Part 1: 1945-1963

OHH:

We’ve got James DiEugenio here. He’s the publisher and editor of kennedysandking.com. It’s a great website with tons of information on a lot of Cold War history, the assassinations of the ’60s and a lot of interesting book reviews and things like that. He’s here today and we’re going to talk about the United States’ involvement in Vietnam and a lot about Kennedy’s involvement in that war as well. Thank you, Jim, for speaking today.

James DiEugenio:

Sure and I guess I should add that one of the reasons that I’m doing this, and one of the reasons that I wrote the four-part essay is because I was so disappointed in the Ken Burns-Lynn Novick colossal 18-hour, 10-part documentary series that was on PBS. I felt like it was a squandered opportunity. Our site became one of the big critical focuses of that disappointing series. I’m going to take that further with you in this interview.

OHH:

Great. Let’s just start from the beginning. What’s the history of the United States’ involvement in Vietnam?

James DiEugenio:

To understand how the United States got bogged down in this horrible disaster that ended up in an epic tragedy for both the people of Vietnam and a large part of the American population? It goes back to what historians – and I always like to take a historical viewpoint of things because I think that’s the most accurate way to understand something like this – call the second age of imperialism. Historians say the first age of imperialism, or colonialism took place in the late 1400s, early 1500s, when some of the great powers of Europe, the Dutch, the French, the British, the Portuguese and the Spanish started to carve up the Western Hemisphere.

Now, what we call the second age of imperialism took place from about the 1800s, in the early 1800s to the later part of the 1800s when the French and the British, to a lesser part the Germans and the Belgians, began to occupy areas of Africa and Asia.

Now, the French involvement in Vietnam began as a kind of religious missionary movement to convert the people of Indochina to Catholicism. And as that picked up steam, it became a kind of commercial relationship. The French built a factory there and they began to have trade agreements. By about the late 1850s, the French had a military attaché there and they began to attack the province of Da Nang and they created a colonial region in the southern part of Vietnam called Cochinchina. That spread gradually over the next few years into the central region and then finally the northern region which they called Aman. And then they began to spread it out even further westward into Cambodia and Laos.

This is how the French empire, which we called Indochina, that’s how it started and it lasted there of course until the fall of the French government to the Germans in the early part of World War II.

When Paris fell, the Japanese went in, filled the vacuum, and then at the end of World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt had made it clear before he died that he did not want the French to go back into Indochina after the war. He even asked the Chinese nationalist government if they would rather go in instead to prevent the French from going back in, they said, “No.”

He made it clear that he didn’t want any more colonial powers going back in and taking up the places they had before the war. Unfortunately, Roosevelt passed away shortly after that and as the Japanese left, the British came in and they allowed the French to come in behind them and reestablish their government in Vietnam. Except now there was an organized rebellion against this led by this guy named Ho Chi Minh. Ho Chi Minh tried to negotiate with the French. When that didn’t work, he decided to organize opposition forces to the French as they began to try and reoccupy Cochinchina.

Now, there was a fellow – and by the way, this was extraordinary to me that the Burns-Novick series left the figure of Bao Dai completely out of the picture. I don’t even think they mentioned him once. But Bao Dai had been the French figurehead in Vietnam. What really escalated the conflict between Ho Chi Minh and the French was the fact that the French now wanted to bring back Bao Dai.

Ho Chi Minh got really furious at this because he figured, look, if that’s what they’re designing to do, then what they’re going to do is to create another colonial empire because he knew that Bao Dai was nothing but a figurehead. He was not going to give democracy or self-government to the Vietnamese people at all.

That began what’s usually referred to as the first Indochina war.

What happened here of course is that once the Chinese and the Russians decided to stand by Ho Chi Minh when he declared his opposition to Bao Dai, Dean Acheson, Truman’s secretary of state, saw that as a movement towards communism. And this really shows you how crazy the times were and this was a huge problem back then in those days, that this whole idea that the Dulles Brothers put out and advocated for and Acheson preceded the Dulles Brothers but he had a lot of their trademarks in diplomacy.

The idea was this: you had to be on our side, and if you weren’t on our side, you were against us. This simply meant that there was going to be no neutrality. We’re not going to go ahead and allow third world nations to pick their own path. And as we’ll see, this will be a serious point of contention when Kennedy comes to power because he disagreed with that policy. When the French now picked up these hints that the United States would support them, they begin to escalate the war and Acheson and Truman now began to finance a large part of the French military effort to retake Vietnam and Indochina.

This went on for a couple of years. But in the election of 1952, when Eisenhower takes over and the Dulles brothers come to power – Foster Dulles of the State Department and Allen Dulles as director of the CIA – the aid to the French gets astronomical. It goes up by a factor of about 10, until by the last year of the war in 1954, the United States is literally dumping hundreds of millions of dollars and military aid, supplies, et cetera, into the French effort to maintain control of Indochina.

Now, John Foster Dulles brought Acheson’s ideas in the Third World to a point that I don’t even think Acheson would agree with. John Foster Dulles was extremely ideological about this whole issue. He simply would not tolerate any kind of neutrality by any new leader in the Third World. And this is why he and his brother then began to back the French attempt to a really incredible degree. By the last year of the war late 1953, early 1954, the United States was more or less financing about 80% of the French war effort. On top of that, because they were footing the bill, they would not even allow the French to negotiate a way out, because the French actually wanted to do that in 1952 or 1953. The French were going to negotiate a way out of this dilemma but Dulles would not tolerate it.

And so the war went on until the French made a last desperate strategic gamble to win the war in 1954 and that of course was the Battle of Dien Bien Phu.

OHH:

Can I interrupt you before we go onto Dien Bien Phu?

James DiEugenio:

Go ahead.

OHH:

Why were the Dulles brothers, was this purely an ideological thing they were pushing or did the United States, did we already have business there? Was it an economic thing too? What was the push for getting so deeply involved with the French?

James DiEugenio:

That’s correct. It was not just ideological because the Dulles Brothers, prior to becoming parts of the government, had pretty high positions in one of the giant, probably the predominant corporate law firm in the United States called Sullivan & Cromwell. In fact, John Foster Dulles was actually the managing partner there and he brought his younger brother Allen in as a senior partner. It’s not completely correct to say that this was all ideological because it wasn’t.

A large part of this was for commercial reasons in the sense that a lot of the clients that the Sullivan & Cromwell law firm represented had these large business interests in all different parts of the globe and sometimes this included Third World countries.

That’s another reason of course the Dulles Brothers were so intent upon putting down this rebellion against the French attempt to recolonize the area. Because to them, it was an example of an industrial or already commercialized western power going ahead and exploiting cheap labor and cheap materials in the Third World. In large part, that’s what that law firm represented. So that’s absolutely correct. It was not just ideological. It was also a commercial view of the world and what the Dulles Brothers stood for in relation to the use of the natural resources in the Third World.

Now, what happened at Dien Bien Phu, and I don’t think the Burns-Novick film really explained this as well as it should have, is that the French under Henri Navarre decided that they were losing the guerrilla war. So they decided to try and pull out the North Vietnamese forces, led by General Giap, into a more open air kind of a battle ground. They took over this low-lying valley in the northern part of Vietnam, not very far from the western border. The strategic idea was to get involved in a large scale battle where they would be able to use their air power and overpowering artillery to smash Giap’s forces.

Well, it didn’t work out that way for a number of reasons. But one of them was that the Russians went ahead and transported these huge siege cannons to Giap, and Giap used literally tens of thousands of civilian supporters to transport these huge siege guns up this incline overlooking Dien Bien Phu. They began to bombard the airfield there, which negated a lot of the military advantage that the French thought they were going to be able to use. When that started happening, John Foster Dulles began to arrange direct American aid. And I’m talking about military aid.

He actually began to go ahead and give them fighter planes, which he had repainted and drawn with French insignia run by CIA pilots. I think there were about 24 of them that he let them use. Then when that didn’t work, then he went ahead and started giving them large imports of other weapons to try and see if they could hold off the siege that was going to come. Finally, when that didn’t work, he arranged for Operation Vulture. Operation Vulture was the arrangement of a giant air armada. It was originally planned as something like, if I recall correctly: 60 small bombers, 150 jet fighters in case the Chinese intervened and also, three, I think there were B-36 Convair planes to carry three atomic bombs.

Dulles could not get this through Eisenhower. Eisenhower refused to agree to it because the British had turned him down. He didn’t want to do this by himself. Even though Dulles tried to convince the British to help, they turned them down twice.

Then Dulles, in a very strange move, he actually offered the atomic bombs to the French Foreign Secretary Bidault, Georges Bidault, in a separate private exchange which is a really remarkable thing to do because I’ve never been able to find any evidence that Eisenhower knew about that.

That’s how desperate he was not to see Dien Bien Phu fall. But the French refused, the guy said straight to Foster Dulles, “If I use those, I’m going to kill as many of my troops as I will General Giap’s.” Dien Bien Phu fell, and at this point, two things happened that will more or less ensure American involvement in Vietnam.

At the subsequent peace conference in Geneva, Switzerland, it’s very clear that the United States is calling the shots. Secondly, when the Chinese and Russians see that, they advised Ho Chi Minh to go along with whatever the western powers leaned towards. If not, they feared that the Americans would intervene immediately. In fact, Richard Nixon in a private talk with American newspaper editors, actually floated the idea of using American ground troops to intervene at Dien Bien Phu.

What happens now is that, John Forster Dulles goes ahead and orally agrees that there will be general elections held in two years in 1956, and whoever wins, will then unify Vietnam. He didn’t sign it because the lawyer that he was understood that that would expose him later, but he did advise his representative at the conference to go ahead and say they will abide by that decision.

This begins, for all intents and purposes, the American intervention in Vietnam and it begins – and this is really incredible to me that the Burns-Novick series never mentioned – Ed Lansdale, and how you can make a series, an 18-hour series about Vietnam and American involvement there and not mention Lansdale is mind-boggling.

They did show his picture but they didn’t say his name. The reason it’s so mind-boggling is that Allan Dulles now made Lansdale more or less the action officer for the whole Vietnam enterprise. In other words, the objective was, number one to create an American state in South Vietnam, and number two, to prop up an American chosen leader to be the American president of this new state.

Lansdale did it and I’ll tell you, it’s an incredible achievement what he did. Because he set up this giant psychological propaganda campaign, that scared the heck out of all the Catholics because the French had occupied the country.

OHH:

The whole country, we’re talking. This is the French were fighting over North Vietnam, South Vietnam. This was not splitting the two countries until this point, right?

James DiEugenio:

Right. They had converted a lot of the people there to the Catholic religion. What happens is that now, Lansdale has this great psychological propaganda war saying that Ho Chi Minh is now going to slaughter all the Catholic residents in North Vietnam. And so literally, hundreds of thousands of these converted Vietnamese now begin to come to the South and the CIA helps them by both land and by sea. They begin to transport them to the South because of the agreement was that all the Vietnamese would have I think a 36-month window to move in either direction.

This was a great, great propaganda victory for the Dulles Brothers because they said, “Look, all these people are fleeing the North. Why? Because we represent democracy and the North represents communist slavery”. That wasn’t the reason at all of course, but that’s how they used it. Then, they found this Ngo Dinh Diem guy…

OHH:

Well, before we go ahead, can we talk a little bit about Lansdale? Whose auspices… was he running under the CIA, was he part of the military?

James DiEugenio:

The reason I don’t think Burns and Novick wanted to introduce Lansdale is because there isn’t any way in the world that you can talk about what Lansdale did in South Vietnam and not bring in the CIA. Because although Lansdale had a cover as a brigadier general in the Air Force, he really wasn’t an air force officer. He himself admitted this.

We found some letters, John Newman and myself, up at Hoover Institute near Stanford in which he essentially admitted that he was really working for the CIA the whole time. He had done a lot of covert operations, most famously in the Philippines before he was chosen by Allen Dulles to lead this giant – which I’m pretty sure at that time – was the biggest CIA operation in their history. What he was doing here with this pure psychological warfare to get all these people to come south.

And if you expose who Lansdale is, there isn’t any way that you can say that this was not a CIA-run operation. This whole idea is to thwart the whole Geneva agreement, and number two to thwart the will of the people of Vietnam. Because the reason this was done of course, and Eisenhower admitted this later, was that there was no way in the world that the CIA could find any kind of a candidate that was going to beat Ho Chi Minh in a national election.

The CIA did these polls and they found out that Ho Chi Minh would win with probably 75 to 80% of the vote if there was an honest, real election. That’s why the CIA under Lansdale decided first to get all these new people into the south and then prop up this new government in the south to separate it from what they then called Ho Chi Minh’s area in the north.

Now, understand: that didn’t exist before. France had colonized the whole country. So now you had the beginning of this entirely new country created by the CIA. There’s no other way around that statement and I really think that the Burns-Novick film to be mild, really underplayed that. There would have been no South Vietnam if it had not been for Lansdale.

He’s the guy who created the whole country. Now, they picked a leader, a guy named Ngo Dinh Diem who was going to be their opposition to Ho Chi Minh. Well, the problem with picking Ngo Dinh Diem was number one, he spoke perfect fluent English; number two, he dressed like a westerner that is, he wore sport coats and suits and white shirts and ties and number three, he even had his hair cut like an American. His family was the same thing: his brother Nhu and Nhu’s wife Madame Nhu.

How on earth anybody could think that somehow Diem and his family was going to win the allegiance of all the people in Vietnam and win elections… well, that wasn’t going to happen. What Lansdale did is and … You got to admire the way these guys think even if you don’t like the goals they achieve, the way they do it is very clever. Lansdale, number one, wanted to get rid of Bao Dai because he did not want to have anymore – him and John Foster Dulles had agreed – they had to get rid of the stigma of French colonialism.

They sponsored a phony plebiscite, an up or down plebiscite on bringing Bao Dai back in 1955. Now, anybody who analyzes that election in 1955 will be able to tell you very clearly that it was rigged. To give you one example, Bao Dai was not allowed to campaign. It was pretty easy to beat somebody if the other guy cannot campaign, and Lansdale, for all practical purposes, there’s no other way to say this, he was Diem’s campaign manager. It was CIA money going in and running his campaign and there’s a famous conversation where Lansdale, because he has all this money and because they’ve already built up a police force in South Vietnam, he essentially tells Diem that, “I don’t think that we should make this very blatant. I don’t think you should win with over 65% of the vote.”

Well, Lansdale decided he should be out of the country during the actual election so it wouldn’t look too obvious. So Diem then went ahead and decided he wanted to win with over 90% of the vote and that’s what it was rigged for. And as everybody who analyzed that election knows it was so bad that you actually had more people voting for Diem in certain provinces than actually lived there. That’s how bad the ballots were rigged. But it did what they wanted to do. It got rid of Bao Dai, so now in a famous quote by John Foster Dulles, he said words to the effect that: Good, we have a clean face there now. Without any kind of hint of colonialism.

Now, you can believe he said that, it’s actually true. And it shows you the disconnect between the Dulles Brothers and Eisenhower with the reality that’s on the ground there because Diem is going to be nothing but a losing cause. Now that Diem is in power, Lansdale then goes ahead and advises him to negate the 1956 election and that’s what happens. The agreements that were made in Geneva were now cancelled, and this is the beginning of two separate countries. You get the north part of Vietnam led by Ho Chi Minh and with its capital at Hanoi and you get South Vietnam which is a complete American creation with its capital at Saigon led by Diem.

By the end of 1957, and this is another problem I had with the Burns-Novick series – they try and say and imply that the war began under Kennedy. Simply not true.

And by the way, this is something that Richard Nixon liked to say. He liked to say that, “Well, when I became President I was given this problem by my two predecessors.” No no, not at all.

In the latter part of 1957, I think in either November or December, the leadership in the North, that is Ho Chi Minh and Le Duan and General Giap, they had decided they were now going to have to go to war with the United States. They began to make war plans at that early date and those war plans were then approved by the Russian Politburo. And both Russia and China, because in some ways it had been their fault that this happened by advising Ho Chi Minh to be meek and mild at the Geneva conference; they agreed to go ahead and supply Ho Chi Minh with weaponry, supplies and money.

The war now begins. In the first Indochina War, France against the Vietnamese, the rebels in the south were called the Viet Minh. While now the Viet Minh are converted into the Viet Cong. This rebel force in the south now begins to materialize again except their enemy is Diem. Now begins the construction of the Ho Chi Minh Trail which crosses down through Laos and Cambodia and this is going to be a supply route to supply these rebels in the south and actually infiltrate troops into the south.

The other way they’re going to do it is through a place called Sihanoukville in Southern Cambodia, there they’re going to bring in supplies by sea. Now, for all intents and purposes, the war now begins in around 1958.

There begins to be hit and run raids against the Diem regime in the south. The United States now begins to really build up, not just a police force, which they had done before, but they now begin to build up a military attaché in the south. By the end of the Eisenhower regime, there’s something like about, if I recall, about 650 military advisers there with the police force that is trained at Michigan State University under a secret program.

The battle in the countryside now begins in earnest: 1958, 1959, 1960. Diem, as he begins to be attacked, now gets more and more tyrannical. He begins to imprison tens of thousands of suspects in his famous tiger cages. These bamboo like 2′ by 4′ cages which people are rolled up like cinnamon rolls and kept prisoner, there were literally tens of thousand of those kinds of prisoners by 1960. He actually began to guillotine suspects in the countryside.

As more and more of this militarized situation takes place, it begins to show that the idea that the United States is supporting a democracy is a farcical idea: because it’s not a democracy in the South because the police force is run by his brother Nhu and Diem is very much pro-Catholic and anti-Buddhist and unfortunately, for the United States, about 70% of the population in South Vietnam was Buddhist, even with the hundreds of thousands of people who fled south.

The situation, and by the way, Lansdale was still there. He’s still supervising Diem, trying to hold on to this thing because he had so much invested there. As time goes on and the situation becomes more militarized, there actually comes to be a coup attempt against Diem in 1960, and the American ambassador in Saigon, I think his name was Elbridge Durbrow, he even lectures Diem that you’ve got to democratize this country, or else you’re going to be the symbol of this whole militaristic situation and you’re going to be under a state of siege, and this won’t work. That’s the situation that occurs during the election of 1960 with Kennedy versus Nixon. That’s the situation that whoever wins that election is going to be presented with.

OHH:

There’s an actual line here from Lansdale I guess, they acknowledge that this is a fascist state they set up.

James DiEugenio:

Lansdale actually said that. It’s a famous quote he said when things began to spin out of control when things began to be an overt militarized struggle by ’64, ’65 – where he said words of the effect: I don’t understand these people who complain about democratic rights and human rights, when I was never instructed to build that kind of state. I was instructed to build a fascist state and that’s what I did. Talk about from the horse’s mouth. That’s not an exact quote but it’s pretty much what he said.

What happened is that the CIA sent in completely trained police officers that were meant to monitor and surveil any kind of, what they perceived as being subversive opposition to Diem. The CIA plan was that: we probably can’t control the countryside because it’s too big and it’s too expensive. But we have to maintain control in the big cities. So they began to issue ID cards, which identified the great majority of the population so they could begin to keep track of it and then they began to train the police forces to go ahead and root out anybody they thought was subversive.

You’re never going to get an exact number of how many people Diem put in prison. But one of the most credible numbers I’ve seen is about 30,000. That’s how big the prison population was. Anybody who dissented against the Diem regime. What made it worse, what made it really almost fatal, was the fact that his brother Nhu did not want to tolerate religious freedom for the Buddhists. You had this crushing of political dissent and then you had this perceived persecution on religious grounds.

It began to be a kind of endless downward spiral where the Diem regime needed more and more American aid to stay in power because it could not win, in the famous Lyndon Johnson phrase, “the hearts and minds of the people”. More and more aid began to be funneled into South Vietnam.

It was like an inverse equation, the more the political system failed, the more the military system had to be escalated if we’re going to hang on to South Vietnam. That is the terrible situation that Kennedy is confronted with when he becomes president, when he’s inaugurated in January of 1961.

OHH:

Let’s talk about what Kennedy’s initial moves were? I mean, he had a lot facing him. Obviously, Cuba was probably more in the news as was things happening in Berlin, but how did Kennedy try to deal with Vietnam at the beginning of his administration?

James DiEugenio:

Well, that’s exactly right because Vietnam did not figure very strongly in the 1960 campaign. It was about the islands off the coast of China, Quemoy and Matsu, and about Cuba. Kennedy tried to get some things in there about Africa during the campaign but there really wasn’t a heck of a lot about Vietnam in the 1960 campaign. In fact, as we know now, the Eisenhower administration was actually secretly planning for the Bay of Pigs operation with Nixon and Howard Hunt.

When Kennedy becomes president, he’s immediately confronted with these conditions in South Vietnam. And Edward Lansdale, I think it was a few days after the inauguration, hands him a report about how dire the situation is in Saigon, and he predicts that if the United States does not assert itself – meaning sending in American ground troops – that the Diem regime is in danger of falling.

That was really the first time that Kennedy had ever heard such a thing. Because when he and Eisenhower had talked – they had a two-day conference to go ahead and facilitate the transition – Kennedy said that the country in Indochina that Eisenhower warned him about was not Vietnam, it was Laos. That’s why Kennedy first tried to solve the Laotian situation, in which he chose to put together a neutralist solution to the problem in 1961.

Confronted with Vietnam, after Lansdale’s report, this created a landslide. Person after person, Walt Rostow, Maxell Taylor… by November of 1961, there are about eight reports on his desk, all encouraging the United States to send ground troops into South Vietnam. Even McGeorge Bundy, his national security adviser, recommended 25,000 ground troops, American combat troops, to go ahead and enter into South Vietnam to save the country.

At this point, I think it’s necessary to correct another terrible mischaracterization in the Burns-Novick series. If you don’t understand who Kennedy was by 1961, then you cannot in any way present what Kennedy did in an honest way from 1961 to 1963. Kennedy was in Vietnam in 1951 as he was getting ready to run for senator. He took a trip into Asia. He landed at the Saigon airport and he deliberately avoided being briefed by the French emissaries or representatives of the French administration or the French press there. He had a list of people that he wanted to talk to. One of them was Edmund Gullion – who the film never mentions. They mentioned a New York Times reporter, I think his name was Seymour Topping.

It was the Gullion meeting that really impressed Kennedy because Gullion simply stated, when Kennedy asked him, “Does France have a chance of winning this war?” Gullion said, “No. France doesn’t have any chance of winning. There’s no way in the world we’ are going to win this thing.” JFK said, “Well, how come?” Gullion said, “Look, Ho Chi Minh has fired up the Vietnamese population, especially the younger generation, to a point that they would rather die than go back to French colonialism. With that kind of enthusiasm, that kind of zealotry, there’s no way in the world that the French are going to kill off a guerrilla movement because it’s going to devolve into a war of attrition. You will never get the French population in Paris to support that kind of a war.” That’s why Gullion predicted France and America would lose, way back in 1951.

That talk had a tremendous effect on Kennedy’s whole view of the Cold War. Up until that point, Kennedy was more or less a moderate in a Democratic Party on that issue. That meeting radicalized Kennedy on the whole issue of the Third World, because he now began to see it as being not really about democracy versus communism. It’s really about independence versus imperialism, and the United States had to stand for something more than anti-communism in the third world in a practical sense, or else, we were going to lose these colonial wars.

Kennedy now began to map out this whole new foreign policy that, I’m not exaggerating very much when I say that no other politician in Congress had at that time. I don’t know of any other politician, senator or congressman, that this early, 1951, 1952, began to pronounce these statements that Kennedy is going to go on with for six years. Namely that it’s not the Democrats that are wrong, it’s not the Republicans that are wrong: both parties are wrong on this. We have to understand that in the Third World, we have to be on the side of independence. Nationalism is a kind of emotion, a kind of psyche that’s not going to be defeated there. We have to understand that.

So when Dien Bien Phu fell in 1954, Kennedy was on the Senate floor saying that: it doesn’t matter how much men, how much material we put in, this is not going to work; direct American intervention is not going to work. Operation Vulture is not going to work. That continued until his great speech in 1957 on the floor of the Senate about the French colonial war in Algeria. And I advise anybody, if you want to see who JFK really was, read that speech. It’s in that book, The Strategy of Peace, the entire speech.

In that one, he essentially says: Look, we saw this happening three years ago in Indochina, and now it’s repeating itself on the north coast of Africa. How many times do we have to go through this to understand what the heck is happening here? If we were the real friends of France, we would not be sending them weapons to fight this colonial war with. What we’d be doing instead is we’d be convincing them to go to the negotiating table and exit, find a gentlemanly way to get out of this thing so that not only can they spare the bloodshed, but they can save a civil war in their own country over this.

That speech in the summer of 1957, that speech was so radical, it was so revolutionary that, if I remember correctly, there were 165 editorial comments about it throughout half the newspapers in the United States, half of the major newspapers in United Stated commented on it. Two thirds of them were negative. That’s how far ahead of the curve JFK was. We know two-thirds of them were negative because his office clipped all the newspapers; he had a clipping service.

Kennedy was really stunned by this, “Did I make a mistake here?” He wrote his father saying: You know dad I might have miscalculated on this thing. I’m getting hammered in the press. His father wrote back to him and said: You don’t know how lucky you are, because two years from now when this thing gets even worse and everything you predicted turns out to be true, you’re going to be the darling of the Democratic Party.

And that’s what happened. When Kennedy comes in to the White House – and this is where I have a disagreement with a lot of people in the critical community including people like John Newman, even Jim Douglass – my view of it is that in 1961 he already has the gestalt idea of what his foreign policy is going to be. And a big part of that is: I’m going to do everything I can not to intervene with American military power in the Third World, whether it be Cuba, whether it be Vietnam.

When the debates come in the fall of 1961, when everybody in the room is telling him: You’ve got to send ground troops into South Vietnam or the country is going to fall. McNamara, if you can believe it, Defense Secretary McNamara was even worse than McGeorge Bundy. He wanted 200,000 men to be sent in the South Vietnam. Kennedy, as he is described in many books – a good one is James Blight’s book Virtual JFK, he spends 40 pages discussing those debates – Kennedy is virtually the only guy in the room, who was resisting all of it. This was a difference between Kennedy and Johnson.

Kennedy was not a domineering kind of a personality. He would encourage his advisors to say what they thought, whereas Johnson would use every rhetorical trick in the book to steer everything to go his way. He’d use ridicule, sarcasm, et cetera.

Kennedy wasn’t like that, and so he let this debate go on. Finally, after about two weeks, he said: No, we’re not going to go ahead and commit ground troops in the Vietnam for a number of reasons. Number one, we are not going to be able to get anybody to ally ourselves with. We’re going to have to go to this alone. Secondly, it’s a very, very hard thing to understand. It’s not like the Korea situation where you have the North Korean invasion come across the border. This is much more of a civil war. The mass of congressmen, let alone the public, is not going to be able to understand it. Third, how do you send in infantry divisions and artillery divisions to fight a war in the jungles of Indochina? Of course, those all ended up being accurate. He did go ahead and increased the number of advisors; he sent in 15,000 advisors.

Right after this, and this is something that people like David Halberstam in his incredibly bad book, The Best and the Brightest, they shrug this off in a sentence. Right after this, JFK tells John Kenneth Galbraith, his ambassador to India: I want you to go ahead to Saigon and I want you to write me a report on what you think is going on there and if you think the United States should go in there with combat troops and the whole armada – knowing, of course, that Galbraith thinks it’s a stupid idea.

That was meant to counteract the report that Walt Rostow and Gen. Max Taylor had brought back to him in which he had gone over in the debate. He gets his Galbraith report, and sits on it for a while. When Galbraith comes to town in April 1962, he tells him: Take your report on Vietnam, bring it to McNamara, and tell him it’s from me.

That’s what Galbraith did, and he wrote back to Kennedy saying: All right, I did what you asked me to do, and McNamara’s on board. This is how, number one, Kennedy finally got an ally in his own cabinet to share his view of Vietnam, and McNamara now becomes the spearhead for what’s going to be Kennedy’s withdrawal plan. That’s the beginning of Kennedy’s plan to withdraw from South Vietnam.

OHH:

Now, just to go into some of it, Kennedy wasn’t doing nothing in Vietnam. Did he setup the things like the strategic hamlets? He carried on the war to some degree, right? But not with American troops.

James DiEugenio:

Correct. What I think Kennedy was trying to do, he was essentially running a kind of two-track program. He wanted to see if this more expansive advisory aid would do any good. Is the problem that we’re not giving Saigon enough aid to counter the Russian and Chinese aid being given to Hanoi? Is that the problem?

What he decided to do was, number one, to try and expand the aid to Saigon and, at the same time, if that doesn’t work he’s also planning a withdrawal from Saigon. Kennedy’s idea was this: We can go ahead and help the people we are allied with. We give them money, we can give them supplies, we can give them weapons, we can send in trainers but we can’t fight the war for them. We can’t do that.

He quite literally said that to Schlesinger. He said: If we fight the war for them, then we’re going to end up like the French; and I saw that. We can’t make it into a white man’s war. He quite literally said, “We can’t make it into a white man’s war” or it will be recognized as that by the native population.

On the one hand, he’s trying to give them extended help and on the other hand he’s planning withdrawal in case that doesn’t work.

There’s one other element here – there’s the 1964 election. See, as John Newman said in his groundbreaking book, JFK and Vietnam, the best way to explain the two men in relation to Vietnam was that Kennedy was planning his withdrawal plan around the 1964 election, Johnson was planning his escalation plan around the 1964 election.

Remember, John Newman wrote his book, I think it was published in 1992 which is 25 years ago, and everything that has come out of the archives since then has supported that he is absolutely right about that whole issue. Kennedy actually said such to Kenny O’Donnell and Dave Powers: I’m going to be damned as an appeaser when we leave by everybody on the right after the election, but we better win the election because that’s what I’m going to do.

It was those three things, it was the trying to help and train the people we’re allied with as much as we could. Number two, planning for withdrawing in case that doesn’t work, and then timing it around that 1964 election. I think those are three things we have to understand about the Kennedy administration, in his approach to the war.

OHH:

Can you walk us through the assassination of Diem? Why would Kennedy want to make such a drastic change at that point?

James DiEugenio:

I’m glad you asked me that question because there’s some new information on that which, of course, everybody has ignored. I haven’t seen any mention of this in any media outlet, whether it’d be the mainstream press or the so-called alternative press. [Editor’s Note: This interview was on 6/20/75 by the Church Committee and was declassified on July 24, 2017]

What I’m talking about is the top-secret Church Committee interview with Bill Colby, which was in 1975. Colby was, first of all, he was stationed in Vietnam up until I think the summer of 1962 and then he became the CIA’s Chief of the Far East, which made him the top officer in that area.

Let me go ahead and sketch in the background. There’s two things we should understand about what happened with the coup attempt against Diem and his brother, which culminated in early November of 1963.

First of all, as time goes on, Diem and especially his brother Nhu, began to be more and more tyrannical about any dissent in South Vietnam. As time goes on, and the success of the Viet Cong gets more and more strong, is that the dissent now begins to pour into the cities, and it comes in a way through the Buddhist demonstrations which began to be, by late 1962, early 1963, pretty massive. Nhu, who was in charge of the secret police in Saigon, now decides to crack down on these demonstrations. That’s one element.

The second element is that as the war begins to be more obviously a losing proposition by about late 1962, it becomes clear to a lot of people, I think including Kennedy and certain elements in the State Department, that is Averill Harriman, Mike Forrestal, and Roger Hilsman, that this new support that Kennedy is giving isn’t doing very much good. We’re not getting very much results compared to the amount of money and supplies and advisors we have there. What happens is, the press, and I’m talking about David Halberstam and Neil Sheehan, they got together with one of the advisors that’s stationed there, John Paul Vann, and they begin to write stories about how Kennedy is not doing enough, we’re not doing enough to win this war.

What happens, the key event, is the battle of Ap Bac. This began in early January, 1963. There a heavily supported force consisting of two South Vietnamese battalions, parts of a regiment, and three companies, supported by armed personnel carriers, artillery and at least ten helicopter gunships, lost to a force less than half that size, consisting of Viet Cong supplemented by North Vietnamese regulars.

Roger Hilsman was in country at that time and he read up on this thing. He begins, and the only term you can call this is a cabal within the State Department that begins to plot to get rid of Diem’s government. They’re convinced by now that Diem cannot win this war. They essentially said: We picked the wrong guy. So they hatched a plot that when everybody is out of Washington, there was a weekend, the third weekend of August, when Kennedy has decided to change ambassadors. He wanted to bring Gullion into Saigon. Secretary of State Dean Rusk rejected that, and Rusk picked Henry Cabot Lodge.

While that was going on, Hilsman and his circle run a con job on Kennedy on a weekend knowing that everybody’s out of town. They tell him that all of his advisors, including John McCone, the new CIA director, have agreed to send an ultimatum to Diem: You have to get rid of your brother, you have to grant more democratic rights or we’re going to side with the military against you. They read this to Kennedy who’s up in Hyannis Port, and Kennedy said, “McCone’s on board with this?”, and they say, “Yeah.” [See John Newman, JFK and Vietnam, Chapter 18]

Well, they didn’t show it to McCone. That’s why Kennedy had a hard time because he knew that McCone was a big Diem backer. They deceived him. That’s the first part. The second part was that Lodge did not go to Diem and counsel him first as to what the plan was. He went directly to the generals who wanted to overthrow Diem with the telex – this is called a cable.

When Kennedy comes back to Washington and he discovers what’s happened, he’s furious. He starts slamming the desk: “This shit has got to stop!” Forrestal, who had been part of the plot, offered his resignation and Kennedy says very coldly, “You’re not worth firing. You owe me something now.” Kennedy cancels the order. Cabot Lodge, on that 1983 PBS special, which is much better than the Burns-Novick one, he admits getting that cancellation order.

The new evidence we have now is that Bill Colby told the Senate in a private session, he said that the generals backed away from the overthrow attempt for a couple of months. He then added that it’s when the Commodity Import Program cancelled Diem’s credits, which was a month after that, that they decided to go ahead because to them that told them that Diem didn’t have any more support from the business community at all. (See aforementioned Colby deposition, po. 37, 74)

If you want to see how important that is, if you go to Jim Douglass’ book, he talks about that meeting in which the CIA representative at the meeting, they were having a meeting about Vietnam, and he suddenly … Kennedy is talking about the financial support we’re giving Diem and the CIA guy at the meeting says, words to the effect: “Sir that’s been cancelled.” And Kennedy says he didn’t cancel it. And the reply is: I know you didn’t cancel it. He says: It’s automatically cancelled at a certain dispute level. [Refer to Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable, p. 192]

Kennedy gets angry and he says, “My God, do you know what you’ve done?” The guy doesn’t say anything because Kennedy knew what’s going to happen. That’s the event that Colby says that recharged the plot to overthrow Diem. When Kennedy found out about this, he tried to send a private emissary to Diem to relieve his brother Nhu and take refuge in the American Embassy. He didn’t listen to him. Instead, Diem made a terrible mistake. He decided to work with Lodge when they started laying siege at the Presidential Palace.

I can’t recommend … there’s no better chronicle of this than what’s in Jim Douglas’ book, JFK and the Unspeakable. I think between that, the chapter in Newman’s book and what Colby said in his private session with the Church Committee, I think it’s pretty clear. I don’t think you can prove this beyond a reasonable doubt, but I think you can prove it beyond what they call a preponderance of the evidence. I think it’s pretty clear that Lodge and the de facto head of the CIA station, Lucien Conein (because Lodge had gotten rid of the actual CIA station chief because he figured he favored Diem too much). Lodge and Conein, because Diem was calling Lodge thinking that he was going to help him get out of Saigon, really Lodge was relaying those messages to Conein who was in communication with the generals.

So when Diem comes out of that church thinking he is going to have a limousine to the airport, it is really the generals who greeted him and they assassinated him in the back of the truck. [See Douglass, pgs. 192-210]

Kennedy was furious about this when he heard about it. He walked out of the meeting with Taylor pounding his teeth. He told Forrestal that he was going to recall Lodge for the purposes of firing him and then they were going to have a huge meeting, and then we’re going to go ahead and educate everybody about how the hell we got into this mess because he was going to try and educate them to his point of view.

What happened, of course, is that Kennedy is assassinated in Dallas. Johnson becomes president and doesn’t fire Lodge. He keeps Lodge there. Instead of educating them to Kennedy’s point of view, at the very first meeting, it’s very clear that Johnson is going to, instead of getting out of the war, he is determined not to lose the war. Then of course, everything changes in a period of just a matter of months.

As many authors have noted, Johnson’s point of view about this whole thing was diametrically opposed to Kennedy and it went all the way back to 1961 where he was sent to Saigon on a goodwill tour and he actually told Diem to ask Kennedy for military troops at that time in 1961. Everything changes very quickly once Kennedy is assassinated and once Johnson takes over.

OHH:

Can you just give us some of the numbers? How many soldiers died in Vietnam by the time Kennedy was assassinated? How many advisors were there? The war didn’t really get started until pretty far into Johnson’s administration. Is that right?

James DiEugenio:

The war doesn’t begin in a real sense until Johnson wins the election in 1964. Once he does that, then about three months later there begins to be a big Air Force buildup, a bombing buildup; and then ground troops begin to arrive in 1965 at Da Nang to compliment the big air buildup that’s going to take place.

When Kennedy is killed, there’s something like 15,000 American advisors. No combat troops in Vietnam. I think, at that time, there had been, all the way through from Eisenhower to Kennedy, I think there are about 135 American fatalities in Vietnam. It’s minuscule; when it’s all over, of course you’re going to have 58,000 dead American troops, about 300,000 casualties, and on top of that you’re going to have the greatest air bombing campaign in the history of mankind. Rolling Thunder under Johnson, and then a continuance of that especially over Laos and Cambodia by Nixon. There’s going to be more bombs dropped over Indochina than the allies dropped during all of World War II.

OHH:

What do you think next? You could go into the NSAM itself, if you are interested in that, or we could go on to the Johnson’s part of the war?

James DiEugenio:

One of the things … the big problems I had with the Burns-Novick program was that the stretch of time between Kennedy’s assassination, which was of course in November of ’63 until the Gulf of Tonkin incident, was very much underplayed.

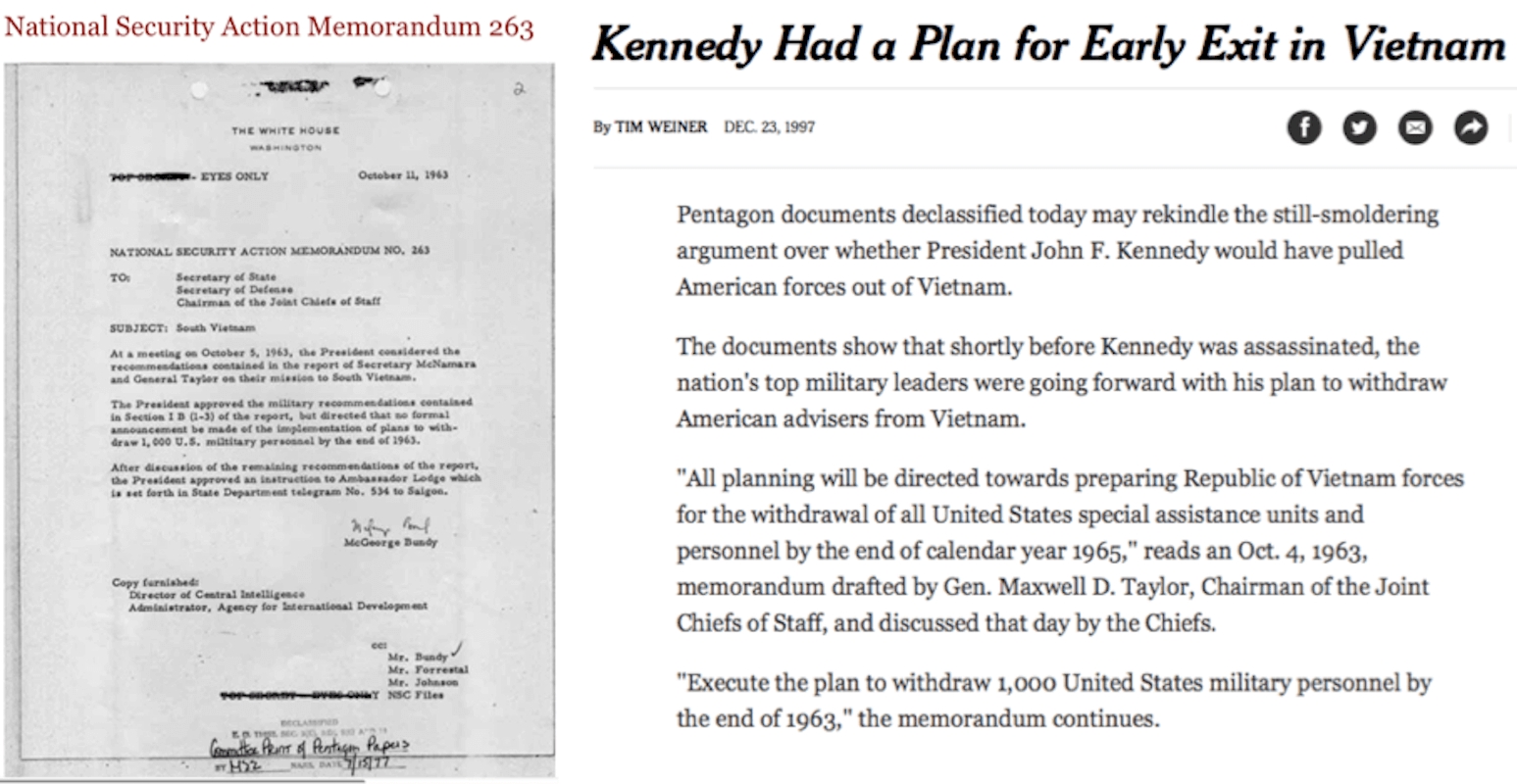

First of all, there was no mention of NSAM 263 which is unbelievable. Really kind of shocking because NSAM 263, of course, was Kennedy’s order that officially began his withdrawal program. That withdrawal program actually began in May of 1963. The implementation part began in May of 1963 when McNamara met was all of the CIA, State Department, Pentagon advisors from Vietnam at a meeting in Honolulu called the SecDef conference. At that meeting, he demanded that everybody bring with them their schedules for getting out of Vietnam.

When he was presented with those schedules he said, “This is too slow. We have to speed this up,” which is a very curious comment which no one has really been saying anything about. I think the reason that McNamara said that … One of the most important declassified documents that came out since the closure of the AARB, and Malcolm Blunt, a wonderful British researcher found this and he sent it to me, is that Kennedy ordered an evacuation plan for South Vietnam which had just been returned to him the first week of November.

John Newman, in my talks with him, has said that McNamara and Kennedy were worried that Saigon would fall before the withdrawal was completed. In other words, Kennedy had mapped out his withdrawal program from late 1963 to the middle of 1965. It would be completed by that time, approximately 1,000 troops a month but they worried that Saigon would not be able to hold out. I think that’s why Kennedy ordered that evacuation plan. Once that’s in place, once McNamara has made it clear to the people in Saigon that the United States is getting out, then Kennedy goes ahead and gathers his advisors in October of 1963 and he pre-writes the McNamara-Taylor report. That report was not written by McNamara-Taylor. It was written by Victor Krulak and Fletcher Prouty under the direction of Bobby Kennedy under the orders of Jack Kennedy. The Novick-Burns series didn’t mention any of this about NSAM 263 or about the writing by the Kennedy brothers of the Taylor-McNamara report.

Vietnam War and the USA

Generally, historians have determined a number of causes of the Vietnam War including European imperialism in Vietnam, American containment, and the expansion of communism during the Cold War.

The aftermath of the Vietnam War

Thousands of members of the US armed forces were either killed or went missing. While Vietnam emerged as a potent military power, its industry, business, and agriculture were disrupted, and its cities were severely damaged. In the US, the military was demoralized, and the country was divided.

Part 2

This interview was edited for grammar, flow and factual accuracy.