Larry Crafard – The Leads the Warren Commission Lost – Part 2

By John Washburn

LEAD V

Crafard’s alibi for November 22

Crafard, when interviewed by the FBI on November 29, 1963, claimed he was sleeping at the Carousel Club during Kennedy’s assassination on November 22. He stated he overslept and was awakened by a phone call from Armstrong at 11:30 am and then again in person between 12:30 and 12:45 pm.

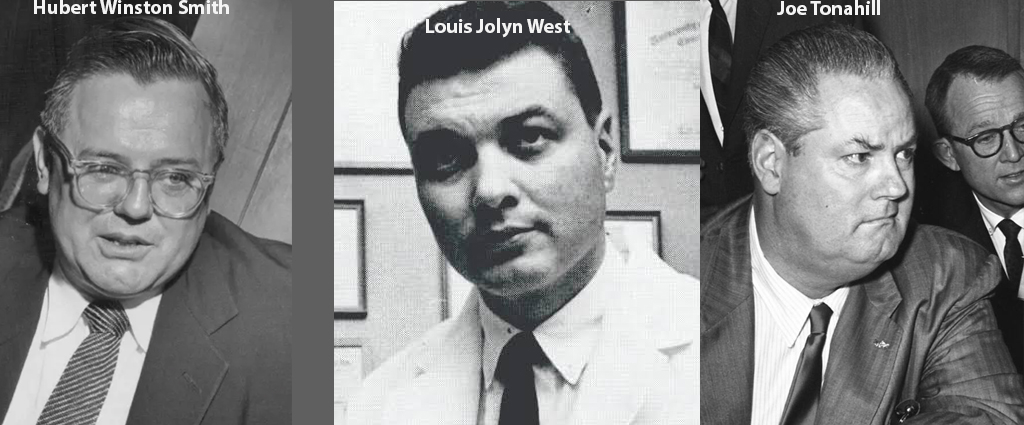

With Ruby detained for Oswald’s murder, Andrew Armstrong managed the Carousel Club. An African American who handled the bar and cash takings, Armstrong was interviewed by FBI Agents Lish and Wilson on November 25, 1963 (CE5310-A). His testimonies are consolidated as CE5310 A-G here.

That first interview focused on Jack Ruby, his reactions to Kennedy’s assassination, and a list of club employees. Crafard was not mentioned.

Agent Lish (CE5310-B) visited Armstrong again that day, and Crafard was of interest, likely after Patterson’s lead. The second interview revealed Crafard had left on Saturday, and his whereabouts were unknown. But Armstrong found and handed over Crafard’s notebook, entered into evidence as CE5230. A typewritten transcript of it was made on November 27, which is on file but not included in the Commission’s evidence.

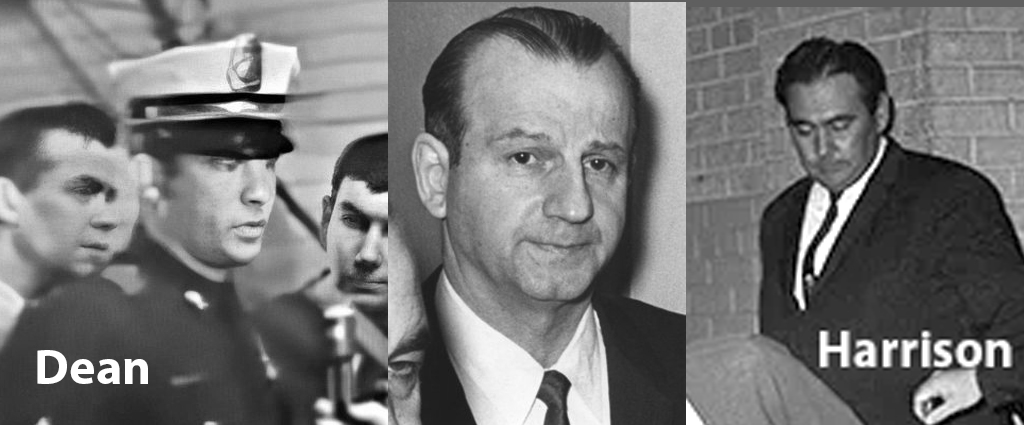

FBI Agents Peggs and Zimmerman then made a third visit on November 26 (p.288 WC files, no exhibit). Because Armstrong had found a letter from Crafard’s cousin, Gail Cascadden, which listed her address as Box 303, Harrison, Michigan. Page 288 includes the notebook transcription and a typed copy of Gail’s letter. It was that letter which enabled the FBI to trace Crafard to rural Michigan, where he was found on November 28.

Only on January 23, 1964, to Agents Sayer and Clements (CE5310-G), did Armstrong provide an alibi for Crafard regarding November 22, 1963. But Armstrong did not then (nor ever) mention Crafard’s claim of being awakened at 11:30 am.

Armstrong’s improbable journey

Armstrong lived at Dixon Circle, Dallas, over 4 miles due east from Downtown.

Armstrong testified on April 14, 1964, that his regular working hours were from 1:00 pm to 1:00 am, and he typically left home at noon to catch the bus from Dixon Circle to Downtown. That would have been the 12/50 bus route along Scyene Road (Dallas City bus map). Armstrong said that he usually unlocked the club just before 1:00 pm and stocked the refrigerator so that the beers would be cold later in the day.

In his January 23, 1964, FBI statement, Armstrong said that on November 22, 1963, he boarded a bus near his home at 11:53 pm, arrived at Main and Akard at 12:25 pm, missed the motorcade, but saw it was west at Main and Lamar before walking to the Carousel, arriving at 12:30 pm. The Carousel Club was on Commerce near Field, one block south of Field and Main. It would be a 2–3-minute walk from Main and Field to the Carousel.

He said he took his jacket off and went to the men’s room. When he left there, he said he was curious about hearing sirens and hence got a transistor radio and listened to KLIF Dallas. Then he heard the President had been shot and tried to wake Crafard, but Crafard did not wake. He listened for two minutes more, then heard the President had gone to Parkland. Then he woke Crafard.

He said that 15 minutes later, Ruby called from the Dallas Morning News and asked, “Had he heard the news?” He then said if “anything happens to Kennedy, the club will close.” He carried on listening until the announcement that Kennedy was dead at 1:30. He said Ruby arrived at 1:45-2:00 pm. Ruby said “what a terrible thing,” and the club would close for 3 days. Ruby made calls. Then he heard the announcement of the death of Tippit. (CE5310-G p320.)

If Armstrong was on a westbound bus on Main Street, missing the motorcade but still seeing part of it further down (by his description, three blocks down), then there is a very narrow time window in which his arrival can have occurred.

The Motorcade – running 5 minutes late – entered Main Street at Harwood (at City Hall) at 12:25 pm and was at Field and Main at 12:27 pm, Main and Houston at 12:29, and Kennedy was assassinated on Elm at 12:30 pm.

If Armstrong was on a bus ahead of the motorcade, he would have observed the entire event. So, to have just missed it, Armstrong would have had to have arrived on Main immediately after the motorcade had, approximately 12:26 pm. But when he testified to the Commission, he claimed to have arrived at the Carousel at 12:15-12:20 pm. That places him at least 5-10 minutes ahead of the motorcade, and he wouldn’t have missed any of it.

Further, if Armstrong could get from Dixon Circle to Main Street on a noon bus that could get him to the Carousel that quickly, then, on a normal working day, he would be arriving over half an hour too early for his 1:00 pm arrival. Added to which a noon bus from Dixon Circle would be hard pushed to arrive on Main in 20 minutes, even in normal day traffic conditions.

But Armstrong then undermined his account even further. He testified he got up at 9 am, took the noon bus to see the parade, and stopped at Moore’s Barbers on the way. Merely adding the haircut time would have made it impossible for him to reach Main Street until well after 12:30 pm.

The Dallas City Directory shows there were two Moore’s Barber Shops, 1124 S Haskell and 1125 Stonewall. Both of those were several blocks north of the Scyene bus route, a ten-minute walk. That detour would add an extra 20 minutes.

This is what Armstrong said to the Commission about the barbers.

Mr. HUBERT. And you got to the club about what time?

Mr. ARMSTRONG. It must time been about 12:15-12:20, or something like that, because when I got downtown I could see portions of the parade, you know, like I got off of the bus at Main and Field- at Main and Akard, I’m sorry, which is the usual stop, I always get off at Main and Akard, and further down you could see portions of the parade, but I felt that I had missed the parade I didn’t realize that I had missed the parade until I was in the barber shop and thought, well, maybe I’ll get downtown, I said to myself, and I will see some portion of it, but when I got downtown I was surprised to see that the parade had moved forward – further down.

Anyone who’d left home at noon and intended to stop by the barbers shouldn’t have been the least bit surprised. With the motorcade scheduled for 12:20 pm on Main, he could not have made it.

Crafard and the sleep story

Hubert asked Armstrong if he had called Crafard to wake him up (Crafard’s 11:30 am call claim). Armstrong said no and added that he didn’t usually wake him even if he was asleep upon arrival.

Armstrong’s account of the events at the Carousel Club was also inconsistent. On January 23, 1964, he told the FBI that he went to the restroom when he heard sirens and learned of the assassination via a transistor radio. He ran to wake Larry, found the door open, but despite his efforts, Larry fell back asleep. Armstrong then returned to the restroom without waking Larry.

Gary DeLaune, a news anchor at KLIF radio in Dallas, Texas, was the first to break the news at 12:40 pm. CBS-TV, with sound only, started at 12:45 pm. WFAA Dallas started live TV at 12:45 pm with Bill and Gayle Newman, the closest civilian eyewitnesses to the fatal shot to Kennedy’s head.

Armstrong then said he heard further reports, and 2 minutes later, he went to wake Larry up, and this time, Larry got up and dressed.

That places Armstrong in the restroom from 12:15 pm to 12:40 pm on one account (for the Commission) and 12:30 pm-12:40 pm on the other (for the FBI).

However, Armstrong’s inconsistent and impossible ‘alibis’ for Crafard were blown apart by Crafard himself when he testified in Washington on 8th, 9th and 10th April 1964. WC Vol XIV.

Crafard was actually an early riser.

Mr. HUBERT. Do you drink much?

Mr. CRAFARD. Very seldom. I drank, I think, three or four different times while I was there that I drank a beer or two, that was all.

Mr. HUBERT. So that your heavy sleep on the morning of the 22d couldn’t be attributed to the fact that you had a hangover?

Mr. CRAFARD. No.

Mr. HUBERT. Or that you were suffering from any overindulgence in alcohol?

Mr. CRAFARD. No, sir.

Mr. HUBERT. You don’t take any kind of sleeping pills or anything like that?

Mr. CRAFARD. No, sir.

Mr. HUBERT. So this was just normal sleep?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. HUBERT. And his call failed to wake you?

Mr. CRAFARD. I left the 23d of November, I believe it was.

Mr. HUBERT. What were your hours there?

Mr. CRAFARD. Any hours. I would just get up, I usually got up about 8 o’clock in the morning and I would be lucky if I would get to bed before 3:30, 4 o’clock.

Mr. HUBERT. How come you would get up so early?

Mr. CRAFARD. Get the club cleaned up.

Mr. HUBERT. Wasn’t there a man to help?

Mr. CRAFARD. I took care of that mostly myself

Mr. CRAFARD. If I started cleaning up at 9 o’clock I would be finished by 11:30.

Mr. HUBERT. In other words, you had 2 1/2 hours?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. HUBERT. Were you then usually free?

Mr. CRAFARD. No. Jack would come in about 11:30 and be there 2 or 3 hours. After he left I had to stay there and answer the phone.

Mr. HUBERT. What was the purpose of keeping you around the club after your cleanup job was over?

Mr. CRAFARD. So far as I understand just mostly answer the phone.

Mr. HUBERT. Were there many phone calls to be answered?

Mr. CRAFARD. There was quite a few that would come in–generally, usually, people calling in, would start calling in about 1 o’clock for reservations.

The cold beer story

Then, contrary to Armstrong’s account of leaving home at noon on November 22, 1963, Crafard’s testimony put Armstrong arriving at the club at 9:30 am.

Mr. CRAFARD. Andy woke me that morning. He come in early. Andy always put the beer in and he come in early to do that so that he could have the rest of the day off.

Mr. HUBERT. What time did Andy come in?

Mr. CRAFARD. I think it was about 9:30 or something like that.

Mr. HUBERT. Came in personally?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes. He was there when the President was shot.

Mr. HUBERT. Were you asleep when he came in?

Mr. CRAFARD. I was asleep when he came in.

Mr. HUBERT. Did you waken up when he came in?

Mr. CRAFARD. I didn’t wake up—Andy woke me up and told me that the President had been shot.

There seems to be some confusion here. And Hubert should have clarified it. Because if Armstrong came in that early, he could not have told Crafard about the JFK murder. Jack Ruby did little to help.

Ruby on June 7, 1964, told the Warren Commission party at the jail, regarding his actions when he was at the Dallas Morning News: “I could have called my colored boy, Andy, down at the club. I could have-I don’t know who else I would have called, but I could have. Because it is so long now since my mind is very much warped now.”

If Crafard was at the club and Armstrong was having a half day, then Ruby would have expected to have called Crafard. Did Ruby think that Crafard was not going to be there?

Crafard didn’t even sleep at the club towards the end

Stripper Karen Carlin ‘Little Lynn’, who testified before Hubert on April 15, 1964 (WC Vol XIII), said Crafard did not sleep at the club. She said she worked at the Carousel for 2 months before the assassination, to the end of December 1963, and she worked 7 days a week.

Mr. Hubert. Do you remember a man that stayed there and slept on the premises?

Mrs. Carlin. No; I don’t know of anyone that did. Andrew was the only one I knew that ever spent the night there, and that was just because he would say so the next evening. He said, “I am tired.” He said, “I had to stay here all night.”

Mr. Hubert. I might add that this man Larry’s full name was Curtis Laverne Crafard.

Mrs. Carlin. Yes. That was a little young boy, the one that worked the lights.

Mr. Hubert. He stayed on the premises?

Mrs. Carlin. Yes. But he stayed next door most of the time. I know he was sleeping there for a while, but Jack put a stop to it.

Mr. Hubert. You mean Jack wouldn’t let him sleep in the club?

Mrs. Carlin. Jack didn’t like him sleeping there, because there was too many things gone.

Mr. Hubert. Then he made him go next door?

Mrs. Carlin. He went next door. I don’t know who was next door or what it was next door, but he went next door.

Mr. Hubert. But what you heard was that this man had, Crafard, Curtis Laverne Crafard had been staying on the premises, but that Jack had put a stop to it and made him move to some place next door, but you don’t know which next door?

Mrs. Carlin. Yes.

Mr. Hubert. Who did you hear this from?

Mrs. Carlin. It was from Larry. He was taking care of the dogs or something.

Mr. Hubert. He told you he had to move out?

Mrs. Carlin. Yes.

Mr. Hubert. Out of the premises altogether?

Mrs. Carlin. No. He just said, “I am going to have to move. I can’t stay here. I don’t know where I am going to get the money, but I am going to have to move.”

Mr. Hubert. That must have happened just before the assassination of the President?

Mrs. Carlin. Yes. After that I didn’t see Larry no more.

Mr. Hubert. So to your knowledge he never did actually move, but just said he was going to have to move, and he informed you that Jack had told him he would have to move?

Mrs. Carlin. Yes.

Mr. Jackson. When you say move, you mean move out at night and not sleep there?

Mrs. Carlin. Yes.

Mr. Hubert. That is what I meant, to move next door, I think is what you meant?

Mrs. Carlin. Yes.

(The Jackson who interjected was her attorney.)

In her FBI statement of November 26, 1963, taken at the Carousel Club to agents Peggs and Zimmerman (Tuesday) CE5318, Carlin said that she’d last seen Ruby at the club the night before the assassination.

By all that, Carlin didn’t see Crafard at the club after he’d moved out of it, and that was before the assassination.

“Next door”, may have been the Colony Club. Crafard’s not being at the Carousel Club would be due to his working at the Vegas Club near Lucas B&B, which is where he was seen by Mary Lawrence, as confirmed in Crafard’s November 28, 1963, FBI statement. But Crafard, when he testified, left out any mention of working at the Vegas Club before the assassination.

Mr. CRAFARD. I have tried to think of what I was doing before, the night before [the assassination], a couple nights before, or something like that. I don’t recall anything out of the ordinary.

Mr. HUBERT. If it was the ordinary, then I suppose it would have been that the club closed up at its usual hour.

Mr. CRAFARD. As far as I recall, yes.

Mr. HUBERT. And you were still sleeping there?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes; I was still sleeping there.

Mr. HUBERT. So you would have gone to sleep?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes, sir.

Mr. HUBERT. And then I suppose Ruby would have wakened you?

Mr. CRAFARD. Andy woke me that morning. He come in early. Andy always put the beer in and he come in early to do that so that he could have the rest of the day off.

Was Armstrong trying to give Crafard an alibi? But in doing so, Armstrong got tied in knots and created a highly improbable travel time scenario for himself, which Crafard himself seemed confused about.

Armstrong testified at Ruby’s trial in March 1964 and told the Warren Commission he spoke with Crafard, who also testified for Ruby, in a courtroom corridor. That brief interaction likely did not give them time to align their stories.

Crafard and the TV

Crafard claimed to be watching TV after the assassination. Hubert tested him.

Mr. HUBERT. It was a Dallas station or a Fort Worth station?

Mr. CRAFARD. It is one there they call the Dallas-Fort Worth, WWTV12, I think it is.

Mr. HUBERT. KLRD, is that what it is?

Mr. CRAFARD. I don’t know what station it is. I am not sure whether it was WWTV.

Mr. HUBERT. How long did you stay there watching?

Mr. CRAFARD. We turned it up real loud where we could hear it and then listened to his radio, too, where we would hear both of them.

Mr. HUBERT. Go ahead, what happened next?

Mr. CRAFARD. I don’t recall exactly what was said except the fact that the President had been shot.

Mr. HUBERT. How long did you continue to watch it?

Mr. CRAFARD. We watched it right up until–most of the day, I think, we had the television on there, then, most of the day.

A remarkably vacant memory for some very eventful testimony by, for example, Bill and Gayle Newman, taking up much of the coverage.

In CE2430, a very late interview with the FBI on August 27, 1964. Crafard stressed that he was with Ruby when they both heard of the death of Tippit – by name – and the death of Kennedy.

However, Kennedy’s death was announced at approximately 1:35 pm by TV and around 1:25 pm by radio. There was no announcement of the death of Tippit by name before Oswald’s arrest at the Texas Theatre at 1:50 pm. Indeed, by 2:00 pm, the DPD radio tapes show that Tippit’s wife had not been told.

Whereas Armstrong in his FBI interview of January 23, 1964 CE5310-G says, correctly, that the name of Tippit didn’t appear until after the official announcement of the death of Kennedy. He said Ruby arrived 15-20 minutes after the official announcement of that, and then made one or two phone calls in about 5 minutes. It was after this, when KLIF mentioned the names of Tippit and Armstrong, he said that Ruby told him he knew Tippit. There is no mention of Crafard.

LEAD VI

Crafard and the police badge

There is also this detail in Karen Carlin’s FBI statement,

“She said that LARRY attempted to impress her by showing her a badge and telling her that he was a policeman.”

In my “Death of Tippit article, I suggested that Tippit was waiting at Gloco, the end of the Houston Street Viaduct, to pick up whoever was on the Beckley bus, acting out the narrative that it was the way Oswald was making a getaway from Downtown. When Oswald most likely had actually been driven to the Theater in a Rambler.

It is also important to remember why Karen Carlin was asked to testify. She was a key witness for the official line that it was her telephoning Ruby for her wages that caused him to be at Western Union opposite City Hall at 11:15 am on November 24 (Sunday), where he then happened on the transfer of Oswald.

However, she actually said two things contrary to that line. She testified that Ruby said on Saturday, November 23, 1963, “I don’t know when I will open. I don’t know if I will ever open back up. And he was very hateful.”

That seems to suggest premeditation by Ruby, perhaps having an inkling of the consequences of what he was going to do next, to Oswald.

Also, when she testified to the Commission, she said that Ruby had said to her on the telephone on the morning of November 24 (she in Fort Worth, he at his apartment on South Ewing), “Well I have to go downtown anyway”.

Ruby himself, when he testified after his trial, said. “So my purpose was to go to the Western Union–my double purpose but the thought of doing, committing the act wasn’t until I left my apartment.”

Having a ‘double purpose’ in going to Western Union also indicates premeditation.

LEAD VII

The incredible journey. How did Crafard get to Michigan?

Crafard said he took Routes 66 and 77, passing by Oklahoma City, St Louis, MO, then the outskirts of Chicago, IL. From there to Lansing, MI, Mount Pleasant and then Clare, MI, where he arrived at 9:00 pm on Monday, November 25, and stayed with his cousin, Clifford Roberts. A total distance of 1,282 miles.

Crafard said that the 59-hour trek began when he decided to leave Downtown Dallas at 11-11:15 am on November 23 (Saturday). He had only $7 on him, he was carrying two bags, and he walked 15-18 blocks until he hitched a ride.

Remarkably, he said the first ride was from a person he knew from the State Fair, but did not know his name.

Mr. HUBERT. Did you walk there?

Mr. CRAFARD. I walked out about 15 or 18 blocks, I think it is, and a guy I had met out at the fair picked me up. He saw me.

Mr. HUBERT. Did you arrange for him to pick you up?

Mr. CRAFARD. No; he was going by, he saw me, and he recognized me.

Mr. HUBERT. What is his name?

Mr. CRAFARD. How’s that?

Mr. HUBERT. What is his name?

Mr. CRAFARD. I don’t remember what his name is. He worked out there for a while. I never did know his name. I don’t think he knew my name. He recognized me as having worked out there.

Mr. HUBERT. You were on the highway hitchhiking at that time?

Mr. CRAFARD. That’s right.

Mr. HUBERT. Did you have a bag?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. HUBERT. How large was it?

Mr. CRAFARD. It was a regular satchel and I had another bag

Hubert elsewhere displayed incredulity about the tale of rides and the fact that Crafard said he had $7 on leaving Dallas. But he still had $3 left when he left Clare on Tuesday to go to Harrison. –This was to visit his aunt Esther Eaton and cousin Gale Cascadden – where he stayed the Tuesday night and then hitched to Kalkaska (another 85 miles) to stay with his sister Cora Ingersoll, Wednesday night. It was there that he was traced by the FBI, and he was interviewed on the 29th ( the day after Thanksgiving), in the morning at nearby Bellaire, MI.

Assuming that the first ride from Dallas was around noon, with Crafard saying he arrived in St Louis around 6:00 am on Sunday, then that was 705 miles in 18 hours, averaging 39 mph.

Then he said he did St Louis to the Chicago outskirts. I measure that distance as Country Club Hills, where the road bears to Michigan, at about 284 miles. He told Hubert he arrived there at 2 pm on Sunday. That’s 8 hours, averaging 35.5 mph and the whole Dallas to Chicago journey averages 37.6 mph. After that, his description of getting from the Chicago outskirts to Clare breaks down as: to Lansing, 212 miles, then Mount Pleasant, 69 miles and then Clare, 16 miles, arriving 9 pm, Monday.

That’s 31 hours, averaging 9 mph. Had he averaged 35 mph, he could have done it in 8 hours. But Crafard did not describe any long stops, sleepovers, or waits for lifts. He described near continuous travel. Hubert picked up that the final 16 miles from Mt Pleasant to Clare, according to Crafard, took 12 hours.

Mr. HUBERT. Then there is some mistake in timing of about 12 hours.

Mr. CRAFARD. That is what I was saying. I’ve lost some time there

Mr. HUBERT. It may be that you are making a mistake, Larry. Let’s see if we can’t refresh your memory from the time you got that last long hitch that took you to Mount Pleasant because you remember getting to Mount Pleasant at night, about 8:30.

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. HUBERT. And that, you say, is a run of what–about 5 hours, 6 hours?

Mr. CRAFARD. I don’t believe it would take that long.

Mr. HUBERT. So if you got there at about 8:30 at night, then either you didn’t get any hitches for a long period of time, or else something else happened.

Mr. CRAFARD. I’m just trying to—-

Mr. HUBERT. Because you told us, and if it is not so, why we want you to correct it. Everybody can make mistakes.

Mr. HUBERT. You said that you picked up this ride at a point 60 miles outside of Lansing and into Mount Pleasant prior to dawn on the 25th. Now, maybe that is wrong. Maybe you got that ride late in the day. Let’s put it this way. Was that a continuous ride straight on?

Mr. CRAFARD. It carried me straight on through to Mount Pleasant.

Mr. HUBERT. Did you stop at all?

Mr. CRAFARD. Not that I can recall. It isn’t that long a run across there.

Mr. HUBERT. Did you stop for lunch or anything of that sort?

Putting all into context. Crafard got from Dallas to the Chicago end of Lake Michigan in 1 day 2 hours, 77% of the distance. But he took 1 day, 7 hours to travel 23% of the trip, within Michigan itself. Hubert spotted that the most egregious time discrepancies occur from when he said he missed Chicago by bypassing it.

Mr. HUBERT. He didn’t take you through Chicago?

Mr. CRAFARD. No; I bypassed most of Chicago.

Mr. HUBERT. How did you do that?

Mr. CRAFARD. On a couple alternate routes.

Mr. HUBERT. With hitchhikers?

Mr. CRAFARD. Different rides.

Mr. HUBERT. Different rides?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. HUBERT. How many?

Mr. CRAFARD. I got three or four different rides in Chicago.

Mr. HUBERT. With these several rides around Chicago, bypassing it, how long did it take you to get around Chicago?

Mr. CRAFARD. Probably 2 or 3 hours.

Mr. HUBERT. And these were all short ones?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

We can almost see Hubert raising his eyebrows.

When did Crafard hear Ruby had shot Oswald?

Ruby shot Oswald on live TV at 11:21 am on Sunday. By Crafard’s described journey, Oswald was shot when Crafard would have been heading to Chicago; then he had 3-4 rides bypassing it, then he took the one to Lansing. That is 5-6 rides, with the opportunity to hear the radio news of the big story, or any of the drivers commenting on it if they’d already heard it.

Earl Ruby testified (Vol XIV) that he heard at noon that day, whilst on a phone call, that Oswald had been shot. He turned on the radio and, within 10 or so minutes, learned that his brother Jack had done it.

Therefore, anyone first hearing of the shooting after 12:30 pm on Sunday, November 24, 1963, would know that Oswald was shot, and Ruby had done it. To know the former but not the latter could only have occurred early, between 11:21 am and 12:30 pm.

So, when did Crafard say he heard that Oswald was shot, and Jack Ruby was the person who did it?

Mr. HUBERT. When did you first hear that Oswald had been shot?

Mr. CRAFARD. I had heard that Oswald had been shot Sunday evening.

Mr. HUBERT. Where?

Mr. CRAFARD. It must have been while I was getting through Chicago.

Mr. HUBERT. Where did you hear that?

Mr. CRAFARD. Over the radio.

Mr. HUBERT. What radio?

Mr. CRAFARD. The car radio.

Mr. HUBERT. Did you know that Ruby had done it?

Mr. CRAFARD. No; I didn’t find out who had done it until the following Monday, the following morning, Monday.

Mr. HUBERT. Where did you find that out?

Mr. CRAFARD. I heard that over the radio.

Mr. HUBERT. As a matter of fact, Larry, I suppose all of those cars you were in had radios, didn’t they?

Mr. CRAFARD. A lot of people don’t listen to the radio when they are riding like that. That was the first I’d heard of it—was Sunday evening, the first I heard Oswald had been shot.

Mr. HUBERT. Sunday afternoon, wasn’t it?

Mr. CRAFARD. How is that?

Mr. HUBERT. You said it was while you were working your way through Chicago.

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. HUBERT. Which took you two or three different cars; about 2 hours or so?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. HUBERT. It was in one of those that you heard it?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. HUBERT. There was no announcement that Ruby had done it?

Mr. CRAFARD. I don’t believe so, because I didn’t know Ruby had done it until Monday morning.

Mr. HUBERT. How did you find that out?

Mr. CRAFARD. I heard that over the news.

Mr. HUBERT. In a car?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. HUBERT. During the night when you were driving from Chicago to Lansing, during the period from 5 in the afternoon to about midnight, didn’t you hear any radio announcements about any of this matter?

Mr. CRAFARD. No.

Mr. HUBERT. Did that car have a radio in it?

Mr. CRAFARD. I believe so.

Crafard tried to extract himself from that muddle by changing the time he said he was ‘passing’ Chicago to Sunday evening. But in doing so, he created another problem for himself by claiming he didn’t know it was Ruby who shot Oswald until Monday. Clearly, if Crafard had only found out Sunday evening that Oswald was shot, then that news would have also informed him that Ruby did it. After all, Ruby was very well known within the DPD.

I suggest the reason for the inconsistencies and likely deceptions — which Hubert was having problems with — is because Crafard didn’t bypass Chicago in a hitched ride. He was taken to Chicago itself, and he stayed overnight on Sunday. This was more likely a camouflaged getaway. I would also suggest that Crafard was going to meet someone there clandestinely.

Because his story did not add up, Crafard was questioned again in the morning of April 10, and put his time of his arrival in Chicago 20 hours later to late morning Monday 24th.

Mr. GRIFFIN. On that basis, what time would you say that you arrived in Chicago?

Mr. CRAFARD. It probably would put me in Chicago sometime Monday, about 10:30 or 11 o’clock in the morning.

Mr. GRIFFIN. When you arrived in Chicago, then you knew that Ruby had killed Oswald?

Mr. CRAFARD. Yes.

Mr. GRIFFIN. And what time did you arrive in Lansing, Mich.?

Mr. CRAFARD. I believe it was about 6:30 or 7 o’clock Monday evening.

Mr. GRIFFIN. When you arrived in Chicago did you make any effort to call any of the Rubensteins?

Mr. CRAFARD. No.

Mr. GRIFFIN. Did that occur to you?

Mr. CRAFARD. No; that arrival in Lansing would have been about 3:30 or 4 o’clock. It would have been a couple hours earlier.

Despite the ‘correction’ of 20 hours, his times are still all over the place, and he created no reason to know Oswald was shot without knowing Ruby did it. Griffin was rightly suspicious that Crafard was meeting people in Chicago.

The Man he recognised – with no description

In that session, when Crafard was asked more about the man, he said he recognised him from the State Fair, and who drove him out of Dallas. But he couldn’t say whether he had hair, or was bald, or wore glasses or not.

Mr. GRIFFIN. How old would you say this man was?

Mr. CRAFARD. I would say he was probably in at least his middle forties, more likely in his late forties.

Mr. GRIFFIN. Was he bald or did he have hair?

Mr. CRAFARD. I don’t really remember.

Mr. GRIFFIN. Was he a graying man or what color was his hair?

Mr. CRAFARD. I don’t remember that either.

Mr. GRIFFIN. Do you remember if he wore glasses?

Mr. CRAFARD. No.

Mr. GRIFFIN. Do you remember what kind of a car he owned?

Mr. CRAFARD. I believe he had a Chevy. I am not sure.

Mr. GRIFFIN. How would you describe his physical build, anything remarkable about it?

Mr. CRAFARD. No; not that I could think of.

Mr. GRIFFIN. Was he a thin man?

Mr. CRAFARD. He was about medium build for a man his age and height.

A question arises as to why Crafard held to the only $7 story, a point of detail that seems, again, improbable. I can only conclude that having little money was essential to the central story he’d hitchhiked, whilst also ruling out the possibility he’d used public transportation. Travel by public transport could invoke a search for witnesses, and would firm up the times.

The lone fish journey does serve a purpose: it distances him from a team effort. From all that I outlined above, it is more likely that Crafard didn’t hitchhike at all. In my view, he was driven to Chicago and then told to lie low with relatives in remote Michigan, with the hitchhiking story as a cover.

Having been asked how Crafard knew the route to Michigan from Dallas without a map, he said he’d done it previously, but then gave an irrelevant answer about a prior hitch to Sacramento and Bakersfield with his wife and two babies. That led to more questions about why Crafard’s wife wanted to take her 2 babies (one his, one by a prior marriage) hitchhiking.

It’s impossible to stitch most things Crafard said to make something sensible out of it. But this was the man who was deceptive about getting to Dallas, the dates when that was, and clung to a dubious story about what he was doing on November 22.

But the Warren Commission Final Report stated:-

“An investigation of Crafard’s unusual behavior confirms that his departure from Dallas was innocent.”

And,

“Although Crafard’s peremptory decision to leave Dallas might be unusual for most persons, such behavior does not appear to have been uncommon for him. His family residence had shifted frequently among California, Michigan, and Oregon. During his 22 years, he had earned his livelihood picking crops, working in carnivals, and taking other odd jobs throughout the country.”

That conclusion avoids the fact that Hubert and Griffin exposed Crafard’s account as being full of bizarre improbabilities that seem like cover stories. Working for the FAA in Nevada is excluded from that summary, as was his regular presence in Dallas.

Whoever drafted those assertions wasn’t reflecting the underlying evidence.