Tag: CUBA

-

Jim DiEugenio’s 25-part series on Destiny Betrayed, with Dave Emory

For three months, beginning in November of 2018, Jim DiEugenio did one-hour-long interviews on Dave Emory’s syndicated radio show For the Record. Emory has been broadcasting for 40 years. These 25 programs constitute the longest continuous interview series he has ever done. The subject was a sustained inquiry into DiEugenio’s second edition of Destiny Betrayed. Emory was very impressed by the author’s use of the declassified record excavated by the Assassination Records Review Board and how it altered the database of Jim Garrison’s New Orleans inquiry into the assassination of President Kennedy. This series is also the longest set of interviews DiEugenio has ever done about the book. Emory read the book and took extensive notes, which made for an intelligent and informed discussion of what the present record is on the Garrison inquiry.

-

Truthdig, Major Danny Sjursen and JFK

On April 6, 2019 Truthdig joined the likes of Paul Street and Counterpunch in its disdain for scholarship on the subject of the career and presidency of John F. Kennedy. To say the least, that is not good company to keep in this regard. (see, for instance, Alec Cockburn Lives: Matt Stevenson, JFK and CounterPunch, and Paul Street Meets Jane Hamsher at Arlington) What makes it even worse is that the writer of this particular article, Major Danny Sjursen, was a teacher at West Point in American History. In that regard, his article is about as searching and definitive as something from an MSM darling like Robert Dallek. The problem is, Truthdig is not supposed to be part of the MSM.

On April 6, 2019 Truthdig joined the likes of Paul Street and Counterpunch in its disdain for scholarship on the subject of the career and presidency of John F. Kennedy. To say the least, that is not good company to keep in this regard. (see, for instance, Alec Cockburn Lives: Matt Stevenson, JFK and CounterPunch, and Paul Street Meets Jane Hamsher at Arlington) What makes it even worse is that the writer of this particular article, Major Danny Sjursen, was a teacher at West Point in American History. In that regard, his article is about as searching and definitive as something from an MSM darling like Robert Dallek. The problem is, Truthdig is not supposed to be part of the MSM.Sjursen’s article is part of a multi-part series about American History. The title of this installment is “JFK’s Cold War Chains”. So right off the bat, Sjursen is somehow going to convey to the reader that President Kennedy was no different than say Dwight Eisenhower, Harry Truman, or Richard Nixon or Lyndon Johnson in his foreign policy vision.

Almost immediately Sjursen hits the note that the MSM usually does: Kennedy was really all flash and charisma and achieved very little of substance in his relatively brief presidency. And the author says this is true about both his foreign and domestic policy. Like many others, he states that Kennedy hedged on civil rights. I don’t see how beginning a program the night of one’s inauguration counts as hedging.

On the evening of his inauguration, Kennedy called Secretary of the Treasury Douglas Dillon. He was upset because during that day’s parade of the Coast Guard, he did not see any black faces. He wanted to know why. Were there no African American cadets at the Coast Guard academy? If not, why not? (Irving Bernstein, Promises Kept, p. 52) Two days later, the Coast Guard began an all-out effort to seek out and sign up African American students. A year later they admitted a black student. By 1963 they made it a point to interview 561 African American candidates. (Harry Golden, Mr. Kennedy and the Negroes, p. 114)

This was just the start. At his first cabinet meeting Kennedy brought this incident up and said he wanted figures from each department on the racial minorities they had in their employ and where they ranked on the pay scale. When he got the results, he was not pleased. He wanted everyone to make a conscious effort to remedy the situation and he also requested regular reports on the matter. Kennedy also assigned a civil rights officer to manage the hiring program and to hear complaints for each department. He then requested that the Civil Service Commission begin a recruiting program that would target historically black colleges and universities for candidates. (Carl Brauer, John F. Kennedy and the Second Reconstruction, pp. 72, 84) Thus began the program we now call affirmative action. Kennedy issued two executive orders on that subject. The first one was Executive Order 10925 in March of 1961, three months after his inauguration.

Kennedy’s civil rights program extended into the field of federal contracting in a way that was much more systematic and complete than any president since Franklin Roosevelt. (Golden, p. 61) In fact, it went so far as to have an impact on admissions of African American students to private colleges in the South. As Melissa Kean noted in her book on the subject, Kennedy tied federal research grants and contracts to admissions policies of private southern universities. This forced open the doors of large universities like Duke and Tulane to African American students. (Kean, Desegregating Private Higher Education in the South, p. 237)

I should not have to inform anyone, certainly not Major Sjursen, about how this all ended up at the University of Mississippi and then the University of Alabama. The president had to call in federal marshals and the military in order to escort African American students past the governors of each state. In both cases, the administration had helped to attain court orders that, respectively Governors Ross Barnett and George Wallace, had resisted. That resistance necessitated the massing of federal power in order to gain the entry of African American students to those public universities.

After the last confrontation, where Kennedy faced off against Governor Wallace, he went on national television to make the most eloquent and powerful public address on civil rights since Abraham Lincoln. Anyone can watch that speech, since it is on YouTube. By this time, the summer of 1963, Kennedy had already submitted a civil rights bill to Congress. He had not done so previously since he knew it would be filibustered, as all other prior bills on the subject had been. Kennedy’s bill took one year to pass. And he had to mount an unprecedented month-long personal lobbying campaign to launch it. (Clay Risen, The Bill of the Century, p. 63) When one looks at Kennedy’s level of achievement in just this one domestic field and locates and lists his accomplishments, it is clear that he did more for civil rights in three years than FDR, Truman and Eisenhower did in nearly three decades (see chart at end).

The reason for this is that the Kennedy administration was the first to state that it would enforce the Brown vs. Board decision of 1954. The Eisenhower administration resisted enacting every recommendation sent to it by the senate’s 1957 Civil Rights Commission. (Harris Wofford, Of Kennedys and Kings, p. 21) As Michael Beschloss has written, Eisenhower actually tried to persuade Earl Warren not to vote in favor of the plaintiffs in that case.

Kennedy endorsed that decision when he was a senator. In fact, he did so twice in public. The first time was in New York City in 1956. (New York Times, 2/8/56, p. 1) The second time he did so was in 1957, in of all places, Jackson, Mississippi. (Golden, p. 95) Attorney General Robert Kennedy then went to the University of Georgia Law Day in 1961. He spent almost half of his speech addressing the issue: namely that he would enforce Brown vs Board. Again, this speech is easily available online and Sjursen could have linked to it in his article. So it would logically follow that in 1961, the Kennedy administration indicted the Secretary of Education in Louisiana for disobeying court orders to integrate public schools. (Jack Bass, Unlikely Heroes, p. 135)

Once one properly lists and credits this information, its easy to see that the Kennedy administration was intent on ripping down Jim Crow in the South even if it meant losing what had been a previous Democratic Party political bastion. (Golden, p. 98) Kennedy’s approval rating in the South had plummeted from 60 to 33% by the summer of 1963. He was losing votes for his other programs because of his stand on civil rights. But as he told Luther Hodges, “There comes a time when a man has to take a stand….” (Brauer, pp. 247, 263-64)

In addition to that, Kennedy signed legislation that allowed federal employees to form unions. (Executive Order 10988 , January 17, 1962) This was quite important, since it began the entire public employee union sector movement, today one of the strongest areas of much diminished labor power. In March of that same year, Kennedy signed the Manpower Development and Training Act aimed at alleviating African American unemployment. (Bernstein, pp. 186-87)

On April 11, 1962 Kennedy called a press conference and made perhaps the most violent rhetorical attack against a big business monopoly since Roosevelt. Thus began his famous 72-hour war against the steel companies. Kennedy had brokered a deal between the unions and the large companies to head off a strike and an inflationary spiral in the economy. The steel companies broke the deal. Robert Kennedy followed the speech by opening a grand jury probe into monopoly practices of collusion and price fixing. He then sent the FBI to make evening visits to serve subpoenas on steel executives. No less than John M. Blair called this episode “the most dramatic confrontation in history between a President and corporate management.” (Donald Gibson, Battling Wall Street, p. 9) When it was over, the steel companies rescinded their price increases.

Three months later, Kennedy tried to pass a Medicare bill. It was defeated in Congress. But on the day of his assassination, he was working with Congressman Wilbur Mills to bring the bill back for another vote. (Bernstein, pp. 256-58) In October of 1963, Kennedy’s federal aid to education bill was passed. This was the first such bill of its kind. (Bernstein, pp. 225-230)

At the time of his assassination, due to the influence of Michael Harrington’s The Other America, Kennedy was working on an overall plan to attack urban poverty. As careful scholars have pointed out, the War on Poverty was not originated by Lyndon Johnson. Kennedy had been working on such a program with the chairman of his Council on Economic Advisors, Walter Heller, for months before his murder. (Edward Schmitt, The President of the Other America, pp. 92, 96) As more than one commentator has written, what Johnson did with the Kennedy brothers’ draft of that plan was quite questionable. (Wofford, p. 286 ff.) To cite just one example, LBJ retired the man—David Hackett—who the Kennedys had placed in charge of the program.

I could go on with the domestic side, pointing to Kennedy’s almost immediate raising of the minimum wage, his concern for lengthening unemployment benefits, his establishment of a Women’s Bureau, the comments by labor leaders that they just about “lived in the White House”, etc., etc. In the face of all this, for Sjursen to write that Kennedy’s administration contained “so few tangible accomplishments” or did nothing for unemployed African Americans, this simply will not stand up to a full review of the record.

Sjursen’s discussion of Kennedy’s foreign policy is equally obtuse and problematic. He begins by saying that Kennedy fulfilled “his dream of being an ardent Cold Warrior.” He then writes that “Kennedy was little different than—and was perhaps more hawkish than—his predecessors and successors.”

In the light of modern scholarship, again, this will simply not stand scrutiny. Authors like Robert Rakove, Philip Muehlenbeck, Greg Poulgrain, and Richard Mahoney—all of whom Sjursen ignores—have dug into the archival record on this specific subject. They have shown, with specific examples and reams of data, that Kennedy forged his foreign policy in conscious opposition to Secretaries of State Dean Acheson, a Democrat and Republican John Foster Dulles.

This confrontation was not muted. It was direct. And it began in 1951, even before Kennedy got to the Senate, let alone the White House. His visit to Saigon in that year and his meeting with a previous acquaintance, State Department official Edmund Gullion, about the French effort to recolonize Vietnam, was the genesis for a six-year search to find a new formula for American foreign policy in the Third World. Congressman Kennedy was quite troubled with Gullion’s prediction that France had no real chance of winning its war against Ho Chi Minh and General Vo Nguyen Giap. Upon his return to Massachusetts, he began to make speeches and write letters to his constituents about the problems with America’s State Department in the Third World. In 1954, Senator Kennedy warned that

… no amount of American military assistance in Indochina can conquer an enemy which is everywhere and at the same time nowhere, an enemy of the people which has the sympathy and covert support of the people.

In 1956, he made a speech for Adlai Stevenson in which he criticized both the Democratic and Republican parties for their failures to break out of Cold War orthodoxies in their thinking about nationalism in the Third World. He stated that this revolt in the Third World and America’s failure to understand it, “has reaped a bitter harvest today—and it is by rights and by necessity a major foreign policy campaign issue that has nothing to do with anti-Communism.” (Richard Mahoney, JFK: Ordeal in Africa, pp. 15-18) Stevenson’s office wired him a message asking him not to make any more foreign policy statements associated with his campaign.

My question then to Mr. Sjursen is: If you are too extreme for the liberal standard bearer of your party, how can you be “little different than” or even “more hawkish” than he is?

This was all in preparation for his career-defining speech of 1957. On July 2 of that year, Kennedy spoke from the floor of the Senate and made perhaps the most blistering attack on the Foster Dulles/Dwight Eisenhower Cold War shibboleths toward the Third World that any American politician had made in that decade. This was Kennedy’s all-out attack on the administration’s policy toward the horrible colonial war going on in Algeria at the time. He compared this mistake of quiet support for the spectacle of terror that this conflict had produced with the American support for the doomed French campaign to save its colonial empire in Indochina three years previously. He assaulted the White House for not being a true friend of its old ally. A true friend would have done everything to escort France to the negotiating table rather than continue a war it was not going to win and which was at the same time tearing apart the French home front. In light of those realities, he concluded by saying America’s goals should be to liberate Africa and to save France. (John F. Kennedy, The Strategy of Peace, pp. 66-80)

Again, this speech was assailed not just by the White House, but also by people in his own party like Stevenson and Harry Truman’s Secretary of State Dean Acheson. (Mahoney, p. 20) Of the over 130 newspaper editorials it provoked, about 2/3 were negative. (p. 21) A man who was “little different” than his peers would not have caused such a torrent of reaction to a foreign policy speech. To most objective observers, this evidence would indicate that Kennedy was clearly bucking the conventional wisdom as to what America should be doing in the Third World with regards to the issues of nationalism, colonialism and anti-communism. As biographer John T. Shaw later wrote about these speeches, what Kennedy did was to formulate an alternative foreign policy view toward the Cold War for the Democratic party. And this was his most significant achievement in the Senate. (John T. Shaw, JFK in the Senate, p. 110) But for Mr. Sjursen and Truthdig, this is all the dark side of the moon.

By not noting any of this, Sjursen does not then have to follow through on how Kennedy carried these policies into his presidency. A prime example would be in the Congo, where Kennedy pretty much reversed policy from what Eisenhower was doing there in just a matter of weeks. The man who Kennedy was going to back in that struggle, Patrice Lumumba, was hunted down and killed by firing squad three days before the new president was inaugurated. Eisenhower and Allen Dulles had issued an assassination order for Lumumba in the late summer of 1960. (John Newman, Countdown to Darkness, p. 236) After he was killed, the CIA kept the news of his death from President Kennedy until nearly one month after Lumumba was killed. But on February 2, not knowing he was dead, Kennedy had already revised the Eisenhower policy in Congo to favor Lumumba. (Mahoney, p. 65) In fact, this was the first foreign policy revision the new president had made. Some have even argued that the plotting against Lumumba was sped up to make sure he was killed before Kennedy was in the White House. (John Morton Blum, Years of Discord, p. 23)

How does all of the above fit into the paradigm that Sjursen draws in which the Cold War heightened under Kennedy and his vision had no room for nuances of freedom and liberty? Does anyone think that Eisenhower would have reacted to Lumumba’s death with the pained expression of grief that JFK did when he was alerted to that fact? Eisenhower was the president who ordered his assassination. (For an overview of this epochal conflict and how it undermines Sjursen and Truthdig, see Dodd and Dulles vs Kennedy in Africa)

One of the most bizarre statements in the long essay is that Kennedy was loved by and enamored of the military. The evidence against this is so abundant that it is hard to see how the author can really believe it. But by the end of the 1962 Missile Crisis, the Joint Chiefs of Staff were openly derisive of JFK. They told him to his face that his decision to blockade Cuba instead of attacking the island over the missile installation was the equivalent of Neville Chamberlain appeasing Hitler at Munich. (James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed, Second Edition, p. 57) They were also upset when he rejected the false flag scenarios outlined in their Operation Northwoods proposals, e.g., blowing up an American ship in Cuban waters. These were designed to create a pretext for an invasion of the island. He also writes that Kennedy deliberately chose the space race since it was a popular way to one-up the Russians. This ignores the fact that Kennedy thought it was too expensive and wanted a joint expedition to the moon with the Soviets. According to the book One Hell of a Gamble by Tim Naftali and Aleksandr Fursenko, Kennedy actually attempted to do this earlier, in 1961, but was turned down by Nikita Khrushchev.

Sjursen blames the failure of the Bay of Pigs on Kennedy. First of all, the Bay of Pigs invasion was not Kennedy’s idea. And anyone who studies that operation should know this. It was created by Eisenhower and Allen Dulles. Dulles and CIA Director of Plans Dick Bissell then pushed it on Kennedy. They did everything they could to get Kennedy to approve it, including lying to him about its chances of success. The important thing to remember about this disaster is that Kennedy did not approve direct American military intervention once he saw it failing. This had been the secret agenda of both Dulles and Bissell, who knew it would fail. (DiEugenio, p. 47)

Kennedy later suspected such was the case and he fired Dulles, Bissell and Charles Cabell, the CIA Deputy Director. There is no doubt that if Nixon had won the election of 1960, he would have sent in the Navy and Marines to bail out the operation. Because this is what he told JFK he would have done. (Arthur Schlesinger, A Thousand Days, p. 288) And today, Cuba would be a territory of the USA, like Puerto Rico. Again, so much for there being no difference between what came before Kennedy and what came after.

Sjursen then tries to connect the Bay of Pigs directly to the Missile Crisis. As if one was the consequence of the other. Graham Allison, the foremost scholar on the Missile Crisis, disagreed. And so did John Kennedy. After the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy had a meeting with Khrushchev in Vienna. He found the Russian leader obsessed with the status of Berlin. So much so that during the Berlin Crisis in the fall of 1961, the Soviets decided to build a wall to separate East from West Berlin. In the fine volume The Kennedy Tapes, still the best book on the Missile Crisis, it is revealed that Berlin is what Kennedy believed the Russian deployment was really about. (See Probe Magazine, Vol. 5, No 4, pp. 17-18) That whole crisis was not caused by Kennedy. It was provoked by Nikita Khrushchev. And again, Kennedy did not take the option extended by many of his advisors, that is, using an air attack or an invasion to take out the missiles. He insisted on the least violent option he could take. One person died during those thirteen days. He was an American pilot. Kennedy did not take retaliatory action.

I should not even have to add that Sjursen leaves out the crucial aftermath of the Missile Crisis: that Kennedy developed a rapprochement strategy with both Fidel Castro and Nikita Khrushchev. Both of these are well described by Jim Douglass in his important book JFK and the Unspeakable. (see pp. 74-90 for the Castro back-channel; pp. 340-51 for the Kennedy/Khrushchev détente facilitated by Norman Cousins) The rapprochement attempt with Russia culminated with Kennedy’s famous Peace Speech at American University in the summer of 1963. Which, like Kennedy’s Algeria speech, Sjursen does not mention.

Predictably, Sjursen ends his essay with Kennedy and Vietnam. He actually writes that Kennedy’s policies there led the US “inexorably deeper into its greatest military fiasco and defeat.” What can one say in the face of such a lack of respect for the declassified record?—except that all of that record now proves that Kennedy was getting out of Vietnam at the time of his murder. (Probe Magazine, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 18-21) That Johnson knew this at the time, and he consciously altered that withdrawal policy, and then tried to cover up the fact that he had. And we have that in LBJ’s own words today. (Virtual JFK, by James Blight, pp. 306-10) There was not one combat troop in Vietnam when Kennedy was inaugurated. There was not one there on the day he was killed. By 1967, there were over 500,000 combat troops in theater.

Many informed observers complain about the censorship and distortion so prevalent on Fox News. But I would argue that when it comes to this subject, the journals on the Left do pretty much the same thing, ending up with the same result: the misleading of its readership. I would also argue the very process—from the editor on down to the choice of author and sources used—skews the facts and sources as rigorously and as stringently as Fox. On two occasions, I have asked Counterpunch to print my reply to anti-Kennedy articles they have written. I sent an e-mail to Truthdig to do the same with this essay. As with Counterpunch, I got no reply. This would suggest that there is a Wizard of Oz apparatus at work, one which does not wish to see the curtain drawn. Such a contingency reduces this kind of writing to little more than playing to the crowd. With Fox, that crowd is on the right. With Counterpunch and Truthdig, it is on the left. In both cases, the motive is political. That is no way to dig for truth.

-

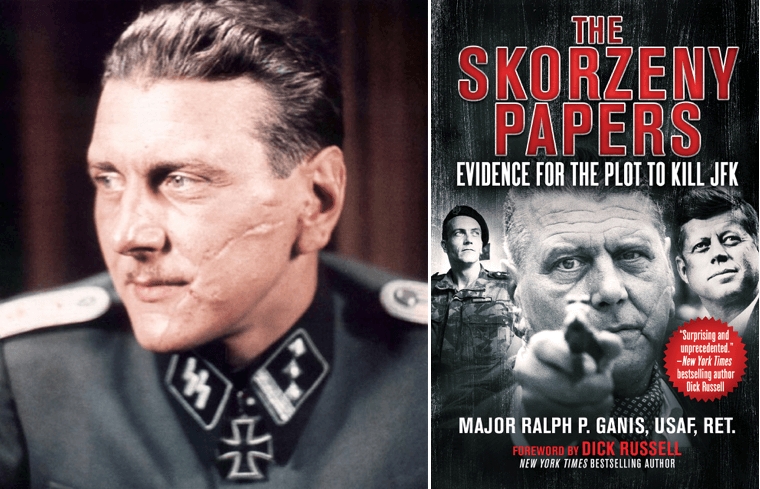

Paul Blake Smith, JFK and the Willard Hotel Plot

When I was asked to do a review of this book, I was quite hesitant. I do not like to comment on other people’s work, especially when a lot of effort has been put into it. The reason I accepted this time is that it was related to research I have been doing over the last two years on prior plots to assassinate JFK and the framing of other potential patsies.

Some who have read my articles wondered why I had not included an attempt in Washington in my analysis. Paul Blake Smith’s book subtitles itself as The Explosive Theory of Oswald in D.C. I felt this could perhaps add yet another plot to the long list of those already exposed. However, Blake Smith’s pitch that he would present compelling evidence that Oswald was in Washington as part of a squad of shooters taking aim at Kennedy from the Willard Hotel is just one of the things he promises to deliver. He states that his book is unique in that it “utilizes the revealing treasury report on Oswald-at-the-Willard”, and many other small clues: “The document is the lynchpin that holds together a solid conspiracy theory and is nearly a Rosetta Stone for deciphering the overall scope of the historic mystery.” The book would also reveal how Mafia chieftain Carlos Marcello was behind this plot and the eventual, successful Dallas assault plan. Extravagant promises, tempered by his admission that we need more facts and that a lot of his evidence is circumstantial.

I had been expecting to read a tightly knit exposé of a Washington cabal. Instead, when the book arrived, I was faced with 433 pages that covered so much ground about not only the alleged plot, but a whole parallel look into the Lincoln assassination, the similarities between the two, and the author’s analysis of who was behind JFK’s assassination—from the orchestrators to the shooters.

In the introduction (p. 5), the author takes precautions not to be labeled a conspiracy theorist: “In other historic dramas, like the RFK or MLK murders in mid-1968, there doesn’t seem to have been any conspiracy at all, just a true lone gunman responsible. I certainly do not see conspiracies behind every bush …”

This is really too bad because the author has blocked himself off from potential comparative case analysis where the conspiracies behind them are perhaps as easy to demonstrate as with the JFK assassination. The MLK assassination was also judged a conspiracy by the HSCA and the RFK assassination was proven one by the autopsy alone. Even the late Vincent Bugliosi was greatly troubled by the RFK investigation. By negating these plausible conspiracies, the author has blocked off a source of information that relates to the JFK assassination—certainly when it comes to analyzing motive, media cover-up and shoddy investigations. Many of the authors Blake Smith lists in his bibliography have just signed a petition to have these cases, along with Malcolm X’s murder, re-opened. Lisa Pease just launched her book about RFK’s assassination, A Lie Too Big to Fail, which has received excellent reviews from no less than the Washington Post. In it, she presents Robert Maheu’s and John Roselli’s links to that case. Sound familiar?

Also on the back cover, the author promotes another of his books, MO-41: The Bombshell Before Roswell. I took the time to do a little web research and found Amazon comments on it: some good and some less so. This comment got my attention:

The narrative flows along, but there are no footnotes; and there is too much hearsay reported, especially from online chat rooms and email, which is not substantiated. More needs to be done, before I’ll buy this book’s premise/theory. The Roosevelt information is another matter altogether. The author asserts that F.D.R. shot himself due to his knowledge of the aliens, etc. of the UFO events previously described in the previous chapters.

I had to put the book down many times and fight off my instincts to pre-judge it because I could see that it quickly staked out positions that were diametrically opposed to where I stand on the case. By the time I was through the first chapter I was dejected and regretted my decision to accept this mandate. However, a promise is a promise, so I read on. The more I read, the less I regretted taking on this endeavor, not because this was by any means a masterpiece. It is not. However, there is useful information which the author deserves credit for underscoring.

After thinking somewhat about how to evaluate his work, I decided to focus on three basic theories that he advances: 1) That there was a plot in the works to terminate JFK in Washington in early October 1963; 2) That Oswald was in Washington leading this mission at around this time; and 3) That Carlos Marcello was the leading figure behind this plot and the eventual assassination in Dallas, “with some insider help”.

So before analyzing the author’s evidence, let’s first get an idea of what some of his key positions are, which I must admit is not easy, as many seem to evolve from chapter to chapter and sometimes from page to page. We will first look at his views on the nature of the conspiracy.

A Mob-led conspiracy

At the beginning of chapter 1, Carlos Marcello’s famous rant is quoted: “Yeah I had that Sonuvabitch killed”, and then the author states shortly after: “This book aims to tell more precisely how Carlos got just what he wanted”.

As for motive, we are given the usual litany of mob frustrations with the Kennedys. They helped get JFK elected and instead of having their guy in the White House, they were double-crossed when Bobby aggressively went after them; Marcello had been exiled to Guatemala by Bobby in 1961, etc.

Therefore, “Carlos was determined to pay back the young president (and his cocky brother) in the most violent and extreme way he could think of: By having John F. Kennedy gunned down right at his precious White House, maybe even from the very same attractive Willard Hotel of 61”. He explains the importance of choosing cold-blooded, scummy killers that were not traceable to the Mafia: “It was just a matter of finding the most greedy, unprincipled persons” (p. 22) Remember this last line when we explain why Blake Smith believes the assassins had Kennedy in their sights from the Willard Hotel but decided not to shoot.

He goes on to state that Carlos got buy-in from a few of the top hoodlums and came to realize he needed to hire a guilty-looking oddball who could not be tied directly to the Marcello “outfit”. By page 31, Blake Smith begins presenting a Mafia/KKK partnership since they also shared a hatred of Kennedy.

On page 33, he makes the following statement: “Thus it seems pretty accepted today that Marcello recruited his oldest Mafia contacts, Giancana and Trafficante, to help him rub out the president.”

The author has taken it upon himself to identify Marcello, Giancana and Trafficante as “the Big Three” of the Mafia in the early sixties. This seems both arbitrary and questionable, as it eliminates men like Meyer Lansky, and all the heavy hitters from the East Coast. In fact, none of these men were members of the governing commission of the Mafia at this time. (HSCA, Volume 9, p. 18) Marcello was not particularly tight with Giancana. He was actually in competition with Trafficante for the drug traffic in the Gulf area. Why propose a hit to someone who will have leverage over you?

The CIA in all this? In 1960, the Big Three:

… accepted CIA cash in exchange for assassinating Castro, but instead they took the money, gave lip service in return but no real effort and then chocked up [sic] another marker to call in for future schemes. A kind of blackmail to expose unless the CIA cooperated on certain future Mafia proposals: Like murdering their own commander in Chief. (p. 37)

Actually, they did not give lip service. As the CIA Inspector General Report shows, there were three different attempts to poison Castro and the last one may have worked had the CIA not screwed it up by putting Tony Varona on ice during the Bay of Pigs landings. (These are described in the CIA Inspector General Report, pp. 31ff, and are termed the Phase 1 plots.) In addition, the mobsters refused to take any payment for their efforts. (p. 16)

Blake Smith then broadens out to say a rotten apple was recruited from within the Secret Service to help in the plot. However, the number grows significantly in a couple of later chapters.

When it comes to describing Lee Harvey Oswald, the author is consistent, direct and does not pull any punches.

Blake Smith takes everything negative ever said about the alleged assassin and kicks it up a notch: “rat-faced fellow from Marcello’s New Orleans”; “Perpetually unemployed Marxist-spouting, ex-Marine defector”; “Had problems getting along with others, the high-strung abusive oddball, was obsessed with the anti-American hero … pro Fidel Castro”; “Lonely Lee”; “Lazy Lee”; “Handed out pro-Marxist sheets making a fool of himself”; “Arrogant L.H. Oswald was of course the same southern-fried, rifle-clutching, wife-beating school drop-out”; “Miscreant Lee in the summer of 63 was so obsessed with Soviet-linked Castro he spoke only Russian at home”; “LHO often padded around “The Big Easy” with his old military training manual … and around house with his .38 caliber pistol … plus his Mannlicher Carcano …”; “a lazy little mouse who wanted to roar”; “Lee really didn’t have the size, education, the guts and strength to accomplish anything positive”; “Puny Lee craved money, recognition, respect”… “Chronic Creep Lee had to get out of Dallas that mid-April to escape the heat from his brazen attempted assassination of retired General Edwin Anderson Walker”; “Lee had himself photographed by his wife posing with a pistol and a rifle and communist literature”; “Anyone who criticized and threaten his beloved Castro was an imperial fascist who deserved to be shot …” The author also shows us some of his prowess in psychiatry by diagnosing Oswald as semi-psychotic: a qualifier he uses throughout the book. This comes in handy, because now he can explain almost anything Oswald does henceforth in his exposé, no matter how illogical.

According to the author, Oswald was brainwashed into killing Kennedy by figures connected to Marcello, by telling him the president wanted Castro dead and the American Mafia out of power for good.

The Warren Commission could not find any motive for Oswald. Blake Smith spells out what it missed: Oswald would “help kill Kennedy to save Castro and expect rewards including legal passage to Cuba as an accepted resident there outside of extradition.”

Blake Smith opines that Oswald did fire twice at Kennedy and then once at Connally, nailing both men in the back (page 324). His third shot hit the curb. He then killed Officer Tippit before Marcello had Ruby rub him out. And there is this peculiar statement: “Lee’s shots were in reality only to get people—especially JFK’s Secret Service Agents—to look the wrong way, a distraction for the knoll gunman’s crucial kill shot.” Never mind that it appears the throat shot from the front preceded the back wound shot.

Lee Harvey Oswald in Washington

Concerning this aspect of the Willard Hotel plot, the author does not waste any time summarizing ten clues in Chapter 1 that “reveal the reality of Lee Oswald in Washington and some aspects of the two planned “Willard Hotel Plots” in Washington.

These include:

- What he calls a formerly buried Willard Hotel Secret Service report.

- The Joseph Milteer tape where the white supremacist can be heard predicting the assassination.

- Richard Case Nagell’s letters warning the FBI of a Washington plot towards the end of September.

- Lee Harvey Oswald’s letters talking about moving to Washington at this time.

- J. Edgar Hoover’s memos stating that Oswald had been in Washington.

- David Ferrie’s rants about killing Kennedy in Washington.

- Statements made by a Cuban exile made in Miami before the assassination.

- Documents retrieved from a pile of burned leaves in Pennsylvania.

- A scorched memo sent to a researcher that “supposedly” was retrieved from James Angleton’s fireplace.

- A Secret Service report on Marina Oswald.

After reading the whole book, my opinion is that there is a good argument to be made that there were many contingency plans in place to kill JFK at locations he visited throughout the last three quarters of 1963 and perhaps even earlier. That Washington was on the list is probable and can be based not only on the author’s (and others) writings, but by the numerous other plots that have been documented. The idea that Oswald was being maneuvered to be a patsy there is plausible. However, Oswald’s pro-Marxist behavior was a matter of sheep-dipping by intelligence and not, as the author writes, an expression of his ideology. Washington was not the original plot to bump off JFK as claimed by the author, as cabals in L.A. and Nashville preceded it. Finally, the proof that Oswald was in fact in Washington in late September and early October 1963, as laid out in this book, is a lot weaker than what the author argues. We will discuss this later, as well as the case made about the Willard Hotel being a place that the shooters actually occupied when they had Kennedy in their sights.

Summary

I don’t think kennedysandking readers need me to find arguments against much of the author’s often debunked and rehashed mob-led conspiracy theory. Many of the arguments the author presents in his “Marcello mastermind” scenario only demonstrate mob involvement as a very junior partner in the conspiracy. As a matter of fact, he could have put more emphasis on Ruby’s probable visit to Trafficante in Cuba, the analysis of his phone calls during the days leading up to the assassination, as well as the fact that one of Ruby’s first visitors while in jail was alleged Dallas mobster Joe Campisi. Other arguments the author presents are on shaky ground. When it comes to the hierarchal structure of the coup, his pecking order needs revising. If he is looking for arguments to do so, I will refer him later to his own sources.

In this day and age, the fact that the author does not even want to entertain the notion that Oswald may not have been a commie nut is faintly ludicrous, and has been ever since the following famous statement was published:

We do know Oswald had intelligence connections. Everywhere you look with him, there are fingerprints of intelligence.

~ Senator Richard Schweiker, The Village Voice, 1975

From 1975 to 1976, Schweiker was a member of the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. According to Blake Smith, Oswald would kill any who would dare threaten Fidel Castro. Yet Oswald spent the latter years of his life in the Marines, with White Russians, and right wing extremists like David Ferrie and Guy Banister, Cuban exiles hostile to Castro, perhaps with Mafiosi who wanted the island back, CIA contacts … the crème de la crème of Castro hostiles. When he was arrested on Canal Street, Oswald asked to meet with FBI agent Warren de Brueys, who was responsible for monitoring the Fair Play for Cuba Committee and Cuban exiles. This may be why Gerald Ford wrote about a Warren Commission meeting presenting information that Oswald was a government informant.

One would also wonder whom from the Mafia, or the Secret Service, would even risk exposing themselves and their roles in a plot by conferring so much responsibility to such a loose cannon. Blake Smith also speculates Oswald is capable of quite the accomplishments for such a loser: sending one or two of his doubles down to Mexico City to set up an alibi, receiving inside information from Secret Service agents in Washington, placing two shots in the back of both JFK and Governor Connally with a terrible weapon …

Schweiker was not alone in having his doubts about Oswald’s Warren Commission persona, and who was really behind the assassination. HSCA Chief Counsel Richard Sprague, attorney Mark Lane, investigator Gaeton Fonzi and New Orleans DA Jim Garrison all expressed similar opinions. These later snowballed into a consensus that we can now read in the recently written Truth and Reconciliation joint statement, signed by many of the researchers Blake Smith refers to. In it, you will not see a whiff of consent around a mob-led conspiracy scenario. You will see that these writers think the mob figures were themselves being led! The first paragraph speaks for itself:

In the four decades since this Congressional finding, a massive amount of evidence compiled by journalists, historians and independent researchers confirms this conclusion. This growing body of evidence strongly indicates that the conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy was organized at high levels of the U.S. power structure, and was implemented by top elements of the U.S. national security apparatus using, among others, figures in the criminal underworld to help carry out the crime and cover-up.

We will return to flaws in the author’s logical construction later. I did find some positive contributions in this work, at least points useful in my own investigative objectives. Here is what I feel are some of the stronger points of the book:

- The author does cover either numerous areas that reminded me of interesting anecdotes or issues I had read a while back but I had forgotten about, and some I had not heard of.

- He presented arguments around the work of some reliable researchers that have convinced me that there could well have been a plot to assassinate Kennedy in Washington that would have framed Oswald. This is of strong interest to me because of my research in the prior plots to assassinate Kennedy.

- Related to this point, the author presents some context on the goings on in D.C. during the period Oswald was scheduled to be there.

- While his attempts to link the KKK to a Mafia-led plot are weak, his writings allowed me to better understand some of the history and structure of American hate groups and the arguments others have put forth about their alleged contribution to the coup.

- Some of the writings around the mob, and I say some, could be interesting to novice readers.

- I, along with a growing number of researchers, concur with his conclusions that Oswald never visited Mexico City. I also applaud his attempt to answer the obvious question that arises because of this: Where was Oswald during these crucial dates? This is an important debate that researchers must have.

- While his writings about Secret Service participation are at times contradictory, he did a smart thing in relying heavily on Vince Palamara in his research, which resulted in two of his best chapters.

Unfortunately, these also included two major negatives. He contaminated them somewhat with some of the worst of the Dark Side of Camelot and other TMZ-style gossip about Kennedy’s private life. And then, for some very weird, unexplained reason, he decided to use the pseudonym Trip-Planner Perry to identify (or hide) one of his leading suspects from the Secret Service. I will speculate later on why I think he chose this very unfortunate writing strategy. Whatever the reason, as a reader I felt very manipulated and frustrated.

I also have written about how the CIA, Mafia and Cuban exile network involved in the assassination had roots going back many decades. I am now interested in how the Secret Service could have logistically worked with this network. Blake Smith does present some good leads to follow up on.

My philosophy about reading in general is that if, at the end of a book, I have learned something new and important, or my view about an issue has evolved, there has been progress. However, the struggle to get there can be often very demoralizing—talk about mixed emotions!

Research and analysis

One of my frustrations with Blake Smith’s book was trying to make sense of the author’s sources. His footnote management is very inconsistent; his exhibits, especially the documents, are poorly identified and made almost impossible to read because of poor reproduction; his sources are difficult to consult and he is often guilty of citation malpractice. Trying to figure out the soundness of his research was quite time-consuming and represented a heavy burden for readers like me who like to evaluate the solidity of the argument or dig to find out more. Throughout the book, I felt the author was playing a game of hide-and-seek with his primary data. I will give a few examples later. If you are going to make a case on circumstantial evidence, you really need to back up your observations with solid, easy to consult references.

Blake Smith’s sources and evidence are often so scrambled, mysterious and sketchy that the real sleuthing related to this work is trying to figure out what they are. All too often, you cannot try to expand your knowledge or verify the authenticity of the evidence. We are left to trust his evaluation of evidence that we cannot explore. On many occasions, he uses the National Enquirer technique of presenting an unidentified source as his basis for making a claim. We are left guessing who-the-heck said what and how credible this informer is.

Here are some examples of the vagueness and lack of sourcing that goes on throughout the book: “On May 15th, 2006, five knowledgeable JFK assassination experts were invited to a special conference …” (we never find out who); exhibit on page 17—FBI report about Marcello that is illegible; page 17, incriminating quotes made by Marcello with no footnotes. Then there is this citation: “He wanted that particular American leader dead in 1963 and hired others to do the job. (source: an FBI report dated the following 3/7/85); “Some legal and media investigations have shown that Marcello had upset the Kennedys; At one point in 1963, researchers have now learned, the devious Mafia plan was becoming so increasingly whispered; According to biographers, for a few weeks spiteful, unstable Oswald ran wages and numbers to gamblers for Murrett; Undoubtedly some Cuban refugees and two key private investigators also worked on Lee Oswald that summer, hammering away at his psyche”—with not one footnote to the entire passage. This is just chapter one. Sometimes, when we are lucky, a whole book is mentioned as the source.

The author could have profited from a reliable editor, one who would have helped with grammar, fact checking and general guidance. I cannot say how many times this has helped me for articles I have written that are less than one tenth the length of his book. Even though the author has an energetic, whimsical style that can be entertaining, the number of punctuation errors, faulty page breaks, misspelled words (assasin, guiilt, coup d’eta to name but a few) and especially name identification errors (Dan Hardway becomes Don Hardaway, Douglas Dillon is at times Douglass, Douglas Horne is also spelled Douglass, Hersh is Hirsh, Harold Weisberg is Weisburg, ZR Rifle is at times just Rifle, and Robert Maheu is misspelled Mahue throughout). This laxness permeates the entire book.

A good editor would have also helped with fact checking and helped avoid blunders, or strongly urged the author to provide the evidence for some of the questionable claims that are often made. The next two sections furnish examples.

The Sylvia Odio incident (page 90):

Blake Smith: (at Odio’s residence on September 25) “Leopoldo and Angelo spoke in Spanish on his (Oswald’s) behalf around sundown, talking about how loco he was in his pro-Castro, anti-Kennedy views.”

Now compare this to what Sylvia Odio said in her testimony to Wesley Liebeler in 1964:

He (Leopoldo) did most of the talking. The other one kept quiet, and the American, we will call him Leon, said just a few little words in Spanish, trying to be cute, but very few, like “Hola,” like that in Spanish.

… I unfastened it after a little while when they told me they were members of JURE, and were trying to let me have them come into the house. When I said no, one of them said, “We are very good friends of your father.” This struck me, because I didn’t think my father could have such kind of friends, unless he knew them from anti-Castro activities. He gave me so many details about where they saw my father and what activities he was in. I mean, they gave me almost incredible details about things that somebody who knows him really would or that somebody informed well knows. And after a little while, after they mentioned my father, they started talking about the American.

He said, “You are working in the underground.” And I said, “No, I am sorry to say I am not working in the underground.” And he said, “We wanted you to meet this American. His name is Leon Oswald.” He repeated it twice. Then my sister Annie by that time was standing near the door. She had come to see what was going on. And they introduced him as an American who was very much interested in the Cuban cause. And let me see, if I recall exactly what they said about him. I don’t recall at the time I was at the door things about him.

I recall a telephone call that I had the next day from the so-called Leopoldo, so I cannot remember the conversation at the door about this American.

I asked these men when they came to the door—I asked if they had been sent by Alentado, became I explained to them that he had already asked me to do the letters and he said no. And I said, “Were you sent by Eugenio,” and he said no. And I said, “Were you sent by Ray,” and he said no. And I said, “Well, is this on your own?”

And he said, “We have just come from New Orleans and we have been trying to get this organized, this movement organized down there, and this is on our own, but we think we could do some kind of work.” This was all talked very fast, not as slow as I am saying it now. You know how fast Cubans talk. And he put the letter back in his pocket when I said no. And then I think I asked something to the American, trying to be nice, “Have you ever been to Cuba?” And he said, “No, I have never been to Cuba.”

And I said, “Are you interested in our movement?” And he said, “Yes.”

This I had not remembered until lately. I had not spoken much to him and I said, “If you will excuse me, I have to leave,” and I repeated, “I am going to write to my father and tell him you have come to visit me.”

And he said, “Is he still in the Isle of Pines?” And I think that was the extent of the conversation. They left, and I saw them through the window leaving in a car. I can’t recall the car. I have been trying to. …

So Blake Smith has the residence meeting all wrong. Let us see how he does with the follow-up call (which he speculates was made from the Willard Hotel) where he states: “That on the evening of the 27th (48 hours later), one of the two Cubans with Oswald called Sylvia Odio and said Oswald wanted to shoot the president.”

Here is Odio’s testimony:

The next day Leopoldo called me. I had gotten home from work, so I imagine it must have been Friday. And they had come on Thursday. I have been trying to establish that. He was trying to get fresh with me that night. He was trying to be too nice, telling me that I was pretty, and he started like that. That is the way he started the conversation. Then he said, “What do you think of the American?” And I said, “I didn’t think anything.”

And he said, “You know our idea is to introduce him to the underground in Cuba, because he is great, he is kind of nuts.” This was more or less—I can’t repeat the exact words, because he was kind of nuts. He told us we don’t have any guts, you Cubans, because President Kennedy should have been assassinated after the Bay of Pigs, and some Cubans should have done that, because he was the one that was holding the freedom of Cuba actually. And I started getting a little upset with the conversation.

And he said, “It is so easy to do it.” He has told us. And he (Leopoldo) used two or three bad words, and I wouldn’t repeat it in Spanish. And he repeated again they were leaving for a trip and they would like very much to see me on their return to Dallas. Then he mentioned something more about Oswald. They called him Leon. He never mentioned the name Oswald.

Mr. LIEBELER. He never mentioned the name of Oswald on the telephone?

Mrs. ODIO. He never mentioned his last name. He always referred to the American or Leon.

Mr. LIEBELER. Did he mention his last name the night before?

Mrs. ODIO. Before they left I asked their names again, and he mentioned their names again.

Mr. LIEBELER. But he did not mention Oswald’s name except as Leon?

Mrs. ODIO. On the telephone conversation, he referred to him as Leon or American. He said he had been a Marine and he was so interested in helping the Cubans, and he was terrific. That is the words he more or less used, in Spanish, that he was terrific. And I don’t remember what else he said, or something that he was coming back or something, and he would see me. It’s been a long time and I don’t remember too well, that is more or less what he said.

And then there is this:

Mr. LIEBELER. Now, a report that we have from Agent Hosty indicates that when you told him about Leopoldo’s telephone call to you the following day, that you told Agent Hosty that Leopoldo told you he was not going to have anything more to do with Leon Oswald since Leon was considered to be loco?

Mrs. ODIO. That’s right. He used two tactics with me, and this I have analyzed. He wanted me to introduce this man. He thought that I had something to do with the underground, with the big operation, and I could get men into Cuba. That is what he thought, which is not true.

When I had no reaction to the American, he thought that he would mention that the man was loco and out of his mind and would be the kind of man that could do anything like getting underground in Cuba, like killing Castro. He repeated several times he was an expert shotman. And he said, “We probably won’t have anything to do with him. He is kind of loco.”

When he mentioned the fact that we should have killed President Kennedy—and this I recall in my conversation he was trying to play it safe. If I liked him, then he would go along with me, but if I didn’t like him, he was kind of retreating to see what my reaction was. It was cleverly done.

In a nutshell, the author in just a few lines of copy, confuses who spoke, what was said during the meeting at the residence, when the follow-up call took place, the claim that Oswald was described as pro-Castro, and while Leopoldo claimed that Oswald said that the Cubans should have killed Kennedy because of the failed Bay of Pigs, he did not say Oswald wanted to shoot the president.

In fact, he is depicted as one who could kill Castro. (WC Vol. 11, p. 377) On the surface, why would three persons seeking (or pretending to seek) to collaborate with an organization that has as its objective the overthrow of Castro, and talk to a person whose father is languishing in a Cuban prison, present Leon as pro-Castro? It is more likely that they were hoping to link the future patsy with JURE an organization favored by the Kennedys for when a potential overthrow took place, but clearly despised by the intelligence apparatus and the other stakeholders.

Throughout the book, the author often distorts evidence, to the point that it appears he has not examined the primary data closely and wants it to point to Oswald being pro-Castro at the Willard Hotel in late September. This tendency is recurrent to the point that the presentation becomes biased and exaggerated.

Jack Ruby and the Mob

On page 376, he makes the claim that Ruby’s motivation to kill Oswald (in part) was his own impending death: “Oswald’s stalker—murderer had been diagnosed with cancer before Kennedy came to Dallas”. His source: talk show host Morton Downey Jr. (1932-2001), who claimed to have interviewed Dr. Alton Ochsner, who would have diagnosed Ruby with cancer in August 1963. Consequently, he knew his time on earth was limited. Never mind that Ruby was based in Dallas and Ochsner in New Orleans, or that there is no corroboration in the literature for this information. Need I also point out that Downey is known for having pioneered Tabloid TV?

In addition, a solid editor would have suggested that he leave out many of his stories that were based on hearsay, outdated evidence and are often irrelevant. I believe that his focus should have been a 200-page analysis of the Washington plot instead of 420 pages on every anecdote there is about the assassination, no matter how wild.

In reading his bibliography, I began to understand why his writings are skewed towards the discredited Mafia-did-it theory. It contains a long list of some 60 books. Among the authors referred to, you will find Waldron, Stone, Chuck Giancana, Shenon, Davis, Hersh, Janney, Aynesworth and Bugliosi. Having read some of the work he includes such, as JFK and the Unspeakable, The Devil’s Chessboard and Survivor’s Guilt, I could not understand his conclusions about the assassination motive or logistics. If he did read them, he seems to have very little regard for the evidence they put forth, since it is at odds with his theories of the crime. Books that seemed to have made a strong impression on him include Double Cross, some of Robert Morrow’s work and Ultimate Sacrifice, since these are among the most referenced. The Robert Blakey (HSCA) quotations he uses are the ones that most support his theory, certainly not the ones Blakey made after coming to terms with the fact that the CIA had duped him by placing obfuscator George Joannides as CIA liaison during the HSCA investigation. This probably goes a long way in explaining his “the Mafia killed Kennedy” view of things.

That bibliography is also notable for what it does not include: None of the work by Newman, Prouty, Simpich, Hancock, DiEugenio, Mellen, Davy, Armstrong, Fonzi, McBride, Ratcliffe, or Lane is listed! How most of these highly respected researchers are not in one’s top sources is difficult to fathom. It explains, in my opinion, why this author’s analysis is mired in the past.

The author’s key theories under the microscope: A Marcello-led Plot

On page 23, the author relates this old tale to us: “You must get a nut to do it.” Marcello allegedly told an FBI informant, who reported those words back to the Bureau and eventually to the press. On page 25, he quotes Marcello as saying he wanted it done so that it could not easily be traced back to him. “If you cut off the tail of a dog, he lives. But if you cut off his head he dies,” Marcello famously explained to his trusted visitor.

For some reason, as he often does, the author presents no footnotes, does not tell us who the informant was and accepts this story at face value. I wondered why a Mafioso would incriminate himself so pointlessly.

According to a 1993 Washington Post article, the informant alluded to here was Las Vegas “entrepreneur” Ed Becker. The following lines prove this: Ed Becker was told by Marcello in September 1962 that he would take care of Robert Kennedy, and that he would recruit some “nut” to kill JFK so it couldn’t be traced to him, according to several accounts. Marcello told Becker that “the dog (President Kennedy) will keep biting you if you only cut off its tail (the attorney general)” but the biting would end if the dog’s head was cut off. Becker’s information that Marcello was going to arrange the murder of JFK was reported to the FBI, though the FBI says it has no records of the Marcello or the Trafficante threats, nor of wiretapped remarks of Trafficante and Marcello in 1975 that only they knew who killed Kennedy.

Becker, who became a key source in Ed Reid’s 1969 book, The Grim Reapers, was shown to be problematic by the HSCA. Here are a few key lines that seriously undermine Becker (follow the link for the whole report on the debunked Marcello threats):

ALLEGED ASSASSINATION THREAT BY MARCELLO

- As part of its investigation, the committee examined a published account of what was alleged to have been a threat made by Carlos Marcello in late 1962 against the life of President Kennedy and his brother, Robert, the Attorney General. The information was first set forth publicly in a book on organized crime published in 1969, “The Grim Reapers,” by Ed Reid. (160) Reid, a former editor of the Las Vegas Sun, was a writer on organized crime and the coauthor, with Ovid Demaris, of “The Green Felt Jungle,” published in 1963.

- In a lengthy chapter on the New Orleans Mafia and Carlos Marcello, Reid wrote of an alleged private meeting between Marcello and two or more men sometime in September 1962. (161) His account was based on interviews he had conducted with a man who alleged he had attended the meeting. (162)

- According to Reid’s informant, the Marcello meeting was held in a farmhouse at Churchill Farms, the 3,000-acre swampland plantation owned by Marcello outside of New Orleans.(163) Reid wrote that Marcello and three other men had gone to the farmhouse in a car driven by Marcello himself. (164) Marcello and the other men gathered inside the farmhouse, had drinks and engaged in casual conversation that included the general subjects of business and sex. (165) After further drinks “brought more familiarity and relaxation, the dialog turned to serious matters, including the pressure law enforcement agencies were bringing to bear on the Mafia brotherhood” as a result of the Kennedy administration. (166)

Reid’s book contained the following account of the discussion:

It was then that Carlos’ voice lost its softness, and his words were bitten off and spit out when mention was made of U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy, who was still on the trail of Marcello. “Livarsi na petra di la scarpa!” Carlos shrilled the cry of revenge: “Take the stone out of my shoe!” “Don’t worry about that little Bobby, son of a bitch,” he shouted. “He’s going to be taken care of!” Ever since Robert Kennedy had arranged for his deportation to Guatemala, Carlos had wanted revenge. But as the subsequent conversation, which was reported to two top Government investigators by one of the participants and later to this author, showed, he knew that to rid himself of Robert Kennedy he would first have to remove the president. Any killer of the Attorney General would be hunted down by his brother; the death of the president would seed the fate of his Attorney General. (167)

No one at the meeting had any doubt about Marcello’s intentions when he abruptly arose from the table. Marcello did not joke about such things. In any case, the matter had gone beyond mere “business”; it had become an affair of honor, a Sicilian vendetta. Moreover, the conversation at Churchill Farms also made clear that Marcello had begun to move. He had, for example, already thought of using a “nut” to do the job. Roughly 1 year later President Kennedy was shot in Dallas—2 months after Attorney General Robert Kennedy had announced to the McClellan committee that he was going to expand his war on organized crime. And it is perhaps significant that privately Robert Kennedy had singled out James Hoffa, Sam Giancana, and Carlos Marcello as being among his chief targets.

FBI investigation of the allegations:

- The memorandum goes on to note that a review of FBI files on Reid’s informant, whose name was Edward Becker, showed he had in fact been interviewed by Bureau agents on November 26, 1969, in connection with the Billie Sol Estes investigation. (185) While “[i]n this interview, Marcello was mentioned * * * in connection with a business proposition * * * no mention was made of Attorney General Kennedy or President Kennedy, or any threat against them.” (186)

- The memorandum said that the agents who read the part of Reid’s manuscript on the meeting told the author that Becker had not informed the Bureau of the alleged Marcello discussion of assassination. (187) In fact, “It is noted Edward Nicholas Becker is a private investigator in Los Angeles who in the past has had a reputation of being unreliable and known to misrepresent facts.” (188)

- Two days later, in an FBI memorandum of May 17, 1967, the Special Agent in Charge (SAC) of the Los Angeles office reported some additional information to Hoover. (194) In the memorandum, the Los Angeles office set forth some alleged information it had learned regarding Becker, who, the memo noted, claimed to have heard “statements supposedly made by Carlos Marcello on September 11, 1963, concerning the pending assassination of President Kennedy.”(195) The FBI memo stated that 1 day after the Bureau first learned of the Reid information, its Los Angeles office received information regarding Edward Becker which was allegedly damaging to his reputation. (196) According to the information, Sidney Korshak had been discussing Becker and:

Korshak inquired as to who Ed Becker was and advised that Becker was trying to shake down some of Korshak’s friends for money by claiming he is the collaborator with Reid and that for money he could keep the names of these people out of the book. (197)

- The memorandum also stated that Sidney Korshak had further stated that “Becker was a no-good shakedown artist,” (198) information which in turn became known to the Bureau. (199)

- Where Becker is referred to as an “informant,” it should be noted that this applies to his relationship to Reid and not to a Federal law enforcement agency.

- On May 31, 1967, according to the same memorandum, a special agent of the Los Angeles office was involved in a visit to Reid’s (208) in a further effort to persuade him of Becker’s alleged untrustworthiness. (209) During this visit, the Bureau’s possible confusion over the time periods involved in the matter was further evidenced in the memorandum, which said that “in November 1969” Becker had “not mentioned the reputed * * * statements allegedly made by Marcello on September 11, 1963.” (211) Again, both Reid and Becker have maintained consistently that they made clear that the meeting was in September 1962, rather than September 1963 (212), and that the specific reference in the Reid book stated “September 1962.” (213) Additionally, the Bureau’s own files on Becker (while not containing any references to assassination) clearly indicated that Becker had been interviewed by agents in November 1962, following a trip through Louisiana that September. (214) Committee investigation of the allegation.

- Becker was referred to in a second FBI report of November 21, 1962, which dealt with an alleged counterfeiting ring and a Dallas lawyer who reportedly had knowledge of it. (222) This report noted that Becker was being used as an “informant” by a private investigator in the investigation (223) and was assisting to the extent that he began receiving expense money. (234) The Los Angeles FBI office noted that the investigator working with Becker had “admitted that he could be supporting a con game for living expenses on the part of Becker * * * but that he doubted it,” as he had only provided Becker with limited expenses. (225)

- The November 21, 1962, Bureau report noted further that Becker had once been associated with Max Field, a criminal associate of Mafia leader Joseph Sica of Los Angeles. (226) According to the report, “It appears that Becker * * * has been feeding all rumors he has heard plus whatever stories he can fit into the picture.” (227)

- On November 26, 1962, Becker was interviewed by the FBI in connection with its investigation of the Billie Sol Estes case on which Becker was then also working as a private investigator. (228) Becker told the Bureau of his recent trips to Dallas, Tex., and Louisiana, and informed them of the information he had heard about counterfeiting in Dallas. (229) At that point Becker also briefly discussed Carlos Marcello:

He [Becker] advised that on two occasions he has accompanied Roppolo to New Orleans, where they met with one Carlos Martello, who is a long-time friend of Roppolo. He advised that Roppolo was to obtain the financing for their promotional business from Marcello. He advised that he knew nothing further about Marcello. (230)

- Becker was briefly mentioned in another Bureau report, of November 27, 1962, which again stated that he allegedly made up “stories” and invented rumors to derive “possible gain” from such false information. (231)

- Three days later, on November 30, 1962, another Bureau report on the Billie Sol Estes case made reference to Becker’s trip to Dallas in September and his work on the case (232). The report noted that Becker was apparently associated with various show business personalities in Las Vegas (233). Further, a man who had been acquainted with Becker had referred to him as a “small-time con man.” (234)

And the report goes on and on in undermining this entertaining but dubious saga.

Becker’s reliability took another sharp turn for the worse just recently when in December 2018, on BlackOp Radio, a show Blake Smith should listen to in order to evaluate his sources, Len Osanic interviewed Geno Munari. Geno knew someone who met Carlos Marcello with a very nervous Edward Becker. In that interview, Geno explains how his acquaintance met Marcello and got to interview him years after the assassination, how he was accompanied by Becker and how it was quite obvious that Becker and Marcello had never met before.

In itself, this casts much doubt on the Marcello accusations which have circulated for decades and that Blake Smith has rehashed as one of his foundational arguments. This analysis, along with the Sylvia Odio section, point to another problem I have with the author’s research efforts: He does not seem to seek corroboration from primary sources when this is easily available. Furthermore, neither Reid nor Becker (who later co-wrote a book on John Roselli) are in his bibliography. So one must ask, with this many layers between the author and the primary data, where does he get his information?

It is very difficult to recount what the author’s position on a subject can be, because he speculates in so many directions that it can leave your head spinning. Here are some examples:

- If Marcello wanted to create distance between the assassination and the Mafia, you would think this would be reflected in the hit-team that was put together. In his top ten suspects in Dallas, the author names in fourth place Johnny Roselli, in fifth place Sam Giancana’s top enforcer Charles Nicoletti and Trafficante’s personal bodyguard Herminio Garcia Diaz is in third.

- Blake Smith expresses doubt that Alpha 66 leader Antonio Veciana ever met David Phillips because he only confirmed this after Phillips passed away. He does not believe the Veciana claim of having seen Oswald with Phillips in Dallas (p. 105). However, to prove that Oswald was never in Mexico City, he relates how Veciana said that Phillips offered him a large sum of money to lie about Oswald visiting a relative in Mexico City, and concludes that if Oswald were in Mexico City, why would one need to bribe someone to lie about it?

- And remember Marcello’s short list of cold-blooded, scummy killers that would be recruited to do the job? Here is one of the author’s reasons the hit team decided not to fire when they had Kennedy in their sights with his family close by: “one would think that women and children would be off limits to any shooter with an ounce of self-respect, when pondering firing a kill shot at the president, from afar or just from the sidewalk, behind the fencing. A sniper with a clear shot could not very well plant a bullet into the skull of a president in front of his loving spouse and offspring and expect safe quarter from any citizen or sympathetic anti-Kennedy supporter in the aftermath, when trying to escape capture. The whole country would have turned on such a heartless, coldblooded villain. Thus the “South Lawn Plot” was a total flop.” (p. 398)

- On page 164, he further confuses matters by writing: “But it had to be the president who had to be lured into place too, into the open somehow, in this scenario. Perhaps at an outdoor welcoming ceremony, or concert, or playtime with the children.”

- The author also states that a reason for the failure was that Oswald chickened out (page 321). Question: Did all the shooters chicken out simultaneously? Other question: What made Marcello think that he would not chicken out again firing from his place of work in Dallas?

- Then we have the October Surprise: “anyone who longed to gun down the president, at the White House or in his Washington parade. And it was all due to the power of chlorophyll: a healthy bright green. Nature’s green leaves and thick shrubbery saved the day” … ”Very large, full trees lined the South Lawn in particular, blocking the view from the sturdy Willard Hotel, and even in some locations the ground-level views from the sidewalk.” … “foiled by foliage.”

I do not even know where to begin with this one. How long did it take for these Keystone-Cops plotters casing the joint since September 26 to figure this out? Would the leaves having begun to turn orange improved the view that much? Not where I come from! Finally, living significantly farther north than Washington D.C., I highly doubted that the leaves begin changing colors a full two weeks before those in Quebec City. This is what is confirmed on any website for autumn tourists: “Fall is especially beautiful in the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia. Leaves begin to turn red and yellow in the middle of October. The timing and intensity of colour depend on temperature and rainfall. The peak of fall colors can be seen till the end of October, and then the trees start losing leaves.”

- As for his one bad apple in the Secret Service: this is a point he makes in his relatively good work in his Secret Service chapters and elsewhere. But the list kept growing to include Trip-Planner Perry, Kellerman, Greer and possibly others. And even here, the author tends to fall into the trap of using debunked sources, something that happened to me in some of my early writings.

Way back, I too fell for the Mafia-connected Judith Campbell hoax. Campbell claimed to be Kennedy’s mistress who acted as courier between Sam Giancana and Kennedy. One of the persons who edited my work convinced me to put a stop to this because she simply could not be trusted. In a list of ten outrages, the author explains why some in the Secret Service turned on JFK, including his alleged affairs with Mary Meyer and Judith Campbell, involvement in group sex and homemade porn, hotel hookers, the president’s gay lover, and drug abuse. While he does use the word “alleged” at times and also the qualifier “according to”, he rarely shows an inclination to explore the debunking of these sensationalistic claims. Not to say that JFK was a choirboy, but after reading “The Posthumous Assassination of John F. Kennedy—Judith Exner, Mary Meyer and Other Daggers” by Jim DiEugenio, I realized how much I had fallen for some of the worst exaggerations out there. Blake Smith continues to do so.

- In his chapter 4, on hate groups, he underscores links between them and the Mafia-linked persons of interest, such as the alleged ones between Joseph Milteer and Guy Banister that we will talk about below. Since I had not looked into this area very closely in the past, I found myself interested in the anecdotes presented. But here again the author provides little primary data when it comes time to proving meaningful links between them and the Marcello gang. It all becomes tenuous and fragile.

- Sometimes the author uses a source and then candidly puts on the brakes to point out serious credibility problems with the source. But he then keeps coming back to it. On page 196, he tells us about how Terri Williams, in a small town in Mississippi, remembered her classmates and teachers whooping it up after learning of the JFK assassination. The excited principal went from class to class proudly announcing his death. The principal even singled out a ten year-old boy’s father’s expert marksmanship in Dallas. And the Williams family was also congratulated for their Uncle Albert Guy Hollingsworth being part of the team. Terri’s story goes on to implicate the unstable, ex-marine uncle. She claims he became the Zodiac Killer. Since the Zodiac Killer was never caught, the author opines, “Who knows? Miss Williams might be right”. Terri did, however, “concede that her uncle was in reality a lousy shot, having once blown off one of his own toes.”

This goes on for seven pages, then eventually the author transparently states: “Her tale is compelling but she has not produced a shred of evidence to back it up … Some other online allegements [sic] by Terri Williams seem to become more suspect and farfetched-sounding [sic].”

Seven pages on an online source like that … Really! What’s worse is that after completely undermining her credibility, he still goes back to her at least twice in later sections to emphasize points. Now guess who makes it on to his list of top ten suspects in Dallas? In eighth place: Al Hollingsworth!

- His attitude towards the CIA’s involvement with this whole cabal is difficult to pin down. Sometimes we get the feeling that they are just a little bit pregnant, but then he will anecdote-drop key points that he leaves undeveloped and fluffs over their significance. On page 296, he dabbles a little bit in William Harvey, who helmed the ZR Rifle assassination program and who was close to John Roselli and hated the Kennedys. However, he then comes to a sudden stop around this intelligence subject. On page 248, he uses The Devil’s Chessboard to allude to Dulles perhaps conniving with Treasury Department head Douglas Dillon, but does not develop it much further. He alludes to some suspicious behavior by the CIA’s David Phillips around the Mexico City charade (p.81).

It now appears that Jim Garrison has been vindicated with respect to Clay Shaw, whose role as a well-paid CIA asset has been confirmed; moreover, many witnesses, judged credible by the HSCA, saw him in the company of Oswald and David Ferrie. Yet Clay Shaw is barely mentioned. He does describe the Bethesda military autopsy room on the night of the assassination as being filled with military men, but without understanding the implications.

Had he taken a little trouble to reflect on these important observations and added to them a consideration of both the timely propaganda efforts conducted in the blink of an eye by key CIA assets such as Hal Hendrix, Ed Butler and DRE members, all in synch with one another, as well as the ensuing cover-up, he would have seen that there is little probability this conspiracy was Marcello-led.

The Willard Hotel Plot

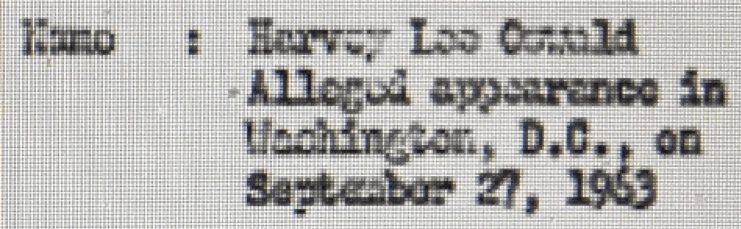

It goes without saying that I have issues with the author’s overall scenario. However, my interest in his book had more to do with his theory that there was a planned Washington plot in the works and that Oswald was there with a team of shooters who were in position at and around the Willard Hotel to fire away at the president. Let us see how he does in these areas.