(Disclosure: the author is a friend and colleague of Len Osanic, who befriended and worked with Fletcher Prouty in his later years. Len continues to run the Fletcher Prouty online reference site www.prouty.org)

Recent years have seen a resurgence in reputational criticism of the late Col. L Fletcher Prouty, the former Pentagon official responsible for numerous influential books and essays, and the real-life model for the fictional Mr X character in Oliver Stone’s 1991 film JFK. Curiously, these efforts – by a small but vocal faction – gathered momentum following the passing of John McAdams, a self-styled “debunker” of JFK assassination theories who had been a central source of reputational disparagement of Prouty dating back to the early 1990s.[1]The renewed efforts have added little to what had been previously articulated, but are notable for a distinctly strident tone and a smug certainty in presenting harsh conclusions which are not at all supported by the available record. By this, the new anti-Prouty crowd appear distinguished by being actually worse, or at least more irresponsible and reckless, than their late mentor.

I

A central focus for these critics has been Prouty’s 1996 appearance before a panel of ARRB staffers. While this event earned little more than a passing mention in the McAdams compendium, to contemporary debunkers it serves as the effective immolation of Prouty’s entire assassination-related oeuvre as, over the course of a long interview, he allegedly “could not substantiate any of his allegations.”

Prouty’s Appearance at the ARRB 1996

The Assassination Records Review Board was created by the US Congress in the wake of Oliver Stone’s JFK film and the resulting outcry over the continuing classification of much of the official record and subsequent investigations. The Board had the mandate to identify records and oversee the process by which they would be made public. In certain circumstances, the Board had the authority to interview persons whose input could assist with locating records or whose personal experiences might help clarify circumstances which were yet incomplete. An interview was arranged with Fletcher Prouty for September 1996, with the intention of both clarifying experiences and identifying records.

The 9/10/96 letter from Chief Counsel Jeremy Gunn read as follows: “We will ask you to recount your personal experiences from around the time of the assassination of President Kennedy, as well as whatever information you have regarding military activities and procedures in effect. I would also like you to bring with you any relevant documents or notes related to these topics, especially any contemporaneous records (such as personal correspondence, telephone notes, daily diary entries, or the like) you might have.”

A month previous to this communication, a memorandum had been distributed to Gunn from Tim Wray, a Pentagon veteran who was then running the ARRB’s Military Records Team. Wray understood a potential interview with Prouty would be assisting an effort known as the “112 Military Intelligence Project”, specifically interested in information previously published by Prouty concerning a possible “stand down” order directed to a Texas-based Military Intelligence unit related to presidential protection duties in Dallas 1963.[2]

Wray’s 8/9/96 memo on Army Intelligence in Dallas read as follows: “We should eventually interview Prouty as well, though I frankly do not expect much from this—everything about his story that we’ve been able to check out so far appears to be untrue….Its only slightly more difficult to check the factual basis for the other elements of Prouty’s story….Prouty’s assertion to the contrary notwithstanding—it appears that military collaboration with the Secret Service was in fact, extremely limited, and that there certainly were no such thing as “military presidential protection units” per se.

Wray would also later write, “Among other purposes, an important goal of this interview was to ask Prouty about three specific allegations he made in his book, “CIA etc”. These allegations were of particular significance to use because Prouty claimed they were based on his own firsthand knowledge.” (Wray Memo of 2/21/97)

That there was an identified “important goal” for the interview was not shared with Prouty in the communication from September 10, 1996. Similarly, Wray’s Military Records Team assistant Christopher Barger composed a memo the following day, September 11,1996, identifying specific “allegations” appearing in Prouty’s 1992 book JFK: The CIA, Vietnam, and the Plot to Assassinate John F Kennedy, and proposing a line of questioning marked by an innate skepticism directed to Prouty’s “personal experiences”.[3] This doubting approach to his published work was also not shared with Prouty ahead of his appearance.

The interview was conducted on September 24, 1996. According to some, referring to his performance, Prouty suffered severe damage to his reputation and the integrity of his rendering of the historic record.[4] This version of events relies on an interview “Summary”, produced by Military Records Team assistant Barger, which frames the exchange as a contentious deposition.[5] The integrity of this Summary relies on the assumption that the Team participating in this interview spoke from a position supported by the confirmed record.

If It Walks Like A Duck…

Wray wrote, about a month later:

“…we should make (Prouty’s) interview with the ARRB easily available in written form so people can see for themselves what’s behind the fluff…There’s no way we can fairly represent the interview in summary form without it looking like a hatchet job.” – (Tim Wray, ARRB Memorandum October 23, 1996.)[6]

The interview transcript was published along with the Summary so that, according to Wray, the process wouldn’t merely appear as a “hatchet job”.

The interview transcript was published along with the Summary so that, according to Wray, the process wouldn’t merely appear as a “hatchet job”.

It might seem obvious that if one cannot “fairly” describe an interview process without it appearing as a “hatchet job”, then the proposition that the process was, in fact, a hatchet job is in play. Wray, to the contrary, asserts, literally, that “the emperor has no clothes” and declares therefore the ARRB Military Records Team is “not planning to do much of (Prouty’s) laundry.”[7] Beyond the strained analogy, Wray’s memorandum establishes the Team engaged the interview as an adversarial contest, tied to their own biases and skewed to a partisan acceptance of the JFK assassination’s Official Story. In a telling example, Barger opines: “Prouty also admits that he has never read or even seen the Warren Commission Report. No reputable historian would write a criticism of a source document without having read the source document first.”[8]

Barger’s Summary begins by noting the panel’s interest in Prouty stemmed from “claims”, “theories” and “conclusions” often based on “special, firsthand knowledge that he gained through his own experiences” during his years at the Pentagon. The purpose of the interview is therefore, in part, to determine the extent to which his “various allegations or statements” were based on “personal knowledge or experience”, and, “should he disavow factual knowledge”, to determine if he is aware of other “factual data that could tend to prove or disprove his allegations.” The Summary proceeds to itemize ten supposed “allegations” Prouty had articulated or published in his work, and putting them to a test, such as locating reference in official documents or finding confirmation through the identification of other individuals. In conclusion, The Summary insists the Team “intended on hearing his story”, but found “in the face of numerous contradictions, unsupportable allegations, and assertions which we know to be incorrect, we have no choice but to conclude that there is nothing to be gained or added to the record from following up on anything he told us.”[9]

While this Summary conclusion has apparently convinced some persons that Prouty should not be taken seriously, it represents a prejudiced interpretation reliant on a concept of allegation introduced solely by the Team’s own initiative. The concept of a “hatchet job” is confirmed by the notable reliance in the Summary on this term – allegation – a word never articulated in the communications with Prouty ahead of the interview, and used sparingly during the interview itself.[10] Within the Summary, however, its prominent use is naturalized by repetition, and contemporary endorsements of the Summary’s conclusions repeat the word liberally.

Put another way, and considering the range of experiences across Prouty’s professional career, one might refer to his “observations” instead of the more obviously loaded preferred description. The difference between the two is quite sharp, particularly since the stated purpose of the interview, from the Team’s perspective, was to “prove or disprove” and “confirm or deny”:

ob·ser·va·tion |(ə)n |

a remark, statement, or comment based on something one has seen, heard, or noticed

al·le·ga·tion |noun

a claim or assertion that someone has done something illegal or wrong, typically one made without proof

The Summary of the ARRB interview framed Prouty’s personal experiences as a series of “allegations”.

The Summary of the ARRB interview framed Prouty’s personal experiences as a series of “allegations”.

There are ten separate “allegations” described in the Interview Summary, each with a “Result or Conclusion by ARRB” attached. Three “allegations” refer to content in the JFK film; one refers to Prouty’s work as a military liaison with the CIA; and six have to do with presidential protection, a field outside of his professional responsibility and of which he had no practical experience.

The first “allegation” refers to Prouty’s trip to Antarctica in November 1963, noting, in the JFK movie, this trip was portrayed as “out of the ordinary or unusual in some way.”[11] Although, in a later publication, Prouty had surmised retrospectively if there was a hidden reason to being selected for the journey, he otherwise spoke consistently, including to the ARRB panel, of the trip as routine.[12] The assumed “sinister connotations”, portrayed by the ARRB panel as an “allegation”, is in fact a dramatic embellishment attributable to the JFK screenwriters, not to Prouty – who, regardless, is described as unable “to back up the suspicions he mentioned in the excerpt from his book.”[13] The second “allegation” concerns information appearing in wire service news reports and published in a New Zealand paper approximately 5-6 hours after the shots in Dallas.[14] While the Team’s “Result or conclusion” of this minor affair doesn’t refer to an actual result or conclusion, it does suggest “Prouty’s allegation of a ‘cover story’ will be weakened”. The point missed, however, is by his presence in New Zealand Prouty was outside and apart from the common shared experience stateside on that day, dominated by the visceral shock of the initial news followed by a steady drip of information which appeared to follow a sequential logic. Outside the simulacrum, Prouty could make the obvious, and correct, observation that there had quickly appeared a great deal of information about a suspect who had yet to be even arraigned on the JFK case, and in fact wouldn’t be for another 6-7 hours.[15] Having made this first observation, it is fair for him to point out the incorrect reports of “automatic weapons fire” – as others did as well.

“Allegation” numbers three through five, and ten, concern Prouty’s information – published in his book JFK: The CIA, Vietnam and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy and in his Foreword to Mark Lane’s book Plausible Denial — regarding an apparent case of security stripping in Dallas involving a military intelligence outfit based in San Antonio.[16] Prouty had privately received information that the 112th Unit had been advised to stand down in Dallas by the Secret Service, This was referring to a Presidential protection capability within the military. According to internal memoranda, the ARRB Military Records Team was skeptical such units existed and was determined to “debunk” Prouty’s information. In the fullness of time, Prouty’s veracity regarding both the actual fact of military intelligence support for presidential protection, and the private communication he received, has been confirmed and the Team’s skepticism debunked.[17]

Allegations six and seven refer to Prouty’s knowledge of Secret Service presidential protection protocols. When mentioning these, Prouty is referring to events specific to his military career, including several days in Mexico City, 1955, with a Secret Service advance team ahead of an Eisenhower visit. Prouty’s observations from these episodes inform his published statements and his statements during the ARRB interview. He qualifies his interactions as having “logistics purposes, not to learn all about the system.” The ARRB’s Summary characterizes the “allegations” as lacking corroborative documentation. This lack included failing to answer the question: “How many Secret Service agents would you have expected to be providing coverage in Dallas?”[18] Figurative speech is also interpreted literally, such as Prouty’s reference to the Secret Service working from a long-established “book” (he is asked if he has a copy of the “book”), or his impression that the Secret Service was deficient in Dallas stated as “they weren’t there” (he is asked if he meant they literally were not there).[19] This exchange is referred in the Summary as follows: “Prouty makes the very serious charge that the Secret Service was not even on duty in Dallas on November 22, then admits he has no experience upon which to base this statement.”[20] In truth, the deficiencies of the Secret Service during the Dallas motorcade have been well-catalogued, if not by the sources who appear to have influenced the Team.

“Allegation #8” concerns whether some of Oswald’s activity during his Marine service in Asia – specifically with radar at Atsugi air base (where the U2s were based) and potentially in support of operations directed at Indonesia – could be described as part of CIA-directed programs. Although Prouty correctly describes the existence of the programs and Oswald’s proximity, the Panel jumps on his lack of specific documentation (“substantiating evidence”) as a means of dismissing the notion Oswald was involved. Even though Oswald himself specifically hinted at insider knowledge of U2 activity (at Atsugi) during his communications in Moscow related to his defection to the USSR, the Team presumes to consign this “allegation” as based merely on open-source rumors.

“Allegation #9” refers to Prouty’s identification of Ed Lansdale in one of the well-known “Tramps” photos, which is portrayed in the JFK film. The Team acknowledges that a “search of travel records” might confirm or deny Lansdale’s presence in the Dallas region at the time, but factors such as the “small likelihood” of finding such records and their “relative unimportance” indicated that such effort was “not worth checking out.” (Summary ,p 11) In 1991, at the time of the JFK film, Lansdale could be traced to Fort Worth, Texas mid-November 1963. Subsequent information has placed Lansdale in Denton, a Dallas suburb, on the evening of November 21, 1963.[21]

In sum, despite the brutal Summary composed in the aftermath of Prouty’s appearance before the ARRB’s Military Records Team, none of the ten points presuming to “debunk” his “allegations” actually hold up under scrutiny. That is, while the ARRB’s panel makes much of Prouty’s supposed failure to produce information outside his jurisdiction, such as Secret Service “manuals” (of which they aren’t even sure exist in the first place), and proceed to criticize his lived experiences, there is nothing actually incorrect or overstated in his observations. Latter-day critics lionize the Military Records Team’s Summary conclusions using a superficial reading based largely on the Team’s own predetermined finger-pointing, which was biased and subject to partial knowledge later superseded. However, there was one data point appearing in the Summary which has held up over the years as an accurate statement:

“Fletcher Prouty was where he says he was during the period from 1955-1964. His position can be documented.” (P. 13)

II

Prior to the release of Oliver Stone’s JFK in late 1991, L. Fletcher Prouty was a relatively inconspicuous figure known to few outside of aging participants of early Cold War military/intelligence circles, or committed parapolitical researchers and their small followings. The backlash directed against the film – which began while it was still filming – attacked the intellectual foundation of the screenplay, as personified by director Oliver Stone (purportedly being “fooled” by Warren Commission critics), the film’s “compromised” protagonist (Jim Garrison) and, to a lesser extent, the insider Fletcher Prouty (known in the film as “Mister X”).

A photocopy of Diamond’s Guardian article was anonymously submitted to the JFK production office, along with several typewritten pages of “opposition research” directed at Prouty.

A photocopy of Diamond’s Guardian article was anonymously submitted to the JFK production office, along with several typewritten pages of “opposition research” directed at Prouty.

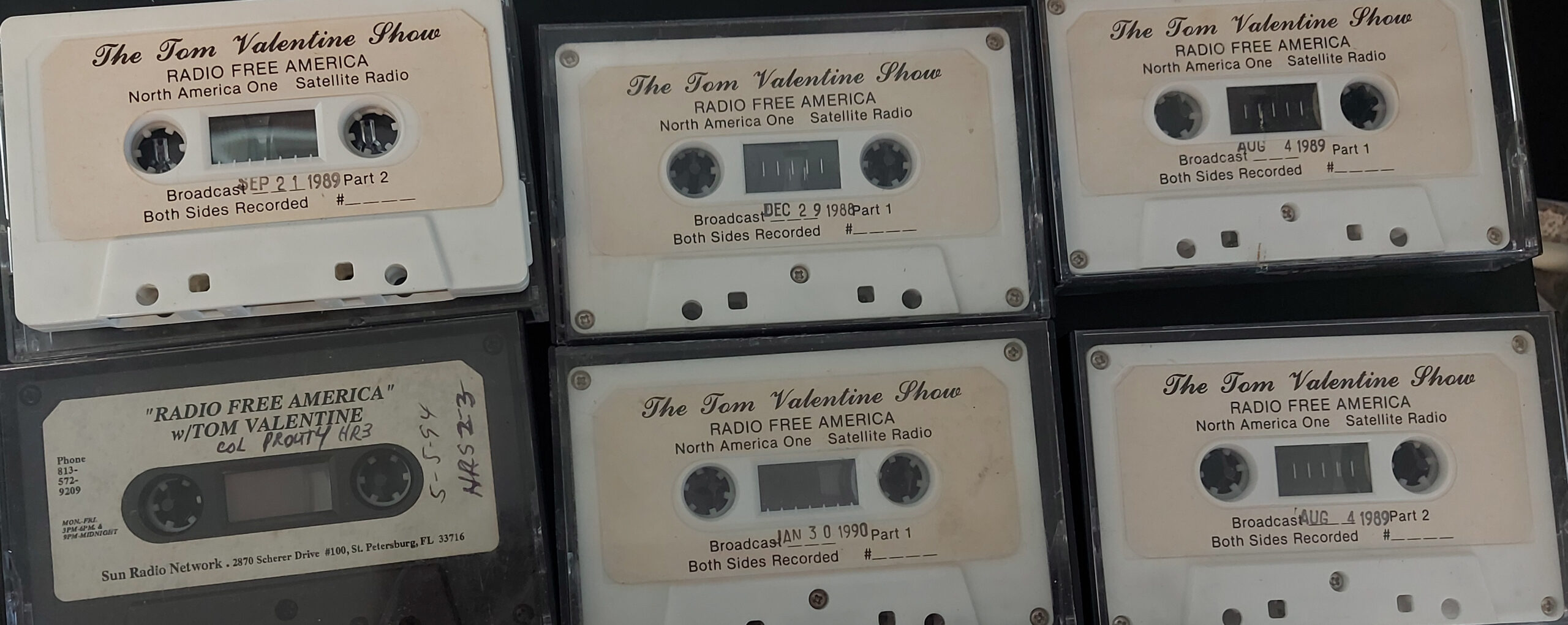

All three were in the crosshairs of an article published in the November 1991 issue of Esquire Magazine. With the punning title “The Shooting of JFK”, author Robert Sam Anson put together one of the key contributions to the anti-JFK literature from the period, covering the film’s production. While bashing first Stone, then Garrison, and then turning to Prouty in a late-article segment which combined character assassination with an offhand revelation of why it was exactly the establishment had problems with the film.[22]

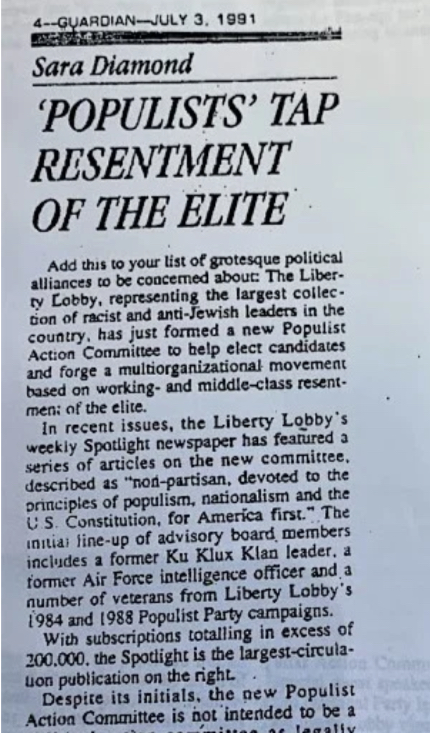

Anson introduces Prouty as a genial grandfather type, at least as so impressing the JFK production office, but notes the whispers of “cautious buffs” who are “leery” and wary of Prouty’s background and “claims.”[23] Suddenly, in the production office, a “small thing” starts “the trouble”, and reporter Anson, despite the staff’s nondisclosure agreements, manages to be in the know and in the loop. Anson reports that some of the office’s research staff had been paging through “a tiny left-wing New York weekly” and, by chance, discovered an article identifying Fletcher Prouty “as a cause célèbre in the virulently anti-Semitic, racist Liberty Lobby.”[24]

The article in question – ‘Populists’ Tap Resentment of the Elite – written by Sara Diamond and published in the July 3, 1991 issue of The Guardian (NYC) – was a legitimate investigative work, and the specific references to Prouty’s activities were accurate. While, to those who knew Prouty, the concept he was a racist fellow-traveler in step with the most virulent members of the Lobby, or even a “right-winger” as portrayed, appeared fringe and absurd, within Stone’s production office the general consensus was Prouty’s associations “looked bad” and could be a “public-relations time-bomb” for the JFK film.[25] The top researcher on staff told Stone: “Basically, there’s no way Fletcher could be unaware of the unsavory aspects of the Liberty Lobby.”[26]

The Connections to the Liberty Lobby

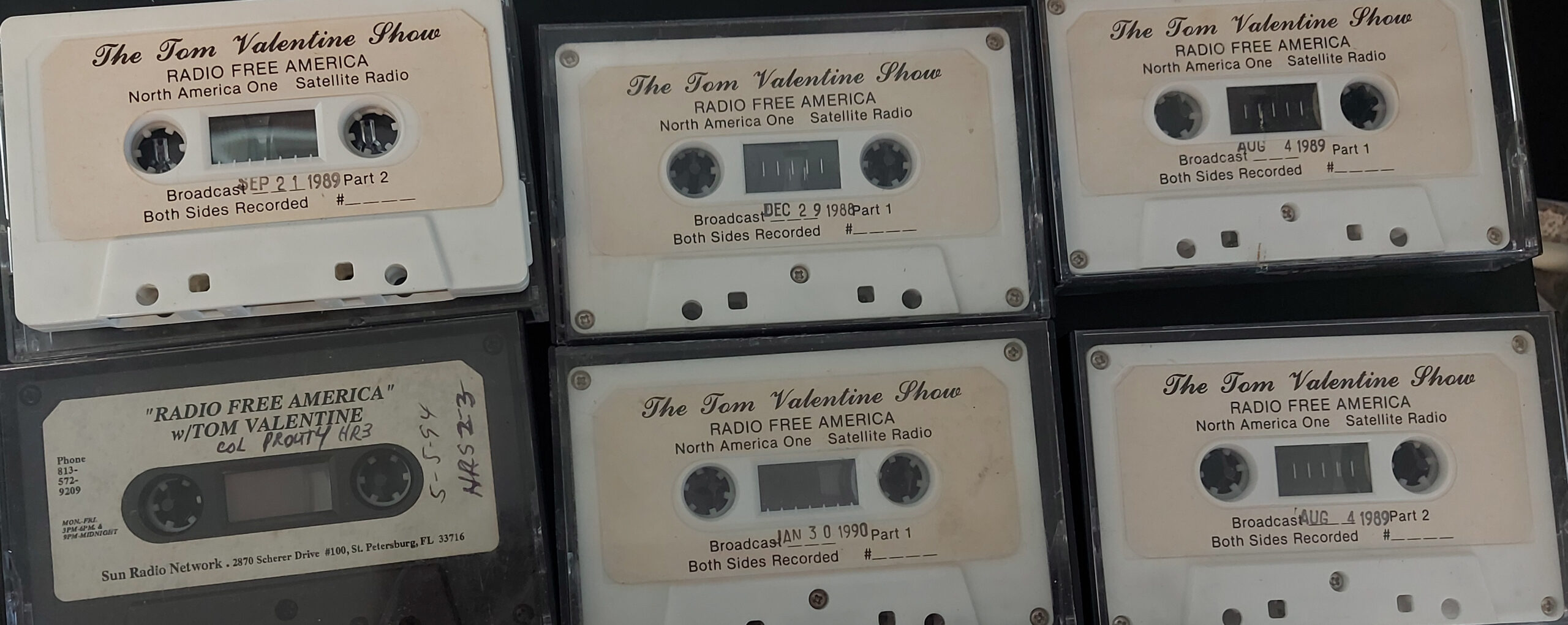

The finger-pointing directed at Prouty associating him with the Lobby was based on essentially four items: guest appearances on a syndicated radio program – Radio Free America – hosted by Tom Valentine and sponsored by The Spotlight, the Lobby’s weekly newspaper (numerous appearances 1988-94)[27];a speaking engagement at The Spotlight’s annual national convention (September 1990); the re-publication of Prouty’s The Secret Team by the Lobby’s imprint Noontide Press (autumn 1990)[28]; and Prouty’s being named to a national policy advisory board for the Lobby’s Populist Action Committee, (spring 1991).[29]

Cassettes from Radio Free America, Tom Valentine’s syndicated AM radio program. Prouty was a popular guest with both the host and the audience, appearing several times a year through 1994.

Cassettes from Radio Free America, Tom Valentine’s syndicated AM radio program. Prouty was a popular guest with both the host and the audience, appearing several times a year through 1994.

Taken at face value, in addition to the radio program which he appeared several times a year from 1988-94 as a popular guest, the links may stem from the longer association of Prouty’s colleague Mark Lane with the Liberty Lobby, representing them across several lawsuits in the mid-to-late 1980s. The experiences would result in a book, Plausible Denial, published in 1991, for which Prouty wrote the Foreword. In his book, Lane describes how his interest in representing the Liberty Lobby was piqued by the convergence of the initial litigation, which involved E. Howard Hunt, with the JFK assassination. Lane felt it was an opportunity to litigate a facet of that lingering controversy, and potentially assist its eventual resolution.

Prouty’s brief direct association with Lobby-related groups in late 1990 / early 1991 is coincident with the preparation of Plausible Denial.

When You’re A Hammer, Everything Looks Like A Nail

As it happened, there were at least three researcher/reporters working the far-right “beat” in 1990-91, observing activity sponsored by the Liberty Lobby. One was working for the Anti-Defamation League.[30] The second was Sara Diamond, the author of the piece published in the “tiny left-wing New York weekly”, and at the time working on a UC Berkeley sociology PhD, eventually producing a dissertation entitled “Right Wing Movements in the United States 1945-1992”. The third was activist Chip Berlet, concentrating on the influence of America’s political right with particular concern directed to overlap, or convergence, of the right with the left.[31] Both Berlet and Diamond were outspoken with their opinion that alliances between the extreme right and the Left, initiated through mutual disagreement with official policies such as the Gulf War, was a “bad idea” and perhaps part of a strategic plot by the right to co-opt or discredit Progressives.[32]

Berlet was in attendance at the 1990 Spotlight conference, at which Prouty spoke, and at which both Mark Lane and Dick Gregory also appeared.[33]Acknowledging the conference’s attention to looming foreign policy controversies in the Middle East,Berlet wrote: “There was considerable antiwar sentiment expressed by speakers who tied the U.S. presence in Saudi Arabia to pressure from Israel and its intelligence agency, Mossad…No matter what actual political involvement, if any…the themes discussed at the Liberty Lobby conference tilted toward undocumented anti-Jewish propaganda rather than principled factual criticisms.”[34] However, rather than analyze the contrasts between the propaganda and the factual criticisms, Berlet is more interested in highlighting links between individuals and organizations, and connecting overarching thematic concepts between them. So the content of Prouty’s remarks, with the topic “The Secret Team”, is not discussed, but his acknowledgment during the presentation of Noontide Press for republishing his book is.[35] Similarly, the reader learns who followed Prouty to the podium, who participated in a panel Prouty moderated, how The Spotlight paraphrased the event, and even how persons “associated” with the Liberty Lobby later circulated antiwar literature “at several antiwar rallies.”

Researcher Laird Wilcox, editor of the annual Guide To the American Right surveys, criticized in the 1990s what he termed an “anti-racist industry”, claiming anti-racist groups had consistently overstated the influence of what are in fact fringe movements, and named both the ADL and Political Research Associates as having engaged questionable tactics to support their conclusions.[36] “Mr. Wilcox says what most watchdog groups have in common is a tendency to use what he calls ‘links and ties’ to imply connections between individuals and groups.”[37]

‘Links and ties’ is certainly not an uncommon technique, particularly for political research. It does however produce a lot of “false positives”, and researchers are perhaps therefore best served exercising a degree of due diligence and establishing secondary sources before jumping to conclusions – such as Diamond’s linking Prouty to the “extreme right” or Berlet labelling him a “fascist”.[38]This can be compounded by a rhetorical strategy of using broad brush strokes to establish and portray monolithic racialist structures – a tendency which may be effective as a partisan effort to “sound the alarm”, but which can be misleading and reduce political complexity to simple and skewed dichotomies.[39]In this fashion, the Liberty Lobby’s weekly newspaper The Spotlight was assumed by the three researchers as necessarily a tool of the anti-Semitic foundation of the Lobby, and was therefore, in their perception, obviously engaged primarily in disseminating that message (although much of that effort may appear in code).[40] Other information portrays The Spotlight, at least during the time in question, as servicing a broader populist conservative community. The publication is described in Kevin Flynn’s 1989 investigative The Silent Brotherhood as “one of the right wing’s most widely read publications”, attracting “a huge diversity of readers, from survivalists and enthusiasts of unorthodox medical treatments to fundamentalist Christians and anti-Zionists.”[41]Daniel Brandt’s NameBase, a parapolitical research tool, described The Spotlight in 1991 as “anti-elitist, opposed to the Gulf War, wanted the JFK assassination reinvestigated, and felt that corruption and conspiracies could be found in high places.”[42]

Prouty himself responded to the criticisms of his “links and ties” to the Liberty Lobby as follows:

“I’ve never written for Liberty Lobby. I’ve spoken as a commercial speaker, they paid me to speak and then I left. They print a paragraph or two of my speech same as they would of anybody else, but I’ve never joined them. I don’t subscribe to their newspaper, I never go to their own meetings, but they had a national convention at which asked me to speak and they paid me very, very well. I took my money and went home and that’s it. I go to the meeting, I go home, I don’t join.”[43]

III

An honest review of the “hatchet-jobs” directed at Fletcher Prouty invariably sources to the time frame of 1991-1992, coinciding with the U.S. establishment’s attack on Oliver Stone’s JFK film, conducted through its legacy media. In light of that, a curious feature of Robert Sam Anson’s Esquire piece is its concluding section, following directly from the Liberty Lobby “cause célèbre” takedown of Prouty, which had in turn followed a concentrated bashing of Stone and then Jim Garrison. Rather than continuing with the overt criticism, the concluding section hastily endorses a new personage with a point of view said to gel with Stone’s general thesis of JFK’s intention to exit Vietnam, but with a non-conspiratorial spin.

Prouty with John Judge in early 1992. Small circulation VHS interviews were among the limited options available for efforts to support and supplement Stone’s “JFK”.

Prouty with John Judge in early 1992. Small circulation VHS interviews were among the limited options available for efforts to support and supplement Stone’s “JFK”.

The new personage was John Newman, well-regarded these days with a solid thirty-year run of intensively detailed histories of the Kennedy administration’s national security challenges. Upon this introduction, Anson sets out immediately to contrast Newman with Prouty, utilizing complementary adjectives: Newman is described as “meticulous, low-key, methodical, highly experienced, characteristically cautious” while Prouty is “ever-voluble” and prone to jumping to conclusions. Anson strongly infers that Newman expresses what amounts to the “good” interpretation of events, while Prouty embodies the misshapen “buff” perspective.

On the other hand, Newman’s perspective still confirms the previously fringe viewpoint that Kennedy had developed a Vietnam policy anticipating an eventual complete withdrawal of “military personnel”, which the JFK film had adopted. Anson opts to promote a presumed back-channel “secret operation” designed to “systematically deceive” the White House so to encourage expansion of the US effort in Vietnam. This secret operation is proposed to be “the real story” above and beyond Fletcher Prouty’s musings regarding the distinctions between National Security Action Memorandums 263 and 273. In the fullness of time, the “back-channel secret operation” never proved a viable hypothesis, while Prouty’s intuitive commentary on NSAM 263 and 273 has been effectively accepted even if debate over motivation continues.

Therefore, the two express “hatchet-jobs” directed at Prouty in 1991 and 1996 – the Esquire piece and the ARRB interview – both promoting the pretension that Prouty was unstable and his concepts were easily “debunked” by the official record, have proved to be fundamentally in error, first over the NSAMs and second over the military intelligence units. To this day, Prouty’s detractors still cannot articulate where exactly he is wrong – about the assassination or about his experiences during his military career. This is why such criticisms invariably fade into a drab curtain of distraction, stained with reference to the Liberty Lobby, Scientology, Princess Diana, and other irrelevancies.

Oliver Stone put it well in his published response to Anson’s Esquire piece: “(Prouty’s) revelations and his book The Secret Team have not been discredited in any serious way. I regret his involvement with Liberty Lobby, but what does that have to do with the Kennedy / Vietnam issue?…I have not, nor do I intend, to ‘distance’ myself in any way from Garrison’s or Colonel Prouty’s long efforts in this case. They may have made mistakes, but they fought battles that Anson could never dream of.”

NOTES:

[1] Mcadams’ Prouty entry on his JFK assassination website was an oft-cited compilation of disparaging talking points. Most if not all of this concerted “debunking” has in turn been debunked. Disputes over the factual record and Mcadams’ seeming influence over certain Wikipedia gatekeepers (editors) resulted in a classic essay discussing narrative management and the internet: Anatomy of an Online Atrocity: Wikipedia, Gamaliel, and the Fletcher Prouty Entry

[2] See Fletcher Prouty vs the ARRB by Jim DiEugenio for the full story.

[3]Memorandum dated Sept 11, 1996.

[4]L. Fletcher Prouty Talks to the ARRB

[5]Interview Summary, prepared October 23, 1996 by Christopher Barger

[6]Memorandum is found on page 70 of this link.

[7] Ibid

[8] Interview Summary p11. In context, Prouty’s reference to the Warren Report is based on the understanding it was fully part of a cover-up operation and therefore wholly unreliable as a “historic” record and, in that regard, useless as a “source document.” Prouty’s work never had the pretension to specifically “criticize” the Report for this reason.

[9] In some instances, the panel holds Prouty as “unreliable” due to his reluctance to identify individuals, despite his specific caution at the interview’s start that he will not identify individuals who are/were operational – “I never name a man who is operational. Never.” He was also labelled unreliable by being unable to produce particular documentation, although he had explained that the types of documents they sought either never existed or had been long destroyed.

[10] The full transcript of the September 24, 1996 interview with Prouty can be accessed here.

[11] Allegation #1: Trip to Antarctica may have had sinister connotations. Interview Summary p2

[12] L. Fletcher Prouty, JFK: The CIA, Vietnam and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy, Introduction by Oliver Stone (New York: Citadel Press, 1992), p. 284. “I have always wondered, deep in my own heart, whether that strange invitation that removed me so far from Washington and from the center of all things clandestine that I knew so well might have been connected to the events that followed.”

[13] “Result or conclusion by ARRB:…Prouty made no statements for the record to back up the suspicions he mentioned in the excerpt from his book cited above.” Interview Summary p3.

[14] “it is alleged that the Christchurch Star, when running its first story about the assassination, included biographical information on Lee Harvey Oswald and named him as the accused before he had actually been arraigned for the crime in Dallas. The allegation is also made that the first reports from Dealey Plaza, which were not entirely accurate, were sent out as a part of a ‘cover story’ of some sort.” Interview Summary p3.

[15] The rapid identification of Oswald as first the main and eventually the only suspect remains to be accounted for, particularly as the evidence was sparse and the suspect was denying everything. It is not known how or why the FBI concluded Oswald “did it” an hour after his arrest, or the process by which the wire services soon after were presumably signalled that Oswald’s identity and biography was newsworthy. There were other arrests made in connection with Dealey Plaza, but none other than Oswald featured names and personal biographies splashed across the evening news.

[16] L. Fletcher Prouty, JFK: The CIA, Vietnam and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy, Introduction by Oliver Stone (New York: Citadel Press, 1992 p. 294. Plausible Denial p XV.

[17] See: “Fletcher Prouty vs the ARRB” by Jim DiEugenio

[18] interview transcript p36 Prouty’s tone in reply is noted: “(testily) See, we’re overdoing this. I went to Mexico City once, so I’d know the business…”. In the Summary, the descriptive “(testily”) is changed to “(Very agitatedly)” Summary Barger p8

[19] Wray: “…When you say “the Secret Service was not in Dallas” do I understand you are speaking a little bit figuratively there? That they may have been there, but weren’t doing their job thoroughly? Or do you mean literally, that they were not there?” Interview transcript (P36).

[20] Barger Summary p8. Prouty in fact discussed his experience, which was in 1955 in Mexico City

[21] pp 261-262 Alan Dale with Malcolm Blunt, The Devil Is In The Details, self-published 2020. Prouty’s identification was confirmed by his Pentagon boss Victor Krulak in a personal letter written in the 1980s. There have been claims such letter never existed, but it is be found in the Prouty document archive maintained by Len Osanic.

[22]Anson had previously written They’ve Killed the President, Bantam 1975, in which he first bashed Garrison and his truncated investigation.

[23]According to Anson, the whispers suggested Prouty “had a tendency to see the CIA’s dark hand everywhere…Another liability was Prouty’s fondness for putting himself at the center of great events.” These suggestions seem to refer to Prouty’s military career, during which, most everyone agrees, he worked closely with CIA and “was where he says he was…his position can be documented.”

[24]This may not be an accurate account of this discovery, as around the same time the research staff had been forwarded a photocopy of the article in question, along with several typewritten pages referring to complementary research by a researcher with the Anti Defamation League. Both sources supplied similar reference to associations between Prouty and groups linked with the Liberty Lobby. It is possible the chance “discovery” was more accurately described as the arrival of unsolicited opposition research forwarded to the Stone office. Exactly how Anson got word of this is not known.

[25]Anson writes: “When questioned, Prouty, the intelligence expert, pleaded ignorance. He had not known of (Liberty Lobby founder) Carto’s Nazi leanings, he insisted…As for (Carto’s) assertion that the Holocaust was a lie, (Prouty)…would say only, ‘I’m no authority in that area.’ ‘My God,’ moaned a Stone assistant after listening to the rationalizations. ‘If this gets out, Oliver is going to look like the biggest dope of all time.’” This paragraph can be read as inferring Stone’s team confronted Prouty and were listening directly to his response. Anson’s sentence structure, however, is not exactly precise and leaves open the possibility, or likelihood, that someone else conducted this questioning of Prouty, under unknown circumstances, and that the staffers “listened” to the “rationalizations” second-hand.

[26]This opinion is something of an extrapolation, also expressed by Anson i.e.: “When questioned, Prouty, the intelligence expert, pleaded ignorance.” This presumes Prouty’s attention to detail in his professional capacity necessarily carried over to other aspects of his life. Such presumption is not entirely accurate as, for example, at the time they first met, Prouty was entirely unfamiliar with Oliver Stone and had not seen any of his films, despite the publicity associated with Stone’s career momentum in the 1980s and his three Oscar wins.

[27]Prouty’s appearances, across several years, were cited as a clear indication of his “being up to his neck in the racist right movement”. Len Osanic has copies of Prouty’s Radio Free America appearances on cassette, and says the claim, sourced to Anti Defamation League researchers, that the program engaged in routine anti-semitism and Holocaust Denial are “nothing”. Osanic says Prouty’s appearances were essentially similar to the contemporaneous Karl Loren Live broadcasts from Los Angeles which Prouty also appeared during this period. The author has reviewed several of Prouty’s interviews with Valentine and concurs with Osanic. The discussions cover ground exactly similar to most other interviews Prouty gave at the time, the content of which are entirely uncontroversial.

[28]Prouty told Len Osanic the publication was a “one-time” commitment, a limited press run for which Prouty received a small amount of money. Prouty told Osanic that he understood Noontide as specializing in editions of books which had fallen out of circulation. Noontide, at the time, had also republished Leonard Lewin’s Report From Iron Mountain. The original edition of The Secret Team in 1973 was subject to distribution problems. Prouty discussed this in a note to the 1997 edition: “ After excellent early sales of The Secret Team during which Prentice-Hall printed three editions of the book, and it had received more than 100 favorable reviews, I was invited to meet Ian Ballantine, the founder of Ballantine Books. He told me that he liked the book and would publish 100,000 copies in paperback as soon as he could complete the deal with Prentice-Hall…Then one day a business associate in Seattle called to tell me that the bookstore next to his office building had had a window full of the books the day before, and none the day of his call. They claimed they had never had the book. I called other associates around the country. I got the same story from all over the country. The paperback had vanished. At the same time I learned that Mr. Ballantine had sold his company. I traveled to New York to visit the new “Ballantine Books” president. He professed to know nothing about me, and my book. That was the end of that surge of publication. For some unknown reason Prentice-Hall was out of my book also. It became an extinct species.” The Secret Team book, and its unavailability, was referred several times on the Valentine radio program ahead of the republication.

[29]Prouty agreed to the use of his name, but said he had no other involvement with the Committee, i.e. he never provided advice or attended any meetings.

[30]This may have been Kenneth McVay, whose work, later published online, corresponds to the cited information sent to Stone’s office; see this and this.

[31]Berlet’s divisive rhetoric targeted “virtually every independent critic of the Imperial State that the reader can name”, which at the time in question (1990-91) included “the Christic Institute, Ramsay Clark, Mark Lane, Fletcher Prouty, David Emory, John Judge, Daniel Brandt” et al. Ace Hughes, Berlet for Beginners, Portland Free Press, July/August 1995.

[32]Berlet, Chip. Right Woos Left: Populist Party, LaRouchite, and Other Neo-Fascist Overtures to Progressives, and Why They Must Be Rejected, 1999, Political Research Associates.

[33]“Other conference speakers and moderators at the September 1990 Liberty Lobby convention included attorney Mark Lane, who has drifted into alliances with Liberty Lobby that far transcend his role as the group’s lawyer, and comedian and activist Dick Gregory, whose anti-government rhetoric finds fertile soil on the far right.” Berlet, Chip. Right Woos Left p40

[34]ibid

[35]A public expression of gratitude to the publishers is a routine dedication for authors.

[36]Wilcox, Laird The Watchdogs 1997 self-published.

[37]Researcher Says ‘Hate’ Fringe Isn’t As Crowded As Claimed, Washington Times, May 9, 2000. p.A2

[38]NameBase is a cross-indexed database tool for “anti-Imperial” researchers, initiated by Daniel Brandt. Chip Berlet, along with Fletcher Prouty, was on the NameBase Board of Advisors in 1991 when Berlet, describing Prouty as a “Larouche-defender”, announced his refusal to remain on the same Board. Brandt encouraged Berlet to leave, saying “When it came to making a choice between Prouty and Berlet, it was a rather easy decision for me to make.” Berlet took three other Board members with him, and a lingering feud percolated for many years after. See this.

[39]Via “links and ties”, it was common for right-wing rhetoric in the 1960s to label ideological opponents as literally Communist agents embedded within civil rights and other movements. Debates over methodology – such as links and ties – which were frequent in the 1990s, highlighted the expanding scope of identified political “enemies” (a debate again familiar in today’s polarized political and social landscape). This expansion resulted in erroneous claims such as that Prouty held right-wing, or even “extreme right-wing” political views, claims which are unfortunately being currently recycled by a small faction of researchers.Prouty never openly discussed his personal politics, other than to say “the only club I’ve joined is the Rotary Club.” Prouty, in the author’s opinion, could be fairly described as a “mid-century main-street Rotary Club American”.

[40]Diamond is referred: “to understand where the Liberty Lobby and its supporters are coming from, you have to understand their code language, which seldom if ever attacks Jews directly, but instead refers to ‘the big medical establishment, the big legal establishment, the major international bankers’, all of them controlled by you know who.” The obvious problem with this proposition is that determining what is “code” and what is legitimate criticism is often a wholly subjective enterprise. Also, a “code” requires both the disseminators and the receivers to be “in” on the cipher interpretation.

[41]The Spotlight “regularly featured articles on such topics as Bible analysis, taxes and fighting the IRS, bankers and how they bleed the middle class, and how the nation is manipulated by the dreaded Trilateral Commission and the Council on Foreign Relations.” p. 85. Flynn, Kevin and Gerhardt, Gary, The Silent Brotherhood: Inside America’s Racist Underground, The Free Press, 1989.

[42]“we found only rare hints of international Jewish banking conspiracies or the like in The Spotlight.” See this.

[43](Col. L. Fletcher Prouty Responds to Accusations of Involvement in Right Wing Extremist Groups Interview Date: April 3, 1996. – Col L. Fletcher Prouty Reference Site. There is no record of Prouty expressing extremist or racist views, as the researchers cited admit: “Diamond says that Prouty himself has, as far as she has been able to determine, made no public racist or anti-semitic utterances.” “Berlet states that Prouty himself has never made any overt anti-semitic or racist comments…” (typewritten document submitted to Oliver Stone’s production office) “Nothing here shows Prouty to have been a Nazi or an anti-Semite…” John Mcadams. This has not prevented a few contemporary critics from asserting that Prouty was, in fact, anti-semitic. This notion appears to be based on two items: an advance notice for a 1991 Liberty Lobby event which lists Prouty as a prospective speaker (Prouty did not in fact appear); and a 1981 private letter authored by Prouty in which, discussing the looming AWACS deal some months ahead of Reagan’s controversial public announcement, Prouty uses the phrase “Jewish Sgt” during a discussion of potential military logistic compromises associated with computerized systems relying on multiple inputs from different locations. The cherry-picked phrase, as presented, reveals essentially a lack of basic knowledge of the historic issue and perhaps a misunderstanding of the term “anti-semitic”. For a balanced perspective on the AWACS controversy see: Gutfeld, Arnon, The 1981 AWACS Deal: AIPAC and Israel Challenge Reagan, Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies.