Read more here.

Blog

-

UK and US accused of obstructing inquiry into 1961 death of UN chief

The US and UK have been accused by university researchers of obstructing a United Nations inquiry into the 1961 plane crash that killed the UN secretary general Dag Hammarskjold. A conference in London heard an update from the UN assistant secretary general for legal affairs, Stephen Mathias, on progress in the inquiry, which is seeking archive documentation from member states. The participants said the US and UK had been dragging their feet in handing over potentially vital information.

Read more here. (The Guardian)

-

New book on the HSCA by Tim Smith

Tim Smith begins his book on the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA)—titled Hidden in Plain Sight—with two pertinent facts about the John Kennedy murder. First, the FBI found that the alleged rifle used in the case fired high and to the right of the target. Yet, the trajectory from the window which the Warren Commission said the alleged assassin fired from was a slight right to left angle. (Smith, p. 6). He then points out that President Kennedy is reacting to being hit before he disappears behind the Stemmons Freeway sign. And the projectile is rising 11 degrees out of his throat. (Smith p. 13) He follows this by saying, this indicates there was no delayed reaction by Governor Connally, but the Commission said there was. (Smith, pp. 15-16)

Also, the governor is holding his hat at Zapruder frame 230, when the Warren Commission says that his wrist has been shattered. Agreeing with Josiah Thompson, the author says that Connally was likely hit at Zapruder frame 237. And further decimating the Single Bullet Theory, Connally always insisted that he heard the first shot. (Smith, pp. 16-17) He concludes his opening chapter by saying that the HSCA hinted at a later shot at Zapruder 327, after the alleged final shot at 313—which further blows up the official story. Today this last concept has become almost an accepted idea on the part of the critical community. (Smith, pp. 30-31)

What Smith’s book does is chronicle and analyze the testimony of all the witnesses who testified in public before the HSCA. In that respect it is unusual, since I know of no other book that has dedicated itself to such a task. That chronicle begins with John Connally and ends with acoustics expert Dr. James Barger.

I

As Smith goes through the testimony in order, he tries to show that, even with their own witnesses, the HSCA was suggesting the contrary of what would be their conclusions. Although the HSCA ended up maintaining the Magic Bullet and three shot scenario, the testimony of people like Nellie Connally and Robert Groden undermined the ersatz concepts. Smith goes into related areas to show that the cover up about the Zapruder film was a desperate one at Life magazine. He points out the infamous breaking of the plates for the press run of the October 2, 1964 issue in order to cloud the head explosion and Kennedy’s fast rearward movement at Zapruder frame 313. (p. 51)

He returns to the FBI test showing that the alleged rifle fired high and to the right; therefore, at a distance of 60 yards, the shot would have missed by several feet—at least. (p. 65) He also brings in problems with chain of custody, for example the important Warren Commission testimony of Troy West: the man who dispensed paper at the Texas School Book Depository and said Oswald never asked him for any. Undermining the Commission myth that Oswald wrapped the rifle in the Depository paper. (p. 65)

One of the highlights of the book is Smith’s review of the testimony of Ida Dox, the professional medical illustrator who rendered drawings of the medical photos for the HSCA. One of the most startling revelations in the book is that Dox—real name Ida Meloni—said she never saw a picture of JFK’s brain. (p. 80) Smith then deduces that what we may have in the HSCA volumes is a tracing of a tracing. If that; since when Tim asked her if she drew the brain she said she could not recall. (p. 90) But Dr. Michael Baden, chief of the HSCA pathology panel, said she did so.

Smith also delves into the problem that Dr. Randy Robertson first discovered: Baden had her alter the illustration of the back of Kennedy’s skull in order to transform what appears to be a drop of blood in the original, into a bullet wound in the drawing. The book also makes clear, with memoranda, that medical researchers Andy Purdy and Mark Flanagan were aware of this alteration. But when Tim asked her about seeing other illustrations from other books, which the evidence indicates she was supplied with, she did not want to answer the question. (Smith, p. 91) But it is clear that Purdy was the chief researcher on the medical side, and Flanagan was his assistant. (pp. 82-86) And they were securing materials for her. Make no mistake, this was an important strophe by the HSCA. Because it was part of their crucial decision to raise the posterior skull wound from the base of the head to the cowlick area.

Smith writes that Baden’s elevation of the rear skull wound may have been presaged by his association with the Clark Panel doctors. While he was Attorney General, Ramsey Clark had appointed a medical panel to review the JFK autopsy and they had filed a report in which they raised the posterior head wound. Baden made a contribution to an anthology they wrote, and for which Clark wrote the foreword. (Smith, p. 88) As most know, the Clark Panel report first raising the posterior skull wound upward by four inches, was released on the eve of jury selection in the Clay Shaw trial. This made the trajectory of the fatal head shot more credible from back to front, since it now aligned with the nearly straight on positioning of JFK’s head in the Zapruder film, and not the false anteflexed position in the Warren Commission illustrations by Harold Rydberg. (Click here for background on this)

The point being that the HSCA medical panel was gearing up for a Galileo moment for the original Bethesda pathologist, Jim Humes the Kennedy pathologist who had originally written that the wound was at the lower spot. According to Smith, Humes complied by moving both wounds—the head and the back—by about ten centimeters or four inches. Never addressing the question of how wounds move in dead people over time. (p.94)

II

The next group of witnesses also tended to concentrate on the medical evidence in the case. These were Dr. Lowell Levine, Calvin McCamy and Dr. Michael Baden. Levine was a DDS from NYU and was summoned to recognize if the teeth and fillings in the x-rays were President Kennedy’s, which he did. (p. 99) But as the author notes, this does not guarantee that the rest of the x-ray areas could not have been tampered with.

McCamy had degrees in chemical engineering and physics and was a fellow of the Society of Photographic Scientists and Engineers. One of his missions was to verify the legitimacy of the backyard photographs. As the author notes, when McCamy was testifying about the line across the chin observed by many in the photos, and how the chin appears different in the BYP than in other pictures, things got a bit silly. The alleged expert actually said the following:

This photograph is quite remarkable. This was taken by the Dallas police. It shows that it isn’t the picture that has a line across the chin. It is the man that has a line across the chin. He actually has an indentation right here, and that does show up in these photographs, right in the center and right here. (Smith, p. 108)

As the author notes, McCamy was also allowed to make assumptions based on his reading of the Zapruder film. Smith scores him for being allowed to do this and calls some of his observations “beyond silly” for someone who is supposed to be interpreting the autopsy photographs. (Smith, p. 107)

Next up was Michael Baden. Smith notes that according to the HSCA, the rear back wound was rising at about 11 degrees. (p. 113) He also observes that the HSCA did marginally consider a shot beyond Z 313 at about Z 328—which we will deal with later. (p. 116) Smith also scores the Baden idea that the holes in both Kennedy’s jacket and shirt line up with a bullet wound at the first thoracic vertebrae. (p. 119) Tim Smith disagrees and sides with Admiral George Burkley who signed the death certificate with the damage being lower, more aligned with the third thoracic vertebrae.

Smith goes on to say that Baden bought into the magic bullet idea in defiance of Dr. Robert Shaw’s evidence that there was no fabric deposited in Governor Connally’s back, or any found on the magic bullet, CE 399. He asks: how could this be if the bullet theoretically went through 15 layers of clothing? (Smith, p. 121) Smith also contests a posterior headshot at Z 312. He believes, that this ever so slight bob forward is a smear on the film. Josiah Thompson, Gary Aguilar and Paul Chambers think it is also a result of the braking of the car, as Kennedy, who was already hit, drifts forward. (Smith, p. 115, p. 137)

Baden depicted the wound in the cowlick area as a “typical gunshot wound of entrance”. Which on the original pictures, before the Ida Dox artistry, is simply not true. (Smith, p. 122) Smith also contests Baden on the issue of whether or not the pictures and illustrations of Kennedy’s brain are genuine.

In sum, about Baden, who he spends 31 pages on, the author simply says, “He lied and knew he was lying.” (p. 126)

III

Continuing with the autopsy, Smith now takes up the evidence of Kennedy pathologist James Humes, and HSCA forensic pathology consultants Cyril Wecht and Charles Petty.

The author reminds us about Warren Commission attorney Arlen Specter and his questioning of James Humes:

Specter then asked if it would have helped to have the photos and x-rays, to which Humes responded that it might be helpful. Specter follows this up with a rather memorable observation: “Is taking photos and x-rays routine or something out of the ordinary?” (Smith, p. 147)

Only in the JFK case could such questions be raised with a straight face. The author reminds us that Humes did not see the pictures until November of 1966. Which is why Specter asked the question. The big point of Humes’ HSCA testimony is his persuasion by the pathology panel to move the posterior head shot into the cowlick area. (Smith, p. 153). For the Warren Commission, he and his two partners—Thornton Boswell and Pierre Finck—had the entering head shot coming in near the bottom of the skull, four inches lower. Which is a lot of area on the rear of the skull. And, as Smith notes, in their private consultations with the HSCA panel, Humes and Boswell disagreed with that higher placement. (Smith, p.154) But in public, Humes did his Galileo turn.

Under questioning, Humes admitted he did not know who some of the personnel working that night at Bethesda were e.g. photographer John Stringer. Smith adds, this is because he did not do autopsies. (Smith, p. 157) When asked why he did not weigh the brain that evening, he said, “I don’t know.” Humes also said that he did not understand why Admiral Burkley signed the autopsy report, since he did not remember him doing so. (ibid) Smith also comments that Humes only had one HSCA questioner, Gary Cornwell. (Smith, p. 155) Which seems odd considering his importance to the case.

Cyril Wecht is noted for his quite vigorous and effective public dissent from the conclusions of the HSCA pathology panel. He disagreed with them, particularly about the Single Bullet Theory. Wecht wanted certain experiments done, and he did not think that Governor Connally could still he holding his Stetson hat in his hand after his wrist had been shattered. (pp. 167-69). Wecht also objected to the upward and then downward trajectory of the Magic Bullet. (Smith, p. 170). The forensic pathologist also brought up the mysterious problems with locating John Kennedy’s brain, which was missing from the National Archives. Chief Counsel Robert Blakey then indicated that the HSCA had done a study of this and tried to center on the role of Robert Kennedy. Yet the Assassination Records Review Board found out some rather jarring and opposing information about this quite troubling matter. Their information, from two sources, is the brain ended up at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. (Click here)

Charles Petty is an interesting witness. He replaced Dr. Earl Rose as the coroner in Dallas in 1969. He told CNN in 2003 that he thought Kennedy’s autopsy was done well. A remarkable statement which even the HSCA’s Michael Baden did not agree with; in fact, Baden said it was the exemplar of bungled autopsies. (The JFK Assassination: The Evidence Today, p. 61) When once asked if it would be important to examine the brain if the victim died from a head shot, Petty said “It would be nice if the brain were available.” But he then added that it would not be essential since in the JFK case we had the photos and x rays. (Ibid, p. 62). We have now found out of course, that the official photographer in the JFK case admitted to the ARRB that he did not take the pictures in evidence. Which begs the question: who then did and why? (See Doug Horne’s testimony in the film JFK Revisited.)

In his HSCA testimony, Petty brought up Wecht ten times. He said that there was no evidence that CE 399 shattered the rib. (HSCA Vol. 1, p. 377) But then how did John Connally’s rib get smashed? Petty then When asked if it was accurate to say that the bullet went through wrist bone, he replied it was a tangential shot. (Ibid, p. 378) You can read this for yourself, try not to arch your eyebrows. Charles Petty made Baden look a bit decent.

IV

From here, the HSCA public hearings went onward and downward. About the testimony of an HSCA witness who worked for the Warren Commission, Larry Sturdivan, Smith writes, “It was sad to read, sadder to watch on video and pathetic to read in their Final Report.” ( p. 181). Strudivan’s educational background is a B. S. in physics from Oklahoma State, and an M. S. in statistics from the University of Delaware. But yet the HSCA relied on him for some of its most controversial scientific conclusions, like the infamous neuromuscular reaction to explain the fast and powerful backwards motion to JFK getting hit from a shot from behind. (Smith, p. 189) That ersatz doctrine and its application to the Kennedy case had been thoroughly discredited by the work of Gary Aguilar and Wecht. (Click here)

As Smith notes, there is also another thoroughly discredited piece of evidence that the HSCA accepted as fact. That is the key testimony Blakey used to bolster the Magic Bullet, namely the testimony of chemist Vincent Guinn and his so- called Neutron Activation Analysis testing which linked CE 399 to bullet fragments in Connally. After describing the discrediting work of James Tobin, the late Cliff Spiegelman, Eric Randich and Pat Grant, Smith in the field that is now called Comparative Bullet Lead Analysis, Smith writes:

There is now no reason to believe that the bullet fragments retrieved from Governor Connally’s wrist have any connection with CE 399, the magic bullet. (Smith, p. 209)

There were other facts about the HSCA which tended to work against the Warren Commission. For example their expert could not link the projectile fired at General Walker to the rifle in evidence. (p. 197). They also could not link CE 399 to the rifle. The excuse for the latter was that, due to the repeated firing of that rifle, there was a build-up of particles in the barrel of the weapon. (Smith, p. 198) Also, one of their experts, astronomer William Hartman, said he detected a blur in the Z film at around frame 331 which could have indicated a shot after the alleged final hit at frame 313. (Smith p. 220) They were also hearing testimony from a photographic expert that the boxes in the so-called sniper’s nest had been moved between the Dillard photo taken just seconds after the last shot, and the Powell photo taken several seconds later. (p. 426) Marina Oswald told the committee that Lee Oswald liked John Kennedy and spoke well about him. (p. 249). She also said she did not think Oswald was a true communist. (p. 270) James Rowley, Secret Service chief in 1963, did all he could to conceal the fact that there were prior plots against JFK in 1963. (p. 361)

Some of the testimony from people like J. Lee Rankin is hard to take. About the FBI, Rankin said that, “Well, as to their cooperation with us, I thought it was good.” Rankin said that later, after the investigations of the Church Committee, especially concerning the fact that J. Edgar Hoover knew about the CIA plots to murder Castro and did not tell the Commission about it, his opinion about their character changed. I guess we should be thankful for that. (Smith, p. 394). Rankin also said there was no pressure against finding a foreign conspiracy. Odd, considering the fact that they never even interviewed Sylvia Duran of the Cuban embassy in Mexico City. In fact, Luis Echeverria, the Secretary of the Interior at the time, more or less stopped any Commission inquiry into Mexico City. It is hard to comprehend how Rankin, Chief Counsel to the Commission, could not have known about this. By the way, Echeverria went on to serve as president of Mexico from 1970-76.

Rivaling Rankin was the testimony of Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach. Katzenbach was pressed as to why it was so important for him to write a memo 72 hours after the assassination saying the public should be satisfied that Oswald was the assassin. His reply was, “I don’t think that is artistically phrased. Perhaps you have never written anything you would like to write better….” It was also later revealed that Katzenbach did not believe the CIA was involved in any assassination plots. He says be based this on assurances that CIA Director Dick Helms gave to President Johnson in his presence in 1965. (Smith, p. 405)

No comment.

V

Some of the questioning by the HSCA, to be kind, did not seem complete, well-prepared or vigorous. To point out some examples, there was Louis Witt, the Umbrella Man. He claimed he did not know the Latin looking man standing next to him on Elm Street as they stood, and then sat on the curb as the limousine drove by them. (p. 432) He claimed he did not even realize the president had been fatally shot. And he did not know this for sure until after he returned to work that day. (p. 437) He said he was not aware of the path of the motorcade route on November 22nd. (Smith, p. 429)

As most know the HSCA tried to insinuate that if there was a conspiracy to kill JFK it was likely done by the Mob. Therefore they called people like Lewis McWillie, Jose Aleman and Santos Trafficante. McWillie disagreed with the committee as to when he was in Cuba and when he returned to Texas, and also that Jack Ruby was only in Cuba for six days and not a month as the Cuban records show. (pp. 444-45) Aleman claimed he heard Trafficante say that Kennedy would not be re-elected, he was going to be hit. (p. 459)

Trafficante was in a denial mode. He said he never carried poison pills in order to kill Fidel Castro. In fact, he said that all he did was act as an interpreter in the plots because the U. S. government asked him to. He denied the Aleman claim. And he said he never knew Jack Ruby and Ruby never visited him while he was in detention in Cuba. (pp. 463-68)

I will not deal with all the witness that Smith describes and analyzes. But I will say that he goes through every witness involved with the controversial acoustics tape, with which the committee decided that there was a shooter from in front of the limousine. (pp. 487-518) And which, in 2021, Josiah Thompson used as the cornerstone of his book Last Second in Dallas.

So, this is clearly the most complete and in-depth compendium with which to measure the quality and comprehensiveness of the HSCA public hearings. On top of that the author includes four appendices, one on Howard Brennan, one on Sylvia Odio—neither of whom testified in public for the HSCA—one on the photographic puzzle called Black Dog Man and the last is on Life’s three versions—during which they broke the presses at great expense—of its photo essay for their October 2, 1964 issue. The last two pieces were written by Martin Shackleford and John Kelin.

As per Brennan, he simply refused to testify before the committee. Under any circumstances. (Honest Answers by Vince Palamara, pp. 186-89) And Tim is at pains to show why he would not, even under subpoena. Why the HSCA would even want him to appear is kind of puzzling.

According to Gaeton Fonzi, Odio was willing to testify about the visit to her Dallas apartment by Oswald, or his double, just a few weeks before the assassination. But she was eliminated from the agenda at the last minute for nebulous reasons. (Fonzi, The Last Investigation, pp. 258-59) Gaeton ends his fine book by saying she was now willing to testify in public and on TV—after being reluctant for many years—because she was frustrated. She was angry because the truth had been bottled up by forces she could not understand, yet she felt powerless to counteract. When Fonzi told her the HSCA would not call her for televised public testimony, she replied with, “We lost. We all lost.”

Smith has written a worthy and unique book that continues the excavation of why the House Select Committee—which Fonzi called the last investigation—ended up as disappointing as it was.

-

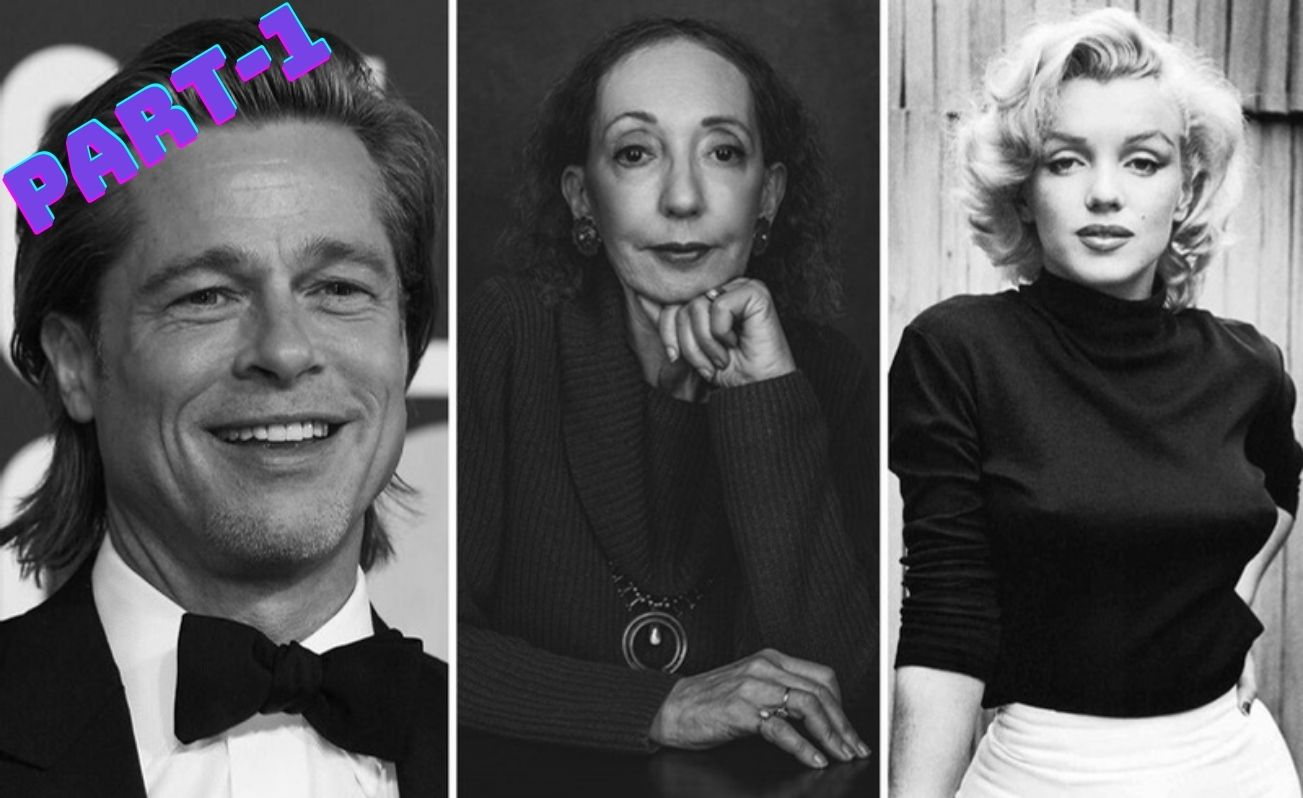

Brad Pitt, Joyce Carol Oates and the Road to Blonde: Part 2/2

As noted in Part 1, although Robert Slatzer was an utter and provable fraud, he clearly had an influence in the Marilyn Monroe field. People like Anthony Summers and Donald Wolfe used him quite often in their tomes. He influenced Fred Guiles also. In the revised version of his first book on Monroe—entitled Legend and published in 1984—he now seems to abide by the Slatzerian myth that Bobby Kennedy was having an affair with Monroe which President Kennedy encouraged. (pp. 24-25, reference on p. 479) This angle is absent from his first Monroe biography, Norma Jean, published in 1969. But it’s Guiles’ second book that Oates references in her notation section for Blonde. Summers also accents this RFK angle. And he uses a woman that Slatzer also used in his second book, The Marilyn FIles (1992). That woman was the late arriving Jeanne Carmen —who was nowhere to be seen prior to the eighties.

I

As Don McGovern astutely points out, it is quite revealing that Slatzer does not mention Carmen in his first book, published back in 1974. What makes this odd is that Slatzer claimed a years-on-end relationship with Monroe as her best male friend. Carmen claimed the same as her best female friend. Yet they never crossed paths? (McGovern, p. 131). This is a key point because as both Sarah Churchwell and McGovern comment, Carmen created most, if not all, the wild stories about Monroe’s alleged affair with the Attorney General. (McGovern, p. 132; Churchwell, The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe, p. 293) Carmen also was influential in bringing the Mob into the Monroe field i.e. Johnny Roselli and Sam Giancana.

But from the very beginning of her story, Carmen presents a plethora of problems that recall Slatzer. But, like Slatzer, she got a lot of exposure—31 TV appearances —for a very problematic witness. For instance, she says in her posthumously published book that she met Monroe at a bar near the Actor’s Studio in New York in the early fifties. But yet, as April VeVea points out, the first time Monroe met anyone connected to the Actor’s Studio was in late August of 1954 on the set of There’s No Business Like Show Business. Monroe then met stage producer Cheryl Crawford who introduced her to Actor’s Studio impresario Lee Strasberg. But this was in 1955 and that is when she enrolled in the famous school. Up until that point, Monroe relied on acting coach Natasha Lytess. (VeVea, “Classic Blondes”, 4/9/18)

In the tabloid, Globe Carmen said she and Marilyn attended a pool party at Peter Lawford’s during the Democratic Convention of 1960 in LA. (1/17/95) Again, quite dubious, since Monroe was in New York at the time. (McGovern, p. 148)

But the wildest, nuttiest stories that Carmen was responsible for were the associations between Monroe and the Mob. As VeVea noted in her posting, Carmen actually said that Sam Giancana was murdered by Roselli—over Marilyn! According to Carmen, right before he shot him Johnny said, “Sam, this is for Marilyn.” Which is preposterous. No responsible author on the Giancana case has ever intimated any such thing e.g. William Brashler or Bill Roemer. (Click here for an overview of Giancana) As VeVea notes there is no photographic evidence of any such Mafia association by Marilyn, no evidence of this in her address or phone logs, and no credible biography has ever had Monroe associated with any mobsters. But not only did Carmen know that Marilyn and Giancana were intimate, she even knew how Giancana fornicated with her. (For the prurient reader it was “doggie style”.)

But if you can comprehend it, Carmen then got even wilder. She later told David Heymann that she herself had an affair with President Kennedy. (Icon, Part 1, p. 64) She also said that her apartment was ransacked the evening of Monroe’s death. Fred Otash then walked in and threw her to the floor. He pointed a gun at her and pulled the trigger, but it did not go off. He told her Giancana had Marilyn murdered by a team of assassins. They wanted to kill Carmen also, but he persuaded them not to do so. And, by the way, one of Sam’s four man hit team anally raped Eunice Murray. (McGovern, pp. 498-99).

It is difficult to even write these things without suppressing a combination of laughter and disbelief at the circus the field had become. Yet these are the kinds of people who occupy the pages of Goddess (p. 238), and Slatzer’s The Marilyn FIles (pp. 30-33). For the record, Gary Vitacco Robles, Randy Taraborrelli and Don McGovern all agree that there was no romantic or sexual relationship between Monroe and RFK.

II

Before getting to the novelization of Monroe by Joyce Carol Oates, I would like to deal with two more stories about her death which many people also find dubious. First from a man named Jack Clemmons who was the first responding officer to arrive at Monroe’s home the night she passed. As April VeVea shows on her site, Clemmons was, to be frank, a dirty cop. (See Marilyn: A Day in the Life, “Jack Clemmons”.) Clemmons was another rightwing fanatic who let his ideology color his duties, or as his supervisor said, “His outside political interests distracted from his job interest.” (Icon, Vol. 2, p. 189) Predictably, he was close to the other rightwing extremist Frank Capell. As VeVea notes, Clemmons told Summers that Eunice Murray was using the washer/dryer on the sheets when he arrived. This was his first whopper. Because as Gary Vitacco Robles and Don McGovern show, and VeVea notes, Monroe did not have this unit, she sent everything out. He also said that he thought Monroe’s dead body was posed since drug overdose deaths usually end in convulsive spasms. (Slatzer, The Marilyn Files, p. 5) This is also not true, as pathologist Dr. Boyd Stephens told assistant DA Ron Carroll’s threshold inquiry in 1982. (Icon, Vol. 2, p.320) Clemmons told Slatzer that there was no drinking glass in Monroe’s bedroom. This was another whopper, as police photos from the scene showed there was one at the base of the nightstand. (McGovern, p. 547). Anyone can figure what Clemmons was doing by painting this false scenario. As McGovern notes, Clemmons had little problem corrupting the truth, and as Don points out, he did it in more than once instance.

Finally, there is a former wife of Lawford. She said that Lawford went to Monroe’s house after her death to remove evidence of her association with the Kennedy family. (Icon, Part 1, p. 401; Summers pp. 361-62)

The reason many people find this wanting is that the story did not surface until decades after Monroe’s death, from a wife who was not married to Lawford until 1976. And, according to Vitacco-Robles, they separated after 2-3 months of marriage. (Ibid) Yet all the witness testimony and evidence from the time—that is in 1962—conflicts with this visit happening. In fact, when one follows that testimony a quite different picture emerges.

On the day she died, Lawford had invited Monroe to a dinner party at his home in Santa Monica. The guests there were talent manager George Durgom, and TV producer Joe Naar and his wife Dolores. (Icon, Pt. 1, p. 394). Lawford invited Monroe to this gathering but she ended up declining since she said she was tired. Lawford was worried because of the tone of her voice: she sounded despondent, her voice was slurred and he knew she had a drug problem. He tried to call back but could not get through. He then called his agent Milton Ebbins and told him to call Monroe’s attorney Milton Rudin. This resulted in a call to Eunice Murray who—not knowing about Monroe’s slurred tone to Lawford — said Monroe was alright. (Icon, Part 1, p. 398, p. 403) Even after he was notified of this, Lawford still wanted to check on Monroe himself; but Ebbins said Murray would tell him the same thing. Reluctantly, and arguing with Ebbins in still a later call, Lawford did not go. According to Ebbins, Lawford felt horrible about not trusting his instincts. It turns out that Ebbins had a hidden agenda. He knew that Monroe was a pill addict and therefore how bad it would look if his client, the president’s brother-in-law, was at her home when paramedics had to be called.

There are about six corroborating witnesses to this, and Vitacco-Robles uses them all. Ebbins said that later, since he felt guilty, Lawford talked to Dr. Greenson about it. Greenson told the actor that this was just the most recent of five attempts by Monroe. No one could help the woman. (ibid, p. 408). Ebbins told Tony Summers that Lawford never mentioned the Attorney General during that evening, or after he told him she was dead. He concluded with: “If anyone thinks Marilyn killed herself over either one of the Kennedys, they’re crazy, they are absolutely insane.” In a long and comprehensive analysis which he ends by quoting this dialogue, Vitacco-Robles points out that Summers did not include this interview in his 2022 Netflix special about Monroe’s death. (ibid, p. 413)

III

With a menagerie like the above, the Summers/Slatzer/Wolfe axis resorted to cries of an official cover up in the Monroe case. For instance, Summers once wrote that the Ronald Carroll inquiry of 1982 did not even interview the first detective at the scene. According to Vitacco-Robles, they did interview Det. Byron who was the detective in charge. One of the things he told them was that there was no credible evidence that RFK was in LA that day. (Icon, Pt. 1, p. 393) If Summers means Clemmons, they talked to him also. (Icon Part 2, p. 184). In fact, they also talked to the con artist Slatzer, who Summers found so bracing. (ibid, p. 108) The difference being that questioners like attorney Carroll, and professional investigators Clayton Anderson and Al Tomich knew what standards meant in these types of investigations. And they understood how worthless witnesses like Slatzer and Clemmons would be before a grand jury. With people like Lionel Grandson one would be edging into the area of comedy. Grandison was a clerk in the coroner’s office who was fired for forgery and stealing credit cards from corpses. (Ibid, p. 211) This ended up being part of a ring to buy auto parts and he was later found guilty in court. It turned out that his eventual story about discovering Monroe’s diary was influenced by a meeting with Robert Slatzer. (ibid, p. 208) When asked to take a polygraph exam by Tomich he initially agreed but then backed out. He needed a lawyer’s advice.(ibid) As I have noted, Monroe did not have a diary. It was a notebook, which was not discovered until much later.

Another aspect of the “cover-up” was the story that Police Chief William Parker seized the Monroe phone records and hid them since Bobby Kennedy had promised to make him head of the FBI. It turns out that the LAPD did have her phone records and they investigated them, and so did the Carroll inquiry. The calls made to the Justice Department went through the main switchboard. (Icon, Part 2, p. 592) The reason for these calls was very likely Monroe wanting Bobby Kennedy to help her in her dispute with Fox studios which had fired her over her absence from the set of Something’s Got to Give. There are both documents and credible testimony—from publicist Rupert Allan—on this point. (Ibid, p. 535)

But Robert Slatzer never stopped crying cover up. Not happy with the results of the Carroll probe—which could find no reason for a new inquiry —he now tried to manipulate a grand jury into reopening the Monroe case. To put it mildly, the other jurors did not agree. They requested that Sam Cordova—the juror who Slatzer was working through—be removed. Superior Court Judge Robert Devich agreed to the request. (UPI story of October 29, 1985, by Michael Harris.). Then there was Roone Arledge at ABC News. He vetoed a 20/20 story that Geraldo Rivera and Sylvia Chase were promoting based on Summers’ book with Slatzer as a consultant. Arledge said it was “gossip column” stuff. (ibid) He was correct but maybe too kind. April VeVea has been more frank and calls Goddess an atrocious book. (VeVea, op. cit.). In his acknowledgements, Summers praised attorney Jim Lesar for attaining valuable FBI documents. But Randy Taraborrelli, who wrote a later biography, said the contrary. He said that the FBI files on Monroe were fascinating because they are just so untrue; they do not hold up to modern journalistic analysis. He concluded that J. Edgar Hoover had such animus against the Kennedys “that I think that he allowed a lot of information to be put into those files that just was not true.” (McGovern, p. 351)

The above was what Joyce Carol Oates was working with when she arrived on the scene. She was going to do a roman a clef novel based on five books about Monroe. Three of them were Guiles’ Legend, Summers’ Goddess, and Marilyn, by Norman Mailer. But after reading Blonde, she seems to have gone to even further extremes than these men.

IV

Blonde has been filmed twice. The first version was aired by CBS in 2001, just a year after the book’s publication. That two-parter was directed by Joyce Chopra, and starred Poppy Montgomery as Marilyn. It landed a cover story for TV Guide. Chopra once made a good film, Smooth Talk in 1985. The picture was produced by Robert Greenwald, who is supposed to be an intelligent and discerning man and who I once talked to. The combination of the two make the dull and disappointing result a bit surprising.

But considering the source material, perhaps that was inescapable. As Sarah Churchwell noted in her study of the field:

As we shall see, biographies about Marilyn Monroe have a very problematic relationship to fiction. Although biography depends upon an implicit contract with the reader that documented fact is being accurately represented, in Monroe’s case this obligation is rarely, if ever met. (Churchwell, p. 69)

Well, what happens if one takes it a step further and one makes a novelization of some of these books? As Churchwell notes about Oates: there are no entirely fictional major characters in the book. For example, The Playwright is obviously Arthur Miller, her third husband; Bucky Glazer is James Dougherty, her first husband. As she also observes, the portrait of Monroe drawn by Oates is so one dimensional that its artificial. Instead of an archetype we get a stereotype. She specifically writes about Oates, “Someone who skims across the surface of a life should not be surprised to find superficiality.” (Churchwell, pp. 120-21). Or as reviewer Michiko Kakutani wrote about the book:

Now comes along Joyce Carol Oates to turn Marilyn’s life into the book equivalent of a tacky television mini-series…Playing the reader’s voyeuristic interest into a real-life story while using the liberties of a novel to tart up the facts. (ibid)

In fact, one cannot fully blame the excesses of the more recent version of Blonde

on Dominik and Pitt. Because, as Churchwell notes: 1.) the book depicts Daryl Zanuck sodomizing Monroe in his office 2.) a year’s long menage a trois affair between Monroe and the sons of Charlie Chaplin and Edward G Robinson and 3.) her sexual tryst with President Kennedy at the Carlyle Hotel in New York via Secret Service agents. (Churchwell, pp. 120-23; Oates, pp. 699-708)

And she continues:

Oates’ Blonde is one of the most gratuitously conspiratorial of all the Monroe texts, positing as it does a voyeuristic sniper/spy/spook who is at once an aberrant acting alone and the puppet of a governmental plot: the more fictional the take, the more it can toy with the pleasure of a conspiratorial ‘solution” to the mystery. (Churchwell, pp. 317-18)

What Oates does here is to call this assassin a sharpshooter but he actually kills Monroe via hypodermic. (Oates, p. 737) As Churchwell points out, titling him a sharpshooter is clearly meant to recall the murder of John Kennedy.

But even before that, Oates actually suggests that Monroe had a secret tryst with Achmed Sukarno of Indonesia for the Agency. (p. 735). With this kind of junk as part of the source material, what chance did these two films have? Not much, but they really did not try very hard to counter the excesses of Oates.

The first version is not quite as offensive. Since it was a network broadcast it could not be as explicit as the Pitt/Dominik version. But still, overall, it’s a quite mediocre effort, both as written and as directed. The one exceptional aspect of the film is Ann Margaret’s performance as Marilyn’s grandmother. Everything else is pretty prosaic, and this includes the acting of Montgomery as Monroe and Griffin Dunne as Arthur Miller.

Because of the lowbrow nature of the book, both films deal with the three-sided relationship that allegedly went on for years between Monroe, Chaplin III and Robinson Jr. Monroe authority Don McGovern read both of their books. Chaplin said he only went out with Norma Jean Baker (Monroe’s real name) early in her career. The relationship did not last once she ascended into the film world. (My Father, Charlie, Chaplin, p. 250) In Robinson’s book he never notes that he was romantically involved with Monroe. (My Father, My Son, Chapter 29) McGovern asks just how did this all materialize then? Because, according to Summers, Chaplin actually impregnated Monroe back in 1947 and she got an abortion. (Email of 2/11/23) The problem with this is that, according to her gynecologist, Leon Krohn, Marilyn never had an abortion. Yet both films, borrowing from Oates, play this threesome up to the hilt—and beyond. And both films show Monroe getting an abortion. In the Dominik version the CGI fetus actually talks to Monroe and blames her for getting past abortions! Talk about a cartoon.

Both films begin with Monroe’s childhood relationship with her mentally unbalanced mother. How Gladys was so unstable that she had to be institutionalized and young Norma Jean was taken to an orphanage. (I should note here, the one exceptional aspect of the Dominik film is Lily Fisher’s convincing performance as the child Baker.). One major difference between the two is that Dominik’s film cuts almost everything that happened afterwards out — until Monroe started her Blue Book modeling career under Emmeline Snively. It then jumps to producer Daryl Zanuck and agent Johnny Hyde and we are rather quickly in the movie business.

Both films use the Chaplin/Robinson nexus, and the Dominik film is pretty explicit about it. In both films her “abortion” causes her great psychic pain which the directors use as fantasy scenes to recall painful memories from her childhood, like sleeping in a dresser drawer. In both films the marriage to Joe DiMaggio is dealt with briefly and both include the passing of nude pictures of Marilyn to the athlete, and this precipitates serious problems—physical violence — in the ten-month marriage.

Both films shift to Marilyn in New York trying to get away from Hollywood. Which leads to her meeting with Arthur Miller and taking classes at the Actor’s Studio. The Dominik film is much more explicit about her drug, pill and alcohol excesses. And her erratic behavior on film sets, the latter actually has her driving into a tree.

The first film has her mentioning her “talks” with President Kennedy, if you can believe it, about Fidel Castro. The second film follows Oates in that it has her taking a plane ride back east, and she is escorted into a hotel room with JFK laying down in bed talking to J. Edgar Hoover, who is relaying him information about rumors of his affairs. There, after walking by a dozen people, she performs fellaltio on Kennedy while he is on the phone. To say this scene did not occur is putting it too mildly—it’s out of an Arthur Clarke novel.

The first film ends with her singing performance of Happy Birthday to Kennedy at Madison Square Garden, leaving out the fact that there were 17 other performers there that night. The second film ends quite differently. It has Monroe being transported back to California after saying words to the effect, it was not just sexual. Alone in her home, Eddie Robinson calls to tell her Chaplin is dead. She gets a package that tells her that it was Chaplin writing letters from her father, who many think she never met. She starts taking pills, and the last scenes we see are the phone off the hook and her having a fantasy about her father. The camera pulls back from the bed and her dead body; fade to black.

I should add, the Dominik film transitions from color to black and white quite often. And, for this viewer, I could not really figure any kind of logical or aesthetic scheme for it. Perhaps Mr. Dominik will call me and explain it.

V

The reaction to the Pitt/Dominik version was rather strongly negative. In fact, some called the film “unwatchable”. They could not view it for even 20 minutes. Critic Jessie Thompson called it degrading, exploitative and boring, while adding it had no idea as to what it was trying to say. Some commentators called it a “hate letter” to Monroe. Another begged: please leave Marilyn alone. (9/30/22, story by Louis Chilton, The Independent.)

This is all quite justifiable about both films, but especially the second one. One has to wonder, did Pitt even read the script? I actually hope he did not. Since I think he is a brighter guy than to agree to such a ridiculously reductive film that is simply a caricature of both Monroe’s life and the woman herself. As Sarah Churchwell wrote, Dominik promoted his picture by saying that Monroe’s films are not worth watching. (The Atlantic, 10/21/22). Which is very odd since most critics consider Some Like It Hot to be one of the best American comedies of the sound era. About her modeling career, Emmeline Snively said:

She started out with less than any girl I ever knew. But she worked the hardest. She wanted to learn, wanted to be somebody, more than anybody I ever saw before in my life. (ibid)

As Churchwell adds, Monroe studied literature at UCLA at night, she really wanted to be a good actress, she supported racial and sexual equality, she despised McCarthyism and protested the House Un-American Activities Committee. Further, she disliked Richard Nixon who she called cowardly, and did not like Mailer because he was too impressed by power; she added you could not fool her about him. She admired the Kennedys because of their progressive agenda. She once even asked Robert Kennedy about his civil rights program vs Hoover. (Icon, Pt. 2, p. 565). But it is this Monroe who is now forgotten due to the likes of Oates and Dominik.

The first film of Oates does not really deal with the circumstances of her death, while the second tries to say her house was being monitored for sound at that time. This is another urban legend which VItacco Robles has cast severe doubt upon. (Ibid, Chapter 24). With the work of Don McGovern and Gary VItacco Robles we can now see her tragic demise a lot more clearly. All of the sound and fury created by Slatzer and his followers served to disguise the fact that her death was really a harbinger. One that looked forward to the Elvis Presley and Michael Jackson cases.

Slatzer did not give one iota about the true facts of her death. To him she was a meal ticket. The amount of drugs that were available to her in the last two months of her life are simply staggering. (ibid, pp. 452-457). And it’s clear that she had additional suppliers besides her own doctors e.g. Lee Siegel for one. The total amount is well over 800 pills. Which comes to over 13 pills per day. The combination of Nembutal (47) and Chloral hydrate (17) is what killed her, and these were ingested not injected, as pathologist Dr. Boyd Stephens described to Ronald Carroll. (McGovern, pp. 494-95, see also Icon Part 2, p. 620) As mentioned, she had tried to end her life 4-5 times previously. The most recent attempt being about ten months prior to August of 1962. (Icon, pt. 2, p. 443)

As seems clear from the evidence, Dr. Engelberg lied about his prescriptions to Monroe, perhaps to cover up his own culpability. And Siegel’s prescriptions were not covered by the coroner’s office. (ibid, p. 458) Another illustrious pathologist, Cyril Wecht, agreed with all this. He dispelled certain disinformation about the autopsy spewed by Slatzer; saying for example that no, Nembutal does not leave a dye color, and that drugs dissolve much faster than food in the stomach, so the lack of dye and the stomach being empty was not at all odd. (Icon, Part 2, p. 351)

But he further added that the amount of drugs Engelberg supplied were simply “out of the ballpark”. He also ridiculed the statement by Engelberg that he was weaning her off drugs. He then delivered the capper:

I believe that he well could have been charged. It would be manslaughter. It could rise to third degree murder. But certainly manslaughter. Think about Conrad Murray in the Michael Jackson case….That is feeding an addiction…If it occurred today, a district attorney would make a move due to a celebrity involved and quantity of drugs involved. (ibid, p. 361)

Wecht also disagreed with the combination of Nembutal and chloral hydrate. He did not think she should have been given both. When asked why her doctors were not charged, Wecht replied it was a different world back then and the media was much more quiet. He concluded by saying that he agrees with Thomas Noguchi’s finding, and the 1982 Ronald Carroll review: “I see no credible evidence to support a murder theory.” (Ibid, p. 367) When one has three pathologists the stature of Noguchi, Stephens and Wecht, with that much experience, I will take them any day over the likes of Slatzer, Mark Shaw and their ilk.

Let me end with two quotes that sum up the Marilyn Monroe case and its aftermath. The first is by the estimable Don McGovern:

While the initial motivation to engage in The Kennedys-Murdered-Marilyn farrago was a political one, it quickly transmogrified into a financial one, most certainly influenced, arguably even fomented by the financial success of Norman Mailer and Lawrence Schiller. There is little doubt that money motivated Robert Slatzer and Jeanne Carmen along with the obvious fact that both were camera and fame whores. (Icon, Vol. 2, p. 32)

I don’t think one can get more accurate than that about what has become a continuous cesspool of character assassination. Therefore, let us give Marilyn, the victim of this constant calumny, the last word; since the public seems to prefer the voices of Oates and Slatzer to the real person.

What I really want to say: that what the world really needs is a new feeling of kinship. Everybody: stars, laborers, Negroes, Jews, Arabs. We are all brothers…Please don’t make me a joke. End the interview with what I believe. (Marilyn Monroe, Graham McCann, p. 219)

Maybe that quote is how we should remember her.

Go to Part 1 of 2

-

Brad Pitt, Joyce Carol Oates and the Road to Blonde: Part 1/2

How did the recent movie version of the Joyce Carol Oates novel Blonde ever materialize? A big part of the answer is Brad Pitt. The actor/producer had worked with film director Andrew Dominik on the 2007 western The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and again on the 2012 neo noir crime film, Killing Them Softly. It was around the time of the latter production that actor/producer Pitt decided to back Dominik in his attempt to make a film about Marilyn Monroe, based upon the best-selling Blonde, published in 2000. (LA Times, 6/3/2012). Pitt also showed up at the film’s premiere at the Venice Film Festival in September of 2022 to support the picture.

Blonde is the first film with an NC-17 rating to be streamed by Netflix. No film submitted to the Motion Picture Association of America had received such a rating since 2013. (Time, September 9, 2022, story by Moises Mendez) After watching the film I can understand why, and its surprising that Netflix even financed the picture. Some commentators believe it was through the powerful status of Pitt that the film ultimately got distributed. But before we get to just how poor the picture is, I think it necessary to understand how the American cultural scene gave birth to a production that is not just an unmitigated piece of rubbish but is, in many ways, a warning signal as to what that culture has become.

I

By the time Oates came to write her novel, the field of Marilyn Monroe books and biographies was quite heavily populated. After Monroe’s death in 1962, the first substantial biography of Monroe was by Fred Lawrence Guiles entitled Norma Jean, published in 1969. Norman Mailer borrowed profusely from Guiles for his picture book, Marilyn, released in 1973. Originally, Mailer was supposed to write an introductory essay for a book of photos packaged by Lawrence Schiller. But the intro turned into a 90,000 word essay. Mailer included an additional chapter, a piece of cheap sensationalism which he later admitted he had appended for money. In that section he posited a diaphanous plot to murder Monroe by agents of the FBI and CIA due to her alleged affair with Attorney General Bobby Kennedy. (Sixty Minutes, July 13, 1973). Because the book became a huge best-seller, as John Gilmore pungently noted, it was Mailer who “originated the let’s trash Marilyn for a fast buck profit scenario.” (Don McGovern, Murder Orthodoxies, p. 36)

Mailer inherited his flatulent RFK idea from a man named Frank Capell. Capell was a rightwing fruitcake who could have easily played General Ripper in Dr. Strangelove. In August of 1964, Capell published a pamphlet entitled The Strange Death of Marilyn Monroe. It was pure McCarthyite nonsense written solely with a propaganda purpose: to hurt Bobby Kennedy’s chances in his race for the senate in New York. Capell was later drawn up on charges for conspiracy to commit libel against California Senator Thomas Kuchel. (Chicago Tribune, February 25, 1965) This was not his first offense, as he had been indicted twice during World War 2 for accepting bribes while on the War Production Board. (NY Times, September 22, 1943). Capell did not like Kuchel since he was a moderate Republican who was backing Bobby Kennedy’s attempt to get his late brother’s civil rights bill through congress. Which tells the reader a lot about Capell and his poisonous pamphlet.

The next step downward involves Mailer, overtly, and Capell, secretly. I am referring to the materialization of a figure who resembled the Antichrist in the Monroe field, the infamous Robert Slatzer. Slatzer originally had an idea to do an article about Monroe’s death from a conspiratorial angle before Mailer’s 1973 success. He approached a writer named Will Fowler who was unimpressed by the effort. He told Slatzer: Now had he been married to Monroe that would make a real story. Shortly after, Slatzer got in contact with Fowler again. He said he forgot to tell him, but he had been married to Monroe. (The Assassinations, edited by James DiEugenio and Lisa Pease, p. 362)

The quite conservative Fowler then cooperated with Slatzer through Pinnacle Publishing Company out of New York. Capell was also brought in, but due to his past legal convictions, his cooperation was to be secret. (Notarized agreement of February 16, 1973). The best that can be deciphered through the discovery of the Fowler Papers at Cal State Northridge is this: Capell would contribute material on the RFK angle through his files; Slatzer would gather and deliver his Monroe personal letters, mementoes, and marriage license; and Fowler would write the first draft, with corrections and revisions by the other two. (McGovern, pp. 90-91)

But in addition to Capell’s past offenses, another problem surfaced: Fowler soon concluded that Slatzer was a fraud, so he withdrew from the project. (LA Times, 9/20/91, article by Howard Rosenberg). The main reason Fowler withdrew is that Slatzer could not come up with anything tangible to prove any of his claims about his 15-year-long relationship, or his three day marriage, to Monroe. Several times in the Fowler Papers it is noted that Slatzer’s tales changed over time “as they also veered into implausibility”. As a result, Fowler started to question his writing partner’s honesty. (McGovern, p. 79) Consequently, other writers were called in to replace Fowler, like George Carpozi.

II

The subsequent book released in 1974 was entitled The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe. To my knowledge, it was the first book published by an alleged acquaintance of Monroe to question the coroner’s official verdict that Monroe’s death was a “probable suicide”.

Whatever unjustified liberties Capell and Mailer took with the factual record, Slatzer left them in the dust. In addition to his –as we shall see– fictional wedding to Monroe, Slatzer also fabricated tales about forged autopsy reports, 700 pages of top-secret LAPD files, hidden Monroe diaries, inside informants, and perhaps the wildest whopper of all: a secret deposition by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. If ever there was a book that violated all the standards of both biography and nonfiction literature it was The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe. It was a no holds barred slander fest of both Monroe and Robert Kennedy.

Slatzer claimed that he and Marilyn went to Tijuana, Mexico on October 3, 1952 and were married there on October 4th. After returning to LA, they had second thoughts about it, and they went back and got the proceeding annulled; actually the attorney who did the service just burned his certification document on October 6th. This tall tale has been demolished by two salient facts. First, there is documented proof produced by author April VeVea that Monroe was at a party for Photoplay Magazine on October 3rd. (See VeVea’s blog for April 10, 2018, “Classic Blondes”.) Secondly, Monroe wrote and signed a check while on a Beverly Hills shopping spree on October 4th. The address on the check is 2393 Castilian Dr., the location in Hollywood where she was living with Joe DiMaggio at the time. Monroe authority Don McGovern has literally torn to pieces every single aspect of Slatzer’s entire Mexican wedding confection. (McGovern, pp. 49-67, see also p. 100)

Just how far would Slatzer go to string others along on his literary frauds? How about paying witnesses to lie for him? Noble “Kid” Chissell was a boxer and actor. According to Slatzer, he happened to be in Tijuana and acted as a witness to his Monroe wedding. Years later, when asked about it, Chissell recanted the whole affair to Marilyn photographer Joseph Jasgur. He said that there was no wedding between Slatzer and Marilyn. He went further and said he did not even think Slatzer knew Monroe. But Slatzer wanted Chissell as a back-up to his phony playlet and promised to pay him to go along. Which, by the way, he never did. Which makes him both a liar and a welsher. (McGovern, pp. 98-99). It also appears likely that Slatzer forged a letter saying that Fowler had actually seen the Slatzer/Monroe marriage license and Fowler met Monroe while with him. Fowler denied ever seeing such a document or having met Monroe. (McGovern, p. 81)

III

One would think that The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe could hardly get any worse. But it does. To add a layer of official intrigue inside the LAPD, Slatzer created a figure named “Jack Quinn”. Quinn had been an employee of LA County and he got in contact with Slatzer and informed him of a malignant cover up about the Monroe case inside City Hall, particularly the LAPD. (Slatzer, pp. 249-53) The enigmatic Mr. Quinn described a secret 723 page study of the Monroe case. That study stated that the original autopsy report had been deep sixed. Further, that Bobby Kennedy had been in LA at an official opening of a soccer field on August 4, 1962 and he had given a deposition in the case. In that deposition he said that he and his brother-in-law, Peter Lawford, had been at Marilyn’s house and they had a violent argument, to the point he had to bring in a doctor to inject her to calm her down.

The above is why I and others consider Slatzer’s work a milestone in trashy tabloidism: the forerunner to the manufactures of David Heymann. The only thing worse than writing that RFK would submit to such a legal proceeding is postulating that the LAPD would have any reason to question him. In their official reporting, the first three people at Monroe’s home all said that Monroe was alone in her bedroom when she passed. This included her housekeeper Eunice Murray, her psychiatrist Robert Greenson, and her physician Hyman Engelberg. Engelberg made the call to the LAPD saying that she had taken her own life. (LA Times, 12/21/2005, story by Myrna Oliver) Later in this essay, I will explain why, if anyone should have known the cause of death, it was Engelberg.

But complementary to this, Robert Kennedy was nowhere near Brentwood–where Monroe lived–at this time. Sue Bernard’s book, Marilyn: Intimate Exposures proves this beyond doubt, with hour by hour photographs and witness testimony. (pp. 184-87; see also, Gary Vitacco-Robles’ Icon, Pt. 2, p. 82) In fact, in his book Icon, VItacco Robles documents Bobby Kennedy’s four days in the Gilroy/San Francisco area from August 3-6th. (See Icon Part 2, pp. 82-83). Therefore, at both geographic ends, Slatzer’s “secret RFK deposition” is pure hogwash, an invention out of Capell.

In 1982 Slatzer opined in public at the Greater Los Angeles Press Club that the Monroe case should be reopened. The DA’s office began a threshold type inquiry to see if there was just cause to do a full reopening. That inquiry was run by assistant DA Ron Carroll with investigators Clayton Anderson and Al Tomich (Icon Pt. 2, p. 108) They interviewed Slatzer about his “Quinn” angle. Very soon, problems emerged with his story. Allegedly, Quinn called Slatzer in 1972, saying he worked in the Hall of Records building and he had the entire 723 page original record of the case. He said he was leaving his position to move to San Mateo for a new job. Slatzer said he met Quinn, who had a badge on with his name, at Houston’s Barbeque Restaurant. Slatzer gave him 30 dollars to copy the file. Quinn said he would meet him at the Smokehouse Restaurant in Studio City for delivery. Quinn added that he lived in the Fair Oaks area of Glendale.

Quinn did not show up. Slatzer went to the Hall of Records and found no employee by the name of Quinn, which should have been predictable to Carroll because The Smoke House is not in Studio City, it’s in Burbank. And Fair Oaks is a popular boulevard going from Altadena through Pasadena to South Pasadena, but not Glendale. Slatzer now added something just as sensational. Ed Davis, LA Chief of Police, flew to Washington a month later to ask questions about RFK’s relationship with Monroe. (Was this the secret deposition?) Davis replied that no such thing happened. (Icon, Pt. 2, p. 110) When Carroll began to go through databases of City Hall employees from 1914-82, he could find no Jack Quinn. He also found out that the files of the LAPD would, in all likelihood, not be stored at the Hall of Records. Like his Tijuana wedding, Slatzer’s “Jack Quinn” was another fictional creation from a con artist.

With Carroll, Slatzer also tried to insert two other phony “clues”. First, that there was a three hour gap between when Monroe’s doctors were summoned and when the call to the police was made. Carroll discovered that the original LAPD inquiry by Sgt. Byron revealed that it was really more like a 45 minute delay. Eunice Murray did not call the doctors until about 3:30 AM. (Icon, Pt. 2, p. 110)

Slatzer also tried to question the basis of Murray’s initial suspicions of something being wrong with Marilyn. In the original investigation, Murray told Byron that what puzzled her was the light being on in Monroe’s room through the night. She noticed this at about midnight but was not able to awaken Monroe. She then noticed it again at about 3:30 AM and this is when she made a call to Dr. Greenson. (Icon. Vol. 1, p. 278) Slatzer said this was wrong since the high pile carpeting prevented light being seen under the door. It turned out—no surprise– that this was another of Slatzer’s whoppers. With photos and witness testimony, Vitacco-Robles proves that one could see light under the door, and further there were locking mechanisms on the doors. (Icon, Pt. 1, p. 255, p. 380) Slatzer wanted to disguise this fact because it indicates that Monroe ingested the pills, 47 Nembutals and 17 chloral hydrates, and then slowly lost consciousness and slipped into a coma, in spite of the light being on—which normally she was quite sensitive to.

I could go on and on about Slatzer’s malarkey. For instance, both Vitacco-Robles and Slatzer’s former wife clearly think that the whole years long Monroe relationship Slatzer writes about in his book is balderdash. Gary advances evidence that from 1947-57, Slatzer was not cavorting around LA with Monroe but lived in Ohio. (Icon, Vol. 2, p. 119) Slatzer’s Ohio wife, Kay Eicher, said Slatzer met Monroe exactly once, on a film set in Niagara Falls where Monroe—always kind to her fans- posed with him for impromptu pictures. She added about her former husband, “He’s been fooling people too long.” (ibid, p. 123) Which Slatzer also did with Allan Snyder, Monroe’s makeup artist. This again was supposed to show he knew Monroe. But Snyder later said he never heard of the man while Marilyn was alive. Slatzer just approached him to write up an intro and paid him for it. (ibid, p. 126)

The reason I have spent a bit of time and space on slime like Slatzer is simple. If a figure like Slatzer had surfaced in the JFK critical community, his reputation would have been blasted to pieces in a week. But back in 1974, there was no such quality control in the Monroe field. Therefore, not only was his book a commercial success, he then went on to write another book, and marketed two TV films on the subject. But beyond that—and I wish I was kidding about this–Slatzer had a wide influence on the later literature. It was not until much later, with the arrival of people like Don McGovern, Gary Vitacco-Robles, April VeVea and Nina Boski that any kind of respectable quality control developed in the field.

IV

In the October, 1975 issue of Oui magazine, Tony Sciacca, real name Anthony Scaduto, wrote an essay called “Who Killed Marilyn Monroe.” That article was expanded into a book the next year, Who Killed Marilyn? This book owes much to Slatzer. Including lines and scenes seemingly pulled right out of his book. For example Monroe says that Bobby Kennedy had promised to marry her. ( p. 13). Another steal is Monroe’s red book diary. Where she wrote that RFK was running the Bay of Pigs invasion for his brother. (pp. 65-69). The idea that Bobby Kennedy was going to divorce his longtime wife Ethel, leave his eight children, resign his Attorney General’s position, and forego his future chance at the presidency—all for a woman he met socially four times—is, quite frankly, preposterous. Further, as the declassified record shows, Bobby Kennedy had nothing to do with managing the Bay of Pigs operation. That was being run by CIA Director of Plans Dick Bissell, along with Deputy Director Charles Cabell. (See, for example, Peter Kornbluh’s Bay of Pigs Declassified.) And it turns out that Monroe had no red book diary. What she kept were more properly called journals or notebooks which were found among her belongings decades after she died. These were then published under the title Fragments. And they contain nothing like what people like Slatzer, Scaduto, and later Lionel Grandison, said was in them. (McGovern, pp. 268-71)

But incredibly, Slatzer lived on in the writings of Donald Wolfe, Milo Speriglio and Anthony Summers. Summers’ 1985 book Goddess became a best-seller. In the introductory notes to the Oates’ novel, she names Goddess as one of the references for her roman a clef. As Don McGovern observes, Summers references Slatzer early, by page 26—and then refers to him scores of times in Goddess, even using Chissell. But yet, Slatzer’s name, address and phone number never appeared in Monroe’s phone or address books. Would not someone so close to Monroe be in there? (McGovern, p. 102)

But the belief in Slatzer is not unusual for Goddess. In fact, after reading the book a second time and taking plentiful notes, I would say it is more like par for the course. Let us take the case of Gary Wean. Because its largely with Wean that the book begins its character assault on both John Kennedy and Peter Lawford. (For example, see pgs. 221-224). The idea is that Lawford arranged wild parties with call girls, John Kennedy was there and Monroe was at one of them. Summers characterizes Lawford like this: “It was this sad Sybarite who played host to the Kennedy brothers when they sought relaxation in California…”. Geez, I thought JFK and RFK knew Lawford because he was married to their sister.

These rather bizarre accusations made me curious. Who was Gary Wean and how credible was he? So I sent away for his book There’s a Fish in the Courthouse. Wean was a law enforcement officer in both Los Angeles and Ventura counties; he later became a small businessman. His book has two frames of focus. The first is on local corruption in Ventura County, California. Apparently realizing that this would have little broad appeal, Wean expands the frame to a national level with not just Monroe and Lawford, but also, get this, the JFK assassination! According to Wean, Sheriff Bill Decker and Senator John Tower explained the whole plot to his friend actor Audie Murphy. I don’t even want to go any further. But I will say that Wean’s tale says it was Jack Ruby who was going to kill Oswald, but when J. D. Tippit’s car pulled up, Ruby killed the policeman instead. (Wean, p. 588) Mobster Mickey Cohen got Ruby to now also kill Oswald, and somehow reporter Seth Kantor was tied in to the conspiracy since he could place Ruby at Parkland Hospital and he knew Cohen.

The primacy of Cohen in this theory can be explained by the fact that Cohen was Jewish and Wean’s book is extremely anti-Semitic. In fact, he later called the JFK murder a Jewish plot. (Wean, p. 593) As we shall see, this directly relates to the accusations about Lawford and John Kennedy. Wean says that these wild parties were at Lawford’s Malibu beach house. (Wean, p. 567) This puzzled me since, from what I could find, Lawford owned homes in Santa Monica and Palm Springs, and no Southern Californian could confuse those places with Malibu. Wean also says that Monroe met JFK at such a party during the Democratic Convention in 1960. But Monroe was not in Los Angeles for the convention. She was in New York City with her then husband Arthur Miller and her friend and masseuse Ralph Roberts. She was working on preparations for the upcoming film The Misfits. (McGovern, pp. 147-48)

But this is just the beginning of the problems with using Wean as a witness. Because in his book Wean says that it was really Joey Bishop who set up the wild call girl gatherings through Lawford. Why? Because Bishop, who was Jewish, was working with Cohen to get info on how Kennedy felt about Israel–through Monroe. (Wean, p. 567, p. 617). If that isn’t enough for you, how about this: Cohen was meeting with Menachem Begin at the Beverly Hills Hotel and there was plentiful talk about Cuba, military operations and the Kennedys. (Wean, p. 575). Further, Cohen had one of his mob associates at Marilyn’s home the night she died, at some time between 10-11 PM. (Wean p. 617) Wean calls this all part of the Jewish Mishpucka Plot. I could go even further with Wean, but I don’t think the reader would believe it.

The capper to this is that Wean writes that Summers called Bishop and the comedian admitted the arrangements he made. (Wean, ibid). At this point I thought two things: 1.) Wean was so rightwing he was a bit off his rocker. 2.) Was there anyone Summers would not believe in his Ahab type pursuit of a Monroe/Kennedy plot? Because according to Wean, Summers wanted him to go on TV.

But there is another Summers’ witness who was pushing the whole Lawford/Kennedy fable about call girl parties at the beach. This was Fred Otash. Otash was a former policeman turned detective who also worked for Confidential magazine, which was little more than a scandal sheet. He was once convicted for rigging horse races. After interviewing him for Sixty Minutes in 1973, Mike Wallace said he was the most amoral man he ever met. He once had his detective license indefinitely suspended.

In 1960 the FBI found out something rather revealing about Otash. In July of 1960, while JFK was running for president, a high-priced LA call girl was contacted by Otash. He requested information on her participation in sex parties involving JFK and Lawford, plus Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis. The woman said she could not comply since she had no such knowledge. Otash then asked if she knew any girls who perhaps were there. She said she knew of no one. Otash then asked if she could be introduced to Kennedy, and if so, he could equip her with a tape recorder to take down any “indiscreet statements’ the senator might make. She refused to do so. (FBI Report of 7/26/60)

The hooker had a higher moral code than the pimp. By those standards who could rely on Otash for anything?

Go to Part 2 of 2

-

Our Lady of the Warren Commission: Part 2/2

The Inconvenient Witness

Thomas Mallon. “And he (Oswald) had gotten away with it. The bullet had almost grazed the top of Walkers head, the hair, and he got away on foot, he didn’t drive a car… (And) he hid the rifle by the railroad tracks…”

To rebut Mr. Mallon’s claims, it is crucial to highlight that there is a substantial and irrefutable body of evidence indicating that Lee Harvey Oswald was never seen at or near General Walker’s home at4011 Turtle Creek Boulevard before, during, or after the attempted Walker assassination on April 10th, 1963. This point is not merely speculative but grounded in well-documented and verified accounts.

Furthermore, the weight of the evidence supports the conclusion that the assassination attempt involved not just one, but two individuals. Particularly compelling testimony comes from Walter Kirk Coleman, a 15-year-old residing near the General’s residence. On the night of April 10th, 1963, Coleman reported hearing a gunshot, an ominous sound aimed at ending General Walker’s life. In a swift reaction, Coleman dashed outside and peered over his fence. His vantage point provided a clear view of the church parking lot adjacent to General Walker’s residence. What he witnessed there is crucial to understanding the events of that fateful night.

Coleman observed:

A man getting into a 1949 or 1950 Ford, which was parked headed towards Turtle Creek Boulevard, with the motor running and the headlights on. (Before the man got into the car, he) glanced back in the direction of Coleman and (took) off. Also, further down the parking lot was another car, a two door, black over white, two-door Chevrolet sedan and a man was in it. He had the dome light on, and Kirk could see him bend over the front seat as if he was putting something in the back floorboard. Kirk described the car as; “black with a white stripe.” The man who took off in the Ford was described as; “a white male, about 19 or 20 years of age, about 5”10 tall, and weighing about 130 pounds. He was attired in “Kakhi pants and a sports shirt with figures in it. Kirk stated, “that this man had dark bushy hair, a thin face with a large nose, and was real skinny”. The second man was described by Coleman as, “a white male, about 6”1, about 200 pounds, wearing a dark long sleeve shirt and dark pants. Kirk could furnish no information on this man’s facial features nor his age.

Was one of the men Kirk Coleman saw, Lee Harvey Oswald?

“Coleman stated that he had seen numerous pictures of Lee Harvey Oswald, and he was shown a photograph of Oswald among several other photographs. He stated that neither man resembled Oswald and that he had never seen anyone in or around the Walker residence or the church before or after April 10, 1963, who resembled Lee Harvey Oswald”.

This testimony is a significant piece of evidence, as it directly challenges any claims that Oswald was present at the scene of the attempted assassination. (see this and this)

Coleman’s account is corroborated by Walker himself who testified to the Warren Commission that; “As I crossed a window coming downstairs in front, I saw a car at the bottom of the church alley just making a turn onto Turtle Creek. The car was unidentifiable. I could see the two back lights, and you have to look through trees there, and I could see it moving out. This car would have been about at the right time for anybody that was making a getaway. (Volume XI; p. 405)

April 8th, 1963.

Between 9:00-9:30pm on April 8th, 1963, Robert Surrey, a disciple of General Walker’s, was proceeding up Avondale Avenueto the house at 4011, Turtle Creek Boulevard. It was Surrey’s intention to enter the General’s property via the alleyway entrance. However, just prior to turning off Avondale, Mr. Surrey, “Observed a 1963 dark brown or maroon, four door Ford, parked on Avondale with two men sitting in it.” Surrey decided to avoid taking the alley, instead continuing around to block the car-park near the Mormon Church. Surrey observed the two men, “Get out of the car, walk up the alley and onto the Walker property and look into the windows of the Walker house.” At this point Surrey went to their automobile, where he checked the rear of the car, and observed there was no license plate. He then opened the door and looked into the car and opened the glove compartment. He observed nothing in the car or glove compartment which would help identify the occupants. He then went back to his car and drove to a position where he could observe the 1963 Ford leave.

Surrey testified to the Commission regarding the strange behavior of these two individuals…

Robert Surrey.“Well, the gist of the matter is that two nights before the assassination attempt, I saw two men around the house peeking in windows and so forth, and reported this to the general the following morning, and he, in turn, reported it to the police on Tuesday, and it was Wednesday night that he was shot at. So that is really the gist of the whole thing.”

Surrey told the FBI that, “He had never seen either of these two men before or since this incident, and (believed) neither of these two men was identical with Lee Harvey Oswald. (Surrey) “Described one of the men as a white male, in his 30s, about 5’10” to 6’ tall and weighing about 190 pounds. (Surrey) described the second individual as a white male, in his 30’s, 5’10” to 6’ tall, and weighing about 160 pounds. Both men were well dressed in suites, dress shirts and ties.FBI 105-82555 Oswald HQ File, Section 186 (maryferrell.org)

The Ballistics Evidence

From April 10, 1963, the bullet which was fired at General Walker, “Appeared to be from a high-powered, 30.06 rifle, and was a Steel jacketed bullet”. (see this)

This information was highly disseminated throughout the press and was reported in a New York Times article of April 12, 1963.

A Mystifying Metamorphosis: The “Magic Bullet” Phenomenon

From the ashes of President Kennedy, Officer Tippit and Lee Oswald’s tragic murders, a bewildering transformation occurred within the confines of the Dallas Police Evidence Room. Here, the “Walker bullet” performed a baffling act of alchemy, transforming from its official initial classification as a 30.06 steel-jacketed projectile into a 6.5 Mannlicher Carcano bullet—its steel guise mysteriously supplanted by copper. This near-miraculous change provided the Warren Commission with a serendipitous twist in their narrative, allowing them to lay the blame for the attempted assassination of Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker squarely on the now-silenced Oswald. This switch, a masterpiece of evidentiary sleight of hand, was instrumental in allowing the Commission to fortify their case of circumstantial evidence, confidently proclaiming in their report: “Oswald had attempted to kill Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker (Retired, U.S. Army) on April 10, 1963, thereby demonstrating his disposition to take human life.” (WCR; p. 20). Through this narrative legerdemain, the Commission could weave a more compelling, albeit convenient, story of guilt. (WCR;p..20)

A Dichotomy of Possibilities: Incompetence or Subterfuge?

The ballistic evidence bifurcates into two realms of possibility. One path leads to a conclusion of stark incompetence on the part of General Walker and the Dallas Police Department investigators, a lapse in judgment and identification that stood unchallenged for over seven months. The alternate path veers towards a more sinister landscape, positing that the bullet now residing in the National Archives (CE573) and officially linked to the Walker case was, in fact, a posthumous plant designed to frame Oswald. While this theory may initially seem steeped in the realms of far-fetched conjecture, it gains a semblance of plausibility when juxtaposed against the backdrop of questionable evidence marshalled against Oswald in both the JFK and Tippit cases.

The FBI’s Spectrographic Analysis: A Tale of Suppressed Evidence