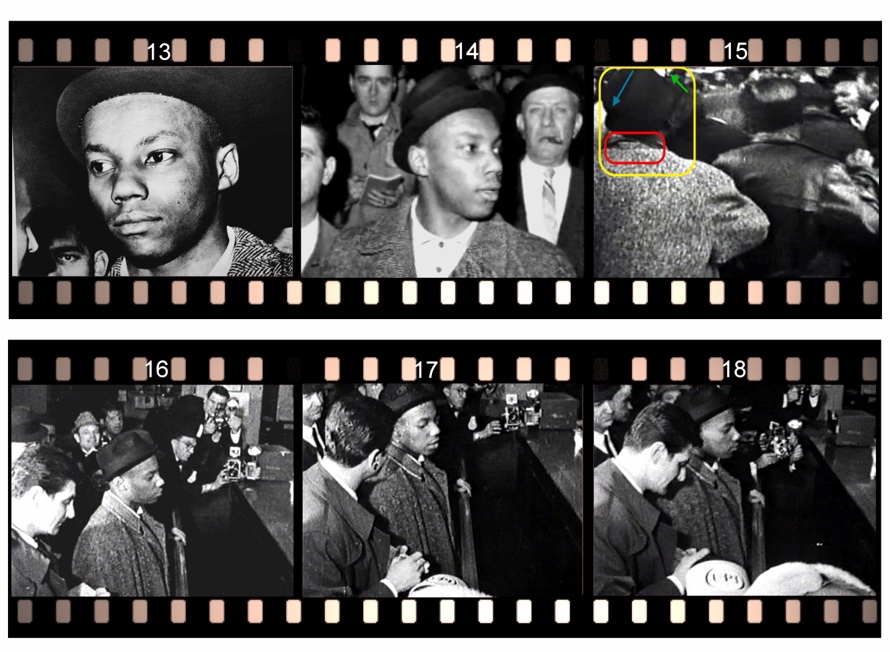

James Earl Ray escaped from prison in late April of 1967. After working as a dishwasher for a couple of months, he stashed enough money to buy an old car and crossed the border to Montreal, Canada. There, at the Neptune Tavern, he met a man he knew simply as Raul. Although Ray had been attacked for creating this character, a witness who testified at the 1999 King trial confirmed it. Seaman Sidney Carthew also met Raul at the same bar. And he saw him with Ray. (pp. 339-40)

As Douglass describes it, Ray’s partnership with Raul ended up being a minor gun-running and drug-smuggling operation. It went from Canada to the USA, particularly California, and then to Mexico, and back to the southern part of the USA, ending with Ray being asked by Raul to go to Memphis and buy a rifle. But it was the wrong one. So Raul ordered him to go back and buy another one. As attorney Arthur Hanes testified at the King trial, it was that rifle which was dropped at the door of Canipe’s novelty shop a few minutes before the actual assassination. And that would be the weapon Ray was charged with in killing King. (p. 340) Even though that rifle was never calibrated for accuracy.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Ray’s journeys after his escape is his use of multiple identities, i.e., Eric Galt, Ramon George Sneyd, Paul Bridgeman and John Willard. As Philip Melanson originally noted, all four lived in a suburban area of Toronto; and within a five-mile radius of each other. But beyond that, three of the aliases—Galt, Bridgeman, Sneyd—approximated Ray’s general appearance, that is, in height, weight and hair color. Further, there is no evidence that Ray had been to Toronto before the assassination of King.

What makes this even more startling is that Ray signed the Galt alias with the wrong middle name of ‘Starvo’, which came from a scrawl Eric used for ‘St. V’, which actually stood for St. Vincent. But here is the capper: “When Galt shortened it to the initial ‘S’ Ray… did the same.” (p. 341) As Douglass concludes, only someone with access to Galt’s security file at Union Carbide, where he worked, could have known about these nuances.

Douglass now moves to the preparations made for the King’s murder. First, King’s normal all-African-American security team was removed the morning of his arrival. The replacement team of caucasian guards was then removed late in the afternoon, about an hour before the shooting. Two black officers from the fire station across the street were reassigned to different stations for that day. The tactical police units around the Lorriane Motel, where King stayed, were moved back earlier on April 4th. The first three negated any security, and the last made it easier for an escape. (pp. 343-44)

Was it even more prepared for than that? The reason King returned to Memphis was because, in his first visit there, about a week earlier, there was a raucous disturbance in the demonstration. That disturbance was caused by the Invaders, an African American youth group modeled on the Black Panthers. (p. 448) A prominent member of that group was Marrell McCullough, who was later uncovered as a police informant and then worked a long career as a CIA officer.

When King decided to return, the FBI then put out a story that on his original visit, he ignored the Lorraine, which was black owned. He had stayed at the Holiday Inn motel, which was white owned. Therefore, King was initially booked into an interior courtyard room at the Lorraine for his return. Someone, no one knows who, had that room switched to a street-level room. It would have been difficult to assassinate King in that first room. The room on the street made it easier. (pp. 448-49)

On the day of the murder, Raul delivered a rifle to Loyd Jowers’ eatery, Jim’s Grill. The back door opened up to a bush area across from the Lorraine. There is a dispute as to where the shot that killed King originated. At least two credible witnesses say it did not come from the flophouse where Ray was booked at. It came from that bushy area, and Douglass agrees with that. But the point remains, those bushes were inexplicably cut down early the next morning. (p. 455)

As the reader can see, there is good reason that the MSM did not cover the Jowers/King trial in 1999. Because they suspected that the King family would win out. Which they did. Jim Douglass does a good job presenting that evidence, which helped Bill Pepper win a judgment.

Next: JFK and RFK are eliminated. Click here to read part 3.