The Incredible Life and Mysterious Death of Dorothy Kilgallen

by Sara Jordan-Heintz

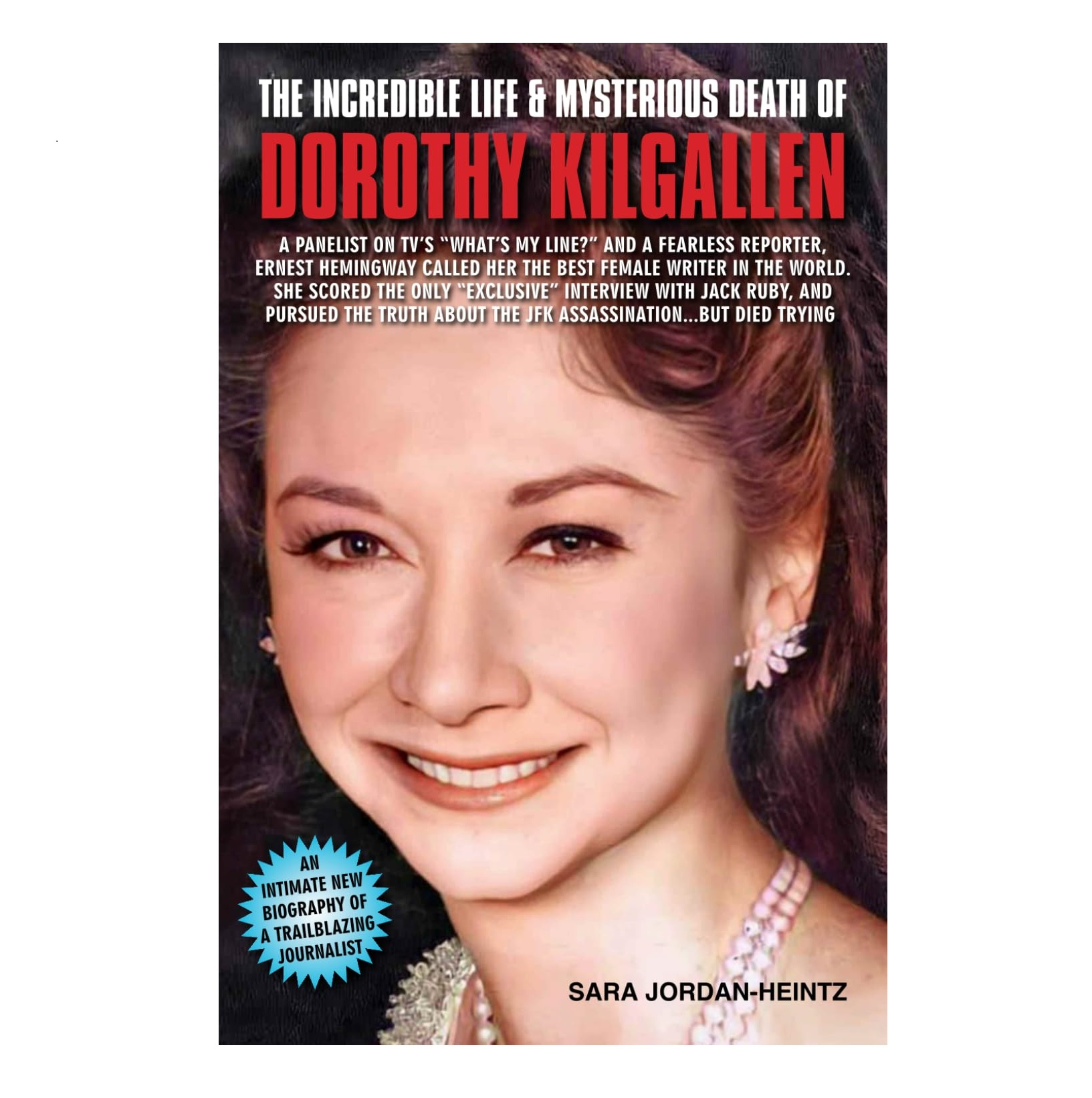

Let us first give the author her past due. In 2007, Sara Jordan wrote a fine article about the demise of journalist and TV personality Dorothy Killgallen for Midwest Today. This was then reprinted in a color online version in 2015, at the 50th anniversary of Kilgallen’s death. (Click here for that version.) That original article was a milestone in the literature on this subject. In this new book, Jordan reveals that she was all of 17 years old when the article appeared (Jordan-Heintz, p. 384) Which makes it the most precocious piece of writing on the Kennedy case since Howard Roffman published his book Presumed Guilty at the age of 22.

The author has now expanded her distinguished essay into a book. At the start, she tries to explain why she did so, strongly indicating the works of author Mark Shaw which followed. She says that although she was glad about the article’s popularity she was:

…dismayed to see Dorothy’s story turn into a cottage industry for one author in particular, whose book, in my opinion, contains reams of repetition, wild theories and self-aggrandizement. Much of his original information came from my article, after he contacted me several years ago requesting an interview. Not all of this is appropriately credited. (p. 1)

If anything this is mild. As I noted in one of my reviews of Shaw’s “cottage industry” books, not only has Shaw tended to discount Jordan-Heintz’ work, but also the woman who Sara got in contact with for her essay, namely Kathryn Fauble. But her (understandable) frustration with Shaw is one of the reasons she decided to write this book.

II

On the night of November 7, 1965 journalist Kilgallen performed as a panelist in her last What’s My Line program. In a belated revelation, her butler and maid, said she came home that night with a man, and they heard the back door closing. This is a bit hard to comprehend since in addition to the Clements couple, James and Evelyn, there were three other men at the townhouse: her husband Richard Kollmar, her son Kerry, and his tutor Ibne Hassan. (Ibid, pp. 4-5) The following morning she was found dead in her home, the cause was a drug and alcohol overdose. Complicating matters was this: her papers for a later book proposal on the JFK case were gone. She had made at least one trip to New Orleans, a second more secretive one, and one to Miami. Charles Simpson, one of her hairdressers—the other being Marc Sinclaire—quoted her as saying the following:

I used to share things with you guys—but after I have found out now what I know, if the wrong people knew what I know, it would cost me my life. And she was dead about nine months later. (Ibid, p. 5)

In addition to a file, and her journeys, she had two interviews with Jack Ruby in person during his trial. She also was in receipt of Ruby’s Warren Commission testimony and she printed this in her newspaper, the Journal American. It was printed over three days and Kilgallen provided a critical commentary (pp. 223-25)

Since this book is a biography, it details Kilgallen’s life from her birth in Chicago in 1913, and the influence of her journalist father in starting her in a career in the newspaper business. A big career boost was the 1936 “race around the world” against fellow reporters Leo Kieran and H. R. Ekins. She lost to Ekins but—at age 23– it was a great publicity machine for her. She became the second woman, after Nellie Bly, to circle the globe. (Ibid, p. 11) It gave her a brief visit to Hollywood, where she acted in a film and sold a concept picture based on the contest, it was entitled Fly Away Baby.

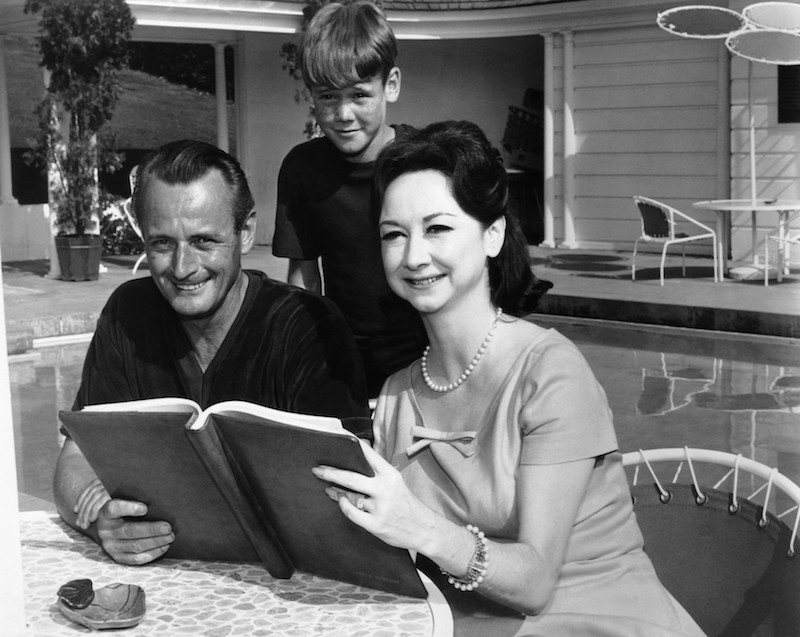

In 1938 she started her famous column, “The Voice of Broadway”. Three years later, based on its success, CBS gave her a radio show of the same name. She did another later radio show with her husband, Richard Kollmar, who was a Broadway producer and actor. After marrying Richard, Dorothy quickly had two children, Richard Jr in 1941 and Jill, in 1943. (ibid, pp. 16-19, she had a third child in 1964 named Kerry.) In 1950 she became a regular on the popular TV show What’s My Line? That game show was broadcast live on Sunday nights. Because she was a triple threat—radio, TV, newspapers– she made a lot of money each year. In 1953 the couple purchased a 13,000 square foot townhouse at 46 E. 68th Street, a block away from Central Park. To demonstrate the kind of money she was making, that townhouse sold for 17 million in 2021. (Ibid, p. 30)

The story that really gave Kilgallen’s career a rocket boost was her coverage of the Sam Sheppard murder case (ibid, pp. 34-35). Sheppard was a doctor in Cleveland who was accused of killing his wife in the summer of 1954. Sheppard insisted he had fallen asleep downstairs and she was killed upstairs by an intruder who knocked him unconscious when he tried to rescue her. Due, in part, to a highly prejudiced press, he was convicted. Lee Bailey eventually took over the appeal process. In a first rate performance Bailey had the conviction overturned, partly because the judge had told Kilgallen, “Well, he’s guilty as hell. There’s no question about it.” And also because the jury was not sequestered as it clearly should have been. The retrial took place in 1966, after Kilgallen’s death. Bailey represented Sheppard at trial and had him acquitted.

Another famous murder she covered was the Tregoff/Finch case of 1959. Dr. Raymond Finch was having an affair with a woman named Carole Tregoff. He wanted to divorce his wife Barbara and marry Carole, but the California community property laws discouraged him from doing so—his wife would have taken too much money and property. Therefore, the couple plotted to kill Barbara. They first tried to hire someone to do it, but he backed out. So they then did the deed themselves at Finch’s West Covina home. Even though the evidence against them was very convincing, there was a mistrial. They were tried again, and inexplicably, there was another mistrial. On the third go round, they were finally convicted. (ibid, pp. 56-57)

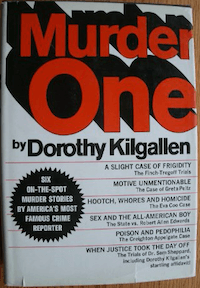

Both of these sensational cases are covered in Kilgallen’s posthumously published book, Murder One.

III

A serious difference between the Jordan-Heintz book and Mark Shaw’s first volume The Reporter Who Knew Too Much, is that this new book spends a lot more time and space on the actual assassination of President Kennedy than Shaw did. And that might be understating things. I would estimate that there is almost as much material on the death of JFK as there is on the mystery of Kilgallen’s demise. But further the author uses much material that is not from the Warren Commission volumes or the Warren Report. It’s an open question as to how much of the 26 volumes that Kilgallen read. But, of course, it would have been impossible for her to have read what did not surface until after her death in 1965. And we can only speculate what she had filed away, since that disappeared after her demise. And no one really knows about her two short interviews with Jack Ruby, since she never revealed to anyone what Oswald’s killer told her.

But, for whatever reason, Sara Jordan-Heintz has decided to place in her book a lot of JFK murder information that did not come out until many years, actually, decades later. To me, it’s fine for her to detail things the doctors saw at Parkland Hospital about the baseball sized hole in the rear of Kennedy’s skull. (p. 90). It’s also fine to quote local reporters Mary Woodward and Connie Kritzberg as to how their work was altered or parts were pulled. (pp. 94-95) Because these were things that happened right then and there, and Kilgallen could have at least theoretically found out about them. But then when the writer states that photos were faked and “it also became shockingly clear there had been alterations to JFK’s corpse by the time the formal autopsy began at Bethesda Naval Hospital that night” we are now getting into areas that it is unlikely that Kilgallen could have even speculated about back in 1965. And I beg to disagree but it is not “shockingly clear” that Kennedy’s body had been altered before the autopsy began. (p. 92). She even goes further than this—shades of Sean Fetter– suggesting that the body was transferred to another casket before Air Force One left Dallas. (p. 98)

This ignores the interview that the late Harrison Livingstone did with Nurse Diana Bowron who actually helped place the corpse into the casket at Dallas. (See the end of the first part of my review of Fetter’s book https://www.kennedysandking.com/john-f-kennedy-articles/under-cover-of-night-by-sean-fetter) For her rather wild concept–and like Fetter–she also relies on the Boyajian Report, although she does not name it, for an early arrival of Kennedy’s casket at 6:35 PM at Bethesda Medical Center.

I don’t know how many times I have to repeat this, but I will keep on doing so as long as I have to. Roger Boyajian and his so called report are not reliable evidence in this case. I have demonstrated this twice before and I now have to do it again. That report does not state that the casket picked up by Roger Boyajian’s detail was Kennedy’s casket. It only refers to it as “the casket”. The obvious question is this: if Boyajian knew it was Kennedy’s casket, would he not have acknowledged that?

Secondly, the report was not signed by Boyajian, and there is no hint as to why he did not sign it. To make matters worse, there is a second page to the report that lists the 10 others in the detail—and none of them signed it either. But even that is not the end of it. For when the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB) interviewed Boyajian about the matter, that is picking up Kennedy’s casket, he could not recall doing so. In fact, he could not recall much about that day–period. Finally, the document the Board had does not appear to be the original. This makes one wonder if it was ever filed with the military. (Harrison Livingtsone, Kaleidoscope pp. 140-46)

To make it even worse she writes that:

There is general agreement among most JFK assassination researchers that the two casket scenario took place and that Kennedy’s body was probed for bullets (which were presumably removed) and surgical procedures done to conceal that he was fired upon by more than one shooter.(ibid, p. 99)

There was and is no such general agreement. In fact, the late Cyril Wecht—a forensic pathologist—never thought such was the case. Neither does Dr. Randy Robertson, neither does Pat Speer, or Dr. Gary Aguilar. At no JFK seminar I have ever attended—from 1991 to 2023—have I ever seen any panel devoted to this subject. The writer who formulated this scenario and wrote a popular book about it —David Lifton—could never make any real headway with it inside the critical community, and he himself admitted that. Its not that he didn’t try, he did. But these attempts failed with rancorous feelings between those involved.

This angle is made worse when she brings in the tall tales about embalmer John Liggett that were first broadcast by the discredited Nigel Turner. (p. 106) Liggett’s brother filed a legal action against The History Channel over these ersatz claims and forced a settlement. (South Florida Sun Sentinel, 3/19/2005) It appears that this bizarre Liggett angle might have been turned up by Billy Sol Estes, a man who sold more baloney on the JFK case than the Hormel company. (See the 2004 book Billie Sol Estes, pp. 155-57)

As I have said many times about the JFK case, we must follow the Sagan rule: Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence. The above does not, in any way, constitute extraordinary evidence. Kilgallen could not have known about them and I doubt if she would have bought into any of them.

IV

I don’t wish to leave the impression that all the many pages Jordan-Heintz devotes to the JFK case itself should be dismissed. That would not be fair or accurate. She does bring in credible evidence of extra bullets being discovered e.g. Randy Robertson’s evidence about Dr. James Young. (See the film JFK: Destiny Betrayed.) She also notes that there are photographic images missing from the autopsy collection, which there are. And her use of FBI agents, Jim Sibert and Frank O’Neill is appropriate. (Jordan-Heintz, p. 119) As is the memo written by Deputy Attorney General Nick Katzenbach. (ibid, p. 121) Her description of the murder of Oswald by Ruby with Captain Fritz breaking formation to allow it is apropos and she mentions the editing out of the horn sounds. (pp. 137-38)

She adroitly shifts to a column written by Kilgallen after the shooting of Oswald. In that piece the reporter said that Kennedy’s assassination was bad enough but now, after the murder of Oswald, people who have never been there feel like they have just witnessed a Texas lynching. (p. 143) She assailed the fact that Ruby was allowed to walk in and out of the Dallas police headquarters, which was supposed to be keeping a security guard around Oswald. She poignantly wrote that the murder of the suspect prevented due process: “When that right is taken away from any man by the incredible combination of Jack Ruby and insufficient security, we feel chilled.” She added, “That is why so many people are saying there is ‘something queer’ about the killing of Oswald, something strange about the way his case was handled, and a great deal ‘missing’ in the official account of his crime” (p. 144) In a mid-December 1963 article she said Ruby may have been allowed access since members of the police force “partied at Ruby’s strip club.” She added that “there were jam sessions at which Dallas cops joined in the fun, some playing musical instruments others doing turns as singers and comedians….” (pp. 164-65)

About a week later, on December 23, she wrote about the upcoming film Seven Days in May.

The producers of the forthcoming film Seven Days in May have every right to think that life imitates art in the most tragic way. Long before President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, they finished their picture about a military group hatching plans to overthrow the President of the United States. In the movie, the ‘secret base” where the plot against the Chief Executive reaches its climax is a place in Texas.(p. 166)

She gives coverage to the Parkland Hospital press conference on the day of the assassination with Malcolm Perry and Kemp Clark. She adds that this conference, added to PR man Malcolm Kilduff’s gesture that the fatal bullet struck Kennedy in the right temple, these undermined the future cover up. She notes that Perry said the anterior neck wound appeared to be one of entrance. Which would eliminate Oswald. (p. 145). Then, apparently based on Barbara Shearer’s documentary, What the Doctors Saw, she writes “that after the news conference, the doctor was accosted by a man in a suit and tie who grabbed his arm and warned him menacingly, “Don’t you ever way that again!” She then adds that this agent was Elmer Moore of the Dallas Secret Service. (ibid)

This appears to be incorrect. From the information that several writers have accumulated—Gary Aguilar, and Pat Speer among them—Moore was on the West Coast on the day of the assassination. On the same day, he was then shifted to Washington for what appears to be a briefing. He was then detailed to Dallas on November 29th. (James DiEugenio, The JFK Assassination: The Evidence Today, pp. 166-67) She is correct about Moore’s assignment being to get the Parkland doctors to change their accounts, and about Moore being a rabid Kennedy hater. She then reinforces this point with the belated revelation by journalist Martin Steadman, namely that Perry revealed to him that he was getting calls during the evening of the assassination to change his statement about a front shot to the neck.

She notes that JFK was trying to forge a rapprochement with Fidel Castro in 1963. But she then adds that Bobby Kennedy had approved a partnership with the Mob to furnish assassins to murder Castro. (p. 151). The CIA Inspector General report on the plots to kill Castro was finally declassified by the Assassination Records Review Board in the mid -nineties. It remains the most definitive and complete accounting of those plots. Right in that report the authors declare that no administration had any knowledge of the plots from their inception to their ending. Which means from 1959-65. (See CIA-IG Report, pp. 132-33) This is why Director Richard Helms kept exactly one copy, the ribbon copy, in his safe. And when President Johnson read it, he concluded that the CIA had a role in Kennedy’s assassination. (Washington Post, December 12, 1977)

V

After many, many pages on the JFK murder, Dorothy Kilgallen finally arrives in Dallas in February of 1964 to cover the trial of Jack Ruby. She wrote a column on February 22.. It began like this:

One of the best kept secrets of the Jack Ruby trial is the extent to which the federal government is cooperating with the defense. The unprecedented alliance between Ruby’s lawyers and the Department of Justice in Washington may provide the case with the one dramatic element it has lacked: MYSTERY. (p. 189)

She then adds a rhetorical question: why has the government decided to supply Ruby’s defense with all sorts of information as long as they do not request anything on Oswald? She continues in this vein:

Why is Oswald being kept in the shadows, as dim a figure as they can make him, while the defense tries to rescue his killer with the help of information from the FBI? Who was Oswald, anyway? (p. 191)

The book then goes into several pages of an Oswald biography. We then refer back to Kilgallen’s comments on his absence at the trial, which the reporter thought was unusual in her experience of criminal trials:

It appears that Washington knows or suspects something about Oswald that it does not want Dallas and the rest of the world to know or suspect….That Lee Harvey Oswald has passed on not only to his shuddery reward, but to the mysterious realm of classified persons whose whole story is known only to a few government agents. (p. 200)

In returning to the trial itself, one of Ruby’s lawyers, Joe Tonahill, told the reporter that Ruby wanted to speak to her. (p. 203) Therefore a brief exchange took place at the defense table. About a month later, Kilgallen asked to speak to Ruby again without the court appointed bodyguards around. The judge granted the request. So Tonahill, Ruby and Kilgallen walked into a small office during the noon recess. Although Tonahill was interviewed about this many years later, he did not offer any specifics, besides saying it was an agreeable conversation. (p. 205) Kilgallen never told anyone about this conversation either.

At the end of the trial, with Ruby convicted, Kilgallen wrote that the whole truth was not told. And that neither the state nor the defense placed all the evidence before the jury. (p. 207). That verdict was later vacated and Jordan-Heintz describes how Ruby passed on before his retrial in Wichita Falls and she does a nice job describing the character and career of Louis J. West, a CIA affiliated doctor who was, inexplicably, allowed to visit Ruby before he passed away in January of 1967. (p. 208)

In July of 1964 Kilgallen published Ruby’s testimony, four months before it would appear in the Commission volumes. Readers were struck by Ruby’s ignored pleas to go to Washington for the interview. She also asked in her commentary: how could Tippit not know Ruby? In another column published in August, she got hold of an internal Dallas Police report and used it to strongly criticize the performance of the police both in the immediate aftermath of the JFK murder and in the transfer of Oswald.(p. 228)

VI

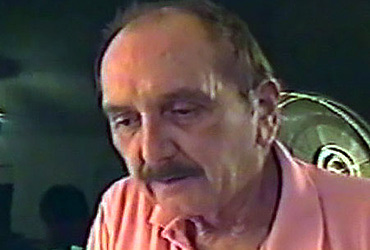

The book closes with the death of Kilgallen. Jordan-Heintz, like Mark Shaw, focuses on the strongest possible suspect, namely the late Ron Pataky, who died in 2022. Lee Israel, the reporter’s first biographer, revealed the affair Kilgallen was having with the much younger journalist from Ohio. Israel did not name him but referred to him as the “Out of Towner”. (p. 242) Jordan -Heintz was the first writer to name him in her Midwest Today article back in 2007.

What follows in the book is a concise biography of Pataky as a Naval ROTC officer at Stanford who was, either kicked out or dropped out, of the university in April of 1955. (p. 243) He was using fake ID cards and was arrested. He then transferred to Ohio State and graduated in 1958. He eventually got a job as an entertainment writer for the Scripps Howard chain, at the Columbus Citizen Journal until it folded in December of 1985. Pataky was also a poet and songwriter.

By the time Pataky met Dorothy he was married and divorced. He appears to have been quite the ladies man. The book features pictures of him with actresses Sandy Dennis and Alexis Smith. He also had an affair with singer Anna Maria Alberghetti. He and Kilgallen met while on a film press junket to Europe. (pp. 247-48) Although Pataky maintained that their relationship was Platonic and not sexual, there is evidence that such was not the case. (p. 251) The author juxtaposes his budding relationship with Kilgallen and her doing more work on the JFK case. For instance, in late September of 1964, she revealed that witnesses who did not identify Oswald at the scene of the murder of Patrolman J. D. Tippit were told to be quiet.

The author notes that Kilgallen did report on the kindly Quaker couple, Ruth and Michael Paine and their incriminating comments about Oswald. She also notes a fascinating piece of information I had never encountered before. In commenting on the Roger Craig testimony about Oswald jumping into a Rambler station wagon after the assassination, she says that Ruth Paine’s station wagon was a Chevy. But that someone who did own a four door Rambler station wagon was New Orleans businessman/CIA agent Clay Shaw.

He insured the Dallas-based vehicle (buying only the required liability policy) through an out-of-town agency for his “son” (though he didn’t have one), then canceled the policy after the assassination and presumably disposed of the vehicle. Correspondence from the insurance agent confirms all this. (p. 261)

Quite intriguing if its accurate.

During the last year of her life, the reporter made few if any newspaper references to the JFK assassination. But according to more than one source, she was still at work on the Kennedy case. And she was arranging a second visit to New Orleans. She was going to meet with a source that she did not know, but would recognize. Ron Pataky said that the man she met with was Jim Garrison. (pp. 317-18) But further, Pataky said that he had met with Garrison, two weeks after he had previously met with Mark Lane. And, according to Pataky, he met with Lane before the reporter did. The author suggests that this shows that Pataky was likely on assignment during his days with Kilgallen.

On the evening of her death, Kilgallen was seen at the Regency, her favorite hotel bar, after midnight with a male companion. Pataky says it was not him and that he only talked to her by phone in that 24 hour period. (p. 329) One of the weirdest dichotomies about her death is that the butler, James Clement, maintains that he found her body in the bathroom. (p. 333) But hairdresser Mark Sinclaire said he first found her body in the third floor bedroom, where she never slept. Jordan-Heintz tries to address this paradox in the evidence. She asks, just what happened between the hours when Clement says he saw the body and when Sinclaire discovered it in the bedroom. Clement also said that men in suits carted off her files. (p. 338)

Lee Israel noted that the police did next to nothing about this case. They should have interviewed everyone she talked to the night before, but there is no evidence they did so. But Pataky said he actually was interviewed. (p. 339)

The book closes with the very odd circumstances of Kilgallen’s autopsy. The official version was she died of “acute barbiturate and alcohol intoxication, circumstances undetermined.” (p. 350) But the man who did the autopsy, did not sign the death certificate. And the person who signed was not even stationed in Manhattan, where she died, but in Brooklyn. It also turned out that there was evidence of Nembutal on her drinking glass, a drug which she had not been prescribed (she had only been prescribed Seconal). There was also evidence of a third drug in her system: Tuinal. The chemist who did the drug testing said he was told by his superior to keep the case under his hat because it was big.(pp. 351-52)

The book tries to place Pataky in New York on the night Kilgallen died. The author bases this on the fact that his paper ran his review of the film The Pawnbroker two days later. But according to IMDB, that films was released in April, six months prior. So although this is suggestive, it is not probative of Pataky being in New York at that time.

The mystery of Kilgallen’s death continues. The incompetence, or indifference, of the authorities was simply astounding.

The above question is posed by author Mark Shaw in his new book, The Reporter Who Knew too Much. But for anyone interested in the JFK case, the questions about Kilgallen’s death are not new. Investigators like Penn Jones and Mark Lane first surfaced them in fragmentary form decades ago. And according to more than one report, Lane was actually communicating with Kilgallen when the latter was doing her inquiry into the JFK case from 1963 to 1965. This reviewer briefly wrote about her death in a footnote to the first edition of Destiny Betrayed. (See page 365, note 15) With the rise of the Internet, various posters, like John Simkin, kept the Kilgallen questions popping up on Kennedy assassination forums.

The above question is posed by author Mark Shaw in his new book, The Reporter Who Knew too Much. But for anyone interested in the JFK case, the questions about Kilgallen’s death are not new. Investigators like Penn Jones and Mark Lane first surfaced them in fragmentary form decades ago. And according to more than one report, Lane was actually communicating with Kilgallen when the latter was doing her inquiry into the JFK case from 1963 to 1965. This reviewer briefly wrote about her death in a footnote to the first edition of Destiny Betrayed. (See page 365, note 15) With the rise of the Internet, various posters, like John Simkin, kept the Kilgallen questions popping up on Kennedy assassination forums.