He leaned on JFK to stay out of Vietnam. Had Kennedy survived, might history have been different?

By Mark Perry, At: The American Conservative

He leaned on JFK to stay out of Vietnam. Had Kennedy survived, might history have been different?

By Mark Perry, At: The American Conservative

In part 2 we will continue our journey into Oswald’s wondrous world and discover that his USSR defection was only a part of the larger picture. Moscow and Minsk were only stops, but not the destination of his journey. These stops were to become part of his resume, to create a “Legend” who will return home pretending to be a Soviet spy in order to infiltrate suspected communists, subversives, and supporters of Castro. From the beginning that destination was Cuba; it has always been about Cuba.

Marguerite Oswald was in disbelief when she was informed that her son had defected to the Soviet Union. In September, her son visited his mother in Fort Worth after his discharge from the Marines and told her that he wanted to travel to Cuba. In February, an FBI agent, John Fain, interviewed Marguerite regarding the whereabouts of her missing son. He later stated in his report that “Mrs. Oswald stated he would not have been surprised to learn that Lee had gone to, say, South America or Cuba, but it never crossed her mind that he might go to Russia or that he might try to become a citizen there.”1

When Oswald tried to defect to the USSR, a wire service noted that his sister-in-law said “that he wanted to travel a lot and talked about going to Cuba.”2 Similarly, when he returned back to the States, a 1962 Fort Worth newspaper recalled what Oswald said to his family: “He talked optimistically about the future. Some of his plans had included going to college, writing a book, or joining Castro’s Cuban army.”3

Oswald’s travel destinations included Cuba, the Dominican Republic, England, Turku Finland, France, Germany, Russia and Switzerland. One has to wonder how the recently discharged Marine would have been able to fund a trip that involved so many countries that were far apart from each other, like Cuba and Russia. Before leaving the Marines, he applied for a passport on September 4, 1959 and received it on September 10, 1959. To apply for the passport he used for identification a Department of Defense (DOD) I.D. card, although he could have provided his birth certificate. As George Michael Evica noted, “Lee Harvey Oswald should never have had a DOD I.D. card on September 4, 1959, possibly on September 11th, but not on September 4th.”4 September 11 was the date that he was to be transferred to the Marine Corps Reserve, once his active duty was over.

The Marine Corps confirmed that it had issued the card before he was discharged, but this kind of practice ended as of July 1959, so he was probably issued the DOD I.D. card because he was going to fill a civilian position overseas that required it.5

Too many peculiarities surround the young ex-Marine, his DOD I.D. card, his passport application, the countries he was planning to visit and the expenses needed to support such a trip. All these were enough to sound the alarm bells in the intelligence community, but somehow this did not happen.

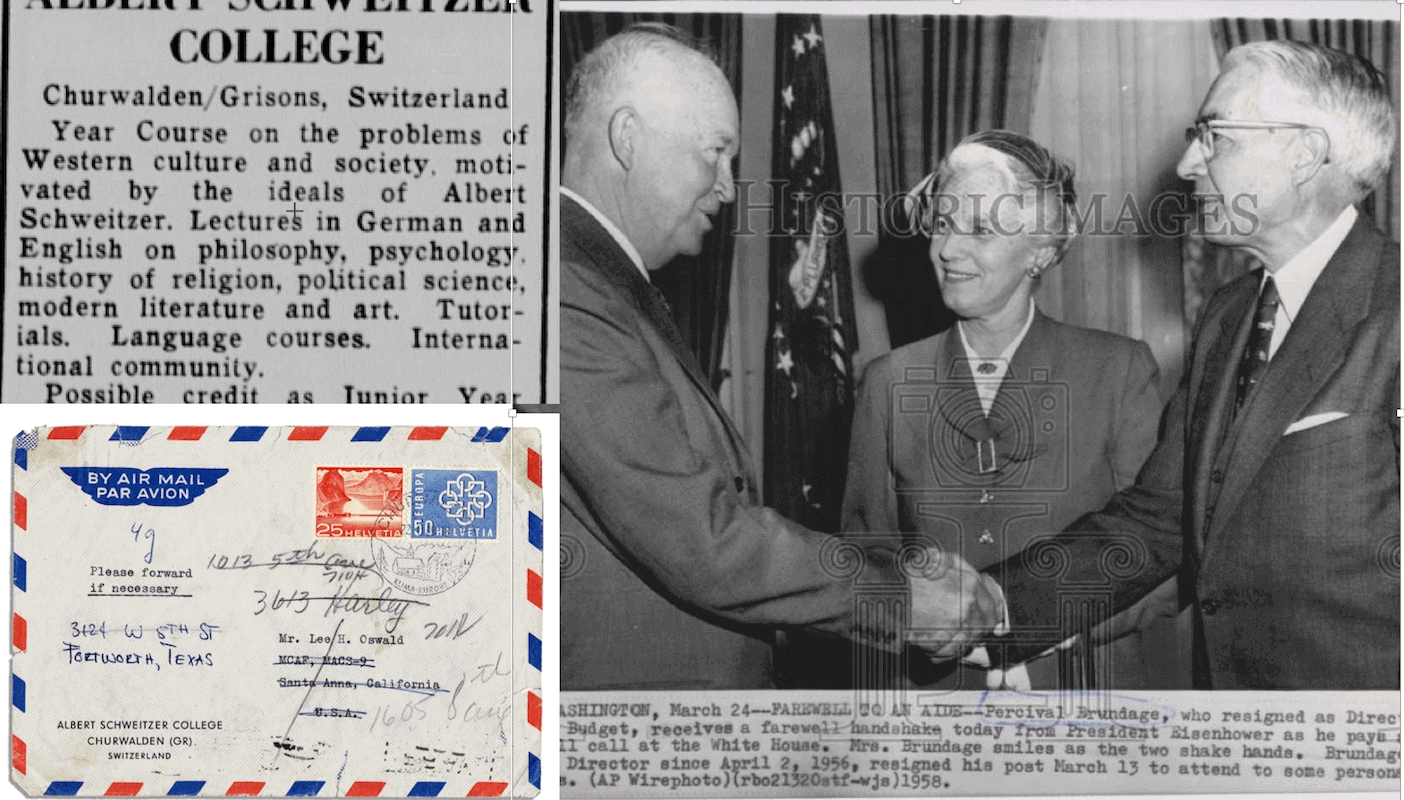

Oswald had also stated in his passport application that he intended to study in Europe, and he named two institutions. One was the Albert Schweitzer College (ASC) in Churwalden, Switzerland, and the second was the University of Turku in Finland.

Oswald sent his application to the ASC on March 19, 1959, informing them that he was going to attend the third (spring) term of the trimester schedule, from April 12, to June 27, 1960, followed by a registration fee payment of $25 on June 19. However, this time length posed a problem by itself. Oswald’s passport was valid for four months overseas, so if he wanted to attend its third trimester, then his passport should have been valid for nine months, an extra five months. According to his passport, he could have only made it to study the fall trimester of 1959, and then only if he was given an early discharge, which actually happened.6 Oswald was released from the Marines with a dependency discharge on September 11, 1959 to go to Fort Worth to take care of his injured mother. However, his mother had only a minor injury and Oswald left for New Orleans on September 17, 1959, to begin his trip to Europe. A year later, after his defection to the Soviet Union, he was given an undesirable discharge from the Marine Corps, something that was to haunt him to his final days.

In 1995 the Assassinations Records Review Board (ARRB) revealed the communication between the FBI Legat at the Paris Embassy and FBI Director Hoover. The FBI Legat had sent Hoover five memoranda regarding Oswald’s intentions to study the ASC.

The first memorandum was dated October 12, 1960. It was based on information from the Swiss Federal Police and stated that Oswald was planning to attend the fall trimester of 1959. The second memorandum was a strange one, since it stated that Oswald “had originally written a letter from Moscow indicating his intention to attend there (at Churwalden).”7

This was an extraordinary turn of events, as the second memorandum implied that Oswald was planning to attend the third trimester, similar to his college application and the Warren Commission’s conclusion.

The fourth and fifth memoranda were even more peculiar. They revealed that Oswald had not attended the course under a different name and that there is no record of a person possibly identical to Oswald attending the fall trimester.

The above information should have sounded the alarms in FBI HQ because they suspected that since he did not attend the college he had brought with him his passport and his birth certificate to the Soviet Union. Even Marguerite Oswald, when asked by FBI agent Fain about her son’s whereabouts in Europe, replied that Lee has taken his birth certificate with him.

The above information forced Hoover to send an enquiry to the Office of Security in the Department of State regarding the “missing” Lee: “Since there is a possibility that an impostor is using Oswald’s birth certificate, any current information … concerning subject (Oswald) … ”8

Hoover, like his agent before him, suspected that Oswald had fallen victim to a Soviet spy ring that would have used his birth certificate to create a false identity which an “illegal” spy would adopt to enter the United States as a sleeper agent.

The illegals were not under diplomatic protection like their legal counterparts that were usually connected to a Soviet embassy. They would resume the life of an American, probably one that has died, live a normal capitalistic life and would be activated when the need arose.

Switzerland had been a center of espionage since WWII. Soviet illegals would never send or receive mail directly to/from the Soviet Union but would use neutral countries like Switzerland as a cover address to avoid detection. It is a surprise that the CIA counter-intelligence mole hunters did not open a 201 file on Oswald as soon as he defected. In fact, they did not do that for over a year. Instead, they put him on the HT/LINGUAL list of about three hundred Americans whose mail was secretly being opened.9 This would be an indication that Oswald was used to detect illegal networks in Switzerland by detecting their mails.

The ASC was reputed to be a place where liberals, communists and Marxists would go to study, perhaps being a possible illegal passing point. By applying to this college, even if he never went there, it could appear that his birth certificate was used to create an illegal in Switzerland that would later use his identity and papers to travel to the States. Another scenario would have been that someone looking very similar to him, someone almost identical in appearance, could have taken his place, like a Soviet illegal. Alternatively, the US intelligence services would have looked suspiciously on Oswald upon his return to the States, wondering if he had been turned into a Soviet spy coming home on behalf of his new Soviet handlers.

Regardless of the truth, Oswald—wittingly or unwittingly—had created a “Legend” for himself that could be used any time against various targets. Most importantly though, the US intelligence services would suspect that Oswald was probably impersonated by someone else for sinister purposes. This was to be the first time but it would not be the last.

How did Oswald find out about this obscure college somewhere in Switzerland? It has been suggested by various authors that Kerry Thornley, one of Oswald’s Marine friends at Santa Ana, brought it to his attention and helped him with the application.

Thornley was a New Age writer, satirist, mystic and crypto-fascist, and a native Californian who had studied at USC. He had been six months in active duty, following time in the reserves when he met Oswald at El Toro base near Santa Ana. Oswald even gave Thornley his copy of George Orwell’s 1984 to read.10 Thornley claimed that he met Oswald a week after Oswald applied to the ASC. As Greg Parker notes, it is possible that Thornley met and knew Oswald before his application to the college.11

Thornley testified to the Warren Commission:

I believe it was the First Unitarian Church in Los Angeles. I had mentioned earlier at the time I was talking to Oswald, and knew Oswald, I had been going to the First Unitarian Church in Los Angeles. This is a group of quite far to the left people politically for the most part, and mentioned in order to explain my political relationship with Oswald, at that moment, and he began to ask me questions about the First Unitarian Church and I answered, and then he realized or understood or asked what Oswald’s connection with the First Unitarian Church was and I explained to him that there was none.

We do know that Oswald had visited Los Angeles, at least to get his passport, although he may have visited the Cuban Consulate as we shall see later on.

The leader of this church was Minister Stephen Fritchman. He was a peace activist who had supported the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, had been called by the Un-American Activities Committee and had attended the World Congress for Peace in Stockholm in May 1959.12

Was there a connection between Oswald, Thornley, Fritchman and the ASC? The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) included in its assassination files about Oswald a sixty-page report on Fritchman. Additionally, the Warren Commission and the FBI were interested and curious about Oswald and Thornley’s Unitarian Church link while trying to explain how Oswald obtained information about the ASC.13

Evica believed that “Oswald’s mysterious source of information about Albert Schweitzer College could be explained by Thornley’s attendance at Fritchman’s First Unitarian Church in Los Angeles … the pastor may have possessed detailed information about the college and copies of the college’s registration forms. When Oswald visited LA, he could have picked up the materials at the church … Alternatively, Thornley … could have picked them up and passed them on to Oswald.”14

The Liberal Religious Youth (LRY) was a group that cooperated with the ASC. Reverend Leon Hopper, one of its members, said to Evica in March 2003 that “student recruitment was almost always through personal contacts … also confirmed that Stephen Fritchman could have been an information source … Finally Hopper confirmed that the LRY concentrated on the summer sessions of ASC, reaching prospective students through personal contacts.”15

The ASC was located in the small village of Churwalden, Switzerland, and there was something peculiar about it since it did not offer degrees. Even the Swiss authorities did not know it existed until the early 60s when there were accusations of a narcotics and fraud scandal involving the college. Soon the college was in debt, and closed only after an unknown entity from Liechtenstein paid off all of its debts.16 The peculiarities did not end there. Since the village was very small, it did not have a hospital, a library, a fire department or a police station. The village was many miles away from the nearest town of Chur, and one had to drive through poor roads and across mountains to reach the village.

The college was housed in the village’s larger building, the hotel Krone with thirty rooms capacity.17 It opened in 1954, and the first list of students available revealed there were no Swiss students at all, which served to keep it unknown to the Swiss Government.18

The ASC was created by the International Association for Religious Freedom (IARF). According to Richard Boeke, first President of the American chapter of IARF, it was the crown jewel of all the IARF’s associate religious centers and had initially been “good for Liberal Swiss Protestants.”19 The IARF originated in 1900 as the International Council of Unitarian and Other Liberal Religious Thinkers and workers on May 25, in Boston. The stated aim was “opening communications with those in all lands who are striving to unite Pure Religion and Perfect Liberty, and to increase fellowship and cooperation among them.”20 It would include religions like the Unitarian, Buddhist, Humanist, Muslim, Scientology and Theosophy.21

The ASC was operated by the Albert Schweitzer College Association—a non- profit organization with its legal HQs in the village of Churwalden—and the Unitarian “American Friends of Albert Schweitzer College” which was also a non-profit organization. The “American Friends of Albert Schweitzer College” had its offices in Boston. It was incorporated in New York in 1953 with the purpose of receiving tax-deductible contributions from United States citizens and corporations.22 Its directors were John H. Lathrop (Brooklyn, NY), John Ritzenthaler (Montclair, NJ), and Percival F. Brundage (Montclair, NJ).23 Brundage was the most interesting individual out of the three directors, a true member of the “Power Elite”, with government and intelligence connections.

Who was Percival F. Brundage? Brundage was the son of a Unitarian Minister who graduated cum laude from Harvard University in 1914 and afterwards became a successful accountant, probably one of the best of his era. In 1916 he worked as a civilian in the Material Accounting Section of the War Department’s Quartermaster Depot Office in New York which involved record keeping of sensitive military procurement operations.24

He became a senior partner in the accounting firm, Price-Waterhouse. He was director, and then president of the Federal Union that argued for the federation of the Atlantic democracies.25

Brundage had a significant connection to the Unitarian Church and the ASC. He was a major Unitarian Church officer from 1942-1954 when the Unitarian Church was cooperating with, first, the OSS, and later the CIA.26 He was also president of the International Association for Religious Freedom (IARF) from 1952-1955 and president of the American Friends of Albert Schweitzer College from 1953-1958. Most importantly, Brundage became the most prominent member of the Bureau of Budget (BOB) during the Eisenhower presidency. He was its deputy director from 1954-1956, its president from 1956-1958 and he served it as consultant until 1960.27

As the head of the BOB, Brundage was controlling the United States budget, and from that privileged position he would be familiar with the Pentagon’s and CIA’s secret black budgets but without ever exposing or surveying them. It seemed that Brundage would turn a blind eye and let them do their secret work without the government ever bothering them.

One of Brundage’s closest friends was a fellow Unitarian, James R. Killian Jr., president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).28 Killian was appointed the chairmanship of president Eisenhower’s Technological Capabilities Panel in 1953 to measure the nation’s security and intelligence capabilities and also to study both military and intelligence applications of high-flight reconnaissance.29 Killian appointed Edward H. Land, inventor of the Polaroid land camera, as chief of the top-secret intelligence section of the Air Force Technological Capabilities Panel that helped create high-flight reconnaissance, like the U-2 and satellites. Land was also responsible for the CIA receiving the responsibility for the U-2 program.30 In 1957 he was appointed by Eisenhower as Special Assistant for Science and Technology, and in 1956 became Eisenhower’s chairman of the US Board of Consultants on Foreign Intelligence Activities, reporting to the president the activities of the intelligence community, especially the CIA.31 This board was supported by Brundage’s BOB. Later, Killian advised Eisenhower that the Air Force was incapable of developing photographic reconnaissance satellites. This allowed him to turn over that assignment to the CIA, which led to the CORONA satellite program32 that was discussed in part 1.

Killian, Brundage and Nelson Rockefeller were the three men who transformed the national Committee of Aeronautics (NACA) into the civilian agency responsible for the US space program. It was renamed NASA. Brundage was responsible as the head of BOB for drafting the congressional legislation for the creation of NASA.33 Brundage was also involved in Operation Vanguard, which was “intended to establish freedom of space, and the right to overfly foreign territory for future intelligence satellites.”34

In 1960, Brundage and one of his associates, E. Perkins McGuire, were asked to hold the majority of a new airline stock “in name only.”35 They both agreed to act on behalf of the CIA. The airline was none other than Southern Air Transport, which was used in paramilitary missions in the Congo, the Caribbean and Indochina. The Newsweek issue of May 19, 1975 linked Percival Brundage to Southern Air Transport, Double-Check Corp, the Robert Mullen Company and Zenith Technical Enterprises. The Double-Check Corp was a CIA front that was used to recruit pilots for covert missions against Cuba; Robert Mullen’s advertising company provided cover for CIA personnel abroad; and Zenith Technical Enterprises was the front that provided cover for CIA’s JM/WAVE station in Miami.36

Southern Air Transport was created by Paul Helliwell, an originator of the CIA’s off-the-books accounting system and nicknamed Mister Black Bag. Helliwell was a member of the OSS and later of the CIA in the Far East; he was one of the most prominent members of the China Lobby. His mission was to assist Chang Kai-Shek and his Kuomintang (KMT) army in Burma to invade China. This army managed and controlled the opium traffic in the region. Helliwell created two front companies to help KMT to carry out its war and the drug trade. One was Sea Supply in Bangkok and the other was CAT Inc., later Air America in Taiwan.37 Helliwell had organized a drug trafficking network supported by banks to launder CIA’s drug profits in the Far East.

Richard Bissell brought Helliwell back to the States to plan a similar network of front companies and banks to finance the Agency’s war against Castro. Similar to Sea Supply and Air America, he created Southern Air Transport in Miami to fly over drugs and guns to support not only the war on Cuba but also in Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia.

In his book Prelude to Terror, Joseph Trento claimed that Helliwell’s main objective was to cement the CIA’s relationship with organized crime.38 Meyer Lansky and Santo Trafficante were both planning to invest in the Far East by bringing heroin back to the States. Helliwell established banks in Florida and became the owner of the Bank of Perrine in Key West, “a two-time laundromat for the Lansky mob and the CIA”, and its sister Bank of Cutler Ridge.39 Lansky would deposit money into the Bank of Perrine, reaching the US from the Bank of World Commerce in the Bahamas. Lansky also used the small Miami National Bank, where Helliwell was a legal counsel, to launder money from abroad and from his Las Vegas casinos.40 Peter Scott claimed that Helliwell worked with E. Howard Hunt, Mitch WerBell and Lucien Conein on developing relationships with drug dealing Cuban veterans of the Bay of Pigs invasion, and became CIA paymaster for JM/WAVE to finance Chief of Station Ted Shackley’s operations against Cuba.41 Sergio Arcacha-Smith, one of the New Orleans Cubans who knew Oswald and E. Howard Hunt, was involved in the lucrative business of contraband transportation from Florida to Texas, specializing in drugs, guns, and even prostitution.42

In other words, Percival Brundage was no ordinary citizen. His BOB activities with the U-2, the satellite programs, the Pentagon, the CIA, and especially his involvement with the ASC, linked him indirectly to Lee Harvey Oswald. The young Marine had applied to the ASC to study in Switzerland and his defection to the Soviet Union was unwittingly connected to the U-2 and CORONA projects that brought an end to the Paris Peace talks and prolonged the Cold War. When Percival Brundage became a part of Southern Air Transport, he entered a nexus of CIA, Mafia, drug trafficking, money laundering and anti-Castro Cubans, one which later met and manipulated Oswald, and some of whose members were very likely involved in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It is also very plausible that the assassination was financed by this drug trafficking and banking network instead of oil-men money as many believe.

Was Oswald a communist sympathizer from his early days, like the Warren Commission concluded? Had he been in contact with the Cuban Consulate in Los Angeles?

Corporal Nelson Delgado was a Puerto Rican stationed at El Toro Marine Corps base who became close friends with Oswald. They were both loners but they had a common interest, and that was Cuba. Both admired Castro because he seemed to be a freedom fighter against Batista’s tyranny who could bring democracy to Cuba. They were dreaming that they could go there and become officers and free other islands like the Dominican Republic. Delgado could speak Spanish and Oswald would configure his ideas about how to run a government—so they kept dreaming.

Things got a little strange when Oswald became serious about it and was trying to find ways to actually go to Cuba.43

When interviewed by the Warren Commission, Delgado said he advised Oswald to go and see the Cubans at the Cuban Consulate in Los Angeles. Wesley Liebeler, a Warren Commission lawyer, took Delgado’s testimony and stretched it by the ears to make it look like Oswald was in contact with the Cubans all along. According to Australian researcher Greg Parker, “Liebeler, adroitly took a bunch of assumptions and leaps of logic by Delgado and magically recast them as proven fact leading to an inevitable conclusion.”44

According to Delgado:45

Based on the above, Liebeler instructed Delgado to “tell me all that you can remember about Oswald’s contact with the Cuban Consulate.”46

Delgado also noted that after Oswald allegedly visited the Cuban Consulate, he started receiving mail, pamphlets and a newspaper. Naturally, he assumed that they must have come from the Cuban Consulate and concluded the newspaper was communist, since it was written in Russian. He asked Oswald if it was a communist newspaper and he replied that it was White Russian and not communist. Still, Delgado, who did not know what White Russian meant, concluded it was a Soviet newspaper.47

One of the pamphlets had a big impressive seal that looked like a Mexican eagle with different colors, red and white and a Latin script with the word “United” included. Parker believes that Delgado probably was describing the logo of a Russian Solidarist movement known as NTS (HTC in Russian), standing for Narodnyi Trudovoy Soyuz (National Labor Union) in English.48 Below we can see the NTS logo with something that looks like an eagle, and the colors white, blue and red in the background.

|

| NTS logo |

More information about NTS can be found in Stephen Dorill’s book MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. According to Dorill, NTS was founded in Belgrade in July 1930 by Prince Anton Turkul and Claudius Voss, and it stood for National Labor Council. Prince Turkul was a member of the White Russian Armed Services Union (ROVS) and its purpose was to restore Tsarist Russia. Voss was the head of ROVS in the Balkans and “a British intelligence agent and ran ROVS’ MI6-friendly counter-intelligence service, the Inner Line, that sponsored NTS.”49

Dorill also revealed that “the Russian émigré organizations were working overtime through bodies such as the NTS … to undermine the Soviet regime and to form a provisional government when the Soviets collapsed.”50 Dorill described NTS’ origins: “Initially a left-of-centre grouping, NTS soon moved to the right, promoting an anti-Marxist philosophy of national labor solidarity, based on three components: idealism, nationalism, and activism. It enjoyed the support of several European intelligence services, in particular MI6, and also attracted substantial funds from businessmen with interests in pre-revolutionary Russia, including Sir Henry Deterding, chair of Royal Dutch Shell, and the armaments manufacturer, Sir Basil Zaharooff.”51

If Parker is right, and the pamphlets that Oswald was receiving were not communist but on the contrary from the NTS, then we can conclude that Oswald was in contact with fervent anti-communist White Russians. In that context, then, his trip to the Soviet Union could be viewed from a different perspective.

Oswald received help to apply to the ASC and travel to the Soviet Union, most likely from a nexus that involved the CIA and anti-communist organizations with relations to the military-industrial complex. When Oswald applied to the ASC, he listed his favorite authors as Jack London, Charles Darwin and Norman V. Peale.52 Jack London was one of the founders of The League for Industrial Democracy (LID), whose purpose was to extend democracy in all aspects of American life. During the Cold War, it was renamed the Student League for Industrial Democracy (SLID), had close ties to the CIA and had become anti-communist.53 Jack London was a supporter of social Darwinism, eugenics, Nietzschean philosophy and Jungian psychology.54

Darwin was a Unitarian and author of “Origins of the Species.” His cousin Francis Galton studied heredity based on Darwin’s work and as a result he coined the word “eugenics”, the theory that selective breeding will improve the human race.55

Norman Vincent Peale was a minister of the Lutheran church, politically conservative, and opposed the liberal and Catholic Jack Kennedy. He believed that as a Roman Catholic President Kennedy would align with the Vatican with respect to US foreign policy.56 He headed a group, which included Billy Graham, that held a secret meeting to discuss how to derail Kennedy’s election bid.57 Some of Peale’s associates were supporters of lynching, while others were against the Eisenhower-Khrushchev Paris peace summit.58 He was also friends with the conservatives Nixon and Hoover.59

If Oswald was, as he is alleged to be, a communist sympathizer, these interests and connections to the reactionary and elitist Right come as a surprise. Indeed, they would seem to indicate, on the contrary, that Oswald was actually instructed and guided by people who were anti-communist and probably tied to the CIA.

Even Hans Casparis, the founder of the ASC, had probable CIA connections. Casparis claimed that he had graduated from three universities, studied at a fourth and was a full-time lecturer in German and philosophy at the ASC. There were no specific degrees listed on the ASC brochure presenting Casparis, while five other lecturers held doctorates, and another one, along with Casparis’ wife, Therese, held a BA.60 Casparis claimed that he was a lecturer in education at the School of European Studies at the University of Zürich, but when Professor Evica asked the university to confirm it, they replied that Casparis had never lectured there.61 Records indicated that Casparis had studied at the University of Chicago (1946-1947), and the University of Tübingen (1922-1923), but never received degrees from either of the two.62

The same ASC brochure said that Therese Casparis, his wife, had a BA degree in education from the University of London. However, the university’s assistant archivist revealed that Therese had received a second-class honors degree in German and then enrolled to take a teacher’s diploma, but she left without taking an exam, so she never received a BA in education from that university. Therese gave birth to five children from 1934 to 1948, but Evica could not find any college in Europe or England which awarded a degree to Hans or Therese. 63 It was a mystery how they were able to raise five children without any higher degrees, yet were able to attract support from important Unitarians to establish a college in an unknown village somewhere in Switzerland. It is likely that Hans and Therese were employed by the CIA to infiltrate this liberal college. If we consider Evica’s findings that Allen Dulles had used religious organizations like the Unitarians to create humanitarian front organizations in order to conceal OSS and later CIA covert operations to destabilize Eastern Europe, South America and South East Asia, we can conclude, or strongly suspect, that ASC was such a front cover.

When Oswald was arrested in New Orleans during the summer of 1963, he was asked by police officer Frank Martello how he came to be a member of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC). To that he replied that “he became interested in that committee in Los Angeles … in 1958 while in the US Marine Corps.”64 Although he gave the wrong information, since the FPCC was established in April of 1960, he simultaneously revealed that when he was visiting Los Angeles he most likely met the pro-Castro people that had organized the FPCC’s Los Angeles branch at the first Unitarian Church of Robert Fritchman.65

In 1963, Richard Case Nagell was investigating the FPCC branch in Los Angeles, leftists and Unitarians. In his notebook were written the names of: Helen Travis of the FPCC, Dorothy Healy of the Communist Party, USA, Reverend Robert Fritchman of the First Unitarian Church, and the officials of the Medical Aid for Cuba Committee.66

Is it possible that all along Oswald was being groomed to penetrate the FPCC?

A 1976 CIA internal memo stated, “In the late 1950’s, Hemming and Sturgis, both former US Marines, joined Fidel Castro in Cuba but returned shortly thereafter, claiming disillusionment with the Castro cause.”67 Delgado testified that a mysterious man visited Oswald at the gate of El Toro base. He had assumed that he was someone from the Los Angeles Cuban Consulate. However, Gerry Patrick Hemming revealed later on that he had met Oswald in the Cuban Consulate in Los Angeles and went to confront Oswald at the gate of El Toro base.

There are indications that this actually happened. A CIA memo stated that “Henning (Hemming) returned to California in October 1958 … he left for Cuba by air via Miami on or about 18 February 1959, arriving in Havana on 19 February 1959. He claimed to have contacted the officials in the Cuban consul’s office in Los Angeles prior to his departure.”68 Another CIA Security Office memo from 1977 linked Oswald to Hemming: “The Office of Security file concerning Hemming which is replete with information possibly linking Hemming and his cohorts to Oswald … ”69

Could it be possible that Oswald was being “put together” to penetrate pro-Castro organizations like the FPCC as Hemming had been associated with Castro and his allies before him?

In a 1976 article in Argosy, it was stated that, “Hemming maintains that the US should utilize a number of Special Forces types … who could penetrate revolutionary movements at an early stage, gain influential positions, and then channel them into more favorable areas.70 It was during that period late 1959, early 1960, when Oswald defected to the Soviet Union that the US Government—and Hemming—had realized that Castro was pro-Soviet. He was a Communist who could pose a threat to the US interests and an option would have been to have him “eliminated.”71

It is likely that Oswald was sent to the Soviet Union to build up a “Legend” as a pro-communist, pro-Soviet sympathizer. One who appeared to have provided secret information to help the Soviets shoot down the U-2—even if he did not—and then return home as a Soviet spy, or as someone who had helped create a Soviet illegal. His mission would have been to infiltrate leftist, subversive and pro-Castro organizations while pretending to be on their side.

In Part 3, we examine the Oswald legend in Dallas, New Orleans and Mexico City.

1 John Newman, Oswald and the CIA, Skyhorse Publishing Inc. 1995, p. 92.

2 Newman, p. 92.

3 Newman, p. 92.

4 George Michael Evica, A Certain Arrogance, Trine Day 2011, p. 21.

5 Evica, p. 22.

6 Evica, pp. 25-26.

7 Evica, pp. 68-69.

8 Evica, p. 59.

9 Newman, p. 423.

10 Greg Parker, Lee Harvey’s Oswald Cold War, vols. 1 & 2, New Disease Press, 2015, p. 283.

11 Parker, p. 285.

12 Parker, p. 287.

13 Evica, p. 35.

14 Evica, pp. 35-36.

15 Evica, p. 87.

16 John Armstrong, Harvey and Lee, Quasar Press, 2003, p. 227.

17 Armstrong, pp. 227-228.

18 Armstrong, p. 228.

19 Evica, p. 83

20 Parker, pp. 287-288.

21 Parker, p. 288.

22 Evica, p. 86.

23 Armstrong, p .228.

24 Evica, p. 237.

25 Evica, p. 238.

26 Evica, p. 276.

27 Evica, p. 238.

28 Evica, p. 245.

29 Evica, p. 247.

30 Evica, p. 248.

31 Evica, p. 248.

32 Evica, p. 250.

33 Evica, pp. 255-256.

34 Parker, p. 290.

35 Evica, p. 272.

36 Armstrong, p. 229.

37 Peter Dale Scott, The American Deep State, Rowman & Littlefield, 2015, p. 126.

38 http://spartacus-educational.com/JFKhelliwell.htm.

39 http://www.globalresearch.ca/deep-events-and-the-cia-s-global-drug-connection/10095.

40 http://www.globalresearch.ca/deep-events-and-the-cia-s-global-drug-connection/10095.

41 http://spartacus-educational.com/JFKhelliwell.htm.

42 James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed, Skyhorse Publishing, 2012, p. 329.

43 Newman, pp. 96-97.

44 Parker, pp. 280-281.

45 Parker, p. 281

46 Parker, p. 281.

47 Parker, p. 282.

48 Parker, p. 282.

49 Stephen Dorril, MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service, Harper Collins, 2002, p. 405.

50 Dorril, p. 405.

51 Dorril, p. 406.

52 Parker, p. 296.

53 Parker, p. 297.

54 Parker, p. 297.

55 Parker, p. 297.

56 Parker, pp. 297-298.

57 Parker, p. 300.

58 Parker, p. 301.

59 Parker, p. 302.

60 Evica, pp. 95-96.

61 Evica, p. 96.

62 Evica, p. 96.

63 Evica, pp. 100-101.

64 Evica, p. 36.

65 Evica, p. 36.

66 Dick Russell, The Man Who Knew too Much, Carroll & Graf, p. 226.

67 Newman, p. 101.

68 Newman, p. 102.

69 Newman, p. 103.

70 Newman, p. 104.

71 Newman, pp. 115-121.

The following is a transcript of an interview at the 1983 USC conference entitled “Vietnam Reconsidered”. Clete Roberts was a local newscaster in Los Angeles. This interview occurred a year before his death. The cameraman for the interview was the Oscar-winning activist cinematographer Haskell Wexler. This interview is important because it took place almost ten years before the publication of John Newman’s book, JFK and Vietnam. But it shows Kennedy’s attitude toward that conflict was just as Newman depicted it.

Clete Roberts, correspondent

Ian Masters, Producer, Director

Michael Rose, Producer

Haskell Wexler, Camera (along with others)

Susan Cope, Sound

Eric Vollmer, Coordinator

Anne Vermillion, Coordinator

Vietnam Reconsidered Conference, USC, 1983

Clete Roberts:

Let’s see. When you were Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs what was going on in Vietnam at that particular time?

Roger Hilsman:

Well, I started off with the Kennedy administration as being Assistant Secretary for Research and Intelligence, and then when Averell Harriman was promoted to be Under Secretary, I became Assistant Secretary for Far Eastern Affairs. So the last 14, 15 months of the Kennedy administration, I was head of the Far East. What was going on was that Kennedy had followed the Eisenhower policy of giving aid and advisors to the South Vietnamese, but Kennedy was absolutely opposed to bombing North Vietnam or sending American troops. Kennedy was killed, I stayed on and I pursued Kennedy’s policy and Mr. Johnson, President Johnson disagreed. He and I quarreled about this, he wanted to bomb the North and send American troops in, I was opposed to it. As it happened, I resigned, but I beat him to the punch by about two hours. I think he would have fired me if I hadn’t resigned. So that gives you the basic picture.

Roberts:

Well, I suppose this question ought to be asked. Who got us into the Vietnam War?

Roger Hilsman:

Well, you can … If you start at the very beginning, in the middle of World War Two, OSS, which I was a member of, had liaison officers with Ho Chi Minh and we were helping Ho Chi Minh. Then as the Cold War heated up, or the Cold War got involved, increasingly Vietnam got involved with the Cold War. And during the Truman administration, we began to help the French and so on. In the Kennedy administration, Kennedy started off something of a hawk, but as things progressed, he became convinced of two things. One is that it was not a world communist thrust, that it was a nationalist Vietnamese anti-colonialst thing, and that therefore we should help the South Vietnamese with aid and maybe advisors, but that we should never get American troops involved.

When Kennedy was killed the balance of power shifted to a group of people, Lyndon Johnson, Walt Rostow, Dean Rusk, Bob McNamara, who saw it not as an anti-colonialist nationalist movement, but as a world communist movement, you see. And they, for ideological reasons or, I would argue, for a misunderstanding of the nature of the struggle, made it an American war. So is that a capsule version?

Roberts:

You spoke a moment ago of being at odds, at loggerheads, with President Johnson, but what does a State department official, an official in the position you were in, what do you do when you get to loggerheads with the administration or with a policy you can’t live with? Do you just quit or do you take it to the press, to the public? Now you could have done it, but you’re arguing with the President of the United States, I understand that.

Roger Hilsman:

That’s right. Well, I want to be responsive to your question and how to do so. Averell Harriman was Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs and I was Assistant Secretary for Research and Intelligence, and Kennedy promoted him to be Under Secretary of State and promoted me to Averell’s job. And I remember a press man said to me that I think this is a wonderful appointment. And I said, “Well, why? Do you admire us that much?” And he said, “No. Both you and Averell are free men. Averell is a free man because he’s got $500 million. You’re a free man because you’ve got a PhD in International Politics and you can always go back to teaching at a university.” So he said, “I am confident that you guys will quit if push comes to shove, and you’ll do so publicly.” And I think this is true.

For example, one of the best Foreign Service officers, I’ve never said this publicly, but I’m willing to do so now, one of the best Foreign Service officers in my day was Marshall Green in the Far East. He was Consul General at Hong Kong and I think that I can prove that I thought he was good because I brought him back to be my deputy. But some years later, in the Nixon administration he was made Assistant Secretary. I thought that was a terrible mistake.

Roberts:

Because he was a career man?

Roger Hilsman:

Because he was a career man, you see. Now when Nixon worked the rapprochement with China, the Assistant Secretary of State, Marshall Green, read about it in the newspapers. He had no alternative career. You see, if I had been Assistant Secretary at the time, or Averell Harriman, Nixon wouldn’t have dared to have done this without consulting the State department because he would know that either Averell or I would have marched out of our office, we’d have gone down to the first floor, we’d have called a press conference in front of TV, and we’d have resigned publicly with a blast. It would have cost him. Marshall Green can’t do that, a career Foreign Service can’t do that.

So I think what I’m saying is that an Assistant Secretary who is a political appointee, who is the President’s man, yes, but because he’s the President’s man, he can say to the President, “You can’t do this without consulting the experts. You can’t go off on your own, you’ve got to consult the experts. If you don’t consult the experts, I’ll blast you and I’ll blast you publicly.” And I think it’s important that people at that second level, or third level, you see the Assistant Secretary of State level, be free men, be people who are able to blast and the President has to know. You see, he stands between the experts and the President so that the President has to consult the experts or otherwise he’ll pay the price.

Roberts:

And that is done only by going to the press?

Roger Hilsman:

I think it’s true.

Roberts:

No other way?

Roger Hilsman:

There’s no other way. This is … The press are perhaps being used in this sense, but not unfairly.

Roberts:

Talking earlier with George Reedy who was Press Secretary, as you know, for President Johnson, he told us that after Johnson came into office, into Washington D.C., that he felt that he was at a loss of what to do about Vietnam. And there was a meeting …

Roger Hilsman:

That Vietnam was … That Johnson was at a loss?

Roberts:

At a loss initially in what to do about it.

Roger Hilsman:

I don’t think that’s true.

Roberts:

That he felt it … At a meeting that he attended, that he was looking, he, Johnson, was looking for signals from the Kennedy people about which way to go. And he felt that perhaps Johnson had misinterpreted what the Kennedy people were saying to him.

Roger Hilsman:

Well, George Reedy is a very old friend, I’ve known him for 25 years, I respect him a great deal, but I would have to say that George was, he was the public relations guy, so he was not involved in the substantive discussions and therefore I beg to disagree. When Johnson was Vice President, he attended a number of meetings, National Security Council meetings at which I was the Assistant Secretary. You see, I was responsible for all of Asian policy. The President made the decisions, the Secretary of State made the decisions, but I was the person who made the recommendations and who carried out their decisions. So I was in a key position.

And I would say that those meetings, George was not at those meetings, and long before the President was killed, when LBJ was Vice President, it became very clear to us that LBJ had a viewpoint, a position, that he was a hawk if you will. That he thought that, whereas Kennedy felt we should support the South Vietnamese with aid and with advisors, but that it was basically not a world communist struggle, it was not the communist bloc against America. It was a nationalist anti-colonialist movement, we should help them certainly, but we should not get any Americans killed, we should not make a war out of it. Johnson had a world ideological view of it that this was a struggle between the communist world and the West, and I think he’s been proved wrong because they won, and the world hasn’t changed that much, we’re still here, thank God. But I think that Johnson, long before Kennedy was killed, a year before, in those meetings, made it very clear that he saw it as a cataclysmic struggle between good and evil, that he saw it in ideological terms.

Johnson saw Vietnam as a struggle between the communist world and the non-communist world; whereas Kennedy saw it, I think correctly, as history will show us, as a nationalist anti-colonialist movement, which really had no effect on the survival of the United States. Johnson saw it as Armageddon, you see, and I think Johnson clearly was shown to be wrong.

Roberts:

After you left your position in the administration and you watched Vietnam, what did you think of the quality of the reporting that was coming out of there?

Roger Hilsman:

I’m moved to not answer your question just yet, but another question first. One of the things that has troubled me all my life is that, you see, Bobby Kennedy, Jack Kennedy, George Ball, me, Mike Forrestal, saw this as a nationalist anti-colonialist movement, whereas a lot of others saw it as this world shaking event where the communist world was going to dominate and dominoes and all the rest. And one of the things that has bothered me ever since, and that was the question I thought you were asking, was have you examined your soul? Was there anything that you could have done? ‘Cause you see, with hindsight it turns out we were right. Is there anything I could have done to have stopped this that I didn’t do? If I had been successful, there would be 55,000 Americans alive that are not alive, and about a million Vietnamese. And that one I have struggled over. I can’t think of what I could have done. It was … I tried, I tried endlessly to try to convince Johnson that this was not Armageddon, this was not something that we should spend all these American lives on, and I failed. I don’t know what I would have done otherwise.

Roger Hilsman:

But now to go to your question, could the press have done anything differently?

Roberts:

My question, yes. And what they did do, what do you think of it?

Roger Hilsman:

Well, to tell you the honest to God truth, I don’t think any of us did a good job. I mean, I think there were a few of us in government who saw it as history shows it was. It was not ordered by Moscow or Peking. It was not Armageddon. There were some of us who saw it that way. We failed in convincing Lyndon. Now Jack Kennedy saw it that way, we didn’t need to convince him, he convinced us. He deserves the most credit. So I think that some of us saw it that way, there were a few in the press, but basically I think that it can be said equally of the press, the policy makers, the foreign service, the CIA, anybody you name, that they failed to understand what was going on.

The press, in my judgment, never addressed themselves to the question of what is the nature of this struggle? You see, they assumed that it was a world communist movement. It wasn’t, it was a nationalist anti-colonialist movement. The press got themselves involved in the day by day business. What happened yesterday? How many Americans were killed? It was the Ernie Pyle sort of thing, you see. They accepted the overall rationale of the war, the press did, without question, and they concentrated on the Ernie Pyle level of the grunt, of the soldier. And I think they failed the American people, I think they failed the American policy makers, they didn’t ask the right questions. They didn’t ask the fundamental questions. I think that’s true of the press, I think that’s true of the policy makers. I’m not focusing on the press, I don’t think the press caused the war or the press is responsible. I just think the press, like the CIA and the foreign service and the policy makers, failed to ask the right questions. I can understand why the press did because they’ve got to make the next deadline, they’ve got to make the next thing. But there’s a tendency in the press to hype things, to push it up.

And by the way, the most severe critics of the press are the press. For example, go to the Iran hostage situation. We now know that the militants who seized the embassy didn’t intend to hold it for more than 24 hours. They held it for 444 days. The reason they held it was because the press hyped it, and they got world publicity that they never dreamed of. And Scotty Reston is the man who is the most critical of this. As he says, it was the sonorous toning of the days on the evening news, “This is the 344th day of the captivity of the hostages.” As my … As Scotty Reston, I’m quoting Scotty Reston. And who was saying this? It was the Ayatollah Cronkite, you see. And there’s a real reason to believe that those hostages stayed 442 days more than they should have because guys like Cronkite hyped it. I think this is a fair criticism.

So what I’m saying is that I think we’re all culpable. We all failed to analyze Vietnam correctly. I think the press has a peculiar guilt in that they hyped it, they blew it up.

This interview from 1969 contains, among other things, two very important pieces of information. On page 7, Hilsman says Bobby Kennedy wanted to negotiate out of Vietnam in 1963. On page 21, he states JFK was thinking of recognizing Red China in 1961.

(Click here if your browser is having trouble loading the above.)

As more than one commentator has observed, generally speaking, the Right has so much power in America that it does not have to worry about things like accuracy and morality. A good example was the journalistic trumpeting about the false charge that Iraq had Weapons of Mass Destruction. After all, people do not go to conservative martinets like Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity for facts and honesty in reporting. Usually it’s the left-of-center writers and reporters who are relied upon for such things. For, as Michael Parenti once noted, reality tends to be radical. Which is the reason that it sometimes has to be propagandized. Or else how does one provoke something as stupid as the 2003 American invasion of Iraq? Those on the Left insisted there was no reliable evidence for that invasion, while the MSM pretty much accepted the (ersatz) words of Colin Powell at the United Nations.

As more than one commentator has observed, generally speaking, the Right has so much power in America that it does not have to worry about things like accuracy and morality. A good example was the journalistic trumpeting about the false charge that Iraq had Weapons of Mass Destruction. After all, people do not go to conservative martinets like Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity for facts and honesty in reporting. Usually it’s the left-of-center writers and reporters who are relied upon for such things. For, as Michael Parenti once noted, reality tends to be radical. Which is the reason that it sometimes has to be propagandized. Or else how does one provoke something as stupid as the 2003 American invasion of Iraq? Those on the Left insisted there was no reliable evidence for that invasion, while the MSM pretty much accepted the (ersatz) words of Colin Powell at the United Nations.

But what happens when the Left abandons its concern for such things as accuracy, morality and fact-based writing? What does one call such reporting then? Does it then not become—for whatever reason—another form of propaganda?

The above reflection was instigated by the comments of a couple of the former founders of Counterpunch magazine, namely, Jeffrey St. Clair and Ken Silverstein.

Counterpunch was started by Silverstein back in 1994. It was then based in Washington D. C. Silverstein was later joined by St. Clair and Alexander Cockburn. At this point, in 1996, Silverstein left and Cockburn and St. Clair became the co-editors. Silverstein stayed on as a regular contributor. The magazine’s headquarters now shifted to northern California.

At times, Counterpunch does good work. This writer used some of its work about the Hollywood film industry for the The JFK Assassination: The Evidence Today. But owing to the influence of the late Alexander Cockburn, when it comes to anything dealing with the Kennedys, they begin to abuse the profession. That is, the guidelines of accuracy, morality and fact-based reporting go out the window. Counterpunch becomes the left-wing version of Fox News.

This is clearly a recurrent syndrome for that journal. About three months ago, I reported on their last attack on JFK. About three months prior to that, I answered the falsities in another article, this time by a man named Matt Stevenson. In that piece, Stevenson actually tried to say that President Kennedy’s withdrawal plan for Vietnam was just “speculation”. Stevenson then said that President Johnson’s colossal escalation in Indochina was merely a continuation of Kennedy’s policies there; or as he wrote, Johnson was “singing from Kennedy’s hymnal together with his choir.” As I noted in that article, the declassified records on this issue show that this is utter nonsense. And we have the evidence now in Johnson’s own words—on tape.

So what makes Counterpunch, an otherwise respectable journal, debase itself on this issue? As noted above, it is most likely the influence of the late co-editor Alexander Cockburn. As most of us know, when Oliver Stone’s film JFK came out in late 1991, the Establishment went completely batty. This included what I consider to be the Left Establishment, i.e., Noam Chomsky at Z Magazine and Cockburn at The Nation. The Cockburn/Chomsky axis reacted to the film pretty much as the MSM did. The Dynamic Duo wrote that the central tenets of Stone’s film were wrong: Kennedy was not withdrawing from Indochina at the time of his assassination; JFK was not killed as a result of any upper level plot; and the Warren Commission was correct in its verdict about Oswald acting alone. For the last, Cockburn brought former Warren Commission counsel Wesley Liebeler onto the pages of The Nation. As if he was being interviewed by Tom Brokaw for NBC, Liebeler was allowed to pontificate on the fascinating flight path of CE 399, that is the Magic Bullet, as well as on how Oswald got off three shots in six seconds with a manually operated bolt-action rifle, two of them being direct hits. When an allegedly muckraking journalist softballs an attorney who later became a member of the Charles Koch funded George Mason School of Law, something is bonkers someplace (see NY Times, May 5, 2018, “What Charles Koch and other donors to George Mason got for their Money”).

What made that spectacle even worse was the fact that Cockburn had previously co-written an essay on the Robert Kennedy assassination. That piece was penned with RFK investigator Betsy Langman. It ran in the January 1975 issue of Harper’s. The article carefully laid out the problems with the evidence in the RFK assassination and how those problems tended to exonerate the convicted killer, Sirhan Sirhan. But now, in 1991-92, Cockburn gave his previous essay the back of his hand. He now wrote that Bobby Kennedy had turned his head, and this is how Sirhan, standing in front of RFK, shot him from behind in the back of the skull.

In typical MSM manner, Cockburn never commented on the following:

As the reader can see, by this time, Cockburn had joined up with his friend Chomsky—who had once harbored doubts about the JFK case. They had now both learned that discretion was the better part of valor in the murders of the Kennedys. After all, look what happened to Oliver Stone. Both men now joyfully threw overboard the Left’s shibboleths about accuracy and morality. I mean, what kind of morality is it to give safe harbor to someone like Wesley Liebeler?

It would have been one thing to have just ignored the issue. After all, if one did not think President Kennedy’s assassination was important, all right, just let it pass by. But Cockburn and Chomsky deliberately went out of their way to attack and ridicule anyone who thought differently. And they did this on numerous occasions. Since Cockburn wrote regularly for The Nation, and Chomsky was widely distributed by Pacifica Radio and Z Magazine, many on the Left were exposed to their false assumptions and smears. And that impact persists until this day.

In the August 10th issue of Counterpunch, St. Clair has a kind of round-up column that he labels, “Roaming Charges: The Grifter’s Lament”. In that string of paragraph-long notices about current events, the reader finds the following:

“Barack Obama is about to be presented with the Robert F. Kennedy Award for Human Rights. RFK, the red-baiting, anti-communist zealot who desperately wanted to assassinate Fidel? Sounds about right for the President of Drones.”

This is an excellent and made-to-order example of what I mean about the Left losing its moorings on the cases of John and Robert Kennedy. As more than one commentator has noted, both of these charges about Robert Kennedy are simply false. But St. Clair decided that he was not going to do any research. In order to stay the Cockburn/Chomsky course, he would just play the mindless stooge for them.

As William Davy noted in his fine talk at VMI University last year, the declassified version of the CIA’s Inspector General Report about the CIA/Mafia plots to kill Castro admits that the Agency had no presidential approval for enacting those attempts to kill Castro. In those pages, it is easy to see this is especially clear with regard to Attorney General Robert Kennedy, since the CIA sent two men to brief him on the plots when J. Edgar Hoover found out about them in 1962. The obvious question is: Why did Kennedy have to be briefed if he had approved them? The answer is that he had not—that is why the CIA had to tell him about them. But even more egregiously, the Agency briefers told RFK that the plots had been terminated when in reality they had not been. Again, why would they lie if they did not have to?

As the reader can see from the link above, this document has been declassified for a number of years. It is available on the web in more than one place. If St. Clair had any qualms about not being a dupe or, on the other hand, if he had thought, “Maybe I shouldn’t smear a dead man without checking the record?”, he could have easily consulted the adduced facts in the case without doing very much work at all. He chose not to.

But it’s actually even worse than that, because as part of the record that St. Clair chose to ignore, one of the authors of that report left behind his own comments on their investigation. This man was Scott Breckinridge, who testified to the Church Committee about this issue. He stated that they simply could not find any credible evidence that the CIA plots had any kind of presidential approval. When asked who gave the approval to lie to Bobby Kennedy about the ongoing nature of the plots, Breckinridge said that this went all the way up to Richard Helms, the CIA Director at the time. (see Davy’s talk)

In other words, in this case, St. Clair is actually siding with the cover-up about these plots that was supposed to save the CIA’s skin. It kept them ongoing by concealing them from Bobby Kennedy. And then later, through his trusted flunky Sam Halpern, Helms could put out a disinformation story saying that the Kennedys knew about them. (David Talbot, Brothers, pp. 122-24) Helms knew he could get away with this since the documents revealing the actual facts were classified. But today, such is not the case. Which leaves Mr. St. Clair with no excuse, not even a fig leaf, for writing what he did about RFK. Helms and Halpern would have been smiling at their dirty work.

The other half of the smear concerns Bobby Kennedy’s service on the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. This was done at his father’s request to his personal friend Senator Joe McCarthy. McCarthy had appointed attorney Roy Cohn as the committee’s chief counsel. Kennedy violently disagreed with the way that Cohn and McCarthy ran the committee. And as anyone can see, he steered clear of their finger pointing tactics at certain targets like Annie Lee Moss and Irving Peress. The work that Kennedy did was actually praised even by the committee’s critics. This was a study of how the trade practices of American allies helped China during the Korean War, thereby increasing aid to our opponent North Korea. (Arthur Schlesinger, Robert Kennedy and His Times, pp. 104-11)

Kennedy resigned over his disagreements with Cohn after six months. He then was asked back by the Democrats on the committee when they were in a stronger position. He now became their chief counsel. He retired the Moss and Peress cases, dismissed the unfounded charges of defense plant infiltration, and furnished questions for the senators in their examination of Cohn and McCarthy. He then played a large role in writing the Democratic report, which strongly attacked both men. In fact, that report was so critical that some Democrats would not sign on to it. (Schlesinger, pp. 114-19) It constitutes the beginning of the Senate’s maneuvering to censure McCarthy. In other words, the actual record states that it was RFK who helped exculpate the victims of Cohn and McCarthy. And it was RFK who began their toboggan ride to ruin. The Democrats knew this would be the case, which is why they hired him as their chief counsel.

This information has been out there since 1978. Anyone could have availed themselves of the facts, instead of MSM malarkey. That St. Clair decided not to print the facts—for the second time—shows us how worthless his writing is on the matter. This is nothing but playing to the crowd. That, of course, is what the Right (e.g., Ann Coulter) is famous for doing.

Which brings us to the third founder of Counterpunch, Ken Silverstein. Previously, I have reviewed for this site the fascinating volume by Robert Kennedy Jr., entitled Framed. That book was about the MSM hysteria over the Michael Skakel case, a hysteria induced by Mark Fuhrman and the late Dominick Dunne. In that review I tried to show how Dunne had enlisted in the ranks of the right-wing echo chamber in order to find a way to convict a Kennedy, or any Kennedy relation, in the unsolved 1975 murder of Martha Moxley. (Michael Skakel was Kennedy’s first cousin from Ethel Kennedy’s family.) Dunne assiduously worked toward this goal for years, through a variety of flimsy and dubious methods, which I detailed in that review. Dunne then enlisted Fuhrman into the quest. He obediently did the same. Since both men had high profiles with both the MSM and the Right-wing Noise Machine, and across all platforms—radio, TV, magazines, and book publishing—they now managed to transform Michael Skakel into their prime target in the Moxley murder, despite the fact that at the time of her murder, Skakel was not considered a suspect.

Bowing to the unremitting pressure of Dunne and Fuhrman, the local Connecticut authorities then employed some rather bizarre techniques in order to indict Michael Skakel. For example, they used a one-man grand jury, rewrote the state law as to the statute of limitations, and then tried Michael as an adult even though they said he committed the crime as a youth. Throughout all of this, the MSM followed the spectacle like a herd of lemmings, even though Dunne was really not an investigative reporter (he more closely resembled an exalted gossip columnist). And, to put it mildly, Fuhrman had a somewhat checkered past as a detective. In spite of all this, not one journalist cross-checked their work. Meanwhile, the supermarket tabloids egged the spectacle on. Because of the compromising publicity and an incompetent defense attorney, in 2002 Michael Skakel was convicted.

Finally, Robert Kennedy Jr. decided this was enough bread and circuses in the Colosseum. In early 2003, he penned a long and detailed magazine essay on the case. Incredibly, this was the first public questioning of the writings of Dunne and Fuhrman in the twelve years they had been writing on the case. Kennedy’s essay made Dunne look like the aggrandized celebrity gossip columnist that he was; in some ways, it made Fuhrman look even worse.

Robert Kennedy Jr. cooperated with the series of defense attorneys who helped to air the problems with the Dunne/Fuhrman posturings. In 2016, he wrote his book on the case. That book clearly had an impact on both the public and the legal system in Connecticut. It was really the first full-scale forensic study of both the murder and the (ersatz) work of the Dunne/Fuhrman team. It made them look like the Keystone Kops—perhaps even more asinine. This evidence was so compelling that the state Supreme Court has now decided to free Skakel because his defense attorney ignored a credible alibi witness who placed him far away from the crime scene.

Returning to Counterpunch founder Ken Silverstein: When Bobby Kennedy Jr. was finishing up his book on the case, he wanted someone to review it to see if everything was in place. Through David Talbot, he asked Silverstein if he wanted to act as his researcher and offered to pay him $12,500 dollars for a month’s work.

Silverstein turned down the offer. But with typical St. Clair/Cockburn snarkiness he decided to go public. And by doing that he made himself look like an ignoramus. He said that Michael had been the boyfriend of Moxley, which was wrong. But that was not enough for Ken. He then had to add that Skakel was obviously guilty. What is so incredible about that statement is that he made it without reading the Kennedy book! Again, this is just what the so-called Left is not supposed to do.

But that still was not enough. Without reading the book, Silverstein now said that there was “a wealth of evidence demonstrating beyond a reasonable doubt that Skakel is guilty”. To show just how far Silverstein had bought into the Dunne/Fuhrman paradigm, he actually recommended for reading Dunne’s book on the case, A Season in Purgatory. Can the man be real? Dunne’s book is a novel that insinuated that John Kennedy Jr. was Moxley’s killer. With a straight face, Silverstein called the book “amazing”. What is amazing is that Silverstein could be that much of a sucker for Dunne.

But even that ludicrous display was not enough for Silverstein. He then attacked Robert Kennedy Jr. personally. How? He goes all the way over and uses a book by Jerry Oppenheimer to do so. Oppenheimer is the equivalent of, say, Randy Taraborrelli, or perhaps even David Heymann, in the field of literary biography. After all, who else would write a book entitled The Kardashians: An American Drama?

Back in 1992, when Cockburn bowed down to the Allen Dulles/John McCloy led Warren Commission and softballed Wesley Liebeler, The Progressive posed the question: Why is Alexander Cockburn shaking hands with the Devil? As the record shows, these are the kinds of people—Dunne and Oppenheimer—a writer has to jump into bed with once one discards one’s code of honor and enlists in the Cockburn/Chomsky abasement program. After all, Dulles and McCloy were two of the worst Americans of that era, and in his mad mania to trash Oliver Stone’s JFK, Cockburn ignored all the evil they had done. Silverstein and St. Clair cannot go back and say: “Well Alex was really all wrong about that film JFK. He made a mistake and we apologize for that.” No, that would be admitting too much. So instead, they take the easy way out and continue to use spurious information and cheesy New YorkPost type writers. To the point that they not only discard any standards of scholarship, but also rub noses with the worst parts of the MSM. This is how much Chomsky and Cockburn scorched the earth on this issue: up is down, Left is Right, and we don’t care who we mislead or smear.

See also this provocative article from 2012 by author Douglas Valentine.

As many of this site’s readers know, for the recently released book The JFK Assassination: The Evidence Today, this author did a lot of work on the career of actor Tom Hanks. In 1993, on the set of the film Philadelphia, Hanks met music producer Gary Goetzman. A few years after that meeting, Goetzman and Hanks decided to expand their careers into producing movies: both feature films and documentaries. They set up a company called Playtone and began to churn out products that—if one understands who Hanks is—were reflective of both the actor’s personal psyche and his view of the American zeitgeist. That view was accentuated when, in 1998, Hanks first worked with Steven Spielberg on the film Saving Private Ryan. It was while working on this film that the two met and befriended the late historian Stephen Ambrose, who was a consultant on that picture.

As I wrote in my book, Ambrose turned out to have a real weakness for a historian: He manufactured interviews. Ambrose made his name, and became an establishment darling, due to his several books about Dwight Eisenhower. This included a two volume formal biography published in 1983-84. All of these books, except the first, were published after Eisenhower’s death in 1969. It was proven, by both an Eisenhower archivist and his appointments secretary, that Ambrose made up numerous interviews with the late president, interviews which he could not have conducted. (James DiEugenio, The JFK Assassination: The Evidence Today, p. 46) Late in his career, Ambrose was also proven to be a serial plagiarist by two different studies. (See David Kirkpatrick’s article in the NY Times, January 11, 2002; also “How the Ambrose Story Developed”, History News Network, June 2002)

But the worst and most revealing issue about Ambrose’s career was his switching sides in the attacks on James Bacque’s important book, Other Losses. Bacque had done some real digging into the military archives of World War II. He had discovered that the Americans had been involved in serious war crimes against German prisoners of war, and had later tried to cover it up. Bacque sent his manuscript to Ambrose in advance of publication. Ambrose had nothing but praise for it. (DiEugenio, p. 47) In 1989, before the book was to be published abroad, Bacque visited Ambrose at his home and the two went over the book in detail. When Other Losses was published in America, Ambrose at first stood by the book, which, quite naturally, was generating controversy. But after doing a teaching engagement at the US Army War College, Ambrose reversed field. First, he organized a seminar attacking the book. Then, as he would later do with Oliver Stone’s JFK, he wrote an attack article for the New York Times. (DiEugenio, p. 47)

As Bacque noted, the book Ambrose attacked was the same one the historian had praised in private letters to the author. It was the same book Ambrose read and offered suggestions to in the confines of his home. The difference was that the information was now public, and creating controversy. Bacque’s book was accusing the American military of grievous war crimes, including thousands of deaths, and since Eisenhower was involved in these acts, the pressure was on. Ambrose was the alleged authority on both Eisenhower and his governance of the American war effort in Europe. Could America have really done what the Canadian author was saying it did? To put it simply, Ambrose buckled. Under pressure from the military and the MSM, he did triple duty. Not only did he organize the panel and write the attack editorial, he then pushed through a book based on the panel. (See Bacque’s reply to this book)

Reflecting on this professional and personal betrayal, Bacque later wrote that he could not really blame Ambrose for it all, because the American establishment does not really value accuracy in the historical record. What it really wants is a “pleasing chronicle which justifies and supports our society.” He then added that, in light of that fact, “We should not wonder when a very popular writer like Ambrose is revealed to be a liar and plagiarizer, because he has in fact given us what we demand from him above all, a pleasing myth.” (DiEugenio, p. 48)

I have prefaced this review of Playtone’s latest documentary 1968: The Year that Changed America, because it is important to keep all of this information in mind during any discussion of Hanks and his producing career. Even though he did not graduate from college, he fancies himself a historian. Thus many of his films deal with historical subjects: both his feature films and his documentaries. Yet Hanks—and also Spielberg—have set Ambrose as their role model in the field. In my view, it is this kind of intellectual sloth and lack of genuine curiosity that has helped give us films like Charlie Wilson’s War, Parkland, and The Post. These films all tried to make heroes out of people who were no such thing: U.S. representative Charlie Wilson, the Dallas Police, and in the last instance, Ben Bradlee and Kay Graham. And by doing so, these pictures have mislead the American public about important events; respectively, the origins and results of the war in Afghanistan, the assassination of President Kennedy, and the position of the Washington Post on the Vietnam War. (For details on all of these misrepresentations, elisions, and distortions see Part 3 of The JFK Assassination.)

Since he wrote so often about Eisenhower, one of Ambrose’s preoccupations was World War II. He wrote at least a dozen books on that subject. As previously mentioned, Hanks and Spielberg took a brief vignette Ambrose had uncovered for his book Band of Brothers and greatly expanded and heavily revised it into the film Saving Private Ryan. (DiEugenio, pp. 45-46) From there, Hanks and Spielberg produced the hugely budgeted mini-series Band of Brothers. This was a chronicle of a company of American soldiers fighting in the European theater until the surrender of Japan. In addition to these two dramatic presentations, Hanks has produced three documentaries on the subject of American soldiers fighting in Europe. As anyone who has seen Saving Private Ryan knows, that film is largely based on the allied landing at Normandy in 1944. Ambrose wrote extensively on that event. In fact, one of his books was titled D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. And in the films of Hanks and Spielberg, the import of that title is also conveyed: that America defeated the Third Reich.

The problem with this is quite simple: it’s not true. Any real expert on World War II will inform you that it was not America that was responsible for the defeat of Hitler. It was the Soviets. And D-Day was not the climactic battle of that war. That took place in 1942 at Stalingrad, and to a lesser extent in 1943 with the tank battle at Kursk. Both of those titanic battles took place prior to the Normandy invasion, and Hitler gambled everything on them. His invasion of Russia in 1941 consumed 80% of the Wehrmacht, over three million men. To this day, it is the largest land invasion in history. (DiEugenio, p. 454) When this giant infantry offensive was defeated at Stalingrad, Hitler tried to counter that defeat with the largest tank battle in history at Kursk. This battle ended up being more or less a draw; but it was really a loss for Hitler since he had to win. The Germans lost so many men, aircraft and tanks on the Russian front that the rest of the war was a slow retreat back to Berlin.

Due to the Cold War, the historical establishment in America largely ignored these facts. Like Ambrose, they chose to glorify and aggrandize what commanders like Eisenhower had done in Europe and, to a lesser extent, what Douglas MacArthur achieved in the Pacific. In both films and TV, Hollywood followed this paradigm. Pictures like The Longest Day, Anzio, and Battle of the Bulge were echoed by small screen productions like Combat, The Gallant Men, and Twelve O’clock High. Parents bought their children toy weapons and they played games modeled on these presentations of America crushing the Nazis.

The social and historical problem with all this one-sidedness in books, films and network television was simple. It contributed to a cultural mythology of American supremacy, both in its military might and moral cause. That pretense—of both might and right—was slowly and excruciatingly ground to pieces in the jungles of Indochina. This is an important cultural issue that Ambrose, Hanks and Spielberg were not able to deal with in any real sense. I really don’t think that they ever actually confronted it. If one can make a film so weirdly lopsided as The Post, then I think one can say that, for whatever reason, it’s just not in them. After all, Hanks is 61, and Spielberg is 71. If you don’t get it after a combined 132 years, then it is probably too late. (This reviewer did some research into both men’s lives to try and ponder the mystery of this obtuseness. For my conclusions, see DiEugenio, pp. 42-44, 405-12)

This brings us to the latest Hanks/Goetzman historical documentary for CNN. It is called 1968: The Year that Changed America. HBO is the main outlet for the Playtone historical mini-series productions, e.g., John Adams, Band of Brothers, The Pacific. Cable News Network is the main market for their historical documentaries. This includes Playtone’s profiles of four decades—The Sixties, The Seventies, The Eighties, and The Nineties, and their awful documentary The Assassination of President Kennedy. This last was broadcast during the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s murder in 2013. The two main talking heads on this program were Dan Rather and Vincent Bugliosi. One would have thought that Rather had so discredited himself on the subject that he would not appear on any such programs ever again. Playtone did not think so. Either that or Hanks was unaware of the discoveries of the late Roger Feinman. Feinman worked for CBS and exposed their unethical broadcast practices in both their 1967 and 1975 specials, in addition to their subsequent lies about them. (See Why CBS Covered Up the JFK Assassination) I would like to think Hanks unaware of all this. But after sustained exposure to his output, I am not sure it would have made any difference.

This lack of scholarly rigor is reflected in some of the talking heads employed in 1968: The Year that Changed America. There is a crossover with that recent documentary bomb, American Dynasties: The Kennedys. (See my review) So again we get writers like Pat Buchanan, Tim Naftali and Evan Thomas. But in addition, we get Rather, plus the Washington Post’s Thomas Ricks, former Nixon appointee Dwight Chapin and Hanks himself. There have been many books written about that key year of 1968, but this documentary does not utilize most of the recent releases by authors like Richard Vinen, or even Laurence O’Donnell. Instead, it relies on authors who wrote their books long ago; for example, Mark Kurlanksy, whose book was published in 2003, and Charles Kaiser, who first published his volume in 1988. Readers can draw their own conclusions about these choices.