It has been quite some time since a new book about the assassination of President Kennedy has piqued my interest enough for me to want to even read it, let alone write a review. Over recent years, I have grown increasingly tired of what I have come to see as an endless, false debate over the existence or non-existence of a conspiracy. More to the point, I have lost all patience for the ever-growing list of ill-supported theories, baseless claims of fakery/alteration of evidence, and the apocryphal stories that sadly appear to be firmly planted in the bedrock of most conspiracy thinking. Nonetheless, when I saw that Josiah Thompson’s long-awaited Last Second in Dallas was finally making its way into print, I immediately placed my order.

As most readers will no doubt be aware, Thompson is the author of one of the most influential books ever written about President Kennedy’s tragic murder, Six Seconds in Dallas. First published in 1967, Six Seconds in Dallas was a rare gem that managed to garner the respect of both Warren Commission zealots and critics alike. Even the late Vincent Bugliosi―who went to great lengths in his own tediously massive tome to denigrate virtually anyone and everyone who dared disagree with the Warren Commission’s conclusions―was compelled to refer to Thompson’s first book as a “serious and scholarly” work. (Reclaiming History, p. 484) In Six Seconds, Thompson presented readers with a meticulous study of the facts and evidence available to him at the time, leading to the almost inescapable conclusion that JFK had been shot by three different gunmen firing from three separate locations. While some of the precise details of his reconstruction of the shooting have since proven to be in error, Thompson’s overarching thesis has been entirely validated by later revelations and stands to this day as the most viable explanation of events.

Based on both the quality of Six Seconds In Dallas and my own pleasant exchanges with Thompson―during one of which he was kind enough to state that he felt my critique of Lucien Haag had the “depth and scholarly backup” to appear in a peer-reviewed journal (private email)―I was hoping for and, indeed, expecting big things from his follow-up work. It gives me great pleasure to be able to report that I was not disappointed. Last Second in Dallas is an eminently worthwhile addition to the literature that includes some game changing new research into one of the Kennedy assassination’s key pieces of evidence.

One remarkable facet of Last Second in Dallas is that it manages to present readers with a sizeable amount of detail while remaining, for the most part, eminently readable. This is perhaps largely due to the author’s decision to structure the book as a memoir of his time studying and investigating the case rather than as simply another dry recitation of facts. It is often said that anyone old enough to remember November 22, 1963, can tell you precisely where they were and what they were doing when they first learned that President Kennedy had been shot. In Thompson’s case, he recalls being at a street corner in New Haven, Connecticut, when he saw a woman run out of a record store yelling, “Kennedy’s been shot!” (p. 4) Like the rest of the nation, he then spent the hours that followed glued to news reports, feeling “strangely numb” as a bizarre sequence of events continued to unfold in Dallas, Texas.

The following evening Thompson and his wife, Nancy, attended a dinner party at the home of a European friend who offered his belief that Lee Harvey Oswald, the alleged Marxist-sympathiser who had been arrested within an hour of the assassination, “will never live to stand trial.” (ibid) Thompson dismissed his dinner companion’s comments off hand, remarking to his wife, “That’s just Alex. Europeans see conspiracies everywhere.” (p. 5) Yet only a matter of hours later Thompson would see his friend’s prophecy fulfilled when Oswald was gunned down by local nightclub owner, Jack Ruby, in front of news cameras in the basement of Dallas police headquarters.

A few days later, Thompson sat in his apartment studying the black-and-white Zapruder film frames published in the latest edition of LIFE magazine and noticed a curious discrepancy between the reports that had come from Parkland Hospital suggesting Kennedy had been shot from the front and the Zapruder stills showing that Oswald’s alleged sniper’s perch on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository was located directly behind the President when he was hit. The sense of unease he felt at this discovery led Thompson to the local FBI office where he found himself trying to explain the conflict to a Bureau agent who, Thompson noted, “listened politely” then “probably had a good laugh” after the author walked away. (p. 6)

Like most Americans, Thompson initially chose not to dwell on his suspicions. But in early 1965 his doubts about the official story were reignited by a series of articles appearing in left-wing periodicals Liberation and The Minority of One, written by a Philadelphia lawyer named Vincent Salandria. Salandria was an immediate skeptic of the near-instantaneous fingering of Oswald as the lone gunman. “I’m particularly sensitive to the possibilities of governments [sic] not being as diligent as they should in situations of this sort,” Salandria explained. “I guess it comes from my Italian peasant background which always disputes governmental action and is inherently skeptical.” (John Kelin, Praise from a Future Generation, p. 32) For The Minority of One, Salandria focused his attention on the Warren Commission’s infamous Single Bullet Theory and attempted “to establish finally and objectively that Kennedy and [Texas Governor, John] Connally were wounded by separate bullets.” (Ibid, p. 273) Thompson absorbed Salandria’s arguments, compared them to the evidence contained in the Commission’s twenty-six volumes of hearings and exhibits, and found that his criticisms were valid. “The more I read,” Thompson notes, “the more interested I became.” (Thompson, p. 7)

In January 1966, Thompson and a friend were arrested for “littering” in Delaware County after handing out anti-Vietnam war pamphlets against the wishes of the local sheriff. The pair spent a couple of hours in a cell before an American Civil Liberties Union attorney arrived to represent them. As Thompson and his fellow arrestee were brought into a squad room to meet with him, the lawyer loudly announced that he had been in touch with the Attorney General. “When the FBI agents arrive,” he said whilst looking at his watch, “I want you to tell them that not only have your civil rights been violated but you are suing for false arrest…” “He did a masterful job of bluffing,” Thompson recalled. “We were released in less than two minutes.” Once they were back out on the street, the ACLU attorney introduced himself; it was Vincent Salandria. (pp. 7–8)

This chance meeting was something of a turning point for Thompson. Salandria brought him into the small group of critics―figures now legendary among assassination scholars like Sylvia Meagher, Harold Weisberg, Penn Jones, Shirley Martin, Cyril Wecht, and Mary Ferrell―who were working hard to identify and publicise the myriad problems with the Warren Report. Then, in the summer of 1966, Thompson and Salandria began collaborating on what was intended to be a long magazine article. The pair began making trips to the National Archives in Washington and it was there that Thompson saw the Zapruder film for the first time. “I literally gasped aloud” Thompson writes, “as I watched the president’s head explode and snap backward as if his right temple had been struck by a baseball bat.” The author knew instinctively that what he was seeing had to be the result of a shot fired from the right front. And what is more, if the film were to be shown to the American public, he knew the majority would arrive at the same conclusion. (p. 10)

Sadly, the Thompson/Salandria collaboration did not last the summer. Natural disagreements over the evidence came to a head in an argument over the nature of the wound in Kennedy’s throat. Salandria was thoroughly convinced, based on the descriptions given by Parkland Hospital physicians, that the small, neat hole had to be a wound of entry. Thompson, on the other hand, felt that “The spinal column was only a few short inches behind that hole. Any bullet entering there must have shattered the spinal column before blowing a hole out the back of Kennedy’s neck.” (p. 97) Since there was no damage to the spine, he reasoned, there must be some other explanation for the wound.

As Salandria recalled in an interview for John Kelin’s wonderful book Praise from a Future Generation, “I immediately quit when Thompson tried to convince me that the Kennedy throat wound was a consequence of a bit of bone exiting from the throat which emanated from the head hit.” (Kelin, p. 340) According to Kelin, Salandria felt that Thompson’s postulate tended to exculpate the government and the attorney would go on to accuse Thompson of being a covert federal agent. In March 1968, Salandria wrote Thompson a letter stating, “I feel that you should know that I consider the data on whether you are a United States government agent incomplete, but that I entertain a suspicion at this time that you are.” According to Kelin, Thompson wrote back a short reply, telling Salandria he was “out of his goddam mind.” (ibid, p. 434)

With Salandria taking himself out of the picture, Thompson chose to carry on alone. By late August 1966, he had written a sixty-page draft that he planned to show to the editor of Harper’s magazine. Before that could happen, however, he found himself invited to lunch with publisher, Bernard Geis. “At the end of the lunch,” Thomson writes, “Geis asked [executive editor, Don] Preston to write up a contract for me. ‘You’re going to write a book for us, Thompson.’”

II

In October 1966, while Thompson was working on the manuscript that would become Six Seconds in Dallas, his publisher reached out to LIFE magazine to see if there was any interest in what Thompson was doing. As it turned out, following the commercial success of the books Rush to Judgment by Mark Lane and Inquest by Edward Epstein, LIFE was considering its own reinvestigation of the assassination. Thompson soon found himself teaming up with two associate editors at the magazine, Ed Kern and Dick Billings. This turned out to be an invaluable development for Thompson as it gave him access to the impressive resources of LIFE, chief among them, the Zapruder film. After viewing LIFE’s own high-quality copies of the film for the first time, Thompson was bowled over by what he saw and rushed to a phone to call his publisher’s office. “The Zapruder film is glorious” he exclaimed at the time. “You can see all the details. Connally was hit later…You can see the impact of the bullet on him. The single-bullet theory is dead…LIFE is going to break this all within a month!” (p. 19) Sadly, this would turn out not to be the case.

When the article appeared the following month, Thompson found that he was sorely disappointed. “Much of the material we had discovered had not made it into the article,” he writes, “and what had was watered down.” (p. 90) Nonetheless, teaming up with LIFE had not only given him access to the most important record of the assassination, but it had also taken him to Dallas to conduct interviews with some the most important witnesses to both the crime and its aftermath. This research would form the basis of his own book.

Six Seconds in Dallas was published to significant media attention in late 1967. Among its many contributions to our understanding of the assassination was a tabulation of 190 witnesses, detailing the location of each witness at the time of the shooting, how many shots they heard, and from which direction those shots appeared to come. Of those who offered an opinion, 52% believed shots had been fired from the infamous “grassy knoll” to the right front of the president’s limousine. (Six Seconds in Dallas, p. 24)

One of the most important of those witnesses was Union Terminal Railroad supervisor, Sam “Skinny” Holland. In Last Second in Dallas, Thompson presents some fascinating and, as far as I am aware, previously unpublished excerpts from the interview he and Ed Kern of LIFE magazine conducted with Holland in November of 1966. Holland, who had been standing on the railroad overpass overlooking Dealey Plaza during the assassination, recalled hearing at least four shots, one of which came from the grassy knoll and was accompanied by a puff of smoke that drifted between the trees in front of the stockade fence. When Kern told Holland that defenders of the Warren report had suggested that whatever Holland saw could not have been rifle smoke because “rifles no longer sent out puffs of white smoke” Holland, who had carried a gun for sixteen years as a special deputy to Sheriff Bill Decker, replied, “…you fire a gun, any gun, from a light underneath this shade you’ll see a puff of smoke that’ll linger there. It’ll be, just like I say, dim, like a cigarette or maybe a firecracker smoke, but mister, if it’s powder, it’s going to smoke.” (Last Second in Dallas, p. 75)

Holland and two other witnesses who also saw the smoke were so convinced that a shot had been fired from the knoll that, immediately after the shooting, they ran around to the spot behind the fence from where they believed the smoke had come to look for empty shells “or some indication that there was a rifleman or someone was over there.” (p. 71) What they found, according to Holland, was numerous footprints giving the impression that someone had paced back and forth and mud on a car bumper, “Exactly like someone was standing up there looking over the fence.” (p. 76)

As well as the lengthy analysis of eyewitness accounts in Six Seconds in Dallas, Thompson went into impressive detail concerning the conflicts in the medical evidence that existed at the time, many of which have still not been resolved today. One of those has to do with the question of whether the bullet which entered Kennedy’s back also exited his throat as the Warren Commission claimed it did. Thompson pointed to the testimony of Secret Service agents and the report of two FBI agents who were present at the autopsy as indicating that it did not. (Six Seconds in Dallas, pp. 42–51) Furthermore, as alluded to above, he used the testimony of the Parkland physicians, and the descriptions of Kennedy’s brain given by the autopsy doctors, to make a case for the throat wound being the result of a fragment of bullet or bone from the head shot. (ibid, pp. 52–56)

In addressing the ballistics evidence, Thompson pointed out that one of the empty rifle shells found on the sixth floor of the depository building had a dented lip which appeared to show that it could not have held a projectile on November 22, thus suggesting that only two shots had been fired from Oswald’s rifle. (ibid, p. 144) More crucially, he made a compelling case that Commission Exhibit 399―the so-called “magic bullet” that was alleged to have produced seven wounds in JFK and Governor Connally without sustaining any significant damage―was not found at Parkland Hospital as the Commission claimed. And, in fact, the actual bullet found at Parkland was a different caliber round that came off a stretcher that was in no way related to the assassination. (ibid, pp. 161–164)

Perhaps the most revelatory aspect of Six Seconds in Dallas was Thompson’s analysis of the Zapruder film. Because LIFE had refused the author permission to publish stills from the actual film, he was forced to use an artist’s renderings of the individual frames, something Thompson was understandably unhappy about. Yet it had surprisingly little impact on the effectiveness of his presentation. Thompson pointed out that a dramatic change in Connally’s demeanour occurred at Zapruder frame 238 when “his right shoulder collapses, his cheeks and face puff, and his hair becomes disarranged.” (ibid, p. 71) These involuntary responses appeared to pinpoint the very moment Connally was struck and seemingly occurred much too late to be associated with the bullet which had hit the president while he was hidden from view by the Stemmons freeway sign, sometime between frames 207 and 224. Together with CE399’s lack of provenance, this effectively destroyed the single bullet theory.

Thompson’s most important discovery, however, was related to the movement of Kennedy’s head. As noted above, on his initial viewings of the Zapruder film Thompson was struck, as most viewers are, by the violent backward movement of Kennedy’s head following the shocking explosion of his skull at frame 313, but a frame-by-frame analysis of the film revealed something else. Between frames 312 and 313, Kennedy’s head appears to move forward by at least two inches in just 1/18 of a second. (ibid, pp. 87–89) Absent any other explanation, Thompson interpreted the double movement he was seeing as evidence of two shots striking the head almost simultaneously.

Thompson’s discovery and measurement of this rapid forward movement was accepted by Warren Commission supporters and critics alike and this would have significant ramifications for our understanding of the assassination. Firstly, because it would become a fact that had to be assimilated in all future attempts to reconstruct the shooting. And secondly because, as we shall see later in this review, it was wrong.

III

In Last Second in Dallas, Thompson notes that media reaction to his first book was surprisingly positive. The Los Angeles Times, for example, called it “the most forceful, graphic, and well-organized argument for reopening the assassination investigation.” Similarly, Max Lerner of the New York Post was convinced enough by Thompson’s case for three assassins to write, “It was not until this book that I became clear in my mind about some kind of collaborative shooting.” (p. 110) But there was one notable figure who was not a fan of Thompson’s work: Nobel Prize-winning physicist, Luis Alvarez.

Alvarez had already staked his reputation on the Warren Commission’s lone gunman theory with his so-called “jiggle analysis” of the Zapruder film―a woefully inadequate study which, he claimed, demonstrated that episodes of blurring on the film showed the Commission had been correct in saying that only three shots had been fired. After being handed a copy of Six Seconds in Dallas, Alvarez set out to find a “real explanation” for the backward snap of Kennedy’s head. (p. 123) What he came up with came to be known as the “jet effect theory.”

In a nutshell, the jet effect theory holds that the explosive exiting of blood and brain matter from the right side of Kennedy’s skull pushed the head in the opposite direction. Although Alvarez apparently dreamed up this notion almost immediately, jotting down his calculations on the back on an envelope, he would not publish his theory until September 1976. At that time, in the pages of the American Journal of Physics, Alvarez claimed to have validated his hypothesis through a series of empirical tests that involved firing rifle bullets into melons. Towards the end of the paper, Alvarez stated that “a taped melon was our a priori best mock-up of a head, and it showed retrograde recoil in the first test.” (p. 129) His work could only be reasonably criticized, he said, had he used the “Edison technique” and shot at a large assortment of objects until he found one that behaved in accordance with his theory. Yet as Thompson discovered in the early 2000s when he got his hands on the raw data from Alvarez’s shooting experiments, that was precisely what the good doctor had done.

As Thompson details, during three separate rounds of testing, Alvarez had his rifleman fire into taped and untaped green and white melons of varying sizes, coconuts filled with Jell-O, one-gallon plastic jugs filled with Jell-O and water, an eleven-pound watermelon, taped and untapped pineapples, plastic bottles filled with water, and rubber balls filled with gelatin. The majority of these items were unsurprisingly sent hurtling downrange. Only after Alvarez reduced the size of his melons from ones weighing 4 to 7 pounds to ones weighing just 1.1 to 3.5 pounds did he get six out of seven melons to exhibit some retrograde motion. (pp. 124–125)

The melons he settled on may have behaved in the manner Alvarez wanted, but they were not, as he claimed, a “reasonable facsimile” of a human head. To begin with, melons weighing under 3.5 pounds are less than half the weight of the average human head, which usually weighs between 10 and 11 pounds. Furthermore, as Thompson writes, “Whether a melon is taped or not, a bullet will cut through its outside like butter. A human skull is completely different. Penetrating the thick skull bone requires considerable force, and that force is deposited in the skull as momentum.” (p. 125) If carefully selecting a poor facsimile of a human head because it produced the desired effect was not enough to nullify Alvarez’s test results on its own, the Nobel laureate also rigged his experiments at the other end by using 30.06, soft-nosed hunting bullets that struck their target at 1,000 feet per second faster than “Oswald’s” 6.5 mm, full metal jacket, Mannlicher Carcano rounds could have done.

As an explanation for the backward snap of Kennedy’s head, Alvarez’s jet effect theory is, at best, dubious science and, at worst, a deliberate charade designed to pull the wool over the eyes of the American public. Yet, as Thompson notes, it has become “part of the case’s folklore” and is still promoted today by defenders of the official story. For that reason, Thompson has done critics an invaluable service by publishing the details that Alvarez carefully omitted. Strangely, however, though Thompson devotes an entire chapter in Last Second in Dallas to Alvarez and his reaction to Six Seconds in Dallas, he makes no mention whatsoever of the equally, if not more important response by Attorney General Ramsey Clark.

Several years ago, in a superb online essay titled How Five Investigations into the JFK Medical Evidence Got It Wrong, Dr. Gary Aguilar revealed that Ramsey Clark had somehow come into possession of the galley proofs to Six Seconds in Dallas shortly before its publication. Clark was so disturbed by what he read that he ordered the formation of a panel of medical experts that, in the words of its chairman Russell Fisher, MD, was specifically intended to “refute some of the junk that was in [Thompson’s] book.”

On the one hand, the Clark Panel did what it was formed to do and reaffirmed the Warren Commission’s conclusions by stating that the medical evidence was consistent with Kennedy having been “struck by two bullets fired from above and behind him…” (ARRB MD1, p. 16) On the other hand, the panel’s report cast serious doubt on the reliability of the autopsy by suggesting that Kennedy’s pathologists had completely mislocated the entrance wound in the skull. According to the Clark Panel, the actual location of the wound was some four inches higher than as described in the official autopsy report!

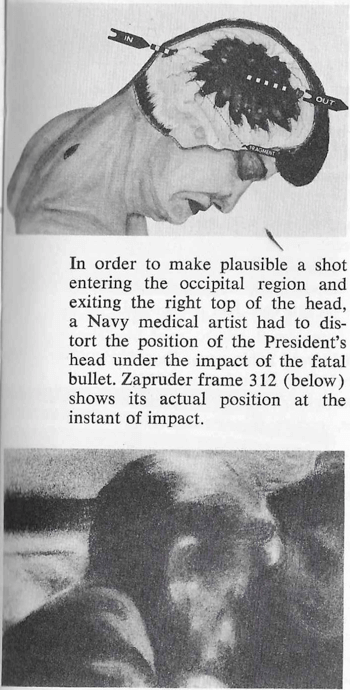

The autopsy surgeons, James J. Humes, J. Thornton Boswell, and Pierre Finck, had concluded in their report that the bullet had entered the skull “2.5 centimeters to the right and slightly above the external occipital protuberance.” To illustrate the path this bullet took through the skull, the Commission chose not to utilise the autopsy photographs or X-rays and instead published a drawing prepared under the direction of Dr. Humes. The problem with this drawing, as Thompson had pointed out in Six Seconds in Dallas, is that it shows President Kennedy’s head tilted drastically forward in a manner that is quite different to its actual position as seen in the Zapruder film. Furthermore, correcting the head’s position created an upward trajectory (see above comparison).

It may well be, as some critics believe, that Ramsey Clark expressed enough concern over this apparent trajectory problem that it prompted Fisher and his colleagues to move the wound up the skull to a position where, on the autopsy X-rays, the panel claimed it could see a “hole in profile” (an oxymoron if ever there was one!). This move would, of course, create a more downward trajectory, in line with Oswald’s alleged sniper’s perch on the sixth floor of the depository building. And yet the panel members were surely experienced enough to understand that the path of a bullet through the body after it strikes an object as dense as skull bone may well be significantly different to its trajectory prior to impact. Simply put, if a bullet strikes a hard surface, it is likely to deflect.

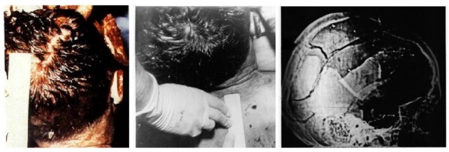

What may have been of greater concern to the Clark Panel members was the location of bullet fragments in the cranium. The autopsy report describes a trail of metallic particles traversing a line from the entrance wound in the occiput to the presumed exit point in the right front of the head. What the X-rays revealed to Fisher and his fellow panel members, however, was that the bullet fragments are actually located in the very top of the skull. This fact tends to confirm rather than refute Thompson’s double head shot scenario because a bullet entering the EOP could not create a trail of fragments along a pathway several inches higher than the one it took. Therefore, the fragments had to have come from a different bullet. Moving the entrance wound up the head as the Clark Panel did brought it closer―though still not in line with―the fragment trail.

Whichever of these considerations most plagued the Clark Panel, it seems clear that moving the entrance wound was done for reasons other than accuracy. Nearly three decades ago, experimental neuropathologist Joseph N. Riley, PhD―the only neuroscientist that I know of to have performed a serious study of Kennedy’s head wounds―concluded that “The original description of a rear entrance wound by Humes et al. …is most likely accurate” and that there was “little to support” the higher location. In support of this contention, Dr. Riley pointed out that the lateral X-ray shows an area of damaged skull that fully corresponds to the entrance location as described by Dr. Humes. (The Third Decade, vol 9 issue 3) In 2013, ballistics expert Larry Sturdivan and forensic pathologist Dr. Peter Cummings pointed to the very same area on the X-ray, noting that fractures clearly radiated from a point low down on the back of the skull. (NOVA Cold Case JFK)

For their part, the autopsy doctors always maintained that the wound was correctly located in their report. While it might seem obvious that few professionals are likely to relish the prospect of owning up to such a grievous error, it must nonetheless be borne in mind that the autopsy team had more than just the X-rays and photographs to work from; they had the actual body in front of them. As Dr. Finck argued, the observations of the autopsy doctors would, therefore, seem considerably more likely to be valid than those of individuals who might subsequently study the photos and x-rays. Perhaps more importantly, the entrance location identified by Humes et al. was corroborated by independent witnesses to the autopsy. For example, Richard Lipsey, aide to US Army General Wehle, told Andy Purdy of the HSCA that the wound was located “in the lower head…just inside the hairline.” Similarly, Secret Service Agent Roy Kellerman’s Warren Commission testimony placed it at the level of the lower third of the ear, “in the hairline.” (2H81) Both men executed drawings of their observations [see below].

All of this makes it surprising to me that Thompson appears to favour the higher location and writes matter-of-factly that “various forensic experts who studied the autopsy photos and X-rays all agreed that the autopsy had mistakenly located the hole…The true location was found to be over four inches above where the autopsy placed it.” (Last Second in Dallas, p. 262) It would appear to me that Thompson is swayed by the fact that the nine-member forensic pathology panel for the HSCA fully endorsed the Clark Panel’s higher in-shoot location. What he might not be aware of is that the majority of the HSCA panel members had enjoyed a close professional relationship with Clark Panel chairman, Russell Fisher. For example, Dr. Charles Petty had spent nine years under Fisher at the Maryland Medical Examiner’s Office. Dr. Werner Spitz had co-authored a book with Fisher, and HSCA panel chairman Dr. Michael Baden had contributed to that book. So, the obvious question that needs to be asked is just how likely was it that these men would work to actively undermine their colleague and mentor on such a prominent issue?

Ultimately, it may be said to be inconsequential which of the proposed entrance locations Thompson chooses to accept. After all, as Dr. Riley noted, and Thompson himself suggests, “the fundamental conclusion that John Kennedy’s head wounds could not have been caused by one bullet does not depend on which [in-shoot] description is more accurate.” Indeed, the fragments in the top of the skull, the two separate and disconnected areas of damage to the cortical and subcortical regions of the brain [as observed by Dr. Riley], the rear blowout documented by the Parkland physicians, the forward and rearward ejections of wound matter, and the backward snap of Kennedy’s head simply cannot all be explained by a single bullet fired from above and behind.

Whatever Thompson’s opinion on the in-shoot location may be, and whatever his reasons for it, I nonetheless find it surprising that the author makes no mention of the manner in which his first book precipitated the creation of the Clark panel and its revision of President Kennedy’s head wounds.

IV

On March 6, 1975, Geraldo Rivera’s late-night ABC TV show, Good Night America, featured photographic researcher Robert Groden showing his enhanced, stabilized version of the Zapruder film to the American public for the very first time. Thompson, who had also been asked to take part in one of Rivera’s JFK assassination segments, describes the broadcast as “a bona fide shocker…The characteristic intake of breath when an audience sees the president’s head explode and his body slammed backward was heard from coast to coast.” (pp. 138–139) Indeed, the public outcry that resulted from seeing this long-withheld evidence of a frontal shooter was tremendous. In the weeks and months that followed, Thompson worked with Groden to lobby members of congress in the hopes of establishing a committee to reinvestigate the assassination. Almost a year later, after much work from like-minded individuals, the HSCA was formed.

In the summer of 1977, Thompson was among a group of prominent critics who were invited to a two-day conference in Washington with HSCA Chief Counsel, Robert Blakey. In retrospect, it appears as if Blakey’s reason for arranging the conference was simply to make it appear as if he had given the critics a chance to have their say. The critics, of course, had numerous ideas on what should be the focus of the committee. Yet, as historian Jim DiEugenio writes, “In looking at the declassified summary of this meeting, what is striking about it is how few of the suggestions were actually pursued or how weakly they were pursued.” (The Assassinations, p. 67)

For his part, Thompson―whose focus has always been solely on the facts of the shooting itself―found himself largely bored by the whole affair. “The discussion veered into various claims of conspiracy,” he writes, “of which I had little interest and even less knowledge. As the discussion droned on, I found my mind wandering. Little did I know that in attending the conference, I would be present at one of the pivotal moments in the history of the whole case.” (Last Second in Dallas, p. 142) That moment came when Mary Ferrell first brought the acoustics evidence to Blakey’s attention. It was this piece of evidence that forced a conclusion of “probable conspiracy” on the committee.

The HSCA had begun promisingly enough under the leadership of Richard Sprague. From 1966 to 1974, he was the First Assistant District Attorney of Philadelphia County, during which time he had won convictions on 69 out of the 70 homicide cases he prosecuted. While a special prosecutor for Washington County, Pennsylvania, he had also exposed the conspiracy behind the brutal murders of American labor leader Joseph Yablonski and his family, who were shot to death by three gunmen as they slept in their home in Clarksville, Pennsylvania. On top of his impressive record, Sprague had no fixed opinion about who killed Kennedy and was determined to run an unbiased, independent investigation. As Dr. Cyril Wecht commented, “Dick Sprague was the ideal man for that job with the HSCA.” (The Assassinations, p. 56) Expectations in those early days were high and, as DiEugenio writes, “The feeling on the committee, and inside the research community, was that the JFK case was now going to get a really professional hearing.” (ibid)

Almost inevitably, Sprague’s tenure was short-lived. When the CIA began stonewalling the committee’s requests for information about a trip to Mexico City Oswald had supposedly taken two months before the assassination, Sprague said he would subpoena the Agency for the materials. What followed was a smear campaign in the pages of the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times and the Washington Post that resulted in Congress refusing to reauthorize the committee until the chief counsel was removed. To save the committee, Sprague resigned and Blakey was appointed in his place.

Former HSCA investigator Gaeton Fonzi noted in his highly-regarded book, The Last Investigation, that Blakey “was an experienced Capitol Hill man. He had worked not only at [the] Justice [Department] but on previous congressional committees as well. So, he knew exactly what the priorities of his job were by Washington standards, even before he stepped in.” Fonzi described those priorities thusly: “The first…was to produce a report within the time and budget restraints dictated by Congress. The second was to produce a report that looked good, one that appeared to be definitive and substantial.” Yet, as Fonzi notes, “There is substance and there is the illusion of substance. In Washington, it is often difficult to tell the difference.” (Fonzi, p. 8)

If there was one thing the HSCA report had in abundance it was the illusion of substance. This was especially true of one of the most important aspects of the committee’s case: The Neutron Activation Analysis of Dr Vincent Guinn.

NAA is a sophisticated technique involving a nuclear reactor that can be used to measure the “parts per million” of metal impurities in bullet lead. Guinn took the bullet fragments recovered from Kennedy’s head and Connally’s wrist, together with CE399 and the larger fragments found on the floor of the presidential limousine, and subjected them to this process. He then reported to the committee that Mannlicher Carcano bullets were virtually unique amongst unhardened lead bullets because they contained varying amounts of antimony. Furthermore, he claimed, the antimony levels in an individual bullet remained constant but were different from those in other bullets from the same box. This meant it was possible to trace a fragment to a specific bullet and even to distinguish it from other bullets of the same origin. Thus, Guinn testified, he had determined that the fragments from the floor of the limousine and the ones from Kennedy’s head had all come from one bullet, and the fragments from Connally’s wrist had come from CE399. In other words, only two bullets had struck President Kennedy and Governor Connally and they were both from Oswald’s rifle.

In Last Second in Dallas, Thompson shows that time has not been kind to Guinn’s conclusions or to NAA and bullet lead examination in general. To put it bluntly, it is now widely regarded as junk science. Comparative Bullet Lead Analysis, as the FBI called it, was used to gain convictions in hundreds of criminal cases over a span of more than two decades. But in 2002, Erik Randich―a PhD metallurgist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory―and several colleagues who had begun to have grave concerns about CBLA, published a serious critique of the process in the Forensic Science International journal. “Not surprisingly,” Thompson writes, “as word of these findings spread, criminal defense attorneys facing CBLA-produced evidence sought [Randich] out as an expert witness.” (p. 191)

At first, the FBI stubbornly refused to admit that there was reason for concern, issuing a statement that said, “We’ve been employing these methods and techniques for over 20 years in the FBI crime lab. They’ve been routinely subjected to vigorous defense scrutiny in the courts and we feel very confident that all of our methods are fully supported by scientific data.” (Los Angeles Times, Feb 3, 2003) However, continued challenges forced the Bureau to put the issue to the National Academy of Sciences and a team of experts was convened to review the issue. The NAS sided with Randich. Several months later, the FBI closed its CBLA lab, ordered agents not to testify on the issue in the future, and issued a statement to say CBLA was being discontinued. “With that announcement,” Thompson writes, “CBLA was formally thrown into the dust bin of junked theories and bogus methodologies.” (p. 191)

In July 2006, Randich and a PhD chemist named Pat Grant specifically addressed Guinn’s NAA testing of the Kennedy ballistics in the pages of the Journal of Forensic Science. After a devastating and authoritative deconstruction, Randich and Grant stated that there was “no justification for concluding that two, and only two, bullets were represented by the evidence.” And contrary to Guinn’s claims, not only could it not be established that the recovered bullet fragments were from Carcano ammunition, those fragments “could be reflective of anywhere between two and five different rounds fired in Dealey Plaza that day.”

Sadly, as Thompson points out, Guinn’s faulty analysis “prepared the ground for many of the committee’s conclusions…Because Guinn’s results were developed very early in the HSCA’s existence, their influence was felt throughout the committee’s work.” (pp. 168–170) Indeed, the committee’s forensic pathology panel admitted that it had considered Guinn’s NAA results when reaching its own conclusions. (7HSCA179) Even the panel’s lone dissenting member, Dr. Cyril Wecht, who had long believed that Kennedy may have been struck twice in the head, felt forced to admit after the NAA testing had been completed that “the possibility based on the existing evidence is extremely remote.” (1HSCA346) The NAA results, as Thompson articulates succinctly, “amounted to a gravitational pull towards the narrative put forward by the Warren Commission.” (ibid) It seems highly probable, therefore, that the HSCA would have issued a report stating that Oswald did it alone had it not been for the aforementioned acoustics evidence, first brought to the committee’s attention by Mary Ferrell.

The evidence in question consisted of Dallas police radio transmissions recorded on the day of the assassination. Specifically, a five-and one-half minute segment recorded by a police motorcycle in the presidential motorcade after its microphone had become stuck in the on position. Warren Commission critic Gary Shaw explained to Blakey at the critics’ conference that he and radio broadcaster Gary Mack had studied the recordings and believed they had discovered as many as seven gunshots coinciding with the time of the assassination. With this suggestion now on record, Blakey had little choice but to have the tapes analysed by acoustical experts. On the suggestion of the Society of American Acoustics, Blakey engaged the services of the Cambridge, Massachusetts firm of Bolt, Beranek and Newman, expecting that they would report back that it contained no gunshots. That would prove not to be the case.

After securing what were believed to be the original recordings, and conducting extensive analysis and on-site testing, BBN reported back that it had discovered five impulses that precisely matched the echo patterns of gunshots fired in Dealey Plaza. One of these impulses, the fourth in sequence, matched a gunshot fired from the grassy knoll. Shocked by the results, and afraid to stray too far from the Warren Commission’s conclusions, Blakey convinced the acoustic scientists to label one of these shots as a “false alarm.”

There is little doubt that the results of the acoustical analysis, which was completed shortly before the committee was expected to wrap up its inquiry, represented a significant problem for Blakey. As he remarked to HSCA investigator Dan Hardway after BBN delivered its report, “My god, we’ve proven a conspiracy and we’ve not investigated the conspirators.” (see Dan Hardway, Passing the Torch conference video, approx. 58:10) Ultimately, the HSCA report concluded that Oswald had fired three shots from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, causing all the injuries to President Kennedy and Governor Connally. A fourth shot, fired from the grassy knoll, had probably missed the limousine and its occupants altogether.

Upon reading the finished report in 1979, Thompson was struck by the schizophrenic nature of its conclusions. Specifically, by the way in which the NAA and the acoustics appeared to point to two entirely different solutions. Why, he asked himself, could it still not be determined what had really happened in Dealey Plaza? “There could be only one answer” he writes. “The evidence package was contaminated.” (p. 178) When asked to contribute to a book about the committee being compiled by Peter Dale Scott, Thompson wrote a 57-page chapter that reflected his confusion and then turned away from the subject. “I came to see that I was trying to put together a puzzle in which some of the pieces did not belong. Since I had no way of knowing which pieces these were, there was nothing I could do.” (p. 179)

V

Decades after the HSCA report was released, Thompson realized that Guinn’s Neutron Activation Analysis was not the only puzzle piece that did not belong. An equal, if not larger, impediment to making sense of the evidence was something that Thompson himself had introduced into the record in 1967. Namely, the 2.18-inch forward movement of Kennedy’s head between frames 312 and 313 of the Zapruder film. Thompson had been unable to reconcile this movement―and his own belief that this meant two shots had struck JFK’s head almost simultaneously―with the acoustics evidence, which dictated that only one shot had been fired at frame 313.

In 1998, Arthur Snyder, a Stanford physicist with a long-standing interest in the assassination, suggested to Thompson that his measurement was most likely in error. Snyder had performed some calculations and deduced that, in order for the president’s head to move forward 2.18-inches in one-eighteenth of a second, it would have had to have absorbed 90% of the bullet’s kinetic energy. “This was not just wildly improbable,” Thompson writes, “but impossible.” (p. 197) Several years later, he discovered the work of David Wimp, an Oregon-based systems analyst who had published a study concerning the effects of motion blurring in the Zapruder film.

What Wimp’s analysis highlighted was a basic principle of photography that Thompson had failed to consider. Simply put, if a camera is moved when the shutter is open, the brightest areas will intrude into the darkest areas. A perfect example of this can be seen in the Zapruder frames below which show how the very bright road intrudes into the much darker street light post, making it appear as if the post has gotten considerably thinner.

In the case of Zapruder frames 312 and 313, frame 312 is clear while 313 is smeared horizontally due to Abraham Zapruder moving his camera. As a result, all points of light in frame 313 are elongated horizontally, including the bright strip behind Kennedy which then intrudes into the back of his head.

What the above means is that the 2.18-inch forward movement Thompson believed he had measured in 1967 is, in reality, an optical illusion produced by the blur effect. It does not exist. Kennedy’s head does move forward between frames 312 and 313 but by a much smaller amount; approximately 0.95 inches according to Wimp’s measurements. This is roughly the same amount his head had moved forward between frames 310 and 312.

Furthermore, something else that Thompson apparently missed in 1967 is the fact that the Zapruder film shows all the occupants of the limousine moving forward at almost the same instant as Kennedy and continuing to do so after he is hurled backwards by the shot that exploded the right side of his head. (see this gif: Photobucket | Z308-323R3NS.gif) This movement is most likely a result of the limousine decelerating from 11 mph to 8 mph as the driver turned to look behind him. Clearly then, prior to his being struck by a bullet from the knoll, any forward motion Kennedy exhibited was a result of the very same force which affected everyone else in the vehicle. What all of this means, as Thompson writes, is that “the movement of JFK’s head between 312 and 313 can no longer be taken as the impact of anything.” (p. 202) The explosion of blood, brain and skull seen in frame 313 can be ascribed solely to the knoll shot captured on the Dallas police dictabelt recording.

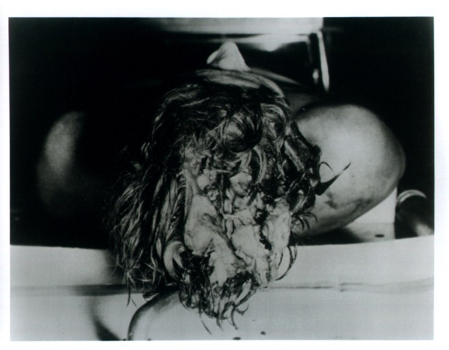

This realization left Thompson with one important question: when was Kennedy’s head struck from behind? The answer came for him in 2005 through a New Hampshire manufacturer’s representative named Keith Fitzgerald. What Fitzgerald had noticed was that the most dramatic forward movement of Kennedy’s head occurred 0.8 seconds after the knoll shot struck. Between Zapruder frames 327 and 330, JFK’s head moved forward 6.44 inches. (p. 221) Furthermore, during the several frames succeeding frame 327, the appearance of the head wound can be seen to change significantly. There is no dramatic explosion comparable to the one seen in frame 313 because the pressure vessel of the skull has already been compromised. However, between frames 327 and 329, additional blood and matter is seen to be driven from the front of the head. By frame 337, as Thompson shows, the wound looks significantly different from how it appeared just ten frames earlier. (see frame comparison on p. 229)

Coincidently, Robert Groden, the man most responsible for bringing the Zapruder film to the attention of the public, has made the very same observations as Fitzgerald. In 2013, during a presentation given at the Cyril H. Wecht Institute of Forensic Science and Law, Groden showed his audience the following slide, highlighting the forward gush of blood and matter described above (pay particular attention to the obscuring of Jackie Kennedy’s lapel):

Not coincidentally, this visual evidence of a probable second head shot at frame 327 is mirrored by the Dallas police dictabelt recording which contains the sound of a gunshot fired from behind the limousine 0.8 seconds after the sound of a gunshot fired from the grassy knoll. In other words, the exact same spacing and sequence of shots is found on both the audio and visual evidence.

VI

This brings us nicely to what I believe is the most valuable facet of Last Second in Dallas: Thompson’s reaffirmation of the acoustics evidence through the complete debunking of the Ramsey Panel. For those unfamiliar with the history of the acoustics evidence, the Ramsey Panel was commissioned by the Justice Department within months of the HSCA issuing its report, specifically to address the committee’s conclusion that “Scientific acoustical evidence establishes a high probability that two gunmen fired at President John F. Kennedy.” (HSCA report, p. 3) The Ad Hoc Committee on Ballistic Acoustics, to use its formal name, acted under the auspices of the National Academy of Sciences and issued a report in 1982 concluding, predictably enough, that the impulses identified by BBN were not gunshots. (Thompson, p. 300)

To understand that the panel was never meant to give the acoustics a fair assessment but was, in fact, formed specifically for the purpose of shooting down the HSCA’s historic findings, one need only learn that the Justice Department initially offered the chairmanship to Luis Alvarez. This, of course, is the same Luis Alvarez who had previously concocted the jet effect theory in support of the Warren Commission’s conclusions and hidden the results of his own tests. He had also, as Thompson points out, served on numerous government committees dealing with matters of “national security.” (p. 286) Perhaps more crucially, he had pooh-poohed the acoustics before getting anywhere near the evidence, telling the press he was “simply amazed that anyone would take such evidence seriously.” (ibid)

Perhaps realising that his name being so overtly connected with the panel would invite closer scrutiny of its findings, Alvarez declined the chair. Instead, he recommended his friend and colleague, Harvard physicist Norman Ramsey for the position. Nonetheless, Alvarez stayed on as a member of the panel and was, by his own account, its most active participant. (Donald Thomas, Hear No Evil, p. 618) It is readily apparent that the conclusions of the panel, which did not include a single acoustics expert, were preordained. In fact, according to Dr Barger, when he met with the panel to discuss his work, Alvarez told him that “he didn’t care what I said, he would vote against me anyway.” (Thompson, p. 287)

The Ramsey Panel spent a year intensely scrutinising BBN’s work, looking for serious flaws and finding none. Then, in January 1981, a gift horse arrived in the form of twenty-five-year-old department store worker, Steve Barber. To understand Barber’s contribution, it is important to understand that on the day of the assassination, the Dallas police were using two radio channels that were recorded on antiquated equipment. Channel 1, which was for routine police communications, was recorded on a Dictaphone belt recorder. Channel 2, which was reserved on November 22 for the president’s motorcycle escort, used a Gray Audograph disc recorder. Both were eccentric pieces of equipment that used a stylus cutting an acoustical groove into a soft vinyl surface to make recordings.

Listening intently to a copy of the relevant portion of the Dallas police channel 1 recording that he got free with a copy of Gallery magazine, Barber noticed something that no one else had heard. At the very point on the recording that the shot sequence occurs, Barber heard a faint voice saying, “hold everything secure.” When he checked his discovery against a copy of the channel 2 recording that he had acquired from assassination researcher Robert Cutler, Barber heard the more distinct sound of Sheriff Decker saying “hold everything secure until homicide and other detectives can get there…” What made this discovery significant was that this broadcast by Decker appeared on the channel 2 recording around one minute after the assassination.

The Ramsey Panel seized Barber’s discovery with both hands, stating that what he had found was an instance of “crosstalk.” As the panel explained it, crosstalk was something that occurred if an open police microphone came close enough to another police radio receiver to pick up and record its transmission. Accordingly, the panel suggested that the Decker broadcast could only have been deposited on the channel 1 recording because the police motorcycle with the stuck microphone had been close to another police radio at the time the broadcast was made to pick it up. Therefore, whatever the impulses BBN analysed were, they could not be the gunshots that killed Kennedy because they occurred one minute after the assassination.

For nearly two decades following the publication of the Ramsey Panel’s report, the acoustics was essentially a dead issue. As Thompson writes, “Among the establishment cognoscenti…the acoustics evidence could now be viewed as a scientific aberration, a regrettable mistake exposed by the distinguished scientists of the Ramsey Panel.” (p. 301) However, in 2001, a paper published in the British forensic journal, Science & Justice, reignited the debate. Its author, US federal government scientist Donald Thomas PhD, pointed out that the Ramsey Panel had overlooked a second instance of crosstalk, the “Bellah broadcast,” and that using this second broadcast to synchronize the transmissions placed the impulses “at the exact instant that John F. Kennedy was assassinated.” (see full article here: Thomas.pdf (jfklancer.com)) Three years later, Ralph Linsker of the IBM Watson Research Center and the surviving members of the Ramsey Panel responded by denying that the Bellah broadcast was crosstalk, claiming that although the same words―”I’ll check it”―appeared on both channels, their own tests showed that “they were spoken separately, and at different times.” (Thompson, p. 319) Once again, an impasse of sorts had been reached.

Thankfully, in Last Second in Dallas, Thompson has laid this entire matter to rest. As he details across two brilliant chapters near the end of the book, Thompson reached out in 2015 to BBN’s lead scientist, James Barger, asking if he could recommend someone to perform the necessary tests on the Bellah broadcast. As Thompson notes, Dr. Barger is a “towering figure” in the field of acoustics. The very reason he and his team were recommended to the HSCA in the first place is because their work on the Kent State shooting had helped establish that the National Guard had shot first. More recently, Barger and BBN designed the Boomerang anti-sniper devices that were used on US military vehicles in Iraq.

One of the tests upon which Linsker et al. had placed great emphasis was a process called pattern cross-correlation (PCC). In audio signal processing, PCC is used to measure the similarity between two audio samples. Software runs the two samples at various speeds and, if there is a match, will produce an obvious peak, demonstrating the level of the match. The panel noted that it had performed the PCC test on the Decker and Bellah broadcasts, alongside another instance of crosstalk in which Dallas police chief Jesse Curry can be heard to say, “You want me…Stemmons?” However, although Linsker et al. provided PCC peaks for “Hold everything secure…” and “You want me…Stemmons?”, it failed to disclose the results for “I’ll check it.”

To review the tests performed by Linsker and the Ramsey panel, Barger recommended a veteran BBN engineer named Richard Mullen, who began by noting that Linsker et al had made the mistake of using an inappropriate sampling window. As Thompson explains, “Apparently Linsker used the same 512 sampling window for all three crosstalks. This might make sense for ‘Hold everything secure’ (2.1 seconds) or for ‘You want me…Stemmons?’ (4.0 seconds), but it is much too long for ‘I’ll check it’ (0.6 seconds).” (p. 326) When Mullen performed the PCC test himself using a more appropriate window length, the results, as Thompson writes, “showed conclusively that ‘I’ll check it’ not only is crosstalk but has a higher net PCC peak than ‘Hold everything.’ With this finding, the Linsker et al. argument from 2005 imploded―and with it the whole house of cards constructed by the 1982 Ramsey Panel.” (p. 329) Don Thomas had been absolutely correct, the Bellah broadcast placed the suspect impulses on the dictabelt at the exact moment Kennedy was killed.

This, of course, leaves open the question of why the Decker broadcast appears on the channel 1 recording, concurrent with the sounds of the rifle shots that killed Kennedy. The answer, Thompson reveals, is that it is an overdub. Barger himself had raised this possibility and asked Mullen to examine the various background hum frequencies on both the channel 1 and channel 2 recordings to confirm or refute it.

To understand Barger’s request, it is necessary to understand that antique analogue recorders like the Dictaphone and Audograph produced a 60-Hz background hum. But because both machines could be played back at varying speeds, if they were played back to a tape recorder using anything other than the precise, original recording speed, this would generate a unique hum frequency which would remain on all subsequent copies. Furthermore, if a tape recorder were used to make a copy of this second-generation copy, it would contain a secondary hum frequency that would, in turn, appear on all future copies.

When Mullen analysed the background frequencies on both Dallas police channel recordings, he found two different secondary hums on channel 2 that were of the same frequency as those found on channel 1. As Dr Barger explained, the two hum frequencies on channel 2 indicated that the tapes came from a second generation Audograph disc. The fact that the Decker broadcast on channel 1 contains both of these hum frequencies is, in Barger’s words, “proof that the HOLD family of crosstalk was overdubbed onto Channel 1.” (p. 346)

With that, Thompson, Barger, and Mullen have delivered the deathblow to the Ramsey Panel report. There is no longer any significant reason for doubting the validity of the acoustics evidence, which now stands stronger than ever as scientific proof that President John F. Kennedy was killed by a conspiracy involving multiple assassins.

VII

This has been a fairly lengthy review and, it is fair to say, an overwhelmingly positive one. In the interests of balance, I have looked hard in Last Second in Dallas for faulty reasoning, misstatements of fact, or other reasons to be critical. The reality, however, is that aside from my disagreement with Thompson over the location of the entry wound in the back of Kennedy’s head, and my surprise that he made no mention of how his first book influenced the creation of the Clark Panel, any criticisms I could make would be extremely minor.

I could perhaps take exception to his characterisation of the investigation of New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison as a “circus” and to his opinion that the case against Clay Shaw “seemed preposterous.” (p. 112) After all, through the numerous documents relating to Garrison’s probe that were released by the Assassination Records Review Board, we now know that Garrison was correct in many of his charges. There can no longer be any reasonable doubt that Shaw was a paid asset of the CIA or that he indeed went by the alias of Clay Bertrand. Furthermore, the government-led media campaign to destroy Garrison’s reputation and hamper his investigation is now exceedingly well documented. So much so that legendary Warren Commission critic Mary Ferrell, who had been a staunch critic of Garrison for decades, was forced to concede in her later years that “he was so close and they did everything in the world to destroy him.” (Joan Mellen, A Farewell to Justice, p. 383)

However, the reality is that these are only passing references in Thompson’s book that are by no means germane to its central considerations. Thompson fully admits that “From the outset, I had no interest in the conspiracy theories making the rounds. People could argue these things forever, yet I doubted that any of them could be proven.” (p. 27) For that reason, I would be surprised if Thompson is even aware of, let alone familiar with, much of the documentation that has cast the Garrison probe in a different light.

There are essentially two schools of thought when it comes to how best to approach the assassination. There are those, like journalist Anthony Summers, who believe that science can provide no certainties and, therefore, the answers must lie in close studies of Oswald’s background and associations, and of the assassination’s wider political context. Then there are those, like Dr Cyril Wecht, who feel that it is through establishing the way the shooting occurred that certainty can be obtained. I, for one, do not fault Thompson for belonging to the latter camp.

Last Second in Dallas is likely to be criticised, or outright dismissed, by those who cling to outdated arguments or unfounded beliefs, such as the inexplicably popular theory that the Zapruder film is a forgery, or that the X-rays have been altered to hide a blowout in the back of the head. In some ways I would have liked to have seen Thompson pre-empt these arguments by providing the details that establish the authenticity of the evidence. But then, in so doing, not only would he have taken casual readers down the rabbit hole unnecessarily, but he would also have given such arguments a legitimacy they do not deserve.

In my own two decades as a student of the Kennedy assassination I have heard many silly arguments, one of them being that the acoustics evidence was “designed to fall apart.” I am sure that there are readers out there who are familiar with the intricacies of the acoustic data and, like myself, are scratching their heads wondering how on earth such a feat could possibly be achieved. In any case, I do not doubt that the type of person capable of subscribing to such nonsensical ideas will have no problem disregarding Thompson’s impressive achievement in this area, or otherwise failing to grasp its significance. But I also do not doubt that history will thank him for his efforts.

Just as I am sure history will thank him for owning up to and correcting his own error regarding the forward movement of Kennedy’s head and, in so doing, demonstrating how perfectly the audio and visual evidence fits together. It may well be, as Thompson suggests, that the gaps and contradictions that still exist in the evidence today preclude a definitive reconstruction of the entire assassination sequence. However, I do believe it can rightly be said that Last Second in Dallas lives up to the promise of its title and establishes to a high degree of probability exactly how that final second went down. Once again, I am confident that history will thank him for it.

And that is precisely what I intend to do.

GLAZE, Elzie Dean Age 66, is celebrated by his family for his compassion, humor and willingness to help family, friends and the world at large. He was an accomplished journalist and author and had worked as a radio engineer in his early career. For many years he assisted organizations that helped veterans, monitored the nuclear power industry, and worked to ensure basic human rights. He had keen interests in history and weather, and much of his writing related to these. He followed environmental concerns and space exploration, and he enjoyed playing and watching sports. He was fortunate to have many travels, including celebration of his 60th birthday in Antarctica. Dean was the son of Elzie L. Glaze and Geneva I. Glaze and was born in Lubbock, Texas. He passed away on November 15, 2019, after a fall causing brain injury. He is loved and will always be remembered by his wife Sylvia Glaze, daughter Hailey Glaze, and sister, brothers, nieces, nephews and friends. He enjoyed giving to others, and loved the companionship of his four dogs. Many notes and gifts, often created by him, are left for us as a tribute to his kindness and love.

GLAZE, Elzie Dean Age 66, is celebrated by his family for his compassion, humor and willingness to help family, friends and the world at large. He was an accomplished journalist and author and had worked as a radio engineer in his early career. For many years he assisted organizations that helped veterans, monitored the nuclear power industry, and worked to ensure basic human rights. He had keen interests in history and weather, and much of his writing related to these. He followed environmental concerns and space exploration, and he enjoyed playing and watching sports. He was fortunate to have many travels, including celebration of his 60th birthday in Antarctica. Dean was the son of Elzie L. Glaze and Geneva I. Glaze and was born in Lubbock, Texas. He passed away on November 15, 2019, after a fall causing brain injury. He is loved and will always be remembered by his wife Sylvia Glaze, daughter Hailey Glaze, and sister, brothers, nieces, nephews and friends. He enjoyed giving to others, and loved the companionship of his four dogs. Many notes and gifts, often created by him, are left for us as a tribute to his kindness and love.