11. The Secret Service and The Picket Fence.

“The Secret Service agents assigned to the motorcade remained at their posts during the race to the hospital. None stayed at the scene of the shooting, and none entered the Texas School Book Depository Building at or immediately after the shooting. Secret Service procedure requires that each agent stay with the person being protected and not be diverted unless it is necessary to accomplish the protective assignment. Forrest V. Sorrels, special agent in charge of the Dallas office, was the first Secret Service agent to return to the scene of the assassination, approximately 20 or 25 minutes after the shots were fired.” (WCR; p. 52.)

When Sorrels testified before the Commission, he agreed with that time interval. (Volume VII; p. 347/348.)

With the facts established regarding the movements of the Secret Service after the assassination, it is important to consider the following testimonies of Dallas Police Officers Smith, Weitzman, and Harkness along with a witness, Mrs Jack Frazen. These individuals testified or gave depositions, that in the immediate aftermath of the President’s murder, they each encountered individuals who claimed to be agents of the Secret Service and, in some instances, even produced Secret Service credentials.

Joe Marshall Smith testified under oath that he encountered men claiming to be Secret Service behind the picket fence in the immediate aftermath of the assassination.

Joe Marshall Smith. “Yes, sir: and this woman came up to me and she was just in hysterics. She told me, “They are shooting the President from the bushes.” So, I immediately proceeded up here [Grassy Knoll]”

Wesley Liebeler. “You proceeded up to an area immediately behind the concrete structure here that is described by Elm Street and the street that runs immediately in front of the Texas School Book Depository, is that right?”

Joe Marshall Smith. “I was checking all the bushes and I checked all the cars in the parking lot.”

Wesley Liebeler. “There is a parking lot in behind this grassy area back from Elm Street toward the railroad tracks, and you went down to the parking lot and looked around?”

Joe Marshall Smith. “Yes, sir; I checked all the cars. I looked into all the cars and checked around the bushes. Of course, I wasn’t alone. There was some deputy sheriff with me, and I believe one Secret Service man when I got there. I got to make this statement, too. I felt awfully silly, but after the shot and this woman, I pulled my pistol from my holster, and I thought, this is silly, I don’t know who I am looking for, and I put it back. Just as I did, he showed me that he was a Secret Service agent.”

Wesley Liebeler. “Did you accost this man?”

Joe Marshall Smith. “Well, he saw me coming with my pistol and right away he showed me who he was.”

Wesley Liebeler. “Do you remember who it was?”

Joe Marshall Smith. “No, sir; I don’t-because then we started checking the cars. In fact, I was checking the bushes, and I went through the cars. and I started over here in this particular section.” (Volume VII; p. 535.)

Officer Smith said to the Texas Observer that after the assassination “A woman came up to me in hysterics. She said they’re shooting at the President from the bushes, and I just took off. A cement arch stands between the depository building and the underpass. On the underpass side of the arch, there is a fence that lets through almost no light and is neck-high; an oak tree behind the fence makes a little arbor there. A man standing behind the fence, further shielded by cars in the parking lot behind him, might have had a clear shot at the President as his car began the run downhill on Elm Street toward the underpass. Patrol-man Smith ran into this area. I found a lot of Secret Service men I suppose they were Secret Service men and deputy sheriffs and plain-clothes men, he said. He was so put off by what the woman had said—he didn’t get her name—that he spent some time checking cars on the lot, he said. He caught the smell of gunpowder there. he said: “a faint smell of it—I could tell it was in the air…a faint odour of it.” (Texas Observer; 13th December 1963, p. 9.)

Smith characterized the Secret Service imposter in this way:“He looked like an auto mechanic. He had on a sports shirt and sports pants. But he had dirty fingernails, it looked like, and hands that looked like an auto mechanic’s hands. And afterwards it didn’t ring true for the Secret Service. At the time we were so pressed for time, and we were searching. And he had produced correct identification, and we just overlooked the thing. I should have checked that man closer, but at the time I didn’t snap on it.” (Anthony Summers, Not In Your Lifetime; p. 57)

Seymour Weitzman testified that he encountered men claiming to be Secret Service behind the picket fence.

Joseph Ball. “Did you go into the railroad yards”

Seymour Weitzman. “Yes sir”

Joseph Ball. “What did you notice in the railroad yards?”

Seymour Weitzman. “We noticed numerous kinds of footprints that did not make sense because they were going different directions”

Joseph Ball. “Were there other people besides you?”

Seymour Weitzman. “Yes sir; other officers, Secret Service as well, and somebody started, there was something red in the street and I went back over the wall and somebody brought me a piece of what he thought to be a firecracker and it turned out to be, I believe, I wouldn’t quote this, but I turned it over to one of the Secret Service men and I told them it should go to the lab because it looked like human bone.” (Volume VII; p. 107)

Mrs Jack Frazen. According to an FBI report dated 11/22/63 Mrs Franzen had: “observed police officers and plain-clothes men, who she assumed were Secret Service Agents, searching an area adjacent to the TSBD Building, from which area she assumed the shots which she heard had come.” (Volume XXIV; p. 525.)

D. V. Harkness testified that 6 minutes after the assassination he had encountered men at the back of the Texas School Book Depository who claimed to be Secret Service.

David Belin. “Was anyone around in the back when you got there?”

D. V. Harkness. “There were some Secret Service agents there. I didn’t get them identified. They told me they were Secret Service”. (Volume VI; p. 312.)

Jesse Curry. “I think he must have been bogus. Certainly, the suspicion would point to the man as being involved, some way or other, in the shooting since he was in an area immediately adjacent to where the shots were and the fact that he had a badge that purported him to be Secret Service would make it seem all the more suspicious.” (Not In Your Lifetime; p. 58)

According to the Warren Commission’s own findings, the individuals encountered by these witnesses could not have been genuine Secret Service agents. These encounters occurred prior to the return of Forrest V. Sorrels to Dealey Plaza. The presence of these impersonators raises important questions for the case. Who were these individuals claiming to be Secret Service agents? What was their motive or purpose in impersonating members of the Presidents security detail in the immediate aftermath of the President’s murder?

12. The Testimony Which Negates the Single Bullet Theory.

Commission Conclusion: “Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President’s throat also caused Governor Connally’s wounds.” (WCR; p. 19.)

The Testimonies of John & Nellie Connally Which Refute the Commission Conclusion.

Mrs Connally. “When we got past this area I did turn to the President and said Mr President, you can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you. Then I don’t know how soon, it seems to me it was very soon, that I heard a noise, and not being an expert rifleman, I was not aware that it was a rifle. It was just a frightening noise, and it came from the right. I turned over my right shoulder and looked back and saw the President as he had both hands at his neck.”

Arlen Specter. And you are indicating with your own hands, two hands crossing over gripping your own neck?

Mrs. Connally. Yes, and it seemed to me there was—he made no utterance, no cry. I saw no blood, no anything. It was just sort of nothing, the expression on his face, and he just sort of slumped down. Then very soon there was the second shot that hit John. As the first shot was hit, and I turned to look at the same time, I recall John saying “Oh, no, no, no.” Then there was a second shot, and it hit John, and as he recoiled to the right, just crumbled like a wounded animal to the right he said, “My God, they are going to kill us all. (Volume IV, p. 147.)

Governor Connally.

ArlenSpecter. “As the automobile turned left onto Elm from Houston, what did occur there, Governor”?

Governor Connally. “We had, we had gone, I guess, 150 feet, maybe 200 feet, I don’t recall how far it was, heading down to get on the freeway, the Stemmons Freeway, to go out to the hall where we were going to have lunch and, as I say, the crowds had begun to thin, and we could, I was anticipating that we were going to be at the hall in approximately 5 minutes from the time we turned on to Elm Street. We had just made the turn, well, when I heard what I thought to be a rifle shot. I instinctively turned to my right because the sound appeared to come from over my right shoulder, so I turned to look back over my right shoulder, and I saw nothing unusual except just people in the crowd, but I did not catch the President in the corner of my eye, and I was interested, because I immediately, the only thought that crossed my mind was that this is an assassination attempt. So, I looked, failing to see him, I was turning to look back over my left shoulder into the back seat, but I never got that far in my turn. I got about in the position I am in now facing you, looking a little bit to the left of centre, and then I felt like someone had hit me in the back.”

Arlen Specter. What is the best estimate that you have as to the time span between the sound of the first shot and the feeling of someone hitting you in the back which you just described?

Governor Connally. “A very, very brief span of time. Again, my trend of thought just happened to be, I suppose along this line, I immediately thought that this—that I had been shot. I knew it when I just looked down and I was covered with blood, and the thought immediately passed through my mind that there was either two or three people involved or more in this or someone was shooting with an automatic rifle. These were just thoughts that went through my mind because of the rapidity of these two of the first shot plus the blow that I took, and I knew I had been hit, and I immediately assumed, because of the amount of blood, and, in fact, that it had obviously passed through my chest, that I had probably been fatally hit.”

To say that they were hit by separate bullets is synonymous with saying that there were two assassins.” Norman Redlich, Commission Counsel. (Inquest; p. 43 Volume IV, P132-133, watch this)

13.Truth Is Our Only Client Here?

“If this is truth, then black is white. Night is day. And war is peace. This is not truth. This is a false document.” Sylvia Meagher.

Although Robert Kennedy openly endorsed the Warren Commission Report, he held a privately disdainful perspective towards it. RFK had derisively dubbed the extensive 888-page prosecutorial brief a: “shoddy piece of craftsmanship.” Moreover, the southern wing of the Commission, namely Senators Richard Russell, John Sherman Cooper, and Representative Hale Boggs, openly challenged the cornerstone of the Commission’s case: the Single Bullet Theory, expressing their significant dissent.

John Sherman Cooper. “I could not convince myself that the same bullet struck both of them. No, I wasn’t convinced by [the SBT]. Neither was Senator Russell.” (James DiEugenio, JFK Revisited, pp. 30-31)

John Sherman Cooper. “I, too, objected to such a conclusion; there was no evidence to show both men were hit by the same bullet.” (Edward Epstein, Inquest; p.149-150)

Hale Boggs. “I had strong doubts about it [the single bullet theory], the question was never resolved.” (Inquest; pp.149-150)

In a declassified telephone conversation with President Johnson, Russell expressed his frustration with the Commission’s proceedings.

Richard Russell. “Now that damned Warren Commission business whupped me down so, we got through today and I just, you know what I did? I went over, got on the plane and came home and didn’t even have a toothbrush, I didn’t bring a shirt, I got a few little things here, I didn’t even have my pills, my anti histamine pills.”

Lyndon Johnson. “Why did you get in such a rush?”

Richard Russell. “Well, I was just worn out fighting over that damned report”.

Lyndon Johnson. “Well, you got to take an hour out…to get your clothes.”

Richard Russell. “Well, they were trying to prove that the same bullet that hit Kennedy first was the one that hit Connolly…went through him, through his hand, his bone, into his leg, everything else…just a lot of stuff that… I couldn’t hear all of the evidence and cross examine all of them but I did read the record and so I just I don’t know… but I was the only fellow there that practically requested any changes and what the staff got out of it…this staff business always scares me, I like to put my own views down…But we got you a pretty good report”

Lyndon Johnson. “Well what difference does it make which bullet got Connally?”

Richard Russell.“Well, it don’t make much difference but they said that they believed…that the Commission believed that the same bullet which hit Kennedy hit Connolly… well I don’t believe it.”

Lyndon Johnson. “I don’t either.”

Richard Russell. “And so, I couldn’t sign it…. And I said that Governor Connolly testified direct to the contrary and I am not going to approve of that. So, I finally made them said that there was a difference in the Commission in that. Part of them believed that was not so. Course if a fellow was as accurate enough to hit Kennedy right in the neck on one shot and knock his head off with the next one…. Well, he didn’t miss completely with that third shot. But according to their theory he not only missed the whole automobile, but he missed the street. Well, if a man is a good enough shot to put two bullets right in Kennedy, he didn’t miss that whole automobile, nor the street.”

These insights from the conversation between Russell and Johnson highlight the dissenting opinions and doubts surrounding the Single Bullet Theory within the Commission. It becomes apparent that the Warren Commission Report faced internal criticism and concerns regarding its findings. (read this, watch this and this)

14. Jack Ruby and The Dallas Police Department.

Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry. “A great deal has been written about the relationship of the Dallas Police Department with Jack Ruby. We have twelve hundred men in our department, and we had each man submit a report regarding his knowledge or acquaintance with Jack Ruby. Less than fifty men even knew Jack Ruby. And less than a dozen had ever been in his place of business. Most of these that had been in his place of business had been in there because they were sent there on investigations or had answered a call for police service. I believe there was four men in our department that we were able to determine had been there socially. That is off duty. That were present in his nightclub.”

Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry. “A great deal has been written about the relationship of the Dallas Police Department with Jack Ruby. We have twelve hundred men in our department, and we had each man submit a report regarding his knowledge or acquaintance with Jack Ruby. Less than fifty men even knew Jack Ruby. And less than a dozen had ever been in his place of business. Most of these that had been in his place of business had been in there because they were sent there on investigations or had answered a call for police service. I believe there was four men in our department that we were able to determine had been there socially. That is off duty. That were present in his nightclub.”

Numerous witnesses have attested to the fact that Jack Ruby was a well-known associate of the Dallas Police Department. Many officers, detectives, and personnel were familiar with Ruby due to his frequent visits to police headquarters and his connections within the city’s nightclub and entertainment industry. Below I have reproduced just some of the testimony on the record, relating to Ruby’s acquaintance with the Dallas Police Department.

Nancy Hamilton Former Employee of Ruby.

Mark Lane. “Were you employed by Jack Ruby”?

Nancy Hamilton. “Yes, I was. This was in 1961 in Dallas at his club The Carousel and I was bartender, waitress and rather the manager there”.

Mark Lane. “How did you get that job”?

Nancy Hamilton. “Well, I had gone into Dallas not knowing anyone and of course the first place I went was the Police Department and uh they were very kind and got me the job there”.

Mark Lane. “They got you the job at Jack Ruby’s”?

Nancy Hamilton. “Yes, they did”.

Mark Lane. “Did they know Ruby”?

Nancy Hamilton. “Personally, oh yes very well, vouched for him…wonderful person…great man…well known by the Dallas Police Department.”

Mark Lane. “Other than Dallas Police officers what officials did frequent Ruby’s establishment”?

Nancy Hamilton. “Oh…such as your District Attorney which would be Mr Wade”.

Mark Lane. “How many police officers do you estimate Jack Ruby knew on a personal level”?

Nancy Hamilton. At least half and probably two thirds”.

Mark Lane. “There were almost twelve hundred police officers in Dallas in 1963. Would you say Ruby knew six hundred of them”?

Nancy Hamilton. “Oh easily.”

Nancy Hamilton/Rich also reiterated to the Warren Commission the extent of Ruby’s popularity with the Dallas Police.

Nancy Rich. “There is no possible way that Jack Ruby could walk in Dallas and be mistaken for a newspaper reporter, especially in the police department. Not by any stretch of the imagination.”

Leon Hubert. “Is that your opinion?”

Nancy Rich. “That is not my personal opinion. That is fact.”

Leon Hubert. “Well, on what do you base it?”

Nancy Rich. “Ye gods, I don’t think there is a cop in Dallas that doesn’t know Jack Ruby. He practically lived at that station. They lived in his place. Even the lowest patrolman on the beat…knew him personally” (Volume XIV; p. 359.)

Mr Johnson Former Employee of Ruby.

Mark Lane.“Did Ruby know many Dallas Police officers”?

Mr Johnson. “Well yes, he did. I’d say he knew ah probably half of the people on the force”.

Mark Lane. “There were about Twelve hundred police officers on the force”.

Mr Johnson. “Yes, well I am sure he knew about half of them, and he was very nice to them.”

Barney Weinstein Manager of The Theatre Lounge.

“He [Ruby] did know a lot of police. He knew ’em all. He curried their favour all the time.” (Texas Observer, December 13 1963, p. 8.)

Let us use some specifics, Sgt. Patrick Dean said he knew Ruby for approximately three years. (Vol. II, p. 407) Det. Jim Leavelle testified he knew him for approximately 12 years. (Vol. III, p. 16) Det. L. C. Graves, said he knew him for 10 years. (Vol. XIII p. 9) Officer Blackie Harrison, who Ruby concealed himself behind before shooting Oswald, said he knew him for 12 years. (Vol. XII, p. 237). Lt. Jack Revill also knew him for 12 years. (Vol. XII p. 82)

If one goes through the volumes of Commission testimony, one will see that Lt. Rio Pierce knew Ruby for a dozen years, Captain O. C. Jones knew Ruby for over ten years, Detective Buford Lee Beaty knew him for a dozen years, Det. Combest knew him for about five years, Det. R. L. Lowery knew him for several years, Sgt. Steele knew him for about 8 years, Lt. W. Wiggins knew him for a number of years, and Detective Clardy knew him for about 8 years. And again, this does not begin to exhaust the number of police who admitted to knowing Ruby.

Now consider the following exchange between the Commission and Ruby’s friend and roommate George Senator.

Leon Hubert.“What was Jack Ruby’s attitude toward the police as a group?”

George Senator. “Well, all I know is apparently he must like them. They always used to come to see him.”

Leon Hubert. “Tell us about those who came to see him. Do you know who they were?”

George Senator. “I knew a lot of them by face. I didn’t know them all by name.”

Leon Hubert. “Did they come frequently?”

George Senator. “Various ones, yes, every day.” (Volume XIV; p. 213)

Now consider this statement by Detective Will Fritz.

Leon Hubert. “Do you know Jack Ruby at all, or did you know?”

Will Fritz. “Did I know him before; no, sir, I did not… That is the first time I ever saw him, when he was arrested.”(Volume XV; p. 148)

Travis Kirk, Dallas Attorney, 23 Years.“It is inconceivable that Fritz did not know Ruby. Kirk described Fritz as a domineering, dictatorial officer possessing a photographic memory and a thorough knowledge of the Dallas underworld. In light of Ruby’s reputation and notoriety in Dallas prior to the murder of Oswald… Mr Kirk considers it utterly ridiculous that Captain Fritz might pretend that he did not know Ruby, including physical recognition. Mr Kirk states that he would have to question the veracity of Captain Fritz if Fritz were to disclaim knowledge or recognition of Jack Ruby.”

Upon his arrest for the murder of Lee Oswald, Ruby exclaimed to the arresting officers: “You all know me, I’m Jack Ruby.” (Volume XII-XIII; p 399, 308, 30.)

15. ‘The Abortive Transfer’? The Tragic Murder of Lee Oswald.

“The ACLU hold the Dallas police responsible for the shooting of Oswald, saying that minimum security considerations were flouted by their capitulation to publicity…which exposed Oswald to the very danger that took his life”.

We Are Going To Kill Him.

Billy Grammer, a Dallas Police Communications Officer, received an urgent anonymous phone call around 9 pm on November 23, 1963. In an interview for the documentary The Men Who Killed Kennedy, Grammer recalled this incident, saying: “I thought I recognised the voice but at the same time I couldn’t put a face or name with the voice. We talked and he began telling me that we needed to change the plans on moving Oswald from the basement that, uh he knew of the plans to make the move and if we did not make a change the statement, he made precisely was we are going to kill him.” Grammer reported the threat made against Oswald’s life to his superiors. Grammer first learned that Ruby had in fact killed Oswald when he saw it on television the next morning: “No sooner than I had turned it on [TV] and they were telling that Jack Ruby had killed Oswald. Then I suddenly realized, knowing Jack Ruby the way I did, that this was the man I was talking to on the phone last night. At that time, I put the voice with the face, and I knew myself that Jack Ruby was the one that made that call to me the night before. I think it was obvious because he knew me, and I knew him, and he called me by name over the telephone and seeing this and knowing what I knew and what he had said to me it had to be Jack Ruby… He made the statement that we are going to kill him. Which leads me to believe that this was not a spontaneous thing that happened on the spur of the moment he was watching Oswald coming out of the door and all of a sudden, he decided to shoot him. I do not believe that. I think this was a planned event with him being the man to do the shooting.” (watch this)

Will Fritz. “During the night on Saturday night, I had a call at my home from uniformed captain, Captain Frazier, I believe is his name, he called me out at home and told me they had, had some threats and he had to transfer Oswald… I have always felt that that was Ruby who made that call.” (Volume IV; p. 233)

Officer Perry McCoy testified he got a call a few hours before Oswald was moved and this was from a member of a committee of one hundred, and they had voted to kill Oswald while he was being transferred to the county jail. (Volume XIX; p. 537/538) This same threat was given to the FBI and was sent to the DPD’s William Frazier at about 3:30 in the morning of the 24th. (Volume VII, pp. 53-54)

J. Edgar Hoover

In a declassified document authored by J. Edgar Hoover and written mere hours after Oswald’s murder, Hoover voiced his frustration towards the Dallas Police Department, blaming them for Oswald’s death despite explicit warnings from the FBI.

“There is nothing further on the Oswald case except that he is dead. Last night we received a call in our Dallas office from a man talking in a calm voice and saying he was a member of a committee organised to kill Oswald. We at once notified the Chief of Police and he assured us that Oswald would be given sufficient protection. However, this was not done”.

He continued, “Oswald having been killed today after our warnings to the Dallas Police Department, was inexcusable.” (check this)

Sheriff Decker and Secret Service agent Forrest Sorrels disagreed with the timing of the transfer and the method. Both men thought a transfer in the middle of the night with no one around would be the proper way to do such an assignment. And Decker though he should be placed him on the floorboard of the car. (Volume XIX, pp. 537-38; Volume XIII, p. 63) Jim Leavelle thought that Oswald should have been led out to Main Street while the crowd had gathered thereby avoiding all the reporters and cameras. (Volume III, p. 17)

L. C. Graves.“We knew better than to transfer him under those conditions, but we didn’t have any choice.” (watch this)

The procedure used to transfer Lee Oswald, to the county jail, was fundamentally flawed and, without question, should never have been conducted in the manner that it was. A thorough assessment of the circumstances lays bare distinct irregularities and contradictions employed by the Dallas Police. There is indisputable evidence to show that the strategy employed during Oswald’s transfer was egregiously mishandled, serving as the immediate trigger for his untimely demise.

Burt Griffin. “Were you given any instructions as to how you should guard him?”

L. C. Graves. “As I said, I was–told to hold to the arm and walk close to him and Montgomery was to walk behind us and Captain Fritz, and Lieutenant Swain in front of us and that is the way we started out to the elevator, and out of the elevator door over to the jail office”.

Burt Griffin. “Was there any discussion about staying close to Oswald?”

L. C. Graves. “We were instructed to stay close to him, yes.” (Volume XIII; p. 5)

Failure to Follow Established Security Protocols.

Lee Oswald’s transfer to the county jail, was supposed to be safeguarded by a four-man protection team. The arrangement included Will Fritz at the forefront, Jim Leavelle handcuffed to Oswald’s right, L.C. Graves handcuffed to Oswald’s left, and L.D. Montgomery covering the rear. As the plan dictated, this team was to escort Oswald from the basement elevator to the ‘awaiting’ squad car. However, almost immediately after entering the basement, Captain Fritz strayed from the established protocol. Instead of maintaining close proximity to Oswald for protection, Fritz positioned himself several feet ahead, effectively abandoning his assigned post. This aberration in formation created an open space, a gap that Jack Ruby exploited to access Oswald.

Throughout the entire process, Fritz did not check back on Oswald once, which raises concerns about the attentiveness and effectiveness of the protection measures afforded Oswald. Travis Kirk stated to the FBI that: “Anyone not having status in law enforcement or the legal profession who had access to the Dallas Police Department facilities would have to be known to Captain Fritz. Reports from Dallas specify that Ruby did have this access.” Kirk speculated that: “It was to captain Fritz’s advantage that Oswald was killed for it enabled him to close, in Fritz’s words, a murder case based on circumstantial evidence. And that the Oswald case was bound to involve the Dallas Police Department, including Captain Fritz, in controversy for years to come.” Kirk explained that “the Jack Ruby matter, insofar as Captain Fritz is concerned, can be more easily handled by the Dallas authorities.” (read this document and watch this video)

Permitting Unsecured Crowd Proximity.

One major issue in question is why any individuals especially newsmen, were permitted to be in such close proximity to Lee Oswald during his transfer. The police, cognizant of the substantial threats to Oswald’s life, should have enforced a secure perimeter around him. This hypothetical exclusion zone would have been monitored by police personnel, ensuring that anyone attempting to breach the boundary and approach Oswald would be immediately intercepted. The lack of such a safety measure raises serious questions about the adequacy of the security protocols during Oswald’s transfer.

L. C. Graves. “I was under the impression there wouldn’t be any news media inside that rampway, that they would be behind that area over there, but they were in the way. Chief Curry told Captain Fritz that the security was taken care of, that there wouldn’t be nobody in that ramp. Anyway, that cameras would be over behind that rail of that ramp. So, what we expected to find was our officers along the side there, but we found newsmen inside that ramp, in fact, in the way of that car.”

Burt Griffin. “You say you were quite surprised when you saw these news people?”L. C. Graves. “I was surprised that they were rubbing my elbow. You know,if you saw that film, you saw one of them with a mike in his hand. He actually rubbed my elbow. We were in a slight turn when this thing happened, and my attention had been called to that car door, and this joker was standing there with a microphone in his hand, and others that—I don’t know if they were newsmen—they weren’t officers—had cameras around their necks and everything.” (Volume XIII; p. 7/8)

Absence of Personal Protective Equipment.

While the unique circumstances surrounding Oswald’s transfer in 1963 were nothing short of extraordinary, it is nonetheless evident that critical safety measures were conspicuously absent. Oswald, a prisoner under intense scrutiny and heightened danger, was denied essential protective resources, such as body armour, even in the face of palpable threats to his life. While it’s understood that such equipment might not have aligned with the standard protocol at the time, the gravity of the situation undeniably called for extraordinary precautions. The omission of available protective gear, in this case, registers as a considerable oversight. The provision of body armour to Oswald, may have been instrumental in preserving his life.

Lack of Armed Guard Presence.

Despite the high-profile nature of Oswald’s case and the known threats against him, he was not escorted by an armed guard during the transfer. The presence of an armed guard could have potentially deterred an assassination attempt, like the one carried out by Ruby.

Poorly Planned Vehicle Positioning.

The vehicle intended to transport Oswald to the county jail, was not in the correct position at the time of transfer. This meant that Oswald was exposed to potential threats for a longer period.

Jim Leavelle.“All right, when we left the jail cell, we proceeded down to the booking desk there, up to the door leading out into the basement, and I purposely told Mr. Graves to hold it a minute while Captain Fritz checked the area outside. I don’t know why I did that, because we had not made any plans to do so, but I said, Let’s hold it a minute and let him see if everything is in order. Because we had been given to understand that the car would be across the passageway.”

Leon Hubert.“Of the jail corridor?”

Jim Leavelle. “And that, and we would have nothing to do but walk straight from the door, approximately 13 or 14 feet to the car and then Captain Fritz, when we asked him to give us the high sign on it, he said, everything is all set.”

Leon Hubert.“Did you notice what time it was?”

Jim Leavelle.“No; I did not. That is the only error that I can see. The captain should have known that the car was not in the position it should be, and I was surprised when I walked to the door and the car was not in the spot it should have been, but I could see it was in back, and backing into position, but had it been in position where we were told it would be, that would have eliminated a lot of the area in which anyone would have access to him, because it would have been blocked by the car. In fact, if the car had been sitting where we were told it was going to be, see, it would have been sitting directly upon the spot where Ruby was standing when he fired the shot.”(Volume XIII; p. 17)

L. C. Graves.“Well, we got down to the basement. We hesitated on the elevator until Captain Fritz and Lieutenant Swain stepped out. Then we followed them around the outside exit door into the hallway which leads to the ramp and then hesitated there a little bit with Oswald so they could check out there and see that everything was all right, and when we got the go-ahead sign, [from Fritz] that everything was all right we walked out with him… Now, we, Captain Fritz sent Dhority and Brown and Beck on down to the basement in plenty of time to get that car up there for us.” (Volume XIII; p. 7/8)

L.D. Montgomery. “Captain Fritz stepped out into this door leading out to the ramp… and told us, [to] Come on… Like I say, we came out there. They crammed those mikes over there, and we had to slow up for just a second, because they was backing this car into position. It was supposed to have been in position when we got there, but it wasn’t there, so, we had to pause, or slow down for the car to come on back.” (Volume XIII; p. 28/29)

Given the high-profile and volatile nature of Oswald’s case, it’s puzzling why Captain Fritz authorized the transfer process knowing full well that the vehicle was not yet in position to receive Lee? An optimally orchestrated transfer would have ensured that the car was situated correctly before initiating the process. Additionally, had the vehicle been correctly positioned, an additional precaution should have entailed stationing an armed police officer at the open door that Oswald was meant to enter. This would have facilitated a seamless and safer transfer from the basement to the vehicle, providing an extra layer of security to Oswald during this crucial process. This measure would have significantly minimized the potential for any unplanned incidents, such as what tragically transpired.

The Car Horns.

In an unusual occurrence, a car horn sounds as Oswald is led out into the basement, and again just before Ruby stepped out to shoot Oswald.Jim Di Eugenio points out in Reclaiming Parkland, “Once you’re aware of it, it is almost eerie to watch.” Whilst gravely ill in prison Ruby commented about the horns saying: “If you hear a lot of horn-blowing, it will be for me, they will want my blood.” (Reclaiming Parkland; p. 204)

The Dallas Police Department, entrusted with Oswald’s safety, displayed an egregious level of negligence. Their missteps weren’t just minor oversights or simple mistakes. They bore the weighty implications of life and death, resulting in the irreversible consequence of a human life lost prematurely.

Imagine an alternative scenario: Oswald, represented by legal counsel, could have experienced an entirely different outcome. A competent legal representative would likely have challenged the plan to transfer Oswald under such precarious conditions, thus potentially changing the course of history. Yet this was not the case.

To this day, no one from the higher echelons of the Dallas Police Department has been called to account for their role in the circumstances leading to Oswald’s death. This grave oversight is not just a failure of an individual or a department, but a failure of the justice system itself, a sobering reminder of the devastating consequences when those sworn to protect and serve are negligent of their duties.

“Who else could have timed it so perfectly by seconds? If it were timed that way, then someone in the police department is guilty of giving the information as to when Lee Harvey Oswald was coming down.” Jack Ruby. (Volume V; p. 206)

16. Did Ruby’s Life Hinge on Killing Oswald?

“Everything pertaining to what’s happening has never come to the surface. The world will never know the true facts of what occurred—my motives. The people have had so much to gain and had such an ulterior motive for putting me in the position I’m in. Will never let the true facts, come above board to the world.” Jack Ruby.

“Everything pertaining to what’s happening has never come to the surface. The world will never know the true facts of what occurred—my motives. The people have had so much to gain and had such an ulterior motive for putting me in the position I’m in. Will never let the true facts, come above board to the world.” Jack Ruby.

Following the murder, Ruby was promptly detained and transported to a cell in the city jail. Police Officer Don Archer, who had direct contact with Ruby during this time, reported intriguing observations about Ruby’s behaviour in the aftermath of his arrest.

Don Archer. “His behaviour to begin with, he was very hyper. He was sweating profusely. I could see his heart. Course we had stripped him down for security purposes and he asked me for one of my cigarettes, so I gave him a cigarette. Finally, uh after about two hours had elapsed, which put it around 1pm the head of the secret service came up and I conferred with him, and he told me that Oswald had in effect died and it should shock him [Ruby] cause it would mean the death penalty. So, I returned and said Jack it looks like its gon be the electric chair for you. Instead of being shocked he became calm, he quit sweating, his heart slowed down, I asked him if he wanted a cigarette, and he advised me that he didn’t smoke. I was just astonished that this was a complete difference in behaviour of what I had expected. I would say that his life had depended on him getting Oswald.” (watch this and this)

17. The People V. Lee Harvey Oswald.

“Justice denied anywhere diminishes justice everywhere.” Martin Luther King Jr.

Commission Conclusion. “The numerous statements…made to the press by various law enforcement officials, during this period of confusion and disorder in the police station, would have presented serious obstacles to the obtaining of a fair trial for Oswald. To the extent that the information was erroneous and misleading, it helped create doubts, speculations, and fears in the mind of the public which might otherwise not have arisen”. (WCR; p 20.)

The Presumption of Innocence.

“It is a cardinal principle of our system of justice that every person accused of a crime is presumed to be innocent unless and until his or her guilt is established beyond a reasonable doubt. The presumption is not a mere formality. It is a matter of the most important substance.” (read this)

The following statements made by Dallas Law Enforcement Officials expressing their firm belief in Oswald’s guilt, seriously undermined Oswald’s presumption of innocence and confirmed a prejudgement of Oswald’s culpability.

DA Henry Wade. “I would say that without any doubt he’s the killer, the law says beyond a reasonable doubt and to a moral certainty which I…there’s no question that he was the killer of President Kennedy.”

Reporter. “How do you sum him up, as a man based on your experience with criminal types?”

Wade. “Oh I think he’s…uh… the man that planned this murder, weeks or months ago… and has laid his plans carefully and carried them out and has planned at that time what he’s gonna tell the police that are questioning him at present”

Gerald Hill. 11/22/63.

Reporter. “Do you believe he is the same man that killed the police officer?”

Gerald Hill. “Having been in it from the very beginning, as far as the officer’s death is concerned, I am convinced that he is the man that killed the officer.” (watch this)

“Any prosecutor can convict a guilty man. It takes a great prosecutor to convict an innocent man.” Hidden motto of Wade’s office. (Reclaiming Parkland; p.74)

The notion of a “great prosecutor” convicting an innocent man, as indicated above, raises serious concerns about the practices of the Dallas prosecutor’s office. This implies a mindset that prioritizes securing convictions over ensuring the integrity of the legal process. This approach contradicts the fundamental principles of justice, which demand fairness, objectivity, and a commitment to the pursuit of truth rather than the mere tallying of convictions.

In a divergent assessment from District Attorney Henry Wade’s public statements, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover communicated a differing evaluation of the evidence in the case against Oswald to President Johnson on November 23, 1963. Hoover revealed his disappointment with the Dallas Police Department’s inability to build a convincing case proving Oswald’s guilt, a view that stood in stark contrast to Wade’s publicized optimistic portrayal of the investigation’s progress.

Hoover conveyed: “This man in Dallas. We, of course, charged him with the murder of the President. The evidence that they have at the present time is not very, very strong…The case as it stands now isn’t strong enough to be able to get a conviction.” (read this)

On November 24th, Hoover detailed his attempts to manage the media narrative surrounding the investigation, frustrated with the local police’s public discourse. He recounted,“I dispatched to Dallas one of my top assistants in the hope that he might stop the Chief of Police and his staff from doing so damned much talking on television. They did not really have a case against Oswald until we gave them our information… all the Dallas police had was three witnesses who tentatively identified him as the man who shot the policeman and boarded a bus to go home shortly after the President was killed.”

Hoover expressed his concern over Oswald’s potential defense, remarking, “Oswald had been saying he wanted John Abt as his lawyer and Abt, with only that kind of evidence, could have turned the case around, I’m afraid. All the talking down there might have required a change of venue on the basis that Oswald could not have gotten a fair trial in Dallas.”

He expressed his exasperation with the police department’s uncontrolled dissemination of information to the press, emphasizing:“Chief of Police Curry I understand cannot control Capt. Fritz of the Homicide Squad, who is giving much information to the press… we want them to shut up.”

Regarding the way in which Oswald’s murder transpired Hoover continued, “It will allow, I’m afraid, a lot of civil rights people to raise a lot of hell because he was handcuffed and had no weapon. There are bound to be some elements of our society who will holler their heads off that his civil rights were violated—which they were.” (read this)

Nick Katzenbach also echoed Hoovers frustrations with the Dallas officials.“The matter has been handled thus far with neither dignity or conviction. Facts have been mixed with rumour and speculation. We can scarcely let the world see us totally in the image of the Dallas police when our President is murdered.” (read this)

The following remarks by Mark Lane and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) highlight the profound concerns about Lee Oswald’s presumption of innocence status and his prospects of receiving a fair trial anywhere in the United States.

“In all likelihood there does not exist a single American community where reside 12 men or women, good and true, who presume that Lee Harvey Oswald did not assassinate President Kennedy.” A Lawyers Brief, Mark Lane. (read here)

“The American Civil Liberties Union charged yesterday that the police and prosecuting officials; of Dallas committed gross violations of civil liberties in their handling of Lee H. Oswald, the accused assassin of President Kennedy. The group said that it would have been “simply impossible” for Oswald, had he lived, to obtain a fair trial because he had already been “tried and convicted” by the public statements of Dallas law enforcement officials. The organization proposed that the special panel created by President Johnson to investigate the assassination of President Kennedy should also examine the treatment accorded Oswald. The Dallas police and District Attorney Henry Wade have contended that Oswald’s rights were not infringed. The liberties union raised these questions:

Q. How much time elapsed before Oswald was advised of his rights to counsel?

Q. How much time elapsed before Oswald was permitted access to a telephone to call his family and an attorney?

Q. During what periods and for how long was Oswald interrogated?

Q. What methods of interrogation were used?

Q. Was Oswald advised of his right to remain silent?

The ACLU described the transfer of Oswald as “a theatrical production for the benefit of the television cameras…. It is our opinion that Lee Harvey Oswald, had he lived, would have been deprived of all opportunity to receive a fair trial by the conduct of the police and prosecuting officials in Dallas, under pressure from the public and the news media. From the moment of his arrest until his murder two days later, Oswald was tried and convicted many times over in the newspapers, on the radio, and over television by the public statements of the Dallas law enforcement officials. Time and again high–ranking police and prosecution officials state[d] their complete satisfaction that Oswald was the assassin…As their investigation uncovered one piece of evidence after another, the results were broadcast to the public. All this evidence was described by the Dallas officials as authentic and incontestable proof that Oswald was the Presidents assassin. The cumulative effect of these public pronouncements was to impress indelibly on the public’s mind that Oswald was indeed the slayer. With such publicity, it would have been impossible for Oswald to get a fair trial in Dallas or anywhere else in the country. Oswald’s trial would have been nothing but a hollow formality. The American Civil Liberties Union (see this)

Oswald declines the right to counsel?

“The ACLU recalled that Greg Olds, president of the Dallas Civil Liberties Union and three volunteer lawyers went to the city jail late in the evening Nov. 22, the day the President was assassinated. They were told by police officials, including Capt. Will Fritz, head of the homicide bureau, and Justice of the Peace David Johnston before whom Oswald was first arraigned that Oswald had been advised of his right to counsel but that he had declined to request counsel. Since the ACLU attorneys had not been retained by either Oswald or his family, they had no right to see the prisoner nor give him legal advice”. (The American Civil Liberties Union) (see this)

11/22/63, Oswald Requests A Lawyer.

Lee Oswald consistently expressed his desire for legal representation during his detention. He repeatedly requested legal assistance and expressed confusion about the charges against him. These statements, captured by reporters illustrate Oswald’s awareness of his rights and his desire to have legal counsel present during his questioning.

Lee Oswald. “These people have given me a hearing without legal representation or anything”

Reporter. “Did you shoot the President?”

Lee Oswald. “I didn’t shoot anybody, no sir.”

Reporter. “Oswald did you shoot the President?”

Lee Oswald. “I didn’t shoot anybody sir I haven’t been told what I am here for.”

Reporter. “Do you have a lawyer?”

Lee Oswald. “No sir I don’t.”

Lee Oswald. “I would like some legal representation, but these police officers have not allowed me to, to have any. I don’t know what this is all about.”

Reporter. “Kill the President?”

Lee Oswald. “No sir I didn’t. People keep asking me that.”

Friday Night Press Conference.

Lee Oswald. “I positively know nothing about this situation here. I would like to have legal representation. Well, I was uh questioned by a judge however I uh protested at that time that I was not allowed legal representation during that very short and sweet hearing. I really don’t know what this situation is about, no one has told me anything except I am accused of murdering a policeman. I know nothing more than that and I do request someone to come forward to give me a legal assistance.”

Reporter. “Did you kill the President?”

Lee Oswald. “No, I have not been charged with that in fact no one has said that to me yet. The first thing I heard about it was when the newspaper reporters in the hall asked me that question.”

Reporter. “You have been charged.”

Lee Oswald. “Sir?”

Reporter. “You have been charged.” (watch this)

William Whaley. “He showed no respect for the policemen, he told them what he thought about them. They knew what they were doing, and they were trying to railroad him, and he wanted his lawyer.” (Volume II p. 261)

Gerald Hill. “He had previously in the theatre said he wanted his attorney.”

David Belin. “He had said this in the theatre?”

Gerald Hill. “Yes; when we arrested him, he wanted his lawyer. He knew his rights.” (Volume VII; p. 61)

Lawyers such as Percy Foreman and Joe Tonahill expressed doubts about the strength of the evidence against Oswald and believed that a fair trial would likely result in a verdict of not guilty due to insufficient evidence. Their opinions further support the contention that Oswald’s trial would have been an exercise in futility and lacked the substance necessary for a fair determination of his guilt or innocence.

Lawyer Percy Foreman. “Authorities are running a serious risk of jeopardizing their case against Oswald by failing to observe his constitutional rights.” He went on to state: “Officials may have already committed reversible error in the case by permitting the accused to undergo more than 24 hours of detention without benefit of legal counsel.” Citing grounds for reversal, Foreman further asserted: “Under recent decision of the United States Supreme Court, federal procedural guarantees must be observed in state prosecutions. Their abridgement can be grounds for a reversal or even a conviction. This is a new law. They could get a conviction in Texas and get it thrown out on appeal, but it takes a long time for these dim-witted law enforcement officers to realize it.” (St Louis Post Dispatch, 11/24/63)

Joe Tonahill, Counsel for Jack Ruby.

Interviewer. “Mr. Tonahill, what, in your opinion, would have been the outcome of a trial, had Oswald gone to trial?”

Joe Tonahill. “In my opinion…. Under Texas Law…a trial judge, trying him… the judge would have had a weak circumstantial evidence charge to go to the jury. In my opinion he wouldn’t have had that. He would have been forced to instruct the jury to return a verdict of Not Guilty, on the grounds of insufficient evidence.” (watch this)

“At about 5:30 p.m. [Oswald] was visited by the president of the Dallas Bar Association with whom he spoke for about 5 minutes.” (WCR; p199.)

President of the Dallas Bar Association Louis Nichols:

“I asked him if he had a lawyer, and he said, well, he really didn’t know what it was all about, that he was, had been incarcerated, and kept incommunicado.” When asked who Oswald wanted to represent him, Oswald confirmed, “Either Mr. Abt or someone who is a member of the American Civil Liberties Union. I am a member of that organisation, and I would like to have somebody who is a member of that organisation represent me.” Nichols replied, “I’m sorry, I don’t know anybody who is a member of that organization. Although, as it turned out later, a number of lawyers I know are members.” Oswald stated that, “if I can find a lawyer here who believes in anything I believe in, and believes as I believe, and believes in my innocence, then paused a little bit, and went on a little bit and said, as much as he can, I might let him represent me.” Nichols testified to the likelihood that he personally could have represented Oswald, “I wanted to know whether he needed a lawyer, and I didn’t anticipate that I would be his lawyer, because I don’t practice criminal law.” (Volume VII; p. 325-332)

Oswald’s distress should have been alarming to Nichols. However, it remains unclear why, following their meeting, Nichols didn’t reach out to Mr. Olds to inform him about Oswald’s plea for ACLU representation? Press conference conducted by Nichols in which he confirms Oswald’s request to be represented by John Abt or a lawyer from the ACLU: watch here.

Oswald had explicitly expressed his concerns, not only to the Nichols but also directly to the press, about his maltreatment at the hands of the Dallas Police. He protested that he wanted his, “basic fundamental hygienic rights, I mean like a shower… and… uh… clothes.” (watch here)

President of the Dallas ACLU Gregory Lee Olds.

Gregory Lee Olds. “I called the police department to inquire about this [counsel for Oswald], and finally talked to Captain Fritz, Capt. Will Fritz, and was-raised the question, and he said, “No” that Oswald had been given the opportunity and declined.”

Sam Stern. “Excuse me. Did Captain Fritz say that Oswald did not want counsel at that time, or that he was trying to obtain his own counsel?”

Gregory Lee Olds. “What I was told that he had been given the opportunity and had not made any requests… Captain King [also had] assured us that Oswald had not made any requests for counsel.” (Volume VII p.323)

Denied legal representation, Oswald’s opportunity to mount a defense in the face of hours of questioning was drastically compromised. Compounded by severe media bias and prejudiced public statements from Dallas police and prosecution officials, his chances of receiving a fair trial rapidly dwindled. Here is an object lesson in the presumption of innocence, the right to legal counsel, and providing an impartial platform for every accused person to defend themselves.

Louis Nichols, despite publicly stating and testifying that he did not practice criminal law, was paradoxically allowed to meet with Oswald. In contrast, Gregory Lee Olds, the President of the Dallas ACLU whom Oswald had sought for representation, was unequivocally denied access on the grounds that Oswald did not want legal counsel. This puzzling discrepancy further underscores the gravity of Oswald’s situation and the troubling injustice perpetuated in his case.

The disturbing parallels between Oswald and the other suspects prosecuted by Wade become apparent when examining public statements made by Craig Watkins, who took over as DA from Wade in 2006. Watkins asserted “There was a cowboy kind of mentality, and the reality is that kind of approach is archaic, racist, elitist and arrogant.”

Detractors of Wade, including Watkins, have pointed out numerous problems with cases prosecuted under Wade’s tenure. Allegations of shoddy investigations ignored evidence, and lack of transparency with defense lawyers paint a grim picture of the justice system under Wade. His promotion system, which allegedly favoured prosecutors with high conviction rates, has come under intense scrutiny. As Michelle Moore, a Dallas County public defender and president of the Innocence Project of Texas, observed, “in hindsight, we’re finding lots of places where detectives in those cases, they kind of trimmed the corners to just get the case done.”

John Stickels, a criminology professor at the University of Texas at Arlington and a director of the Innocence Project of Texas, identifies a culture of “win at all costs” as a key problem. In his view, once a suspect was arrested under Wade’s tenure, their guilt was often presumed.”When someone was arrested, it was assumed they were guilty. I think prosecutors and investigators basically ignored all evidence to the contrary and decided they were going to convict these guys.”

The parallels between Wade’s regime and the miscarriage of justice in Oswald’s case is compelling.

As a result: “No other county in America — and almost no state, for that matter — has freed more innocent people from prison in recent years than Dallas County, where Wade was DA from 1951 through 1986.”

18. Rush to Judgement.

“Had I known at the outset, when I wrote that article for the National Guardian, that I was going to be so involved that I would close my law practice, abandon my work, abandon my political career, be attacked by the very newspapers in New York City which used to hail my election to the state legislature; had I known that – had I known that I was going to be placed in the lookout books, so that when I come back into the country, I’m stopped by the immigration authorities – only in America, but no other country in the world – that my phones would be tapped, that not only would the FBI follow me around at lecture engagements, but present to the Warren Commission extracts of what I said at various lectures – I am not sure, if I knew all that, that I ever would have written that article in the first place.” Mark Lane. (watch here)

J. Edgar Hoover and Nicholas Katzenbach, the Deputy Attorney General, revealed their pressing concern about convincing the public of Lee Oswald’s sole guilt in the immediate aftermath of his murder.

J Edgar Hoover, 11/24/63. “The thing I am concerned about and so is Mr. Katzenbach is having something issued so we can convince the public that Oswald is the real assassin.”

Nicholas Katzenbach, 11/25/63. “The public must be satisfied that Oswald was the assassin; that he did not have confederates who are still at large; and that the evidence was such that he would have been convicted at trial.”

This haste in determining Oswald’s guilt following his preventable death exemplified an alarming compromise between public reassurance and the respect for essential legal principles. The urgent need to alleviate public anxiety overshadowed the necessity for a thorough investigation and due process. This swift conviction of Oswald exposed a troubling discrepancy between societal demands during a crisis and the principles of justice, casting a pall over the entire case.

Unquestionably, every US citizen, is constitutionally granted the presumption of innocence and a fair trial. However, these inherent rights were hastily disregarded in Oswald’s case, representing not only an individual miscarriage of justice but also inhibiting a broader, more comprehensive investigation.

The hasty conclusions drawn by officials such as Hoover, Katzenbach, and Dallas law enforcement egregiously compromised the fundamental legal maxim of ‘presumed innocent until proven guilty.’ This resulted in a severe infringement of Oswald’s civil and constitutional rights. The abrupt demise of Oswald exacerbated this problem, forever eliminating the possibility of a trial and thus amplifying the precipitous rush to judgment. As a result, this premature rush towards a verdict prompted the untimely abandonment of several potential investigative pathways. These could have included exploring the potential involvement of accomplices, delving into various avenues of conspiracy, and thoroughly assessing Oswald’s claimed innocence.

19. Are You Lee Oswald? Or Alek Hidell?

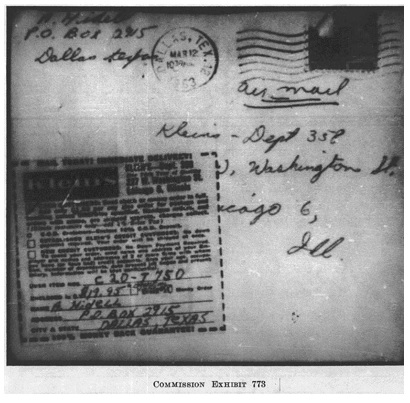

Commission Conclusion. “The arresting officers found a forged selective service card with a picture of Oswald and the name “Alek J. Hidell” in Oswald’s billfold.”(WCR; p. 181)

What is the chain of custody of the Selective Service Card?

What is the chain of custody of the Selective Service Card?

Immediately following his arrest at the Texas Theatre, Oswald was placed in a squad car heading to city hall. Officers Gerald Hill, Bob Carrol, Paul Bentley, C.T. Walker, K.E. Lyons, and the suspect Lee H. Oswald were all present in the squad car.

The statements and reports of the witnesses.

Gerald Hill. 11/22/63, NBC News.

Gerald Hill.“The only way we found out what his name was, was to remove his billfold and check it ourselves; he wouldn’t even tell us what his name was.”

Reporter.“What was his name on the billfold?”

Gerald Hill. “Lee H. Oswald, O-S-W-A-L-D.” (Volume XXIV; p. 804/805)

4/8/64. In his testimony to the Warren Commission. Hill said he first heard the name Hidell in the car transporting Oswald to the station from Paul Bentley.: “I can’t specifically say that is what it was…but that sounds like the name I heard.” Hill said they had two different identifications and two different names. (Volume VII, p. 58)

Paul Bentley. 12/2/63. Report To Chief Curry.

“On the way to city hall I removed the suspect’s wallet and obtained his name…I turned his identification over to Lt. Baker. (Volume XXIV; p. 234)

Paul Bentley was not called to testify.

Bob Carrol provided testimony to the Commission on two separate occasions. The first testimony took place on April 3, 1964, while the second testimony occurred on April 9, 1964. During his second appearance, Carrol specifically mentioned the ‘Hidell’ card. It is reasonable to infer that he was called back to testify because of this particular detail.

David Belin. “Was he ever asked his name?”

Bob Carroll. “Yes, sir; he was asked his name.”

David Belin. “Did he give his name?”

Bob Carroll. “He gave, the best I recall, I wasn’t able to look closely, but the best I recall, he gave two names, I think. I don’t recall what the other one was.”

David Belin. “Did he give two names? Or did someone in the car read from the identification?”

Bob Carroll. “Someone in the car may have read from the identification. I know two names, the best I recall, were mentioned.” (Volume VII; p.25)

Officer C. T. Walker. 4/8/64.

David Belin.“You recall any other conversation that you had with him, or not?”

Officer Walker. “No; he was just denying it.” “About the time I got through with the radio transmission, I asked Paul Bentley, why don’t you see if he has any identification. Paul was sitting sort of sideways in the seat, and with his right hand he reached down and felt of the suspect’s left hip pocket and said, “Yes, he has a billfold,” and took it out. I never did have the billfold in my possession, but the name Lee Oswald was called out by Bentley from the back seat, and said this identification, I believe, was on the library card. And he also made the statement that there was some more identification in this other name which I don’t remember, but it was the same name that later came in the paper that he bought the gun under.”

David Belin. “Anything else about him on your way to the police station?”

Officer Walker. “He was real calm. He was extra calm. He wasn’t a bit excited or nervous or anything. That was all the conversation I can recall going down.”

David Belin. “After you got down there, what did you do with him?”

Officer Walker. “We took him up the homicide and robbery bureau, and we went back there, and one of the detectives said put him in this room. I put him in the room, and he said, “Let the uniform officers stay with him.” And I went inside, and Oswald sat down, and he was handcuffed with his hands behind him. I sat down there, and I had his pistol, and he had a card in there with a picture of him and the name A. J. Hidell on it.”

David Belin. “Do you remember what kind of card it was?”

Officer Walker. “Just an identification card. I don’t recall what it was.”

David Belin. “All right.”

Officer Walker. “And I told him, “That is your real name, isn’t it?”

David Belin. “He, had he earlier told you his name was Lee Harvey Oswald?”

Officer Walker. “I believe he had.”

K. E. Lyons was not called to testify.

12/2/63. Reports To Chief Curry.

The arresting officers present in the squad car – K.E. Lyons, Bob Carroll, and C.T. Walker – provided reports to Chief Curry that intriguingly made no mention of the Selective Service card baring the name Hidell. (Sylvia Meagher, Accessories After The Fact, p.186)

According to the testimony of Dallas Police officer W. M. Potts, he along with two other officers, E. L. Cunningham, Bill Senkel and Justice of The Peace David Johnston, went out to 1026 North Beckley shortly after 2pm on 11/22/63. Potts testified that:

Joesph Ball. “And you went out to where?”

Walter Potts. “1026 North Beckley”.

Joesph Ball. “What happened when you got there?””

Walter Potts. “We got there, and we talked to this Mrs.–I believe her name was Johnson.”

Joesph Ball. “Mrs. A. C. Johnson?”

Walter Potts. “Mrs. Johnson and Mrs. Roberts.”

Joesph Ball. “Earlene Roberts?”

Walter Potts. “Yes; and they didn’t know a Lee Harvey Oswald or an Alex Hidell either one” (Volume VII; p. 197)

However, the mention of the name Hidell by the attending officers is disputed by witnesses who were present in the rooming house on November 22, 1963. When the police arrived at the Beckley rooming house, both the owner Mrs. Johnson and the manager Mrs Robert said they were only asked about Oswald, not Hidell. And they said that Oswald registered as O. H. Lee. (Volume X, pp. 303-04; Volume X p. 295; Volume Vi p. 438)

In a report by Justice Johnston on 11/22/63, listing all of Lee Oswald’s particulars, Justice Johnston writes: Alias, O. H. Lee- 1026 N Beckley. No mention of A. J. Hidell. (Volume XX; p. 313)

Detective Richard Sims testified that he had taken off Oswald’s identification bracelet before administering his paraffin test on November 22, 1963.

Joseph Ball.“Did you see any identification bracelet on Oswald?”

Richard Sims. “Yes, sir; he had an identification bracelet.”

Joseph Ball. “Did he have that on at the time of the showup?”

Richard Sims. “Yes.”

Joseph Ball. “Did you ever remove that?”

Richard Sims “Yes, sir; when they were getting his paraffin cast on his hands.”

Joseph Ball. “And what did you do with that identification bracelet?”

Richard Sims. “I placed it in the property room cardsheet.”

Joseph Ball. “Did you examine that identification bracelet?”

Richard Sims. “Yes, sir”.

Joseph Ball. “What did it have on it, if you remember?”

Richard Sims. “It had his name on it.” (Volume VII; p. 174)

Challenging the Existence of the Hidell Card on November 22, 1963.

Challenging the Existence of the Hidell Card on November 22, 1963.

- Upon his arrest and subsequent detention, Lee Oswald had on a identification bracelet inscribed with the name ‘Lee’. Given this fact, it seems perplexing how the Dallas Police could have possibly thought his name was Alek?

- The alias- ‘Hidell’ does not appear in any of the records or statements from the Police, FBI, or Secret Service dated November 22, 1963. On the other hand, the alias ‘O. H. Lee’ was prominently circulated among the media on the day of the assassination.

- Upon the Dallas Police’s arrival at 1026 North Beckley, around 2pm on November 22, 1963, three separate witnesses confirm that the Dallas officers, inquired solely about a Lee Harvey Oswald. There was no mention of ‘Alek J. Hidell’.

- Oswald’s possession of the Service card, featuring his picture and a name directly linked to the Carcano stashed on the sixth floor, raises some perplexing questions. If Oswald were solely culpable, why would he take the gamble of retaining this potentially condemning evidence?

- What proof is there that Oswald made use of the Select Service card prior to the assassination?

- Has there been any testimony of anyone having seen this ID in Oswald’s possession prior to November 22, 1963?

- When and where was this ID card manufactured?

- Did any fingerprints found on the card match those of Oswald’s?

- Were any photographs taken of this card on November 22, 1963?

- Was this card itemized on an inventory of Oswald’s personal effects at the time of his booking on November 22, 1963?

- Selective Service Cards did not typically include the holder’s picture. The presence of a photograph would inevitably raise suspicion to anyone who saw the ID.

- The card appears to be a complex forgery, necessitating the forger’s access to high-quality equipment like a professional-grade camera, often found in photo labs or printing facilities, and a typewriter. (Volume IV; p. 388)

- Commission Conclusion: “Two typewriters were used in this typing, as shown by differences in the design of the typed figure 4.” The Commission however made no attempt to trace the typewriters, alleged to have been used in the creation of the forged Hidell card. Establishing Oswald’s access to these machines would have been instrumental in validating that he could have created the forged Hidell card. As noted in forensic examination principles, “To determine whether a particular typewriter produced a questioned document, examiners search for individual characteristics that can include misaligned or damaged letters, abnormal spacing before or after certain letters, and variations in the pressure applied to the page by some letters. For example, certain letters can have telltale nicks or spurs that are imprinted on the page, or they can lean to one side or print slightly higher or lower than the others. These defects can be compared to a sample from a suspect typewriter and thus offer powerful individualizing characteristics.” (WCR;p. 572) (see this)

- The Commission relates to the creator of the card as the “counterfeiter” not specifically to Oswald. (WCR; p. 571)

- The Selective Service Card, along with the introduction of the alias ‘Hidell’, only emerges in the case on November 23, 1963. Interestingly, this is the same day the FBI linked the alias to a mail-order purchase for the Mannlicher Carcano C2766. Yet this correlation appears a full day after the alleged finding of the card. The timing inconsistency not only impacts the chain of custody but also coincides with the sudden connection of the alias to the mail order purchase. This raises substantial questions about the evidence handling process, the chronology of the case, and the overall integrity of the chain of custody. (Meagher, pp. 181-200)

20. Could Marina have testified against Lee?

The question of whether Marina Oswald could have legally testified against her husband, Lee Oswald, raises interesting forensic considerations for the case. Under Texas law, spouses are generally permitted to serve as witnesses for each other in criminal cases. However, a crucial exception exists they cannot testify against each other unless one spouse is being prosecuted for an offence committed against the other. In the context of Oswald’s hypothetical trial, Marina’s testimony would have been excluded based on this spousal privilege. This means that the controversial backyard photographs, which were allegedly linked to Lee, could not have been admitted into evidence to be used against him. This is because Marina’s testimony, which was the sole source of corroboration for the photographs, would have been inadmissible due to the spousal privilege. (see this)

“The experts who test fired the rifle deemed that this rifle in evidence was so unreliable that they did not practice with it for fear that pulling the trigger would break the firing pin”. (Reclaiming Parkland; p. 27)

“The experts who test fired the rifle deemed that this rifle in evidence was so unreliable that they did not practice with it for fear that pulling the trigger would break the firing pin”. (Reclaiming Parkland; p. 27)

Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry. “A great deal has been written about the relationship of the Dallas Police Department with Jack Ruby. We have twelve hundred men in our department, and we had each man submit a report regarding his knowledge or acquaintance with Jack Ruby. Less than fifty men even knew Jack Ruby. And less than a dozen had ever been in his place of business. Most of these that had been in his place of business had been in there because they were sent there on investigations or had answered a call for police service. I believe there was four men in our department that we were able to determine had been there socially. That is off duty. That were present in his nightclub.”

Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry. “A great deal has been written about the relationship of the Dallas Police Department with Jack Ruby. We have twelve hundred men in our department, and we had each man submit a report regarding his knowledge or acquaintance with Jack Ruby. Less than fifty men even knew Jack Ruby. And less than a dozen had ever been in his place of business. Most of these that had been in his place of business had been in there because they were sent there on investigations or had answered a call for police service. I believe there was four men in our department that we were able to determine had been there socially. That is off duty. That were present in his nightclub.”

“Everything pertaining to what’s happening has never come to the surface. The world will never know the true facts of what occurred—my motives. The people have had so much to gain and had such an ulterior motive for putting me in the position I’m in. Will never let the true facts, come above board to the world.” Jack Ruby.

“Everything pertaining to what’s happening has never come to the surface. The world will never know the true facts of what occurred—my motives. The people have had so much to gain and had such an ulterior motive for putting me in the position I’m in. Will never let the true facts, come above board to the world.” Jack Ruby.

What is the chain of custody of the Selective Service Card?

What is the chain of custody of the Selective Service Card?

Challenging the Existence of the Hidell Card on November 22, 1963.

Challenging the Existence of the Hidell Card on November 22, 1963.