Part of the official JFK assassination lore is that, on the night of April 10, 1963, accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald took a bus close to the Dallas Turtle Creek neighborhood of General Edwin A. Walker, then a nationally prominent right-wing political activist and armed himself with his Mannlicher-Carano rifle. Oswald then walked to behind the Walker residence, on a service road, a type of back-alley. Walker was seated motionless behind a desk inside his home and facing a large first-floor window. Resting his rifle on a latticed fence about 30 yards away, Oswald took a potshot at his target at 9 pm.

And missed. Entirely. The shot went over and wide of Walker’s head and into a wall. Walker, on surveying the latticed fence afterwards that evening with a lieutenant from the Dallas Police Department (DPD), remarked that the unknown would-be assassin was a “lousy shot.”

A police officer reviewing the layout and shooting that night replied, “He couldn’t have missed you.”

Official Version

The above official version then posits that Oswald, after shooting and missing Walker, then “buried” his rifle somewhere and rode a bus back home, where he nervously related to his wife Marina details of his expedition.

Importantly, also entered into the lore was that Oswald would have struck Walker, save for a windowpane that deflected his shot.

This legend reached something of a zenith in the federally-funded Smithsonian magazine article on 2013. That article not only casually assumed Oswald’s guilt in the assassination of President Kennedy, but then described the shot that missed Walker thusly:

Drawing a tight bead on Walker’s head, he (Oswald) pulls the trigger. An explosion hurtles through the night, a thunder that echoes to the alley, to the creek, to the church and the surrounding houses. Walker flinches instinctively at the loud blast and the sound of a wicked crack over his scalp—right inside his hair.[1]

Thus, in the recounted mythology, the shot that missed Walker actually passed through the hair on the general’s head.

The Dallas Morning News chimed-in in 2013 with a similar story—it was the 50th anniversary year of the JFK murder—that also blithely assumes Oswald’s guilt in both the Kennedy and Walker shootings and adds, “The bullet (fired at Walker) first hit the screen and then the wood frame between the upper and lower windowpanes. Its original path deflected, it passed just above Walker’s scalp.”[2]

In other words, only a windowpane deflected the Oswald bullet and saved Walker’s life.

In most regards, the popular-media version of the Walker shooting is actually the opposite of what really happened that night and is, perhaps unsurprisingly, another mythology regarding the JFK murder.

The Real Story

There are many reasons not to convict Oswald of either the Kennedy or Walker shootings in 1963. But first, let’s dispose of the dramatic media treatment of that night at General Walker’s and his close brush with death.

First, Walker, a military veteran who had commanded special forces in combat in World War II, far from feeling a bullet through his scalp, actually initially told investigating officers from the Dallas Police Department that he thought neighborhood kids had tossed a firecracker into to his den through an open window.

If that! For in a supplementary report filed on April 10, it was written that Walker “stated that when he heard the noise, he thought it was some sort of fireworks.” [3] Fireworks? Hearing fireworks is a far cry from the sensation of a bullet passing through one’s scalp. In truth, only after discovering and examining a bullet hole in the wall behind him, did Walker conclude he actually had been shot at—and so he related to the DPD.

Secondly, a review of Dallas Police Department documents from the night of April 10 reveals whoever shot at Walker that night would have missed even more widely, save for the deflection downwards of the windowpane.

Here is a photo of the Walker windowpane and the damage caused by the passing bullet. Obviously, the damage is on the lower edge of the crossbar of the wind plane and likely would have deflected the bullet lower.

And that is how the Dallas Police Department (DPD) saw it.

“Officers observed a bullet of unknown caliber, steel jacket, had been shot through the window, piercing the frame of the window and going into the wall above comp’s (Walker’s) head,” according to DPD report filed on April 10 (italics added).

The report continues, “The bullet struck the window frame near center locking device. From the point where the bullet hit the window frame to the point where it struck the wall is a downward trajectory.”

It is hard to escape the conclusion that whoever shot at Walker would have missed by even more, except for the deflection. The shooter missed Walker from a distance of about 30 yards, likely armed with a rifle resting on a fence for support.

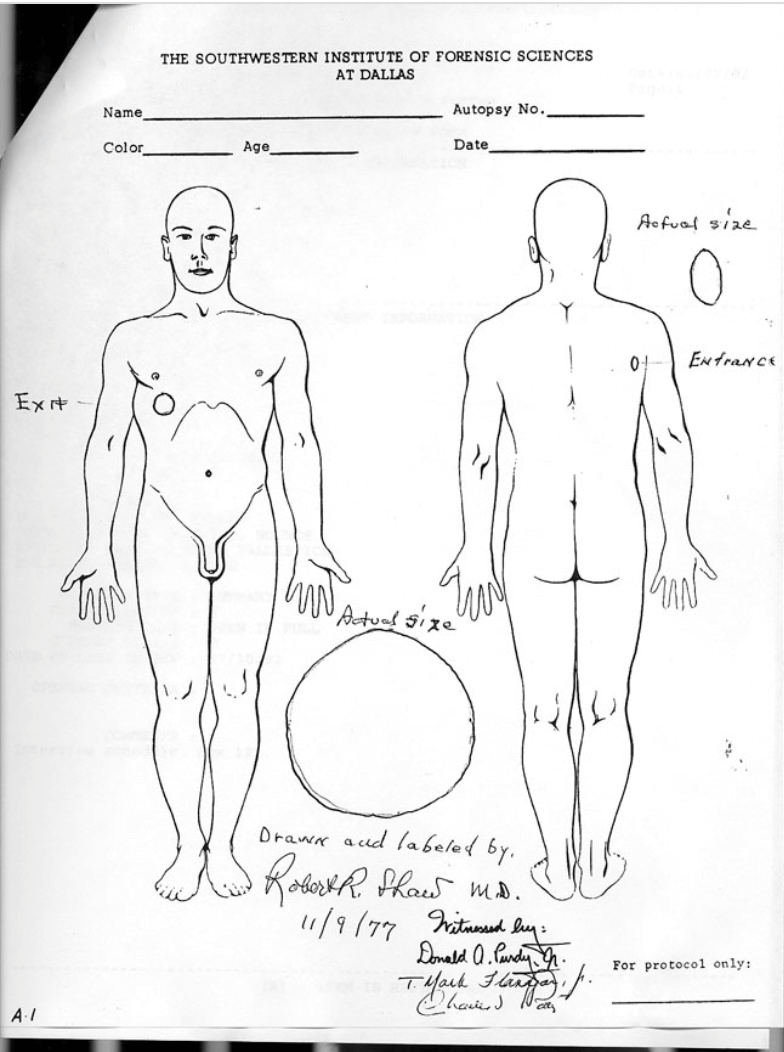

In addition, careful readers will also note that that the DPD found a “steel jacket” slug at the scene of the Walker shooting. Assassination researchers know, of course, that Oswald’s Mannlicher-Carcano used copper-jacketed ammo, from the Western Cartridge Company.

One thing about police officers is that they tend to know guns and ammo and one might assume that the DPD assigned some of its better detectives to the Walker shooting, given his national prominence in 1963.

But after the Kennedy murder, the DPD sent the steel-jacketed bullet—stated in police reports to be a 30.06 calibre—to the FBI. The federal agents said the mangled Walker slug was actually a 6.5 projectile from the Western Cartridge Company and copper-jacketed. In other words, a Mannlicher-Carcano bullet.

In a more-innocent era, one might assume the DPD made a mistake—after all, mistakes happen. And the Walker bullet, in fact, was badly distorted after striking the windowpane and passing through a wall in the Walker residence.

But since the 1960s, the profoundly dismaying history of CE 399, the “Magic Bullet,” has been revealed: the famed nearly pristine dome-headed slug was almost certainly introduced into the evidentiary record within the FBI facilities in Washington. The curious “pointy head” slug found on the Parkland hospital hallway floor Nov. 22 has disappeared and almost certainly had nothing to do with the JFK murder anyway.[4]

So, with the true story of the Magic Bullet revealed, one reasonable concern is that the FBI also fabricated evidence in the Walker shooting, replacing a steel-jacketed projectile from Dallas with a copper-jacketed Winchester Cartridge 6.5 slug.

Unfortunately, the records do not reveal why the DPD detective had concluded the Walker slug was steel-jacketed. If the detective had placed the slug on his desk next to a magnet, perhaps he would have noticed the Walker bullet wiggle. (Worth noting, steel-jacketed bullets can be copper coated, the softer metal copper applied to decrease wear-and-tear on gun barrels). In any event, the Walker projectile was originally logged as a steel-jacketed 30.06 slug.

There is much more to that evening in April 1963; for example, outside Walker’s home at least two vehicles sped from the scene in the wake of the gunfire, as seen by multiple witnesses.

Two Cars Leave the Scene

Though hardly dispositive, an additional curiosity is that two automobiles were seen swiftly leaving the scene of the Walker shooting on April 10, in the immediate aftermath of gunfire.

Hearing the Walker gunshot, a youth named Kirk Coleman immediately thereafter peered over a fence and “saw a man getting into a 1949 or 1950 Ford, light green or light blue and take off,” according to DPD report filed on April 11.

“This was in the parking lot of the Church next to General Walker’s home. Also, on further down the parking lot was another car, unknown make or model and a man was in it. He had the dome light on and Kirk could see him bend over the front seat as if he was putting something in the back floorboard,” continued the report.

General Walker also told the Warren Commission he saw a car suddenly leave the area, in the immediate aftermath of the shooting.

Of course, Oswald is thought not to have had driving skills and certainly did not own a car. To be sure, the two cars could have left the Walker shooting scene suddenly as the sound of gunfire is disconcerting. But one might expect ordinary citizens hearing gunfire to report as much to police, yet the men in the vehicles have simply disappeared into that night, and evidently forever. No one has ever come forward and said they were innocent bystanders who drove away quickly on the night of the Walker shooting.

So, perhaps the departing vehicles held Oswald and compatriots.

The Dog That Did Not Bark

A Walker neighbor’s dog, known as an active barker, was conveniently ill and silenced that evening.

“The neighbor’s dog to the east of the Walker property is a fanatical barker, but on this incidence did not make a sound,” according to an April 12 DPD report.

Concerning the dog, a neighbor told the DPD that, “Dr. Ruth Jackson, who lives next door to the General, has a dog that barks at everybody and everything. The night that this offense occurred Dr. Jackson’s dog did not bark at suspects. Investigating officers received further information…that Dr. Jackson’s dog was very sick yesterday [the date of shooting] and is also sick today. Reason for this illness is unknown at this time.” (emphasis added)

Again, the report of conveniently sick dog is hardly dispositive. But if the dog was intentionally poisoned, it suggests an operation involving more than a lone nut who did not own a car.[5]

The Walker Backyard Photo and Other Evidence

And of course, one of the curiosities of the JFKA is the backyard black-and-white photo of Walker’s house, purportedly found in Oswald’s possessions after the JFK murder, featuring the infamous two-tone 1957 Chevrolet with its license plate mysteriously cut out.

If the photo was truly in Oswald’s possession, it is certainly suggestive.

In addition, Oswald’s wife, Marina, recounted discussions with her husband regarding the Walker shooting, although her testimony in the wake of the JFK assassination was regarded as unreliable, even by Warren Commission staff. In fact, Marina’s statements and testimony on nearly every topic, made under great duress, vacillated wildly on a daily basis.

Finally, there is also the “Walker letter,” an unsigned page written in pencil and in the Russian language. The undated letter gives instructions to Marina concerning paying bills, a post office box, disposition of Oswald’s personal belongings, and where Oswald could be located in the event of his arrest. The letter is said to have been written shortly before the Walker shooting, though its origins are disputed.

None of the above evidence is enough to convict Oswald, even if it is “real” and not fabricated. But assuming the evidence in Oswald’s possession is not planted, there is a strong suggestion that Oswald participated in the Walker shooting.

An Explanation of the Walker Shooting

The Warren Commission presented the Walker shooting as another version of Oswald as the leftie-loser-loner nut acting out a demented fantasy. Even the House Select Committee on Assassinations did little with the topic.[6]

But for the purpose of this article, the Warren Commission treatment of Walker shooting is the interesting part.

In truth, whoever shot at Walker either—

- Was a lousy shot, to put it mildly

- Intended to miss

- Had faulty firearms

- Possibly had compatriots

None of above surfaces in the Warren Commission treatment of the Walker shooting.

Indeed, the version that the “windowpane deflection likely saved Walker” is allowed to survive unchallenged in the Warren Commission version of events and grew in mass media literature over the years, as seen in the above quotes from the Smithsonian and Dallas Morning News.

A Better Explanation

My own interpretation is that Oswald was possibly the gunman who fired in the direction of Walker in April 1963, but that he had accomplices (hence the cars racing from the scene), he did not use a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle (hence the steel-jacketed bullet), and missed intentionally.

But why such an exercise?

Based on the research of scholar John Newman and HSCA investigator Dan Hardway, Oswald was an asset of sorts for US intelligence agencies, not exactly rare in the early 1960s, when the CIA literally had thousands of such individuals in the US or nearby as part of expansive anti-Fidel Castro efforts.

Oswald, contend Hardway and Newman, was being primed for something, possibly for the JFK assassination or another event that could be blamed on Castro or pro-Castro types.

It is my speculation that the Walker escapade was part of an Oswald biography-building exercise and to practice and test Oswald’s nerve for an intentionally unsuccessful assassination attempt of a prominent figure—such as President Kennedy—an attempt that could then be blamed on Castro.

If Oswald could be made the patsy in such an event, such as the JFKA, the fallout could justify a major operation against the Cuban leader.

If the Walker shooting was a test of Oswald, then evidently he passed.

[1] Shultz, Colin “Before JFK, Lee Harvey Oswald Tried to Kill an Army Major General,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 4, 2013.

[2] Peppard, Alan, “Before gunning for JFK, Oswald targeted ex-Gen. Edwin A. Walker — and missed,” The Dallas Morning News, November 19, 2018.

[3] “CE 2001 – Dallas Police Department file on the attempted killing of Gen. Edwin A. Walker,” Warren Commission, Volume XIV, (CD 81.1b).

[4] Aguilar, Gary and Thompson, Josiah, “The Magic Bullet: Even More Magical Than We Knew?,” History Matters.

[5] All police reports are found in Warren Commission Exhibit 2001.

[6] “The Attempt on the Life of Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker,” Warren Report, p. 284.