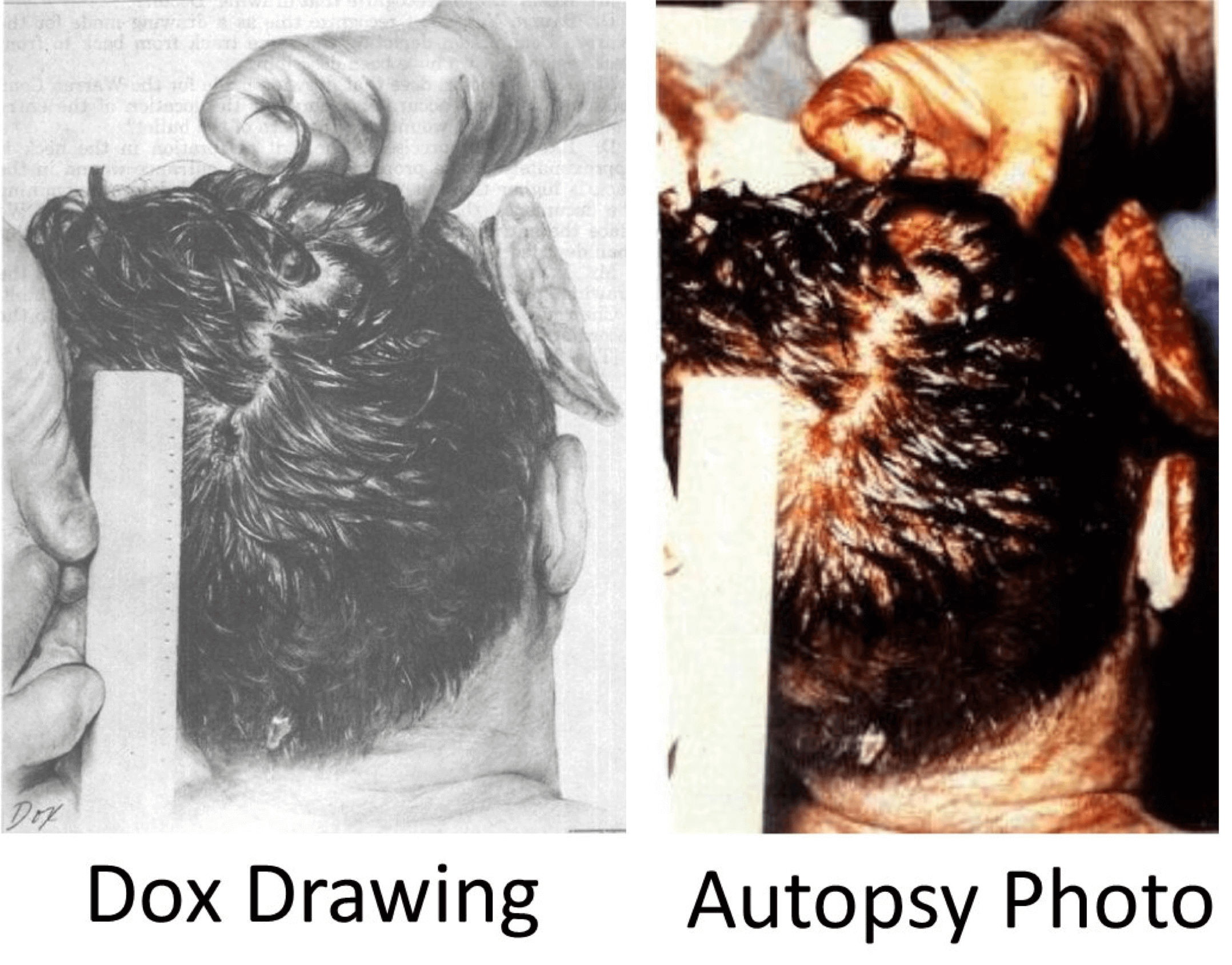

It is worth noting that in the decades that followed the release of the HSCA report, other medical experts such as neuropathologist Dr. Joseph Riley and forensic pathologist Dr. Peter Cummings have viewed the autopsy materials and agreed with the original entry location proposed by the autopsy surgeons. On the other hand, the three forensic specialists who viewed the photographs and X-rays on behalf of the ARRB could find no entry hole anywhere in the rear of the head. (Doug Horne, Inside the ARRB, pgs. 584-586) Additionally, in his fine book, Hear No Evil: Social Constructivism & the Forensic Evidence in the Kennedy Assassination, Dr. Donald Thomas makes the argument that Humes and Boswell had not found a through-and-through entry hole in the skull but had, in fact, found a semi-circular, bevelled notch on the margins of the large defect that they had mistakenly interpreted as a portion of a wound of entrance. Whichever of these arguments about the rear entry wound is correct, the fact remains that the trail of bullet fragments in the top of the head could most likely not have been the result of a bullet entering the rear since the pattern of their dispersal indicates the reverse.

Front to Back

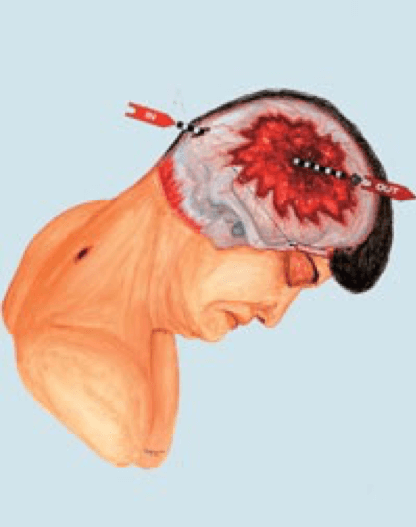

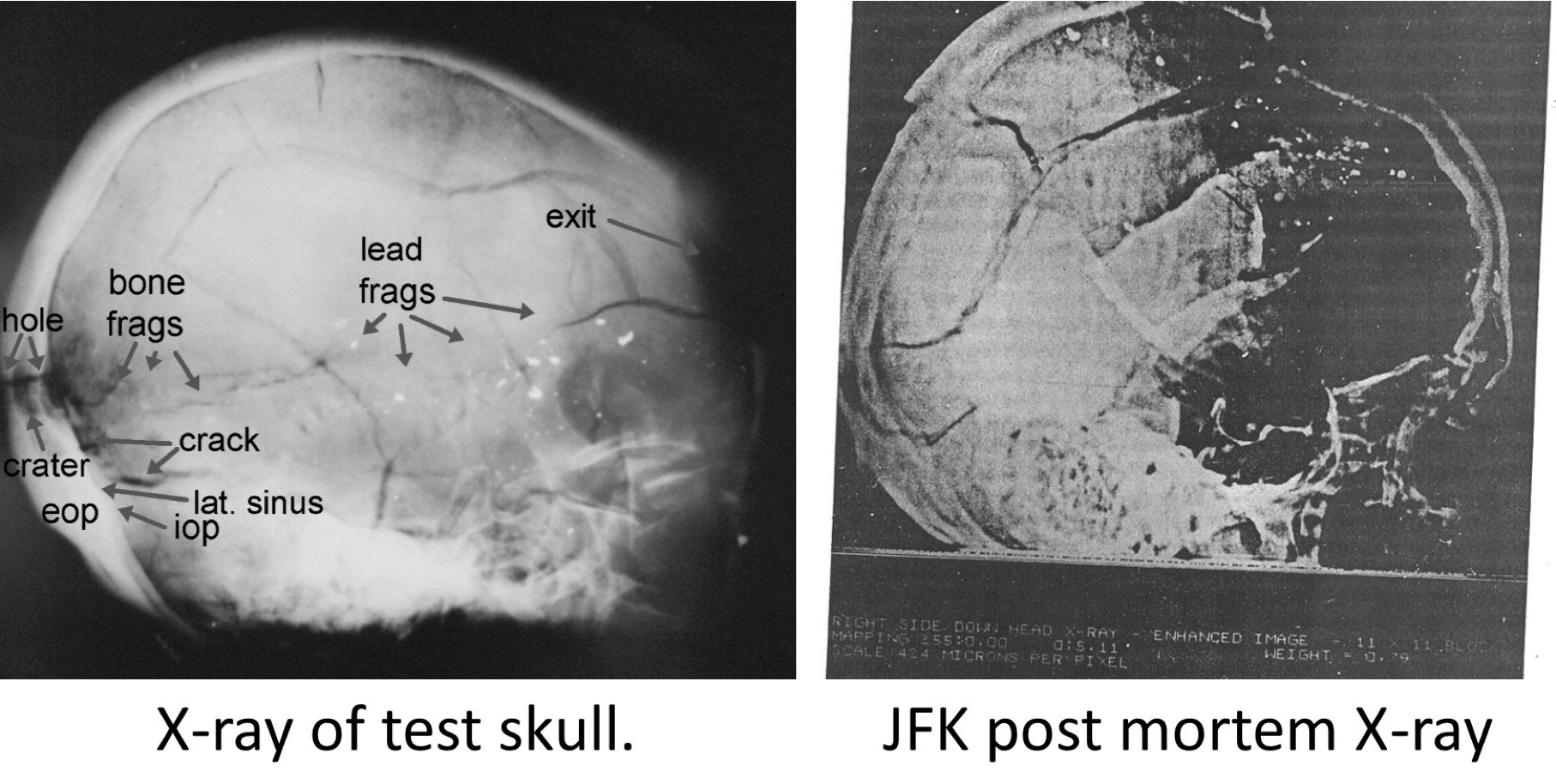

When a bullet disintegrates on striking a skull, the smaller and more dust-like fragments are found closer to the point of entrance whereas the larger particles are found closer to the exit. This is because the larger fragments, having greater mass, have greater momentum and are carried further away from the point of entry. It can be clearly seen in JFK’s post-mortem X-rays that the smallest metallic fragments are located in the right temple area and the largest are found in the top rear of the skull. Therefore, the bullet appears to have been travelling from front to back.

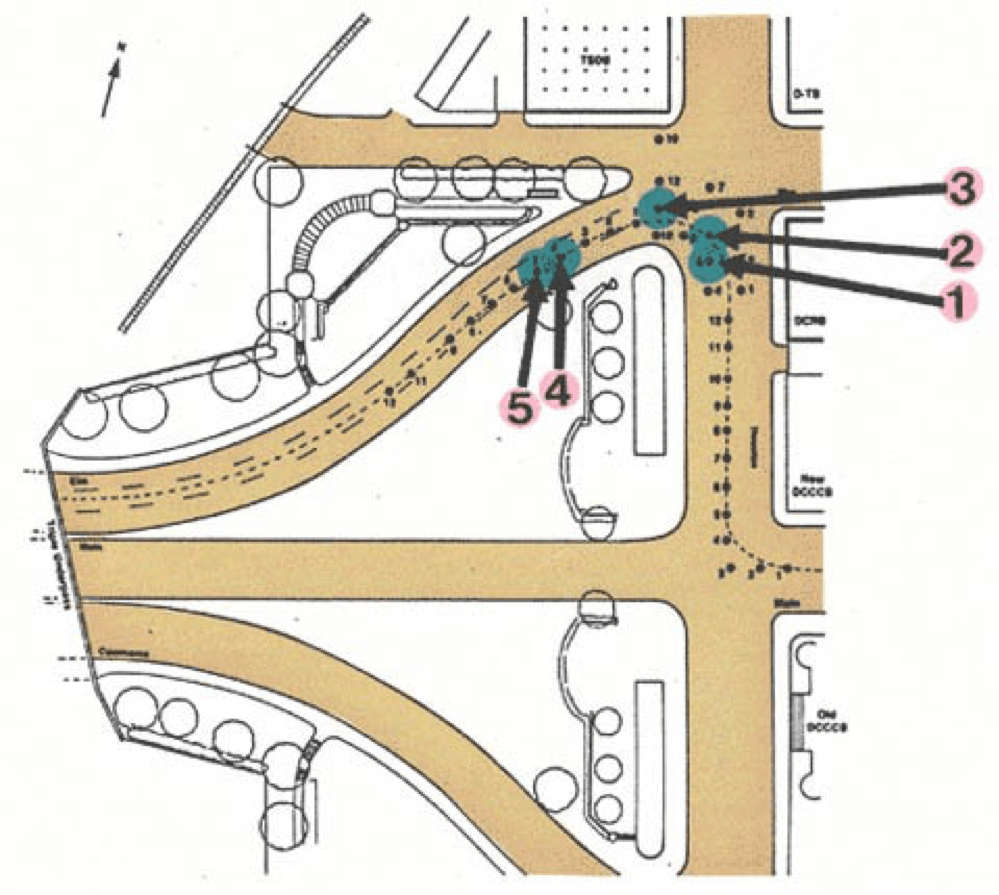

This evidence of a frontal shot not only further validates the acoustics evidence and the witnesses who heard a shot from the grassy knoll, but it also fits well with the President’s reaction as shown on the Zapruder film. Few observers can fail to be struck by the way Kennedy’s head is slammed backwards by the fatal shot. Celebrated American novelist Don DeLillo once commented on the “confusion and horror” that result from viewing this portion of the film, asking, “Are you the willing victim of some enormous lie of the state―a lie, a wish, a dream? Or did the shot simply come from the front, as every cell in your body tells you it did?” (Thompson, Last Second in Dallas, p. 353) Indeed, the film is so persuasive in this regard that its first showing on national television in 1975 led directly to the formation of the House Select Committee on Assassinations.

Alvarez and Sturdivan Hijinks

Warren Commission defenders like Posner, of course, maintain that JFK’s backward motion means nothing. He quotes HSCA forensic pathology panel chairman Dr. Michael Baden as stating that “People have no conception of how real life works with bullet wounds. It’s not like Hollywood, where someone gets shot and falls over backwards. Reactions are different on each shot and on each person.” (p. 315) Posner then offers two theories to explain away the backward motion: the “jet effect” and the “neuromuscular spasm.” Neither of these theories is viable in 2023.

The “jet effect” was the brainchild of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis Alverez who had previously undertaken a “jiggle analysis” of the Zapruder film and suggested that there were three episodes of blurring on the film, demonstrating that the Warren Commission was correct in saying only three shots had been fired. Like Ramsey Clark, Alvarez had been disturbed enough by what he saw in Six Seconds in Dallas that he set out to find a “real explanation” for the backward movement of Kennedy’s head. In the end, what Alvarez offered was the hypothesis that the explosive exiting of blood and brain matter from the right side of JFK’s skull had thrust it in the opposite direction. As Posner tells it, Alvarez established [the jet effect] both through physical experiments that recreated the head shot and extensive laboratory calculations.” (p. 316) The problem, as Josiah Thompson discovered decades later, was that Alvarez had rigged his tests and hidden important aspects of his results.

Seven years after first seeing Thompson’s book, Alvarez reported on an experiment he had conducted by firing rifle bullets into melons, stating that six out of seven of them had moved back towards the shooter as a result of the “jet effect,” thus validating his theory. Yet, as Thompson discovered when he got his hands on the raw data from Alvarez’s shooting tests, Alvarez had failed to disclose the fact that there had been two earlier rounds of shooting which had achieved very different results. During those earlier firings, Alvarez had used larger, heavier melons which apparently did not behave the way he wanted them to. So, in later tests, he reduced their size by half and jacked up the velocity of his bullets to 3000 feet per second. Alvarez had also fired at a variety of other objects besides melons. There were coconuts filled with jello which were blown 39 feet forward; a plastic jug of water which went 6 feet downrange; and 5 rubber balls filled with gelatin; all of which were blown away from the rifle. It was not until he settled on melons that weighed half as much as a human head and increased the velocity of the rifle by more than 1,000 feet per second above that of the Mannlicher Carcano rifle that Alvarez finally achieved the desired effect (see Thompson’s presentation at the Passing the Torch symposium in 2013 on YouTube.) Whilst Alvarez may have succeeded in demonstrating the already established existence of the “jet effect,” he had in no way shown it to be relevant to the motion of President Kennedy’s head.

Larry Sturdivan, who writes that “The jet effect, though real, is not enough to throw the president’s body into the back of the car,” (Sturdivan, p. 164). He advanced instead the other hypothesis that Posner cites: the neuromuscular reaction theory. In a nutshell, Sturdivan postulates that the disruption to Kennedy’s brain “caused a massive amount of nerve stimulation to go down his spine. Every nerve in his body was stimulated…since the back muscles are stronger than the abdominal muscles, that meant that Kennedy arched dramatically backwards.” (NOVA Cold Case: JFK, PBS broadcast in 2013) Yet Sturdivan’s postulate, which he based on what he observed from shooting experiments conducted on anesthetised goats, suffers from an anomalous understanding of human anatomy.

As Dr. Thomas writes, “In any normal person the antagonistic muscles of the limbs are balanced, and regardless of the relative size of the muscles, the musculature is arranged to move the limbs upward, outward, and forward. Backward extension of the limbs is unnatural and awkward; certainly not reflexive. Likewise, the largest muscle in the back, the ‘erector spinae’, functions exactly as its name implies, keeping the spinal column straight and upright. Neither the erector spinae, or any other muscles in the back are capable of causing a backward lunge of the body by their contraction.” (Thomas, p. 341) Additionally, the type of reaction Sturdivan posits is simply not in keeping with what we see on the Zapruder film. President Kennedy’s movement did not begin with the arching of his back. Rather, as the ITEK corporation noted following extensive slow motion study of the Zapruder film, his head snapped backwards first, “then his whole body followed the backward movement.” (ITEK report, p. 64)

In summary, Posner cites two theories dreamed up by two different scientists who do not even agree with one another. One of those was a Nobel Prize-winning physicist who rigged his experiments and cherrypicked his results. The other was a ballistics specialist who confused the reactions of goats with those of human beings and, in so doing, offered a theory that was anatomically impossible―on top of being contradicted by JFK’s actual reaction as seen on the Zapruder film. It can be confidently stated, then, that neither hypothesis truly explains why Kennedy was sent hurtling backwards and leftwards by the bullet that struck his skull. There is one straight forward explanation, however, that does not rely on rigged shooting experiments or misunderstanding of human physiology. Namely, a shot from the grassy knoll.

Posner and the Magic Bullet

The number and direction of bullets striking President Kennedy’s head will likely be debated ad nauseum unless and until some new or definitive evidence emerges. But there is one debate related to the shooting that should have ended decades ago because there really is no serious discussion to be had. Namely, the debate over The Single Bullet Theory―or “Magic Bullet Theory” as it was aptly dubbed by the first-generation critics of the Warren Report. The SBT is a scientific absurdity that was fabricated solely to prop up the Warren Commission’s faulty lone gunman conclusion and was almost entirely debunked within two years of publication of the Commission’s report. The only reason it continues to be defended to this day is because it is, as Cyril Wecht has repeatedly stated, the “sine qua non” of the official story. It is the keystone of the government’s central conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. Commission lawyer Norman Redlich once candidly admitted to author Edward Epstein that “To say that they [President Kennedy and Governor Connally] were hit by separate bullets, is synonymous with saying that there were two assassins.” (Epstein, Inquest, p. 38) Indeed, as critics and researchers have maintained ever since the publication of the Warren Report, without the SBT there could not have been a single gunman whether it was Oswald or anybody else. It is not surprising, therefore, that Posner spends virtually an entire chapter trying to lend the SBT a legitimacy it does not deserve.

The premise of the SBT is that a bullet, dubbed Commission Exhibit (CE) 399, entered the back of JFK’s neck heading downwards and leftwards and exited his throat just below the Adam’s apple, hitting no boney structures along the way. It then went on to strike Governor Connally in the back of his right armpit, sailed along his fifth rib, smashing four inches of it, before exiting his chest below the right nipple. It pulverized the radius of Connally’s right wrist then entered his left thigh just above the knee, depositing a fragment on the femur, before miraculously popping back out to be found in near-pristine condition on an unattended stretcher in Parkland Hospital. The problems with this outlandish hypothesis are myriad and begin at the very start of its imaginary journey.

As noted earlier in this review, neither CE399 nor any other bullet could have entered the back of Kennedy’s neck and ranged downward out of his throatbecause there was no bullet wound anywhere in the posterior neck. The rear entrance wound was in the President’s upper back, at a point that was anatomically lower than the wound in his throat. The HSCA forensic pathology panel made clear that, given the true location of the back wound, the only way a downward trajectory to the throat would have been possible was if JFK had been leaning drastically forward at the instant he was hit, which is something that is not seen in the Zapruder film. The absolute necessity of the forward lean was confirmed in 1998 during experiments conducted in Dealey Plaza using precision test lasers.

Furthermore, when the Discovery Channel attempted to simulate the SBT by shooting at replica human torsos from a crane set at the height of the sixth-floor window, it wound up demonstrating that a bullet striking the upper back of an upright-seated individual and continuing on a downward trajectory of 20 degrees, would―as common-sense dictates―exit not through the throat but through the chest.

And as if this was not enough by itself to invalidate the SBT, the lateral trajectory through the torso is equally destructive. Dr. John Nichols, a pathology professor to whom Posner makes only a single passing reference, conducted extensive tests with Carcano ammunition and human cadavers and concluded in 1973 that a straight-line from the back wound to the alleged exit in the throat had to pass directly through the hard bone of the spine. (The Practitioner, p. 631-632, November, 1973) Dr. Nichols’s work was fully validated in 1998 by radiation oncologist Dr. David Mantik via a cross-sectional CAT scan of a patient with the same upper body dimensions as President Kennedy.

What the above clearly demonstrates is that a straight-line, downward trajectory through President Kennedy’s torso is a virtual impossibility and, therefore, the SBT is rendered null and void before CE399 is even able to complete the first leg of its fictional journey. Nonetheless, for the sake of thoroughness, let us continue to analyse some of the salient points in Posner’s attempted validation of the Warren Commission’s most infamous fabrication.

Posner pinpoints Zapruder frame 224 as the moment “the bullet, with an initial muzzle velocity of more than 2,000 feet per second, passed through [JFK and Connally] almost simultaneously…” (p. 330) As previously noted, he bases this on the apparent flipping up of Connally’s jacket lapel. But what Posner fails to disclose is that the bullet hole in Connally’s jacket was not in the lapel, it was several inches below it.

Therefore, it is very much debatable whether the lapel movement is in any way related to the passage of a bullet. An even bigger problem for Posner, however, is that at frame 224 Kennedy’s hands are already pulling in towards his chest in reaction to being shot. If Kennedy is already reacting to a gunshot at the very moment CE399 is supposed to be exiting Connally’s chest, then frame 224 provides further evidence that they were struck by separate bullets.

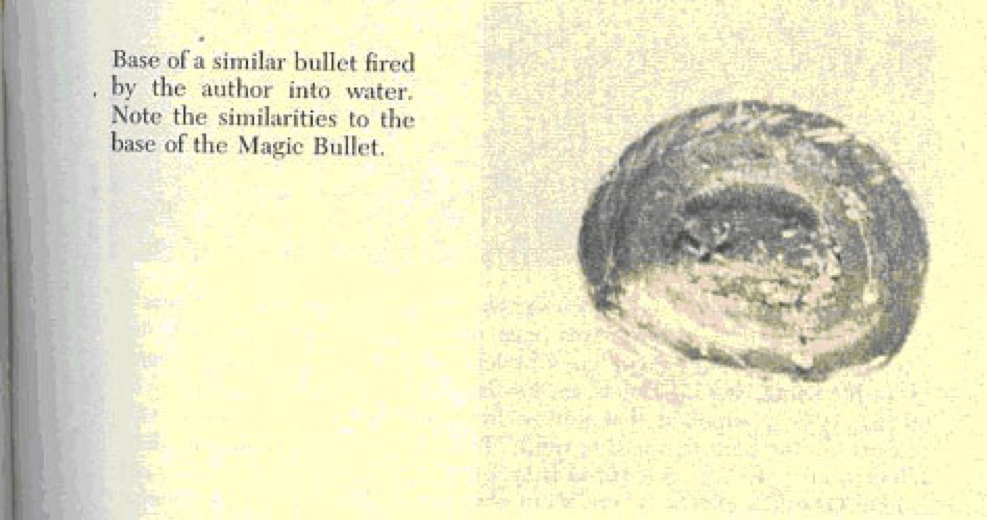

For many critics, the most indigestible facet of the SBT is the remarkable condition of CE399 itself. To the naked eye, the bullet appears in near-pristine condition with almost no deformity besides a very slight flattening of the base. It looks remarkably like bullets the FBI test-fired into tubes of cotton waste and to ones that author Henry Hurt fired into water. In fact, the test bullet pictured in Hurt’s book looks almost exactly like CE399, slightly flattened base-end and all. This raises an obvious question: How is it possible that CE399 could have pierced seven layers of skin and flesh and broken two bones and emerged almost indistinguishable from bullets fired into nothing more than cotton or water?

For the better part of six decades, critics have challenged Commission defenders to produce a single documented example of a bullet that was able to do what they say CE399 did, yet no such bullet has been produced. In a spirited dissent from the HSCA findings, Dr. Cyril Wecht made sure that this fact was entered into the historical record.

For the past 12 or 13 years,” he testified, “I have repeatedly, limited to the context of the forensic pathologist, numerous times implored, beseeched, urged, in writing, orally, privately, collectively, my colleagues; to come up with one bullet, that has done this. I am not talking about 50 percent of the time plus one, 5 percent or 1 percent―just one bullet that has done this…at no time did any of my colleagues ever bring in a bullet from a documented case…and say here is a bullet…there is the crime lab report, it broke two bones in some human being, and look at it, its condition, it is pristine. (1HSCA337)

Dr. Milton Helpern, who was Chief Medical Examiner of New York City for twenty years and conducted more than 10,000 autopsies on gunshot victims, joined Dr Wecht in his skepticism.

I cannot accept the premise that this bullet thrashed around in all that bony tissue and lost only 1.4 to 2.4 grains of its original weight. I cannot believe either that this bullet is going to emerge miraculously unscathed, without any deformity, and with its lands and grooves intact…You must remember that next to bone, the skin offers greater resistance to a bullet in its course through the body than any other kind of tissue…The single bullet theory asks us to believe that this bullet went through seven layers of skin, tough, elastic, resistant skin…this bullet passed through other layers of soft tissue; and then shattered bones! I just can’t believe that this bullet had the force to do what [the Commission] has demanded of it; and I don’t think they have really stopped to think out carefully what they have asked of this bullet. (Robert Groden & Harrison Livingstone, High Treason, p. 66)

CE 399 and John Lattimer’s Trail Of Deception

Posner’s response to this problem is to exaggerate the very slight amount of damage to CE399 by quoting Howard Donahue―creator of the bizarre and ridiculous theory that JFK’s fatal head shot was the result of an accidental discharge by a Secret Service agent―describing the bullet as “somewhat bent and severely flattened.” (p. 335) He goes on to quote John Lattimer as explaining that the reason CE399 appears relatively undamaged is because it tumbled, lost velocity, and struck Connally’s bones side-on. “When it exited the President,” Lattimer says, “it begun tumbling [rotating] and that is evident by the elongated entry wound on the Governor’s back.” (p. 336) In his own book, Kennedy and Lincoln: Medical & Ballistic Comparisons of Their Assassinations, Lattimer writes that “The wound of entry into Connally’s back was 3 cm long (one and one-fourth inches long, the exact length of bullet 399) …” (Lattimer, p. 268) This claim, that the bullet was already tumbling when it struck Connally, is doubly useful for Commission apologists, not only because it can it be used to slow CE399 down but it also suggests that the bullet had been destabilized by striking something else before it hit Connally. Unfortunately for Posner and his lone nut cohorts, the claim is based on Lattimer’s own lie.

The wound in Governor Connally’s back was not 3 cm in length. Rather, as Connally’s thoracic surgeon Dr Robert Shaw explained to the Warren Commission, 3 cm was the length of the wound after it was surgically enlarged. Its original size was only 1.5 cm, half the length Lattimer claimed it was. (WC Vol. 6 p.85)Shaw’s testimony is proven to be accurate by the holes in Governor Connally’s jacket and shirt which measured 1.7 cm and 1.3 cm respectively. (HSCA Vol. 7, pp. 138-41) Of course, at 1.5 cm the wound would still be considered somewhat elongated, but this does not, by itself, constitute evidence that the bullet was tumbling. As Milicent Cranor has pointed out, the wound in the back of Kennedy’s scalp also measured 1.5 cm in length and no one is suggesting that the bulletwhich caused it was tumbling. Rather, as Dr. Shaw explained, the type of elongated or “elliptical” wound seen in the Governor’s back often occurs when the “the bullet enters at a right angle or a tangent. If it enters at a tangent there will be some length to the wound of entrance.” (WC Vol. 6, p.95) One of the Commission’s wound ballistics experts, Dr. Frederick Light, agreed that the bullet “could have produced that wound even though it hadn’t hit the President or any other person or object first.” (WC Vol. 5 p. 95) He explained that the “obliquity” was the result of “the nature of the way the shoulder is built.” (Ibid 97)

Dr. Shaw did not believe the bullet was tumbling as it passed through the Governor’s chest and made special note of “the neat way in which it stripped the rib out without doing much damage to the muscles that lay on either side of it.” (WC. Vol. 4 p.116) Further support for Shaw’s contention comes from the aforementioned experiment the Discovery Channel conducted for its 2004 television special JFK: Beyond the Magic Bullet. The Discovery Channel’s bullet tumbled its way through the “Connally” torso and in so doing it struck two ribs, not one. Furthermore, their test provided additional support for the case against the SBT when their bullet emerged severely bent, looking drastically different to CE399.

When the Warren Commission showed CE399 to its medical experts, none of them believed it could have passed through the radius bone of Connally’s right wrist. The Governor’s wrist surgeon, Dr. Charles F. Gregory, explained in his testimony that the amount of cloth and debris carried into the wrist indicated it had been struck by “an irregular missile.” In his second appearance before the Commission, Dr. Gregory expanded on this point, noting “that dorsal branch of the radial nerve, a sensory nerve in the immediate vicinity was partially transected together with one tendon leading to the thumb, which was totally transected.” This, he said, “is more in keeping with an irregular surface which would tend to catch and tear a structure rather than push it aside.” (WC Vol. 4 p.124) Posner claims that Dr Gregory “agreed that based on examination of the wrist’s entry wound, the bullet had been tumbling and entered backward.” (p. 336) This is a blatant distortion of Gregory’s testimony. When shown the remarkably undeformed CE399 and asked whether it could have produced the wrist wound he had seen and remained so intact, Dr Gregory replied, “The only way that this missile could have produced this wound in my view, was to have entered the wrist backward…That is the only possible explanation I could offer to correlate this missile with this particular wound.” (WC Vol. 4, p.121) However, Dr Gregory clearly did not consider the idea very likely. In fact, later in his testimony he noted that the two mangled bullet fragments found on the floor of the limousine were much more likely the type of missile “that could conceivably have produced the injury which the Governor incurred in the wrist.” (Ibid, p. 128)

At Edgewood Arsenal, the Commission’s experts fired bullets through the wrists of human cadavers and Dr Alfred Olivier later testified to having closely replicated the entrance and exit wounds to Connally’s wrist. When shown an X-ray from one such test Dr Olivier stated that it was “for all purposes identical” to the X-rays of the Governor’s wrist. (WC Vol. 5 p.81) Yet when asked to compare the condition of the test bullet which created the wound to that of CE399 he noted, “It is not like it at all. I mean, Commission Exhibit 399 is not flattened on the end. This one is very severely flattened on the end.” (Ibid 82)

Fackler and Guinn

Posner’s means of getting around all of this is to reference an experiment conducted by wound ballistics specialist Dr. Martin Fackler, who managed to fire a Carcano round through a cadaver’s wrist and have it emerge virtually unscathed by slowing its velocity to 1,100 feet per second. (p. 339) But the relevance of this experiment to the assassination is questionable to say the very least. Firstly, Fackler’s bullet had not already pierced four layers of skin and flesh and smashed a rib as CE399 is alleged to have done. Therefore, the accumulative effect of all this was eliminated from his experiment. And secondly, the average muzzle velocity of the sixth floor Carcano was 2,165 feet per second and its average striking velocity at 60 yards was 1,904 feet per second. (WC Vol. 5 p.77) According to the results of the Commission’s tests, the bullet would have lost a little over 100 feet per second passing through JFK’s back/neck and around 400 feet per second in Connally’s torso. (Ibid 86) All of which means it would have struck the wrist at approximately 1,400 feet per second, a much greater velocity than was utilized in Fackler’s experiment and one at which the bullet would undoubtedly have suffered distortion.

The inexplicable condition of CE399, and the convenience of its alleged discovery on an unattended stretcher at Parkland Hospital, led many early critics to believe it had been planted to complete the frame up of Lee Harvey Oswald. Posner claims, however, that such speculation was ended in 1979 by Dr. Vincent Guinn, a chemist who had performed a sophisticated process known as Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA) on all available bullet fragments and provided “indisputable evidence that [CE399] had travelled through Connally’s body, leaving behind fragments [in the wrist].” (p. 342) Unfortunately for Posner, while the type of comparative bullet lead analysis (CBLA) Guinn conducted was still very much in use when Case Closed was first published in 1993, it has since been abandoned by investigating authorities. In fact, it is widely considered to be “junk science” today.

Guinn’s conclusions rested on his claim, as explained by Posner, that the Western Cartridge Co. bullets made for the Carcano were different from any of the other bullets he had tested during twenty years…the most striking feature, and most useful for identification purposes, was that ‘there seems to be uniformity within a production lot.’” (p. 341) Guinn told the HSCA that the Carcano bullets were virtuallyunique amongst unhardened lead bullets in that they contained varying amounts of antimony. He further suggested that the antimony levels in an individual bullet remained constant but different to the levels found in other bullets from the same box. This, he claimed, meant it was possible to trace a fragment to the individual bullet of origin and distinguish it from all others even if they came from the same box. Thus, he was able to prove that the fragments recovered from Kennedy’s skull and those found on the floor of the limousine all came from one bullet, while the fragments removed from Connally’s wrist came from CE399. Or so he said.

In July 2006, two scientists from the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, metallurgist Erik Randich, Ph.D, and chemist Pat Grant, Ph.D, thoroughly debunked Guinn’s claims in an article published in the Journal of Forensic Science. Randich, and several colleagues who had begun to have grave doubts about CBLA, had already published a serious critique of the process four years earlier, which had led to a review by the National Academy of Sciences and ultimately compelled the FBI to shut down its CBLA lab and order its agents not to testify on the issue in future. Specifically addressing Guinn’s NAA, Randich and Grant showed that Dr Guinn was wrong to suggest that the varying levels of antimony present in Carcano bullets made them unique. They noted that for his comparison tests Guinn had used non-jacketed ammunition which has strictly controlled levels of antimony because the hardness of the round is determined by the amount of antimony mixed into the lead. This, however, is not true of jacketed rifle bullets. As a result, Randich and Grant reported that the assassination bullets and fragments “need not necessarily have originated from MC ammunition. Indeed, the antimony compositions of the evidentiary specimens are consistent with any number of jacketed ammunitions containing unhardened lead.”

Dr. Guinn’s other crucial assertion, that the antimony content of individual Carcano rounds remained constant, was also shown to be erroneous. By presenting highly detailed photomicrographs of Carcano bullets cut in cross-section, Randich and Grant showed how the antimony tends to “microsegregate” around crystals of lead during cooling. This means that a sample taken from one portion of a bullet can have a level of antimony that is entirely different from another sample taken from the same bullet. “The end result of these metallurgical considerations”, Randich and Grant explained, “is that from the antimony concentrations measured by [Guinn] from the specimens in the JFK assassination, there is no justification for concluding that two, and only two, bullets were represented by the evidence…the recovered bullet fragments could be reflective of anywhere between two and five different rounds fired in Dealey Plaza that day.”

It was thanks to Randich and Grant that, as Josiah Thompson puts it, “CBLA was formally thrown into the dust bin of junked theories and bogus methodologies.” (Last Second in Dallas, p. 191) In 2023, then, Vincent Guinn’s NAA can no longer be reasonably used as evidence that CE399 passed through Governor Connally’s wrist or to prove that the first-generation Warren Commission critics were wrong to speculate that the bullet had been planted at Parkland Hospital. That said, fewer critics make the latter argument today because an alternative scenario has since emerged.

CE 399 and the FBI

Although Posner claims that CE399 was found by Parkland Hospital’s senior engineer Darrell Tomlinson when he bumped into Connally’s stretcher, causing the bullet to roll onto the floor, Tomlinson himself was less certain that the stretcher in question was indeed the one that had been used to transport the governor. In his 1967 classic Six Seconds in Dallas, Josiah Thompson made a persuasive case for the bullet Tomlinson found having come from a stretcher that was last occupied by young boy named Ronald Fuller. (Six Seconds in Dallas, pgs. 154-165) But more intriguingly, Thompson noted that when Tomlinson and Parkland Personnel Director O.P. Wright―the man to whom Tomlinson had handed the bullet―were later shown CE399 by the FBI, “both declined to identify it as the bullet they each handled on November 22.” (Ibid, p. 156) Furthermore, the FBI reported that bothSecret Service Agent Richard Johnsen and Secret Service Chief James Rowley, the next two individuals in CE399’s supposed chain of possession, “could not identify this bullet as the one” (WC Vol. 24, p.412)

When Thompson interviewed Tomlinson and Wright, Tomlinson was seemingly unsure of what the bullet he handled had really looked like. Wright was adamant that it had had a pointed tip. Thompson showed him pictures of CE399 and the FBI’s comparison Carcano rounds. But Wright, a law enforcement officer with considerable firearms experience, “rejected all of these as resembling the bullet Tomlinson found on the stretcher.” (Six Seconds in Dallas, p. 175) Thompson did not know what to do with Wright’s recollection at the time and mentioned it only in a footnote where he labelled it “an appalling piece of information” because, if accurate, it suggested that “CE399 must have been switched for the real bullet sometime later in the transmission chain.” (Ibid, p. 176) But three decades later, Gary Aguilar―with Thompson’s help―wound up lending considerable weight to Thompson’s incredulous speculation.

The FBI’s July 7, 1964, report had named Bardwell Odum as the Special Agent who had shown CE399 to Tomlinson and Wright. And so, knowing thatit was standard practice for an FBI Agent to submit a FD-302 reporting his field investigation, Aguilar requested the National Archives search for any reports written by FBI Agent Odum concerning his contacts with Tomlinson and Wright. After a vigorous search, however, he was informed that no such report could be found and that the serial numbers on the FBI documents ran concurrently with no gaps, indicating that no material was missing from the files. Dr Aguilar then decided to seek out Odum himself and in 2002 he tape-recorded the following exchange:

AGUILAR: …From what I could gather from the records after the assassination, you went into Parkland and showed (CE399 to) a couple of employees there.

ODUM: Oh, I never went into Parkland Hospital at all. I don’t know where you got that. … I didn’t show it to anybody at Parkland. I didn’t have any bullet. I don’t know where you got that but it is wrong.

AGUILAR: Oh, so you never took a bullet. You were never given a bullet…

ODUM: You are talking about the bullet they found at Parkland?

AGUILAR: Right.

ODUM: I don’t think I ever saw it even.

Recognizing the significance of Odum’s remarks, Aguilar suggested that perhaps the retired agent had simply forgotten the whole episode. “Answering somewhat stiffly,” Aguilar writes, “he said that he doubted he would have ever forgotten investigating so important a piece of evidence in the Kennedy case. But even if he had forgotten, he said he would certainly have turned in the customary 302 field report covering something that important and he dared us to find it. The files support Odum; as noted above, there are no 302s in what the National Archives states is the complete file on #399.” (Aguilar & Thompson, The Magic Bullet: Even More Magical Than We Knew?)

To summarise the above: Darrell Tomlinson, the person alleged to have discovered CE399 after it rolled off of a stretcher at Parkland Hospital was unable to positively identify it as the one he found. The man to whom he handed the bullet, O.P. Wright, not only denied CE399 was the bullet Tomlinson gave him but insisted that the one he personally handled had had a pointed tip. The next two links in the chain of possession, Secret Service Agent Johnsen and Chief Rowley, could not identify CE399 as the bullet they handled. And another crucial link in the chain, FBI Agent Odum, denied that he had ever even seen the Parkland bullet let alone performed the actions described in the July 7 FBI report and what’s more, the record supports his recollection. If you can believe it, things get even worse for old CE399.

FBI technician RobertFrazier had marked the time he received CE399 on his November 22 laboratory worksheet as “7:30 PM,” and he put the same time on a handwritten note he titled “History of Evidence” which was presumably used as a memory aid during his Commission testimony. And yet, Todd had also made a note of the time he received the stretcher bullet, writing it on the outside of the envelope in which it was held. The time he wrote was “8:50 PM.” This raises a crucial question: how could Frazier receive a bullet from Todd at FBI HQ one hour and 20 minutes before Todd was handed the same bullet at the White House by Chief Rowley? The obvious answer is that he could not. And when we consider this alongside the everything else noted, it leads to the almost inescapable conclusion: that Josiah Thompson’s 1967 speculation was right on the mark.It may well be that the real Parkland bullet was made to disappear and was substituted for one that could be used to pin the blame squarely on the shoulders of Lee Harvey Oswald.

Requiem Mass for Posner

It would be impossible to respond to every false claim, every example of cherry picking, or every instance of deceptive reporting in Posner’s account of the assassination of President Kennedy without writing a book of epic length. What the above hopefully does, however, is get to the core of his case for Oswald as lone gunman and show how and why, despite the accolades he received for his attempt, Posner cannot make an argument in its favor without resorting to the type of trickery of which he accuses the Warren Commission critics.

Putting Oswald in the sniper’s nest requires Posner to ignore his own advice regarding witness testimony and select the latter accounts of witnesses who originally did not recall seeing Oswald on the sixth floor or who claimed to have seen Oswald fire the shots but failed to pick him out of a line-up. It also requires that he ignore the type of mishandling of evidence by the Dallas police that would almost undoubtedly have seen key items excluded from trial had Oswald lived to face his day in court. Most egregious of all, making a case against Oswald compels Posner to invent his own solipsistic record, such as saying that Linnie Mae Randle saw Oswald with a package tucked under his arm that did not quite reach the ground, or that Troy West had been in the depository lunchroom at the time of the assassination and not seen Oswald there as he allegedly claimed to have been. None of this would be necessary if the evidence against the accused assassin was as “overwhelming” as Posner laughably says it is.

But whether one believes Oswald acted as part of the conspiracy or was merely its innocent pawn, there is and always has been overwhelming evidence that the assassination was the work of more than one gunman. And whilst Posner was able to effectively rubbish or hide some of that evidence in 1993, such is simply not possible in 2023. A key tenant of his position, the Neutron Activation Analysis of Vincent Guinn, has been thoroughly discredited, and the very process he used has been abandoned by investigating authorities. Conversely, the acoustical evidence of a gunshot from the grassy knoll that Posner so confidently dismissed has gotten more persuasive over the last two decades, with the major objections to it having been neutered. There is also a much better understanding of what remains of the medical evidence today, with more independent experts having cast their gaze across the materials and made special note of the trail of bullet fragments in JFK’s skull that simply could not have been left behind by a bullet entering the rear of the skull in either of the locations proposed by the Warren Commission and its defenders.

The lynchpin of Posner’s lone gunman scenario, the Single Bullet Theory, was considered absurd by many when first proposed in 1964 and yet somehow still manages to look worse today. Posner makes much of a 3-D computer animation created by Failure Analysis Associates that, he says, not only demonstrated that one bullet could have passed through both President Kennedy and Governor Connally but also, using “reverse projection,” supposedly showed that the shot came from the sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository. (p. 334-335) But real-life experiments that have been performed utilising lasers in the actual environment of Dealey Plaza or involved firing real Carcano bullets through mock torsos have demonstrated otherwise. In fact, together with the CAT scan provided by Dr David Mantik, they have ended the debate once and for all in the minds of all reasonable people.

Gary Aguilar, Josiah Thompson, and John Hunt have hammered the final nail into the coffin for the SBT by demonstrating that CE399―the bullet that was absurdly claimed to have caused all seven non-fatal wounds and then conveniently shown up on a stretcher at Parkland Hospital looking magically unaffected by the bones it broke―has not even a semblance of a chain of evidence. Not only did the first four people who supposedly handled the round fail to recognise it as the one; not only did one of those individuals deny it resembled the bullet he actually handled; but contemporaneous documents place the stretcher bullet in the hands of the Chief of the Secret Service one hour and twenty minutes after the FBI’s Robert Frazier, to whom Chief Rowley handed the missile, had already received CE399! The conclusion that there were two bullets in Washington that day and one of them, the pointed-tip round found by Darrell Tomlinson, was deep-sixed in favour of one that was fired from the sixth-floor rifle is almost impossible to resist or refute. And recall, Posner is a lawyer so he knows all about chain of custody and inadmissible evidence.

Case Closed failed to live up to its title in 1993 because of its author’s blatant and overwhelming bias. Whilst the uninformed academics and journalists who had spent decades looking in the other direction and avoiding criticism of the government’s conclusions may have been taken in by Posner’s artfully constructed prosecution brief, those who had taken the time to study and understand the evidence recognized the book for what it was and recognized Posner for what he is. And Posner did a wonderful job of affirming his incredible bias shortly after the book’s publication when he made apparently ersatz claims before a congressional committee and then stonewalled when asked to provide the proof of his assertions.

Furthermore, thanks to the work of the Assassination Records Review Board―which shed light on numerous issues related to the life and background of Lee Harvey Oswald, the official investigations of the assassination, and the circumstances surrounding the President’s autopsy―and to the diligence and dedication of private researchers such as Gary Aguilar, Josiah Thompson, John Hunt, Russell Kent, Barry Ernest, Donald Thomas, David Mantik, Jim DiEugenio and many others, Case Closed looks even worse today. Oswald has been revealed as a far more complex and interesting individual than Posner gave him credit for being, and the impossibility of the assassination having been the work of a lone individual has been so thoroughly demonstrated that no amount of denialism, no matter how cleverly presented, can prop up the central conclusions of Case Closed in 2023.

was the lower of the two. And as the HSCA forensic pathology panel made clear, this means that a downward trajectory through Kennedy was only possible if he was leaning markedly forward at the instant he was struck, which is something he is not seen to do in the Zapruder film.

was the lower of the two. And as the HSCA forensic pathology panel made clear, this means that a downward trajectory through Kennedy was only possible if he was leaning markedly forward at the instant he was struck, which is something he is not seen to do in the Zapruder film.