CRITICAL ARRB FINAL DETERMINATIONS BURIED AND IGNORED.

SERIAL NEGLIGENCE…OR THE MECHANICS OF SUPPRESSION?

By: Andrew A. Iler

June 27, 2025

PART II

Recap of Part I and Overview of Part Two

In Part One of this two-part series, we examined the legal framework established by the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act, 1992 (“JFK Records Act” or the “Act”), looking particularly at the Assassination Records Review Board’s (“ARRB”) mandate to issue agency final orders, known as “Final Determination Notifications”, for each and every assassination record that it reviewed during its four-year existence. Part One also looked at how the ARRB and the Executive Office of the President actually implemented the statutory process unanimously passed by Congress in the Act.

There is a provision in the Act that is absolutely critical to the enforceability of the ARRB’s declassification decisions. Section 9(d)(1) of the JFK Records Act mandated that after the ARRB issued a Final Determination Notification, the President only had 30 days in which he was legally authorized to issue a written certification overriding an ARRB Final Determination. After that 30-day period expired, if the President did not issue a written certification overriding an ARRB decision, the ARRB Final Determination became the final, binding and enforceable legal order governing the disposition of the associated assassination record.

President Clinton appointed the ARRB in April 1994, and it ceased its operations in September 1998. In that 4-year period, and as confirmed by Judge John Tunheim in his testimony before Congress on May 20, 2025, the ARRB reviewed and voted on the disposition of over 27,000 assassination records and issued Final Determination Notifications for each record it reviewed and voted on. President Clinton did not issue one single written certification overriding any ARRB Final Determination.

Records show that the ARRB issued tens of thousands of Final Determinations that:

- Released records in full;

- Postponed release of records in part to be reviewed or released on future specified dates;

- Postponed release records in full to be reviewed or released on future specified dates; and/or

- Ordered periodic review of assassination records on specified dates or occurrences.

Again, once the ARRB issued a Final Determination order that was not overruled by the President, as provided in the Act, there was no further discretion or authority by any government office or agency on declassification. All that was left were ministerial duties of the Archivist and NARA to archive, publish and release assassination records as ordered by the ARRB. Part Two of this series will explore the key legal concept of ministerial duties and how the ARRB Final Determinations were required to be published and subsequently handled by the Archivist of the United States once they were issued, and finally, what happened to tens of thousands of these “binding and enforceable” legal orders once the Archivist of the United States and the National Archives and Records Administration (“NARA”) assumed full legal responsibility under the JFK Records Act for the custody of the Assassination Records Collection and for the management and implementation of the ARRB Final Determinations.

Ministerial Duties… Ignore them at Your Own Peril

We won’t spend long delving into the deep foundations of legal history, however, a basic understanding of the importance of ministerial duties is fundamental to knowing how the JFK Records Act was meant to operate. This has never been fully understood by the general public or even by experienced JFK assassination researchers. However, it will become clear that if the Archivist had complied with the mandatory, non-discretionary ministerial duties in the JFK Records Act, many of the assassination records ordered released by the ARRB and President Clinton in the 1990’s would have been disclosed to the public BEFORE Presidents Trump or Biden had to take any action starting in 2017.

Like most other former British colonies, the United States shares a rich history of legal concepts and doctrines that have their origins in ancient English law. The area of law generally called “administrative law” especially shares connections with its English common law cousins. Concepts such as mandamus, ministerial duties, and to a later extent, judicial review, all originated in England and were transported to and uniquely evolved in jurisdictions around the world. The vestiges of old English law still resonate throughout modern American law. A case in point is the concept of ministerial duties. Senior government officials in the United States are not called “ministers”, like they are in the United Kingdom, yet officials who run agencies and departments have administrative and decision-making powers and duties that are specified by statute. Many statutory powers and duties grant officials broad discretion in the implementation of policies and decision-making, while other of their duties are completely prescriptive and do not allow for any discretion to be exercised. These latter kinds of duties must be executed precisely in accordance with the legislation that grants the specific official with the power and duty to act. Those duties are termed “ministerial”.

In practice, a ministerial duty is a very specific statutorily imposed duty or legal responsibility that is mandated on a specific official or specified agency, who must execute the duty or responsibility exactly as the law requires. Such duties are described as “mandatory”, “precise”, “non-discretionary”, “discrete”, and as “leaving no wiggle-room” for the official in the performance of the duty. Ministerial duties are an essential element in ensuring that the rule of law governs official actions and that the application of the law by officials is not arbitrary or capricious. Official actions can be challenged in court for non-compliance with ministerial duties for (a) incorrectly executing the ministerial duty; (b) for entirely failing to act; or (c) for delaying action with respect to a ministerial duty. In short, an agency charged with a ministerial duty has essentially no discretion and must follow the requirements of the very law that empowers that agency.

Successfully pleading a complaint against an official who is not compliant with a ministerial duty requires a very particularized and detailed structure. Plaintiffs must set out the necessary elements, or risk their lawsuit being dismissed by the court. Above and beyond the typical requirements imposed on all lawsuits to properly plead issues such as jurisdiction, standing, and injury-in-fact, the critical elements of a claim for non-compliance with a ministerial duty must clearly state (a) the specific statutory provision (including the precise text of the statutory provision or provisions) that impose the ministerial duty; (b) the specific official or agency to which the statute mandated the duty; and (c) evidence to show exactly how the official failed to act; failed to comply with the mandatory and precise ministerial duty; or delayed performing the mandated action. Courts never like to tread on the authority of the executive or legislative branches of the government and will refuse to do so unless all of the necessary elements of a claim are properly pleaded.

The importance of ministerial duties to successfully enforcing the most critical provisions of the JFK Records Act cannot be understated. What we have learned in Part I of this article and what is still to come in this Part II, should make it crystal clear that pursuant to section 9(c)(3)(B) of the Act, the ARRB itself had a mandatory and non-discretionary duty to transmit each of its Final Determination Notifications to the Archivist of the United States, and pursuant to section 5(g)(1) of the Act, the Archivist had a mandatory and non-discretionary duty to implement the ARRB Final Determinations, each of which was a binding and enforceable legal agency final order.

The Hunt for Copies of ALL ARRB Final Determinations Begins!!!

In drafting the JFK Records Act, Congress made clear that the overriding purpose of the statute was the complete and timely disclosure of all assassination records so that the American people could for themselves understand the true facts and history of the Kennedy assassination. The ARRB Final Determination Notifications were the pointy end of the legal spear created by Congress to ensure that the records would be released in a timely manner. As we will see below, Congress included provisions in the JFK Records Act that set in place mandated public disclosure of the ARRB’s decisions through the Federal Register and through several other forms of required reporting.

Given the obvious legal importance of each and every ARRB Final Determination, a reasonable person could very easily be led to believe that Congress would not simply allow for these records to disappear and fall by the wayside…. but hold on….. these are JFK assassination records. Don’t get your hopes up! It will not be as easy as just requesting copies of the Final Determinations from the National Archives (which was the obvious and first step taken in a many months long effort to secure copies of these elusive agency final orders).

Publication of ARRB Final Decisions

In order to ensure that the JFK Records Act’s purpose and mandate to create a transparent, accountable and enforceable process for the review and ultimate disclosure of all assassination records was fulfilled, Congress legislated numerous provisions (sic ministerial duties) in the JFK Records Act that mandate precisely how the ARRB was to publish its agency final orders. What effectively amounts to notice provisions in the Act ensured that the Archivist, the originating agencies, the President, Congress, the National Archives, and the public were all to be given effective notice of every ARRB determination.

In several sections in his Analysis of the JFK Records Act, ARRB Legal Counsel, Jeremy Gunn, correctly parsed out all of the reporting obligations of the ARRB [pp 5-6 and p. 16].

The JFK Records Act mandated four specific methods through which the ARRB was required to report their decisions:

- Publishing notifications of Formal Determinations in the Federal Register;

- Issuing notices of Formal Determinations to originating agencies and other officials;

- Issuing full written detailed Final Determination orders showing the ARRB’s reasons for their final decisions under the standards of the Act where agencies sought postponement; and

- Annual Reporting.

NOTE the correct distinction made by Dr. Gunn with respect to the separation of Executive Branch records and Legislative Branch records, which will be explained in further detail later in this article.

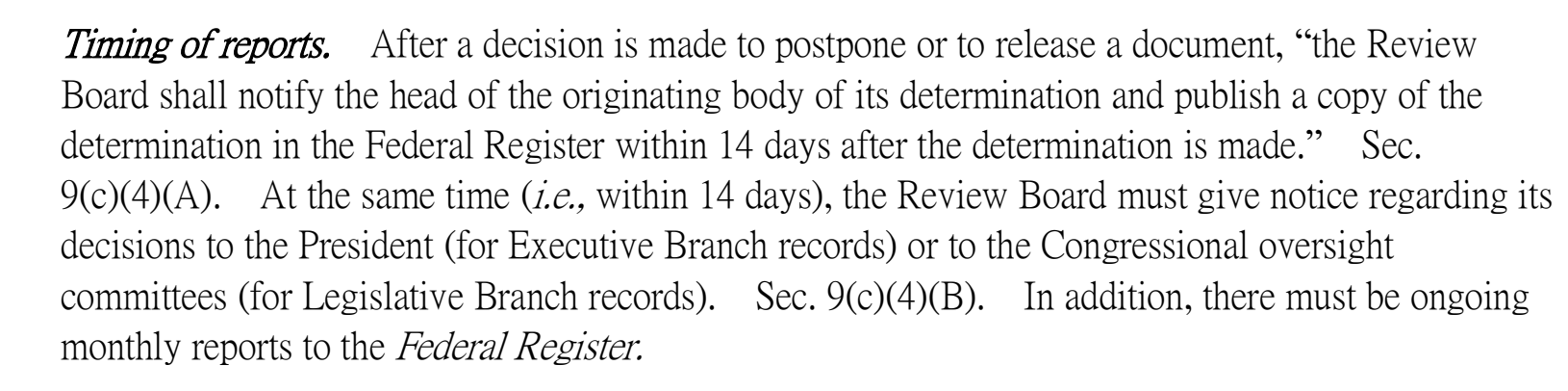

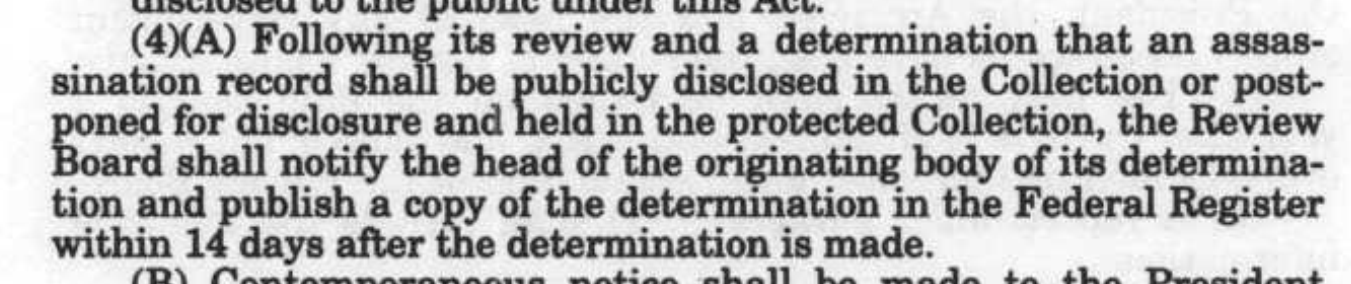

1. Federal Registry Notices

Section 9(c)(4)(A) of the JFK Records Act [below] required the ARRB to publish copies of each of their determinations in the Federal Register within 14 days of issuing the determination. A sample of a Federal Registry notification of Formal Determinations is attached here. As you can see, these are very streamlined and simple notices that only display the name or the agency that originated the record, RIF#s, number of postponements, and the date on which either Periodic Review or Release of the record was ordered by the ARRB. As explained in Part One, Formal Determinations are not Final Determinations, as they lack the detailed reasons for declassification decisions and the precise orders for periodic review or the release of records.

During its four years of operations, the ARRB dutifully and regularly published notifications of its decisions in this summary format in the Federal Register after each of the Board’s meetings. The public can continue to easily search for these notices at https://www.federalregister.gov/agencies/assassination-records-review-board.

2. Notice of Formal Determinations

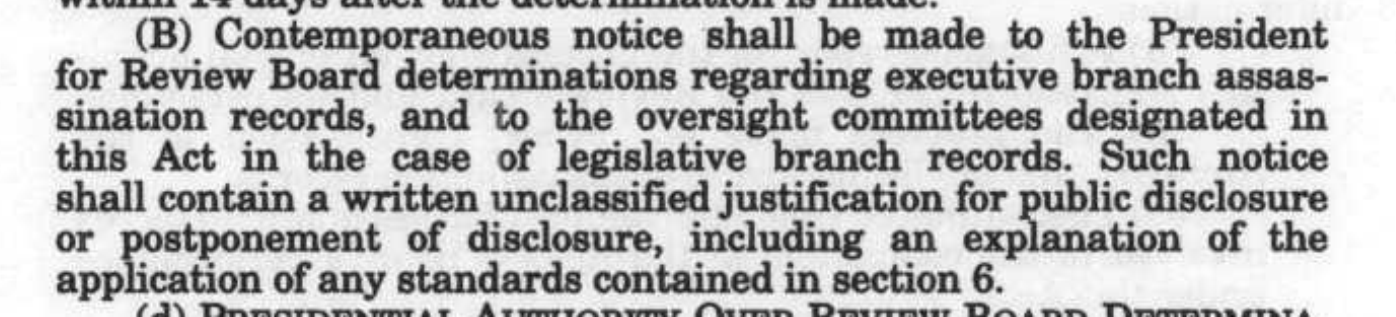

Section 9(c)(4)(B) [below] required the ARRB to give the President notice of determinations regarding decisions for executive branch records and notice to the respective oversight committee for non-executive (congressional) branch records originating from the House or the Senate. These reports became the ARRB Formal Determination notices.

A copy of the June 20, 1995, letter to President Clinton giving notice of the very first ARRB Formal Determinations can be seen here, and a letter and notice to the CIA of some of the last ARRB Formal Determinations are attached here. By all accounts, the ARRB was compliant with the requirement to notify the President and Congress of its decisions in this summary fashion, thus providing all government offices and agencies with notice and due process for any appeals of ARRB declassification decisions as provided in the JFK Records Act.

3. Final Determinations

In his Analysis, [p. 16, excerpted below] Chief ARRB Legal Counsel Jeremy Gunn also recognized that while the JFK Records Act specified that certain information was to be contained in each of the different reports, for the sake of efficiency, the ARRB would provide the originating agencies and the National Archivist with a more detailed and comprehensive report which became the ARRB Final Determination Notification. This is crucial because only Final Determination Notifications provided the precise reasons under the standards of section 6 of the JFK Records Act for continued classification of a record or redaction, as requested by originating agencies and agreed to by the ARRB, and a final ordered date for periodic review or RELEASE of the record.

As was discussed in Part One of this article, section 9(c)(3) of the JFK Records Act mandated that the ARRB “shall create and transmit to the Archivist” a detailed “Report” for each record that it postponed the release of a record or information within a record. Only the ARRB Final Determinations contain the detailed written reasons for the postponements, the actions of the Review Board, the originating agencies or government offices, and more importantly the explicit future dates or occurrences that should have triggered the Archivist to conduct the mandatory and non-discretionary periodic review or release of each record according to and consistent with the ARRB’s orders. In a nutshell, the issuance of these Final Determination Notifications established the legal framework for an accountable and enforceable periodic review process under the JFK Act.

Also in Part One, we learned that it was a large project for the ARRB staff to physically print paper copies of all Final Determinations and attach those copies to each associated assassination record, before the assassination records were transmitted to the National Archives to be catalogued and included in the Collection. We know that this happened and that copies of the ARRB Final Determinations were transmitted with their associated assassination records to the National Archives. Later in this article, I will explain the very concerning current status of the ARRB Final Determinations at the National Archives.

4. ARRB Annual Reporting

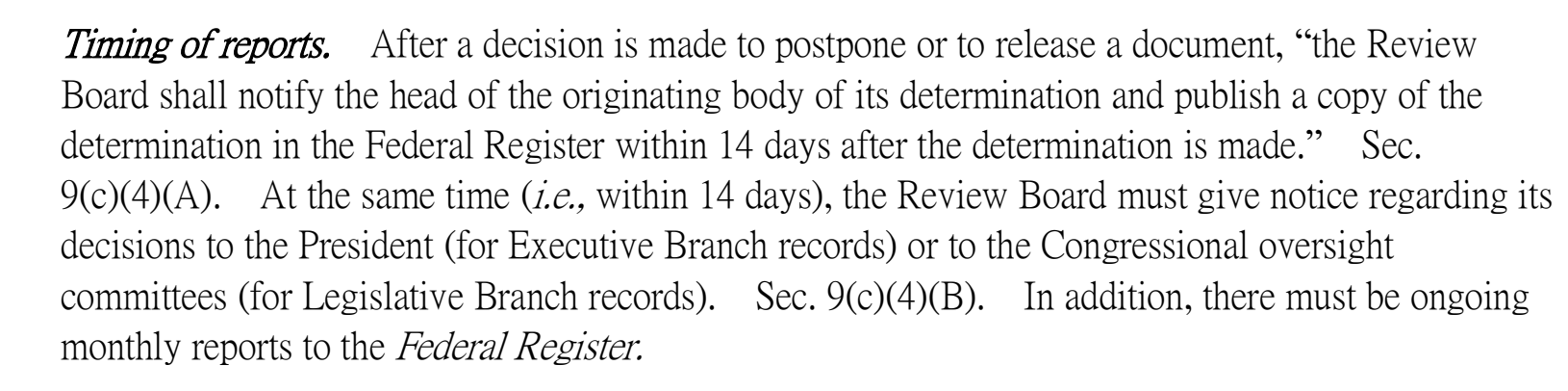

In addition to the more timely reporting identified above pursuant to the subsections of 9(c), the ARRB was also required to report on its activities annually pursuant to section 9(f) of the Act [below]. Section 9(f) [below] provides that the ARRB shall issue an “Annual” Report regarding all of its activities every 12 months no later than by October 26 (the anniversary of the passage of the JFK Records Act) for each year of its operation.

Section 9(f)(3)(G) [below] specifically required the ARRB to include in each Annual Report an appendix containing copies of all of the Final Determinations issued during the calendar year of the Report. This is important because the Annual Reports were intended to show the actual work of the ARRB annually on postponement requests made by government offices and agencies. These Reports were to be made fully available to the public.

Section 9(f) contains a lot of mandatory and non-discretionary language, namely three (3) separate usages of the mandatory word “shall”. The first shall in section 9(f)(1) requires the ARRB to issue a Report regarding all of its activities and says exactly who is to receive a copy of the Report. The second shall in section 9(f)(2) specifies precisely when and how often the Report is to be issued by the ARRB. The third and final shall states exactly what information is required to be included in each Report. The repeated use of the word “shall” and the very precise command to perform discrete actions being placed specifically on the ARRB indicates that the ARRB was being ordered to perform ministerial duties, and that these were not merely suggestions on the part of Congress.

On page 9 of its Final Report, the ARRB acknowledged its duty to issue an Annual Report, by stating, “Finally, the Act required the Review Board to submit, to the President and Congress, annual reports regarding its work.”

IMPORTANT NOTE: The “reports” required to be sent to the Archivist under 9(c)(3) (as mentioned in section 9(f)(3)(G)) were the only notifications wherein the ARRB was required to include all of the detailed written reasons for each postponement, the activities of the ARRB and the ordered date or occurrence for the triggering of periodic review or release of the record. 9(c)(3) “Reports” are the ARRB Final Determinations and the ARRB had a mandatory and non-discretionary duty to issue a Report every year during its operations that included an Appendix containing copies of all Final Determinations that it had issued during the year of the Report. Copies of the Reports were to be sent to the leadership of the Congress, the Committee on Government Operations of the House of Representatives, the Committee on Governmental Affairs of the Senate, the President, the Archivist, and the head of any Government office whose records have been the subject of Review Board activity.

As sections 9(c)(3) and 9(f) of the JFK Records Act clearly show, Congress made certain that copies of all of the ARRB Final Determinations would be sent to the Archivist and the National Archives to be included in the Records Collection and that copies of all ARRB Final Determinations would also be published annually in a separate appendix in the ARRB Annual Reports from 1995 to 1998. Also, as was noted in Part One, the ARRB’s Jeremy Gunn confirmed, the ARRB specifically created the Final Determinations to be public facing and to not contain any classified information, even for records that were ordered postponed from public disclosure. All of the 27,000+ Final Determination Notifications should therefore be available for review by the public, and the Archivist should have been using the ARRB’s software system to diarize the mandated periodic review and release of the records consistent with ARRB’s Final Determinations, right? ………. RIGHT??

So What Happened?

Given that section 9(c)(3) clearly imposed a non-discretionary mandatory ministerial duty on the ARRB to create and transmit to the Archivist each ARRB Final Determination for which the associated record was postponed from public disclosure, the first place to look for copies of the Final Determinations would obviously be at the National Archives and Records Administration. This is made all the more sensible because section 7(o)(3) [below] required that all ARRB records be transferred to NARA to be included in the Collection and that no ARRB record shall be destroyed and we know that on its final day of operations, on September 30, 1998, Chet Rhodes was responsible for packaging up and transferring all of the essential computer hardware, harddrives, servers, backup discs, and the Lotus Notes software needed to maintain the entire ARRB Review Track and Final Determination system.

Internal ARRB records, including email between senior ARRB staff, show that the transmittal of the assassination records to the National Archives could only occur once the ARRB Final Determination Notifications had been physically attached to each assassination record and that this process was an extremely high priority for the ARRB.

An October 31, 1997 email between ARRB staff members Eileen Sullivan, Joseph Freeman, Kevin Tiernan, Bob Skwirot, and Tom Samoluk shows that the National Archives was not simply a passive recipient of assassination records and ARRB Final Determinations, but was actively monitoring the transfer of records from the ARRB to ensure that each assassination record had an associated ARRB Final Determination Notification physically attached to it when records were transferred to NARA. Martha Murphy was a senior Archives employee, who for many years was deeply involved with the Kennedy Assassination Records Collection.

Date: 10/31/1997

From: Eileen Sullivan

To: Joseph Freeman

Cc: Kevin Tiernan; Bob Skwirot; Tom Samoluk

Subject: 2 final determination forms

Because we received a request after we issued an advisory, 2 HSCA documents were transferred to the Archives ahead of the pack. They are the HSCA deposition transcripts of Rowley and Kelley (180-10115-10111 and 180-10115-10112, respectively.). They were sent to NARA without final determination forms and Martha Murphy called to remind us to send them along. If someone can do this, I will make sure Martha gets them.Thanks!

An interesting aside… neither RIF#s 180-10115-10111 nor 180-10115-10112 can presently be found on either the National Archives database or on the Mary Ferrell website, although both records were apparently “Released in Full” by the ARRB in July 1997.

NARA and the Archivist have no excuse not to be fully aware of the ARRB Final Determination Notifications, because the Archivist himself had a non-discretionary mandatory ministerial duty pursuant to section 5(g)(1) of the JFK Records Act to conduct Periodic Review of the postponed assassination records “consistent with” the ARRB’s Final Determinations and pursuant to section 5(g)(2) had a further ministerial duty to publicly disclose such records that were ordered released by the ARRB. The concept of the periodic review process was a very key and prominent part of the JFK Records Act legislation, and the internal ARRB communications clearly show that both ARRB staffers and senior Archives employees knew exactly what they needed to do in order to comply with the periodic review and public disclosure requirements of the Act.

The quest for the ARRB Final Determination Notifications commenced in early 2021, with basic searches on the internet through the webpages of the Black Vault, Mary Ferrell Foundation and the National Archives. While these resources produced a very small handful of random records, no wider collection of Final Determinations could be found. This led to direct communications with the National Archives in the fall of 2024 and an eventual visit to the Archives campus in College Park Maryland in mid-November 2024, along with fellow researchers Paul Bleau of Quebec City and Jeff Crudele of Florida.

Andrew Iler, Jeff Crudele and Paul Bleau at the National Archives

College Park, Maryland – November 20, 2024

In the lead up to the three-day research trip to NARA in the third week of November 2024, numerous email communications were exchanged with Archives staff to ensure that it was clearly understood that it was the ARRB Final Determinations that were being sought. The Archives’ initial response was to deny the entire request, claiming that the timelines for making an “Advance Pull Request” had not been met. This was incorrect and the Archives staff person eventually capitulated and agreed to pull some (but not all) of the requested records. There was a total refusal to consider pulling any of the Final Determination Notifications for records that remained in the segregated/withheld part of the Collection. This was particularly concerning because ARRB Legal Counsel Jeremy Gunn had expressly advised that all ARRB Final Determinations should be publicly accessible regardless of the status of release of the assassination records themselves. The refusal of the Archives to consider releasing the Final Determinations for records that were postponed from release is also contrary to the entire purposes of the JFK Records Act, that mandate a transparent, accountable and enforceable process for the release of all assassination records.

Upon arrival at the Archives in College Park, and after signing in and having credentials approved, an elevator took us to the second floor Textual Research Room where a heavy cart containing approximately sixteen grey boxes was wheeled out for me to be taken to a research table, where my high speed scanner and computer were set up. I immediately commenced digging through the contents of the grey boxes, starting from the first box on the top left of the cart and working my way through 6-7 boxes on the top shelf of the cart. As I sifted through the files, I became more and more concerned, as no sign of any ARRB Final Determination Notifications emerged from the musty boxes. By the time I had finished searching the entire second row of boxes, I had become fully disillusioned and more than concerned that I had wasted my time and money travelling to the National Archives.

What was contained in most of the boxes on the top two shelves of the cart were the summary ARRB Formal Determination notices and Federal Register publications, not the ARRB FINAL Determinations.

One of many NARA boxes of ARRB FORMAL Determinations.

Fortunately, there were three boxes left to search on the bottom shelf of the cart and with only two boxes remaining, I quietly, but triumphantly declared “JACKPOT!!” to Paul and Jeff. A box full of ARRB Final Determinations opened like the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The only contents inside a grey box confusingly labelled “PRESS AND PUBLIC CONTACTS”, were 450 ARRB Final Determination Notifications, all of them issued by the ARRB in 1996. I immediately started scanning and saving all of the notifications. Mind you, there were supposed to be over 27,000 Final Determination Notifications available for our inspection.

NARA Box Containing ARRB Final Determinations labelled “PRESS AND PUBLIC CONTACTS”

Hope of the last boxes containing any of the remaining 26,500+ ARRB Final Determination Notifications turned to despair, as the final box on the cart only contained a dozen or so loose and disorganized Final Determination Notification forms.

A senior JFK Archivist was questioned about the whereabouts of the rest of the collection of ARRB Final Determinations and about the confusing nature of the box label. He agreed that the label made no sense given the contents of the box. He was unable to provide any explanation or assistance in locating further physical copies of the records or the location of the rest of the ARRB Final Determinations. The Archivist was also questioned about the likelihood of there being an electronic collection of the Final Determinations, but this too led to no productive response. Requests made to other Archives staff also did not produce any additional records or leads.

After requesting additional boxes of records, which seemed to have the potential to contain Final Determinations and making every effort to ask multiple Archives staff the “right questions in the correct manner”, it was clear that there was no interest on the part of the National Archives to assist in finding either physical or digital copies of the Final Determinations during our visit.

The grand sum of three days spent at the National Archives was 450 ARRB Final Determinations. This amounts to 1.6667% of the total estimated number of Final Determinations known to be issued by the ARRB as required by JFK Records Act, and required to be properly archived and accessible at NARA. We will circle back to these 450 documents later in this article, as they provide a glimpse into the problems that will become unavoidably clear. The importance of the Final Determinations cannot be emphasized enough, as they reveal the most important work of the ARRB with respect to each assassination record that agencies fiercely sought to postpone the public disclosure through delay, obfuscation, suppression, and other methods.

With the in-person visit to the National Archives only successful in obtaining 1.6667% of the 27,000 ARRB Final Determinations that are known to exist SOMEWHERE at NARA, and the Archive’s apparent refusal to facilitate access to these critical records, it was obvious that an alternative plan was needed to locate and access these records that by law were required to be made public as part of the JFK Records Act mandate to create a transparent, accountable and enforceable law to ultimately release all Kennedy assassination records.

“PLAN B” – The Search for ARRB Annual Reports

As discussed above in detail, under section 9(f) of the JFK Records Act, the ARRB was legally required to issue an Annual Report of its activities each year during its operations between 1994 and 1998. Strictly applied, this would suggest that there should be five ARRB Annual Reports, including reports for both years 1994 and 1998. Section 9(f)(3)(G) of the JFK Records Act added a further legal requirement that each Annual Report include an appendix that contained copies of all section 9(c)(3) “reports” (i.e. ARRB Final Determination Notifications) issued each year. Issuing an Annual Report containing all Final Determination Notifications was a mandatory, non-discretionary ministerial duty imposed on the ARRB by Congress in the JFK Records Act.

Section 9(f) explicitly ordered the ARRB to send each of its Annual Reports to “the leadership of the Congress, the Committee on Government Operations of the House of Representatives, the Committee on Governmental Affairs of the Senate, the President, the Archivist, and the head of any Government office whose records have been the subject of Review Board activity”. With so many mandated recipients of the ARRB Annual Reports, it should not be a tremendously difficult task to find and obtain copies of all five of the Reports, including complete copies of the mandated appendices containing all of the ARRB Final Determinations. Guess again!!

Complete copies of the final ARRB Annual Reports (including the full appendices) are extremely elusive documents. There are many draft versions of only the 1995 and 1996 ARRB Reports (without the required appendices) floating around the common repositories of assassination records.

The first “port of call” to locate copies of the Annual Reports was obviously to the National Archives. Numerous email communications were exchanged with several different Archives staff, specifically requesting copies of the ARRB Annual Reports. While the Archives staff responded to the messages, no responsive Reports or appendices emerged from NARA.

In an email dated Tuesday, February 18, 2025, an Archives staff person wrote,

“I could not locate what looked like a complete set of the annual reports in my searches. Unfortunately, the agency did not provide a central index for these electronic records. The files are arranged in folders as created by the agency, and the names of the folders/files can sometimes be helpful for determining the contents of the files. You will likely need to download the files and unzip them in order to search them for records of interest.”

No copies of Reports for 1994, 1997 or 1998 could be found anywhere. Extensive research for any draft or final Reports for these years turned up nothing. Email communications with the Archives also suggested that there was no evidence of any sign of ARRB Reports from 1994, 1997 or 1998. As a last-ditch effort to determine whether the ARRB issued reports for those three years, contact was made with ARRB Chair Judge John Tunheim and Jeremy Gunn, who both could not recollect whether reports were issued for those years.

With strong indications that no ARRB Reports were issued for 1994, 1997, or 1998, focus was directed towards only the 1995 and 1996 Reports. The second “port of call” was the Library of Congress in an attempt to locate copies of the Reports mandated to be sent to the House and Senate committees. Searches through the Library’s database and lengthy phone calls with Library staff produced no results and no sign of the Reports existing in the Congressional Library system.

After several weeks of searching, a tip arrived from Records Guru Joe Backes, and a faint trail eventually led to the Federal Depository Library system and the Law Library at the Pantalena Law Library at Quinnipiac University in New Haven Connecticut. Thanks to the efforts of an amazingly helpful reference librarian, it was determined that the law library had digital copies of the full final published versions of the ARRB Annual Reports for the years 1995 and 1996… including all appendices! The fact that copies of the ARRB Annual Reports for 1995 and 1996, along with their appendices were not made available during the November 2024 visit to NARA is of further concern.

The 1995 ARRB Annual Report contained in Appendix 1, a full set of 301 ARRB Final Determinations and all Formal Determinations in a second separate appendix. A copy of the List of Appendices taken directly from the 1995 ARRB Report is shown below.

As mentioned in Part One, the ARRB only commenced reviewing and voting on the release or postponement of assassination records in late June 1995. It appears from an analysis of the 301 Final Determination Notifications from the 1995 Report that the very large majority of the Determinations were regarding postponements or redactions of HSCA Staff Payroll information, which included Social Security Numbers, the disclosure of which would amount to an invasion of personal privacy. This information would also not provide any probative value to the assassination itself, so it appears that many, if not most of the postponements in 1995 were simply an exercise in establishing a policy on accepting the redaction of SSNs and making bulk postponements based on that policy.

In regard to the ARRB Annual Report for Year 1996, all available draft versions of the 1996 Report include in the List of Appendices separate appendices for both 1. Final Determinations and 2. Formal Determinations, as shown in the example below.

Strangely however, the final published ARRB Report for the year 1996 does not contain an appendix with all copies of the ARRB Final Determinations. This can be seen in a direct copy of the List of Appendices from the Final 1996 Report below.

Subsequent to the efforts outlined above, in the late spring of 2025, a formal FOIA/JFK Records Act request specifically requesting all ARRB Final Determination Notifications issued by the Board during its operations between 1994 to 1998 was served on the National Archives and Records Administration. NARA has acknowledged receipt of the request, but has failed to provide an update or a substantive response to the request and has definitely not provided copies of the requested ARRB Final Determinations. Options are being weighed in respect to bringing a lawsuit to seek the court’s intervention to compel the National Archives to comply with the law and to release records that were made public almost thirty years ago, and by law were to be the basis of the Archivist of the United States’ ministerial duties to conduct periodic review of the ARRB Final Determinations and to release postponed assassination records in accordance with the final agency orders of the ARRB (which, again, were not overruled by President Clinton or any of his successors).

In a recent email communication received from the National Archives dated June 13, 2025, an Archives staff person denied that the Archives had a set of copies of ARRB Final Determinations. This would appear to contradict the massive weight of documentary evidence that shows that the ARRB transferred both paper copies of all 27,000+ Final Determination Notifications to NARA when the records were transmitted to NARA and access to digital copies of the ARRB Final Determinations made available by the ARRB Press Officers and by the ARRB Computer Specialist Chet Rhodes, who confirmed that all ARRB data and records, and the entire ARRB computer system and harddrives (containing all ARRB Final Determination Notifications) were transferred to NARA when the ARRB wound up its operations on September 30, 1998.

The trail of the ARRB Final Determinations ran completely cold with the locating and obtaining of the additional 301 Final Determinations from the 1995 ARRB Annual Report. This brought the total number of obtained copies of the Final Determinations to approximately 751, or 2.7815% of the 27,000 notifications issued by the ARRB.

That leaves approximately 26,250 ARRB Final Determinations unaccounted for, and the National Archives is ignoring this serious problem without rational or legal justification.

Back to the Big Picture

At this stage, it might be worth taking a few steps back to put the big picture into some perspective. Even those with a mid-level knowledge of the assassination have known for a long time that the ARRB existed in the 1990s and reviewed and released thousands of assassination records. Most of this group of researchers also understand that the JFK Records Act required most, if not all of the assassination records to be publicly released by October 2017. Perhaps a slightly smaller number of researchers have heard of the periodic review process that was mandated by the JFK Records Act to ensure some kind of steady release after the ARRB wound up in 1998. What is surprising however, is how very few serious or expert researchers fully comprehended the legal framework created by the JFK Records Act that governed precisely how the mandated periodic review and release of records processes were actually legally required to happen between the cessation of the ARRB’s operations in September 1998 and the ultimate records release deadline on October 26, 2017. Do not feel (too) badly if you are in this later group of researchers. Without having access to, or being aware of the existence of the ARRB Final Determination Notifications or the legal basis for these absolutely critical agency final orders, there is nothing but a fuzzy notion that releases that were supposed to happen mysteriously just did not.

When Congress enacted the JFK Records Act, it did not simply leave the periodic review and release of records to chance. Congress very clearly mandated that the ARRB would have the legal authority to issue binding and enforceable agency final orders. The Act also imposed a mandatory, non-discretionary ministerial duty on the Archivist of the United States to strictly comply with the ARRB’s agency final orders and to strictly implement the ordered periodic review and release of the assassination records “consistent with” the ARRB’s Final Determinations. As explained below from our findings in small samples of random Final Determinations that have been obtained, these duties were not complied with, resulting in mass confusion and years of delays without any legal justification.

As of today’s date, the National Archives have produced only one box of 450 ARRB Final Determination Notifications (potentially by mistake). This box was labelled “PRESS AND PUBLIC CONTACTS” which rendered its contents virtually unsearchable in the Archives’ Catalog. The Archives have failed to respond to a legally served FOIA/JFK Records Act request for copies of the ARRB Final Determinations, and as late as Friday, June 13, 2025, the National Archives has claimed to have been unable to locate any set of ARRB Final Determinations. How is this all possible? Only the Archivist under oath can answer this question.

What We Found In the Sample of 750 ARRB Final Determinations

In the weeks following the in-person visit to the National Archives in November 2024, with researcher and author Paul Bleau, an interactive and shareable database was created, containing embedded copies of all of the obtained ARRB Final Determinations, along with the latest available copies of the associated assassination records and data from these records. Especially given the celebration in the media over various “releases” by Presidents Trump and Biden starting in 2018, we felt it particularly important to be able to view and compare the specific periodic review and release dates ordered in the ARRB Final Determinations directly side-by-side with the latest releases of the associated assassination records. This side-by-side analysis would easily show whether the ARRB’s orders had been implemented by the Archivist of the United States, who had a mandatory non-discretionary ministerial duty pursuant to section 5(g)(1) of the JFK Records Act to comply with each the 27,000+ ARRB agency final orders that have been hidden away for almost thirty (30) years at the National Archives.

A detailed review of the 450 ARRB Final Determinations obtained at the National Archives in November 2024 shows that the ARRB issued a large number of Final Determinations in 1996, ordering records RELEASED IN FULL by January 2006. The associated assassination records clearly show that despite being ordered RELEASED IN FULL in January 2006, the records remained withheld from public disclosure beyond 2017, with a small number of records continuing to be withheld from public disclosure into 2025. The term “Release in Full” means exactly what it states in plain English – fully released to the public with no redactions.

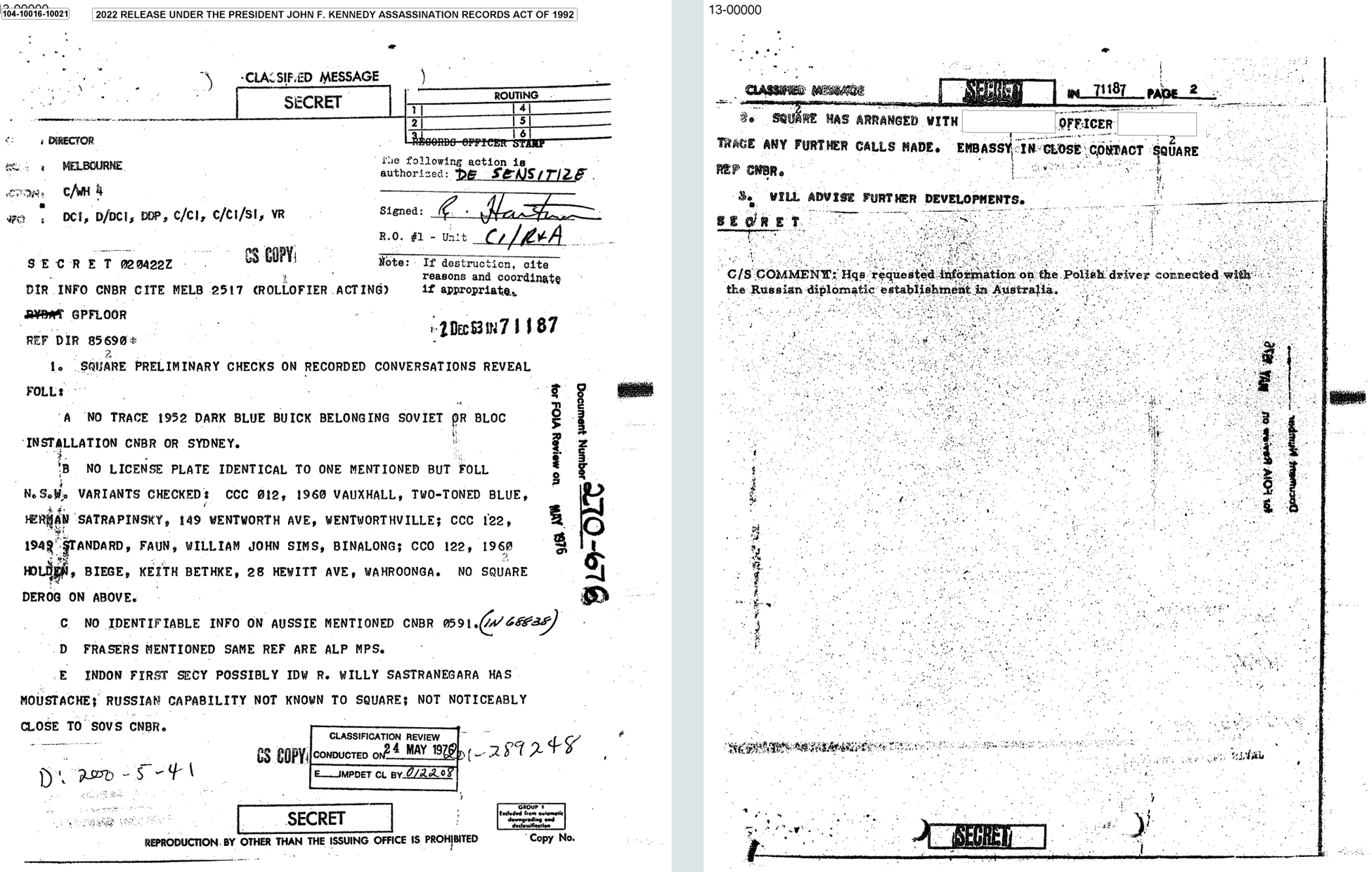

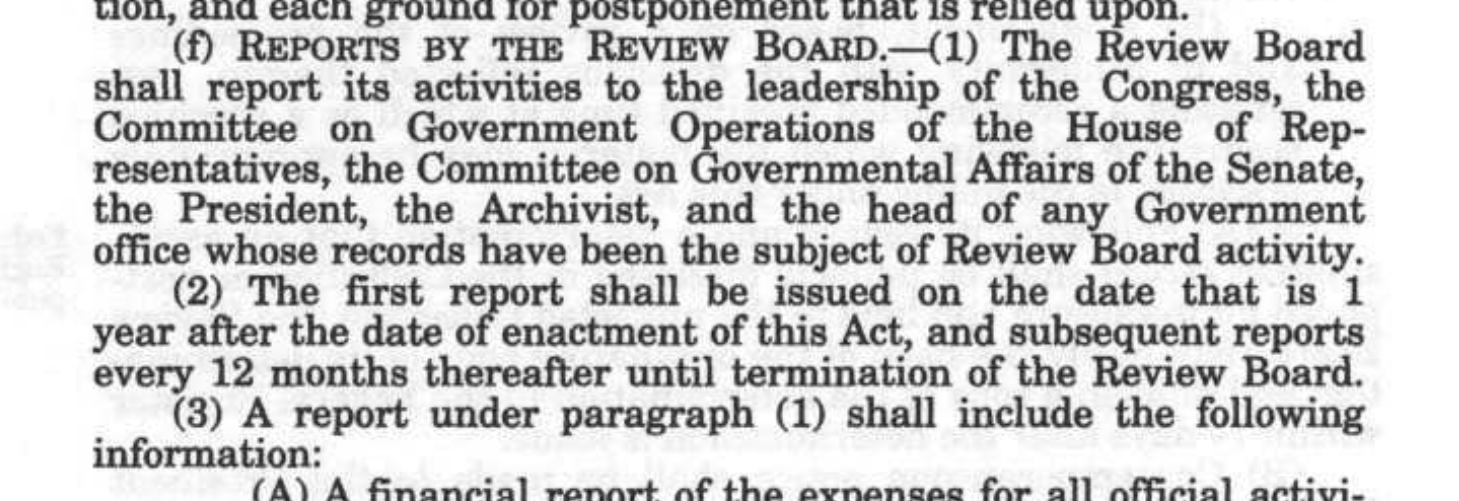

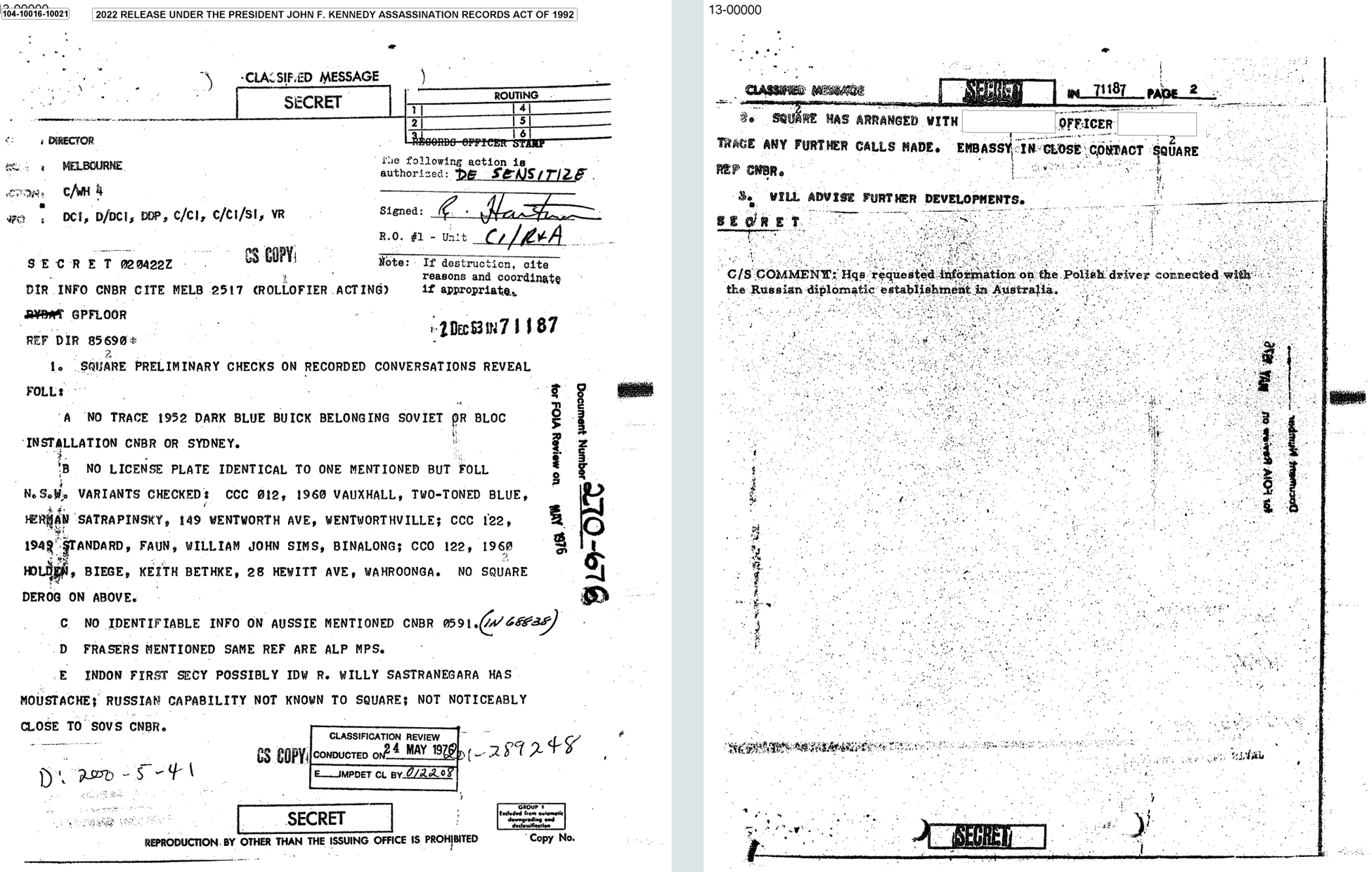

An unambiguous example of such unlawful withholding of the release of an assassination record is demonstrated by assassination record RIF# 104-10016-10021. This CIA SECRET record, dated December 1963 from Melbourne and addressed to the Director of Central Intelligence, was ordered to be fully released by January 2006 in the ARRB Final Determination dated April 18, 1996. Copies of the ARRB Final Determination and the assassination record are reproduced below, but can be seen in finer detail by clicking the hyperlinks above. This assassination record was only just released in March 2025, a delay of almost 19 years.

ARRB Final Determination Notification RIF# 104-10016-10021

————————————————————————-

Assassination Record RIF# 104-10016-10021

A majority of the 450 ARRB Final Determination Notifications that ordered records to be released January 2006, appear to have been withheld 15-19 years beyond their mandated January 2006 release date, with no sign of periodic review having been conducted, with no record of written reasons justifying the delay of the releases, with no record of Presidential certification authorizing further postponement, and with no public notice of any actions taken to further postpone the releases, all of which are requirements under the JFK Records Act. The Archivist should be immediately questioned under oath by Congressional oversight committees on this inexplicable delay and disregard of the ARRB’s final orders for full release in 2006, which were not overruled by Presidential Certification by President Clinton, who was the only President with the time limited authority to override ARRB Final Determinations. In doing so, the same oversight committees could properly question the Archivist on the 26,500+ ARRB Final Determinations that exist but cannot be located at the National Archives by even the most diligent of researchers.

CONCLUSION

Serial Negligence… Or the Mechanics of Suppression?

Part I of this article set out to detail the long ignored legal framework governing the handling of assassination records under the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act, 1992, including the mandate of the Assassination Records Review Board, which was the independent federal agency granted the authority to collect, review, and postpone the release or release assassination records under the strict standards of the Act.

Readers were introduced to the surprisingly obscure, but critically important document called an “Assassination Records Review Board Final Determination Notification”, which by any and all standards meets the definition of a legal agency final order.

We now fully understand for the first time that President Clinton approved a Memorandum of Understanding with the Assassination Records Review Board, that clearly agrees that the President would only issue written certifications to override ARRB Final Determinations, and that if no override certification was issued by the President within the 30-day time limit imposed by the Act, that each ARRB Final Determination would become the final, binding and enforceable legal order governing the disposition of the associated assassination record. The ARRB Final Report confirms that President Clinton did not issue any certifications overriding any ARRB Final Determination.

There is conclusive evidence from internal ARRB memos, email, interviews, and other communications that tens of thousands of Final Determinations were created and issued by the ARRB between June 20, 1995 and September 30, 1998. And we know from the same sources that each ARRB Final Determination was physically attached in paper form to each assassination record before both both records were transferred to the National Archives and Records Administration facility in College Park Maryland, where the Archivist had the legal duty to catalog and index each record into the Assassination Records Collection.

ARRB Chief Legal Counsel and Executive Director of the ARRB confirmed in writing that every ARRB Final Determination was created to be publicly released, regardless of whether the associated assassination record was postponed from release or not, and that all ARRB Final Determinations should be maintained by the National Archives and accessible to the public.

We also now know through ARRB Computer Specialist, Chet Rhodes, that the entire ARRB computer system, harddrives, databases, and Lotus Notes software, along with written instructions on how to operate and maintain the system and data (including ARRB Final Determination Notifications) were carefully packaged up and delivered to the National Archives at the completion of the ARRB’s mandated period of operations on September 30, 1998.

In this Part II, we have further expanded the understanding of the legal concept of ministerial duties and how they were applied throughout the JFK Records Act to ensure that the mandated transparency, accountability and enforceability processes were in place to guarantee the full and complete release of all assassination records.

Part II also provides significant details regarding the crucial importance that Congress placed on the ARRB giving notice of each of its decisions to the President, Congress, originating agencies, and to the public. This included publishing copies of each ARRB Final Determination in a specific appendix to each Annual Report that the ARRB was mandated by law to issue each year of its operations. The notification process also extended to the ARRB’s mandatory, non-discretionary ministerial duty to provide the National Archivist with copies of all ARRB Final Determinations and to transfer to the National Archives all ARRB records (including Final Determinations) on the completion of the ARRB’s mandate on September 30, 1998.

So much of the story of the assassination and the available public record from the multiple investigations revolves around inexplicable and unconvincing series of errors, omissions, mistakes and oversights. This is particularly true when it comes to the specific area of the assassination records and their full and timely disclosure, as mandated by the clear language of the JFK Records Act and the additional mandates contained in more than 27,000 ARRB Final Determinations.

The fact that almost 98% of the approximately 27,000 Final Determination Notifications issued by the ARRB are still buried at the National Archives and have not seen the sunlight for almost thirty (30) years is a massive problem. The very apparent refusal by the National Archives to provide public access to these records or to even acknowledge their full existence is an affront to the public and should demand serious scrutiny by those committees of Congress that were mandated the authority to conduct oversight of the JFK Records Act and the review and release of all of the assassination records.

The full scope of non-compliance with the ARRB Final Determinations, and the JFK Records Act in general, will not be unassessable so long as over 26,000 of the agency final orders remain withheld from the public. The fact is that the bulk of the ARRB Final Determinations were issued in 1997 and 1998, and to date, not one Final Determination from either of these years has been made publicly accessible.

The JFK Records Act was unanimously passed by Congress as a result of the large-scale public outcry regarding the secrecy surrounding the assassination records and the withholding of millions of pages of records for decades after the event. Releasing the assassination records was a priority in the early 1990s, and with the passage of another 30 years, the excuses in 2025 are even more tenuous and unjustifiable in both law and in the spirit of democracy.

How can the U.S. Government certify that full and timely disclosure has been met when the most important work of the ARRB has been buried and ignored at the National Archives? The diligent work by the ARRB, an independent agency, deals with the very records that the agencies have fought so hard to postpone. How have the agencies been permitted to continue holding back disclosure when Congress acted emphatically with the JFK Records Act in 1992, when the ARRB issued final orders on declassification, when the agencies have had due process and an opportunity to appeal ARRB agency final orders, and when the President has not issued ANY certification overruling the ARRB on any of its decisions?

What remains unclear is whether either President Trump or President Biden were made aware that over 27,000 agency final orders on postponements were issued by the ARRB in the 1990s. Section 9(d)(1) of the JFK Records Act only permitted a 30-day period for the President to override ARRB Final Determinations. Once that 30-day period ended, the appeal period expired and the ARRB agency final orders became binding and enforceable. It would seem to be arbitrary and capricious for a president, thirty years later, to come along and apply lesser standards (or no standards at all) to override decisions that were made final decades ago. As Jeremy Gunn stated, the period has “long tolled”. Add to this that no adequate written reasons under the JFK Records Act were provided for any of President Trump or Biden’s postponements, that would allow for any appeal or judicial review.

It would create a legal absurdity to interpret any section of the JFK Records Act to suggest that Congress could somehow impose lesser or no standards for postponement over sixty years after the assassination, when there were such high standards for postponement imposed in the 1990s. Congressional task forces and oversight committees should act now and investigate the status of the ARRB Final Determinations at the National Archives. There are living witnesses who can provide the facts and complete the record.

The fact that the entire ARRB computer platform was transferred to the National Archives in September 1998, along with instructions on how to maintain the Review Track/Lotus Notes software and database of records, which included calendar notifications and the ARRB Final Determinations, but the National Archives apparently took no steps to maintain it, is very seriously problematic…. perhaps bordering on gross negligence.

Since the ARRB Final Determination orders have not been publicly released or transparently catalogued by the National Archives, it has been virtually impossible for anyone to seek enforcement of the ARRB’s orders through judicial review, as the JFK Records Act expressly permits.

Leading up to the statutory deadline of October 26, 2017, both the Archivist of the United States and the Office of Legal Counsel advised President Trump on aspects of the JFK Records Act and the status of the Kennedy Assassination Records Collection. It appears that none of the correspondence or memoranda furnished to President Trump identified the tens of thousands of detailed ARRB Final Determinations ordering the review and release of records that were issued 20 years earlier. Instead, it has become apparent that the ARRB Orders have been suppressed and by all appearances (until now) overlooked and ignored at the Archives.

When President Biden took office in 2021, he inherited the omnibus postponement of records certified by President Trump. It appears that President Biden too was not advised that the ARRB had previously issued tens of thousands of detailed Final Determinations for each assassination record, that even President Clinton did not overrule, including specific detailed “plans” for the release or review of each record. Even worse, when President Biden issued his “final memoranda” regarding the JFK records in 2023, he put the control over the records back in the hands of the originating executive branch agencies, which is completely contrary to the intent and provisions of the JFK Records Act.

The entire purpose of the JFK Records Act was to take the power to withhold the assassination records completely out of the hands of the originating agencies. Those agencies had due process and opportunities for appeal under the JFK Act. The only thing left to do is locate the ARRB’s Final Determinations and ensure that the Archivist follows those final agency orders. The agencies should have no role in that process whatsoever – not in 2025, and not under any provisions of the JFK Act or other applicable law when it comes to assassination records.

The good news is that the Archivist can be held accountable today and to provide an explanation under oath for what happened to the ARRB Final Determinations and to account for the National Archives actions or inaction to implement the ARRB’s lawful and binding orders for the review and/or release of assassination records. Congress, which has oversight of the JFK Records Act, has the authority to command the compliance of the National Archivist regarding the JFK assassination records. With the assistance of Congresswoman Luna’s Task Force and support from President Trump himself, the mandate of the JFK Records Act can still be achieved.

For almost 30 years, scholars, researchers, journalists, and politicians knew that there was a serious breakdown in the periodic review process and release of the postponed assassination records, but it was not understood precisely where this breakdown occurred. The discovery and analysis of the ARRB Final Determination Notifications provide a clear view of what happened to delay the release of assassination records, and ultimately, where responsibility lies.

The extreme and unjustified delay in the public disclosure of these assassination records, already approved for release by the ARRB and the office of the President over the last 30 years, has prevented timely investigation of relevant leads in the case and has prevented the public from understanding the full nature of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Under the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act, 1992, Congress has statutorily mandated duties of oversight with respect to the Act and the release of the records. Congress has not conducted any meaningful oversight of the Archivist’s duties under the JFK Records Act, despite the very high level of continuing public interest in the case and particularly in the handling of the still secret trove of assassination files. This should be an obvious priority going forward for any congressional investigation.

Click here to read part 1.