see Part 1

Larry Sturdivan Bamboozled Neurosurgery, a Legitimate Peer-Reviewed Journal

In November 2003, the journal Neurosurgery published the first of what it promised would be three papers. It was entitled “The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy: A Neuroforensic Analysis—Part 1: A Neurosurgeon’s Previously Undocumented Eyewitness Account of the Events of November 22, 1963.’’ Except for the fourth of the four coauthors, Parkland witness Robert Grossman, MD, none were known to have particular knowledge of the JFK case. The paper’s stated purpose was to showcase Dr. Grossman’s “previously undocumented neurosurgeon’s eyewitness account of what occurred in Trauma Room 1 of Parkland Memorial Hospital on November 22, 1963, in an attempt to shed light on the nature of President Kennedy’s wounds.”[1]

That claim fell wide of the mark. Grossman’s recollections in Neurosurgery were not “previously undocumented.” In 1981, The Boston Globe published Grossman’s account of what he saw in Trauma Room One.[2] He had also “documented” JFK’s wounds to the Assassinations Records Review Board in 1997. In fact, in 2003 Neurosurgery published virtually the same “JFK” skull diagram that Grossman had prepared for the Assassinations Records Review Board (ARRB) six years before.[3] (Fig. 8)

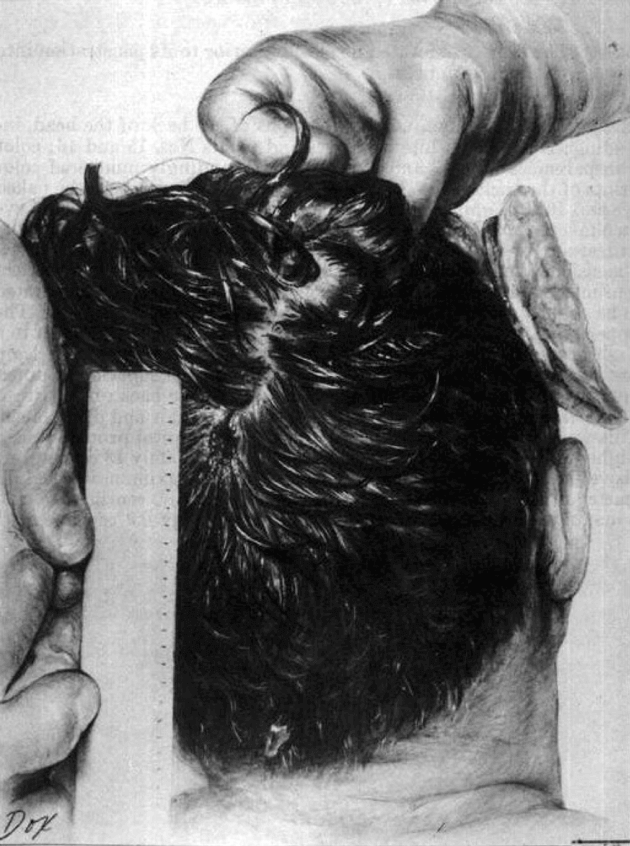

By word and sketch, Grossman recounted that JFK had two skull wounds. The first was a round, 1 inch defect—to the right and ~1 inch above the external occipital protuberance, entirely within the occipital bone. (Fig. 6) The second was on the side of “JFK’s” skull, no larger than about 3 inches, or ~7 & 1/2 cm, and confined solely to parietal bone. Grossman saw no contiguity between the occipital defect and the defect in the right parietal bone that he depicted.

Neither Grossman’s description nor his images square with what are said to be the authentic photographs taken of the back of JFK’s head at autopsy. Nor are they consistent with the findings in the official autopsy report, or even the sketch diagram of Kennedy’s skull wound that was prepared on the night of the autopsy by one of the autopists. The photographs show no defect low in the back of Kennedy’s head (Fig. 9), and an image prepared on the night of JFK’s autopsy documented a much larger skull defect than 3 inches. (Fig. 10)

The official autopsy report specified that JFK’s skull defect measured 13 cm, fore to aft.[6] That was later corrected by autopsist, J. Thornton Boswell. He twice testified that when first examined, it actually measured 17 cm, which was the size that he documented on the “face sheet” diagram he prepared by hand during Kennedy’s autopsy. (Fig. 10)[7] After they replaced loose skull fragments into JFK’s skull wound, Boswell explained, the defect then measured 13 cm, and that was the dimension they put in the autopsy report.

Besides his claims about JFK’s skull wounds, Part 1 was also noteworthy for Grossman’s reporting that Parkland’s chief of neurosurgery, Kemp Clark, MD, “and I lifted (JFK’s) head to inspect the occiput,” where he saw “a laceration approximately 1 inch in diameter located close to the midline of the cranium, approximately 1 inch above the external occipital protuberance. Brain tissue, some of which I thought had the appearance of cerebellar folia, was lying in the laceration.”

The importance of those remarks is not the nature of JFK’s injuries, which are demonstrably inaccurate, but that two neurosurgeons quite appropriately lifted JFK’s head and took a good look at Kennedy’s skull injuries. Like 7 other Parkland doctors, including Dr. Clark, Grossman said he saw a rearward wound—in the occiput. And he saw cerebellum, the small lobe of the brain at the rear-bottom of the brain case, under the occipital bone and beneath the large cerebral lobes of the brain. (That so many credible Parkland witnesses were in agreement on this is old news, but still important as the autopsy photos show there was no rearward skull wound and no cerebellar damage.[8]) Things got much more interesting in Part 2.

In June 2004 Neurosurgery published Part II, entitled, “A Neuroforensic Analysis of the wounds of President John F. Kennedy: Part 2 – A Study of the Available Evidence, Eyewitness Correlations, Analysis and Conclusions.” The lead author was University of California Professor of Neurosurgery, Michael Levy, MD, Ph.D. As in Part I, the fourth coauthor was Robert Grossman, MD.[9]

We were stunned by the long-discredited nonsense that was in it. As the Assassinations Archives and Research Center (AARC) was hosting a JFK conference in Washington, D.C. that fall, one of the current authors (GA) proposed inviting Professor Levy to give a presentation. He agreed and delivered a well-prepared Powerpoint talk. Author Aguilar then stood up and gave a point-by-point rebuttal. Professor Levy was dumbfounded. That evening, Levy joined authors Wecht and Aguilar, and Roger Feinman JD, for dinner. He expressed an honest shame and embarrassment that he knew nothing of the counterfactual evidence Aguilar had presented.

As professor Levy was unknown in the JFK universe, we asked him where he got his information. He said that he based his paper and presentation on material that Dr. Grossman suggested he read. He encouraged us to submit a rejoinder to Neurosurgery to correct the factual record. We did and, apparently over the objections of Dr. Grossman, they published our 10,000 word rebuttal on September 2005.[10]

As we worked on our reply, we noticed that the last page of Levy’s paper included a short congratulatory letter from Larry Sturdivan. “Part 2 of this article,” he wrote, “does not present important new evidence regarding the President’s wounds, as Part 1 did. [Which was false, as we’ve shown from the Boston Globe and the ARRB documents re Part 1, above.] Nevertheless, it is an important summary of the material previously reported. The report, especially the full version on the web site, not only saves the reader the time of acquiring these myriad sources, but also puts them into perspective in a way that a simple collection of documents cannot.”[11]

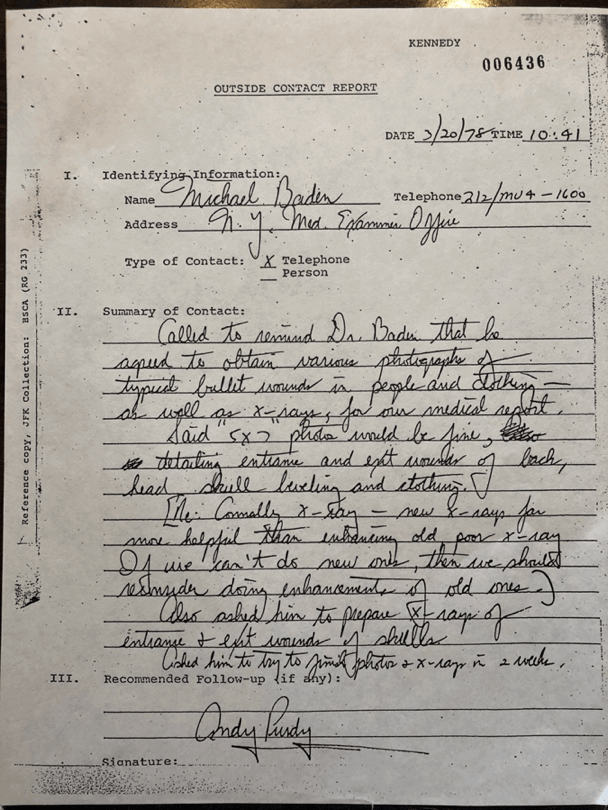

Intrigued, one of us (GA) phoned the editors at Neurosurgery who were working with us on our reply. He asked them how they found the “peer” who’d reviewed Levy’s paper. They said they didn’t know who to ask. So they turned to Levy’s coauthor, Robert Grossman, the man who had driven the series of articles from the outset. He suggested they invite Larry Sturdivan to do the review.

“Did you know that Grossman and Sturdivan have collaborated on JFK?” Aguilar asked. A quick on-line search confirmed that fact. “It’s highly irregular,” Aguilar said, “to have an author’s collaborator review his submission.” “Yes,” he replied, “it is highly irregular.”

Following up via email, Aguilar wrote both the editors and Larry Sturdivan, and still has the emails. They openly admitted Sturdivan had “refereed” both Part I and Part II. Regarding Part II, Sturdivan emailed Aguilar and the editors of Neurosurgery the following:

Dear Dr. Sullivan,

As you suggested in your letter, the article was a quick read. I could find no substantive errors or typos. The following minor details should be examined before publication … . (emphasis added; copy available by request)

No substantive errors?

Given our rejoinder ran to roughly 10,000 words, with 94 footnotes, a comprehensive accounting of the “substantive errors” Sturdivan missed in Part II alone is well beyond the scope of this discussion. But it can be viewed on-line at Neurosurgery’s website.[12] However, a few of the errors we identified are worth touching upon.

- Levy recycled debunked claims that the fibers in the back of JFK’s coat were bent inward and the fibers in his shirt front were bent outward, thus proving the back-to-front direction of the bullet. As we documented, it was FBI director J. Edgar Hoover who fabricated those claims and it was the FBI Lab itself that disavowed them.

- Levy repeated one of the Warren Commission’s most discredited myths, namely, that a Warren Commission ballistics expert had successfully duplicated JFK’s injuries in simulation shooting tests with cadaver skulls. “That (test) bullet,” Levy wrote, “blew out the right side of the reconstructed cranium in a manner very similar to the head wounds of the President.” Except for the word “cranium” rather than “skull,” as was originally written, this sentence is torn verbatim from page 585 of the Warren Report, given without the appropriate quotation marks or attribution.[13] As we’ve shown here, we noted in our reply that the blasted test skull was not at all “very similar” to JFK’s. It sustained severe damage to the right forehead, the loss of the right orbit, and much of the cheek bone, injuries JFK did not sustain.

- Dr. Levy accepted the legitimacy of Kennedy’s autopsy photos as well as Grossman’s claim that there was a one-inch hole in the occiput of JFK’s skull. He ignored the fact that the supposedly authentic autopsy photos show no occipital wound, one that was described not only by Grossman, but also by numerous Parkland physicians including the chief of neurosurgery, Kemp Clark MD. He also ignored that JFK’s autopsy surgeons all testified that photos they took on the night of the autopsy are missing.

- Ironically, Levy never mentioned, and likely didn’t know, that the ARRB’s chief Analyst for Military Records, Douglas Horne, showed Grossman the Ida Dox sketch of the back of JFK’s head taken from the autopsy photographs (Fig. 8).[14] Grossman rejected it. Horne reported that, “Grossman immediately opined, ‘that’s completely incorrect.’ He insisted there had been a hole devoid of bone and scalp about 2 cm in diameter near the center of the occipital bone.”[15]

- Dr. Levy cited the HSCA’s claim it had authenticated Kennedy’s autopsy photos. But he failed to notice a telling footnote in the very HSCA pages he cited in support of authentication. The HSCA wrote that, “Because the Department of Defense was unable to locate the camera and lens that were used to take these [autopsy] photographs, the [photographic] panel was unable to engage in an analysis similar to the one undertaken with the Oswald backyard pictures that was designed to determine whether a particular camera in issue had been used to take the photographs that were the subject of inquiry.”

But that’s not what the Navy had said. Since Kennedy’s autopsy was performed at the Navy’s Bethesda Hospital, the Secretary of the Navy responded to the HSCA’s claim they hadn’t been given the camera that had taken JFK’s autopsy images . The Secretary huffily insisted that the Navy had definitely sent the HSCA the actual camera, the very one the HSCA’s experts had determined had not taken them.[17]

Whereas the HSCA reported it could not completely close the loop because the camera was missing, the suppressed record suggests that 1) the loop was closed, 2) the camera was located, and 3) that the HSCA’s own authorities determined that the camera “could not have been used to take [JFK’s] autopsy pictures.” The HSCA staff elected to withhold this inconvenient information from the public. They also kept it from their own experts on the Forensic Pathology Panel, including the chairman, Dr. Michael Baden (personal communication), and one of the authors of this essay [CHW]. And so, as per Dr. Levy, the HSCA experts, and Neurosurgery readers were left to labor under the illusion that the images had passed authentication with flying colors.

Thereafter, the editors worked with us and published our lengthy reply. Our evisceration of Dr. Grossman’s JFK project scuttled the rest of the planned operation. Neurosurgery never published the promised Part III of “A Neuroforensic Analysis of the Wounds of President John F. Kennedy.”

The point of this extended discussion is to note that long-debunked anticonspiracy claims of “jet effect,” “neuromuscular reaction,” Neutron Activation Analysis, the government’s skull shooting tests, JFK’s authenticated autopsy photographs, the magic bullet, etc., continue to be recycled by fact-averse, anticonspiracy evangelists. Nicholas Nalli is the new crusader. He laughably tried to rehabilitate “jet effect” and “neuromuscular reaction.” He gave Sturdivan and Haag the benefit of the doubt on their repeatedly debunked NAA fantasies. And he did it in a “peer reviewed,” “scientific” article which was clearly reviewed not by anonymous, informed scientists, as Nalli claimed, but instead by ill-informed Warren loyalists, including in all likelihood, Larry Sturdivan.

Suspicion falls to Sturdivan because Nalli gushingly acknowledges him (“first and foremost”) for reviewing drafts of his paper and for “providing expert feedback.” Just as Sturdivan had thrown eggs on the faces of Professor Levy and the editors of Neurosurgery by “peer-approving” so much nonsense, he did so again to Nicholas Nally by likely contributing to, and possibly “peer-reviewing,” some rubbish that should embarrass Nalli, and expose Heliyon as an outlet for authors who are unwilling to run their work through a proper, expert, anonymous “peer review” gauntlet.

Lost in the fog of his attempt to give mouth-to-mouth to the government’s gasping scenario are the multiple lines of evidence Nalli ignores that converge on the conclusion anyone seeing the Zapruder film immediately draws: the mortal head shot at frame 313 came from the right front. For that reason, that’s a good place to start.

What Can Science Tell Us About What Happened in Dealey Plaza?

The Zapruder film, jiggle analysis, and the death of JFK

As mentioned, in 1976 Alvarez theorized that some of the Zapruder frames are blurred at points that appear to correspond to Mr. Zapruder jerking his camera in startle-reaction to the sound of gunfire.[18],[19] His theory was later validated by CBS after it ran its own, independent experiment.[20] The HSCA also undertook its own “jiggle analysis.” On page 20 and 24 of the HSCA’s report, two independent consultants produced graphs depicting the frames in which there was blurring.[21] For the shot that allegedly flipped Governor Connally’s lapel at Zapruder frame 224, the HSCA graphs show a corresponding “jiggling” three frames later, at 227.[22] The delay is due to the fact the sound wave reached Zapruder after the speedier bullet hit its target. There are other frames that are much more “jiggled” than frame 227 is.

One is Zapruder 313, the head shot. As discussed, if Oswald had fired that shot, frames 316–17 would be blurred.[23] They’re not; they’re sharp. There is only one mathematical possibility for a bullet shock wave distorting the camera’s gaze at frame 313: the bullet had to have been fired much closer to Zapruder than from Oswald’s alleged perch, 270 feet away. The best scenario is that it came from where Mr. Zapruder had told a Secret Service Agent on 11/22/63 it had come from, behind him, from the grassy knoll, approximately 60 feet behind the cameraman.[24],[25]

Let’s assume the shot was fired between frame 312 and 313. Since the shock waves from rifle muzzle blasts travel at the speed of sound, ~1125 ft/sec, the sound and shock wave from a grassy knoll shot would have hit Zapruder in less than 1/20th second, that is, within a single frame of Zapruder’s camera. A good correlation. The sound and shock wave from Oswald’s position, however, would have hit Zapruder 3 to 4 frames later, at, say, 316 or 317.

There is also considerable blurring of frames 331 and 332.[26] This appears to match a putative shot from behind that struck JFK’s head in frames 327–328 as per Last Second in Dallas, one which drove him forward more rapidly than he moved rearward after frame 313, as we’ve discussed.

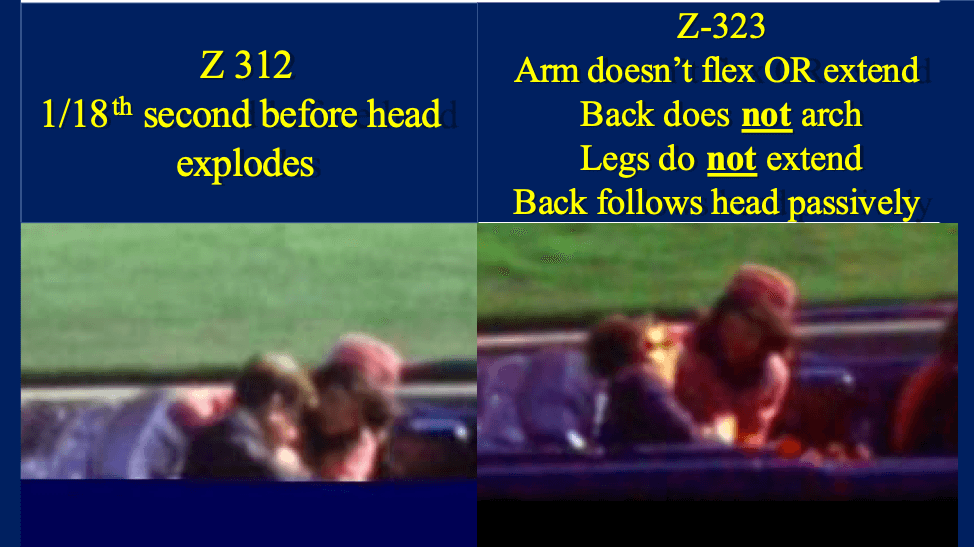

But what about Kennedy’s rearward lunge after frame 313? If not “jet effect” or “neuromuscular reaction,” what caused it?

Did Momentum Transfer from a Grassy Knoll Shot Drive JFK “Back and to the Left?”

To answer this question, we return to the most analogous, and credible, experimental evidence: the government’s 1964, Biophysics Lab, skull shooting experiments. As Larry Sturdivan testified, while demonstrating with film during his HSCA testimony, “All 10 of the skulls that we shot did essentially the same thing. They gained a little bit of momentum consistent with one or a little better foot-per-second velocity that would have been imparted by the bullet…”[27] (As discussed, in his book Sturdivan reported a higher, and more likely valid, velocity: “the skull…moves forward at approximately 3 feet/sec, just as it must from the momentum deposited by the bullet.”[28])

Sturdivan thus argued, as he testified, that a shot from behind would have caused “slight movement toward the front, which would very rapidly be damped by the connection of the neck with the body.”[29] In other words, an MCC shell would have moved the skull in the direction of bullet travel. New information informs two key issues here.

Mr. Sturdivan’s conclusion that momentum transfer could not explain JFK’s skull motion was based on experiments using modestly powered Mannlicher Carcano rounds weighing 162 grains (0.023 lbs) that struck their targets from a distance of 90 yards.[30] And he assumed the fatal bullet was jacketed, and so deposited only half of its momentum when it struck Kennedy’s 15-pound skull.[31] These assumptions are unjustifiable and unfairly bias his conclusions toward the lone gunman. (For example, there is no reason to assume a grassy knoll gunman would have used a Mannlicher Carcano and, in fact, the x-ray evidence suggests it wasn’t a Mannlicher Carcano. See below.)

In his book, Hear No Evil, Don Thomas, Ph.D. scrutinized Mr. Sturdivan’s analysis in considerable detail. With permission, we quote Dr. Thomas.

Sturdivan’s calculation, Thomas writes, was:

derived indirectly from his tests shooting human skulls with a Mannlicher-Carcano. The bullet’s velocity at a distance of 90 yards was 1600 feet-per-second according to Sturdivan (in fact, the Army’s data indicated a value closer to 1800 fps) [sic]. Sturdivan then divided this number in half on the supposition (unstated) [sic] that the bullet would deposit only half of its momentum. This supposition was apparently based on his observation that a velocity of something like ‘one-foot-per-second’ was imparted to test skulls when shot with the Carcano.[32] Somehow, Mr. Sturdivan managed to miss the point that the rearward movement might have involved a shot origination from the grassy knoll only 30 yards in front of the target, with consequently less loss of velocity from air resistance, than from a position 90 yards behind the President. It also seemed not to have occurred to Sturdivan that the President might have been shot from the grassy knoll with a different rifle than the modestly powered Mannlicher-Carcano…[33]

“For the purposes of this discussion,” Thomas continues,

let us suppose that the hypothetical killer on the grassy knoll was armed with a .30-.30 rifle…(which) happens to have a muzzle velocity (2200ft/sec) very close to that of the Carcano and fires a 170-grain bullet, slightly larger than the Carcano bullet. At 30 yards, the projectile would have struck at a velocity of approximately 2100 fps…the momentum on impact with the head would be 50 ft-lb/sec. If one postulates a hunting bullet (in accordance with the x-ray evidence) [sic] which is designed to mushroom and deposit its energy at the wound instead of a fully jacketed bullet, we will allow a deposit of 80% of the momentum, leaving a residual velocity for the exiting bullet. This results in a momentum applied to the target of 40 ft-lb/sec; considerably more than Sturdivan’s stingy allowance of 18.4 ft-lb/sec. It is important to realize that, at the time Kennedy was struck with the fatal shot at Z-312-3, he had most likely been paralyzed by the shot through the base of the neck (as Sturdivan admits[34]). Consequently, his head was lolling forward, not supported by the muscles of the neck. This fact tends to minimize the damping effect (that so troubled Mr. Sturdivan) from the absorption of shock by the neck until after the head has snapped back. Assuming a head weight of 12 lbs, the velocity imparted to the head would be approximately 3.3 feet per second…[35] [The same speed of the test skulls that Mr. Sturdivan reported in his book, though in JFK’s case it might have even been faster as most estimates put the weight of a human head at 10-11 lbs.[36]]

From the study of the Zapruder film by Josiah Thompson, the observed rearward velocity for the head was roughly 1.6 feet per second after frame 313.

Thomas concludes, “Even given the uncertainty about the exact weight of the President’s head and the residual velocity of the bullet, the observed movement of the President’s head is well within the range, if anything less, than expected from the momentum imparted by the impact of a rifle bullet.”[37]

In sum, if one corrects for Sturdivan’s faulty assumptions, yet uses his sound logic, the case for momentum transfer becomes compelling. Thus, if Sturdivan is right, as per Aberdeen Proving Grounds, that jacketed, Western Cartridge Company (WCC) shells moved blasted skulls forward at 3 ft/sec, or even 1.2ft/sec, imagine how swiftly one would move if struck with heavier, higher velocity, soft-nosed bullet fired from a much closer location; perhaps enough not only to move JFK’s skull “back and to the left,” but also enough to even nudge his probably paralyzed upper body in the direction of his head.

As Thomas hinted, Kennedy’s x-rays suggest just such a scenario.

X-Ray Evidence for a Shot from the Grassy Knoll

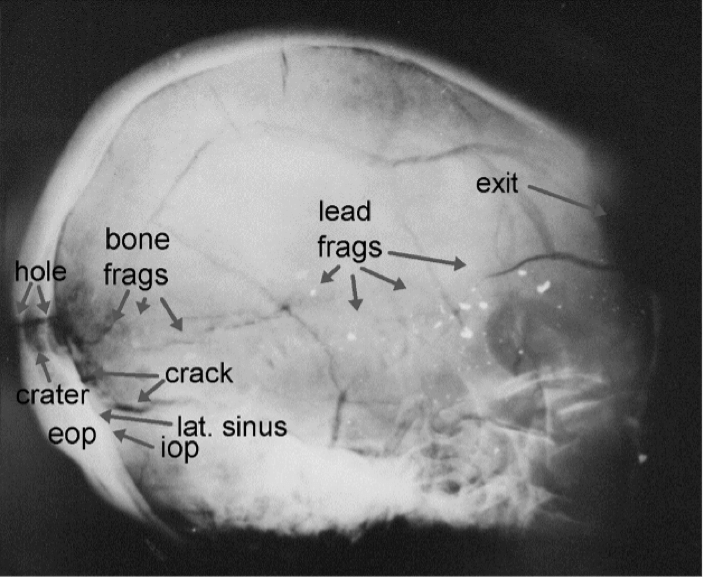

While it is evident that a soft-nosed bullet fired from the right front could have delivered sufficient momentum to drive his head back and to the left, during HSCA testimony it was claimed that JFK’s x-rays prove that he was not hit by a soft-nosed round; that the fatal bullet was jacketed, like Oswald’s. This conclusion is false. It rests on a misreading and misunderstanding of the x-rays. Properly read and understood, Kennedy’s x-rays give evidence for a non-jacketed bullet. The confusion began during late 1970s. That is when the HSCA put an altered version of JFK’s lateral x-ray into evidence and had a non-radiologist, non-physician interpret the altered x-ray—the omnipresent “neuromuscular reaction” “authority,” the Neutron Activation Analysis “expert,” and now the radiology specialist, Larry Sturdivan.

The untrained Sturdivan displayed an “enhanced” version of JFK’s lateral x-ray to the HSCA members (Fig. 10). It was not the original film. The process of enhancement greatly increases the contrast of the x-ray, making the skull bones look much brighter and denser than they appear in the originals. But the process also blots out some of the clinically significant, fine details, including the presence of any miniscule, “dust-like” bullet fragments. Sturdivan testified that the enhanced x-ray ruled out the possibility of a non-jacketed round because, he said, if it had been a non-jacketed shell there would have been many tiny bullet fragments visible on the x-ray.

But, in fact, there are many, tiny fragments on JFK’s skull x-ray. They’re not visible because they’ve been blotted out from view on the enhanced film he presented to the HSCA. The following exchange under oath captured his error.

The Select Committee asked, “Mr. Sturdivan, taking a look at JFK exhibit F–53, which is an x-ray of President Kennedy’s skull,[38] can you give us your opinion as to whether the President may have been hit with an exploding bullet?”

“Well,” he replied, “this adds considerable amount of evidence to the pictures which were not conclusive. In this enhanced x-ray of the skull, the scattering of the fragments throughout the wound tract are characteristic of a deforming bullet. This bullet could either be a jacketed bullet that had deformed on impact or a soft-nosed or hollow-point bullet that was fully jacketed and therefore not losing all of its mass. It is not characteristic of an exploding bullet or frangible bullet, because in either of those cases the fragments would have been much more numerous and much smaller. A very small fragment has very high drag in tissue and, consequently, none of those would have penetrated very far. In those cases, you would definitely have seen a cloud of metallic fragments very near the entrance wound. So this case is typical of a deforming jacketed bullet leaving fragments along its path as it goes.” (emphasis added throughout)[39]

To demonstrate his point in his 2005 book, Sturdivan reproduced on the same page both Kennedy’s enhanced lateral skull x-ray and the unenhanced lateral x-ray of a skull shot with a Carcano round in the Biophysics Lab’s tests in 1964.[40] The pattern of bullet fragmentation was very similar, he said, and he was right. (Figs. 9 and 10)

Re JFK’s enhanced x-ray, he wrote: “…Lead fragments are scattered within the skull, reaching the frontal bone, not clustered at the entry point. Frangible bullets would disintegrate very quickly, producing a dense cloud of fragments at the entry site…the extent of fragmentation of the bullet is characteristic of that of a fully jacketed military bullet that deformed and broke apart upon impact with the skull…It is not that of a frangible, soft-nosed or hollow-point bullet.”[41] (emphasis added)

The unenhanced x-ray of the Biophysics test skull (Fig. 12) shows much the same thing as Kennedy’s enhanced x-ray (Fig. 11), a scattering of small, but not “dust like,” radiolucencies—bullet fragments—across the lower portion of the skull. Neither JFK’s enhanced x-ray nor the unenhanced film of the test skull shot with a Carcano round show the miniscule, more numerous fragments that Sturdivan correctly said would have been present had either been struck with a non-jacketed round.

But Kennedy’s original, unenhanced skull x-rays at the National Archives actually do show a cloud of myriad, tiny radiolucencies. Those tiny fragments, and their location, collapse the case for a lone gunman for the good reasons Sturdivan gave: a non-jacketed bullet leaves numerous, tiny fragments near their point of striking—just like those that are clearly visible in Kennedy’s original, unenhanced x-rays. Jacketed bullets like Oswald’s don’t do that.

Both authors Wecht and Aguilar have examined the still-secret, original, unenhanced x-rays at the National Archives and have seen that “dust like” fragments are present in the right front quadrant of Kennedy’s skull x-rays. We are not the only ones who’ve noticed them. They were reported by Kennedy’s chief pathologist, Dr. James Humes, by a Secret Service agent, as well as other government consulting, expert radiologists. The presence of miniscule fragments essentially rules out that Oswald’s single, jacketed round hit Kennedy at frame 313.

Why?

For the good reasons Sturdivan gave: tiny fragments don’t travel far in tissue, because of their low mass relative to their large surface area, their “high drag” in tissue. Tiny bullet fragments are quickly stopped in tissue. In contrast, larger fragments have proportionately less surface area compared with their mass than small fragments do, and so drive further through tissue before being stopped.

Besides their presence, a telling detail is the location of the tiny fragments. They sit in the right front quadrant of JFK’s skull, which, to borrow from Sturdivan, is likely “very near the entrance wound.” This evidence has largely lain unrecognized and unappreciated in the record since 1964.

- During his Warren Commission testimony in 1964, Dr. Humes said: “(JFK’s x-rays) had disclosed to us multiple minute fragments of radio opaque material…These tiny fragments that were seen dispersed through the substance of the brain in between were, in fact, just that extremely minute, less than 1 mm in size for the most part.” A few moments later, Dr. Humes was asked, “Approximately how many fragments were observed, Dr. Humes, on the x-ray?” “I would have to refer to them again (the x-rays),” he answered, “but I would say between 30 or 40 tiny dust-like particle fragments of radio opaque material, with the exception of this one I previously mentioned, which was seen to be above and very slightly behind the right orbit.”[43]

- Secret Service Agent Roy Kellerman, an autopsy witness, testified that the fragments in JFK’s skull x-ray, “looked like a little mass of stars; there must have been 30, 40 lights where these pieces were so minute that they couldn’t be reached.”[44]

- Russell Morgan, MD, the chairman of the department of radiology at Johns Hopkins University, was the Clark Panel’s radiologist. “Distributed through the right cerebral hemisphere are numerous, small irregular metallic fragments,” the Panel reported, “most of which are less than 1 mm in maximum dimension. The majority of these fragments lie anteriorly and superiorly. None can be visualized on the left side of the brain and none below a horizontal plane through the floor of the anterior fossa of the skull.”[45] (emphasis added)

- Cook County Hospital Forensic Radiologist, John Fitzpatrick, MD, examined JFK’s x-rays in consultation for the ARRB and agreed, writing: “There is a ‘snow trail’ of metallic fragments in the lateral skull X-Rays which probably corresponds to a bullet track through the head, but the direction of the bullet (whether back-to-front or front-to-back) [sic] cannot be determined by anything about the snow trail itself.”[46]

Authors Wecht and Aguilar concur: there are myriad “dust like” fragments visible on JFK’s lateral x-ray, a “snow trail,” if you will. The vast majority are confined to the right front quadrant of Kennedy’s skull, which is where, as per Sturdivan, a non-jacketed bullet struck.

Practicing radiologist Michael Chesser, MD examined the original, unenhanced JFK x-rays and came to the same conclusion. “This location, on the intracranial side of the bony defect, is highly suggestive of an entry wound,” he wrote. “One of the principles of skull ballistics is that the largest fragments travel the furthest from the entry site, with the smallest traveling the least distance, and that is exactly what is seen on this right lateral skull x-ray. Tiny fragments are seen on the inner side of this right frontal skull defect, and the largest fragments were noted in the back of the skull.”[47]

Forensic pathologist Vincent DiMaio, MD elaborated upon the meaning of a “snow trail,” or “snow storm”: “[T]he snowstorm appearance of an x-ray almost always indicates that the individual was shot with a centerfire hunting ammunition…”[48]* That is, a non-jacketed round. And as per Sturdivan, the right-forward location of the tiny fragments is a clear indication of what is visible in Zapruder film: an entrance wound in the right front quadrant of Kennedy’s head for a bullet that left a tell-tail cloud of “dust like” fragments in that area. For, although he thought that the shot at Zapruder frame 313 went from back to front, Sturdivan admitted what is well understood in the “ballistics/forensics” community: “A similar explosion would have taken place if the bullet had gone through in the opposite direction.”[49] In fact, Fig. 2 in Part I of this essay demonstrates this very principle: the human skulls shot in the government’s tests show about as much cranial contents egressing out of the entrance point at the rear of the test skull as out of the front.

(*In a later edition of DiMaio’s book, he allowed that the breach of the shell’s jacket after Oswald’s bullet went through Kennedy’s skull might have released the tiny lead fragments seen in the x-rays. However, he offered no evidence for this claim and the Biophysics skull shooting tests did not show this phenomenon. DiMaio’s is thus an assertion made without evidence and, therefore, will be dismissed in view of the counterevidence from the Biophysics tests.)

Sturdivan finally saw the original, unenhanced images in 2004 at the National Archives. He was emphatic under oath to the HSCA that the absence of tiny fragments in the enhanced x-ray proved that a jacketed bullet, not a hunting round, had struck JFK. But when he wrote his book in 2005, and when he reported on his examination of the originals that dramatically do show the telltale tiny fragments in the right front quadrant of JFK’s skull, he said nothing about them. He either didn’t notice them, or elected not to say he had.[50] “Scientists” like him don’t see what they don’t want to see. The HSCA’s x-ray “expert,” Sturdivan, didn’t see what other, vastly better credentialed, true experts did see.

The trail of small, but not miniscule, fragments that are visible runs along the top of JFK’s skull in both the enhanced and nonenhanced lateral x-rays. It does not align with the supposed low entrance wound specified by the autopsy surgeons in occipital bone, although the autopsy surgeons said it did. Nor does it line up with the higher entrance wound the Clark Panel identified, although the Clark Panel said it did.[51] In fact, as anyone can see the fragment trail in JFK’s lateral x-ray is about 5 cm above where both the Clark Panel and the HSCA said it was. (Fig. 11) That high fragment trail offers evidence there was a second head shot, from behind, with a jacketed round, a possibility that is also suggested by the “jiggle” evidence in the Zapruder film, by Professor Barger’s acoustics analysis, and by JFK’s rapidly forward moving skull after frame 328, as explored by Thompson in Last Second in Dallas.

To recap, there is a cloud of tiny fragments on JFK’s x-ray, which is typical of a hunting round, but not Oswald’s jacketed bullet. That cloud is located in the right front portion of his skull, where they would have been quickly stopped by “tissue drag.” This physical evidence independently buttresses the “jiggle evidence” in the Zapruder film that the shot at 313 came from a location close to the camera, the grassy knoll, precisely where the acoustics evidence said it originated, and not from Oswald’s spot, 270 feet away. It is consistent with evidence that JFK’s split-second lunge “back and to the left” was due to the large momentum that was transferred to Kennedy’s cranium by a non-jacketed bullet that mushroomed on impact, and not due to “jet effect” and/or “neuromuscular reaction.”

These multiple, mutually corroborating lines of evidence point in a direction that seemed obvious to the eye of anyone who watched the Zapruder film on the Geraldo Rivera’s Good Night America show in 1975. It is also what seemed evident 28 years ago to Mr. Masaad Ayoob, a respected gun expert and the former Vice Chairman of the Forensic Evidence Committee of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL):[52]

The explosion of the President’s head as seen in frame 313 of the Zapruder film is simply not characteristic of a full metal-jacket rifle bullet traveling at 2,200 fps or less. It is far more consistent with an explosive wound of entry with a small-bore, hyper-velocity rifle bullet traveling between 3,000 and 4,000 fps, and probably toward the higher end of that scale…An explosive wound of entry occurs when a highly liquid area of the body, such as the brain, is struck by a high velocity round. The tissue swells violently during the microseconds of the bullet’s passing and seeks the line of least resistance. That least resistance is the portal of the entry wound that appeared a microsecond before and the bullet will not bore an exit hole to relieve the pressure for another microsecond or two—perhaps not at all if the bullet fragments inside the brain. If the cataclysmic cranial injury inflicted on Kennedy was indeed an explosive wound of entry, the source of the shot would have had to be forward of the Presidential limousine, to its right, and slightly above…the area of the grassy knoll.[53]

Mr. Ayoob speaks from experience. He notes that the closest commonly used cartridge to a Carcano

…in terms of ballistics is probably the .30/30, which has a .308″ diameter. The Carcano round, about a .263″ diameter. Ask any homicide detective if he’s ever seen a .30/30 round blow a man’s head up at 55 to 60 yards, exploding the calvarium up and away from the body proper. Ask any hunter of deer-size game if he’s ever seen the same thing at that distance. It happens only at very close range with that ballistic technology. The wound we see happening in frame 313 in the Zapruder film—and see the results of most clearly in frame 337—is simply not consistent with this rifle cartridge at that distance in living tissue. It is particularly inconsistent with a round-nose full metal-jacket bullet of the type Oswald had in his rifle.[54] [Note that the head of the goat shot in the government’s tests does not explode as JFK’s did. (Fig. 5)]

Mr. Ayoob does not completely discount the possibility of Oswald’s culpability, but only if the shell “for unexplainable reasons did damage out of all proportion to its ballistic capability as most of us would perceive that to be.”[55]

That takes us back to what author Wecht suspected during his tenure on the Forensics Panel of the House Select Committee: JFK’s “…backward head motion might be explained by a soft-nosed bullet that struck the right side of the President’s head.” Wecht presciently surmised that before these multiple lines of independent, converging evidence had been assembled that confirm what seemed so obvious to him, to Masaad Ayoob, and to anyone viewing the Zapruder film.

In Last Second in Dallas, Thompson quoted Don DeLillo: “[D]id the shot simply come from the front, as every cell in your body tells you it did?” “Don DeLillo is right,” Thompson answered, “When you look at the Zapruder film, every cell in your body tells you the shot at frame 313 came from the right front.”[56] We now know that it’s not only your every cell, but it’s also the science that tells you that. It’s the “Occam’s Razor” solution: the simplest, most complete and compelling explanation of the shot that killed John Kennedy. It’s one that requires no suspension of disbelief; no invocation of tortured, disanalogous neurophysiological phenomena; no misreading of Kennedy’s original autopsy x-rays; and it’s one that honors the many witnesses in Dealey Plaza who said that a shot came from the grassy knoll, not least being the 21 cops who “heard a grassy knoll shot.”[57]

[see also: Milicent Cranor’s Forensics Journal Unintentionally Proves Conspiracy in Cover-Up of JFK Assassination and John Lattimer Never Quit: The Thorburn Business]

[1] Daniel Sullivan, M.Div., Rodrick Faccio, B.S., Michael L. Levy, M.D., Ph.D., Robert G. Grossman, M.D., Neurosurgery, Vol. 53, No. 5, November 2003, p. 1020. Available here.

[2] Ben Bradlee. “Dispute on JFK Assassination.” Boston Globe, 6/21/81, p. A–23. Available here.

[3] ARRB MD file # 185. Available here. (see pp. 4 and 5)

[4] Sullivan, Dan. “The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy: A Neuroforensic Analysis—Part 1:

A Neurosurgeon’s Previously Undocumented Eyewitness Account of the Events of November 22, 1963,” Neurosurgery, Vol. 53, No. 5, November 2003, p. 1024. Available here.

[5] MD 185 – ARRB Meeting Report Summarizing 3/21/97 In-Person Interview of Dr. Robert Grossman. Available here.

[6] Warren Commission JFK autopsy report, p. 3. Available here.

[7] ARRB testimony of J. Thornton Boswell, pp. 71–72. Available here.

HSCA testimony of J. Thornton Boswell. HSCA Vol.7, p. 253. Available here.

[8] See Aguilar G, Cunningham K. “How Five Investigations into JFK’s Medical/Autopsy Evidence Got It Wrong, Part V. The ‘Last’ Investigation—The House Select Committee on Assassinations.” Available here.

[9] Levy M, Sullivan D, Faccio R, Grossman R. “A Neuroforensic Analysis of the Wounds of President John F. Kennedy: Part 2—A Study of the Available Evidence, Eyewitness Correlations, Analysis, and Conclusions,” Neurosurgery. Vol. 54, No. 6, June 2004, E1–E23. Available here.

[10] Aguilar G, Wecht C, Bradford R. Neurosurgery. Vol. 57, No. 3, September 2005.

[11] Levy M, Sullivan D, Faccio R, Grossman R. “A Neuroforensic Analysis of the Wounds of President John F. Kennedy: Part 2—A Study of the Available Evidence, Eyewitness Correlations, Analysis, and Conclusions,” Neurosurgery. Vol. 54, No. 6, June 2004, E23. Available here.

[12] Aguilar G, Wecht HC, Bradford R. Reply to: “A Neuroforensic Analysis of the Wounds of President John F. Kennedy: Part 2—A Study of the Available Evidence, Eyewitness Correlations, Analysis, and Conclusions,” Neurosurgery. Available here.

[13] Warren Report, p. 585. Available here. See also Warren Commission testimony of Alfred Olivier, DVM, 5H, p. 89. Available here.

[14] See JFK Exhibit F-48. In HSCA, Vol. 1, p. 234. Available here.

[15] Horne, Douglas, Inside the Assassination Records Review Board Volume 2, p. 656.

[16] HSCA Vol. 6, p. 226. Available here.

[17] See Memorandum for File on 8/27/1998 by the ARRB’s Douglas Horne, entitled, “Unanswered Questions Raised by the HSCA’s Analysis and Conclusions Regarding the Camera Identified by the Navy and Department of Defense as the Camera Used at President Kennedy’s Autopsy. Available here.

[18] Alvarez, L. A physicist examines the Kennedy assassination film. Am J. Physics, 1976; 44 (9):813 ff. Available here.

[19] Olson D, Turner RF, “Photographic evidence and the assassination of president John F. Kennedy,” Journal of Forensic Sciences, 1971; Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 399–419. Available here.

[20] Ken Scearce & Brian Roselle. “Secrets of the Zapruder Film.” Available here.

[21] HSCA Vol. 6, p. 26. Available here.

[22] Zapruder frames 224 and 227. Available here and here.

[23] Zapruder frames 117 and 316. Available here and here.

[24] Thomas, D B. Hear No Evil, Ipswich, MA: Mary Ferrell Foundation Press, 2010, p. 202-215. Available here.

[25] Secret Service Agent Max Phillips interviewed Zapruder on 11.22.63. His memo appears nowhere in the Warren Commission documents or volumes. It was discovered at the National Archives by Mr. Harold Weisberg. Agent Phillips reported that “According to Mr. Zapruder the assassin was behind Mr. Zapruder.” Weisberg H. Whitewash III: The Photographic Whitewash of the JFK Assassination, New York, Skyhorse Publishing, 1967. See text under “Section I – The New Math and the New Morality.” Available here.

[26] Zapruder frame 331. Available here.

[27] House Select Committee on Assassinations testimony of Larry Sturdivan, September 8, 1978, 1H, p. 404. Available here.

[28] Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths, St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. 164.

[29] HSCA testimony of Larry Sturdivan, September 8, 1978, 1H, pp. 413–414. Available here.

[30] HSCA testimony of Larry Sturdivan, September 8, 1978, 1H, p. 404. Available here.

[31] HSCA testimony of Larry Sturdivan, September 8, 1978, 1H, pp. 413–414. Available here.

[32] HSCA testimony of Larry Sturdivan, September 8, 1978, 1H, p. 404. Available here.

[33] Thomas, Donald B. Hear No Evil, Ipswich, MA: Mary Ferrell Foundation Press, 2010, pp. 344–345.

[34] Larry Sturdivan apparently agrees. He wrote: “Neurosurgeon Dr. Michael Carey thinks that (JFK) may be falling (by Zapruder frame 312) as a result of temporary paralysis from the spinal damage associated with the neck wound.” Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths, St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. 209, note 96.

[35] Thomas, Donald B. Hear No Evil, Ipswich, MA: Mary Ferrell Foundation Press, 2010, pp. 345–346.

[36] “How Much Does the Human Head Actually Weigh?” Available here.

[37] Thomas, Donald B. Hear No Evil, Ipswich, MA: Mary Ferrell Foundation Press, 2010, pp. 345–346.

[38] HSCA Exhibit F-53, enhanced lateral skull x-ray, HSCA Vol. 1, p. 240. Available here.

[39] HSCA testimony of Larry Sturdivan. Vol.1:401. Available here.

[40] Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths, St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, Fig. 38, p. 173.

[41] Sturdivan LM. The JFK Myths, St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. 177.

[42] Source: Sturdivan, LM, Review of JFK Photographs and X-Rays at the National Archives, September 23, 2004. Available here.

[43] Warren Commission testimony of James H. Humes, MD, Vol. 2:353. Available here.

[44] Warren Commission testimony of Secret Service Agent Roy Kellerman. Vol. 2, p. 100. Available here.

[45] Clark Panel Report, pp. 10–11. Available here.

[46] “Inside the ARRB: Appendices – Current Section: Appendix 44: ARRB staff report of observations and opinions of forensic radiologist Dr. John J. Fitzpatrick, after viewing the JFK autopsy photos and x-rays,” p. 2. Available here.

[47] Chesser, M. A Review of the JFK Cranial X-Rays and Photographs. Available here.

[48] DiMaio, VJM. Gunshot wounds – Practical Aspects of Firearms, Forensics, and Ballistics Techniques, Third Edition, p. 166. Available here.

[49] Sturdivan, LM, The JFK Myths, St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2005, p. 171.

[50] Sturdivan, L. “Review of JFK Photographs and X-Rays at the National Archives, September 23, 2004.” Available here.

[51] Clark Panel Report. Available here.

[53] Ayoob, M. “The JFK Assassination: A Shooter’s Eye View,” American Handgunner, March/April, 1993, p. 98.

[54] IBID, p. 105.

[55] IBID, p. 106.

[56] LSID, pp. 353–4.

[57] Jeff Morley. “21 JFK Cops Who Heard a Grassy Knoll Shot.” Available here.