Martyrs to the Unspeakable – Pt. 3

By James W. Douglass

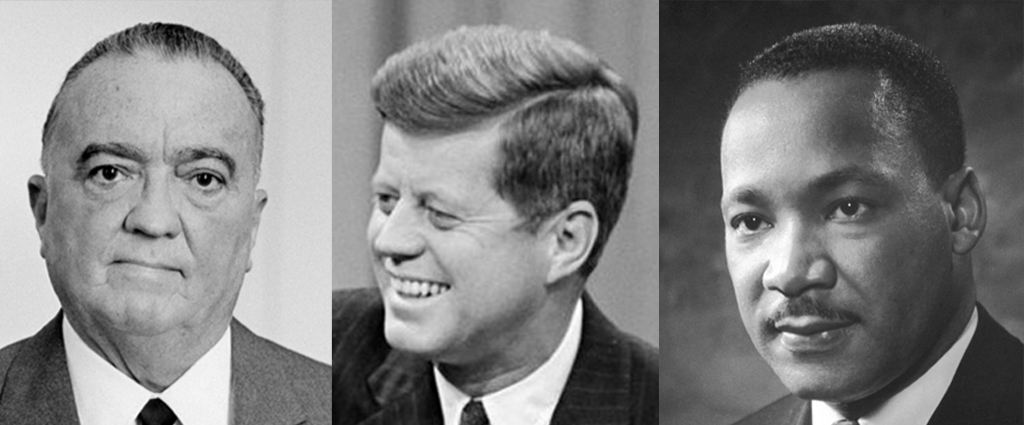

Because James Douglass wrote an entire volume about the presidency and the assassination of John Kennedy, it is that case which gets the least attention in Martyrs to the Unspeakable. Which is a justifiable decision.

But, having said that, Douglass still does deal with JFK. He brings up the case first in its relation to our current troubles: That is, President Kennedy’s dispute with David Ben Gurion and Israel. (p. 10) This important issue is finally getting the attention it deserves through writers like Rick Stirling, Ken McCarthy, and Monica Wiesak. Douglass shows that, quite early, Kennedy was aware of the need for America to come to the aid of the Palestinians who had been impacted by the Nakba. He addressed the problem in 1951. (p. 10). Later on, the author shows that Kennedy never stopped supporting that cause. He was trying to pass a UN resolution to grant relief on November 20, 1963– one which Israel vociferously objected to. (pp. 64-67)

As Kennedy was about to enter the White House, he was alerted by the outgoing Secretary of State, Christian Herter, that there were rumors that Israel might be trying to build an atomic bomb. The problem mushroomed as Douglass notes, because “No American president was more concerned with the danger of nuclear proliferation than John Fitzgerald Kennedy.” (p. 11). The conflict between Kennedy and Prime Minister Ben Gurion began at their first, and only, head of state, face-to-face meeting at the Waldorf Astoria in New York in late May of 1961. At this meeting, Kennedy expressed his curiosity about the size of the atomic reactor at the Dimona site, but Ben Gurion insisted that it was only for desalination. Which, of course, was false.

Kennedy’s interest was in not starting an atomic arms race in the Middle East. (p. 14). Specifically, he thought the possibility existed that if Israel developed a bomb, the Russians would aid Egypt in doing the same. As Douglass notes, this canard by Ben Gurion would mushroom two years later into a direct confrontation, which would result in Ben Gurion’s resignation.

Douglass notes an important conversation that JFK had with Amos Elon, an American reporter for Haaretz. As early as 1961, Kennedy was realizing that the American/Israeli relationship was more useful to Tel Aviv than Washington. And he specifically said, “We sometimes find ourselves in difficulty due to our close relations with Israel.” The president said that the important thing was that the Israelis get along with the Arabs. And if that meant Israel adopting a neutralist stance, he would consider it. As long as there would be an Israeli/Arab settlement. (pp. 16-17)

Douglass now goes to another complicating factor in the Middle East equation. This was Kennedy’s attempt to forge a relationship with Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt. Before his meeting with Ben Gurion, Kennedy wrote to Nasser about a peaceful settlement to the Arab/Israeli conflict and also a viable solution to the Palestinian refugee problem, based on repatriation or compensation. (p. 17) This, as JFK knew, was very important to Nasser.

Ben Gurion was worried about Kennedy’s aim of regular inspection at Dimona. He even encouraged the prominent Jewish lobbyist Abe Feinberg to discourage Kennedy from insisting on this. But Feinberg reported back that Kennedy would not be thwarted. Therefore, as related by former Mossad chief Rafael Eitan, the Israelis built a phony control center over the real one at Dimona, “with fake control panels and computer-lined gauges.” The goal was to make it look like a desalination plant. To top it off, none of the American inspectors spoke Hebrew, which made it easier to conceal the camouflage. (p. 20)

This all escalated until May of 1963 when Kennedy insisted on scheduling full, unfettered and biannual inspections. And if these were denied, he was threatening to pull funding for Israel. After an exchange of four letters, Ben Gurion resigned. This allowed a delay to take place while a new prime minister was chosen. Two months later, the same ultimatum was issued to Levi Eshkol. Eshkol stalled on Kennedy’s request before agreeing to it. But Kennedy’s assassination then occurred, and, as in many other areas, Lyndon Johnson curtailed, stopped and then reversed Kennedy’s policy on both Dimona and the Palestinian refugee dilemma.

In fact, as Douglass writes later, there is evidence that CIA counter-intelligence chief James Angleton actually helped Israel produce its first bomb. Angleton ran the Israeli desk at the CIA. He helped by referring an English scientist named Wilfred Mann to the Israelis. But Angleton denied ever being involved with shipping fissionable materials. In other words, he wanted no part of the NUMEC scandal out of the Pittsburgh area. (p. 58; click here for that story https://consortiumnews.com/2020/08/05/25-years-of-cn-how-israel-stole-the-bomb-sept-11-2016/)

II

Bobby Kennedy did not forget his brother’s devotion to nuclear non-proliferation. He noted it prominently in his maiden speech in the Senate. In that speech, he specifically mentioned how Israel was a problem in this regard. Although they were little noted in the USA, the comments were noted prominently in Israel. Mainly because of RFK’s support of the IAEA, the International Atomic Energy Agency, which did inspections of nuclear plants. (p. 61) These types of professionals would likely have unearthed the Israeli ruse about Dimona. Tel Aviv wanted no part of that.

From here, Douglass shifts the focus to Sirhan Bishara Sirhan. Specifically to the lengthy—150 hours– hypnotic sessions sponsored by the legal team of William Pepper and Laurie Dusek. The late Harvard psychologist, Dr. Daniel Brown, concluded that Sirhan was one of the most susceptible hypnosis subjects he had ever encountered. Brown concluded that he was “…the perfect candidate.”(p. 69)

Sirhan had two disturbing events happen to him in rather close proximity to each other. The first was the death of his sister, who died of leukemia when he was 21. The second event was when he fell off a horse at Granja Vista Del Rio Horse Farm. Sirhan was treated at the Corona Community Hospital emergency room by a Dr. Nelson. He was discharged four hours later. But according to his brother, he was gone for two weeks. (Lisa Pease, A Lie Too Big to Fail, p. 434). Yet he only received four stitches over one eye. Both his mother and a friend tried to find out where he was. (Douglass, p. 73)

With Sirhan under hypnosis, Brown discovered that he was in a ward with no windows and with about seven other patients, all with head injuries. Doctors would approach him each day with clipboards, taking urine samples, and asking him how he felt. When he did return, those close to him detected a personality change; he was more reserved and argumentative. (Douglass, p. 74) But further, you only visit a doctor once to get four stitches removed. So why did Sirhan then visit a doctor 13 more times over the next year, from 1966 to December of 1967? (Pease, p. 435)

III

From here, Douglass goes into the RFK career and his murder. In my view, this was a real highlight of the book. For the Bobby Kennedy of 1968 was probably the most radical candidate for president since Henry Wallace. Douglass goes into RFK’s disputes with President Johnson on civil rights and Vietnam. For example, Marian Wright of the NAACP wanted to attract political attention to Mississippi, since so many African/American children were suffering from hunger. Bobby Kennedy did go down as part of a small sub-committee on poverty. He was greatly impacted by what he saw and wanted Johnson to declare a state of emergency–which he would not. From there, he went to Indian reservations, Appalachia and New York City ghettoes. He wanted to see firsthand what Michael Harrington called the Other America. (Douglass, p. 88)

When LBJ would not act on this issue, even after the riots of the summer of 1967, RFK decided that the man who could act was King. He told Marian Wright to tell King to bring the poor to Washington. So while in Atlanta, she did just that. And as she later said, “Out of that, the Poor People’s Campaign was born.” And King decided that this was then going to be the prime focus of his career. (Douglass, p. 91)

But, as Douglass points out, it was not just this joint opposition to poverty that was worrisome to the Powers That Be. It was also their mutual opposition to the Vietnam War. Kennedy had made a speech against that war in the Senate on March 3, 1967. Almost exactly one month later, on April 4th, King delivered his polemic at Riverside Church in New York.

Most people in this field are aware of President Kennedy’s conversation with Charles de Gaulle about the Vietnam War. What most people do not know is that the French president had a very similar conversation with Bobby Kennedy about the same subject. And Douglass describes it in detail in this book. (pp. 392-94) RFK took a European tour in late January and early February of 1967.

He had two important topics he wished to discuss with some of the leaders he met: atomic weapons and the Vietnam War. He quickly found out that each one of the emissaries he met with thought Johnson’s war policy in Vietnam was so misguided as to be termed mad. When RFK met with de Gaulle, they talked for over one hour. And the exclusive subject was Vietnam. The president reminded Bobby of the advice he had given his brother, namely that the USA should not go into Vietnam. He then said that by directly entering that conflict, America’s special place in the world—one of respect and admiration—had been torn to tatters:

The United States is in the process of destroying a country and a people. America says it is fighting Communism. But by what right does it fight Communism in another people’s country and against their will…. History is the force at work in Vietnam. The United States will not prevail against it. (p. 394)

When they walked to the door, with the 6’4” de Gaulle hovering over the 5’10” Kennedy, the French president gave the senator some sage advice:

Do not become embroiled in this difficulty in Vietnam. Then you can survive its outcome. Those who are involved will be badly hurt, because your country will tear itself apart over it. A great leader will be needed to put it back together and lead it to its destiny…. You must be that leader. (ibid)

How could anyone not be impacted by someone like this? De Gaulle was the man who risked his own life, many times, to get France out of Algeria. Something JFK had advised France to do back in 1957. Douglass had done us all a favor in describing this little-known meeting.

IV

Kennedy’s visit to France had some big blowback when he got back to the USA. There was an article in Newsweek saying that he had received a “peace feeler” from Hanoi while in Paris. The senator did not understand what the report was about, and he told his press secretary that. (p. 409)

What had happened is that on the same day that he had met with de Gaulle, he had a meeting with the Far East desk officer in the French Foreign Office. Kennedy was accompanied by a translator from the American embassy. The desk officer said that North Vietnam was willing to enter negotiations in return for an unconditional bombing halt. The senator did not think this was very important. But the translator did. He cabled his superiors in Washington about the story. And that is how it got in Newsweek. And from there it spread to the MSM, including TV.

President Johnson was quite offended by this story, as he took almost everything RFK did as a personal affront. He thought that Bobby had leaked the story in order to promote himself as a peacemaker. But it was even worse than that. Because Johnson–under the influence of his Vietnam overall commander, William Westmoreland—thought that he was on the verge of winning in Indochina.

When RFK got word of this MSM story, he wanted to straighten things out with the president. So he went to see Johnson. This was a mistake. Instantly, LBJ accused him of leaking the story. Kennedy replied with, “I didn’t leak it. I didn’t even know there was a peace feeler. I think the leak came from somebody in your State Department” (Douglass, p. 410)

Johnson took this reply badly. He said it was not his State Department. It was Bobby’s. Meaning that it was still filled with Kennedy loyalists.

Kennedy tried to change the subject. He offered him what his plan would be to settle in Vietnam: stop the bombing, go to the negotiating table, do a staged cease-fire and create a coalition government governed by an international commission to hold elections as a final solution.

About a year from Tet, Johnson was not in a state of mind to listen to any peace agreement. He made no bones about it either. He began with “There’s not a chance in hell I’ll do that.” Then it got worse:

I’m going to destroy you in six months. We’re going to win in Vietnam by the summer. By July or August the war will be over. You and every one of your dove friends will be dead politically in six months. You guys will be destroyed.

What is really kind of bizarre about this is that it appears that Johnson believed it. He really thought that General Westmoreland was giving him the right info and predicting the correct outcome. RFK had finally gotten a glimpse into Johnson’s real psyche about the most divisive conflict since the Civil War. He appropriately walked out. He now understood de Gaulle’s advice. There was only one way to end the war. Even if it meant the end of him.

V

I would like to close with two sterling episodes from the book.

The first is another conversation I had never seen before. This was between Bobby Kennedy and Giorgi Bolshakov in May of 1961. (pp. 469-70) Bobby called him in and told the Russian spy that his brother thought there could be a lot more cooperation between their two countries. But Jack was taking over from a former general, namely Eisenhower, as president. Therefore, he was stuck with people like Lyman Lemnitzer as chair of the Joint Chiefs and Allen Dulles as Director of the CIA.

Now recall, this was after RFK’s duty on the Taylor Commission investigating the Bay of Pigs. He understood how that debacle had occurred. He knew the CIA had deceived the president, and the Joint Chiefs had approved the operation. So he now delivered the punchline: His brother had made a mistake in not firing Dulles and Lemnitzer right away!

Again, I had never seen this quote before. If you ever wondered where Bobby Kennedy’s later radicalism came from, here it is. He would have gotten rid of Lemnitzer and Dulles on day one. He then expanded on this point:

These men make outdated recommendations and suggestions which are out of keeping with the president’s new course. My brother has been compelled to go by their mistaken judgments in decision making. Cuba has changed all our foreign policy concepts. For us, the events in the Bay of Pigs are not a flop, but the best lesson we have ever learned. So we are no longer going to repeat our past mistakes. (Douglass, p. 469)

RFK knew that this attitude by his brother would put a target on the president’s back: “They can put him away any moment. Therefore, he must tread carefully in certain matters and never push his way through.” This remarkable discussion—four hours’ worth– went on until nightfall. When RFK gave Bolshakov a lift home–at or after 10 PM, the Russian could barely sleep. The next morning, he cabled his summary to Moscow. This is what began the secret communications between JFK and Khrushchev. So intricately described in JFK and the Unspeakable.

If anyone has any knowledge of something similar to this happening since, I would like to hear it. I know nothing like it occurred during the Truman or Eisenhower administrations. It might have been possible under Gorbachev, but Reagan blew that opportunity. Thus paving the way for him to be deposed.

VI

As most of us know, the so-called Bobby Kennedy open and shut murder case was not open and shut. But there were signals at the start that the game was going to be rigged. For instance, as Roger LaJaunesse of the local FBI told Bill Turner, both he and the regular command of the LAPD were shoved aside almost immediately. The LAPD Chief of Detectives, Robert Houghton, installed an elite team of his own officers to run that investigation. It was called Special Unit Senator. And the two men who were in charge were Lt. Manny Pena and Sgt. Hank Hernandez. Both of them had ties to the CIA. And they did their best to keep that angle out of the trial and to censor any exculpatory material to the defense.

But it was actually even worse than that. Thomas Noguchi was the man who performed the autopsy on the senator. He wrote a 62-page report on his findings. The late pathologist Cyril Wecht once called it the finest piece of medico-legal reportage he had ever read. For whatever reason, Noguchi was the last person to testify for the prosecution. In his testimony, both his report and some photographs were admitted into evidence. As Noguchi was beginning to describe the damage to Robert Kennedy’s skull that was revealed during his examination, the lead defense lawyer objected. Grant Cooper said the following:

Pardon me, Your Honor. Is all of this detail necessary? I would object on the ground of immateriality. I hardly think that this testimony of the doctor is necessary in dealing with the cause of the man’s death. I am not suggesting, Your Honor please…this witness may certainly testify to the cause of death, but I don’t think it is necessary to go into details. I think he can express an opinion that death was due to a gunshot wound. (p. 377)

This is astonishing. Because it is Noguchi’s findings that exculpate Sirhan as the killer of Robert Kennedy. And here was Sirhan’s defense attorney handing the prosecution their guilty verdict on a silver platter. As anyone who has read some of the better books on the RFK case should know, all the projectiles that entered the senator were from behind, at upward angles, and at very close range. The wound that Noguchi was about to describe was at contact range, about 3 inches away. (Douglass, p. 388) Which means the gun was so close to the head that expelled particles had nowhere to escape into the air. So they created a tattoo ring on the rear of Kennedy’s skull. (Douglass, p. 387) Sirhan was never behind the senator, and no one ever said that his gun arm was aimed upward or that he was in point contact with the rear of Kennedy’s head.

So why would Grant Cooper object to having the best witness he could have testify to those particular elements of the crime scene?

The answer is simple: Johnny Rosselli. Cooper was serving as attorney for a cohort of Rosselli’s in the Friars Club case right before he took on the RFK case. Maurice Friedman was a Las Vegas frontman for the mob’s casino ownership. Both Friedman and Rosselli ran a card cheating ring at the club, which was frequented by some high rollers from the entertainment industry, like Phil Silvers. Because of the sophisticated cheating apparatus, Friedman won hundreds of thousands of dollars. Rosselli got a cut since it was on his mob turf. (Douglass, pp. 400-401)

But on July 20, 1967, the FBI raided the club. The ring was exposed, and Rosselli and Friedman were indicted. They were worried about being convicted, so they bribed a court reporter for the grand jury minutes in their case. A copy of Phil Silvers’ grand jury testimony was found on Cooper’s desk during the trial. At first, Cooper lied and said he had no idea where it came from. (Douglass, p. 404)

Cooper eventually came clean about what had happened. And it was clear he was facing an indictment. But the inter-agency task force on the Sirhan case was told that this decision would not be made until after the RFK trial. Well, after his less-than-zealous performance for Sirhan, Cooper ended up not being indicted. Defended by a member of the Warren Commission, Joseph Ball, Cooper got off with a slap on the wrist. And a mild one at that. He was fined a thousand dollars. (Click here for the decision https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/ca-supreme-court/1827338.html)

It is quite difficult not to see this in tandem with his horrendous performance in defense of Sirhan. Where he actually stipulated to the prosecution’s evidence.

Jim Douglass has done a fine job in describing and then defining the epochal impact of the four high-level murders of the sixties. They were not the result of aimless violence by disturbed assassins. They were all cleverly worked out plots, and the net result was a large diversion of American history. Which does not get into textbooks. This book is a worthy successor to JFK and the Unspeakable.

The book is available here. Editor’s note: An advance copy was provided for this review. The prior link may also be used for preordering, with an expected release date of Oct 28.

Click here to read part 1.