KUsomething:

“Jesus, you don’t look so good!”

WOsomething:

“Look who’s talking, I’ve never seen you so baggy-eyed.”

KUsomething:

“I don’t handle the heat very well. I wonder how the Old Man is doing. Apparently, it’s a lot hotter a few floors down.”

WOsomething:

“Tell me, have you seen AMHINT-24 around?”

KUsomething:

“You mean the one who bumped into GPFLOOR in the courthouse after his rumble on…”

WOsomething:

“No that was AMSERF-1.”

KUsomething:

“Then was it the guy who got all those articles written about him with the help of AMHINT-5? … I thought he was AMDENIM-1.”

WOsomething:

“AMHINT-24 was in on the brouhaha on … uh, Canoe Street; he also helped Don Santo Junior recruit AMLASH with the help of their friend AMWHIP-1. It gets a little confusing because many were part of AMSPELL… Then when you throw in the 30 or so AMOTs living here… Maybe AMSHALE-1 will help clear things up when he joins us.”

KUsomething:

“I don’t think we will be seeing him here, he seems to have gotten most of his shit together… I doubt he would even speak to me anyway, after getting shot at and all…”

WOsomething:

“Well, I can think of only a few others who might be soon joining us. Hopefully, they won’t blame us like the others do.”

KUsomething:

“Man it’s hot!”

Introduction

In 2013, just before the fiftieth anniversary of JFK’s assassination, this author completed a study on how North American history books describe the JFK assassination and how their authors justify their writings. The most distributed books overwhelmingly portrayed the crime as one perpetrated by a lone nut, and their key sources are the Warren Commission along with a few authors who re-enforce this notion.

After corresponding with the historians, it became clear that almost all were unfamiliar, if not completely unaware, of critical information that came out in the half-century that followed. Many of the post-Warren Commission sources cannot simply be fluffed off as conspiracy theorist machinations. These include five subsequent government investigations; one civil trial; a number of mock trials; three foreign governments’ analysis of the assassination; and some groundbreaking work by a number of dedicated, independent researchers.

In a subsequent article, it was demonstrated that most government investigations that followed (and therefore should have trumped) the Warren Commission, as well as the only civil trial about the case, proved that a conspiracy took place and that the Warren Commission hardly even investigated this possibility.

When one considers the written conclusions from many of the reports, jury decisions and comments from investigation insiders, which contradict the Warren Commission report, it is clear that many of these historians were in breach of their own code of conduct by woefully disrespecting the official record. Furthermore, they showed no effort in following the proper historical research methodology that can be summarized as follows:

- Identification of the research problem (including formulation of the hypothesis/questions);

- Systematic collection and evaluation of data;

- Synthesis of information;

- Interpreting and drawing conclusions.

By stopping all research beyond the obsolete Warren Commission report and limiting themselves to a few discredited authors, historians never made it to step two in their work. In fact, the impeaching of the Warren Commission by both the Church Committee and the HSCA should have stimulated investigators, journalists and historians to start anew with one of the hypotheses being that there was a probable conspiracy.

Over and above underscoring historians’ ignorance of the work of their own institutions, this author sought to contribute to the data collection step in the research by analyzing previous plots to assassinate JFK and bringing out patterns that should have been impossible to ignore and that clearly pointed the finger at persons of interest in the case. In a fourth article, Oswald’s touch-points with some sixty-four plausible or definite intelligence-connected characters (since updated to seventy-five) underscored the Warren Commission’s hopelessly inaccurate and simplistic description of him as a lone malcontent.

Another source of valuable information that historians are oblivious to comes from what foreign governments knew about the conspiracy. Cuba in particular was very motivated to monitor many of the persons of interest in the Kennedy assassination; for them their survival was at stake!

Gaeton Fonzi, as an investigator for both the Church Committee and the HSCA, was perhaps the first to sink his teeth into the confusing world of Cuban exiles who were involved in plots to remove Castro. This allowed him to better connect the dots with CIA and Mafia forces that were influencing them. In doing so, researchers who were effective in disproving Warren Commission conclusions would now be better prepared to identify the plotters. Malcolm Blunt, John Newman, Bill Simpich and others began deciphering CIA cryptonym codes related to a hornet’s nest of secrets and covert operations that Allen Dulles kept hidden from his Warren Commission colleagues. In doing so, he deprived them of crucial information that could well have brought the spotlights right back on him.

On the Mary Ferrell Foundation website, we can now find a database of CIA cryptonyms and pseudonyms carefully designed to designate people, organizations, operations and countries. For example, cryptonyms that begin with the letters AE relate to Soviet Union sources, in particular defectors and agents, and those that start with LI refer to operations, organizations, and individuals related to Mexico City. The category, which has by far the most cryptonyms, is the one that starts with the letters AM, which were used for protecting the identity of operations, organizations, and individuals relating to Cuba. As we will see, an impressive number of crypto-coded jargon revolves around the world of Oswald and the Big Event.

In this article, we will: first, assess what some foreign intelligence services concluded about the assassination; second, explore how seemingly different factions came together to form one of America’s most ruthless team of covert operators, assassins, saboteurs and terrorists that wreaked havoc abroad and on American soil for decades; third, describe the make-up and some of the covert actions of what the Cubans called The CIA and Mafia’s “Cuban American Mechanism”; and finally, see how this obscure, misunderstood entity came to play a role on November 22, 1963.

France, Russia and Cuba nix the Warren Commission report

It is important to preface this section by recognizing that the quality of foreign government data is sometimes difficult to evaluate. Some would argue, perhaps rightly, that it does not always come with primary source information, that the data is old and that there could be hidden biases. On the other hand, we will see that foreign intelligence also had different sources that would logically have been well connected and positioned to observe the goings-on in and around the persons of interest, including Oswald himself; that they may in fact have had fewer biases than those controlling U.S. investigations; and that their research is much more recent than the sources lone-nut backers rely upon. As a matter of fact, Cuban analysis takes into account key ARRB declassified documentary trails that Warren Commission backers’ hero Gerald Posner could not do when he wrote Case Closed just before the ARRB vaults of classified documents were opening. In an open-ended investigation, not looking into what these sources can reveal is simply derelict.

It was not only foreigners who suspected foul play the minute Ruby terminated Oswald; dark thoughts were omnipresent in the U.S. The very first media reactions clearly indicated that Oswald was bumped off in order to seal his lips.

In an article written for the Washington Post, and published one month after the assassination, former president Harry Truman, who had established the CIA in 1947, opined that the CIA was basically out of control:

For some time I have been disturbed by the way the CIA has been diverted from its original assignment… This quiet intelligence arm of the President has been so removed from its intended role that it is being interpreted as a symbol of sinister and mysterious foreign intrigue– and subject for cold war enemy propaganda.

He said the CIA’s “operational duties … should be terminated.” Allen Dulles, then sitting on the Warren Commission, tried unsuccessfully to get Truman to retract the story. Some have speculated that the timing of the writing of this article was linked to the assassination.

Shortly after the media congratulations greeted the Warren Commission Report release, valiant independent researchers such as Vincent Salandria, Penn Jones, Sylvia Meagher and Mark Lane played key roles in debunking it. Some foreign governments were also forming their own opinions about what really took place.

Neither Jackie Kennedy nor Bobby Kennedy believed the Warren Commission, nor did they trust U.S. intelligence to find the underlying cause of what really happened. According to the late William Turner and Jim Garrison investigator Steve Jaffe, they received information from French intelligence, which had monitored Cuban exiles and right-wing targets in the U.S. (perhaps because they felt some of the attempts on De Gaulle’s life stemmed from the U.S.). They reported that the president had been killed by a large rightwing domestic conspiracy.

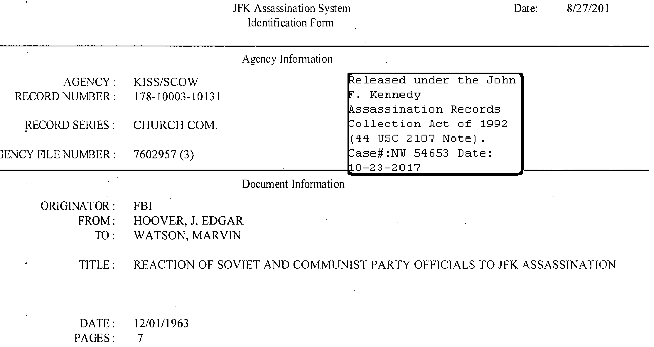

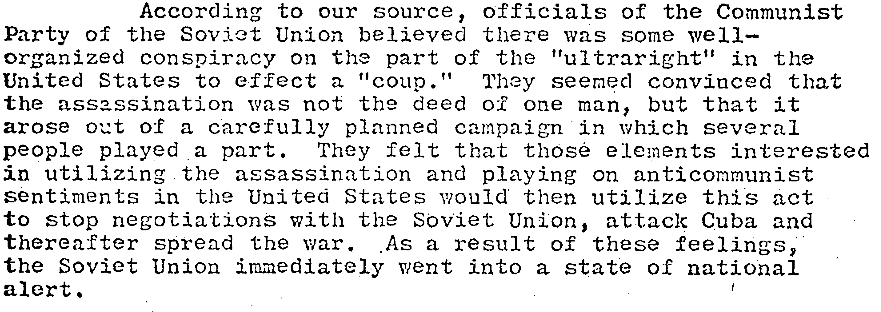

As for the Russian reaction to the JFK assassination, the most recent ARRB releases leave no doubt about where they stood on the matter. In 2017, a CIA note describing Nikita Khrushchev’s feelings about the assassination was declassified. It revealed a May 1964 conversation between the Soviet leader and reporter Drew Pearson, where the head of state said he did not believe American security was so “inept” that Kennedy was killed without a conspiracy. Khrushchev believed the Dallas Police Department to be an “accessory” to the assassination. The CIA source “got the impression that Chairman Khrushchev had some dark thoughts about the American Right Wing being behind this conspiracy.” When Pearson said that Oswald and Ruby both were, “mad” and “acted on his own … Khrushchev said flatly that he did not believe this.”

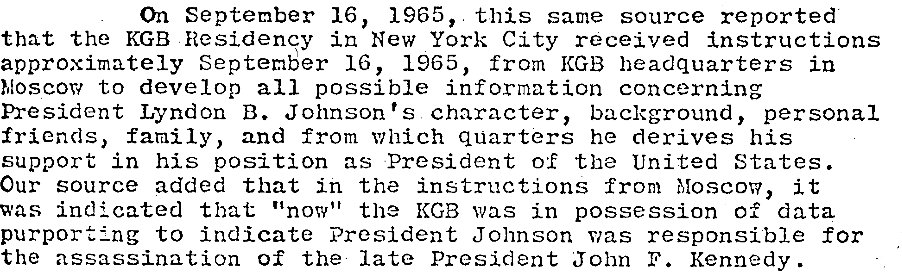

The research community also gained access to a J. Edgar Hoover memo sent to Marvin Watson, Special Assistant to the President on December 2, 1966, which described what Russian intelligence believed about the murder:

The Memo also adds this explosive point made after two years of Russian intelligence efforts that had been intended for internal use only:

We can safely guess that this only hardened Khrushchev’s opinions.

When interviewed by NBC’s Megyn Kelly in 2017, Vladimir Putin stated, “There is a theory that Kennedy’s assassination was arranged by the United States intelligence services,” Putin told Kelly. “So if this theory is correct, and that can’t be ruled out, then what could be easier in this day and age than using all the technical means at the disposal of the intelligence services and using those means to organize some attacks, and then pointing the finger at Russia?”

Though one can question his motives, there is no doubt that the ex-lieutenant colonel in the KGB had easy access to the intelligence on which he could base such a tantalizing statement.

The most vocal foreign leader about the assassination was Fidel Castro.

The Cuban leader was perhaps the first person to remark publicly that something was awry in the JFK case. He learned of the assassination on the day it happened while engaging in diplomatic discussions with one of JFK’s secret envoys, a French journalist named Jean Daniel. Immediately upon getting the news, Castro remarked to his visitor: “This is an end to your mission of peace. Everything is changed.” Later Castro commented: “Now they will have to find the assassin quickly, but very quickly, otherwise, you watch and see, I know them, they will try to put the blame on us for this thing.” A day later, after frantically following all the cables about the subject, the early ones linking Oswald to pro-Communist and Cuban interests, he felt it confirmed a plot to blame him so as to give the U.S. the excuse it needed to invade his country.

Cuba was plunged into crisis-mode, the overthrow of the Island was already a clear and present danger and it would be under assault for decades. Its security and intelligence forces went into even higher gear. Among them, some Cuban exiles in the U.S. who had access to privileged information on plots to remove Castro, which intersected with the one to remove Kennedy— perceived to be the biggest roadblock into regaining an empire to be plundered once again by ruthless opportunists.

The hit team: Was it a mosaic of diverse groups and organizations, or a well-tuned, synchronized network?

One of the biggest problems researchers have in convincing skeptical audiences that there was, in fact, a large-scale conspiracy behind the coup d’état is that the involvement of so many different factions would have been too complex to pull off. In fact, here is what two historians remarked in their correspondence with me when I challenged their writings:

- Was it Cubans, the CIA, the Mafia, Lyndon Johnson, the Federal Reserve . . . many of the villains contradict each other?

- I’m always reminded of the headline in the comedy newspaper, The Onion, which read something like: JFK ASSASSINATED BY CIA, FBI, KGB, MAFIA, LBJ, OSWALD, RUBY, IRS, DEA, DEPT OF ED, DEPT. OF COMMERCE AND MORE! That about sums up the feeling from professional historians about those proposing we rethink the JFK assassination.

Of course, it would have helped to ask who the persons and groups of interest were. Something the Cubans did. Out of all the foreign governments that looked into the assassination, Cuban intelligence efforts were the most persistent and the best connected. Their findings were eventually revealed. Thanks to some of their writings and exchanges with serious assassination researchers, we can better understand how interrelated some of the suspects were before, during and after the assassination. Their stories begin in the early part of the twentieth century.

Cuba pre-revolution: Enrique Cirules, The Mafia in Havana, a Caribbean Mob story, 2010

|

Enrique Cirules (1938 – 18 December 2016) was a Cuban writer. His books include Conversation with the last American (1973), The Other War (1980), The Saga of La Gloria City (1983) Bluefields (1986), Ernest Hemingway in the Romano Archipelago (1999) The Secret life of Meyer Lansky in Havana (2006) and Santa Clara Santa (2006). |

| Enrique Cirules |

|

His The Mafia in Havana won the Literary Critic’s Award in 1994, and its 2010 edition is the basis for most of this section.

This book goes significantly farther than what its title suggests, as it chronicles how a network of imperialist-exploiters from 1930 to the revolution in 1959 plundered the Island. It sheds light on how the foursome of the Mafia, U.S. intelligence, Captains of U.S. industry and the Cuban elite ran a rigged system with an invisible government pulling the strings using Cuban figureheads for the benefit of so few.

The Mafia actually began running alcohol in Cuba in the early 1920s; however, the creation of a large criminal empire began in 1933 when Lucky Luciano tasked Meyer Lansky, the top Mafia financier, to begin a relationship with Fulgencio Batista who by then controlled Cuba’s Armed Forces. Batista used this position to influence Cuban presidents until he was elected president in 1940 and would go on to become a long-lasting American puppet dictator who made off with some 300 million dollars by the time he was forced to leave as Castro and his band of rebels were closing in on Havana.

Cuba was an ideal location for the Mafia: only ninety miles off U.S. shores, virgin territory, with neither laws nor taxes to worry about, and Cuban leaders in their pockets. For a long time the Mafia operations were organized under Lansky who was the number one chieftain in Cuba, drug tsar Santo Trafficante Sr., Amadeo Barletta, and Amletto Batisti who actually established a bank to finance his Mafia interests. By the 1940s, the Mafia was careful to select Cuban nationals to participate in their operations. One wealthy Cuban who did well under this regime was Julio Lobo (AMEMBER-1) who was an important player in the sugar and banking industries. He also connects well with some of the Cubans of interest in the JFK assassination.

By the end of World War II, the Mafia controlled casinos, prostitution, and the drug trade. Cuba was a stopping point for heroin destined to the U.S. and a key market for cocaine. They also began taking over banks they used to finance shady deals, get their hands on Cuban subsidies and launder Cuban and U.S. based rackets. At around the same time they took over important parts of the media. Trafficante even began training undercover agents within Cuban political groups. Barletta at one point was the sole representative of General Motors in Cuba. He also owned media outlets and many businesses.

By far the most powerful of the foursome was Lansky, who is said to have been aware of everything that went on in Cuba. He intimidated all the leaders, including Batista. Lansky always kept a low profile, but he was well known by all the power brokers and key operators who governed the country. He was suspected of having maneuvered to block his ex-boss Luciano from gaining entry on the Island after his expulsion from the U.S. His high rank in the pecking order could be seen by his refusal to allow credit to the Vice-President of the republic in one of the casinos, his snubbing of the Minister of the Interior who sought to exchange greetings with him and by even pressuring Batista himself into protecting Mafia-friendly policies. An invisible government was now in charge of Cuba where profits of the Mafia empire were greater than the rest of the Cuban economy.

By 1956, other U.S. mobsters, including Sam Giancana and Carlos Marcello, wanted in, which led to a bloody mob battle in the U.S. coined the Havana Wars.

U.S. industry leaders took their share of the spoils as the Rockefellers used their banks to quickly take over large segments of the economy in the early 1930s. By the 1950s, Rockefeller interests owned much of the sugar, livestock and mining industries.

Where one could find American imperialism thriving, not far away was Sullivan & Cromwell, the leading international lawyer/lobbyists of the era who joined their clients on Cuban soil and opened doors for others like the Schroeder Bank. Through the Dulles brothers, who were partners in the firm, the symbiosis with U.S. intelligence and government was ensured as John Foster Dulles later became Secretary of State and Allen Dulles would go on to head the CIA.

The free reign in Cuba could not have worked without the efforts of U.S. intelligence, who became the gatekeepers of the Island as early as 1902 when they infiltrated the Cuban military. By the 1930s, they were using Mafiosi, journalists, lawyers, businessmen, politicians all over the Island. During the war years, Franklin Roosevelt became alarmed by the trend towards Marxism and was particularly worried about Cuba. The key diplomat he designated to ensure that Batista would squash any rebellion was no other than Meyer Lansky, because of his excellent relations with the dictator.

Fearing a revolt, the U.S. took steps to fake a demonstration of democracy to give the Cuban people the impression that they had a voice. They convinced Batista to call an election in 1944 that the U.S. rigged to place another puppet, Doctor Ramon Martin (AMCOG-3), in power. The new leader could not take two steps without a Batista henchman breathing down his neck. During this era, Carlos Prío would have a stint as prime minister while Tony Varona was second in command—both of whom would go on to become key leaders of Cuban exiles in Miami. The invisible government later created a crisis around these political leaders so that Batista could come back in 1952 and save the day—so many smoke screens all marketed to the populace as a showcase of democracy by the Mafia and CIA-run media.

By 1955, when a rebellion threat was growing again, Lyman Kirkpatrick, inspector general of the CIA, was making repeated trips to Cuba to help Batista, who had been scouted by the U.S. in the early 1940s. Cirules produced a letter from Allen Dulles to Batista where he reminds him of their recent meeting and the decision to have the new head of the Bureau of Repression of Communist Activities, General Tamayo, come to Washington to receive special training.

In 1958, Castro took over and the Imperialist-Finance-Intelligence-Mafia network was forced out with many of their Cuban protégées. But not without a futile last stand from Tony Varona, who haplessly tried to lead the police forces.

As we will see, many of the persons of interest in the JFK assassination did not just join forces sometime around 1962 to develop a plot to remove JFK. They were part of a well-connected network of very cunning people in existence for many years, if not decades, who desperately shared the same goal to regain their former power and wealth, who were very secretive, who planned the removal of Castro and who came to see JFK as an obstacle and a traitor. For some of them, their obsessions and their violence persisted for decades.

Journalists and historians never asked themselves who these people whose names kept popping up from deep event to deep event were. If they had looked into their backgrounds, they would have discovered a ruthless cast of characters, who were linked to the Mafia and/or intelligence and/or U.S. imperialist forces and/or the Cuban elite. This network, which scattered away from Cuba in 1958, would quickly coalesce again in Miami and spread to New Orleans, Dallas and other American cities. What followed was an onslaught of assassination attempts against Castro, acts of terrorism that would span 40 years and a regime change in the U.S. on November 22, 1963, during lunchtime in full public view on a sunny day.

American style state-sponsored terrorism

The network of many of the persons of interest in the JFK assassination had its origins some thirty years before the revolution, and while many faces changed over time, the gangs lived on for decades with a moral compass that was pointed towards hell.

Before discussing this partnership and Dealey Plaza, it is worth underscoring the forty years of fury unleashed on Cuba, and its friends, in the form of covert action according to the perpetrators, terrorist acts according to the victims. We will let the reader decide. The following is a partial list:

- In March 1960, the Belgian steamship La Courbe loaded with grenades was blown up in Havana, killing 101 and injuring over 200;

- In 1961, a volunteer teacher and a peasant were captured and tortured to death;

- Also in 1961, explosives in cigarette packages were used to blow up a store;

- In 1962, the Romero farming family were murdered by counter-revolutionaries;

- In 1964, a Spanish supply ship was attacked;

- In 1965, led by Orlando Bosch, terrorists bombed sugar cane crops;

- In 1970, two fishing vessels were hijacked and their crews of 12 kidnapped;

- In 1981, dengue fever broke out in Cuba killing 151 people, including 101 children; terrorist Eduardo Arocena admitted to the crime in a federal court in New York;

- In 1994, terrorists from Miami entered Cuba and murdered a Cuban citizen;

- In 1997, explosives were detonated in the Copacabana, killing an Italian tourist;

- In 2003, the Cuban vessel Cabo Corriente was hijacked.

The targets were not only confined to Cuban territory:

- During the years that followed the revolution, British, Soviet and Spanish ships carrying merchandise to and from Cuba were attacked;

- In 1972, Cuban exiles blew up a floor where there was a Cuban trade mission in Montreal killing one person;

- In 1974, Orlando Bosch admitted sending letter bombs to Cuban embassies in Lima, Madrid and Ottawa;

- The terrorists were particularly active in 1976: explosions were set off in the Cuban embassy in Madrid and the offices of a Cuban aviation company; two Cuban diplomats were kidnapped, tortured and assassinated; two other Cuban diplomats were murdered in Lisbon; a bomb exploded in a suitcase just before being put on a Cuban airline in Jamaica; terrorists downed a Cuban airliner that had departed from Barbados, killing all 73 aboard.

Even U.S. soil was fair game for the terrorist cells:

- In 1975, a Cuban moderate living in Miami was shot and killed;

- Cuban diplomats were killed in New Jersey and New York City in 1979 and 1980;

- In 1979, a TWA plane was targeted, but the bomb went off in a suitcase before departure.

Overall, Cuba counted 3500 who died and 2000 who were injured because of these acts of aggression to go along with billions of dollars in damage.

The terrorists, who had become full-fledged Americans, were well known to authorities but acted with impunity:

- Orlando Bosch (AMDITTO-23) told the Miami press that “if we had the resources, Cuba would burn from one end to the other.”

- There was not much remorse if we base ourselves on what Guillermo Novo Sampol had to say after a Cuban airline exploded in midflight, killing 73 passengers: “When Cuba pilots, diplomats or members of their family die—this always makes me happy.”

- Convicted terrorist Luis Posada Carilles (AMCLEVE-15) confirmed in a New York Times interview that they had received training in the use of explosives by the CIA.

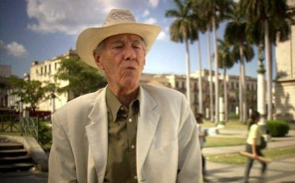

Fabian Escalante’s investigation

|

Fabian Escalante joined the Department of State Security in 1959. Escalante was head of a counter-intelligence unit and also part of a team investigating a CIA operation called Sentinels of Liberty, an attempt to recruit Cubans willing to work against Castro. At the request of the U.S., he presented the HSCA with a report on Cuban findings about the JFK assassination that was never published by the committee because of some of the information it contained. He is recognized as a leading authority on the CIA in Cuba and Latin America. |

| Fabian Escalante |

|

Some of his critics state that he seems to base most of his analysis on the work of American researchers and that he is biased. In his defense, it is important to note that very few American investigators have gone through as much committee-based research as Escalante. While it is true that some of his sources like Tosh Plumlee and Chuck Giancana are not convincing for many, he himself tempers his observations by often emphasizing that more research should be done to follow-up on leads ignored by U.S. media and intelligence. His exchanges with people like Dick Russell and Gaeton Fonzi helped push the analysis forward. As we will see, some of his insights certainly go an awful lot farther than what we can see on CNN. In the following sections, we will look at Escalante’s work, which will be at times bolstered by findings from other sources that dovetail with his analysis.

Cuban intelligence, though lacking in structure during the days that followed the revolution, had privileged access to informants in the U.S. and Cuba who at times penetrated exile groups in the U.S. and their antennas on the Island. They also captured combatants who revealed secrets they kept about the assassination. Furthermore, they were able to obtain information from their Russian counterparts. Finally, they kept abreast of all U.S. research in the subject to a degree far superior to what historians or mainstream media ever did. By 1965, a Cuban spy, Juan Felaifel Canahan, had infiltrated CIA special missions groups in Miami and won Cuban exile leader Manuel Artime’s confidence. Artime was involved in the plot to assassinate Castro code-named AMLASH, which brought together the CIA, Mafia, and Cuban exiles in the master plan. It was only after 1975, after the publication of a Church Committee report, that they suspected that this partnership was behind the assassination of JFK.

In 1993, during his retirement, after launching a security studies center, he again put together all the pieces of the puzzle he could put his hands on. His research would be enriched by ARRB releases. Even Escalante admits that he does not have full access to all the Cuban files, but what he does know is worth listening to.

In 1995 Wayne Smith, chief of the Centre for International Policy in Washington, arranged a meeting on the assassination of John F. Kennedy, in Nassau, Bahamas. Others in attendance were: Gaeton Fonzi, Dick Russell, Noel Twyman, Anthony Summers, Peter Dale Scott, John M. Newman, Jeremy Gunn, John Judge, Andy Kolis, Peter Kornbluh, Mary and Ray LaFontaine, Jim Lesar, Russ Swickard, Ed Sherry, and Gordon Winslow. In 2006, his book analyzing the assassination, JFK: The Cuba Files, was published. While some of Cuba’s sources are deemed contestable by some reputable researchers, it is clear that they had access to sources that not even the FBI could have tapped. Their findings may not be perfect but they certainly are more fact-based and up to date than anything a historian will find in the Warren Commission report.

The network factions

In JFK: The Cuba Files, Escalante describes how the departure of Cuban exiles, CIA operators and Mafiosi from the Island, where they had originally joined forces, gave birth to what he called the CIA and Mafia’s “Cuban American Mechanism”. Its members were based mostly in Miami and were trained to do a lot of the dirty work to get their empire back in a manner that was plausibly deniable by their supervisors.

Most researchers are aware of the influence the business elite had on U.S. foreign policy. It is now fully accepted that regime change in the 1950s in the Middle East was for the benefit of U.S. and British oil magnates, and the removal of Arbenz in Guatemala was asked for by United Fruit and made good on by Dulles and a cadre of CIA officers who mastered the art of delivering a coup. Many of these specialists were involved in covert actions against Cuba and some became persons of interest in the JFK assassination.

Escalante demonstrates the importance of the corporate elite in dictating U.S. policy by quoting a statement made by Roy Robottom, Assistant Undersecretary of State for Hemispheric Affairs: “… In June 1959 we had taken the decision that it was not possible to achieve our objectives with Castro in power … In July and August, we had been drawing up a program to replace Castro. However, certain companies in the United States informed us during that period that they were achieving some progress in negotiations, a factor that led to a delay …” By the end of 1959, J.C. King, head of the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division, recommended the assassination of Castro. In March 1960, Eisenhower approved the overthrow under a project codenamed Pluto.

The Mechanism assumed a life of its own after the failed Bay of Pigs in 1962, and held JFK responsible for the debacle.

Structuring the Cuban exiles

The author describes how “venal officials, torturers, and killers from the Batista Regime fled Cuba and sought refuge in the United States” to escape justice in Cuba, and began forming groups with an eye to re-taking the Island. In this chaos, the Mafia, the CIA, and the U.S. State Department would quickly aid them. This is what also gave birth to the Miami Cuban Mafia. Some of the prominent leaders were of course Batista puppets, including Carlos Prío Socarrás, who was President of Cuba from 1948-52, and Tony Varona, who was Vice President under Prío, also a Mafia associate. They led the Revolutionary Democratic Front (FRD) (AMCIGAR), an umbrella group for hundreds of smaller groups. The FRD was eventually replaced by the Cuban Revolutionary Council (CRC) (AMBUD) which was conceived by the CIA as a government in waiting.

The command structure of the Cuban exiles was focused at first on the Bay of Pigs invasion. After this fiasco, in 1961, the management of the Cuban exiles centered on acts of sabotage and terrorism under the Operation Mongoose program led by Edward Lansdale and William Harvey. Harvey was later exiled to Rome after almost messing up the delicate Missile Crisis negotiations when he intensified covert actions against Cuba.

In the early 1960s, JMWAVE in Miami became the largest CIA station with over 400 agents overseeing some 4000 Cuban exile assets, Mafia partnerships and soldiers of fortune. The Cuban exile counter-revolutionary organizations were so numerous (over 400) and weirdly connected that Richard Helms of the CIA had to send Bobby Kennedy a handbook to explain the situation. Some groups were more political in nature, others military. Many had antennas in Cuba.

The handbook describes the unstable structure as follows:

Counter-revolutionary organizations are in fact sponsored by Cuban intelligence services for the purpose of infiltrating “unities” creating provocations, collecting bona fide resistance members into their racks and taking executive action against them. It is possible that the alleged “uprising” on August 1962, which resulted in the well-nigh final declination of the resistance ranks, was the result of just such G-2 activities.Guerrilla and sabotage activities have been further reduced by lack of external support and scarcity of qualified leadership. Exile leaders continue to hold meetings, to organize to expound plans of liberation, and to criticize the United States “do nothing policy.”But it is the exceptional refugee leader who has the selflessness to relinquish status of leadership of his organization or himself by integrating into a single strong unified and effective body. “Unidades” and “Juntas” are continually being created to compete with one another for membership and U. S. financial support. They print impressive lists of member movements, which in many instances are only “pocket” or paper groups. Individuals appear to leadership roles in several or more movements simultaneously, indicating either a system of interlocking directorates or pure opportunism.

In order to place in perspective the hundreds of counter-revolutionary groups treated herein, it is necessary to understand the highly publicized CRCConsejo Revolucionario Cubano—Cuban Revolutionary Council). The CRC is not included in the body of this handbook because it is not actually a counter-revolutionary group, but rather a superstructure, which sits atop all the groups willing to follow its direction and guidance in exchange for their portions of U. S. support for which the CRC is the principal channel.

The CRC was originally known as the FRD (Frente Revolucionary Democratica) and was not officially called CRC or Consejo until the fall of 1961.The Consejo has always been beset with factionalism and internal dissension. It and its leader Dr. Jose Miro Cardona have been continually criticized by Cuban exile leaders for a “do nothing” policy. The CRC does not participate in activities within Cuba but acts as a coordinating body for member organizations. It has delegations in each Latin American country as well as in France and Spain. Besides the main office located in Miami, it has offices in Washington, New York, and New Orleans. CRC gives financial support to member groups for salaries, administrative expenses and possible underground activities in Cuba.

The following is a list of the groups (the handbook gives additional information on each group-membership numbers in U.S. and Cuba, key members, year of foundation etc.):

Part I: Leading Organizations [7 groups]

- Movimiento Revolucionario 30 de Noviembre – 30 Nov, MRTN, M-30-11 — 30 November Revolutionary Movement

- Movimiento de Recuperacion Revolucionario – MRR — Movement for Revolutionary Recovery

- Unidad Revolucionaria – U. R., Unidad — Revolutionary Unity

- Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil D.R.E. — Students Revolutionary Directorate (DRE) (

- Rescate Democratico Revolucionario RDR — Revolutionary Democratic Rescue

- Movimiento Revolucionario del Pueblo — Revolutionary Movement of the People

- Movimiento Democrata Cristiano MDC — Christian Democrat Movement

Part II describes those organizations currently judged to be above average in importance. [52 groups]. See appendix 1 (note: in this author’s opinion Alpha 66 in this group became very important).

Part III describes those judged to be of little apparent value, paper organizations, or small disgruntled factions.

The CIA ensured funding to the tune of $3 million a year according to CIA operative E. Howard Hunt. U.S. militia forces recruited some of the other Cuban exiles. Two CIA stations were key in the destabilization efforts: one in Mexico City, where David Phillips played a key role; the other in Madrid, headed by James Noel. Both spies were very active in Cuba before the revolution.

Captain Bradley Ayers trained commandos. Training grounds could be found in Florida and near New Orleans, where Guy Banister, David Phillips, and David Ferrie were seen in the company of Cuban exiles and soldiers of fortune. According to Escalante, the Mafia, represented by John Roselli, exercised control as an executive and got involved as a supplier of weaponry. The Mafia could even count on CIA watercraft to bring in narcotics and arms. Finally, as Escalante continues, organizations created by private citizens interested in freeing “Cuba” popped up in various cities seeking additional and illegal funds for the huge cost of the operation and lobbying effort. Escalante cites as examples: in his native Texas, George H. W. Bush as one of those “outstanding Americans”, along with Admiral Arleigh Burke and his Committee for a Free Cuba; and in New Orleans, there was the Friends of Democratic Cuba.

A repressive police and intelligence apparatus, called Operation 40, was formed to cleanse captured territories of communists and other adversaries. Mercenaries like Gerry Patrick Hemming, through his group called Interpen, and Frank Sturgis and his International Anticommunist Brigade, offered their services for waging the secret war. Private citizens and corporations joined the Mafia by getting involved in financing operations and launching NGOs such as the Friends of Democratic Cuba in New Orleans, located at 544 Camp Street. Here, Lee Harvey Oswald would eventually set up his Fair Play for Cuba Committee office and hob-nob with Cuban exiles he was supposedly at odds with.

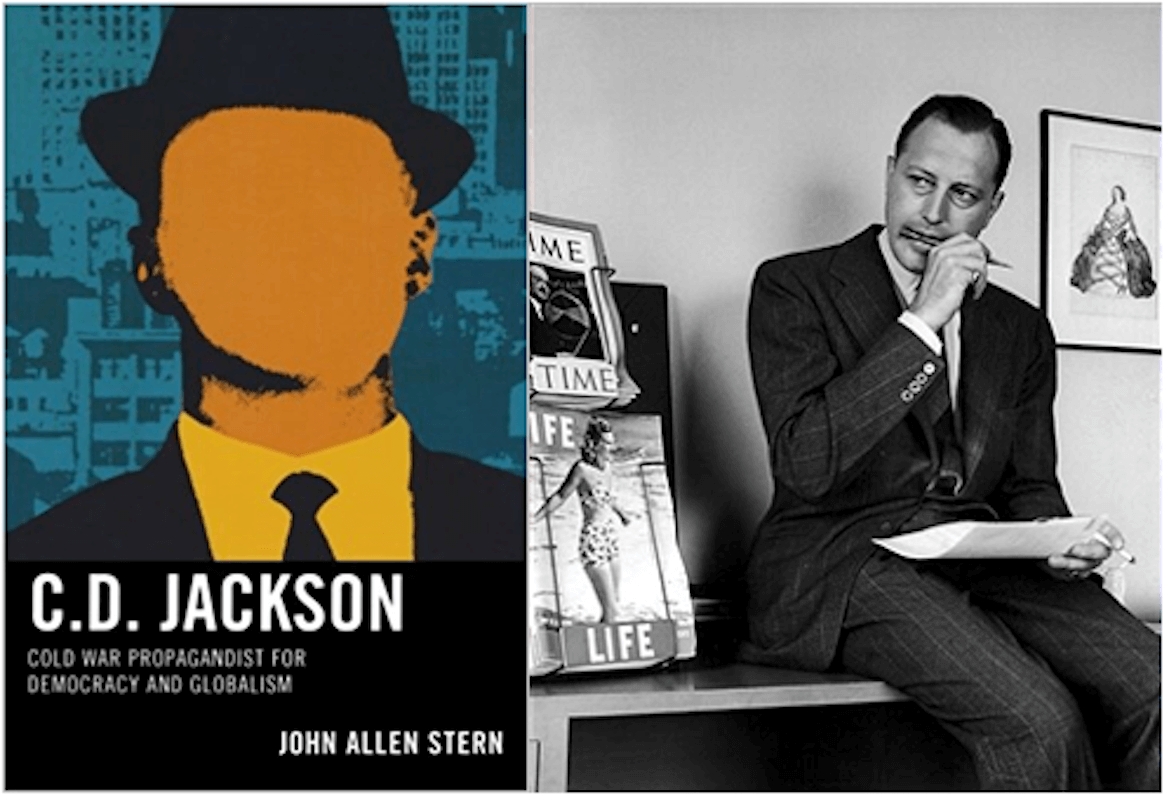

Operation Tilt, undertaken in 1963, and sponsored by Clare Boothe Luce (Life Magazine) and William Pawley (QDDALE), who were two close friends of Allen Dulles, is a clear example of how big business, Mafia, Cuban exiles and intelligence teamed up on an anti-Castro mission that went against JFK policy. Described by Gaeton Fonzi, among others, the scheme can only be seen as reckless and quasi-treasonous. In the winter of 1962, Eddie Bayo (Eduardo Perez) claimed that two officers in the Red Army based in Cuba wanted to defect to the United States. Bayo added that these men wanted to pass on details about atomic warheads and missiles that were still in Cuba despite the agreement that followed the Cuban Missile Crisis. Bayo’s story was eventually taken up by several members of the anti-Castro community, including Nathaniel Weyl, William Pawley, Gerry P. Hemming, John Martino, Felipe Vidal Santiago and Frank Sturgis. Pawley became convinced that it was vitally important to help get these Soviet officers out of Cuba. William Pawley contacted Ted Shackley at JMWAVE. Shackley decided to help Pawley organize what became known as Operation Tilt or the Bayo-Pawley Mission. He also assigned Rip Robertson, a fellow member of the CIA in Miami, to help with the operation. David Sanchez Morales, another CIA agent, also became involved in this attempt to bring out these two Soviet officers.

On June 8, 1963, a small group, including William Pawley, Eddie Bayo, Rip Robertson, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, John Martino. Richard Billings and Terry Spencer, a journalist and photographer working for Life Magazine, boarded a CIA flying boat. After landing off Baracoa, Bayo and his men got into a 22-foot craft and headed for the Cuban shore. The plan was to pick them up with the Soviet officers two days later. However, Bayo and his men were never seen again. It was rumored that he had been captured and executed. However, his death was never reported in the Cuban press.

William Pawley’s background is particularly revealing. Gaeton Fonzi points out in his book, The Last Investigation: “Pawley had also owned major sugar interests in Cuba, as well as Havana’s bus, trolley and gas systems and he was close to both pre-Castro Cuban rulers, President Carlos Prío and General Fulgencio Batista.” (Pawley was one of the dispossessed American investors in Cuba who early on tried to convince Eisenhower that Castro was a Communist and urged him to arm the exiles in Miami.)

Lee Harvey Oswald and the subterfuge according to Escalante

Like most Americans, the Cubans found Oswald’s murder by a nightclub owner in the basement of the Dallas Police headquarters simply too convenient. His immediate portrayal as communist and pro-Castro made them strongly suspect that this was all a ruse to attack Cuba.

Within days of the assassination, Castro stated the following: “ … It just so happened that in such an unthinkable thing as the assassination a guilty party should immediately appear; what a coincidence, he (Oswald) had gone to Russia, and what a coincidence, he was associated with FPCC! That is what they began to say … It just so happens that these incidents are taking place precisely at a time when Kennedy was under heavy attack by those who felt his Cuba policy was weak …”

When Escalante analyzed all they could find on Oswald (post-assassination cryptonym: GPFLOOR), he was led to the following hypothesis:

- Oswald was an agent of the U.S. intelligence service, infiltrated into the Soviet Union to fulfill a mission.

- On his return, he continued to work for U.S. security services.

- Oswald moved to New Orleans in April 1963 and formed links with Cuban organizations and exiles.

- In New Orleans, Oswald received instructions to convert himself into a sympathizer with the Cuban Revolution.

- Between July and September 1963, Oswald created evidence that he was part of a Cuba-related conspiracy.

- In the fall of 1963, Oswald met with a CIA officer and an agent of Cuban origin in Dallas, Texas, to plan a covert operation related to Cuba.

- In September 1963, Oswald met with the Dallas Alpha 66 group and tried to compromise Cuban exile Silvia Odio.

- Oswald attempted to travel to Cuba from Mexico.

- Oswald was to receive compromising correspondence from Havana linking him to the Cuban intelligence service.

- The mass media, directed by the CIA and Mafia’s “Cuban American Mechanism,” was primed to unleash a far-reaching campaign to demonstrate to the U.S. public that Cuba and Fidel Castro were responsible for the assassination.

Through his investigation, he found evidence of the parallel nature of plans of aggression against Cuba and the assassination of Kennedy. The Cubans simply found that there were too many anti-Castro Cuban exiles in Oswald’s realm, suggesting a role in a sheep dipping operation. They show that his history as a provocateur in his pre-Russia infiltration days was similar to his actions in New Orleans, and that James Wilcott, a former CIA officer in Japan, testified to the HSCA that “ … Oswald was recruited from the military division with the evident objective of turning him into a double agent against the Soviet Union …” Escalante also received material on Oswald in 1977 from their KGB representative in Cuba, Major General Piotr Voronin. Then, in 1989, while in the Soviet Union, he met up with Pavel Iatskov, colonel of the first Directorate of the KGB, who had been in Mexico City during Oswald’s visit.

Iatskov stated the following: “At the end of the 1970s, when the investigation into the Kennedy assassination was reopened, I was in Moscow, and at one point … one of the high-ranking officers from my directorate … commented that Oswald had been a U.S. intelligence agent and that his defection to the Soviet Union was intended as an active step to disrupt the growing climate of détente …” They speculated that Oswald was there to lend a blow to Eisenhower’s peace endeavors by giving away U-2 military secrets, which dovetailed into the downing of Gary Powers a few short weeks before a crucial Eisenhower/ Khrushchev summit.

It was through some of their intelligence sources in the U.S. that the Cubans found out about the formation of the Friends of Democratic Cuba and its location in the famous Camp Street address. They identified Sergio Arcacha Smith, Carlos Bringuier and Frank Bartes as exiles who were often there and who were visited by Orlando Bosch, Tony Cuesta, Antonio Veciana, Luis Posada Carilles, Eladio del Valle, Manual Salvat, and others. This same source recognized Oswald as someone who was in a safe house in Miami in mid-1963. Escalante believes that Oswald did in fact visit Mexico City with the intention to try to get into Cuba, to push the incrimination of Castro even further.

Letters from Cuba to Oswald—proof of pre-knowledge of the assassination

In JFK: the Cuba Files, a thorough analysis of five bizarre letters that were written before the assassination in order to position Oswald as a Castro asset is presented. It is difficult to sidestep them the way the FBI did. The FBI argued that they were all typed from the same typewriter, yet supposedly sent by different people. Which indicated to them that it was a hoax, perhaps perpetrated by Cubans wanting to encourage a U.S. invasion.

However, the content of the letters and timeline prove something far more sinister according to Cuban intelligence. The following is how John Simkin summarizes the evidence:

The G-2 had a letter, signed by Jorge that had been sent from Havana to Lee Harvey Oswald on 14th November, 1963. It had been found when a fire broke out on 23rd November in a sorting office. “After the fire, an employee who was checking the mail in order to offer, where possible, apologies to the addressees of destroyed mail, and to forward the rest, found an envelope addressed to Lee Harvey Oswald.” It is franked on the day Oswald was arrested and the writer refers to Oswald’s travels to Mexico, Houston and Florida …, which would have been impossible to know about at that time!

It incriminates Oswald in the following passage: “I am informing you that the matter you talked to me about the last time that I was in Mexico would be a perfect plan and would weaken the politics of that braggart Kennedy, although much discretion is needed because you know that there are counter-revolutionaries over there who are working for the CIA.”

Escalante informed the HSCA about this letter. When he did this, he discovered that they had four similar letters that had been sent to Oswald. Four of the letters were post-marked “Havana”. It could not be determined where the fifth letter was posted. Four of the letters were signed: Jorge, Pedro Charles, Miguel Galvan Lopez and Mario del Rosario Molina. Two of the letters (Charles & Jorge) are dated before the assassination (10th and 14th November). A third, by Lopez, is dated 27th November, 1963. The other two are undated.

Cuba is linked to the assassination in all the letters. In two of them an alleged Cuban agent is clearly implicated in having planned the crime. However, the content of the letters, written before the assassination, suggested that the authors were either “a person linked to Oswald or involved in the conspiracy to execute the crime.”

This included knowledge about Oswald’s links to Dallas, Houston, Miami and Mexico City. The text of the Jorge letter “shows a weak grasp of the Spanish language on the part of its author. It would thus seem to have been written in English and then translated.

Escalante adds: “It is proven that Oswald was not maintaining correspondence, or any other kind of relations, with anyone in Cuba. Furthermore, those letters arrived at their destination at a precise moment and with a conveniently incriminating message, including that sent to his postal address in Dallas, Texas …. The existence of the letters in 1963 was not publicized or duly investigated, and the FBI argued before the Warren Commission to reject them.”

Escalante argues: “The letters were fabricated before the assassination occurred and by somebody who was aware of the development of the plot, who could ensure that they arrived at the opportune moment and who had a clandestine base in Cuba from which to undertake the action. Considering the history of the last 40 years, we suppose that only the CIA had such capabilities in Cuba.”

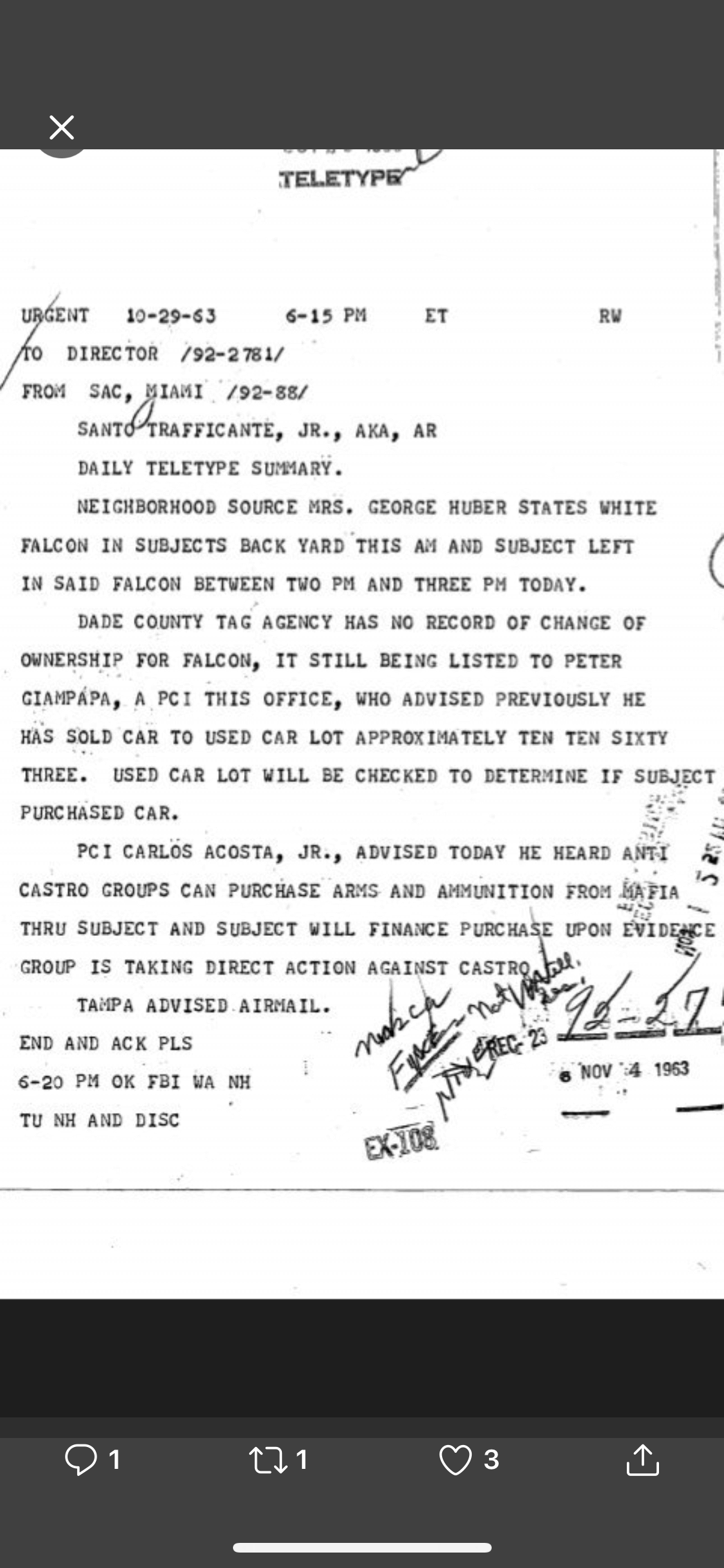

Jack Ruby’s links to Trafficante

Escalante is of the opinion that Jack Ruby and Trafficante were acquainted and that Ruby did in fact visit Trafficante when the latter was detained in Cuba in 1959. Here is his rationale:

- Ruby’s close friend Louis McWillie ran Trafficante’s Tropicana Casino;

- Ruby’s visits to Cuba after accepting invitations from McWillie, coincide with the detention of Trafficante and other Mafiosi;

- McWillie told the HSCA that he made various visits to the Tiscornia detention center during Ruby’s visits;

- After Ruby’s stays in Miami, he met with Meter Panitz (partner in the Miami gambling syndicate) in Miami. McWillie spoke with Panitz shortly before the visits. Trafficante was a leading gangster in Florida. Ruby kept this hidden from the Warren Commission;

- Ruby’s entries and exits logistics dispel any idea that he went to Cuba for vacation purposes;

- Ex-gun-runner and Castro friend Robert McKeown told the HSCA that Ruby approached him to try and get Castro to meet him in the hope of getting the release of three prisoners. McKeown also had contacts with Prío before and after the revolution and had met Frank Sturgis;

- John Wilson Hudson, a British journalist, was also detained in Tiscornia at the same time as Trafficante (confirmed by Trafficante). Wilson gave information to the U.S. embassy in London recalling an American gangster-type called Ruby had visited Cuba in 1959 and had frequently met an American gangster called Santo. Prison guard Jose Verdecia confirmed the visits of Trafficante by McWillie and Ruby when shown a photo. He also confirmed the presence of a British journalist.

Operation 40

“We had been operating a damned Murder Inc. in the Caribbean.”

~ President Johnson

In 1973, after the death of Lyndon Johnson, The Atlantic published an article by a former Johnson speechwriter named Leo Janos. In “The Last Days of the President,” LBJ not only made this stunning statement but also expressed a highly qualified opinion that a conspiracy was behind the murder of JFK: “I never believed that [Lee Harvey] Oswald acted alone, although I can accept that he pulled the trigger.” Johnson thought such a conspiracy had formed in retaliation for U.S. plots to assassinate Fidel Castro; he had found after taking office that the government “had been operating a damned Murder Inc. in the Caribbean.” It is very likely that Johnson garnered this information from reading the CIA Inspector General Report on the plots to kill Castro.

There is compelling evidence that it is through Operation 40 that some of the assassins that Johnson may have been referring to received their training and guidance. The existence of this brutal organization of hit men was confirmed to the Cuban G-2 by one of the exiles they had captured: “The first news that we have of Operation 40 is a statement made by a mercenary of the Bay of Pigs who was the chief of military intelligence of the invading brigade and whose name was Jose Raul de Varona Gonzalez,” says Escalante in an interview with Jean-Guy Allard:

In his statement this man said the following: in the month of March, 1961, around the seventh, Mr. Vicente Leon arrived at the base in Guatemala at the head of some 53 men saying that he had been sent by the office of Mr. Joaquin Sanjenis (AMOT-2), Chief of Civilian Intelligence, with a mission he said was called Operation 40. It was a special group that didn’t have anything to do with the brigade and which would go in the rearguard occupying towns and cities. His prime mission was to take over the files of intelligence agencies, public buildings, banks, industries, and capture the heads and leaders in all of the cities and interrogate them. Interrogate them in his own way.

The individuals who comprised Operation 40 had been selected by Sanjenis in Miami and taken to a nearby farm “where they took some courses and were subjected to a lie detector.” Joaquin Sanjenis was Chief of Police in the time of President Carlos Prío. Recalls Escalante: “I don’t know if he was Chief of the Palace Secret Service but he was very close to Carlos Prío. And, in 1973 he dies under very strange circumstances. He disappears. In Miami, people learn to their surprise—without any prior illness and without any homicidal act—that Sanjenis, who wasn’t that old in ‘73, had died unexpectedly. There was no wake. He was buried in a hurry.”

Another Escalante source concerning Operation 40 was one of its members and a Watergate burglar: “And after he got out of prison, Eugenio Martinez came to Cuba. Martinez, alias ‘Musculito,’ was penalized for the Watergate scandal and is in prison for a time. And after he gets out of prison—it’s the Carter period, the period of dialogue, in ‘78, there is a different international climate—Eugenio Martinez asks for a contract and one fine day he appears on a boat here … and of course he didn’t make any big statements, he didn’t say much that we didn’t know but he talked about those things, about this Operation 40 group, about what they had done at the Democratic Party headquarters …”

In the Cuba Files, Escalante underscores a reference to Operation 40 by Lyman Fitzpatrick, CIA Inspector General, in his report on the Bay of Pigs: “…the counter-intelligence and security service which, under close project control, developed into an efficient and valuable unit in support of the FRD, Miami base, and the project program. By mid-March 1961, this security organization comprised 86 employees of whom 37 were trainee case officers, the service having graduated four classes from its own training classes, whose instructor was (censored) police officer. (Probably Joaquin Sanjenis)”

A memo by Arthur Schlesinger Jr. refers to this organization and its dark mission:

Schlesinger’s Memo June 9, 1961

MEMORANDUM FOR MR. RICHARD GOODWIN

Sam Halper, who has been the Times correspondent in Habana and more recently in Miami, came to see me last week. He has excellent contacts among the Cuban exiles. One of Miro’s comments this morning reminded me that I have been meaning to pass on the following story as told me by Halper. Halper says that CIA set up something called Operation 40 under the direction of a man named (as he recalled) Captain Luis Sanjenis, who was also chief of intelligence. (Could this be the man to whom Miro referred this morning?) It was called Operation 40 because originally only 40 men were involved: later the group was enlarged to 70. The ostensible purpose of Operation 40 was to administer liberated territories in Cuba. But the CIA agent in charge, a man known as Felix, trained the members of the group in methods of third degree interrogation, torture and general terrorism. The liberal Cuban exiles believe that the real purpose of Operation 40 was to “kill Communists” and, after eliminating hard-core Fidelistas, to go on to eliminate first the followers of Ray, then the followers of Varona and finally to set up a right-wing dictatorship, presumably under Artime. Varona fired Sanjenis as chief of intelligence after the landings and appointed a man named Despaign in his place. Sanjenis removed 40 files and set up his own office; the exiles believe that he continues to have CIA support. As for the intelligence operation, the CIA is alleged to have said that, if Varona fired Sanjenis, let Varona pay the bills. Subsequently Sanjenis’s hoods beat up Despaign’s chief aide; and Despaign himself was arrested on a charge of trespassing brought by Sanjenis. The exiles believe that all these things had CIA approval. Halper says that Lt Col Vireia Castro (1820 SW 6th Street, Miami; FR 4 3684) can supply further details. Halper also quotes Bender as having said at one point when someone talked about the Cuban revolution against Castro: “The Cuban Revolution? The Cuban Revolution is something I carry around in my check book. Nice fellows.

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.

Frank Sturgis, one of its members and a Watergate burglar, allegedly told author Mike Canfield: “this assassination group (Operation 40) would upon orders, naturally, assassinate either members of the military or the political parties of the foreign country that you were going to infiltrate, and if necessary some of your own members who were suspected of being foreign agents … We were concentrating strictly in Cuba at that particular time.”

In November 1977, CIA asset and ex-Sturgis girlfriend, Marita Lorenz gave an interview to the New York Daily News in which she claimed that a group called Operation 40, that included Orlando Bosch and Frank Sturgis, were involved in a conspiracy to kill both John F. Kennedy and Fidel Castro. “She said that they were members of Operation 40, a secret guerrilla group originally formed by the CIA in 1960 in preparation for the Bay of Pigs invasion … Ms. Lorenz described Operation 40 as an ‘assassination squad’ consisting of about 30 anti-Castro Cubans and their American advisors. She claimed the group conspired to kill Cuban Premier Fidel Castro and President Kennedy, whom it blamed for the Bay of Pigs fiasco … She said Oswald … visited an Operation 40 training camp in the Florida Everglades. The idea of Oswald, or a double, being in Florida is not far-fetched. The 1993 PBS Frontline documentary “Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald?” had a photo of Oswald in Florida, which they conspicuously did not reveal on the program.

In Nexus, Larry Hancock not only provides another confirmation of this outfit’s existence but describes part of its structure and its role: Time correspondent Mark Halperin stated that Operation 40 members “had been trained in interrogation, torture, and general terrorism. It was believed they would execute designated Castro regime members and Communists. The more liberal and leftist exile leaders feared that they might be targeted following a successful coup.”

Hancock also asserts that “documents reveal that David Morales, acting as Counter-intelligence officer for JMARC, had selected and arranged for extensive and special training of 39 Cuban exiles, designated as AMOTs …. Sanjenis was the individual who recruited Frank Sturgis … They would identify and contain rabid Castroites, Cuban Communists …” A final confirmation of Operation 40 comes from Grayston Lynch (a CIA officer involved in the Bay of Pigs): “The ship Lake Charles had transported the men of Operation 40 to the Cuban landing area. The men had been trained in Florida, apart from the regular Brigade members, and were to act as a military government after the overthrow of Castro.”

Other than Morales, Sanjenis, Sturgis, and Felix (probably Felix Rodriguez), it is difficult to pin down names of actual members with certainty. This author has not found any documentary traces. But there is no doubt that it existed and that it was a Top Secret project that was rolled over into the Bay of Pigs so that President Kennedy would not know about it. It was so secret that, according to Dan Hardway’s report for the HSCA, Richard Helms commissioned the study on Operation 40 to be done by his trusted aide Sam Halpern. Hardway wrote that only one person outside the Agency, reporter Andrew St. George, ever saw that report. Exactly who was in Operation 40 is a moot point; what is important to retain is that the most militant and violent Cuban exiles were recruited and trained by the CIA to perform covert operations against Cuba, Castro, and anyone who would get in their way no matter what country they were in and no matter who they were.

The Mechanism’s Team Roster: The Big Leagues

Out of the thousands of Cuban exiles living in the U.S., only a select few could be counted on to be part of the covert activities that would be used to remove Castro, and that became useful for the removal of Kennedy. These received special training in techniques used for combat, sabotage, assassinations and psychological warfare. The training would be provided by people such as Morales, Phillips and perhaps some soldiers of fortune.

When analyzing these figures, it is easy to see how many were, or could easily have been, linked to one another before and after the revolution and during the November 22, 1963, period. It is only by understanding the universes of the factions that worked together on that dark day that we can explain how Oswald and Kennedy’s lives came to their tragic ends.

The first 18 persons profiled were considered the most suspicious by the Cuban researchers. Because the Cuban data precedes 2006, we will enrich some of the pedigrees with more current information.

Other persons of interest come from JFK: The Cuba Files and various other sources:

Aftermath of the assassination

“Operation 40 is the grandmother and great-grandmother of all of the operations that are formed later.”

~ Fabian Escalante

The assassination of JFK was a landmark moment in American history. The country would go on to be rocked by a series of scandals that would see public confidence in politicians and media go into a tailspin. LBJ gave us Vietnam and Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Bobby Kennedy and John Lennon saw their freedom of speech rights contested, with extreme prejudice. Watergate, Iran/Contra, George Bush Junior’s weapons of mass destruction, and the Wall Street meltdown would follow. Now even U.S. grounds are the target of foreign rebels who have mastered the art of using terrorism tactics similar to those that were used against Cuba.

The role some of the members of the Mechanism played in future deep events adds credence to what is alleged about them regarding the removal of JFK. Their murderous accomplishments have their roots in the Dulles brothers’ worldviews. Allen Dulles’ protégé E. Howard Hunt became one of Nixon’s plumbers. In 1972, after Arthur Bremer attempted to assassinate presidential candidate George Wallace, Nixon aide Charles Colson asked Hunt to plant evidence in Bremer’s apartment that would frame George McGovern, the Democratic opponent. Hunt claims to have refused. Hunt, with his ex-CIA crony James McCord, and Cuban exiles Bernard Barker, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, together with Frank Sturgis, would all be arrested, and then let off rather easily for their roles in Watergate. Hunt would even demand and collect a ransom from the White House for his silence. In 1985, Hunt would lose the Liberty Lobby trial that, in large part, verified the infamous CIA memorandum from Jim Angleton to Richard Helms stating that they needed to create an alibi for Hunt being in Dallas on November 22, 1963.

Recruited by David Morales in 1967, Felix Rodriguez succeeded in his mission to hunt down and terminate Che Guevara in Bolivia. Rodriguez kept Guevara’s Rolex watch as a trophy. He also played a starring role in the Iran/Contra scandal. In the 1980s, Rodriguez was the bagman in the CIA’s deal with the Medellin cartel and often met with Oliver North. He was also a guest of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush at the White House.

In 1989, Loran Hall and his whole family were arrested for drug dealing.

As discussed earlier, Novo Sampol, Carilles (who also had links to Iran Contra), and Orlando Bosch continued in their roles in American-based terrorist activities for decades. Arrested in Panama, Luis Posada Carriles and Guillermo Novo were pardoned and released by Panama, in August, 2004. The Bush administration denied putting pressure on for the release. The Bush administration cannot deny providing safe haven to Bosch after an arrest in Costa Rica, which saw the U.S. decline an offer by the authorities to extradite Bosch to the United States.

Veciana continued for a while to participate in attempts to assassinate Castro. He eventually outed David Atlee Phillips. For his candor, he was possibly framed and thrown in jail on narcotics trafficking charges. He was also shot at. The Mafia may not have regained their Cuban empire, but they no longer had the Kennedys breathing down their necks. American imperialists and captains of industry set their sights on the exploitation Vietnam, Indonesia, the Middle East, Africa and cashed in on conflicts.

Risky Business

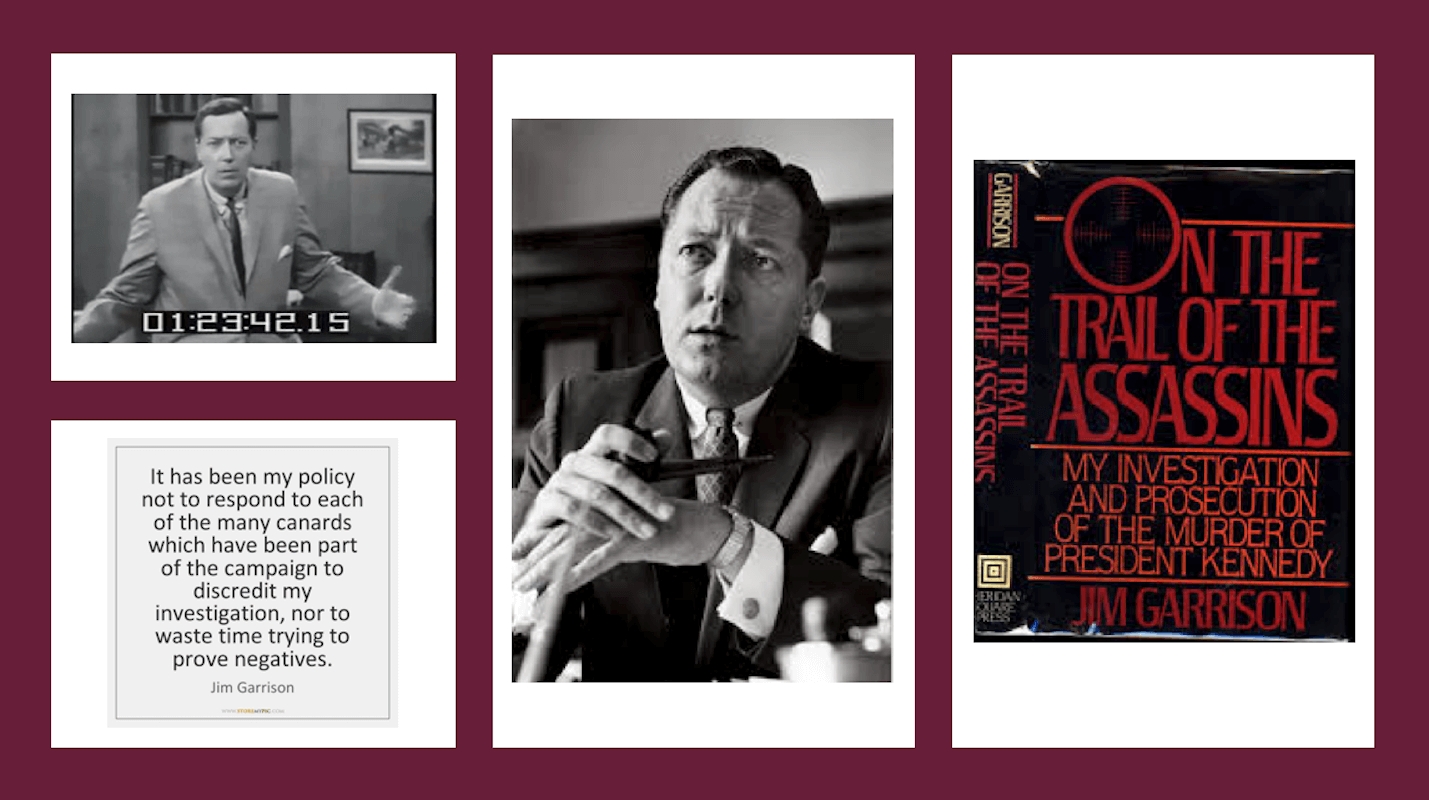

Being a member of the Mechanism also came with its share of professional risks—namely, short life expectancies. When the Warren Commission whitewash was taking place, there were few worries. When the more serious Garrison, Church and HSCA investigations were in full swing, the word cutoff took on a whole new meaning. Intelligence did not seem to bother too much about being linked to rowdy exiles and Mafiosi when it came to removing a communist; the removal of JFK … well, that must have been a different matter. There were many deaths that occurred before 1978 which were timely and varied from suspicious to murderous:

William Pawley died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, in January 1977.

Del Valle was murdered in 1967 when Garrison was tracking him down, shortly after David Ferrie’s suspicious death.

Sanjenis simply vanished in 1973.

Artime, Prío, Masferrer, Giancana, Hoffa, Roselli and Charles Nicoletti were all murdered between 1975 and 1977.

Martino, Harvey and Morales all died of heart attacks.

Out of some 45 network members discussed in this article, 18 did not survive the end of the HSCA investigation, 8 were clearly murdered and 7 of other deaths were both timely and suspicious.

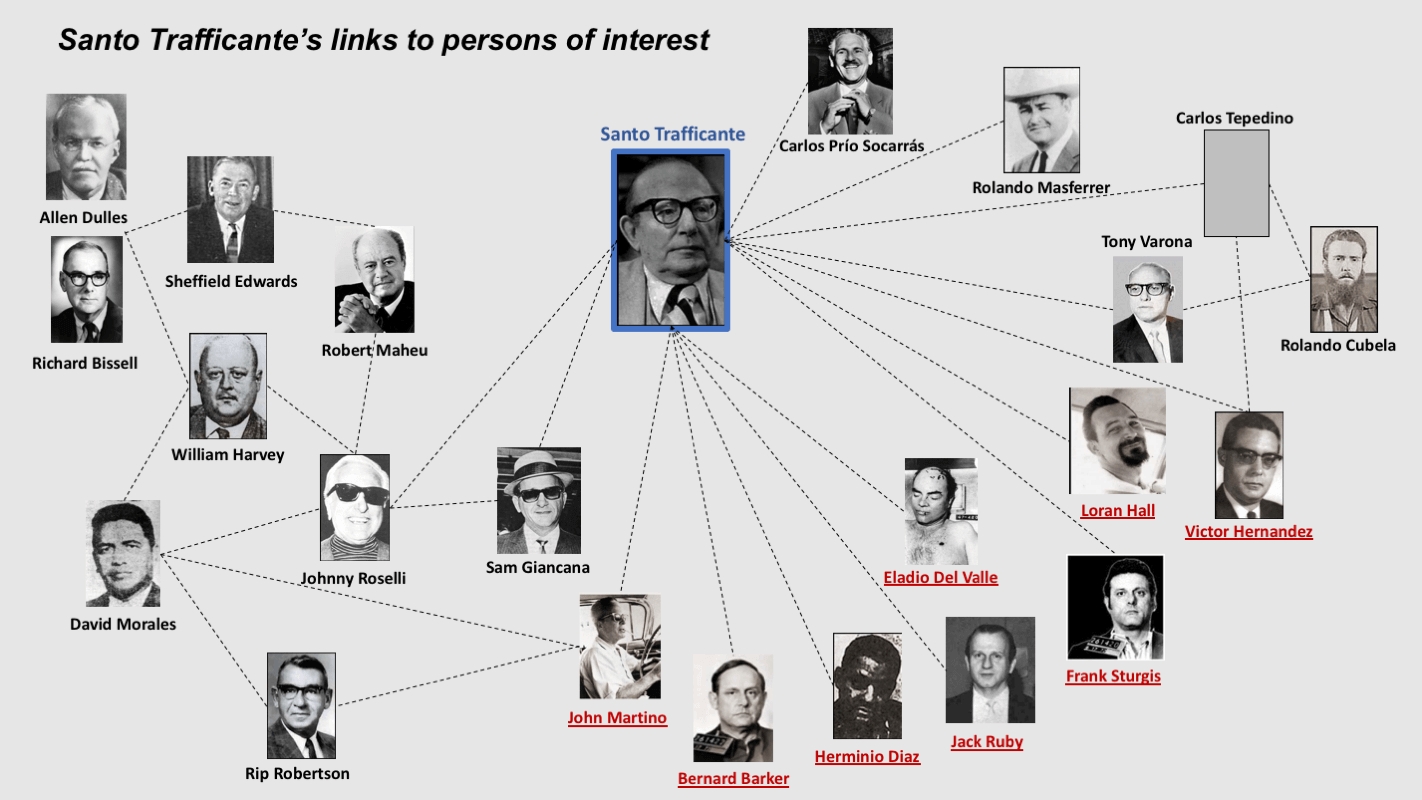

Trafficante’s links

The unholy marriage of the CIA and the Mafia with the objective of removing Castro was initiated by Allen Dulles and Richard Bissell. They had Sheffield Edwards go through Robert Maheu (a CIA cut-out asset), to organize a partnership with mobsters Giancana and Trafficante using Johnny Roselli as the liaison. The CIA gave itself plausible deniability and the Mafia could hope to regain its Cuban empire and a have the ultimate get-out-of-jail-free card in their back pockets.

William Harvey, author of executive action M.O. ZR/RIFLE, eventually oversaw the relationship between himself and Roselli, which involved assassination expert David Morales as Harvey’s special assistant.

Trafficante, who spoke Spanish, was the ideal mobster to organize a Castro hit because of his long established links on the Island. He was also seen as the CIA’s translator for the Cuban exiles. Through Tony Varona and Carlos Tepedino (AMWHIP-1), they tried to get Rolando Cubela (AMLASH) to murder Castro. Trafficante and his friends have very close ties to the Kennedy assassination, to the point where Robert Blakey (head of the HSCA) became convinced the mob was behind it. Blakey now seems to be open to the idea that the network was a lot larger.

Victor Hernandez connects to Trafficante through his participation in the attempts to recruit Cubela, a potential hitman who had access to Castro. He wound up joining Carlos Bringuier in a Canal Street scuffle with Oswald that the arresting officer felt was for show. This was a key sheep-dipping moment of the eventual patsy. Loran Hall met Trafficante when the two were in jail in Cuba. He ran into him a couple of times in 1963. When the Warren Commission wanted the Sylvia Odio story to go away, Hall helped in the pointless tale that he in fact was one of the people who had met her.

Rolando Masferrer had links with Alpha 66, Trafficante and Hoffa. According to William Bishop, Hoffa gave Masferrer $50,000 to kill JFK. Frank Sturgis connects with so many of the people of interest in the JFK assassination that it would require a book to cover it all. He likely received Mafia financing for his anti-Castro operations. He is alleged to have links with Trafficante. So does Bernard Barker, who some think may have been impersonating a Secret Service agent behind the grassy knoll.

Fabian Escalante received intelligence (in part from prisoner Tony Cuesta) that Herminio Diaz and Eladio del Valle were part of the hit team and were in Dallas shortly before the assassination. Robert Blakey had the Diaz story corroborated by another Cuban exile. Diaz was Trafficante’s bodyguard and a hitman. Del Valle worked for Trafficante in the U.S. and was an associate of his in Cuba. It is important to note that Diaz’ background fits well with what is alleged, however some doubt the hearsay used to accuse him.

John Martino showed pre-knowledge of the assassination and admitted a support role as a courier. He also helped in propaganda efforts to link Castro with Oswald. He worked in one of Trafficante’s Cuban casinos.

As we have seen in an earlier section, Jack Ruby’s links to Trafficante are many. He is known to have spoken often with underworld personalities very closely linked to Trafficante, Marcello and the Chicago mob during the days leading up to the assassination. These include McWillie, James Henry Dolan and Dallas’ number two mobster Joe Campisi. We all know what he did two days after the coup. His seeming nonchalance in implicating others may have led to his demise while in jail.

The following excerpts from the HSCA report should leave no doubt in the historians’ minds about the significance of just who Ruby’s friends were, what he was up to, and just how badly the Warren Commission misled the American people by describing him as another unstable loner:

… He [Ruby] had a significant number of associations and direct and indirect contacts with underworld figures, a number of whom were connected to the most powerful La Cosa Nostra leaders.

… Ruby had been personally acquainted with two professional killers for the organized crime syndicate in Chicago, David Yaras and Lenny Patrick. The committee established that Ruby, Yaras and Patrick were in fact acquainted during Ruby’s years in Chicago.

… The committee also deemed it likely that Ruby at least met various organized crime figures in Cuba, possibly including some who had been detained by the Cuban government.

… The committee developed circumstantial evidence that makes a meeting between Ruby and Trafficante a distinct possibility …

… The committee concluded that Ruby was also probably in telephonic contact with Mafia executioner Lenny Patrick sometime during the summer of 1963.

… The Assassinations Committee established that Jack Ruby was a friend and business associate of Joseph Civello, Carlos Marcello’s deputy in Dallas.

… Joe Campisi was Ruby’s first visitor after his imprisonment for murdering the President’s alleged assassin. (Incredibly, the Dallas Police did not record the ten-minute conversation between Oswald’s murderer and a man known to be a close associate of Carlos Marcello’s deputy inDallas.)

… The committee had little choice but to regard the Ruby-Campisi relationship and the Campisi-Marcello relationship as yet another set of associations strengthening the committee’s growing suspicion of the Marcello crime family’s involvement in a conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy or execute the President’s alleged assassin or both.

…As for Jack Ruby’s connections with the Marcello organization in New Orleans, the committee was to confirm certain connections the FBI had been aware of at the time of the assassination but had never forcefully brought to the attention of the Warren Commission.

Jack Ruby’s connections to the mob and his actions before, during and after the assassination were obviously a chokepoint for HSCA investigators. If we analyze Trafficante’s points of contact with very suspicious figures, one can easily argue that we have another.

All these relationships should be enough to suggest that Trafficante played a role in the hit, at the very least in the recruitment of Ruby to eliminate Oswald. Over and above being tightly connected with key leaders of the Cuban exile community, he has at least nine (seven definite) links with people who became actors in the Kennedy assassination and/or Oswald’s universe (five definite and four plausible). Any serious investigator cannot file this away as coincidental or innocuous.

David Phillips’ links to Oswald

For a historian, pushing data collection further in this area and synthesizing the data would lead them to a new hypothesis: They would concur with Blakey that the mob was involved in the assassination.

This would lead to a completely new area of investigation (that Blakey sadly dismissed) regarding who was complicit with the mob, which would invariably lead to data collection around CIA mob contacts such as William Harvey and David Morales who link up with our next subject. David Phillips’ overlap with the world of Oswald left some investigators from the Church and HSCA Committees with the feeling that they were within striking distance of identifying him as one of the plotters. That is when George Joannides and George Bush came in and saved the day.

For exhibit 2, we can lazily accept that the entwinement of Phillips’ world with Oswald’s was mere happenstance, or conclude logically that it was by design:

If Oswald was in fact a lone malcontent who somehow drifted by chance into the Texas School Book Depository, how can one even begin to explain so many ties with a CIA officer who just happened to be in charge of the Cuba desk in Mexico City, running the CIA’s anti-Fair Play for Cuba Committee campaign, and one of the agency’s premier propaganda experts? The perfect person to sheep-dip Oswald and to apply ZR/RIFLE strategies of blaming a coup on an opponent, ties into over 20 different events that were used to frame Oswald, blame Castro or hide the truth. He also connects well with up to six other patsy candidates who, like Oswald, all had links with the FPCC and made strange travels to Mexico City. It is no wonder the HSCA and Church Committee investigators found him to be suspicious and lying constantly, even while under oath.

He made no fewer than four quasi-confessions, and his close colleague E. Howard Hunt confirmed his involvement in the crime.

David Phillips’ name does not appear anywhere in the Warren Commission report. Nor in the 26 accompanying volumes. Which is especially startling in light of the fact that he was running the Agency’s anti-FPCC crusade.

Conclusion

JFK’s assassination has been partially solved. The arguments that can satisfy the skeptics are not yet fully streamlined and the willingness of the fourth estate and historians to finally shed light on this historical hot potato is still weak.

Blue-collar and violent crimes perpetuated by individuals get the lion’s share of the publicity and serve to divert attention away from what is really holding America back. Behind the Wall Street meltdown, there were scores of white-collar criminals who almost caused a full-fledged depression. How many went to jail? Who were they? It is pure naiveté to believe that such crimes will get the attention of politicians, yet the limited studies on the matter indicate that they cost society over ten times more than blue-collar crime.

State-crimes are almost never solved, let alone investigated. Politicians, media and the power elite fear being dragged into the chaos that would be caused by a collapse of public trust and avoid these issues like the plague. However, every now and then, a Church Committee does come along and exposes dirty secrets that, instead of hurting the country, will help straighten the course. The catalyst often comes from the youth who were behind the downfall of Big Tobacco and are now taking on the NRA.

This article helps dispel the notion that the Cuban exiles, Mafia and CIA partnership was too complicated to have taken place. There is still explaining to do on how the Secret Service and Dallas Police Department were brought in to play their roles, but researchers like Vince Palamara have already revealed a lot in these areas. At least four of the people Oswald crossed paths with in the last months of his life had cryptonyms (Rodriguez, Hernandez, Bartes and Veciana). If the alleged sightings of him with other Cuban exiles are to be believed and other cryptonyms were to be decoded, that number would more than triple. Still other crypto-coded figures, who may not have met him, played a role in framing him. Still others are persons of interest in the assassination itself. By really exploring Oswald’s universe, we can get a glimpse of who some of the first line players and their bosses were. It is world of spooks, Mafiosi, Cuban exiles and shady businessmen who were part of, or hovered around, the “Cuban-American Mechanism”.

If we were to push this exercise even further and explore the universes of Phillips, Morales and Harvey, we would fall into the world of Allen Dulles, a world brilliantly looked into by David Talbot in The Devil’s Chessboard and also by Fletcher Prouty. Understanding Dulles’ CIA and Sullivan & Cromwell’s links to the power brokers of his era would probably go a long way in explaining how the plot was called.

It is this author’s opinion that today’s power elite are not far away from having the conditions needed to let this skeleton out of the closet. Their cutoff is time: most of the criminals have already passed away. Another cutoff may be Allen Dulles himself: he is long dead and he was not a formal part of the CIA when the crime took place. But as Talbot showed, the trails to him are still quite palpable.

He may end up being the one who takes the most heat. And deservedly so.

Appendix: Cuban exile groups judged to be of average importance in CIA handbook

Asociacion de Amigos Aureliano AAA — Association of Friends of Aureliano

Asociacion de Amigos de Aureliano – Independiente AAA-I — Association of Friends of Aureliano – Independent

Accion Cubana AC — Cuban Action