The Deep State Assassination of Martin Luther King

by John Avery Emison

Excerpt From Chapter 7

Battle’s Blunder

Battle’s questioning of Ray included seven elements. #1) Battle wanted to establish on the record that Ray’s attorneys had counseled him regarding his rights. #2) He wanted to know if Ray understood his rights. #3) He wanted to know if Ray knew he was accepting a sentence of 99 years in exchange for a plea of guilty and waiver of the death penalty. #4) Battle wanted to establish that Ray agreed to waive his rights to appeal the sentence, and to waive the right to appeal all the motions that had been ruled against him. #5) Battle attempted to establish that Ray’s guilty plea was entered without any pressure on him to do so, and that it was entirely voluntary, but Ray gave a non-answer answer to this question. #6) Battle attempted to establish a factual basis for the guilty plea, i.e. that Ray actually committed murder. Even in the answer to this question Ray played word games. #7) Finally, Battle attempted to establish that Ray knowingly and understandingly entered his guilty plea.

Battle had no business accepting James Earl Ray’s guilty plea without first exploring why he equivocated on his answer regarding pressure. Battle failed, but his failure to the cause of history was even greater than his failure to the cause of justice.

A guilty plea entered as a result of pressure on the accused is anathema to justice in liberal western society. Accepting a guilty plea from any defendant, who is pressured into it, is an invitation for the police or anyone else to pressure whomever they please. It is an end to the rights of individuals that the Bill of Rights was written to protect.

If involuntary, coerced guilty pleas are acceptable, it means prosecutors can accuse anyone they dislike, of any crime they please, and all the authorities have to do is dial up the pressure until the person breaks and confesses to a crime they did not commit. Since everyone has a breaking point, it gives carte blanche to those who prefer tyranny to justice.

Battle further stumbled with the question he put to Ray about whether he actually murdered Rev. King. Battle’s rambling, legally technical question left the door ajar as to whether Ray murdered Rev. King “under such circumstances that it would make you legally guilty of murder in the first degree under the law as explained to you by your lawyers?”

It is my considered opinion, having interviewed James Earl Ray in person on three occasions and once on the phone, and listening repeatedly to the audio recordings of the sentencing hearing, that if Ray actually understood that question (which is doubtful), he twisted it in his mind to construct an answer that was deliberately confounding, and devilishly teasing. Battle’s question was as obscure to non-lawyers as a schematic drawing of the inside of your computer is to non-engineers. It consisted of a question (did you kill Rev. King?) wrapped inside two other questions (did your action meet the legal definition of murder; and is that the way your lawyers explained it to you?).

Ray seized upon Battle’s use of the term “legally guilty of murder in the first degree,” to answer “yes,” admitting he was “legally” guilty. I believe it was Ray’s way of recognizing that he was cornered and going to receive the legal consequences of the charge of murder without truly admitting that he pulled the trigger or knowingly participated in a murder plot. It was Ray’s way of distinguishing between actual guilt and legal guilt. Ray, in this instance, was more a master of words than Battle. He turned Battle’s semantics around and put his own spin on things.

The failure of Battle to truly explore what was in Ray’s mind about pressure used on him, as well as to understand Ray’s comment that he is “legally” guilty, is compounded by the fact that the questions Battle asked Ray were not only scripted, the whole question and answer session was reduced to writing and virtually rehearsed the previous day. The questioning of Ray in open court was as carefully planned as a NASA space shuttle countdown. Spontaneity was out; robotic conformance to the script was in— and it was Battle who turned out to be the robot.

“On the day before the guilty plea, Ray was shown a written copy of the questions which were to be asked to him by Judge Battle, at the time of the plea. Ray initialed and signed each page of this document to indicate that he had read and approved this document,” according to court pleadings filed by William J. Haynes, Jr. and William Henry Haile of the Tennessee Attorney General’s office. [8]

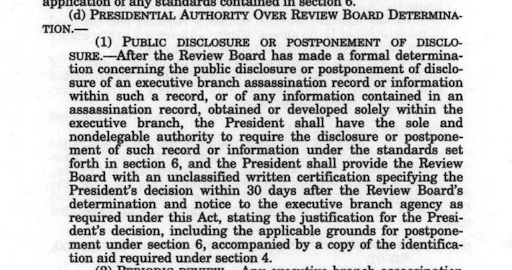

I found the document that Haynes and Haile referred to in the Shelby County archives. It consisted of a petition for waiver of the death penalty in exchange for a plea of guilty; a court Order accepting the guilty plea; and the questions to be posed to Ray by Battle the following day. Ray’s scripted answers were to be a simple “yes” or “no,” and they were already written into the document, a portion of which is displayed in Figure 7-1 (below). Just as Haynes and Haile indicated, Ray and Foreman initialed or signed every page.

On March 10, 1969 Percy Foreman told Battle that he had “prepared the defendant” to follow the script. Battle took his cue, told Ray to stand and began reading his scripted questions as Ray faced him in open court. In all likelihood Battle read from the actual voir dire document that also contained Ray’s scripted answers, which he had signed the previous day.

When Ray deviated from the script on the question about pressure—“Now, what did you say?—and again with his answer about being “legally guilty,” Battle simply continued slogging through the script without ever missing a beat.

One of Ray’s attorneys for much of the 1970s, James H. (Jim) Lesar told me that Battle “blew it in all sorts of ways.” He told me “there was incredible pressure on Ray to plead guilty. There’s no question about that.” Lesar says the pressure came from Ray’s attorney, Percy Foreman. [9]

The entire episode of Battle’s questions and Ray’s answers (as well as the previous day’s rehearsal) was more akin to a dramatic matinee performance than it was to a tribunal of justice. It was a sham and a show—a hollow counterfeit of justice and a cheap knock-off for the truth. It was a charade written and practiced in secret and revealed to the public in open court as if it were the real thing. In reality a great deal of effort had already gone into ensuring that nothing would go wrong once the reporters were in the courtroom. “The show must go on,” as they say in the entertainment business. It certainly did in Memphis that day.

The Alternate Transcript

Doctoring a transcript is a serious offense. Any lawyer who introduces doctored evidence, even unknowingly, is on a fast tract to professional disciplinary action if not a trip to explain it to the grand jury. It is an offense against justice itself as well as the integrity of the court. I have little doubt that the party or parties responsible for doctoring the transcript were working in the background, likely beyond the knowledge of any lawyer who had no need to know the full scope of this operation.

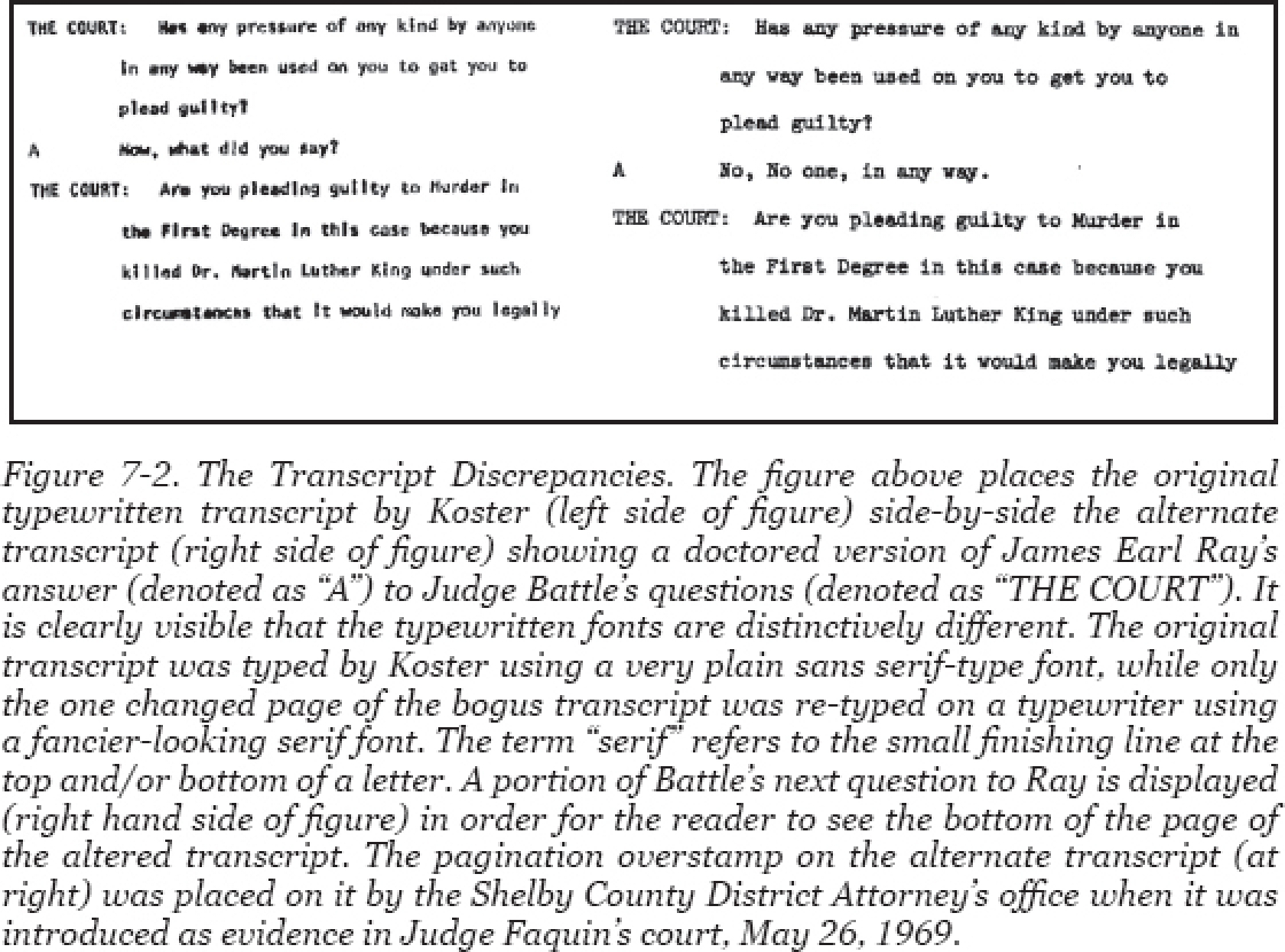

Figure 7-2 (below) illustrates the differences between the two transcripts. The only page that was changed in the altered transcript was obviously typed on a different typewriter. Here is what the doctored transcript recorded:

THE COURT: Has any pressure of any kind by anyone in any way been used on you to get you to plead guilty?

ANSWER: No, No one, in any way.

As previously indicated, the first use of the alternate transcript surfaced in the May 26, 1969 hearing for a new trial in Judge Faquin’s court. It was subsequently used in every court hearing, unchallenged by Ray’s musical-chairs string of lawyers. It was used also in the Federal courts beginning with the case of James Earl Ray v. J. H. Rose, Warden that originated in federal district court in Nashville (Middle district of Tennessee) in 1973. Ray’s attorneys filed a writ of habeas corpus, which is the legal terminology used in the first step in obtaining a federal court review of the sentence imposed on Ray in state court. The writ was denied and the case dismissed without a hearing by Judge L. Clure Morton.

Morton justified his decision by citing specifically from the altered words of the transcript, just as Faquin had done. In fact, Morton said the counterfeit words were “central and determinative” in his decision:

It appears to the (Federal) court that the specific central and determinative issue raised by the massive pleadings in the case is this: Were illicit pressures placed upon the petitioner [Ray] to such an extent that he did not voluntarily enter the plea of guilty? (p. 9)…

The record of the March 10, 1969, proceedings, considered alone, shows that the petitioner [Ray] entered a voluntary, knowing and intelligent plea of guilty (p. 18)…

To summarize this order, the factual allegations of the petitioner… are insufficient to justify a holding that petitioner’s pleas was not voluntary, knowing and intelligent. (p. 19). [10]

Morton had no knowledge that his decision was based on a doctored, false transcript that was entered into evidence in his court by the Tennessee Attorney General’s office, which represented the State of Tennessee in Federal court. Ray’s attorneys not only allowed this poisoned transcript into evidence without objection, they never raised the issue of what Ray did, or did not say to the question about pressure.

Jim Lesar told me he had no recollection about the altered transcript, although he thinks it may be true that there was one. He said Robert Livingston (Ray’s Memphis attorney) “particularly did not trust” the transcript introduced by the State, but has no other recollection about it. [12]

But the damage was done in Judge Morton’s mind. Ray did not give the unequivocal negative answer to the question about pressure that Morton relied on. Morton had no way of knowing it was poisoned evidence.

Ray’s attorneys appealed Morton’s decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. The Sixth Circuit reversed Morton and ordered a full evidentiary hearing. Thereupon, Judge Morton exercised his prerogative and transferred the case to the West district federal court in Memphis where more of the witnesses were located. Judge Robert M. McRae, Jr. conducted an eight-day hearing in Memphis, Oct.-Nov., 1974.

For this hearing in McRae’s court, the bogus transcript was “certified” as “a full complete, true and perfect copy of the transcript of March 10, 1969” by Koster. Koster’s certification is not equivalent to the court’s routine certification of a transcript, which in this case never occurred. Furthermore, we will see below that a “certified” document can be changed before it is filed with the court.

When a court certifies a transcript it allows the lawyers on both sides to review the draft and note any discrepancies, changes, or objections. If these differences cannot be amicably resolved among the lawyers, then the court steps in and may allow oral arguments or written pleadings before deciding. A voice recording can be consulted at the option of the court. None of this ever happened with the Ray sentencing hearing transcript because Judge Battle died. So, a court clerk’s certification falls far short of the mark.

The fact remains someone deliberately changed Ray’s answer and created the alternate transcript in order to deceive the courts and the public, and ensure that Ray would never get a full trial.

Following McRae’s hearing, the Tennessee Attorney General’s (AG) office filed a 71-page memorandum with the court as a summary of its argument that Ray’s case should be dismissed. This document was prepared and signed by two assistants in the AG’s office, Haynes and Haile.

Figure 7-2 (above) may be evidence of the initial effort to create an alternative transcript to Ray’s sentencing hearing. I digitally combined the bottom of page three of the Ray voir dire document and the top of page four for the convenience of getting them into a one-page figure. This figure like the previous two in this chapter is a third or fourth generation document. (All original documents were microfilmed by the Shelby County archives, then digitized, then copied by me in digital form and printed). Percy Foreman’s initials appear in the figure as they do in the real document near the bottom of page three. Ray initialed each page of this document, but his initials are lost on this particular copy. The line across the figure beneath Foreman’s initials is the page break in the actual court document. Ray and Foreman both signed the end of the document on page four.

What’s interesting about this figure is that whomever doctored it in longhand shows the likelihood that he or she was aware of the audio recordings and listened to them, or the person was present in the courtroom March 10 1969 and near enough to Ray to hear what he said. The writer errantly penned, “legally yes” into Ray’s answers in the wrong place. Ray actually spoke the words “legally yes” as previously discussed, but not in response to the “freely, voluntarily, and understandingly” question. Rather, he gave the “legally yes” answer to the question about killing Rev. King. But just like the altered transcript, the doctored document puts the “No, no one in any way” words into Ray’s mouth in the question on pressure—words Ray never uttered.

Arguing in this memorandum that Ray’s plea was entered voluntarily and without undue pressure, Haynes and Haile state the following: “The highest and best evidence of the voluntariness of a plea of guilty are [sic] Ray’s statements at the time the plea is entered… Some of these statements are worth repeating.” Haynes and Haile incorporated the alternate transcript version of Ray’s response to the question about pressure:

THE COURT: Has any pressure of any kind by anyone in any way been used on you to get you to plead guilty?

ANSWER: No, No one, in any way.

The problem with this, as I have repeatedly stated is, this is not what Ray said. He did not utter those words, as I will explain in the following section.

Haynes is deceased but Haile still practices law in Nashville at the writing of this book. When I interviewed him regarding the transcripts he told me, “I don’t remember anything about that.” He said, “I don’t know anything about the transcripts. Nobody ever said anything about the transcripts.”

The memorandum prepared by Haynes and Haile referred to the alternate transcript as “Exhibit 87,” indicating that it was introduced as evidence at McRae’s evidentiary hearing in Memphis. I found this exhibit in the files of the U.S. District Court in Memphis. The page that contains Ray’s altered response is typed on a different typewriter and inserted into the document. The other 86 pages appear to be on the same typewriter. Only the page with the doctored response was changed, and nothing else was changed on the other 86 pages that appear to be duplicates of the original, see again Figure 7-1 (above).

Haile told me he doesn’t recall anything about the source of the transcript used in Federal court: “I wouldn’t know one way or the other.” He added that Ray’s lawyers didn’t complain about its introduction as evidence. “They complained about every other thing. I’m surprised they overlooked that.” He said, “They questioned the authenticity of everything but not this (transcript).” [13]

Koster, on the other hand, firmly recalls the details of his original transcript and knows he did not change anything about it. Even if he had changed a page, he had his own typewriter at his desk and would have retyped it on the same typewriter. Thus, the doctored page did not come from Koster.

As for certifying Exhibit 87, the bogus transcript with the single re-typed page, Koster told me: “Of course, you know, when I certify something and give it to somebody there’s nothing that says they can’t retype it and copy it and make it look like it is part of the original. I’m not saying they did, but that’s what it sounds like.” [14]

Furthermore, both the Blackwell and Koster sworn affidavits prove that the genuine transcript was finalized on March 10, 1969 and unchanged by either of them afterwards. Blackwell’s affidavit says, “After said transcript was distributed to news reporters on said date, I made no changes to, nor did I authorize any changes.” [16]

Haile’s memorandum was apparently convincing because Judge McRae held that Ray’s guilty plea was entered voluntarily and he was “not coerced by impermissible pressure by Foreman.” Ray’s attorneys subpoenaed Foreman to Memphis, but being in Texas he was outside the jurisdiction of this district of federal court. Foreman was deposed by Ray’s attorneys but did not have to appear in court. McRae, using the doctored transcript that was admitted into evidence in his court ruled, “Ray coolly and deliberately entered the (guilty) plea in open court.” [17]

Ray’s lawyers again appealed to the Sixth Circuit. This time, Judge William Ernest Miller, who had twice previously sided with Ray, unexpectedly died of a heart attack after participating in oral arguments. His death left Chief Judge Harry Phillips (a Tennessean) and Judge Anthony J. Celebrezze (former mayor of Cleveland, Ohio) on the court. The court’s ruling was clearly influenced by the bogus transcript in evidence:

As stated, Judge Battle very carefully questioned Ray as to the voluntariness of his plea before it was accepted on March 10, 1969. Ray specifically denied at that time that any one had pressured him to plead guilty. His responses and actions in court reveal that he was fully aware of what was occurring. [18]

The Court’s decision actually quoted Ray’s purported, but bogus response to the question on pressure: “No, no one in any way.”

It was a mistake, but when poisoned evidence is admitted into court it always is. Whoever invented the doctored transcript accomplished precisely what he or she intended: It kept Ray in jail as the embodiment of the murderer of Rev. King. Just as the federal district courts in Nashville and Memphis, the Sixth Circuit never knew Ray’s actual answer and thus, had no way of knowing about Battle’s blunder. The U.S. Supreme Court’s refusal to hear Ray’s petition in 1976 consummated finality.

The altered transcript created in the Shelby County DA’s office was introduced as evidence in Federal district court in Nashville in 1973. We know this because Judge Morton quoted from it in his written decision to deny a Writ of Habeas Corpus. Very little else of the paper trail of that case file remains today either with the district court or the National Archives, so there are no other documents to show who did what. Ray’s attorneys appealed Morton’s denial to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, which reversed Morton and ordered a full evidentiary hearing. Judge Celebrezze of the Sixth Circuit quoted the same altered transcript in a dissenting opinion. Morton quickly transferred the case to Federal court in Memphis. Judge McRae conducted an evidentiary hearing that lasted eight days and denied the writ. The doctored transcript was introduced into evidence at this hearing (Exhibit 87) accompanied by Koster’s certification.

Forensic Enhancement of the Audio Recording— “I Don’t Know What To Say.”

The audio recordings of Ray’s sentencing hearing are available online for anyone to download from the Shelby County archives. The audio quality is very poor for several reasons. The recordings were made with Edison Voicewriter machines that cut vinyl-like records that, in playback mode, ran in the slow 15-rpm range. The technology behind the Voicewriter was 40 years old at the time the recordings were made and “probably was not suited” to the recording of court proceedings due to the fact that it had only one microphone.

The phonograph-type records “obviously had been played so many times that it is a wonder we were able to get anything listenable off of them at all,” according to Vincent Clark of the Shelby County Archives. [19] Further diminishing the quality of the audio recordings is the fact that James Earl Ray was nowhere near the microphone when he gave his answers to Battle’s question. A few of the answers are reasonably clear, but the disputed response to the question about pressure is hard to understand. As a result, I decided to have an audio forensic expert evaluate the audio and see if Ray’s response could be enhanced.

I sent the audio file to Sean Coetzee who is the owner of Prism Forensics LLC of Los Angeles, CA. Coetzee is a Certified Forensic Consultant by the American College of Forensic Examiners. He holds a B.A. in Music Production from Brighton University in the United Kingdom. Acting as a paid consultant, he processed the audio file to enhance its clarity. [20]

The result of this process was an audio file that is much clearer, much less noisy, and much easier to understand Ray’s responses. And in his own voice, two things are quite clear about the disputed answer regarding pressure. First, Ray most certainly did not give the unequivocal negative answer to the question about pressure as the doctored transcript records. That is ruled out when you listen to the enhanced audio. Second, Ray clearly gave an equivocal non-answer answer to the question about pressure. In the exchange between Battle and Ray, the enhanced audio sounds like Ray answered thusly:

THE COURT: Has any pressure of any kind by anyone in any way been used on you to get you to plead guilty?

A [JAMES EARL RAY]: I don’t know what to say.

Even this is open to interpretation of the final word in Ray’s answer. He either said: “I don’t know what to say,” or, “I don’t know what to think.”

If anything, Ray’s spoken answer was even more clouded than the original Koster transcript. Koster, however, had the advantage of being present in person and only a few feet away from Ray, as well as a much clearer recording than remains today. But in either case, Ray never answered the question about pressure. If that question was important enough for Battle to ask it; if it was important enough for the district attorney and Ray’s own lawyer, Percy Foreman, to give him a scripted, negative answer a whole day in advance of the sentencing hearing; then it was important enough for the court to stop and entertain a truthful, full answer.

Ray was off script and headed who knows where. Battle had a duty to justice to find out what was on Ray’s mind, and a duty to humanity to find out the darker truth behind Ray’s hints. Instead, in that moment he weakened and let ignorance become a substitute for truth in his court. That’s not necessarily surprising since Arthur Hanes, Jr. told me that he and his father felt Battle was under enormous pressure from outside the courtroom. He said Battle “didn’t handle it very well.” In the next three chapters we will see just how enormous the pressure really was, and from all the sources that it emanated. Perhaps Lesar put it best, Battle “blew it.”

The HSCA’S Legacy of Using the Altered Transcript For Its Legal Analysis of Rat’S Guilty Plea

G. Robert Blakey’s HSCA staff had it within their power to discover the altered transcript and stop the judicial charade that had kept Ray in prison without a trial, and obscured the truth from the American people. Instead of courageously blazing a trail of truth, Blakey’s staff continued a disingenuous parody of the truth.

Blakey’s staff compiled a bibliography of 93 book and magazine titles on the MLK assassination by the time they finished their work in early 1979. [21] What they did with the bibliography is anyone’s guess since Blakey refused to say whether any staff member(s) was assigned to read them. But the bibliography is evidence of the published material that was in Blakey’s possession. Among these 93 titles includes The Strange Case of James Earl Ray by Clay Blair, Jr., and A Search for Justice by John Seigenthaler and Jim Squires. Both books accomplished what Blakey’s multi-million dollar, multi-year investigation did not: They got it right vis-à-vis the issue of the transcript.

If Blakey had actually assigned someone to read those books and compare what those books said about the transcript, they would have discovered the alteration. Further, if Blakey had assigned someone to listen to the audio recordings of the March 10, 1969 hearing, they would have likewise discovered the problem. But Blakey did not instruct his staff to do their own diligence about the transcripts—or did he?

Perhaps someone on the HSCA staff discovered the altered transcript and there was a deliberate order to cover it up. Blakey’s refusal to say provides no comfort to anyone who wants to believe he had nothing to do with a cover up. Yet, if Blakey had revealed that the courts had ruled against James Earl Ray based, in part, on altered evidence; this would have triggered a new round of appeals with a significant likelihood that the courts would vacate his guilty plea and order a full trial. The government’s failure to prove it had the murder weapons would have been tested in open court. The planted evidence against Ray (the green bundle that implicated him) would have been analyzed and re-analyzed. If the defense could prove the evidence was planted rather than real, a conspiracy to murder Rev. King and blame it on Ray would have been exposed. I don’t think Blakey was going to let that happen under any circumstances. Blakey turned his back to the truth.

It cannot be disputed that the HSCA used the altered transcript in its evaluation of the evidence against Ray. After all, they quote from it right in the middle of page 316 of the Final Report:

THE COURT: Has any pressure of any kind by anyone in any way been used on you to get you to plead guilty?

A [JAMES EARL RAY]: No, no one in any way. [22]

Blakey says none of these facts amount to “a hill of beans.” But he knows better. He now knows his staff relied on doctored evidence whether he knew it then or not. He now knows that a one-man investigative writer, myself, exposed what his staff did not; thus he knows how simple it would have been for his staff to do the same.

The book may be purchased here.

____________________ Footnotes ____________________

[8] Respondent’s Post-Hearing Memorandum, filed by the Tennessee Attorney General in Federal District Court in Memphis, Ray v. Rose (case C-74-166), November 29, 1974.

[9] Interview with James H. Lesar by telephone, April 14, 2012.

[10] Memorandum, Ray v. Rose, U.S. District Court Middle District of Tennessee, Judge L. Clure Morton (March 30, 1973).

[11] Telephone interview with James H. Lesar, April 14, 2012.

[12] Telephone interview with Stephen C. Small, June 4, 2012.

[13] Telephone interview with William Henry Haile, May 17, 2012.

[14] Telephone interview with Charles E. Koster, June 25, 2012.

[15] Affidavit of James A. Blackwell, April 19, 2013.

[16] Affidavit of Charles E. Koster, May 6, 2013.

[17] Memorandum Decision, Ray v. Rose, (case C-74-166), U.S. District Court Western District of Tennessee, Judge Robert M. McRae, Jr.

[18] James Earl Ray, Petitioner-Appellant, v. J. H. Rose, Warden, Respondent-Appellee, 535 F.2d 966 (6th Cir. 1976).

[19] Several email exchanges between the author and Vincent Clark of the Shelby County Archives, April and May 2012.

[20] This is Coetzee’s description of the audio enhancement process: The enhancement process was conducted in Izotope RX 2 advanced program. A band pass filter was first applied to the recording in order to reduce frequencies outside of the speakers’ vocal range. A limiter was then used to even out the volume difference between the Judge and the accused. Due to the low level of the accused voice and the amount of interfering noise, the accused voice could only be raised by a few decibels. An equalizer was then used to boost certain frequencies of the speakers’ voices for intelligibility purposes. A de-noiser in spectral subtraction mode was used to reduce the volume of interfering frequencies. An unvoiced section of the recording is used as a reference and then subtracted during the speech sections of the recording.

[21] HSCA MLK Vol. XIII, 290-299

[22] HSCA Final Report, 316.