Another dispute Thompson had with Vince Salandria was the author’s theory about the small hole in JFK’s throat. On the day of the assassination, Dr. Malcolm Perry said to the public that this appeared to be an entrance wound. Thompson’s idea is that it was a piece of either brain or metal ejected from Kennedy’s skull. And he includes a diagram of this on page 98. The trajectory of this projectile is hard to fathom, especially since it would be traveling through soft tissue. But also, once it went into the throat area, it would be entering into all kinds of small bones and thicker cartilage. So in addition to the trajectory, it found an exit path through that maze?

Thompson takes Howard Brennan at his word. (pp. 98-99) Which he also did in his previous JFK book. I am not going to go into the myriad problems with Brennan as a witness. That would be redundant of too many good writers. Let me say this: today, the best one can say about Brennan is that he was looking at the wrong building. The worst one could say is that he was rehearsed and suborned. As Vince Palamara wrote in Honest Answers, Brennan refused to appear before the House Select Committee on Assassinations. Beyond that, he would not answer written questions. When they said they would have to subpoena him, he replied he would fight the subpoena. Does this sound like a straightforward, credible witness? (Palamara, pp. 186-89)

To supplement the dubious Brennan, the author uses the testimony of the three workers underneath the sixth floor. Vincent Bugliosi used one of them in a mock trial of Lee Oswald in England in 1986. I addressed the serious problem with using these men––in Bugliosi’s case it was Harold Norman––in my book The JFK Assassination: The Evidence Today. (pp. 54-55) To make a long story short, after they were interviewed by the FBI, their stories were altered by the Secret Service. At that mock trial, Norman could have been taken apart and spat out if defense lawyer Gerry Spence had been prepared––which he was not. (For a long version of how and why this happened, see Secret Service Report 491)

Let me add one key point about this. One of the Secret Service agents involved in this mutation was Elmer Moore, a man who––since the declassifications of the ARRB––has become infamous in the literature. There is little doubt today, in the wake of the declassified files, that Moore was an important part of the coverup. (DiEugenio, pp. 166-69) Therefore, in my view, Thompson missed another pattern––one which could have been indicated to him by Gary Aguilar or Pat Speer, in addition to myself.

The middle part of the book narrates much of the case history from the early to late seventies. For Thompson, this means the first showings of the Zapruder film by Bob Groden at conferences, then the big national showing on ABC in 1975. This was one of the factors that spurred the creation of the HSCA in 1976. Thompson says that he was invited to the so called HSCA “critics conference.” He says this was where he first heard of the dictabelt tape of a motorcycle recording of the assassination. He takes the opportunity to tell us how the HSCA actually recovered the tape. He also explains how it worked and some of the technology behind it. (pp. 147-51) Keeping with his personal journey aspect, in this part of the book he also tells us how he decided to give up his professorship at Haverford and become a private investigator.

From 1979 until 2006 the author tells us he was very little involved with the case. (pp. 182-83) This is kind of surprising when one thinks about it. Thompson all but leaves out the yearlong furor that took place over the release of Oliver Stone’s film JFK. Which is odd, since that was the largest period of focused attention the case got since 1975. All he says is that he was called to testify by the Assassination Records Review Board about their purchase of the Zapruder film. And he testified, properly I think, that once the Secret Service knew about the film it should have gone to Abraham Zapruder’s home and taken possession of it right there as a piece of evidence in a homicide case. (pp. 189-90) About any of the rather startling disclosures of the ARRB, I could detect little or nothing.

He spends several pages on a conference organized by Gary Aguilar in San Francisco which featured Eric Randich and Pat Grant. It was these two men who broke open the whole mythology of Vincent Guinn’s Neutron Activation Analysis, today called Comparative Bullet Lead Analysis. I was at that conference and Thompson does a good enough job summing up their scientific findings. (pp. 190-96). As the author notes, this “junk science” had been important to the HSCA in its findings that somehow Oswald alone did the shooting, and the acoustical second shot from the front missed.

II

In the second half of the book Thompson more or less forsakes the personal journey motif. He concentrates on what he sees as three important pieces of evidence, which he figures are crucial to the case. I will deal with each of these as candidly and completely as I can.

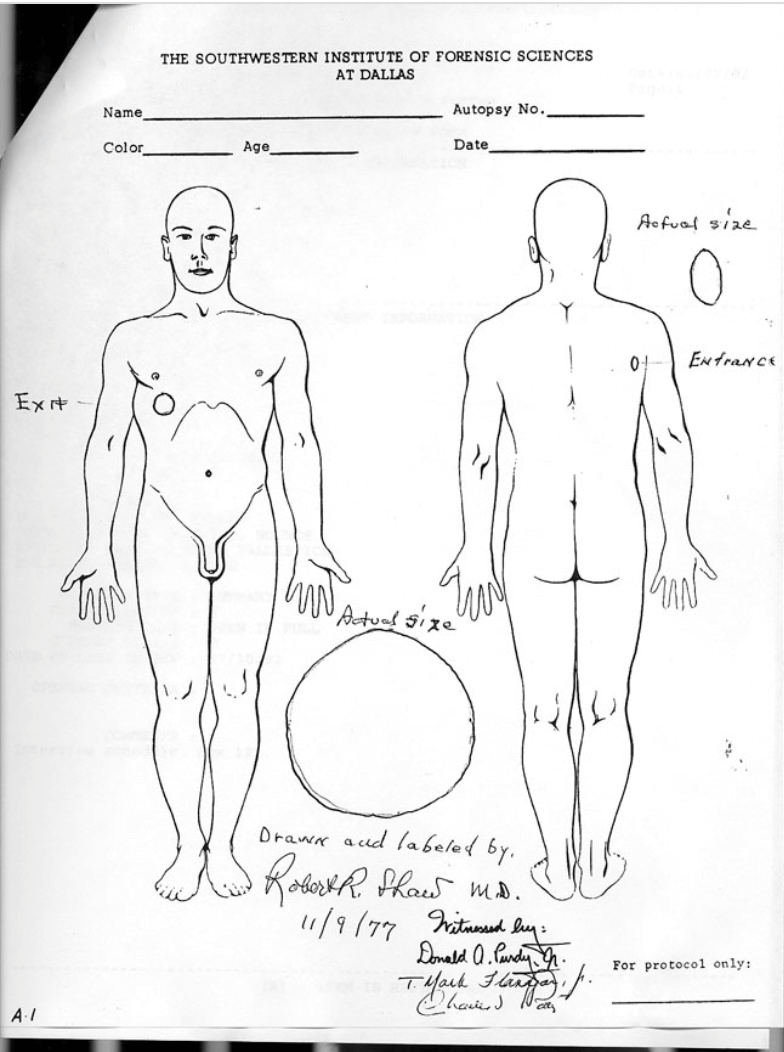

Thompson devotes Chapter 16, well over twenty pages, to the medical evidence in the JFK case. He begins this part of his book by declaring that the JFK autopsy was “botched,” in other words, whatever shortcomings there were in that procedure, they were not by design. I was rather surprised by this supposition, for the simple reason that Dr. Pierre Finck said under oath at the trial of Clay Shaw that the reason the back wound was not dissected is because the military brass in the room stopped them from doing so. He also said that James Humes, the chief pathologist, was not running the proceedings. They were being so obstructed that Humes literally had to shout out, “Who’s in charge here?” Finck testified that an Army general replied, “I am.” Finck summed up the situation like this:

You must understand that in those circumstances, there were law enforcement officials, military people with various ranks, and you have to coordinate the operations according to directions. (James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed, p. 300, italics added)

The Department of Justice––among other groups––was monitoring the Clay Shaw trial in close to real time. When Carl Eardley, the Justice Department specialist on the JFK case, heard this, he almost had a hernia. He called up another of the pathologists, Thornton Boswell, and sent him to New Orleans, since they now had to discredit Finck for revealing what had happened. Eardley later thought better of this, probably because by any standard measure, Finck had better qualifications as a forensic pathologist then Boswell did. (ibid, p. 304)

One cannot overrate the importance of this testimony. To give just one indication of its importance: I did a pre-interview with Dr. Henry Lee for Oliver Stone’s new documentary on the JFK case. I asked him this specific question, directly related to Finck’s testimony: Can you figure out a firing trajectory without a tracking of the wound? He said that under those circumstances, it was very difficult to do. Here is a man who has worked about 8000 cases all over the world and is recognized as one of the best criminalists alive.

The same situation applies to the skull wound, except in this case, the situation is more complex. If one talks to Lee or Cyril Wecht they will tell you there is no evidence of a brain sectioning. But the Review Board did an inquiry into this subject, and Jeremy Gunn and Doug Horne came up with some evidence that such an examination may have been done. Under the scope of this particular review, this is not the place to do an expansive analysis of their evidence. Suffice it to say I found Thompson’s excuse for this lack rather strained: the doctors did not have the time to do so such a thing. (Thompson, p. 259) Yet in the Commission’s volumes there is a brain examination, dated 12/6/63. (CE 391) And there is no mention of sectioning; two weeks was not long enough? Yet without sectioning, how can one determine the bullets’ paths? On this matter, Lee was quite animated. He put his right hand up in front of his face and said words to the effect: You have this bullet coming in at a right to left angle: it then reverses itself and goes left to right? The lack of dissection in this instance is even more perplexing because the head wounding was how Kennedy was killed. And this is why Lee’s hand was piercing the air in bewilderment.

III

Thompson wrote something later that stunned me. On page 258 he says that the first time the autopsy doctors learned of a tracheostomy over the anterior neck wound was when they read about it in the next day’s newspapers. That passage is undermined by Nurse Audrey Bell’s 1997 testimony to the Review Board. Bell told them that Dr. Malcolm Perry complained to her the next morning (on Saturday, November 23rd) that he had been virtually sleepless, “because unnamed persons at Bethesda had been pressuring him on the telephone all night long to get him to change his opinion about the nature of the bullet wound in the throat, and to redescribe it as an exit, rather than an entrance.” (See DiEugenio, The JFK Assassination: The Evidence Today, pp. 167-68; also this discussion)

In a very late discovery by writer Rob Couteau, Bell’s testimony was both certified and expanded. In the days following the assassination, many reporters were milling around Dallas, and some found their way to Malcolm Perry’s home, for the reason that he and Dr. Kemp Clark had held a press conference on the day of the assassination where Clark said there was a large, gaping wound in the back of Kennedy’s skull, and Perry said the anterior neck wound appeared to be one of entrance. One of the reporters who migrated to Perry’s home was from the New York Herald Tribune and his name was Martin Steadman. He asked Perry about this issue and Perry was frank. He affirmed that it was an entrance wound. But beyond that he said he was getting calls through the night from Bethesda. They wanted him to change his story. He said that the autopsy doctors questioned his judgment about this and they also threatened to call him before a medical board to take away his license. (See further “The Ordeal of Malcolm Perry”) To put It mildly, I disagree with Thompson’s next day thesis on this point.

Another surprising aspect of this chapter is that Thompson agrees with the Ramsey Clark Panel. That panel’s findings were released on the eve of the Clay Shaw trial. They upheld the original autopsy’s conclusions about two shots from behind; but they made about four major changes that were rather bracing. One of them was that they raised the entrance wound in the rear of Kennedy’s skull 10 mm upward, into the cowlick area. (Thompson, p. 248)

The way Thompson mentions this in passing was, again, jarring to the reviewer, one reason being that, in all likelihood, it was Six Seconds in Dallas which caused both the Clark Panel to be formed and the rear skull wound to be raised to the cowlick area. (DiEugenio, The JFK Assassination, p. 150). As Russell Fisher, the panel’s chief pathologist later said, Attorney General Ramsey Clark got hold of an advance copy of Six Seconds in Dallas. On page 111 of that book, Thompson shows that Kennedy’s head––as depicted in the Warren Commission to illustrate the fatal wound––is not in the correct posture as shown in Zapruder frame 312. The Commission had the film; therefore, all the indications are that they fibbed about this key point.

How did the Clark panel elevate that wound into the cowlick area? Since Thompson does not show the anterior/posterior X-ray, the reader is in the dark about this point. The answer is they largely based it on a disk-shaped white object in the rear of the skull that stands out plain as day on the X-ray. The problem with this piece of evidence is that none of the autopsy doctors, or the two FBI agents in attendance, saw it on the X-rays in the morgue the night of the autopsy; and it is not in the 1963 autopsy report. All of which is incredible, for two reasons. First, it is by far the largest fragment visible; and second, its dimensions of 6.5 mm precisely fit the caliber of ammunition Oswald was allegedly firing. (DiEugenio, The JFK Assassination, pp. 153-54)

I could go on from there, but I won’t. As the reader can see, I did not find this chapter at all satisfactory.

IV

One of the key points Thompson wants to make in this book is something he has been talking about for a rather long time. It is the work of Dave Wimp on what the author calls “the blur illusion.” In fact, Thompson calls Chapter 14, “Breaking the Impasse: The Blur Illusion.” Since I took Thompson at his word about this, several years ago, at a JFK Lancer conference, I mentioned Wimp and his work. I said the forward bob by Kennedy preceding the rearward head snap did not really exist. Almost immediately after I finished my address, first Art Snyder and then John Costella disagreed with me. Snyder disagreed with me on the mathematical analysis Wimp had done. Costella disagreed on whether or not this was really an illusion. In other words: did Kennedy’s head really bob forward before jetting backward? The two disagreements gave me pause. Why? Because both men are physicists.

Back in the sixties, Thompson first learned of this forward bob between Zapruder frames 312-313 from one of the earliest students of the film, Ray Marcus. (See page 112 of Six Seconds in Dallas, footnote 2) The author and Vince Salandria then studied this in combination with the more dramatic and lengthier rearward slam at the Archives. (Six Seconds, pp. 86-87) The issue is one of the most interesting aspects of Thompson’s first book. He goes through a few explanations of how this could have occurred. He then decides on a term that became rather famous in the critical community––the “double hit” or “double impact.” (pp. 94-95) In other words, two projectiles hit Kennedy’s skull almost instantaneously: one from behind and one from the front. The first moved him forward, the second rocked him backward. He then adds that S. M. Holland had told him the third and fourth shots sounded like they were fired almost simultaneously. He backs this up with other witnesses who heard the same thing. Thus the double impact was credible.

Why did Thompson change his tune on this point? There seem to be three reasons for this. The first is that he felt his first thesis allowed for too precise a synchronization of the shots. No firing team could be that well trained. The second and third are complementary: Dave Wimp’s work coincided with his gravitation towards the acoustics evidence.

Since Thompson decided to go with the acoustics, he had to dump the “double hit” he wrote about in his earlier book, because the acoustics evidence allows for only one shot from the front at Zapruder frame 312. The following shot comes from behind at Zapruder frame 328. Dave Wimp aided this new scenario by somehow making the forward bob disappear, being dismissed as an illusion.

But if such was the case, then why did the two physicists disagree with my statement about the Wimp thesis? Snyder objected to it on mathematical grounds. He did not think that Wimp’s work had absolutely proved his thesis. He told me that there was about a 20% chance Wimp was wrong. Snyder turned out to be correct, because in a reply to Nick Nalli’s review of Last Second in Dallas, Wimp admitted his calculations were not correct. He wrote:

That I have a blur illusion hypothesis is the result mostly of people failing to distinguish between what people are saying and what people are saying people are saying, which seems to be a pervasive problem. The issue is not about illusions but rather about bad methodology.

Today, Wimp now seems to admit that Kennedy’s head did go forward by about an inch. Evidently, Thompson oversold this idea to at least one person: me. And since he still insists on it in his book, perhaps others.

Costella explained why Wimp made an error in a more practical, applicable sense:

Wimp has always made a valid observation about trying to measure the position of a single (rising or falling) edge, in the presence of blur. That is fraught, especially in the presence of unavoidable nonlinearities. What he never seems to have considered, as far as I can tell, is that if you have two opposite edges (rising then falling, or vice versa) of an object, then it is quite simple to align the center of mass of the object between any two frames, even if the edges are blurred. You can do this even if the two frames are blurred differently––that’s effectively what all stabilized versions of the film do (including his own!). It’s even simpler if you either deblur the blurred 313 to match 312 (like I did back in the day, per my animation on my website), or else blur 312 to match 313 …. What I never did is put an exact number of inches on the forward head movement. I have no idea if his smaller number is accurate or not, because I didn’t quantify. What is certain, just from the visuals, is that the head moves forward in the extant Z film. (Email of 6/15/21)

How proficient is Costella in his study of the film? After he approached me at JFK Lancer, he took out his cell phone and showed me how he had deblurred Zapruder and the forward head bob was still there. Yes, John is a man who carries his work with him.

G. Paul Chambers, another physicist, probably has the most sensible explanation for this aspect of the case. He has told Gary Aguilar that what likely happened is that the first shot through Kennedy’s back likely paralyzed him. When the car began to brake, his limp body then went forward. (Phone call with Gary Aguilar, 7/18/21)

V

“Jim, there is no motorcycle where the HSCA says there is.”

The above quotation is taken from a phone conversation in 1994 between this reviewer and the late Dick Sprague. I chose to lead this part of my review with it because, as with the head bob, I once believed in the acoustics evidence. So when the famous photo analyst Dick Sprague said the above to me, I was surprised.

Let me explain why I had that reaction. When I visited the now deceased HSCA attorney Al Lewis at his office in Lancaster Pennsylvania, he told me about something his former boss had done in the early days of that congressional committee. Chief Counsel Richard A. Sprague had arranged a day-long study of the photographic evidence in the JFK case. There were three presenters on hand: Bob Cutler, Robert Groden, and Dick Sprague. They went in that order. Before Cutler began, the chief counsel turned to those in attendance and said, “I don’t want anyone to leave unless I leave, and I don’t plan on leaving.” As Lewis related to me, Cutler’s presentation was about 35 minutes. Groden’s was over 90 minutes, close to two hours. Dick Sprague’s went on for four hours. By the end of Sprague’s demonstration, 12 of the 13 staff lawyers believed Kennedy had been killed by a conspiracy. (James DiEugenio and Lisa Pease, The Assassinations, p. 57)

Such was the photographic mastery of Dick Sprague. At that time, no one had a more expansive collection of films and photos than he did. In that phone call, he told me that Robert Blakey, the second chief counsel, only called him once. It was to ask him if there was a motorcycle where the acoustics experts said there had to be one. Dick spent a lot of time going through his massive collection. He eventually replied that no, there was not. It was Groden who said that there was.

To this day this issue has not been settled to any adequate degree. And there is simply no papering it over. Because the motorcycle has to be at a precise point near the intersection of Houston and Elm for the acoustics evidence to be genuine. Modern experts on the motorcade, like Mark Tyler, insist that Sprague was correct. And Mark argues that point effectively at the Education Forum. (See his post of June 9th) What I found severely disappointing about Thompson’s book is this: he barely deals with the issue at all. This is what he says about the highly controversial but crucial point: he writes that he and author Don Thomas found the correct motorcycle in the films of Gary Mack. Afterwards, they had a few beers and called it a night. (p. 304)

I could hardly believe what I was reading. I actually wrote “WTF” in the margin of my notes. Somehow, this trio, not experts on the photo evidence, easily accomplished something that Dick Sprague––who was the leading authority in the field––could not do? The cavalier way Thompson deals with this important point––throwing in the phrase “having a few beers and calling it a night”––underscores just how unconvincing his treatment of it is. If it was this easy to locate and demonstrate, then why is there no picture of the proper motorcycle in proper context to accompany the “few beers and calling it a night”––straight out of Sam and Diane at Cheers––motif? I was so puzzled by this carelessness, leaning toward avoidance, that I went back and read up on the acoustics evidence.

These sound recordings first entered the legal case during the days of the HSCA. They were offered up by Texas researchers Gary Mack and Mary Ferrell. Thompson does a good job in explaining the rather primitive technology which the Dallas police used in these recordings. There were two channels being recorded that day, simply labeled Channel 1 and Channel 2. The latter used a Gray Audograph powered by a worm gear which drives a needle into a vinyl disk. (Thompson, pp. 304-06). Channel 1 “was done by a Dictaphone that used a stylus inscribing a groove onto a blue plastic belt called a Dictabelt mounted on a rotating cylinder.” (Thompson, p. 148). Channel 1 was used for basic police operations. Channel 2 was for special events, like Kennedy’s motorcade. Back at headquarters, the dispatcher would announce each minute that passed, and each time the dispatcher spoke to a unit he would announce the time. (p. 149)

The HSCA did two tests of the acoustics. The first was by a company called Bolt, Beranek, and Newman. The main scientist on this was James Barger, who supervised a reconstruction test in Dealey Plaza. After doing this, Barger said that there was about a 50% chance of a shot from the Grassy Knoll. The HSCA then gave those results to another team of acoustic experts: Mark Weiss and Ernest Aschkenasy . After examining this data they decided there was a much higher probability, 95%. The HSCA announced this in their final days.

Because he is wedded to this evidence for the finale of his book, Thompson has nothing but scorn for what is today called the Ramsey Panel. The Department of Justice asked the National Academy of Sciences to review the work of the HSCA. They set up a committee named after Harvard physicist Norman Ramsey. Alvarez ended up serving on this committee. Alvarez told Barger that no matter what he said he would vote against him. (Thompson, p. 287) The panel was biased from the start and the author does a good job proving that point. For Thompson, this is why they ended up rejecting the HSCA result.

But I want to note two things about the closing 80 or so pages of Last Second in Dallas and how an author making himself a character in his book is a double-edged sword. Thompson mentions a 2013 debate he did for CNN moderated by Erin Burnett; his opponent was Nick Ragone. (p. 276) If one can comprehend it, Ragone brought up Gerald Posner’s discredited book Case Closed. Thompson says he did not do well since he did not have any new evidence to reply with. I don’t want to toot my own horn, but if I had been there, I would have had a lot of new evidence to throw back. This is how I would have replied:

Nick, that book came out in 1993. Which was one year before the ARRB was set up. They declassified 2 million pages of documents. Have you read them? I read a lot of them, and here is what they said.

When asked the old chestnut, “Well why didn’t someone squeal?”, Thompson could have mentioned Larry Hancock’s book Someone Would Have Talked. He then could have said: “Larry shows that two people did talk, Richard Case Nagell and John Martino. If you don’t know about them, that is a failure of the MSM.” As a point of comparison, when Oliver Stone and I did an interview this past June with Fox, I brought about eight of these new ARRB documents with me. Fox filmed me showing them while I described what they said. They then had me send them in email form. Whether or not they will exhibit them on the show, I don’t know. But I had enough rocks in hand to play David with his slingshot.

VI

But the reason I think Thompson plays up the CNN experience is that he wants to show that if the acoustics evidence had been reexamined, he could have mentioned that. As noted, Thompson harshly critiques the Ramsey Panel, and much of this is warranted. But he only briefly mentions how the Weiss/Aschkenasy ––hereafter called WA––verdict was rather hastily granted a stamp of approval by the HSCA.

What makes this kind of odd is that the author mentions Michael O’Dell more than once in the book. But he does not go into O’Dell’s rather bracing criticism of WA. O’Dell is a computer scientist and systems analyst. O’Dell wrote that the WA conclusion was based upon a motorcycle rider having his Channel 1 microphone button stuck open for a continuous five minute period. This was thought to be H. B. McLain, who first said it was and then said it was not him. What O’Dell was trying to do was to replicate what WA had done, except with much more powerful computer tools, not available back then. He wrote a report called “Replication of the HSCA Weiss and Aschkenasy Acoustic Analysis.” In his report, he found that:

Numerous errors have been found with the data provided in the report, including basic errors involved in the measurement of delay times, waveform peaks and object position. Some of the errors are necessary to the finding of an echo correlation to the suspect Dictabelt pattern. The Weiss and Aschkenasy report does not stand up to even limited scrutiny, and the results it contains cannot be reproduced. (p. 2)

O’Dell revealed that WA had relied on a millimeter ruler and string to map out their bullet paths on a map of Dealey Plaza. O’Dell used Adobe Photoshop to scan the same map as WA and transferred the measurements into pixels after lining them up in Excel. He found multiple critical errors in WA’s work, including those of distance measurement of buildings from other objects like the stockade fence. (See p. 3) O’Dell wrote that the microphone was positioned in the wrong place by WA. (p. 9) There were errors in the original paperwork independent of a transfer to a virtual model. For the buildings list in Dealey Plaza, items 16 and 20 were described as the same object. (p. 4) He also found out that one of the bullet paths was supposed to rebound off of object 23, yet there were only 22 structures WA had listed. (p. 5). There were objects listed in the WA table that O’Dell could not find on the map. (p. 8) But perhaps the most bracing criticism O’Dell made was that

… the values presented in Table 4 for the Dictabelt pattern do not appear to be valid measurements of the peaks in the recording. A test that supposedly identifies a gunshot on the Dictabelt recording must, at a minimum, correctly measure the sound being tested on the Dictabelt. (p. 11)

I could go on. But before anyone comes back at me by saying, “Why would you use something like this after what Dale Myers did with his phony cartoon based on the Zapruder film?” After all, Jim, Myers went on ABC TV and said the single bullet theory was really the single bullet fact. All I can do is reply with the following. I used O’Dell because Thompson used him. In communicating with the man I found out that Thompson had signed him to a non-disclosure agreement about his book. It ended when the work was published.

Another series of problems with this evidence was written about by Charles Olsen and Lee Ann Maryeski in June of 2014 for Sonalysts, Inc. out of Waterford, Connecticut. They stated that although McLain had claimed he had opened up his cycle to a continuous high speed after the shooting, that is not what they determined by placing the sound on a graph: “What Figure 1 shows is a motorcycle that variously speeds up and slows down and idles during this latter period.” (6/6/2014, Olsen and Maryeski, pp. 3-4)

Let me add one other comment. As both O’Dell, and especially Dave Mantik have pointed out, one of the virtues attributed to this evidence is the so called “order in the data.” Or as Don Thomas puts it in his book, the best test matches correspond to a topographic order in Dealey Plaza and with the dictabelt. (Hear No Evil, p. 583) But as Mantik informed me, if one looks at Thompson’s own table, if the HSCA had chosen the bullet sound at the 144.90 point in the tape, they would have had two matches to the School Book Depository that very closely matched the one to the knoll area. (Thompson, p. 155) The same thing occurred at 137.70; the TSBD could have been chosen over the knoll. (interview with Mantik, 6/26/21)

In addition to all the above, Thompson essentially brushes over the issue of heterodyne tones. (p. 296) This is an important point that the Sonalyst report examined. It’s important because it can result in words being scrambled in pronunciation as one listens to them. Meaning that they can sound like one phrase to one person and another phrase to someone else. And this has happened. (Olsen and Maryeski, p. 9)

Even his heralded discovery, that voices saying “Hold everything” and “I’ll check it,” occur around the assassination is odd. First, the object is to show whether or not the bullet echo correlation is real, not the voices. Also, to get a more distinct peak for “I’ll check it,” Richard Mullen, Barger’s protégé, used a narrower sampling PCC (Pattern cross correlation) window of 64. Therefore Thompson concludes this is what should have been used from the start. Yet for “Hold everything,” a wider sampling window of 512 yielded a larger net peak than did a smaller sampling window of 64. Thompson offers no explanation for this seeming paradox. (See Figures 22-6 and 22-7; 6/26/21 interview with Mantik)

If the “Hold everything secure” phrase is at the time of the assassination, then the acoustics is invalid, since this is spoken after the assassination. “I’ll check it” would be around the time of the shots. So the two phrases are in conflict if both were valid. The first phrase is at the wrong time, the latter one is at the right time. So Thompson argues that the “Hold” phrase has been altered and is really an overdub. (Thompson, pp. 345-47)

This has also been placed in doubt by O’Dell. (See Dictabelt Hums and the “hold everything secure” Crosstalk) The “Check” phrase, as has been argued by many, is not really crosstalk at all. The same sound does not appear on both channels. (Email communication with O’Dell, 7/25/21). And further, Sonalysts showed that the spectrograms of the phrase differ on Channel 1 and 2. (Olsen and Maryeski, p. 6)

I could go on. But I think the point has been made. There are simply too many uncertain variables with the acoustics evidence to rely on it as having a 95% probability. Much of this is due to the innate poor quality of the recordings themselves.

When we were making JFK Revisited, producer Rob Wilson asked me to incorporate a section on the acoustics evidence. I recommended against it. I simply noted that with all the above problems with that evidence we would be making ourselves into a bull’s eye on a target range; a whole gallery of persons would take out their bows and arrows and start unloading their quivers on us.

As I said in Part 1, there are good things in Last Second in Dallas. And as a responsible critic I have described them. In my opinion, they are important and valuable and have stood the test of time. But it is also my opinion that there are a lot of things which seem to me to be liabilities, including what the author thinks is the culminating arc of his book––and I have described those deficits also. This is why Last Second in Dallas is a decidedly mixed bag.