In the two previous installments of this review of Can’t Get You Out of My Head (CGYOMH) by Adam Curtis, I covered his poor handling of things like financial chicanery, monetary policy, oil markets, the JFK assassination, and “conspiracy theories” in general. To conclude this review, I am going to cover some of the ways in which Adam Curtis beguiles the audience on crucial issues such as state criminality, the dual state, geopolitics, Western imperialism, and the West’s adversaries—Russia and China specifically. Finally, I conclude with a brief summation of the CGYOMH and an exhortation for us all to take a large grain of salt with anything produced by this BBC pied piper.

A Shallow Take on the Deep State

Curtis has a strange way of grappling with US imperialism and the country’s secret government which emerged after World War II. In the fifth episode of CGYOMH, Curtis mentions that the CIA had been manipulating political systems and overthrowing governments around the world without the knowledge of the US public. He then brings up the illustrious Hans Morgenthau and his assessments of the American shadow government. This whole section is baffling to me. First, Curtis identifies Morgenthau as “one of the most senior members of the US State Department.” Then he says that Morgenthau “had given this hidden system of power a name, […] the dual state.” According to Curtis, Morgenthau deemed this duality necessary because of the realities of international power politics. These dark clandestine tactics needed to be hidden from the public because acknowledging them would undermine Americans’ beliefs in their democracy and in their exceptionalism—beliefs that were necessary in the Cold War.

Curtis states that the US in the Cold War ran covert operations to overthrow 26 foreign governments in 66 attempts. Morgenthau, it is stated in CGYOMY, believed that this secrecy was creating a dangerous time bomb at the heart of America. Beginning in the 1960’s, these secrets began to be exposed by writers like former CIA officer Miles Copeland. In this section, Curtis even runs footage of a trailer from the original film adaptation of The Quiet American. The trailer is a montage featuring narration and clips from the movie which depict an American agent sowing chaos and violence “across all the Orient.” The film is certainly relevant to the discussion. That said, Curtis could have told the audience that the protagonist of the book and film is widely understood to be based on the activities of infamous CIA officer Edward Lansdale. Furthermore, Curtis could have also told the audience that Lansdale himself—acting on behalf of the CIA—was involved in the production of the film adaptation. To that end, the plot of the film was changed in such a way as to obscure the titular Quiet American’s responsibility for a terror bombing. The episode illustrates how the secret government was even manipulating the public through Hollywood—going so far as to alter those rare, informed critiques of US neocolonial imperialism in literature and film.

Morgenthau, the Rockefellers and The University of Chicago

But I digress. As mentioned above, Curtis’ treatment of Morgenthau and the dual state is strange. For one thing, Morgenthau did not give the dual state its name. The term comes from a German émigré named Ernst Fraenkel and his 1941 book, The Dual State: A Contribution to the Study of Dictatorship. The book described how alongside the normative state which operated lawfully, there emerged a prerogative state which operated lawlessly to serve as the guardian of the normative state.[1] Furthermore, Morgenthau is not most notable for being “one of the most senior members of the US State Department.” As far as I know, he never actually occupied a high position in the state department, though he did work there as a consultant under different US presidential administrations. Morgenthau is, however, quite famous for being the modern seminal classical realist philosopher in the field of international relations—a subdiscipline of political science. Why Curtis omits this is a mystery.

In fact, Morgenthau’s actual academic position during those years is very relevant to Curtis’ discussion of the dual state—i.e., CGYMONH’s exploration of the lawlessness of America’s postwar secret government, because Morgenthau was a professor at the University of Chicago. Famously described as Standard Oil University by Upton Sinclair, the University of Chicago has a unique relationship to the right-wing brain trust that has informed many imperial US strategies in terms of foreign policy and political economy. Perhaps most infamously, the University served as an incubator of sorts for the neoconservative, right-wing imperialists who were heavily influenced by German émigré Leo Strauss.

Strauss, who I will return to, himself first received Rockefeller funding thanks to the intervention of Carl Schmitt[2]—the jurist, political theorist, and prominent Nazi whose ideas informed the legal thinking of the Third Reich. In his exploration of the dual state, Curtis would have been better served looking at Carl Schmitt in order to situate the lawless US pursuit of “security.” Summarizing Schmitt, I have written elsewhere[3] that he

…wrote famously, “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.”[4] The state of exception “is not codified in the existing legal order.” It is “characterized as a case of extreme peril, a danger to the existence of the state.” The gravity of the state of exception is such that “it cannot be circumscribed factually and made to conform to a preformed law.”[5] Sovereignty for Schmitt is defined by the ability to decide when the state of exception exists and how it may be eliminated. Any liberal constitution can hope, at best, to mandate the party with which sovereignty rests.[6]

In other segments of CGYOMH, Curtis mentions the critiques of Western leftists who argued that the essence of fascism had not been extinguished with the Allied victory in World War II. In the prior installment of this review, I covered Curtis’ shortcomings in terms of exploring this perspective. In his treatment of lawlessness and the dual state, Curtis compounds those errors. With Carl Schmitt and his University of Chicago descendants, there is a fairly clear German antecedent to the institutionalization of American state criminality that was established with the outbreak of the Cold War and never abandoned (i.e., an historical precursor to the lawlessness of a nominal constitutional republic). The reader may recoil at such a comparison, but the analogy is not particularly hard to grasp, psychic resistance notwithstanding. Even in terms of their respective creations, both were borne of bogus pretexts which conjured an existentially threatening Communist menace. The exceptionalist or legally unconstrained Nazi state took its mature form in the wake of the Reichstag Fire, a terror spectacle which the Nazis likely facilitated.[7] Likewise, much of the early postwar hysteria over the Soviet Union derived from erroneous Anglo-UK accusations that Stalin had grossly violated the postwar terms regarding Eastern Europe which had been negotiated at Yalta.

All this is not to say the US is a new Nazi Germany. Only Nazi Germany was Nazi Germany, just as only the US empire is the US empire. That said, it is worth noting that in key national security documents like NSC 68, Cold War US policymakers explicitly argued for an exceptionalist approach to combating the supposedly existential threat posed by the Soviet Union.[8] I have written that such documents, in effect, served to grant

…authority to the state to covertly conspire to violate the law. Since the US Constitution’s supremacy clause establishes that ratified treaties are “the supreme law in the land” and the US-ratified UN Charter outlaws aggression or even the threat of aggression between states, CIA covert operations are carried out in a state of exception. Given that the authority for these operations has never been suspended and the operations have been a significant structural component of the US-led world order, [I coined] the term exceptionism […] to describe the historical fact of institutionalized state criminality.[9]

Schmitt, Strauss, and the Cold War

To explain the duality and lawlessness of modern Western states, it is practically essential to discuss Carl Schmitt. In the German case, the Weimar Republic gave rise to a despotic dualism that quickly devoured the Republic, such as it was. In the US, the state’s lawful/lawless duality arose from the Cold War national security state which had been empowered by the supposed existential threat posed by communism. In the US case, the lawful democratic state (or public state) was never completely subsumed by authoritarian forces. This remains true, even if—as I have argued—anti-democratic forces in US society have consolidated so much wealth and power as to constitute a deep state that exercises control and/or veto power over democracy and the national security state. In my dissertation, I describe a tripartite state comprised of the public state, the security state, and a deep state.[10]

Let us return to Leo Strauss, Morgenthau’s colleague at the University of Chicago. Strauss was an anti-Enlightenment thinker whose affinity for liberal democracy went only so far as to acknowledge that it served an important mythical function in legitimizing the hegemonic US project. One German commentator summarizes Strauss’ thinking about democracy:

[L]iberal democracies such as the Weimar Republic are not viable in the long term, since they do not offer their citizens any religious and moral footings. The practical consequence of this philosophy is fatal. According to its tenets, the elites have the right, and even the obligation, to manipulate the truth. Just as Plato recommends, they can take refuge in “pious lies” and in selective use of the truth.[11]

To summarize, Strauss and his mentor (of sorts) Carl Schmitt were both essentially Hobbesians. In the tradition of English thinker Thomas Hobbes, they saw the world as a dangerous and threatening place, the peril of which necessitates the creation of—and submission to—“the sovereign” or more simply, the state. The overriding imperative of the state is security, because without it, all of society is imperiled. Therefore, any measures necessary to secure the state are not just acceptable, but basically necessary. Germany infamously took Schmitt’s Hobbesian logic to a notable conclusion. Writing largely after World War II in the US, Strauss in essence advocated for state duality. He grudgingly accepted liberal democratic myths and formal institutions, while at the same time advocating for wise men like himself and his acolytes to counsel leaders, deceive instrumentally, and effect desired political outcomes in a top-down fashion. It is a mystery as to why Curtis does not mention Strauss given that the philosopher was a central figure in his interesting, but flawed, documentary series, The Power of Nightmares.

Let us return now to CGYOMY’s treatment of Morgenthau. Curtis offers a brief summation of the realist philosopher’s thinking on the dual state that is, at best, very incomplete—and quite likely wrong. Previously and elsewhere, I wrote about Morgenthau in the same context that Curtis situates him in.

As a 20th century analog of Thomas Hobbes, Schmitt elucidated a grim, illiberal understanding of the true nature of power within the state. Recognizing this same illiberal essence, other theorists described the “state of exception” and the securitization of politics as a slippery slope that would create authoritarianism, perhaps with pseudo-democratic trappings.[12] In the early years of the Cold War, seminal realist Hans Morgenthau would comment on these illiberal forms emerging within the American political system. He identified a change in the control of operations within the U.S. State Department. The shift was toward rule according to the dictates of “security.” Morgenthau wrote, “This shift has occurred in all modern totalitarian states and has given rise to a phenomenon which has been aptly called the ‘dual state’” In a dual state, power nominally rests with those legally holding authority, but in effect, “by virtue of their power over life and death, the agents of the secret police—coordinated to, but independent from the official makers of decision—at the very least exert an effective veto over decisions.”[13] Thus does Morgenthau describe a dynamic akin to Schmitt’s conception of sovereignty.

To wit, Morgenthau did expound on Schmittian ideas about the sovereign and he addressed the dual state concept derived from two of the Germans discussed above: Carl Schmitt and Ernst Frankel.[14] To my knowledge, however, Morgenthau’s most noteworthy exploration of the subject was the 1955 New Republic article cited above. In this essay, he did not argue that the emergence of this dual state was positive or necessary. Rather, he bemoaned how the US State Department had been decimated by the dictates of an overweening security apparatus and he explicitly situated this dual state in the context of totalitarianism. The Nazi example would have been obviously at the forefront of Morgenthau’s mind. At the very least, Curtis should have mentioned the New Republic article and its critique, since it was written in a major US magazine. More recently, the 1955 Morgenthau essay was discussed in a scholarly article on the subject of the deep state by Swedish scholar Ola Tunander in 2009.[15]

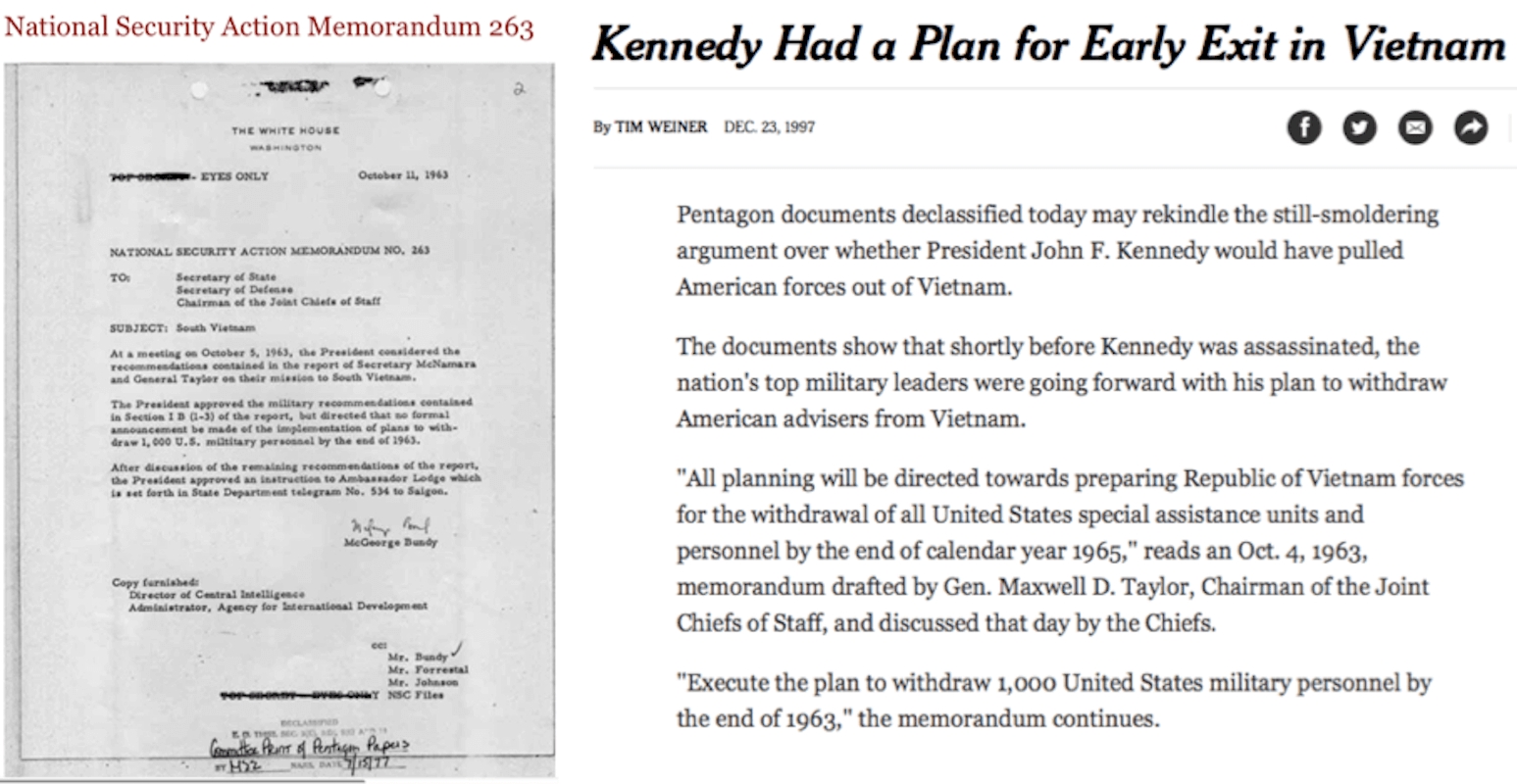

Curtis touches on the institutionalized lawlessness and thus the duality of the state in the US, but he fails to hash out the implications. With his blinkered treatment of Morgenthau, his omission of Schmitt and Strauss, and with his treatment of the JFK assassination, the filmmaker cannot bring himself to confront the American deep state and the cataclysmic historical episodes in which it was decisive. Discussed in greater depth in the previous installment of this review, Dallas was a coup d’état profounde—a stroke of the deep state. It is nonetheless interesting that Curtis spent any time at all covering the assassination and the deep state.[16]

Imperial Security

The historical limited hangout approach deployed by Curtis permeates the accounts of Western imperialism in CGYOMH. At one point, the film briefly covers the assassination of Congo’s first elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. To his credit, Curtis acknowledges CIA involvement in Lumumba’s death. He acknowledges that the US installed the brutal puppet Joseph Mobutu, but for some reason he fails to mention that it was Mobutu’s forces who arranged the execution of Lumumba. He states that the abrupt Belgian withdrawal plunged Congo into crisis. But he neglects to mention that this was by design—part of a plot to break away from Congo its most resource rich province of Katanga.[17] Curtis credulously reports that the US was worried that without intervention, Congo’s copper might fall into communist hands. He neglects to mention that it was the West’s refusal of help which forced Lumumba to seek Soviet aid. There is reason to believe that this was done by design, as it then gave Allen Dulles the pretext to assassinate Lumumba—an action which Eisenhower went on to authorize.

The assassination was carried out in such a time and fashion as to indicate that people like Dulles feared a change in policy under the incoming Kennedy administration. Kennedy’s policy was much more sympathetic to Lumumba than that of Eisenhower and Dulles, but the young Congolese prime minister was killed 72 hours before Kennedy had been sworn in as president. With the facts selected and presented as they are in CGYOMH, the reader gets the impression that policies such as this were decided on the basis of myopic, but earnest, anticommunism. With Curtis, the obvious economic interests are ignored or minimized. But with Curtis, the implication is that another set of those darn bureaucrats are once again too much enthrall to another set of wrongheaded ideas.

When one takes the longer view, this explanation falls apart. As one of the most resource-rich places in the world, Congo was brutally exploited and expropriated by Europeans for more than a century before the Cold War. During the Cold War, the plunder continued, overseen by the US-installed puppet following the assassination of Lumumba, the man who famously asserted that the resource wealth of Congo should be used for the benefit of the Congolese people. After the Cold War and up to the present day, the Congolese have been subjected to unspeakable violence on a massive scale, while the pillage of its resources has continued apace. But since Curtis filters everything through his anti-leftist lens, he cannot present cogent analysis, even when the episodes under discussion are pregnant with weighty implications.

The Dark Art of Western Geopolitics

In CGYOMH, Curtis looks at numerous examples of Western imperialism in places like Iraq, China, and Africa. The series would have benefitted from a discussion of geopolitics—specifically the theories of Halford Mackinder and the more contemporary policymakers and scholars who have examined Mackinder’s ideas and their applications. The Brit Mackinder looked at the world and saw that Europe, Asia, and Africa were really one massive “world island” containing most of the world’s resources and productive capacity. With Britain located on the periphery of the world island, its imperial strategists needed to assert control over key areas and destabilize or Balkanize regions to preclude any counter-hegemonic force from uniting the enormous landmass.

The British applied this logic throughout their imperial reign. Both world wars can be seen, in part, as consequences of the applications of Mackinder’s theses. As one example, the Anglo establishment was much alarmed by Germany’s proposed Berlin-Baghdad railway. This project would have integrated Germany, Central Europe, the Balkans, and the oil-rich Middle East into a massive German-led industrial powerhouse. Interestingly, the radical historian Guido Preparata sees a Russian hand in the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and Russia was, of course, Britain’s ally at the time.[18] Prior to World War II, the Soviet Union’s existence threatened the great powers in Western Europe and the US. This no doubt informed the thinking of Anglo-US elites who helped rebuild and fuel, respectively, the German and Japanese war machines. With other factors at work—and with geopolitics not being an exact science—the anti-Soviet Anglo-American elites did not get their preferred outcome. Germany chose softer targets first before launching their ultimately ruinous campaign against the Soviet Union almost two years later.

When the Japanese got into military conflict with the Soviets in 1939, they were soundly defeated at Nomohan. In the aftermath, Japan signed a non-aggression pact with the USSR. This would prove crucial in shaping the war’s outcome. In 1941, the Germans invaded Russia and were headed for Moscow. Since there was little threat of a Japanese invasion, the Soviets were able to send divisions from the Far East and stop the Germans just short of the capitol. The Soviet-Japanese non-aggression pact held until the last days of the war when Soviet forces swept through Manchuria, actually killing more Japanese than the atomic bombings. Though in Western historical memory, Hiroshima and Nagasaki quickly overshadowed the Soviet invasion, considerable evidence indicates that it was the crushing Japanese defeat in Manchukuo—along with the threat of an impending Soviet attack on the main islands—that actually prompted the Japanese surrender to the Americans.[19]

As historian Alfred McCoy points out, a central strategy of the postwar US empire was to rebuild the defeated Axis powers and make them essentially US satellites. With Germany and Japan reconstructed as largely demilitarized, capitalist industrial powerhouses, the US controlled both “axial ends” of Eurasia, Mackinder’s “world island.”[20] Trade and capital flows went across the Atlantic and across the Pacific, making the US the richest empire in world history. This was by design. In retrospect, the US war in the Pacific was particularly a war for postwar hegemony. And some have argued the dual atomic bombs kept Russia out of Japan.

The American Century

American claims to legitimate possession over Hawaii and the Philippines—where the Japanese attacked the US—were dubious at best. They are part of a history that goes all the way back to the 1850’s. Following the imperialist Mexican-American War and the US acquisition of California, enterprising officials and businessmen looked to the Pacific to enrich the US and themselves. Starting as early as Matthew Perry’s 1853 expedition to Edo, US trade and investment in the Pacific were too lucrative to pass up. Hence, we have the absurd fact that in the Spanish-American War, ostensibly fought for Cuban independence, the first shots were fired as the US attacked the Spanish Philippines.

Prior to US entry into World War II, Life magazine publisher Henry Luce made a case for American empire. As a mouthpiece for the Wall Street-dominated Council on Foreign Relations, Luce made the argument in his “American Century” essay, laying out the case for US hegemony over the postwar capitalist world. While much of his essay was couched in “liberal” rhetoric, in one passage he was quite candid about Asia.

Our thinking of world trade today is on ridiculously small terms. For example, we think of Asia as being worth only a few hundred millions a year to us. Actually, in the decades to come Asia will be worth to us exactly zero—or else it will be worth to us four, five, ten billions of dollars a year. And the latter are the terms we must think in, or else confess a pitiful impotence.[21]

Geopolitics, control of resources, markets, financial and political systems…these are the aspects of the US hegemonic reign that allow us to make sense of the activities of the intelligence agencies, the military, the business elites, and the public officials who serve these constituencies. Curtis fails to offer cogent analysis of these deep political issues. Thus, the quirky myopia of his commentary on things like covert operations, the dual state, and “humanitarian intervention.” It is worth asking whether British state television would ever sponsor an honest, penetrating documentary film that would bring the reality of our crumbling systems to a vast audience. Does the BBC exist to act in the public interest by providing the range and depth of programming needed for enlightened democratic public debate? Or does the prestige media outlet serve to entertain and manufacture consent?

Losing the Great Game on the Eurasian Chessboard

The most famous contemporary adherent of Mackinder’s geopolitical theories was Zbigniew Brzezinski. Co-founder of David Rockefeller’s Trilateral Commission and US National Security Advisor under Carter, Brzezinski expounded on post-Cold War geopolitics with his 1997 book, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives. In it, he argued that “keep[ing] the barbarians from coming together” was a “grand imperative of imperial geostrategy.”[22] By “barbarians,” Brzezinski was referring to Russia and China. These two countries have indeed come much closer together in the intervening years, largely in response to their shared grievances under US hegemony. Termed the “rules-based liberal international order” by US officials and their media/academic courtiers, the Post-Cold War era of unipolar US dominance has by-and-large allowed the US to essentially make—and break—the “rules” of international politics according to its whims. A small number of countries have resisted US dominance with varying degrees of success. In the 21st century, three of them—Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya—saw their governments overthrown and their societies devastated. In Eurasia, an “axis of resistance” has emerged which includes most notably China, Russia, Iran, and Syria—with Iraq in the wings as the US still refuses to honor the Iraqi parliament’s request to withdraw US military forces from the country.

In this context, it should be noted that much of Curtis’ previous documentary series, Hyper-Normalization, devoted much screen time to denigrating two Western targets—Libya and Syria—in a multitude of dubious ways. True to form, the real villains in CGYOMH are (surprise!) Russia and China. The countries, according to Curtis, have one thing in common: they believe in nothing. Curtis states this repeatedly, though he contradicts himself, somewhat, by also stating that the Chinese only believe in money. The BBC should spring for some kind of editor to make sure that Curtis’ chauvinism is at least internally consistent, but, alas, such is not the case.

The Soviet Union of CGYOMH appears to be the most depressing society that ever existed. Stock footage is used to depict a country of hopeless, nihilistic, victims of communism. While the post-Soviet era of Boris Yeltsin is acknowledged as a disaster, Curtis minimizes the extent to which the shock therapy privatization was a Western operation that enriched Western finance—along with that class of underworld-connected figures who became known as the oligarchs following their seizure of the Russia’s patrimony. Curtis also does not adequately explore the US interference on behalf of Boris Yeltsin in the 1996 Russian election. Portrayed in a glowingly brazen fashion on the cover of Time magazine, those US operations were of a scale far greater than even the most fanciful accusations of Russian interference in the 2016 US election.

The true Russian villain of CGYOMH, predictably, is Vladimir Putin. To my surprise, and to the credit of Adam Curtis, he does largely dismiss Russiagate. Without spending too much time on the subject, Curtis suggests that Russiagate paranoia was symptomatic of US anomie, insecurity, and paranoia. On the one hand, it is good that even with his highly negative take on Russia, Curtis doesn’t stoop to regurgitating Russiagate claims that are thoroughly debunked—most notably by Aaron Mate in outlets like The Nation magazine and The Grayzone website. Too bad Curtis doesn’t look at the role of the dual/deep state in concocting and maintaining the hoax. CGYOMH spends a good amount of time addressing various intelligence capers. It could have been illuminating to see the Russiagate saga portrayed in a well-produced documentary film.

Putin: That Dirty Guy!

Instead, Curtis tells us that the dream of turning Russia into a liberal democracy went wrong and a new rapacious oligarchy came to power. At the highest levels of power, did the US ever want to see Russia become a prosperous democracy? Russia was subjected to structural economic changes that much of the rest of the world has experienced under US hegemony—privatization, austerity, massive upward transfer of wealth, and capital flight. Given the negative results of neoliberalism in the last 40+ years, why is it not assumed that those outcomes are intentionally brought about to further enrich US/Western elites and immiserate most people on purpose?

Furthermore, with Russia, there are additional reasons to suspect that US elites deliberately wrecked and polarized Russian society. After the Gulf War, neoconservative Paul Wolfowitz said, “[W]e’ve got about 5 or 10 years to clean up those old Soviet regimes—Syria, Iran [sic], Iraq—before the next great superpower comes on to challenge us.”[23] Subsequent covert and overt US actions in the Balkans, Georgia, Libya, Ukraine, and Syria all demonstrate how the US has time and again launched military interventions in ways that threatened post-Soviet Russia’s national interests. US elites and the corporate media were major supporters of Boris Yeltsin, whose reign was an unmitigated disaster for the Russian people. These same actors now despise Vladimir Putin, a statesman who—shortcomings notwithstanding—has presided over an era in which conditions in Russia have much improved from the situation he inherited. The US media treatment of the two Russian leaders belies any claims of made about US leaders being concerned about the well-being of the Russian people in the Putin era.

In episode six of CGYOMH, Curtis states that Putin was selected by the Russian oligarchs to rule Russia. My understanding was that he was first handpicked by Boris Yeltsin—an historical oddity given how the two men seem like polar opposites. At the time of his anointing, Curtis tells us, Putin “was an anonymous bureaucrat running the security service and a man who believed in nothing.” Having installed the nihilist Putin as president, the oligarchs thought they would continue to dominate the country. Then, as Curtis so often tells us, “something unexpected happened.” A nuclear submarine exploded and sank to the ocean floor in August of 2000. The uncertainty about the fate of the crew and the eventual news of their deaths served to outrage Russians.

Eventually, Vladimir Putin came to Murmansk to address the public and the grieving families. Curtis tells us that Putin, “to save himself, turn[ed] that anger away from himself and towards the very people who put him in power,” i.e., the oligarchs. Putin told Russia that it was the corrupt oligarchs in Moscow who, by stealing everything, had destroyed the Russian military and Russian society. Instead of suggesting that Putin was using his office to address legitimate grievances on behalf of the vast majority of the population, Curtis tells us that Putin had instead merely “discovered a new source of power”—the anger of the people.

Even with his new source of power, Putin continued to believe in nothing and to have no goals according to CGYOMH. A Russian journalist is quoted talking about how under Putin there is no goal, no plan, no strategy…only reactive tactics with no long-term objectives. Later, Curtis quotes another Russian journalist who claimed that what Putin had really done was to take the corruption of the oligarchs and move some of into the public sector so that Putin and his cronies in the government could get in on the corruption: “The society Putin had created was one in his own image. It too believed in nothing.” The journalist was later murdered, outrage ensued, yet things did not improve. However, oil prices soon exploded, serving to ignite a bonanza of Russian consumerism. Cue the footage of a cat wearing a tiny shark hoodie, sitting atop a Roomba, gliding over a kitchen floor, pursuing a baby duck. This, presumably, is some kind of metaphor for the directionless nihilism of Russia. Take heart, Anglo-Americans: Whatever our problems, we have yet to see such horrors in the freedom-loving West.

Curtis goes on to check all the obligatory boxes regarding Putin and Russia. The group Pussy Riot makes an annoying appearance. Alexi Navalny, a figure with very little popular following in Russia, is credited by Curtis with “chant[ing] a phrase that redefined Russia” for a, theretofore, apolitical generation. “Party of crooks and thieves!” chanted Navalny. This, we are told, made Putin furious at the ungrateful new middle class. In response, a paranoid Putin “shapeshifted again.” He created the “Popular Front,” a Russian nationalist organization. Worse: “He summoned up a dark, frightening vison from Russia’s past,” saying that “Eurasia was the last defense against a corrupt West that was trying to take over the whole world.” Putin was articulating “a great power nationalism that challenged America’s idea of its exceptionalism.” Putin, Curtis tells us, was promoting “Russian exceptionalism!” Flash to footage of the Nighthawks, a gauche pro-Putin motorcycle gang of Russian nationalists. Curtis then asserts that the Nighthawks are promoting a “paranoid conspiracy theory” that the West, led by the US, is trying to destroy Russia.

Adam Curtis: Reality Check I

Where to begin with Curtis’ treatment of Russia? Putin as alleged nihilist is simply a cheap shot. The man is obviously a nationalist. This cannot be lost on Curtis, but he refuses to grant Putin even that. Instead, Putin’s moves to curb the oligarchs’ power and his efforts to resist Western geopolitical moves are all presented as crass opportunism in the service of personal aggrandizement. What should Putin and the Russians have done after Yeltsin? Curtis cannot answer this question, so he never poses it. Putin is indeed a figure that can be criticized on a number of fronts. Most significantly, his measures against the oligarchs went nowhere near far enough. The legitimacy of their vast holdings is dubious at best. If Russia were to function on a more democratic basis, one of the most popular measures would be to nationalize or otherwise redistribute what are widely perceived as the ill-gotten gains of these propertied elites. But since Curtis is first and foremost an anti-leftist, there is no discussion of such possibilities.

Nor is there any discussion of the steps Putin did take against particular oligarchs that he deemed (with at least some justification) to be acting against the national interest. At least Curtis does not endorse Russiagate. Nor does he mention the implausible Novichok poisonings that Western security services attribute to Putin himself. These omissions are interesting in and of themselves. What of Putin’s assertion that Eurasia is the last bulwark against a US-led West bent on world domination? Curtis mocks the very notion. He does not mention that Zbigniew Brzezinski explicitly made the same argument about Eurasia over twenty years ago. Keep in mind that Brzezinski was, in my estimation, part of the more sober wing of the US imperial hivemind. He could be characterized an Establishment liberal imperialist in contrast to the unhinged neoconservative imperialists.

Going back further in US-Russian relations, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted JFK to endorse a preemptive nuclear strike on the Soviet Union to be carried out in the final months of 1963. Kennedy opposed such an unprecedented act of human barbarism. Notably, Kennedy himself was assassinated under suspicious circumstances during that same proposed window of time. Many commentators have noted how NATO has seemed to move closer and closer to Russian borders.[24] The late Robert Parry wrote often about the role of the US Embassy during the uprising in Ukraine.[25] In short, there is much historical and contemporaneous evidence that the US has sought to encroach Russia—or to at least deprive the country of any ability to impede US global hegemony. Realizing that such is the case, Russia under Putin has allied itself with its historical rival, China.

Curtis, with China in his Sights

At this point, it should be clear that Curtis is going to rubbish China, the most long-lived civilization in human history. Like many things in his film, Curtis does not appear to be an expert on Chinese history. On China, CGYOMH is at its most schizophrenic. Curtis acknowledges how the British devastated Chinese society with the Opium Trade and the Opium Wars. He actually soft-pedals much of this. For example, he could have mentioned that Western imperialism led to the social crises which spawned the Taiping Uprising, a conflict that killed perhaps as many as 15 million Chinese around the time of the US Civil War. Or he could have spent more time talking about the indemnities that poor China had to pay to the rich West after the Opium Wars and the so-called “Boxer Rebellion.” As I understand it, the Chinese paid over a trillion dollars’ worth of gold in today’s values as per the terms of the Boxer Protocol. This was for resisting British imperialism! The debt had only grown larger with interest before it was cancelled during World War II, when China allied with the US and British against Axis Japan. Nor is there any mention of how Japanese imperialism against China in the 1930’s was aided by the West. Such was the case up until 1940, when the US put an embargo on Japan after the Japanese invaded French Indochina. The embargo is what led to the attack on Pearl Harbor. All told, the Chinese may have lost 20 million people in the war with Japan.

What about China after 1949? It being a communist country, Curtis is a harsh critic. Yet true to form, his critique is quirky and idiosyncratic. CGYOMH does not much mention the disastrous Great Leap Forward. Curtis discusses the Cultural Revolution, but does not explain it very well at all. Instead, it is depicted as a bizarre power play by Mao vis-à-vis his ambitious and megalomaniacal wife, Jiang Qing. The amount of time Curtis spends on Jiang Qing is completely out of proportion to her historical importance. To my understanding, she is a deeply unpopular figure in China and she comes across worse to Western students of this period of Chinese history.

At a time when a deeper understanding of Chinese history in the West is desperately needed, Curtis does a great disservice with CGYOMH. With his cursory mentions of the Opium Wars and later of the racist Fu Manchu movies, he attempts to place a type of multicultural fig leaf over his smug imperial chauvinism. The fall of Dynastic China and the struggles of the People’s Republic of China are never properly contextualized. China was hopelessly disadvantaged against the technologically superior West in the last century of the Qing Dynasty. Due to the predations of the Western powers—and then those of the West’s Asian imitator, Japan—China was in such a horrendous state as to experience the rarest of events: a successful social revolution.

China after 1949

Though nominally Marxist, there was no clear way for the victorious Chinese communists to apply Marxist principles to the situation that Mao inherited. Marx saw communism as something that was a progression: from feudalism to capitalism…and eventually to communism. He explicitly stated that a communist revolution could not succeed in China or Russia, because they did not have the necessary levels of development to create the class dynamics necessary to seize the means of production. Those requisite industrialized means of production had not yet come into being outside of the Western European world, thus Marx thought that Germany was the most likely place for Communism to arise. By the 1960’s, with China having suffered some spectacular setbacks, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution. Part political struggle, part cultural crusade—it marked a time of tremendous upheaval in Chinese society. Across China, problems of the revolution were attributed to those elements of the millennia-old Chinese culture that hadn’t been discarded. As a result, the Cultural Revolution produced many tragic spectacles, including the destruction of untold numbers of great and small works of art and architecture as part of a campaign to exorcise a multitude of historical traumas.

In this context, CGYOMH is frankly offensive in its repeated assertion that the Chinese, like the Russians, believe in nothing. Western imperialism—practiced by Europeans and then the Japanese—wrought unimaginable misery in China. It led to enormous political and cultural upheavals that most Westerners cannot fathom. In the wake of the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping took over the role as China’s helmsman. The free-market reforms introduced in this era served to slowly modernize China by integrating it into the international economy. This development also caused social dislocations and instability, with matters coming to a head of sorts during the so-called “Tiananmen massacre.”

In the wake of the events of 1989, Chinese leaders had to grapple with the fact that the legitimizing communist ideology was insufficient. The Cultural Revolution had disoriented the Chinese people. In some sense, it robbed them of their cultural heritage. But the history, myths, legends, and spiritual practices of the past were decidedly incompatible with Marxist ideology. Furthermore, the 1989 reality of vast industrial production for the international market economy was incompatible with Marxism as well as with traditional Chinese culture wherein merchants were regarded ambivalently, at best. In response, China began to grapple anew with the past even as present conditions were changing at a dizzying pace. In the wake of that tumultuous 1989, the Chinese Communist Party commissioned a television production of the Ming Dynasty novel (set at the end of the Han Dynasty), Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Such was the dramatic disavowal of Cultural Revolution era efforts to de-Sinify China. China’s cultural inheritance was rehabilitated in the service of Chinese unity.

Adam Curtis: Reality Check II

For Curtis, none of this historical context is necessary. China, like Russia, is to be understood as a profoundly depressing society. Again, as Curtis would have it, China today believes in nothing while also believing only in money. Chinese organized crime is out of control. China is excessively militarized. The Chinese Communist Party is terrified of its own countrymen. The Chinese state surveilles and oppresses the citizenry. Average Chinese people have no good prospects because “the princelings” (the children of Chinese elites) are hoarding all opportunities thanks to “ultra-corruption.” This is the China presented in CGYOMH.

Adam Curtis wants us to bear witness to the rise and fall of the Chinese official, Bo Xilai. Frankly, I cannot even figure out what CGYOMH is trying to say about Bo Xilai. I followed the story a bit when it was an international scandal in the news. I could never arrive at any salient take on the saga and Curtis does not clarify matters here. Bo did have some populist appeal. And he did seem to have some Anglophile tendencies and associations that the state would not have welcomed given Bo’s position. The whole thing seems like inside baseball—Chinese Communist-style. Perhaps this is the point: China is to be understood as an inscrutable, mysterious Oriental despotism.

Were Curtis to be objective, he would need to inform the audience that the only significant tangible improvements in the well-being of humanity during the last 40 years are due to Chinese progress. The rest of the world—largely following US-dictated economic prescriptions and models—has stagnated or regressed with the exception of the superrich. Meanwhile in China, a billionaire class did emerge, but not without socio-economic conditions for the general population steadily improving. Unlike in the West, Chinese adults who believe that their children will be more prosperous than themselves are not delusional. China’s “militarism” seems not at all unreasonable given the US military bases encircling the country. Furthermore, China spends much less on the military that the US in both relative and absolute terms.

For a Westerner to decry Chinese organized crime is laughable given the US governments’ partnerships with underworld figures like Meyer Lansky, “Lucky” Luciano, Santo Trafficante, Sam Giancana, the KMT, the anti-Castro Cubans, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the Contras, Ramon Guillen Davila, etc, etc, etc. And while there are, no doubt, privileged Chinese “princelings,” at least the Chinese can plausibly argue that their well-heeled heirs are not part of a class project to perpetually keep the bulk of the population in a state of material insecurity. In the US (and Curtis’ UK is not that much different), every aspect of life—food, housing, education, health care—is an avenue for rent-seeking and profiteering. And while aspects of the Chinese surveillance state are indeed Orwellian and alarming, it is worth keeping in mind that Western depictions of its adversaries are invariably unreliable and incomplete. Furthermore, and as Ed Snowden revealed, the US is no slouch when it comes to totalitarian surveillance. And even with the vast wealth in the US, we still lead the world in depriving our citizens of liberty in the harshest way: In both absolute and per capita terms, no country incarcerates more of its own citizens than the US.

The Garden Paths of Adam Curtis

In conclusion, I cannot recommend Can’t Get You Out of My Head except as a case study in sophisticated propaganda. The filmmaking talents of Adam Curtis are, as ever, impressive. However, the film’s commentary on the West is marred by a consistent failure to acknowledge the class interests that—when properly understood—illuminate so much of the unfortunate foolishness that Curtis attributes to bureaucrats and other members of the middle circles of power. The film’s deeply flawed explanations of financial/monetary matters represent a missed opportunity to explain crucial information to a badly misinformed public. Curtis’ treatments of Kerry Thornley and the JFK assassination are inexcusable, given all that we know now. His superficially revelatory discussion of the dual state represents a lost opportunity to demonstrate how the state has become our world’s most impactful and prolific lawbreaking entity. Lastly, when Curtis skewers entire swaths of humanity like Russia or the Chinese, the viewer should not lose sight of the fact that the filmmaker is on state television defaming the state’s enemies.

Imperialism, in a word, is what Curtis can’t deal with. All the aspects of CGYOMH which I criticize in these reviews—they all pertain to Curtis and his failure to call an imperial spade a spade. I would like to assign Curtis a few books on the subject. Michael Parenti would be a good place to start. He defined imperialism as “the process whereby the dominant politico-economic interests of one nation expropriate for their own enrichment the land, labor, raw materials, and markets of another people.”[26] Compared to Curtis’ muddled ideology, Parenti’s definition can much better explain what CGYOMH bungles—namely: post-Bretton Woods dollar hegemony, the oil shocks, the Third World debt crises, neoliberalism, anti-communism, CIA covert operations, so-called “humanitarian” wars,” the postwar rise of America’s secret government, the Iraq War, and the various financial crises which always end up benefiting those “dominant politico-economic interests.” Since Curtis cannot bring himself to acknowledge the imperial elephant in the room—except obliquely or in the distant past—he cannot properly explain how the empire has devoured the republic. Without addressing the central thrust of America’s drive for global hegemony, Curtis cannot understand how this enormous concentration of wealth and power has transformed the state.

Therefore, Curtis cannot illuminate the goings-on in the higher circles. Notably, he cannot hope to understand or explain the JFK assassination. Kennedy, for all his Cold Warrior posturing and/or pronouncements, did understand imperialism. In 1957, he gave a speech condemning French imperialism in Algeria. Said Kennedy on the Senate floor:

[T]he most powerful single force in the world today is neither communism nor capitalism, neither the H-bomb nor the guided missile—it is man’s eternal desire to be free and independent. The great enemy of that tremendous force of freedom is called, for want of a more precise term, imperialism. […] Thus the single most important test of American foreign policy today is how we meet the challenge of imperialism, what we do to further man’s desire to be free. On this test more than any other, this Nation shall be critically judged by the uncommitted millions in Asia and Africa.[27]

Much of the shift from colonialism to neocolonialism occurred in the 1950’s and 60’s. It was managed, often through covert operations, by the United States. Kennedy, as seen above, sparred with the Eisenhower administration (most notably, the Dulles brothers) over these policies. He supported the Third World nationalists who wanted their countries’ resources to improve the lives of their own impoverished citizens. Though Kennedy was against communism—sometimes opportunistically so—I believe the evidence today shows that he sought to end the Cold War. He pursued such a course in part to remove the threat of nuclear annihilation. But Kennedy also must have realized that the Cold War was an overriding structural constraint to any serious progressive reforms—both in the US and in the world. As long as every conflict was viewed in the Manichean, zero-sum terms of the Cold War, no US President had freedom to pursue any kind of reasonable foreign policy without encountering tremendous resistance. One can make a good argument that for his threat to the empire, Kennedy was killed. And it makes Curtis look an even bigger fool. Can he really not know that Kerry Thornley despised Kennedy over JFK’s devotion to what Lumumba stood for: a unified, independent, non-imperial Congo. President Johnson returned the US to the CFR/Acheson/Eisenhower/Dulles imperial consensus, reversing JFK’s policies in some of the world’s largest and most resource-rich countries. LBJ’s America would go on to attack the formerly colonized countries of Congo, Brazil, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Only Vietnam was able to hold on to its national sovereignty, but at an enormous cost.

Curtis cannot grapple with JFK, just as he cannot deal squarely with those other aspects of Anglo-US imperialism. His pitiful rubbishing of the empire’s enemies seems to be his way of saying, in the midst of the collapse of US hegemony, “Look! Look at them! They have bad systems of power too—worse even!” In these tumultuous times, this is not what is needed for British or American audiences. We do not need to be fixated on what our leaders tell us is bad about our much less powerful “enemies.” These are fatal flaws in his filmography. While parts of Adam Curtis films like The Century of the Self and The Power of Nightmares are well-done, they invariably lead the viewer down garden paths in such a way as to muddle understanding and obscure responsibility. Can’t Get You Out of My Head continues in this tradition. All of this is a long-winded—yet by no means exhaustive—way of saying, again, that we need to get Adam Curtis out of our heads.

see Deep Fake Politics (Part 1): Getting Adam Curtis Out of Your Head

see Deep Fake Politics (Part 2): The Prankster, the Prosecutor, and the Para-political

And listen now to:

Deep Fake Politics—Historiography of the Cold War, the Clandestine State, and Political Economy of US Hegemony with Aaron Good

[1] Ernst Fraenkel, The Dual State: A Contribution to the Study of Dictatorship (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1941).

[2] Gerhard Sporl, “The Leo-Conservatives,” Spiegel International, April 8, 2003.

[3] Aaron Good, “American Exception: Hegemony and the Dissimulation of the State,” Administration and Society 50, no. 1 (2018): pp. 4–29.

[4] Carl Schmitt, Political Theology, trans. George Schwab (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1985), p. 5.

[5] Schmitt, Political Theology, p. 6.

[6] Schmitt, Political Theology, p. 7.

[7] The fact that this is a controversial statement is an interesting data point for understanding the sociology of Western historiography, especially in light of events such as the Cold War Gladio bombings in Europe. For a comprehensive exploration of Nazi culpability, see: Benjamin Carter Hett, Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation into the Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[8] Aaron Good, “American Exception: Hegemony and the Tripartite State,” (Temple University, 2020), pp. 235–6.

[9] Good, “American Exception: Hegemony and the Tripartite State,” (Temple University, 2020), p. 236.

[10] Aaron Good, “American Exception: Hegemony and the Tripartite State,” (Temple University, 2020).

[11] Sporl, “The Leo-Conservatives.”

[12] For examples, see: Harold D . Lasswell, “The Garrison State,” The American Journal of Sociology 46, no. 4 (1941): pp. 455–68; Peter Dale Scott, The Road to 9/11: Wealth, Empire, and the Future of America (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007); Sheldon Wolin, Democracy Incorporated: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

[13] Hans Morgenthau, “A State of Insecurity,” The New Republic 132, no. 16 (1955), p. 12.

[14] Fraenkel, The Dual State: A Contribution to the Study of Dictatorship.

[15] Ola Tunander, “Democratic State vs. Deep State: Approaching the Dual State of the West,” in Government of the Shadows: Parapolitics and Criminal Sovereignty, ed. Eric Wilson (New York, NY: Pluto Press, 2009), pp. 56–722.

[16] He uses the term dual state, but it is bears much in common with scholarly works on the deep state produced in works like Tunander, “Democratic State vs. Deep State: Approaching the Dual State of the West”; Scott, The Road to 9/11: Wealth, Empire, and the Future of America; and Good, “American Exception: Hegemony and the Dissimulation of the State.”

[17] That imperialist project, as you may recall, was near and dear to Kerry Thornley’s heart. JFK’s opposition to the operation further fueled Thornley’s hatred of the president.

[18] Guido Giacomo Preparata, Conjuring Hitler: How Britain and America Made the Third Reich (New York, NY: Pluto Press, 2005), pp. 20–21.

[19] Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick, The Untold History of the United States, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Gallery Books, 2019).

[20] Alfred W. McCoy, In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of US Global Power (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2017).

[21] Henry Luce, “The American Century,” Life, February 17, 1941.

[22] Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1997), p. 40.

[23] Glenn Greenwald, “Wes Clark and the Neocon Dream,” Salon, November 26, 2011.

[24] Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson, “Op-Ed: Russia’s got a point: The U.S. broke a NATO promise,” LA Times, May 30, 2016.

[25] Robert Parry, “The Ukraine Mess That Nuland Made,” Truthout, July 15, 2015.

[26] Michael Parenti, Against Empire (San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books, 1995), p. 1.

[27] John F. Kennedy, “Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy in the Senate,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum (Washington D.C.), July 2, 1957.