This interview with Oliver Stone by Ed Rampell was awarded second place at the National Arts and Entertainment Journalism Awards in the category of Personality Profiles. We post it here in case you missed it. Read more.

Blog

-

Jack Ruby: A Review and Reassessment – Part 3

Jack Ruby: A Review and Reassessment Part Three

by Max Arvo

The Direct Involvement of Jolly West

In this final part, I discuss the direct involvement of CIA/MKULTRA psychiatrist Louis Jolyon ‘Jolly’ West in the legal defense of Jack Ruby. I will trace this from the time of Ruby’s arrest until West’s first examination of Ruby on 26th April, 1964.

Jolly West and the Panel of Psychiatric Experts

Although West only became formally involved in the Ruby case by mid-April 1964, he actually first became involved within, at most five days, of the shooting of Oswald. In Chaos, Tom O’Neill reported that Louis Jolyon ‘Jolly’ West had been involved in an effort to set up a panel of psychiatric experts who would be inserted into the Ruby trial. According to the documents O’Neill found, this effort predated West’s previously known entry into the case by months. Here’s what O’Neill wrote:

Seemingly as soon as the story of Oswald’s murder hit the presses, Jolly West tried to insinuate himself into the case. He hoped to assemble a panel of “experts in behavior problems” to weigh in on Ruby’s mental state. He took the extraordinary measure of approaching Judge Joe B. Brown, who’d impaneled the grand jury that indicted Ruby. West wanted the judge to appoint him to the case. At that time, police hadn’t revealed any substantial information about Ruby, his psychological condition, or his possible motive. And West was vague about his motive too. Three documents among his papers said he’d been “asked” by someone, though he never said who, to seek the appointment from Brown “a few days after the assassination,” a fact never before made public.[1]O’Neill’s citations provide some further details. A letter dated 6th January 1964 from psychiatrist Gene Usdin to Jack Ewalt, then-president of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), includes Usdin’s statement that “a few days after the assassination,” West called him to ask if he would join the roster of psychiatrists which would be submitted to the court.[2] O’Neill also cites a draft for a never-published book on the Ruby trial by West, in which the outline for Chapter 2 states that West “was asked to set up [a] panel of experts” and that this occurred “later that winter [1963] before Ruby trial started.”[3]

During my research into this aspect of West’s involvement, I have found several documents which corroborate and expand upon O’Neill’s pathbreaking account of West’s attempt to form a panel of psychiatrists. As a result, we can now confirm a remarkable fact: West was involved in Jack Ruby’s trial by, at the absolute latest, 29th November 1963.

Two articles published on November 30th provide the first public reference to West’s panel which I’ve yet found. The Tulsa Tribune reported that “Dr. L.J. West” of the University of Oklahoma had told the press on the night of November 29th that he was working to set up “a panel of nationally known psychiatrists [that] has agreed to serve, if asked, as friends of the court in the Texas trial of Jack Ruby,”. And that at least 10 “nationally known” psychiatrists had already agreed to serve. It seems reasonable to assume that one of these was Usdin.[4] Another Oklahoma article published the same day confirmed that West had first revealed the panel to the press the night before, on the 29th. [5] Recall, this is five days after Ruby shot Oswald.

Both articles report that West said “the panel had been suggested by a group of Dallas medical and legal experts”. And that he had been contacted by Professor Charles W. Webster “to sound out the possibility of arranging such a panel.”[6]That group of “Dallas citizens” apparently “came together when it became known that Ruby’s attorneys were planning an insanity plea.”[7]

Associated Press reports on the panel were published in Texas on the same day, but quoted Webster instead. Webster contradicted West, stating that “he was contacted by Dr. L.J. West” who “wanted him to ‘be the local spokesman.’”[8]Webster then directly and emphatically stated that the idea for the panel had not come from him: “This movement did not start in Dallas. It started with the American Psychiatric Association.”[9]

The article then seems to corroborate Webster’s claim that the APA had been the source of the effort: “the American Psychiatric Association announced, meantime, that it will offer the court a group of psychiatrists to examine Ruby.” The article adds that West was “an officer in the association” and that “West told him the association was willing … ‘to furnish a panel of experts who would act only as an arm of the court to come in here and examine Ruby.’”

The Oklahoma articles provide further details regarding the APA’s involvement:

The president of the American Psychiatric Association, Dr. Jack R. Ewalt, told Dr. West he would appoint a panel of three impartial experts in legal psychiatry if the Texas court requests the panel.[10]Webster elaborated that “nine experts in legal psychiatry have volunteered to have their names on the list” and that, from the list, “the court could select three.”

Other documents provide further evidence suggesting that Webster’s account was factual, not West’s. Law professor, and expert in legal insanity, Henry Weihofen was quoted in a December 21st article as saying that he had been “contacted by a group from the American Psychiatric Association” to provide his “opinion on the legality of the Texas district court’s calling its own panel of psychiatrists.” He also stated that “he understood the group from the psychiatric association as working with Prof. Charles Webster of Southern Methodist University in Dallas.”[11]

A letter from Weihofen to West dated November 30th 1963, which I found in West’s papers at UCLA, suggests Weihofen was telling the truth, as best as he knew it. Weihofen wrote to West:

I said over the telephone last night that I would type out a short memo on the point of law you asked me about.West therefore called Weihofen the night before, on 29th November – the same day he and Webster spoke to the press about the panel. Weihofen also references Webster as someone whom West said he was working with, and that his letter regarding the panel came as a result of West’s apparently urgent request.

I put this material together because you called me last night and I gathered you felt it would help you to have some documentation at once to support the proposition that the court has power to appoint impartial experts.[12]In his memo to West, which I also found in the Ruby archives, Weihofen argues clearly that the court could readily appoint a panel of experts.

West referenced the Ruby trial and the panel of experts twice in subsequent letters to Weihofen. On December 20th, he wrote:

At the present time there is no sign that the Dallas court will ask for any psychiatric assistance. Jack Ruby’s defense attorneys are to my knowledge appointing a couple of outstanding psychiatrists from the East Coast (Drs. Bromberg and Guttmacher) who will aid in the defense. However I believe that it is still too soon to tell whether our efforts have been entirely in vain. Please be assured that I shall keep you posted in this matter.[13]West’s reference to Bromberg and Guttmacher joining Ruby’s defense came two days before their involvement was reported publicly, and a day before they first examined Ruby on Dallas. West must therefore have received that information from someone directly involved in Ruby’s defense; this alone suggests that West was not seeking to assist the Ruby case in an impartial manner, but was always working for Ruby’s defense.

On February 13th 1964, West provided a further update to Weihofen:

You may have noticed that at least some semblance of success has eventuated from our effort to persuade the Dallas Court to appoint an impartial panel of examiners in the Jack Ruby case. That it was done at all I think is certainly a credit to the people in Dallas who wanted to bring it about. I am sure that you must be gratified by the knowledge that they were armed and strengthened by your opinion in dealing with the problem.[14]Once again, West suggests that the panel originated with “people in Dallas who wanted to bring it about,” even though Weihofen had said himself that he had been contacted by a “group from the American Psychiatric Association.” Although I cannot confirm definitively as to whose account was true, the available evidence supports Webster’s claim that the panel originated with West and the APA, more than it supports West’s claim that it originated in Dallas.

3.2 – Col. Albert Glass, Oklahoma and the APA

On the back of the second page of Weihofen’s legal memo to West, there is a handwritten note which reads: “Let’s pause, and call on Col. Glass.” This refers to Colonel Albert Julius Glass, who served in the US Army from 1941 to 1963. In 1957, an article described Glass as “the Army’s top psychiatrist.”[15] He had been a colleague, and seemingly something like a mentor, to West since at least as far back as 1954, by which time West was already working with Sydney Gottlieb on MKULTRA research.

Glass resigned his 22-year military career on October 31st 1963.[16] He began his new job as Oklahoma’s director of mental health on the following day, November 1st 1963.[17] By December 12th, he had also joined the University of Oklahoma’s faculty, as a clinical professor of psychiatry, neurology and behavioral sciences – the same department West headed.[18] Numerous documents I have found confirm that both of these roles were secured for him by West himself.

Glass’ appointment as director of mental health for Oklahoma seems to have been a contentious process. At least four members of the Oklahoma Mental Health Board, who were required to vote on Glass’ appointment, expressed concern that they were being pressured into appointing Glass by the Governor. One of these members “exclaimed” before the vote: “Are we under pressure? Do we have to take him because [Governor] Bellmon says so? We have a lot of people to interview yet.” Two other members of the board specifically cited West as a source of their concerns, questioning his role “in getting Glass to come to Oklahoma.” During the meeting, it was revealed that “it was West who arranged [Glass’] trip [to Oklahoma].” Another member of the board also cited West: “‘I had misgivings because Dr. West was responsible in getting him here,’ Dr. Smith said.” Why exactly these members of Oklahoma’s Mental Health Board were particularly wary of West’s involvement is never stated.

Besides his evidently close and longstanding relationship with West, Glass was also one of the handful of APA members directly involved in the case. Glass was a member of the APA’s committee on psychiatry and the law, as was Manfred Guttmacher. Other members of note included Henry Davidson, Karl Menninger and Herbert Modlin. Dr. Jonas R. Rappeport later said that they would “ask what I thought and I shot my mouth off.” After President Kennedy’s assassination, Dr. Guttmacher evaluated Jack Ruby, who had killed alleged assassin Lee Harvey Oswald. Dr. Rappeport recalled Dr. Guttmacher’s discussion of Ruby at those meetings.[19]

The presence of Glass on this committee, his long relationship with West, and the evidence that West consulted with him on the panel of psychiatric experts seems to clearly suggest that Glass was an important figure in West’s attempt to form the panel of experts. It also seems to strongly corroborate the claims and statements of Webster, Weihofen, Usdin, and Ewalt that West’s efforts were rooted in the APA.

It also seems clear now that West wanted in some way to obscure the origins of his efforts to form the panel. His deference to Col. Glass, expressed on Weihofen’s memo of November 30th, seems to also suggest that Glass had knowledge of the effort and that West would defer to him. It therefore seems likely that West’s efforts to form the panel may have originated with Glass; at the very least, Glass – and the APA’s committee on psychiatry and the law, of which Glass and Guttmacher were members and which discussed the Ruby case at the time – played an important role in this effort.

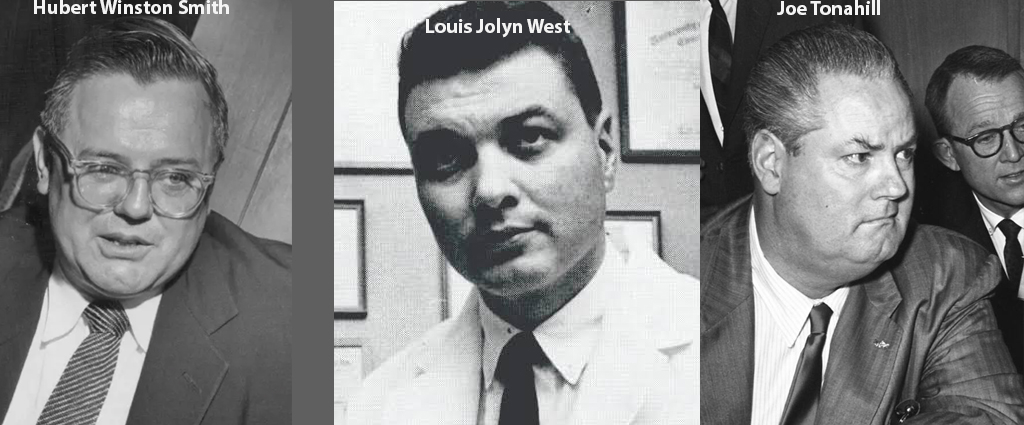

3.3 – Jay Shurley, Hubert Winston Smith, Jolly West

Before he brought Glass to Oklahoma, West also brought an old friend, colleague and another mentee of Glass’ – Jay T. Shurley. West and Shurley had met while serving in the military in Texas: West for the Air Force, Shurley for the Army. A history of the early years of U. Oklahoma’s psychiatry department states:

When the Korean War ended, Albert Glass, who was Shurley’s boss, and according to Shurley, the best army psychiatrist, conducted a month-long tutorial for his protégé and Jolly West to prepare them for the psychiatry and neurology board exams (both were required then) in Chicago in 1954.[20]After those exams in 1954, West became head of U. Oklahoma’s psychiatry department; Shurley joined him there three years later.

In 2002, Tom O’Neill interviewed Shurley during his research for Chaos. O’Neill confirms that Shurley had been a “good friend” of West’s for “forty-five years,” and that he was “one of the few colleagues [of West] who admitted that West was an employee of the CIA.”[21] In the same interview, Shurley also confirmed that he had worked for intelligence, though for the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), not the CIA. He also stated that both men had high-level security clearances, and that their work for their respective agencies was classified: “My classification area while I was in the service was a very high order too.”[22]

The history of U. Oklahoma’s psychiatry department, quoted above, states that West had “charm and wit” and that “from the beginning he was known as a master manipulator.”[23] Shurley describes West in much the same way: “Jolly really could talk people into anything. He was a tremendous salesman… he really knew how to influence individuals in close personal contact.”[24]

Shurley also discusses West’s involvement with the Ruby case. West apparently tried to get Shurley “involved in it.” Shurley said he declined, primarily because “it really had no relationship to the work I was doing.” He then also brought up Hubert Winston Smith, entirely unprompted, saying that he was a “good personal friend” of Smith and that they had known each other “for some years.” The papers of Smith’s I have viewed confirm this; Shurley was involved with Smith and his Law-Science Academy since the early 1950s, several years before West also became involved with Smith.

Shurley then stated that, before Smith became defense lead for Ruby, he was “dicking around with authorities to the take the case.” Shurley then connects Smith to West directly, stating that Jolly used that connection and appealed to it when he asked Shurley to join the case. When Shurley declined, West “really was very disappointed he couldn’t convince me that I ought to get involved with it.”

Other comments by Shurley clearly present West and Smith as working together on their efforts relating to the Ruby case. According to Shurley, West’s motivation to insert himself into the case derived in part from “what Hubert Smith told him,” which apparently led West to believe that “there was a good case to be made for Ruby not being compos mentis.”

Lastly, Shurley also confirmed that “Smith and Belli knew each other well”, and that Smith was “extremely well known to the legal community in Dallas.” Shurley also confirmed that West knew Alton Ochsner and Gene Usdin, adding that Usdin was Ochsner’s “chief of psychiatry at the [Ochsner] clinic for many years.” According to Shurley, Ochsner “may or may not have been working for the CIA” and that his research was “way over the edge and unusual.”

3.4 – Smith’s Law-Science Academy

The records of Smith’s Law-Science Academy corroborate everything Shurley stated, confirming that all of these individuals had indeed known each other for years prior to the Ruby case. There are dozens of examples in these records demonstrating these close relationships and connections; the February 1959 Law-Science Course in New Orleans serves as a good representative example, and also features many of the individuals I have so far discussed.

That 1959 course seems to have been the first of Smith’s Law-Science Courses which West attended. To show the influence Smith had other attendees included West’s mentor, colleague and MKULTRA researcher Stewart Wolf; Melvin Belli’s friend and future defense lawyer for Ruby, Joe Tonahill; Dr. Alton Ochsner, and Harold Rosen.

West was one of the most prominent participants at that course, speaking at four of the eleven after-dinner or luncheon presentations.[25] West also participated in two mock trials, the second of which also featured Wolf, Smith and Herbert Modlin, who was also a member of the APA psychiatry and law committee discussed earlier, of which Glass, Guttmacher and others were members. The topics of West’s talks included ‘New Developments in Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences’ and ‘Waking Dreams: Some Mental Disturbances in Everyday Life.’

Harold Rosen was another prominent participant in the course, and also had a long-standing friendship with Smith. Rosen’s area of expertise was in hypnosis. The after-dinner talk on the 1959 course’s first day featured Rosen and Smith, discussing the subject ‘Medicolegal Aspects of Hypnosis and Criminal Interrogation.’

Hypnosis played a substantial role in several MKULTRA research projects. West himself provided a detailed description across 6 pages of “the hypnosis research project” he would conduct for MKULTRA, in his 11 June 1953 letter to Sidney Gottlieb. West’s letter – the first of the letters between the two which have so far been found – is clearly written following previous discussions with Gottlieb regarding the research project. By the day of West’s letter, MKULTRA itself had only been in existence for a mere 59 days, following its approval by CIA director Allen Dulles on April 13th.

In his 1953 discussion of “the hypnosis research project” sent to Gottlieb, West wrote that its goals included:

A. Short-term goals1. Determination of the degree to which information can be extracted from presumably unwilling subjects (through hypnosis alone or in combination with certain drugs), possibly with subsequent amnesia for the interrogation and/or alteration of the subject’s recollection of the information he formerly knew.

2. Determination of the degree to which basic attitudes of presumably hostile or resistant subjects can be altered in an advantageous way, either immediately or in a “delayed-action” manner.

3. Elaboration of techniques for implanting false information into particular subjects, or for confusing them, or for inducing in them specific mental disorders.B. Long-term goals…4. Study of the induction of trance-states by drugs, and their relationship to and usefulness in conjunction with hypnotic procedures.[26]

Clearly, West was describing a quintessential early-1950s CIA research project into hypnosis, drugs, mind-control and brainwashing. The extent of his knowledge, and the clear parallels between West’s description and the research undertaken under Operation Artichoke over the few years preceding MKULTRA’s establishment, seems to suggest that West’s involvement predated his letter to Gottlieb and MKULTRA itself. I would not be surprised to learn that he was involved in MKULTRA predecessors like Artichoke.

Modern hypnosis was a relatively new field during the 1950s and 1960s. According to Jay Shurley, West was

really the protagonist of doing hypnotism studies. … He had a lot of support too because WWII did increase the popularity of hypnosis … So at that time he was riding the crest of a wave of positive feeling about hypnosis and he took considerable pride in his skills of hypnosis.[27]As established, West was not just “riding the crest of a wave of positive feeling,” but was at the center of America’s vast research program into mind-control, which had hypnosis as one of its primary focuses.

3.5 – Hypnosis, Drugs, Harold Rosen, Jolly West and the Law-Science Academy

West was a central figure in many of the earliest organizations founded in the 1950s which focused on hypnosis. In 1958, he was chosen as one of the first members of the American Medical Association’s newly formed Committee on the Medical Use of Hypnosis. By the same year, he was a Diplomate of the American Board of Medical Hypnosis.[28]

West was also a senior member of the Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis (SCEH), whose leadership consisted of most of the foremost practitioners of hypnosis across America, several of whom also had extensive connections to intelligence. The launch of the Society’s journal “represented the official establishment of clinical hypnosis as a separate professional entity in the United States.”[29] By 1953, the SCEH had granted ‘fellow member’ status to only eight individuals, two of whom were Milton V. Kline and Harold Rosen.[30]

Rosen was also a close friend and of Hubert Winston Smith and a regular participant in his Law-Science courses. On January 10th 1957, Smith wrote to Rosen:

I am flattered by your suggestion that you would like to undertake a collaborative article with me on the subject of “Medicolegal Aspects of Hypnosis of Drug Induced Confessions.”[31]Evidently, Rosen felt that Smith was qualified enough in the field of hypnosis and in drug-induced confessions that he could co-author an article on the topic with him – five years before the Ruby trial.

Rosen was also close to George Estabrooks, a foundational figure in the postwar field of hypnosis and father of ‘direct suggestion’. In 1959, Jolly West recommended Estabrooks’ seminal 1943 textbook Hypnosis to a student who asked him for recommendations. West replied that he was “flattered that you decided to consult me on the subject of hypnosis,” then said of Estabrooks’ text that it was “published about fifteen years ago. It is still one of the best.”[32]

In Estabrooks’ papers, there are dozens of letters between Rosen and Estabrooks, just as there are dozens between Estabrooks and Milton V. Kline. Estabrooks was a crucial consultant and advisory figure for the military and various intelligence entities, principally the FBI; he corresponded regularly with J. Edgar Hoover directly over many years.

His papers also include an undated essay on ‘The Military Implications of Hypnosis,’ in which he discusses significant recent research on the subject. He references “sensory deprivation,” stating that “work at McGill, Princeton, Georgetown, indicates that sensory deprivation produces neurotic, even psychotic, symptoms. Some form of personality disintegration seems to occur.” His reference to research at McGill must surely refer to the work of infamous MKULTRA researcher Donald Ewen Cameron, whose brutal techniques focused exactly on these topics. Jay Shurley also confirmed to Tom O’Neill that Cameron was “important … in connection with Jolly’s participation in the CIA experiments about LSD on unsuspecting soldiers and civilians.” Shurley added that “they knew each other from a good while back,” and that they had probably met when West was training at Cornell.[33]

Estabrooks then also specifically cites the work of John C. Lilly, another MKULTRA researcher and colleague of Jay Shurley, who was also focused on sensory deprivation and isolation.[34] Lilly was also a longtime colleague of Hubert Winston Smith, whose papers include correspondence with Lilly dating back as far as 1957.[35]

Another of the primary leads he discusses regarding methods of increasing susceptibility to hypnosis is “the whole field of pharmacology.” He writes that “it would seem reasonable that some one drug out of the hundreds now being synthesized could have a great affect on hypnotizability.”[36]

Milton V. Kline, West and Rosen’s fellow SCEH member and hypnosis researcher, also had verified and deep connections to the CIA. In 1980, it was reported that Kline was a “former consultant to the CIA’s super secret behavior-modification project Bluebird,” which was the predecessor to Artichoke, which then led to MKULTRA. Kline always emphatically stated that “one of the central goals of these experiments — to create a hypnotized, remote-control assassin — was entirely possible, though he denies knowledge of any ‘terminal experiments’ that would have tested his theories.” Kline emphatically stated that: “It cannot be done by everyone. … It cannot be done consistently, but it can be done.” According to Kline, he could “produce such a killer in three to six weeks.”[37]

Even if we choose to disbelieve Kline’s claims here, what this confirms is that Kline – and Estabrooks, and Rosen, and West too – did believe in the efficacy of hypnosis, and that it was systematically applied and studied to intelligence and military operations throughout those postwar years.

West’s expertise in exactly this subject – the induction of ‘abnormal’ mental states – was publicly well-known enough that he was asked to author a volume of McGraw-Hill’s series on Abnormal Psychology. West’s volume was to be titled: ‘Experimental Psychopathology: The Induction of Abnormal States.’ In the April 1966 proposal, the publisher describes the volume’s focuses as:

the conceptual and empirical literature of brainwashing, sensory deprivation, sleep deprivation, psychotomimetic drugs, hypnosis (in some instances) and other situational contexts that induce aberrant behavior in essentially normal individuals.[38]Although the volume was ultimately abandoned, we can see that it would have focused on the central research focuses of not just West’s career but of MKULTRA and postwar military and intelligence behavior-modification research overall.

It is hopefully clear by now that research into these methods of behavior modification, or mind control, had continuities and a history extending from the postwar period through the 1960s (and arguably extending further before and after that time period). Many of the figures I have discussed were at the heart of this research throughout, and built their careers and reputations on this intelligence-backed research.

Smith’s Formal Entry to the Ruby Legal Defense

All of this evidence confirms that West was involved in the Ruby defense as soon as 29th November, and that he and Smith had extensive, direct and longstanding connections to US intelligence agencies and to US postwar research into interrogation, torture, behavior modification and mind control. Both were also both involved in the Ruby case much earlier than they, or anyone else, ever reported that they were.

Smith was first reported to have become Ruby’s defense lead on the night of March 24th, the same day he apparently met Ruby for the first time.[39] He left the case on June 3rd, and so was only formally attached to Ruby’s defense as an attorney for 71 days.

March 25th – 28th 1964

On March 25th, the day after he joined the case, Smith told the press that he wanted Ruby “to undergo another long series of medical and mental tests” and argued that, if Judge Brown refused, “it would be grounds for a reversal or Ruby’s murder conviction.” He also declared that “the entire Law Science Academy at the University [of Texas] will be asked to aid in Ruby’s defense. Through the academy, he said, the defense will have access to the nation’s top trial lawyers and medical experts.”[40]

Smith also told the press that he “hoped to be able to use truth serum and hypnosis in the [new] examinations.”[41] Two days later, he told the press that he would “look around today for a top psychiatrist to treat Ruby for death-cell gloom.”[42] It was also reported that Smith was specifically given this “authority to hire an internationally known psychiatrist” by “Jack Ruby’s family,” who were concerned that Ruby was “becoming despondent in his isolated jail cell in Dallas.”[43]Although Smith said he would “look around” for such a psychiatrist, he said at the same time that “‘some great specialists’ had offered to treat Ruby’s despondency.”

April 1964

On April 2nd, it was reported that Smith wanted Ruby “moved to the Austin State Hospital for more lab tests.”[44] On April 5th, Smith met with Ruby again in the Dallas County Jail. Though he “declined to discuss the visit,” he did say that he “just stopped by to cheer him up.”[45]

On April 9th, one of Smith’s students told the press that Smith “was keenly interested in the Jack Ruby case from the very start. He is probably more familiar with the case than some of those who were physically present and followed the trial day after day.”[46]

The first legal actions of Smith’s tenure as defense lead came on Monday April 13th. Central to Smith’s strategy was receiving an extension on the motion for a new trial. Smith claimed that he had “only a vague idea of what went on during the trial,” which, based on the numerous examples I’ve already cited, seems obviously untrue, and that he was “thoroughly shocked at how much evidence was not introduced at the trial.” He also claimed that he had “learned recently ‘of new brain tests’ he would like to have Ruby undergo.” Smith’s pleadings did not succeed and Judge Brown “set April 29th as the date for an open hearing on a defense motion for a new trial.”[47] Smith therefore had 15 days until the hearing.

Five days later, on the 19th, Smith wrote to Jack Ewalt, APA president, lamenting that Ruby “was never hospitalized for complete studies including hypnosis, sodium pentothal interviews, etc.,” before claiming that “Ruby had agreed in his contact with us to submit to any studies or examinations we propose.” In a manner strikingly similar to the efforts of West, Ewalt and the APA in November 1963 to get a panel of experts appointed, Smith then asked Ewalt to directly involve the APA in “appointing accredited men to conduct thoroughgoing studies in the hospital.”

He specifically suggests West, stating that he had already “agreed to function without fee,” as had Robert Stubblefield, who had already been appointed by Judge Brown as a court examiner of Ruby. Smith then asked Ewalt that, as “president of the APA to consider the above two men as competent examiners.” Smith also confirmed that “time is very important” and that the exams needed to be completed “by Wed [22nd] or Thursday [23rd]” in time for the hearing on a new trial on the 29th. Smith also asked Ewalt to consider “Herbert Modlin (or Dr. Roy Menninger) of Menninger Clinic.”[48]

In short, Hubert Winston Smith turned to a small network of friends and colleagues, and to the APA, when seeking to formally introduce new psychiatrists to the Ruby case, in such a manner that they could directly examine Ruby, and specifically to administer hypnosis and sodium pentothal (i.e., ‘truth serum’). As discussed, by this time that precise combination had been researched and practiced extensively for two decades. By people like West, Smith, Watson, Diamond, Wolff, Grinker, Overholser, and many others, both within this small group of individuals, and across the national academic, military and intelligence communities.

April 24th – 26th: The Weekend of Jack Ruby’s Acute Psychotic Break

On the 25th April, Smith was already 33 days into his 72-day stretch as Jack Ruby’s defense lead; Jolly West was due to examine Ruby for the first time on the following day. Bizarrely, on the very day that his entire insanity defense would be ‘tested’ he was one thousand miles away in Chicago, hosting a law-science course. On the afternoon of the 25th, hours before Ruby had his acute psychotic break or perhaps during it, Smith hosted a discussion with Harold Rosen on the “Medicolegal Aspects of Hypnosis in Civil and Criminal Cases.”[49] According to West, Smith had asked him “four days ago” – so, on the 22nd – to visit Dallas and examine Ruby. They had discussed using “hypnosis and intravenous sodium pentothal” to “provide further information concerning Mr. Ruby’s state of mind at the time he shot Lee Harvey Oswald on 24 November 1963.”[50] The next day, on the 26th, after Ruby had suffered a psychotic break and West examined him, Smith held five more sessions, three of them with Rosen and himself. Each of those sessions focused on hypnosis.

On the 22nd, Smith filed a motion for “order by court for immediate hospitalization of defendant,” arguing that Ruby needed “not only examination, but strengthening of ego of the individual through psychotherapy. Such measures call for full hospitalization with continuing psychotherapy.” He then insisted upon the importance of “deep-level study of the accused under hypnosis by a person who is a qualified specialist in that field, such as Dr. Jolyon West.” Smith provides West’s U. Oklahoma role, then adds that he was “Director of the Institute of Hypnosis.” He also told the court that West “was competent to perform and evaluate so-called “truth-serum” tests which involve the administration of sodium pentothal to the subject, and the exploration of his personality and mental content while the subject is in a state of partial reduction of cortical control.”[51] Smith concludes his motion by requesting that Ruby be hospitalized in Parkland Hospital or any other large, well-equipped hospital in the state, and that “Dr. Jolyon West and his associates be given full and complete access and opportunity to study and evaluate said Jack Ruby,” including by doing “heretofore neglected tests, including studies under hypnosis and sodium pentothal.”[52] Three days after Smith submitted this motion, and the day before the court ruled on Smith’s motion, Ruby had an acute psychotic break.[53]

The only primary sources for information regarding Ruby’s break seem to be the Dallas police and Jolly West himself. In an interview on the 26th, Dallas Sheriff Bill Decker said that:

The guard got up to get some water and attempted to turn the key in the door. Just as he placed the key in the door to turn it, to open the door, he heard commotion and looked and Jack had backed away from the wall and then ran some two or three steps striking his head on a plaster wall, which caused an abrasion of about an inch and a half, inch to an inch and a half, and also … caused a large welt or knot to be raised on the top of his head.[54]The script for that same news broadcast added the further detail that Ruby was apparently “playing cards with his guard, S.J. Belin, early [that] morning, when Belin started to leave the cell for a drink of water. Ruby then broke back in the news, by butting his head against a wall.”[55]

West’s Account of Ruby’s Psychosis

In his report on his examination of Ruby, West wrote:

Upon arriving at the jail this afternoon I met Sheriff Bill Decker, who informed me that last night after midnight Mr. Ruby had tricked his guard into stepping out to get him a glass of water, and then had run and struck his head against the wall. It was not clear whether or how long the prisoner was unconscious. According to the Sheriff, Mr. Ruby had subsequently been taken to a hospital where a physician examined him (including X-ray films of the skull) and stated that he was without serious injury. It was also said that Mr. Ruby had been caught stripping out the lining of his prison garb, apparently to fashion a noose for himself.[56]Based on these reports from West and Decker, we can only say that, sometime early on the 26th, “after midnight” and “early this morning,” Ruby suddenly took the opportunity during a game of cards with his guard to run headfirst into the wall. This caused an abrasion and a “large welt” on his head. They provide no confirmation as to whether Ruby was ever unconscious.

When West examined him in the afternoon of that same day, he reported that Ruby was “obviously psychotic” and also that “the experiences of last night are not only grossly delusional but include auditory and visual hallucinations as well.” In the accounts of the previous night, there is no mention of any such psychosis, or of hallucinations or delusions. Crucially, West concluded that it “made it clear that there has been an acute change in” Ruby’s condition since the “earlier studies” of Bromberg, Guttmacher et al.

West also states that “it was possible gradually over the course of an hour to obtain a reasonable sample of the patient’s mental content.” However, according to the doctor’s visiting list for Ruby, West only saw Jack for 33 minutes, from 4:42 pm to 5:15 pm.[57] That same visiting list does not include West’s examination of Ruby the following day, on the 27th.

West examined Ruby “in a private interview room.” Ruby appeared “pale, tremulous, agitated and depressed” and “disheveled and unkempt. He stared fixedly at the examiner with an expression of suspicion; his pupils were markedly dilated.” He had a large cut on his head, and his left cheek was “swollen and reddened.” This injury was not mentioned in other counts of Ruby’s wounds from that night; the police accounts only mentioned wounds to the top and back of his head. Ruby was also apparently “at first … unwilling to be left alone” with West and “seemed to anticipate some terrible news or fearful event.”

According to West, during the previous night, Ruby “became convinced that all the Jews in America were being slaughtered. This was in retaliation against him, Jack Ruby, the Jew who was responsible for ‘all the trouble.’” As a result of “distortions and misunderstandings derived from his murder trial,” Kennedy’s assassination “and its aftermath were now being blamed on him.” In Ruby’s hallucination, he was the “cause of the massacre of ’25 million innocent people.’”

The details of his hallucinations only become more terrifying. He apparently had “seen his own brother tortured, horribly mutilated, castrated, and burned in the street outside the jail; he could still hear the screams.” As for his vision of an American holocaust, “the orders for this terrible ‘pogrom’ must have come from Washington, to permit the police to carry out the mass murders without federal troops being called out or involved.”

Ruby apparently resisted West’s attempts to persuade him that “these beliefs were incorrect, or the symptoms of mental illness”. He became “more suspicious” of West. Even suggesting repeatedly that he was being “mocked or ‘conned’” by West, as Ruby believed West “must know all about the things he was telling” him.

Whatever had happened the previous night, it apparently made Ruby lose all hope, to the extent that he became suicidal:

He kept repeating that “after what happened last night” there was nothing more in life for him. He had smashed his head against the wall in order to “put an end to it.”West also states that “some material pertinent to his shooting of Oswald was elicited, but is not included in this report.” I have found no reference anywhere else to what that information may have been, nor any suggestion that it was recorded anywhere else. Once again, this seems hard to fathom, and surely any such information would be of tremendous significance. It’s also worth noting that, although Ruby was apparently hopelessly psychotic, he was still able to discuss his shooting of Oswald with West, in a manner coherent enough that West noted the information as “pertinent.”

West concludes that “At this time Mr. Ruby is obviously psychotic,” and provides a specific diagnosis of “acute psychotic reaction: paranoid state.” As for its causes, West said they were “not fully determined,” but that the “stress of the patient’s recent life situation is undoubtedly an important factor.” Other factors “including organic brain disease chronic or acute” (such as psychomotor epilepsy) may have also contributed. Based on this diagnosis, West recommended “immediate psychiatric hospitalization, study, and treatment. Close observation. Suicidal precautions.”

West’s recommendations were exactly what Hubert Winston Smith had already requested and publicly stated that he desired for Ruby– weeks before Ruby had this apparent psychotic break. West also states in his report that “the unexpected discovery” of Ruby’s acute psychotic break meant that he would have to “postpone consideration of the special examinations into his mental status at the time of his shooting last November.” Once again, this aligned with Smith’s requests for more time to develop his own defense.

In short, it seems that Ruby’s acute psychotic break happened to exclusively benefit the defense as orchestrated by Hubert Winston Smith and Jolly West. The specific ways it benefited them, and the recommendations it allowed West to make, also aligned exactly with Smith’s previously stated desires and beliefs.

The timing of the break was also unbelievably convenient. By the morning of Monday 27th, Smith was back in Dallas. Later that day, Smith, West and Ruby returned to Judge Brown’s court, where Brown denied Smith’s motion for Ruby’s hospitalization, which he had filed on the 22nd, before Ruby’s psychotic break.[58]

However, during that same court hearing, Eva Grant filed a motion for a sanity hearing, which Brown did not rule on at that time. The prosecution told the press that Brown “has no alternative but to grant” such a motion for a sanity trail before a jury. Based on West’s report on Ruby, the defense were now able to claim, as they indeed did, that “Jack Ruby has positively become and now is insane.”[59]

When West examined Ruby a second time, on the 27th, he found “his condition to be considerably improved over last night.” Ruby tried to “avoid discussion of his delusional preoccupations that the Jews were being murdered.” West stated confidently that “there were many signs of considerable improvement of symptoms overnight.” Ruby’s psychotic break therefore seems to have – if West’s account is to be trusted – had a sudden onset after midnight on the night of the 25th. West first saw Ruby in the late afternoon of the 26th. When he saw Ruby again on the 27th, it was “from 8:00 to 9:30 this morning,” on the 27th. According to West’s reports, Ruby’s psychotic episode therefore lasted somewhere between 6 to 36 hours.

Yet, psychotic episodes typically last several days, and can last for weeks or months. If an acute temporary psychosis is induced by some substance, such as LSD or other potent hallucinogens, the psychosis will typically last until the drug’s effects wear off. In the case of LSD, effects typically begin to appear somewhere between 30 to 90 minutes after it is consumed. Their strength peaks around 3 to 5 hours later, and they last on average between 6 to 12 hours. The full effects can take around 24 hours to wear off. Sudden and severe psychotic breaks, of the kind Ruby suffered, which last for a matter of hours, as Ruby’s also did, and which are not preceded by a history of such breaks or related mental illnesses, can have relatively few causes. The most likely cause of such a break seems to be consumption of some kind of potent drug. Stress can also contribute to the development of such breaks, as can prolonged isolation.

During a June 1967 discussion between defense lawyer Phil Burleson and prosecution lawyer Bill Alexander, Alexander stated that:

when West first testified on Jack Ruby’s mental condition, in 1964, (according to Alexander) he said that Jack needed treatment for what Alexander thinks is just “deathrow psychosis” and fairly normal, and suggested that he be treated with LSD (then in an experimental stage).[60]LSD is not mentioned in any of West’s official reports on Ruby, or anywhere else in material related to the case. Alexander – attorney for the District Attorney’s office and Ruby’s prosecution, not the defense – had no reason to defend or protect Ruby or any member of his defense team. His comment seems credible; based on the notes of the discussion taken by West’s assistant Elizabeth Price, Burleson did not challenge Alexander’s claim. Which then led Alexander into a discussion of the Tusko LSD experiment. In short, Alexander’s claim that West advocated using LSD on Ruby seems to have been accepted by those in the room.

Given everything I have already discussed, I would suggest that the use of LSD on Jack Ruby, perhaps by West himself, was entirely in keeping with the methods and preoccupations of West and all of his colleagues and the organizations with which he was associated. As also discussed, LSD was particularly utilized in combination with hypnosis by intelligence-affiliated researchers in their attempts to establish the extent to which a human mind could be subject to behavioral modification. We also know that the use of drugs and hypnosis on defendants had been studied, advocated and practiced by the like of Hubert Winston Smith for many years prior to 1963. In Smith’s case, his interest dated back to 1943, to his first law-science symposia, which also featured numerous future MKULTRA researchers and the likes of J. Edgar Hoover, Winfred Overholser and Harry Anslinger.

Conclusion

On the basis of everything I have discussed in this paper, I believe it is reasonable to make several significant allegations, or suggestions, regarding the treatment of Ruby, after he shot Lee Harvey Oswald.

- It seems inarguable that the individuals most influential upon Ruby’s defense, and his handling during that time, were involved within a week after Oswald was shot. It also seems inarguable that those individuals – chiefly, West and Smith – sought to obscure how soon they had become involved, the nature of their involvement, and their motives for that involvement. Smith made one reference later in 1964 to having been kept informed on the trial throughout by Tonahill. West never said he was involved prior to his first examination of Ruby on April 26th 1964. As I have established, both Smith and West were involved within days of Ruby’s arrest. Their involvement was from the very start focused on ensuring that psychiatrists, all of whom were long-time colleagues and friends and many of whom shared the same kinds of intelligence connections, were introduced to the Ruby case and would be able to directly examine Ruby. Although their efforts were always on behalf of Ruby’s defense, every time they sought to get psychiatrists involved, they worked to frame their involvement as deriving from impartial, external sources, chief amongst which was the American Psychiatric Association, led by Jack Ewalt. I would therefore suggest that these individuals sought to systematically confuse the timing, nature and reason for their involvement from the very start. And they also sought to obscure their interest in introducing psychiatrists and their efforts to do so, seeking instead to have the psychiatrists appear to have been recommended not by individuals closely involved with the defense, but by distant, impartial national bodies like the APA.

- Jack Ruby’s defense, led by Melvin Belli but fundamentally shaped by his long-time friend Hubert Winston Smith, pursued an obscure and partially obsolete diagnosis of psychomotor epilepsy, which there was no evidence Jack Ruby had ever suffered from. By pursuing this diagnosis, the defense team were successfully able to introduce numerous psychiatrists and medical professionals to the case, e.g. Manfred Guttmacher, Walter Bromberg, Roy Schafer, and various others. The involvement of these individuals was also accompanied by myriad psychiatric tests, administered to Ruby at nearby hospitals. Although their effort to argue Ruby’s insanity failed during the initial trial, they did succeed at raising doubt as to Ruby’s sanity and thus credibility, while also successfully gaining control over Ruby’s clinical and psychiatric treatment.

- After Ruby was convicted in March 1964, Hubert Winston Smith emerged suddenly from his previously obscured involvement in the case to become defense lead. Within days, he requested further psychiatric tests. He also requested a delay in the motion for a new trial, and the hospitalization of Ruby, specifically for a prolonged, deep study of Ruby under hypnosis and using sodium pentothal, all conducted by Louis Jolyon West. All of these motions were rejected by Judge Brown, and Smith found himself with just a handful of days to try to somehow prove Ruby’s insanity to the court. On April 19th, he told Jack Ewalt that West had agreed to join the case, and that Ruby should be examined as soon as possible, ideally by April 22nd or 23rd. On the 22nd, he asked West to fly to Dallas to examine Ruby. On the 25th, Smith traveled to Chicago, where he discussed hypnosis and interrogation in criminal trials. On the same night, Ruby had an acute psychotic break and apparently attempted suicide. On the afternoon of the 26th, West saw Ruby and reported that he was hopelessly insane. As a result, he requested the exact same things that Smith had requested just a few days earlier, when he filed the motion to have Ruby hospitalized. On the 27th, Smith was back in Dallas, and he asked the court again to hospitalize Ruby for hypnosis and sodium pentothal tests. Brown rejected that motion, but, on the basis of Ruby’s psychotic break and West’s report, Ruby’s sister Eva Grant filed a motion for a sanity trial, which Brown would be unable to dismiss. I would therefore suggest that Smith and West, their hands forced by Ruby’s conviction and Brown’s rejections of their subsequent motions, found themselves with no choice but to join the case publicly, and then to attempt every possible method they had at their disposal to ensure that Ruby was deemed imbalanced; was discredited as a witness; would continue to be subject to extensive psychiatric tests and examinations; and that they would retain control over Ruby from then on.

- I would suggest that they did in fact manage to do exactly that. I would specifically suggest that Jolly West was involved in the induction of Jack Ruby’s acute psychotic break, perhaps inducing it directly, and that a potent hallucinogenic drug like LSD was used. During that time, techniques like hypnotic suggestion may have also been used. The effect of this was that the defense – as led by Smith and supported by West – achieved everything they had always been seeking and had directly requested from the court.

- I would indicate that they did this to Ruby in order to secure control over him and any information he may have possessed. This enabled them to neutralize Ruby as a credible witness. They managed to do this shortly before Ruby testified to the Warren Commission in early June. During that testimony, he repeatedly asked Earl Warren to bring him to Washington D.C. so that he could testify safely about everything he knew regarding the Kennedy assassination and Oswald. As we know, Warren denied Ruby this opportunity.

- I would finally suggest that the ultimate conclusion that can reasonably be drawn from all of the above is the following. A small group of lawyers and psychiatrists with extensive, verifiable and direct connections to US intelligence agencies, primarily the CIA, and to all branches of the US military, worked systematically, with intent, to secure control over Jack Ruby, his credibility, his information, the popular perception of him, and essentially every other aspect of his life in order to prevent him from in any way revealing information that would pose a major threat to those same organs of US power. If Ruby did indeed possess just such highly threatening information, it must have related to his killing of Lee Harvey Oswald and thus to the entire official account of the JFK assassination and related events.

The author thanks Tom O’Neill and Jeffrey Kaye for their help and advice during the research and writing of the article.

Click here to read first of three parts.

Notes

[1] Chaos, Tom O’Neill, 2019, p.378.

[2] Ibid., p.495.

[3] Ibid.

[4] ‘OU Professor Aids on Ruby Trial Panel’, The Tulsa Tribune, November 30th 1963, p.8.

[5] ‘Psychiatrists Offer Aid in Ruby Trial’, Tom Laceky, The Daily Oklahoman, November 30th 1963, p.1 and 3.

[6] Ibid., ‘OU Professor Aids…’

[7] Ibid., ‘Psychiatrists Offer Aid…’

[8] Ibid.

[9] ‘Man Who Sold Shooting Photos Won’t Comment’, Corpus Christi Times, November 30th 1963, p.1 and 8.

[10] Ibid., ‘Psychiatrists Offer Aid…’

[11] ‘Weihofen Backs Court Action in Ruby Case’, The Albuquerque Journal, December 21st 1963, p.1.

[12] Letter from Weihofen to West, Nov. 30th 1963, UCLA archives, box 28, folder 1.

[13] Letter from West to Weihofen, December 20th 1963, UCLA archives, box 28, folder 1.

[14] Letter from West to Weihofen, February 13th 1964, UCLA archives, box 28, folder 1.

[15] ‘Psychiatrist Claims Disasters Don’t Step Up Mental Illness’, The Springfield News-Leader, February 7th 1957, p.12.

[16] U.S. Army Register, Volume 1, United States Army, Active and Retired List, 1st January 1966, Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, p.706. https://archive.org/details/officialarmyregi19661unit/page/706/mode/2up?q=%22albert+Julius+glass%22

[17] ‘Bellmon Denies Report Mental Shift Dropped’, The Tulsa Tribune, July 31st 1963, p.13.

[18] ‘Personnel Changes Okayed by OU Board of Regents’, The Norman Transcript, December 12th 1963, p.6. Also, Medical Education in Oklahoma, Mark R. Everett, 1972, p.341.

[19] ibid. p.290

[20] ‘The Early Years: Jolly West and the University of Oklahoma Department of Psychiatry’, Richard Green, The Journal of the Oklahoma State Medical Association (JOSMA), vol. 93, no. 9, September 2000, p. 446.

[21] Chaos, Tom O’Neill

[22] Tom O’Neill, October 2002 Interview with Shurley, O’Neill’s notes.

[23] Ibid., footnote 22, ‘The Early Years….’, Richard Green, JOSMA, vol. 93, no. 9, September 2000.

[24] Ibid. footnote 24, O’Neill’s notes from October 2002 interview with Shurley.

[25] Surreally, a participant at the event immediately prior to their evening talks was Jim Garrison. It was one of many mock trials which took place on these courses, and Garrison’s had this weirdly specific title: ‘Trial of a Case Allegedly Involving Homicide With A Blunt Instrument Where Defense Claims Decedent Came To His Death Accidentally by Negligently Setting Fire to His Bed While Intoxicated.’ It’s therefore likely that Garrison spent that afternoon debating that strange mock case in the presence of some senior MKULTRA doctors, one of whom was West; they may then have all had dinner together, as Garrison listened to their talks, four years before the assassination which ultimately consumed Garrison’s life and career.

[26] West to ‘Sherman Grifford’ letter, 11 June 1953, page 1

[27] Jay Shurley Interview with Tom O’Neill, October 2002, O’Neill’s notes.

[28] The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, July 1959, Vol. 7, Iss. 3, p.104-107.

[29] The History of Clinical Hypnosis from 1933-1971, Henry Lloyd Phelps, Jr., 1987, United States International University, p. 134.

[30] Ibid., p.170.

[31] Letter from Hubert Winston Smith to Harold Rosen, January 10th 1957, p.2. Dean Charles McCormick papers, UT Tarlton Law Library, Special Collections.

[32] West letter to Miss Freda Elliott, March 4th 1959, UCLA archives, Box 21, Folder 10.

[33] Jay Shurley 2002 interview with Tom O’Neill, O’Neill’s notes.

[34] ‘The Military Implications of Hypnosis’, George Estabrooks, undated, p.4. Estabrooks Papers, Colgate University.

[35] Letter to John C. Lilly from Hubert Winston Smith, December 13th 1957, Dean Keeton papers, UT Tarlton Library, Hubert Winston Smith folder.

[36] Ibid., p. 5-6.

[37] ‘Ex-CIA Doc Leads Fight to Limit Hypnosis’, Jeff Goldberg, High Times, January 1980. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP90-00552R000303090037-8.pdf

[38] Letter from Norman Garmezy to Louis Jolyon West, April 1st 1966, West papers. https://archive.org/details/jolyon-book-deal/mode/2up

[39] ‘New Lines of Defense Set In Ruby Case’, AP, The Durham Sun, March 25th 1964, p.1.

[40] ‘Smith Will Seek New Tests For Ruby’, UPI, The Palm Beach Post, March 26th 1964, p.23.

[41] ‘New Lawyer Plans Tests For Ruby’, UPI, The News-Herald, March 27th 1964, p.6.

[42] ‘Newest Attorney For Ruby Seeks Top Psychiatrist’, The Buffalo News, March 27th 1964, p.10.

[43] ‘Lawyer Indicates Ruby Would Testify’, The Knoxville News-Sentinel, March 27th 1964, p.15.

[44] ‘More Spending Means More Sales Tax Collection; State in ‘Black’’, Mirror Austin Bureau, The Gilmer Mirror, April 2nd 1964, p.9.

[45] ‘Defense Chief Visits Jack Ruby At Dallas Jail’, Corpus Christi Times, April 6th 1964, p.29.

[46] ‘Turnstile’, Thomas Thompson, Amarillo Globe-Times, April 9th 1964, p.2.

[47] ‘Judge Sets April 29 To Hear Ruby Trial Bid,’ The Post-Standard, April 14th 1964, p.8.

[48] ‘HWS to Ewalt’ letter, April 19th 1964, p.1, West UCLA archives.

[49] Ibid., p121.

[50] ‘T25 Report of Psychiatric Examination of Jack Ruby by Dr. Louis Jolyon West’, April 26th, 1964, Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza Collection, object number 20002.034.0002, p.1. https://emuseum.jfk.org/objects/21745/t25-report-of-psychiatric-examination-of-jack-ruby-by-dr-lo?ctx=c092f7f4ac446dc2c16ebd8f6d99d41d0cd06b37&idx=1

[51] ‘Case Number E. 4010-J. Full Proceedings, 1963-1964, p. 228-230. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1117918/m1/467/?q=%22jolyon%20west%22

[52] Ibid., p.234.

[53] Ibid., p.241.

[54] ‘News Clip: Ruby’, WBAP-TV, April 26th 1964, 3 min., 25 sec. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1390875/?q=jack%20ruby

[55] ‘News Script: Ruby’, WBAP-TV, April 26th 1964, p.1. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc959631/m1/1/?q=jack%20ruby

[56] ‘Report of Psychiatric Examination of Jack Ruby’, Louis Jolyon West, 26th April 1964, p.1. UCLA West papers.

[57] Brush With History: A Day in the Life of Deputy E.R. Walthers, Eric Tagg, 1998, p.88. https://archive.org/details/brushwithhistory–adayinthelifeofdeputye.r.waltherserictagg1998/page/n123/mode/2up?q=%22Ruby%22

[58] ‘Ruby Certain To Get Final Sanity Tests,’ UPI, The Lead Daily Call, April 27th 1964, p.1.

[59] ‘Ruby Mental Tests Refused By Court’, UPI, The Honolulu Star-Advertiser, April 28th 1964, p.2.

[60] ‘Notes on Burleson-Alexander Panel Discussion’, Radio-Television News Directors Association, WKY Studios, Oklahoma City, June 3, 1967. Notes by Elizabeth Price. Document in West’s UCLA papers, Box 164, Folder 3, p.1.

-

Review of The Plot to Kill President Kennedy in Chicago

The Plot to Kill President Kennedy in Chicago

by Vince Palamara

Vince Palamara begins The Plot to Kill President Kennedy in Chicago with a quote by Martin Martineau of the Chicago office of the Secret Service. In an interview from 1993 Martineau said that he was certain there was more than one assassin on 11/22/63. And he added that one reason he knew this was his own role in the investigation. A second was his knowledge of and experience with firearms.

Palamara then continues with a surprise phone call he got from a man named Nemo Ciochina. Ciochina had a go between actually do the calling. But he wanted to talk to Vince since he knew he was dying. And, in fact, he passed away about two months later. Nemo wanted to tell Vince that he was aware of his work. But he wanted to point out that, to him, the real conspiracy was in Chicago and not in Dallas. Nemo was in fact an agent in the Chicago field office who later served in Indianapolis. (Palamara, p. 6)

He wanted to give Vince some information he thought was relevant but had been ignored. But he specified that he wanted to leave his name out of things until after he had passed. The main piece of information that Nemo gave Vince was about a man who was named Lloyd John Wilson, which was an alias, but the most common one he used.

Wilson was in the Secret Service files as of September 10, 1963. And there were continuing reports on the man after 11/23. According to these reports Wilson had enlisted in the Air Force in late October of 1963 and been sent to Texas on November 2nd. (Palamara, p. 13). He was discharged from the Air Force on December 17, 1963 and turned himself in to the FBI a couple of days later. He said he was part of a plot to kill JFK. And he said he wrote a threatening letter he did not send. An anonymous caller to the FBI said he had seen the letter. (Palamara, p. 41) Wilson also claimed he paid Oswald a thousand dollars to kill Kennedy. (p. 16). Wilson said he left this letter in a hotel in Santa Clara, in northern California. But when the Bureau checked the room they did not find it. (p. 45). They concluded he was a nutcase.

But Wilson was interviewed on October 29, 1963. This was in Spokane after his file was flown in from San Francisco. The FBI took a ten page statement from him. The review was sent to an assistant US attorney named Carroll D. Gray in Spokane. Wilson denied to Gray that he was organizing a white supremacist group; said he did not now own any weapons; and he was looking forward to being in the Air Force. He also added that he did not mean he was going to kill JFK personally, but destroy him politically. (Ibid, pp. 47-49)

The case was closed, prosecution was not enacted, and Wilson went on to duty in the Air Force in Texas. Later on we learn that Wilson claimed to have met Oswald in San Francisco through a contact who heard Oswald was anti-Kennedy and had threatened the president. Wilson gave Oswald a thousand dollar bill and told him to go ahead. This was at the Cow Palace in either late August 1963 or early September 1963. Allegedly Wilson paid him with a thousand dollar bill. (Palamara, p. 60)

There are some problems with this story. To my knowledge, I have never seen any evidence that Oswald was in San Francisco at this time. And I also have never seen any evidence that Oswald came into a thousand dollars, which today would be the equivalent of ten thousand dollars in this time period. Wilson was discharged from the Air force on December 17, 1963 because he appeared to be mentally imbalanced. And I should add he also threatened President Johnson. (Palamara, p. 16)

Its good to get this information out there I think. And it probably would have been wise to maintain Wilson under some kind of surveillance. But I tend to agree with Mr. Gray that it seems to me that Wilson was simply unstable.

II

The author now picks up his real subject which are the major threats to JFK toward the end of his life. These include instances in El Paso in June of 1963, in Billings in September of 1963, the famous Joseph Milteer case, and the Walter telex made famous by Jim Garrison, which the author corroborates with a San Antonio telex of November 15, 1963. (Palamara, p. 79)

Palamara reveals a couple of new details on the November 18th Tampa threat. (p. 82) It turns out that Ted Shackley and William Finch assisted the Secret Service on this visit by JFK. And the original threat was “posed by a mobile, unidentified rifleman with a high powered rifle fitted with a scope.”

Palamara also mentions the famous Cambridge News story. This is one of the strangest events in the entire JFK case, which does not get enough attention. About 25 minutes before the assassination, the Cambridge News in Britain was given an anonymous tip. Someone called a senior reporter working the East Anglia area of England. The caller said there was going to be big news from the States very soon. He advised the reporter to call the American Embassy in London. The reporter then called MI 5, the British version of the FBI. The MI 5 said that the reporter had a reputation for being of sound mind with no prior record. (p. 86)

One of the most telling parts of the book is a section where the author compares the protection afforded Kennedy in Dallas with what happened in Tampa. Palamara lists eleven significant differences. (pgs. 104-06). This includes agents riding on the rear of the limousine, the guarding of nearby rooftops, Dr. George Burkley riding close to the president, and multiple motorcycles riding next to Kennedy in a wedge formation. The author points out that what makes this even more odd is that Tampa was the longest motorcade President Kennedy ever took domestically. Dallas was much shorter, so it should have been more manageable.

III

The book then focuses on several Secret Service agents who seem to have merited some special attention by subsequent investigations, but did not get it. We will deal with only five of them here.

Paul Paterni was a direct assistant to chief James Rowley. During World War 2, he served in Italy with James Angleton and Ray Rocca. Both men ended up being influential with both the Warren Commission and the Jim Garrison investigation. As the author learned from Chief Investigator Michael Torina, Paterni served in the OSS concurrently while on the Secret Service. (p. 115) Which mean that, potentially, Paterni would be a good nexus point for the CIA to have a listening post inside the Secret Service. It was Paterni who made Inspector Thomas Kelley liaison to the Warren Commission, where, to put it mildly, he performed questionably. Paterni was involved in the Protective Research Section about threats against JFK prior to the visit, and he reported none prior.

Forrest Sorrels was Special Agent in charge of the Dallas Secret Service field office. He took part in the dubious planning of the motorcade route. According to Palamara, Sorrels was involved in the 1936 route for FDR in Dallas, which used Main Street instead of Houston and Elm. (p. 118)

On November 27, 1963 the FBI was in receipt of a call from a woman who did not give her name. She said she was a member of a local theater guild, and on numerous occasions she had attended functions where Sorrels had spoken. She advised he should be removed from his position since he could not have protected Kennedy. She stated that Sorrels was “definitely anti-government, against the Kennedy administration, and she felt his position was against the security of not only the president, but the US.” (p. 118)

Mike Howard was an agent who was proficient at putting out rather unsound stories concerning the assassination. For instance, that a janitor had seen Oswald pull the trigger from the Depository building. It was Howard and Charles Kunkel who tried at first to manipulate Marina Oswald into saying her husband had been to Mexico City, an overture she first resisted. Howard was also one who effectively smeared Marguerite Oswald as being an eccentric and unreliable source. (pp. 134-36)

Roger Warner, like Paterni, served both in the CIA (12 years) and the Secret Service (20 years). He was also in the Bureau of Narcotics for three years. He was on the Texas trip when JFK was murdered and it was his first protective assignment. (p. 121) According to the late Church Committee witness Jim Gochenaur, Warner was the man who later accompanied fellow Secret Service agent Elmer Moore to Parkland Hospital with the Kennedy Bethesda autopsy in hand. They used that to align the Parkland witnesses not with what they saw, but what was in that very questionable document. (p. 125)

Of course, Palamara lists Moore as one of the agents about which an extensive inquiry should have been made. Jim Gochenaur talked about Moore at length in Oliver Stone’s films JFK Revisited and JFK:Destiny Betrayed. Not only was Moore involved in the Parkland doctors’ testimony, but Palamara notes that Moore was also involved in influencing Jack Ruby’s in a substantive way. This included his movements on the day before the assassination. (p. 125)

And it was not just Ruby and the Parkland doctors. As exposed in Secret Service Report 491, there is evidence that Moore was one of the agents involved in the interviews of Depository workers Harold Norman, Bonnie Ray William and Charles Givens. In that interview these men changed some of their testimony that they had given earlier, and in a dramatic way. For instance, in the later report Norman mentioned hearing a gun bolt working and cartridge cases falling on the floor above him. There was no mention at all of these noises in his November 26th FBI report. Or to anyone else prior to Moore getting the interview. (James DiEugenio, The JFK Assassination: The Evidence Today, p. 55)

To put it mildly, the Secret Service did not perform admirably either before, during or after the Dallas assassination.

IV

Palamara concludes the book with his examination of the threats against Kennedy emanating from Chicago in November of 1963. There was one early in the month and one late. The later one, on November 21st was suppled by informant Thomas Mosley who was negotiating a sale of machine guns to Homer Echevarria, part of the Cuban exile community. According to Mosley, an ATF informer, Homer said they now have new backers who are Jews, and they would close the arms deal as soon as Kennedy was taken care of. When Kennedy was killed, Mosley reported the conversation to the Secret Service. (Palamara, p. 154)

Echevarria was part of the 30th November Group which was associated with the DRE, who Oswald has associated with that summer. According to Mosley, the arms deals was being arranged and paid for through Paulino Sierra Martinez and his newly formed well financed group, Junta of the Government of Cuba in Exile.

Agent David Grant said that he had conducted surveillance on Mosley and Echevarria, prior to the assassination. All memos and files and notebooks went to Washington, and he was told not to talk about the case with anyone. For whatever reason this inquiry was later dropped.

Palamara adds that interestingly, Chief Jim Rowley had written an article for Reader’s Digest in November that outlined how easy it would be to assassinate a president using a high powered rifle. (p. 155) To say the least it was odd timing that went unnoted after the fact.

Earlier that November month, Rowley phoned the agent in charge in Chicago, Maurice Martineau. The FBI had gotten wind of an assassination plot featuring a team of four men. Martineau called in his men and briefed them on the call and said this inquiry was going to be hush hush. It would have no file number and nothing was to be sent by interoffice teletype. (p. 156). It was never made clear why this was so.

One of the most interesting parts of the book is the substantiation Palamara gives for this early November plot in Chicago. Over 7 pages the author lists 16 direct and indirect sources to prove such a plot was was in the making and that it was thwarted. It was not just journalist Edwin Black. Not even close. And like Sorrels, Martineau did not like JFK, especially his stand on integration. (p. 167)

The book concludes with Palamara’s discussion of Abe Bolden, recently pardoned by President Biden for a crime he very likely never committed. The frame up was clearly retaliation for Bolden trying to tell the Warren Commission about the early November Chicago plot. In fact, the man who set up Bolden later admitting to doing so. (p. 200). Plus there was a man, Gary McLeod, who tracked Bolden to Washington when he was trying to talk to the Commission.

The book ends by listing all the Secret Service failures that took place that day in Dallas that should not have been allowed to occur. But these led to the murder of Kennedy. Palamara lists 13 of them. This book shows—through descriptions of what happened in Tampa, Chicago, and Dallas and elsewhere–that for whatever reason, Kennedy was not getting out of 1963 alive.

-

Malcolm X lawsuit against FBI, CIA and NYPD filed

The family of murdered black civil rights activist Malcolm X is suing the FBI, the CIA and the New York police department. Read more.

-

Jack Ruby: A Review and Reassessment – Part 2

Jack Ruby : A Review and Reassessment – Part 2

By Max Arvo

During that first week after the shooting of Oswald, while Belli, Woodfield, Shore and Earl Ruby were making plans in California, other crucial individuals were inserting themselves into the Ruby case. One of these individuals was lawyer and doctor Hubert Winston Smith, who was, at the time of the trial, a faculty member at the University of Texas. He was a professor both in the Law School, based in Austin, and of the Medical Branch, based in Galveston. He also ran the Law-Science Institute, based out of the University, which he had established.

The intersection of law and science had been at the heart of Smith’s career since at least the mid-1940s. Born in Texas, Smith received his AB and MBA from the University of Texas (UT), before receiving his law degree from Harvard in 1930. He then practiced law in Dallas for two different firms, until he entered the medical school of Scotland’s University of Edinburgh. He then returned to Harvard to complete his medical training; after that, he was an associate in medical-legal research for three years on the Harvard Law and Medical Schools. During World War Two, he served in the US Navy, running the Legal Medicine Section of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. He then worked as a Professor of Legal Medicine at the University of Illinois from 1946 to 1949, at which time he moved to Tulane University in Louisiana, where he held three faculty appointments and ran a newly established Law-Science Program.

In 1952, he returned to UT. He founded the Law-Science Institute, which was tied to the University of Texas but, while there, he also founded the Law-Science Academy and Foundation. With these organizations, Smith’s law-science work became private, unaffiliated with any university, for the first time. The tension between these private entities and the law-science work tied to UT would ultimately be a primary reason behind Smith’s departure from UT in 1965.

All of Smith’s various law-science organizations offered courses which sought to share with attorneys the latest scientific and medical research and the various ways by which they might utilize it in court. They were attended by many of America’s foremost lawyers, scientists, doctors and psychiatrists. I have found syllabi, calendars and correspondence from almost all of the Law-Science courses Smith organized and attended between 1953 to 1964; those materials provide a detailed and extensive picture of Smith’s associations, closest colleagues, research, primary interests and activities throughout that time.

These materials, and various articles and other documents published during the trial, confirm that Smith had longstanding, close relationships with most, if not all, of the lawyers and psychiatrists who became involved in the Ruby case from the time Belli took the lead (between end of November to early December) to the time Smith left as defense lead, on June 3rd 1964. They also confirm that Smith’s involvement began months before he formally joined the defense team and that he was a hugely influential presence on Belli’s defense.

2.1 – Smith’s Early Involvement

The first three psychiatrists brought onto the Ruby case by any member of the Ruby defense team were Manfred Guttmacher, Walter Bromberg, and Roy Schafer. Belli himself wrote in his 1964 account of the trial Dallas Justice that Smith picked all three for him:

The scientists who examined Ruby for the defense, all recommended to us by Hubert Smith, were Dr. Roy Schafer…, Dr. Walter Bromberg…, and Dr. Manfred S. Guttmacher…. Dr. Schafer’s report was the building block for the others. … this brilliant scientist, after evaluating three days of psychological tests, unhesitatingly pinpointed the probable physical cause of Ruby’s mental troubles and put his findings on the line by suggesting—actually urging—neurological examinations to test them. [1]

Firstly, this confirms that Smith was involved directly in Belli’s defense at least as early as mid-December, because Guttmacher and Bromberg first examined Ruby on December 21st. This never seems to have mentioned during the trial, in court or to the press. It also doesn’t seem to have been discussed anywhere since.

This also confirms that Smith’s involvement as early as mid-December was crucial. Even if the selection of these psychiatrists was all Smith had contributed, his role would still have been decisive. The entirety of Belli’s defense – as he states in the quote above – was predicated on the examinations and conclusions of these three individuals. They were also the first medical professionals to examine Ruby since the shooting, with the exception of Holbrook, who had conducted a very brief examination of Ruby within a day of Oswald’s shooting.

It’s also worth stating the obvious but crucial point that Belli and the defense team would have been completely neutralized if medical experts, after examining Ruby, presented any doubt, hesitation or skepticism regarding the defense’s foundational claim that Ruby had killed Oswald during an episode of psychomotor epilepsy. They also announced that Ruby had this condition before any psychiatrists had examined Ruby, and without any evidence that Ruby had ever even suffered from anything remotely comparable to epilepsy, or had even suffered from any severe mental illness of any kind.

Belli’s defense team and the psychiatrists they introduced to the case therefore needed to work backwards from the assertion that Ruby had killed Oswald during an episode of psychomotor epilepsy. They needed psychiatrists to examine Ruby, and they then needed them to conclude that Ruby did indeed have that obscure condition; once they had done that, they then needed them to conclude that Ruby had suffered from a psychomotor epileptic episode during the Oswald shooting.

Smith therefore needed to be as sure as he could possibly be that the psychiatrists he selected would produce the results and conclusions they needed. By taking Smith’s recommendations, Belli therefore also must have had complete trust and confidence in Smith and in the doctors he chose. They simply could not afford to produce any examination results, analyses, conclusions or diagnoses which suggested anything other than that Ruby had psychomotor epilepsy at the time of the shooting.

Their evident confidence in both the legal strategy and that the doctors would conclude Ruby had the condition already seems somewhat surprising, and, from the outside, perhaps a tad premature and unfounded. Ultimately, however, the psychiatrists Smith selected did indeed produce exactly the conclusions they needed.

2.2 – Psychomotor Epilepsy