Review by Jerome Corsi

On January 4, 2023, Dr. David Mantik, M.D., Ph.D., published The JFK Assassination Decoded: Criminal Forgery in the Autopsy Photographs and X-rays, a beautifully printed more than 500-page magnum opus complete with color illustrations compiling his decades-long investigation into the case. The JFK Assassination Decoded is not just another Kennedy assassination book.

Mantik deserves an honored place in the pantheon of JFK researchers for his definitive forensic proof that JFK was shot from the front, hit by two shots from the right front, and one shot from the rear. Mantik’s book is a “must-read” JFK book that belongs in the library of every serious study of the assassination for its definitive treatment of the JFK headshots. Perhaps even more critical, Mantik allows us to see disinformation campaign parallels, suggesting both the JFK assassination and the removal of Donald Trump from the presidency were both Deep State planned and executed coup d’états.

Mantik’s forensic analysis of the JFK autopsy X-rays proves Lee Harvey Oswald could not have been the assassin. Equally important, Mantik’s new book allows us to see the Deep State parallel between the JFK assassination and the DOJ/CIA conspiracy to remove President Trump from office. The Justice Department and the CIA conspired to infiltrate and control social media to conceal the Deep State’s role in fabricating the Russian collusion hoax to destroy Donald Trump’s presidency. So too, Allen Dulles penetrated the Warren Commission to cover the Justice Department and CIA’s complicity in the crossfire in Dealey Plaza that removed JFK from the White House.

In nine separate trips to the National Archives over multiple years, armed with scientific apparatus including a Tobias optical densitometer, Mantik spent a record time examining the original JFK autopsy X-ray films. His brilliantly conducted optical density measurements proved that the autopsy X-rays had been altered to mask the frontal shots. Mantik traced and measured bullet fragments that transited Kennedy’s brain from the front to the back, establishing indisputable “case closed” proof that the official government narrative pinning Lee Harvey Oswald as the assassin was false. Mantik is eminently qualified to conduct this forensic analysis. He received a doctorate in physics from the University of Wisconsin and his M.D. from the University of Michigan. Mantik has spent some 40 years practicing as a board-certified radiation oncologist.

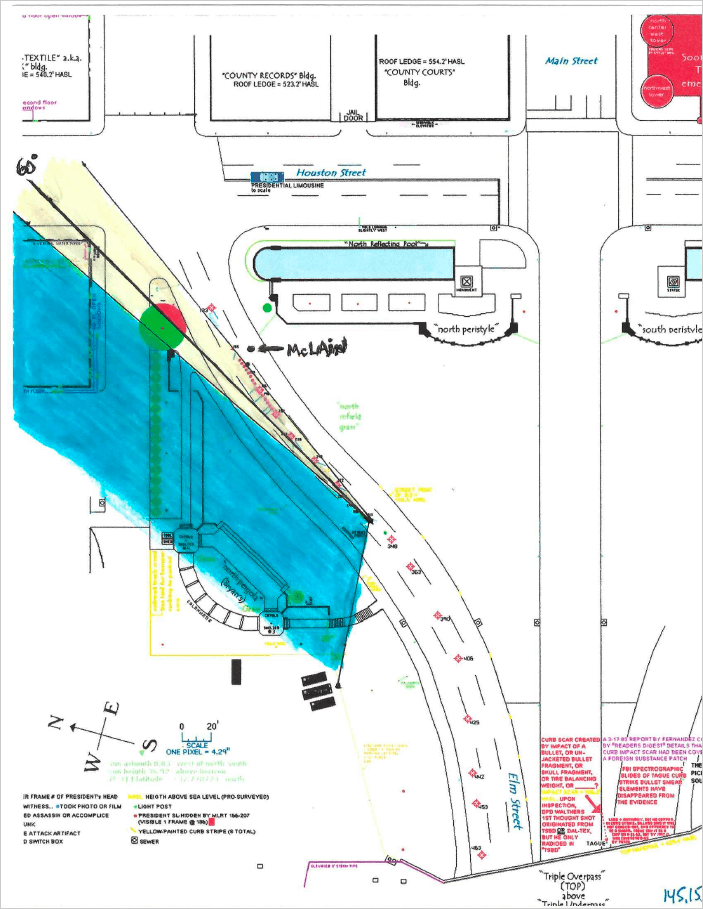

Mantik bolsters his argument with his anatomical analysis of the Harper fragment, demonstrating that the bone fragment found on Elm Street was from the mid-occipital region, squarely in the back of JFK’s head, blown out of the back of JFK’s skull by an oblique shot from the right front. Mantik also demonstrated that at the extreme right edge of the Harper fragment is a metallic smear that evidenced a shot from the rear entering the back of JFK’s head from a low-angle shot to the rear of the limousine. The low angle of the rear-entry shot suggests a shooter may have been in the Dal-Tex building, not on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, where the Warren Commission positioned Oswald as the sole assassin.

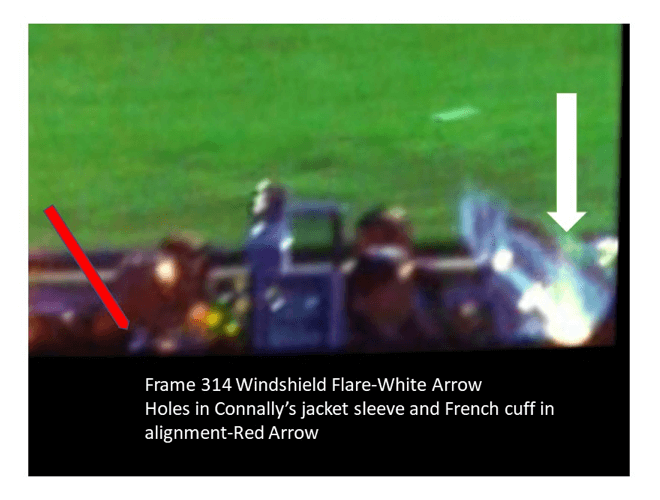

Mantik teamed with Douglas Horne, author of the five-volume Inside the Assassination Records Review Board, to conduct an equally rigorous examination of the front windshield of the presidential limousine. Through Doug Weldon, Mantik obtained first-hand testimony from George Whitaker, Sr., a Ford Motor Company supervisor, that he saw the JFK limousine in Dearborn, Michigan, on Monday, November 25, 1963, the day of JFK’s funeral. Whitaker and a second Dearborn witness (the father of Mantik’s Michigan Medical School roommate) saw a hole in the windshield from a frontal shot. Within minutes of the assassination, the Secret Service began cleaning the blood from the limousine, obviously destroying crime scene evidence. The Secret Service secreted the limousine, not allowing an inspection of the front window while it was yet in the limousine. In an August 1993 interview, Whitaker claimed to have replaced the windshield on Monday, November 25, at the River Rouge Assembly Plant, Building B, in Dearborn, Michigan. Whitaker recalled a hole in the windshield, 4-6 inches to the driver’s side of the rear-view mirror. He claimed the shot came from the front and the significant damage was on the inside of the windshield, as would be expected for standard contemporaneous safety glass. Mantik published in the book a photograph showing the JFK limousine stripped down to its frame at the Hess and Eisenhardt factory in Cincinnati in December 1963.

Mantik established through photographic evidence several images where a bullet appears to hit the limousine’s front window at Z-255 [Zapruder Film, Frame 255, coincident with Altgen’s Photo #6], well ahead of the headshots that occurred after Z-300. Mantik documented that during the JFK autopsy, the pathologists recognized that the 5-centimeter contusion at the right lung apex was not caused by Dr. Malcolm Perry’s tracheotomy performed on JFK at Parkland Hospital in a desperate attempt to save his life. Mantik noted a bullet entered near the midline of JFK’s throat at about the third tracheal ring and traveled obliquely to the right lung apex, where it stopped. As further confirmation that the projectile causing the throat wound had a limited (non-exiting) trajectory, Mantik noted the pathologists conducting the autopsy found no deep penetration from JFK’s back wound. “They ignored this,” Mantik wrote, “and instead invented the single-bullet theory.”

In a review of Mantik’s book, Douglas Horne notes that Mantik’s analysis of the JFK X-rays confirms Horne’s analysis in Chapter 13 of Inside the Assassinations Review Board. Both Horne and Mantik agree three headshots hit JFK:

- A shot low in the posterior skull, from the rear (probably fired from the second-floor window of the Dal-Tex building), blowing out the “head flap” on JFK that the Zapruder film shows prominently;

- An almost simultaneous shot from the right front (probably fired from well down the grassy knoll, near where the triple overpass meets the knoll); and

- A third almost simultaneous shot from the right front (fired from near the corner of the grassy knoll stockade fence), hitting JFK above and slightly behind the right ear.

In his review of Mantik’s volume, Horne comments that Mantik’s book, “backstopped by extraordinary detail and footnoting, and by brilliant clarifying illustrations, is the “final word” on the JFK headshots. “Dr. Mantik brings his expertise as an M.D.—a radiation oncologist quite familiar with and qualified to read skull X-rays—and as a physicist to this extensive, illustrated monograph.” Horne added that equally important is that “Mantik’s conclusions about the three headshots, and the alteration of the extant skull X-rays, prove there was a massive U.S. government cover-up regarding how JFK was killed.”

Editor’s Note: Via the late Robert Parry, we always thought the whole Russiagate caper was a mirage. And that is what it has turned out to be. Jerome was entangled in that ersatz imbroglio so we have allowed him to refer to it.

Review by James DiEugenio

David Mantik’s new book is really two books. First, it contains his ebook, JFK’s Head Wounds which includes what is probably the most extensive study of the Harper fragment in print. The rest of the 400 or so pages are a collection of what Mantik feels is his best prior writing on the case combined with some new work not seen before. Two of these latter essays were, for me, high points of the book. Namely a lengthy analytical critique of Josiah Thompson’s Last Second in Dallas; the other is an investigative essay on the possibility that the Kennedy limousine was struck by a bullet through the front windshield.

Before we get started, let me make some descriptive comments about the book. First, it is in hard cover, which is kind of unusual in and of itself these days. Second, the book is an oversized volume. Which means that when I write that it is about 500 pages long, that is only numerical. In reality its more like 650 pages in length. Third, the reader will search far and wide to find a more extravagantly produced volume on the JFK case. What I mean by that is that the book is profusely illustrated with both pictures and graphics; there must be literally hundreds of these kinds of illustrations in the volume. And many of them are in color, which is another unusual trait in the modern publishing business. In that aspect, I cannot recall seeing a book like this in, quite literally, decades.

Let me make one other preliminary observation. Dave Mantik is one of the most well-read Kennedy assassination critics there is. So when one reads the footnotes to his essays, one will find references to sources that one never heard of before. I know this will happen with the reader because it happened with me. And most people consider me one of the most well read and informed critics that there is. Well, Mantik sprung more than a few surprises on me.

I

The author begins his book by listing what he considers to be some of the major paradoxes in the JFK case. For instance, the mystery of Kennedy’s brain which is pretty much intact on the pictures. But which he and Cyril Wecht showed had to be missing a major amount of mass according to the x-rays. (pp. 4-6). This pungent observation is a summary of the essay those two men wrote for the book The Assassinations. (Edited by James DiEugenio and Lisa Pease, pp. 250-71) I am glad Mantik included this since that essay has been pretty much overlooked, and it should not be. Another paradox being the undetected presence of a 6.5 mm fragment on the Kennedy x-rays that was first noted by the Clark Panel in 1968. (pp. 6-8). A third being the plentiful dust like particles in the forehead area of JFK on the x-rays, which strongly indicate a shot from the front. (p. 10)

There are seven others, but I think this gives the reader the drift of what the author is going after here. These are distinctly abnormal aspects in the medical record, ones that simply do not match up with the official conclusion of the Warren Report. That conclusion was that two full metal jacketed bullets, both from behind, went through Kennedy. One in the back and one in the head, the head shot being the kill shot. In other words, that verdict does not stand up under scrutiny from qualified experts like Mantik and Wecht. And these are aspects that are obvious in the official records themselves. Therefore, if one produced these records in court, the prosecution would be quickly placed on defense explaining these anomalies. Which would not be easy to explain. Because things like this do not happen in the normal course of a homicide inquiry. And if they did, the court would quickly suspect some kind of subterfuge or fraud.

This lays the backdrop for what the book is about. For instance, the first chapter after this focuses on the saga of the 6.5 mm fragment near the back of the skull. To say the least, it is not easy to explain. Because it was not seen by any of the pathologists the night of the autopsy. As the author notes, you will not read about it in the Warren Report or the 26 volumes of evidence.(p. 20)

What makes this even more odd is the fact that it happens to be the same size and caliber of the ammunition that Lee Oswald was allegedly using the day of the assassination. When the HSCA matched the Anterior posterior x-ray with lateral on this object it was revealed that the object had almost no thickness to it, it appears to be a slice of a fragment. (p. 21).

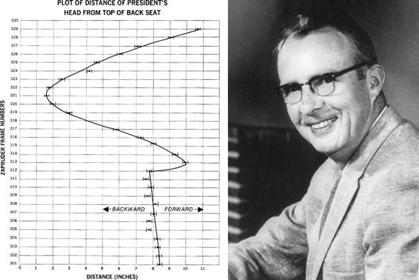

The other peculiar characteristic is that when Mantik took optical densitometry readings on the object, it turned out to have a density to it that was off the charts. Far surpassing, for example, the 7 x 2 mm fragment. Warren Commission ballistics expert Larry Sturdivan believes this is an artifact. The question is what kind of artifact is it? Is it accidental or manmade. What argues for it being the latter is not just the caliber, but the position. The early critics, especially Josiah Thompson, did not think that a bullet coming in at a low part of the skull matched up with the position of Kennedy’s head at Zapruder frame 313. (Six Seconds in Dallas, p. 111) By raising the bullet strike four inches upward, it did something to solve that trajectory problem.

II

The next point of evidence the author will argue is a pet concern of the radiologist, namely the Zapruder film. This reviewer is an agnostic on the subject. But to be fair to him and Sydney Wilkinson–a film editor in the movie business–she and Mantik went to the Sixth Floor Museum and they saw transparencies produced by the MPI company, which produced a video and DVD version of the film. In 2009, they claim to have seen what is a black patch over the back of JFK’s head, with straight edges. Yet there is nothing like that on John Connally. Mantik says it is most obvious at Z-317. (p. 36).

But when Sydney returned in 2010 the transparencies were larger but not as sharp and clear. The dark patch was gone, and looks more like a shadow. Mantik returned in 2012, and had the same reaction. But the Sixth Floor Museum insists there was no change from the material in 2009. The way to test this would be to find the original Time/Life transparencies from 1963-64. But the Sixth Floor says they do not have them and the searches done by Sydney and Mantik have been unable to turn them up. I have seen the third generation dupe that Wilkinson has and on that copy I did see that black spot. It is really an evidentiary shame that there is no locating the first generation transparencies.

The next two chapters deal with Vincent Bugliosi. When I was reviewing Bugliosi’s mammoth Reclaiming HIstory, I called up Gary Aguilar and asked him if he was critiquing the book. He said yes he was. I asked: “Did you read the whole book?” Gary replied with, “Are you crazy!.”

Well I did read the whole book, and so did Mantik. In addition to specifics, the doctor and former physics professor goes after Bugliosi on a general thematic charge. Namely that what suffices for truth for an attorney is not the same as what a scientist considers as truth. (pp. 48-49)

From here, the doctor and scientist now lists 12 main points of factual evidence that the lawyer either denies in part, or simply ignores completely. The author writes about each of them over four pages. (pp. 53-57) Each point is not a matter of eyewitness observation or a circumstantial trial of evidence. Each deals with what most lawyers call “hard evidence”. Some of these I had not really heard of before or examined. For example, Commission Exhibit 843. This is a picture of lead fragments which came from Kennedy’s skull. As Mantik states it, the problem is they do not resemble their shapes or sizes on the x-rays. He then adds, “No interval testing should so have morphed its appearance.” (p. 54). Another example: stereoscopic viewing of the back of the head photos reveals “a flat, two dimensional image…” And this appears on the part of the image with “the shiny part of the hair that looks so freshly washed….” The author tried everything on this issue, “switching photos left to right, rotating them, and even looking at pairs of color prints and then pairs of color transparencies and then pairs in black and white.” In each instance the image was the same, two dimensional. (p. 55)

It is a pretty impressive list which illustrates the author’s thematic point. As part of his summary, Mantik pens an insightful point. He writes that the aim of the book was to

….destroy every last scintilla of anti-WC evidence….That makes him all the less credible. And it certainly does not give him the air of a scientist. But he does not seem to care. He would prefer to appear omniscient. (p. 59)

The author then reviews a later book by Bugliosi, Divinity of Doubt. Mantik, who has clearly studied the subjects of atheism, agnosticism and deism, gives the book a thorough thrashing. Concluding that Bugliosi should have never written about an area in which he had such poor mastery of the subject matter. (p. 66-67)

III

The next section of the book is composed of Mantik’s critiques of authors like the late Sherry Fiester, Randy Robertson and Fred Litwin. Although disagreeing with some of her points, he treats Fiester with respect. And, as we shall see, he seems to adapt one of her theorems—a shot from the south knoll.

He has little or no respect for Fred Litwin. And, in my view, his critique of I Was a Teenage JFK Conspiracy Freak is a masterful polemic. It stands as a model of what negative criticism can and should be. Because not only does it destruct the subject, it educates the reader as to what the true facts are.

He and Robertson have a fundamental disagreement about the evidence as a whole. Robertson thinks everything is genuine and on the up and up. Mantik does not. For instance, Robertson thinks the 6.5 mm fragment is genuine. He also believes that the ammunition was all uniform full metal jacketed (FMJ). Mantik asks how could a FMJ bullet produce the snowstorm effect of the dustlike particles in the forehead. (pp. 150, 155)

Right after this comes another model of negative criticism. This time it is Mantik’s review of the late John McAdams’ book JFK Assassination Logic: How to Think about Claims of Conspiracy. The opening of this review shows the kinds of harpoons Mantik landed on the late Marquette professor. McAdams was attempting to show the reader how to think about the JFK case in a logical manner. Here is how Mantik leads off:

Despite his pompous claim to teach all of us how to think critically, McAdams offers not a single reference to standard works on logical fallacies. Nor does he ever present his unique credentials for this task….In order to persuade the reader to vote for his dubious conclusions, he uses the standard tools of manipulation and commits a variety of crimes against logic-the straw man, the invalid analogy, begging the question, special pleading, the false dichotomy, and the moving goalpost. (p. 159)

He spends most of the rest of this review exhibiting examples of this propagandistic type of writing.

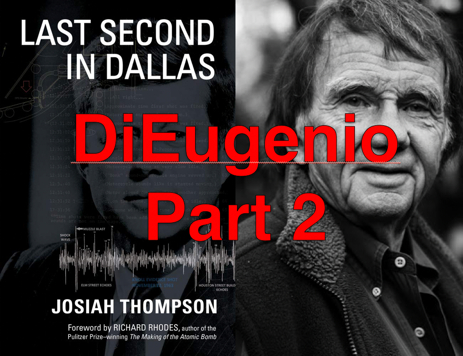

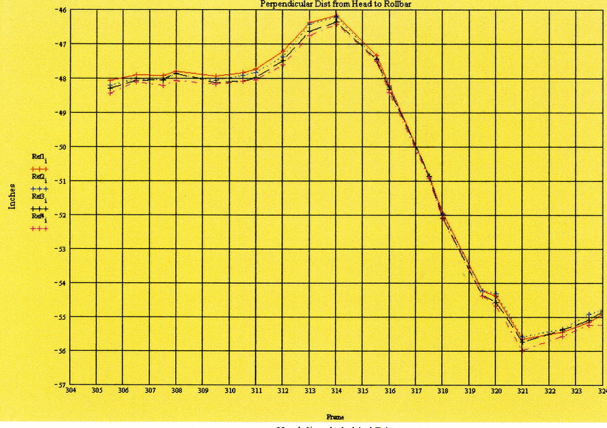

Mantik’s review of Josiah Thompson’s Last Second in Dallas is quite illuminating and thorough. Like Robertson, he questions the shot sequencing proposed by Thompson. He does this on what seems to me to be sound grounds. And it relates to his grand exposition of the Harper fragment which will come later in the book, but is introduced here. Mantik believes that the shot from the rear must have come before the frontal shot. (p. 263) If Thompson is proposing that the frontal shot dislodged Harper, then how did the outside smear get on the Harper fragment? This is a telling observation. Especially since Thompson is very familiar with the Harper fragment. (pp. 263-64)

Mantik reminds us that Thompson wrote that Oswald shot TIppit and that the anterior neck wound was an ejection for a bone or a metal fragment. Mantik pretty much takes the book over the coals on the latter supposition. (pp. 268-69). Mantik’s disagreement with Thompson and James Barger and Rich Mullen—all of whom back the HSCA acoustics findings—is one of the most fascinating discussions one will read on that subject. This one review has ten appendixes to it. They include three comments by Michael O’Dell, who, in my opinion, is the single most knowledgeable person on the subject. If the reader ever wants to learn about the many sides to this argument, they are presented in this review.

IV

I wish to close my review of this valuable book by addressing the final essay and also the second book in the volume. You are not reading wrong: there is a second book with its own pagination. It’s a reprint of Mantik’s E book, JFK’s Head Wounds. But before we get to that let us discuss the subject of Mantik’s CAPA speech this past November. The doctor gave a compelling Powerpoint presentation on the mystery of the JFK windshield. I had never seen the issue reviewed this clearly and pointedly. And yes, I have seen the late Doug Weldon’s lectures on Youtube. The combination of Mantik’s lecture, and his essay in this book, caused me to go back and read two previous treatments of the topic. They would be Weldon’s long essay in Murder in Dealey Plaza, and Doug Horne’s much shorter review in Volume 5 of Inside the ARRB.

But to place the problem in historical perspective, and to give proper credit, the late David Lifton actually wrote a rather fair precis of the imbroglio in Best Evidence. (pp. 370-71) There, in two pages, he gives the outlines of the apparent paradox. As he writes, there was credible eyewitness testimony that there was a hole in the front windshield when the limousine arrived at Parkland Hospital. For instance, two Dallas policemen, H. R. Freeman and Sgt. Stavis Ellis, both saw a hole. Ellis was certain about this, “It was a hole. You could put a pencil through it….” (Lifton, p. 370)

Mantik’s list, quite naturally, is longer than Lifton’s. He lists nine witnesses. In addition to the policemen: medical student Evalea Glanges, Secret Service agents Joe Paolella, and Charles Taylor, reporters Richard Dudman and Frank Cormier, Ford Motor supervisor George Whitaker, and Secret Service agent Bill Greer, as told to Nick Prencipe of the US Park Police. (Mantik, p.321) The author finds this testimony credible. Further, he says the hole is most visible in the Altgens 6 photograph. (p. 323) He showed this in Dallas, and I had to say, it looked like a hole to me.

Vaughn Ferguson was the go between for Ford Motor and the White House. He wrote a memo on December 18, 1963 that the author depicts as odd. Mantik spends the better part of two pages going through this memo and pointing out some problems. One of the massive ones is this: James Rowley, Chief of the Secret Service, wrote a letter to J. Lee Rankin of the Warren Commission on January 6, 1964. In that communication, Rowley declared the limousine was in the White House garage until December 20th. At that time Vaughn Ferguson drove the limo to Dearborn. Four days later it was driven to Hess and Eisenhardt in Cincinnati, a longstanding custom car company, for the installation of the bullet resistant bubble-top. (Mantik, pp.343-46)

Even the rather somnolent House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) had problems with the Rowley and Ferguson summary. As Weldon noted, the HSCA had four conflicts with the dates in the letter. A clear and obvious one is this: the limo was provably in Cincinnati on December 13th—a full ten days before Rowley said it was. (Weldon, Murder in Dealey Plaza, p. 133) In fact Willard Hess told Weldon that this December 20th journey would not and could not have happened. Hess was very disappointed that the Warren Commission only contacted him once, and then very briefly.

As both Mantik and Weldon point out, there is another serious problem with Ferguson’s account. He wrote that the cracks in the windshield radiated from very close to the center and at a point right below the mirror. (Ibid, p. 134). This is simply false; so much so that one wonders if Ferguson really wrote the memo with the car in front of him.

In 1993 Doug Weldon found a contradictory witness from Ford Motor Company. At that time he wished to remain anonymous, so Weldon used his information without naming him. Later it was revealed that his name was George Whitaker. Whitaker wrote that he worked at Ford and he got a call from the Vice President of the Division on November 25th. He was wanted in the glass plant immediately. (Horne, Inside the ARRB, p. 1446) The Lincoln was in the Rouge Plant of Ford Motor on the morning of that day. Called to report to the glass lab, he was let in a locked door. There were two engineers there and they had a car windshield that had a bullet hole in it. It was about 4—6 inches to the right of the mirror. From his forty years of experience with glass works, he knew the impact had come from the front. (Mantik, p. 370)

As the author continues, Whitaker said they were to use the blasted windshield as a template, which had been taken out. When they were finished they were to take it to the B building. When they finished they placed it in the limousine, which had everything stripped out. It is worth quoting Whitaker as to his description of the hole: “…it was a good clean hole right straight through from the front.” (Horne, p. 1446)

Mantik makes a circumstantial case that Rowley ordered the limo flown to Dearborn in either the late hours of the 24th or the early hours of the 25th. As no one could risk doing something like this in Washington at that time. (Mantik, pp. 328-29). The good doctor makes an extraordinary contribution to all this. He had an acquaintance from his days at the University of Michigan Medical School and this man’s father worked at Ford and had seen the limousine in Dearborn after the assassination. It turns out that this man, Robert D. Harrison, had seen the perforated windshield—and had been very upset by this. (Mantik, p. 347)

I should add that Mantik, Horne and Weldon all make a rather trenchant observation about the original windshield. Roy Kellerman and Morgan Geis of the Secret Service both said they saw the damaged windshield and the outside was smooth, the damage was on the inside. But safety glass only shows damage on the other side from which its hit. Which means, what these observations show is that the impact was from the front. (Horne, p. 1449). Mantik takes this further and shows how someone realized this was a mistake and they tried to paper it over later. His demonstration continues with examples of how safety glass is supposed to shatter, and also in discrepancies as to comparisons between the supposed same windshield. (Mantik, pp. 332-34)

Let me add that, Mantik concludes that if he is correct on this the shot likely came from the south knoll. And as he does throughout, he finds and recommends a good paper that argues for just such a shot, this one is from a gentleman named Anthony DeFiore.

V

I cannot hope to do justice to what Mantik has done with his analysis of what he thinks were the shots to President Kennedy’s head. But I should add that this 100 page mini-book does not just do that. In fact, the main reason Mantik wrote it was to advance his concept of the proper location of the so called Harper Fragment.

As the author explained in Oliver Stone’s recent documentary, the Harper fragment was a piece of bone that was expelled from Kennedy’s skull in Dealey Plaza. No one really knows where it was originally located for the simple reason it was not found until more than a day later. (Mantik, p. 36). In fact, Mantik includes reports about this happening i.e. law enforcement officers picking up a piece of bone and moving it slightly before leaving it behind.

After Billy Harper picked up the piece of bone he gave it to his father who was a pathologist. Jack Harper and two other pathologists at Methodist Hospital—Gerard Noteboom and A. B. Cairns– photographed it and examined it. (p. 1) They concluded it was from the occipital part of the skull. In talking to Noteboom, Mantik garnered that there was a metal smudge on the edge of the bone. (p. 2).

From this point, Mantik argues against other placements of the Harper Fragment. He essentially takes on everybody. That means other critics and also the HSCA. His review of what the HSCA tried to do with the Harper Fragment—greatly aided by the late John Hunt—makes for quite insightful reading. (pgs. 5-8; 15-18) The HSCA’s Michael Baden said the Harper Fragment was from the parietal region. A judgment with which Mantik strongly disagrees.

From here, the author proceeds to take on the arguments and placements of Dr. Joseph Riley (pgs. 23-30), Dr. Randy Robertson (pgs. 18-21), and Richard Tobias (pgs. 21-22). The remarkable thing about all of these debates is how Mantik’s investment in the book’s production values serves him quite well. One will search far and wide to find a book with as many technical and medical pictures and illustrations as this one. And this greatly aids the average reader in following the technical arguments Mantik lays out in front of him.

That argument is going to end with two main concluding statements.

The first is that Kennedy was hit with three shots in the head. One came from behind, two from in front. There was one in the high right forehead; the other was an oblique shot that hit adjacent to the right ear and exited the occiput while ejecting the Harper Fragment. (p. 58) He also argues that there was at least one shot fired after Z frame 313. For those who are enamored with this kind of discussion, the author includes a lengthy appendix—among several others—which explains in detail what he calls his Three Headshot Scenario. ( pp. 76-85) He even produces a new witness to a picture of the forehead shot. (pp. 86-88)

The other concluding argument is this: the Harper Fragment was not part of the parietal bone, but part of the upper occipital bone. That description would denote the rear of the skull, in or about the center area. (p. 11). According to his orientation, the metal smudge connects with the bullet hole located by the pathologists at Bethesda that night around the External Occipital Protuberance.

In the end I would have to agree with his 15 step argument.

After the debut of Oliver Stone’s 1991 film JFK, a whole new wave of writer/researchers entered the debate over the true circumstances of President Kennedy’s death. Some of these were physicians who concentrated on the medical aspects of the assassination. It is difficult to name one who has achieved more than David Mantik. This book stands as a statement to that significant accomplishment.