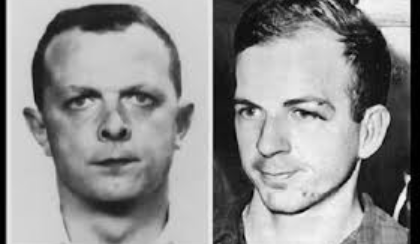

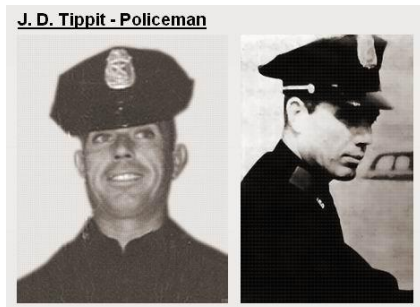

The murder of Officer J.D. Tippit in Oak Cliff was famously cited by David Bellin, Assistant Counsel to the Warren Commission, as being the “Rosetta Stone to the solution” of the JFK assassination. (Jim Marrs, Crossfire, p. 340, all references are to the 1989 edition) “Once it is admitted that Oswald killed Patrolman J.D. Tippit,” the attorney for the commission observed, “there can be no doubt that the overall evidence shows that Lee Harvey Oswald was the assassin of John F. Kennedy.”

Following Mr. Belin’s questionable logic might also lead one to believe the opposite to be true. Once it is shown that Oswald likely did not kill Patrolman Tippit, the case for him having shot President Kennedy and Governor Connally is, therefore, demonstrably weakened.

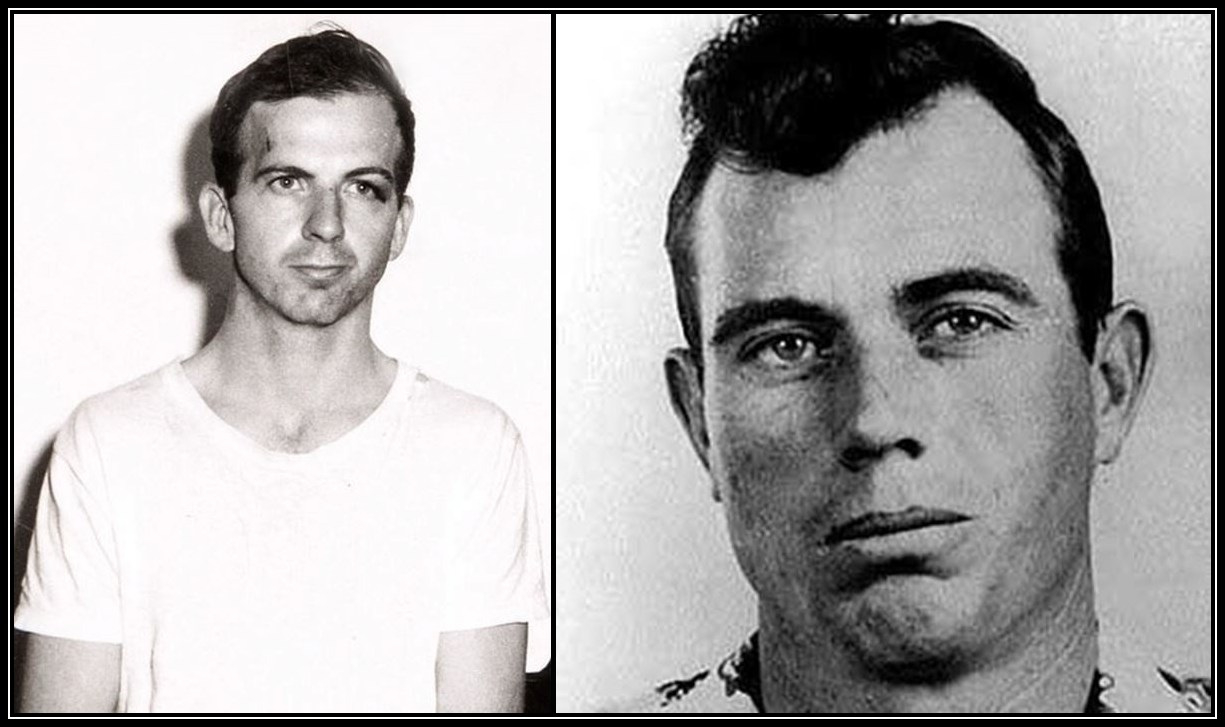

“I emphatically deny these charges!” shouted Oswald to news reporters while in Dallas police custody. “I didn’t shoot anybody, no sir … I’m just a patsy!” Oswald denied his guilt in many ways and more than once. (Mark Lane, Rush to Judgment, p. 81)

Was the suspect telling the truth?

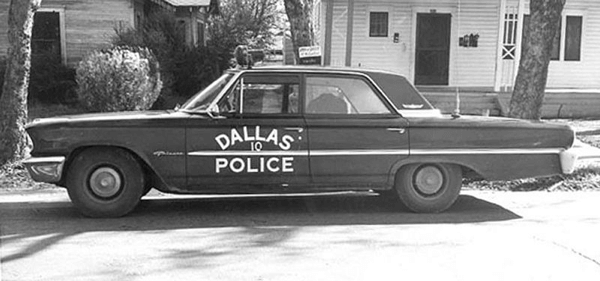

Sadly, within less than 48 hours, shadowy nightclub owner Jack Ruby would all but terminate the official Dallas Police investigation into the Tippit homicide when he gunned down suspect Lee Oswald in the basement of Dallas Police Headquarters. That unfathomable event, broadcast live on national television, occurred in the presence of more than 50 Dallas policemen. It was their job to ensure Oswald’s safety while he was in custody—so the suspect might be tried on charges of assassinating President Kennedy and murdering Officer Tippit.

“We never worked on any of his (Tippit’s) murder, because there was no use making a murder case (with the suspect dead),” admitted former District Attorney Henry Wade in an interview with veteran Tippit researcher Joseph McBride. “I think we had enough evidence that Oswald did it.”

And despite Belin’s “Rosetta Stone” reference, not only did Dallas authorities abandon the Tippit case, but the Warren Commission, according to McBride, showed “almost no real interest in solving the crime … the commission was deliberately stonewalling a serious investigation of Tippit.”

Any “serious” investigation into Tippit’s death must begin with one fundamental and all-important question: Why did Tippit stop Oswald?

Based on the persistence of several indefatigable private researchers and investigators who kept digging into the Tippit mystery for decades, I believe we can now attempt to answer that question. The answer, it would seem, had nothing to do with the man walking on 10th Street in Oak Cliff matching the Dealey Plaza suspect’s generic description of being a young white male of average height and weight—as was suggested by the Warren Commission.

In the words of Sylvia Meagher, writing in her 1967 book Accessories After the Fact, “The strangeness of Tippit’s actions,” suggests that “it was not probable, perhaps not even conceivable, that Tippit stopped the pedestrian who shot him because of the description broadcast on the police radio. The facts indicate that Tippit was up to something different which, if uncovered, might place his death and the other events of those three days in a completely new perspective.” (See Meagher, pp. 260-66)

What follows in this article is a “new perspective.”

12:00 P.M.

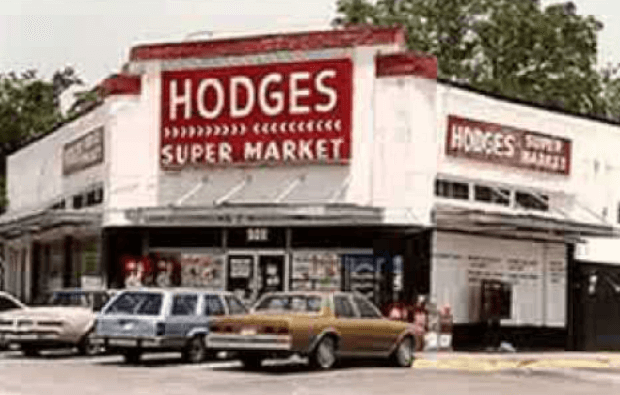

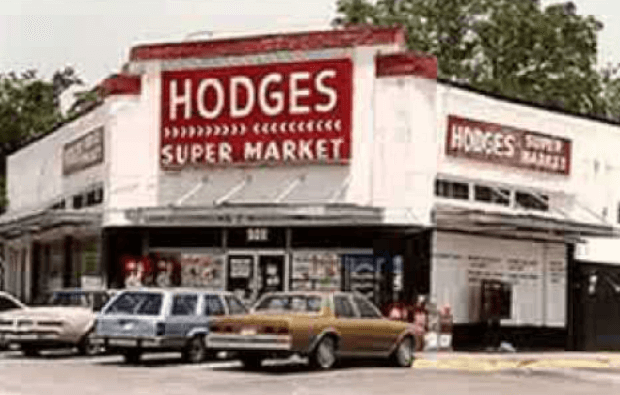

The “strangeness” of Tippit’s actions on 11/22/63 appear to have begun even before shots rang out in downtown Dallas. Tippit, whose normal area of patrol was in Cedar Crest, patrol area #78, was apparently called to a supermarket in the 4100 block of Bonnie View Road. Respected Tippit researcher Larry Ray Harris interviewed the Hodges Supermarket manager in 1978. As described in news reporter Bill Drenas’ oft-cited 1998 article Car #10 Where are You?, the manager told Harris he had caught a woman shoplifter on 11/22/63 and had phoned police.

It was Tippit who responded to that location at about noon, just a half hour before the assassination. The manager knew Tippit, because Tippit routinely came to the market on calls for shoplifters. The interviewee said Tippit placed the woman in his squad car and left. However, Tippit appears not to have brought the shoplifting suspect back to his nearby base of operations. No record of the woman’s arrest or information on who she was or what happened to her has ever surfaced.

12:30 p.m.

President Kennedy’s motorcade was scheduled to have arrived at the Dallas Trade Mart at 12:30. However, because the motorcade was running a few minutes late, President Kennedy was assassinated at 12:30, and Governor Connally was gravely injured, as the motorcade proceeded through Dealey Plaza on route to the Trade Mart. The Hodges Market in the 4100 block of Bonnie View in Tippit’s district was more than seven miles southwest of Dealey Plaza.

12:40 p.m.

The DPD Channel 1 dispatcher reports a shooting in the downtown area involving the President. By this time, Texas School Book Depository employee Lee Oswald has already grabbed his blue work jacket and has left the TSBD on foot. He will board a city bus, but when that bus gets stalled in traffic, Oswald will ask for a transfer, depart from the bus, and walk to a cab stand to catch a quicker ride (with cab driver William Whaley) out to nearby Oak Cliff where the young man resides.

The DPD Channel 1 dispatcher next orders “all downtown area squads” to Dealey Plaza, code 3 (lights and sirens). By 12:44, a general description of the Kennedy suspect (slender white male, 5’10” and 160 pounds) is broadcast over both Channels 1 and 2.

12:45 p.m.

Murray Jackson, the dispatcher, asks Tippit to report his location. Tippit replies, according to police radio logs, that “I am about Keist and Bonnie View,” which is still within Tippit’s regular patrol district down in Cedar Crest. (Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, p.441) However, this may not have been the case.

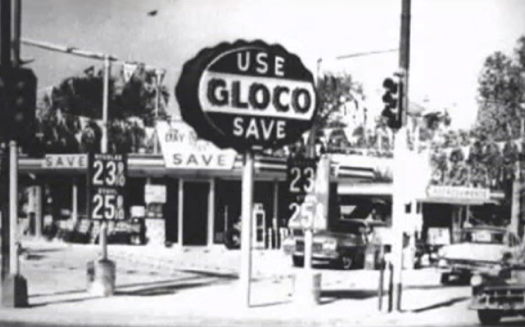

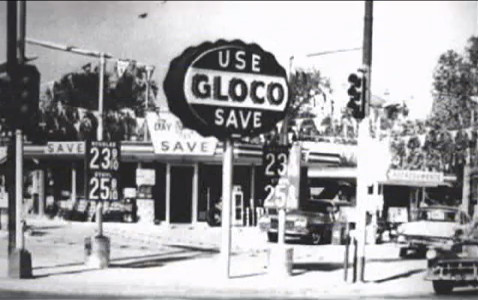

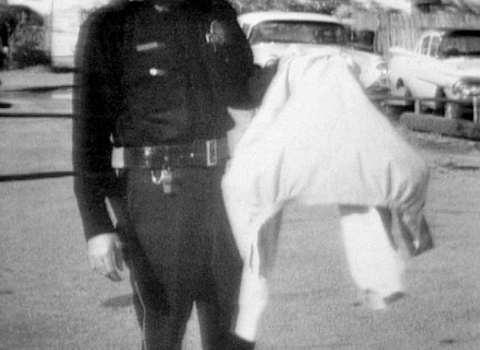

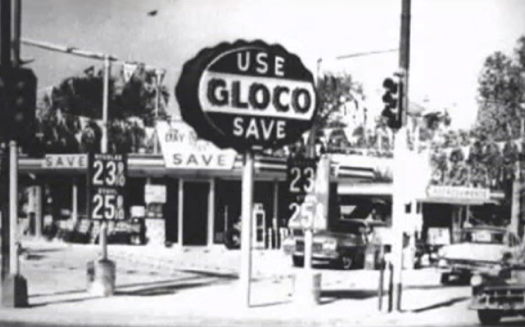

Beginning at approximately 12:45, when Officer Tippit reports he is still in his regular patrol area, Tippit will instead be seen sitting inside his squad car parked at the GLOCO gas station, strategically situated in northernmost Oak Cliff next to the Houston Street viaduct. The viaduct connects downtown Dallas and Dealey Plaza to Oswald’s neighborhood in Oak Cliff—some five miles north of Tippit’s reported position.

Researcher William Turner, in a 1966 article in the magazine Ramparts, claimed he located five witnesses who saw Tippit sitting in his patrol car at the gas station at this time while watching traffic coming across from downtown Dallas. (McBride, ibid) The location is only 1.5 miles from Dealey Plaza. Two of the witnesses, a husband and wife who knew the officer, say they waved at Tippit who waved back at them. The story was reportedly verified by three of the GLOCO station attendants. Dallas researchers Greg Lowrey and Bill Pulte also interviewed all five of these witnesses to confirm the story. Some said that Tippit arrived at the GLOCO as early as just “a few minutes” after the assassination.

Was Tippit watching for Oswald to come across the viaduct on a Dallas bus? Did he see Oswald instead in the front of William Whaley’s cab? What was Tippit doing?

12:46 p.m.

At this time, dispatcher Murray Jackson ordered Officers Tippit and R.C. Nelson into the Central Oak Cliff area, which was odd since an assigned officer (William Mentzel) was already patrolling Central Oak Cliff. (McBride, pp. 427-30) Tippit, according to witnesses, is of course already there in the northernmost part of Oak Cliff at the gas station. (This was probably unknown to Jackson, since Tippit had just responded to the dispatcher that he was in his assigned patrol area at Bonnie View & Keist some five miles to the south). Officer Nelson instead proceeded on to Dealey Plaza, possibly following the preceding 12:42 “code 3” order for all downtown area squads to report to Dealey Plaza. (Henry Hurt, Reasonable Doubt, pp. 161-63)

Meanwhile, Oswald will soon be crossing the Houston St. viaduct in William Whaley’s cab, heading for Oak Cliff.

The witnesses say that after some 10 minutes of sitting at the gas station, watching traffic crossing from the downtown area, Tippit suddenly pulled out and took off south on Lancaster Avenue “at a high rate of speed.”

12:52 or 12:53 p.m.

Cab driver William Whaley lets Oswald out at the corner of North Beckley and Neely Street, several blocks south of Oswald’s rooming house, which the cab has already passed. Whaley had marked Oswald’s intended location on his run sheet as the 500 block of N. Beckley, even farther south and in the wrong direction from the rooming house. The 500 block of N. Beckley was, in 1963, dominated by the side parking lot of the El Chico Restaurant.

12:54 p.m.

Dispatcher Murray Jackson contacts Tippit, who is now about a mile from the GLOCO Station on Lancaster Street. (McBride, p. 445) Oswald and Tippit are both apparently moving in the direction of the Texas Theater.

1:00 to 1:07 p.m.

Texas Theater manager Butch Burroughs said Oswald entered the theater during this timeframe and later bought popcorn from him at the concession stand at approximately 1:15. (McBride, p. 520) Other movie patrons will similarly report having seen Oswald in the mostly empty theater during the start of the movie, changing seats frequently and sometimes sitting directly next to other moviegoers. Is Oswald supposed to meet someone he doesn’t know personally, perhaps his intelligence contact to whom he is expected to give a briefing?

After 1:00 p.m.

Employees of the Top Ten Records store, located a block and a half west of the Texas Theater on Jefferson Boulevard, later claim that Tippit parked his squad car on Bishop Street adjacent to the records store and came in hurriedly while asking to use the phone.

Employees of the Top Ten Records store, located a block and a half west of the Texas Theater on Jefferson Boulevard, later claim that Tippit parked his squad car on Bishop Street adjacent to the records store and came in hurriedly while asking to use the phone.

A Dallas Morning News reporter interviewed former Top 10 clerk Louis Cortinas in 1981. Cortinas recalled that, “Tippit said nothing over the phone, apparently not getting an answer. He stood there long enough for it to ring seven or eight times. Tippit hung up the phone and walked off fast, he was upset or worried about something.” (McBride, p. 451)

Had Tippit picked up Oswald near the El Chico Restaurant and then dropped him off at the Texas Theater? Had Tippit simply been watching the theater to confirm Oswald’s arrival? Or, was Tippit simply trying to contact someone to find out the latest news on the condition of President Kennedy and Governor Connally?

1:03 p.m.

Around this time, police dispatcher Murray Jackson tries to radio Tippit, but gets no answer. (Meagher, p. 266) Was this when Tippit was entering the Top 10 records store to place the phone call?

Approximately 1:04 p.m.

Several blocks east of Top 10 and the Texas Theater, an unknown young white male about 5’8” to 5’10” and 165 pounds wearing a white shirt and light tan Eisenhower jacket begins to quickly walk west on East 10th Street. The man is in such a hurry that he catches the attention of those inside of Clark’s Barber Shop at 620 E. 10th as he breezes by that establishment’s storefront window. A pedestrian, Mr. William Lawrence Smith, passes the same man as Smith walks east to lunch at the Town & Country Café just a few doors west of the barber shop. (John Armstrong, Harvey and Lee, p. 841)

Approximately 1:05 p.m.

As the unknown white male proceeds west and crosses the intersection of 10th and Marsalis, a major disturbance suddenly breaks out at that corner. Bill Drenas, author of the 1998 article Car #10 Where Are You?, mentioned that a person near the scene of the Tippit shooting told investigator Bill Pulte that, “If you are planning to do more research on Tippit, you should find out about the fight that took place at 12th & Marsalis a few minutes before Tippit was killed.” The interviewee spoke only on the condition of anonymity.

Harrison Livingstone, in his 2006 book The Radical Right and the Murder of John F. Kennedy, adds more crucial detail about this mysterious neighborhood altercation. “There are neighborhood reports of a disagreement at the intersection of 12th & Marsalis,” writes Livingstone, “a few minutes before Tippit was killed. Tippit was headed precisely toward 12th & Marsalis when he left Lancaster & 8th (the report of the 12th & Marsalis argument is from someone whose identity needs to be protected).

“The late Cecil Smith witnessed this fight which was actually at 10th & Marsalis (my emphasis). One of the two individuals was stabbed, but it was never investigated, apparently … just two blocks east from where Tippit was shortly murdered.” The fight also occurred, let it be known, at the same time and location the unknown gunman in the light jacket, white shirt, and dark trousers is passing on his way two blocks west to the fast approaching scene of the fatal Tippit shooting.

But it was not until Dallas researchers Michael Brownlow and Professor William Pulte made public their findings in a 2015 Youtube video that we get the full scoop on this most unusual so-called “fight.”

Brownlow said it was actually three men and a woman who jumped on another man at the corner, who was then “violently” stabbed. The wounded man, bleeding profusely, was then inexplicably thrown into the back of a blue Mercury Monterey which sped away from the scene. Many people witnessed the assault. 10th & Marsalis was a commercial corner, with an auto parts store, a plumbing supply store, and other nearby businesses such as the barber shop and restaurant. It was Indian summer, pre-air conditioning days, and most of these businesses had telephones within easy reach. Neighbors and teens home from school also allegedly witnessed the noisy and bloody altercation. (See also, Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, pp. 447-48)

Brownlow said it was actually three men and a woman who jumped on another man at the corner, who was then “violently” stabbed. The wounded man, bleeding profusely, was then inexplicably thrown into the back of a blue Mercury Monterey which sped away from the scene. Many people witnessed the assault. 10th & Marsalis was a commercial corner, with an auto parts store, a plumbing supply store, and other nearby businesses such as the barber shop and restaurant. It was Indian summer, pre-air conditioning days, and most of these businesses had telephones within easy reach. Neighbors and teens home from school also allegedly witnessed the noisy and bloody altercation. (See also, Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, pp. 447-48)

Emergency phones calls were obviously placed to the Dallas Police, although you won’t find any mention of this incident in the DPD call logs for 11/22/63. Why not?

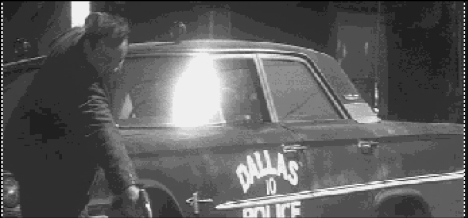

Approximately 1:05:30

Officer Tippit, now sitting once again in his patrol car outside of the Top 10 Records store, suddenly hears his police radio crackle to life. There has been a reported fight and possible stabbing at the corner of 10th & Marsalis, several blocks east of where his patrol car now sits near the corner of West Jefferson Blvd. and Bishop Avenue. A man has supposedly been stabbed and thrown into the back of a blue car which drove away from the scene. Tippit puts Car #10 into gear and moves out in a big hurry.

The employees at Top Ten (Lou Cortinas and Dub Stark) watch through their front window as Tippit’s car goes charging through the intersection and races north up to Sunset Street where Tippit blows through the stop sign and disappears from view. (McBride, pp. 451-550)

The employees at Top Ten (Lou Cortinas and Dub Stark) watch through their front window as Tippit’s car goes charging through the intersection and races north up to Sunset Street where Tippit blows through the stop sign and disappears from view. (McBride, pp. 451-550)

Approximately 1:06:00

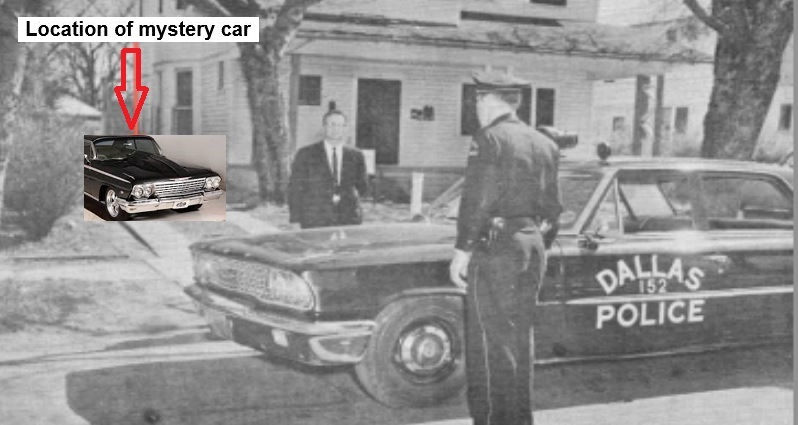

Tippit quickly reaches 10th Street and is about to turn right, heading east towards the disturbance at the corner of 10th & Marsalis. But he instead observes a late model Chevrolet headed west on 10th. Could this be the car escaping from the scene of the fight? So instead of turning right, Tippit makes a quick decision and turns left, following the Chevy that has just passed in front of him. Within a block the officer speeds up, passes the Chevy, turns the wheel, and forces the surprised driver to come to a stop at the curb.

Mr. James Andrews, the motorist—who had been returning to work from his lunch hour—would later give Dallas researcher Greg Lowrey (as reported in Bill Drenas’ article Car #10 Where Are You?) the following description of this bizarre event:

Drenas writes that “The officer then jumped out of the patrol car, motioned for Andrews to remain stopped, ran back to Andrew’s car, and looked in the space between the front seat and the back seat (emphasis mine). Without saying a word, the policeman went back to the patrol car and drove off quickly. Andrews was perplexed by this strange behavior and looked at the officer’s nameplate which read ‘Tippit’ … Andrews remarked that Tippit seemed to be very upset and agitated and acting wild.” (McBride, pp. 448-49)

Much has been made of this incident, which apparently happened just a few short moments prior to Tippit’s death. Some have reasoned that Tippit was looking for Oswald, thought to be hiding in the back of an automobile on his way to Red Bird Airport to catch a flight out of town. Others have found the story so odd that they have tended to dismiss it altogether—couldn’t have happened.

But now that we have a report about a fight at 10th & Marsalis, a stabbing in which the victim was thrown into the back of a car which then sped away from the scene, Tippit’s “wild” actions perhaps make more sense. Tippit may have been looking for the injured stabbing victim in the back of an escaping vehicle—and he was doing so alone, with no backup. That is why he was agitated and acting upset. President Kennedy and Governor Connally have just been gunned down in Dealey Plaza and now Tippit is dealing with a violent, potentially life and death situation in adjoining Oak Cliff.

1:07:00 p.m.

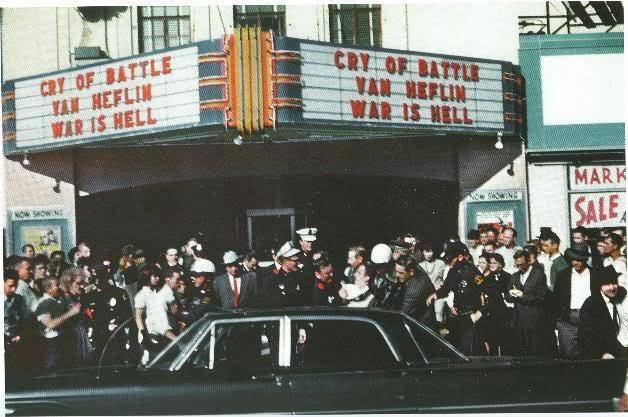

Officer Tippit heads east on 10th Street, heading towards the scene of the reported disturbance at the corner of Marsalis. By now, according to Texas Theater Manager Butch Burroughs—as well as multiple paying customers—Lee Oswald is most definitely in the building for the start of the afternoon’s double war movie feature. (Marrs, Crossfire, pp. 352-53)

1:08:00 p.m.

As Officer Tippit travels east on 10th towards Marsalis, he spots a lone figure walking west just two blocks from the scene of the stabbing incident. Tippit slows Car #10 as he cruises through the intersection of 10th & Patton. Cab driver Bill Scoggins, parked near the corner in his cab while eating his lunch, notices Tippit pass in front of his cab, slow down, and suddenly pull to the curb about 100 feet past Patton Street. The officer apparently summons the young pedestrian, who is wearing the beige Eisenhower jacket, dark trousers, and white shirt, back to his patrol car.

The young man does an about-face, turning around to approach Tippit’s car sitting at curbside. Could this young man have been a witness? A participant in the fight? He doesn’t appear to have any blood on his jacket that the officer can see. Tippit and the young man, who is now leaning over, have a brief conversation through the open vent on the passenger-side window.

The young man does an about-face, turning around to approach Tippit’s car sitting at curbside. Could this young man have been a witness? A participant in the fight? He doesn’t appear to have any blood on his jacket that the officer can see. Tippit and the young man, who is now leaning over, have a brief conversation through the open vent on the passenger-side window.

1:08:30 p.m.

Officer Tippit, who probably does not fully believe the young man’s story about who he is and what business he has on 10th Street, decides to get out of his car to question the subject further. He adjusts his police cap, begins to walk slowly towards the front of Car #10. As he does, the man pulls a .38 revolver from under his jacket and begins to fire.

No one sees the actual shots. A passing motorist, Domingo Benavides, is startled by the gunfire as he approaches Car #10 while traveling west on 10th. In an act of instinct and self-preservation, Benavides turns his pickup to the curb and ducks down behind the dashboard. (Lane, pp. 177-78)

Cabbie Bill Scoggins sees Tippit fall into the street. A few seconds later, he observes the figure of the young man walking quickly towards his cab, cutting across the adjacent corner property on 10th Street. Scoggins steps out of his cab and hides behind the driver-side fender. The young man emerges from the lawn’s hedges and begins to trot south on Patton Street, still tossing the occasional empty shell to the ground. (Lane, pp. 191-93)

Hearing no further shots, Benavides pokes his head up in time to see the gunman heading for Patton Street, inexplicably tossing a couple of shells into the bushes. Benavides will later tell police he could not positively identify the gunman and will not be taken to any of the subsequent lineups.

1:10:00 p.m.

The gunman turns right on Jefferson Boulevard, as seen by multiple witnesses. He stuffs the pistol back into his pants, walks briskly west for a block before cutting through a service station and turning north on Crawford Street. At this point the young gunman disappears. (Armstrong, p. 855)

Approximately 1:25 p.m.

“Someone” hands Captain William “Pinky” Westbrook a light tan Eisenhower jacket that was allegedly thrown under a parked car behind the Texaco service station at Jefferson & Crawford. This was supposedly the jacket worn by the fleeing gunman. Westbrook, however, can’t remember the name of the officer who turned over the jacket. (Lane, pp. 200-203)

“Someone” hands Captain William “Pinky” Westbrook a light tan Eisenhower jacket that was allegedly thrown under a parked car behind the Texaco service station at Jefferson & Crawford. This was supposedly the jacket worn by the fleeing gunman. Westbrook, however, can’t remember the name of the officer who turned over the jacket. (Lane, pp. 200-203)

Approximately 1:36 p.m.

As Dallas police cars continue swarming into Oak Cliff, the unidentified young man from 10th & Patton suddenly reappears again on Jefferson Blvd. near the Texas Theater. The man, who is wearing a white shirt, either purchases a ticket or simply ducks in without paying. The time is now approximately 1:37. Once inside, the new arrival goes upstairs to sit in the theater’s balcony section. (Armstrong, pp. 858-60)

Approximately 1:40-42 p.m.

Dallas police are tipped off to a suspicious person who has entered the Texas Theater.

Approximately 1:42 p.m.

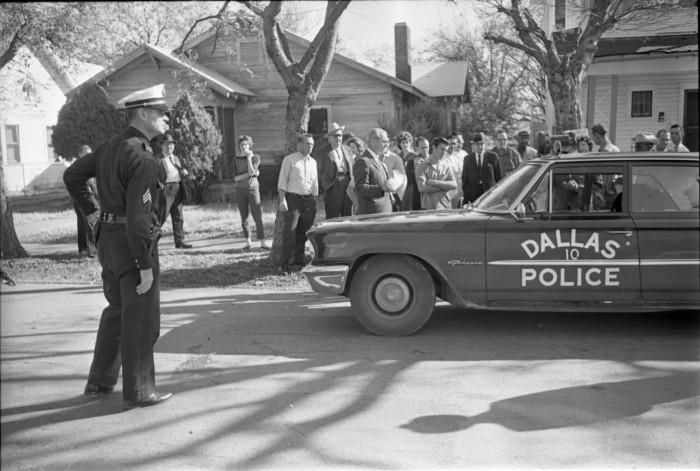

At 10th & Patton, Captain Westbrook of the DPD shows FBI special agent Bob Barrett a man’s wallet. The Dallas investigators are going through the wallet, and apparently find two pieces of ID. Westbrook asks Barrett if he knows who either Lee Harvey Oswald or Alex Hiddell are. Barrett says no. (Armstrong, p. 856) Years later, when the story about the wallet is revealed by FBI personnel, the DPD will say that Barrett’s memory is faulty, there was no wallet found at the Tippit crime scene. But a check of archived Dallas TV news footage proved the DPD wrong. Later, the story seems to change that some unidentified person in the crowd at Tippit’s murder scene must have handed the wallet to reserve cop Sgt. Kenneth Croy, the first officer on site. Only none of the many Tippit witnesses reported seeing a wallet on the ground. Croy, incredibly, never filed a written report on 11/22/63. And Croy, in his testimony before the Warren Commission, said he knew several of the officers who eventually responded to the shooting at 10th and Patton—but couldn’t remember a single name of any of them.

At 10th & Patton, Captain Westbrook of the DPD shows FBI special agent Bob Barrett a man’s wallet. The Dallas investigators are going through the wallet, and apparently find two pieces of ID. Westbrook asks Barrett if he knows who either Lee Harvey Oswald or Alex Hiddell are. Barrett says no. (Armstrong, p. 856) Years later, when the story about the wallet is revealed by FBI personnel, the DPD will say that Barrett’s memory is faulty, there was no wallet found at the Tippit crime scene. But a check of archived Dallas TV news footage proved the DPD wrong. Later, the story seems to change that some unidentified person in the crowd at Tippit’s murder scene must have handed the wallet to reserve cop Sgt. Kenneth Croy, the first officer on site. Only none of the many Tippit witnesses reported seeing a wallet on the ground. Croy, incredibly, never filed a written report on 11/22/63. And Croy, in his testimony before the Warren Commission, said he knew several of the officers who eventually responded to the shooting at 10th and Patton—but couldn’t remember a single name of any of them.

1:45:43 p.m.

The DPD Channel 1 dispatcher broadcasts a report of a suspect who “just went into the Texas Theater.” A fleet of police cars, marked and unmarked, arrive to surround the theater front and back. (Armstrong, p. 863)

1:50-1:51 p.m.

Lee Oswald, still wearing his long-sleeved brown work shirt, is subdued in the main (downstairs) section of the theater by DPD officers and is whisked out the front door to a waiting unmarked police car.(Armstrong, p. 868) Meanwhile, a second slender young white male in a white t-shirt is arrested in the balcony and brought out the back door of the theater, as observed by Bernard Haire, the owner of the hobby store two doors east of the theater. The official Dallas arrest report will indicate that Oswald was arrested in the balcony, while in fact he was actually arrested downstairs in the theater’s ground-floor main section. (Armstrong, p. 871) What happened to the second man who was taken away?

Lee Oswald, still wearing his long-sleeved brown work shirt, is subdued in the main (downstairs) section of the theater by DPD officers and is whisked out the front door to a waiting unmarked police car.(Armstrong, p. 868) Meanwhile, a second slender young white male in a white t-shirt is arrested in the balcony and brought out the back door of the theater, as observed by Bernard Haire, the owner of the hobby store two doors east of the theater. The official Dallas arrest report will indicate that Oswald was arrested in the balcony, while in fact he was actually arrested downstairs in the theater’s ground-floor main section. (Armstrong, p. 871) What happened to the second man who was taken away?

Approximately 1:55 p.m.

While accompanied by four Dallas detectives in an unmarked car headed for DPD’s downtown headquarters, Oswald is asked to give his name. He ignores the request. Perturbed, Detective Paul Bentley pulls a billfold from Oswald’s hip pocket and begins to examine its contents. He finds ID cards for both a Lee Oswald and an A. Hidell. “Who are you?” asks Bentley again. “You’re the detective,” Oswald finally answers back. “You figure it out.” (Armstrong, p. 870)

But wait. They just found Oswald’s wallet at 10th & Patton, right? (Armstrong, p. 868) So Oswald carried two wallets, one of which he was good enough to leave at the Tippit murder scene? Along with four shell casings from a .38 caliber revolver?

In the words of an old Rockford Files TV episode: “that plant was so obvious someone should’ve watered it.” No wonder the 10th & Patton wallet disappeared after a billfold was found to have been in Oswald’s possession at the theater.

The Dallas Police knew who Oswald was before they descended on and surrounded the Texas Theater.

Approximately 2.p.m.

Oswald arrives at Dallas Police Headquarters to be interrogated and booked. He will be shot dead that very same weekend. To quote one bluntly sarcastic journalist: “Lee Oswald miraculously managed to survive nearly 48 hours in the custody of the Dallas Police Department.”

The DPD kept no known tapes or transcripts from the hours of interrogation undergone by their suspect. We have little idea what Oswald really said, only that he “emphatically denied these charges.” (Armstrong, p. 893)

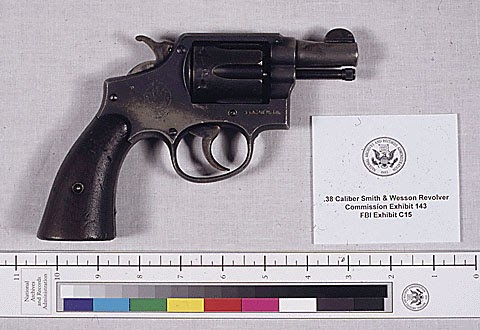

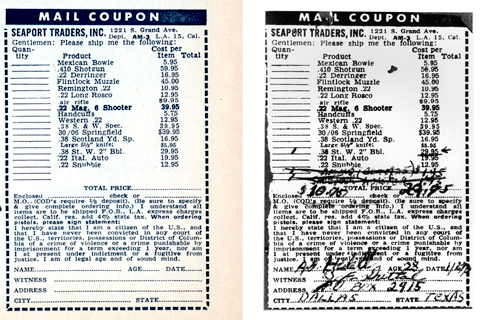

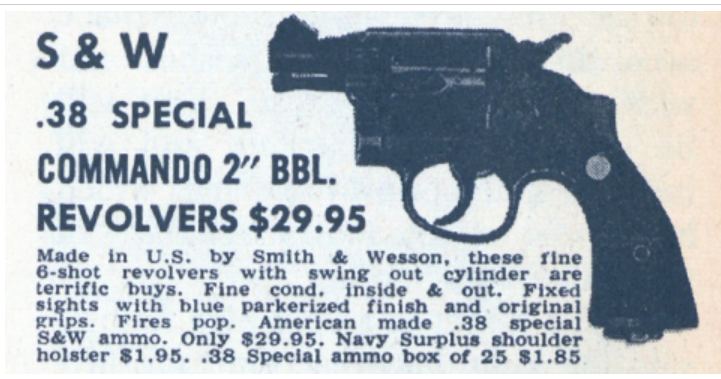

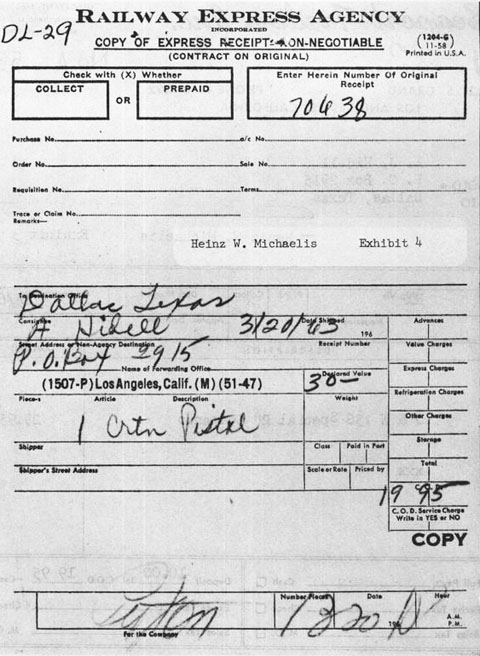

Ballistics

If anyone is looking for ballistics to provide a definitive answer in the Tippit case, they will be sorely disappointed. The ballistics evidence tends to exonerate Lee Oswald as much as it implicates him. (For lengthy discussions of the following, see Henry Hurt, Reasonable Doubt, pp. 151-56 and Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, pp. 252-57)

If anyone is looking for ballistics to provide a definitive answer in the Tippit case, they will be sorely disappointed. The ballistics evidence tends to exonerate Lee Oswald as much as it implicates him. (For lengthy discussions of the following, see Henry Hurt, Reasonable Doubt, pp. 151-56 and Joseph McBride, Into the Nightmare, pp. 252-57)

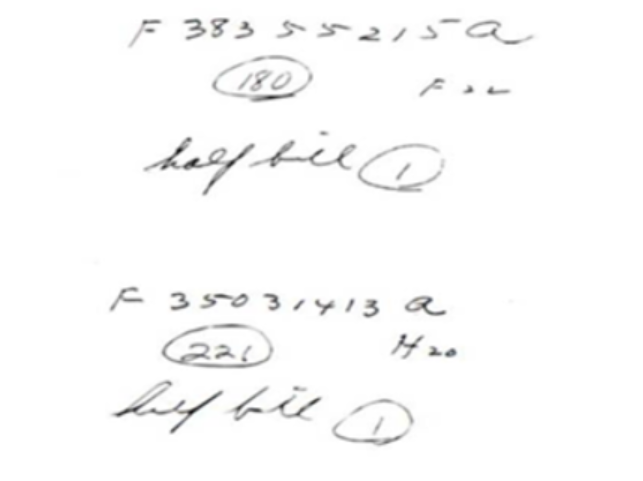

Four shells from a .38 caliber handgun were recovered spread along the ground leading from the crime scene. The DPD officers on site at first figured these were from an automatic pistol (which automatically ejects the spent shells), not a revolver, because who would purposely remove and leave such incriminating evidence at the scene (along with a wallet full of ID)?

The bullets found in Officer Tippit’s body at autopsy could not be matched to Oswald’s .38. And the shells so conveniently recovered at 10th & Patton could not be matched to the bullets. The shells were never properly marked by DPD, evidence was misfiled, and the chain of evidence for the ballistics was, unfortunately, suspect.

In the words of homicide detective Jim Leavelle, the very man tasked with nailing Oswald for the Tippit murder, the ballistics in this case were quite frankly “a mess.”

As Joe McBride notes in his book, Warren Commissioner and congressman Hale Boggs was one of the members of that body who had his doubts about their verdict. Boggs directly challenged the Tippit case ballistics when he said, “What proof do you have that these are the bullets?” (McBride, p. 258) Boggs apparently never received a satisfactory answer.

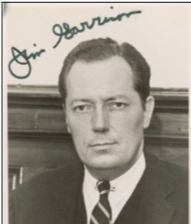

New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison, who took an active role in the JFK assassination investigation in the late 1960s, believed that the ballistics evidence pointed to two shooters at 10th & Patton. Said Garrison in his October 1967 Playboy interview, “The evidence we’ve uncovered leads us to suspect that two men, neither of whom was Oswald, were the real murderers of Tippit.”

Mr. Garrison added that, “… Revolvers don’t eject cartridges and the cartridges left so conveniently on the street didn’t match the bullets in Tippit’s body.”

The cartridge cases—two Western-Winchester and two Remington–Peters—simply didn’t match the bullets—three Western–Winchester, one Remington-Peters—recovered from Officer Tippit’s body.

“The last time I looked,” noted Garrison wryly, “the Remington–Peters Manufacturing Company was not in the habit of slipping Winchester bullets into its cartridges, nor was the Winchester–Western Manufacturing Company putting Remington bullets into its cartridges.”

Witnesses

If the ballistics evidence in the Tippit case could rightly be characterized as messy, then the eyewitness testimony regarding the Tippit homicide would have to be labeled a toxic waste site by comparison.

If the ballistics evidence in the Tippit case could rightly be characterized as messy, then the eyewitness testimony regarding the Tippit homicide would have to be labeled a toxic waste site by comparison.

Tippit authority Joseph McBride, author of Into the Nightmare, explained the bizarre situation succinctly when he stated, “The other physical evidence is also confused and contradictory—and the eyewitness evidence is so contradictory that it seems as though there were two sets of witnesses.” (McBride, pp. 460-61)

One set of witnesses identified Oswald as the sole murderer of Officer Tippit. The second set said they couldn’t positively identify Oswald, or could positively exclude Oswald, and saw two or more suspects acting suspiciously, and even saw one of those persons apparently involved in the shooting escape in an automobile.

Dallas authorities, and later the Warren Commission, focused almost exclusively on the first set of witnesses—while minimizing or completely ignoring the second set.

A good example of “witness neglect” was reported by 10th Street neighbor Frank Wright. Wright later told Tippit researchers that “I was the first person out. I saw a man standing in front of the car. He was looking toward the man on the ground (Tippit). The man who was standing in front of him was about medium height. He had on a long coat, it ended just above his hands. I didn’t see any gun. He ran around on the passenger side of the police car. He ran as fast as he could go, and he got into his car. … He got into that car and he drove away as fast as he could see. … After that a whole lot of police came up. I tried to tell two or three people (officers) what I saw. They didn’t pay any attention. I’ve seen what came out on television and in the newspaper but I know that’s not what happened. I know a man drove off in a grey car. Nothing in the world’s going to change my opinion.” (Hurt, pp. 148-49)

Acquilla Clemons, a caregiver who worked on 10th Street, was not simply ignored the same as was Mr. Wright. Clemons, who saw two suspicious persons escape the Tippit murder scene in different directions, told investigator Mark Lane (during a taped interview) that a man she suspected was a Dallas detective or policeman visited her home on or about 11/24/63. He was carrying a sidearm. Mrs. Clemons reported that the visitor warned her “it’d be best if I didn’t say anything because I might get hurt … someone might hurt me.” (McBride, pp. 490-94)

Acquilla Clemons, a caregiver who worked on 10th Street, was not simply ignored the same as was Mr. Wright. Clemons, who saw two suspicious persons escape the Tippit murder scene in different directions, told investigator Mark Lane (during a taped interview) that a man she suspected was a Dallas detective or policeman visited her home on or about 11/24/63. He was carrying a sidearm. Mrs. Clemons reported that the visitor warned her “it’d be best if I didn’t say anything because I might get hurt … someone might hurt me.” (McBride, pp. 490-94)

Warren Reynolds, a used car salesman who saw the gunman escaping west on Jefferson Boulevard, was indeed hurt—and very badly. Reynolds told news reporters the afternoon of the assassination that he had seen the fleeing gunman, but was simply too far away to have made a positive identification. The FBI finally got around to interviewing Reynolds in January, 1964, at which time the witness reiterated his original story that he had been located across Jefferson Boulevard and was simply too far from the gunman to have made a positive identification. Two nights later, someone sneaked into Reynolds’ place of business, hid in the basement, and shot Mr. Reynolds in the head with a .22 caliber rifle. Miraculously, Reynolds survived. Even more miraculously, the car salesman made such a dramatic recovery that he now found his eyesight had improved and he was able to identify Lee Oswald after all. (Hurt, pp. 147-48; McBride pp. 476-78)

Warren Reynolds, a used car salesman who saw the gunman escaping west on Jefferson Boulevard, was indeed hurt—and very badly. Reynolds told news reporters the afternoon of the assassination that he had seen the fleeing gunman, but was simply too far away to have made a positive identification. The FBI finally got around to interviewing Reynolds in January, 1964, at which time the witness reiterated his original story that he had been located across Jefferson Boulevard and was simply too far from the gunman to have made a positive identification. Two nights later, someone sneaked into Reynolds’ place of business, hid in the basement, and shot Mr. Reynolds in the head with a .22 caliber rifle. Miraculously, Reynolds survived. Even more miraculously, the car salesman made such a dramatic recovery that he now found his eyesight had improved and he was able to identify Lee Oswald after all. (Hurt, pp. 147-48; McBride pp. 476-78)

Decades later, Dallas researcher Michael Brownlow tracked down Mr. Reynolds, who was still in the business of selling cars. At first, Reynolds would not admit who he was. But after Brownlow had gained his trust, the researcher asked Mr. Reynolds why he had suddenly changed his testimony regarding his identification of Oswald.

“Because I wanted to live,” Reynolds admitted bluntly.

When Mark Lane came to Dallas to make the documentary Rush to Judgment, his director, Emile de Antonio, made a rather interesting observation. “There was absolutely no tension at all on the scene of the assassination (Dealey Plaza),” commented de Antonio. “… All the tension is where Tippit was killed. That’s right and this (the Tippit slaying) is the key to it.” (McBride, pp. 460-61)

The director’s sense of what was going on in Oak Cliff was seemingly verified by an anonymous letter appearing in Playboy that was sent to the editor after Jim Garrison’s October 1967 Playboy magazine interview:

“I read Playboy’s Garrison interview with perhaps more interest than most readers. I was an eyewitness to the shooting of policeman Tippit in Dallas on the afternoon President Kennedy was murdered. I saw two men, neither of them resembling the pictures I later saw of Lee Harvey Oswald, shoot Tippit and run off in opposite directions. There were at least half a dozen other people who witnessed this. My wife convinced me that I should say nothing, since there were other eyewitnesses. Her advice and my cowardice undoubtedly have prolonged my life—or at least allowed me now to tell the true story…”

There were four main witnesses who gave testimony that Lee Oswald had in fact been guilty. Many who’ve studied the Tippit murder have long felt that competent defense counsel would have reduced the case against Lee Oswald to shambles. If Oswald had received a fair trial, they say, he would have been exonerated of the charge he killed Officer J.D. Tippit.

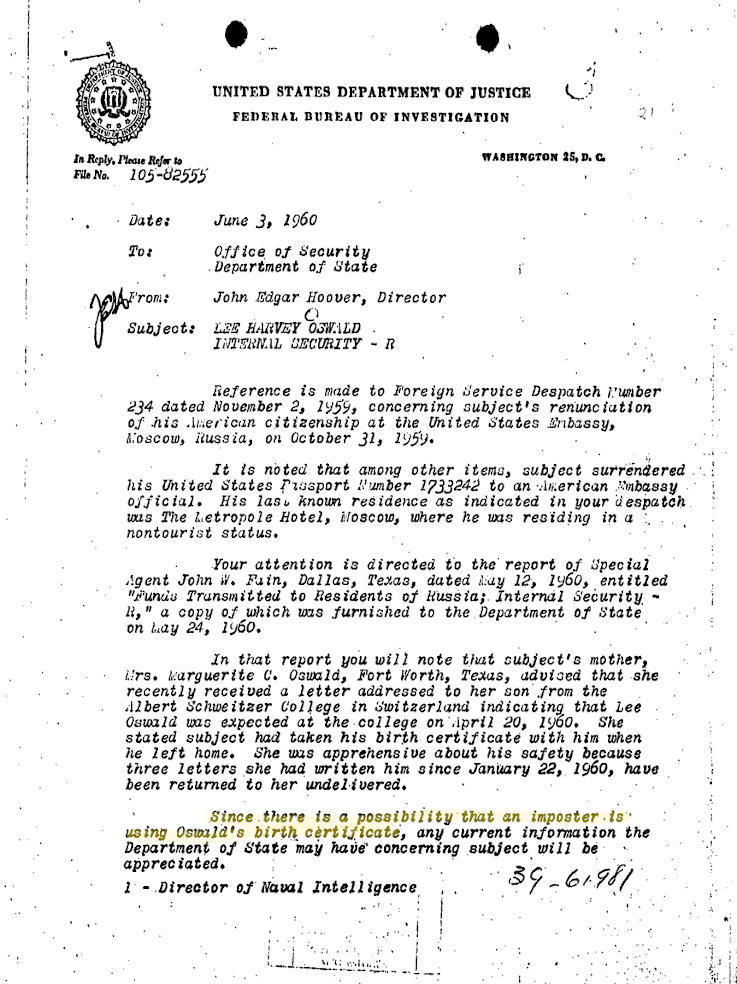

Of course, Oswald did not receive even the benefit of an unfair trial. The suspect received no trial whatsoever and was instead convicted in the court of public opinion based on government propaganda disseminated by a relentless disinformation campaign. In the words of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover on the evening of the assassination, “The thing I am concerned about, and so is Mr. Katzenbach (Deputy U.S. Attorney General), is having something issued so we can convince the public that Oswald is the real assassin.” (McBride, p. 142)

That “thing” mentioned by Hoover would eventually, of course, be the pre-determined, hastily prepared whitewash known as the Warren Report … with the so-called “magic” bullet as its centerpiece.

The four crucial witnesses against Oswald in the fatal Tippit incident would be William Scoggins, Ted Calloway, Helen Markham, and—belatedly—Jack Ray Tatum.

Taxi Driver Bill Scoggins

William “Bill” Scoggins was seated in his cab on Patton Street. (Warren Report, p. 166) He was facing the intersection with 10th Street, when he saw Officer Tippit’s patrol car pass by in front of him. (For discussions of Scoggins’ testimony, from which this material is drawn, see Meagher, pp. 256-57 and Lane, pp. 191-93) He saw no one walk by the front of his cab. The patrol car pulled to the curb on 10th Street approximately 100 feet east of the intersection. Mr. Scoggins’ vantage point was obscured by some bushes at the edge of the corner property on 10th. He suddenly noticed a pedestrian on the 10th Street sidewalk either turn around or walk over to the police car’s passenger side window. Scoggins resumed eating his lunch when, several seconds later, gunshots suddenly rang out. Scoggins, startled, looked up in time to see the officer fall into the street. Soon after the pedestrian, now brandishing a pistol, began walking in the direction of the cab. Scoggins exited his cab, thought about running away, but immediately realized he would be in the open and could not outrun any bullets. Instead, Scoggins opted to hide behind the driver-side fender of his cab. He saw the young man cut across the lawn on the corner property, squeezing through the bushes and stepping out onto the sidewalk very near the cab. Hunkered down by the fender, Scoggins heard the man mumble something like “Poor dumb cop.” He was afraid the gunman might try to steal the cab, but instead the young man proceeded on foot south on Patton towards Jefferson Blvd., crossing Patton at mid-block.

William “Bill” Scoggins was seated in his cab on Patton Street. (Warren Report, p. 166) He was facing the intersection with 10th Street, when he saw Officer Tippit’s patrol car pass by in front of him. (For discussions of Scoggins’ testimony, from which this material is drawn, see Meagher, pp. 256-57 and Lane, pp. 191-93) He saw no one walk by the front of his cab. The patrol car pulled to the curb on 10th Street approximately 100 feet east of the intersection. Mr. Scoggins’ vantage point was obscured by some bushes at the edge of the corner property on 10th. He suddenly noticed a pedestrian on the 10th Street sidewalk either turn around or walk over to the police car’s passenger side window. Scoggins resumed eating his lunch when, several seconds later, gunshots suddenly rang out. Scoggins, startled, looked up in time to see the officer fall into the street. Soon after the pedestrian, now brandishing a pistol, began walking in the direction of the cab. Scoggins exited his cab, thought about running away, but immediately realized he would be in the open and could not outrun any bullets. Instead, Scoggins opted to hide behind the driver-side fender of his cab. He saw the young man cut across the lawn on the corner property, squeezing through the bushes and stepping out onto the sidewalk very near the cab. Hunkered down by the fender, Scoggins heard the man mumble something like “Poor dumb cop.” He was afraid the gunman might try to steal the cab, but instead the young man proceeded on foot south on Patton towards Jefferson Blvd., crossing Patton at mid-block.

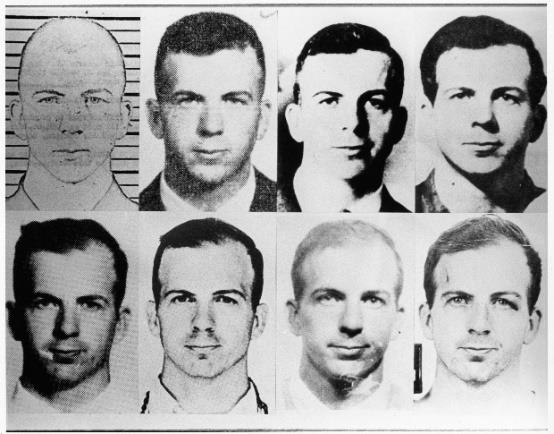

At the Saturday (next day) six-man police lineup, Mr. Scoggins picked Oswald as the individual he had briefly seen emerging from the bushes. However, fellow car driver William Whaley, who had driven Oswald from downtown Dallas to Oak Cliff the previous day, also attended the same lineup as Scoggins. Mr. Whaley made the following cogent observation regarding the nature of that DPD lineup. He testified before the Warren Commission that “… you could have picked him (Oswald) out without identifying him by just listening to him, because he was bawling out the policeman, telling them it wasn’t right to put him in line with these teenagers. … He showed no respect for the policemen, he told them what he thought about them. They knew what they were doing and they were trying to railroad him and he wanted his lawyer.”

Oswald, of course, had a visibly damaged eye, the result of his encounter with the DPD. Oswald was also asked to state his name and to tell where he worked. By Saturday, when Mr. Scoggins participated in this particular lineup, every functioning adult in Dallas and across the USA knew that the lead suspect in the assassination of JFK and the murder of Officer Tippit was a young man named Lee Harvey Oswald who worked at the Texas School Book Depository.

As Mr. Whaley duly noted, “you could have picked him out without identifying him.”

Mr. Scoggins, as it turns out, was actually not able to pick out Oswald during a separate photo lineup. In front of the Warren Commission, Scoggins said that he was shown photos of different men by either an FBI or Secret Service agent. “I think I picked the wrong one,” the cab driver testified. “He told me the other one was Oswald.”

It seems abundantly clear that Mr. Scoggins got only the briefest of glimpses of the gunman, while hiding in fear for his life on the opposite side of his cab. He was unable to identify Lee Oswald as the gunman in the absence of a highly tainted lineup.

And fellow cab driver William Whaley, who saw through the sham of these tainted DPD lineups and denounced them for what they were? Within two years of his Warren Commission testimony he would become the first Dallas taxi driver since 1937, while on duty, to fall victim to a fatal traffic accident.

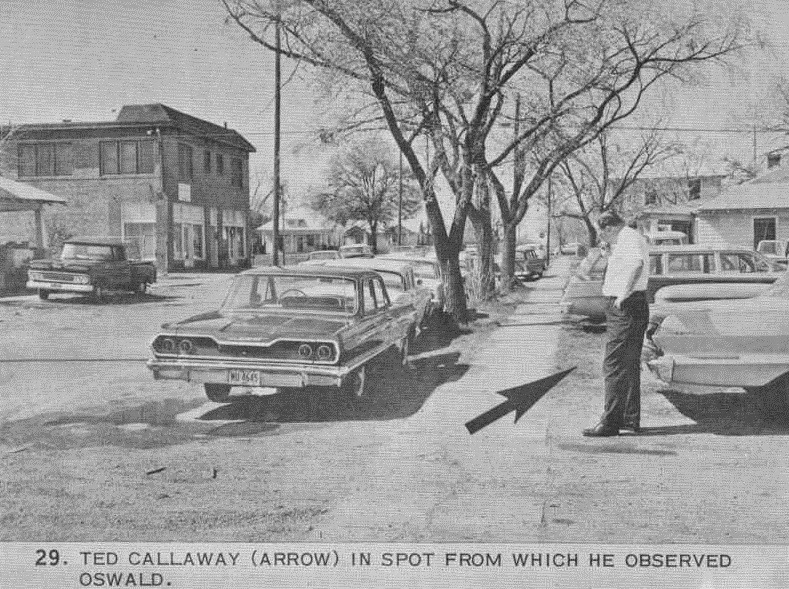

Ted Calloway

After the Tippit gunman passed Bill Scoggins’s cab on Patton Street, he soon encountered used car lot manager Ted Calloway. Calloway, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, had heard the pistol shots and immediately began walking across the car lot towards Patton to investigate. (Warren Report, p. 169) He soon observed a young man heading south on Patton carrying a pistol in what Calloway would later describe as a “raised pistol position.” The young gunman, who noticed Calloway approach the east sidewalk on Patton, then crossed to the west side of the street to avoid the car salesman. (This following material is referenced in Meagher, p. 258 and Mc Bride, pp. 469-70)

After the Tippit gunman passed Bill Scoggins’s cab on Patton Street, he soon encountered used car lot manager Ted Calloway. Calloway, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, had heard the pistol shots and immediately began walking across the car lot towards Patton to investigate. (Warren Report, p. 169) He soon observed a young man heading south on Patton carrying a pistol in what Calloway would later describe as a “raised pistol position.” The young gunman, who noticed Calloway approach the east sidewalk on Patton, then crossed to the west side of the street to avoid the car salesman. (This following material is referenced in Meagher, p. 258 and Mc Bride, pp. 469-70)

“Hey, man!” yelled Calloway as the suspect passed Calloway’s position. “What the hell’s going on?” The man glanced at Calloway, said something unintelligible, then continued past Mr. Calloway and towards Jefferson Boulevard, where he turned west and was soon out of sight.

“Follow that guy,” Calloway instructed two nearby car lot employees. Calloway then hurried up to 10th Street where he saw a small crowd forming around Tippit’s prone body. Calloway next picked up the dead policeman’s handgun and told Bill Scoggins they would use Scoggins’ yellow cab to go hunt for the gunman.

“Which way did he go?” Calloway asked Domingo Benavides, who had stopped his pickup truck only 15-20 feet from Tippit’s patrol car when he heard the gunshots. Is this not a strange question to be asked by a witness who had purportedly just seen the gunman fleeing by him on Patton Street?

Calloway and Scoggins did indeed briefly search the neighborhood, although unsuccessfully, for Tippit’s killer. The FBI would later determine that Mr. Calloway had seen the gunman from a distance of 55-60 feet. Not nearly as close as Bill Scoggins, but Calloway had gotten a longer, clearer look.

Calloway, a thoroughly believable, extroverted, and likeable individual, would have made an excellent witness for the prosecution. Calloway positively identified Oswald at one of the tainted DPD lineups and later told the Warren Commission how he saw Lee Harvey Oswald escaping from the scene of the crime at 10th & Patton.

But a funny thing happened in 1986 when a television special was produced from London, On Trial: Lee Harvey Oswald. This was a mock trial featuring prosecutor Vince Bugliosi and high-profile defense attorney Gerry Spence. Spence had the difficult assignment of defending the man widely accepted to be JFK’s assassin, Lee Oswald. When Ted Calloway took the stand, he was his usual affable, loquacious self. He told the courtroom that he was 100% confident that the man he saw carrying a pistol that day was Lee Harvey Oswald.

When Spence asked Calloway whether it was fair that Oswald was in the lineup with a bruised eye and cuts on his face and was not dressed in a shirt and tie like others beside him, Mr. Calloway said he didn’t think it mattered.

When Spence asked Calloway whether Homicide Detective Jim Leavelle had prejudiced Oswald’s identification by telling Calloway that, “We want to try to wrap him up tight on the killing of this officer. We think he is the same one that shot the President. But if we can wrap him up real tight on killing this officer, we have got him.” Would that not be pressuring the witness?

Ted Calloway, however, did not believe Leavelle’s statement to have been prejudicial, because the car salesman said Leavelle also told Calloway and the others to “be sure to take your time.”

With Calloway refusing to admit he could have been mistaken or pressured in any way by police to make a positive ID, Spence had one final trick up his sleeve. The flamboyant defense attorney must have been a gambling man, because he was certainly gambling on his next move—but it worked.

Spence’s final question for witness Ted Calloway was to ask him if he could identify someone in a particular photo. This was the infamous and controversial “Doorman” photo taken by a newsman the moment the shots rang out in Dealey Plaza. Some have speculated that the figure of this man in the doorway of the TSBD could have been Lee Oswald. It wasn’t. All evidence instead points to this man having been Billy Lovelady, a lookalike co-worker of Oswald’s at the depository.

Spence’s final question for witness Ted Calloway was to ask him if he could identify someone in a particular photo. This was the infamous and controversial “Doorman” photo taken by a newsman the moment the shots rang out in Dealey Plaza. Some have speculated that the figure of this man in the doorway of the TSBD could have been Lee Oswald. It wasn’t. All evidence instead points to this man having been Billy Lovelady, a lookalike co-worker of Oswald’s at the depository.

Calloway, mildly confused by the question and suspecting Spence was laying some sort of trap, nevertheless replied that the image being shown on the courtroom screen was “a likeness of Oswald.”

But it wasn’t and that was just the point. At a distance of 55-60 feet, Ted Calloway could have easily mistaken Billy Lovelady (and a lot of other young, white males) for Lee Oswald. It is exactly this sort of testimony by a witness who is so “100% positive” that has led to innocent persons finding themselves on death row.

Waitress Helen Markham

Mrs. Helen Markham was the so-called “star” witness of the Warren Commission regarding the murder of J.D. Tippit. Mrs. Markham was the only witness in 1963 who claimed to have actually seen Lee Oswald shoot and kill Officer Tippit. Markham was hurrying to catch a bus downtown to her waitressing job when she, according to her version of events, came upon the scene of Oswald shooting Tippit from across the hood of Tippit’s patrol car. (Warren Report, pp. 167-68)

The problem with Markham’s eyewitness testimony is that she maintained she saw many things that no other witnesses saw—things that not only did not happen, but that could not have happened.

The problem with Markham’s eyewitness testimony is that she maintained she saw many things that no other witnesses saw—things that not only did not happen, but that could not have happened.

Markham’s testimony was considered worthless by several of the lawyers who worked for the Warren Commission. Some even considered it downright dangerous and lobbied to have Markham excluded as a witness. (Edward Epstein, The Assassination Chronicles, pp. 142-44) But the higher-ups on the commission realized that without Markham, without at least one supposed eyewitness, the already glaringly weak case against Oswald for the murder of Officer Tippit would potentially collapse. The lawyers were stuck with her. The commission deemed Markham to be a “reliable” witness, despite all evidence to the contrary. “She is an utter screwball,” stated Joseph Ball, senior counsel to the Warren Commission. He characterized her testimony as being “full of mistakes” and that it was “utterly unreliable.” (Anthony Summers, Conspiracy, p. 87)

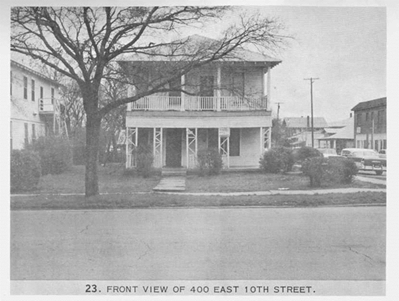

According to Mrs. Markham’s version of events, she was hurrying to catch a bus to work, walking south on Patton Street towards Jefferson Boulevard. (The major part of her testimony is located in Warren Commission Vol. III, pp. 306-22)

As she approached 10th Street and was waiting for traffic to pass, Markham observed a young man crossing Patton in front of her on the opposite side of 10th Street, As the man continued walking east on 10th, a police car approached from the same direction, rolling slowly through the intersection a few seconds later. The man kept walking, and the police car kept moving slowly forward. Eventually, the patrol car pulled curbside and the officer called or motioned to the young man to approach his patrol car. The man came over and leaned in the open window on the passenger side, talking to the officer. The conversation seemed “friendly” and Markham paid it “no mind.” After several seconds, the policeman got out of his car and began to walk towards the front of his car. The young man stepped back, put his hands to his sides, and also began walking towards the front of Officer Tippit’s patrol car.

When the policeman and the pedestrian passed the windshield and were opposite each other over the hood of the car, the man pulled out a pistol and shot Officer Tippit “in the wink of your eye.”

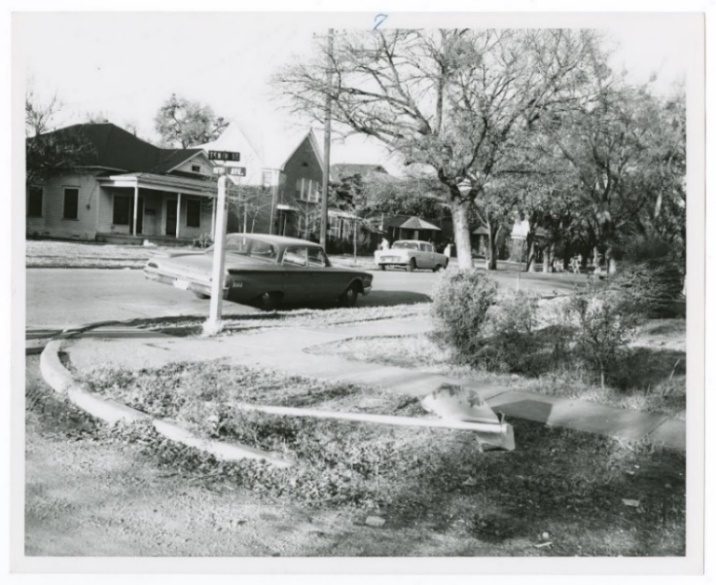

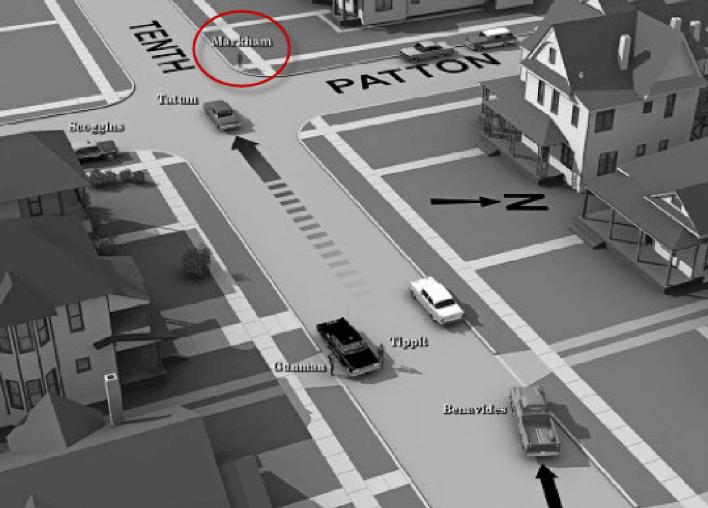

The gunman then turned and began walking west back to where he had come from. As he was reaching the corner of 10th & Patton again he looked across the intersection and saw Mrs. Markham. Their eyes locked. Mrs. Markham screamed and put her hands over her face. She did so for several seconds. When she began to pull her fingers down to peek, she watched the man escaping the scene by walking across a lot and then disappearing down the alleyway that runs between 10th Street and Jefferson Boulevard. Here is a graphic of the crime scene from Tippit author Dale Myers:

I have taken the liberty of slightly altering this graphic by putting a circle around Mrs. Markham’s reported position. The graphic is from Mr.Myers’ book, With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J. D. Tippit.

I have taken the liberty of slightly altering this graphic by putting a circle around Mrs. Markham’s reported position. The graphic is from Mr.Myers’ book, With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J. D. Tippit.

After the gunman had disappeared down the alley, Mrs. Markham went to the policeman’s side. The injured officer tried speaking to Mrs., Markham, but she could understand little if anything he said. Mrs. Markham stayed with the policeman, alone in the middle of 10th Street, for almost 20 minutes. Then some people finally came by, and eventually some police too, and then the ambulance. She spoke with the officer until they loaded him into the ambulance and left for the hospital.

The problems with Mrs. Markham’s story are many:

- The gunman, according to the other witnesses, had been walking west on 10th Street, not east as stated by Mrs. Markham. The official Dallas Police report describes the suspect as walking west.

- The passenger side window on Tippit’s patrol car had been rolled up. The gunman could not have leaned inside the window and rested his elbows and arms on the door as described by Mrs. Markham.

- All other witnesses saw the gunman flee west on Jefferson Boulevard. No one else saw the gunman go across an empty lot and disappear down the alley.

- All witnesses and the Dallas County coroner said that Officer Tippit was almost certainly dead when he hit the ground. It was not possible for the dead officer to have held any conversation with Mrs. Markham.

- A crowd formed at that scene very quickly and grew larger with each passing minute. Mrs. Markham’s assertion that she was alone in the street with Tippit for nearly 20 minutes was simply inconceivable. The ambulance came from two blocks away and retrieved Tippit’s body in probably five minutes or less. (For a good review of the problems with Markham, see McBride, pp 478-82)

Mrs. Markham would describe the gunman as being a little bit chunky and with somewhat bushy hair. Lee Oswald had thinning hair—and at 5’9” and 130 pounds could hardly have been described as being even a “little” chunky.

At the downtown police lineup, Mrs. Markham became hysterical and there was some discussion about bringing her to the hospital for medical attention. She was able to continue with the lineup only after someone kindly administered some ammonia to revive her and settle the poor woman’s frazzled nerves.

Markham was able to pick Oswald out at the lineup … not because she recognized him as the gunman, but because she said that when she looked at the “number two man” in the lineup, his appearance gave her chills. Perhaps this may be explained by the fact that, while Oswald stood in that lineup next to well-dressed Dallas police detectives using fictitious names, his face looked as if he had done a few rounds with then reigning heavyweight boxing champion Sonny Liston.

“When I saw this man, I wasn’t sure but I had cold chills run all over me,” was Mrs. Markham’s description to the Warren Commission of her so-called “identification” of the suspect. This, mind you, from their “star” witness.

No less than a half dozen times did Mrs. Markham attempt to explain to the Warren Commission that she did not know any of the men in the lineup and did not recognize any of them either. But Assistant Counsel Joseph Ball refused to settle for this: “Was there a number two man in there?” Ball asked Markham, a rather leading question posed to this witness, one that would have been immediately objected to by any competent defense attorney at a jury trial. Finally, Mrs. Markham was forced to concede that “the number two man is the one I picked.” Not because she recognized the man, but because he gave her chills. (McBride, p. 479)

“Contradictory and worthless” was the description given by Assistant Warren Counsel Wesley Libeler regarding Mrs. Markham’s testimony. “The Commission wants to believe Mrs. Markham and that’s all there is to it,” added staff member Norman Redlich. (McBride, p. 479)

Remember, these were the folks putting their careers on the line and being paid to “wrap him up tight”—not to exonerate the apparent sole suspect of these monumental crimes.

Jim Garrison, in On the Trail of the Assassins, commented dryly that, “As I read Markham’s testimony, it occurred to me that few prosecutors had ever found themselves with a witness at once so eager to serve their cause and simultaneously so destructive to it.” (Garrison, p. 195) Garrison may have been onto something here. What was causing this lady’s testimony to be so strangely bizarre and baffling?

Jim Garrison, in On the Trail of the Assassins, commented dryly that, “As I read Markham’s testimony, it occurred to me that few prosecutors had ever found themselves with a witness at once so eager to serve their cause and simultaneously so destructive to it.” (Garrison, p. 195) Garrison may have been onto something here. What was causing this lady’s testimony to be so strangely bizarre and baffling?

Tippit researchers Joseph McBride, William Pulte, and Michael Brownlow have all hinted at a potential answer. At the time of the JFK assassination and J.D. Tippit’s death, Helen Markham’s son, Jimmy, was facing serious criminal charges in Dallas County. Markham, a single mother of very limited means, could do little in the way of protecting her troubled, at-risk boy. Then, suddenly, the Tippit incident occurred and Mrs. Markham was, in her words, “treated like a queen” by Dallas Police. It must have crossed Helen Markham’s mind that, if she helped the police and the Dallas authorities, her son might receive favorable treatment by the court. Worse, if she refused to help and did not identify Oswald as Tippit’s killer, it might be her son who paid the heavy, immediate price. (McBride, p. 479) But helping Dallas authorities, in this particular highest of profile cases, meant having to finger an innocent man, whether dead or not, for a crime he did not commit. Oswald was simply not the short, slightly heavy, bushy-haired cop-killer who disappeared behind Ballew’s Texaco.

So, it may have been Mrs. Markham’s solution to this conundrum to appear to be helping the authorities while she was actually rendering her testimony useless and therefore harmless to the defendant. Save son Jimmy, but also protect Lee, the young man who was in the Texas Theater as the fatal shots rang out at 10th & Patton.

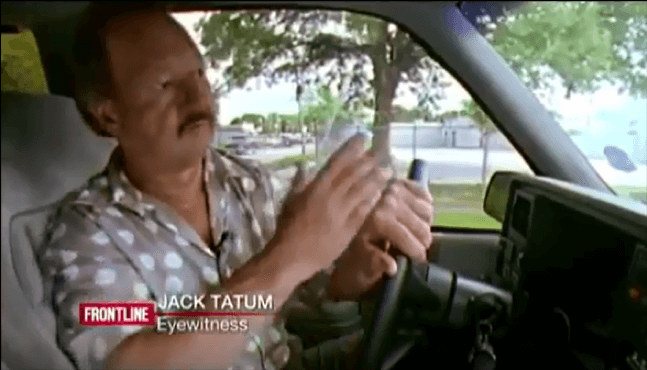

Medical Photographer Jack Ray Tatum

Witness Domingo Benavides, the closest passerby to the shooting of Officer Tippit, was unable to make a positive ID of the suspect, because Benavides had instinctively ducked down behind the dashboard of his pickup truck when he heard the shots. Benavides mostly saw the gunman as he was walking away, towards the corner of 10th & Patton, while tossing shell casings into bushes along the way. Benavides did report that the gunman had a haircut that was squared off in the back along the neckline of his Eisenhower jacket. Lee Oswald on that day clearly had hair that was tapered in back, not squared off. (WC, Vol 6, p. 451)

Witness Domingo Benavides, the closest passerby to the shooting of Officer Tippit, was unable to make a positive ID of the suspect, because Benavides had instinctively ducked down behind the dashboard of his pickup truck when he heard the shots. Benavides mostly saw the gunman as he was walking away, towards the corner of 10th & Patton, while tossing shell casings into bushes along the way. Benavides did report that the gunman had a haircut that was squared off in the back along the neckline of his Eisenhower jacket. Lee Oswald on that day clearly had hair that was tapered in back, not squared off. (WC, Vol 6, p. 451)

Benavides also noticed something else that would later prove significant—a red Ford Galaxie about six car lengths ahead of his pickup, going west, that pulled over same as Benavides when the shots occurred. (HSCA Vol 12, p. 40) The red Galaxie and its driver supposedly stopped and stayed at the scene for a time—and then left as a crowd quickly gathered. No one ever got the name of this potential important witness.

In September, 1976 the U.S. House of Representatives voted 280-65 to establish the Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA), in order to investigate the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. This bold move was primarily caused by the first national airing in March of 1975 of the 8 mm film shot by Abraham Zapruder of the JFK assassination. Geraldo Rivera hosted the showing which took place on the ABC show Good Night America. When American citizens finally got to witness the shooting with their own eyes, their response was one of outrage, which in turn prompted the reopening of the investigation. The HSCA would not complete its work until late in 1978 and did not issue a final report and conclusion until the following year, 1979. The final conclusion of the HSCA was that President Kennedy had likely been assassinated as the result of a conspiracy.

A reopening of the JFK assassination necessarily meant the HSCA would also be taking a second look at the Tippit murder. The case against Lee Oswald in the murder of Officer Tippit had been a house of cards from the beginning and there were those in positions of power who apparently did not wish for any second inquiry of the murky, little-investigated events at 10th & Patton on the day of JFK’s assassination.

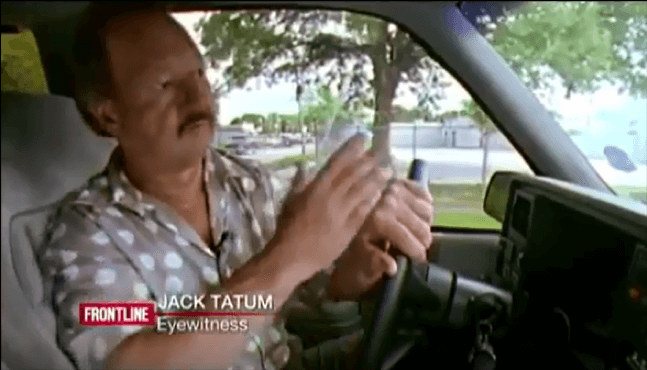

It was against this backdrop that a Dallas native, Jack Ray Tatum, stepped forward with the claim that he had been the driver behind the wheel of the mysterious red Ford Galaxie seen stopped near the intersection of 10th & Patton on 11/22/63.

Mr. Tatum would proceed to tell an amazing story—perhaps one even more unbelievable than that of the unfortunate Mrs. Markham. Yet unlike that of the much-maligned waitress, it has generally, and inexplicably, been accepted as fact for more than four decades. In a filmed interview with the PBS television show Frontline in 2003, Mr. Tatum re-created his alleged experience on that fateful day in Dallas, 1963.

While taking a detour through the neighborhood to circle back to a jewelry store on Jefferson Blvd. to buy his wife a gift, Tatum said he found himself driving north on Denver Street around 1 p.m. at which time he turned left to head west on 10th Street.

Tatum explained that after he made the turn and began driving west on 10th, he noticed an individual walking in his direction (walking east towards Tatum). A Dallas police car was just pulling over to the curb. As Tatum drove towards where the squad car was now parked he noticed the young man leaning over and talking to the officer. The man had both hands in the pockets of his light-colored tan jacket. Tatum continued on to the intersection of 10th & Patton. As he was about in the middle of that intersection he heard “three, maybe four shots.” Tatum continued through the intersection and then braked to a stop.

Tatum explained that after he made the turn and began driving west on 10th, he noticed an individual walking in his direction (walking east towards Tatum). A Dallas police car was just pulling over to the curb. As Tatum drove towards where the squad car was now parked he noticed the young man leaning over and talking to the officer. The man had both hands in the pockets of his light-colored tan jacket. Tatum continued on to the intersection of 10th & Patton. As he was about in the middle of that intersection he heard “three, maybe four shots.” Tatum continued through the intersection and then braked to a stop.

What Tatum describes next was seen by no other witnesses.

Tatum looked in his rearview mirror and saw the policeman laying in the street. The gunman, still on the passenger side of the squad car, walked to the rear of Tippit’s car, hesitated, came around the back of the car, then walked up along the driver’s side of the car … and shot Tippit one final time at close range. (McBride, p. 496)

The gunman, according to Tatum, then looked around, surveyed the situation, and started a slow run west in Tatum’s direction. Tatum put his car in gear, drove forward down 10th Street to avoid danger, and kept his eye on the gunman in the rearview mirror.

Tatum said he could see the gunman very clearly and that the corners of his mouth curled up, like in a smile, which was distinctive and made this individual stand out. Then, Tatum delivers his punch line, the big money words the PBS audience is waiting for:

“And I was within 10-15 feet of that individual and it was Lee Harvey Oswald.”

Now, to the casual viewer of this PBS documentary, Mr. Tatum has just laid to rest any and all the conspiracy theories surrounding the murder of J.D. Tippit—and has apparently put the final nail in the coffin of Lee Harvey Oswald. Tatum is so smooth in his delivery, so convincing, so sincere: 10-15 feet? How could he have not identified Oswald?

Frontline and PBS should be ashamed for having filmed this charade and then presenting it to the American public as fact. (The reader can see this interview at Youtube, under the title, “J. D. Tippit Murder Witness Jack Tatum”) Since the entire interview was shot from within Tatum’s vehicle, the viewer can’t see that, according to Tatum’s own description of events, the gunman was likely never closer than 100 feet of Mr. Tatum’s alleged position (in red). Here is the overhead satellite view of that intersection today, with the distance legend in the lower right corner (blue arrow points to 20 ft.):

According to a study cited by the Innocence Project, after 25 feet face perception diminishes. At about 150 feet, accurate face identification for people with normal vision drops to zero.

According to a study cited by the Innocence Project, after 25 feet face perception diminishes. At about 150 feet, accurate face identification for people with normal vision drops to zero.

Could Jack Tatum, while watching a fleeing gunman in his rearview mirror from 100 feet or more away (and remember, Tatum said he drove forward again as the gunman approached), have been able to tell that the corners of the gunman’s mouth turned up? Positively ID him as Lee Harvey Oswald? A gunman in a rearview mirror who was ducking behind trees, bushes, Mr. Scoggins’ yellow cab, and all the while brandishing a pistol?

Could Jack Tatum, while watching a fleeing gunman in his rearview mirror from 100 feet or more away (and remember, Tatum said he drove forward again as the gunman approached), have been able to tell that the corners of the gunman’s mouth turned up? Positively ID him as Lee Harvey Oswald? A gunman in a rearview mirror who was ducking behind trees, bushes, Mr. Scoggins’ yellow cab, and all the while brandishing a pistol?

Was Jack Ray Tatum even there? Who says so besides Jack Ray Tatum? Tatum himself admitted that “When they were getting witnesses to go to the Warren Commission, I thought, they hadn’t missed me—no one had mentioned I was there.”

Tatum later claimed he didn’t want to get involved on 11/22/63, that they already had enough witnesses. (McBride, p. 498) And that Mrs. Markham—who Tatum said was there—(with her hands over her eyes) got a better look than he.

Oh, yes, Mrs. Markham. Tatum first said he simply drove away and left the scene of the Tippit slaying. Later he explained that he came back to help poor Mrs. Markham, eventually driving her to a police station to give her statement. A noble gesture to be sure. Only problem is, DPD records indicate that Mrs. Markham was taken to DPD headquarters by Office George Hammer, not Mr. Tatum.

Tatum’s assertion that “Oswald” came within 10-15 feet of him may be an exaggeration of colossal proportion. However, Tatum’s other claim that “Oswald” circled the squad car and then shot Tippit—basically point blank “execution style”—is as absurd as anything Mrs. Markham told the Warren Commission in 1964. Yes, the eyewitness testimony in general was both conflicting and contradictory. Yes, Benavides and Scoggins missed witnessing crucial pieces of the crime as they went ducking for cover. And we can only guess at what Mrs. Markham actually saw. But while the eyewitness testimony may have been difficult if not impossible to reconcile, the ear witness testimony remained extremely consistent.

Witness after witness described Tippit as being killed by a fusillade of shots. They all heard basically the same thing: Pow pow pow pow.

“They was fast,” remarked cabdriver Bill Scoggins, describing how the shots were fired extremely close together, in rapid succession.

“Pow pow, pow pow,” is how neighbor Doris Holan, whose second-floor apartment overlooked the scene, described the loud bangs to researcher Michael Brownlow.

“He shot him in the wink of your eye,” noted Mrs. Markham.

Domingo Benavides described hearing a loud boom followed quickly by two more fast booms.

“Bam bam – bam bam bam,” remarked Ted Calloway, likening the shot sequence to Morse code.

Yet Mr. Tatum insisted that “Oswald” fired 3-4 shots from the front passenger side, stopped, walked to the back of the patrol car, hesitated, then walked behind the squad car, turned, and walked up the driver’s side until he stood over Tippit and fired one last bullet up-close-and-personal.

Except, no one heard that. No one heard anything even remotely resembling that. Nobody heard shots—followed by a several second delay—followed by one final shot.

Yet today, if you watch a documentary, movie, or television show describing Tippit’s murder, Jack Tatum’s version of events is what you are almost sure to see. But it never happened that way, couldn’t have happened that way.

Yet today, if you watch a documentary, movie, or television show describing Tippit’s murder, Jack Tatum’s version of events is what you are almost sure to see. But it never happened that way, couldn’t have happened that way.

“That just didn’t happen,” Calloway told one researcher regarding Tatum’s scenario. “Boy, those shots are as clear in my ear today as the day it happened. Bam. Bam. Bam, bam, bam. Just like that.”

Problem is, the forensic evidence showed that one of the shots was likely fired from a steep downward angle, from above the officer, unlike the other three shots. The final shot was more accurate, more deadly, and apparently done from a much closer distance.

But the man in the light tan Eisenhower jacket didn’t have time to do what Mr. Tatum said he did. After the shots, he began almost immediately to walk in the direction of Bill Scoggins’ cab. That gunman never went around the car and stood over Tippit. Again, there was no time for that. And nobody heard that.

Someone else was there. Someone else who also shot Tippit but escaped before the man in the light tan Eisenhower jacket started dropping shells and walking towards Patton Street. Someone such as the man in the long coat seen by Mr. Wright. The man who looked down at Tippit in the street and then ran fast to a grey 1950 or 1951 coupe and sped away.

“Those are pistol shots!” exclaimed Mr. Calloway when the murder happened. With that the used car manager was on his feet and out the office door. “I could move,” he recalled, “and just as I got to the sidewalk—which is about thirty-feet away, I guess—I looked to my right and there’s Oswald jumping through the hedge.”

Calloway was asked, “If someone tried to convince you that there were four shots and a short pause and then another one fired, you wouldn’t believe that?” “No, I wouldn’t,” Calloway answered, repeating the cadence he recalled, “Bam–bam–bam, bam, bam.”

No time, no how, no way.

So what was accomplished by Jack Tatum’s strange, belated testimony before the HSCA?

- It helped to repair Mrs. Markham’s highly controversial and highly criticized testimony before the Warren Commission in 1964—and helped to verify her presence (doubted by some) at that corner when the shots were fired.

- It reinforced the idea that the gunman had been walking east, not west, a crucial detail needed to allow Lee Oswald to have reached the scene in time to murder Officer Tippit.

- It explained the previously unexplainable, the forensic evidence that showed Tippit had been hit by one bullet from a different, much steeper angle which was also fired from a distance relatively closer than the other bullets.

- It maintained the fiction of only one gunman at the Tippit scene.

- It fingered Lee Oswald as that lone gunman at the Tippit scene.

- Most of all, it gave the HSCA a reason not to delve too deeply into the Tippit case. Which, in retrospect, is one of the HSCA’s many failures: their lack of rigor in reviewing the Tippit case.

Today, under analysis, his testimony has the quality of paper mache. Tatum saw things no one else saw and heard things no one else heard. And his identification of Oswald simply has little or no credibility from that distance. His alleged escorting of Markham is also dubious. It’s almost as if he was a salesman. The ruse, a highly pernicious one, has apparently succeeded—at least so far. Yet, in spite of all this—and because of late Frontline producer Mike Sullivan—his twist on critical events is continually presented as fact.

In the end, however, the HSCA still managed to “overturn” the 1964 pre-determined conclusion offered by the Warren Commission. The HSCA reported that President Kennedy was probably slain as the result of a conspiracy, and that there were likely at least two gunmen in Dealey Plaza—both in the Texas School Book Depository and behind the fence on the Grassy Knoll.

And so now at the end of this article, we have finally come full circle … back to Counsel David Bellin’s “Rosetta Stone” logic. For if President Kennedy was assassinated in downtown Dallas as a result of a conspiracy, then it follows that Officer Tippit was likely murdered in adjoining Oak Cliff in an attempt to further that same conspiracy. 10th and Patton was a setup, the disturbance at 10th was in all likelihood a ruse. The designated patsy sat in a darkened nearby movie theater as Officer Tippit, drawn into a trap, was shot down on a quiet residential street in a Dallas suburb. All went as planned—until the scheme to kill the patsy in the movie theater fell through. That’s when the conspirators, suddenly desperate, went into all-out damage control mode and brought in Mafia bag man Jack Ruby to silence the pasty once-and-for all—live and in front of a national television audience.

Messy, very messy.

And in the words of Tippit author Joseph McBride, America then took a turn and walked into the nightmare. Along the way, they turned a former Marine into a patsy.

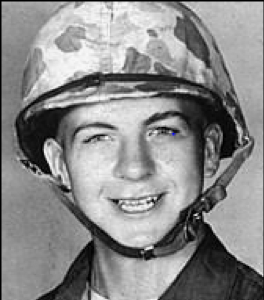

While in the Marines, Oswald was following orders when he studied Russian and sat for Russian proficiency exams. When ready for his first big intelligence assignment, Oswald took a hardship discharge — ostensibly to take care of his mother in Fort Worth, TX — but left almost immediately for Europe to participate in the United States’ fake defector program. The Soviets never bought Oswald’s defector act. The KGB had Lee shipped him off to toil in a radio factory in Minsk where he could be kept under close surveillance, do little harm, and be used for propaganda purposes.

While in the Marines, Oswald was following orders when he studied Russian and sat for Russian proficiency exams. When ready for his first big intelligence assignment, Oswald took a hardship discharge — ostensibly to take care of his mother in Fort Worth, TX — but left almost immediately for Europe to participate in the United States’ fake defector program. The Soviets never bought Oswald’s defector act. The KGB had Lee shipped him off to toil in a radio factory in Minsk where he could be kept under close surveillance, do little harm, and be used for propaganda purposes. To increase Oswald’s visibility and public reach, in all probability, a fake street fight was staged in early August with “pro-Castro” Oswald and some of Banister’s anti-Castro protégés. This got Oswald arrested for disturbing the peace, but also got him on the evening news. While in NOPD custody, Oswald asked to speak with an FBI agent. An FBI agent did arrive and conversed with Oswald in private for about an hour. Afterwards, at a public hearing, Oswald was fined $10 and released.