(Click here to open the document in another page.)

So much time is spent in the JFK assassination debate arguing about shaky evidence that we have seen serious researchers sometimes turn on one another and lone-nut apologists then pounce and deliver their salvos portraying the research community as made up of quacks. This is even though the official HSCA conclusions, as well as the opinions of an overwhelming number of government inquiry insiders, clearly discredit the Warren Commission conclusion that Oswald and Jack Ruby both acted alone. Therefore, this author has steered clear of discussions around subjects such as Judyth Vary Baker, Madeleine Brown, James Files, the Badge Man photo, the Prayer Man photo, etc.

My focus has always been on smoking gun evidence. There are three levels of smoking guns:

There are a number that prove the first two points:

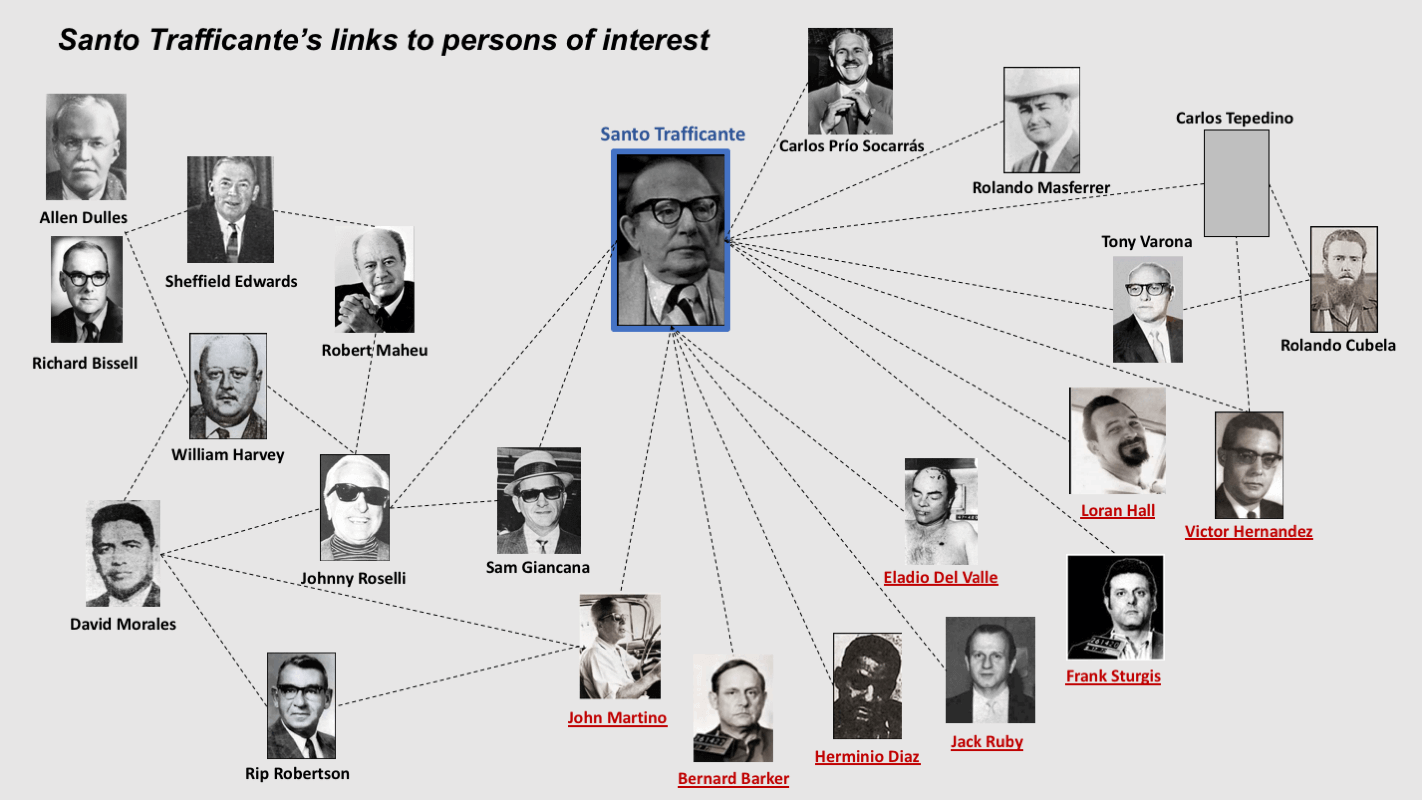

There are none at this point that prove beyond a shadow of a doubt who the conspirators were. Some do expose persons of extreme interest, these include:

In this article, we will look at another important piece of evidence and let the reader decide whether it rises to the level of a smoking gun: Oswald’s last letter!

Dueling Spins

On the very day that Kennedy was assassinated, forces that desperately wanted the overthrow of the Castro regime went into a press relations frenzy, most likely led by CIA propaganda whizz David Atlee Phillips. The tale they were peddling was that Cuba and Russia were Oswald’s backers.

Much has been written about the steps taken to sheep-dip Oswald in 1963, so that he could come out looking like an unbalanced Castro sympathizer: the famous backyard photos of him holding alleged murder weapons, as well as communist literature, his recruitment efforts for the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, his scapegoating in the General Walker murder attempt, and his interviews in New Orleans where he openly paints himself as a Castroite.

Some steps, however, went further. They were designed to make Oswald seem to be in league with Cuban and Russian agents, plotters, and assassins. They came out of the assassination play-book code-named ZR Rifle, authored by exiled, CIA super-agent William Harvey. It would have given the U.S. the excuse they needed to invade Cuba. But the new President Lyndon Johnson eventually nixed this stratagem.

Persons of interest like John Martino, Frank Sturgis, and Phillips-linked contacts (Carlos Bringuier, Ed Butler, and journalist Hal Hendrix) began a “Castro was behind it” spin to the assassination.

Carlos Bringuier of the DRE, who had gotten into what was likely a staged fight with Oswald on Canal Street in New Orleans in August of 1963, also wrote a press release that was published the day after the assassination to position Castro as being in cahoots with Oswald.

The DRE was actually set up under William Kent in 1960, working for David Phillips. David Morales was the group’s military case officer. Later, with Phillips in Mexico City, Kent was George Joannides supervisor. Kent’s daughter told Gaeton Fonzi that her father never mentioned Oswald except one time over dinner. He stated that Oswald was a “useful idiot”.

Through Ed Butler and the CIA-associated INCA, Oswald’s apparent charade and his televised interview went a long way in painting his leftist persona to the public at large. INCA had been used by Phillips for propaganda purposes during the period leading up to the Bay of Pigs. Butler was quick to send recordings to key people on the day of the assassination.

These frame-up tactics were the ones the cover-up artists wished had never occurred and worked hard to make disappear. The perpetrators of the framing of Castro offensive soon ran into stiff competition after Oswald was conveniently rubbed out. The White House and the FBI concluded, without even investigating, that both Oswald and Ruby were lone nuts. The pro-Cuba invasion forces were overmatched and their intel leaders had no choice but to fall in line.

But it was too late, there was too much spilled milk around plan A. In time, government inquiry investigators like Gaeton Fonzi, Dan Hardway, and Eddie Lopez, along with some very determined independent researchers, would uncover leads that all pointed in the same direction: Oswald was framed to appear to be in league with Cuban and Russian agents.

This can only lead to two possibilities. If Oswald was in cahoots with foreign agents, there was a foreign conspiracy to remove the president. In the more likely scenario that Oswald was being framed to look like he was cahoots with foreign agents, there was a domestic conspiracy to remove the president. In both cases, the lone-nut fairy-tale is obliterated.

Spilled Milk

Oswald and Kostikov

On September 27, 1963, Oswald allegedly travelled to Mexico City and visited both the Cuban consulate and the Russian embassy, in a failed attempt to obtain a visa to enter Cuba. FBI agents, who had listened to tapes of Oswald phone calls made while in the Cuban consulate, and Cuban consul Eusibio Azque, confirmed that there was an Oswald imposter.

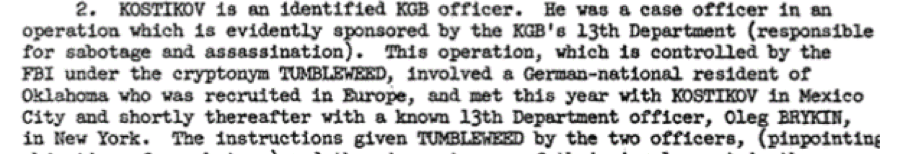

In October 1963, the CIA produced five documents on Oswald that linked him to Valery Kostikov. One of the claims was that they had met in the Russian Embassy in Mexico City. Kostikov was later described as “an identified KGB officer … in an operation which is evidently sponsored by the KGB’s 13th Department (responsible for sabotage and assassination).” They also confirmed that they felt that there were either fake phone calls made by an Oswald impostor to Kostikov while he was allegedly in Mexico or at least faked transcripts.

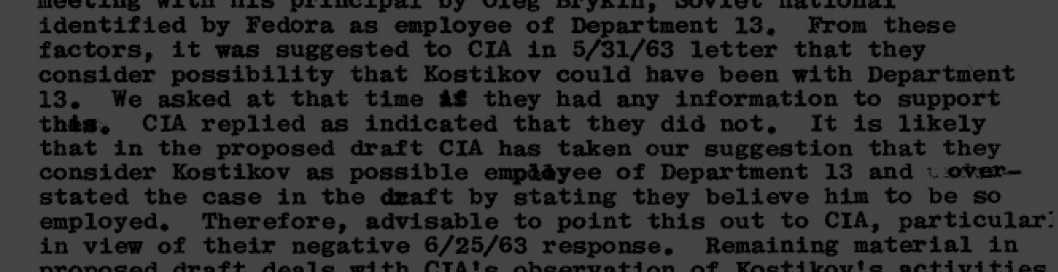

In September 1964, the case against Kostikov took a bizarre turn, when a September 1, 1964, Hoover memo (105-124016) to the CIA seemed to indicate that the CIA (James Angleton’s department) in fact had no evidence to prove Kostikov was part of the infamous Department 13.

This means either one of two things:

David Atlee Phillips’ dirty tricks

HSCA investigator Dan Hardway hypothesizes that, because of compartmentalization, Phillips and Oswald may have found out on November 22, 1963, that Oswald was a patsy and Phillips received orders to tie the murder to Castro.

In a critique of Phil Shenon’s work written for the AARC in 2015, Hardway expresses the opinion that the CIA is heading to what he calls a limited hang-out by admitting that Oswald may have received guidance from Cuba and that the CIA director at the time, John McCone, was involved in a benign cover-up.

Following the assassination, it became obvious that Phillips was connected to several disinformation stories trying to link Oswald to Castro agents. HSCA investigator Hardway called him out on it:

Before our unexpurgated access was cut off by Joannides, I had been able to document links between David Phillips and most of the sources of the disinformation that came out immediately after the assassination about Oswald and his pro-Castro proclivities. I confronted Phillips with those in an interview at our offices on August 24, 1978. Phillips was extremely agitated by that line of questioning, but was forced to admit that many of the sources were not only former assets that he had managed, in the late 50’s and early 1960’s, but were also assets whom he was personally managing in the fall of 1963. Mr. Phillips was asked, but could not explain, why the information that came from anti-Castro Cuban groups and individuals pointing to Cuban connections, all seemed to come from assets that he handled personally, but acknowledged that that was the case.

One of these assets was Nicaraguan double agent Gilberto Alvarado who, on November 25, claimed to have witnessed Oswald being paid off to assassinate Kennedy when Oswald was in Mexico City. A tale that was quickly debunked.

While the HSCA hearings were going on, Phillips himself made the claim to a Washington Post reporter that he had heard a taped intercept of Oswald when he was in Mexico City talking to a Russian Embassy official offering to exchange money for information (Washington Post, November 26, 1976). Something he never repeated. Phillips also tried to get Alpha 66 operative Antonio Veciana to get one of his relatives in Mexico City to attest that Oswald accepted bribes from a Cuban agent.

Letters from Cuba to Oswald—proof of pre-knowledge of the assassination

For this obvious frame-up tactic, it is worth revisiting what was written in this author’s article The CIA and Mafia’s “Cuban American Mechanism”.

In JFK: the Cuba Files, a thorough analysis of five bizarre letters, that were written before the assassination in order to position Oswald as a Castro asset, is presented. It is difficult to sidestep them the way the FBI did. The FBI argued that they were all typed from the same typewriter, yet supposedly sent by different people. Which indicated to them that it was a hoax, perhaps perpetrated by Cubans wanting to encourage a U.S. invasion. However, the content of the letters and timeline prove something far more sinister according to Cuban intelligence. The following is how John Simkin summarizes the evidence:

The G-2 had a letter, signed by Jorge, that had been sent from Havana to Lee Harvey Oswald on November 14th, 1963. It had been found when a fire broke out on November 23rd in a sorting office. “After the fire, an employee who was checking the mail in order to offer, where possible, apologies to the addressees of destroyed mail, and to forward the rest, found an envelope addressed to Lee Harvey Oswald.” It is franked on the day Oswald was arrested and the writer refers to Oswald’s travels to Mexico, Houston and Florida …, which would have been impossible to know about at that time!

It incriminates Oswald in the following passage: “I am informing you that the matter you talked to me about the last time that I was in Mexico would be a perfect plan and would weaken the politics of that braggart Kennedy, although much discretion is needed because you know that there are counter-revolutionaries over there who are working for the CIA.”

Escalante informed the HSCA about this letter. When he did this, he discovered that they had four similar letters that had been sent to Oswald. Four of the letters were post-marked “Havana”. It could not be determined where the fifth letter was posted. Four of the letters were signed: Jorge, Pedro Charles, Miguel Galvan Lopez, and Mario del Rosario Molina. Two of the letters (Charles & Jorge) are dated before the assassination (10th and 14th November). A third, by Lopez, is dated November 27th, 1963. The other two are undated.

Cuba is linked to the assassination in all of the letters. In two of them, an alleged Cuban agent is clearly implicated in having planned the crime. However, the content of the letters, written before the assassination, suggested that the authors were either “a person linked to Oswald or involved in the conspiracy to execute the crime.”

This included knowledge about Oswald’s links to Dallas, Houston, Miami, and Mexico City. The text of the Jorge letter “shows a weak grasp of the Spanish language on the part of its author.” It would thus seem to have been written in English and then translated.

Escalante adds: “It is proven that Oswald was not maintaining correspondence, or any other kind of relations, with anyone in Cuba. Furthermore, those letters arrived at their destination at a precise moment and with a conveniently incriminating message, including that sent to his postal address in Dallas, Texas … The existence of the letters in 1963 was not publicized or duly investigated and the FBI argued before the Warren Commission to reject them.”

Escalante argues: “The letters were fabricated before the assassination occurred and by somebody who was aware of the development of the plot, who could ensure that they arrived at the opportune moment and who had a clandestine base in Cuba from which to undertake the action. Considering the history of the last 40 years, we suppose that only the CIA had such capabilities in Cuba.”

We will see that these letters are suspiciously similar to Oswald’s “last letter.”

Policarpo Lopez

Attempts to link foreign governments to the assassination were not just limited to the framing of Oswald. As reported in the article The Three Failed Plots to Kill JFK, eight alternate patsies were profiled and no fewer than five of these made strange trips to Mexico City and at least four had visited Cuba.

One who did escape authorities to Mexico and was reportedly the lone passenger on a plane to Cuba shortly after the assassination was Policarpo Lopez. Even the HSCA found this case egregious.

The HSCA described parts of what it called the “Lopez allegation”:

Lopez would have obtained a tourist card in Tampa on November 20, 1963, entered Mexico at Nuevo Laredo on November 23, and flew from Mexico City to Havana on November 27. Further, Lopez was alleged to have attended a meeting of the Tampa Chapter of the FPCC on November 17 … CIA files on Lopez reflect that in early December, 1963, they received a classified message requesting urgent traces on Lopez … Later the CIA headquarters received another classified message stating that a source stated that “Lopes” had been involved in the Kennedy assassination … had entered Mexico by foot from Laredo on November 13 … proceeded by bus to Mexico City where he entered the Cuban Embassy … and left for Cuba as the only passenger on flight 465 for Cuba. A CIA file on Lopez was classified as a counterintelligence case.

An FBI investigation on Lopez through an interview with his cousin and wife, as well as document research, revealed that … He was pro-Castro and he had once gotten involved in a fistfight over his Castro sympathies.

The FBI had previously documented that Lopez had actually been in contact with the FPCC and had attended a meeting in Tampa on November 20, 1963. In a March 1964 report, it recounted that at a November 17 meeting … Lopez said he had not been granted permission to return to Cuba, but was awaiting a phone call about his return to his homeland … A Tampa FPCC member was quoted as saying she called a friend in Cuba on December 8, 1963, and was told that he arrived safely. She also said that they (the FPCC) had given Lopez $190 for his return. The FBI confirmed the Mexico trip (Lopez’ wife confirmed that in a letter he sent her from Cuba in November 1963, he had received financial assistance for his trip to Cuba from an organization in Tampa) … information sent to the Warren Commission by the FBI on the Tampa chapter of the FPCC did not contain information on Lopez’ activities … nor apparently on Lopez himself. The Committee concurred with the Senate Select Committee that this omission was egregious, since the circumstances surrounding Lopez’ travel seemed “suspicious”. Moreover, in March 1964, when the WC’s investigation was in its most active stage, there were reports circulating that Lopez had been involved in the assassination … Lopez’ association with the FPCC, however, coupled with the fact that the dates of his travel to Mexico via Texas coincide with the assassination, plus the reports that Lopez’ activities were “suspicious” all amount to troublesome circumstances that the committee was unable to resolve with confidence.

Oswald’s Last Letter

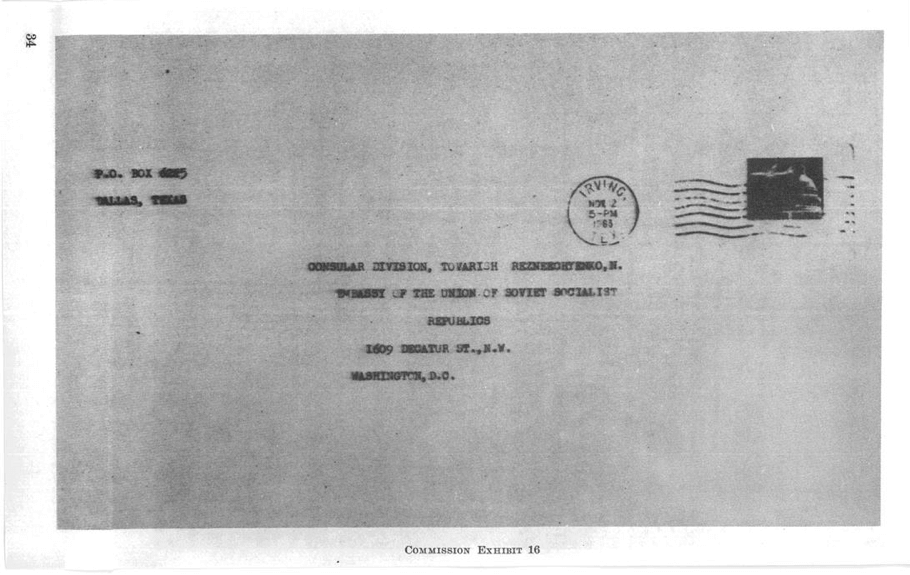

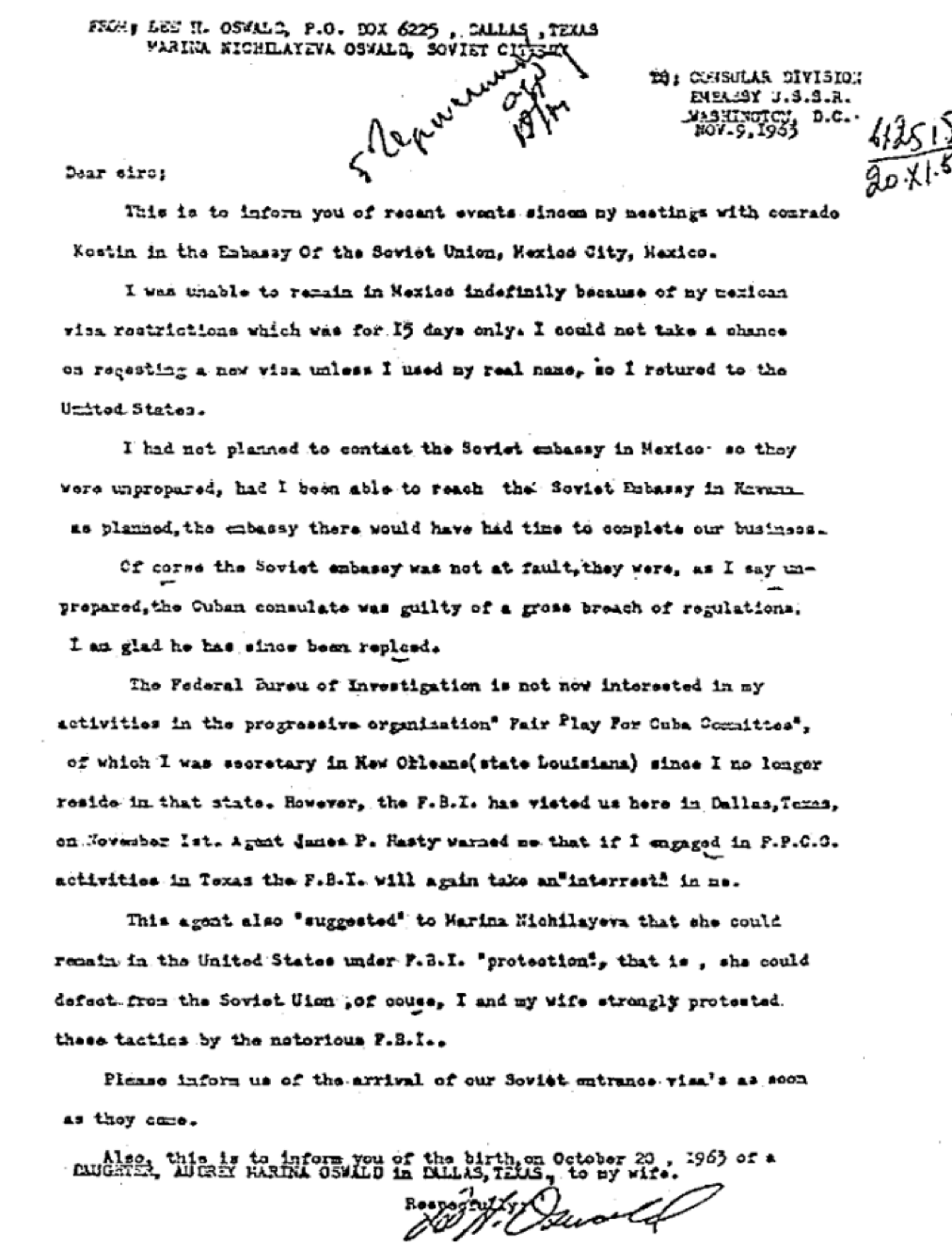

On November 18, 4 days before JFK’s assassination, the Russian Embassy received a letter dated November 9 from “Oswald”, which was uncharacteristically typed and was in an envelope post-marked November 12. The letter, as was the case for all mail sent to the Russian embassy, had been intercepted by the FBI (Hoover phone call to Johnson November 23 10:01). The envelope is addressed to Tovarish Reznekohyenko, N. (note that Tovarish means Comrade).

Before this incriminating letter, there were at least 6 exchanges in writing between the Oswalds and the Russian Embassy between February and November 1963, where the Russian contact was Nikolai Reznichenko according a number of Warren Commission exhibits. We can assume he is also the recipient of the last letter, despite different spellings.

The FBI sent a briefing about the letter to the FBI Dallas office who received it on the day of the assassination. The Russians, sensing they could be blamed, handed over a copy of the letter to the Americans after noting correctly that it was the only one of all the letters from Oswald that was typed and that its tone differed from all previous correspondence. As the Soviet Ambassador pointed out at the time, the tone was also quite dissimilar to anything Oswald had communicated before; it gave “the impression we had close ties with Oswald and were using him for some purposes of our own.” Their opinion was that it was either a fake or dictated to him. Previous letters were more straight to the point dealing with visa applications.

This letter became a hot potato. One that posed problems for the Warren Commission and the HSCA, which were amplified by the different takes Ruth and Michael Paine, Marina Oswald, the CIA, and the Russians had on it and the incredible lack of depth in the Warren Commission probe.

With time, researchers like Peter Dale Scott, James Douglass, and Jerry D. Rose pointed out several troubling points, not only in the letter itself, but also with a Ruth Paine generated handwritten draft of the letter, as well as a Russian analysis of it.

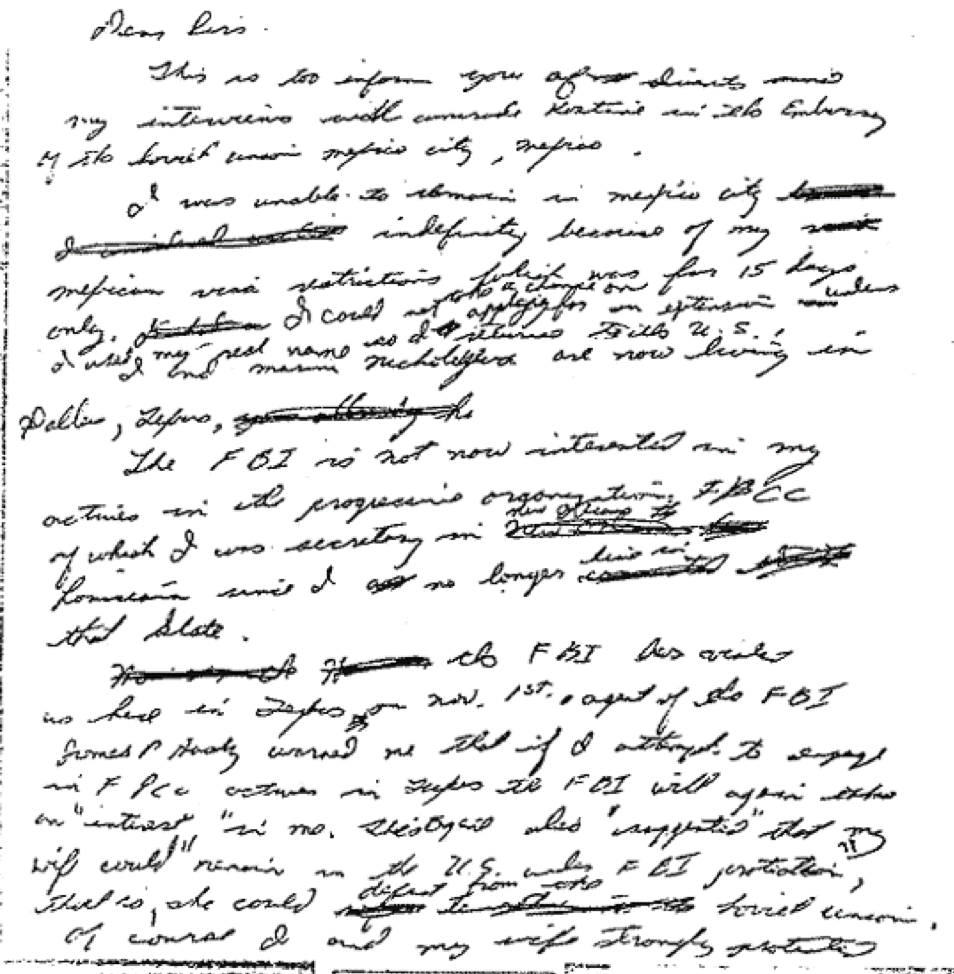

Warren Commission Volume 16 Exhibit 16

Letter from Lee Harvey Oswald to the Russian Embassy, dated November 9, 1963:

Warren Commission Volume 16 Exhibit 15

The mistake-riddled letter was linked to Ruth Paine’s typewriter. Ruth Paine and Marina Oswald testified that they had seen Oswald working on the letter shortly before it was sent and Ruth and Michael Paine both testified that they had seen a handwritten draft of the letter, which Ruth Paine handed over to an FBI official on November 23. Somehow, investigators who had combed through the Paine house had missed it. Handwriting analysis apparently confirmed it had been written by Oswald.

For some incredible reason, by April 1964, the Warren Commission had accepted a Ruth Paine request to have Oswald’s draft returned. However, when the Dallas FBI did return it to her, she decided to send it back to the Commission, because, finally, she felt it would be more proper for it to be kept in the public archives, but would take it in the event it would not be archived. Hoover said with finality that the Commission would not hold onto it and, by May 1964, had the original sent back to Ruth Paine, which escaped further examination as to its authenticity. (JFK and the Unspeakable, p.443)

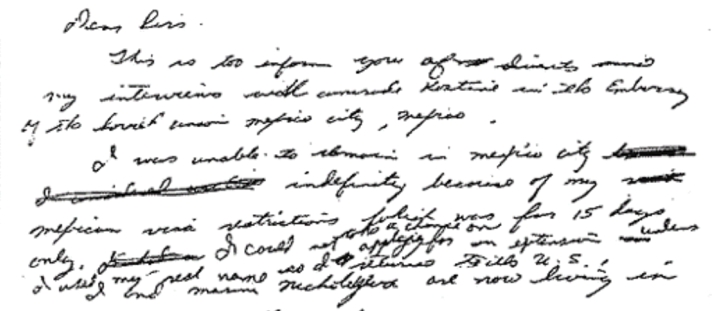

Oswald’s draft of the letter found by Ruth Paine:

HSCA exhibit F 500/Warren Commission exhibit 103

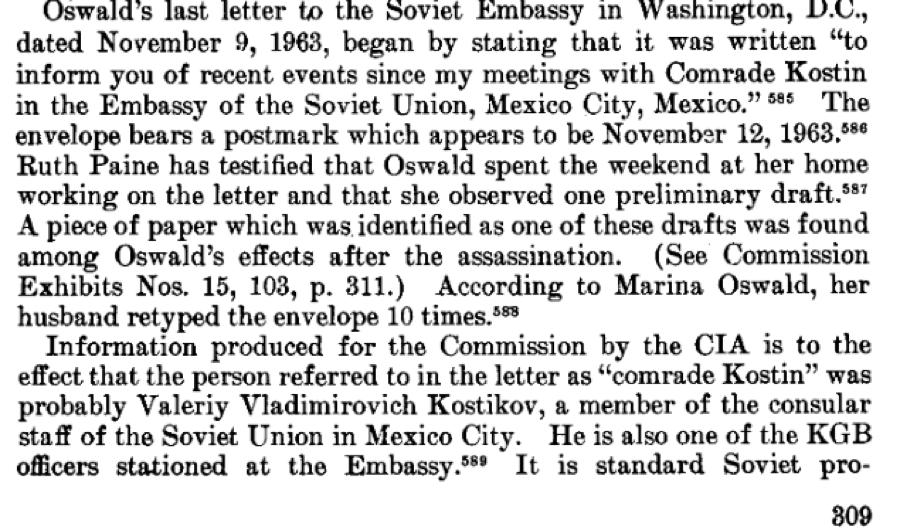

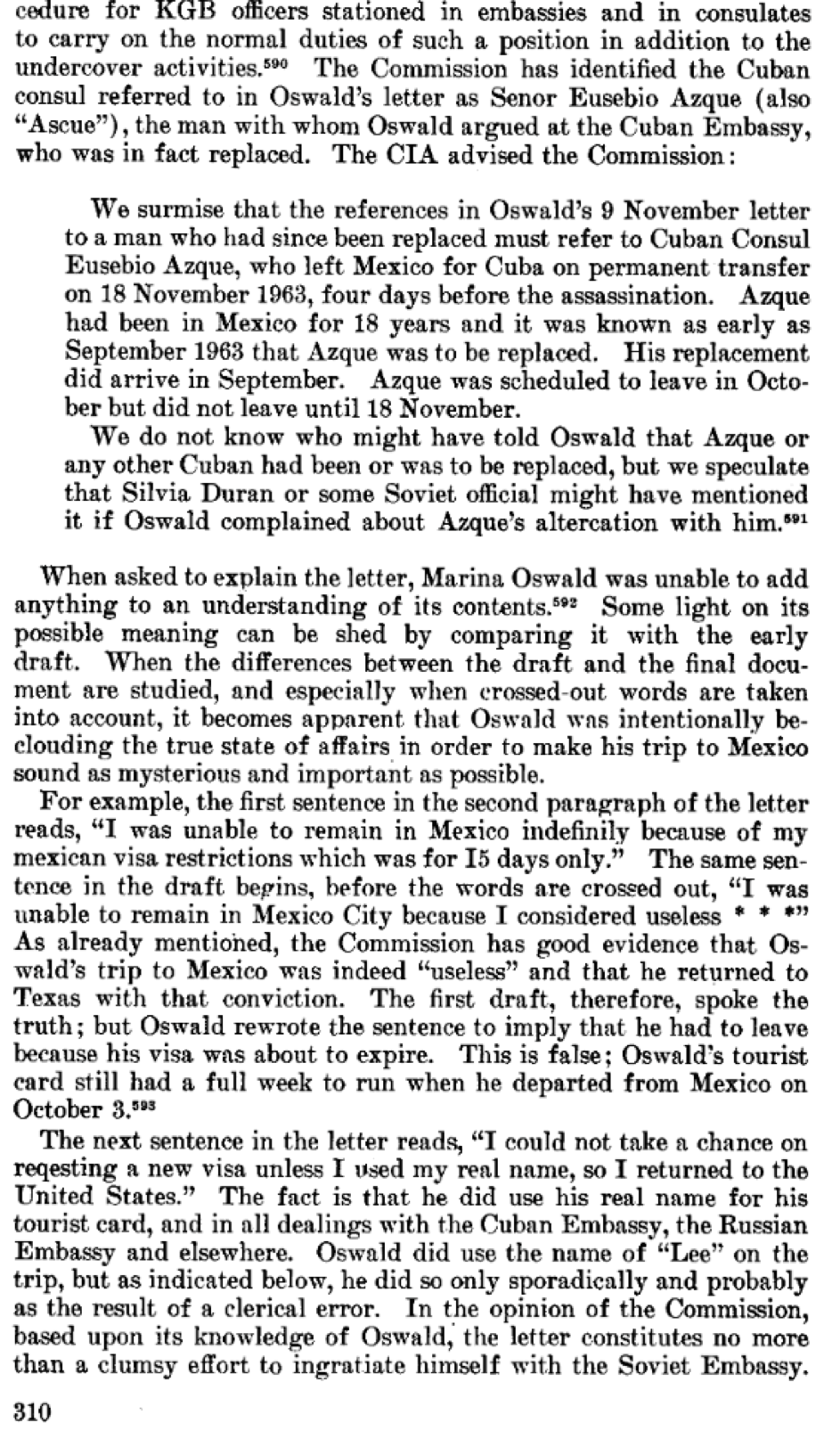

The Warren Report’s descriptions of Oswald’s trip to Mexico City and his last letter are among the best examples of just how weak their investigation was and how misleading they were in their disclosures.

It seems the only thing that they found perplexing from the letter was how a “drifter” like Oswald could have known that a consul from the Cuban consulate in Mexico City could have been replaced. So, they asked the CIA to weigh in. The CIA surmised that the consul in question was Eusebio Azque and speculated that Silvia Duran or some Soviet official might have mentioned it if Oswald had complained about an altercation with Azque.

The Commission recognized that Kostin, who Oswald talks about, was KGB officer Valery Kostikov, but dilutes the meaning of this by stating “that it was common procedure for such KGB officers stationed in embassies to carry on normal duties along with undercover activities”.

Buried in the appendices of the Report, we can find a memo (Warren Commission Document 347 of January 31, 1964, p. 10) by the FBI’s Ray Rocca, sent to the Commission in January 1964:

Kostikov is believed to work for Department Thirteen of the First Chief Directorate of the KGB. It is the department responsible for executive action, including sabotage and assassination. These functions of the KGB are known within the Service itself as “Wet Affairs” (mokryye dela). The Thirteenth Department headquarters, according to very reliable information, conducts interviews or, as appropriate, file reviews on every foreign military defector to the USSR to study and to determine the possibility of using the defector in his country of origin.

Richard Helms, while heading the CIA, went on to confirm this very important detail. Kept hidden from the public was an allegation that Oswald had met Kostikov just a few weeks earlier in Mexico City and that a likely Oswald impostor had placed a call to Kostikov that was intercepted by the CIA! This makes the reference to “unfinished business” that we can read in the letter quite suggestive.

It is interesting to note that the letters from Cuba designed to incriminate Oswald and link him to Cuban agents use some of the same suggestive language. “Close the business”, “after the business, I will recommend you”, and “after the business I will send you your money” are some of the phrases that can be found in just one of the letters. Others talk about “the matter” or “the plan”.

A real investigation and transparent report would have revealed a lot more about Kostikov’s explosive background and would have blown the lid off what really happened in Mexico City. It would have also delved into who the recipient of the Washington letter was and its important significance, if Plan A (blaming foreign foes for the assassination) had been pursued. Something we will discuss later.

Instead, the report concludes its extremely hollow analysis on a whimper: “In the opinion of the Commission, based upon its knowledge of Oswald, the letter constitutes no more than a clumsy effort to ingratiate himself with the Soviet Embassy.” The truth was that, had plan A gone ahead, the letter would have been peddled as further proof of complicity between the president’s “murderer” and foreign adversaries.

The Warren Report on the letter

While Jim Garrison clearly suspected something unholy occurred in Mexico City, as well as with the letter, the public had to wait until 1970 to see some of the first clues about what the FBI really thought about this correspondence, when newsman Paul Scott revealed the following:

The F.B.I. discounts the C.I.A. suggestion to the Warren Commission that Silvia Duran, a pro-Castro Mexican employee of the Cuban Embassy, might have told Oswald about Azque being removed. In her statement to Mexican officials concerning her discussion with Oswald, Mrs. Duran made no mention of Azque. And, although she was questioned at the request of C.I.A., no attempt was made to quiz her about whether she knew of Azque’s recall. This makes the C.I.A. conclusion highly dubious, to say the least.

Although the F.B.I. still has not been able to resolve the key mystery of the Oswald letter, it has narrowed the sources of where he might have obtained information about Azque. These sources are: (1) An informant in the Cuban Embassy in Mexico City who contacted Oswald after he returned to the U.S. (2) The Central Intelligence Agency. Or (3), the Soviet Secret Police (K.G.B.) in Mexico City. Significantly, the F.B.I. probe discovered that the K.G.B. and the C.I.A. learned of Azque’s replacement at approximately the same time and not until after Oswald visited Mexico City. This finding has raised the possibility that whoever informed Oswald contacted him after he returned to Dallas from Mexico City.

According to Paul Scott’s son Jim, his father was wiretapped for over 50 years, because of his dogged investigations into the assassination.

The HSCA

Perhaps the biggest blow to the Lone Nut fabrication came when the Church Committee and the HSCA investigations deciphered one of the most important ruses, which would turn the tables on the frame-up artists who concocted the aborted Plan A stratagem. This had to be kept secret.

One thing the Lopez Report makes very clear is that an Oswald impostor made a phone call designed to lay down a trace that would be used as proof of Russian complicity in the assassination and would provide the types of motives and stratagems that were part of the ZR/RIFLE and the Joint Chiefs of Staffs Operation Northwoods play books, both which involved having adversaries blamed for their own covert acts of aggression. The letter served to authenticate the Oswald-Kostikov relationship and add a third player to the mix. The potato became scorching hot.

This analysis needed to be buried as much and as long as possible. The HSCA did not want to be the ones exposing this in the 1970s. The world had to wait nearly 25 years for the declassification of the explosive reports concerning Oswald’s trip to Mexico City and the mysterious letter and sometimes much later for their eventual release.

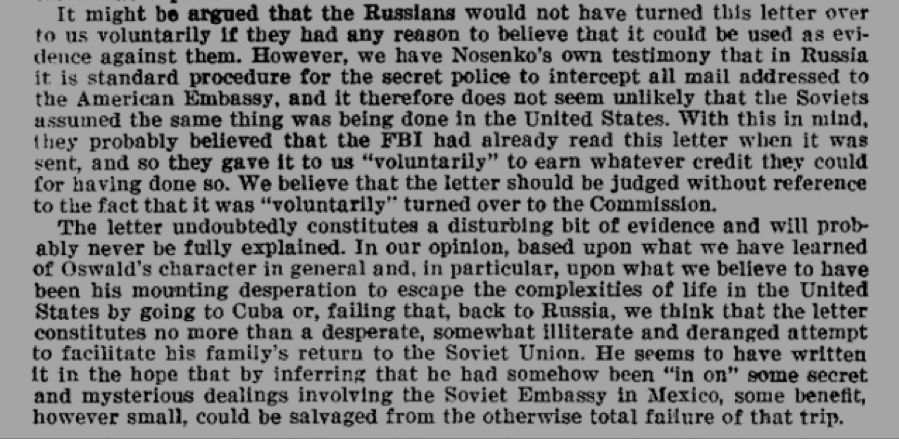

The HSCA’s conclusions about the letter were even more hypocritical than the Warren Commission’s. While they recognize that it is “disturbing”, they seem to ignore the fact that the letter had been intercepted by the FBI and do not factor in the explosive findings of their very own Lopez Report, nor the confirmations about Kostikov’s role as Russia’s head of assassinations for the Western Hemisphere. When we consider the proof that they were sitting on, that an Oswald impersonator was recorded talking to Kostikov, and that Oswald (or an impostor) was said to have actually met him, we can easily see that the context of the letter and its explosive meaning were completely sidestepped in the Report:

While the second paragraph represents a fake opinion designed to deviate from the real implication of the letter, the first one represents a blatant deception that can be proven outright by the transcript of Hoover’s call to President Johnson the day after the assassination:

In short, the FBI did in fact examine all mail sent to the Soviet Embassy and had a copy of the letter all along.

The ARRB and Russians Weigh In

Thanks in large part to Oliver Stone and his landmark JFK movie classic, the ARRB was founded in 1992 and began declassifying files shortly after on the JFK assassination. In 1996, the Lopez Report was available. By 2003, a less redacted version was released. The explosive document shed light on Oswald impersonators, missing tapes, photos, and bold-faced lying by top CIA officials. The lone drifter was not alone!

As reported by Jerry Rose in the Fourth Decade, in 1999, Boris Yeltsin handed Bill Clinton some 80 files pertaining to Oswald and the JFK assassination. One of the memos reveals that, at the time of the assassination, Russian ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin had right away seen the letter as a “provocation” to frame Russia by the fabrication of complicity between Russia and Oswald, when none existed. “One gets the definite impression that the letter was concocted by those who, judging from everything, are involved in the president’s assassination,” Dobrynin wrote. “It is possible that Oswald himself wrote the letter as it was dictated to him, in return for some promises, and then, as we know, he was simply bumped off after his usefulness had ended.” In late November, the Russians sent the letter to U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk explaining why the letter was a fraud. By then, the White House was peddling the lone nut fable. Kept hidden was the fact that the FBI already had a copy of the letter.

In his article, Rose points out that the typed letter had many more spelling errors in it than the rough draft. Very odd indeed.

If you go back to how the Warren Commission fluffs off the alleged Kostikov/Oswald (and/or impostor) exchanges and compare it with what is written by Bagley in the CIA’s November 23rd 1963 memo (declassified in 1998), you will see a startling difference in Kostikov’s status:

Memo of 23 November 1963 from Acting Chief, SR Division, signed by Tennant Bagley, “Chief, SR/Cl.” CIA Document #34-538

Just one of the reasons the Warren Report was impeached! But wait, it gets worse.

The FBI’s Reaction to the Letter and the Mysterious Tovarish Reznkecnyen

Since the mid-1990s, there have been a few revealing writings about the letter, but very little about the FBI’s take on it.

Now, thanks to document declassification, we can see it through a wider scope that includes troubling dovetailing facts, such as the impersonation of Oswald in Mexico City and multiple hoaxes to tie him in unequivocally with sinister foreign agents and the chief assassination officer in Mexico—Kostikov. The analysis of tape recordings and transcripts, the mysteriously disappearing evidence, the fake letters from Cuba, and the full-fledged perjury of CIA officer David Atlee Phillips during the HSCA hearings prove there was subterfuge beyond a shadow of a doubt.

Hoover’s phone call to Johnson is already very revealing. The following FBI report (HSCA Record 180-10110-10104), released only in 2017, is nothing short of stunning. It was the one Scott wrote about in 1970. It is strongly urged that you follow the above link to understand the full implication of the report, which sheds light on the investigation mindset which preceded the whitewash. However, for this article, our attention will be on the following paragraph of the report which focuses on the letter Oswald sent to the Soviet Embassy in Washington.

Oswald’s letter deeply troubled the FBI for a number of reasons. Its tone was one of ongoing complicity referring to “unfinished business” and convenient reminders of the alarming exchange between Oswald and Kostikov. But the letter stretches the elastic to add yet another element that has so far gone under the radar.

The fact that the letter was sent to Tovarich Nikolai Reznichenko all of a sudden became alarming, even though the Oswalds corresponded with him several times in 1963. The FBI report clearly refers to him as “the man in the Soviet Embassy (Washington’s) in charge of assassinations.” In 1970, Scott had described him as “one of the top members of the Soviet Secret Police (K.G.B.) in the United States.”

The significance of this report leads to many conclusions and as many unanswered questions. Hoover had already decided that Oswald acted alone and they would not “muddy the waters internationally”. The HSCA, who possessed this document, in reports debates the authenticity of the same letter that was given to Dean Rusk by the Soviet ambassador, when they knew full well of its existence and FBI worries about its explosive implications. While this author has found little corroboration about Nikolai Reznichenko’s status, or perceived status, he believes it should not be dismissed as a mistake or confusion with Kostikov. This is an official FBI report that was written in 1963. There have not been any clarifications made about this very significant statement, despite the fact that Paul Scott exposed this in 1970 and its access to HSCA investigators.

The mere fact that he worked in the Russian embassy and that he often corresponded with a “defector” on a watch list and his Russian wife and that the last letter by Oswald addressed to him has a complicit tone while name dropping the Mexico-based KBG chief of assassinations and talking about unfinished business suggests that both the FBI and the CIA had files on him. Where are they? For him to be described by Hoover as the head of assassinations in Washington on the part of the Soviet government in an official FBI document is of utmost significance and requires an explanation.

This is one issue that deserves more debate in the research community.

Conclusion

The last letter on its own, perhaps, does not rise to the level of a smoking gun that proves there was conspiracy. It is another compelling piece of evidence that does prove that the Warren Commission and the HSCA shelved important evidence and information from the public that they found bothersome.

If one adds this letter to the other attempts to pin the blame on foreign agents, including the charade in Mexico City, false testimonies by CIA contacts, the perjury of CIA officials of interest in the case, the Policarpo Lopez incident, and the incriminating letters from Cuba, we have proof beyond a shadow of a doubt that there was conspiracy. The naysayers cannot have it both ways. Either these events were genuine, which proves an international conspiracy, or they were not, which proves a domestic conspiracy. There has been enough evidence to demonstrate that they were not genuine.

The letter has one attribute that can play an important role, actually proving who some of the conspirators were. It pre-dates the assassination. As it refers to happenings and ruses that took place in Mexico City two months earlier that few knew about, we can narrow the scope on who was involved. When we inspect the propaganda aspect of the operation, the case against David Atlee Phillips as a person of extreme interest is almost airtight. He had many touch points with Oswald and is easy to link to all of the ruses behind the sheep dipping activities, including the incriminating last letter.

The murder of Officer J.D. Tippit in Oak Cliff was famously cited by David Bellin, Assistant Counsel to the Warren Commission, as being the “Rosetta Stone to the solution” of the JFK assassination. (Jim Marrs, Crossfire, p. 340, all references are to the 1989 edition) “Once it is admitted that Oswald killed Patrolman J.D. Tippit,” the attorney for the commission observed, “there can be no doubt that the overall evidence shows that Lee Harvey Oswald was the assassin of John F. Kennedy.”

Following Mr. Belin’s questionable logic might also lead one to believe the opposite to be true. Once it is shown that Oswald likely did not kill Patrolman Tippit, the case for him having shot President Kennedy and Governor Connally is, therefore, demonstrably weakened.

“I emphatically deny these charges!” shouted Oswald to news reporters while in Dallas police custody. “I didn’t shoot anybody, no sir … I’m just a patsy!” Oswald denied his guilt in many ways and more than once. (Mark Lane, Rush to Judgment, p. 81)

Was the suspect telling the truth?

Sadly, within less than 48 hours, shadowy nightclub owner Jack Ruby would all but terminate the official Dallas Police investigation into the Tippit homicide when he gunned down suspect Lee Oswald in the basement of Dallas Police Headquarters. That unfathomable event, broadcast live on national television, occurred in the presence of more than 50 Dallas policemen. It was their job to ensure Oswald’s safety while he was in custody—so the suspect might be tried on charges of assassinating President Kennedy and murdering Officer Tippit.

“We never worked on any of his (Tippit’s) murder, because there was no use making a murder case (with the suspect dead),” admitted former District Attorney Henry Wade in an interview with veteran Tippit researcher Joseph McBride. “I think we had enough evidence that Oswald did it.”

And despite Belin’s “Rosetta Stone” reference, not only did Dallas authorities abandon the Tippit case, but the Warren Commission, according to McBride, showed “almost no real interest in solving the crime … the commission was deliberately stonewalling a serious investigation of Tippit.”

Any “serious” investigation into Tippit’s death must begin with one fundamental and all-important question: Why did Tippit stop Oswald?

Based on the persistence of several indefatigable private researchers and investigators who kept digging into the Tippit mystery for decades, I believe we can now attempt to answer that question. The answer, it would seem, had nothing to do with the man walking on 10th Street in Oak Cliff matching the Dealey Plaza suspect’s generic description of being a young white male of average height and weight—as was suggested by the Warren Commission.

In the words of Sylvia Meagher, writing in her 1967 book Accessories After the Fact, “The strangeness of Tippit’s actions,” suggests that “it was not probable, perhaps not even conceivable, that Tippit stopped the pedestrian who shot him because of the description broadcast on the police radio. The facts indicate that Tippit was up to something different which, if uncovered, might place his death and the other events of those three days in a completely new perspective.” (See Meagher, pp. 260-66)

What follows in this article is a “new perspective.”

12:00 P.M.

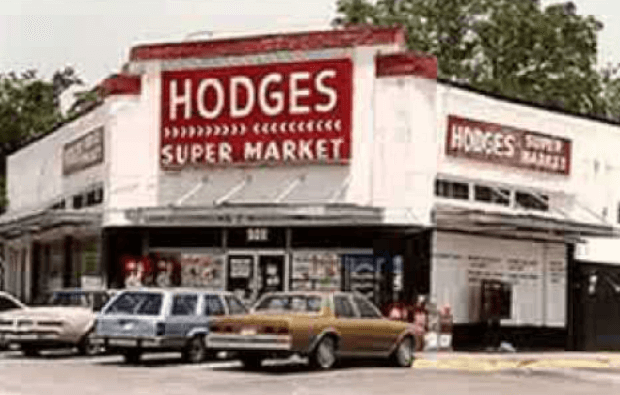

The “strangeness” of Tippit’s actions on 11/22/63 appear to have begun even before shots rang out in downtown Dallas. Tippit, whose normal area of patrol was in Cedar Crest, patrol area #78, was apparently called to a supermarket in the 4100 block of Bonnie View Road. Respected Tippit researcher Larry Ray Harris interviewed the Hodges Supermarket manager in 1978. As described in news reporter Bill Drenas’ oft-cited 1998 article Car #10 Where are You?, the manager told Harris he had caught a woman shoplifter on 11/22/63 and had phoned police.

It was Tippit who responded to that location at about noon, just a half hour before the assassination. The manager knew Tippit, because Tippit routinely came to the market on calls for shoplifters. The interviewee said Tippit placed the woman in his squad car and left. However, Tippit appears not to have brought the shoplifting suspect back to his nearby base of operations. No record of the woman’s arrest or information on who she was or what happened to her has ever surfaced.

12:30 p.m.

President Kennedy’s motorcade was scheduled to have arrived at the Dallas Trade Mart at 12:30. However, because the motorcade was running a few minutes late, President Kennedy was assassinated at 12:30, and Governor Connally was gravely injured, as the motorcade proceeded through Dealey Plaza on route to the Trade Mart. The Hodges Market in the 4100 block of Bonnie View in Tippit’s district was more than seven miles southwest of Dealey Plaza.

12:40 p.m.

The DPD Channel 1 dispatcher reports a shooting in the downtown area involving the President. By this time, Texas School Book Depository employee Lee Oswald has already grabbed his blue work jacket and has left the TSBD on foot. He will board a city bus, but when that bus gets stalled in traffic, Oswald will ask for a transfer, depart from the bus, and walk to a cab stand to catch a quicker ride (with cab driver William Whaley) out to nearby Oak Cliff where the young man resides.

The DPD Channel 1 dispatcher next orders “all downtown area squads” to Dealey Plaza, code 3 (lights and sirens). By 12:44, a general description of the Kennedy suspect (slender white male, 5’10” and 160 pounds) is broadcast over both Channels 1 and 2.

12:45 p.m.

Murray Jackson, the dispatcher, asks Tippit to report his location. Tippit replies, according to police radio logs, that “I am about Keist and Bonnie View,” which is still within Tippit’s regular patrol district down in Cedar Crest. (Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, p.441) However, this may not have been the case.

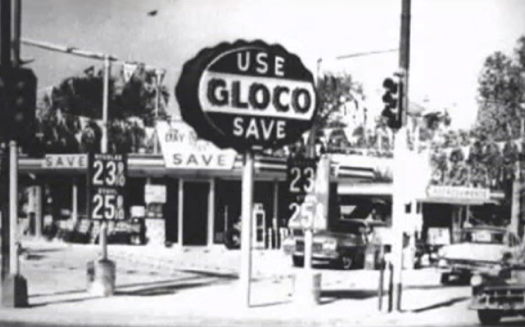

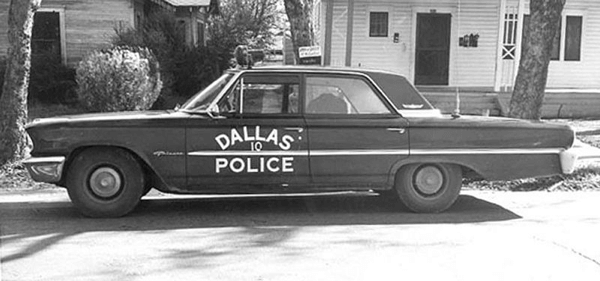

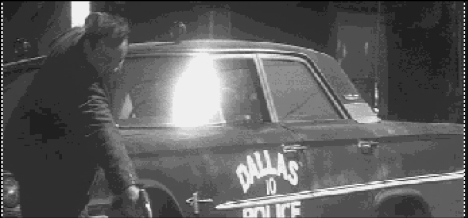

Beginning at approximately 12:45, when Officer Tippit reports he is still in his regular patrol area, Tippit will instead be seen sitting inside his squad car parked at the GLOCO gas station, strategically situated in northernmost Oak Cliff next to the Houston Street viaduct. The viaduct connects downtown Dallas and Dealey Plaza to Oswald’s neighborhood in Oak Cliff—some five miles north of Tippit’s reported position.

Researcher William Turner, in a 1966 article in the magazine Ramparts, claimed he located five witnesses who saw Tippit sitting in his patrol car at the gas station at this time while watching traffic coming across from downtown Dallas. (McBride, ibid) The location is only 1.5 miles from Dealey Plaza. Two of the witnesses, a husband and wife who knew the officer, say they waved at Tippit who waved back at them. The story was reportedly verified by three of the GLOCO station attendants. Dallas researchers Greg Lowrey and Bill Pulte also interviewed all five of these witnesses to confirm the story. Some said that Tippit arrived at the GLOCO as early as just “a few minutes” after the assassination.

Was Tippit watching for Oswald to come across the viaduct on a Dallas bus? Did he see Oswald instead in the front of William Whaley’s cab? What was Tippit doing?

12:46 p.m.

At this time, dispatcher Murray Jackson ordered Officers Tippit and R.C. Nelson into the Central Oak Cliff area, which was odd since an assigned officer (William Mentzel) was already patrolling Central Oak Cliff. (McBride, pp. 427-30) Tippit, according to witnesses, is of course already there in the northernmost part of Oak Cliff at the gas station. (This was probably unknown to Jackson, since Tippit had just responded to the dispatcher that he was in his assigned patrol area at Bonnie View & Keist some five miles to the south). Officer Nelson instead proceeded on to Dealey Plaza, possibly following the preceding 12:42 “code 3” order for all downtown area squads to report to Dealey Plaza. (Henry Hurt, Reasonable Doubt, pp. 161-63)

Meanwhile, Oswald will soon be crossing the Houston St. viaduct in William Whaley’s cab, heading for Oak Cliff.

The witnesses say that after some 10 minutes of sitting at the gas station, watching traffic crossing from the downtown area, Tippit suddenly pulled out and took off south on Lancaster Avenue “at a high rate of speed.”

12:52 or 12:53 p.m.

Cab driver William Whaley lets Oswald out at the corner of North Beckley and Neely Street, several blocks south of Oswald’s rooming house, which the cab has already passed. Whaley had marked Oswald’s intended location on his run sheet as the 500 block of N. Beckley, even farther south and in the wrong direction from the rooming house. The 500 block of N. Beckley was, in 1963, dominated by the side parking lot of the El Chico Restaurant.

12:54 p.m.

Dispatcher Murray Jackson contacts Tippit, who is now about a mile from the GLOCO Station on Lancaster Street. (McBride, p. 445) Oswald and Tippit are both apparently moving in the direction of the Texas Theater.

1:00 to 1:07 p.m.

Texas Theater manager Butch Burroughs said Oswald entered the theater during this timeframe and later bought popcorn from him at the concession stand at approximately 1:15. (McBride, p. 520) Other movie patrons will similarly report having seen Oswald in the mostly empty theater during the start of the movie, changing seats frequently and sometimes sitting directly next to other moviegoers. Is Oswald supposed to meet someone he doesn’t know personally, perhaps his intelligence contact to whom he is expected to give a briefing?

After 1:00 p.m.

Employees of the Top Ten Records store, located a block and a half west of the Texas Theater on Jefferson Boulevard, later claim that Tippit parked his squad car on Bishop Street adjacent to the records store and came in hurriedly while asking to use the phone.

Employees of the Top Ten Records store, located a block and a half west of the Texas Theater on Jefferson Boulevard, later claim that Tippit parked his squad car on Bishop Street adjacent to the records store and came in hurriedly while asking to use the phone.

A Dallas Morning News reporter interviewed former Top 10 clerk Louis Cortinas in 1981. Cortinas recalled that, “Tippit said nothing over the phone, apparently not getting an answer. He stood there long enough for it to ring seven or eight times. Tippit hung up the phone and walked off fast, he was upset or worried about something.” (McBride, p. 451)

Had Tippit picked up Oswald near the El Chico Restaurant and then dropped him off at the Texas Theater? Had Tippit simply been watching the theater to confirm Oswald’s arrival? Or, was Tippit simply trying to contact someone to find out the latest news on the condition of President Kennedy and Governor Connally?

1:03 p.m.

Around this time, police dispatcher Murray Jackson tries to radio Tippit, but gets no answer. (Meagher, p. 266) Was this when Tippit was entering the Top 10 records store to place the phone call?

Approximately 1:04 p.m.

Several blocks east of Top 10 and the Texas Theater, an unknown young white male about 5’8” to 5’10” and 165 pounds wearing a white shirt and light tan Eisenhower jacket begins to quickly walk west on East 10th Street. The man is in such a hurry that he catches the attention of those inside of Clark’s Barber Shop at 620 E. 10th as he breezes by that establishment’s storefront window. A pedestrian, Mr. William Lawrence Smith, passes the same man as Smith walks east to lunch at the Town & Country Café just a few doors west of the barber shop. (John Armstrong, Harvey and Lee, p. 841)

Approximately 1:05 p.m.

As the unknown white male proceeds west and crosses the intersection of 10th and Marsalis, a major disturbance suddenly breaks out at that corner. Bill Drenas, author of the 1998 article Car #10 Where Are You?, mentioned that a person near the scene of the Tippit shooting told investigator Bill Pulte that, “If you are planning to do more research on Tippit, you should find out about the fight that took place at 12th & Marsalis a few minutes before Tippit was killed.” The interviewee spoke only on the condition of anonymity.

Harrison Livingstone, in his 2006 book The Radical Right and the Murder of John F. Kennedy, adds more crucial detail about this mysterious neighborhood altercation. “There are neighborhood reports of a disagreement at the intersection of 12th & Marsalis,” writes Livingstone, “a few minutes before Tippit was killed. Tippit was headed precisely toward 12th & Marsalis when he left Lancaster & 8th (the report of the 12th & Marsalis argument is from someone whose identity needs to be protected).

“The late Cecil Smith witnessed this fight which was actually at 10th & Marsalis (my emphasis). One of the two individuals was stabbed, but it was never investigated, apparently … just two blocks east from where Tippit was shortly murdered.” The fight also occurred, let it be known, at the same time and location the unknown gunman in the light jacket, white shirt, and dark trousers is passing on his way two blocks west to the fast approaching scene of the fatal Tippit shooting.

But it was not until Dallas researchers Michael Brownlow and Professor William Pulte made public their findings in a 2015 Youtube video that we get the full scoop on this most unusual so-called “fight.”

Brownlow said it was actually three men and a woman who jumped on another man at the corner, who was then “violently” stabbed. The wounded man, bleeding profusely, was then inexplicably thrown into the back of a blue Mercury Monterey which sped away from the scene. Many people witnessed the assault. 10th & Marsalis was a commercial corner, with an auto parts store, a plumbing supply store, and other nearby businesses such as the barber shop and restaurant. It was Indian summer, pre-air conditioning days, and most of these businesses had telephones within easy reach. Neighbors and teens home from school also allegedly witnessed the noisy and bloody altercation. (See also, Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, pp. 447-48)

Brownlow said it was actually three men and a woman who jumped on another man at the corner, who was then “violently” stabbed. The wounded man, bleeding profusely, was then inexplicably thrown into the back of a blue Mercury Monterey which sped away from the scene. Many people witnessed the assault. 10th & Marsalis was a commercial corner, with an auto parts store, a plumbing supply store, and other nearby businesses such as the barber shop and restaurant. It was Indian summer, pre-air conditioning days, and most of these businesses had telephones within easy reach. Neighbors and teens home from school also allegedly witnessed the noisy and bloody altercation. (See also, Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, pp. 447-48)

Emergency phones calls were obviously placed to the Dallas Police, although you won’t find any mention of this incident in the DPD call logs for 11/22/63. Why not?

Approximately 1:05:30

Officer Tippit, now sitting once again in his patrol car outside of the Top 10 Records store, suddenly hears his police radio crackle to life. There has been a reported fight and possible stabbing at the corner of 10th & Marsalis, several blocks east of where his patrol car now sits near the corner of West Jefferson Blvd. and Bishop Avenue. A man has supposedly been stabbed and thrown into the back of a blue car which drove away from the scene. Tippit puts Car #10 into gear and moves out in a big hurry.

The employees at Top Ten (Lou Cortinas and Dub Stark) watch through their front window as Tippit’s car goes charging through the intersection and races north up to Sunset Street where Tippit blows through the stop sign and disappears from view. (McBride, pp. 451-550)

The employees at Top Ten (Lou Cortinas and Dub Stark) watch through their front window as Tippit’s car goes charging through the intersection and races north up to Sunset Street where Tippit blows through the stop sign and disappears from view. (McBride, pp. 451-550)

Approximately 1:06:00

Tippit quickly reaches 10th Street and is about to turn right, heading east towards the disturbance at the corner of 10th & Marsalis. But he instead observes a late model Chevrolet headed west on 10th. Could this be the car escaping from the scene of the fight? So instead of turning right, Tippit makes a quick decision and turns left, following the Chevy that has just passed in front of him. Within a block the officer speeds up, passes the Chevy, turns the wheel, and forces the surprised driver to come to a stop at the curb.

Mr. James Andrews, the motorist—who had been returning to work from his lunch hour—would later give Dallas researcher Greg Lowrey (as reported in Bill Drenas’ article Car #10 Where Are You?) the following description of this bizarre event:

Drenas writes that “The officer then jumped out of the patrol car, motioned for Andrews to remain stopped, ran back to Andrew’s car, and looked in the space between the front seat and the back seat (emphasis mine). Without saying a word, the policeman went back to the patrol car and drove off quickly. Andrews was perplexed by this strange behavior and looked at the officer’s nameplate which read ‘Tippit’ … Andrews remarked that Tippit seemed to be very upset and agitated and acting wild.” (McBride, pp. 448-49)

Much has been made of this incident, which apparently happened just a few short moments prior to Tippit’s death. Some have reasoned that Tippit was looking for Oswald, thought to be hiding in the back of an automobile on his way to Red Bird Airport to catch a flight out of town. Others have found the story so odd that they have tended to dismiss it altogether—couldn’t have happened.

But now that we have a report about a fight at 10th & Marsalis, a stabbing in which the victim was thrown into the back of a car which then sped away from the scene, Tippit’s “wild” actions perhaps make more sense. Tippit may have been looking for the injured stabbing victim in the back of an escaping vehicle—and he was doing so alone, with no backup. That is why he was agitated and acting upset. President Kennedy and Governor Connally have just been gunned down in Dealey Plaza and now Tippit is dealing with a violent, potentially life and death situation in adjoining Oak Cliff.

1:07:00 p.m.

Officer Tippit heads east on 10th Street, heading towards the scene of the reported disturbance at the corner of Marsalis. By now, according to Texas Theater Manager Butch Burroughs—as well as multiple paying customers—Lee Oswald is most definitely in the building for the start of the afternoon’s double war movie feature. (Marrs, Crossfire, pp. 352-53)

1:08:00 p.m.

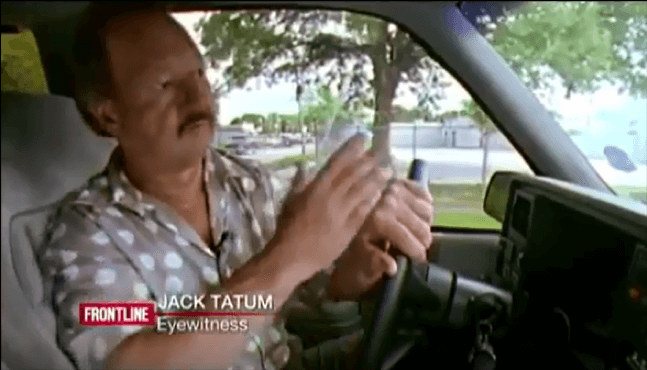

As Officer Tippit travels east on 10th towards Marsalis, he spots a lone figure walking west just two blocks from the scene of the stabbing incident. Tippit slows Car #10 as he cruises through the intersection of 10th & Patton. Cab driver Bill Scoggins, parked near the corner in his cab while eating his lunch, notices Tippit pass in front of his cab, slow down, and suddenly pull to the curb about 100 feet past Patton Street. The officer apparently summons the young pedestrian, who is wearing the beige Eisenhower jacket, dark trousers, and white shirt, back to his patrol car.

The young man does an about-face, turning around to approach Tippit’s car sitting at curbside. Could this young man have been a witness? A participant in the fight? He doesn’t appear to have any blood on his jacket that the officer can see. Tippit and the young man, who is now leaning over, have a brief conversation through the open vent on the passenger-side window.

The young man does an about-face, turning around to approach Tippit’s car sitting at curbside. Could this young man have been a witness? A participant in the fight? He doesn’t appear to have any blood on his jacket that the officer can see. Tippit and the young man, who is now leaning over, have a brief conversation through the open vent on the passenger-side window.

1:08:30 p.m.

Officer Tippit, who probably does not fully believe the young man’s story about who he is and what business he has on 10th Street, decides to get out of his car to question the subject further. He adjusts his police cap, begins to walk slowly towards the front of Car #10. As he does, the man pulls a .38 revolver from under his jacket and begins to fire.

No one sees the actual shots. A passing motorist, Domingo Benavides, is startled by the gunfire as he approaches Car #10 while traveling west on 10th. In an act of instinct and self-preservation, Benavides turns his pickup to the curb and ducks down behind the dashboard. (Lane, pp. 177-78)

Cabbie Bill Scoggins sees Tippit fall into the street. A few seconds later, he observes the figure of the young man walking quickly towards his cab, cutting across the adjacent corner property on 10th Street. Scoggins steps out of his cab and hides behind the driver-side fender. The young man emerges from the lawn’s hedges and begins to trot south on Patton Street, still tossing the occasional empty shell to the ground. (Lane, pp. 191-93)

Hearing no further shots, Benavides pokes his head up in time to see the gunman heading for Patton Street, inexplicably tossing a couple of shells into the bushes. Benavides will later tell police he could not positively identify the gunman and will not be taken to any of the subsequent lineups.

1:10:00 p.m.

The gunman turns right on Jefferson Boulevard, as seen by multiple witnesses. He stuffs the pistol back into his pants, walks briskly west for a block before cutting through a service station and turning north on Crawford Street. At this point the young gunman disappears. (Armstrong, p. 855)

Approximately 1:25 p.m.

“Someone” hands Captain William “Pinky” Westbrook a light tan Eisenhower jacket that was allegedly thrown under a parked car behind the Texaco service station at Jefferson & Crawford. This was supposedly the jacket worn by the fleeing gunman. Westbrook, however, can’t remember the name of the officer who turned over the jacket. (Lane, pp. 200-203)

“Someone” hands Captain William “Pinky” Westbrook a light tan Eisenhower jacket that was allegedly thrown under a parked car behind the Texaco service station at Jefferson & Crawford. This was supposedly the jacket worn by the fleeing gunman. Westbrook, however, can’t remember the name of the officer who turned over the jacket. (Lane, pp. 200-203)

Approximately 1:36 p.m.

As Dallas police cars continue swarming into Oak Cliff, the unidentified young man from 10th & Patton suddenly reappears again on Jefferson Blvd. near the Texas Theater. The man, who is wearing a white shirt, either purchases a ticket or simply ducks in without paying. The time is now approximately 1:37. Once inside, the new arrival goes upstairs to sit in the theater’s balcony section. (Armstrong, pp. 858-60)

Approximately 1:40-42 p.m.

Dallas police are tipped off to a suspicious person who has entered the Texas Theater.

Approximately 1:42 p.m.

At 10th & Patton, Captain Westbrook of the DPD shows FBI special agent Bob Barrett a man’s wallet. The Dallas investigators are going through the wallet, and apparently find two pieces of ID. Westbrook asks Barrett if he knows who either Lee Harvey Oswald or Alex Hiddell are. Barrett says no. (Armstrong, p. 856) Years later, when the story about the wallet is revealed by FBI personnel, the DPD will say that Barrett’s memory is faulty, there was no wallet found at the Tippit crime scene. But a check of archived Dallas TV news footage proved the DPD wrong. Later, the story seems to change that some unidentified person in the crowd at Tippit’s murder scene must have handed the wallet to reserve cop Sgt. Kenneth Croy, the first officer on site. Only none of the many Tippit witnesses reported seeing a wallet on the ground. Croy, incredibly, never filed a written report on 11/22/63. And Croy, in his testimony before the Warren Commission, said he knew several of the officers who eventually responded to the shooting at 10th and Patton—but couldn’t remember a single name of any of them.

At 10th & Patton, Captain Westbrook of the DPD shows FBI special agent Bob Barrett a man’s wallet. The Dallas investigators are going through the wallet, and apparently find two pieces of ID. Westbrook asks Barrett if he knows who either Lee Harvey Oswald or Alex Hiddell are. Barrett says no. (Armstrong, p. 856) Years later, when the story about the wallet is revealed by FBI personnel, the DPD will say that Barrett’s memory is faulty, there was no wallet found at the Tippit crime scene. But a check of archived Dallas TV news footage proved the DPD wrong. Later, the story seems to change that some unidentified person in the crowd at Tippit’s murder scene must have handed the wallet to reserve cop Sgt. Kenneth Croy, the first officer on site. Only none of the many Tippit witnesses reported seeing a wallet on the ground. Croy, incredibly, never filed a written report on 11/22/63. And Croy, in his testimony before the Warren Commission, said he knew several of the officers who eventually responded to the shooting at 10th and Patton—but couldn’t remember a single name of any of them.

1:45:43 p.m.

The DPD Channel 1 dispatcher broadcasts a report of a suspect who “just went into the Texas Theater.” A fleet of police cars, marked and unmarked, arrive to surround the theater front and back. (Armstrong, p. 863)

1:50-1:51 p.m.

Lee Oswald, still wearing his long-sleeved brown work shirt, is subdued in the main (downstairs) section of the theater by DPD officers and is whisked out the front door to a waiting unmarked police car.(Armstrong, p. 868) Meanwhile, a second slender young white male in a white t-shirt is arrested in the balcony and brought out the back door of the theater, as observed by Bernard Haire, the owner of the hobby store two doors east of the theater. The official Dallas arrest report will indicate that Oswald was arrested in the balcony, while in fact he was actually arrested downstairs in the theater’s ground-floor main section. (Armstrong, p. 871) What happened to the second man who was taken away?

Lee Oswald, still wearing his long-sleeved brown work shirt, is subdued in the main (downstairs) section of the theater by DPD officers and is whisked out the front door to a waiting unmarked police car.(Armstrong, p. 868) Meanwhile, a second slender young white male in a white t-shirt is arrested in the balcony and brought out the back door of the theater, as observed by Bernard Haire, the owner of the hobby store two doors east of the theater. The official Dallas arrest report will indicate that Oswald was arrested in the balcony, while in fact he was actually arrested downstairs in the theater’s ground-floor main section. (Armstrong, p. 871) What happened to the second man who was taken away?

Approximately 1:55 p.m.

While accompanied by four Dallas detectives in an unmarked car headed for DPD’s downtown headquarters, Oswald is asked to give his name. He ignores the request. Perturbed, Detective Paul Bentley pulls a billfold from Oswald’s hip pocket and begins to examine its contents. He finds ID cards for both a Lee Oswald and an A. Hidell. “Who are you?” asks Bentley again. “You’re the detective,” Oswald finally answers back. “You figure it out.” (Armstrong, p. 870)

But wait. They just found Oswald’s wallet at 10th & Patton, right? (Armstrong, p. 868) So Oswald carried two wallets, one of which he was good enough to leave at the Tippit murder scene? Along with four shell casings from a .38 caliber revolver?

In the words of an old Rockford Files TV episode: “that plant was so obvious someone should’ve watered it.” No wonder the 10th & Patton wallet disappeared after a billfold was found to have been in Oswald’s possession at the theater.

The Dallas Police knew who Oswald was before they descended on and surrounded the Texas Theater.

Approximately 2.p.m.

Oswald arrives at Dallas Police Headquarters to be interrogated and booked. He will be shot dead that very same weekend. To quote one bluntly sarcastic journalist: “Lee Oswald miraculously managed to survive nearly 48 hours in the custody of the Dallas Police Department.”

The DPD kept no known tapes or transcripts from the hours of interrogation undergone by their suspect. We have little idea what Oswald really said, only that he “emphatically denied these charges.” (Armstrong, p. 893)

Ballistics

If anyone is looking for ballistics to provide a definitive answer in the Tippit case, they will be sorely disappointed. The ballistics evidence tends to exonerate Lee Oswald as much as it implicates him. (For lengthy discussions of the following, see Henry Hurt, Reasonable Doubt, pp. 151-56 and Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, pp. 252-57)

If anyone is looking for ballistics to provide a definitive answer in the Tippit case, they will be sorely disappointed. The ballistics evidence tends to exonerate Lee Oswald as much as it implicates him. (For lengthy discussions of the following, see Henry Hurt, Reasonable Doubt, pp. 151-56 and Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, pp. 252-57)

Four shells from a .38 caliber handgun were recovered spread along the ground leading from the crime scene. The DPD officers on site at first figured these were from an automatic pistol (which automatically ejects the spent shells), not a revolver, because who would purposely remove and leave such incriminating evidence at the scene (along with a wallet full of ID)?

The bullets found in Officer Tippit’s body at autopsy could not be matched to Oswald’s .38. And the shells so conveniently recovered at 10th & Patton could not be matched to the bullets. The shells were never properly marked by DPD, evidence was misfiled, and the chain of evidence for the ballistics was, unfortunately, suspect.

In the words of homicide detective Jim Leavelle, the very man tasked with nailing Oswald for the Tippit murder, the ballistics in this case were quite frankly “a mess.”

As Joe McBride notes in his book, Warren Commissioner and congressman Hale Boggs was one of the members of that body who had his doubts about their verdict. Boggs directly challenged the Tippit case ballistics when he said, “What proof do you have that these are the bullets?” (McBride, p. 258) Boggs apparently never received a satisfactory answer.

New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison, who took an active role in the JFK assassination investigation in the late 1960s, believed that the ballistics evidence pointed to two shooters at 10th & Patton. Said Garrison in his October 1967 Playboy interview, “The evidence we’ve uncovered leads us to suspect that two men, neither of whom was Oswald, were the real murderers of Tippit.”

Mr. Garrison added that, “… Revolvers don’t eject cartridges and the cartridges left so conveniently on the street didn’t match the bullets in Tippit’s body.”

The cartridge cases—two Western-Winchester and two Remington–Peters—simply didn’t match the bullets—three Western–Winchester, one Remington-Peters—recovered from Officer Tippit’s body.

“The last time I looked,” noted Garrison wryly, “the Remington–Peters Manufacturing Company was not in the habit of slipping Winchester bullets into its cartridges, nor was the Winchester–Western Manufacturing Company putting Remington bullets into its cartridges.”

Witnesses

If the ballistics evidence in the Tippit case could rightly be characterized as messy, then the eyewitness testimony regarding the Tippit homicide would have to be labeled a toxic waste site by comparison.

If the ballistics evidence in the Tippit case could rightly be characterized as messy, then the eyewitness testimony regarding the Tippit homicide would have to be labeled a toxic waste site by comparison.

Tippit authority Joseph McBride, author of Into the Nightmare, explained the bizarre situation succinctly when he stated, “The other physical evidence is also confused and contradictory—and the eyewitness evidence is so contradictory that it seems as though there were two sets of witnesses.” (McBride, pp. 460-61)

One set of witnesses identified Oswald as the sole murderer of Officer Tippit. The second set said they couldn’t positively identify Oswald, or could positively exclude Oswald, and saw two or more suspects acting suspiciously, and even saw one of those persons apparently involved in the shooting escape in an automobile.

Dallas authorities, and later the Warren Commission, focused almost exclusively on the first set of witnesses—while minimizing or completely ignoring the second set.

A good example of “witness neglect” was reported by 10th Street neighbor Frank Wright. Wright later told Tippit researchers that “I was the first person out. I saw a man standing in front of the car. He was looking toward the man on the ground (Tippit). The man who was standing in front of him was about medium height. He had on a long coat, it ended just above his hands. I didn’t see any gun. He ran around on the passenger side of the police car. He ran as fast as he could go, and he got into his car. … He got into that car and he drove away as fast as he could see. … After that a whole lot of police came up. I tried to tell two or three people (officers) what I saw. They didn’t pay any attention. I’ve seen what came out on television and in the newspaper but I know that’s not what happened. I know a man drove off in a grey car. Nothing in the world’s going to change my opinion.” (Hurt, pp. 148-49)

Acquilla Clemons, a caregiver who worked on 10th Street, was not simply ignored the same as was Mr. Wright. Clemons, who saw two suspicious persons escape the Tippit murder scene in different directions, told investigator Mark Lane (during a taped interview) that a man she suspected was a Dallas detective or policeman visited her home on or about 11/24/63. He was carrying a sidearm. Mrs. Clemons reported that the visitor warned her “it’d be best if I didn’t say anything because I might get hurt … someone might hurt me.” (McBride, pp. 490-94)

Acquilla Clemons, a caregiver who worked on 10th Street, was not simply ignored the same as was Mr. Wright. Clemons, who saw two suspicious persons escape the Tippit murder scene in different directions, told investigator Mark Lane (during a taped interview) that a man she suspected was a Dallas detective or policeman visited her home on or about 11/24/63. He was carrying a sidearm. Mrs. Clemons reported that the visitor warned her “it’d be best if I didn’t say anything because I might get hurt … someone might hurt me.” (McBride, pp. 490-94)

Warren Reynolds, a used car salesman who saw the gunman escaping west on Jefferson Boulevard, was indeed hurt—and very badly. Reynolds told news reporters the afternoon of the assassination that he had seen the fleeing gunman, but was simply too far away to have made a positive identification. The FBI finally got around to interviewing Reynolds in January, 1964, at which time the witness reiterated his original story that he had been located across Jefferson Boulevard and was simply too far from the gunman to have made a positive identification. Two nights later, someone sneaked into Reynolds’ place of business, hid in the basement, and shot Mr. Reynolds in the head with a .22 caliber rifle. Miraculously, Reynolds survived. Even more miraculously, the car salesman made such a dramatic recovery that he now found his eyesight had improved and he was able to identify Lee Oswald after all. (Hurt, pp. 147-48; McBride pp. 476-78)

Warren Reynolds, a used car salesman who saw the gunman escaping west on Jefferson Boulevard, was indeed hurt—and very badly. Reynolds told news reporters the afternoon of the assassination that he had seen the fleeing gunman, but was simply too far away to have made a positive identification. The FBI finally got around to interviewing Reynolds in January, 1964, at which time the witness reiterated his original story that he had been located across Jefferson Boulevard and was simply too far from the gunman to have made a positive identification. Two nights later, someone sneaked into Reynolds’ place of business, hid in the basement, and shot Mr. Reynolds in the head with a .22 caliber rifle. Miraculously, Reynolds survived. Even more miraculously, the car salesman made such a dramatic recovery that he now found his eyesight had improved and he was able to identify Lee Oswald after all. (Hurt, pp. 147-48; McBride pp. 476-78)

Decades later, Dallas researcher Michael Brownlow tracked down Mr. Reynolds, who was still in the business of selling cars. At first, Reynolds would not admit who he was. But after Brownlow had gained his trust, the researcher asked Mr. Reynolds why he had suddenly changed his testimony regarding his identification of Oswald.

“Because I wanted to live,” Reynolds admitted bluntly.

When Mark Lane came to Dallas to make the documentary Rush to Judgment, his director, Emile de Antonio, made a rather interesting observation. “There was absolutely no tension at all on the scene of the assassination (Dealey Plaza),” commented de Antonio. “… All the tension is where Tippit was killed. That’s right and this (the Tippit slaying) is the key to it.” (McBride, pp. 460-61)

The director’s sense of what was going on in Oak Cliff was seemingly verified by an anonymous letter appearing in Playboy that was sent to the editor after Jim Garrison’s October 1967 Playboy magazine interview:

“I read Playboy’s Garrison interview with perhaps more interest than most readers. I was an eyewitness to the shooting of policeman Tippit in Dallas on the afternoon President Kennedy was murdered. I saw two men, neither of them resembling the pictures I later saw of Lee Harvey Oswald, shoot Tippit and run off in opposite directions. There were at least half a dozen other people who witnessed this. My wife convinced me that I should say nothing, since there were other eyewitnesses. Her advice and my cowardice undoubtedly have prolonged my life—or at least allowed me now to tell the true story…”

There were four main witnesses who gave testimony that Lee Oswald had in fact been guilty. Many who’ve studied the Tippit murder have long felt that competent defense counsel would have reduced the case against Lee Oswald to shambles. If Oswald had received a fair trial, they say, he would have been exonerated of the charge he killed Officer J.D. Tippit.

Of course, Oswald did not receive even the benefit of an unfair trial. The suspect received no trial whatsoever and was instead convicted in the court of public opinion based on government propaganda disseminated by a relentless disinformation campaign. In the words of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover on the evening of the assassination, “The thing I am concerned about, and so is Mr. Katzenbach (Deputy U.S. Attorney General), is having something issued so we can convince the public that Oswald is the real assassin.” (McBride, p. 142)

That “thing” mentioned by Hoover would eventually, of course, be the pre-determined, hastily prepared whitewash known as the Warren Report … with the so-called “magic” bullet as its centerpiece.

The four crucial witnesses against Oswald in the fatal Tippit incident would be William Scoggins, Ted Calloway, Helen Markham, and—belatedly—Jack Ray Tatum.

Taxi Driver Bill Scoggins

William “Bill” Scoggins was seated in his cab on Patton Street. (Warren Report, p. 166) He was facing the intersection with 10th Street, when he saw Officer Tippit’s patrol car pass by in front of him. (For discussions of Scoggins’ testimony, from which this material is drawn, see Meagher, pp. 256-57 and Lane, pp. 191-93) He saw no one walk by the front of his cab. The patrol car pulled to the curb on 10th Street approximately 100 feet east of the intersection. Mr. Scoggins’ vantage point was obscured by some bushes at the edge of the corner property on 10th. He suddenly noticed a pedestrian on the 10th Street sidewalk either turn around or walk over to the police car’s passenger side window. Scoggins resumed eating his lunch when, several seconds later, gunshots suddenly rang out. Scoggins, startled, looked up in time to see the officer fall into the street. Soon after the pedestrian, now brandishing a pistol, began walking in the direction of the cab. Scoggins exited his cab, thought about running away, but immediately realized he would be in the open and could not outrun any bullets. Instead, Scoggins opted to hide behind the driver-side fender of his cab. He saw the young man cut across the lawn on the corner property, squeezing through the bushes and stepping out onto the sidewalk very near the cab. Hunkered down by the fender, Scoggins heard the man mumble something like “Poor dumb cop.” He was afraid the gunman might try to steal the cab, but instead the young man proceeded on foot south on Patton towards Jefferson Blvd., crossing Patton at mid-block.

William “Bill” Scoggins was seated in his cab on Patton Street. (Warren Report, p. 166) He was facing the intersection with 10th Street, when he saw Officer Tippit’s patrol car pass by in front of him. (For discussions of Scoggins’ testimony, from which this material is drawn, see Meagher, pp. 256-57 and Lane, pp. 191-93) He saw no one walk by the front of his cab. The patrol car pulled to the curb on 10th Street approximately 100 feet east of the intersection. Mr. Scoggins’ vantage point was obscured by some bushes at the edge of the corner property on 10th. He suddenly noticed a pedestrian on the 10th Street sidewalk either turn around or walk over to the police car’s passenger side window. Scoggins resumed eating his lunch when, several seconds later, gunshots suddenly rang out. Scoggins, startled, looked up in time to see the officer fall into the street. Soon after the pedestrian, now brandishing a pistol, began walking in the direction of the cab. Scoggins exited his cab, thought about running away, but immediately realized he would be in the open and could not outrun any bullets. Instead, Scoggins opted to hide behind the driver-side fender of his cab. He saw the young man cut across the lawn on the corner property, squeezing through the bushes and stepping out onto the sidewalk very near the cab. Hunkered down by the fender, Scoggins heard the man mumble something like “Poor dumb cop.” He was afraid the gunman might try to steal the cab, but instead the young man proceeded on foot south on Patton towards Jefferson Blvd., crossing Patton at mid-block.

At the Saturday (next day) six-man police lineup, Mr. Scoggins picked Oswald as the individual he had briefly seen emerging from the bushes. However, fellow car driver William Whaley, who had driven Oswald from downtown Dallas to Oak Cliff the previous day, also attended the same lineup as Scoggins. Mr. Whaley made the following cogent observation regarding the nature of that DPD lineup. He testified before the Warren Commission that “… you could have picked him (Oswald) out without identifying him by just listening to him, because he was bawling out the policeman, telling them it wasn’t right to put him in line with these teenagers. … He showed no respect for the policemen, he told them what he thought about them. They knew what they were doing and they were trying to railroad him and he wanted his lawyer.”

Oswald, of course, had a visibly damaged eye, the result of his encounter with the DPD. Oswald was also asked to state his name and to tell where he worked. By Saturday, when Mr. Scoggins participated in this particular lineup, every functioning adult in Dallas and across the USA knew that the lead suspect in the assassination of JFK and the murder of Officer Tippit was a young man named Lee Harvey Oswald who worked at the Texas School Book Depository.

As Mr. Whaley duly noted, “you could have picked him out without identifying him.”

Mr. Scoggins, as it turns out, was actually not able to pick out Oswald during a separate photo lineup. In front of the Warren Commission, Scoggins said that he was shown photos of different men by either an FBI or Secret Service agent. “I think I picked the wrong one,” the cab driver testified. “He told me the other one was Oswald.”

It seems abundantly clear that Mr. Scoggins got only the briefest of glimpses of the gunman, while hiding in fear for his life on the opposite side of his cab. He was unable to identify Lee Oswald as the gunman in the absence of a highly tainted lineup.

And fellow cab driver William Whaley, who saw through the sham of these tainted DPD lineups and denounced them for what they were? Within two years of his Warren Commission testimony he would become the first Dallas taxi driver since 1937, while on duty, to fall victim to a fatal traffic accident.

Ted Calloway

After the Tippit gunman passed Bill Scoggins’s cab on Patton Street, he soon encountered used car lot manager Ted Calloway. Calloway, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, had heard the pistol shots and immediately began walking across the car lot towards Patton to investigate. (Warren Report, p. 169) He soon observed a young man heading south on Patton carrying a pistol in what Calloway would later describe as a “raised pistol position.” The young gunman, who noticed Calloway approach the east sidewalk on Patton, then crossed to the west side of the street to avoid the car salesman. (This following material is referenced in Meagher, p. 258 and Mc Bride, pp. 469-70)