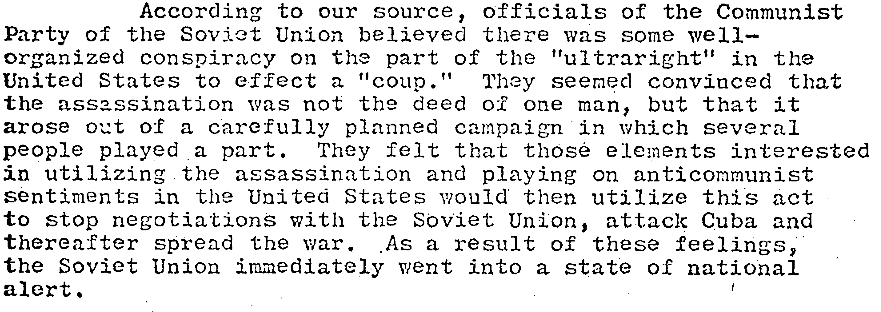

John Newman has just released the third part of his series on the murder of John F. Kennedy. Titled Into the Storm, we are running an excerpt from it on our site, while linking to another excerpt. This review deals with the second volume, Countdown to Darkness. It is indefinite as to how long this series will be. I originally heard it would be a five-volume set. But now I have heard from other sources it may be six. (I will comment on this length factor later.)

Countdown to Darkness assesses several subjects. Some of these the author deals with well. Some of his treatments disappoint. The point is the book is wide-ranging in scope, as I imagine the rest of the series will be. It does not just deal with topics relating to the JFK murder. There are subjects dealt with that are more in keeping with a history of Kennedy’s presidency. Therefore, the book is broad based.

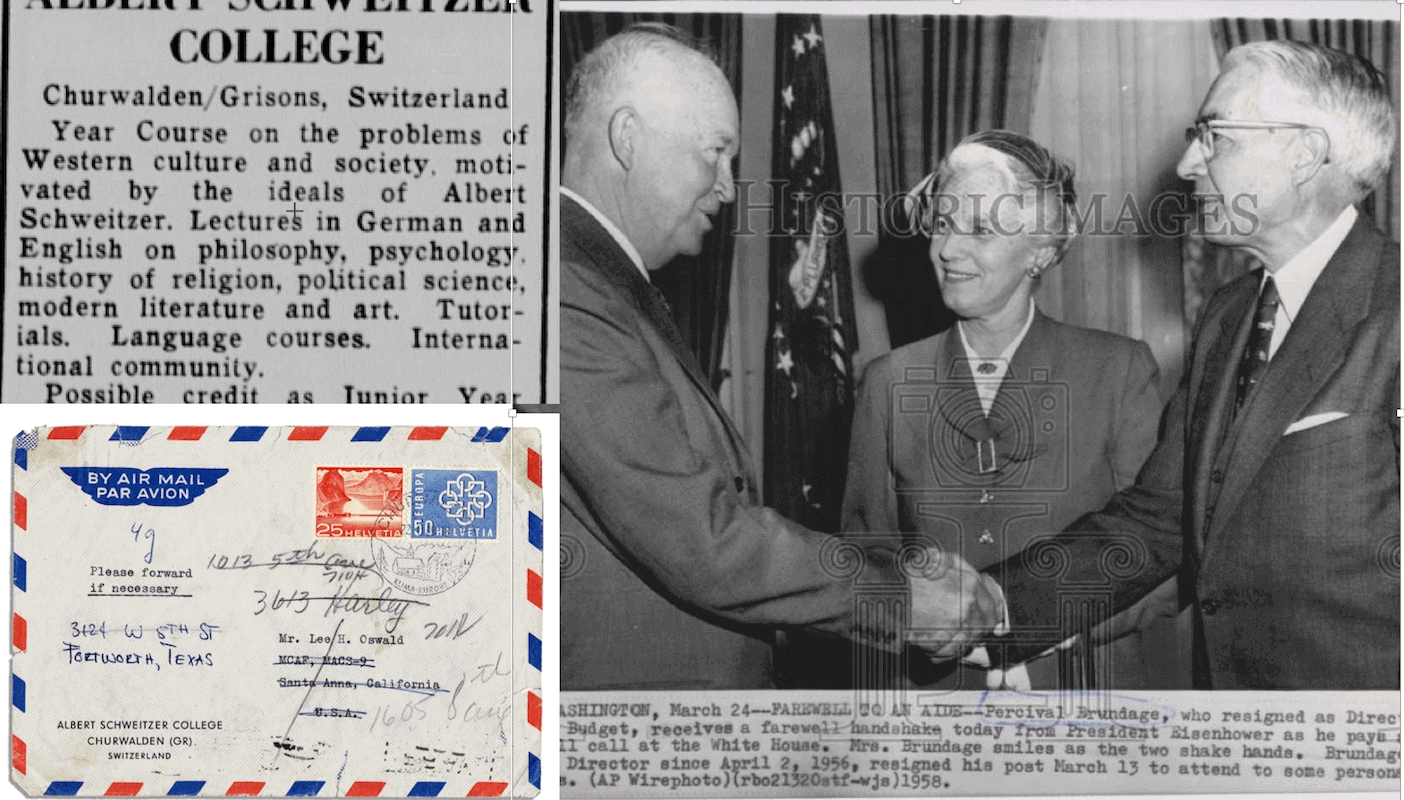

Countdown to Darkness begins with the peculiar arrangement surrounding the dissemination of Oswald’s file at CIA. This valuable information is a combination of Newman’s examination of the file traffic, plus insights gained by the estimable British researcher Malcolm Blunt. Those insights were achieved through Blunt’s discussions with the late CIA officer Tennent Bagley. In this analysis, Newman repeats his previous thesis that although the first Oswald files went to the Office of Security, they should have gone to the Soviet Russia Division. (p. 3; all references to the e-book version) He expands on this by saying this pattern appears to have been prearranged. The mail distribution form was altered in advance to make this happen. (p. 2) One effect of this closed off routing was that there was little chatter about Oswald’s implied threat to surrender radar secrets. When Blunt talked to Bagley, Malcolm told him about this dissemination pattern. Bagley asked Blunt if he thought this was done wittingly. When Malcolm said he was not sure, the CIA officer replied he should be—because it was set up that way in advance. Blunt said that this disclosure was “a significant departure from Bagley’s normal cautious phrasings.” (p. 30)

II

From here, the book turns to Cuba and President Dwight Eisenhower’s intent to overthrow Castro. CIA Director Allen Dulles with Vice President Richard Nixon first discussed this idea in 1959. The initial planning on the project was handed to J. C. King and Richard Bissell; the former was Chief of the Western Hemisphere, the latter was Director of Plans. (p. 32) The author traces the familiar story of how the original idea—to integrate a guerilla force onto the island to hook up with the resistance—began to evolve into something larger in January of 1960. This was coupled with the Allen-Dulles-inspired embargo, which extended to include weapons from England. This was meant to force Castro to go to the Eastern Bloc and the USSR for arms. (pp. 36-37) Dulles also wanted to sabotage the sugar crop, but Eisenhower turned that request down.

Bissell turned over the architecture of the overthrow plan to CIA veteran officer Jake Esterline. (p. 48) Esterline had been a deputy on the 1954 task force in the coup against Arbenz in Guatemala. Like David Talbot before him, the author points out the fact that warnings about the overall design problems, and how the objective differed from Guatemala, were deep-sixed. (p. 55) By March of 1960, Eisenhower started talking about a different approach, a strike force type invasion. The president wanted OAS support for this plan. And here the author introduces something new to the reviewer: his concept of Eisenhower’s Triple Play. That is, in order to achieve such outside support, the White House and CIA would rid Latin America of a thorn in its side, namely, the bloodthirsty dictator of the Dominican Republic, Rafael Trujillo. (p. 90) This will later expand into an attempt to also get NATO behind the overthrow. Hence, Ike’s Triple Play will include the assassination of Patrice Lumumba of Congo.

One of the contingencies upon which Eisenhower based his overthrow of Castro was the establishment of a government in exile. This consisted of the banding together of several individual groups of Cuban exiles under an umbrella called the Revolutionary Democratic Front, or FRD. (p. 127) This endeavor ended up being quite difficult, for two reasons. First, some prominent exile members, like Tony Varona, did not want to join. Second, a principal officer involved for the CIA, Gerry Droller (real name Frank Bender), had rather poor organizational skills. The author gives us more than one example of this trait. (pp. 129-32)

As the operation morphed from a guerilla-type incursion into a brigade invasion concept, more managers were grafted onto the project. The author first names Henry Hecksher. (p. 140) Hecksher worked with David Phillips on the Arbenz overthrow, then went to Laos, and then was assigned to Howard Hunt’s favorite exile, Manuel Artime, in 1963-64. (pp. 142-44) Another person named by the author as part of this expansion is Carl Jenkins.(p. 147) Jenkins worked at the Retalhuleu military base in Guatemala. A base was also set up in Nicaragua and some of the Alabama National Guard pilots were enlisted.

As the brigade concept was escalating, false information was entered into the information flow. Undersecretary of State Douglas Dillon said only 40% of the Cuban populace would end up supporting Castro. (p. 170) Which, to put it mildly, turned out to be almost ludicrously wrong. Castro now began to import a flow of Eastern Bloc arms through Czechoslovakia. (p. 171) As this occurred, Eisenhower, through Dulles, began to activate the Trujillo aspect of the Triple Play. This appears to have been set in motion between February and April of 1960. (p. 172)

When Castro began to seize oil companies like Texaco, Esso and Shell, Vice President Nixon began to urge Eisenhower into action. He recommended “strong positive action” to avoid becoming labeled, “uncle Sucker” throughout the world. (p. 174) National Security Advisor Gordon Gray said much the same thing: “… the U.S. has taken publicly about all it can afford to take from the Castro government ….” (p. 174)

On July 9, 1960, Nikita Khrushchev threatened the USA with ICBMs over Cuba. Eisenhower replied that America would not be intimidated by these threats. (p. 176) The author mentions that at this time there was an attempt by the Agency to solicit a Cuban pilot to assassinate Raul Castro. Newman scores author Evan Thomas for distorting this as the pilot’s idea, when the impetus was clearly from the CIA. (p. 182) General Robert Cushman, working on the staff of Richard Nixon, urged Howard Hunt to use as much skullduggery as possible to get rid of Castro. (pp. 184-85)

But as the Inspector General report by Lyman Kirkpatrick later revealed, the attempt to arm and supply the dissidents on the island was not working. In fact, at times, it was counter-productive, since Castro’s forces would recover the supplies and arms. As the threat grew, Russia sent in more arms to the island: tanks, mortars, cannons. With these advantages Castro began to close in on the resistance. And this was another reason the original guerilla plan was modified into a brigade-sized invasion. (p. 185)

III

We now come to what this reviewer feels is probably the highlight of the first two books in the series: the author’s work on the assassination of Patrice Lumumba of the Congo. Newman devotes four chapters to this subject. In my opinion the result is one of the best medium-length treatments of the Congo crisis I have read. As noted above, Eisenhower felt that by getting involved in Belgium’s colonial problems, this would encourage NATO allies to stand by him in his attempt to overthrow Castro. After all, the NATO alliance began in 1948 with the Brussels Treaty.

As early as May 5, 1960 Allen Dulles was aware that Belgium was attempting to set up a breakaway state in the Congo called Katanga. This was two months before the ceremony formalizing the Belgian withdrawal from its African colony. (p. 153) Katanga was the richest region in Congo, and perhaps one of the richest small geographical areas in the world. If the Katanga secession were successful, it would do much to benefit Belgium and its covert ally England, at the same time that it would damage the economy of the new state of Congo.

Dulles was predisposed to favor Belgium because of his prior career as a corporate lawyer with the global New York law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell. That firm represented many companies that benefited from low wage conditions in the Third World. Therefore Dulles and his deputy Charles Cabell began to smear independence leader Patrice Lumumba at National Security meetings in advance of his assuming power. Combined with the fact that the Belgian departure was not total, this pitted Lumumba against both the former imperialists and the growing malignancy of the USA. (p. 154)

Lumumba’s stewardship was not just hurt by the Katanga secession, but also by the fact that Belgium had removed Congo’s gold reserves and placed them in Brussels prior to independence being declared. (p. 155) With little cash on hand, Lumumba’s army mutinied and spun out of control. This created the pretext for Belgium to send in paratroopers. The Belgians now began to fire on the Congolese. On July 11th, Katanga declared itself a separate state. By July 13, 1960, two weeks after independence, the Belgians occupied the Leopoldville airport and Lumumba decided to break relations with Brussels. The next day the United Nations, under Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold, passed a resolution to send troops to Congo. In the meantime Allen Dulles was working overtime to tell anyone on the National Security Council and in the White House that Lumumba would tie Congo to Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, Castro and the Communist Bloc. (pp. 162-63)

This tactic worked. When Lumumba arrived in Washington to ask for supplies, loans and aid in expelling the Belgians, Eisenhower was not on hand to greet him. Instead, Lumumba talked to Secretary of State Christian Herter and Under Secretary Douglas Dillon. They lied to him by saying they were working through Hammarskjold. (p. 220) This left Lumumba little choice but to ask Russia for supplies. The USSR sent him transport planes and technicians. (p. 222)

When the Russians sent Lumumba the military aid, it sealed his fate. On August 18, 1960 Leopoldville station chief Larry Devlin sent a cable that was drawn in the most hyperbolic terms imaginable. Devlin told CIA HQ that Congo was now experiencing a classic communist takeover, and there was little time to avoid another Cuba. (p. 223) This was clearly meant as a provocation. It worked. On the day this cable arrived, Eisenhower instructed Dulles to begin termination efforts against Lumumba. This was kept out of the meeting record. It was not revealed until the investigations of the Church Committee. The recording secretary to the meeting, Robert Johnson, told the committee that it was too sensitive to be included in the minutes. (p. 227)

The plot began the next day. Director of Plans Dick Bissell told Devlin to begin action to replace Lumumba with a pro-Western leader. On August 26, Allen Dulles sent an assassination order to Devlin that authorized a budget of $100,000 to terminate Lumumba, the equivalent of close to a million dollars today. (p. 236) Bissell now called in the head of the Africa Division, Bronson Tweedy, and they began to assemble a list of assets they could employ in order to do the job. (p. 246) One of these was the infamous Dr. Sydney Gottlieb, who began to prepare poisons for use in the assassination. Devlin also got President Joseph Kasavubu to remove Lumumba from his position as prime minister. At this point Hammarskjold sent his own emissary, Rajeshwar Dayal, to Congo to protect Lumumba.

This was necessary because, in addition to Gottlieb, Devlin now bribed the chief of the army, Josef Mobutu, to also assassinate Lumumba. (p. 265) At around this time, two CIA-hired killers, codenamed QJ WIN and WI ROGUE, both arrived in Leopoldville. Not knowing each other, they both stayed at the same hotel. Gottlieb then arrived in Congo. (p. 268) In September of 1960, with a multiplicity of lethal assets on hand, Tweedy now cabled Devlin to produce an outline of how he planned on terminating Lumumba.

The use of the two codenamed assassins in Congo marks the beginning of the ZR/Rifle program. This was the CIA’s mechanism for exterminating foreign leaders. It began under Eisenhower in September of 1960. (p. 280) The next month it was taken over by CIA officer William Harvey. ZR/Rifle was sort of like the reverse side of Staff D, which was a burglary program to break into embassies and steal codebooks. Harvey and his assistant Justin O’Donnell recruited safe crackers, burglars and document forgers for that part of the program. (pp. 284-85) When Harvey testified before the Church Committee, he lied about the use of ZR/Rifle in the Lumumba case. He was fully aware of what the two men were doing in Congo. (p. 290)

Mobutu now tried to arrest Lumumba, but Dayal blocked the attempt. Three things happened in November of 1960 that penned the final chapter. CIA officer Justin O’Donnell arrived in Congo to supervise the endgame. John Kennedy, who the CIA knew sympathized with Lumumba, was elected president. And third, America and England cooperated in seating Kasavubu’s delegation at the United Nations. This last event provoked Lumumba into escaping from Dayal’s house arrest. O’Donnell had decided that the CIA should not actually murder Lumumba. But they would help his enemies do the deed. Therefore, Devlin cooperated with Mobutu to cut off possible escape routes to Lumumba’s base in Stanleyville. He was captured, imprisoned and transferred to Elizabethville in Katanga. (p. 295) Lumumba was executed by firing squad and his body was soaked in sulphuric acid. When the acid ran out, his corpse was incinerated. (p. 296) Thus was the sorry end of the first democratically elected leader of an independent country in sub-Saharan Africa.

As I said, for me, this section on Lumumba is the highlight of the first two volumes.

IV

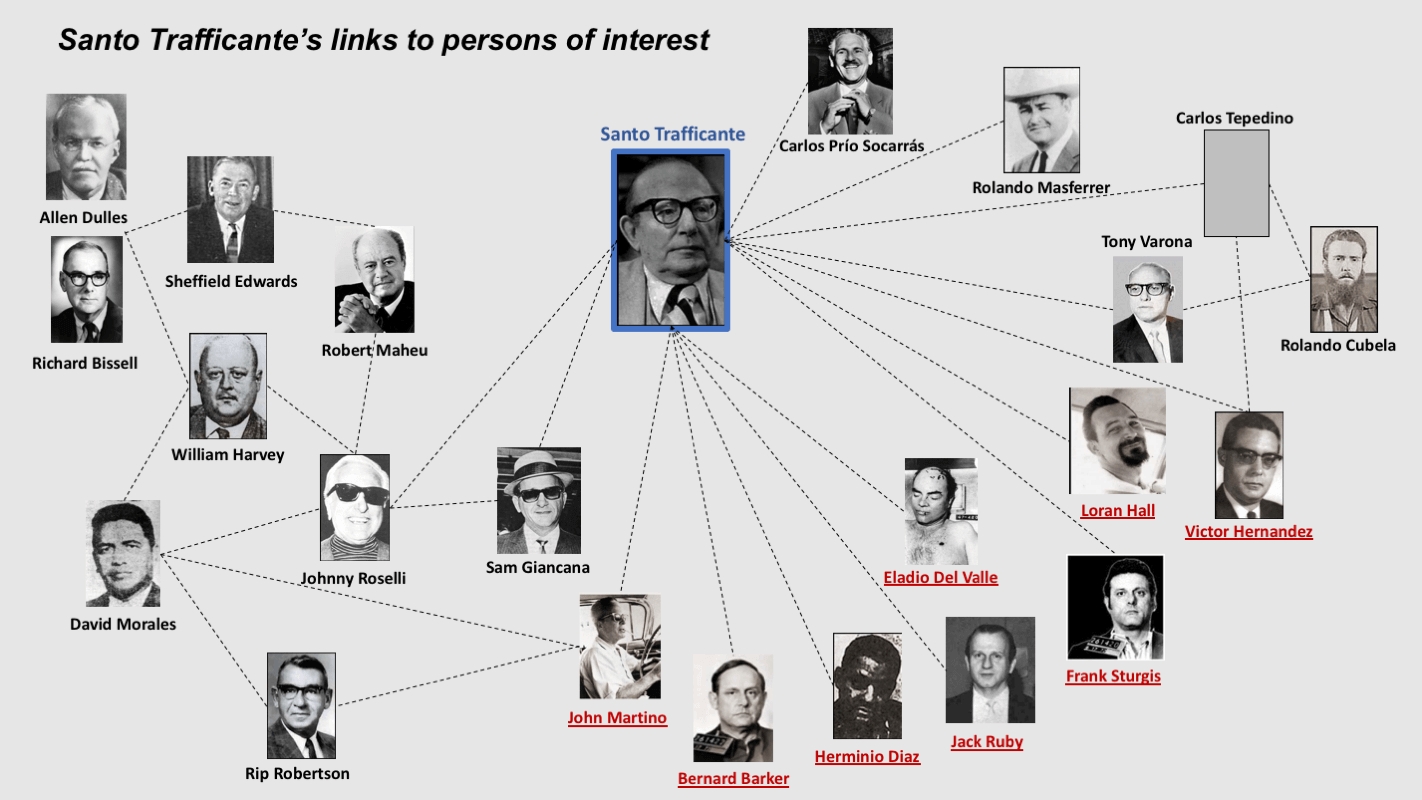

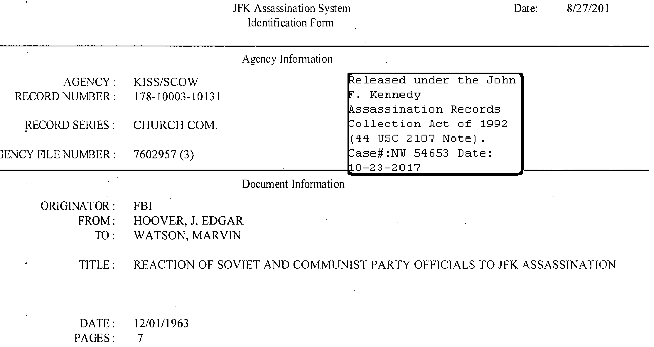

Another topic that the author spends significant time on is the CIA/Mafia plots to kill Castro. The author traces this idea from Allen Dulles to Dick Bissell. He believes that Eisenhower gave his tacit approval to the plots. He also believes that Bissell dissembled in his testimony on how the plots were hatched, and he mounts several lines of evidence to demonstrate this. (p. 327) Bissell dissembled in order to conceal the fact that it was he who approved of giving the assignment to the Mafia through CIA asset Robert Maheu. By mid-August of 1960, the CIA’s Technical Services Division was at work manufacturing toxins to place in Castro’s cigars.

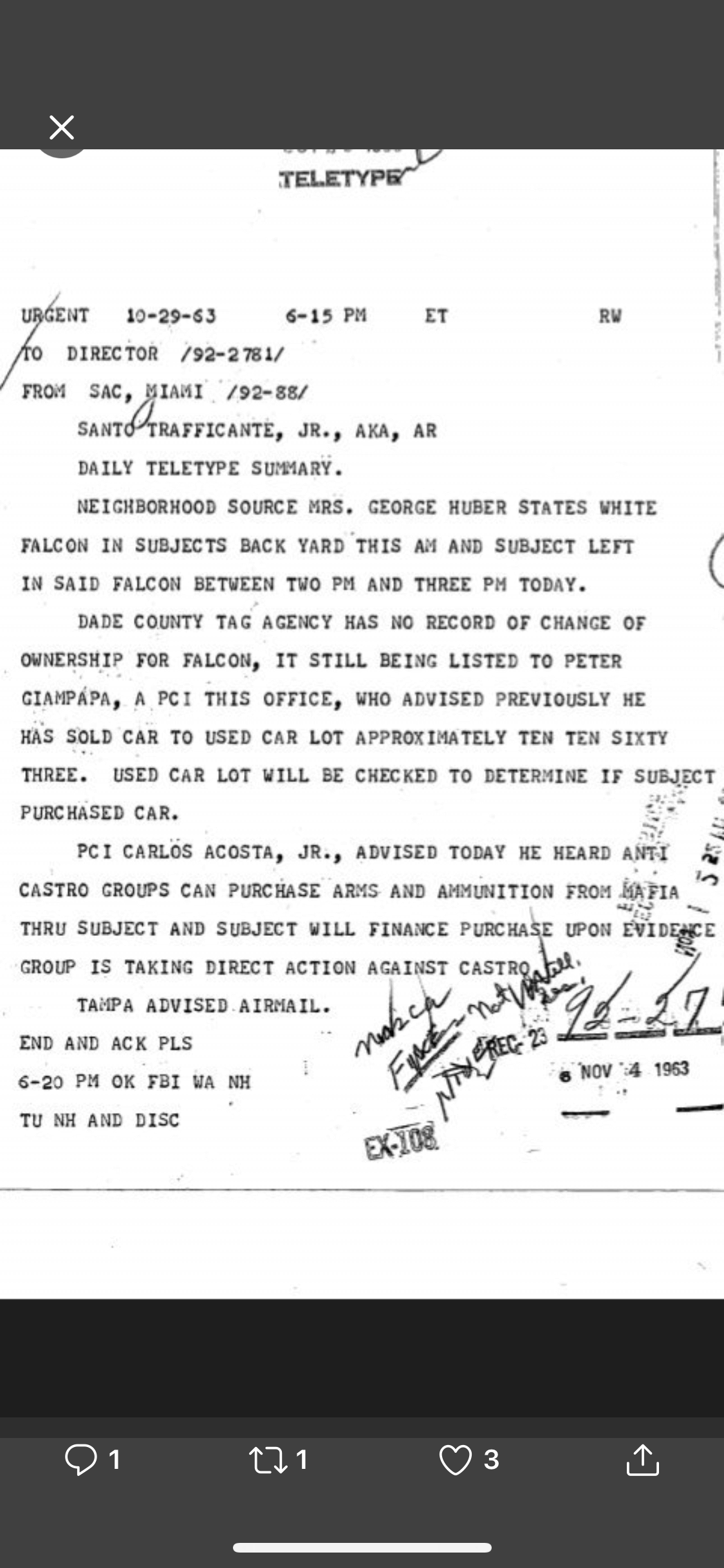

Maheu offered gangster Johnny Roselli $150, 000 to kill Castro. (p. 331) Both Allen Dulles and his deputy Charles Cabell were briefed on this overture in late August by Chief of Security Sheffield Edwards, who was part of the Mafia outreach program. Meetings were arranged with Roselli in Beverly Hills and New York City. Maheu and CIA support officer Jim O’Connell masqueraded as American businessmen who wanted to protect their interests by getting rid of Castro. But Maheu eventually told Roselli that O’Connell was CIA. Therefore, the veneer of plausible deniability was lost. (p. 333) Roselli now began to recruit Cubans in Florida for the murder assignment. He also arranged a meeting in Miami for Maheu to be introduced to Sam Giancana and Santo Trafficante, respectively the Mafia dons for Chicago and Tampa. When this occurred the author writes that, because of the reputations and history of these two men, the plots and the association should have been reassessed and approval cancelled. They were not.

They should have been. Because the recruitment of Giancana was a huge liability. Not just because of his history of being a hit man; but also because of his inability to keep a secret. Feeling emboldened, since he was now in the arms of the government, he bragged about his role in the plots to at least two people. From there the word spread to others, including singer Phyllis McGuire. Giancana revealed both the mechanism of death—poison pills—and the projected date of the assassination—November of 1960. (p. 334-35) Through his network of informants, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover found out about Giancana’s dangerous chatter. But Hoover did not know that the CIA had put him up to it. The Director told Bissell about it, but Bissell did not inform Hoover about his role as recruiter.

Maheu now arranged to have McGuire’s room wired for sound in Las Vegas. This was done for two reasons. First, to see if she was talking about the plots; and second, as a favor to Giancana, who suspected she was cheating on him with comedian Dan Rowan. The police discovered this illegal bugging. In addition to the security problem, this all had disturbing repercussions when Attorney General Robert Kennedy began his crusade against organized crime in 1961. (p. 336)

Along with these assassination plots, on November 3, 1960, National Security Officer Gordon Gray came up with the idea of using Cuban exiles dressed as Castro soldiers to stage an attack on Guantanamo Bay as a pretext for an invasion. (p. 346) As the author suggests, the very fact that the murder plots and this false flag operation were contemplated show that those involved in managing the strike force invasion understood that its chances for success were low. (pp. 345-46) To further that miasma of doubt, at this same meeting, a question was asked about “direct positive action” against Fidel, his brother Raul and Che Guevara.

There was good reason for both the doubt and the fallback positions, because about two weeks later, CIA circulated a memo admitting that there would not be any significant uprisings on the island due to any incursion, and also that the idea of securing an air strip on the island was also not possible unless the Pentagon was part of the attempt. (p. 348) This memo was not shared with the incoming President Kennedy. The author deigns that it was not shared because the internal uprising myth was used to manipulate Kennedy into going along with the operation. It thus became part and parcel with the new “brigade strike force” concept. (pp. 352-53)

On January 2, 1961, Castro broke relations with the United States. The favor was returned two days later. These actions caused the training of the exiles in Central America to be expanded, and also for the action against Trujillo to be accelerated. (p. 355) On January 4th, Chief of the CIA paramilitary section wrote a memo to one of the operation’s designers, Jake Esterline. The memo said the invasion would be stuck on the beach unless an uprising took place or there was overt military action by the USA. (p. 355) As the author notes, this is another indication that the people involved at the ground level understood that, left to its own devices, the prospects for the invasion were fey. Hawkins added that Castro’s military forces were growing. They would soon include featured tanks, artillery, heavy mortars and anti-aircraft batteries. Given those facts, Hawkins warned that:

Castro is making rapid progress in establishing a communist-style police state that will be difficult to unseat by any means short of overt intervention by US military forces. (p. 356, Newman’s italics)

Since Bissell was a supervisor of both the assassination plots and the invasion, one wonders if he was banking on the murder of Castro to bail out what looked like an upcoming failure on the beach. In fact, as the author notes, at NSC meetings of January 12 and also January 19, the idea of overt intervention was brought up again. What made the time factor even more pressing was that the CIA had information that the shiploads of these munitions would reach Cuba in mid-March and continue with daily arrivals after that. This is why Hawkins urged that the invasion be launched in late February and no later than March 1. (p. 356) This would not happen, since Kennedy rejected the first proposal for the operation, namely the Trinidad landing site.

V

Kennedy had two meetings on the subject during his first week in office. At neither did he appear enthusiastic about it. On February 3, 1961 the Joint Chiefs wrote a ten-page report in which they viewed the plan favorably. This was something of a reversal from their previous assessments. But they cautioned that the plan was reliant on indigenous support from the island, meaning defections from Castro. They foresaw that if the force retreated to the mountains it might need overt American intervention. But even with these reservations, the executive summary at the end was positive. (pp. 363-64) Newman comments that one way to explain this reversal is that the Joint Chiefs felt that if the CIA plan failed, they would be called in to save the day and collect the glory.

Kennedy now chimed in with his reservations about having the operation look too much like a World War II amphibious assault. He asked if it were possible to configure it more like a guerilla operation. (p. 366) This was a harbinger of what was to come from the president, who clearly never liked the operation in the first place. Knowing this, those pushing the plan tried to convince Kennedy that the strike force would ignite a rebellion on the island, even though they knew that such was not the case. (p. 383) Newman writes that this manipulation was done so that JFK would not cancel the operation—the gamble being that he would feel obligated to send in the Pentagon once he saw the invasion faltering. This hidden agenda to the Bay of Pigs episode was pretty well established in 2008 by Jim Douglass in his fine book JFK and the Unspeakable.

At White House insistence, the location of the plan was moved away from Trinidad, 170 miles southeast of Havana, at the foothills of the Escambray Mountains. (p. 389) The reason for the switch was that Trinidad had a population of about 26,000 people. This decreased the odds of surprise and opened up the possibility of civilian casualties. Trinidad also did not have a proper length airfield for B-26 bombers. For these reasons, the locale was shifted to the Bahia de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs), east of the Zapata Peninsula. The CIA now went to work tailoring a plan for the new location.

There was a serious problem with these delays. The longer it took to launch the operation, the more time Castro had to import weaponry from the USSR. The arms supplies began arriving in earnest on March 15. After that, one or two ships would unload per day. (p. 392) At this point, both Esterline and Hawkins wanted to leave the project.

As the author notes, another important alteration was that the air cover and assaults were gradually whittled down in frequency and scope. This was owed to the reluctance of Kennedy and Secretary of State Dean Rusk to reveal the hand of American involvement. The first Hawkins-Esterline plan featured well over one hundred sorties in five different waves. (p. 390) When Kennedy asked Bissell how long it would take for the invasion force to work its way off the beachhead, he replied about ten days. In light of what actually happened, this was absurd, since no beachhead was ever established to break out of.

As late as an April 4 meeting, Kennedy was still trying to argue for an infiltration plan. Inserting groups of 200-250 men and developing a build-up from there. Kennedy was trying to make it appear less as an invasion and more as an internal uprising. The CIA replied that this would only alert Castro, and each group would then be eliminated. (p. 394) The next day Kennedy asked assistant Arthur Schlesinger what he thought of the project. Schlesinger said he opposed it. He felt that Castro was too entrenched to be displaced by a single landing force. And if the landing did not cause uprisings, logic would dictate American intervention. The author notes the late date of this cogent observation: ten days before the launch from Central America. Newman also notes the fact that no one from the Pentagon pointed this out at the meeting; just as there was no real discussion of the air cover plan. Making it all the worse: Kennedy had instructed Bissell to tell the brigade leaders that no American military forces would participate or support the invasion in any way. (p. 393)

But further, Kennedy drastically cut back on the amount of air sorties he would allow. And this is what had Esterline and Hawkins ready to depart the project. (p. 396) As stated previously, they insisted there had to be five waves of air strikes and over 100 individual sorties. Kennedy and Rusk opposed this aspect. Newman blames the Joint Chiefs for not stepping in and pointing out the difference between the Esterline/Hawkins design and what was happening to it. The author, citing Bissell, now says that what was left was the strikes scheduled the day before, and also the D-Day air strikes. Newman, citing Bissell, says that Kennedy then cancelled the latter the day before they were scheduled. (pp. 399-400) I was surprised to see the author adopt this interpretation of the controversial issue. This is a point of dispute which I will delve into later.

The invasion was an utter failure and the battle was decided within the first 24 hours. There was no surprise. There were no defections. And in the first 24 hours there was no Allen Dulles. Bissell had encouraged him to keep a speaking engagement in Puerto Rico. Dulles did keep it. Newman makes an interesting observation about this. Dulles kept the engagement to give the appearance that the operation was really Bissell’s. Therefore, after the Navy saved the day, he should be forced to resign while Dulles kept his job. (p. 402)

What no one thought would happen did happen at midnight on April 18. Joint Chiefs Chairman Lyman Lemnitzer and Navy Chief Arleigh Burke tried to convince the president that he must intervene. (p. 403) Kennedy turned down this last attempt to get him to commit American power into the failed beachhead. Dulles’ plan to overthrow Castro and save his position had failed.

Burke was relieved of duty in August of 1961. Later in the year, Dulles, Bissell and Cabell were also terminated. Lyman Lemnitzer was moved to NATO command and replaced by General Maxwell Taylor. In a conclusion, the author writes that after doing the research for this book, he has now downgraded his opinion about Eisenhower as a president. (pp. 404-405) After doing my own work on the man, I would have to agree. But I would make this judgment not just on foreign policy but also with civil rights. Eisenhower had some remarkably good circumstances accompanying his presidency; for instance, a growing economy, positive net trade balance in goods and services, a great military advantage over the USSR, and a unified populace behind him. In retrospect, he had a lot of political capital to make some daring decisions with, both abroad and on the domestic scene. For whatever reason, he chose not to. He passed those decisions on to his successor.

VI

I might as well begin the negative criticism with the subject of the Bay of Pigs. As the reader can see from my above synopsis, the author advocates for the stance put forth by Allen Dulles and Howard Hunt in their Fortune magazine article, saying that Kennedy cancelled the D-Day air strikes. (September, 1961, “Cuba: The Record Set Straight”) And that somehow this was the fatal blow delivered to the enterprise. (Newman, p. 400)

I would have thought that by now, this stance would have been discredited. In the penetrating report delivered by CIA Inspector General Lyman Kirkpatrick, he poses the hypothetical: Let us assume that Castro’s air corps had been neutralized. That would have left about 1,500 troops on the beach against tens of thousands of Castro’s regular army, reinforced by a hundred thousand or more men in reserve. And the Russians had been delivering shiploads of artillery, mortars and tanks every day for over a month, the very weapons one uses to stop an amphibious invasion on the ground. (Peter Kornbluh, Bay of Pigs Declassified, pp. 41, 52. This book contains most of the Kirkpatrick Report and its appendixes.) What made this aspect even worse is something Newman barely mentions: the element of surprise. One reason Kennedy moved the operation out of Trinidad is that the area was too populated, which would mitigate against that element. The Zapata peninsula was sparsely populated and the CIA said there was no paramilitary patrol there. This turned out to be false. There was a police force at Playa Giron beach the night of the landing. (Kornbluh, p. 37) They alerted Havana. Castro had his troops, with armor and artillery, on the scene within ten hours. But it’s actually worse than that. Castro had so thoroughly penetrated the operation by his intelligence sources that he knew when the last ship left Guatemala. (Kornbluh, p. 321) Therefore, on high alert, he was literally waiting for the landing. To top if off, the other element that the CIA said would be important to the invasion’s success, mass defections from the populace, was non-existent. In fact, Castro later crowed about how even the small number of people on the scene had backed him against the exiles. (Kornbluh, pp. 321-22) Therefore, with no defections, no surprise, being massively outnumbered, and with mortars, tanks and artillery shelling the force on the beach, as Kirkpatrick wrote: What difference would it have made with or without Castro’s air corps in operation?

But I would further disagree with the author’s presentation. There is today an ample body of evidence that the so-called D-Day air strikes were not actually cancelled. They were contingent on being launched from an airfield on the island, which is one reason the Zapata Peninsula was chosen. Prior to the invasion, the CIA had agreed to this in their March 15th outline of the plan. In fact, they mention the issue three times in that memo. (Kornbluh, pp. 125-27) Further, both the Kirkpatrick Report and the White House’s Taylor Report mention this stipulation. (Kornbluh, p. 262; Michael Morrisey, “Bay of Pigs Revisited”, The Fourth Decade, Vol. 1 No. 2, p. 20) In the latter, the report states that National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy explicitly told CIA Deputy Director Charles Cabell that such would be the case. (p.23)

This speaks to another issue directly related to the alleged cancellation of the D-Day air strikes. Newman says that both Cabell and Bissell went to the office of Dean Rusk and pleaded their case for the strikes. Rusk was against it and he then got Kennedy on the line and he was also against it. This disagrees with both Dan Bohning’s book, The Castro Obsession, and Peter Kornbluh’s fine volume, Bay of Pigs Declassified. Both of those works say that Rusk offered to get Kennedy on the line, but the offer to talk to JFK in person was turned down. (Bohning, p. 48, Kornbluh p. 306) There is a good reason why Cabell would not want to talk to Kennedy about this subject. It comes from an unexpected source, namely Howard Hunt. In his book on the subject, Give Us this Day, he describes being at CIA headquarters monitoring the operation. He writes that Cabell actually stopped the D-Day strikes from lifting off. Cabell did so because he knew this was not part of the final plan! (Hunt, p. 196)

Newman’s source for much of this rather controversial material is Dick Bissell’s memoir, Reflections of a Cold Warrior. To put it mildly, between his role in the CIA/Mafia Castro plots and the Bay of Pigs—and his dissembling about both—one would think that any author would look at what Bissell had to say about those topics with an arched eyebrow. Larry Hancock, who is quite familiar with the Bay of Pigs, actually called Bissell an inveterate liar on the subject. For instance, he kept on lying to Esterline and Hawkins about his meetings with Kennedy and about the cutting down of the air strikes. He also told them that if there was too much cut back, he would abort the project. He did not. (e-mail communication with Hancock, 2/23/19)

If for some reason the author feels all of this information is wrong and Bissell was correct, then he should have at least acknowledged the discrepancy and explained why he felt such was the case.

But probably worse than this are the two chapters Newman devotes to Judith Exner, Sam Giancana and Kennedy. Before I read this book, I would have thought I would have never seen anything like that topic in a book penned by Newman, for the simple reason that he has almost always been circumspect about the sources he uses for his writing. What caused him to drop his guard on this topic is inexplicable to this reviewer. But whatever the reason, he did.

And he dropped it all the way down. He buys into just about everything Exner ever authored. To the point that he actually writes that the Church Committee allowed her to get away with lying to them. But that somehow, some way, she did tell the truth to—of all people—Seymour Hersh for his hatchet job on JFK, The Dark Side of Camelot. (p. 203) And I should add, it is not just Hersh. The author’s sources for these two chapters include people like Tony Summers on both Exner and Frank Sinatra, and Chuck Giancana on Sam Giancana. I don’t know how he missed the likes of Randy Taraborrelli and Sally Bedell Smith.

If one is going to buy Exner’s stories, one has to examine them in order and be complete about the inventory, or relatively so. The first time she ever spoke in public about her affair with JFK was in her book, My Story, published in 1977. That book was co-authored by Ovid Demaris, an experienced crime author who wrote a fawning book about J. Edgar Hoover called The Director. He also co-wrote a book called Jack Ruby, which pretty much takes the stance toward Oswald’s killer that the Warren Commission did. In that work, he also went out of his way to criticize the Warren Commission critics, like Mark Lane. So right from the beginning, one could at least find evidence that Exner was being used as a vehicle.

My Story was 300 pages long. Demaris was anti-JFK, and he made this clear in his own introduction. If Exner had anything significant to say beyond her Church Committee testimony, she had the opportunity and, in Demaris, the correct author to do it with. She did not. But eleven years later, she did. In a February 29, 1988 cover story for People magazine, Exner was now billed as “the link between JFK and the Mob.”

What did that title signify? Exner was now telling America that, since she knew both Giancana and Kennedy, they were using her as a messenger service for things like buying elections and also the CIA/Mafia plots to kill Castro. But this was all done with Exner being unaware of what she was doing. Newman writes that Exner likely first talked about this in 1992 with talk show host Larry King. (Newman, p. 203) The author apparently never looked up this 1988 story. This allows him to miss some important aspects of the Exner saga.

There was another key point in the Exner tales. This came in 1997 with a double-barreled blast from both Liz Smith in Vanity Fair and Hersh in his hatchet job. All one needed to do is compare the installments for an internal analysis to see if they were consistent with each other. One easily finds out they are not. For instance, in 1977 Exner said the idea that she had an abortion was a lie spread about her by the FBI. She denies it in the most extreme terms. She actually said she wanted to kill the agent for slandering her. (The Assassinations, edited by James DiEugenio and Lisa Pease, p. 336) But in 1997, she now said she did have an abortion and beyond that, it was JFK who impregnated her. Major revisions like that should raise serious doubts in anyone’s mind about Exner and how she was being used.

But that’s not all. For People magazine, Exner said she was not cognizant of her role as a message carrier. She never bothered reading any of the messages between Giancana and Kennedy, or opening any of the containers. But as Michael O’Brien later wrote, this was contradicted in 1997 for Smith, to whom she said that Kennedy showed her what was in one of the large envelopes. Supposedly it was $250,000. Somehow, in 1983, she forgot about being shown that much money. (Washington Monthly, December 1999, p. 39)

There is another whopper in this trail of horse dung. In 1992, when asked by Larry King if Bobby Kennedy had anything to do with this message-carrying service or if she had any kind of relations with him at all, she said no she did not. Either Exner lost track of all the lies she told, or her handlers didn’t give a damn, because in 1997 this was reversed. Now she said that when she was at the White House having lunch with JFK, Bobby would come by and pinch her on the neck and ask if she was comfortable carrying those messages back and forth to Chicago for them. (Washington Monthly, p. 39)

If Newman had done his homework on this, he would have discovered just how and why the 1983 fantasy version started. Exner knew she could make money off her story. Contrary to what Newman writes, she ended up making hundreds of thousands of dollars selling her tall tales to the anti-Kennedy press. (DiEugenio and Pease, p. 330) She was paid $50,000 to sit down with Kitty Kelley for the People story in 1983. (O’Brien, p. 40)

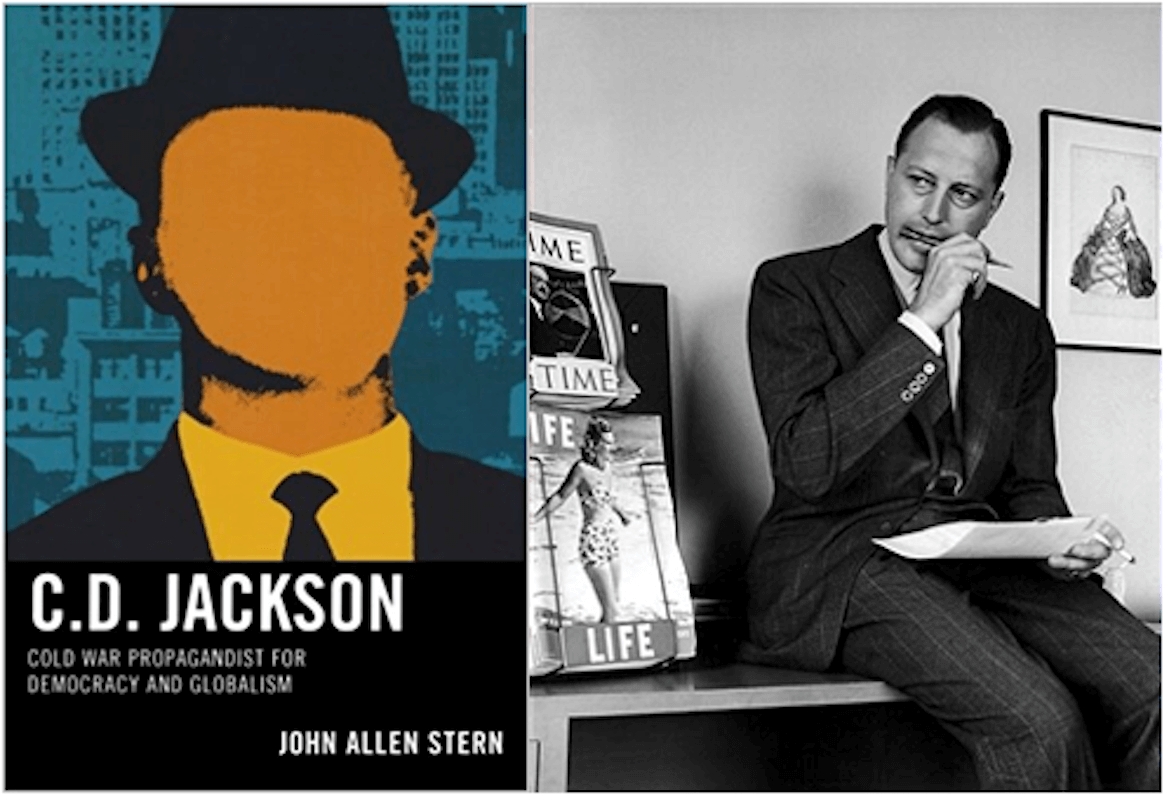

As biographer George Caprozi later revealed, the two did not get along at all. The problem was that Kelley kept on trying to pump Exner for information about Frank Sinatra. She was preparing one of her biographies about him at the time. Exner did not like this and so the two fought like cats and dogs. Nothing productive came out of the meetings. Since they had to pay both women, the editors decided that they themselves would pen the story. (DiEugenio and Pease, p. 334) I should not have to ask Newman, or anyone reading this review, who owns People magazine. The purview of the cover story would come under the aegis of Time-Life. The people who hid the Zapruder film for eleven years; who edited the stills from the film so as not to reveal the head snap; the same people who, on February 21, 1964, placed a dubious photo of Oswald on their cover with the alleged weapons he used to kill Officer Tippit and JFK. In 1983, the time of the story’s publication, the principals were all dead: Sam Giancana, John Roselli and John F. Kennedy. With Exner bought off, the story was libel-proof.

Finally, to prove that Exner was being used as an anti-Kennedy vehicle, consider the Martin Underwood appendage to the saga. By 1997, Exner had gone hog-wild with her mythology. She now said she was carrying money and messages to Chicago from the White House and she would deliver them to a train station with Giancana waiting for her. This was so silly on its face that Hersh knew he needed a corroborating witness for it. So apparently, with help from Gus Russo, he tried to recruit Martin Underwood to accompany Exner in this film noir scenario. Underwood had worked for Mayor Richard Daley in Chicago and then did some advance work in 1960 for the Kennedy campaign. But the Exner follies now collapsed. Under questioning from the Assassination Records Review Board, Underwood would not go along with the scheme and said he knew nothing about such train travel or Judith Exner. (O’Brien, p. 40; see also “ Who is Gus Russo?”)

I could go on and on. But I think the above is enough to expose Judy Exner for what she was: a lying cuss. Someone who would sell her soul for money and tinsel to the likes of Hersh, Smith and Time-Life. She did not deserve one sentence in this book, let alone two chapters.

Let me make one final overall criticism. I have reviewed parts one and two of the series. Countdown to Darkness ends with the debacle at the Bay of Pigs. That took place in April of 1961. Kennedy had been in office for all of three months. I don’t have to tell the reader how long this series could be if the author keeps up this pace. The overall title of the series is The Assassination of President Kennedy. That is not what the series is really about. The book is really about the Kennedy administration. For instance, Volume 3, Into the Storm, features chapters on the association of the Kennedy administration with Martin Luther King. Unless the author is going to say the Klan killed Kennedy, I fail to see how that fits the overall rubric.

When I was talking about and reviewing Vincent Bugliosi’s elephantine Reclaiming History, I wrote that because something is bigger does not make it better. In my opinion, with an astute and sympathetic editor, these first two volumes could easily have been collapsed into one—with the Exner garbage completely cut. More does not automatically connote quality. Sometimes it’s just more. I had the same complaint about Doug Horne’s five volumes series. Our side does not have to compete with the late Vince Bugliosi to exhibit our knowledge or bona fides. This is a long way of saying that I really hope Newman contains himself, or finds a decent editor who he respects and will listen to. He should stop at five volumes.

There is a saying among actors: Sometimes, less is more.

SEE ALSO:

- Our review of volume 1, Where Angels Tread Lightly

- “Berlin 1961—The Most Dangerous Place on Earth” (excerpt from Chapter 5 of volume 3, Into the Storm)

- “When Fiction is Stranger Than Truth: Veciana and Phillips in Cuba — 1959-1960” (excerpt from Chapter 3 of volume 3, Into the Storm), at WhoWhatWhy

For a long time this site has tried to point out that the Congo struggle was one of the most important, yet underreported, foreign policy episodes that took place during the Kennedy administration. Sloughed off by the likes of MSM toady David Halberstam, it took writers like Jonathan Kwitny and Richard Mahoney to actually understand the huge stakes that were on the table in that conflict, namely European imperialism vs African nationalism. Kennedy had radically revised America’s Congo policy from Dwight Eisenhower to favor the latter. Not knowing he was dead, JFK was trying to support Congo’s democratically elected leader Patrice Lumumba. JFK was also one of the few Western leaders trying to help UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold stop the Europeans from crushing Congo’s newly won independence.

For a long time this site has tried to point out that the Congo struggle was one of the most important, yet underreported, foreign policy episodes that took place during the Kennedy administration. Sloughed off by the likes of MSM toady David Halberstam, it took writers like Jonathan Kwitny and Richard Mahoney to actually understand the huge stakes that were on the table in that conflict, namely European imperialism vs African nationalism. Kennedy had radically revised America’s Congo policy from Dwight Eisenhower to favor the latter. Not knowing he was dead, JFK was trying to support Congo’s democratically elected leader Patrice Lumumba. JFK was also one of the few Western leaders trying to help UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold stop the Europeans from crushing Congo’s newly won independence.