Introduction

In January 2019, a petition began circulating where, among other startling affirmations, the 2500 signatories, including prominent JFK assassination experts, agreed that, “As the House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded in 1979, President John F. Kennedy was probably killed as the result of a conspiracy. In the four decades since this congressional finding, a massive amount of evidence compiled by journalists, historians and independent researchers confirms this conclusion. This growing body of evidence strongly indicates that the conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy was organized at high levels of the U.S. power structure, and was implemented by top elements of the U.S. national security apparatus using, among others, figures in the criminal underworld to help carry out the crime and cover-up.”

The destruction of classified documents pertaining to the JFK assassination and the refusal to release others 58 years after the assassination only strengthens the perceptions of the conspiracy researchers.

One of the premises that is key to this scenario is that when ex-marine Oswald entered the Soviet Union in 1959 and spent two and a half years there, he did so as a false defector within a program called REDSKIN.1

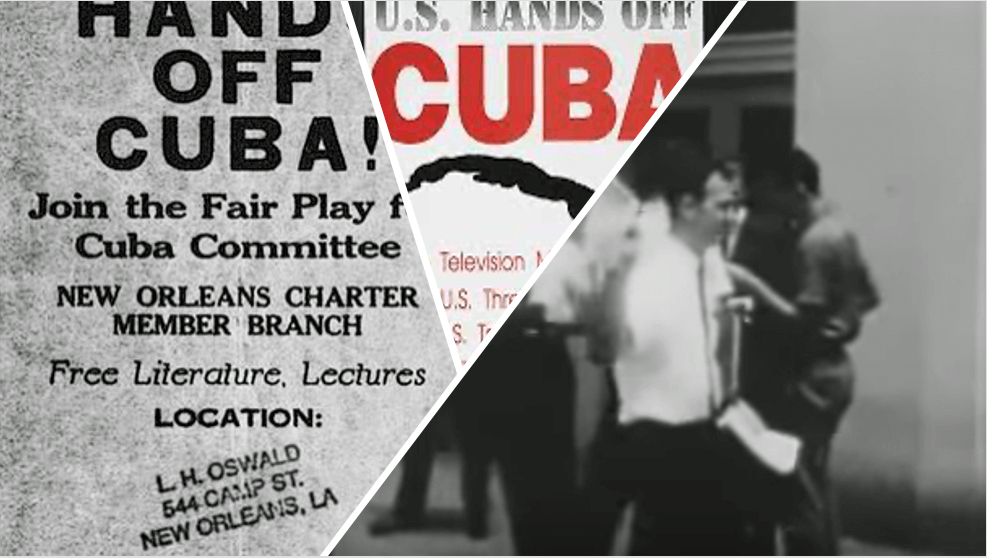

Given the above, shouldn’t the most plausible premise for Oswald launching the Fair Play for Cuba Committee chapter in New Orleans, perhaps the most hostile city for such an endeavor at a time when the FPCC was in a downward spiral, be that it was also an intelligence operation?

Oswald’s strange dance with the FPCC in the months leading up to the assassination is not scrutinized enough––as this quest put Oswald right in the realm of those who would later accuse him of being Kennedy’s killer.

What do we really know about the Fair Play for Cuba Committee? It lacks scrutiny even though, like his adventure in Russia, the evidence of intelligence is everywhere. However, context and insight about the FPCC is lacking, even though it should have been turned inside out by the WC and the HSCA. But it was not, thanks largely to Allen Dulles, George Joannides and other spies who knew what to hide and were perfectly placed to obstruct real investigations.

Research into the FPCC will help lay the groundwork for what should have been a leading hypothesis that should have guided the investigations: that is, that Lee Harvey Oswald was again following orders when he penetrated the FPCC, thereby turning him into an ideal patsy for the assassination of the President.

The FPCC: A Brief History

In 1993, author Van Gosse wrote Where the Boys Are: Cuba, Cold War America and the Making of the New Left. It gives one of the more complete accounts of this odd association.

The FPCC was founded in the spring of 1960 by Robert Taber and Richard Gibson––CBS newsmen who covered Castro’s ascent to power––as well as Alan Sagner, a New Jersey contractor. Its original mission was to correct distortions about the Cuba revolution. It was first supported by writers, philosophers, artists and intellectuals such as Norman Mailer, Truman Capote and Jean-Paul Sartre. It also touched a chord with university students. Some estimates place its African American membership at one third of its roster. In April 1960, Taber and Gibson ran a full-page ad in the New York Times.

Around Christmas time 1960, it organized a huge tour to Cuba, which led to a travel ban to the country by early 1961. According to Gosse, its high point was after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. There was no official membership headcount, but organizers claimed the FPCC had between 5 and 7 thousand members and 27 adult chapters, almost all in the Northeast, a few on the West Coast and only one in the Southeast in Tampa.

When it became clear that the U.S. would not tolerate the revolution, it began dissipating. After a short-lived peace demonstration binge during the missile crisis in 1962, its spiral downwards was accelerated and the FPCC died not long after one of its members allegedly killed JFK.

The FPCC was characterized as “Castro’s Network in the U.S.A.” by the HUAC. Membership within this anti-U.S. organization was described during hearings as an effective door opener to enter Cuba via the Cuban Embassy in Mexico City and Cubana Airlines. Though the HUAC had been seriously rattled by the McCarthy-era witch hunts, Castro was breathing some new life into this outfit for political showcasing of American patriotism. The FBI may even have bribed an FPCC insider to testify that a launch ad placed by the FPCC was financed by Cuba.

The Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (also known as the Eastland Committee) questioned Dr. Charles Santos-Buch, a young Cuban physician, who was a self-described FPCC organizer. On January 6, 1961, Santos-Buch told chief prosecutor Julian Sourwine that he and Taber had received the needed money from “eight different people.” The documents reveal that Santos-Buch changed his story on January 9 at a subsequent executive session, and that he was also given a promise that the CIA would help get a number of family members out of Cuba. He changed his story, at least in part because of his desire to extricate his family from Cuba. On January 10, Santos-Buch publicly testified that he and Robert Taber obtained $3,500 from the Cuban government through the son of Cuba’s Foreign Minister Raul Roa. This money, along with $1,100 in funds from FPCC supporters, paid for the full-page FPCC ad in the April 6, 1960, edition of the New York Times. A week later, Jane Roman from James Angleton’s counterintelligence office in the CIA reported that security concerns made it too dangerous for the CIA to keep its promise to Santos-Buch.

According to one of its national leaders, Barry Sheppard, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) was very involved with the FPCC: “We came to be part of the leadership of the FPCC partly as the result of a crisis in the organization. The original FPCC leadership was somewhat timid, and shied away from forthright defense of the revolution as it radicalized. In response, Cuban members of the 26th of July Movement living in the U.S. aligned with the SWP and some other militants, and took over the leadership of the Committee.”

Sheppard’s memoir shows that the SWP was much larger than the FPCC. He describes protest mobilization during the Missile Crisis in 19622 this way:

We stood up to it. The PC discussed and approved the thrust of a statement to appear in the next issue of The Militant. It ran under the headline, “Stop the Crime Against Cuba!” We alerted SWP branches and YSA (Young Socialists of America) chapters that night to mobilize to support the broadest possible actions against the threat. In New York, there were two major demonstrations. One was called by Women Strike for Peace and other peace groups. We joined some 20,000 protesters at the United Nations on this demonstration. Then the Fair Play for Cuba Committee held its own action, more specifically pro-Cuba in tone, of over 1,000 people, also near the UN.

The following points concerning the July 1963 SWP convention cast even more suspicion around the timing and motives of the already suspiciously late openings of FPCC chapters in the deep south by Santiago Garriga in Miami and Oswald in New Orleans and the continued involvement with the FPCC by other odd subjects:

At the convention, a meeting of pro-Cuba activists discussed the situation in the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Cubans living in the United States who supported the 26th of July Movement had helped us build the FPCC. Now most of them had returned to Cuba. In most areas, the FPCC had dwindled down to supporters of the SWP and YSA. Since we did not want the FPCC to become a sectarian front group, the meeting decided to stop trying to build it. The FPCC then existed for a while as a paper organization, until the assassination of President John Kennedy dealt it a mortal blow.3

FBI reports confirm that FPCC National Chapter meetings plummeted from 25 meetings a year to 3 in its last year of existence.

Red Scares, the HUAC and McCarthyism

The first Red Scare in the U.S. took place in 1919-20 because of the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the fear of this movement spreading to the United States as well as the influx of immigrants that did include a small number of anarchists. In one case, a bomber blew himself up by accident in an attempt to assassinate John Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan. Because of this, the General Intelligence Division (the forerunner of the FBI) was formed and J. Edgar Hoover was chosen to lead it.

In 1938, The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA) was formed to investigate individuals, groups and organizations considered subversive or disloyal with a special focus on communist-leaning credos.

The second Red Scare is considered to have begun shortly after World War II in 1947, when President Truman signed an order to screen government employees, and lasted 10 years. Through the propaganda and grandstanding of politicians, working in symbiosis with the press and the FBI, panic and hysteria was omnipresent. The HUAC went into overdrive, with Senator Joe McCarthy as its poster boy and with the Communist-hating Hoover eager to oblige.

By 1956, after overstepping and ruining hundreds of lives, McCarthy was taken down by lawyer Joseph Nye Welchin his heroic “Have you no decency” retort during the Army-McCarthy hearings.

This, however, did not stop the anti-communist fervor of the FBI and CIA. They just became even sneakier with no regard for the rule of law.

COINTELPRO and AMSANTA

The Church report,4 in its section “USING COVERT ACTION TO DISRUPT AND DISCREDIT DOMESTIC GROUPS,” describes the illegal activities of the FBI that were put in motion between 1956 and 1971 under the acronym COINTELPRO [Counter Intelligence Program], which claimed to have as a motive the protection of National Security.

The FBI acted as a vigilante by not just breaking the laws but by taking the law into its own hands against both violent and nonviolent targets. Some of the targets were law-abiding citizens who were advocating change, but were labelled as domestic threats unilaterally by the FBI, e.g., Martin Luther King. Others were violent groups such as the Black Panthers and the Klan, where due process was ignored. Once the FBI started down this dangerous path, they not only targeted the kid with the bomb but also the kid with the bumper sticker!

Organizational targets fell under five umbrella groups: The Communist Party; The SWP; White Hate groups; Black Hate groups; and the New Left. This opened the floodgates to investigate any group that had a potential for violence, including nonviolent groups such as The Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was labelled as a Black Hate Group, as well as sponsors, civil-right leaders, students, protesters; and the list goes on …

The FBI used five main methods during COINTELPRO: infiltration; psychological warfare; harassment via the legal system; illegal force; undermining of public opinion.5

These actions stepped up in the wake of the Communist takeover in Cuba. Church Committee members exposed the dimensions of the mail opening program, and discovered that the CIA and FBI had placed the names of 1.5 million Americans in the category of “potentially subversive.” Together, both agencies opened about 380,000 letters.6

Larry Hancock, in Someone Would Have Talked, describes the FBI program called AMSANTA:

The program was initiated by the FBI as part of its effort targeting the FPCC as a subversive group and involved the CIA in briefing, debriefing and possibly monitoring travel of assets through Mexico City to and from Cuba. The program began in late 1962, had one major success in 1963 and appears to have been abruptly terminated in fall 63.

According to John Newman (Oswald and the CIA)7, the CIA, led by David Phillips and James McCord (of Watergate fame), began monitoring the FPCC in 1961. In December 1962, the CIA joined with the FBI in the AMSANTA project. A September 1963 memo divulged an FBI/CIA plan to use FPCC fake materials to embarrass Cuba.

There are strong indicators that the CIA efforts to penetrate and use the FPCC were local and illegal––such as spying on U.S. citizen/members of the FPCC. As a David Phillips asset stated, it was “At the request of Mr. David Phillips” that, “I spent the evening of January 6 with Court Wood, a student who has recently returned from a three-week stay in Cuba under the sponsorship of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.”8

The opening of a Miami FPCC chapter in 1963 by Santiago Garriga is more evidence of illegal domestic espionage on or through the FPCC by the CIA. According to Bill Simpich, author of State Secret, Garriga’s resumé was perfect for patsy recruiter/runners––interaction with Cuban associates in Mexico City; seemingly pro-Castro behavior; and his crowning achievement: like Oswald in 1963, he opened an FPCC chapter in a market deemed very hostile for such an enterprise.

Garriga is the potential fall guy who is the most clearly linked with intelligence. Like Oswald, he could be portrayed as a double agent by those who packaged him. What makes Garriga so unique are, as Simpich writes, his pseudonym and close links with William Harvey’s (CIA Cuban Affairs) team. To cover this intriguing lead, it is best to cite a few excerpts from State Secret:

During October 1963 Garriga worked with other pro-Castro Cubans to set up a new chapter of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee in Miami … Although it appears that Garriga’s ultimate loyalty was with the Castro government, it’s likely that Garriga’s FPCC activity was designed by Anita Potocki (Harvey’s chief aide at the wiretap division known as Staff D) to set up a flytrap for people like Oswald. Maybe even Garriga himself was considered as a possible fall guy.

However, in the days before 11/22/63, the FBI ran an operation that investigated the Cuban espionage net that included Garriga and shared the take with the CIA. The CIA referred to this investigation as ZRKNICK. Bill Harvey had worked with ZRKNICK in the past … The memos that identify Garriga were written by Anita Potocki.

Was there something sinister in this effort to set up FPCC Miami? It certainly looks ominous, given that AMKNOB-1 is the main organizer and that Anita Potocki is one of his handlers. The FPCC leadership recognized that it was dangerous to set up such a chapter in Miami due to the possibility of reprisals by Cuban exiles. For just these reasons, the FPCC leadership had discouraged Oswald from publicly opening an FPCC chapter in the Southern port town of New Orleans.

The fingerprints of AMSANTA and COINTELPRO were also all over Oswald.

Targeting the FPCC

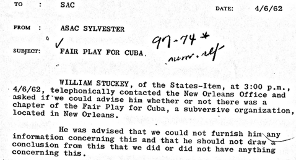

By the time Oswald opened his Crescent City chapter of the FPCC, it was under the intense scrutiny which had started in 1960, the year of the national launch. An FBI report9 in response to NSAM 43 and 45 to the attorney general, dated April 24, 1961, outlines steps taken by then to counter pro-Castro organizations. It was already a full-court blitz.

In this document, the FBI makes it clear that the Castro movement is a serious threat to the U.S. The FPCC is underlined as a key target pursuant to Executive Order 10450. The overall coverage of pro-Castro activities in the U.S. is described as having begun in November 1955 when Castro came to the U.S. looking for financial support for the rebel cause, and the 26th of July Movement started up in the U.S. When Castro took power in January 1959, the FBI had files on this organization as well as lists of members it shared with other intelligence agencies and sharply expanded its surveillance operations. Spying on Cuban diplomatic institutions, questioning defectors and the infiltration of pro- and anti-Castro groups with informants, are listed as key Intel tactics.

By the time the report was written10, the FBI numbers the pending matters at 1000 and information sources at over 300. The FBI had by then identified 140 Castro supporters in the U.S. who constituted a threat to security. “We are maintaining close coverage of the various Cuban establishments as well as pro-Castro groups and their leaders,” which was shared generously with other intelligence groups. The FPCC is described as the most important such group, and received support from Cuba as well as the SWP and CP, according to the report.

The FBI claimed that Cuban agents were receiving assistance from their surveillance targets and that Cubana Airlines was an important tool for their activities. The FBI was keeping close tabs on pro-Cuba propaganda. Covert informants were given a T symbol,11 preceded by a location identifier such as NY for New York, followed by a number. Also identified were the locations they could report on and the subject matter. Some informants were government employees, post-office workers, intelligence assets on assignment (June Cobb was assigned to spy on Richard Gibson and slander Oswald in Mexico City)12 and freelancers (as we will see later Ruth Paine quite possibly was a provider of FPCC intelligence), etc., who could oversee documentary movement around targets. Others infiltrated FPCC chapters and were present during meetings. These would report on who was present, who said what, and the materials shown and exchanged. License plates of parked cars of meeting attendees were recorded. In some cases, chapter officers were key sources: Thomas Vicente (National), Harry Dean (Detroit), Harrold Wilson (Tampa), John Glenn (Indiana) were all definite or likely snitches for the FBI.

In April 1963, aided by Thomas Vicente, the FBI broke into FPCC NY offices for a black bag operation. FBI files indicate that NY alone had over 25 covert informers who were being used along with other sources. Tampa had at least 11 informants carrying the TP-T code.

The CIA also was all over the FPCC. Two days after the FPCC ad in the NY Times, William K. Harvey, head of the CIA’s Cuban affairs, told FBI counterintelligence chief Sam Papich: “For your information, this Agency has derogatory information on all individuals listed in the attached advertisement.” Other files confirm that Jane Roman and James Angleton were also monitoring the FPCC.

Recipients of intel included the Secret Service, the CIA, Customs Bureau, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the Post Office Department, the Aviation Agency, the Federal Communications Commission, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, the U.S. Information Agency, the Treasury Department, the U.S. Information Agency, the Bureau of Foreign Commerce. The report also stresses the importance of coordinated efforts with other intel agencies as well as local FBI offices.

After the failed Bay of Pigs and the Missile Crisis, we can assume that when Oswald, already notorious for his Russian adventure, opened an FPCC chapter in, of all places, New Orleans by the middle of 1963, he was a known quantity.

Frank S. DeBenedictis on the Tampa FPCC

In 2002, Frank S. DeBenedictis submitted a thesis13 about the Cold War coming to Ybor City, and the Tampa FPCC, for his Master of Arts at Florida Atlantic University. DeBenedictis adroitly points out that the reason FPCC files have been very difficult to access is that after the assassination of JFK, these files were categorized as classified JFK assassination files instead of Cold War files.

The following represents some of the key information/passages from his thesis. It is based largely on government and intelligence investigations of the FPCC, declassified JFK assassination documents, Van Gosse’s research, newspaper articles as well as FPCC propaganda and correspondence. Almost all of the FPCC chapters were situated in the North of the U.S. or along the West Coast. The reason Tampa was unique in hosting an important FPCC chapter was because it had a large Cuban exile population who were anti-fascist and had fled the brutal Marchado and Batista regimes. In 1955, Castro raised money there for his rebellion and had satellite followers to his 26th of July Movement. Ybor City (part of Tampa) was known for its Latino culture and its cigar industry.

By 1961, Eisenhower cut all ties with Castro, and the 26th of July Movement ceased activity in the U.S. It was being replaced by the FPCC. As Frank writes, “It was somewhat different from the older pro-Castro groups, since it came about after Castro was already in power. When Cuba formed ties with the Soviet bloc, the FPCC and its defense of Castro increasingly became part of the Cold War. By late 1961 the very active Tampa chapter had established its own newsletter, and drew attention from both Castro supporters outside Florida, and anti-Castro Cuban exiles and a variety of government operatives.”

The influx of anti-Castro Cuban exiles (including Batista followers as well as other Cubans who were disappointed by Castro’s political and economic systems as well as his strong-arm tactics) took refuge in large numbers in Florida and were ready to counter the FPCC on all fronts––with the support of intelligence forces. Violence among Cubans ensued: riots, intimidation, vandalism directed at FPCC sympathizers were the order of the day. Hosting chapters in the deep south became perilous, with strong anti-Castro sentiment coming from Latinos, business, government, intelligence and Americans from all walks of life.

“An organization formed in rebellion at this time, against the Castro regime. It called itself the Cuban Front. The group was made up of Cuban exiles and residents, which at this early date of disaffection with Castro, was composed primarily of Batista supporters. Since Cuba and the United States had by early 1961 experienced two years of deteriorating diplomatic relations, the Cuban Front’s strategy was to raise the specter of communism coming to Cuba.” One violent confrontation called the Marti Park Incident featured CRC leader Sergio Arcacha Smith, who entered Oswald’s universe in 1963.

The Bay of Pigs invasion commenced on April 17, 1961, and FPCC chapters organized protests against the U.S. action. Five days before the invasion, Tampa chapter leader V.T. Lee wrote a letter to the Tampa Tribune deriding both the Tampa daily and the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, which was investigating the organization. His letter lambasted Senators Thomas Dodd and James 0. Eastland, whose strident anti-communism began accusations that the FPCC was run by a foreign government.

On April 22, 1961, when FPCC-led public protests against the Bay of Pigs operation became prevalent on a daily basis, the Kennedy administration’s National Security Council passed National Security Action Memo [NSAM] 45. This memo ordered the Attorney General and the Director of Central Intelligence to “examine the possibility of stepping up coverage of Castro activities in the United States.” On April 27, 1961, J. Edgar Hoover issued a general order for FBI agents to report on pro-Castro agitation. Hoover noted that the Fair Play for Cuba Committee’s actions showed the capacity of a national group organization to mobilize its efforts.

Florida Congressman William C. Cramer testified on April 3, 1963. A primary subject was, in the words of the Senate Committee, “the flow of subversives through the open door of subversion, the Cuban Embassy in Mexico City, by way of Cubana Airlines.’’

For the Tampa FPCC, in large part this meant that the Florida Legislative Investigative Committee [aka––Florida Johns Committee] became involved in investigating the activities of the pro-Castro group. Its investigation of the pro-Castro 26th of July Movement and Fair Play for Cuba Committee began in 1959 and continued into 1964.

Local police intelligence unit “red squads” and state investigative committees filled the anti-Communist void in the post-McCarthy era. Florida’s Johns Committee had a counterpart in Louisiana, which was the Louisiana Un-American Activities Committee [LUAC].

The following passage by DeBenedictis explains the degree of FBI infiltration of an FPCC chapter, and the stunningly high number of informants per FPCC meeting attendee ratio.

A January 30, 1964, FBI report told of meetings the pro-Castro group had at the Tampa residence of Christine and Manuel Amor. Information about this meeting came from October 13, 1963, reports by FBI Special Agents Charles C. Capehart and Fredrick A. Slight. This data was gathered by taking down automobile license plate numbers registered to individuals in attendance. Eight cars were at the Amor residence. An FBI informant inside reported that a meeting cancellation notice had been sent to members, but several still showed up. Slide presentations and a tape recording of V.T. Lee’s Cuba trip were planned on this October date. Background reports provided data on FPCC members past affiliations with the Communist and Proletarian Parties. Jose Alvarez, who in June 1962 was elected the organization’s financial secretary, was identified by TP T-7 as a Communist Party member in Tampa in 1943. Other members, at late 1963 FPCC meetings, were listed as protestors and supporters of radical causes. Among these causes were opposition to the McCarran Act, and support of Cuba’s right to have Soviet missile stations. In addition, these members had links to the Communist Party in northern cities. FPCC informants were given the cryptonyms TP T-1 through TP T-11. Among them was TP T-2, who was identified as M. Miller, Superintendent of Mails at Ybor City’s post office. The FBI’s mail surveillance program complemented the CIA’s HT/LINGUAL mail opening program. FBI agents relied extensively on informants in the Tampa FPCC.

The key with Tampa is that it served as a model for Oswald’s agitation activities as well as FPCC countering strategies for many of the people Oswald would network with in New Orleans.

The FPCC in New Orleans

At least three city police intelligence units kept files and conducted surveillance on the Tampa FPCC. These included Miami, Tampa, and New Orleans. In addition, the police units also cooperated with each other and with the U.S. Senate Committee investigating the organization.14

Perhaps the most interesting of the police intelligence correspondence is the one between the Tampa Police Intelligence Unit and its New Orleans counterpart. The NOPD Intelligence Unit collected data about the FPCC from March to September 1961 from newspaper articles. In 1962 this changed when the NOPIU initiated a chain of correspondence with the TPIU. Sgt. J.S. de Ia Llana, supervisor of the TPIU, replying to a December 1962 information request on the Tampa Fair Play for Cuba Committee chapter, informed P. J. Trosclair (NOPIU): “The Tampa Chapter (of the FPCC) is very active in Tampa, these members hold secret meetings and distribute various types of literature. Also, movies are shown. Enclosed are some of the circulars which are distributed. This unit maintains a current file on the local chapter and its members.” The Tampa PD Intelligence Unit enclosed several circulars for its NOPD counterpart, and promised them its full cooperation.15

Early in 1963, the Tampa PD would write to New Orleans, giving them information about a Dr. James Dombrowski, a left-wing activist in New Orleans, claiming that he was an active FPCC member. The NOPD investigation of the FPCC collected a copy of Tampa Fair Play; a list of 202 travelers to Cuba, which can also be found in FBI files, and Florida Johns Committee files. Also included are the pre-Kennedy assassination arrest records and post-assassination warnings on Lee Harvey Oswald. For the NOPD, their late-1962-initiated correspondence to Tampa was odd since New Orleans had no known FPCC chapter in late 1962 and early 1963. Also unusual was the NOPD inquiry to Tampa about FPCC activity in New Orleans!

Oswald and the FPCC in Dallas

According to an FBI report, there is evidence that Oswald agitated for the FPCC in Dallas before moving to New Orleans. Dallas confidential informant T-2 advised that Lee H. Oswald of Dallas, Texas, was in contact with the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. According to T-2, Oswald had a placard around his neck reading, “Hands off Cuba Viva Fidel.”

The following day (April 19), Oswald wrote to the FPCC in New York and said:

I do not like to ask for something for nothing but I am unemployed. Since I am unemployed, I stood yesterday for the first time in my life. with a placard around my neck. passing out Fair Play for Cuba pamphlets, etc. I only had 15 or so. In 40 minutes they were all gone. I was cursed as well as praised by some. My homemake [sic] placard said: ‘Hands OFF CUBA! V IVA Fidel’ I now ask for 40 or (50) more of the fine, basic pamplets-14. Sincerely, Lee H. Oswald16

The following lead merits investigation. One of the Cuban exiles who was cursing during the so-called skirmish involving Oswald and Carlos Bringuier was Celso Hernandez, who may have met Oswald before. According to Bill Simpich’s research, the CIA examined Celso Hernandez as a Castro penetration agent. There is an intriguing report of FPCC member Oswald being arrested with Celso Hernandez in New Orleans in late 1962. The ID of Hernandez was made years later and is admittedly shaky. The ID of Oswald is more substantive, as he identified himself to the police as an FPCC member––but he was living in the Dallas area. The story is that the two men were picked up at the lakefront in Celso’s work truck, owned by an electronics firm that was Celso’s employer.17

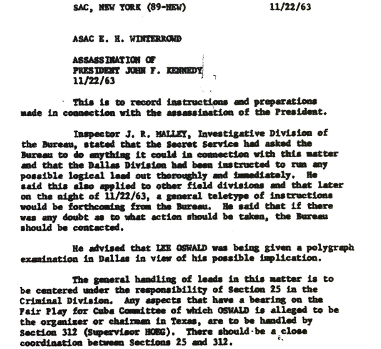

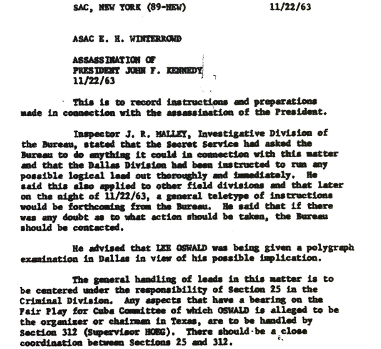

FBI agency file number 97-2229-7 even states that Oswald was the FPCC organizer and chairman in TEXAS!

(Note: also explosive in this document is the statement that Oswald was being polygraphed on November 22––sounds like another offshoot, sigh!)

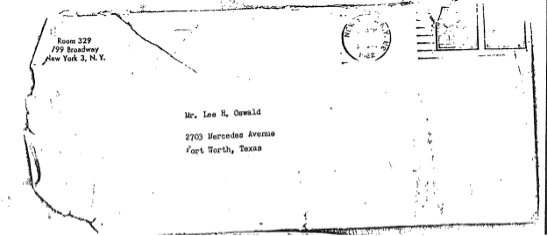

Oswald’s first attempt at interacting with the FPCC may have been as early as late summer 1962, when the head of the FPCC at the time, Richard Gibson, responded to a request for information from a Lee Bowmont from Fort Worth, Texas. Gibson felt he may have been in a group of three Trotskyites he had met shortly after.18

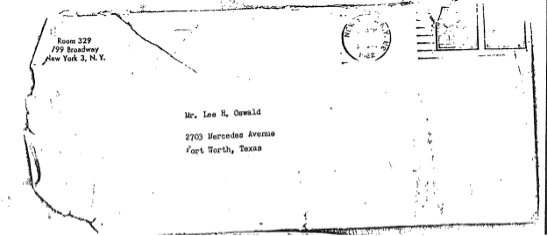

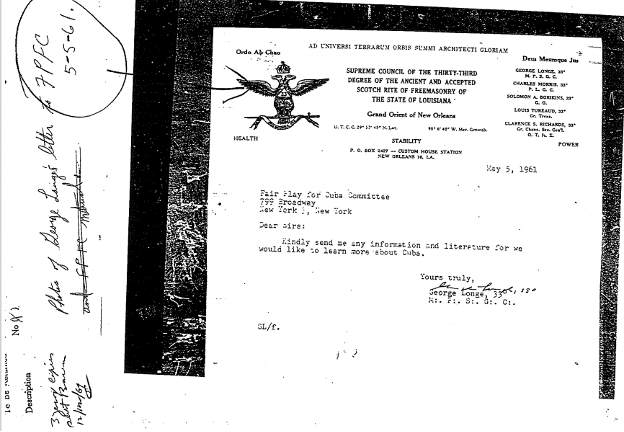

And then we have the following mind-boggling correspondence(s) courtesy of Malcolm Blunt:

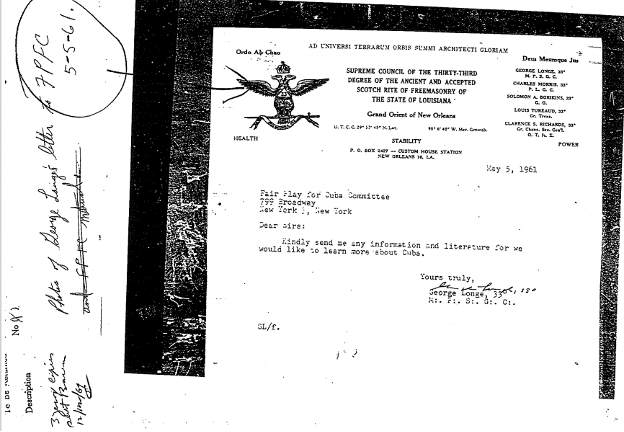

This envelope, with the FPCC return address, as it stands is difficult to analyze because of the unclear postmark and its content has not been revealed as far as I know (which would once again represent obstruction of justice if this were the case). However, we do know Oswald lived at the above address from about July to October of 1962. This confirms that Oswald/FPCC relations began clearly before 1963. The following May 5, 1961 letter is food for thought:

It was not only Oswald who was interested in the FPCC before he went to New Orleans; others from the Big Easy were gathering information. Guy Banister was also a member of the Scotch Rite19 which figures on the letterhead. What on earth is this organization doing corresponding with the FPCC in 1961?

Oswald and FPCC Worst Practices

Location, Location, Location!

As we have seen by chronicling the demise of the FPCC, Oswald’s sense of timing was horrendous when he launched the New Orleans chapter in the summer of 1963. His choice for a location was even worse.

The two most dangerous places to open chapters in the U.S. at the time were probably Miami and New Orleans. Dallas would not have been far behind. New Orleans perhaps stood out as the worst because of its dependence on North-South trade. Its proximity to Cuba caused many sleepless nights during the October 1962 missile crisis. V.T. Lee had urged Oswald to avoid New Orleans.

When the HSCA published its completed Final Report in 1979, it showed two areas related to the FPCC that the Warren Commission failed to investigate adequately. One overlooked area was the identity of occupants at the address Oswald used for his FPCC literature distribution. The address 544 Camp Street appeared on materials that Oswald was handing out. This address was the New Orleans Newman Building. The Warren Report stated that, at an earlier date, the building was occupied by an anti-Castro group, but the name was not revealed in the final report. Later it was found to be the Cuban Revolutionary Council. Another resident of the Newman Building was the private detective agency of Guy Banister. He also was not mentioned in the Warren Report. Banister was the retired FBI Special Agent in Charge of the Chicago FBI field office. After his FBI retirement in the mid-1950s, he moved to New Orleans and helped set up that city’s police intelligence unit. Guy Banister, a staunch anti-communist, continued his anti-subversion work well after his official ties with the FBI were severed. The HSCA determined in their investigation that in 1961 Banister and Sergio Arcacha Smith of the CRC were working together in the anti-Castro cause.20

The 544 Camp Street address, which Oswald foolishly stamped on some of his handouts, was also surrounded by intelligence organizations, including the ONI, CIA, Secret Service and the FBI.

The HSCA did take a closer look at the Camp Street enigma. Here were some of the findings:

(467) During the course of that investigation, however, the Secret Service received information that an office in the Newman Building had been rented to the Cuban Revolutionary Council from October 1961 through February 1962.

(466) The investigation of a possible connection between Oswald and the 544 Camp Street address was closed. The Warren Commission findings concurred with the Secret Service report that no additional evidence had been found to indicate Oswald ever maintained an office at the 544 Camp Street address.

(469) The committee investigated the possibility of a connection between Oswald and 544 Camp Street and developed evidence pointing to a different result.

(482) The overall investigation of the 544 Camp Street issue at the time of the assassination was not thorough. It is not surprising, then, that significant links were never discovered during the original investigation. Banister was involved in anti-Communist activities after his separation from the FBI and testified before various investigating bodies about the dangers of communism. Early in 1961, Banister helped draw up a charter for the Friends of Democratic Cuba, an organization set up as the fundraising arm of Sergio Arcacha Smith’s branch of the Cuban Revolutionary Council.

(489) The long-standing relationship of Ferrie and Banister is significant since Ferrie became a suspect soon after it occurred.

(491) Witnesses interviewed by the committee indicate Banister was aware of Oswald and his Fair Play for Cuba Committee before the assassination. Banister’s brother, Ross Banister, who is employed by the Louisiana State Police, told the committee that his brother had mentioned seeing Oswald hand out Fair Play for Cuba literature on one occasion.

(492) Ivan F. “Bill” Nitschke, a friend and business associate and former FBI agent, corroborates that Banister was cognizant of Oswald’s leaflet distributing.

(494) Delphine Roberts, Banister’s long-time friend and secretary, stated to the committee that Banister had become extremely angry with James Arthus and Sam Newman over Oswald’s use of the 544 Camp Street address on his handbills.

(495) The committee questioned Sam Newman regarding Roberts’ allegation. Newman could not recall ever seeing Oswald or renting space, to him … Newman theorized that if Oswald was using the 544 Camp Street address and had any link to the building, it would have been through a connection to the Cubans.

Roberts claimed Banister had an extensive file on Communists and fellow travelers, including one on Lee Harvey Oswald, which was kept out of the original files because Banister “never got around to assigning a number to it.”

(514) Significant to the argument that Oswald and Ferrie were associated in 1963 is evidence of prior association in 1955 when Ferrie was captain of a Civil Air Patrol squadron and Oswald a young cadet. This pupil-teacher relationship could have greatly facilitated their reacquaintance and Ferrie’s noted ability to influence others could have been used with Oswald.

(515) D. Ferrie’s experience with the underground activities of the Cuban exile movement and as a private investigator for Carlos Marcello and Guy Banister might have made him a good candidate to participate in a conspiracy plot. He may not have known what was to be the outcome of his actions, but once the assassination had been successfully completed and his own name cleared, Ferrie would have had no reason to reveal his knowledge of the plot.

On page 145 of its final report, the HSCA states that “it was inclined to believe that Oswald was in Clinton, August – early September 1963, and that he was in the company of David Ferrie, if not Clay Shaw. The Committee was puzzled by Oswald’s apparent association with David Ferrie, a person whose anti-Castro sentiments were so distant from those of Oswald, the Fair Play for Cuba Committee campaigner.”

Research since this very accusatory report has only re-enforced this conclusion. We now know for certain that Clay Shaw was a well-paid CIA asset, something that he vehemently denied during the Garrison inquiry. He was also using the alias Clay Bertrand and that he was seen in the company of Oswald in Clinton.

Birds of a Feather

If Oswald’s sense of timing and choice of location for opening an FPCC chapter were awful, his networking strategies were catastrophic … if you believe he was serious about promoting Fair Play for Cuba.

Jim Garrison had already pointed out how Oswald’s hobnobbing with White Russians in Dallas was diametrically opposed to his supposed pro-Marxist credo. His universe of contacts in New Orleans was even worse––unless he was involved in something else, like infiltrating pro- and anti-Castro groups to help the FBI in their oversight objectives. Let us highlight a few (for a more in-depth coverage of Oswald’s contacts read this author’s article Oswald’s Intelligence Connections: How Richard Schweiker clashes with Fake History):

David Ferrie

|

| David Ferrie |

Oswald’s first intel connection is one of the most important for confirming Schweiker’s assertion. David Ferrie plays an important role in Oswald’s fate during two phases of Oswald’s short life. In 1955, both Ferrie and Oswald were members of the Louisiana Civil Air Patrol where Ferrie taught, among other things, aviation. Ferrie later became a contract CIA agent flying bombing missions over Cuba. During the summer of 1963, Ferrie and Oswald linked up once again at 544 Camp Street. During this period, Ferrie was frequently seen in the building and elsewhere, in the company of Banister, CIA agent Clay Shaw, the CIA-connected Sergio Arcacha Smith, Oswald and others of this ilk who became key suspects in the Garrison investigation.

Kerry Thornley

|

| Kerry Thornley |

When Oswald was stationed back to California in 1959, Thornley wrote a book about him before the assassination called The Idle Warriors, and then another in 1965. In the summer of 1963, Thornley popped backed into the picture in New Orleans where several witnesses saw him with Oswald either in public or at Oswald’s apartment. There is evidence that Thornley picked up Fair Play for Cuba flyers for Oswald. An FBI memo states that Thornley and Oswald went to Mexico together. And despite preliminary denials, he eventually admitted links to David Ferrie, Guy Banister, Carlos Bringuier and Ed Butler.

Victor Thomas Vicente

When Lee Oswald wrote his first letter to the Fair Play for Cuba Committee HQ in New York in April 1963, he asked for “forty to fifty” free copies of a 40-page pamphlet. The author of the pamphlets, Corliss Lamont, turned out to be holding a receipt for 45 of these pamphlets from the CIA Acquisitions Division. These pamphlets were mailed to Oswald by FPCC National Chapter worker Victor Thomas Vicente. Vicente was a key informant for both the CIA and the FBI’s New York office.

John Martino

|

| John Martino |

Martino showed pre-knowledge of the assassination and also admitted observing Oswald during the summer of 1963. Martino certainly did have CIA connections in 1963, primarily to David Morales and Rip Robertson.

William Monaghan and Dante Marichini

During the summer of 1963 in New Orleans, Oswald gained employment at the Reilly Coffee Company, an organization of interest because of its links to Caribbean anti-communist politics. The Reilly brothers backed Ed Butler’s INCA (the CIA-linked Information Council of the Americas, which factors heavily in Oswald’s later Marxist PR activities) and the CRC (Cuban Revolutionary Council).

|

| Reilly Coffee Co |

William Monaghan was the V.P. of Finance there who ended up firing Oswald. He was also an ex-FBI agent. He was listed as a charter member of INCA in a 1962 bulletin. Other employees there of interest to researchers included four of Oswald’s co-workers who joined NASA during the summer of 1963. Dante Marichini, who was a friend of David Ferrie’s and the neighbor of Clay Shaw, was one of these.

Guy Banister

|

| Guy Banister |

What emerges from all we know about 544 Camp Street is that Oswald was assisting Banister, a known communist hunter, in identifying Castro-sympathizers and that Banister was deeply involved in activities supplying weapons to anti-Castro groups like Alpha 66––a key organization of interest in the assassination.

Clay Shaw

|

| Clay Shaw |

Thanks to Jim Garrison, we were introduced to a key person of interest in Clay Shaw. The HSCA investigation concluded that New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison and his office ”had established an association of an undetermined nature between Ferrie, a suspect in the assassination of President Kennedy, and Clay Shaw and Lee Harvey Oswald.”

In Destiny Betrayed, Jim DiEugenio underscores other Shaw links with the CRC and with Banister, CIA-cleared doctor Alton Ochsner, and Ed Butler, who are all connected to the Information Council of the Americas, which appears to have played a role in the sheep-dipping of Oswald (see Ed Butler). He also shows that Shaw was cleared for a project called QK/ENCHANT during the Garrison investigation. Howard Hunt also belonged to this project, which was part of the CIA’s Domestic Operations Division, according to CIA insider Victor Marchetti.

William Gaudet

|

| William Gaudet |

Gaudet had worked for the CIA before he crossed paths with Oswald. He most likely continued freelancing for it. He worked virtually rent-free out of Clay Shaw’s International Trade Mart. It seems plausible that Gaudet played a part in monitoring Oswald, perhaps for the benefit of Shaw.

Dean Andrews

|

| Dean Andrews |

Lawyer Dean Andrews was called by Shaw, under the pseudonym Clay Bertrand, and given instructions to represent Oswald, as told by Garrison in his famous interview with Playboy.

Sergio Arcacha Smith

|

| Sergio Arcacha Smith |

The CIA selected him to be a key leader of Cuban exiles as a representative of the Cuban Revolutionary Council. That group was created by Howard Hunt as an umbrella organization of many Cuban exile groups such as Alpha 66 and the DRE. The FDC was allegedly organized for his benefit, and it borrowed Oswald’s name when he was in Russia. It is in this role that he associated closely with Clay Shaw, Guy Banister, David Ferrie and Doctor Alton Ochsner. Gordon Novel claims that David Phillips participated in at least one meeting where Smith and Banister were in attendance.

At the time of the working relationship between Banister and CRC leader Sergio Arcacha Smith, the CRC became involved in Tampa’s Marti Park demonstrations against the FPCC. (Frank S. DeBenedictis thesis).

Carlos Bringuier, Carlos Quiroga, Celso Hernandez and Frank Bartes

|

| Carlos Bringuier |

Bringuier was part of the DRE, a militant right-wing, anti-Communist, anti-Castro, anti-Kennedy group. Bringuier, based in New Orleans, was placed in charge of DRE publicity and propaganda. According to Bringuier, the following summarizes his strange encounters with Oswald:

On August 9, 1963, Oswald, while leafleting FPCC flyers on Canal Street, drew the ire of Bringuier and his Cuban associates Celso Hernandez and Miguel Cruz. Bringuier did the swinging while Oswald tried to block his blows. Oswald was then interviewed on a Bill Stuckey show along with Bringuier where his Marxist and FPCC credentials were discussed for all to hear.

According to E. Howard Hunt, the DRE was started by David Phillips, who is the CIA career employee with the most links with Oswald. The DRE was eventually overseen in 1963 by George Joannides, who helped sabotage the HSCA investigation.

|

Arcacha Smith, Manuel Gil,

& Carlos Quiroga |

A Jim Garrison polygraphed interrogation of Quiroga, plus other research, proved that Quiroga knew Banister and Sergio Arcacha Smith, had met Oswald more than once, and had supplied Oswald with Fair Play for Cuba literature on the orders of Carlos Bringuier. One of the Cuban exiles arrested during the so-called skirmish was Celso Hernandez, who may have met Oswald before. According to Bill Simpich’s research, the CIA examined Celso Hernandez as a Castro penetration agent.

While Oswald and Bringuier were in court after their altercation, a sympathizer and friend of Bringuier’s, Frank Bartes, showed up to offer moral support. This Cuban exile went on to conduct anti-Castro press relations. Bartes followed Smith as the CRC leader in New Orleans based in the Newman building with Banister. In 1993, the ARRB released files confirming that Bartes was an informant for the FBI agent who just happened to be monitoring Oswald: Warren DeBrueys.

Jesse Core

Core was Clay Shaw’s right-hand man who was present during the incident on Canal Street and Oswald’s leafleting in front of the Trade Mart. He contacted Shaw’s friends at WDSU TV. He also is the one who warned his team about Oswald’s blunder of placing Banister’s address on some of the literature he was handing out. Jesse Core’s reports about Oswald made their way to intelligence outfits.

John Quigley and Warren DeBrueys

|

| Warren DeBrueys |

After the altercation with Bringuier, while under arrest, Oswald made a bizarre request. He asked to see an FBI agent. The FBI sent agent John Quigley, who spent somewhere between 90 minutes and three hours with Oswald. It’s safe to say that they were not discussing Bringuier simply being mean to the alleged communist. Quigley stated that Martello told him that Oswald wanted to pass on information about the FPCC to him. Joan Mellen’s research finds that Oswald actually asked specifically for Warren DeBrueys. DeBrueys, who ran Bartes as an informant, would further nail down the real reason Oswald started an FPCC chapter in a hostile place like New Orleans. William Walter, an employee at the New Orleans FBI office, claimed to have seen an FBI informant file on Oswald with DeBrueys’ name on it.

Arnesto Rodriguez and family

Before his approach to Bringuier, Oswald had contacted the head of a local language school, Arnesto Rodriguez Jr., expressing an interest in learning Spanish. One of Arnesto’s closest associates in New Orleans was Carlos Bringuier, and both men acted as sources for the FBI (Arnesto aka Ernesto was assigned FBI source number 1213 S).

The father of the Rodriguez family, Arnesto Napoleon Rodriguez Gonzales, had his own intelligence connections, having worked for the Office of Naval Intelligence during World War II; he had also served as an on-island source for the CIA before leaving Cuba. In terms of Lee Oswald’s being known to JFK conspirators, the most important point is that Arnesto’s father and Arnesto Jr. were both in routine touch with a relative in Miami, a CIA officer deep within JM/WAVE intelligence operations. That individual (son to Arnesto Sr; brother to Arnesto Jr.) was Emilio Americo Rodriguez Casanova (crypt AMIRE-1). Emilio was a close friend to both David Morales and Tony Sforza as well as a number of other SAS and JM/WAVE officers. He had also worked with, and appears to have been in contact with, David Phillips in 1963.21

Orestes Peña, Joseph Oster, David Smith, and Wendell Roache

|

| Orestes Peña |

Curiously, the evidence that Oswald collaborated with Customs is stronger than with almost any other agency. Cuban exile Orestes Peña testified that he saw Oswald chatting on a regular basis with FBI Cuban specialist Warren DeBrueys, David Smith at Customs, and Wendell Roache at INS. Peña told the Church Committee that Oswald was employed by Customs. Informant Joseph Oster went farther, saying that Oswald’s handler was David Smith at Customs. Church Committee staff members knew that David Smith “was involved in CIA operations.” Orestes Peña’s handler Warren DeBrueys admitted he knew David Smith.

Ed Butler and Bill Stuckey

|

| Butler & Bringuier |

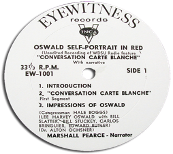

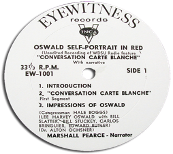

The Canal Street incident led to Oswald being part of a debate on WDSU reporter Bill Stuckey’s weekly radio program called Latin Listening Post. Later, Butler and Carlos Bringuier were also invited to debate Oswald about his Marxist views on a show called Conversation Carte Blanche.

To fully comprehend the significance of Oswald’s media exposure during his debate with Carlos Bringuier on WSDU, it is critical to have some insights on Ed Butler and INCA as well as Bill Stuckey and WSDU. These were dissected by Jim DiEugenio22:

INCA was, in essence, a propaganda mill that had as its targets Central and South America, and the Caribbean. It would create broadcasts, called Truth Tapes, which would be recycled through those areas and, domestically, stage rallies and fund raisers to both energize its base and collect funds to redouble its efforts. By this time, as Carpenter and others point out, Butler was now in communication with people like Charles Cabell, Deputy Director of the CIA, and Ed Lansdale, the legendary psy-ops master within the Agency who was shifting his focus from Vietnam to Cuba. These contacts helped him get access to Cuban refugees whom he featured on these tapes. Declassified documents reveal the Agency helped distribute the tapes to about 50 stations in South America by 1963. There is some evidence that the CIA furnished Butler with films of Cuban exile training camps and that he was in contact with E. Howard Hunt––under one of his aliases––who supervised these exiles in New Orleans. Some of the local elite who joined or helped INCA would later figure in the Oswald story e.g. Eustis Reilly of Reilly Coffee Company, where Oswald worked; Edgar Stern who owned the local NBC station WDSU where Oswald was to appear; and Alberto Fowler, a friend of Shaw’s; plus future Warren Commissioner Hale Boggs who helped INCA get tax-exempt status. Butler also began to befriend ground-level operators in the CIA’s anti-Castro effort like David Ferrie, Oswald’s friend in New Orleans; Sergio Arcacha Smith, one of Hunt’s prime agents in New Orleans; and Gordon Novel, who worked with Banister, Smith and apparently, David Phillips, on an aborted telethon for the exiles.

Two other acquaintances of Butler were Bill Stuckey, a broadcast and print reporter, and Carlos Bringuier, a CIA operative in the Cuban exile community and leader of the DRE, one of its most important groups in New Orleans.

Stuckey claimed that his show helped destroy the FPCC in New Orleans. It is during this show that Oswald let slip that he was under the protection of the government while in Russia.

So, as we can see, the arrival of Oswald in New Orleans, his behavior and his network were very closely linked to the demise of the FPCC and his own tragic fall, as well as a ploy to blame Castro.

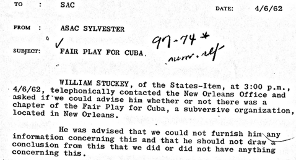

His short stint in the Big Easy was not only a godsend for right-wing fanatics; it was planned and welcomed. FBI files discovered by Malcolm Blunt, as well as Stuckey’s testimony to the Warren Commission, confirm that the radio host was making inquiries about whether or not the FPCC was present in New Orleans as early as 1961. In other words, Stuckey was not just a free-lance journalist.

|

INCA WDSU

“Conversation Carte Blanche” |

Both Butler and Stuckey were briefed in advance about Oswald’s defection to Russia: Stuckey by the FBI, Butler by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Therefore, they were able to ambush Oswald and expose him as a Soviet defector, which compromised his debate position as one who desired “fair play” for Cuba. The records of this show were used immediately after the assassination (through Butler and Bringuier) to paint Oswald as the lone-nut Marxist. In fact, Butler was flown up to Washington within 24 hours to talk to the leaders of the HUAC.

According to author Ed Haslam, Butler also became the secret custodian of Banister’s files years after his death.23

see Part 2

Notes

1 AEBALCONY_0005.pdf (cia.gov).

2 Barry Sheppard, The Party, p. 83.

3 Sheppard, The Party, p. 103.

4 Church Report, p. 211, Section: “Using Covert Action to Disrupt and Discredit Domestic Groups.”

5 Brian Glick, War at Home.

6 See n. 13 below.

7 Newman, Oswald and the CIA, location 1329, Kindle.

8 Newman, location 3122.

9 FBI report (CR-109-12 210-2990).

10 FBI report (CR-109-12 210-2990).

11 FBI document James Kennedy Report 11/29/1963.

12 FBI file 124-10324-10098.

13 Frank S. DeBenedictis, Cold War comes to Ybor City: Tampa Bay’s chapter of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (Ph.D. diss., Florida Atlantic University, 2002).

14 DeBenedictis, Cold War comes to Ybor City.

15 DeBenedictis, Cold War comes to Ybor City.

16 John Armstrong, Harvey & Lee, p. 542.

17 https://www.opednews.com/populum/page.php?f=THE-JFK-CASE–THE-TWELVE-by-Bill-Simpich-120825-173.html.

18 CIA file, NBR 89970 Dec 18, 1963.

19 William Guy Banister (1901-1964) – Find A Grave Memorial.

20 DeBenedictis, Cold War comes to Ybor City.

21 Hancock, Tipping Point, part 4, “Oswald in Play.”

22 James DiEugenio, “Ed Butler: Expert in Propaganda and Psychological Warfare“ (2004).

23 Haslam, Dr. Mary’s Monkey, pp. 161-165.