For most Americans, the assassination of John F. Kennedy is just a history lesson: a national calamity, to be sure, yet something that happened a long time ago. But for an ever-dwindling number it is much more than that. What happened fifty years ago on November 22 is a remembered event, as vivid as September 11, 2001: a day the world turned upside down.

Whether or not you can remember that awful day, chances are good you don’t believe that Lee Harvey Oswald, acting alone, shot President Kennedy. Few people do. That may have something to do with Oliver Stone, whose incendiary film JFK pointed the finger of blame squarely at government insiders. But it probably has more to do with some people most have never even heard of: ordinary Americans who, back in the 1960s, were the first to demonstrate that the assassination could not have happened the way the government said it did. Their work may one day become an American legend, as familiar as the ride of Paul Revere.

These early critics were mostly private citizens, but they shared an intense interest in an extraordinary event and a determination to do something about it. There were barely a dozen of them, at first, and they were scattered about the United States. Most did not know each other in 1963. Independently, they launched amateur investigations into one of the major events of the twentieth century. Amateur, but effective: over the years, their work has had an enormous impact on public opinion.

Today, on the eve of its fiftieth anniversary, research into the Kennedy assassination is very much alive. Yet the issue has a serious public relations problem; when modern-day critics are acknowledged it is usually derisive. “These people should be ridiculed, even shunned,” The New York Times Book Review sneered in 2007. “It’s time we marginalized Kennedy conspiracy theorists the way we’ve marginalized smokers.”

But the earliest critics were not conspiracy theorists, and this is an important point. They analyzed the government’s case on its merit, testing the official evidence to see whether it could stand on its own. And their analyses led to an inescapable conclusion: there had indeed been a conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy. Who conceived and carried out that conspiracy was an entirely different question.

|

| The New York Times, Feb. 5, 1964 |

A special commission concluded in 1964 that Lee Oswald, alone and unaided, killed JFK and wounded Texas Governor John Connally. They implied it was an open-and-shut case, yet its chairman, Chief Justice Earl Warren, said that for national security reasons not all of the evidence would be made public right away. “There will come a time,” he told a reporter. “But it might not be in your lifetime.”

It didn’t seem to follow. If Oswald was indeed the lone assassin, where was the issue of national security?

President Kennedy had come to Texas to mend political fences, with an eye toward re-election in 1964. Arriving in Dallas late on the morning of November 22, 1963, he rode in a motorcade through the city headed for the Dallas Trade Mart, where he was scheduled to speak to a business luncheon. The streets were crowded with cheering spectators. As the motorcade passed the Texas School Book Depository building in Dealey Plaza, shots rang out – ending the life of the thirty-fifth president of the United States, and touching off an enduring mystery.

Before the day was done, the Dallas police not only arrested Lee Harvey Oswald in connection with the assassination, but also charged him with killing a police officer who had tried to arrest him soon afterward. Oswald vigorously maintained his innocence, yet authorities declared that same day the case was all but closed. “It was obvious,” one critic later said, “that even if this subsequently turned out to be true, it could not have been known to be true at that time.”

A week later, the accused shot dead, new president Lyndon Johnson appointed a commission “to study and report upon all facts and circumstances” relating to these shocking crimes. Known popularly as the Warren Commission after its chairman, it would produce two significant works: a single-volume report and a 26-volume set of hearings and exhibits, the latter being the raw data from which the report was ostensibly derived.

Once those materials were issued, the Warren Commission’s work was finished. But for the first generation of critics, it was just getting underway.

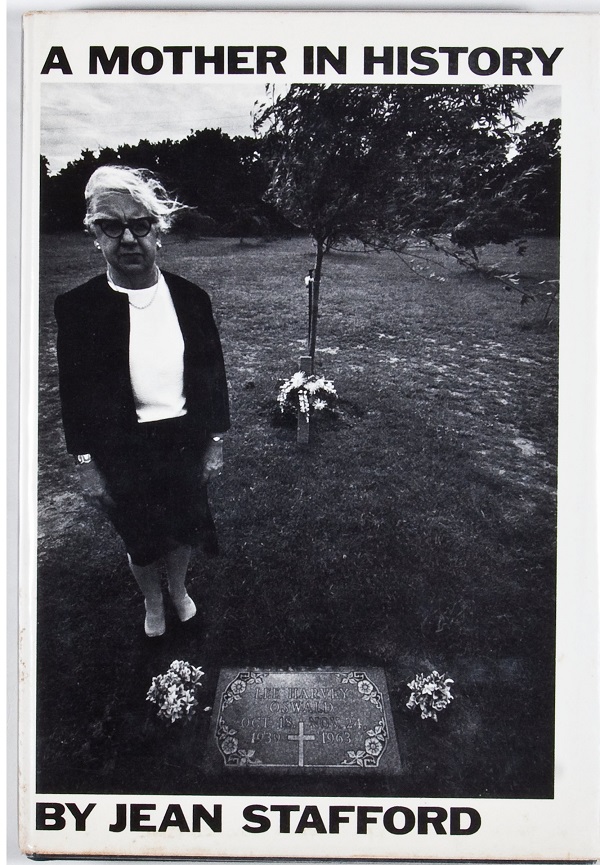

Perhaps the best known of the early critics was an attorney and former member of the New York State Assembly named Mark Lane. Lane briefly represented the mother of accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald and even appeared before the Warren Commission, which had grown curious about his investigative activity.

Disturbed that Oswald had been denied fundamental constitutional rights, Lane wrote a long defense brief on his behalf and sent it to the newly formed Warren Commission. Lane said that even though he was by then dead, Oswald, “from whom every legal right was stripped,” deserved representation before the Commission.

The National Guardian published the brief on December 18, 1963, and The New York Times summarized it in an article that same day. A Times reporter asked if Lane planned to represent Oswald. “He would be willing to take on such a role,” the reporter wrote, “but was ‘not offering’ to do so.”

In Texas, Lee Oswald’s mother welcomed Lane’s appearance on the scene. Marguerite Oswald saw the Times article after an Oklahoma woman named Shirley Martin sent it to her. The two women did not know each other, but Mrs. Martin, concerned that something wasn’t right, instinctively reached out. “My suspicions did not take long surfacing thanks to the Keystone Kops in Dallas,” she recalled years later. After sending the article, Mrs. Martin telephoned Mrs. Oswald about Lane. “We were both excited. Here was Richard Coeur de Lion riding to the rescue in the form of a stouthearted New York lawyer. Marguerite took it from there.”

Mrs. Oswald contacted Lane and asked him to represent her dead son before the commission. But Lane hesitated: the obstacles before him, principally a lack of money, seemed too great. If he took the case he would almost certainly lose his sole corporate client, his bread and butter.

“He’s being tried by the Warren Commission,” Marguerite Oswald countered. “He has no lawyer. Will you represent his interests or didn’t you mean what you wrote?”

Lane agreed to do what he could.

In Los Angeles, businessman Ray Marcus wrote a letter to Earl Warren shortly after the chief justice agreed to head the commission that would soon bear his name. “I join the overwhelming majority of other Americans in extending to you and to your committee my heartfelt support in the arduous and trying task that history has laid before you.”

|

| Raymond Marcus |

Marcus had already begun tracking media coverage of the assassination, and conflicting accounts of what happened fueled his skepticism. He still hoped for an honest investigation. “But with each day,” he recalled, “it was clear that that wasn’t going to be the case.”

Within a few days of the assassination Marcus made a key observation, after Life magazine published an extraordinary series of photographs documenting the entire shooting sequence. These were frames from an eight-millimeter home movie taken by an assassination eyewitness named Abraham Zapruder. “In one of those pictures, a picture of Connally immediately after he was hit, I saw something which led me to believe that at least that shot could not have come from the Book Depository Building,” Marcus said. He couldn’t be sure from Life’s fuzzy reproductions. “But the direction in which the shoulders slumped presented a picture of the man just as he was hit, and it indicated to me that the shot could have come from the front.”

The authorities had already said Oswald, acting alone, shot from behind the motorcade. But the Zapruder film seemed to tell a different story. For the next several years, Marcus would study its frames closely; he would emerge as an authority on the film documenting what have been called the most intensely studied six seconds in United States history.

|

| Harold Weisberg |

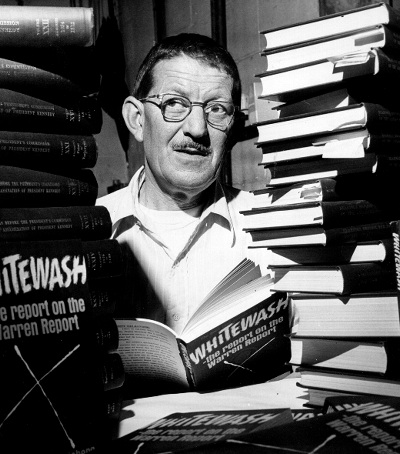

At the time of the assassination, Harold Weisberg was trying to jump-start a writing career he had abandoned some years before. The son of Ukrainian émigrés and the first member of his family born in the United States, Weisberg was a former Senate investigator and journalist living in Maryland. He was immediately skeptical of the lone gunman story out of Dallas, so he drafted an outline for an article and sent it to his literary agent.

The agent, Weisberg always recalled with astonishment, told him that nobody would consider publishing anything other than what the government said. “Can you understand how shocking that was to me?” he later asked. “With my background? And my beliefs about the functions of information in a country like ours?” Weisberg went on to write Whitewash and other books, all of them detailed analyses of the official case, and highly critical of the government’s handling of it.

Other early critics included Mary Ferrell, a Dallas legal secretary; Vincent J. Salandria, an attorney in Philadelphia; Maggie Field, a housewife in Beverly Hills, California; and Sylvia Meagher, a researcher at the World Health Organization in New York, who later wrote a penetrating analysis of the case called Accessories After the Fact. Each was a product of that era some call America’s greatest generation.

For most of these critics the assassination was nothing less than all consuming. “‘Oswald’ is the most spoken word in our house,” Salandria’s wife remarked in 1965. The objective: force a re-opening of the investigation. Although they began following and writing about the case immediately, it wasn’t until 1966 these critics began to get much media attention. Most labored in relative obscurity, and only gradually became aware of each other and their common goal. As they did, they began exchanging ideas and information by telephone, and by what today we refer to as snail mail. There was much the early critics didn’t know. But what they did know was that something was terribly wrong.

For nearly all of the first generation critics, their initial research was simply tracking the assassination story as it was reported in the press, and noticing, in the first days and weeks, its inconsistencies.

Like the rest, Mary Ferrell’s suspicions stirred almost immediately. At the time of the assassination she had just emerged from a Dallas restaurant not far from the scene of the crime. A passerby alerted her to what had happened. At almost the same moment police squad cars sped by, sirens blaring. “I ran into a bookstore and called my husband,” she recalled. He heard Kennedy had been shot in the head, Buck Ferrell told his wife, and no one could survive that kind of wound.

Someone had a radio, and Mrs. Ferrell listened to the first sketchy descriptions of the wanted man. “I stood on Elm and thought that they would never find him with no more than that to go on, in an area containing over a million people.” She was thus astonished when the police arrested Lee Harvey Oswald about an hour later – and even more astonished that he did not match the broadcast description she had heard. “The Dallas Police were not gifted with ESP,” she wryly recalled. “And it just – it didn’t fit. And I said, Something is wrong. And I just, I thought, I’m going to find out what everybody said.”

And so she sent Buck and their three sons to the loading docks of The Dallas Morning News and The Dallas Times-Herald where, in shifts, they awaited each updated edition of the daily papers. “Kind of a round robin, for four days,” Mary Ferrell remembered. “And we got every issue of every paper.”

Mrs. Ferrell came across an article in the November 25th issue of the Times Herald hinting at something ominous. The article, “Anonymous Call Forecast Slaying During Transfer,” stated: “An anonymous telephone call to Federal Bureau of Investigation headquarters at 2:15 a.m. warned that Leo [sic] Harvey Oswald would be killed during his transfer from the city lockup to county jail.” The FBI alerted Dallas authorities – yet still Oswald was gunned down. Both papers were putting out multiple editions of each issue, but that article appeared in just one edition and there was no follow-up. “They junked that,” Mrs. Ferrell said. “There were very few copies of that that got loose.”

|

| Mary and Buck Ferrell |

Her interest further stimulated, Mrs. Ferrell continued collecting assassination-related material and never did stop. By 1970 her collection had become so vast that her husband added a room to the back of their Dallas home. “I can move all my books, papers, file cabinets, etc., out there and give the house back to Buck,” Mrs. Ferrell told a friend. She created an extensive database – originally on index cards, but in later years on a personal computer – and with another researcher, a series of chronologies that charted the people and events relating to November 22, 1963.

In the end, the Warren Commission did not allow Mark Lane to represent the deceased accused assassin. “We are dealing with the mother of Oswald and this lawyer by the name of Lane,” Earl Warren told his commission colleagues in January 1964. “He wants to come right into our councils here and sit with us, and attend all of our meetings and defend Oswald, and of course that can’t be done.”

A few days later, at New York’s Henry Hudson Hotel, Lane spoke about his preliminary findings to a crowd of about five hundred people. For the balance of the year he would lecture publicly about the case, at first just in New York, but soon during an ambitious lecture tour that criss-crossed the nation and even ventured as far away as Eastern Europe.

On February 18, he was in New York for a speech that included an appearance by Marguerite Oswald. An enthusiastic crowd of 1,500 heard Mrs. Oswald say, “All I have is humbleness and sincerity for our American way of life.” She described how she tried to meet with her jailed son before he was murdered, but the Dallas police would not permit it. “Why would Jack Ruby be allowed within a few feet of a prisoner – of any prisoner – when I could not see my own son?”

|

| Sylvia Meagher |

Among those in the hall that night was Sylvia Meagher, a 42-year-old researcher at the World Health Organization. “At that stage, I had little or no thought of doing any independent work or writing on the case,” she recalled. “I contributed both money and information unreservedly to Lane or his associates, and I would have been delighted to help in any possible way.”

Yet she had already written a memorandum recording bitter thoughts. When the Warren Commission published its single-volume report she read it with a critical eye, and soon produced a 40-page article that she began shopping around to major magazines. “The Warren Report,” she wrote, “gives us no justification for declaring that the case is closed.”

There were a lot of questions, just after the assassination, about how many times the President was hit, and where his wounds were located. Even after fifty years, these questions have never had definitive answers.

Harold Weisberg was appalled that so many unanswered questions remained. “None should exist,” he declared. “This was not a Bowery bum; this was the President of the United States.” Post-mortem photographs of the late president’s wounds were never entered into evidence and the Commission members never saw them. Autopsy surgeon James Humes said he was “forbidden to talk,” and acknowledged having burned his autopsy notes. JFK’s neck wound was first reported to be one of entry, but later reported to be an exit wound. The first mention of a back wound was not made until nearly a month after the assassination. “As one version of the wounds succeeded another with dizzying speed and confusion,” Sylvia Meagher observed, “only one constant remained: Oswald was the lone assassin and had fired all the shots from the sixth floor of the Book Depository. When facts came into conflict with that thesis, the facts and not the thesis were changed.”

The conclusion that one bullet caused multiple wounds in JFK and Texas Governor John Connally – the Single Bullet Theory – was undermined by the Warren Commission’s own evidence, the critics argued. That bullet, Commission Exhibit 399, was virtually undamaged, its appearance nearly pristine. The critics compared it to an identical bullet, Commission Exhibit 856, which had been test-fired by ballistics experts at the Army’s Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland. “The test bullet had been fired through the forearm of a cadaver,” said Ray Marcus, whose interest had expanded to include C.E. 399. That test bullet performed “only one of the multiple tasks allegedly executed by 399. Even so, the difference in the appearance of 856 and 399 is striking, as the former is grossly deformed.”

In April 1964 Marguerite Oswald ended her relationship with Mark Lane. Almost immediately Lane formed an organization called the Citizens’ Committee of Inquiry to coordinate an independent investigation into the assassination. From its New York office, the CCI recruited a small army of volunteer investigators, some of who were dispatched to Dallas to interview assassination witnesses on Lane’s behalf.

|

| Vincent J. Salandria |

Among these volunteers were Vince Salandria and his brother-in-law Harold Feldman, a writer and translator. Both men were keenly interested in the assassination when it happened, and together had researched an article published in The Nation the previous January. On the morning of June 24, 1964, they left Philadelphia together in Salandria’s 1955 Buick sedan, armed with lists of names, notes, and other material supplied by Lane’s office. Feldman’s wife Immie accompanied them. Driving almost non-stop, they arrived in Dallas late the next day.

Feldman and Salandria immediately contacted Marguerite Oswald. Media accounts had prepared them for a belligerent, uncooperative woman. “What I heard instead,” Feldman recalled, “was a pleasant ladylike welcome – not a trace of cautious ambiguity, not a second of hesitation in the warm courtesy that carried within it only a faint suggestion of loneliness.” The Feldmans and Salandria met with Mrs. Oswald over the next several days, and Marguerite even had them as overnight guests in her Fort Worth home.

|

|

(L-R): Harold Feldman,

Immie Feldman, Marguerite Oswald

|

Mrs. Oswald escorted the volunteer investigators to some of the key sites in the case. Together they visited Helen Markham, the Warren Commission’s star witness against Lee Oswald for the murder of Dallas Police Officer J.D. Tippit. Mark Lane had already spoken with Mrs. Markham by telephone, and her identification of Oswald as the killer of Tippit seemed shaky. A follow-up interview was important.

Mrs. Markham lived in a small apartment over a barbershop. Mrs. Oswald, Salandria and the Feldmans found her at home, cradling her infant granddaughter in her arms and pacing back and forth. She declined to talk to them because, she said, she had to care for the baby. She would not let them pay for a babysitter, but did finally agree to let them return later in the day. As they spoke, Mrs. Markham allowed Marguerite to briefly hold the baby.

Helen Markham, although a grandmother, was still young, Feldman observed – “but shabby, beaten, and spiritless.”

They returned later that afternoon. As they approached the apartment they noticed two Dallas police cars, which had been parked right outside, pulling away.

What happened next, Feldman later wrote, was “the most pitiful spectacle in our experience.” They knocked on the Markham apartment door. Mr. Markham was now home, and he stood barring the entrance as his wife cowered to one side.

“I’ve never seen that kind of terror,” Salandria recalled years later. “Their teeth were actually chattering. And we could get little from them because of their terror.”

“Please go away,” Mr. Markham had groaned. “Please go away, and don’t come back.”

Marguerite broke in. “You’ve been threatened, haven’t you?”

“Yes,” Mr. Markham replied. “Please, go away!”

Shocked, they did as they were asked. As they got back out to the street and headed toward Mrs. Oswald’s car, Marguerite fought back tears. “That poor man!” she said. “He was frightened to death. What right do they have to threaten him? This is still America, by God.”

Since alerting Marguerite Oswald to Mark Lane’s article, Shirley Martin had gone to Dallas several times to find assassination witnesses and talk to them. Not in any official capacity, of course: curiosity, and the feeling that something was not right, motivated her. Her proximity to Dallas – it was only two hundred miles away – proved an irresistible lure.

By the summer of 1964 Mrs. Martin was in contact with Lane’s office, and Lane asked her to speak with a Dallas woman named Acquilla Clemons. Acquilla Clemons was not an eyewitness to the Tippit murder but was nearby, and witnessed some things that were at odds with what was reported in the press.

The Warren Commission had not called Mrs. Clemons to testify, and these early Citizens’ Committee-sponsored trips first brought her story to light. There were at least three interviews with Mrs. Clemons by committee volunteers over the summer of 1964: by two Columbia University graduate students named George and Pat Nash; Salandria and the Feldmans; and Shirley Martin.

George and Pat Nash were unimpressed with Acquilla Clemons. They wrote that her description “was rather vague, and she may have based her story on second-hand accounts of others at the scene.” Unfortunately the Nashes did not say why they doubted her.

Salandria and Feldman interviewed Mrs. Clemons in early July. No record of their conversation appears to exist, but Salandria later said, “I thought she was entirely credible.”

|

| Shirley Martin |

Shirley Martin spoke to Mrs. Clemons in August, about a month after Salandria and Feldman and the Nashes. She was not at all confident that Acquilla Clemons would talk to her. And so her daughter Vickie, who accompanied her mother, hid a tape recorder in her purse.

For much of the conversation, Mrs. Clemons gave Mrs. Martin a lot of reasons why she didn’t want to talk to her. Mrs. Martin seemed to sense her nervousness. “I’m a private citizen,” she said. “I’m not representing any group.” Still Mrs. Clemons demurred; her employer, she said, did not want her involved in the case in any way.

Undaunted, Shirley continued. “This friend of mine was here…I don’t know if you remember. Mr. Nash? Mr. Salandria? They talked to you?”

“Someone came by my house about two months ago,” Mrs. Clemons replied. They promised to send her a picture of Lee Oswald, she said, but never did.

Finally Mrs. Clemons began to talk. She described seeing two men, neither of them Oswald, in the vicinity of the Tippit killing. More than once since then, she said, the police had warned her not to talk to anyone about what she had witnessed on November 22nd.

“So the police said you’d get a lot of publicity and you’d better not do it?”

“Yeah, I’d better not,” Mrs. Clemons replied. “Might get killed on the way to work.”

“Is that what the policeman said?” Shirley Martin asked.

“Yes,” Mrs. Clemons answered. “See, they’ll kill people that know something about that…there might be a whole lot of Oswalds…you know, you don’t know who you talk to, you just don’t know.”

“You scare me…”

“You have to be careful,” Mrs. Clemons said. “You get killed.”

The Warren Commission’s single-volume Report was published in September 1964, and two months later its 26 volumes of hearings and exhibits. This was the moment that the early critics had been waiting for. “I was wildly excited,” Sylvia Meagher recalled. “I opened the box. There were the 26 volumes, everything I’d been looking forward to studying for a long time.” Meagher went on to write a devastating analysis entitled Accessories After the Fact.

The news media, too, greeted the Warren Report with great enthusiasm – but from a much different perspective. Time magazine called it “amazing in its detail [and] utterly convincing,” while The New York Times said “the evidence of Oswald’s single-handed guilt is overwhelming.” The CBS, NBC and ABC television networks all hailed the Report as the final word on President Kennedy’s assassination, and devoted much airtime to its findings.

Mark Lane, who had been speaking publicly about the weaknesses in the government’s case since January, now began debating the Report and its validity. In October 1964 he sparred with Melvin Belli, the celebrated attorney who had unsuccessfully defended Jack Ruby for murdering Lee Oswald. Belli performed badly and was even jeered by the audience; he conceded that Lane “was bright and he had an almost encyclopedic knowledge of the facts.”

On December 4 Lane took part in a much more important event, appearing with a Warren Commission staff attorney named Joseph Ball at a high school in Beverly Hills, California. It was the first time anyone associated with the Commission agreed to publicly defend its findings. At the time of this confrontation, the Commission’s Hearings and Exhibits had only been available for about a week.

To help Lane prepare, several critics met a few days beforehand and began pouring over these 26 volumes. Their meetings took place at the home of Maggie Field. Most there had been in contact with Lane’s Citizens’ Committee office, but it was the first time they were meeting each other. And it was the first time many of them were getting a good look at the Warren Commission’s official evidence.

While technically not a debate, the strengths and weaknesses in the government’s case were given a thorough airing that night before an overflow crowd of several thousand. For forty-five minutes, Lane held the audience spellbound with a summary of the deficiencies in the case against Oswald. And he assured them it was their right to know the truth. “We are going to remain with this matter until such time as the American people secure that to which we are all entitled in a free, open, and democratic society. And that is some intelligible answers to the thus far unanswered questions of Dallas on November 22.”

But Joseph Ball assured the audience that the Commission had performed with honesty and integrity, and had found the correct answers. He emphasized his independence and impartiality. “It didn’t make any difference to me whether I discovered Oswald was the assassin or that someone else was.”

Mark Lane, Ball charged, was picking and choosing from the evidence, and ignoring that which implicated Oswald. Lane interrupted to challenge this point, and the two argued back and forth. Each managed to call the other a liar. Finally Ball seemed to have had enough: examining Mark Lane, he declared, would only result “in a cat and dog fight.”

“Well that’s all right,” Lane countered. “It’s about time we had a dialog in America on this question.”

When the event was over, a reporter asked audience members about what they had witnessed. “It was like, a shocking drama,” said one. Several added that they found it troubling that someone of Joseph Ball’s stature was unable to answer many of the points Lane made. Most agreed that Lane had won. “The byproduct of his defense of Oswald,” one man said, “is to show that there has been, no matter what the motivation on the part of the Warren Commission, and many areas of government, an attempt to cover up.”

In spite of their diverse backgrounds and political orientations, the first generation critics maintained informal, sometimes uneasy alliances with each other for several years. There were occasional meetings, most notably in October 1965, when some of the critics, including Vince Salandria and Maggie Field, gathered in Sylvia Meagher’s home.

There was great excitement in the fall of 1966 when Republican Congressman Theodore Kupferman proposed a special committee to review the Warren Commission’s work. Nothing ever came of the freshman lawmaker’s idea. But just a few months later there was even more excitement with the electrifying news that New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison had launched his own investigation into the Kennedy assassination.

Garrison freely acknowledged his debt to the work of the critics, in particular that of Mark Lane, Harold Weisberg, and a newcomer named Edward J. Epstein. Lane was among the first of the critics to get actively involved in Garrison’s investigation, lending his expertise; Harold Weisberg, Vincent J. Salandria, and others soon followed. Maggie Field raised funds for the D.A. and made plans to visit New Orleans.

“I have repressed the occasional impulse to rush to the airport and fly to New Orleans,” Sylvia Meagher said in April 1967. But her enthusiasm was short-lived. By that summer Meagher and several others had lost all faith in Jim Garrison. It proved to be an irreconcilable issue between them, and by that fall, Meagher had severed ties with most of the other critics. For better or worse, Jim Garrison’s case ultimately failed. Afterward it seemed to many that the search for truth had been dealt a devastating setback.

That the Warren Commission’s lone gunman theory is so widely rejected today suggests that the critics’ work proved it was wrong. And it did – yet it is also true that public skepticism has always run deep. Surveys taken within a few weeks of the assassination showed widespread doubt about the official story. The numbers have fluctuated over the years, but public opinion polls have consistently revealed this doubt. Perhaps what the critics really did was provide the details to what most Americans, in their bones, already knew.

So who killed JFK? We still don’t know for sure, although theories abound. And while later generations of assassination researchers pursued this question with great zeal, many of the earliest critics stopped short of affixing responsibility. “After all these years,” Sylvia Meagher remarked in 1975, “I still do not know if it was the CIA, the military, LBJ, the Cubans, or the Mafia, or any combination of them. But I always knew, know, and will always know for a certainty that C.E. 399 is a fake, that the autopsy is a fraud, that much of the other hard evidence is suspect or tainted, and that the Warren Report is false and deliberately false.”

Maggie Field once told an interviewer that finding the truth about the murder of JFK was of paramount importance. “Until we can get to the bottom of the Kennedy assassination, this country is going to remain a sick country,” she said. “No matter what we do. Because we cannot live with that crime. We just can’t.”