By now, I think it is safe to say that everyone is kind of sick of discussing the 2016 election season. However nauseating it may have been, it proved to be unprecedented and monumental in various ways. Unprecedented, for example, in the fact that the two major party candidates were the most disliked in modern political history. The Republican candidate, now President-elect, who touts himself as a good businessman yet probably couldn’t tell you the difference between Keynes and Marx, has run perhaps the most hate-filled, deplorable campaign in recent memory. He often speaks of running the country like a business and harps on immigration as one of the major problems facing this country. Yet he never discusses substantive issues in detail (for example, the tens of millions of poverty- and hunger-stricken children living in the United States alone), and frequently demonstrates a poor grasp of them (such as the nuclear triad). In fact, he compulsively prevaricates and can’t seem to string two cohesive sentences together. Therefore it is hard in many cases to see where he actually stands. (For a revealing example of this, watch this clip.)

The former Democratic candidate, on the other hand, bears a resemblance to an Eisenhower Republican. She is an intelligent and experienced politician full of contradictions. She was certainly preferable to Trump on domestic issues, e.g., women’s rights, race, and overall economic policy—not to mention global scientific matters like climate change. Nevertheless, there are serious problems with Hillary Clinton’s record. While Trump compulsively exaggerates and prevaricates, Hillary Clinton is not the epitome of honesty or integrity either. Up until 2013, she didn’t support same-sex marriage, yet got defensive and lied about the strength of her record on this issue. 1 Despite the fact that FBI Director James Comey publicly stated that classified material was indeed sent over Clinton’s unsecure server, she continued to dance around that subject as if she still didn’t know the public was privy to Comey’s statements.

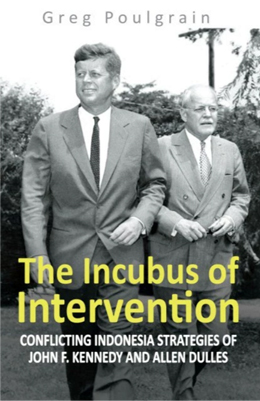

I could expand on the former Secretary of State’s flip-flopping and dishonesty over the years when it comes to problems like email security. And the disturbing fact that five people in her employ took the Fifth Amendment rather than testify before Congress in open session on the subject. However, in spite of their receiving a great deal of media attention, failings such as these are far from being her main flaw, and are, in this author’s opinion, a distraction from much deeper issues. As previously alluded to, Clinton’s foreign policy bears much more of a resemblance to the Eisenhower/Dulles brothers’ record than it does to what one might expect from someone who describes herself as taking a back seat to no-one when it comes to progressive values.

|

| Allen & John Foster Dulles |

|

| Mossadegh & Shah Pahlavi |

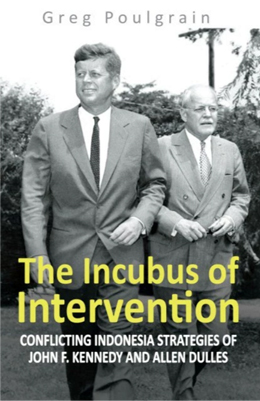

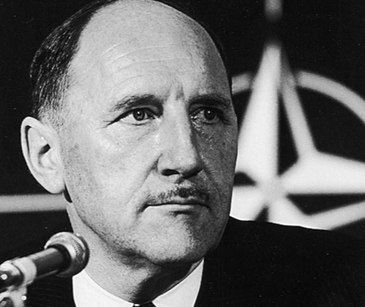

For those who might not be aware, Allen Dulles (former Director of the CIA) and his brother John Foster Dulles (former Secretary of State) essentially orchestrated foreign policy under the Eisenhower administration. They were former partners at Sullivan and Cromwell, which was the preeminent law firm for Wall Street in the fifties. Allen and Foster married global corporate interests and covert military action into a well-oiled machine that promoted coups, assassinations and the blood-soaked destruction of democracies around the world. After Iran’s democratically elected leader Mohammed Mossadegh vowed to nationalize his country’s oil and petroleum resources, the Dulles brothers—who represented Rockefeller interests like Standard Oil— designed a phony indigenous overthrow that installed the corporately complicit Reza Shah Pahlavi into power in 1953. His brutal and repressive reign lasted until 1979, and his downfall provoked a fundamentalist Islamic revolution in Iran.

|

| Arbenz centennial (2013) |

|

| Castillo Armas (with Nixon) |

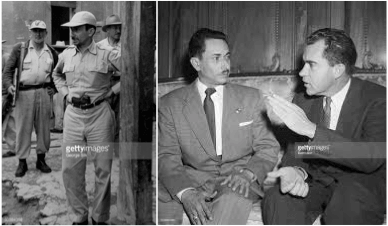

In 1954, the Dulles brothers were at it again in Guatemala with operation PBSUCCESS. Jacobo Arbenz, the labor-friendly and democratically elected leader of the country, was going toe to toe with other corporate interests such as the Rockefeller/Sullivan & Cromwell associated company United Fruit. Arbenz was pushing for reform that sought to curtail the neo-colonial power of United Fruit by providing more in resources for the people of Guatemala. To the Dulles brothers and other Wall Street types with vested interests, this was unacceptable and was to be depicted as nothing short of communism. Arbenz was ousted from the country in what was largely a psychological warfare operation. He was replaced with a ruthless dictator by the name of Castillo Armas. The CIA provided the Armas regime with “death lists” of all Arbenz government members and sympathizers, and through the decades that followed, tens of thousands of people either were brutally killed or went missing at the hands of the dictatorship. 2 This constant state of upheaval, terror and violence did not subside until a United Nations resolution took hold in 1996.

II

Hillary Clinton, whether she knows it or not—and it’s a big stretch to say that she doesn’t—has advocated for the same interventionist foreign policy machine created by the likes of the Dulles brothers. There are at least three major areas of foreign affairs in which she resembles the Dulles brothers more than Trump does: 1.) The Iraq War 2.) American /Russian relations 3.) American actions against Syria. In fact, she actually made Trump look Kennedyesque in this regard, no mean feat.

|

| Clinton & Kissinger |

Nowadays, Clinton refers to her vote for the Iraq War as a “mistake”, but it certainly doesn’t seem like one considering the context of her other decisions as Secretary of State. Secretary Clinton’s friendships and consultations with Henry Kissinger and Madeleine Albright raised eyebrows in progressive circles. (Click here for the Clinton/Kissinger relationship.) Kissinger’s record as Secretary of State/National Security Adviser was most certainly one of the worst in U.S. history when it came to bloody, sociopathic, interventionist policy around the globe. During the disastrous and unnecessary crisis in Vietnam, Kissinger would nonchalantly give President Nixon death tallies in the thousands regarding Vietnamese citizens as if they were some Stalinesque statistic. Kissinger then agreed to expand that war in an unprecedented way into Cambodia and Laos—and then attempted to conceal these colossal air war actions. Of course, this was a further reversal and expansion of that war, which went even beyond what Lyndon Johnson had done in the wake of JFK’s death. President Kennedy’s stated policy was to withdraw from Indochina by 1965.

|

| Salvador Allende |

|

| Augusto Pinochet |

Kissinger was also an instrumental force for the CIA coup in Chile, which ended in the death of Salvador Allende. About Allende, he allegedly stated he did not understand why the USA should stand by and let Chile go communist just because the citizenry were irresponsible enough to vote for it. (A Death in Washington, by Don Freed and Fred Landis, p. 8) The CIA overthrow of Allende led to years of brutal fascism under military dictator Augusto Pinochet.

|

| Clinton & Albright |

Madeleine Albright demonstrated similar hawkishness. (Click here for more on the Clinton/Albright relationship.) When asked about the refusal of the United States to lift UN Sanctions against Iraq and the resulting deaths of 500,000 Iraqi children, Albright stated that the deaths had been “worth it.”3 Predictably, Albright’s statement was met with stunned surprise. In May of 1998, Albright said something just as surprising. At that time, riots and demonstrations against the brutal Indonesian dictator Suharto were raging all over the archipelago; there were mock funerals being conducted, and his figure was being burned in effigy. Here was a prime opportunity for Albright and the Clinton administration to step forward and cut off relations with a despot who had looted his nation to the tune of billions of dollars. Or at the very least, join the chorus of newspapers and journals requesting he step down. What did Albright do? She asked for “more dialogue”. Even in the last two days of Suharto’s reign, when major cities were in flames, when Senators John Kerry and the late Paul Wellstone were asking the State Department to get on the right side of history, Albright chose to sit on the sidelines. (Probe Magazine, Vol. 5 No. 5, pp. 3-5)

|

| Hajji Muhammad Suharto with Nixon, Ford & Kissinger, Reagan, Bush Sr. & Bill Clinton |

In this regard, let us recall that Suharto came to power as a result of a reversal of President Kennedy’s foreign policy. Achmed Sukarno had been backed by President Kennedy throughout his first term, all the way up to his assassination. And JFK was scheduled to visit Jakarta in 1964, before the election. As opposed to the silence of Albright and Bill Clinton, after Suharto resigned, the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Center wrote a letter to his successor asking for an investigation of the role of the military in suppressing the demonstrations that led to his fall. (ibid)

During her time as Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton displayed an American imperiousness akin to the previous examples. Whether the former Secretary’s intentions in Libya truly aimed at ending what she called a “genocidal” regime under Gaddafi doesn’t really matter. She personally pushed for a NATO sanctioning of bombings in Libya. (This NATO assault in Africa followed the standard set by Albright in Kosovo in 1999, which was the first offensive attack NATO had ever performed.) The assault on Libya eventually led to the murder of Muammar Gaddafi. And that paved the way for a dangerous political power vacuum in which various elements, including Islamic extremists, are vying for power. It is safe to say that she left Libya in such a shambles that the USA had to reenter the civil war.

Clinton’s decision to arm Syrian “rebels” against Bashar al Assad has also helped create bloody conflict with no end in sight. (Click here for why this may be a strategic mistake.) Bombings occur on a daily basis, especially in areas like Aleppo, leaving tens of thousands of innocents dead. As a candidate, she wanted to establish a “no-fly zone” over Syria—much as she did in Libya. This was a euphemism for controlling the air so that American proxies could control the ground. And as many suspect, and as alluded to in the above-linked story, that likely would have led to fundamentalist dominance in Syria, resembling the endgames in Iraq and Libya. But beyond that, this would probably have ended up provoking Russia, since Russia backs Assad. (Ibid, n. 3)

|

| “Pacific Rubiales: How to get rich in a country without regulations” |

Secretary Clinton’s policy regarding Latin America, another topic avoided by the media during the last election cycle, also demonstrates knowing or unknowing complicity with colonial/imperial interests. In Colombia, for instance, a petroleum company by the name of Pacific Rubiales, which has ties to the Clinton Foundation, has been at the center of a humanitarian controversy. The fact that Pacific Rubiales is connected with the Clinton Foundation isn’t the main issue, however. The real problem is the manner in which positions were changed on Clinton’s part in exchange for contributions. During the 2008 election season, then-Senator Clinton opposed the trade deal that allowed companies like Pacific Rubiales to violate labor laws in Colombia. After becoming Secretary of State, Clinton did an about-face. As summed up by David Sirota, Andrew Perez and Matthew Cunningham-Cook:

At the same time that Clinton’s State Department was lauding Colombia’s human rights record (despite having evidence to the contrary), her family was forging a financial relationship with Pacific Rubiales, the sprawling Canadian petroleum company at the center of Colombia’s labor strife. The Clintons were also developing commercial ties with the oil giant’s founder, Canadian financier Frank Giustra, who now occupies a seat on the board of the Clinton Foundation, the family’s global philanthropic empire. The details of these financial dealings remain murky, but this much is clear: After millions of dollars were pledged by the oil company to the Clinton Foundation—supplemented by millions more from Giustra himself—Secretary Clinton abruptly changed her position on the controversial U.S.-Colombia trade pact.” 4

|

| Clinton & Zelaya (2009) |

|

Despite recent denials, the former Secretary also played a role in the 2009 coup that ousted the democratically elected and progressive human rights administration of Manuel Zelaya in Honduras. Recent editions of Clinton’s autobiography Hard Choices have been redacted to conceal the full extent of her role in the overthrow. Since the coup, and in opposition to the supposed goals of the overthrow itself, government-sponsored death squads have returned to the country, killing hundreds of citizens, including progressive activists like Berta Cáceres. Before her assassination, Cáceres berated Secretary Clinton for the role she played in overthrowing Zelaya, stating that it demonstrated the role of the United States in “meddling with our country,” and that “we warned it would be very dangerous and permit a barbarity.” 5

In addition, the U.S.-backed coup in Honduras demonstrates the ongoing trend of outsourcing when it comes to intelligence work. A private group called Creative Associates International (CAI) was involved in “determining the social networks responsible for violence in the country’s largest city,” and subcontracted work to another private entity called Caerus. A man by the name of David Kilcullen, the head of Caerus, was previously involved in a $15 million US AID program that helped determine stability in Afghanistan. Kilcullen’s associate, William Upshur, also contributed to the Honduras plans. Upshur is now working for Booz Allen Hamilton, another private company involved in U.S. intelligence funding. (Ibid, n. 5)

In his 2007 book, Tim Shorrock explained how substantial this kind of funding is. Shorrock stated that approximately 70 percent of the government’s 60-billion-dollar budget for intelligence is now subcontracted to private entities such as Booz Allen Hamilton or Science Applications International Corporation. 6

Puerto Rico, a country in the midst of a serious debt crisis, is another key topic when it comes to Clinton’s questionable foreign policy decisions. Hedge funds own much of Puerto Rico’s massive debt, and a piece of legislation, which was put forward to deal with the issue, has rightly been labeled by Bernie Sanders as a form of colonialism. The bill in question would hand over control of financial dealings to a U.S. Government Board of Regulators, which would likely strip vital social spending in Puerto Rico. The bill already imposes a $4.25 minimum wage clause for citizens under 25. While Sanders opposed this bill, Clinton supported it. 7 This may serve as no surprise, being that the former Secretary of State receives hefty sums from Wall Street institutions like Goldman Sachs, who benefit from this form of vulture capitalism. I am not asserting that Hillary Clinton is solely responsible for these foreign policy decisions, but that she has been complicit with the American Deep State that commits or is heavily involved in these operations. (An explanation of the term “Deep State” will follow.) If the results of this 2016 election, and the success of both Trump and Sanders in the primaries, teach us something, it is that we have to move away as quickly as possible from policy compromised by corporate influence if we truly want to move forward. The American public has clearly had enough with establishment politics.

III

With the election of Donald Trump, the viability of establishment politics has been seriously breached, effectively ending the age of lesser-evil voting by the proletariat. Although Hillary Clinton was the preferred candidate regarding things like domestic social issues and scientific issues, it wasn’t enough to tame the massive insurgency of citizens who were so fed up with the status quo that they would rather see the country possibly go up in flames than vote for more of the same. Nor did it inspire an overlooked independent voter base to come out and make a substantial difference in the Democratic vote. In the aftermath of this potential disaster of an election, it is our duty, as a collective, to look deeply into some troubling fundamental issues. One of these has to do with the fact that racism, xenophobia and sexism are still very much alive in this country.

I will not go so far as to label all Trump supporters as racist, homophobic or sexist. And throughout the primary/general election season, I have tried to remain receptive to their frustrations. However, I can most certainly tell you that, based on my experiences of this election season alone, these sentiments do indeed exist. During a delegate selection process for the Bernie Sanders campaign, I met and ended up having discussions with some Trump supporters. I asked them questions about why they thought Trump would make a good president, all the while disagreeing with them, but listening nonetheless. Two of the men I was speaking with were very civil, but one in particular seemed to be bursting at the seams with frustration over what he thought were the main problems with the country. While ignoring the facts I was presenting him regarding corporate welfare, this man went into relentless diatribes about why “Tacos”, his label for Hispanic people, were wreaking havoc. He exhibited no shame in expressing his distaste for other ethnicities either. During this dismaying exchange, I brought up the continued mistreatment of Native American peoples. In response, this man tried to question the severity of the atrocities committed against them and even went so far as to imply that my use of the term genocide in describing their plight was incorrect.

|

| Steve Mnuchin |

This may well serve to exemplify the hateful attitudes of mistrust and resentment that have been put under a black light during the course of this election. They’ve lingered dormant under the surface and have reached a boiling point thanks to Donald Trump. To paraphrase Bernie Sanders, Trump was able to channel the frustration of a destitute middle class and convert it into unconstructive anger. While Trump made references to how the “establishment” was a major problem, like many of his policy points, he didn’t ever describe in detail what was to be done to correct it. Instead, with his references to a wall with Mexico and to mass deportations, he encouraged the belief in his supporters that minorities were ruining the country. Yet in spite of his campaign promise to “drain the swamp”, many of the Trump cabinet appointees are among the most Establishment type figures one could imagine. For example, Steve Mnuchin, the former Goldman Sachs executive famous for foreclosures and hedge fund deals, has been appointed Secretary of Treasury.

The election of a man like Donald Trump, who can’t seem to expound any of his policies in any sort of detail and is openly demeaning towards women, people of other races, and the disabled, makes clear that we have a cancerous political system which has metastasized in large part thanks to establishment politicians beholden to corporate interests. And these politicians are wildly out of touch with the needs of the average American. This created a very wide alley that the new Trump managed to rumble through. (I say “new” because in one of the many failings of the MSM, no one bothered to explain why Trump had reversed so many of the proposals he made back in 2000, when he was going to run on the Reform Party ticket.) Some commentators have claimed there can be little doubt that there was a liberal disillusionment following President Obama’s election. Hillary Clinton could not convince enough people that she was even the “change candidate” that Obama was. Therefore, in the search for answers for why their lives weren’t improving, many citizens had to find alternate sources of information outside of corporate influenced organizations (i.e. The Republican Party, Democratic Party and the Mainstream Media), given those groups won’t admit to the public that they are subservient to the same big money interests. This explains the rise of figures like Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck, and even rightwing populist/conspiracy demagogue Alex Jones. Their collective answer is to paint minorities and welfare recipients as the principal ills of American society, all the while failing to recognize the deep connection between government policy and corporate influence. In short, this election warns us that when the real reasons behind government dysfunction are ignored and go unchallenged, one risks the upsurge of fascist sentiments. 8

In addition to reminding us of Hillary’s relationship with Kissinger, Bernie Sanders reminded a large portion of the U.S. populace about the other fundamental issue lying beneath the surface: corporate power. And Sanders could have neutralized Trump’s appeal among the shrinking working and middle classes, which the latter earned by invoking the need for tariffs and the threat of trade wars. This certainly was another reason for Trump’s popularity in the Mideast states like Wisconsin, Iowa, Michigan and Ohio, where he broke through the supposed Democratic firewall. (As to why, listen to this this segment by Michael Moore.) With Secretary of State Clinton’s and President Bill Clinton’s views on NAFTA and the Columbia Free Trade Agreement, and Hillary’s original stance on the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), she could not mount a genuine counter-offensive to Trump’s tactics in those states, for the simple reason that the Clintons were perceived as being free-traders rather than fair-traders. Thanks to their record, a Democratic presidential candidate appeared to favor a globalization policy that began decades ago with David Rockefeller—a policy that was resisted by President Kennedy. (See Donald Gibson, Battling Wall Street, p. 59)

Awareness of any problem is the first step toward fixing it. But I think we must go beyond simple awareness when it comes to confronting our nation’s collective “shadow”, as Carl Jung would have called it — meaning all the darker, repressed aspects of the unconscious that, when ignored, can result in psychological backlash. How do we get beneath the surface appearances of corporate greed (for instance, the increasing wealth inequality amongst classes, or the amount of tax money allocated to corporate subsidies)? I suggest that an exploration of our past guided by a concept that Peter Dale Scott labels “Deep Politics” can help us come to terms, in a more profound way, with the problems facing us.

This concept embraces all of the machinations occurring beneath the surface of government activity and which go unnoticed in common analysis, such as in news reports or textbooks. Or, as Scott states in his 2015 book The American Deep State, it “…involves all those political practices and arrangements, deliberate or not, which are usually repressed rather than acknowledged.”9 A “Deep Political” explanation of major world events goes beyond the ostensible or normally accepted models of cause and effect. One example of a “Deep Event” is the 1965 Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which provided a motive, or casus belli, to escalate the Vietnam War into a full-scale invasion by American ground forces. Given that President Johnson had already, in stark contrast to President Kennedy’s policy, approved the build-up of combat troops in Vietnam in 1964, all that was needed was some sort of impetus in order for United States involvement to move to the next stage. As the author describes, many of the intelligence reports received by the Johnson administration regarding this supposed incident did not signal any sort of instigation on North Vietnam’s behalf. However, those same reports were ignored in order to claim that North Vietnam had engaged in an act of war against the United States. 10

Other examples of Deep Events include the previously mentioned instances of CIA, corporate and State Department interference in the economic and governmental affairs of foreign nations. It is evident that these coups did not occur for the sake of saving other countries from the grip of communism or the reign of dictators; such would only be at best a surface explanation. The deeper explanation is that a nexus of corporate, military, paramilitary, government and, on occasion, underworld elements (viz, the workings of the Deep State) had a vested interest in the outcome. The Bush administration’s lies regarding Saddam Hussein’s alleged arsenal of “weapons of mass destruction”, presented to the American people and Congress as a reason to invade Iraq, could most certainly be classified as a Deep Event. No entities benefitted more from America’s long-term occupation of Iraq than companies like Dick Cheney’s Halliburton. KBR Inc., a Halliburton subsidiary, “was given $39.5 billion (emphasis added) in Iraq-related contracts over the past decade, with many of the deals given without any bidding from competing firms, such as a $568-million contract renewal in 2010 to provide housing, meals, water and bathroom services to soldiers, a deal that led to a Justice Department lawsuit over alleged kickbacks, as reported by Bloomberg.” 11

Included under the umbrella of Deep Politics are the major assassinations of the 1960s — those of John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Poll after poll has indicated that most Americans believe there was a conspiracy to kill President Kennedy, but even today many apparently have not reasoned beyond the fact that there is something fishy about the “official” version in order to understand this murder in its fullest context. It behooves us to inquire more deeply into this historically critical event. Before I go any further, however, let me assert here—and I do so quite confidently—that anyone who still buys into the government version of events regarding, for example, the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy, is either not looking carefully enough, or is not really familiar with the case.

IV

A suggestive point of departure for such an inquiry are the parallels between the 2016 election and that of 1968. In the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King in April of 1968, racial tensions were high and a presidential primary season was in full swing. Opposition towards the Vietnam War was strong and one candidate in particular represented the last best hope for minorities, anti-war voters, and the middle, as well as lower classes. That candidate was Robert Kennedy, and by the early morning of June 5th, it was becoming clear that he would likely be the Democratic candidate to run against Richard Nixon in the general election. Within a matter of moments of making his victory speech for the California primary, Robert Kennedy was assassinated when he walked into the kitchen pantry of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. In those moments, the Sixties ended—and so did the populist hopes and dreams for a new era.

|

| Chicago DNC 1968 |

|

| Philedelphia DNC 2016 |

The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago was attended by the protests of disillusioned voters who felt cheated out of a more liberal, populist candidate. They ended up rioting in the streets. Hubert Humphrey, who was receiving flack for not taking a strong enough stance on the situation in Vietnam, was selected as the nominee. Similarly, there were many dissatisfied delegates and voters at the 2016 Philadelphia Democratic convention. But in a tightly controlled operation, their actions were kept hidden off screen. And the threat of stripping them of their credentials was often used to suppress any protest on the convention floor. In 2016, Hillary Clinton was nominated and her candidacy helped give us Donald Trump. In 1968, the immediate result was Richard Nixon as president. But the subsequent results included the massive increase in loss of life not just in Vietnam, but also in Cambodia, and the continuing trend away from the New Deal, anti-globalist policies of John Kennedy and Franklin Roosevelt.

|

| Alger Hiss, America’s Dreyfus |

|

| Rep. Voorhis, defeated by Nixon’s smear campaign |

In fact, Nixon had been a part of the effort to purge New Deal elements from the government during the McCarthy era. Whether it was conducting hearings on men like Alger Hiss and making accusations of Soviet spycraft, or using his California Senate campaign to falsely accuse incumbent Congressman Jerry Voorhis of being a communist, Nixon contributed to the growing, exaggerated fear of communism in the United States. This fear allowed men like Allen Dulles to be seen as pragmatists in the face of supposed communist danger. Dulles’ and the CIA’s dirty deeds on behalf of corporate power were carried out under the guise of protecting the world from communism. As described in the Allen Dulles biography by David Talbot, The Devil’s Chessboard, sociologist C. Wright Mills called this mentality “crackpot realism.”12 It is ironic that Nixon ended up distrusting the CIA, the institution so closely associated with Allen Dulles, a man who had championed Nixon’s rise to power as both a congressman and senator.

Flash forward to 2016 and, once again, we witness the results of a Democratic Party choosing to ignore the populist outcry for reform, and of a government compromised by corporate coercion, one subject to the hidden workings of the Deep State. Bernie Sanders represented the New Deal aspirations of a working class tired of corporate-run politics. As revealed by Wikileaks, the upper echelons of the Democratic Party chose not to heed their voices, thereby indirectly aiding the election of Donald Trump, who offered a different and unconstructive form of populism.

|

| Pence & Reagan |

|

| Rex Tillerson |

Being that the political spectrum has shifted far to the right as compared to 1968, this year’s election results are more extreme. Donald Trump’s cabinet appointments reflect this extremist mentality; especially in his Vice Presidential pick Mike Pence — a man so out of touch with reality that he has tried to argue that women shouldn’t be working. In 1997, Pence stated that women should stay home because otherwise their kids would “get the short end of the emotional stick.” The soon to be Vice President Pence also sees LGBT rights as a sign of “societal collapse.”13 And as for Trump’s promise to “drain the swamp”, when it comes to establishment figures, it only gets worse, considering his appointment of Rex Tillerson, former CEO of ExxonMobil, as Secretary of State. Despite the fact that Trump appears to be “off the grid”, so to speak, when it comes to the political or Deep Political apparatus, his recent choices for cabinet positions are some of the worst imaginable for the populist of any ilk. In some cases he has actually leapt into the arms of the very establishment he warned his supporters against.

In the face of all this, Sanders continues to inspire his followers to remain politically active. We all need to be involved more than ever, and the Democratic/socialist senator from Vermont has always urged that true change lies in us having the courage to do things ourselves when it comes to reforming government. The more we stay involved, the less likely it will be that the momentum created by political movements will be squandered in the wake of a setback. The major setbacks of the 1960s came in the form of assassinations of inspiring political leaders. Yet even in the wake of such tragedies it is possible, indeed imperative, to find a glimmer of hope. To do so, however, requires, as this essay has been arguing, the insight afforded by a critical analysis of the past, and its continuities with the present. The touchstone for this historical understanding, I believe, lies precisely in the way the policies of President Kennedy have been consistently overturned by subsequent administrations.

V

As mentioned above, John Kennedy was not in favor of the neo-colonialist policies of the Dulles/Eisenhower era. Instead of wanting to occupy foreign nations for the sake of corporate profit, Kennedy believed strongly that the resources of such nations rightly belonged to their people, and that the right to self-determination was critical, as evident in his 1957 speech on French colonialism in Algeria.

|

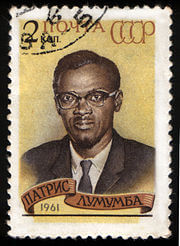

| Soviet stamp commemorating Lumumba |

|

| Nixon and Mobutu at the White House |

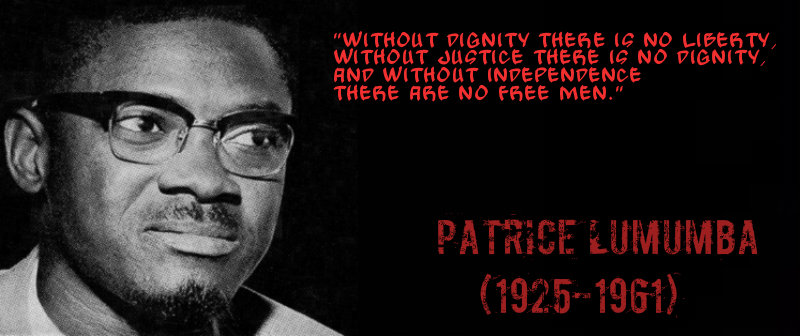

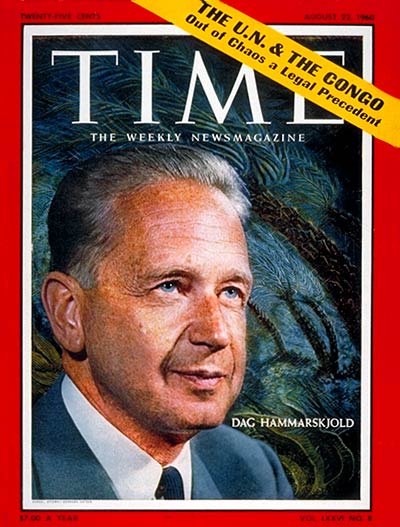

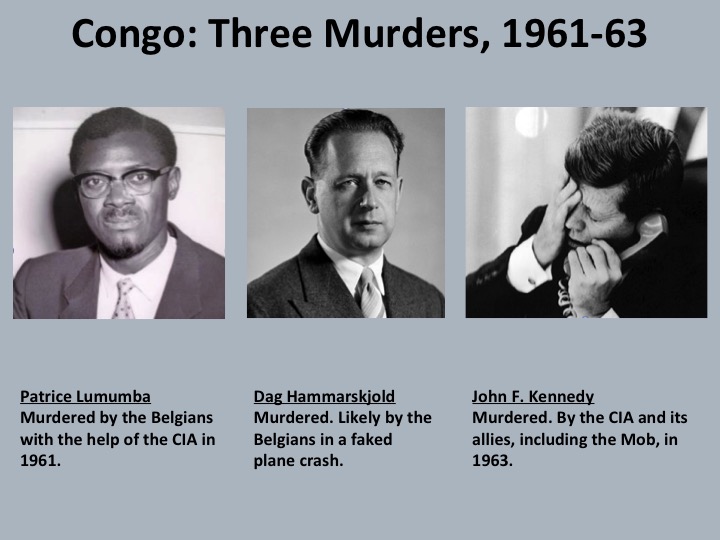

In the aftermath of a CIA-assisted coup to assassinate Patrice Lumumba, the nationalist leader of the Congo, President Kennedy fought alongside the U.N. to ensure that a nationwide coalition government was formed. Civil war was imminent as militant and corporately complicit leaders like Colonel Mobutu vied for power and promoted the secession of Katanga, the region of Congo that held vast amounts of mineral resources. JFK supported the more centrist elements of the potential coalition government and felt that the resources of Katanga didn’t belong to Belgian, U.S. or British mining interests. The President’s death ended hope for the pursuit of any stable government in Congo, along with the hope of halting widespread violence. 14 It should be noted that Nixon actually welcomed Mobutu to the White House after he took control of Congo.

|

| Sukarno at the White House |

As noted previously, President Kennedy also worked towards re-establishing a relationship with Indonesia and its leader Achmed Sukarno. This was after the Dulles brothers had been involved in attempts to overthrow the Indonesian leader. Decades earlier, it had been discovered by corporate backed explorers that certain areas in Indonesia contained extremely dense concentrations of minerals such as gold and copper. After Kennedy was killed, Sukarno was overthrown with help of the CIA in one of the bloodiest coup d’états ever recorded. Hundreds of thousands of Indonesians perished during both the overthrow, and the subsequent reign of the new leader Suharto. (James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed, Second Edition pp. 374-75) Need we add that Nixon also met with Suharto in Washington. In December of 1975, President Ford and Secretary of State Kissinger journeyed to Jakarta and gave Suharto an implicit OK to invade East Timor. This is the tradition that Hillary Clinton and her husband were involved with. For when almost every democratically elected western nation was shunning Suharto in the late nineties, Bill Clinton was still meeting with him. (Op. cit. Probe Magazine.)

President Kennedy’s policies regarding Central and South America were also a threat to corporate interests. David Rockefeller took it upon himself to publicly criticize Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress, which had been established to aid less developed nations, like those south of the United States, to become economically self-reliant. Men like Rockefeller, along with the Wall-Street-connected media (e.g.,Wall Street Journal and Time/Life) also berated the President for “undermining a strong and free economy,” and inhibiting “basic American liberties.” (14, p. 57) The Wall Street Journal flat out criticized Kennedy for being a “self-appointed enforcer of progress” (Ibid p. 66). JFK’s 1962 clash with U.S. Steel, a J.P. Morgan/Rockefeller company, provoked similar remarks.

After President Kennedy had facilitated an agreement between steel workers and their corporate executives, the latter welshed on the deal. It was assumed that the workers would agree to not have their wages increased in exchange for the price of steel also remaining static. After the agreement was reached, U.S. Steel defied the President’s wishes and undermined the hard work to reach that compromise by announcing a price increase. The corporate elite wanted Kennedy to buckle, but instead, he threatened to investigate them for price-fixing and to have his brother Bobby examine their tax returns. Begrudgingly, U.S. Steel backed off and accepted the original terms. Kennedy’s policies, both domestic and foreign, were aimed at enhancing social and economic progress. Like Alexander Hamilton, and Albert Gallatin, JFK sought to use government powers to protect the masses from corporate domination. His tax policy was aimed at channeling investment into the expansion of productive means or capital. The investment tax credit, for instance, provided incentives for business entities that enhanced their productive abilities through investment in the upkeep or updating of equipment inside the United States. (Gibson pp. 21-22) While Kennedy’s policies were focused on strengthening production and labor power, his opponents in the Morgan/Rockefeller world were focused on sheer profit.

|

| David Rockefeller & Henry Luce in 1962 |

It should serve as no surprise that the media outlets responsible for condemning the president were tied into the very corporate and political establishment entities being threatened. As described by sociologist Donald Gibson in his fine book Battling Wall Street: The Kennedy Presidency, the elite of Wall Street, media executives and certain powerful political persons or groups were so interconnected as to be inbred. Allen Dulles himself was very much involved in these circles, and had close relationships with men like Henry Luce of the Time, Life and Fortune magazine empire, along with executives or journalists at the New York Times, and the Washington Post. Operation Mockingbird, a CIA project designed to use various media outlets for propaganda, was exposed during the Church Committee hearings, revealing the collaboration of hundreds of journalists and executives at various media organizations including CBS, NBC, The New York Times, the Associated Press, Newsweek and other institutions.15)

John Kennedy wasn’t only trying to curtail corporate power with his Hamilton/Gallatin, New Deal-like economic policies. His decisions concerning military engagement abroad were greatly at odds with the hard-line Cold Warriors of his administration and the Central Intelligence Agency. Time after time, Kennedy refused to commit U.S. combat troops abroad despite the nagging insistence of his advisors. Although the President publicly accepted responsibility for the fiasco at the Bay of Pigs, privately he was livid at the CIA for deceiving him. Through materials such as inspector general Lyman Kirkpatrick’s report on the Bay of Pigs, and other declassified CIA documents, it is now evident that a major deception had occurred. The Agency had assured Kennedy that their group of anti-Castro Cuban invaders would be the spark that would set off a revolt against Fidel Castro just waiting to happen. This was not the case, and the CIA-backed Cubans were outnumbered by Castro’s forces 10 to 1. Even worse, as noted in the Kirkpatrick report, was the fact that the CIA had stocked the invading force with C-Level operatives. (2, p. 396) It was almost as if the surface level plan presented to the President was designed to fail in order to force his hand and commit the military into invading Cuba. A declassified CIA memo acknowledges the fact that securing the desired beach area in Cuba was not possible without military intervention. 16

When Kennedy refused to commit U.S. troops as the operation crumbled, he became public enemy number one in the CIA’s eyes. This sentiment that Kennedy was soft on communism, or even a communist sympathizer, augmented as he continued to back away from military intervention in other situations. The President reached an agreement with the Soviet Union to keep Laos neutral, and despite his willingness to send advisors to Vietnam, he ultimately worked to enact a policy resulting in the withdrawal of all U.S. personnel from the country. Kennedy’s assassination ended this movement toward disengagement from Saigon.

What was likely even worse to the Cold Warriors and CIA patriots during this time was the President’s attempts at détente with Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union and Cuba’s Fidel Castro. During, and in the period following, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy and Khrushchev were involved in back channel dialogue with one another. Discussion moved toward talks about détente; despite the fact that the two men’s respective countries had differing views, they agreed it was imperative, for the sake of the planet, to come to an understanding. This, along with JFK’s unwillingness to bomb Cuba during the Missile Crisis, were nothing short of traitorous to the covert and overt military power structure of the United States. In the final months of his life, the President also extended a secret olive branch toward Fidel Castro in hopes of opening a dialogue. Excited by the prospect, Castro was painfully upset when he got word of Kennedy’s assassination. Kennedy most certainly had his enemies, and was making decisions that drove a stake into the very heart of corporate, military and intelligence collusion. If he had been elected President, Bobby Kennedy was most certainly going to continue, and most likely even expand, the policies of his late brother. (ibid, pp. 25-33) Like Jack and Bobby, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X expressed opposition toward the continuation of the Vietnam War.

VI

The concept of Deep Politics may provide a helpful alternative to the term “conspiracy theory”, which has become so stigmatized and so overused as to be meaningless. Abandoning the idea of conspiracy altogether, however, risks throwing the baby out with the bath water, for it raises legitimate questions about what lurks beneath the surface of the affairs of state. The enemies that John and Robert Kennedy were facing were not some fictional or hypothetical “illuminati” group or groups. They were very real, dangerous and powerful interests, and those forces are still with us in 2016. Deep Politics does not imply that there is some singular group or set of groups that meet in secret to plot colossal calamities that affect the entire world, but rather that the events themselves arise from the milieu(s) created by a congruence of unaccountable, supra-constitutional, covert, corporate and illegal interests, sometimes operating in a dialectical manner. A more recent example would be the networking of several of these interests to orchestrate the colossal Iran/Contra project.

Other writers have also described these subterranean forces using other terms. The late Fletcher Prouty called it the Secret Team. Investigative journalist Jim Hougan calls it a Shadow Government. Florida State professor Lance DeHaven Smith, with respect to its activities, coined the term “State Crime Against Democracy”, or SCAD. (Click here for his definition.) Smith wrote one of the best books about how, with the help of the MSM, these forces stole the 2000 election in Florida from Al Gore. He then wrote a book explaining how the term “conspiracy theorist” became a commonly used smear to disarm the critics of the Warren Commission. It was, in fact, the CIA which started this trend with its famous 1967 dispatch entitled “Countering Criticism of the Warren Report”. (See this review for the sordid details.)

Whether it be extralegal assassinations, unwarranted domestic surveillance, interventionist wars at the behest of corporate interests, torture or other activities of that stripe, these all in essence have their roots in the Dulles era in which covert, corporate power developed into a well-oiled and unaccountable machine running roughshod. These forces have continued to operate regardless of who is elected president, whether Democrat or Republican. (See Jim Hougan’s Secret Agenda for a trenchant analysis of the operation against Richard Nixon that came to be called Watergate.)

It is my opinion that we must come to terms with these dark or, to use James W. Douglass’ term, “unspeakable” realities. And we must do so in a holistic way if we are to take more fundamental steps toward progress as a nation. George Orwell coined the term Crime Stop to describe the psychological mechanism by which humans ignore uncomfortable or dangerous thoughts. Through discussions with people young and old, it has become evident to me that this Crime Stop mechanism is at work in the subconscious of many Americans. We need to be willing to face the darker aspects of our recent past that have been at work below the surface and percolating up into view for many years.

In a very tangible way, the refusal to face these dark forces has caused the Democratic Party to lose its way. And this diluted and uninspiring party has now given way to Donald Trump. As alluded to throughout this essay, this party has abandoned the aims and goals of the Kennedys, King and Malcolm X to the point that it now resembles the GOP more than it does the sum total of those four men. To understand what this means in stark political terms, consider the following. Today, among all fifty states, there are only 15 Democratic governors. In the last ten years, the Democrats have lost 900 state legislative seats. When Trump enters office, he will be in control of not just the White House, but also the Senate and the House of Representatives. Once he nominates his Supreme Court candidate to replace Antonin Scalia, he will also be in control of that institution.

Bernie Sanders was the only candidate whose policies recalled the idea of the Democratic party of the Sixties. And according to a poll of 1,600 people run by Gravis Marketing, he would have soundly defeated Trump by 12 points. The Democrats have to get the message, or they run the risk of becoming a permanent minority party. They sorely need to look at themselves, and ask, What happened? As a starting point, they can take some of the advice contained in this essay.

Notes

1. “Hillary Clinton Snaps At NPR Host After Defensive Gay Marriage Interview.” YouTube. WFPL News, 12 June 2014 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vgIe2GKudYY>.

2. David Talbot, The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government. New York, NY: Harper, 2015.

3. Gary Leupp, “Hillary Clinton’s Foreign Policy Resumé: What the Record Shows.” , 03 May 2016.

4. Greg Grandin, “A Voter’s Guide to Hillary Clinton’s Policies in Latin America.” The Nation, 18 April 2016.

5. Tim Shorrock, “How Hillary Clinton Militarized US Policy in Honduras.” The Nation, 06 April 2016.

6. Peter Dale Scott, “The Deep State and the Bias of Official History.” Who What Why, 20 January 2015.

7. Ben Norton, “Sanders Condemns Pro-austerity ‘Colonial Takeover’ of Puerto Rico; Clinton Supports It.” Salon, 27 May 2016.

8. “Chomsky on Liberal Disillusionment with Obama.” YouTube, 03 April 2010 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A6Jbnq5V_1s>.

9. Peter Dale Scott, The American Deep State: Wall Street, Big Oil, and The Attack On U.S. Democracy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015: Chapter 2, p. 12.

10. “Project Censored 3.1 – JFK 50 – Peter Dale Scott – Deep Politics.” YouTube, Project Sensored, 19 December 2013 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L0CFpMej3mA>.

11. Angelo Young, “And The Winner For The Most Iraq War Contracts Is . . . KBR, With $39.5 Billion In A Decade.” International Business Times, 19 March 2013.

12. Zawn Villines, “The Four Worst Things Mike Pence Has Said About Women.” Daily Kos, 21 July 2016.

13. Richard D. Mahoney, JFK: Ordeal in Africa. New York: Oxford UP, 1983.

14. Donald Gibson, Battling Wall Street: The Kennedy Presidency. New York: Sheridan Square, 1994.

15. Carl Bernstein, “The CIA and the Media.” Rolling Stone, 20 October 1977 <http://www.carlbernstein.com/magazine_cia_and_media.php>.

16. David Talbot, Brothers, p. 47.