In Part 1 of this review, I covered some of the ways in which the Adam Curtis documentary Can’t Get You Out of My Head (hereafter CGYOMH) serves to misinform the audience about the nature of power in the US-dominated global capitalist system. In particular, I chose to focus on how CGYOMH deals with high finance and the international monetary system. These are realms that Curtis tendentiously obscures and distorts. In this installment, I am going to try and unpack his muddled and incoherent takes on Kerry Thornley, the JFK assassination in its historical context, and “conspiracy theory” in general.

JFK, the Prosecutor, and the Provocateur

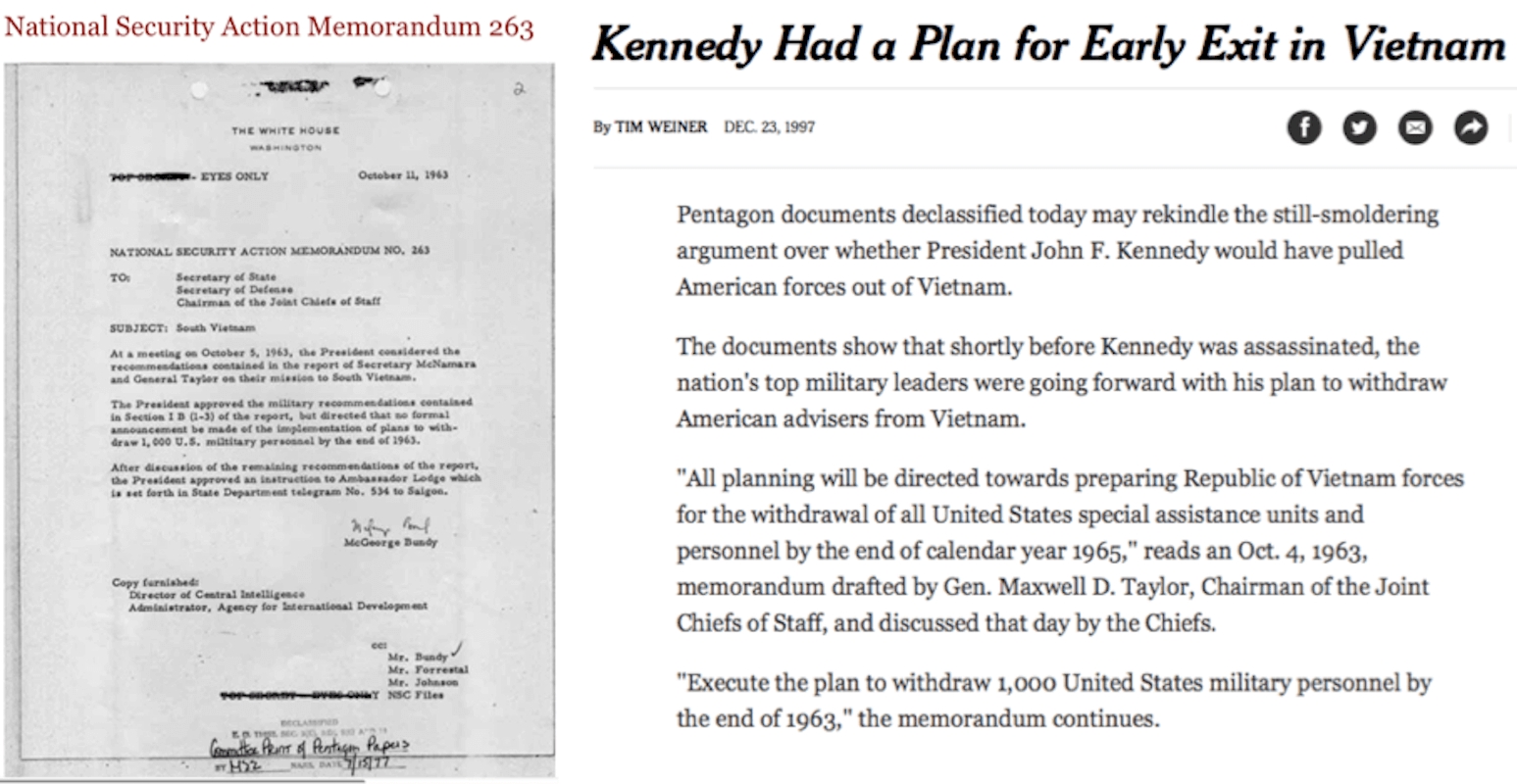

For some reason, Curtis decided to weigh in on the JFK assassination. This is an event that should be very relevant to topics and themes under discussion, namely: power, secrecy, the state, and conspiracy. Though there have been a lot of good books written about the JFK assassination, from the looks of it, Curtis apparently did not read any of them. If he had done so, there would have been many angles that he could have taken to discuss the case, even if he could not cover the assassination in a comprehensive manner. For instance, he could have talked about the impossibility of the magic bullet theory. He could have discussed the overwhelming number of witnesses in Dallas and Bethesda who reported a massive exit wound to the back of Kennedy’s head, indicating a shot or shots from the front. He could have read David Talbot’s Brothers and then discussed how RFK came to believe that his brother had been killed as the result of a right-wing plot involving elements of the CIA, the Cuban exile community, and organized crime. The audience might have also appreciated learning about how RFK was assassinated before he could attain the presidency and reinvestigate Dallas—something he explicitly said he would do. Or Curtis could have focused on how, beginning in the immediate aftermath of Oswald’s assassination, Establishment figures like Dean Acheson, Eugene Rostow, and Joseph Alsop began lobbying LBJ to create a “blue ribbon” commission that would arrive at a predetermined no-conspiracy conclusion. Additionally, Curtis could have revealed that as part of this exercise, LBJ used the specter of nuclear Armageddon to pressure Chief Justice Earl Warren and Senator Richard Russell into joining the commission.

Curtis didn’t do any of the above. Not even close.

For whatever reason, Curtis focuses on the figure of Kerry Thornley. In and of itself, this is not the worst choice. Thornley’s bizarre and implausible actions point very strongly to the conspiracy behind Dallas. But alas, it seems that since the grim implications of a coup d’état in Dallas would so dramatically falsify Curtis’ quizzically iconoclastic worldview, the director instead must offer a quirky and incoherent take on Kerry Thornley and his nemesis Jim Garrison. Regarding the Adam Curtis worldview that precludes him dealing with Dallas forthrightly, it is a difficult thing to pin down. Given that he has produced documentary films, totaling dozens and dozens of hours of runtime, it is noteworthy that one cannot get a clear grasp of what Curtis’ worldview actually is. I have to conclude that this is intentional on the part of the filmmaker, and that it is pretty dubious in and of itself. The easiest thing to say about his politics, which I mentioned in Part 1 of this review, is that he is anti-left. His anti-leftism takes an odd form, as he does not extol any obviously right-wing ideas. Instead, he often seems suspicious of power—especially technocratic power—but he seems even more suspicious of those who are suspicious of power. His detached, faux-anarchist analysis—for reasons I’ll not fully articulate—brings to my mind another British persona, the famed Bilbo Baggins. While I have a fondness for Tolkien’s The Hobbit, I would not look for someone like Bilbo Baggins to illuminate the dark pinnacle of capitalist imperium.

So, what does Thornley do for Curtis? He largely serves to allow Curtis to be dismissive of “conspiracy theories,” even as he is superficially ambivalent about actual conspiracies elsewhere in the film. The conspiracies he does acknowledge are attributed to conspirators of low to middling status or non-Westerners. The ultimately sad or pathetic conspirators include Michael X, Jiang Qing, the cops who entrapped some Black Panthers, and European Red Guards. Even when Curtis acknowledges CIA plots to overthrow governments in places like Congo, Syria, and Iraq, they are not explained as being part and parcel of the geopolitical strategy of US imperialism. Rather, Curtis seems to imply that these disastrous interventions are the product of bureaucrats who are in some way misguided. Though there are innumerable instances where such covert operations (i.e. conspiracies) can be easily traced back to a materialist motive, Curtis doesn’t seem to want to state this clearly or to hash out the implications. Even when he does acknowledge the postcolonial exploitation of the Third World, it seems to be some sort of piecemeal phenomena arising through random policy choices.

Thornley’s tale is curated so that he can play the role Curtis has in mind for him. It is deftly rendered and dispersed in random intervals throughout the eight-hour runtime of CGYOMH. The Kerry Thornley arc in CGYOMYH begins with Curtis telling us how Thornley and his friend Greg Hill went to a bowling alley where they disagreed about whether the universe was orderly or chaotic. They eventually came to the conclusion that the world was chaotic, but that individuals could use their minds to create some semblance of order. But then something strange happened. Thornley joined the Marines, where he met a young defiant man named Lee Oswald. He decided he would write a novel about Oswald. While Thornley was writing this novel, Oswald defected to the Soviet Union. As a right-wing Ayn Rand devotee, Thornley detested Kennedy. He did not mourn when JFK died. But the fact that the figure he cast in his novel was the president’s alleged assassin was, according to Thornley, “very weird.”

A little over two years before the assassination, Kerry Thornley moved to New Orleans with Greg Hill. They had begun to spin a spoof religion called Discordianism. Curtis states that around this time, Thornley got his Oswald novel published under the title, The Idle Warriors. This is an error; the novel did not get published until 1991—in the wake of Oliver Stone’s JFK. As Curtis would have it, Thornley ran into trouble because of the novel and the fact that—like Oswald before the assassination—Thornley was living in New Orleans in 1967. Thusly, Thornley “came to the notice of the man who was going to be the main creator of the JFK conspiracy theory…Jim Garrison.”

Curtis does not present Garrison favorably. He states that:

Jim Garrison believed that the modern democratic system in America was just a façade. That behind it was another secret system of power that really controlled the country, but you could never discover it through normal means because it was so deeply hidden.

Curtis reveals that Garrison wrote a memo entitled “Time and Propinquity” for his staff, in which he tried to explain how they might grapple with this secret government. Meaning and logic are always hidden and so they should instead look for patterns—strange coincidences and links that are apparently meaningless but in actuality evidence of the hidden system of power. Curtis asserts that Garrison’s theory would be a big impact on how many people would come to understand the world:

In a dark world of hidden power, you couldn’t expect everything to make sense. [I]t was pointless to try and understand the meaning of why something happened, because that would always be hidden from you. What you looked for were the patterns. And when Garrison read Kerry Thornley’s novel, he saw a pattern. Not only had Thornley been in the Marines with Oswald and written a novel about him, but he had come to live in the same city that Oswald had lived in before the assassination. And in 1967, Garrison accused Thornley of being part of the conspiracy. Thornley was furious; he knew that Garrison was wrong, but he also hated the very idea of conspiracy theories.

Thornley, Curtis tells us, believed that people in power used conspiracy theories to control people by making them believe that the world was run by hidden forces. This served to make individuals feel “weak and powerless.” Curtis does not bother to point out that Thornley is essentially positing a conspiracy theory to explain conspiracy theories. Thornley claimed that he wanted to free people from the conspiratorial thinking that held them back. He wanted to break people out of their “authoritarian conditioning.”

II

As he began to take on the CIA in the mid-1960’s, Garrison was necessarily flying blind to a certain degree. The massive clandestine intelligence community was something novel in the American experience. A few exposés of limited scope had been published in the 1960’s, most notably The Invisible Government by David Wise and Thomas Ross.[1] Ramparts magazine also published some important articles on the CIA in the 1960’s but, to put it mildly, Ramparts was an outlier in the US media landscape.

It wasn’t until the 1970’s that a fuller picture of the clandestine state began to emerge, thanks to the work of people like Daniel Ellsberg, Fletcher Prouty, Phil Agee, Victor Marchetti, Alfred McCoy, and Peter Scott. In terms of Garrison and the “Time and Propinquity” ideas that Curtis ridicules, the work of Scott is quite relevant. Writing about obscured intrigues related to the Vietnam War, covert operations in the Third World, mafia-intelligence nexuses, and the assassinations of the 1960’s, Scott came to realize that the existing methods of journalists, historians, and social scientists were insufficient in terms of being able to elucidate realities shaped by powerful clandestine actors. He coined the term parapolitics to describe “a system or practice of politics in which accountability is consciously diminished.”[2]

In the course of Garrison’s investigation, he wrote many memos to his staff. Only a relatively tiny number of them were related to “Time and Propinquity.” The overwhelming vast majority of his inquiry was done through on-the-ground investigation (e.g. going to the Dallas area and trying to interview suspects like Cuban exile Sergio Arcacha Smith). Curtis ignores that fact. Using a technique that originated with the late rightwing pundit Tom Bethell—who betrayed the DA—Curtis ridicules Garrison for these ideas. (Click here for details)

Garrison was merely trying to offer a strategy that might allow his office to do something heretofore not encountered—the successful prosecution of state actors whose crimes are supported by huge budgets, secrecy, and a license to covertly break laws in the name of national security. In fact, to bear this out, Garrison once wrote a memorandum to House Select Committee attorney Jon Blackmer about solving the JFK case. He said you could not solve this crime in the usual manner that felony investigations use (i.e. fingerprints, written records used as alibis, etc.). That would not work, because the JFK assassination was designed as a clandestine action.

What should be done if—as Garrison ascertained—politico-economic elites, clandestine state actors and insiders can veto the will of the public by assassinating a democratically elected head of state? What if, additionally, it becomes clear that the national media and academia are under the hegemonic sway of the same elite of power, and thus cannot act institutionally as the democratic checks described in liberal political theory? Ultimately, Curtis can offer no alternative to parapolitical research or Garrison’s foray into the realm.

In the face of this, Curtis instead blithely asserts:

Thornley was right that most of what Garrison alleged was complete fantasy. Despite all the patterns, he could produce no evidence of a hidden conspiracy.

If the reader can believe it, this is Curtis’ last word on Garrison. He does not mention that Garrison had convinced the jury at the Clay Shaw trial that the assassination was the result of a conspiracy. That was accomplished through one exhibit and two key witnesses. The witnesses were Dr. John Nichols for the prosecution and the second was the devastating cross examination of defense witness and Kennedy pathologist Dr. Pierre Finck. The exhibit was the Zapruder film, which Nichols’ used to convincingly demonstrate a shot came from the front. This showed, at the least, that Lee Oswald was not the only assassin firing at Kennedy, which would mean JFK was killed by a conspiracy. So it’s convenient for Curtis to leave it out.

Garrison also discovered that Oswald had been in New Orleans as an ostensibly pro-Castro activist, but had been working out of the office of Guy Banister—a hard-right, ex-FBI man who ran the Anti-Communist League of the Caribbean, was a member of the fascist “Minutemen” organization, and had been involved in anti-Castro CIA operations like the Bay of Pigs and Operation Mongoose. Given that Oswald’s New Orleans activities only served to discredit the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, the obvious inference would be that Oswald was a pawn in some kind of counterintelligence operation. The Zapruder film was so definitive that when it was finally shown on network television in the 1970’s, public support for the Warren Commission fell to all-time lows.[3]

Years later it was revealed that Clay Shaw lied on the stand numerous times. (Click here for details) He was also getting considerable support from the CIA during the trial. And, just as Garrison alleged, Shaw had indeed perjured himself when he stated that he had had no relationship to the CIA. Additionally, there is no excuse for Curtis’ failure to mention that the last official word on the JFK case—the HSCA investigation—concluded that the assassination was the result of a “probable conspiracy.” He then also fails to disclose to the audience that the chief counsel of the HSCA eventually signed on to a petition which stated that the culprits were elements of the US national security state.[4]

Curtis and Conspiracy

Upon returning to Thornley and Discordianism, CGYOMH details how the group decided to use Playboy magazine to launch “Operation Mindfuck.” They kicked off the operation by submitting a fake letter positing that all the political assassinations in the US were the work of “the [Bavarian] Illuminati.” The Discordians began to spread this notion throughout the pop culture landscape. Thornley, Curtis states, was trying to break the spell of conspiracy theories by exposing the absurdity that a secret society in Bavaria could be covertly ruling the word. Here again, Curtis does not bother to point out that the Discordians were conspiring to discredit conspiracy theorizing. Any explanation of Operation Mindfuck is by definition a conspiracy theory. To acknowledge this truism would entail something that Curtis does not want to admit or explain: that any conspiracy theory—like any no-conspiracy theory—should be judged on its respective merits.

One of many dispiriting aspects of CGYOMH is that Thornley and Operation Mindfuck are actually interesting subjects whose reexamination could offer fresh insights. The work of the illustrious and iconoclastic Florida State professor Lance DeHaven-Smith is instructive in this regard. By the end of the year 2000, DeHaven-Smith had already enjoyed an accomplished career as a scholar of public administration. However, as the top authority on Florida state politics, he was shocked when George W. Bush’s team was able to steal the 2000 election, committing multiple felonies in the process.[5] This experience radicalized the professor and led him to coin the term state crimes against democracy (SCADs). He defined SCADs as “concerted actions or inactions by government insiders intended to manipulate democratic processes and undermine popular sovereignty.”[6]

Upon being forced to reassess historical events that he had lived through, DeHaven-Smith came to be alarmed by the strong social and academic norms which served to discourage and stigmatize reasonable suspicions of conspiratorial state criminality. In 2013, he published Conspiracy Theory in America. There he detailed the ways in which powerful actors and institutions have aided and abetted SCADs by stigmatizing those who posit conspiratorial explanations of politically significant events:

Most Americans will be shocked to learn that the conspiracy-theory label was popularized as a pejorative term by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in a propaganda program initiated in 1967. This program was directed at criticisms of the Warren Commission’s report. The propaganda campaign called on media corporations and journalists to criticize “conspiracy theorists” and raise questions about their motives and judgements. The CIA told its contacts that “parts of the conspiracy talk appear to be deliberately generated by Communist propagandists.” In the shadows of McCarthyism and the Cold War, this warning about communist influence was delivered simultaneously to hundreds of well-positioned members of the press in a global CIA propaganda network, infusing the conspiracy theory label with powerfully negative associations.[7]

DeHaven-Smith refers to this episode as “The CIA’s Conspiracy-Theory Conspiracy.”[8] Given that, as referenced above, the CIA was conspiring in 1967 to use its propaganda assets to manipulate public discourse around conspiracy concepts in the JFK assassination and given that 1968 would see another pair of cataclysmic assassinations of progressive leaders—MLK and RFK—does not the Discordians’ Operation Mindfuck plot dovetail perfectly with the Agency’s goal of stigmatizing conspiracy theorizing around suspicious political events? As we will see, this becomes all the more apparent when one looks at the overwhelming amount of evidence that Kerry Thornley was an intelligence asset involved in creating the legend that made Oswald a suitable designated culprit in the JFK assassination.

III

At the end of the first episode of CGYOMH, Curtis dismisses the idea of conspiracy in the JFK assassination. Thereby implicitly endorsing the Warren Commission’s conclusion that the president was assassinated for no discernable reason by a “lone nut”; who was subsequently assassinated by a concerned local pimp in a room full of policemen. Curtis invokes the tired JFK trope which explicitly or implicitly posits that since there are so many different wacky JFK conspiracy theories—featuring the KGB, the KKK, J. Edgar Hoover, the mafia, Castro, Nixon, the CIA—none of them can be valid. For those of us who feel that the truth of the JFK assassination is pretty obvious, Curtis is another example of a person who would accept, say, the magic bullet theory, rather than suffer the cognitive dissonance of acknowledging despotic political realities in the nominally “liberal democratic” West.

Postwar Deep Politics

Curtis cannot truly grapple with deep politics: “all those political practices and arrangements, deliberate or not, which are usually repressed rather than acknowledged.”[9] This does not set him apart from mainstream historians and political commentators in the West. What is noteworthy about Curtis is that he produces so much work that delves into these areas, while always coming up with tendentious, limited-hangout summations, analysis, and conclusions. If it wasn’t obvious, this is why I chose to title this review “Deep Fake Politics.”

His intervention into Dallas has already been discussed above. Additionally, he looks into other important episodes as though he is going to reveal something important, while invariably coming up with a narrative that is less than we already know. Or less than we should know were we not so propagandized and beguiled by our Western sense-making institutions. For example, Curtis states that some radicals in the West believed that the Nazi system was hiding behind the liberal façade. This is an important and fascinating issue. To what extent did key figures and institutions from the defeated Axis powers continue to exist postwar, in some form or another? We know that the US made use of notorious Nazis like Klaus Barbie, Reinhardt Gehlen, and Otto Skorzeny—as well as Nazi scientists like Wernher von Braun.

Furthermore, the German economic elites of the Nazi era were also allowed to retain power and wealth in the postwar system. The Nazis were brought to power by an elite group of German industrialists, whose cartel system gave them control over the commanding heights of the German economy. After the war, James Stewart Martin was the director of the Division for Investigation of Cartels and External Assets in American Military Government. In that position, he was charged with breaking up the Nazi cartel system and investigating its ties to Wall Street. His efforts were undermined by his superior officer, a man who had been an investment banker before the war. Stewart chronicled these events in a book published in 1950, concluding that “we had not been stopped in Germany by German business. We had been stopped in Germany by American business.”[10] Curtis chooses not to explore this issue deeply, leaving the impression that those who detect any semblance of Nazism under postwar US hegemony are fringe radicals or idealists, certainly not sober observers offering a historically grounded assessment. In postwar Japan, the situation was also similar. The US made use of sinister war criminals like Yoshio Kodama and largely preserved the Japanese elites who presided over the massive zaibatsu corporate conglomerates. I recall that in one interview, the illustrious Japan expert Chalmers Johnson made a quip about the Sony Walkman in the 1980’s, “From the people who brought you Pearl Harbor.”

The Pivotal 1970’s

In episode three, Curtis looks at Watergate and the tumultuous, poorly understood 1970’s. He describes Nixon as a paranoid man, obsessed with perceived enemies. He describes Nixon as having come to power thanks to the “silent majority” of Americans who felt isolated and alone. In other words, there is no mention of two crucial political crimes: the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy and the 1968 “October counter-surprise,” in which candidate Nixon sabotaged peace talks in Paris that could have ended the war before the 1968 election. (Click here for details)

Robert Kennedy was planning to reinvestigate his brother’s assassination, believing—as did Jim Garrison—that JFK was murdered as the result of a conspiracy involving elements of the national security state, the Mafia, and Cuban exiles. This merits no mention from Curtis. Instead, Nixon and other Americans of the time were just feeling less connected and more paranoid, because of Vietnam. We are told about Nixon’s paranoia about the liberal establishment and his enemies list. His taping system recorded his paranoia. The president became obsessed with trying to destroy his “imaginary enemies.” To that end, Richard Nixon—one “of the most powerful people in the world”—kicked off a White House conspiracy that involved using ex-intelligence agents to crush his opponents. The Plumbers’ activities would expose Nixon’s criminality in the Watergate scandal. Says Curtis, “[I]n its wake, all kinds of other revelations came out—of dark secrets in the political world that had been kept hidden from the people…For twenty years, the CIA had been planning assassinations and overthrowing leaders of foreign governments all around the world using poisons and specially made secret weapons.”

IV

To say that this is an elision is not nearly strong enough. It makes one ask: Adam, what did you read in preparation?

Nixon’s enemies were hardly imaginary. They were not confined to any “liberal establishment.” Nixon was being spied on by a cabal of right-wing Pentagon officials who were eventually caught red-handed. This is called the Moorer/Radford affair. (Click here for details) Further, as the late Robert Parry demonstrated, the origins of the Plumbers Unit was not over the release of the Pentagon Papers, as previously imagined. It was over the Lyndon Johnson/Walt Rostow memo exposing the 1968 October Surprise by Nixon and Claire Chennault. (Click here for details) It is really hard to fathom how Curtis missed these key historical points.

Perhaps more significantly, Nixon could not get the CIA to cooperate with him in a number of key areas, including the president’s attempts to obtain all the CIA files which might explain the JFK assassination and the Bay of Pigs operation. (Click here for details)

Nixon eventually fired Dick Helms, the director of the CIA, and ordered his successor, the outsider James Schlesinger, to compile all information about CIA crimes. He took these actions, in part, because he believed that the CIA was somehow involved in the Watergate scandal. There were good reasons for his suspicions. Two key Watergate figures—James McCord and E. Howard Hunt—were “former” CIA officers, were politically to Nixon’s right, and were so operationally incompetent that many suspect that they intentionally bungled their crimes as part of an operation to damage or gain control over the president.[11]

The report of the CIA’s violations came to be known the “Family Jewels” and some of its contents were leaked to the press. These revelations, plus Watergate, eventually gave rise to two congressional investigations of the intelligence community. It is important to note that these leaks about Nixon, and about Nixon’s adversaries like the CIA, were part of what can be described as an Establishment civil war. To say that Nixon was merely paranoid about his liberal enemies is to greatly distort this history. Furthermore, such an explanation cannot explain how the ouster of Nixon led to the US lurching far to the right politically. Both major parties became more conservative. The liberalism of the Kennedys was excised from the political power structure. The Republicans became a Reaganite party and the Democrats adopted positions that had previously been associated with Rockefeller Republicanism, cultural politics notwithstanding.[12]

Thornley: Conspiracist or Conspirator?

Years after launching Operation Mindfuck, Thornley says he saw E. Howard Hunt’s photo after his Watergate arrest. He now recognized Hunt from his New Orleans days, when he also knew Oswald (although he was very reluctant to admit this, and one could argue he did not).

And then, strangely, Thornley also recalled how he had known Guy Bannister and Clay Shaw, suspects in Jim Garrison’s investigation. Previously, Thornley had disregarded these matters. Suddenly, says Thornley, “I could not explain all these weird coincidences.” While the Operation Mindfuck hoax/operation promulgated an Illuminati meta-conspiracy theory, these bogus theories were getting mixed up with real world intrigues like CIA mind control and other scandals. Says Curtis, “The line between the reality of political corruption and a dream world of conspiracy theories started to get blurred in America.” Kerry Thornley, Curtis suggests, became swept up in this paranoid thinking. Thornley came to believe that the CIA had somehow manipulated him into setting up Operation Mindfuck, but he didn’t know how. Says Curtis, “Thornley had retreated into a dream world of conspiracy.”

V

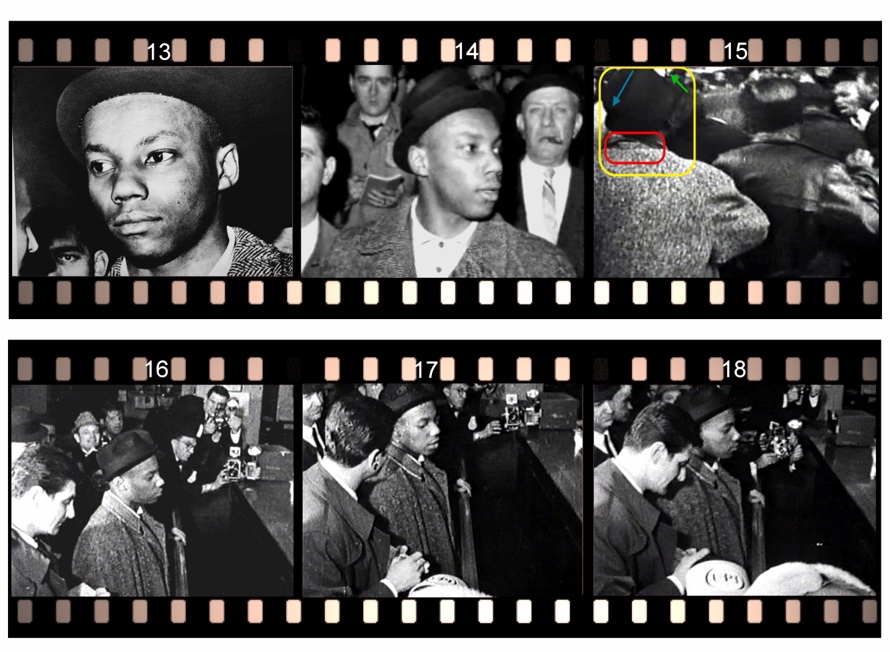

For viewers not steeped in the JFK assassination, Curtis’ depiction of Thornley would not raise much suspicion. He would seem like a wacky and unlucky character, who wound up facing some troubles because of a bizarre set of coincidences. However, Curtis leaves out a tremendous amount of material that complicates matters considerably. Let us fill in what Adam Curtis could not find out about Kerry Thornley.

For one thing, Thornley was an extreme right-winger and Kennedy hater. He was a devotee of Ayn Rand,[13] but his politics were even more reactionary than mere libertarianism. He had been a strong supporter of the Belgian scheme to recolonize Congo by creating a breakaway state in the resource rich province of Katanga. This was a vicious plan that was ultimately thwarted by President Kennedy after the assassination of Patrice Lumumba and the death—likely the assassination—of UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold. Thornley cited Katanga as one of the main reasons he hated Kennedy. When Kennedy was killed, Kerry couldn’t help himself: he began singing while at his restaurant job. He later urinated on Kennedy’s grave. In a 1992 interview for the television program A Current Affair, Thornley stated about Kennedy, “I would have stood there with a rifle and pulled the trigger if I would have had the chance.” Summing up Thornley’s politics, Jim DiEugenio writes, “What kind of person would celebrate the murder of Kennedy and the victory of colonial forces seeking to exploit both the native population and vast mineral wealth of Congo? […] I would call those kinds of people fascists.”[14]

There are more key facts and events that Curtis omits from his tale. The Thornley and Hill move to New Orleans in February 1961 has never been adequately explained. It strains credulity to think that it was in response to a cop accusing the pair of loitering. New Orleans at that time was quite a place for a budding fascist to be. Right at the time of their arrival, preparations for the Bay of Pigs invasion were ramping up. Ultra-rightists and Garrison suspects like David Ferrie and Guy Bannister were involved in these operations, conducted at locales such as the Belle Chase naval air station and Banister’s 544 Camp Street office.[15] Upon arriving in New Orleans, Thornley began associating with these hard-right, CIA connected circles. When Garrison’s office questioned Kerry Thornley in 1968, he denied that he knew Guy Banister, David Ferrie, or Clay Shaw. However, in the mid-1970’s, when the HSCA investigation was about to begin, Thornley admitted that, in fact, he had known all of these characters. Furthermore, when his book on Oswald, The Idle Warriors, finally got published in 1991, Thornley admitted in the book’s introduction that he showed the manuscript to Guy Banister back in 1961.[16]

Just prior to Thornley’s arrival in New Orleans, Banister was linked to a shocking incident. The Friends of Democratic Cuba (FDC) was a CIA/FBI shell company. Guy Bannister was one of its incorporators, and two other FDC members at times operated out of Guy Bannister’s 544 Camp Street office. In late January 1961, two men walked into a Ford Truck dealership claiming to be members of the FDC. They were looking to buy ten Ford Econoline vans. The man who did the negotiating was Joseph Moore, but he wanted his colleague to co-sign. The man co-signed simply as “Oswald” and told the dealer that his name was Lee.[17]

It is hard to take seriously any non-conspiratorial explanation of these events. Thornley decided to write a novel based on a not-especially-interesting marine who defected to the Soviet Union. While this hapless Marxist was in Russia, some CIA assets were impersonating this wayward young marine while conducting FDC/agency business. Then Thornley whimsically decided to show up in New Orleans, where he happens to meet Guy Banister—one of the figures involved in creating the FDC. So, he shows Banister the novel he has written about Oswald, the same guy that Bannister’s FDC associates are impersonating. And apparently Adam Curtis doesn’t bat an eyelash.

In testimony before the New Orleans grand jury, Thornley denied that he had associated with Oswald during Oswald’s time in New Orleans. This was implausible given that they had known each other in the Marines, that Thornley had written a novel about Oswald, and that the two men knew many of the same people and frequented the same places. In fact, Garrison had at least eight witnesses who had seen Thornley and Oswald together during that summer. Two of these witnesses stated that Thornley had told them that Oswald was, in fact, not a communist. Garrison had a witness who said that she, “her husband, and a number of people who live in that neighborhood saw Thornley at the Oswald residence a number of times—in fact they saw him there so much they did not know which was the husband, Oswald or Thornley.”[18]

In that 1963 summer in New Orleans, Oswald was famously arrested while passing out Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC) leaflets. The New Orleans Secret Service investigated this incident and eventually looked into the company that printed the FPCC leaflets.[19] In Never Again, researcher Harold Weisberg wrote that,

[When] the Secret Service was on the verge of learning, as I later learned, that it was not Oswald who picked up those handbills, the New Orleans FBI at once contacted the FBI HQ and immediately the Secret Service was ordered to desist. For all practical purposes, that ended the Secret Service probe—the moment it was about to explode the myth of the “loner” who had an associate who picked up a print job for him.[20]

As an investigator for Garrison, Weisberg interviewed two of those print shop employees. They identified Thornley, not Oswald, as the person who picked up the FPCC flyers. When Weisberg told Garrison investigator Lou Ivon about this, Bill Boxley—a CIA infiltrator in Garrison’s office—tried to distort and downplay the significance of the event. However, Weisberg had surreptitiously recorded one of those interviews and the recording served to quiet Boxley. Unfortunately, the tape—like many of Garrison’s files—soon disappeared.[21]

Thornley also denied to the Garrison team that he knew Carlos Bringuier and Ed Butler. Bringuier was part of the CIA-backed Directorio Revolucionario Estudantil (DRE) and Butler ran Alton Ochsner’s CIA-backed Information Council of the Americas (INCA). Thornley did eventually admit that he knew both of these men.[22] Butler and Bringuier were both involved with Oswald in an infamous radio debate. This followed Oswald’s arrest after a confrontation with Bringuier, during his strange FPCC leafleting spectacle. In the radio debate, it was revealed that Oswald was a Marxist who had previously defected to the Soviet Union. This served to discredit the FPCC by associating it with communism and the Soviet Union. As many people have noted, this seems to have been the objective that Oswald believed he was furthering—some sort of psychological operation for propaganda purposes. If there were any doubt about this, it should be dispelled by the fact that the flyers were stamped with Guy Banister’s 544 Camp Street address.

VI

In summary, Thornley, Bringuier, and Butler were all instrumental in creating the evolving Oswald legend. Thornley first did so by depicting Oswald in The Idle Warriors as a communist malcontent in the Marines. Then he furthered Oswald’s legendary persona through his and his associates’ activities in New Orleans. If Weisberg is correct, this may have included assisting Oswald in his FPCC leafleting spectacle. That playlet got Oswald arrested and led to the infamous radio interview with Butler and Bringuier. On the day of the assassination, the CIA—via Bringuier’s DRE—quickly formulated the first JFK conspiracy theory: that Oswald was in some way an agent of Castro’s Cuba.

Less than 24 hours after the assassination, conservative Senator Thomas Dodd had Butler brought to Washington, so the propagandist could offer congressional testimony about Oswald. Thornley, who referred to the assassination as “good news,” was interviewed by the Secret Service 36 hours after the assassination and by the FBI a day later. Just days after the assassination, Thornley abruptly left New Orleans with ten days of rent left on his apartment. He went to Arlington, Virginia and was eventually called to testify to the Warren Commission. Conforming to the new cover story of Oswald as a discontented lone nut, Thornley’s testimony offered lots of psychology analysis that would never have been admissible in court. However, this sort of testimony suited the Warren Commission perfectly well.[23]

Years after the Warren Report was issued, Thornley—as mentioned above—went on to perjure himself before a grand jury in New Orleans about not knowing or meeting Oswald during that brief but spectacular summer in New Orleans. At one point, Thornley agreed to meet with a Garrison investigator, but only if the meeting were held at NASA. Given Thornley’s low status in conventional terms, it is hard to understand how he could command entry to such a location. NASA also happened to be the place where several of Oswald’s former co-workers at the CIA-connected Reily Coffee Company would later find employment. The task of locating Thornley in the first place was also a challenge for Garrison’s staff. Eventually, it was discovered that he was in Florida. Thornley, who since leaving the military had only held jobs as a waiter and a doorman, had two homes—one in Tampa and one in Miami.[24]

Following the Garrison investigation, Thornley faded from notoriety. He only reemerged in the mid-1970’s at around the time that the HSCA began reinvestigating the JFK assassination. At this point, Kerry reappeared as some kind of iconoclastic, hippie burnout—albeit one with ultra-rightist politics. Suddenly, Thornley did a complete reversal on the question of conspiracy. He admitted knowing many of the targets of Garrison’s investigation. He even sent Garrison a long manuscript which detailed his strange version of a plot behind Dallas.[25] This document is but one of the elaborate disinformation ruses that Garrison received at different times. Two other infamous and more elaborate examples were the manuscripts Nomenclature of Assassination Cabal and Farewell America.

Though Thornley at this point admitted knowing Ferrie and Bannister, and even E. Howard Hunt, he claimed that these were not the real conspirators. Absurdly, Thornley was then asserting that the actual plotters were characters known as Slim, Clint, Brother-in-law, and Gary Kirstein.[26] Kerry said he later figured out that two of these men were Hunt and Minuteman Jerry Milton Brooks under pseudonyms. This is but one example of how the HSCA, like the Garrison investigation, was beset by disinformation agents. Besides Thornley, figures like Marita Lorenz and Claire Booth Luce led HSCA investigators on many pointless diversions.[27] John Newman has recently argued that Antonio Veciana was doing something similar to HSCA investigator Gaeton Fonzi by exaggerating the importance of David Atlee Phillips and by distracting from the relationship between army intelligence and Veciana’s Alpha 66 unit.[28]

Conclusion

Thornley’s activities, and his perjury about them, are completely bizarre and inexplicable, unless one posits that he is a low-level intelligence operative. When one looks at these episodes with that possibility in mind, all the otherwise ridiculous episodes are quite logical. The same holds true for Thornley’s famous friend, Lee Harvey Oswald. In Oswald’s case, his Marine discharge, defection, repatriation, Dallas associations, New Orleans escapades, Mexico adventures, and behavior during his last days are all impossibly weird—unless and until the intelligence angle is examined. Unfortunately, this is how we must approach facts and evidence in para-political contexts. The Warren Commission’s official story, and Thornley’s key role in creating that transparent myth—he is quoted three times in the Warren Report to characterize Oswald—simply collapses under this kind of analysis.

The JFK assassination should be recognized as a state crime against democracy in the context of America’s deep political system. Such an understanding points to the existence of a despotic, exceptionalist state that can exercise veto power over democracy. Unsurprisingly, this is not a perspective that Curtis and the BBC would look to promote. Predictably, CGYOMH opts to ridicule and dismiss Garrison and critics of the Establishment’s JFK assassination theory[29]—the theory of the lone nut who gets killed by another lone nut, i.e. the dual nut theory.

All of this is not to say that Garrison was beyond reproach. He should not have been so trusting with the volunteers he allowed to work on the case. He should have indicted Ferrie sooner, lest his main suspect succumb to a deadly brain aneurysm whilst sitting on the couch looking at two typed, unsigned suicide letters. Furthermore, given all the things that have come out about Kerry Thornley, Garrison arguably should have sought to prosecute him rather than Clay Shaw. One reason to argue that Garrison should have gone after Thornley for conspiracy to commit murder comes from Thornley himself. Said Kerry Thornley, “Garrison, you should have gone after me for conspiracy to commit murder.”[30] Admittedly, Thornley was positing a contrived hoax, but even this JFK disinformation is of a piece with his prior roles in Oswald’s framing and in the cover-up after the fact.

For Curtis to omit so many crucial facts about the JFK assassination, about Kerry Thornley, and about Garrison’s case is useful to his cause. It allows him to ignore the history-making interventions of the deep state and the extent to which these interventions have helped bring about the political nadir that America is experiencing. Curtis’ obscurantism allows him to downplay American state criminality as merely “political corruption”: the regrettable result of various technocratic bureaucrats holding and acting on bad ideas while trying to impose order on a chaotic and unpredictable world. He omits, distorts, and cherry picks facts to present his interminable exploration of our current dystopia. In so doing, CGYOMH obscures what may be the most salient historical development of the postwar US-led world order—the criminalization of the state.

In Part 3, I will examine (1) how Curtis fails to reckon with the nature of the state in the West, (2) how this precludes him from grappling with the realities of US foreign policy, and (3) how this dovetails with his tendentious and chauvinistic depictions of the chief US rivals, Russia and China.

Postscript:

Adam Curtis apparently never looked at this article which demolishes his entire view of both Thornely and Garrison. (Click here for details)

see Deep Fake Politics (Part 1): Getting Adam Curtis Out of Your Head

see Deep Fake Politics (Part 3): Empire and the Criminalization of the State

[1] David Wise and Thomas B. Ross, The Invisible Government (New York, NY: Random House, 1964).

[2] Peter Dale Scott, The War Conspiracy (New York, NY: Bobbs Merrill, 1972).

[3] Kathryn Olmsted, Challenging the Secret Government: The Post-Watergate Investigations of the CIA and FBI (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), p. 99.

[4] M.D. Gary Aguilar et al., “A Joint Statement on the Kennedy, King, and Malcolm X Assassinations and Ongoing Cover-Ups,” The Truth and Reconciliation Committee, 2019.

[5] See: Lance DeHaven-Smith, ed., The Battle for Florida: An Annotated Compendium of Materials from the 2000 Presidential Election (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2005).

[6] Lance deHaven-Smith, “Beyond Conspiracy Theory: Patterns of High Crime in American Government,” American Behavioral Scientist 53, no. 6 (February 16, 2010): pp. 795–825.

[7] Lance DeHaven-Smith, Conspiracy Theory in America (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2013), p. 20.

[8] DeHaven-Smith, Conspiracy Theory in America, p. 20.

[9] Peter Dale Scott, Deep Politics and the Death of JFK (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993), p. 7.

[10] James Stewart Martin, All Honorable Men: The Story of the Men on Both Sides of the Atlantic Who Successfully Thwarted Plans to Dismantle the Nazi Cartel System, ed. Mark Crispin Miller, vol. 21, Forbidden Bookshelf (New York, NY: Open Road Media, 2016).

[11] See: Jim Hougan, Secret Agenda: Watergate, Deep Throat, and the CIA (New York, NY: Random House, 1984).

[12] For a longer discussion of this, see: Aaron Good, American Exception: Empire and the Deep State (New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing, 2022).

[13] James DiEugenio, “Kerry Thornley: A New Look (Part 1),” Kennedys and King, June 13, 2020.

[14] James DiEugenio, “Kerry Thornley: A New Look (Part 2),” Kennedys and King, June 14, 2020.

[15] DiEugenio, “Kerry Thornley: A New Look (Part 1).”

[16] James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012), p. 189.

[17] DiEugenio, “Kerry Thornley: A New Look (Part 1).”

[18] DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, p. 189.

[19] DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, p. 190.

[20] Quoted in: DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, p. 190.

[21] DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, p. 190.

[22] DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, p. 191.

[23] DiEugenio, “Kerry Thornley: A New Look (Part 1).”

[24] DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, p. 191.

[25] DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, pp. 191-192.

[26] DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, p. 192.

[27] See: Gaeton Fonzi, The Last Investigation (New York, NY: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1993).

[28] See: John M. Newman, “Antonio Veciana, Mystery Man in JFK Assassination, Part 1,” Who. What. Why., February 5, 2019.

[29] I write “Establishment’s” because the final official word on the assassination remains the HSCA conclusion of a “probable conspiracy.” Given this fact, it is telling that the dominant media still defends the Warren Commission—a body whose work was found inadequate—first by the Church Committee and then by the HSCA Congressional investigation.

[30] DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case, p. 192.