Has anyone ever been more conscious, from birth to death, of his coming murder? Malcolm X saw his own violent death in advance just as clearly as his mother Louise Little saw the imminence of his father’s death, on that afternoon in 1931 when her husband Earl left their house and began walking up the road toward East Lansing, Michigan.

“If I take the kind of things in which I believe, then add to that the kind of temperament that I have, plus the one hundred percent dedication I have to whatever I believe in … These ingredients would make it just about impossible for me to die of old age.”

“It was then,” Malcolm says in his autobiography, “that my mother had this vision. She had always been a strange woman in this sense, and had always had a strong intuition of things about to happen. And most of her children are the same way, I think. When something is about to happen, I can feel something, sense something.”1

His mother rushed out on the porch screaming. She ran across the yard into the road shouting, “Early! Early!” Earl turned around. He saw her, waved, and kept on going.

That night Malcolm awakened to the sound of his mother’s screaming again. The police were in the living room. They took his mother to the hospital, where his father had already bled to death. His body had been almost cut in two by a streetcar. Earl Little had been an organizer for Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association, the largest black nationalist movement in American history. Malcolm was told by blacks in Lansing that his father had been attacked by the white racist Black Legion. They put his body on the tracks for a streetcar to run over.

Malcolm believed that four of his father’s six brothers were also killed by white men. Thus the pattern of his own life seemed clear. “It has always been my belief,” he told his co-author Alex Haley, “that I, too, will die by violence. I have done all that I can to be prepared.”2 Malcolm prepared for death by living the truth so deeply that it hastened death. This is the theme of Malcolm X’s autobiography. “To come right down to it,” Malcolm said to Alex Haley, “if I take the kind of things in which I believe, then add to that the kind of temperament that I have, plus the one hundred percent dedication I have to whatever I believe in … These ingredients would make it just about impossible for me to die of old age.”3

As the story neared its end, with Malcolm more and more totally surrounded by forces that wanted him dead, he no longer saw himself as among the living. “Each day I live as if I am already dead … I do not expect to live long enough to read this book in its finished form.”4 And he was right: he died in Harlem on the same day he had originally intended to visit Alex Haley in upstate New York to read the final manuscript.

The assassination of Malcolm X on February 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City was carried out through the collaboration of three circles of power: the Nation of Islam (NOI), the New York Police Department (NYPD), and U.S. intelligence agencies. Malcolm was, as he knew, surrounded at the end by all three of these circles. In terms of their visibility to him and their relationship to one another, the circles were concentric. The Nation of Islam was the nearest ring around Malcolm, the less visible NYPD was next, and the FBI and CIA were in the outermost shadows. The involvement of these three power circles in Malcolm’s murder becomes apparent if we trace his pilgrimage of truth through his interactions with all three of them.

|

| Malcolm X and Alex Haley |

In writing this essay, I have been guided especially by the works of five authors. The first three are Karl Evanzz, Zak Kondo, and Louis Lomax. Washington Post online editor Karl Evanzz is the author of The Judas Factor: The Plot to Kill Malcolm X5 and The Messenger: The Rise and Fall of Elijah Muhammad.6 Evanzz’s two books complement each other brilliantly in presenting a full picture of Malcolm’s assassination, the first emphasizing the U.S. government’s responsibility and the second, that of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. Zak A. Kondo, a professor at Bowie State College, does it all in one book, Conspiracys: Unravelling the Assassination of Malcolm X,7 which follows an unusual (though strangely accurate) title with a complex analysis of the three murderous circles: NOI, NYPD, and U.S. spy agencies. His self-published, out-of-print book that is almost impossible to find has 1266 endnotes, all of which deserve to be read. Then there is Louis Lomax’s To Kill a Black Man,8 first published in 1968, two years before Lomax’s own death in a car accident. As both a faithful friend to Malcolm and a writer wired to what was happening, Lomax already pointed to a solution of Malcolm’s assassination.9 I said I have five guides. The last two are Malcolm X and the man who lived to tell his tale, Alex Haley.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X is the transforming work of both. Haley in his epilogue hints at what Malcolm in his last days realized and was on the verge of shouting—that it was the government, not Elijah Muhammad, and Malcolm’s African connection, not his NOI rejection, that were the primary agent and motivation behind the plot. Malcolm is the ultimate guide to understanding his own murder.

In a memorandum, written four years after Malcolm’s death, the Special Agent in Charge of the FBI’s Chicago office stated that:

Over the years, considerable thought has been given and action taken with Bureau’s approval, relating to methods through which the NOI, could be discredited in the eyes of the general black populace. … Or through which factionalism among the leadership could be created … Factional disputes have been developed—the most notable being MALCOLM X LITTLE.10

|

| Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad |

The FBI developed the factional dispute that led to Malcolm’s death by first placing at least one of its people high within the Chicago headquarters of the Nation of Islam. Its infiltrator then worked to widen a division between Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X. To the FBI’s alarm, this process was inadvertently described, and the FBI man identified, in the 1964 book When The Word Is Given, written by Louis Lomax.

In the paragraph that gave away the FBI’s game, Lomax began by observing that Elijah Muhammad had moved from Chicago to Phoenix, Arizona, for the sake of his health. Lomax then described a significant shift of power. Elijah he said had delegated to his Chicago office not only the NOI’s finances and administration, but also “the responsibility for turning out the movement’s publications and over-all statements,” thus taking away from Malcolm X his critical control over the NOI’s flow of information.

“at one time carried some of these responsibilities, particularly the publishing of the Muslim newspaper..,. And many observers thought they saw an intra-organizational fight when these responsibilities were taken from him and given to Chicago.11

The thing that dismayed the FBI most was the paragraph’s final sentence, which disclosed a hidden factor in this abrupt transfer of power away from Malcolm. The sentence stated that “this decision by Muhammad was made possible because John X, a former FBI agent and perhaps the best administrative brain in the movement, was shifted from New York to Chicago.12

Lomax’s sentence about “John X, a former FBI agent” set off alarm bells in FBI counterintelligence, especially in the office of William C. Sullivan. Assistant FBI Director Sullivan was in charge of the illegal Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) designed to develop a “factional dispute” between Elijah and Malcolm. Sullivan was a high-level commander of covert action. Among his projects was an all-out FBI campaign “aimed at neutralizing [Dr. Martin Luther] King as an effective Negro leader,” as Sullivan put it in a December 1963 memorandum.13

|

COINTELPRO chief

William C. Sullivan |

On March 20, 1964, COINTELPRO chief Sullivan was alerted by an “airtel” from the FBI’s Seattle field office to the objectionable passage in When The Word Is Given.14 The hardcover edition of the book had been published in late 1963, only a few months before what Sullivan must have regarded as a COINTELPRO success story, Malcolm’s March 8, 1964 announcement of his split with Elijah Muhammad. The problem was that to a discerning reader of both the Lomax paragraph and the news of the split, the FBI could be recognized as a key disruptive factor.

|

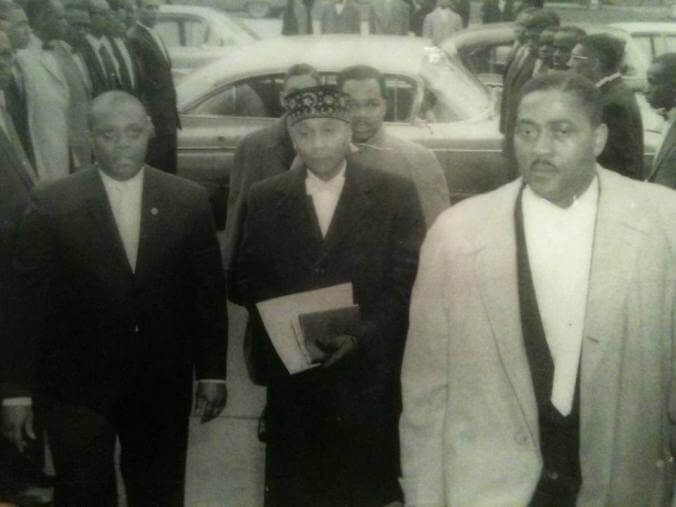

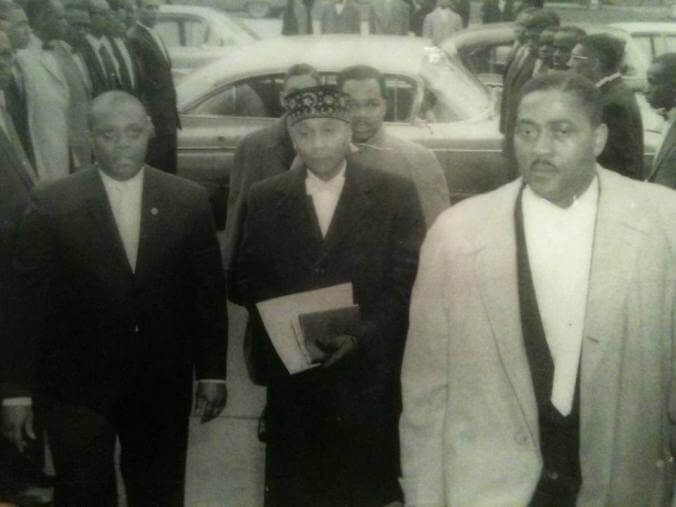

John X Ali Simmons announcing

Malcolm X suspension from

the Nation of Islam |

An FBI official recommended in a memorandum to Sullivan that “the New York Office should be instructed to contact Lomax to advise him concerning the inaccurate statement contained in this book regarding [John X Ali] Simmons. … And that he be instructed to have this statement removed from any future printings of the book.”15 FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover added his personal “OK” to this recornmendation.16 Lomax, however, ignored the FBI’s pressure as well as John Ali’s anger at his having made the statement. He never retracted it. In his later book, To Kill a Black Man, he repeated it, and said that John Ali knew it was true.17 In the six years leading to his death, Lomax never clarified what he meant by the term “former FBI agent.” He may have been giving Ali the benefit of a doubt as to his having severed his FBI connection by the time Lomax mentioned it in 1964. In any case, the FBI had other informants in the Nation of Islam to take his place.

Wallace Muhammad, Elijah Muhammad’s independent-minded son, also believed that FBI informants were manipulating NOI headquarters at the time Malcolm and Elijah became antagonists:

The FBI had key persons in the national staff, at least one or two maybe. They were preparing for the death of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad [in terms of determining his successor]. I believe that the members of the Nation of Islam were influenced to do the things that they were doing not just by the national staff and my father but also by the intelligence department.18

Wallace Muhammad was in a position to know at first hand the FBI’s process of working with NOI informants. The FBI considered him one of them. Karl Evanzz, in researching his biography of Elijah Muhammad entitled The Messenger, discovered from FBI documents that in addition to John Ali, at least three other people were regarded by FBI agents as “reliable sources” close to Muhammad. The first man was Abdul Basit Naeem, a Pakistani journalist who served as an NOI publicist. Then there is Hassan Sharrieff, Elijah Muhammad’s grandson and Wallace Muhammad. Evanzz concludes that the FBI thought “Wallace and Hassan fit the bill because they had provided the Bureau with information it considered crucial to inciting violence between Muhammad’s camp and Malcolm X.”19 Wallace’s and Hassan’s reasons for talking with the FBI seem to have been simply to seek protection from members of their own family, who threatened to kill them for going against Elijah. The FBI then recycled their information for its own use in plotting against Malcolm and Elijah.

“I believe that the members of the Nation of Islam were influenced to do the things that they were doing not just by the national staff and my father but also by the intelligence department.” ~Wallace Muhammad

It was Louis Lomax’s revelation of the FBI’s covert process within the NOI that so concerned the Bureau. Lomax’s statement had given his readers a glimpse into a critical part of the FBI’s COINTELPRO strategy to divide and destroy the Nation of Islam, thereby silencing as well its most powerful voice, Malcolm X.

FBI documents show that the Bureau had been monitoring Malcolm X as far back as 1950, when he was still in prison.20 The Bureau began to focus special attention on Malcolm in the late ’50s, when it realized he had become Elijah Muhammad’s intermediary to foreign revolutionaries. From Malcolm’s Harlem base of operations as the minister of the NOI’s Temple Number Seven, he was meeting regularly at the United Nations with Third World diplomats. In 1957 Malcolm met in Harlem with visiting Indonesian President Achmed Sukarno, whom the CIA had targeted for removal from power. Sukarno was extremely impressed by Malcolm.21 As early as eight years before Malcolm’s death, the FBI and CIA were watching the subversive international connections Malcolm was making.

|

| Abdul Basit Naeem |

In 1957 when Malcolm X was becoming the NOI’s diplomat to Third World leaders, Abdul Basit Naeem was developing into Elijah Muhammad’s public relations man in the same direction.22 Naeem was a Pakistani journalist living at the time in Brooklyn. His first project with Elijah was a 1957 booklet that combined international Islamic affairs with coverage of the Nation of Islam.23 Evanzz discovered that Abdul Basit Naeem became extremely cooperative. Not only was he cooperative with the FBI but also with the New York Police Department’s intelligence unit, “BOSSI” (the acronym for Bureau of Special Service and Investigation).24 BOSSI would later succeed in planting one of its cover operatives in Malcolm’s own security team. The FBI and BOSSI would prove to be linking agencies in the chain of events leading up to Malcolm’s assassination.

At this time Malcolm had also become the apparent successor to Elijah Muhammad, who then loved and respected his greatest disciple more than he did his own sons. Accordingly, the FBI’s Chicago field office, which was monitoring all of Elijah’s communications, told J. Edgar Hoover in January 1958 that Malcolm had become Elijah’s heir apparent.25 Evanzz has described the impact of this revelation on the FBI’s COINTELPRO section:

The secret to disabling the [NOI] movement, therefore, lay in neutralizing Malcolm X.26

Evanzz suggests the FBI began its neutralizing of Malcolm in 1957 by utilizing a police force with which it worked closely on counterintelligence, the New York Police Department.

|

Malcolm in NYC (1957)

“No man should have that much power” |

The NYPD was already in conflict with Malcolm. In April 1957 in Harlem, white policemen brutally beat a Black Muslim, Johnson X Hinton, who had dared question their beating another man. The police arrested the badly injured Hinton and took him to the 28th Precinct Station on 123rd Street. When the station was confronted by a menacing but disciplined crowd, Malcolm X demanded on their behalf that Hinton be hospitalized. The police finally agreed, and were shocked by Malcolm’s dispersal of the 2,600 people with a simple wave of his hand. They concluded with alarm that he had the power to start as well as stop a riot. The city and police also had to pay Hinton $70,000 as a result of an NOI lawsuit.27 A police inspector who witnessed Malcolm’s dispersal of the crowd said, “No man should have that much power.”28

On May 24, 1958, four months after Hoover was told that Malcolm was Elijah’s successor, two NYPD detectives and a federal postal inspector invaded the Queens apartment house in which Malcolm and his wife, Betty Shabazz, lived in one of the three apartments. They shared the house with two other NOI couples, including John X Ali and his wife, Minnie Ali. In 1958, John Ali was not only the secretary of Malcolm’s Mosque Number Seven but also his top advisor, his close friend, and his housemate.29

Brandishing a warrant for a postal fraud suspect who did not live there, the detectives barged into the house and ran directly to Malcolm’s office on the second floor. They fired several shots into it. Fortunately Malcolm was away from the house, but the bullets narrowly missed the terrified women and children in the next room. One detective arrested Betty Shabazz, who was pregnant, and Minnie Ali. He threatened to throw the women down the stairs if they didn’t move faster. The detectives, on the first floor, were confronted and beaten by a crowd of angry neighbors. Police reinforcements arrested six people, including Betty Shabazz and Minnie Ali, who were charged with assaulting the two detectives.30

In response to the attack, an enraged Malcolm X employed a brilliant media strategy against the NYPD that he would develop later against the U.S. government. To expose this case of New York police brutality against blacks, he drew on the support of his new friends at the United Nations. Malcolm wrote an open letter to New York City Mayor Robert Wagner in which he promised to shame the city unless it redressed the grievance:

Outraged Muslims of the African Asian World join us in calling for an immediate investigation by your office into the insane conduct of irresponsible white police officers … Representatives of Afro-Asian nations and their press attachés have been besieging the Muslims for more details of the case.31

|

| Betty Shabazz |

In their March 1959 trial that lasted two weeks, the longest assault trial in the city’s history, Betty Shabazz, Minnie Ali, and the other defendants were all found not guilty by a Queens jury. They filed a $24 million suit that was settled out of court.32

In a first effort to kill or intimidate Malcolm X, the New York Police Department (and perhaps the FBI as instigator) had failed. As in the beating of Hinton, the NYPD was once again discredited by Malcolm. Both the FBI and the city police had come to regard Malcolm increasingly as their enemy. It may also have been through the pressures of this ordeal that the FBI succeeded in establishing its covert relationship with John Ali. At the time Malcolm was unaware of any such development. To Elijah Muhammad he recommended his friend John Ali for the next position he would hold as national secretary in Chicago of the Nation of Islam.

By 1963 conflicts between Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X were becoming obvious. When Louis Lomax had the courage to ask Malcolm about a news report of a minor difference between himself and Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm denied it:

It’s a lie. Any article that says there is a ‘minor’ difference between Mr. Muhammad and me is a lie. How could there be any difference between The Messenger and me? I am his slave, his servant and his son. He is the leader, the only spokesman for the Black Muslims.33

As Malcolm knew, the news report was understated. There were more differences than one between “leader” and “servant,” and they were becoming major. A root conflict was the question of activism. During the creative turmoil of the Civil Rights Movement, more and more black people were heard questioning the Nation of Islam’s inactivity. They would say, “Those Muslims talk tough, but they never do anything, unless somebody bothers Muslims.”34 Malcolm cited this common complaint to Alex Haley, because he agreed with it. He was pushing for the NOI to become more involved. Elijah Muhammad was committed, however, to a non-engagement policy.

While continuing his response to Lomax’s vexing question, Malcolm resorted to NOI theology to admit that there was in fact a difference:

But I will tell you this, the Messenger has seen God. He was with Allah and was given divine patience with the devil. He is willing to wait for Allah to deal with this devil. Well, sir, the rest of us Black Muslims have not seen God, we don’t have this gift of divine patience with the devil. The younger Black Muslims want to see some action.35

A second difference between Malcolm and Elijah arose from Malcolm’s increasing celebrity status. Although Malcolm always prefaced his public statements with “The Honorable Elijah Muhammad says,” it was Malcolm who more often proclaimed the word and gained the greater public attention. Elijah Muhammad coined a tricky formula to reassure Malcolm that this was what he wanted: “Because if you are well known, it will make me better known.”36 But in the same breath, the Messenger warned Malcolm that he would then become hated, “because usually people get jealous of public figures.”37 Malcolm later observed dryly that nothing Mr. Muhammad had ever said to him was more prophetic.38

Malcolm’s rise in prominence as NOI spokesperson, while Elijah Muhammad retreated to Arizona for his health, caused a backlash in Chicago headquarters. When John Ali was appointed to National Secretary, the office was managed by members of Elijah’s family. It was already becoming notorious for its wealth and corruption at the expense of NOI members. In the name of Elijah, John Ali and the Muhammad family hierarchy moved to consolidate their power over Malcolm’s. Herbert Muhammad, Elijah’s son, had become the publisher of the Nation’s newspaper, Muhammad Speaks. He ordered that as little as possible be printed about Malcolm and finally nothing at all.39 With Elijah’s consent from Arizona, Malcolm was being edged out of the picture.

The most serious conflict between the two men occurred when Malcolm became more conscious of rumors concerning his mentor’s affairs with young women. Malcolm conferred with a trusted friend, Wallace Muhammad. Wallace said the rumors were true. Malcolm spoke with three of Elijah Muhammad’s former secretaries. They said Elijah had fathered their children. They also said, as Malcolm related in the autobiography,

Elijah Muhammad had told them I was the best, the greatest minister he ever had, but that someday I would leave him, turn against him—so I was ‘dangerous.’ I learned from these former secretaries of Mr. Muhammad that while he was praising me to my face, he was tearing me apart behind my back.40

|

| Wallace W.D. Muhammad with Malcolm X |

All these developments were being monitored closely by the FBI through its electronic surveillance and undercover informants. The Bureau’s COINTELPRO was also using covert action to destroy Elijah Muhammad in a way it would develop even further against Martin Luther King Jr. On May 22, 1960, Assistant FBI Director Cartha DeLoach approved the sending of a fake letter on Elijah’s infidelities to his wife, Clara Muhammad, and to NOI ministers.41 The rumors Malcolm heard were being spread by the FBI.

On July 31, 1962, COINTELPRO director William C. Sullivan approved another scheme whereby phony letters on Elijah’s philandering would be mailed to Clara Muhammad and “selected individuals.” He cautioned the Chicago Special Agent in Charge: “These letters should be mailed at staggered intervals using care to prevent any possibility of tracing the mailing back to the FBI.”42 While Malcolm X was investigating the secretaries’ charges against Elijah Muhammad, the FBI was trying to deepen his and the Messenger’s differences so as to finalize their split, assuming at the time that their divorce would weaken the power of both men.

“It doesn’t take hate to make a man firm in his convictions. There are many areas to which you wouldn’t give information and it wouldn’t be because of hate. It would be your intelligence and ideals.”

Malcolm struggled to remain loyal to the spiritual leader who had redeemed him from his own depths in prison, but it was only a matter of time before the two men would split over all these issues. The occasion for their break was John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Elijah Muhammad ordered his ministers to refrain from commenting on it. On December 1, 1963, after a speech Malcolm gave in New York City, he was asked his opinion on the President’s murder. He later described his response:

Without a second thought, I said what I honestly felt—that it was, as I saw it, a case of ‘the chickens coming home to roost.’ I said that the hate in white men had not stopped with the killing of defenseless black people, but that hate, allowed to spread unchecked, finally had struck down this country’s Chief of State. I said it was the same thing as had happened with Medgar Evers, with Patrice Lumumba, with Madame Nhu’s husband.43

On the day he saw the headlines on Malcolm’s remark, Elijah Muhammad told his chief minister he would have to silence him for the next 90 days to disassociate the Nation from his blunder. Malcolm said he would submit completely to the discipline. The FBI saw this period as its golden opportunity.

Two FBI agents visited Malcolm on February 4, 1964.44 Malcolm knew they were coming. He had a tape recorder hidden under the sofa in his living room, and recorded the conversation.

The agents admitted that the FBI had chosen that particular time to contact Malcolm because of his suspension by Elijah Muhammad. They hoped that bitterness on Malcolm’s part might move him to become an informant. Such bitterness was understandable, they said sympathetically. The agents even handed Malcolm a facile rationalization for cooperating in their undercover crime of undermining Elijah, while compromising him:

It would not be illogical for someone to have spent so many years doing something, then being suspended.45

Malcolm: No, it should make one stronger. It should make him realize that law applies to the law enforcer as well as those who are under the enforcement of the enforcer.46

After failing to get anywhere with Malcolm, one of the agents said, “You have the privilege [of not giving the FBI information]. That is very good. You are not alone. We talk to people every day who hate the Government or hate the FBI.” Then he added, with a stab at bribing Malcolm, “That is why they pay money, you know.”47

Malcolm ignored the bribe and went to the heart of the question: “That is not hate, it is incorrect to clarify that as hate. It doesn’t take hate to make a man firm in his convictions. There are many areas to which you wouldn’t give information and it wouldn’t be because of hate. It would be your intelligence and ideals.”48

Malcolm had learned that he was forbidden by Elijah Muhammad even to teach in his own Mosque Number Seven, and that the Nation had announced further that he would be reinstated “if he submits.” The impression was being given that he had rebelled.

Looking back at the announcement, he said to Haley, “I hadn’t hustled in the streets for nothing. I knew when I was being set up.”49 Malcolm realized the ground was being laid by NOI headquarters to keep him suspended indefinitely. A deeper realization came when one of his Mosque Seven officials began telling the men in the mosque that if they knew what Malcolm had done, they’d kill him themselves. “As any official in the Nation of Islam would instantly have known, any death-talk for me could have been approved of, if not actually initiated, by only one man.”50 Malcolm knew that Elijah Muhammad, the spiritual father whom he had revered and served for 12 years, had now sanctioned his murder.

|

Captain Joseph X Gravitts

(to the left of Elijah Muhammad) |

Then came a first death plot. One of Malcolm’s own Mosque Seven officials, Captain Joseph X Gravitts, following higher orders, told an assistant to Malcolm to wire his car to explode when he started the engine. The man refused the assignment, told Malcolm of the plot, and saved his life.51 He also freed Malcolm from his attachment to the Nation of Islam. Malcolm was forced to recognize that the NOI’s hierarchy and structure, extending right down into his own mosque, was committed to killing him. He could already see a first ring of death encircling him, comprised of the organization he had developed to serve Elijah Muhammad. From that point on, Malcolm said, he “went few places without constant awareness that any number of my former brothers felt they would make heroes of themselves in the Nation of Islam if they killed me.”52

On March 8, 1964, with less than a year to live, Malcolm X announced his departure from the Nation of Islam. He said he was organizing a new movement because the NOI had “gone as far as it can.” He was “prepared to cooperate in local civil-rights actions in the South and elsewhere. “53 Malcolm also passed out copies of a telegram he had sent to Elijah Muhammad, in which he stated:

Despite what has been said by the press, I have never spoken one word of criticism to them about your family … 54

In spite of everything, Malcolm was trying not to split the NOI, and therefore muffled his criticisms of Elijah Muhammad.

Two days later, the Nation of Islam sent Malcolm a certified letter telling him and his family to move out of their seven-room house in East Elmhurst, Queens. The Elmhurst house had been home for Malcolm, Betty Shabazz, and their growing family (now with four daughters) since the early days of their marriage when Malcolm and Betty were in the house with John and Minnie Ali. One month after the certified letter, the secretary of Malcolm’s old Mosque Number Seven filed suit in a Queens civil court to have Malcolm and his family evicted. Malcolm would fight for the legal right to stay in the only home he had to pass on to his wife and children, especially since he might soon be killed by the same forces trying to take their house away.55

On March 12, Malcolm held a press conference in New York and said internal differences within the Nation had forced him out of it. He was now founding a new mosque in New York City, Muslim Mosque, Inc. With a conscious effort to avoid repeating the mistakes of Elijah Muhammad, he said in his “Declaration of Independence” that he was a firm believer in Islam but had no special credentials:

I do not pretend to be a divine man, but I do believe in divine guidance, divine power, and in the fulfillment of divine prophecy. I am not educated, nor am I an expert in any particular field—but I am sincere, and my sincerity is my credentials.56

He opened (wide) the door to working with other black leaders, with whom he had traded criticisms, most notably with Martin Luther King Jr. “As of this minute, I’ve forgotten everything bad that the other leaders have said about me, and I pray they can also forget the many bad things I’ve said about them.”57 He then immediately chased King away by saying black people should begin to form rifle clubs to defend their lives and property.

He concluded:

We should be peaceful, law-abiding—but the time has come for the American Negro to fight back in self-defense whenever and wherever he is being unjustly and unlawfully attacked. If the government thinks I am wrong for saying this, then let the government start doing its job.58

Malcolm was aware that the government might think it was its job to silence him.

Much more threatening to the government than Malcolm’s rifle clubs, which never got off the ground, was the visionary campaign he then initiated to bring U.S. violations of African-Americans’ rights before the court of world opinion in the United Nations. In his April 3, 1964, speech in Cleveland, “The Ballot or the Bullet,” Malcolm began to articulate his international vision:

We need to expand the civil-rights struggle to a higher level—to the level of human rights. Whenever you are in a civil-rights struggle, whether you know it or not, you are confining yourself to the jurisdiction of Uncle Sam … Civil rights comes within the domestic affairs of this country. All of our African brothers and our Asian brothers and our Latin-American brothers cannot open their mouths and interfere in the domestic affairs of the United States. … But the United Nations has what’s known as the charter of human rights, it has a committee that deals in human rights … When you expand the civil-rights struggle to the level of human rights, you can then take the case of the black man in this country before the nations in the UN. You can take it before the General Assembly. You can take Uncle Sam before a world court. But the only level you can do it on is the level of human rights.59

In the spring of 1964, Malcolm X had come up with a strategy to internationalize the Civil Rights Movement by re-defining it as a Human Rights Movement, then enlisting the support of African states. Malcolm would proclaim to the day of his death the nation-transcending word of human rights, not civil rights, for all African-Americans. He would also organize a series of African leaders to work together and make that word flesh in the General Assembly of the United Nations. In breaking his bonds to Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm had freed himself to unite African and African-American perspectives in an international coalition for change. For the rest of his life, he was on fire with energy to create that working partnership spanning two continents.

In breaking his bonds to Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm had freed himself to unite African and African-American perspectives in an international coalition for change.

The FBI began to realize it had made a major miscalculation. Its COINTELPRO that helped precipitate the divorce between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad had, it turned out, liberated Malcolm for a much larger mission than anything he could conceivably have accomplished under Elijah Muhammad. He was suddenly stepping onto an international stage in what could become an unwelcome scenario to the U.S. government. Nevertheless, the Chicago NOI connections that the Bureau had made so carefully in John Ali and other informants could still salvage the COINTELPRO goal of neutralizing Malcolm. Since Malcolm had “rebelled” against Elijah and Chicago, he could now, with Chicago’s help, be forced into silence forever.

The FBI had a second, growing concern. Despite Malcolm’s offputting talk of rifle clubs, his evolving strategy for an international ballot, not the bullet, was catching the attention of a potential ally whose power went far beyond that of Elijah Muhammad: Martin Luther King Jr.

Malcolm and Martin met for the first and only time in the nation’s capital on March 26, 1964. They had both been listening to the Senate’s debate on civil rights legislation. Afterwards they shook hands warmly, spoke together, and were interviewed. He grinned and said he was there to remind the white man of the alternative to Dr. King. King offered a militant alternative of his own, saying that if the Senate kept on talking and doing nothing, a “creative direct action program” would start. If the Civil Rights Act were not passed, he warned, “our nation is in for a dark night of social disruption.”60

|

| Malcolm and Martin (March 26, 1964) |

Although Malcolm and Martin would continue to differ sharply on nonviolence and would never even see each other again in the 11 months Malcolm had left, there was clearly an engaging harmony between the two leaders standing side by side on the Capitol steps. Given Malcolm’s escalation of civil rights to human rights and King’s emphasis upon ever more disruptive, massive civil disobedience, their prophetic visions were becoming more compatible, even complementary. The FBI and CIA, studying the words and pictures of that D.C. encounter in their midst, could hardly have failed to recognize a threat to the status quo. If Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. were to join efforts, they could ignite an explosive force for change in the American system. The FBI and CIA had to face a question paralleling that of the New York police who had witnessed Malcolm’s crowd dispersal. Should any two men have that kind of power against the system?

On the same day Malcolm and Martin shook hands in Washington, the FBI’s NOI connections were proving to be an effective part of an action in Chicago to further isolate Malcolm, setting him up for his murder.

Philbert X Little, Malcolm’s brother, was Elijah Muhammad’s minister in Lansing, Michigan. The Messenger and his NOI managers ordered Philbert to report to Chicago, where they arranged a press conference for him on March 26 of 1964. John Ali then handed Philbert a prepared statement. Ali told Philbert to read it to the media. Philbert had never seen the text before. As he read it for the first time (aloud and in a monotone) he heard himself denouncing Malcolm in terms that threatened Malcolm’s converts from the Nation of Islam.

I see where the reckless efforts of my brother Malcolm will cause many of our unsuspecting people, who listen and follow him, unnecessary loss of blood and life.61 … the great mental illness which beset my mother whom I love and one of my brothers … may now have taken another victim … my brother Malcolm.62

Malcolm responded to the news of his brother’s apparent attack on him by saying,

We’ve been good friends all our lives. He has a job he needs; that’s why he said what he did … I know for a fact that they flew him in from Lansing, put a script in his hand and told him to read it.63

Philbert himself confirmed years later that “the purpose of making that statement was to fortify the Muslims. That’s why I was brought to Chicago. When I got ready to make my statement, John Ali put a paper in front of me and told me I should read that. So I read the statement that was very negative for my mother. And it was negative against Malcolm. I wouldn’t have read it over the air, you see, if I had looked at it. I asked John Ali about it and he says, ‘That’s just a statement that was prepared for you to read.’ He said, ‘I know the Messenger will be very pleased with the way you read it,’ and that was it.”64

The vision to which Malcolm X was converted by his experience at Mecca determined the way in which he would meet his death. He called that vision ‘brotherhood’.

Elijah Muhammad’s vengeance toward Malcolm was still being fueled by the FBI’s COINTELPRO. At the time of “Philbert’s statement,” the FBI sent Elijah one of its fake letters complaining about his relationships with his secretaries. The letter succeeded in making Elijah suspect Malcolm had written it. On April 4, 1964 an FBI electronic bug recorded Elijah telling one of his ministers, who had also received a copy of the letter, that the presumed writer Malcolm “is like Judas at the Last Supper.”65

In recognition that his 12 years proclaiming the word of Elijah Muhammad had left him poorly prepared for his new mosque’s ministry, Malcolm decided to re-discover Islam by making his pilgrimage to Mecca.

|

| Malcolm at Mecca (1964) |

In a life of changes, Malcolm’s most fundamental change began at Mecca. At the conclusion of his pilgrimage, he was asked by other Muslims what it was about the Hajj that had most impressed him. He surprised them by saying nothing of the holy sites or the rituals but extolling instead the multi-racial community he had experienced.

“The brotherhood!” he said, “The people of all races, colors, from all over the world coming together as one! It has proved to me the power of the One God.”66

The vision to which Malcolm X was converted by his experience at Mecca determined the way in which he would meet his death. He called that vision “brotherhood.” Had he lived a while longer, he would have added “and sisterhood.” In his final months, Malcolm also began to change noticeably in his recognition of women’s rights and leadership roles. His conversion at Mecca was to a vision of human unity under one God. From that point on, his consciousness of one human family, in the sight of one God, sharpened his perceptions, deepened his courage, and opened his soul to whatever further changes Allah had in store for him. Consistent with all those changes, Malcolm’s experience of the truth of brotherhood radicalized still more his resistance to racism. His conversion to human unity was not to a phony blindness to the reality of prejudice, but on the contrary, to a greater understanding of its evil in God’s presence. He was even more determined to confront it truthfully. Concluding his answer to his fellow pilgrims on his Hajj, Malcolm returned to his lifelong focus on racism, set now in the context of the experience he had at Mecca of his total acceptance by pilgrims of all colors.

“To me,” he said, “the earth’s most explosive and pernicious evil is racism, the inability of God’s creatures to live as One, especially in the Western world.” 67

|

| Malcolm & Kwame Nkrumah; with Prince Faisal |

Following his pilgrimage to Mecca, Malcolm met with two influential heads of state, Prince Faisal of Arabia and President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. They acknowledged Malcolm as a respected leader of black Americans, who now represented also a true Islam. Prince Faisal of oil-rich Arabia made Malcolm a guest of the state. Ghana’s anti-colonialist Kwame Nkrumah, a leader of newly independent African states, told his African-American visitor something Malcolm said he would never forget:

Brother, it is now or never the hour of the knife, the break with the past, the major operation.68

Nkrumah’s sense of the hour of the knife was right, but his hope that it would be a knife of freedom cutting through a history of oppression would go unfulfilled. Only nine months later, Malcolm would be murdered.

A year after that, Nkrumah, upon publishing his book Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, dedicated to “the Freedom Fighters of Africa, living and dead,” would be overthrown by a CIA-backed coup.69

“The case to be presented to the world organization … would compel the United States Government to face the same charges as South Africa and Rhodesia.”

Malcolm also visited Egypt, Lebanon, Nigeria, Liberia, Senegal, Morocco, and Algeria. Upon his return to the U.S. on May 21, 1964, the New York Times published an article on his trip that further alerted intelligence agencies to Malcolm’s quest for a UN case against the U.S. Malcolm told reporters he had “received pledges of support from some new African nations for charges of discrimination against the United States in the United Nations.”

“The case to be presented to the world organization,” he asserted, “would compel the United States Government to face the same charges as South Africa and Rhodesia.”70

While Malcolm was working abroad to put the U.S. on trial at the UN, the New York Police Department was infiltrating his new Muslim Mosque with its elite intelligence unit, the Bureau of Special Service and Investigation (BOSSI). To the cold warriors in the ’60s who knew enough beneath the surface to know at all about BOSSI, the NYPD’s undercover force was regarded as “the little FBI and the little CIA.” The accolade reflected the fact that the information gathered by BOSSI’s spies was passed on regularly to federal intelligence agencies.71

|

BOSSI operative

Tony Ulasewicz |

The BOSSI men who ran the deep cover operation in Muslim Mosque were detectives Tony Ulasewicz and Teddy Theologes. Four years after Tony Ulasewicz’s undercover work on Malcolm X, “Tony U,” as he was known, would retire from the NYPD to go to work as President Richard Nixon’s private detective. He would then take part in a series of covert activities that would be brought to light in the Senate Watergate Hearings and memorialized in his own book, The President’s Private Eye,72 which is also a valuable resource on BOSSI. Both in his book and his life, Tony U moves with ease between the overlapping undercover worlds of the New York Police Department, federal intelligence agencies, and the White House. In the BOSSI chain of command, Tony U was a field commander. He had to keep his operators’ identities totally secret as he ran their surveillance and probes of various sixties organizations ranging from the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) to the American Nazi Party. Equally important, he had to keep his own behind-the-scenes identity completely separate from theirs, with his name never linked to the report of any agent of his. Otherwise he might be called to testify in court, opening up an operation, an event to be avoided at all costs.73 Tony U’s deep cover men were therefore, in the last analysis, on their own.

Teddy Theologes acted in the BOSSI command, in Tony U’s words, “as a cross between a drill sergeant and a priest.”74 Reflecting on his career decades later in an interview, Theologes said some of the BOSSI deep cover recruits “needed constant attention. I would have to sit down with them, and almost be a father, brother, psychiatrist, and doctor.75 From the standpoint of agents risking their lives who knew their superiors would never admit to knowing them, the need for such a relationship can be understood.

|

| Gene Roberts |

On April 17, 1964, four days after Malcolm left New York on his pilgrimage to Mecca, Ulasewicz and Theologes sent their newly sworn-in, 25-year-old, black detective Gene Roberts on his undercover journey into the Muslim Mosque, Inc. Gene Roberts had just completed four years in the Navy. Roberts was interviewed by Tony Ulasewicz and Teddy Theologes when he passed the police exam. He was asked to become a deep cover agent in a militant organization under Malcolm X. Roberts had heard of Malcolm X but knew little about him. As a military man, he accepted the order to infiltrate Malcolm’s group without questioning it. On April 17, he was sworn in as a police officer and given his badge. A few hours later, Teddy Theologes took the badge away from him. He was on his own. Then his BOSSI superiors sent Roberts out on his mission in Harlem.76

Gene Roberts has described how he proceeded step by step into becoming one of Malcolm’s bodyguards:

Basically they said, go up to 125th Street—where Malcolm had his headquarters—and get involved. And that’s what I did. I ended up getting involved in a couple of riots. The main thing was I was there. I met members of his organization. They accepted me. My cover was I worked for a bank. I told them about my martial arts experience, so I became one of Malcolm’s security people. When he came back from Mecca and Africa, I went wherever he went, as long as it was in the city.77

Since he was supposedly a bank worker, Roberts followed a schedule of typing up his BOSSI reports, at his Bronx home during the day. He typed reports on what he had learned by being “Brother Gene” with Malcolm and his community during the night.78 As Roberts suspected and would later confirm, he was not the only BOSSI agent in the group, although he had gained the greatest access to Malcolm. When Ulasewicz and Theologes received his and other deep cover dispatches, they passed them up the line to BOSSI Supervisor Barney Mulligan. It was Lieutenant Mulligan’s responsibility to file all the undercover information (without ever identifying the informants) at BOSSI headquarters. While there, BOSSI’s secret fruit was shared generously with the FBI.

On May 23, 1964, Louis Lomax and Malcolm X took part in a friendly debate at the Chicago Civic Opera House. As Lomax began his opening speech and looked down from the stage, he was struck with fear. For there in the audience staring back up at him was John Ali, accompanied by a group of NOI men who were being deployed at strategic locations in the hall.79 Ali had become the nemesis of Lomax as well as Malcolm because of Lomax’s having written about Ali’s FBI connection. Malcolm’s, Ali’s, and Lomax’s lives were intertwined. When John Ali was Malcolm’s top advisor and housemate, he had arranged the first meeting between Malcolm and Lomax. The three men had then worked together on the first issues of the NOI newspaper. When Malcolm’s and Ali’s home was invaded by the New York police, Louis Lomax had written the most thorough story on it.80

In his Chicago speech, given only two days after his return from Mecca and Africa, Malcolm sounded open to white people as well as blacks, as impassioned as ever, and in the terms he used, even radically patriotic:

My pilgrimage to Mecca … served to convince me that perhaps American whites can be cured of the rampant racism which is consuming them and about to destroy this country. In the future, I intend to be careful not to sentence anyone who has not been proven guilty.

I am not a racist and do not subscribe to any of the tenets of racism. In all honesty and sincerity it can be stated that I wish nothing but freedom, justice and equality: life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness—for all people. My first concern is with the group of people to which I belong, the Afro-Americans, for we, more than any other people, are deprived of these inalienable rights.81

However, in his post-Mecca life, this radically open Malcolm X was once again a target, as he and Lomax could see when they looked down into the eyes of John Ali and his companions. At the debate’s conclusion, Malcolm and Lomax departed from the rear of the hall under a heavy Chicago police escort.82 It was one in a series of occasions when Malcolm would gladly accept the protection of a local police department that was genuinely concerned about his safety.

Also near the end of May 1964, the five men who would kill Malcolm X in the Audubon Ballroom nine months later came together for the first time. We know the story, thanks to the confession of the only one of the five who would ever go to jail for the crime, Talmadge Hayer. According to Hayer’s affidavit, sworn to in prison in 1978 to exonerate two wrongly convicted co-defendants,83 it all began when he was walking down the street one day in Paterson, New Jersey. A car pulled up beside him. Inside it were two men who, like Hayer, belonged to the Nation of Islam’s Mosque Number 25 in Newark—Benjamin Thomas and Leon Davis, known to Hayer as Brothers Ben and Lee. They asked Hayer to get in the car so they could talk. “Both of these men,” he said, “knew that I had a great love, respect, and admiration for the Honorable Elijah Muhammad.”84

While the three men drove around Paterson, Hayer learned from Thomas and Davis that “word was out that Malcolm X should be killed.” Hayer said in his confession he didn’t know who had passed that word on, but he thought Ben knew. He in fact had good grounds for thinking Ben knew, inasmuch as Benjamin Thomas was the assistant secretary of the Newark Mosque and knew well the NOI chain of command. Hayer also said it was Ben who had spoken first to Leon, before the two of them spoke with him. After hearing from them how Malcolm X was spewing blasphemies against Mr. Muhammad, he said what they wanted to hear, “It’s just bad, man, something’s got to be done,”85 and agreed to take part in the plot.

As Hayer told Malcolm biographer Peter Goldman in a prison interview,

I didn’t ask a whole lot of questions as to who’s giving us instructions and who’s telling us what, because it just wasn’t a thing like that, man. I thought that somebody was giving instructions: ‘Brothers, you got to move on this situation.’ But I felt we was in accord. We just knew what had to be done.86

Thomas, Davis, and Hayer soon got together with two more members of the Newark Mosque who also knew what had to be done, William X and Wilbur X. As male members of the Nation of Islam, all five men belonged to the Fruit of Islam (FOI), a paramilitary training unit.87 FOI training was meant ideally for self-defense. However, with its combination of discipline, obedience, and unquestioning loyalty to the Messenger, it had degenerated into an enforcement agency for the will of Elijah Muhammad and the NOI hierarchy. Malcolm X, with his certain knowledge that FOI teams like the five men in Newark were being organized to kill him, said sharply in a June 26, 1964, telegram to Elijah Muhammad:

Students of the Black Muslim Movement, know that no member of the Fruit of Islam will ever initiate an act of violence unless the order is first given by you. … No matter how much you stay in the background and stir others up to do your murderous dirty work, any bloodshed committed by Muslim against Muslim will compel the writers of history to declare you guilty not only of adultery and deceit, but also of Murder.88

In his affidavit, Talmadge Hayer said the five men from the Newark Mosque began meeting to decide how to carry out the killing. Sometimes, he said, they would just drive around in a car for hours talking about it.89 Since Malcolm was on the verge of making another even longer trip to Africa, they would have to bide their time. In the meantime, there were other killing teams who were united in the same purpose. Several would almost succeed. But in the end, it would be the five Newark plotters who would finally do what had to be done at the Audubon Ballroom.

It is a temptation to sentimentalize Malcolm, but Malcolm did not sentimentalize himself. He knew what he was capable of doing, what he had done, and what he had trained the Fruit of Islam to do. They were now prepared to do it, as he knew, to him.

On June 13, 1964, the NOI’s suit to force Malcolm and his family out of the East Elmhurst house began to be heard in Queens Civil Court. The courtroom was divided into two hostile camps, Malcolm’s supporters and the NOI contingent. At this point the police department clearly acknowledged in action the immediate danger to Malcolm’s life. It had 32 uniformed and plainclothes officers present, “surrounding him so impermeably,” as reporter Peter Goldman put it, “that he could barely be seen from the gallery.”90 Some of the press remained skeptical of the threat to Malcolm. He insisted to reporters that he knew the NOI men were capable of murder “because I taught them.”91

This statement that Malcolm repeated about his NOI past was apparently no exaggeration. Dr. Alauddin Shabazz, who was ordained by Malcolm as an NOI minister, told me in an interview: “Malcolm had had people killed. When Malcolm found a guy in the nation who was an agent, Malcolm didn’t hesitate to do something to him. I have seen Malcolm take a hammer and knock out the bottom bridges of a guy’s teeth.

[An undercover police agent] was once caught setting up an [electronic] bug in the wall of the office. Malcolm was questioning him. And Malcolm had a funny way of questioning people. He would stand with his back to you, like he didn’t want to look at your disgusting face—if he thought you were doing something to aid BOSSI or the agencies. And this guy had been caught. Malcolm turned around. He had a hammer on the desk. He turned around with the hammer and hit him in the face. I was there. It was in the early ’60s.92

It is a temptation to sentimentalize Malcolm, but Malcolm did not sentimentalize himself. He knew what he was capable of doing, what he had done, and what he had trained the Fruit of Islam to do. They were now prepared to do it, as he knew, to him.

The Queens eviction hearing was especially significant for what Malcolm chose to reveal during his June 16 testimony: “[T]hat the Honorable Elijah Muhammad had taken on nine wives.”93 At about the same time as Malcolm made the issue public, one of Elijah Muhammad’s sons made a statement that was in effect a warrant for Malcolm’s death. It was prompted by a phone call from someone claiming to be “Malcolm.” This person told the NOI that Elijah Muhammad would be killed while giving his speech the following day.94 In response to this provocation (in conflict with the real Malcolm’s pleas to his followers to avoid a confrontation), Elijah Muhammad Jr. told a meeting of the Fruit of Islam at a New York armory:

That house is ours, and the nigger don’t want to give it up. Well, all you have to do is go out there and clap on the walls until the walls come tumbling down, and then cut the nigger’s tongue out and put it in an envelope and send it to me, and I’ll stamp it approved and give it to the Messenger.95

The judge would rule three months later that the house belonged to the Nation of Islam, and that Malcolm and his family had to leave. Malcolm appealed, which delayed the eviction until the final week of his life.

On June 27, 1964, the FBI wiretapped a phone call in which Malcolm X asked an unidentified woman (an office worker … Betty Shabazz?) if Martin Luther King’s attorney Clarence Jones had called him.96 The woman said, yes, she had a message from Jones asking Malcolm to call him back. The reason Jones wanted to speak with Malcolm, she said, was “that Rev. King would like to meet as soon as possible on the idea of getting a human rights declaration.” She then emphasized to Malcolm, “He is quite interested.”97

However, in the 12 short days left before Malcolm departed again for Africa, he and King were not able to arrange a meeting to explore their mutual interest in a human rights declaration. Nor would they ever manage to see each other again in the three months remaining in Malcolm’s life once he returned to the U.S., though they would just miss doing so in Selma, Alabama. Nevertheless, through its electronic surveillance of both men, the FBI knew that Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. were hoping to connect on the human rights issue that could put the U.S. on trial in the United Nations.

On June 28, 1964, Malcolm announced his formation of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), with its headquarters at the Theresa Hotel in Harlem. Whereas the Muslim Mosque, Inc. was faith-oriented, the OAAU would be politically oriented.98 The OAAU would be patterned after the letter and spirit of the Organization of African Unity established by African heads of state the year before at their meeting in Ethiopia. The OAAU’s founding statement emphasized that “the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Constitution of the U.S.A. and the Bill of Rights are the principles in which we believe.”99 The intended outreach of Malcolm’s organization was transcontinental, including “all people of African descent in the Western Hemisphere, as well as our brothers and sisters on the African continent.”100 Yet the organizing would also be local and civic:

The Organization of Afro-American Unity will organize the Afro-American community block by block to make the community aware of its power and potential; we will start immediately a voter registration drive to make every unregistered voter in the Afro-American community an independent voter.101

Thanks to Mecca, Malcolm had broken free from his old allegiance to Elijah Muhammad’s idea of a separate black state. He was now organizing an international campaign for Afro-American liberation based on the principles of the U.S. Constitution and the UN Charter. He had become a faith-based organizer on an international scale. His OAAU founding statement, while consistent with the Civil Rights Movement, took the struggle into a new arena, the United Nations. Malcolm would now seek further support for his UN human rights campaign by a July-November barnstorming trip through Africa.

In addition to NYPD and FBI surveillance, the Central Intelligence Agency was also following Malcolm. The Agency knew Malcolm planned to appeal to African leaders at the second conference of the Organization of African Unity (OAU).

At 11:37 p.m., on July 3, 1964, Malcolm phoned the New York Police Department to report that “two Black Muslims were waiting at his home to harm him. … But he sped off when they approached his car.”102 Malcolm knew the name of one of the two men, and gave it to the police.103

The NYPD refused to believe Malcolm. They passed on their official skepticism in a July 4 teletype to the FBI: “Police believed complaint on an attempt on Malcolm’s life was a publicity stunt by Malcolm.”104 By its phone tap, the FBI had heard Malcolm make his report at the same time the NYPD did. The Bureau summarized the event with its own judgment on Malcolm: “Information [on 7/4/64] that MALCOLM and his followers were attempting to make a big issue out of the reported attempt on Macolrn’s life in order to get the Negro people to support him.105

Thus began the official NYPD and FBI line that Malcolm was fabricating attempts on his life for the sake of publicity. This disclaimer would be made publicly by the NYPD in the week before Malcolm’s murder, in an effort to justify the withdrawal of police protection at the time of escalating threats on his life.

On July 9, Malcolm departed from New York on the African trip that would consume four and a half of the remaining seven and a half months of his life. It was to be the final, most ambitious project of his short life. As his plane lifted off from JFK Airport on its way to Cairo, Malcolm was happily unaware of what John Ali was saying that same night on a Chicago call-in radio program:

Malcolm X probably fears for his safety because he is the one who opposes the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. The Holy Koran, the book of the Muslims, says “seek out the hypocrites and wherever you find them, weed them out.” … There were people who hated Kennedy so much that they assassinated him—white people. And there were white people who loved him so much they would have killed for him. You will find the same thing true of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad … I predict that anyone who opposes the Honorable Elijah Muhammad puts their life in jeopardy … 106

“… after every one of my trips abroad, America’s rulers see me as being more and more dangerous. That’s why I feel in my bones the plots to kill me have already been hatched in high places. The triggermen will only be doing what they were paid to do.”

In addition to NYPD and FBI surveillance, the Central Intelligence Agency was also following Malcolm. The Agency knew Malcolm planned to appeal to African leaders at the second conference of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), which he was attending in Cairo in July as an honored observer. No other American was allowed in the door. In a July 10 CIA memorandum, an informant stated that Malcolm X was “transporting material dealing with the ill treatment of the Negro in the United States. He intends to make such material available to the OAU in an effort to embarrass the United States.”107

In Cairo, Malcolm was constantly aware of agents following him. They made their presence obvious in an effort to intimidate him. Then on July 23, as Malcolm prepared to present his UN appeal to Africa’s leaders, he was poisoned. He described the experience later to a friend:

I was having dinner at the Nile Hilton with a friend named Milton Henry and a group of others, when two things happened simultaneously. I felt a pain in my stomach and, in a flash, I realized that I’d seen the waiter who served me before. He looked South American, and I’d seen him in New York. The poison bit into me like teeth. It was strong stuff. They rushed me to the hospital just in time to pump the stuff out of my stomach. The doctor told Milton that there was a toxic substance in my food. When the Egyptians who were with me looked for the waiter who had served me, he had vanished. I know that our Muslims don’t have the resources to finance a worldwide spy network.108

The friend who witnessed this event, Detroit civil rights attorney Milton Henry, warned Malcolm that his UN campaign could mean his death. Henry later felt in retrospect that it did: “In formulating this policy, in hitting the nerve center of America, he also signed his own death warrant.”109 Malcolm, being Malcolm, recognized the truth of Henry’s warning, and went right on ahead with his campaign.

At the OAU conference, Malcolm submitted an impassioned, eight-page memorandum urging the leaders of Africa to recognize African-Americans’ problems as their problems and to indict the U.S. at the UN:

Your problems will never be fully solved until and unless ours are solved. You will never be fully respected until and unless we are also respected. You will never be recognized as free human beings until and unless we are also recognized and treated as human beings. Our problem is your problem. It is not a Negro problem, nor an American problem. This is a world problem, a problem for humanity. It is not a problem of civil rights but a problem of human rights. In the interests of world peace and security, we beseech the heads of the independent African states to recommend an immediate investigation into our problem by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights.110

|

| Malcolm at OAU |

Malcolm was encouraged by the response he received from the OAU. Although the resolution the conference passed in support of the African-American struggle used only moderate language, Malcolm told Henry that several delegates had promised him their official support in bringing up the issue legally at the United Nations.111

|

| OAU Founders |

Malcolm then built on the foundations he had laid at the African summit. For four months he criss-crossed Africa, holding follow-up meetings with the leaders who encouraged him most in Cairo. He held long discussions with President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, President Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Prime Minister Milton Obote of Uganda, President Azikiwe of Nigeria, President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Prime Minister Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria, and President Sekou Toure of Guinea.112 There were other African heads of state Malcolm talked with, he said, “whose names I can’t mention.”113 At the height of the Cold War, Malcolm X had gained access to Africa’s most revolutionary leaders on a politically explosive issue.

|

The neutralist leaders

(Nehru, Nkrumah, Nasser, Sukarno, Tito) |

Reflecting on these meetings, Malcolm told a friend in London shortly before his death,

Those talks broadened my outlook and made it crystal clear to me that I had to look at the struggle in America’s ghettos against the background of a worldwide struggle of oppressed peoples. That’s why, after every one of my trips abroad, America’s rulers see me as being more and more dangerous. That’s why I feel in my bones the plots to kill me have already been hatched in high places. The triggermen will only be doing what they were paid to do.114

U.S. intelligence agencies were in fact monitoring Malcolm’s campaign in Africa with increasing concern. The officials to whom they reported these developments began to express their alarm publicly. As a New York Times article, written in Washington revealed on August 13, 1964, “The State Department and the Justice Department have begun to take an interest in Malcolm X’s campaign to convince African states to raise the question of persecution of American Negroes at the United Nations.”

After recapitulating Malcolm’s appeal to the 33 OAU heads of state, the Times article stated:

[Washington] officials said that if Malcolm succeeded in convincing just one African Government to bring up the charge at the United Nations, the United States Government would be faced with a touchy problem. The United States, officials here believe, would find itself in the same category as South Africa, Hungary, and other countries whose domestic politics have become debating issues at the United Nations. The issue, officials say, would be of service to critics of the United States, Communist and non-Communist, and contribute to the undermining of the position the United States has asserted for itself as the leader of the West in the advocacy of human rights.115

The Times reported that Malcolm had written a friend from Cairo that he did indeed have several promises of support from African states in bringing the issue before the United Nations. According to another diplomatic source, Malcolm had not been successful, “but the report was not documented and officials here today conceded the possibility that Malcolm might have succeeded.”116

The article also said somewhat ominously;

Although the State Department’s interest in Malcolm’s activities in Africa is obvious, that of the Justice Department is shrouded in discretion. Malcolm is regarded as an implacable leader with deep roots in the Negro submerged classes.

“[He] has, for all practical purposes, renounced his U.S. citizenship.” ~ Benjamin H. Read, assistant to Dean Rusk, insisting the CIA investigate Malcolm X

These two sentences, which were removed from the article in the national edition of the Times,117 where an oblique reference to concerns about Malcolm then being expressed not only by the State and Justice Departments but also by the CIA, FBI, and the Johnson White House. These concerns are revealed by a memorandum, written two days before the Times article, addressed to the CIA’s Deputy Director of Plans (covert action) Richard Helms. As researchers know, the desk of Richard Helms—a key player in CIA assassination plots—was perhaps the most dangerous place possible for a report on a perceived security risk to end up. According to the August 11, 1964, CIA memorandum to Helms, the Agency claimed it had learned from an informant that Malcolm X and “extremist groups” were being funded by African states in fomenting recent riots in the U.S. The State Department, the CIA memo continued, “considered the matter one of sufficient importance to discuss with President Johnson who, in turn, asked Mr. J. Edgar Hoover to secure any further information which he might be able to develop.”118

As Malcolm analyst Karl Evanzz has noted,

In fact, the CIA knew the allegations were groundless. In an FBI memorandum dated July 25, a copy of which was sent to [the CIA’s] Clandestine Services, an agent specifically stated that the informant’ said he didn’t mean to imply that Africans were financing Malcolm X.119

The CIA’s August 11 memo also stated that Benjamin H. Read, an assistant to Secretary of State Dean Rusk, wanted the CIA to probe both Malcolm X’s domestic activities and “travels in Africa” to determine “what political or financial support he may be picking up along the way.” The CIA memo’s author had told Read, coyly, in response that “there were certain inhibitions concerning our activities with respect to citizens of the United States.” Read had overridden the objection, insisting the CIA act because, “after all, Malcolm X has, for all practical purposes, renounced his U.S. citizenship.”120

As of no later than August 11, 1964 (and perhaps before), the CIA’s Deputy Director of Plans had been authorized to act on Malcolm X. Malcolm was perceived, for all practical purposes, to have renounced his U.S. citizenship and to have become a touchy problem to the U.S. government if he gained so much as one African state’s support for his UN petition. Malcolm had not read any such CIA documents on himself, but he had seen the August 13 Times article. He could read his future between its lines, just as Milton Henry had already done in terms of the sensitivity of Malcolm’s UN campaign.

|

| John Lewis |

John Lewis, a leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) who would go on to become a member of Congress, was then touring Africa to connect with the freedom movement there. Lewis and the SNCC friends who were with him knew all too well that Malcolm was also in Africa. As soon as they met anyone in Africa, the first question they would inevitably be asked was: “What’s your organization’s relationship with Malcolm’s?”121 The men discovered that no one would listen to them if they were seen as being any less revolutionary than Malcolm, who seemed to have taken all of Africa by storm. On his return to the U.S. Lewis wrote in a SNCC report: “Malcolm’s impact on Africa was just fantastic. In every country he was known and served as the main criteria for categorizing other Afro-Americans and their political views.”122

Lewis was startled to run into Malcolm in a café in Nairobi, Kenya, as he had thought Malcolm was traveling in a different part of Africa at the time. Malcolm, recognizing Lewis, smiled and asked what he was doing there. Reflecting on their encounter in his memoir, Walking With the Wind, Lewis thought Malcolm was very hopeful from the overwhelming reception he had received in Africa “by blacks, whites, Asians and Arabs alike.” It “had pushed him toward believing that people could come together.”123

However, something else Malcolm shared with the SNCC group “was a certainty that he was being watched, that he was being followed … In a calm, measured way he was convinced that somebody wanted him killed.”124 John Lewis’ meeting with Malcolm in Kenya would be the last time he would see him alive.

|

| Louis Farrakhan (1965) |

Malcolm kept extending his stay in Africa. He had planned to be away six weeks. After 18 weeks abroad, he finally flew back to New York on November 24, 1964. He was confronted, soon after his return, with a December 4 issue of Muhammad Speaks. The issue featured an attack upon him by Minister Louis X, of the NOI’s Boston mosque. Louis X had not long before been a friend and devoted disciple to Malcolm. Now calling Malcolm “an international hobo,” Louis X made a statement against Malcolm that would haunt the speaker for the rest of his life, under his better-known name, Minister Louis Farrakhan:

The die is set, and Malcolm shall not escape, especially after such evil, foolish talk about his benefactor, Elijah Muhammad, in trying to rob him of the divine glory which Allah had bestowed upon him. Such a man as Malcolm is worthy of death, and would have met with death if it had not been for Muhammad’s confidence in Allah for victory over his enemies.125

Louis Farrakhan has never admitted to having participated in the plot to kill Malcolm. He has acknowledged from 1985 on that his above words “were like fuel on a fire” and “helped create the atmosphere” that moved others to kill Malcolm. Farrakhan made essentially the same carefully worded statement to four interviewers: Tony Brown in 1985, Spike Lee in 1992, Barbara Walters on 20/20 in 1993, and Mike Wallace on 6o Minutes in 2000. His words to Spike Lee were: “I helped contribute to the atmosphere that led to the assassination of Malcolm X.”126

His clearest statement on Malcolm’s murder may be at question. In a 1993 speech to his NOI congregation, Minister Farrakhan, referring to Malcolm, asked bluntly, “And if we dealt with him like a nation deals with a traitor, what the hell business is it of yours?”127

|

| Alex Quaison-Sackey |

The timing of Malcolm’s late November return to the U.S. seemed providential in terms of his work at the United Nations. On December 1, his close friend, Alex Quaison-Sackey of Ghana, was elected President of the UN General Assembly. Following Malcolm’s lead, Quaison-Sackey was becoming increasingly outspoken against U.S. policies. Quaison-Sackey gave Malcolm’s human rights campaign a further boost by arranging for him to open an office at the UN in the area that was used by provisional governments.128

The FBI’s New York field office pointed out to J. Edgar Hoover in a December 3 memo the alarming facts that Malcolm X and newly elected UN leader Quaison-Sackey had been friends for four years, and that they had also met several times recently. The New York office, which worked closely with the NYPD’s undercover BOSSI unit, suggested to Hoover “that additional coverage of [Malcolm X’s] activities is desirable particularly since he intends to have the Negro question brought before the United Nations (UN).”129

During December’s UN debate on the Congo, Malcolm’s influence began to be heard in the speeches of African leaders. For example, Louis Lansana Beavogui, Guinea’s foreign minister, asked why “so-called civilized governments” had not spoken out against “the thousands of Congolese citizens murdered by the South Africans, the Belgians, and the [anti-Castro] Cuban refugee adventurers. Is this because the Congolese citizens had dark skins just like the colored United States citizens murdered in Mississippi?”130

In a January 2, 1965, article, the New York Times described the Malcolm X impetus behind this challenging turn in African attitudes. It noted that the policy proposed by Malcolm that “linked the fate of the new African states with that of American Negroes” was being adopted by African governments. The article said, “the African move profoundly disturbed the American authorities, who gave the impression that they had been caught off-guard.”131

Those working behind the scenes were not caught off guard, however, as the knowledgeable author of the article, M.S. Handler, was quick to suggest. Handler had also written the August 13 Times piece from Washington. He went on to repeat what he had reported then, that “early last August the State Department and Justice Department began to take an interest in Malcolm’s activities in North Africa”—accompanied, as we know, by a parallel interest and stepped-up actions by the CIA and FBI. Handler traced the heightened government interest to Malcolm’s opening “his campaign to internationalize the American Negro problem at the second meeting of the 33 heads of independent African states in Cairo, which convened July 17.”132

When the January 2 Times article appeared, Malcolm had seven weeks left to live. Much of the remaining time was devoted to his constant speaking trips throughout the U.S., up to Canada, and over to Europe. Malcolm lived each day, hour, and minute as if it were his last, for he knew how committed the forces tracking him were to killing him. Within the U.S., Fruit of Islam killing squads were waiting for him at every stop. Malcolm knew it was only a matter of time.

On January 28, 1965, Malcolm flew to Los Angeles to meet with attorney Gladys Towles Root and two former NOI secretaries who were filing paternity suits against Elijah Muhammad.133 Malcolm felt personally responsible for having put the two women in a position of vulnerability to Elijah Muhammad. He told a friend, “My teachings converted these women to Elijah Muhammad. I opened their mind for him to reach in and take advantage of them.”134 He had come to Los Angeles, in preparation for testimony in support of the women, “to undo what I did to them by exposing them to this man.”135

From the time Malcolm arrived at the Los Angeles Airport in mid-afternoon until his departure the next morning, he was trailed by the Nation of Islam. The two friends who met him, Hakim A. Jamal and Edmund Bradley, had alerted airport security to a possible NOI attack. As Jamal and Bradley waited at the gate, they noticed a black man seated behind them inconspicuously reading a newspaper. The man was John Ali. Although Malcolm’s Los Angeles trip had been a closely held secret, someone monitoring his conversations was feeding the information to Ali. Malcolm’s arrival gate was switched at the last moment, and security police rushed him and his companions safely through the airport to a car.136

At his Statler Hilton Hotel, Malcolm repeatedly had to run a gauntlet of menacing NOI men stationed in the lobby. Bradley saw John Ali and the leaders of an NOI mosque in Los Angeles get out of a car in front of the hotel. Malcolm, Jamal, and Bradley left quickly in their own car to meet with the two secretaries and attorney Root. When Bradley drove Malcolm back to the airport in the morning, two carloads of NOI teams started to pull alongside their car. Malcolm picked up Bradley’s cane and stuck it out a window like a rifle. The two cars fell back. Police waiting at the airport escorted Malcolm safely to his plane.137